Page 1

Technical Note

Differential Oscilloscope

Measurements

A Primer on Differential Measurements,

Types of Amplifiers, Applications, and

Avoiding Common Errors

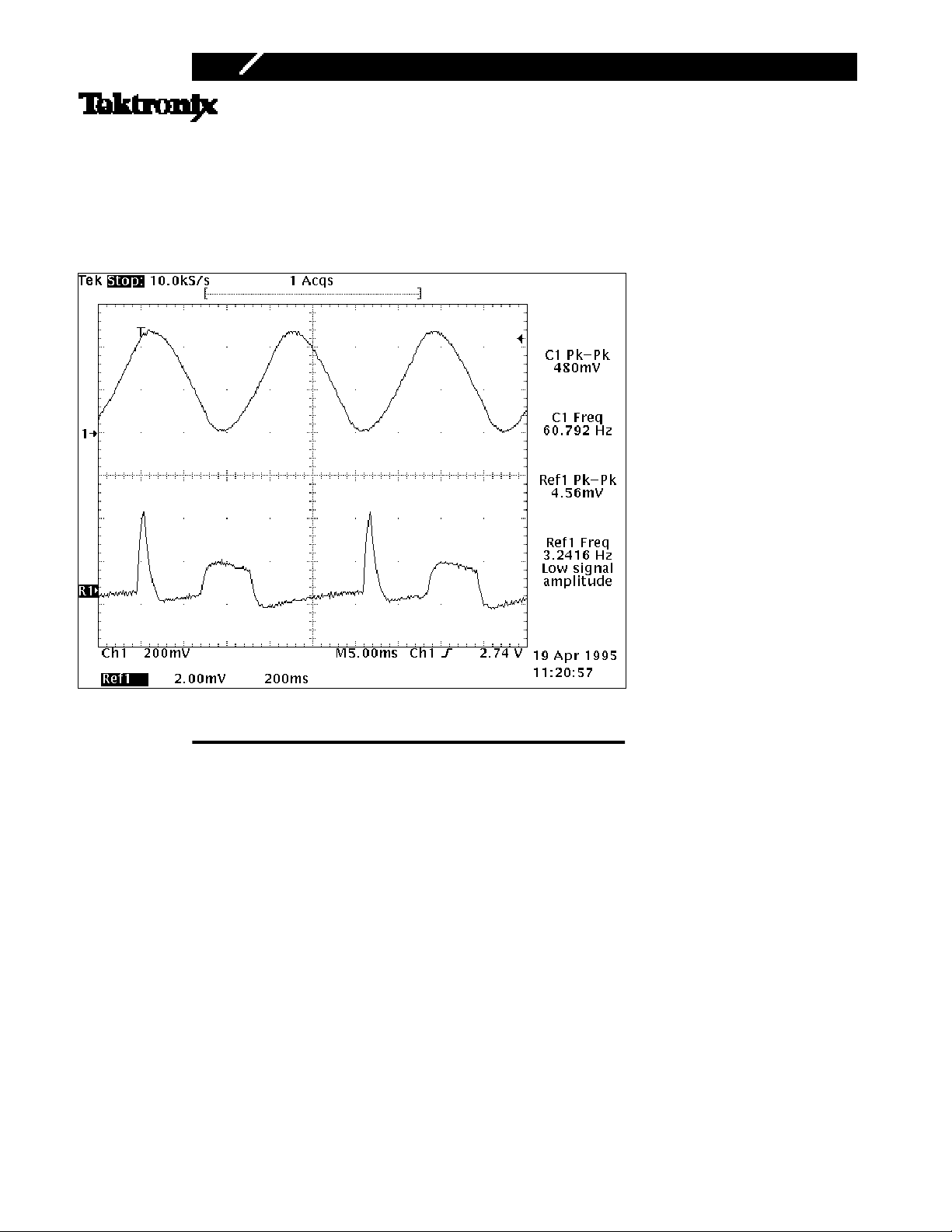

Simulated 4 mV

noise, using a conventional oscilloscope probe (upper). A differential amplifier extracts the signal from the noise

heartbeat waveform can not be measured in the presence of 500 mV

p-p

Introduction

All Measurements Are Two-Point

Voltage is always measured

between two points in a circuit. This is true whether

using a voltmeter or an oscilloscope. When an oscilloscope probe touches a point

in a circuit, a waveform usually appears on the display,

even if the ground lead is not

connected. In this situation,

the reference for the measurement is conducted

through the safety ground of

the scope chassis to the electrical ground in the circuit.

By virtue of their two probes,

digital voltmeters measure

potential between two

points. Because they are iso-

lated, these two points can

be anywhere in the circuit.

This has not always been the

case. Before the advent of the

digital voltmeter, hand-held

meters known as VOMs

(Volt-Ohm-Meters) were

used to measure “floating”

circuits. Because they were

passive, they tended to load

the circuit-under-test. Less

invasive measurements were

made with the highimpedance VTVM (Vacuum

Tube Volt Meter). The VTVM

had one major limitation –

the measurement was always

referenced to ground. The

VTVM housing was

grounded and connected to

the reference lead. With the

, 60 Hz common-mode

p-p

introduction of solid-state

gain circuits, high performance voltmeters could be

isolated from ground, allowing floating measurements to

be made.

Most oscilloscopes today,

like the venerable VTVM,

can only measure voltages

that are referenced to earth

ground, which is connected

to the scope chassis. These

are referred to as “singleended” measurements – the

probe ground provides the

reference path. Unfortunately, there are times when

this limitation lowers the

integrity of the measurement,

or makes measurement

impossible.

If the voltage to be measured

is between two circuit nodes,

neither of which is

grounded, conventional

oscilloscope probing cannot

be used. A common example

is measuring the gate drive in

a switching power supply

(see Figure 1).

Signals which are balanced

(between two leads without a

ground return) such as a

common telephone line cannot be measured directly. As

we shall see, even some

“ground referenced” signals

cannot be faithfully measured using single-ended

techniques.

When Ground Is Not Ground

We’ve all heard of “ground

loops” and been taught to

avoid them. But how do they

corrupt a scope measurement? A ground loop results

when two or more separate

ground paths are tied

Copyright © 1996 Tektronix, Inc. All rights reserved.

Page 2

Contents

Introduction · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 1

Differential Measurement Fundamentals · · · 4

Overview of Differential Measurements · · · · · · · 4

Common-Mode Rejection Ratio (CMRR) · · · · · · · 4

Other Specification Parameters · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 6

Differential-mode range · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 6

Common-mode range · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 6

Maximum common-mode slew rate · · · · · · · · · 6

Types of Differential Amplifiers and Probes · · · · 7

Built-in differential amplifiers · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 7

High-voltage differential probes. · · · · · · · · · · · 7

High-gain differential amplifiers · · · · · · · · · · · · 8

High-performance differential amplifiers · · · · · 8

Differential passive probes · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 8

High-bandwidth active differential probes · · · · 8

Voltage Isolators · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 8

Figure 1. Gate drive signal in a switching power supply is measured between TP1 and

TP2. Neither point is grounded.

