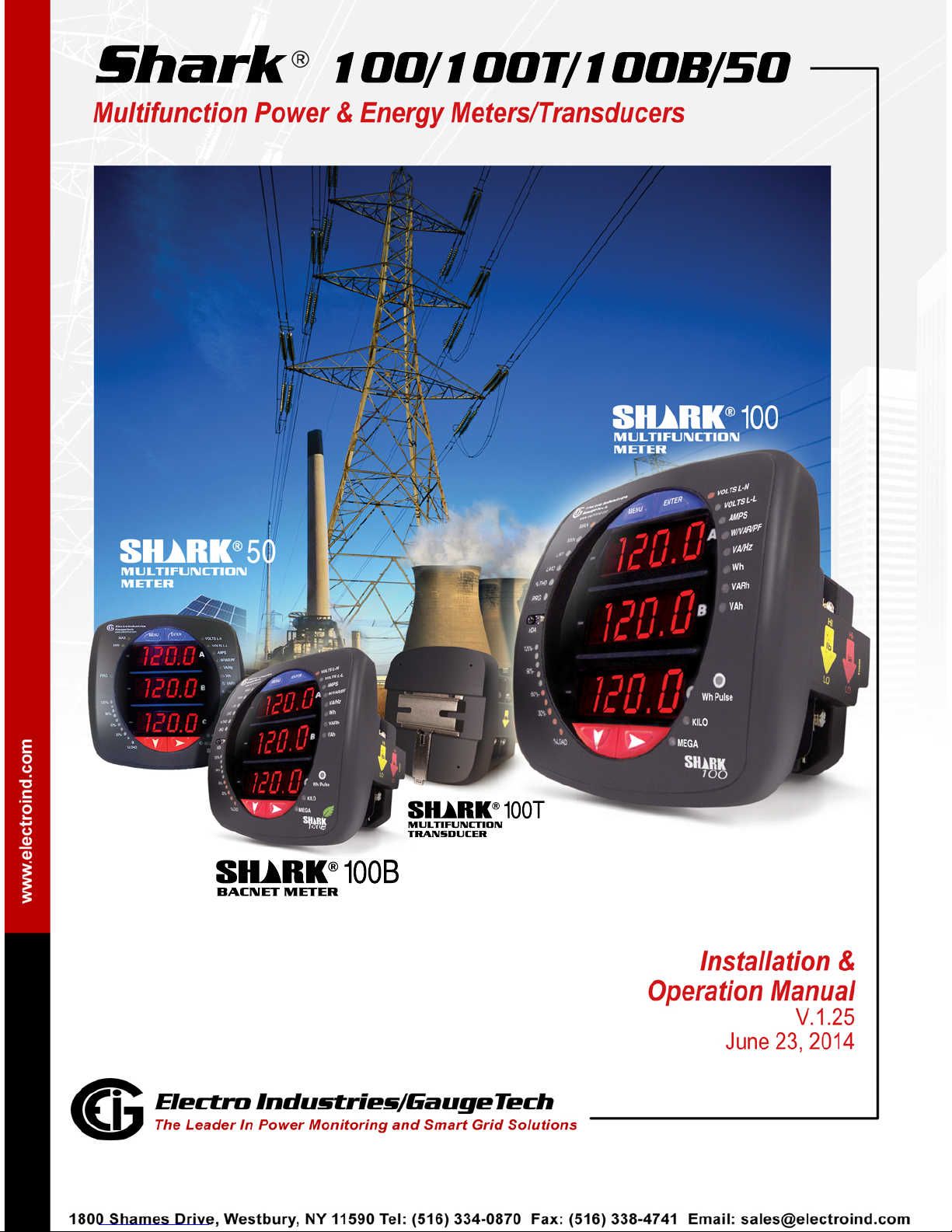

Shark 50, 100, 100T, 100B Installation & Operation Manual

Shark

100/100T/100B/50

MULTIFUNCTION

METER

100

®

MULTIFUNCTION

METER

50

®

BACNET METER

100B

®

MULTIFUNCTION

TRANSDUCER

100T

®

This page intentionally left blank.

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Shark® 100/100T/100B/50 Meter Installation and Operation Manual Version 1.25

Published by:

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

1800 Shames Drive

Westbury, NY 11590

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in

any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or information storage or retrieval systems or any future forms of duplication, for

any purpose other than the purchaser's use, without the expressed written permission

of Electro Industries/GaugeTech.

© 2014 Electro Industries/GaugeTech

Nexus® and Shark® are registered trademarks of Electro Industries/GaugeTech. The

distinctive shape, style, and overall appearances of all Shark® meters are tr ademarks

of Electro Industries/GaugeTech. Communicator EXT

TM

is a trademark of Electro

Industries/GaugeTech.

Windows® is a registered trademark of Microsoft Corporation in the United States

and/or other countries.

BACnet® is a registered trademark of ASHRAE.

Modbus® is a registered trademark of Schneider Electric, licensed to the Modus

Organization, Inc.

Doc# E145701 i

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

This page intentionally left blank.

Doc# E145701 ii

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Customer Service and Support

Customer support is available 9:00 am to 4:30 pm, Eastern Standard Time, Monday

through Friday. Please have the model, serial number and a detai led probl em description available. If the problem concerns a particular reading, please have all meter

readings available. When returning any merchandise to EIG, a return materials

authorization number is required. For customer or technical assistance, repair or

calibration, phone 516-334-0870 or fax 516-338-4741.

Product Warranty

Electro Industries/Gauge Tech warrants all products to be free from defects in material

and workmanship for a period of four years from the date of shipment. During the

warranty period, we will, at our option, either repair or replace any product that

proves to be defective.

To exercise this warranty, fax or call our customer-support department. You will

receive prompt assistance and return instructions. Send the instrument, transportation prepaid, to EIG at 1800 Shames Drive, W estbury, NY 11590. Repairs will be made

and the instrument will be returned.

This warranty does not apply to defects resulting from unauthorized modification,

misuse, or use for any reason other than electrical power monitoring. The Shark

100/100T/100B/50 meter is not a user-serviceable product.

®

THIS WARRANTY IS IN LIEU OF ALL OTHER WARRANTIES, EXPRESSED

OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING ANY IMPLIED WARRANTY OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. ELECTRO INDUSTRIES/

GAUGETECH SHALL NOT BE LIABLE FOR ANY INDIRECT, SPECIAL OR

CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES ARISING FROM ANY AUTHORIZED OR

UNAUTHORIZED USE OF ANY ELECTRO INDUSTRIES/GAUGETECH

PRODUCT. LIABILITY SHALL BE LIMITED TO THE ORIGINAL COST OF

THE PRODUCT SOLD.

Doc# E145701 iii

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Use of Product for Protection

Our products are not to be used for primary over-current protection. Any protection

feature in our products is to be used for alarm or secondary protection only.

Statement of Calibration

Our instruments are inspected and tested in accordance with specifications publi shed

by Electro Industries/GaugeTech. The accuracy and a calibration of our instruments

are traceable to the National Institute of Standards and Technology through

equipment that is calibrated at planned interv als by comparison to certified standards.

For optimal performance, EIG recommends that any meter, including those manufactured by EIG, be verified for accuracy on a yearly interval using NIST traceable accuracy standards.

Disclaimer

The information presented in this publication has been carefully checked for reliability; however, no responsibility is assumed for inaccuracies. The information contained

in this document is subject to change without notice.

This symbol indicates that the operator must refer must to an

important WARNING or CAUTION in the oper ating instructions.

Please see Chapter 4 for important safety information regard-

ing installation and hookup of the Shark® 50/100/100B meter.

Dans ce manuel, ce symbole indique que l’opérateur doit se référer à un important

AVERTISSEMENT ou une MISE EN GARDE dans les instructions opérationnelles. Veuillez consulter le chapitre 4 pour des informations importantes relatives à l’installation

et branchement du compteur.

The following safety symbols may be used on the meter itself:

Les symboles de sécurité suivante peuvent être utilisés sur le compteur même:

This symbol alerts you to the presence of high voltage, which can

cause dangerous electrical shock.

Ce symbole vous indique la présence d’une haute tension qui peut

provoquer une décharge électrique dangereuse.

This symbol indicates the field wiring terminal that must be connected

to earth ground before operating the meter, which protects against

electrical shock in case of a fault condition.

Doc# E145701 iv

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Ce symbole indique que la borne de pose des canalisations in-situ qui doit être

branchée dans la mise à terre avant de faire fonctionner le compteur qui est protégé

contre une décharge électrique ou un état défectueux.

This symbol indicates that the user must refer to this manual for

specific WARNING or CAUTION information to avoid personal injury or

damage to the product.

Ce symbole indique que l'utilisateur doit se référer à ce manuel pour AVERTISSEMENT

ou MISE EN GARDE l'information pour éviter toute blessure ou tout endommagement

du produit.

About Electro Industries/GaugeTech (EIG)

Founded in 1975 by engineer and inventor Dr. Samuel Kagan, Electro Industries/

Gauge Tech changed the face of power monitoring forever with its first breakthrough

innovation: an affordable, easy-to-use AC power meter.

Thirty years since its founding, Electro Industries/GaugeTech, the leader in power

monitoring and control, continues to revolutionize the industry with the highest quality, cutting edge power monitoring and control technology on the market today. An

ISO 9001:2000 certified company, EIG sets the industry standard for advanced power

quality and reporting, revenue metering and substation data acquisition and control.

EIG products can be found on site at mainly all of today's leading manufacturers,

industrial giants and utilities.

EIG products are primarily designed, manufactured, tested and calibrated at our facility in Westbury, New York.

Doc# E145701 v

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

This page intentionally left blank.

