AN3276

Application note

ST solution for efficiency improvement in PFC applications,

back current circuit (BC

Introduction

The challenges for modern high efficiency switching power supplies are to minimize power

losses and increase their power density without raising the cost. The goal is to reduce both

power conduction and power switching losses.

Minimization of power conduction losses is difficult to achieve without considerably affecting

the cost and power density, since more material is required (bigger active and passive

components). Unlike the conduction losses, it is easier to reduce the power switching losses

without significantly increasing the power supply cost. There are two main ways to achieve

this improvement:

■ working on the dynamic behavior of the semiconductor technologies

■ working on circuit topologies

Novel diodes using technologies such as SiC and GaN materials significantly reduce the

switching losses. However, their high price makes them not so attractive for applications

such as desktop server power supplies, solar inverters and µinverters.

2

)

The patented circuit [see Section 5: References, 1.], described in this Application note is

based on the soft switching method and meets market expectations since its

efficiency/cost/power, and density/EMI trade-offs are better than high voltage SiC Schottky

diodes.

November 2010 Doc ID 17975 Rev 1 1/22

www.st.com

Contents AN3276

Contents

1 Existing solutions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

1.1 Diode switch-on losses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

1.2 Soft switch-on method . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

1.3 Active recovery circuit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

1.4 Passive recovery circuit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

2 The new ST solution - BC2: energy recovery circuit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

2.1 Concept description . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

2.2 Phase timing description . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

2.2.1 Phase before t0 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

2.2.2 Phase t0 to t1 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

2.2.3 Phase t1 to t2 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

2.2.4 Phase t2 to t3 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

2.2.5 Phase t3 to t4 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

2.2.6 Phase t

2.3 Electrical voltage stress in BC2 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

to t

4

5 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

2.4 Calculation of m2 and m1 ratios . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

2.5 Calculation of L . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

2.6 Range of products . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

3BC

2

design in 450 W PFC . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

3.1 BC2 design . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

2

3.2 BC

typical waveforms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

3.3 Efficiency comparison . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

3.4 Thermal measurement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

4 Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

5 References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

6 Revision history . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

2/22 Doc ID 17975 Rev 1

AN3276 Existing solutions

1 Existing solutions

This section describes some existing areas for efficiency improvements in PFC applications.

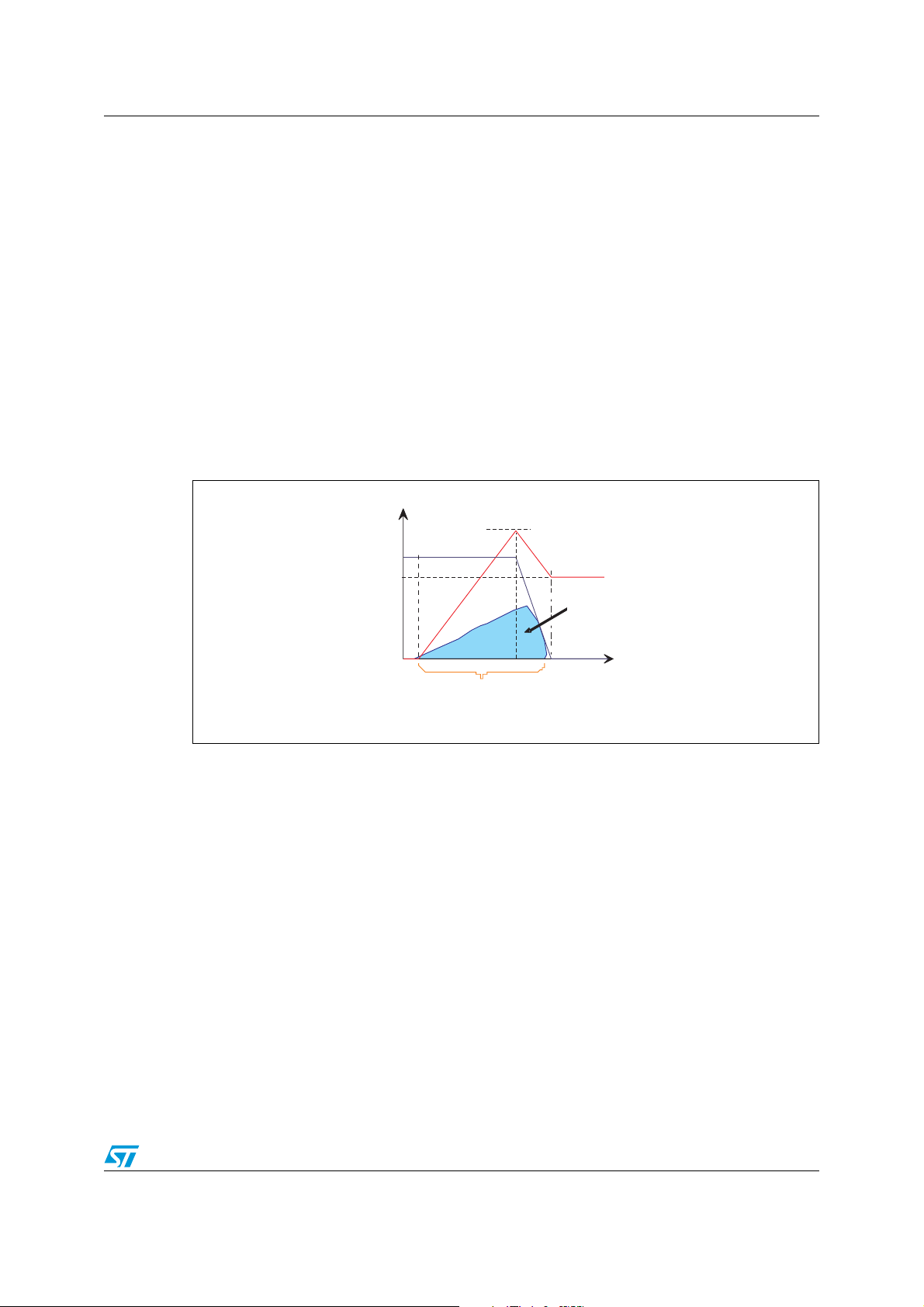

1.1 Diode switch-on losses

Usually, in mass market applications between 200 W and 2 kW, a power factor corrector

(PFC) working in continuous conduction mode (CCM) is mandatory. To improve the power

converter density, the switching frequency should be increased. Nevertheless, when the

switching frequency increases, power dissipation in the power switch/rectifier commutation

cells leads to the major switching losses in the PFC. The main power losses occur during

turn-on of the power switch due to both the voltage and current crossing area of the

MOSFET and the reverse recovery losses [see Section 5: References, 2.] produced by the

PN diode as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Switch-on losses in PN diode behavior

I+I

V

DS

RM 0

I

0

W

ON

t

Losses are due to area

between I +I and V

0RM DS

To reduce the losses of the PN rectifier, many semiconductor manufacturers have recently

introduced high-voltage Schottky diodes using SiC and GaN technologies. However, it is

impossible to completely remove the voltage and current crossing area during transistor

turn-on by improving component performance only.

Doc ID 17975 Rev 1 3/22

Existing solutions AN3276

Figure 2. Switch-on losses in SiC or GaN diode behavior

V

DS

I

0

t

Losses are due to area

between I and V

0DS

Unlike PN diodes, SiC diodes allow the turn-on dI/dt to be increased without increasing the

diode recovery current. Thus, switching time decreases and switch-on losses decrease too,

but they are not removed entirely. Today, in PFC designs, the turn-on dI/dt with the SiC diode

is around 1000 A/µs maximum to respect EMI standards, whereas the PN diode is used with

a dI/dt of 300 A/µs.