Differential Measurement Applications · · · · · 9

Power Electronics · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 9

System Power Distribution · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 9

Balanced Signals · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 10

Transducers · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 10

Biophysical Measurements · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 11

Maintaining Measurement Integrity · · · · · · · 11

Sources of Measurement Error · · · · · · · · · · · · · 11

Input Connections · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 11

Grounding · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 11

Input Impedance effects on CMRR · · · · · · · · · · · 13

Common-Mode Range · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 13

Measuring Totally Floating Signals · · · · · · · · · · 14

Bandwidth · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 14

Glossary · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 15

Related Publications from Tektronix · · · · · · · 16

Figure 2. Ground loop formed by a scope probe. Metal chassis of both scope and device

under test are connected to safety ground and internal power supply common. Scope

probe ground connects to scope chassis at the input BNC connector.

together at two or more

points. The result is a loop of

conductor. In the presence of

a varying magnetic field, this

loop becomes the secondary

of a transformer which is

essentially a shorted turn.

The magnetic field which

excites the transformer can

be created by any conductor

in the vicinity which is carrying a non-DC current. AC

line voltage in primary

wiring or even the output

lead of a digital IC can produce this excitation. The current circulating in the loop

impedance within the loop.

Thus, at any given instant in

time, various points within a

ground loop will not be at

the same potential.

Connecting the ground lead

of an oscilloscope probe to

the ground in the circuitunder-test results in a ground

loop if the circuit is

“grounded” to earth ground

(see Figure 2). A voltage

potential is developed in the

probe ground path resulting

from the circulating current

acting on the impedance

within the path.

develops a voltage across any

page 2

Page 3

Thus, the “ground” potential

at the oscilloscope’s input

BNC connector is not the

same as the ground in the

circuit being measured (i.e.,

“ground is not ground”).

This potential difference can

range from microvolts to as

high as hundreds of millivolts. Because the oscilloscope references the measurement from the shell of

the input BNC connector, the

displayed waveform may not

represent the real signal at

the probe input. The error

becomes more pronounced

being measured decreases, as

is common in transducer and

biomedical measurements.

In these situations, it’s often

tempting to remove the probe

ground lead. This technique

is only effective when measuring very low-frequency

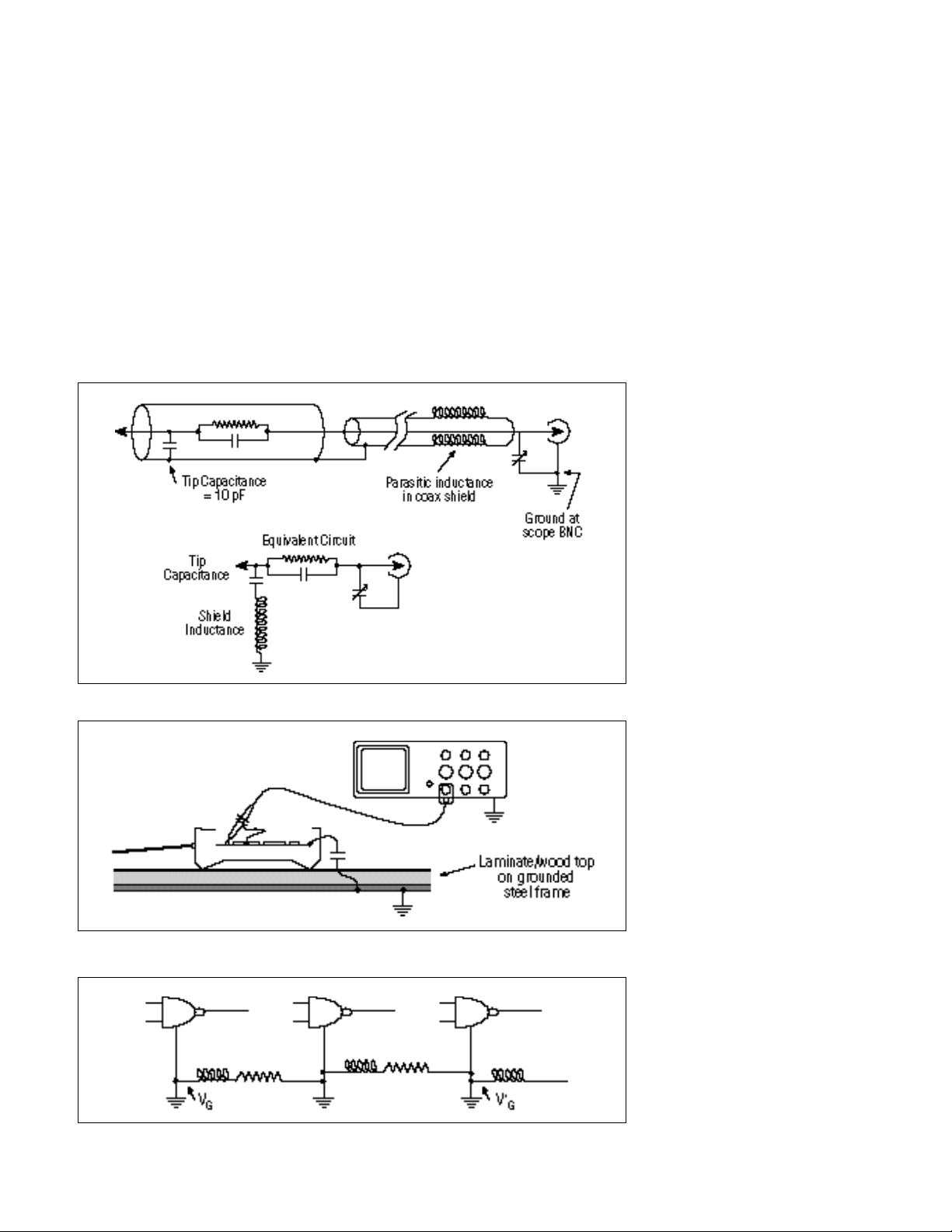

signals. At higher frequencies, the probe begins to add

“ring” to the signal caused by

the resonant circuit from the

tip capacitance and shield

inductance (see Figure 3).

(This is why you should

always use the shortest

ground lead possible.)

as the amplitude of the signal

Figure 3. Series resonant tank circuit formed by probe-tip capacitance and ground inductance.

Figure 4. “Floating” battery-powered cellular telephone probed with a grounded oscilloscope. Capacitance

between the phone circuitry and steel bench frame forms a virtual ground loop at high frequencies.

Figure 5. Minute parasitic inductance and resistance in ground distribution system result in VG≠ V'G.

We now have a dilemma:

create a ground loop and add

error to the measurement or

remove the probe ground

lead and add ring to the

waveform!

The next technique often

tried to break ground loops is

to “float” the scope or “float”

the circuit being measured.