Doc# E145701 vi

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Table of Contents

Customer Service and Support iii

Product Warranty iii

Use of Product for Protection iv

Statement of Calibration iv

Disclaimer iv

About Electro Industries/GaugeTech (EIG) v

1: Three-Phase Power Measurement 1-1

1.1: Three-Phase System Configurations 1-1

Table of Contents

1.1.1: Wye Connection 1-1

1.1.2: Delta Connection 1-4

1.1.3: Blondel’s Theorem and Three Phase Measurement 1-6

1.2: Power, Energy and Demand 1-8

1.3: Reactive Energy and Power Factor 1-12

1.4: Harmonic Distortion 1-14

1.5: Power Quality 1-17

2: Meter Overview and Specifications 2-1

2.1: Hardware Overview 2-1

2.1.1: Voltage and Current Inputs 2-3

2.1.2: Model Number plus Option Numbers 2-4

2.1.3: V-Switch

TM

Technology 2-6

2.1.4: Measured Values 2-8

2.1.5: Utility Peak Demand 2-9

Doc# E145701 TOC - 1

Table of Contents

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

2.2: Specifications 2-9

2.3: Compliance 2-15

2.4: Accuracy 2-16

3: Mechanical Installation 3-1

3.1: Introduction 3-1

3.2: ANSI Installation Steps 3-4

3.3: DIN Installation Steps 3-5

3.4: Shark® 100T Transducer Installation 3-6

4: Electrical Installation 4-1

4.1: Considerations When Installing Meters 4-1

4.2: CT Leads Terminated to Meter 4-4

4.3: CT Leads Pass Through (No Meter Termination) 4-5

4.4: Quick Connect Crimp-on Terminations 4-6

4.5: Voltage and Power Supply Connections 4-7

4.6: Ground Connections 4-7

4.7: Voltage Fuses 4-7

4.8: Electrical Connection Diagrams 4-8

4.9: Extended Surge Protection for Substation Instrumentation 4-21

5: Communication Installation 5-1

5.1: Shark® 100/50 Meter Serial Based Communication 5-1

5.1.1: IrDA Port (Com 1) 5-2

5.1.2: RS485/KYZ Output Com 2 (485P Option) 5-3

5.1.2.1: Using the Unicom 2500 5-7

Doc# E145701 TOC - 2

Table of Contents

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

5.2: Configuring the Shark® 100 - INP10

Ethernet Connection 5-8

5.2.1: Setting up the Host PC to Communicate with

the Shark® 100 - INP10 meter 5-9

5.2.1.1: Configuring the Host PC's Ethernet Adapter through

Windows© 5-9

5.2.2: Setting up the Shark® 100 - INP10 Meter

for Ethernet Communication 5-11

5.2.2.1: Configuring the Shark® 100 - INP10 Meter's

Ethernet Connection on the Host Computer 5-12

5.2.2.2: Resetting the Ethernet Card (INP10) 5-14

5.3: Shark® 100B Meter Ethernet Configuration 5-14

6: Using the Shark® 100/50 Meter 6-1

6.1: Programming the Shark® 100/100B/50 Meter Using the

Faceplate 6-1

6.1.1: Understanding Meter Face Elements 6-1

6.1.2: Understanding Meter Face Buttons 6-2

6.2: Using the Front Panel 6-3

6.2.1: Understanding Startup and Default Displays 6-3

6.2.2: Using the Main Menu 6-4

6.2.3: Using Reset Mode 6-5

6.2.4: Entering a Password 6-6

6.2.5: Using Configuration Mode 6-7

6.2.5.1: Configuring the Scroll Feature 6-9

6.2.5.2: Configuring CT Setting 6-10

Doc# E145701 TOC - 3

Table of Contents

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

6.2.5.3: Configuring PT Setting 6-11

6.2.5.4: Configuring Connection Setting 6-13

6.2.5.5: Configuring Communication Port Setting 6-13

6.2.6: Using Operating Mode 6-15

6.3: Understanding the % of Load Bar 6-16

6.4: Performing Watt-Hour Accuracy Testing (Verification) 6-17

6.5: Programming the Transducer or Meter Using Software 6-19

6.5.1: Accessing the Transducer/Meter in Default

Communication Mode (RS485 Communication) 6-19

6.5.2: Connecting to the Transducer/Meter through

Communicator EXT

TM

Software 6-20

6.5.3: Device Profile Settings 6-24

7: Using the Shark® 100B Meter 7-1

7.1: Introduction 7-1

7.1.1: About BACnet 7-1

7.2: Shark® 100B meter’s BACnet Objects 7-2

7.3: Configuring the Shark® 100B Meter 7-5

7.4: Using the Shark® 100B Meter’s Web Interface 7-12

7.5: Using the Shark® 100B in a BACnet Application 7-18

A: Shark® 100/50 Meter Navigation Maps A-1

A.1: Introduction A-1

A.2: Navigation Maps (Sheets 1 to 4) A-1

B: Shark® 100 and 50 Meter Modbus Map B-1

B.1: Introduction B-1

Doc# E145701 TOC - 4

Table of Contents

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

B.2: Modbus Register Map Sections B-1

B.3: Data Formats B-1

B.4: Floating Po i nt Values B-2

B.5: Modbus Register Map B-3

C: Shark® 100 Meter DNP Map C-1

C.1: Introduction C-1

C.2: DNP Mapping (DNP-1 to DNP-2) C-1

D: DNP 3.0 Protocol Assignments D-1

D.1: DNP Implementation D-1

D.2: Data Link Layer D-2

D.3: Transport Layer D-3

D.4: Application Layer D-3

D.4.1: Object and Va riation D-4

D.4.1.1: Binary Output Status (Obj. 10, Var. 2) D-5

D.4.1.2: Control Relay Output Block (Obj. 12, Var. 1) D-6

D.4.1.3: 32-Bit Binary Counter Without Flag (Obj. 20, Var. 5) D-7

D.4.1.4: 16-Bit Analog Input Without Flag (Obj. 30, Var. 4) D-7

D.4.1.5: Class 0 Data (Obj. 60, Var. 1) D-13

D.4.1.6: Internal Indications (Obj. 80, Var. 1) D-13

E: Using the USB to IrDA Adapter CAB6490 E-1

E.1: Introduction E-1

E.2: Installation Procedures E-1

Doc# E145701 TOC - 5

Table of Contents

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

This page intentionally left blank.

Doc# E145701 TOC - 6

1: Three-Phase Power Measurement

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

1: Three-Phase Power Measurement

This introduction to three-phase power and power measurement is intended to

provide only a brief overview of the subject. The professional meter engineer or meter

technician should refer to more advanced documents such as the EEI Handbook for

Electricity Metering and the application standards for more in-depth and technical

coverage of the subject.

1.1: Three-Phase System Configurations

Three-phase power is most commonly used in situations where large amounts of

power will be used because it is a more effective way to transmit the power and

because it provides a smoother delivery of power to the end load. There are two

commonly used connections for three-phase power, a wye connection or a delta

connection. Each connection has several different manifestations in actual use.

When attempting to determine the type of connection in use, it is a good practice to

follow the circuit back to the transformer that is serving the circuit. It is often not

possible to conclusively determine the correct circuit connection simply by counting

the wires in the service or checking voltages. Checking the transformer connection

will provide conclusive evidence of the circuit connection and the relationships

between the phase voltages and ground.

