Page 1

Version 9

Scripting Guide

“The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new

landscapes, but in having new eyes.”

Marcel Proust

JMP, A Business Unit of SAS

SAS Campus Drive

Cary, NC 27513

9.0.1

Page 2

The correct bibliographic citation for this manual is as follows: SAS Institute Inc. 2010. JMP® 9

Scripting Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.

®

JMP

9 Scripting Guide

Copyright © 2010, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA

ISBN 978-1-60764-598-6

All rights reserved. Produced in the United States of America.

For a hard-copy book: No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or

transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without

the prior written permission of the publisher, SAS Institute Inc.

For a Web download or e-book: Your use of this publication shall be governed by the terms established

by the vendor at the time you acquire this publication.

U.S. Government Restricted Rights Notice: Use, duplication, or disclosure of this software and related

documentation by the U.S. government is subject to the Agreement with SAS Institute and the

restrictions set forth in FAR 52.227-19, Commercial Computer Software-Restricted Rights (June 1987).

SAS Institute Inc., SAS Campus Drive, Cary, North Carolina 27513.

1st printing, September 2010

2nd printing, January 2011

®

JMP

, SAS® and all other SAS Institute Inc. product or service names are registered trademarks or

trademarks of SAS Institute Inc. in the USA and other countries. ® indicates USA registration.

Other brand and product names are registered trademarks or trademarks of their respective companies.

Page 3

Get the Most from JMP

Whether you are a first-time or a long-time user, there is always something to learn about JMP.

Visit JMP.com to find the following:

• live and recorded Webcasts about how to get started with JMP

• video demos and Webcasts of new features and advanced techniques

• schedules for seminars being held in your area

• success stories showing how others use JMP

• a blog with tips, tricks, and stories from JMP staff

• a forum to discuss JMP with other users

®

http://www.jmp.com/getstarted/

Page 4

Page 5

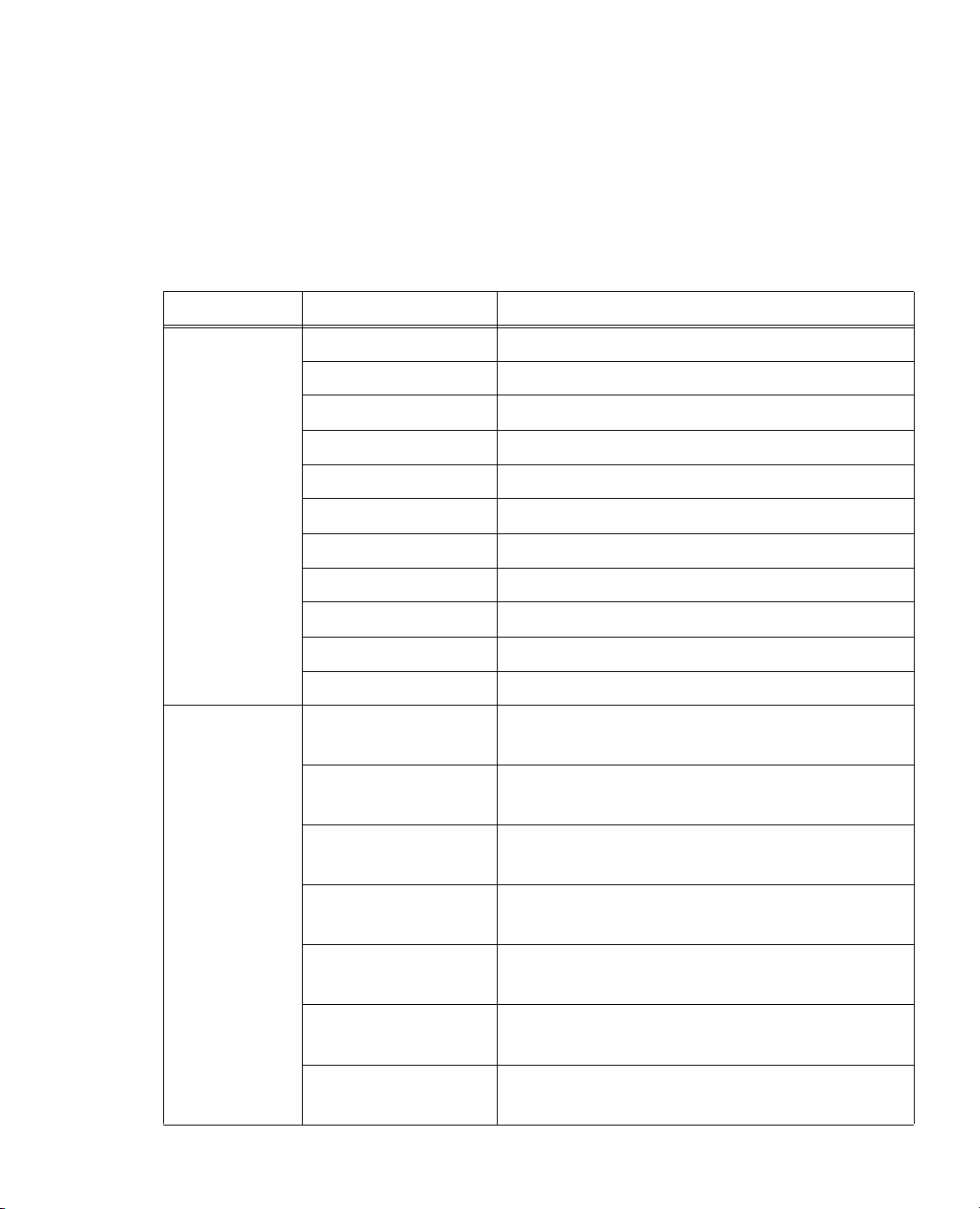

1 Introducing JSL

Tutorials and Demonstrations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Hello, World . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Modify the Script . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