“Floating” refers to breaking

the connection to earth

ground by opening the

safety-ground conductor –

either at the device-undertest or at the scope. Floating

either the scope or the

device-under-test (DUT)

allows the use of a short

ground lead to minimize ring

without creating a ground

loop.

This practice is inherently

dangerous, as it defeats the

protection from electrical

shock in the event of a short

in the primary wiring. (Some

special battery-operated

portable scopes incorporate

insulation which allows safe

floating operation.) Operator

safety can be restored by

placing a suitable groundfault circuit interrupter

(GFCI) in the power cord of

the oscilloscope (or deviceunder-test) with the severed

ground. However, be aware

that without a lowimpedance ground connection, radiated and conducted

emissions from the scope

may now exceed government

standards – as well as interfere with the measurement

itself. At higher frequencies,

severing the ground may not

break the ground loop as the

“floating” circuit is actually

coupled to earth ground

through stray capacitance

(see Figure 4).

Even when the measurement

system doesn’t introduce

ground loops, the “ground is

not ground” syndrome may

exist within the device being

measured (see Figure 5).

Large static currents and

high-frequency currents act

on the resistive and induc-

page 3

Page 4

tive components of the

device ground path to produce voltage gradients. In

this situation, the “ground”

potential referenced at one

point in the circuit will be

different than that referencing another point.

For example, ground at the

input of the high-gain amplifier in a system differs from

the “ground” potential at the

power supply by several

millivolts. To accurately

measure the input signal

seen by the amplifier, the

probe must reference the

ground at the amplifier input.

These effects have challenged designers of sensitive

analog systems for years. The

same effect is seen in fast

digital systems. The small

inductance within the

ground distribution system

can create a potential across

it, resulting in “ground

bounce”. Troubleshooting

systems affected by groundvoltage gradients is difficult

because of the inability to

really look at the signal

“seen” at the individual component. Connecting the oscilloscope probe ground lead to

the “ground” point of the

device results in the uncertainty of what effects the new

path adds to the ground gradient. A sure clue that a

change is occurring is seen

when the problem in the circuit either gets better (or

worse) when the probe

ground is connected. What

we really need is a method to

make a scope measurement

of the actual signal at the

input of the suspect device.

By using an appropriate differential amplifier, probe, or

isolator, accurate two-point

oscilloscope measurements

can be made without introducing ground loops or otherwise corrupting the measurement, upsetting the

device-under-test, or exposing the user to shock hazard.

There are several types of

differential amplifiers and

isolation systems available

for oscilloscopes, each optimized for a particular class

of measurements. In order to

choose the proper solution,

an understanding of terminology is necessary.

Overview of Differential

Measurements

An ideal differential amplifier amplifies the “difference”

signal between its two inputs

and totally rejects any voltage

which is common to both

inputs (see Figure 6). The

transfer equation is:

VO= AV( V

where VOis referenced to

earth ground.

The voltage of interest, or

difference signal, is referred

to as the differential voltage

or differential mode signal

and is expressed as V

is the V

transfer equation above).

Figure 6. Differential amplifier.

page 4

+in

Differential Measurement Fundamentals

The voltage which is common to both inputs is

referred to as the CommonMode Voltage expressed as

. The characteristic of a

V

CM

differential amplifier to

is referred to

CM

+ i n

– V

– V

)

– i n

term in the

–in

DM(VDM

ignore the V

as Common-Mode Rejection

or CMR. The ideal differential amplifier rejects all of the

common-mode component,

regardless of its amplitude

and frequency.

In Figure 7, a differential

amplifier is used to measure

the gate drive of the upper

MOSFET in an inverter circuit. As the MOSFET switches

on and off, the source voltage

swings from the positive sup-

ply rail to the negative rail. A

transformer allows the gate

signal to be referenced to the

source. The differential amplifier allows the scope to measure the true V

signal (a few

G S

volt swing) at sufficient resolution such as 2 V / d i v i s i o n

while rejecting the several

hundred volt transition of the

source to ground.

Common-Mode Rejection Ratio

( C M R R )

Real implementations of differential amplifiers cannot

reject all of the common

mode signal. A small amount

of common mode appears as

an error signal in the output,

making it indistinguishable

from the desired differential

signal. The measure of a differential amplifier’s ability to

eliminate the undesirable

common-mode signal is

referred to as Common-Mode

Rejection Ratio or CMRR for

short. The true definition of

CMRR is “differential-mode

gain divided by commonmode gain referred to the

input”:

A

CMRR =

D M

A

C M

Page 5

Figure 7. Differential amplifier used to measure gate to source voltage of upper transistor in an inverter bridge.

Note that the source potential changes 350 volts during the measurement.

Figure 8. Common-mode error from a differential amplifier with 10,000:1 CMRR.

For evaluation purposes, we

can assess CMRR performance with no input signal.

The CMRR then becomes the

apparent V

put resulting from common

mode input. It’s expressed

either as a ratio – 10,000:1 –

or in dB:

dB = 20log

A CMRR of 10,000:1 would

be equivalent to 80 dB.

seen at the out-

DM

V

D M

(

)

V

C M

For example, suppose we

need to measure the voltage

in the output damping resistor of an audio power amplifier as shown in Figure 8. At

full load, the voltage across

the damper (V

reach 35 mV, with an output

swing (VCM) of 80 V p-p. The

differential amplifier we use

has a CMRR specification of

10,000:1 at 1 kHz. With the

amplifier driven to full

power with a 1 kHz sine

) should

DM

wave, one ten thousandth of

the common-mode signal

will erroneously appear as

at the output of the dif-

V

DM

ferential amplifier, which

would be 80 V/10,000 or

8 mV. The 8 mV represents

up to a 22% error in the true

35 mV signal!

The CMRR specification is

an absolute value, and does

not specify polarity (or

degrees of phase shift) of the

error. Therefore, the user can

not simply subtract the error

from the displayed waveform. CMRR generally is

highest (best) at DC and

degrades with increasing frequency of V

ential amplifiers plot the

CMRR specification as a

function of frequency.

Let’s look at the inverter circuit again. The transistors

switch 350 V and we expect

about a 14 V swing on the

gate. The inverter operates at

30 kHz. In trying to assess

the CMRR error, we quickly

run into a problem. The common-mode signal in the

inverter is a square wave,

and the CMRR specification

assumes a sinusoidal common-mode component.

Because the square wave

contains energy at frequencies considerably higher than

30 kHz, the CMRR will probably be worse than specified

at the 30 kHz point.

Whenever the common-mode

component is not sinusoidal,

an empirical test is the

quickest way to determine

the extent of the CMRR error

(see Figure 9). Temporarily

connect both input leads to

the MOSFET source. The

scope is now displaying only

the common-mode error. You

can now determine if the

magnitude of the error signal

is significant. Remember, the

phase difference between

and VDMis not specified.