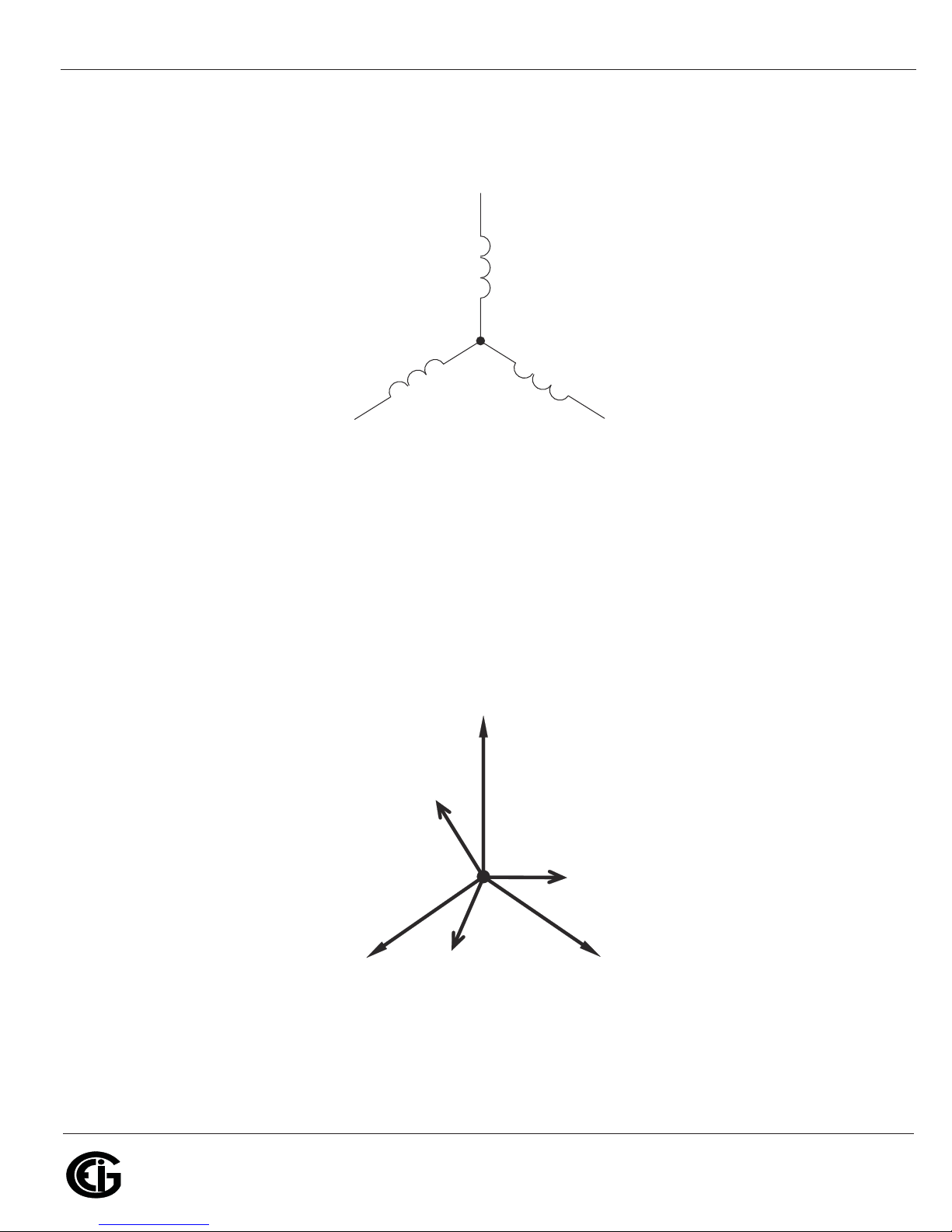

1.1.1: Wye Connection

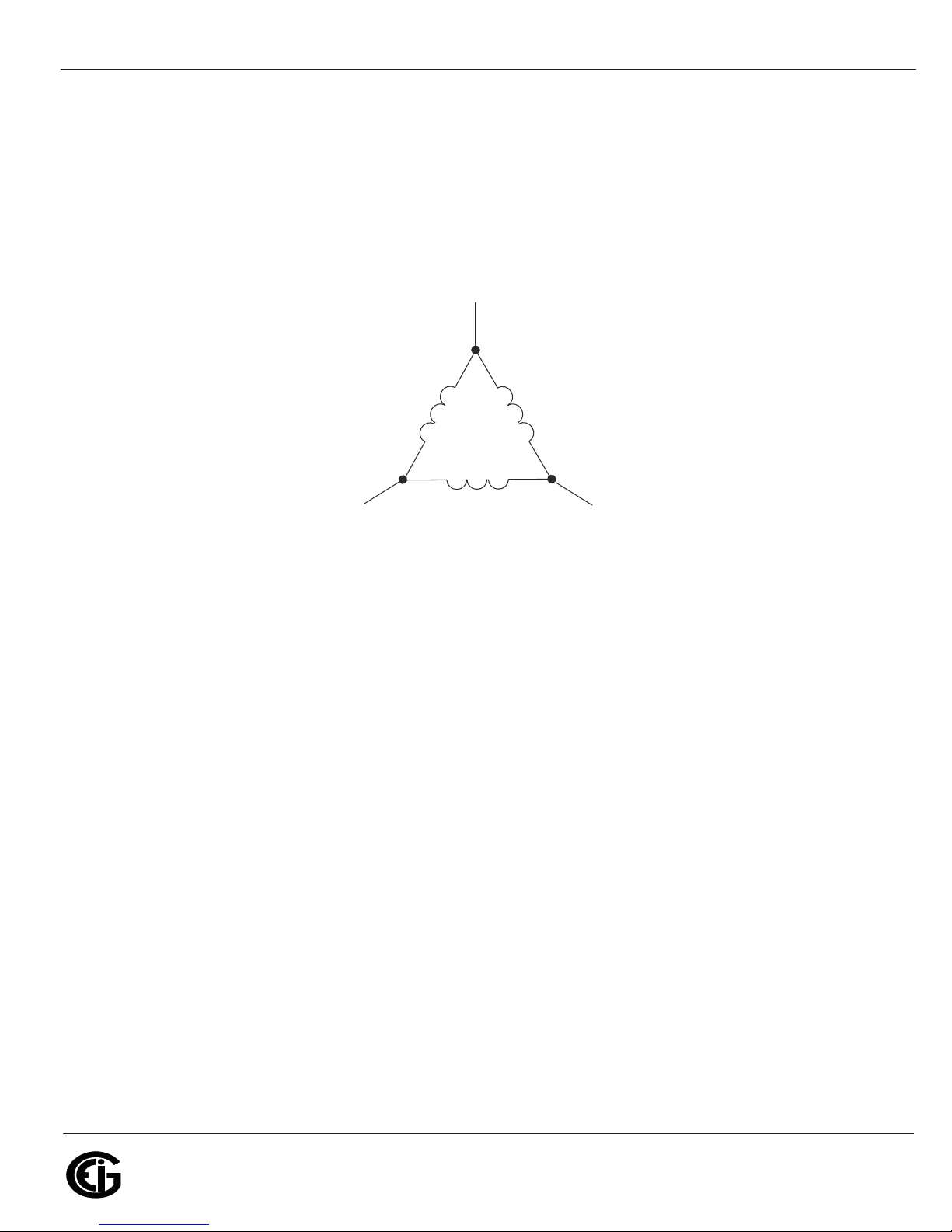

The wye connection is so called because when you look at the phase relationships and

the winding relationships between the phases it looks like a Y. Figure 1.1 depicts the

winding relationships for a wye-connected service. In a wye service the neutral (or

center point of the wye) is typically grounded. This leads to common voltages of 208/

120 and 480/277 (where the first number represents the phase-to-phase voltage and

the second number represents the phase-to-ground voltage).

Doc# E145701 1-1

1: Three-Phase Power Measurement

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

V

A

V

B

Phase 3

Phase 2

V

B

Figure 1.1: Three-phase Wye Winding

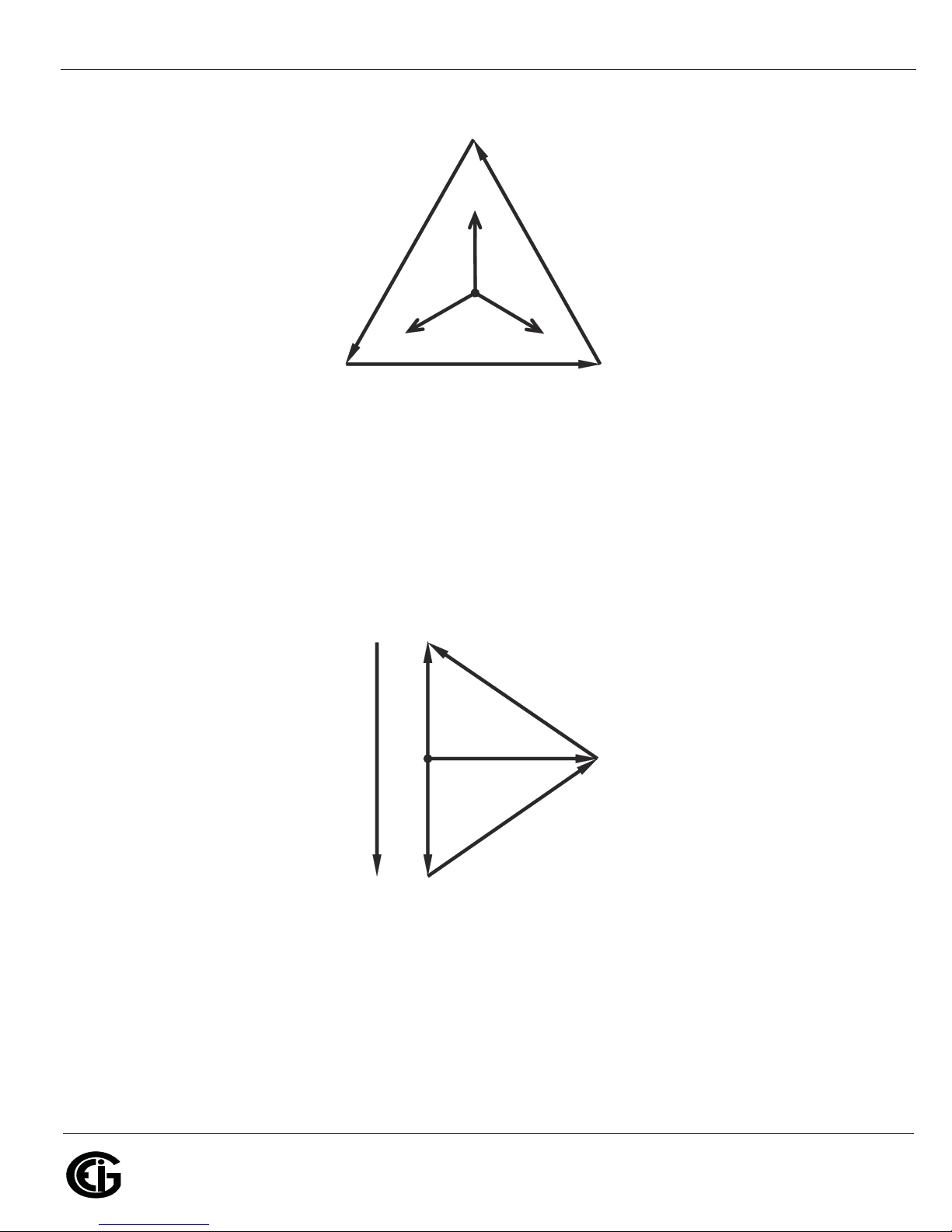

The three voltages are separated by 120o electrically. Under balanced load conditions

the currents are also separated by 120

conditions can cause the currents to depart from the ideal 120

V

C

N

Phase 1

o

. However, unbalanced loads and other

V

A

o

separation. Three-

phase voltages and currents are usually represented with a phasor diagram. A phasor

diagram for the typical connected voltages and currents is shown in Figure 1.2.