Save a Script . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Save the Log . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Saving and Sharing Your Work . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Capturing Scripts for Data Tables . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Capturing Scripts for Analyses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

A General Method for Creating Scripts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Use JMP Interactively to Learn Scripting . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Using the Script Editor and Debugger . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

The Script Editor . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

The JSL Debugger (Windows Only) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Help with JSL . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

JSL Browsers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Show Commands . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Show Properties . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Table of Contents

JMP Scripting Guide

2 JSL Building Blocks

Learn the Basic Components of JSL . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

First JSL Script . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

The JSL Language . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

Lexical Rules of the Language . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

Data Elements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Operators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Context: Meaning is Local . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

Programming Versus Scripting . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

Data Table Context . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

Scoping Operators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

Page 6

vi

Name Resolution . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

Name-Binding Rules . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

Frequently-Asked Questions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

Function Resolution Rules . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

Gluing Expressions Together . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

Variables . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

Wat ch . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

Show Symbols, Clear Symbols, and Delete Symbols . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

Locking and Unlocking Symbols . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

Local . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

Datetime Operators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

Constructing Dates . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

Extracting Parts of Dates . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

Arithmetic on Dates . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

Converting Datetime Units . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

Y2K-Ready Date Handling . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

Datetime Notation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

Currency . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53

Inquiry Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53

Functions that communicate with users . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55

Writing to the log . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55

Send information to the user . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56

3 Programming Functions

Script Control . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59

Programming Example . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61

Iterating . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61

For . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61

While . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

Summation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

Product . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

Break and Continue . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

Conditional functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 64

If . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 64

Match . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65

Choose . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66

Interpolate . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66

Page 7

vii

Step . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 67

Controlling script execution . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68

Wai t . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68

Schedule . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68

JSL Data Structures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68

Lists . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68

Matrices . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72

Associative Arrays . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72

Character Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 77

Concat . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 77

Munger . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78

Repeat . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79

Sequence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 80

Comparison and Logical Operators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 81

Missing Values . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82

Missing Character Values . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83

Short-Circuiting Behavior . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83

4 Data Tables

Create, Open, and Manipulate Data Tables . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85

Data Table Basics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 87

Getting a Data Table Object . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 87

Objects and Messages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 90

Messages for Data Tables . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 95

Naming, Saving, and Printing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 95

Subscribing to a Data Table . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 95

Journal and Layout . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 96

Creating and Deleting Columns . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 97

Accessing Values . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 99

Summarize . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103

Working with Metadata . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 105

Commands from the Rows menu . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 110

Commands from the Tables Menu . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 116

Manipulating columns . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 122

Obtaining Column Names . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 122

Select Columns . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 122

Moving Columns . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 123

Page 8

viii

Data Column Objects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 123

Setting and Getting Attributes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 125

Row State Operators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 133

What are Row States? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 134

An Overview of Row State Operators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 137

Each of the Row State Operators in Detail . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 142

Optional: The Numbers Behind Row States . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 150

Calculations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 151

Pre-Evaluated Statistics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 151

Calculator Formulas . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 152

5 Scripting Platforms

Create, Repeat, and Modify Analyses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 153

Scripting Analysis Platforms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 155

Launching Platforms Interactively and Obtaining the Equivalent Script . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 155

Launch a Platform . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 156

Save Script . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 156

Make Some Changes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 157

Syntax for Platform Scripting . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 157

BY Group Reports . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 158

Saving BY Group Scripts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 160

Sending Script Commands to a Live Analysis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 160

Conventions for Commands and Arguments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 161

Sending Several Messages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 162

Learning the Messages an Object Responds to . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 162

How to Interpret the Listing from Show Properties . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 163

Launching Platforms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 164

Specifying Columns . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 164

Platform Action Command . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 164

Invisible Reports . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 165

Titles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 166

General Messages for Platform Windows . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 166

Options for All Platforms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 169

Additional Notes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .169

Spline Fits . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 169

Fit Model Effects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 170

Fit Model Send Command . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 171

Page 9

DOE Scripting . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 172

Scatterplot Scripting . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 173

6 Display Trees

Create and Use Windows . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 175

Manipulating Displays . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 177

Introduction to Display Boxes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 177

DisplayBox Object References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 180

Sending Messages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 182

Using the << Operator . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 184

Platform Example . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 185

How to Access Built-in Windows . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 189

Using the Pick Windows . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 189

Constructing Display Trees . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 190

Basics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 190

Updating an Existing Display . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 192

Controlling Text Wrap . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 194

Interactive Display Elements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 194

Send Messages to Constructed Displays . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 209

Build Your Own Displays from Scratch . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 209

Construct Display Boxes Containing Platforms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 210

Construct a Custom Platform . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 212

Sheets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 215

Journals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 217

Picture Display Type . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 217

ix

Modal Windows . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 218

Constructing Modal Windows . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 218

General-Purpose Modal Window . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 219

Data Column Dialog Boxes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 222

Constructing Dialogs and Column Dialogs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 225

Scripting the Script Editor . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 228

Syntax Reference . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 229

7 Scripting Graphs

Create and Edit 2-Dimensional Plots . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 237

Adding Scripts to Graphs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 239

Ordering Graphics Elements Using JSL . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 240

Adding a Legend to a Graph . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 240

Page 10

x

Creating New Graphs From Scratch . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 241

Making Changes to Graphs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 242

Graphing Elements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 243

Plotting Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 243

Getting the Properties of a Graphics Frame . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 249

Adding a Legend . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 249

Drawing Lines, Arrows, Points, and Shapes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 249

Lines . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 249

Arrows . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 251

Markers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 252

Pies and Arcs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .254

Regular Shapes: Circles, Rectangles, and Ovals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 255

Irregular Shapes: Polygons and Contours . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 258

