Page 1

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 1 of 33

Page 2

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

Preface

Introduction

New Zealand has a trade agreement with Australia, which requires that products

lawful for sale in Australia, originating from or through Australia, may be lawfully sold

in New Zealand and vice versa. New Zealand is therefore obliged to consider

implementing any action taken by Australia affecting the appliance and equipment

market.

The Australian Greenhouse Office (AGO) is committed to implement minimum

energy performance standards (MEPS) for televisions (TVs) with voluntary energy

labelling. Presently the intention is for MEPS and voluntary energy labelling to be

introduced in October 2006.

The report

The report provides a New Zealand perspective on Australian proposals to introduce

a MEPS and energy labelling scheme. It recommends that a MEPS and energy

labelling scheme for TVs should be implemented in tandem with Australia. The

MEPS would cover both on-mode and standby energy consum ption. The setting of

MEPS levels would be designed initially, as in Australia to enco urage the removal of

the 30% of worst performing TVs from the marketplace and to match the best

practice levels of our product source countries.

The total energy use of TVs is estimated to be 320 GWh per year. Savings of 20% of

this 320 GWh over the next 5-7 years are expected to be achievable using some

form of MEPS. Standby power is also a significant contributor to the overall TV

power use, and a reduction of some 30% could be achieved, with a long term goal of

reducing TV standby consumption from around 6W to less than 1W.

EECA’s intended course of action

EECA will release this scoping report and commission a regulatory impact stateme nt.

We will then consult with industry and other interested parties. After cons ideration of

industry feedback, a recommendation will be forwarded to Government regarding the

possible adoption of MEPS and voluntary labelling.

Page 2

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 3

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

Minimum Energy

Performance Standards −

Televisions

a study for the

Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority

April 2005

produced by

Wise Analysis Ltd

P O Box 10-186

Wellington 6036

New Zealand

Disclaimer

While every attempt has been made to ensure the accuracy of the material in this report, the authors make no warranty as to the

accuracy, completeness or usefulness for any particular purpose of the material in this report; and they accept no liability for

errors of fact or opinion in this report, whether or not due to negligence on the part of any party.