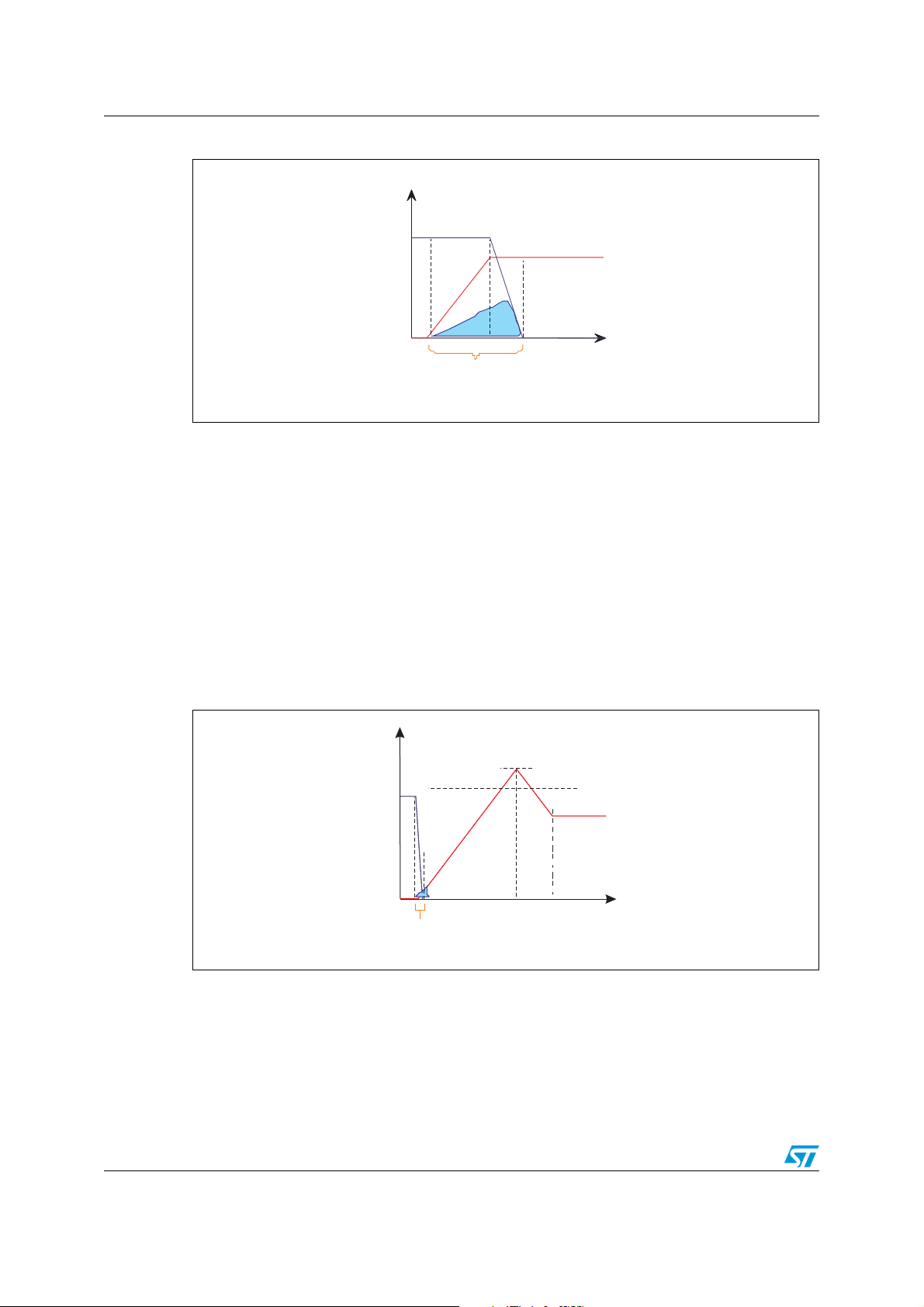

1.2 Soft switch-on method

Another way to reduce these losses is to use a soft switching method by adding a small

inductor L to control the dI/dt slope. This solution removes the current/voltage crossing area

and the PN diode recovery current effect during the turn-on of the transistor as shown in

Figure 3.

Figure 3. Switch-on losses in current soft switching behavior

Small losses:

Zero current switching

V

DS

dI/dt fixed by L

I+I

RM 0

I

0

t

4/22 Doc ID 17975 Rev 1

AN3276 Existing solutions

This soft switching solution is well known, but it requires that several technical criteria be

met:

● Reset the current in the inductor L at each switching period, whatever the variations of

the current, and input and output voltages.

● Recover the saved inductive energy without losses.

● Limit any overvoltage and overcurrent stress in the semiconductor devices.

● Keep cost down when adding any device.

● Maintain a similar power supply density.

There are many circuits that are classified in two families of recovery circuits:

● active

● passive

1.3 Active recovery circuit

In the active recovery circuit family, the zero voltage transition (ZVT) [see Section 5:

References, 3.] shown in Figure 4 is well known by designers. This circuit allows both

switch-on and switch-off power losses to be removed.

Figure 4. Zero voltage transition (ZVT) active recovery circuit

L

B

V

mains

L

T

R

D

1

T

ZVT

D

B

D

2

D

damping

R

damping

V

OUT

A theoretical study indicates that ZVT is an excellent topology for the PFC application, since

all the switch losses are removed. In addition, this circuit can work whatever the input and

output power variations. Nevertheless, in practice, the recovery current from the boost diode

D

significantly affects the ZVT behavior leading to some constraints on both inductance

B

and minimum duty cycle. During the reset current in the small inductor L, the recovery

current from D

involves a high-stress voltage and damping parasitic oscillation. Finally, the

2

dynamic behavior of the PN diode affects the global ZVT efficiency because conduction

times in the transistor should increase and a dissipative snubber is mandatory to reduce the

electrical stress across the semiconductors.

In terms of cost the ZVT circuit requires an additional power MOSFET and a specific PWM

controller. Several derivative circuits of the ZVT circuit have the same technical issue and

their higher price makes these circuits less than ideal for mass market applications.

Therefore, the passive recovery circuit can be more attractive.

Doc ID 17975 Rev 1 5/22

Existing solutions AN3276

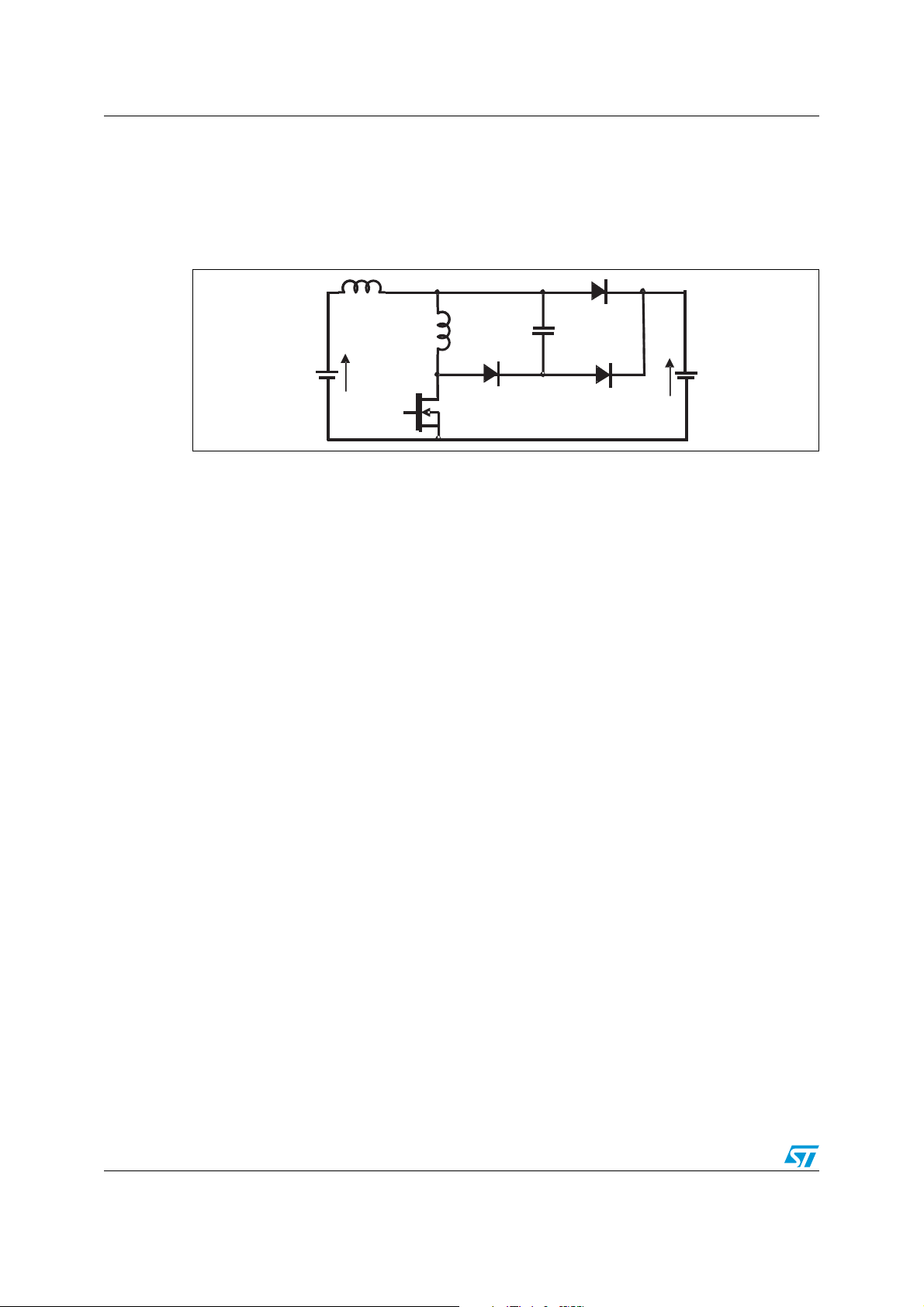

1.4 Passive recovery circuit

In the passive recovery circuit family the electrical schematic shown in Figure 5 is a good

example [see Section 5: References, 4.]; only two extra diodes and one resonant capacitor

are required.

Figure 5. Passive recovery circuit

L

B

L

V

mains

T

R

This circuit works well under unchanging external conditions. However, it is difficult to design

this kind of system in PFC applications since the current reset in the small inductor depends

on both boost diode recovery current and the external electrical conditions.

Although, the non-dissipative passive circuit requires fewer components, it is unfortunately

technically impractical in PFC applications. These examples highlight that the current

snubber method is well known but the technical challenge is to recover the L energy through

the application without affecting the five criteria listed in Section 1.2.