V

C

I

C

N

I

A

I

B

Figure 1.2: Phasor Diagram Showing Three-phase Voltages and Currents

Doc# E145701 1-2

1: Three-Phase Power Measurement

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

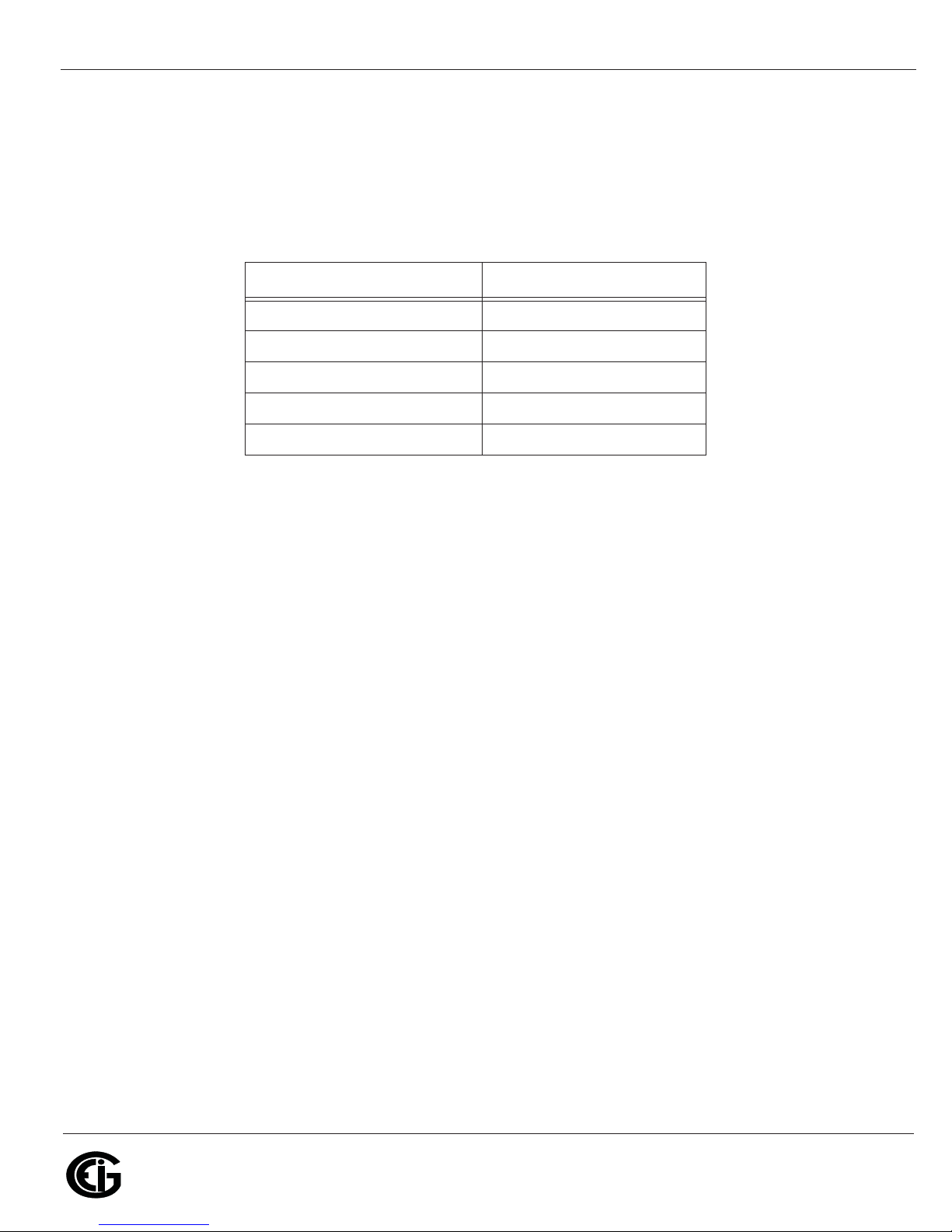

The phasor diagram shows the 120o angular separation between the phase voltages.

The phase-to-phase voltage in a balanced three-phase wye system is 1.732 times the

phase-to-neutral voltage. The center point of the wye is tied together and is typically

grounded. Table 1.1 shows the common voltages used in the United States for wye-

connected systems.

Phase to Ground Voltage Phase to Phase Voltage

120 volts 208 volts

277 volts 480 volts

2,400 volts 4,160 volts

7,200 volts 12,470 volts

7,620 volts 13,200 volts

Table 1: Common Phase Voltages on Wye Services

Usually a wye-connected service will have four wires: three wires for the phases and

one for the neutral. The three-phase wires connect to the three phases (as shown in

Figure 1.1). The neutral wire is typically tied to the ground or center point of the wye.

In many industrial applications the facility will be fed with a four-wire wye service but

only three wires will be run to individual loads. The load is then often referred to as a

delta-connected load but the service to the facility is still a wye service; it contains

four wires if you trace the circuit back to its source (usually a transformer). In this

type of connection the phase to ground voltage will be the phase-to-ground voltage

indicated in Table 1, even though a neutral or ground wire is not physically present at

the load. The transformer is the best place to determine the circuit connection type

because this is a location where the voltage reference to ground can be conclusively

identified.

Doc# E145701 1-3

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

1.1.2: Delta Connection

V

A

V

B

Delta-connected services may be fed with either three wires or four wires. In a three-

phase delta service the load windings are connected from phase-to-phase rather than

from phase-to-ground. Figure 1.3 shows the physical load connections for a delta

service.

V

1: Three-Phase Power Measurement

C

Phase 2

Phase 1

Figure 1.3: Three-phase Delta Winding Relationship

In this example of a delta service, three wires will transmit the power to the load. In a

true delta service, the phase-to-ground voltage will usually not be balanced because

the ground is not at the center of the delta.

Figure 1.4 shows the phasor relationships between voltage and current on a three-

phase delta circuit.

In many delta services, one corner of the delta is grounded. This means the phase to

ground voltage will be zero for one phase and will be full phase-to-phase voltage for

the other two phases. This is done for protective purposes.

Phase 3

Doc# E145701 1-4

1: Three-Phase Power Measurement

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

V

A

V

BC

Figure 1.4: Phasor Diagram, Three-Phase Voltages and Currents, Delta-Connected

Another common delta connection is the four-wire, grounded delta used for lighting

loads. In this connection the center point of one winding is grounded. On a 120/240

volt, four-wire, grounded delta service the phase-to-ground voltage would be 120

volts on two phases and 208 volts on the third phase. Figure 1.5 shows the phasor

diagram for the voltages in a three-phase, four-wire delta system.

V

I

C

I

B

V

AB

C

V

CA

I

A

V

CA

V

BC

Doc# E145701 1-5

Figure 1.5: Phasor Diagram Showing Three-phase Four-Wire Delta-Connected System

N

V

AB

V

B

1: Three-Phase Power Measurement

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

1.1.3: Blondel’s Theorem and Three Phase Measurement

In 1893 an engineer and mathematician named Andre E. Blondel set forth the first

scientific basis for polyphase metering. His theorem states:

If energy is supplied to any system of conductors through N wires, the total power in

the system is given by the algebraic sum of the readings of N wattmeters so arranged

that each of the N wires contains one current coil, the corresponding potential coil

being connected between that wire and some common point. If this common point is

on one of the N wires, the measurement may be made by the use of N-1 Wattmeters.

The theorem may be stated more simply, in modern language:

In a system of N conductors, N-1 meter elements will measure the power or energy

taken provided that all the potential coils have a common tie to the conductor in

which there is no current coil.

Three-phase power measurement is accomplished by measuring the three individual

phases and adding them together to obtain the total three phase value. In older

analog meters, this measurement was accomplished using up to three separate

elements. Each element combined the single-phase voltage and current to produce a

torque on the meter disk. All three elements were arranged around the disk so that

the disk was subjected to the combined torque of the three elements. As a result the

disk would turn at a higher speed and register power supplied by each of the three

wires.

According to Blondel's Theorem, it was possible to reduce the number of elements

under certain conditions. For example, a three-phase, three-wire delta system could

be correctly measured with two elements (two potential coils and two current coils) if

the potential coils were connected between the three phases with one phase in

common.

In a three-phase, four-wire wye system it is necessary to use three elements. Three

voltage coils are connected between the three phases and the common neutral

conductor. A current coil is required in each of the three phases.

In modern digital meters, Blondel's Theorem is still applied to obtain proper

metering. The difference in modern meters is that the digital meter measures each

phase voltage and current and calculates the single-phase power for each phase. The

meter then sums the three phase powers to a single three-phase reading.

Doc# E145701 1-6

1: Three-Phase Power Measurement

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Some digital meters measure the individual phase power values one phase at a time.

This means the meter samples the voltage and current on one phase and calculates a

power value. Then it samples the second phase and calculates the power for the

second phase. Finally, it samples the third phase and calculates that phase power.

After sampling all three phases, the meter adds the three readings to create the

equivalent three-phase power value. Using mathematical averaging techniques, this

method can derive a quite accurate measurement of three-phase power.

More advanced meters actually sample all three phases of voltage and current

simultaneously and calculate the individual phase and three-phase power values. The

advantage of simultaneous sampling is the reduction of error introduced due to the

difference in time when the samples were taken.