V

CM

Therefore subtracting the displayed common-mode error

from the differential mea-

. Some differ-

CM

page 5

Page 6

Figure 9. Empirical test for adequate common-mode rejection. Both inputs are driven from the same point. Residual common mode appears at the output. This test will not catch the effect of different source impedances.

surement will not accurately

cancel the error term.

This is a handy test for determining the extent of common-mode rejection error in

the actual measurement environment. However there’s

one effect this test will not

catch. With both inputs connected to the same point,

there’s no difference in driving impedance as seen by the

amplifier. This situation produces the best CMRR performance. When the two inputs

of a differential amplifier are

driven from significantly different source impedances,

the CMRR will be degraded.

The specifics of the effect are

discussed later – see Input

Impedance Effects on

CMRR, page 13.

Other Specification Parameters

Differential-mode range is

equivalent to the input range

specification of an amplifier

or single-ended oscilloscope

input. Input voltages which

exceed this range will overdrive the amplifier, resulting

in output clipping or nonlinearity.

Common-mode range refers

to the voltage window over

which the amplifier can

reject the common-mode signal. The common-mode

range is usually larger than

or equal to the differential

range. Depending on the

amplifier topology, the common-mode range may or may

not change with different

amplifier gain settings.

Exceeding an amplifier’s

common-mode range may

have various results in the

output. In some situations,

the output will not clip and

may produce a close approximation of the true input,

with some additional offset.

In this situation, the display

may be close enough to what

is expected that it’s not questioned by the user. It’s

always a good practice to

verify that the commonmode signal is within the

acceptable common-mode

range before making any differential measurements.

Maximum common-mode

slew rate is specified for

some differential amplifiers

and most isolators. This

specification is often confusing but very important. Part

of the confusion results from

a lack of standard definition

between instrument manufacturers. Also, differential

amplifiers and isolators

behave differently when

their maximum commonmode slew rate is exceeded.

Essentially, maximum CM

slew rate is a supplemental

specification to CMRR. The

specification is usually given

in units of kV/µs.

Some types of differential

amplifiers, like other amplifiers, reach a large-signal

slew rate limitation before

the small-signal bandwidth

specification is exceeded.

When one or both sides of a

differential amplifier are

driven to slew-rate limiting,

the common-mode rejection

is degraded very rapidly.

Unlike CMRR, maximum

slew rate does not imply an

increasing amount of common-mode feed-through in

the output. Once the maximum common-mode slew

rate is exceeded, all bets are

off – the output is likely to

clamp at one of the power

supply rails.

In isolators, however, the

effect is more gradual – like

CMR in a differential amplifier. As the common-mode

slew rate increases (as

opposed to the frequency),

more of the common-mode

component “feeds through”

to the output. Intuitively, the

specification would imply a

maximum slew rate at which

a known amount of feedthrough appears in the output. It’s important to note

that with some isolators, the

CM slew rate specification is

actually a maximum nondestructive limit. The ability

to make meaningful measurements is lost at slew rates

much lower than the maximum specification. When

using an isolator, it’s best to

test the common-mode feedthrough before making critical measurements. This is

easily done by driving both

the probe tip and the reference lead with the same

common-mode signal and

observing the output.

page 6

Page 7

Types of Differential Amplifiers

and Probes

Built-in differential amplifiers. Many scopes have the

ability to make the simplest

differential measurements

built right in to them. This

mode is referred to as “channel A – channel B” or “quasidifferential”. While limited

in performance, this technique may be adequate for

some measurements. To

make a differential measurement, two vertical channels

are used – one for the positive input and one for the

negative input. The channel

used for negative input is set

to invert mode and the display mode is set to “ADD

Channel A + Channel B”. For

proper operation, both inputs

must be set to the same scale

factor, and both input probes

must be identical models.

The display now shows the

difference voltage between

the two inputs.

To maximize CMRR, the gain

in both channels should be

matched. This can be easily

done by connecting both

probes to a square wave

source with an amplitude

within the dynamic range of

the volts/division setting

(about ±6 divisions). Set one

of the channels to “uncalibrated – variable” gain and

Figure 10. Even when the scope is “floating”, parasitic capacitance forms an AC voltage divider which adds error to

the measurement. Note that reversing the probe leads will load the gate with >100 pF, possibly destroying the circuit-

adjust the variable-gain control until the displayed waveform becomes a flat trace.

The primary limitation of

this technique is the rather

small common-mode range,

which results from the

scopes vertical channel

dynamic range. Generally,

this is less than ten times the

volts/division setting from

ground. Whenever

> VDM, this mode of

V

CM

obtaining a differential result

can be thought of as extracting the small difference from

two large voltages.

Most digital storage oscilloscopes perform waveform

math in the digital domain,

after the analog signal has

been digitized. The limited

resolution of the analog-todigital converter is often not

adequate to view the resulting differential signal after

the common-mode signal is

subtracted out. Because the

AC gain in the two channels

is not precisely matched,

CMRR at higher frequencies

is rather poor.

This technique is suitable for

applications where the common-mode signal is the same

or lower amplitude than the

differential signal, and the

common-mode component is

DC or low frequency, such as

50 or 60 Hz power line. It

effectively eliminates ground

loops when measuring signals of moderate amplitude.

High-voltage differential

probes. Recently, high-volt-

age active differential probes

have appeared on the market.

A new topology using fixed

attenuation with switchable

differential gain allows these

probes to keep their full common-mode range in all gain

settings. The single attenuator greatly reduces complexity resulting in lower cost to

the user.

These probes provide an

affordable, safe method of

measuring line-connected circuits commonly found in

switching power supplies,

power inverters, motor drives,

electronic-lamp ballasts, etc.

With common-mode ranges

up to 1,000 V, these probes

eliminate the need for the

extremely dangerous practice

of “floating the scope”.

Recently, workplace hazard

monitoring organizations

such as the U.S. OSHA (Occupational and Safety and

Health Act) have intensified

their verification of equipment grounding, issuing

costly fines to violators.

In addition to the safety benefits, the use of these probes

can improve measurement

quality. An obvious benefit is

the full use of the scopes multiple channels with the simultaneous viewing of multiple

signals referenced to different

voltages. Because the probes

are true differential, both of

the inputs are high

impedance – high resistance

and low capacitance. Floating

scopes and isolators do not

have balanced inputs. The

reference side (the “ground”

clip on the probe) has a significant capacitance to ground.

Any source impedance the

reference is connected to will

be loaded during fast common-mode transitions, attenuating the signal.

Worse yet, the high capacitance can damage some cir-

page 7

Page 8

cuits (see Figure 10). Connecting the scope common to

the upper gate in an inverter

may slow the gate-drive signal, preventing the device

from turning off and destroying the input bridge. This

failure is usually accompanied with a miniature fireworks display right on your

bench – something many

power electronics designers

can attest to.

With the balanced low input

capacitance of high-voltage

differential probes, any point

in the circuit can be safely

probed with either lead.

High-gain differential amplifiers. A high-gain differential

amplifier, often an external

accessory, allows scopes to

measure very small amplitude signals – down to a few

microvolts. To avoid corruption from ground-loop and

ground-gradient effects, these

signals are always measured

differentially – even when

they are ground referenced.