C

R

D

1

D

B

D

2

V

OUT

6/22 Doc ID 17975 Rev 1

AN3276 The new ST solution - BC2: energy recovery circuit

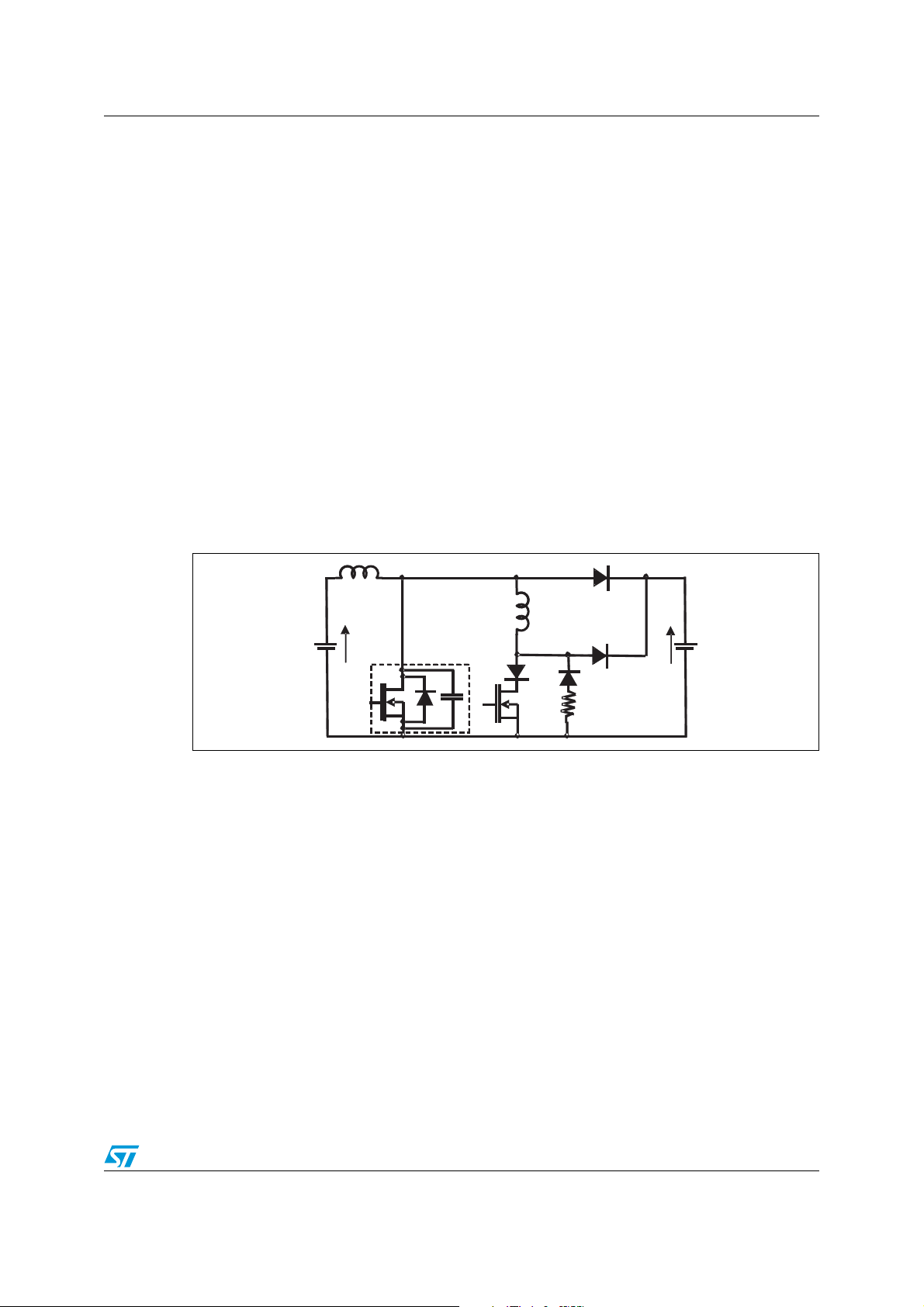

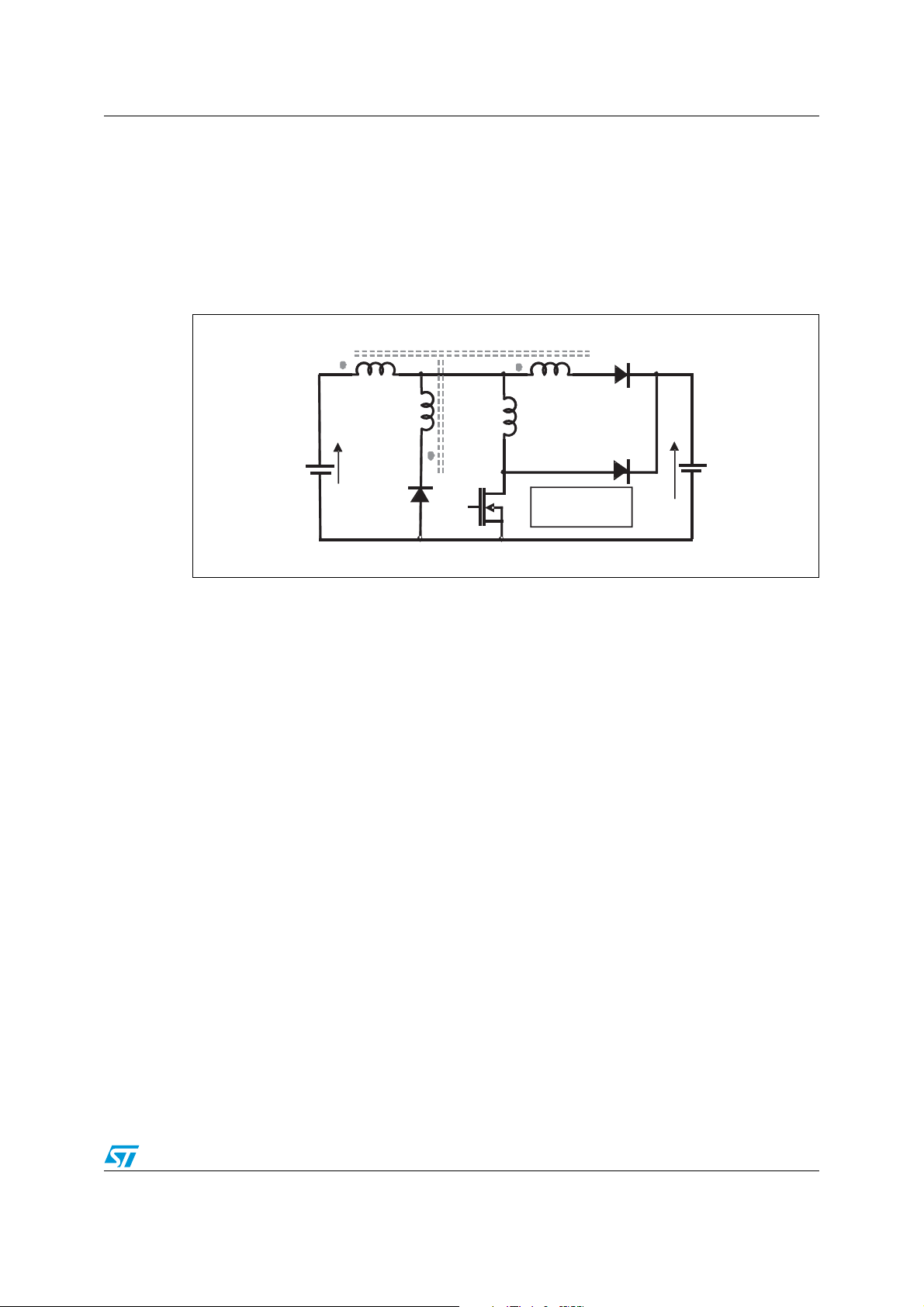

2 The new ST solution - BC2: energy recovery circuit

The innovative circuit has been designed [see Section 5: References, 1.] to respect the five

soft switching criteria in Section 1.2. Figure 6 shows that two additional diodes D

and two auxiliary windings N

and NS2 wound around the main boost inductor LB are

S1

designed to reset the energy stored in the small inductor L.

and D2

1

Figure 6. Novel energy recovery circuit: BC

L

N

B

p

V

mains

2.1 Concept description

The winding N

boost inductor when the transistor turns on. Since the mains input voltage modulates the L

voltage, it also modulates the reflected voltage across N

modulates the boost diode current I

combined modulations allow the extra current I

the winding N

injected into the output capacitor when the transistor turns off. The reflected voltage across

N

is also a function of the input voltage. This reflected voltage reaches its maximum when

S2

the AC line voltage is low, corresponding to the maximum value of the inductor L current.

These combined variations allow the current flowing in the inductor L to be cancelled in the

bulk capacitor through the diode D

additional windings N

(about 10 A/µs) as in a discontinuous mode switching converter. Their recovery currents do

not affect the behavior of the BC

allows the IRM current from the boost diode DB to be recovered in the main

S1

even in the worst case. The winding NS2 allows the extra current of L to be

S1

and NS2 are to switch off the diodes D1 and D2 with a low dI/dt

S1

2

N

N

S1

D

1

DB

even in the worst case. The benefits of these two

2

2

circuit.