Adding text . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 260

Colors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 261

Transparency . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .263

Fill patterns . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 264

Line types . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 264

Drawing With Pixels . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 265

Interactive graphs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 266

Handle . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 266

MouseTrap . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 269

Drag Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 270

Troubleshooting . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 272

8 Three-Dimensional Scenes

Scripting in Three Dimensions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 273

About JSL 3-D Scenes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 275

JSL 3-D Scene Boxes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 275

Setting the Viewing Space . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 278

Setting Up a Perspective Scene . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 279

Setting up an Orthographic Scene . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 280

Changing the View . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 281

The Translate Command . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 281

The Rotate Command . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 281

The Look At Command . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 283

The ArcBall . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 284

Page 11

Graphics Primitives . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 285

Primitives Example . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 287

Controlling the Appearance of Primitives . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 288

Other uses of Begin and End . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 294

Drawing Spheres, Cylinders, and Disks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 294

Construction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 294

Lighting . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 295

Drawing Text . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 295

Using Text with Rotate and Translate . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 296

Using the Matrix Stack . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 297

Lighting and Normals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 300

Creating Light Sources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 300

Lighting Models . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 302

Normal Vectors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 302

Shading Model . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 303

Material Properties . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 304

Alpha Blending . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 304

Fog . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 305

Example . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 305

xi

Bézier Curves . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 306

One-Dimensional Evaluators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 306

Two-Dimensional Evaluators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 309

Using the mouse . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 309

Parameters . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 311

9 Matrices

Matrix Algebra in JMP . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 313

Basics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 315

Definitions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 315

Constructing Matrices . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 315

Numeric Operators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 317

Manipulating Values . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 319

Subscripts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 321

Matrix Operators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 324

Solving Linear Systems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 325

Additional Construction Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 327

Decompositions and Normalizations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 329

Page 12

xii

Build Your Own Matrix Operators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 333

Matrices With the Rest of JMP . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 334

Matrices and Data Tables . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 334

Matrices and Reports . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 335

Statistical Examples . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 335

Regression Example . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 335

ANOVA Example . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 336

10 Extending JMP

Add-Ins, External Data Sources and Analytical Tools, and Automation . . . . . . . . . . . . 341

Real-Time Data Capture . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 343

Create a Datafeed Object . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 343

Manage a Datafeed with Messages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 344

Examples of Datafeed . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 346

Dynamic Link Libraries (DLLs) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 349

Using Sockets in JSL . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 351

Socket-Related Commands . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 352

Messages for Sockets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 352

Database Access (Windows Only) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 354

Working with SAS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 355

Make a SAS DATA Step . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 355

SAS Variable Names . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 356

Connect to a SAS Metadata Server . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 356

Preferences . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 358

Sample Scripts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 358

Working with R . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 359

Installing R . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 360

JMP to R Interfaces . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 361

R JSL Scriptable Object Interfaces . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 361

Conversion Between JMP Data Types and R Data Types . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 361

Troubleshooting . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 363

Examples . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 364

Working with Excel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 366

JMP Add-Ins . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 366

Workflow for Creating an Add-In . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 367

More About Installation and Registration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 369

Page 13

Addin.def File Specification . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 371

Example JMP Add-In . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 372

OLE Automation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 373

Automating JMP through Visual Basic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 373

Automating JMP through Visual C++ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 381

11 Advanced Concepts

Complex Scripting Techniques And Additional Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 385

Advanced Programming Concepts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 387

Throwing and Catching Exceptions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 387

Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 388

Recursion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 389

Includes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 390

Loading and Saving Text Files . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 390

Advanced Scoping and Namespaces . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 390

Names Default To Here . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 390

Scoped Names . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 393

Namespaces . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 396

Referencing Namespaces and Scopes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 401

Resolving Named Variable References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 403

Best Practices for Advanced Scripting . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 405

xiii

Scripting BY Groups . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 405

Lists and Expressions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 406

Stored expressions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 406

Macros . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 414

Manipulating lists . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 414

Manipulating expressions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 416

Encryption . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 420

Encryption and Global Variables . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 421

Encrypting Scripts in Data Tables . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 421

XML Parsing Operations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 422

Example . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 422

Pattern Matching and Regular Expressions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 424

Patterns and Case . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 426

Regular Expressions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 427

Projects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 427

Page 14

xiv

Hexadecimal and BLOB Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 430

Web . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 432

Scheduling Actions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 433

Additional Numeric Operators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 434

Derivatives . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 434

Algebraic Manipulations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 436

Maximize and Minimize . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 437

A JSL Syntax Reference

Summary of Operators, Functions, And Messages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 439

Arithmetic Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 441

Assignment Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 443

Character Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 447

Character Pattern Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 458

Comments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 466

Comparison Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 467

Conditional and Logical Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 472

Constants . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 477

Date and Time Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 477

Discrete Probability Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 483

Display . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 486

Financial Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 497

Graphic Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 502

Matrix Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .514

Numeric Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 528

Probability Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 529

R Integration Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 541

Random Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 546

Row Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 550

Row State Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 551

SAS Integration Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 554

Statistical Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 568

Transcendental Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 572

Page 15

Trigonometric Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 575

Utility Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 578

Platform Scripting Notes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 623

Scripting Options for All Platforms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 623

Individual Platform Options . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 623

Index

Syntax Reference . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 629

BMessages

Summary of Object Messages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 639

Associative Arrays . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 641

Data Tables . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 642

Columns . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 653

Rows . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 657

Data Filter . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 658

Databases . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 660

Datafeed . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 660

xv

Display Boxes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 661

Windows . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 661

All Display Boxes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 663

Outline Boxes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 667

Frame Boxes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 667

Table Boxes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 668

Tab Boxes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 669

Tex t B oxe s . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 669

Axis Boxes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 670

Number Col Boxes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 672

Slider Boxes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 673

String Col Boxes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 673

Matrix Boxes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .674

Nom Axis Boxes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 674

Panel Boxes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 674

Border Boxes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .674

Dynamic Link Libraries (DLLs) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 675

Platforms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 676

R Integration Messages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 679

Page 16

xvi

SAS Integration Messages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 683

Metadata Server Objects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 683

SAS Server Objects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 684

Stored Processes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 692

SAS Results . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 697

Messages for Schedule . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 699

Sockets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 700

Other Objects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 703

Zip Archives . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 703

Journals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 704

C Compatibility Notes

Changes in Scripting from JMP 8 to JMP 9 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 705

DGlossary

Terms, Concepts, and Placeholders . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 709

Index

Scripting Guide . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 713

Page 17

Credits and Acknowledgments

Origin

JMP was developed by SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC. JMP is not a part of the SAS System, though portions

of JMP were adapted from routines in the SAS System, particularly for linear algebra and probability

calculations. Version 1 of JMP went into production in October 1989.