When the source is not

ground referenced, the common-mode can be several

orders of magnitude greater

than the differential mode

signal of interest. To cope

with this, these amplifiers

have extremely high CMRR,

often 1,000,000:1 or greater.

Some high-gain differential

amplifiers include additional

functionality to improve the

integrity of low-amplitude

measurements. Selectable

low-pass filtering allows the

user to remove out-of-band

noise from lower-frequency

signals. Differential offset can

be used to remove galvanic

potentials introduced in the

input wiring or transducerbridge bias voltage. To allow

use with signal sources which

have high driving impedance,

some models allow the user

to set the input to virtually

infinite impedance.

As with any differential

amplifier, the slightest mismatch in channel gain

greatly reduces the ampli-

fier’s high CMRR. When the

application requires use of a

scope probe, only identical

non-attenuating (1X) models

should be used, as attenuating probes can not be

matched well enough to preserve the CMRR.

High-performance differential amplifiers. With the

advent of oscilloscopes with

plug-in amplifiers, high-performance differential amplifiers became available. These

amplifiers combined many

features to allow their use in

diverse applications. Calibrated slideback allowed the

amplifiers to be used in single-ended mode, with the

trace referenced thousands of

divisions away from ground.

This makes it possible to precisely measure ripple valley

in power supplies and power

amplifier headroom. Sophisticated high-speed clamp circuits enable the amplifier to

quickly recover from input

overloads hundreds of times

over-range. This provides the

ability to directly measure

settling time of amplifiers

and DAC circuits.

These amplifiers feature

bandwidth specifications of

100 MHz or more, with good

CMRR as well. However,

the CMRR is specified with

both inputs tied directly

together and driven from a

low-impedance source. In

an actual application, the

CMRR at higher frequencies

will be considerably

degraded by differences in

source impedance and

channel gain.

Differential passive probes.

To minimize this degradation, only specially matched

differential passive probes

should be used with these

amplifiers. Be sure to calibrate the individual probe to

the amplifier using the procedure provided by the probe

manufacturer.

High-bandwidth active differential probes. These

probes maintain high-fre-

quency CMRR by buffering

the signal right at the probe

tip, thereby eliminating the

degradation caused by passive probe cables. These

probes have high bandwidth

(100 MHz or more), high-sensitivity, and excellent highfrequency CMRR performance. They are commonly

used to perform measurements in disk-drive read

electronics, where the signals

are inherently differential.

Their use is becoming more

common in probing highspeed digital circuits as they

do not alter the ground gradient when searching for

ground-bounce problems.

Voltage isolators. While voltage isolators are not really

differential amplifiers, they

provide a means of safely

measuring floating voltages.

Compared with differential

amplifiers, isolators have

advantages as well as tradeoffs, and the selection of one

over the other depends on

the application. As the name

implies, isolators have no

direct electrical connection

between the floating inputs

and their ground-referenced

output. The signal is coupled

via optical or split-path optical/transformer means. Two

physical configurations are

available: integrated onepiece systems and split transmitter/receiver systems.

The models with separate

transmitters and receivers are

interconnected with fiberoptic cable. The transmitter,

which is powered by

rechargeable batteries, can be

remotely located from the

receiver. This is useful in situations where the signal

originates in environments

not hospitable to humans or

oscilloscopes. They can also

be used with very high common-mode voltages. The

floating voltage specification

is usually limited by the

insulation voltage of the

hand-held probe. If the probe

connections can be made

with the DUT powered off,

page 8

Page 9

Figure 11. Unequal input capacitance caused by the isolated shield. This forms an AC voltage divider, resulting in the Vref’ ≠ Vref at the probe clip.

the floating voltage is limited

only by the physical separation between the transmitter

and ground.

Because isolators have no

resistive path to ground, they

are a good choice for applications which are extremely

sensitive to leakage currents.

Circuits equipped with sensitive GFCI (Ground Fault Circuit Interrupters), such as

medical electronics, may

experience GFCI tripping

when connected to a differential amplifier. The lack of

ground terminated attenuators also gives isolators infi-

nite CMRR with static (DC)

common-mode voltages.

The disadvantage of isolators

is the fact that they are not

true differential amplifiers,

meaning that the input is not

balanced (see Figure 11). The

capacitance to earth ground

is considerably different in

the measurement (+) input

and the reference (–) input.

This results in the same problems as already described

when floating scopes. Source

impedance in the reference

lead forms an attenuator at

high frequencies with the

ground capacitance.

These problems can be minimized by connecting the reference to the point in the circuit with the lowest driving

impedance (invert the scope

channel to regain correct

polarity if necessary). If the

isolator has separate transmitter and receiver units,

physically isolate the transmitter from grounded surfaces as much as possible to

minimize capacitive coupling to ground. Placing the

transmitter on a cardboard

box or wooden crate can

make a marked improvement

in performance!

Differential Measurement Applications

Power Electronics

High-voltage differential

amplifiers provide an ideal

means of measuring circuits

which are line connected,

such as switching power

supply primaries, motor

drives, electronic-lamp ballasts, and similar systems.

They eliminate the need for

the dangerous practice of

“floating the scope”. The low

input capacitance will not

affect operation of inverters

by loading down gate-drive

circuits.

The characterization of

power switching devices

such as MOSFETs and IGBTs

often includes measuring

dynamic saturation characteristics. High-performance

differential amplifiers with

high-speed input clamps

allow accurate measurement

of turn-on saturation,

nanoseconds after being

overdriven (hundreds of

times full scale) when the

device was off. This allows

the use of the high sensitivities necessary to accurately

measure the saturation characteristics.

These amplifiers are also useful when measuring sec-

ondary circuits. By activating

the calibrated slideback (also

known as comparison voltage), the amplifier can be used

in a single-ended mode to

monitor ripple valley and linear-regulator headroom (see

Figure 12). With the slideback

set to the output voltage, the

headroom can be directly

V

C E

measured, at high sensitivity,

under a variety of dynamic

load conditions.

System Power Distribution

Developing high-precision

analog, mixed signal, and

high-speed digital systems

often involves troubleshoot-

page 9

Page 10

Figure 12. Using calibrated slideback to accurately measure power-supply ripple valley on the collector of the output regulator. Note that the scope is set to 100 mV/division with ground being 61 divisions off screen.

Figure 13. A transducer in balanced bridge configuration. A differential measurement is made between the taps of

the two divider legs.

ing power-distribution problems. These can be a

designer’s worst nightmare.

CAD systems offer little help

as the minute parasitics

which create these problems

are difficult or impossible to

model. A scope equipped

with a differential amplifier

is the best tool to track down

and pin-point the trouble

spots in the system.

Single-ended measurements

often hide power-distribution problems as they provide an alternate ground path

from which the signal is

measured. Not only does this

change the measurement, it

often affects the circuit operation as well – either improving or degrading it.