L

T

R

m2=NS2/N

m1=NS1/N

and its associated recovery current IRM. These

flowing in the inductor L to be reset into

RM

D

S2

B

D

2

V

P

P

. This input voltage also

S1

OUT

B

Doc ID 17975 Rev 1 7/22

The new ST solution - BC2: energy recovery circuit AN3276

V

TR

V

L

V

DB

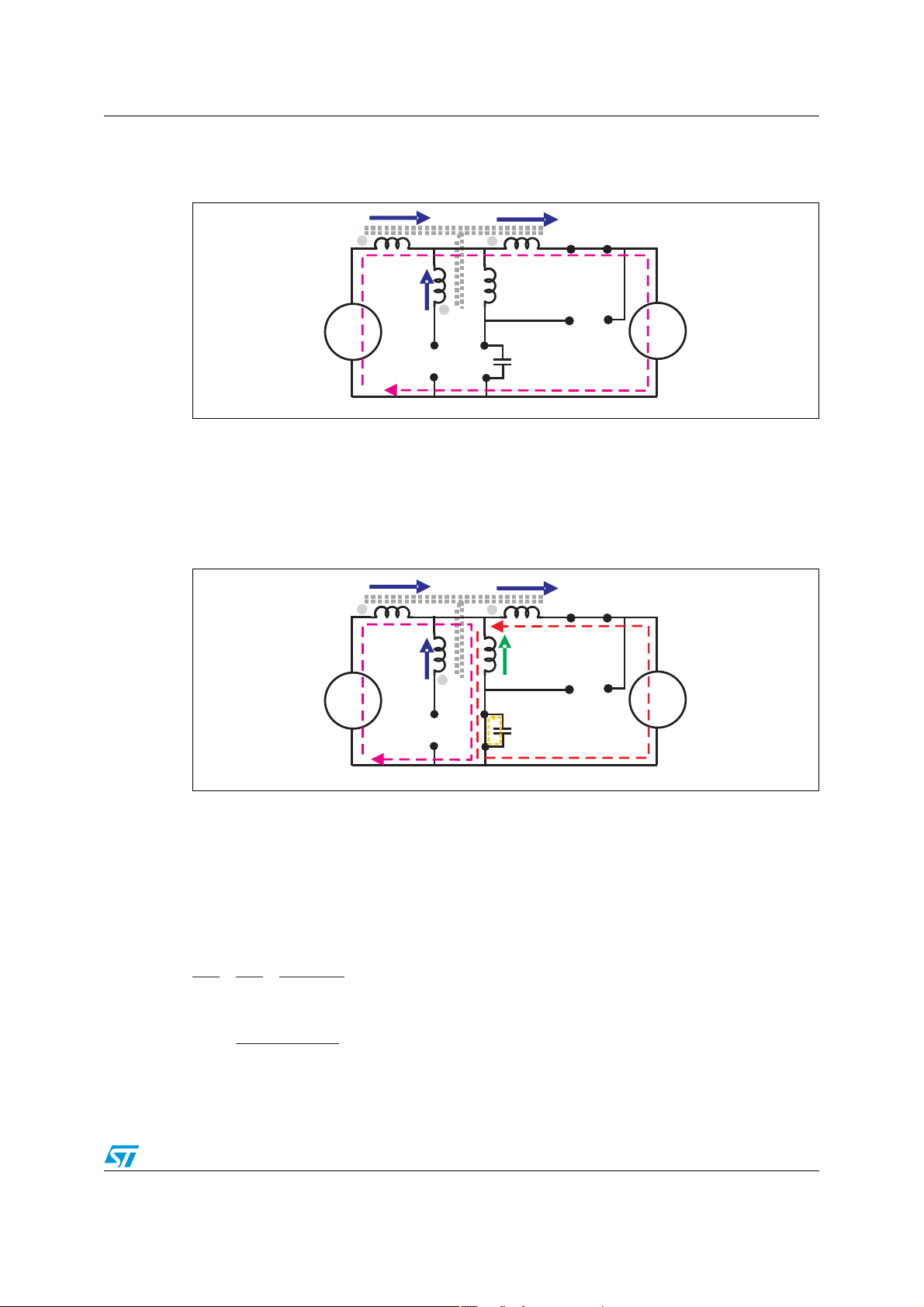

2.2 Phase timing description

Figure 7. Equivalent timing per phase

(IRM+I0)(1+m2)

V

TR

dI

-

=

I

TR

V

L

V

DB

⎛

⎜

I

D2

I

D1

I

DB

⎝

VV

I

0

dI

dt

dt

1

mVV

·+

)m1(

+

2

+

mm

·+-

mainsOUT

-

m1

1

I

·

RM

t

-=

2

2

V

21

D

·+

VmV

·+

2mainsOUT

mains

⎞

⎟

⎠

+

-

1

2

I

1

mainsOUTTR

L)m(

m

1

·)m1(

-

1

I

1

)m1(

2

)m1(

1

·+

VmV

mains2OUTDB

2

·+

L)m1(

V

0UT

-

1 + m

+

t

·

mVV

2

mainOUT

2

-

OUTmains

m1

2

t

)VV(

m

·

2

t

t

t

t

D

2

I

0

t

-I

I

I

mains

The winding ratios m

0

t

0

and m2 versus NP winding are those of the windings NS1 and NS2

1

RM

··2mmmmm

-

-

·

I

RM

t

t

1

2

-

1

1

I

1

I

0

2112

t

t

3

t

4

t

5

respectively.

8/22 Doc ID 17975 Rev 1

AN3276 The new ST solution - BC2: energy recovery circuit

2.2.1 Phase before t

Figure 8. Equivalent circuit before t

Before t0, the BC2 circuit has the same behavior as the conventional boost converter. The

boost diode D

capacitor.

2.2.2 Phase t0 to t

Figure 9. Equivalent circuit t0 to t

conducts to send the main inductor energy through the output bulk

B

1

0

V

mains

0

N

D

S2

I

0

+

-

+

-

N

S

1

D

1

1

I

0

N

S

1

I

0

D

1

L

C

oss

V

L

T

R

C

oss

N

I

S2

RM

D

D

D

V

V

OUT

+

-

OUT

+

-

B

2

B

2

V

mains

At t0, the power MOSFET turns on and the current in DB is equal to I0. At t0+, the current soft

switching occurs, that is to say, the voltage across the power MOSFET decreases to 0 volt

under a zero current and no switching losses appear. After t

increases linearly until it reaches the input current I

whereas the current flowing in D

decreases linearly down to -IRM.

B

added with the recovery diode IRM,

0

Figure 7 shows the behavior of these currents taking account of the m

The simplified dI/dt expression in transistor T

and the boost diode DB can be estimated

R

, the current flowing in L

0

transformer ratio.

2

using,

VV

dI

dI

dt

TRDB

dt

−

N

out

=≈

S2

L

and

V

N

At t

S

=

2

+, the C

0

−

m).VV(

mainsout

2

m1

+

2

capacitance of the power MOSFET is discharged in its R

OSS

DS(on)

. Unlike

standard PFC circuits, the voltage applied across the drain is lower because the reflected

Doc ID 17975 Rev 1 9/22

The new ST solution - BC2: energy recovery circuit AN3276

dI

V

voltage is subtracted from V

NS2

. This behavior provides the BC2 circuit with a benefit

OUT

since under the low output load, power saving occurs in the system and it can be evaluated

using:

2

P

C

OSS

1

t

−

0

2

Thus, the BC

⎡

2

⎢

V.C.

outOSS

⎢

⎣

2

reduces switch-off losses too.

+

⎛

−=

⎜

⎝

mainsout

m1

+

2

⎤

m.VV

⎞

2

⎥

F.

⎟

switching

⎥

⎠

⎦

2.2.3 Phase t1 to t

Figure 10. Equivalent circuit t1 to t2

At t

+, the boost diode DB turns off, and an overcurrent IRM is stored in the small inductor.

1

This overcurrent discharges the D

voltage polarity across the main inductor changes until it reaches D

this time, the overcurrent I

inductor.

Thus, the current flowing through N

L

at the same time as the Np winding biased by the mains voltage. The IRM current flowing

B

in D

decreases down to reach 0 A thanks to the reflected voltage V

1

V

=

1NS

m.V

−

mains

m1

−

1

1

2

V

+

-

mains

C

B

j

D

N

S2

I

0

V

L

N

S

1

I

RM

D

1

T

R

junction capacitance linearly. At the same time, the

B

is reduced by the transformer ratio m1 and is sent to the main

RM

contributes to charge the internal coil magnetization

S1

V

OUT

D

2

+

-

diode conduction. At

1

that it is given by:

NS1

and

)1m1.(L.I

−

RM

_t

≈

ON1D

To guarantee a soft switching behavior in discontinuous mode, the current in D

reach 0 A before time t

current is the largest when the V

addition, to cancel the D

the low reflected voltage V

_

−

D

1

≈

dt

Unfortunately, during this phase a high reverse voltage is applied across the boost diode D

10/22 Doc ID 17975 Rev 1

mains

mains

−

outreverse_DB

m.V

1

should

. The t

3

recovery current diode effect, the dI/dt_D1 is always low thanks to

1

m.V

1

NS1

time trend supports the PFC application since the IRM

D1_ON

voltage in the sinusoidal period is the highest. In

mains

and it is given by:

1

L).1m1(

:

N

S

2

1

S

−

m.(V

mains

VVVVV

+=++=

out

N

)2m

+

1

m1

1

B

AN3276 The new ST solution - BC2: energy recovery circuit

This feature requires a specific diode for this application, so ST has developed an optimized

diode with an accurate trade-off between the I

current value and its breakdown voltage.

RM

2.2.4 Phase t2 to t

Figure 11. Equivalent circuit t2 to t

At t2, the current in D1 reaches 0 A and then the BC2 works as a conventional power boost

converter. As the power transistor stays on, the current in the main L

inductor increases up to I

2.2.5 Phase t3 to t

3

V

4

+

-

mains

I

1

N

at time t3.

1

3

C

B

j

D

N

S2

V

L

S

1

D

1

T

R

D

V

OUT

2

+

-

and the small L

B

Figure 12. Equivalent circuit t3 to t

N

S

V

mains

+

-

4

N

D

S2

I

1

V

L

1

C

D

1

oss

D

V

B

2

OUT

+

-

At t3, the power transistor turns off. At this time the voltage across the MOSFET increases

linearly as its C

reach conduction in diode D

capacitance is charged by the current stored in the small inductor L to

OSS

. No overvoltage stress occurs on the power switch during the

2

turn off. At the same time, the voltage polarity across the main inductor changes until it

reaches D

shared as shown in Figure 7. The current in D

voltage from N

reach the nominal current at t

diode conduction. As soon as the diodes conduct together, the output current is

B

to reach 0 A with a low dI/dt. On the other hand, the current in DB rises to

S2

. This shared current is a benefit for the BC2 circuit. In the

4

starting at I1, decreases due to the reflected

2

PFC application working under a lower mains voltage such as 90 V rms, the highest

Doc ID 17975 Rev 1 11/22

The new ST solution - BC2: energy recovery circuit AN3276

application boost current is shared between DB and D1 diodes. Therefore the conduction

losses in the rectification stage are reduced. The reflected voltage V

and D2 time

NS2

conduction are given by:

V

=

N

2

S

−−

+

m).VV(

mainsout

2

m1

2

and

+−

ON_2D

−

1

=

t

)2m1.(L.I

m).VV(

mainsout

2

The t

V

mains

2

BC

circuit even under the worst case PFC applications such as high output load current

time trend supports the PFC application since the I1 current is largest when the

D2_ON

voltage range is lowest. Thus the discontinuous mode could be guaranteed in the

under the minimum V

diode effect, the dI/dt_D

_dI

D

≈

dt

2.2.6 Phase t4 to t

Figure 13. Equivalent circuit t4 to t

voltage range. In addition, to cancel the D2 recovery current

mains

is always low due to the low reflected voltage V

2

−−

+

m).VV(

mainsout2

2

L).2m1(

given by:

NS2

5

5

V

B

OUT

2

+

-

V

mains

N

D

S2

I

0

+

N

S

1

L

D

D

1

C

oss

At t4, the current in the D2 reaches 0 A and then the BC2 works like a conventional power

boost converter. Only the boost diode D

conducts. Due to the reflected voltage of NS2, the

B

voltage across the power switch is lower than V

in the bulk capacitor and power saving occurs as the transistor turns on at t

12/22 Doc ID 17975 Rev 1

. Thus the C

OUT

capacitor is discharged

OSS

.