Credits

JMP was conceived and started by John Sall. Design and development were done by John Sall, Chung-Wei

Ng, Michael Hecht, Richard Potter, Brian Corcoran, Annie Dudley Zangi, Bradley Jones, Craige Hales,

Chris Gotwalt, Paul Nelson, Xan Gregg, Jianfeng Ding, Eric Hill, John Schroedl, Laura Lancaster, Scott

McQuiggan, Melinda Thielbar, Clay Barker, Peng Liu, Dave Barbour, Jeff Polzin, John Ponte, and Steve

Amerige.

In the SAS Institute Technical Support division, Duane Hayes, Wendy Murphrey, Rosemary Lucas, Win

LeDinh, Bobby Riggs, Glen Grimme, Sue Walsh, Mike Stockstill, Kathleen Kiernan, and Liz Edwards

provide technical support.

Nicole Jones, Kyoko Keener, Hui Di, Joseph Morgan, Wenjun Bao, Fang Chen, Susan Shao, Michael

Crotty, Jong-Seok Lee, Tonya Mauldin, Audrey Ventura, Ani Eloyan, Bo Meng, and Sequola McNeill

provide ongoing quality assurance. Additional testing and technical support are provided by Noriki Inoue,

Kyoko Takenaka, Yusuke Ono, Masakazu Okada, and Naohiro Masukawa from SAS Japan.

Bob Hickey and Jim Borek are the release engineers.

The JMP books were written by Ann Lehman, Lee Creighton, John Sall, Bradley Jones, Erin Vang, Melanie

Drake, Meredith Blackwelder, Diane Perhac, Jonathan Gatlin, Susan Conaghan, and Sheila Loring, with

contributions from Annie Dudley Zangi and Brian Corcoran. Creative services and production was done by

SAS Publications. Melanie Drake implemented the Help system.

Jon Weisz and Jeff Perkinson provided project management. Also thanks to Lou Valente, Ian Cox, Mark

Bailey, and Malcolm Moore for technical advice.

Thanks also to Georges Guirguis, Warren Sarle, Gordon Johnston, Duane Hayes, Russell Wolfinger,

Randall Tobias, Robert N. Rodriguez, Ying So, Warren Kuhfeld, George MacKensie, Bob Lucas, Warren

Kuhfeld, Mike Leonard, and Padraic Neville for statistical R&D support. Thanks are also due to Doug

Melzer, Bryan Wolfe, Vincent DelGobbo, Biff Beers, Russell Gonsalves, Mitchel Soltys, Dave Mackie, and

Stephanie Smith, who helped us get started with SAS Foundation Services from JMP.

Acknowledgments

We owe special gratitude to the people that encouraged us to start JMP, to the alpha and beta testers of JMP,

and to the reviewers of the documentation. In particular we thank Michael Benson, Howard Yetter (d),

Page 18

xviii

Andy Mauromoustakos, Al Best, Stan Young, Robert Muenchen, Lenore Herzenberg, Ramon Leon, Tom

Lange, Homer Hegedus, Skip Weed, Michael Emptage, Pat Spagan, Paul Wenz, Mike Bowen, Lori Gates,

Georgia Morgan, David Tanaka, Zoe Jewell, Sky Alibhai, David Coleman, Linda Blazek, Michael Friendly,

Joe Hockman, Frank Shen, J.H. Goodman, David Iklé, Barry Hembree, Dan Obermiller, Jeff Sweeney,

Lynn Vanatta, and Kris Ghosh.

Also, we thank Dick DeVeaux, Gray McQuarrie, Robert Stine, George Fraction, Avigdor Cahaner, José

Ramirez, Gudmunder Axelsson, Al Fulmer, Cary Tuckfield, Ron Thisted, Nancy McDermott, Veronica

Czitrom, Tom Johnson, Cy Wegman, Paul Dwyer, DaRon Huffaker, Kevin Norwood, Mike Thompson,

Jack Reese, Francois Mainville, and John Wass.

We also thank the following individuals for expert advice in their statistical specialties: R. Hocking and P.

Spector for advice on effective hypotheses; Robert Mee for screening design generators; Roselinde Kessels

for advice on choice experiments; Greg Piepel, Peter Goos, J. Stuart Hunter, Dennis Lin, Doug

Montgomery, and Chris Nachtsheim for advice on design of experiments; Jason Hsu for advice on multiple

comparisons methods (not all of which we were able to incorporate in JMP); Ralph O’Brien for advice on

homogeneity of variance tests; Ralph O’Brien and S. Paul Wright for advice on statistical power; Keith

Muller for advice in multivariate methods, Harry Martz, Wayne Nelson, Ramon Leon, Dave Trindade, Paul

Tobias, and William Q. Meeker for advice on reliability plots; Lijian Yang and J.S. Marron for bivariate

smoothing design; George Milliken and Yurii Bulavski for development of mixed models; Will Potts and

Cathy Maahs-Fladung for data mining; Clay Thompson for advice on contour plotting algorithms; and

Tom Little, Damon Stoddard, Blanton Godfrey, Tim Clapp, and Joe Ficalora for advice in the area of Six

Sigma; and Josef Schmee and Alan Bowman for advice on simulation and tolerance design.