Placing the inputs of a differ-

power supply lead gives a

true picture of the device’s

power condition. Lead

inductance in logic devices

often isolates the IC from

local bypassing capacitance.

Even if the power supply

looks clean, both the ground

and power pins may be moving with respect to other

grounds in the system. By

moving the probe, it’s possible to track down dynamic

ground gradients between an

individual device ground

and other grounds in the system. The effects of ground

bounce in digital systems can

be easily measured. Probing

between an IC’s input and its

ground pin gives a picture of

the actual signal as seen by

that device.

ential probe right on an IC’s

Balanced Signals

Some systems employ signals which are inherently

differential in nature. When

both sides of the signal share

the same driving impedance

they are said to be balanced.

Balanced systems are common in professional audio

equipment, telephony, and

magnetic recording systems

(analog and digital memory)

to name a few. Differential

signal distribution is becoming more common in highspeed digital systems as well.

Ineffective attempts to measure these signals one side at

a time and “adding” the

results are error prone at

best. Often, loading only one

side of the signal with the

probe diverts energy to the

side not being measured.

Measuring a balanced system

differentially provides a true

picture of the signal.

Transducers

Differential measurements

are used universally in transducer systems. The small signal amplitudes and necessity

to eliminate ground loops

preclude the use of singleended measurements. The

word “transducer” brings to

mind connotations of devices

used for measuring mechanical phenomena such as

acceleration, vibration, pressure, etc. The application of

differential measurement

techniques goes beyond

these to include visual and

medical imagers, microphones, chemical sensors…

the list is endless.

Transducers which produce

a change in resistance are

often operated in a configuration known as a balanced

bridge (see Figure 13). This

configuration uses three

known resistances and the

transducer to produce a pair

of voltage dividers. The pair

is biased with a bridge supply and the voltage is measured differentially between

the divider taps. The advantage of this configuration is

page 10

Page 11

the elimination of the effects

of power supply fluctuations.

Often, a transducer produces

a DC output voltage representing the steady state

before excitation is placed in

the system. To get high resolution, it’s desirable to

remove the DC component.

AC coupling the amplifier

input is not effective if very

low-frequency components

(<2 Hz) need to be measured.

To accommodate this need,

many high-gain differential

amplifiers incorporate a differential offset feature. This

effectively inserts a floating,

adjustable power supply in

series with one of the inputs,

allowing the amplifier to

remain DC coupled. The offset control has considerable

range – as much as ±1 million divisions at the higher

gain settings.

Biophysical Measurements

CAUTION: Do not connect

any electrical instrument,

including a differential

amplifier, to a human subject unless it is specifically

designed for use on

humans. Suitable equipment will be certified to a

specific regulatory standard

as mandated by the individual country where it is used.

Measuring the electrical signals resulting from neurological activity presents several

challenges. The signals have

minute amplitudes – often

below a millivolt. The common-mode component can

be hundreds or even thousands of times greater than

the signal of interest. The

source impedance is rather

high. Usually, the differential

signal is corrupted with

high-amplitude noise. Fortunately, high-gain differential

amplifiers are equipped to

measure these signals.

CMRR specifications of

1,000,000:1 or more can

effectively eliminate the

common-mode component.

To deal with the high input

impedance, the amplifier can

be configured to infinite

input resistance mode. (Note

that if the specimen is not

shunted to ground by other

equipment, a separate probe

tied through a 100 kohm

resistor to ground should be

used to reduce the chance of

common-mode range overload.) Skin contact is usually

made with silver/silver chloride electrodes. These provide an ionic connection to

the specimen. They also generate a galvanic cell (battery)

with a half-cell voltage of

400 mV which adds a bias

voltage to the measurement.

The amplifier’s differential

offset can be used to remove

the bias while preserving

low-frequency response.

Because most biophysical

activity occurs at frequencies

below 20 Hz, bandwidth-limiting filters can be used to

reduce higher-frequency differential noise without altering the signal of interest.

Maintaining Measurement Integrity

Sources of Measurement Errors

Just like other measurements,

differential measurements

are subject to conditions

which generate errors. These

errors may or may not be

obvious in the results, and

Figure 14. Simplified schematic of a differential amplifier with attenuator.

may be misread as the

desired measurement. Some

of the more common sources

of error are covered below.

To understand what causes

these errors and how to

avoid them, we first need a

basic understanding of

what’s inside a differential

oscilloscope or probe.

The heart of the system is the

differential amplifier stage

(see Figure 14). The

schematic symbol is the

same as an op amp. Like the

operational amplifier, a differential amplifier rejects the

input common-mode signal

and only amplifies the voltage difference between the

two inputs. Unlike the op

amp, the differential amplifier has a known, finite gain.

In some configurations, the

gain is user-selectable. The

output is singled-ended and

referenced to ground. The

inputs are often FETs to give

very high impedance. The

input signal may pass

through a high-impedance

attenuator to reduce larger

signals to a range the ampli-

page 11

Page 12

fier can handle. The

demands on the attenuator

are much greater than those

in a single-ended amplifier.

Both sides must have identical DC and AC attenuation.

The amount of mismatch has

a first-order effect on the

CMRR. For example, to

maintain a 100,000:1 CMRR

specification, the attenuators

must match to better than

one part in 100,000

(0.001%); this leaves no margin for error in the differential amplifier! Of course, this

match needs to be maintained all the way from the

signal source.

Input Connections

Interconnecting the differential amplifier or probe to the

signal source is generally the

greatest source of error. To

maintain the input match,

both paths should be as identical as possible. Any cabling

should be of the same length

for both inputs. If probes are

used, they should be the

Figure 15. Time varying magnetic fields passing through the open leads induce a voltage as in a transformer

winding. This voltage appears as a differential component to the amplifier and is summed into the true VDMsig-

Figure 16. With the input leads twisted together, the loop area is very small, hence less field passes through it.

Any induced voltage tends to be in the VCMpath which is rejected by the differential amplifier.

same model and length.

When measuring low-frequency signals with large

common-mode voltages,

avoid the use of attenuating

probes. At high gains, they

simply cannot be used as it is

impossible to precisely balance their attenuation. When

attenuation is needed for

high-voltage or high-frequency applications, special

passive probes designed

specifically for differential

applications should be used.

These probes have provisions for precisely trimming

DC attenuation and AC compensation. To get the best

performance, a set of probes

should be dedicated to each

specific amplifier and calibrated with that amplifier

using the procedure included

with the probes.

It’s common practice to twist

the + and – input cables

together in a pair. This

reduces line frequency and

other noise pick up. Input

cabling that is spread apart

(see Figure 15) acts as a

transformer winding. Any

AC magnetic field passing

through the loop induces a

voltage which appears to the

amplifier input as differential and will be faithfully

summed into the output!

With the input leads twisted

together (Figure 16), any

induced voltage tends to be

in the V

path, which is

CM

rejected by the differential

amplifier.