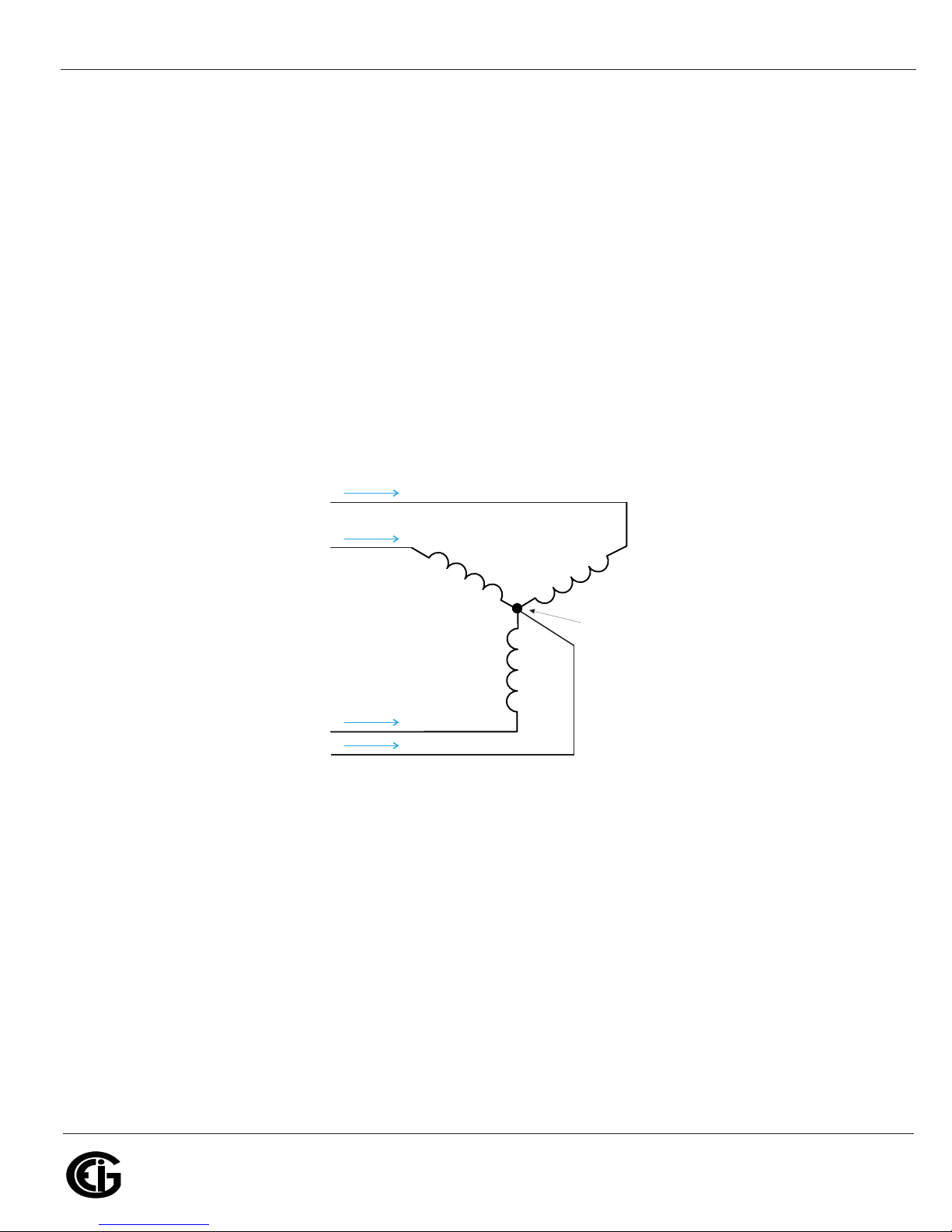

C

B

A

N

Figure 1.6: Three-Phase Wye Load Illustrating Kirchhoff’s Law and Blondel’s Theorem

Phase B

Phase C

Node "n"

Phase A

Blondell's Theorem is a derivation that results from Kirchhoff's Law. Kirchhoff's Law

states that the sum of the currents into a node is zero. Another way of stating the

same thing is that the current into a node (connection point) must equal the current

out of the node. The law can be applied to measuring three-phase loads. Figure 1.6

shows a typical connection of a three-phase load applied to a three-phase, four-wire

service. Kirchhoff's Law holds that the sum of currents A, B, C and N must equal zero

or that the sum of currents into Node "n" must equal zero.

If we measure the currents in wires A, B and C, we then know the current in wire N by

Kirchhoff's Law and it is not necessary to measure it. This fact leads us to the

conclusion of Blondel's Theorem- that we only need to measure the power in three of

Doc# E145701 1-7

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

the four wires if they are connected by a common node. In the circuit of Figure 1.6 we

must measure the power flow in three wires. This will require three voltage coils and

three current coils (a three-element meter). Similar figures and conclusions could be

reached for other circuit configurations involving Delta-connected loads.

1.2: Power, Energy and Demand

It is quite common to exchange power, energy and demand without differentiating

between the three. Because this practice can lead to confusion, the differences

between these three measurements will be discussed.

Power is an instantaneous reading. The power reading provided by a meter is the

present flow of watts. Power is measured immediately just like current. In many

digital meters, the power value is actually measured and calculated over a one second

interval because it takes some amount of time to calculate the RMS values of voltage

1: Three-Phase Power Measurement

and current. But this time interval is kept small to preserve the instantaneous nature

of power.

Energy is always based on some time increment; it is the integration of power over a

defined time increment. Energy is an important value because almost all electric bills

are based, in part, on the amount of energy used.

Typically, electrical energy is measured in units of kilowatt-hours (kWh). A kilowatt-

hour represents a constant load of one thousand watts (one kilowatt) for one hour.

Stated another way, if the power delivered (instantaneous watts) is measured as

1,000 watts and the load was served for a one hour time interval then the load would

have absorbed one kilowatt-hour of energy. A different load may have a constant

power requirement of 4,000 watts. If the load were served for one hour it would

absorb four kWh. If the load were served for 15 minutes it would absorb ¼ of that

total or one kWh.