For sample data, thanks to Patrice Strahle for Pareto examples, the Texas air control board for the pollution

data, and David Coleman for the pollen (eureka) data.

Translations

Trish O'Grady coordinates localization. Special thanks to Noriki Inoue, Kyoko Takenaka, Masakazu Okada,

Naohiro Masukawa, and Yusuke Ono (SAS Japan); and Professor Toshiro Haga (retired, Tokyo University

of Science) and Professor Hirohiko Asano (Tokyo Metropolitan University) for reviewing our Japanese

translation; François Bergeret for reviewing the French translation; Bertram Schäfer and David Meintrup

(consultants, StatCon) for reviewing the German translation; Patrizia Omodei, Maria Scaccabarozzi, and

Letizia Bazzani (SAS Italy) for reviewing the Italian translation; RuiQi Qiao, Rula Li, and Molly Li for

reviewing Simplified Chinese translation (SAS R&D Beijing); Finally, thanks to all the members of our

outstanding translation and engineering teams.

Past Support

Many people were important in the evolution of JMP. Special thanks to David DeLong, Mary Cole, Kristin

Nauta, Aaron Walker, Ike Walker, Eric Gjertsen, Dave Tilley, Ruth Lee, Annette Sanders, Tim Christensen,

Eric Wasserman, Charles Soper, Wenjie Bao, and Junji Kishimoto. Thanks to SAS Institute quality

assurance by Jeanne Martin, Fouad Younan, and Frank Lassiter. Additional testing for Versions 3 and 4 was

done by Li Yang, Brenda Sun, Katrina Hauser, and Andrea Ritter.

Also thanks to Jenny Kendall, John Hansen, Eddie Routten, David Schlotzhauer, and James Mulherin.

Thanks to Steve Shack, Greg Weier, and Maura Stokes for testing JMP Version 1.

Page 19

Thanks for support from Charles Shipp, Harold Gugel (d), Jim Winters, Matthew Lay, Tim Rey, Rubin

Gabriel, Brian Ruff, William Lisowski, David Morganstein, Tom Esposito, Susan West, Chris Fehily, Dan

Chilko, Jim Shook, Ken Bodner, Rick Blahunka, Dana C. Aultman, and William Fehlner.

Technology License Notices

xix

Scintilla is Copyright 1998-2003 by Neil Hodgson <neilh@scintilla.org>.

WARRANTIES WITH REGARD TO THIS SOFTWARE, INCLUDING ALL IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF

MERCHANTABILITY AND FITNESS, IN NO EVENT SHALL NEIL HODGSON BE LIABLE FOR ANY SPECIAL,

INDIRECT OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES OR ANY DAMAGES WHATSOEVER RESULTING FROM LOSS OF

USE, DATA OR PROFITS, WHETHER IN AN ACTION OF CONTRACT, NEGLIGENCE OR OTHER TORTIOUS

ACTION, ARISING OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE USE OR PERFORMANCE OF THIS SOFTWARE.

XRender is Copyright © 2002 Keith Packard.

TO THIS SOFTWARE, INCLUDING ALL IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY AND FITNESS, IN NO

EVENT SHALL KEITH PACKARD BE LIABLE FOR ANY SPECIAL, INDIRECT OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES OR

ANY DAMAGES WHATSOEVER RESULTING FROM LOSS OF USE, DATA OR PROFITS, WHETHER IN AN ACTION

OF CONTRACT, NEGLIGENCE OR OTHER TORTIOUS ACTION, ARISING OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH

THE USE OR PERFORMANCE OF THIS SOFTWARE.

KEITH PACKARD DISCLAIMS ALL WARRANTIES WITH REGARD

NEIL HODGSON DISCLAIMS ALL

ImageMagick software is Copyright © 1999-2010 ImageMagick Studio LLC, a non-profit organization

dedicated to making software imaging solutions freely available.

bzlib software is Copyright © 1991-2009, Thomas G. Lane, Guido Vollbeding. All Rights Reserved.

FreeType software is Copyright © 1996-2002 The FreeType Project (www.freetype.org). All rights reserved.

Page 20

xx

Page 21

Chapter 1

Introducing JSL

Tutorials and Demonstrations

This introduction shows you the basics of JMP Scripting Language (JSL). The chapter starts with a simple,

progressive tutorial example to show you where to type a script, how to submit it, and how to modify and

save it. The purpose of this tutorial is to give you the basic techniques for working with any script, whether

it’s one you write or one you get from someone else. Next is a showcase of examples to demonstrate how

scripting might be useful in a variety of settings. For example, classroom simulations, advanced data

manipulations, custom statistics, production lines, and so forth.

Confusion alert! Throughout this book, special shaded “confusion alerts” like this one

call your attention to important concepts that could be unfamiliar or more

complicated than you might expect, or where JMP might be a little different from

other applications. These alerts appear whenever a particularly good example of a

potential problem arises in the text, and although you will find them under topics that

might not apply to your immediate needs, the ideas presented are always general and

important. Please be sure to take a look even when you are skipping pages and looking

for something else.

You can quickly locate these pointers by looking up “confusion alert” in the “Index,”

p. 713.