0

AN3276 The new ST solution - BC2: energy recovery circuit

2.3 Electrical voltage stress in BC

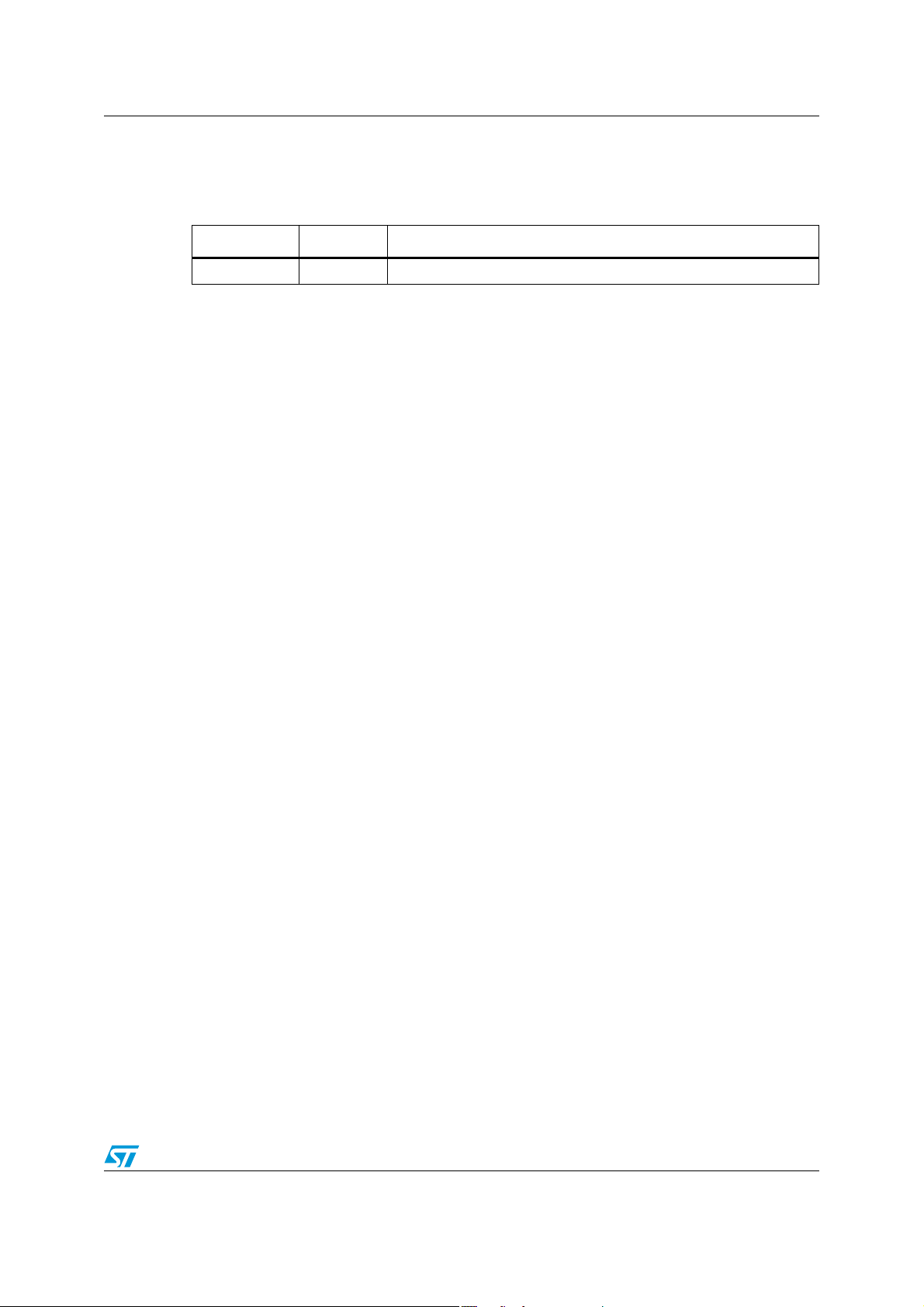

Ta bl e 1 summarizes the maximum voltage across each semiconductor versus the phases.

Table 1. Maximum reverse voltage in the BC

Maximum

voltages

VR

TRmax

VR

DBmax

VR

D1max

VR

D2max

The BC2 circuit needs to use a specific diode with a breakdown voltage higher than 600 V.

Moreover, its recovery current should be optimized to avoid an higher current in the power

transistor during the phase [t

STTH10BC065C and STTH8BC065) for the BC

sustain average currents of 5 to 8 A (depending on the application) and a repetitive reverse

voltage V

RRM

Phases Waveform expression > V

t3 - t

4

t1 - t

t0 - t

t3 - t

t0 - t

t1 - t

t2 - t

2

1

4

1

2

3

]. ST has developed specific diodes (STTH16BC065C,

1-t2

mainsRMS

mainsRMS

of 650 V.

2

2

V

OUT

)m(m2V

V

1

2

OUT

+⋅

21

V

+

OUT

)m(m)V2(V

+⋅−

21OUT

V

+

OUT

⋅

max

m1

+

⋅

max

m1

+

2

circuit. They have been designed to

OUT

NO

YES

NO

NO

?

2.4 Calculation of m2 and m1 ratios

To respect the discontinuous operating mode during the timing phases [t1-t2] and [t3-t4], the

time td1 and td2 shown in Figure 7 should be always positive. According to the typical CCM

PFC rules and both t

m

transformer ratio conditions.

2

m

>

2

2

mainsRMS

()

and

>

()

()

is the input PFC power, Fs is the switching frequency, V

IN

m

1

Where P

maximum rms voltage range and the I

turn-on dI/dt at its maximum operating junction condition.

D1_ON

OUT

and t

mainsRMS

⋅⋅⋅⋅+

mainsOUTmains

FVLmaxIm1

expressions, it becomes easy to define the m1 and

D2_ON

FLVmaxP

⋅⋅⋅

sOUTIN

()

⋅

sOUTRM2

2maxVV2maxV

⋅−⋅⋅

max is the maximum current recovery under the

RM

Doc ID 17975 Rev 1 13/22

LVmaxP2maxV-VmaxV

⋅⋅−⋅

OUTIN

mainsRMS

max is the

The new ST solution - BC2: energy recovery circuit AN3276

2.5 Calculation of L

There are several ways to rate the inductance L. For instance, its turn-on dI/dt can be rated

at 50 A/µs. Then, m

diode D

of V

. However, the reverse voltage across the D

B

to meet the system design rule, 75% x 650 = 487 V. If V

RRM

487 V, the L value should be reduced. Therefore, the dI/dt of L and the I

increase as well. Thus, m

But this calculation method does not optimize the inductance L and its size. Ultimately, a

good rating should minimize L size. ST has developed a software tool using all the

parameters: the I

tolerances, and the switch-on power losses. This tool is proposed to help designers to

choose the best L inductance for its application. Ta bl e 2 shows two PFC examples using the

2

BC

concept.

Table 2. Inductor and size versus the PFC types

Input power 100 W < Pin < 1.1 kW 50 W < Pin < 450 W

V

RMS 90V < V

mains

V

OUT

Fs 95 kHz 95 kHz

and m1 are calculated taking into account the corresponding IRM of

2

B, VRDB

and m2 should be recalculated to get V

1

diode of DB versus the dI/dt and junction TJ, the L inductance

RM

_reverse, must not exceed 75%

RDB_reverse

RDB_reverse

is higher than

diode of DB

RM

below 487 V.

Case 1 Case 2

rms < 264 V 90 V <V

mains

rms< 264 V

mains

400 V 400 V

Inductor and size

Core reference

2.6 Range of products

ST offers the BC2 technology in a range of products:

● STTH8BC065DI, STTH8BC060D, STTH5BCF060 for applications from 800 W to 2 kW

● STTH16BC065CT, STTH5BCF060 for applications from 400 W to 1 kW

● STTH10BC065CT + STTH3BCF060U for applications from 280 W to 600 W

3 µH

Core DR78381

(Datatronics Limited)

5 µH

Core DR79124

(Datatronics Limited)

14/22 Doc ID 17975 Rev 1

AN3276 BC2 design in 450 W PFC

3 BC2 design in 450 W PFC

A universal line range 90 to 264 V

switch mode using a standard average current mode PWM has been developed to highlight

the benefits of the BC

2

circuit. Switch-on behavior, efficiencies and thermal measurements

have been compared with 8 A SiC Schottky diodes.

3.1 BC2 design

Specific diodes have been used for the BC2 circuit such as the STTH8BC065 for DB, the

STTH8BC060 for D

provides the L inductance, m

Table 3. N

Fs 72 kHz 140 kHz 200 kHz

N

P

N

S1

N

S2

L 8 µH 5.1 µH 2.7 µH

and the STTH5BCF060 for D1 as shown in Figure 6. The software tool

2

, NS2 and L versus Fs

S1

and m2 versus the switching frequency as given in Ta bl e 3 .