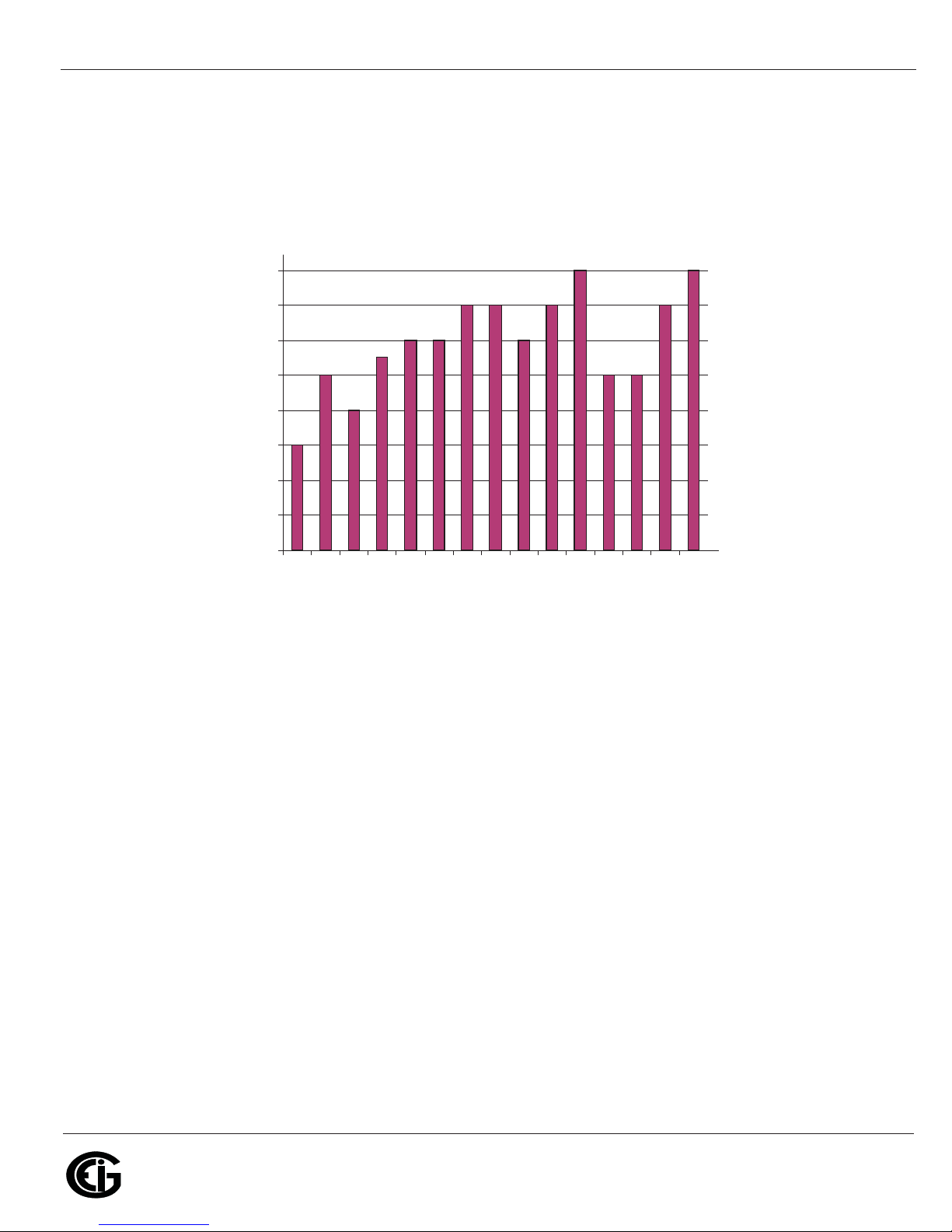

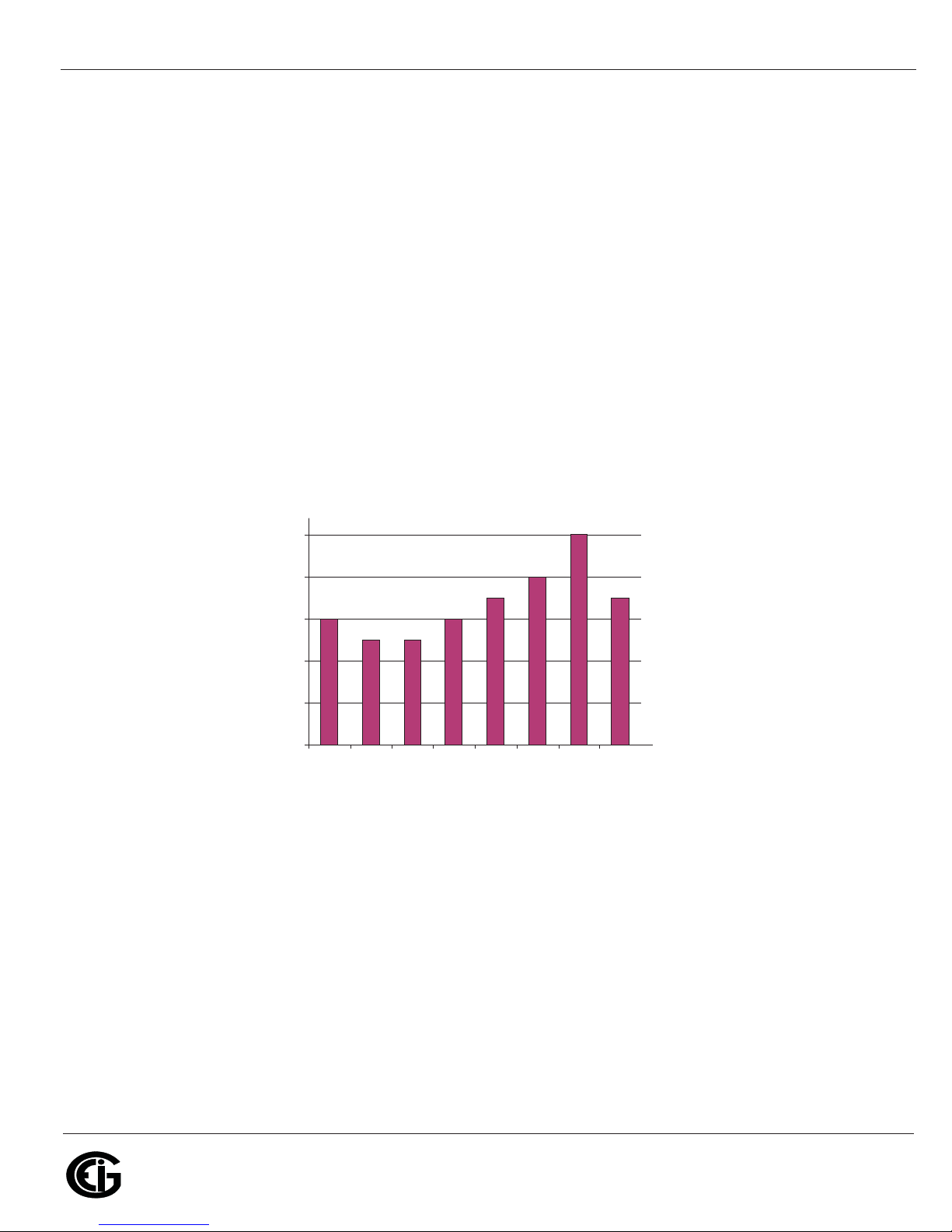

Figure 1.7 shows a graph of power and the resulting energy that would be transmitted

as a result of the illustrated power values. For this illustration, it is assumed that the

power level is held constant for each minute when a measurement is taken. Each bar

in the graph will represent the power load for the one-minute increment of time. In

real life the power value moves almost constantly.

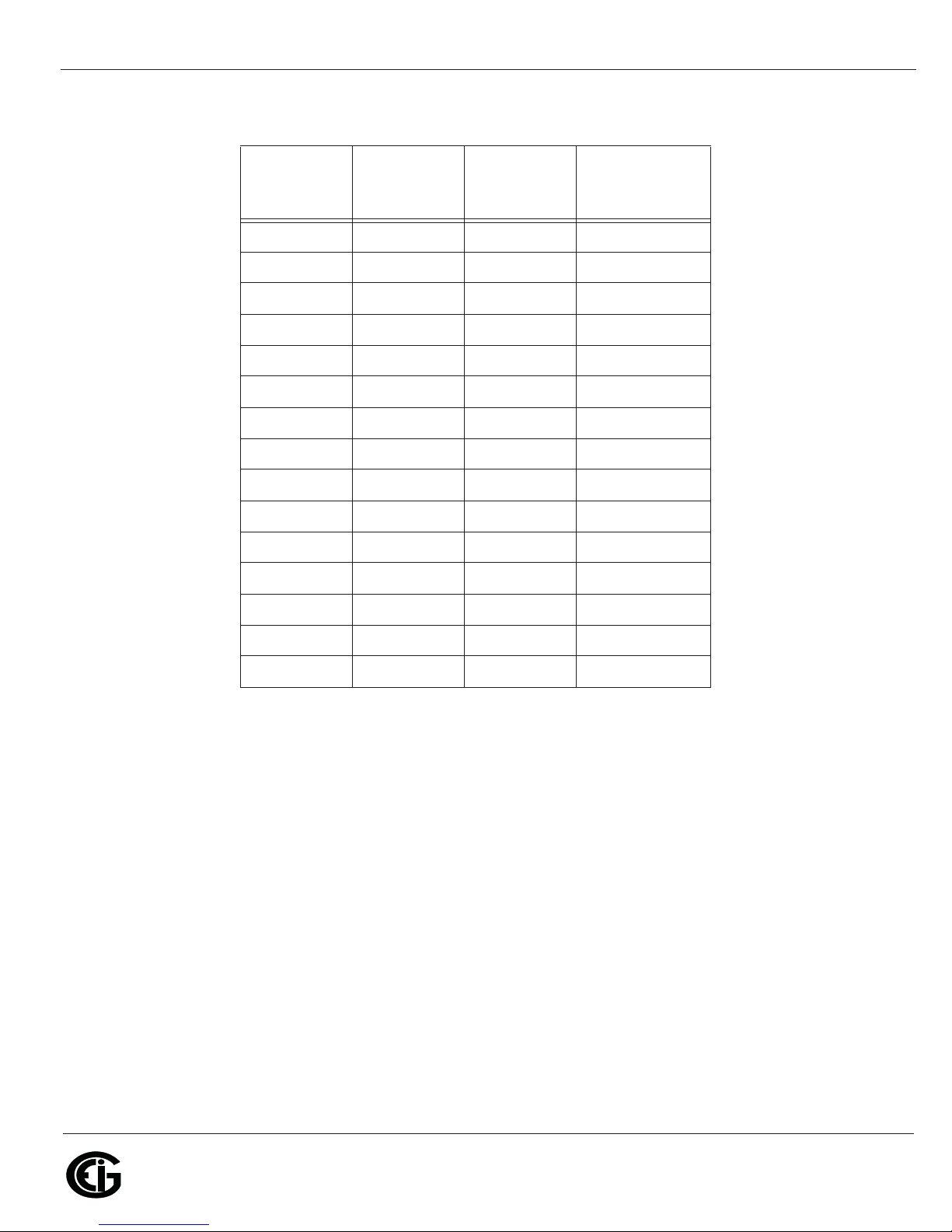

The data from Figure 1.7 is reproduced in Table 2 to illustrate the calculation of

energy. Since the time increment of the measurement is one minute and since we

Doc# E145701 1-8

1: Three-Phase Power Measurement

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

Time (minutes)

sttawolik

specified that the load is constant over that minute, we can convert the power reading

to an equivalent consumed energy reading by multiplying the power reading times 1/

60 (converting the time base from minutes to hours).

Figure 1.7: Power Use over Time

Doc# E145701 1-9

1: Three-Phase Power Measurement

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Time

Interval

(minute)

Power

(kW)

Energy

(kWh)

Accumulated

1 30 0.50 0.50

2 50 0.83 1.33

3 40 0.67 2.00

4 55 0.92 2.92

5 60 1.00 3.92

6 60 1.00 4.92

7 70 1.17 6.09

8 70 1.17 7.26

9 60 1.00 8.26

10 70 1.17 9.43

11 80 1.33 10.76

12 50 0.83 12.42

13 50 0.83 12.42

Energy

(kWh)

14 70 1.17 13.59

15 80 1.33 14.92

Table 1.2: Power and Energy Relationship over Time

As in Table 1.2, the accumulated energy for the power load profile of Figure 1.7 is

14.92 kWh.

Demand is also a time-based value. The demand is the average rate of energy use

over time. The actual label for demand is kilowatt-hours/hour but this is normally

reduced to kilowatts. This makes it easy to confuse demand with power, but demand

is not an instantaneous value. To calculate demand it is necessary to accumulate the

energy readings (as illustrated in Figure 1.7) and adjust the energy reading to an

hourly value that constitutes the demand.

In the example, the accumulated energy is 14.92 kWh. But this measurement was

made over a 15-minute interval. To convert the reading to a demand value, it must be

normalized to a 60-minute interval. If the pattern were repeated for an additional

three 15-minute intervals the total energy would be four times the measured value or

Doc# E145701 1-10

1: Three-Phase Power Measurement

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

0

20

40

60

80

100

12345678

Intervals (15 mins.)

sruoh-ttawolik

59.68 kWh. The same process is applied to calculate the 15-minute demand value.