Page 22

Contents

Hello, World . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Modify the Script . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

Save a Script . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Save the Log . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Saving and Sharing Your Work . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

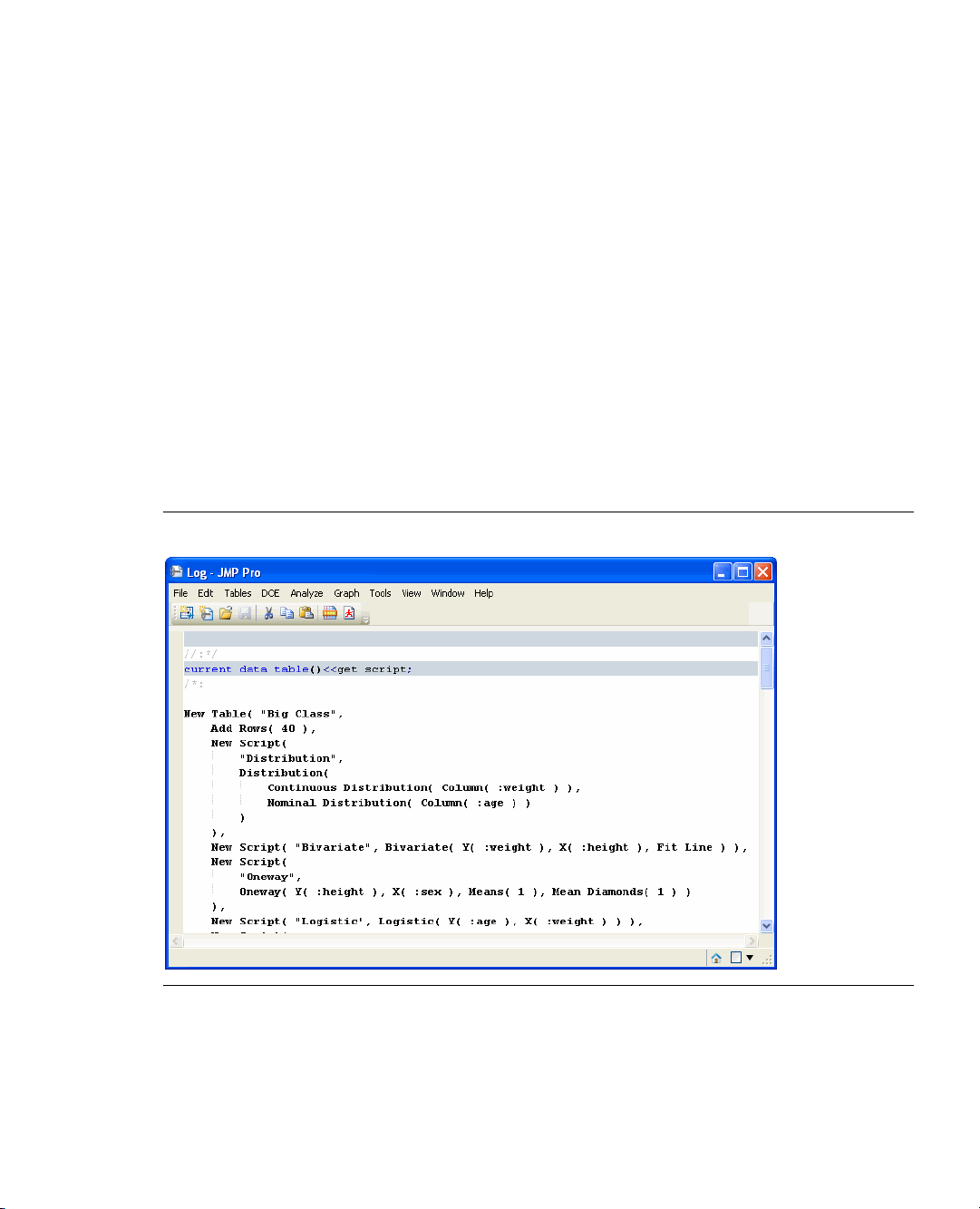

Capturing Scripts for Data Tables . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Capturing Scripts for Analyses. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

A General Method for Creating Scripts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Use JMP Interactively to Learn Scripting. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Using the Script Editor and Debugger. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12

The Script Editor . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12

The JSL Debugger (Windows Only) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Help with JSL . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