High-frequency measurements

subject to excessive commonmode can be improved by

winding both input leads

through a ferrite torroid. This

attenuates high-frequency signals which are common to

both inputs. Because differential signals pass through the

core in both directions, they

are unaffected.

Grounding

The input connectors of most

differential amplifiers are

BNC connectors with the

shell grounded. When using

probes or coaxial input connections, there’s always a

question of what to do with

the grounds. Because the

measurement application

varies, there are no hard and

fast rules.

When measuring low-level

signals at low frequencies,

it’s generally best to connect

the grounds only at the

amplifier end and leave both

unconnected at the input

end. This provides a return

path for any currents

induced into the shield, but

doesn’t create a ground loop

which may upset the measurement or the deviceunder-test.

At higher frequencies, the

probe input capacitance,

along with the lead inductance, forms a series resonant

“tank” circuit which may

ring. In single-ended measurements, this effect can be

minimized by using the shortest possible ground lead. This

lowers the inductance, effec-

page 12

Page 13

tively moving the resonating

frequency higher, hopefully

beyond the bandwidth of the

amplifier. Differential measurements are made between

two probe tips, and the concept of ground does not enter

into the measurement. However, if the ring is generated

from a fast rise of the common-mode component, using

a short ground lead reduces

the inductance in the resonant circuit, thus reducing

the ring component. In some

situations, a ring resulting

from fast differential signals

may also be reduced by

attaching the ground lead.

This is the case if the common-mode source has very

low impedance to ground at

high frequencies, i.e. is

bypassed with capacitors. If

this is not the case, attaching

the ground lead may make the

situation worse! If this happens, try grounding the

probes together at the input

ends. This lowers the effective inductance through the

shield.

Of course, connecting the

probe ground to the circuit

may generate a ground loop.

This usually doesn’t cause a

problem when measuring

higher-frequency signals. The

best advice when measuring

high frequencies is to try

Figure 17. Effect of unequal source impedances. The + input attenuator is essentially driven from 0ohms, however the –input attenuator is driven from something less than 3 kohms. This adds to the 900kohms, increasing

its attenuation and lowering the CMRR.

making the measurement

with and without the ground

lead; then use the setup

which gives the best results.

When connecting the probe

ground lead to the circuit,

remember to connect it to

ground! It’s easy to forget

where the ground connection

is when using differential

amplifiers since they can

probe anywhere in the circuit

without the risk of damage.

Input Impedance Effects on

CMRR

Any source impedance acts

to form a voltage divider with

the input resistance (DC) and

capacitance (AC) of the input.

With single-ended measurements, the impedance effect

can usually be ignored as the

error seldom reaches 1%. But

with differential measurements, this small error contributes to the input-gain mismatch, which reduces common-mode rejection (see Figure 17).

The differential amplifier

CMRR specification is usually measured with both

inputs driven together via a

BNC tee connector. This

effectively gives zero

impedance difference looking

into the inputs. Ideally, the

real-life signal source would

also have identical driving

impedance. However, they

seldom do. As such, the real

CMRR performance will be

significantly less than the

amplifier specification.

If the amplifier’s input impedance, attenuation ratio, and

source impedances are all

known, it’s possible to determine the actual CMRR by calculating the actual divider

ratios in each input arm. However, it’s easier just to make a

subjective judgment of the

measurement performance.

Many high-gain amplifiers

have provisions for configuring them as instrumentation

amplifiers. An instrumentation amplifier has no input

attenuator. The input resistance is essentially infinite

12

(>10

ohms). This mode

greatly enhances low-frequency CMR when the

source impedance is rather

high, such as physiological

experiments. While instrumentation amplifiers have

infinite input resistance, they

still have input capacitance.

The CMR improvement with

high source impedances will

quickly degrade as the common-mode frequency

increases. Because instrumentation amplifiers don’t

have input attenuators, they

have limited common-mode

and differential-mode

dynamic ranges.

Common-Mode Range

Any amplifier can be overdriven, causing the output to

“clip”. The same effect

occurs in a differential

amplifier when the input differential-mode signal is large

enough to force the amplifier

beyond its output dynamic

range. Differential amplifiers

are also subject to another

overload condition – exceeding the input common-mode

range. This condition occurs

when the voltage that the

desired signal is riding on

) exceeds the amplifiers

(V

CM

input common-mode range.

Because the common-mode

signal is rejected by the

page 13

Page 14

Figure 18. VCMin a consumer audio electronic component. These devices usually have a two-wire power cord

with their chassis and circuitry floating.

amplifier, the dynamic range

is limited by the input stage

rather than the output swing.

Amplifiers with input attenuators have a greater common-mode range than differential-mode range. Because

the common-mode component is (hopefully) not seen

in the measurement, common-mode range overload

may not be obvious to the

user. This is especially true

when the common-mode

component is DC. Some

amplifier topologies will still

produce an approximate rendition of the differential signal with a significant gain

error when the V

CM

range is

exceeded. Because the waveform appears correct, many

users have been fooled by

this erroneous measurement.

Some amplifiers have overload indicators to warn the

user of a common-mode

overload condition. It’s a

good practice to verify that

the common mode is within

specified range before making critical measurements.

This is easily done by moving one of the input connections to ground and measuring the common-mode component with the amplifier

itself. The procedure is then

repeated with the other

input.

Measuring Totally Floating

Signals

Signal sources which are

totally floating, having no

connection whatsoever to

ground, pose a special problem when being measured

with a differential amplifier.

Common examples include

battery-operated electronic

equipment, consumer audio

components, and experimental physiological specimens.

Because there’s no shunting

impedance to ground, any

AC fields in the area will be

capacitively coupled into the

device being measured (see

Figure 18). Line-frequency

fields, radiated from fluorescent lighting and building

wiring, are common in this

measurement environment.

When coupled into the DUT,

the line-frequency field produces a common-mode voltage. With sufficient coupling

and high input impedance of

the amplifier, it’s possible to

inadvertently exceed the

common-mode range of the

amplifier. This is especially

true with amplifiers configured as instrumentation

amplifiers, since the load

impedance at line frequencies approaches infinity.

The overload situation can

be avoided by providing a

shunting impedance to

ground, reducing the capacitive coupling, or reducing

the field strength. Adding a

shunt path to ground is the

easiest approach. It need not

be a direct short, often a

10 kohm resistor is sufficient. If adding the shunt

impedance upsets the device

being measured or the measurement, try reducing the

capacitive coupling by

enclosing the DUT with a

metal screen which is tied to

ground. This effectively adds

a Faraday shield which provides a shunt path to ground

for AC fields. A final

approach is to try to minimize the field strengths. Substituting incandescent lighting for fluorescent, and maximizing the distance between

line-connected wiring and

the DUT are good starting

points.