The demand value associated with the example load is 59.68 kWh/hr or 59.68 kWd.

Note that the peak instantaneous value of power is 80 kW, significantly more than the

demand value.

Figure 1.8 shows another example of energy and demand. In this case, each bar

represents the energy consumed in a 15-minute interval. The energy use in each

interval typically falls between 50 and 70 kWh. However, during two intervals the

energy rises sharply and peaks at 100 kWh in interval number 7. This peak of usage

will result in setting a high demand reading. For each interval shown the demand

value would be four times the indicated energy reading. So interval 1 would have an

associated demand of 240 kWh/hr. Interval 7 will have a demand value of 400 kWh/

hr. In the data shown, this is the peak demand value and would be the number that

would set the demand charge on the utility bill.

As can be seen from this example, it is important to recognize the relationships

between power, energy and demand in order to control loads effectively or to monitor

use correctly.

Doc# E145701 1-11

Figure 1.8: Energy Use and Demand

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

1.3: Reactive Energy and Power Factor

V

I

I

R

I

X

The real power and energy measurements discussed in the previous section relate to

the quantities that are most used in electrical systems. But it is often not sufficient to

only measure real power and energy. Reactive power is a critical component of the

total power picture because almost all real-life applications have an impact on

reactive power. Reactive power and power factor concepts relate to both load and

generation applications. However, this discussion will be limited to analysis of reactive

power and power factor as they relate to loads. To simplify the discussion, generation

will not be considered.

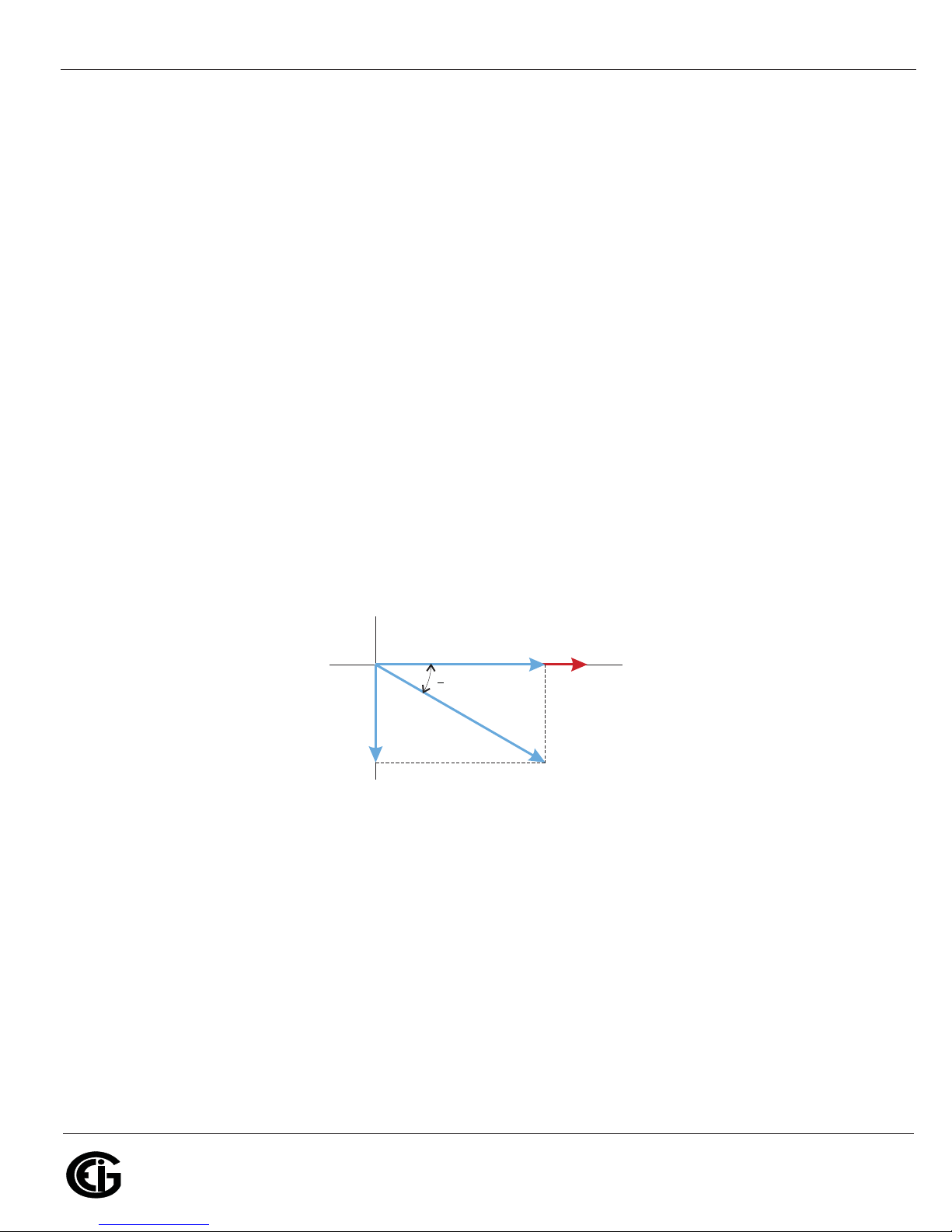

Real power (and energy) is the component of power that is the combination of the

voltage and the value of corresponding current that is directly in phase with the

voltage. However, in actual practice the total current is almost never in phase with the

voltage. Since the current is not in phase with the voltage, it is necessary to consider

1: Three-Phase Power Measurement

both the inphase component and the component that is at quadrature (angularly

rotated 90

o

or perpendicular) to the voltage. Figure 1.9 shows a single-phase voltage

and current and breaks the current into its in-phase and quadrature components.

0

Figure 1.9: Voltage and Complex Current

The voltage (V) and the total current (I) can be combined to calculate the apparent

power or VA. The voltage and the in-phase current (I

real power or watts. The voltage and the quadrature current (I

) are combined to produce the

R

) are combined to

X

calculate the reactive power.

The quadrature current may be lagging the voltage (as shown in Figure 1.9) or it may

lead the voltage. When the quadrature current lags the voltage the load is requiring

both real power (watts) and reactive power (VARs). When the quadrature current

Doc# E145701 1-12

1: Three-Phase Power Measurement

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

leads the voltage the load is requiring real power (watts) but is delivering reactive

power (VARs) back into the system; that is VARs are flowing in the opposite direction

of the real power flow.

Reactive power (VARs) is required in all power systems. Any equipment that uses

magnetization to operate requires VARs. Usually the magnitude of VARs is relatively

low compared to the real power quantities. Utilities have an interest in maintaining

VAR requirements at the customer to a low value in order to maximize the return on

plant invested to deliver energy. When lines are carrying VARs, they cannot carry as

many watts. So keeping the VAR content low allows a line to carry its full capacity of

watts. In order to encourage customers to keep VAR requirements low, some utilities

impose a penalty if the VAR content of the load rises above a specified value.

A common method of measuring reactive power requirements is power factor. Power

factor can be defined in two different ways. The more common method of calculating

power factor is the ratio of the real power to the apparent power. This relationship is

expressed in the following formula:

Total PF = real power / apparent power = watts/VA

This formula calculates a power factor quantity known as Total Power Factor. It is

called Total PF because it is based on the ratios of the power delivered. The delivered

power quantities will include the impacts of any existing harmonic content. If the

voltage or current includes high levels of harmonic distortion the power values will be

affected. By calculating power factor from the power values, the power factor will

include the impact of harmonic distortion. In many cases this is the preferred method

of calculation because the entire impact of the actual voltage and current are

included.

A second type of power factor is Displacement Power Factor. Displacement PF is based

on the angular relationship between the voltage and current. Displacement power

factor does not consider the magnitudes of voltage, current or power. It is solely

based on the phase angle differences. As a result, it does not include the impact of

Doc# E145701 1-13

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

harmonic distortion. Displacement power factor is calculated using the following

equation:

where T is the angle between the voltage and the current (see Fig. 1.9).

In applications where the voltage and current are not distorted, the Total Power Factor

will equal the Displacement Power Factor. But if harmonic distortion is present, the

two power factors will not be equal.

1.4: Harmonic Distortion

Harmonic distortion is primarily the result of high concentrations of non-linear loads.