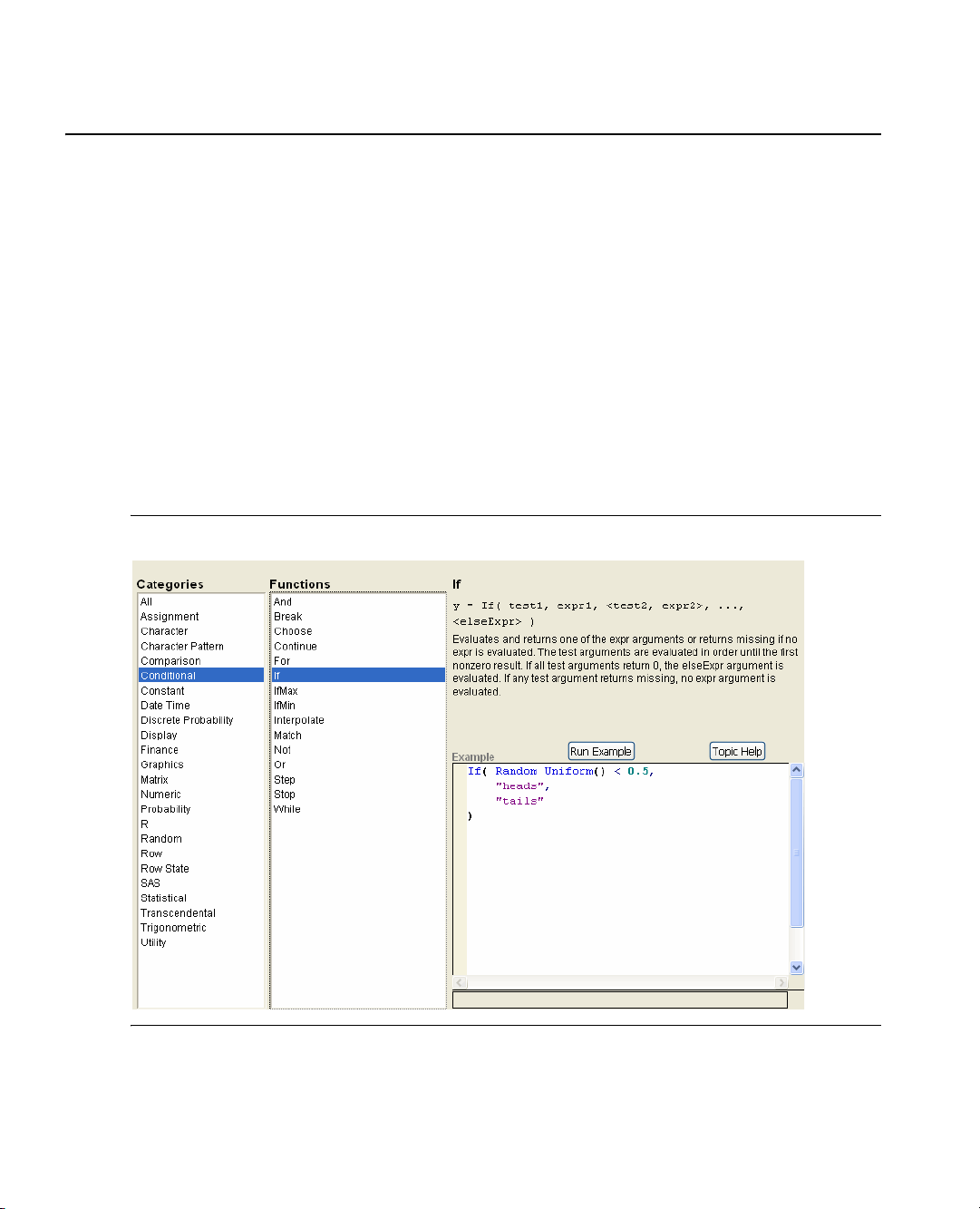

JSL Browsers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Show Commands . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .21

Show Properties. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Page 23

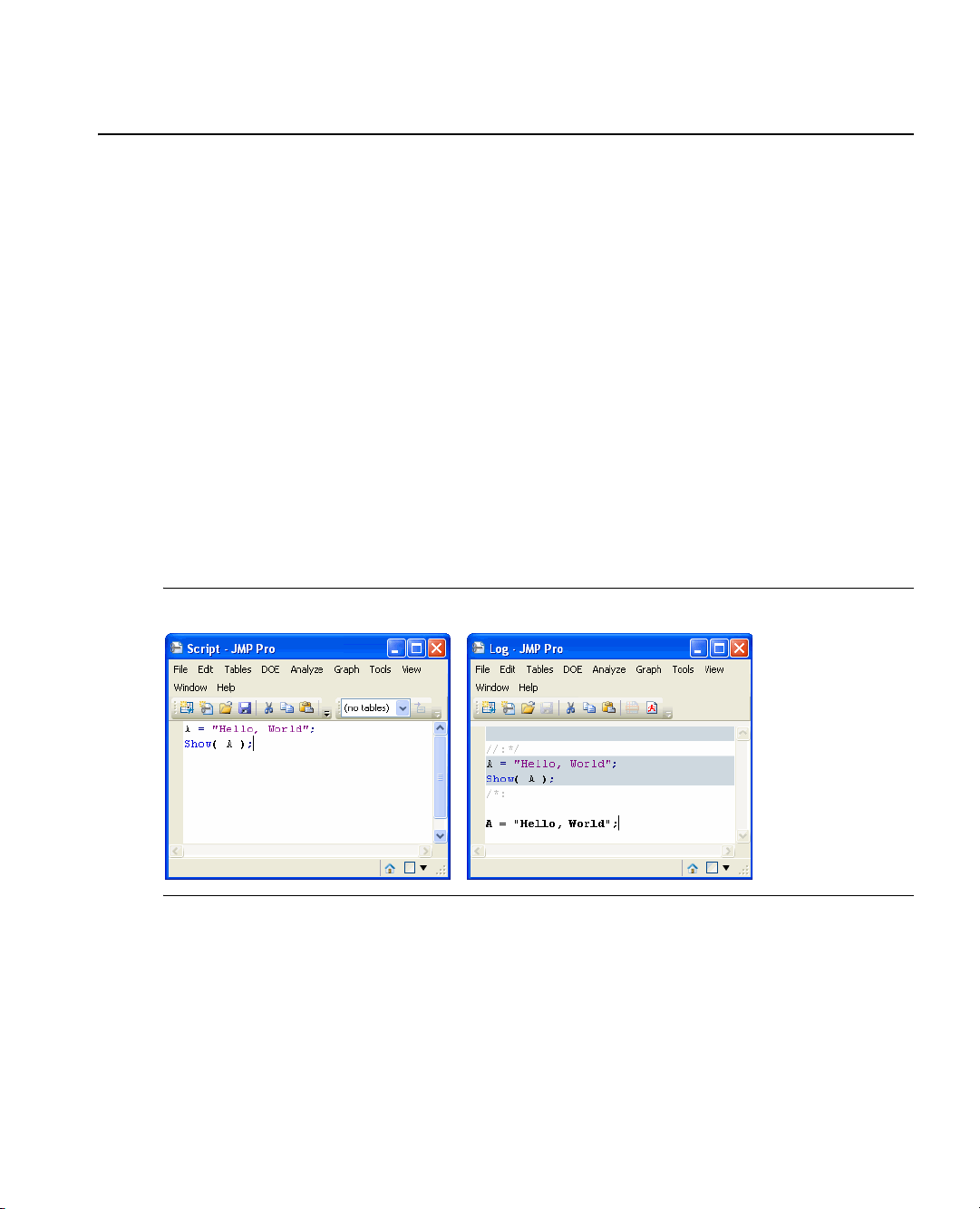

Chapter 1 Introducing JSL 3

Hello, World

Hello, World

This exercise is simple and hearkens back to a classic. Perhaps you recognize it.

1. Start JMP.

2. If the log window is not open, open it by selecting

Macintosh.