Bandwidth

Differential amplifiers, like

single-ended scope amplifiers, often include a bandwidth limiting control. Highgain amplifiers may offer a

choice of low-pass frequencies. Bandwidth limiting

reduces high-frequency noise

components with minimal

degradation on lower frequencies. The bandwidth

limiting filters are located

after the input signal has

been transformed to single

ended. Therefore, their use

will not increase input common-mode range at higher

frequencies.

page 14

Page 15

ADC – Analog-to-Digital Converter. The “heart” of a digital storage oscilloscope

where the analog input signal is converted into the digital domain. Several characteristics of the ADC such as

sample rate, resolution, accuracy, and linearity directly

relate to the oscilloscope’s

performance.

Balanced – A signal transmitted through a pair of

wires, each having the same

source impedance. Ground

does not serve as a return

path for the signal.

Bandwidth Limit – A filter

which may be selected by the

user to attenuate noise outside of the bandwidth of

interest. Unless otherwise

specified, the filter is

assumed to be a low-pass

topology with a single-pole

(–6 dB/octave) roll off.

Clamp – A circuit which limits the output voltage swing of

an amplifier to keep it within

the linear operating range.

Usually this is done to reduce

the overload recovery time.

Clip –A distorted waveform

produced when an amplifier

does not have sufficient output voltage range to reproduce

the input signal. As the name

implies, the output appears as

if it was “clipped” off.

Common Mode – The component of an input signal

which is common (identical

in amplitude and phase) to

both inputs of a differential

amplifier. An ideal differential amplifier rejects all of the

common-mode signal.

Common-Mode Range – The

maximum voltage (from

ground) of common-mode

signal which a differential

amplifier can reject. Usually,

the common-mode range is

greater than the differentialmode range. Depending on

amplifier topology, the common-mode range may vary as

a function of gain.

Glossary

Common-Mode Rejection –

The elimination of the input

common-mode component

by a differential amplifier.

Common-Mode Rejection

Ratio – The performance

measure of a differential

amplifier’s ability to reject

common-mode signals.

CMRR is expressed as:

D i f f e r e n t i a l -

CMRR =

Because common-mode

rejection generally decreases

with increasing frequency,

CMRR is usually specified at

a particular frequency.

Differential Amplifier – A

three-terminal gain circuit

which processes the signal

component which is different

between two inputs while

ignoring the component which

is common to the two inputs.

Differential Mode – The signal which is different

between the two inputs of a

differential amplifier. The

differential-mode signal

) can be expressed as:

(V

DM

V

= (V

D M

Differential-Mode Range –

The maximum amplitude of

differential input signal that

a differential amplifier can

accept without overloading

the output. Exceeding the

differential-mode range

results in the amplifier either

clipping or clamping the signal. Generally the differential-mode range decreases as

the amplifier gain increases.

Differential Offset – A circuit

incorporated in high-gain differential amplifiers to null out

a DC bias present in the differential input signal. Electrically

equivalent to an adjustable

battery inserted in series with

one of the input leads.

Differential Probe – A probe

designed specifically for differential applications. Active

differential probes contain a

Mode Gain

Common-Mode Gain

+ I n p u t

) – (V

– I n p u t

)

differential amplifier at the

probe tips. Passive differential

probes are used with differential amplifiers and can be calibrated for precisely matching

the DC and AC attenuation in

both signal paths.

Floating – A signal which is

not referenced to ground. A

floating signal cannot be

directly measured with a single-ended instrument input.

Floating the Scope – The practice of defeating the protective

grounding system of an oscilloscope, allowing it to perform floating measurements.

Because the entire scope chassis is common to the probe

“ground” clip, this dangerous

practice may expose the user

to electrocution hazards.

Ground Loop – A circuit with

multiple low-impedance

paths connected to the same

ground potential. A ground

loop acts as a shorted transformer turn which induces

circulating ground currents.

These currents produce slight

changes in the ground potentials within the circuit.

Isolator, Isolated Probe – A

device which allows twopoint floating voltage measurements to be made with

single-ended ground referenced instrumentation. Isolation is accomplished by converting the input signal to

optical and/or magnetic (via

transformer) form.

Maximum Common-Mode

Slew Rate – The upper limit

of rate of change (dv/dt) of

the common-mode component on the inputs of a differential amplifier or isolator.

Signals with rise times that

exceed the maximum common-mode slew rate specification may produce extreme

distortion in the output signal. Sometimes this specification refers to a maximum

non-destructive limit of the

instrument.

page 15

Page 16

Quasi Differential – A

method of creating a differential amplifier by adding

two conventional oscilloscope input channels with

one set to invert mode. To

produce meaningful results,

both channels must be set to

the same volts/division position. Compared with true differential amplifiers, quasidifferential mode has very

limited common-mode range

and lower CMRR, particularly at high frequencies.

Slideback (Comparison Voltage) – A configuration pro-

vided by some differential

amplifiers which connects a

precision calibrated voltage

source to one of the amplifier

inputs. This provides a single-ended amplifier with an

extremely large range of calibrated offset. Unlike differential offset, slideback mode

can only perform singleended (ground referenced)

measurements.

Single-Ended – A measurement of a voltage potential

referenced to ground. A conventional oscilloscope input

can only make single-ended

measurements.

Related Tektronix Publications:

Biophysical Measurements,

3GW-10379-0

Floating Measurement Solutions Selection Guide,

5 1 W-1 0 4 5 7 - 0

Interpreting Mechanical

M e a s u r e m e n t s, 3GW-10381-0

Written by Steve Sekel,

Tektronix, Inc.

For further information, contact Tektronix:

World Wide Web: http://www.tek.com;

Canada 1 (800) 661-5625; Denmark 45 (44) 850700; Finland 358 (0) 4783 400; France & North Africa 33 (1) 69 86 81 81; Germany, Eastern Europe, & Middle East 49 (221) 94 77-0; Hong Kong (852) 2585-6688;India

91 (80) 2265470; Italy 39 (2) 250861; Japan (Sony/Tektronix Corporation) 81 (3) 3448-4611; Mexico, Central America, & Caribbean 52 (5) 666-6333; The Netherlands 31235695555; Norway 47 (22)070700;

People’s Republic of China ( 86) 10-62351230; Republic of Korea 82 (2) 528-5299; Spain & Portugal 34 (1) 372 6000; Sweden 46 (8) 629 6500; Switzerland 41 (42) 219192; Taiwan 886 (2) 765-6362;

United Kingdom & Eire 44 (1628) 403300;USA 1(800)426-2200

From other areas, contact: Tektronix, Inc. Export Sales, P.O. Box 500, M/S 50-255, Beaverton, Oregon 97077-0001, USA (503)627-1916

Copyright © 1996, Tektronix, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. Tektronix products are covered by U.S. and foreign patents, issued and pending.

Information in this publication supersedes that in all previously published material. Specification and price change privileges reserved.

TEKTRONIX and TEK are registered trademarks.

7/96 FLG5059/XBS 51W-10540-1

ASEAN Countries (65) 356-3900;Australia & New Zealand 61 (2) 888-7066; Austria 43 (1) 70177-261; Belgium 32 (2) 725-96-10; Brazil and South America 55 (11) 3741 8360;

Loading...

Loading...