1: Three-Phase Power Measurement

Displacement PF Tcos=

Devices such as computer power supplies, variable speed drives and fluorescent light

ballasts make current demands that do not match the sinusoidal waveform of AC

electricity. As a result, the current waveform feeding these loads is periodic but not

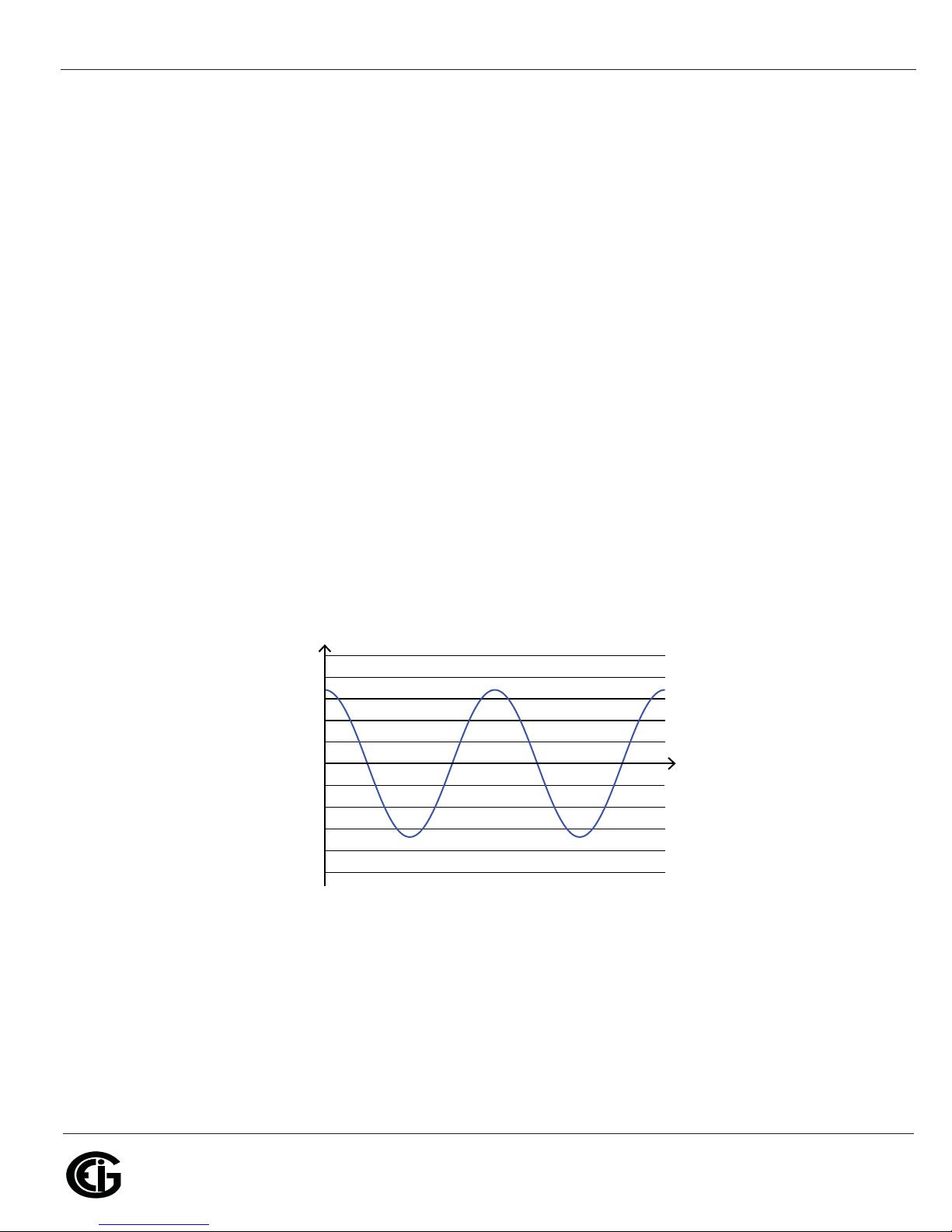

sinusoidal. Figure 1.10 shows a normal, sinusoidal current waveform. This example

has no distortion.

1000

500

0

Amps

– 500

– 1000

Figure 1.10: Nondistorted Current Waveform

Time

Figure 1.11 shows a current waveform with a slight amount of harmonic distortion.

The waveform is still periodic and is fluctuating at the normal 60 Hz frequency.

However, the waveform is not a smooth sinusoidal form as seen in Figure 1.10.

Doc# E145701 1-14

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

)spma( tnerruC

Time

Amps

3rd harmonic

5th harmonic

7th harmonic

Total

fundamental

– 500

0

500

1000

1: Three-Phase Power Measurement

1500

1000

500

0

a

–500

–1000

–1500

t

2a

Figure 1.11: Distorted Current Waveform

The distortion observed in Figure 1.11 can be modeled as the sum of several

sinusoidal waveforms of frequencies that are multiples of the fundamental 60 Hz

frequency. This modeling is performed by mathematically disassembling the distorted

waveform into a collection of higher frequency waveforms.

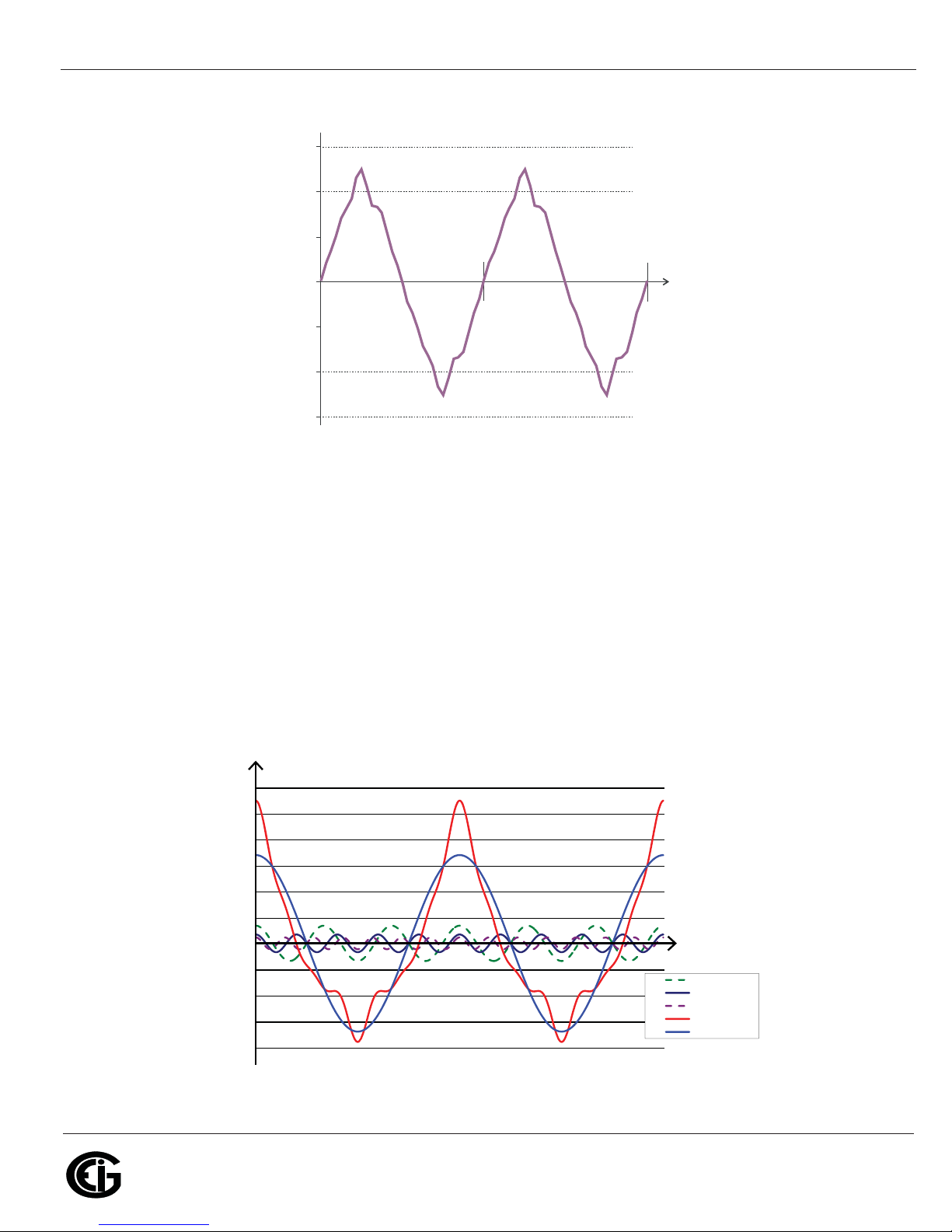

These higher frequency waveforms are referred to as harmonics. Figure 1.12 shows

the content of the harmonic frequencies that make up the distortion portion of the

waveform in Figure 1.11.

Doc# E145701 1-15

Figure 1.12: Waveforms of the Harmonics

1: Three-Phase Power Measurement

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

Electro Industries/GaugeTech

The Leader In Power Monitoring and Smart Grid Solutions

The waveforms shown in Figure 1.12 are not smoothed but do provide an indication of

the impact of combining multiple harmonic frequencies together.

When harmonics are present it is important to remember that these quantities are

operating at higher frequencies. Therefore, they do not always respond in the same

manner as 60 Hz values.

Inductive and capacitive impedance are present in all power systems. We are

accustomed to thinking about these impedances as they perform at 60 Hz. However,

these impedances are subject to frequency variation.

X

= jZL and

L

= 1/jZC

X

C

At 60 Hz, Z = 377; but at 300 Hz (5th harmonic) Z = 1,885. As frequency changes

impedance changes and system impedance characteristics that are normal at 60 Hz

may behave entirely differently in the presence of higher order harmonic waveforms.

Traditionally, the most common harmonics have been the low order, odd frequencies,

such as the 3rd, 5th, 7th, and 9th. However newer, non-

cant quantities of higher order harmonics.

signifi

linear loads are introducing

Since much voltage monitoring and almost all current monitoring is performed using

instrument transformers, the higher order harmonics are often not visible. Instrument

transformers are designed to pass 60 Hz quantities with high accuracy. These devices,

when designed for accuracy at low frequency, do not pass high frequencies with high

accuracy; at frequencies above about 1200 Hz they pass almost no information. So

when instrument transformers are used, they effectively filter out higher frequency

harmonic distortion making it impossible to see.

However, when monitors can be connected directly to the measured circuit (such as

direct connection to a 480 volt bus) the user may often see higher order harmonic

distortion. An important rule in any harmonics study is to evaluate the type of

equipment and connections before drawing a conclusion. Not being able to see har-

monic distortion is not the same as not having harmonic distortion.

It is common in advanced meters to perform a function commonly referred to as

waveform capture. Waveform capture is the ability of a meter to capture a present

picture of the voltage or current waveform for viewing and harmonic analysis.

Doc# E145701 1-16

Loading...

Loading...