1

2 turns 4 turns 5 turns

8 turns 8 turns 5 turns

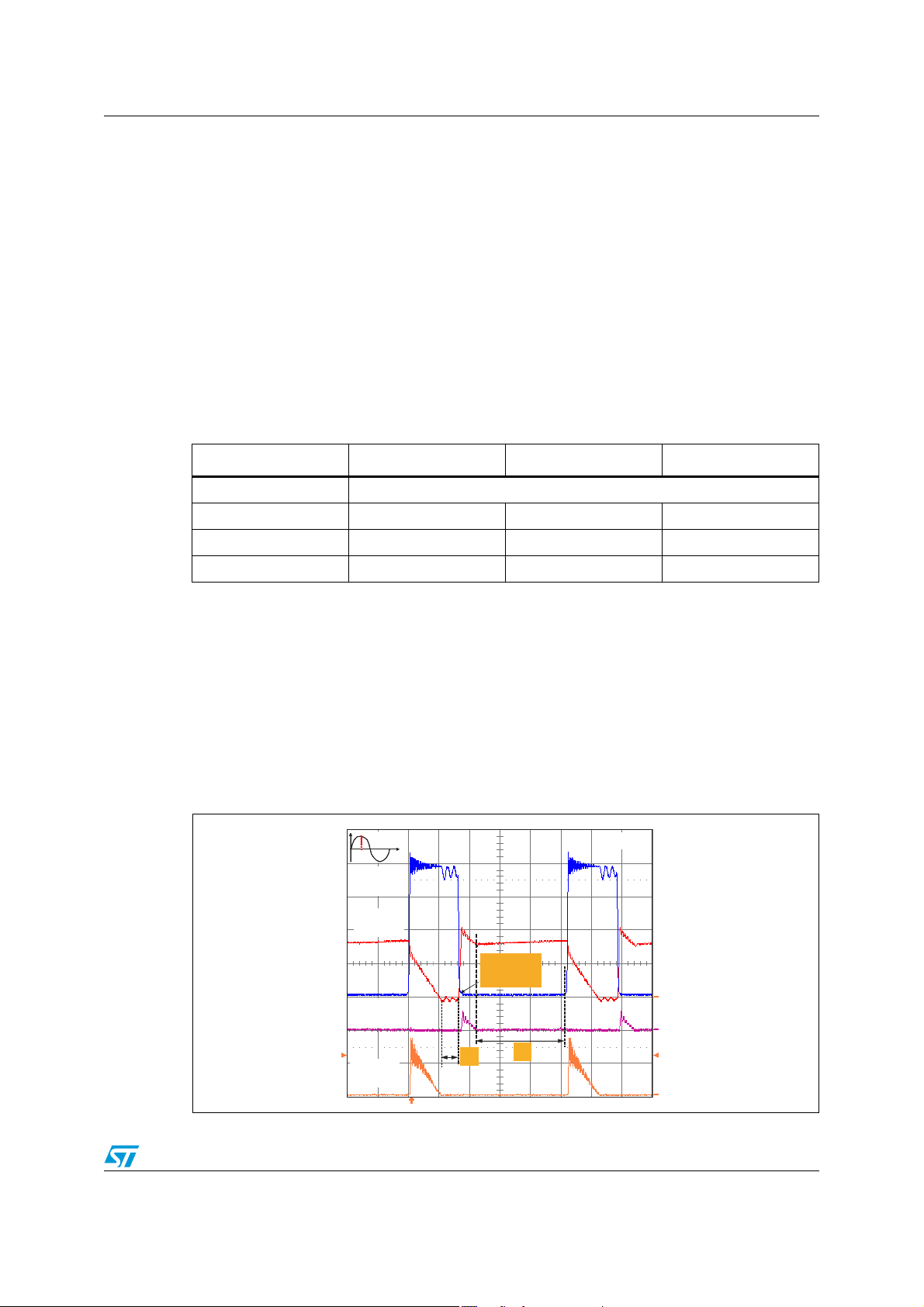

3.2 BC2 typical waveforms

rms 450 W power factor corrector working in hard

mains

52 turns, LB = 600 µH, Tore METGLAS 4520MPEC

Figure 14 shows the typical BC2 waveforms corresponding to a PFC working at 200 kHz.

At each power MOSFET switch-on, soft current switching occurs. This curve highlights that

D

and D2 diodes always work in discontinuous mode; D1 recovers the IRM current from DB

1

whereas D

turns off, the power voltage drain decreases as previously mentioned in the [t

sends the current stored in L through the PFC bulk capacitor. As soon as D2

2

] and [t4-t5]

0-t1

phases and switch-off power losses are saved.

Figure 14. Typical BC

2

waveform at Fs = 200 kHz

Imains(t)

Imains(t)tImains(t)

Tmains

Tmains

t

t

T/4

T/4

V

TR

200V/DIV.

I

L

5A/DIV.

Soft

switching

I

D1

5A/DIV.

t

I

D2

5A/DIV.

D2

1µs/DIV

1 2

3

t

D1

(8t)

4

Doc ID 17975 Rev 1 15/22

BC2 design in 450 W PFC AN3276

3.3 Efficiency comparison

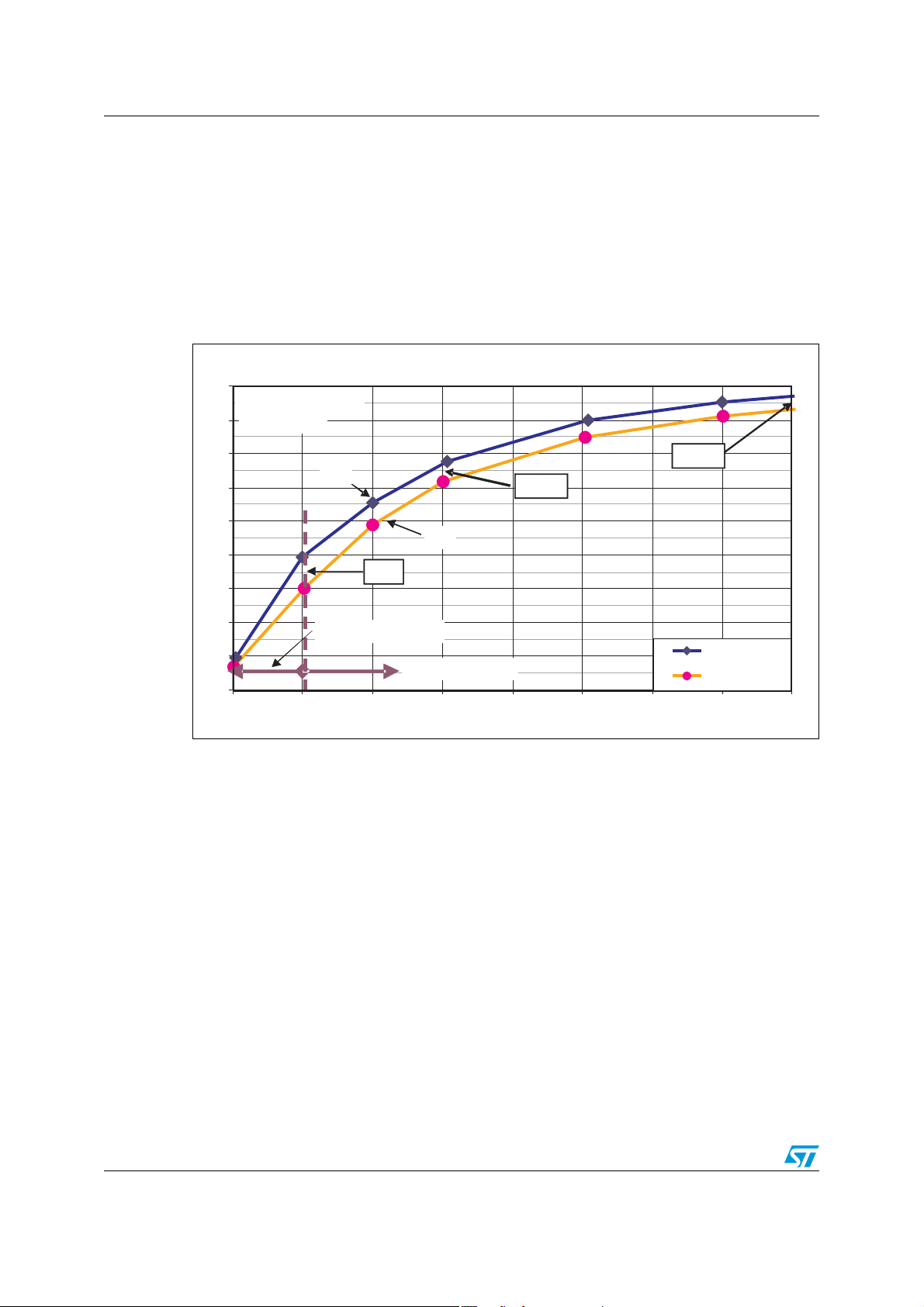

BC2 and SiC diode efficiency have been compared under two V

Figure 15 (230 V

140kHz. At 230V

) and Figure 16 (90 V

RMS

, the BC2 circuit saves up to 2.25 W at full load and 1 W at 100 W

RMS

) with a switching frequency equal to

RMS

compared to the 8 A SiC diode. Under low load, the reflected voltage from N

the BC

phase time [t

the BC

2

efficiency because the switch-off losses are lower than the SiC as described in the

]. As soon as the PFC works in discontinuous mode (< 100 W) the SiC and

0-t1

2

have the same efficiency as shown in Figure 15.

levels as shown in

mains

S2

still improves

Figure 15. Efficiency comparison at 230 V rms

%

97

96

Fs = 140 kHz

95

V = 230 V

mains RMS

Efficiency = f(P )