3. In the JMP Starter window, click

New Script.

New scripts can also be created from the menus. On Windows, select

Macintosh, select

File>New>NewScript.

4. In the resulting script editor, type these lines:

A = "Hello, World";

Show( A );

5. From the Edit menu, select Run Script.

The keyboard shortcut is to press CTRL-R on Windows or COMMAND-R on Macintosh.

The result is shown in the Log window. Besides showing results and errors, this window is also a script

editor.

View > Log on Windows or Window > Log on

File > New > Script. On

Figure 1.1 The Script Window (left) and the Log Window (right)

This is how you enter and submit JSL. You have just created a global variable named A, assigned a value to

it, and shown its value. Notice that the log echoes your script first, and then echoes any results. In this case,

the result is the output for the

Show(A) command.

Go To Line

As your scripts grow in size, it is handy to jump to specific lines in the script. Use the

from the

Edit menu to jump to a specific line.

Go To Line command

Page 24

4 Introducing JSL Chapter 1

Hello, World

This command is also useful during the debugging process, since error messages frequently mention the line

of the script where the error occurred.

Show Line Numbers

The script window does not show line numbers by default. To see the line numbers, right-click anywhere in

the script window, and then select

Show Line Numbers.

Modify the Script

Now try making this script do a little more work by adding a For-loop to greet the world not just once, but

four times. Also, use

For-loop works.

1. In the script window, change the script to this:

For( i = 1, i < 5, i++,

X = i;

A = "Hello, World";

Print( X, A );

);

Print( "done" );

2. Submit the script as before.

(To submit part of the text in a window instead of all text, select the text first and then press Control-R

on Windows or a-R on Macintosh)

Print this time instead of Show, and make a few other changes to see how the

Output

1

"Hello, World"

2

"Hello, World"

3

"Hello, World"

4

"Hello, World"

"done"

Print

is similar to Show except that it does not label the results with the variable name. It just prints the

value.

Stopping a Script

When you run a script, the

is running, you can select this option to stop it. You can also press ESC on Windows or

COMAND-PERIOD on Macintosh . Many scripts execute more quickly than you can stop them.

Run Script command in the Edit menu changes to Stop Script. While a script

Page 25

Chapter 1 Introducing JSL 5

Hello, World

Punctuation and Spaces

Notice the indented lines inside the

For-loop. This is not necessary for JMP’s sake; it just makes it a little

easier to read. You could write this script like this if you want:

fo R(i=

1,i<5,i++

,X=i;A="Hello, World";P r i N T( X,A));print("done");

Words in JMP’s scripting language are separated by parentheses, commas, semicolons, and various operators

such as +, –, and so on. As far as JMP is concerned, spaces, tabs, returns, and blank lines inside or between

operators or within JSL words do not exist. This is because most JSL words come from JMP’s usual

graphical user interface (GUI), and most of those commands have spaces in them. For example, you will see

later on that to do Fit Model, the JSL would be

parentheses)

. Most people would rather see “Fit Model” than “fitmodel.”

Fit Model(and some arguments inside

JSL is not case-sensitive, so you do not have to worry about reaching for the Shift key all the time.

You do have to be a little careful inside a text string. In “Hello, World” extra spaces would affect the output,

because text strings inside double quotation marks are taken literally, exactly as you type them. Also, you

would get errors if you put spaces between the two plus signs in

same as

43).

i++, (i+ +), or in numbers (43 is not the

Generally, JSL uses:

commas , between arguments inside the parentheses for a command.

parentheses ( ) to surround all the arguments of a command. Many JSL words have parentheses after

them even if they do not take arguments; for example

the number 3.14...

do give it. Therefore,

Pi does not expect an argument and will complain about any argument that you

Pi(mincemeat) would be considered an error (although it seems heretical to

pi() has the parentheses even though π is just

say so). But the parentheses are still required.

semicolons ; to separate commands but also to glue them together. In other words, you use a

semicolon to separate one complete message from the next. For example,

semicolon really does is tell JMP to continue and do more things. For example, the

a=1;b=2. What the

For-loop

example showed how to put several statements in the place of one statement for the fourth

argument, because the semicolon effectively turned all three statements into one argument.

Trailing semicolons (extras at the end of a script or at the end of a list of arguments) are harmless, so

you can also think of semicolons as terminating characters. In fact, terminating each complete JSL

statement with a semicolon is a good habit to adopt.

quotation marks " " to enclose text strings. Anything inside quotation marks is taken literally,

exactly as is, including spaces and upper- or lower-case. Nothing that could be evaluated is evaluated.

If you have

pi()^2 inside quotation marks, it is just a sequence of six characters, not a value close to

ten. See “Quoted Strings,” p. 28, for ways to include special characters and quotation marks in

strings.

For a more formal discussion of punctuation rules, see “Lexical Rules of the Language,” p. 26.

Page 26

6 Introducing JSL Chapter 1

Saving and Sharing Your Work

Save a Script

To save your script, just follow these instructions:

1. Make the script window active (click the “Untitled” window to make it the front-most window).

2. From the

3. Specify a filename, including the extension

4. Click

Scripts are saved as text files, and you can edit them with any text editor. However, if you do edit scripts

with applications other than JMP, be careful to save them as plain text files. If you preserve the

you can double-click a script file to launch JMP.

File menu, select Save or Save As.

.jsl. For example, hello.jsl.

Save.

.jsl extension,

To reuse a script, use

Open from JMP’s File menu, double-click a .jsl file, or drag and drop the file onto

JMP’s application icon.

When opening a JSL file, the actual script is always opened in its own script window. However, it might be

distracting to some users to see this window. To keep a script from opening in a script window, put this

command on the first line of the script.

//!

If it is not on the very first line by itself, this command does nothing.

You can over-ride this comment when opening the file. Select

select the JSL file and click

Open. The script opens into a script window instead of being executed.

Save the Log