OUT

+0.5%

BC²

94

93

+0.7%

SiC

92

+1%

91

90

89

88

50 100 150 200 250 300 350 400 450

Discontinuous mode

Continuous mode

BC² solution

8A SIC

P

OUT

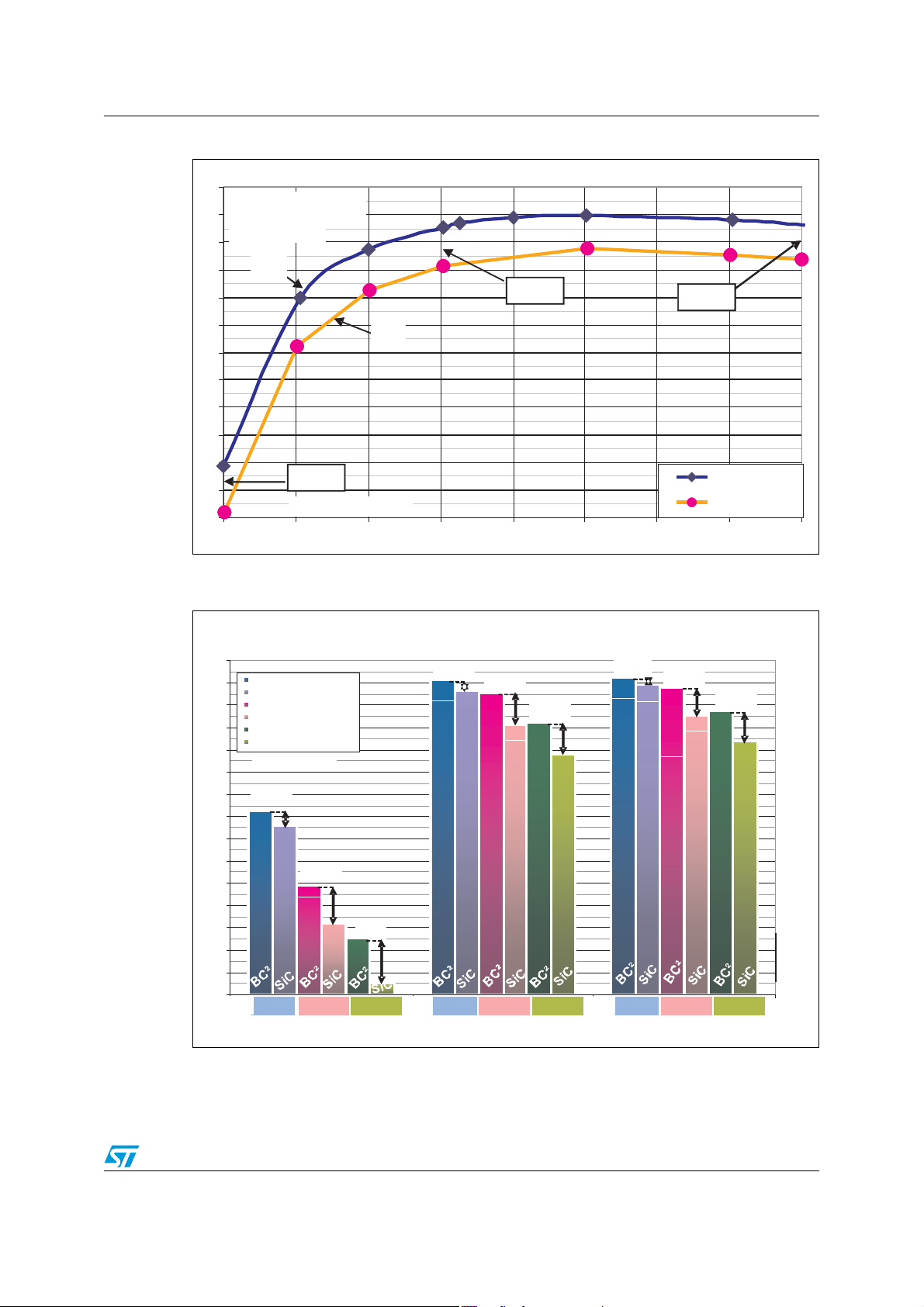

At 90 V rms, the soft switching method benefits plus the power saving in the C

reinforces the benefit of the BC

2

circuit. Up to 5.4 W is saved thanks to the BC2 at 450 W

compared to the SiC diode and under low load, up to 1.7% is saved thanks to the switch-off

power saving.

16/22 Doc ID 17975 Rev 1

discharge

OSS

AN3276 BC2 design in 450 W PFC

Figure 16. Efficiency comparison at 90 V rms

%

95

94

Fs = 140 kHz

93

92

91

V = 90 V

mains RMS

BC²

Efficiency = f(P )

OUT

+1.5%

+1.2%

90

SiC

89

88

87

86

85

84

83

+1.7%

Continuous mode

50 100 150 200 250 300 350 400 450

Figure 17. 450 W PFC efficiency versus three different output powers and three

switching frequencies for V

mains

rms = 90 V

BC² solution

8A SIC

P

OUT

Efficiency=f(POUT,Fs)

%

95

BC² solution 72kHz

94

8A SIC 72kHz

BC² solution 144kHz

93

8A SIC 144kHz

92

BC² solution 200kHz

8A SIC 200kHz

91

Vmains=90VRMS

90

89

+0.7%

88

87

86

85

84

83

82

81

80

FS= FS= FS=

72KHz 72KHz 72KHz140KHz 140KHz 200KHz200KHz 200KHz140KHz

+1.7%

+2%

52 203 400

POUT=50W

Figure 17 highlights the benefit of the BC

Efficiency=f(POUT,Fs)

+0.5%

+1.5%

POUT=200W

2

circuit soft switching method added to its C

discharge power saving especially at low load.

+1.6%

+0.4%

+1.2%

POUT=400W

+1.5%

POUT

OSS

Doc ID 17975 Rev 1 17/22

BC2 design in 450 W PFC AN3276

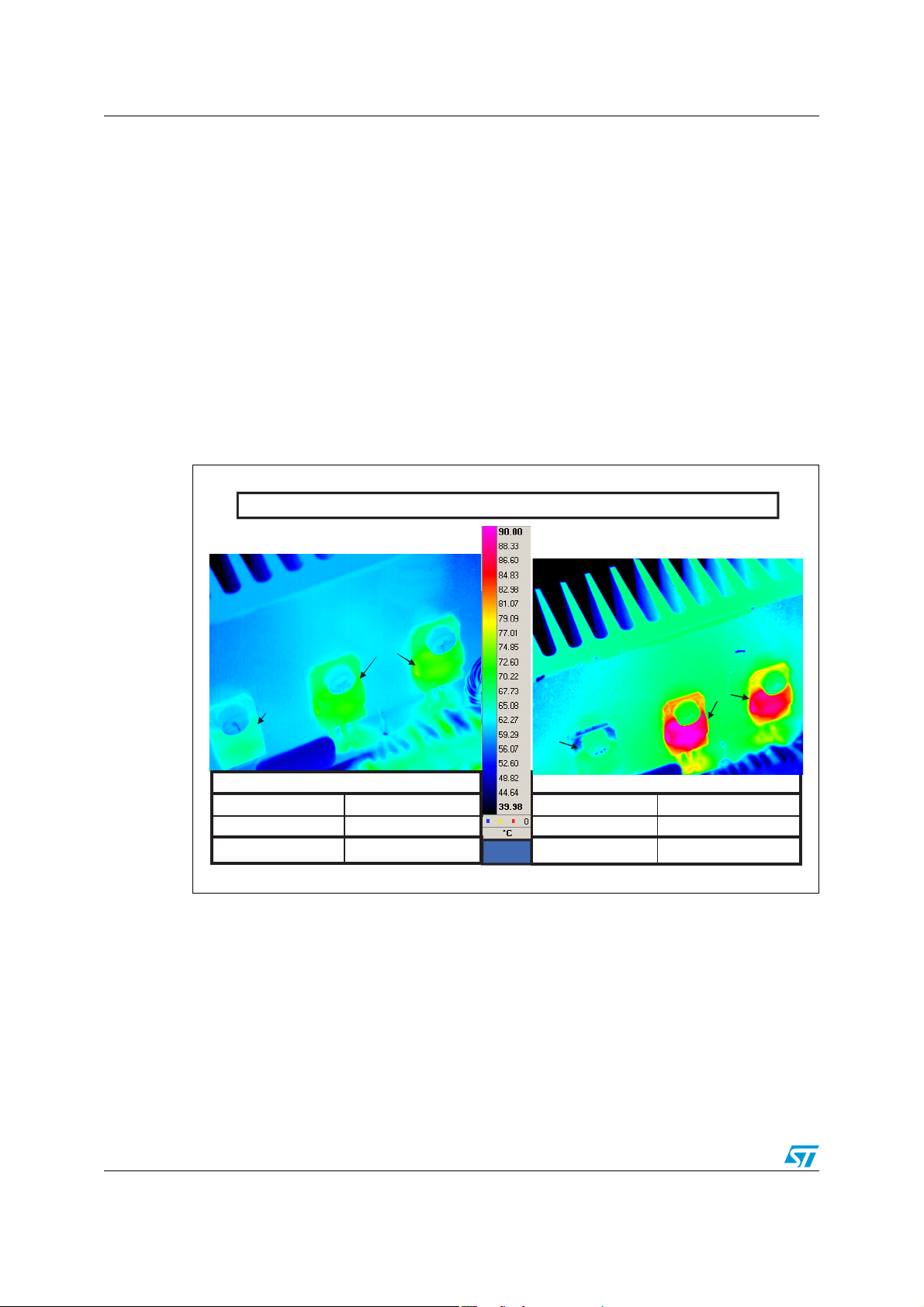

3.4 Thermal measurement

The soft current switching method allows the power dissipation in the switch transistor to be

reduced. Figure 18 shows that a high thermal temperature difference (18 °C) occurs

between the BC

temperature in the power transistor, the size of the thermal heatsink could be reduced. In

this way, the space saving balances out the space from the small L inductor required by the

2

BC

circuit. Therefore, the BC2 circuit can have the same power density as the SiC diode

solution. Nevertheless, the BC

thermal rising. Figure 18 shows that 0.75 W should be removed from the 5.4 W measured in

the efficiency comparison at 90 V rms. Even in this configuration, the BC

better efficiency than the SiC diode. The BC

efficiency criteria than the SiC diode.

Another consideration is that, for the same thermal heatsink, the Power MOSFET size could

be reduced to further reduce the PFC cost.

Figure 18. Thermal measurement comparison

2

and the SiC diode in the PFC application. For the same working junction

2

efficiency decreases due to the power MOSFET R

2

2

circuit has a better power density and

circuit has a

DS(on)

PFC : V = 90 V

STTH8BC065 diode in the BC² circuit

STTH8BC065DI

Power MOS thermal junction measurement

BC² circuit Tj(avg)= 72 °C

Rdson STP20NM50 Rdson= 0.26 Ω

TR Cond. losses (0.26/2)x4.28² =2.38W

mains RMS

STP20NM50

DB

, Fs = 140 kHz ,

STP20NM50

TR

P = 450 W ,

OUT

DB

Power MOS thermal junction measurement

SiC diode Tj(avg)= 90°C

Rdson STP20NM50 Rdson=0.34Ω

+0.75W

TR Cond. losses (0.34/2)x4.28² = 3.12W

I = 4.28 A , Rg = 47

TRRMS 1

STPSC806D diode in the Boost circuit

STP20NM50

TR

STPSC806D

Ω

STP20NM50

18/22 Doc ID 17975 Rev 1

AN3276 Conclusion

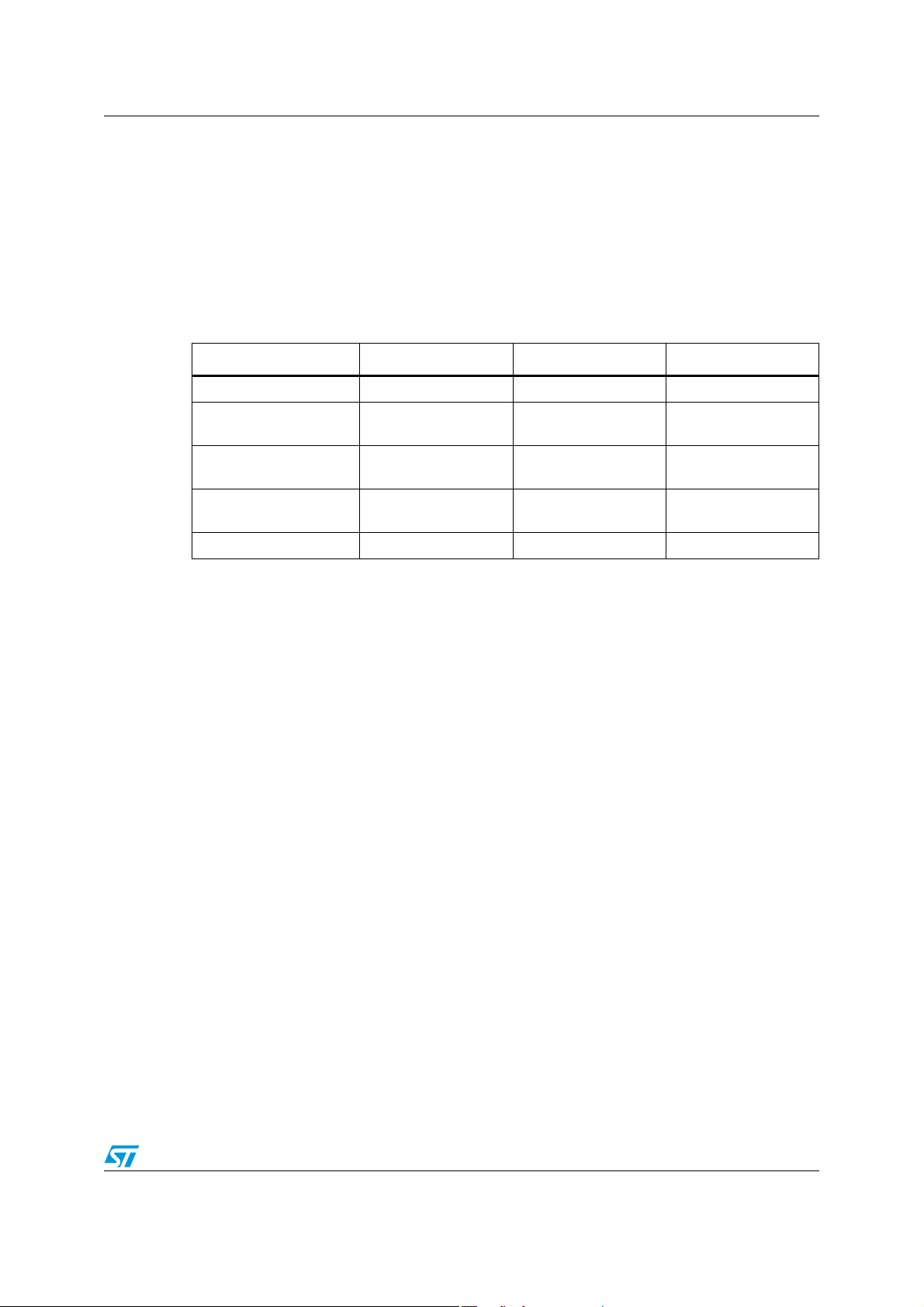

4 Conclusion

The BC2 circuit uses the soft switching method with a unique non-dissipative recovery

circuit. STMicroelectronics has introduced the specific diodes suited for the BC

2

concept to

improve the CCM PFC performance as shown in Ta bl e 4 .

This circuit supports the actual energy efficiency recommendation at 20%, 50% and 100%

of rated power supplies.

Table 4. BC2 benefits in 450 W PFC, 140 kHz

Criteria at 90 V rms SiC diode BC2 circuit Benefits

Efficiency 92.5% 93.7% +1.2%

Power MOSFET

temperature

Power density at

iso-efficiency

EMI

Boost rectification cost > 0.2 € per 100 W >> 0.2 € per 100 W Mass market

90 °C 72 °C -18 °C

State of art Improve, save 5.4 W +1.2% gain

Acceptable with

dI/dt < 1000 A/µs

Acceptable with

dI/dt < 100 A/µs

Soft switching

Doc ID 17975 Rev 1 19/22

References AN3276

5 References

1. Benoît Peron, “Auxiliary switching circuit for a chopping converter”, Patent No: US

6,987,379 B2, June 2006

2. Bertrand Rivet, “New Solution to Optimize Diode Recovery in PFC Boost Converter”,

PCIM 2000.

3. Jim Noon, UC3855A/B High Performance Power Factor Preregulator -Texas

Instrument- application report- SLUA146A

4. Brian T, Irving and M. Jovanovic “Analysis, Design and Performance Evaluation of

Flying-Capacitor Passive Lossless Snubber applied to PFC Boost Converter”, APEC

2002, pp. 503 - 508 vol.1.

20/22 Doc ID 17975 Rev 1

AN3276 Revision history

6 Revision history

Table 5. Document revision history

Date Revision Changes

10-Nov-2010 1 Initial release.

Doc ID 17975 Rev 1 21/22

AN3276

Please Read Carefully:

Information in this document is provided solely in connection with ST products. STMicroelectronics NV and its subsidiaries (“ST”) reserve the

right to make changes, corrections, modifications or improvements, to this document, and the products and services described herein at any

time, without notice.

All ST products are sold pursuant to ST’s terms and conditions of sale.

Purchasers are solely responsible for the choice, selection and use of the ST products and services described herein, and ST assumes no

liability whatsoever relating to the choice, selection or use of the ST products and services described herein.

No license, express or implied, by estoppel or otherwise, to any intellectual property rights is granted under this document. If any part of this

document refers to any third party products or services it shall not be deemed a license grant by ST for the use of such third party products

or services, or any intellectual property contained therein or considered as a warranty covering the use in any manner whatsoever of such

third party products or services or any intellectual property contained therein.

UNLESS OTHERWISE SET FORTH IN ST’S TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF SALE ST DISCLAIMS ANY EXPRESS OR IMPLIED

WARRANTY WITH RESPECT TO THE USE AND/OR SALE OF ST PRODUCTS INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION IMPLIED

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE (AND THEIR EQUIVALENTS UNDER THE LAWS

OF ANY JURISDICTION), OR INFRINGEMENT OF ANY PATENT, COPYRIGHT OR OTHER INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHT.

UNLESS EXPRESSLY APPROVED IN WRITING BY AN AUTHORIZED ST REPRESENTATIVE, ST PRODUCTS ARE NOT

RECOMMENDED, AUTHORIZED OR WARRANTED FOR USE IN MILITARY, AIR CRAFT, SPACE, LIFE SAVING, OR LIFE SUSTAINING

APPLICATIONS, NOR IN PRODUCTS OR SYSTEMS WHERE FAILURE OR MALFUNCTION MAY RESULT IN PERSONAL INJURY,

DEATH, OR SEVERE PROPERTY OR ENVIRONMENTAL DAMAGE. ST PRODUCTS WHICH ARE NOT SPECIFIED AS "AUTOMOTIVE

GRADE" MAY ONLY BE USED IN AUTOMOTIVE APPLICATIONS AT USER’S OWN RISK.

Resale of ST products with provisions different from the statements and/or technical features set forth in this document shall immediately void

any warranty granted by ST for the ST product or service described herein and shall not create or extend in any manner whatsoever, any

liability of ST.

ST and the ST logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of ST in various countries.

Information in this document supersedes and replaces all information previously supplied.

The ST logo is a registered trademark of STMicroelectronics. All other names are the property of their respective owners.

© 2010 STMicroelectronics - All rights reserved

STMicroelectronics group of companies

Australia - Belgium - Brazil - Canada - China - Czech Republic - Finland - France - Germany - Hong Kong - India - Israel - Italy - Japan -

Malaysia - Malta - Morocco - Philippines - Singapore - Spain - Sweden - Switzerland - United Kingdom - United States of America

www.st.com

22/22 Doc ID 17975 Rev 1

Loading...

Loading...