Page 0

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 4

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

Minimum Energy Performance Standards −

Televisions

CONTENTS

Executive Summary

1 Introduction

1.1 Background

2 Product Description

2.1 General

2.2 Transmission Types

2.3 Television Types

2.4 Sources of Product

3 Market Profile

3.1 All Television Types

3.2 Wide-screen Televisions

Summary

4 Energy Consumption

4.1 Household Energy Consumption

4.2 Trends in TV Power consumption

Summary

5 Technology Scope for Energy Efficiency

6 Standards Development

7 Test Laboratory Capability

8 International Energy Efficiency Programs

8.1 Voluntary Programs

8.2 Mandatory Programs

Summary − Testing Standards and Energy Efficiency Programs

9 Economic Implications

9.1 Energy Cost Savings

9.2 Trans-Tasman Trade Agreement

9.3 Greenhouse Reduction Potential

10 Policy and Program Approaches to Improve Energy Efficiency

10.1 Information Programs

10.2 Labelling Programs

10.3 MEPS

10.4 Costs of MEPS

Summary - Policy and Program Approaches to Improve Energy Efficiency

Page 1

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 5

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

11 Recommended Policy Options for New Zealand

11.1 General Policy Recommendations

11.2 MEPS

11.3 Labelling Scheme

11.4 Consultation

Summary

12 Implementation Program

13 Summary and Conclusions

References

Appendix A − Potential Stakeholders

List of Tables

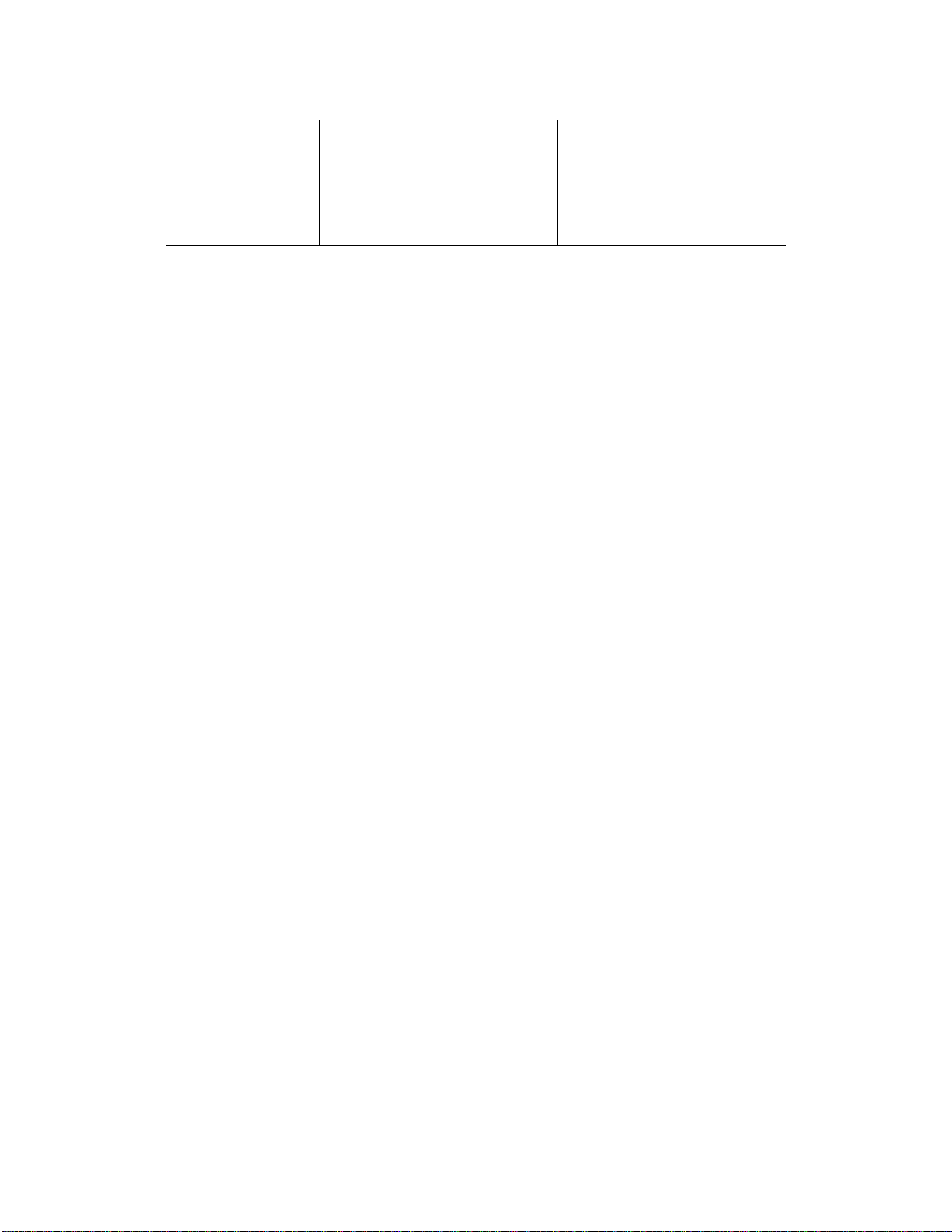

Table 1: General comparison between New Zealand and Australia

Table 2: Estimated number of TVs in households for the year ended June 2004

Table 3: Penetration of Television Ownership – Australia & New Zealand

Table 4A: New Zealand annual TV market based on type

Table 4B: New Zealand annual TV market based on feature

Table 5: Energy usage against TV penetration

Table 6: Best practice for LCD TVs

Table 7: Average Set Top Box Power Levels

Table 8: Summary of Testing Standards and Energy Efficiency Programs

Table 9: Summary of program approaches/policy tools

Table 10: Proposed Implementation Plan for Recommendations

Note: Acknowledgement is made to NAEEEP document “Minimum Energy Perform anc e Standa rds” Rep ort No

2004/11 for use of Tables 8, 9 and 10.

List of Figures

Figure 1 − Chart of Television Set Numbers in New Zealand.

Figure 2 − Power Usage Figures for Televisions in New Zealand − BAU and MEPS.

Figure 3 − Savings in CO

Emissions − BAU and MEPS.

2

Page 2

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 6

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

GLOSSARY

AGO Australian Greenhouse Office

ANZ Australian and New Zealand

AS Australian Standard

AS/NZS Joint Australian and New Zealand standard

BAU Business as Usual

BRANZ Building Research Association of New Zealand

-e Carbon dioxide equivalent

CO

2

Comparative label A type of product label that indicates not only that the product meets specific

energy or environmental criteria, but allows comparison between products by

ranking.

CRT Cathode Ray Tube

DVD Digital Video Disk

DVB Digital Video Broadcasting

EECA Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority

Endorsement label A type of product label that indicates a product meets specific criteria (i.e.

energy or environmental). The label does not allow comparison between

eligible products.

EER Energy Efficiency Ratio

EEI Energy Efficiency Index, a measure which indicates the efficiency of TVs in

both the On and Standby mode.

GEEA Group for Energy Efficient Appliances (Europe)

HDTV High-definition television

HEEP Household Energy End-use Project (BRANZ/EECA)

IRD Integrated receiver decoder

LCD Liquid Crystal Display

MCE Ministerial Council on Energy (Australia)

MEPS Minimum Energy Performance Standards

NAEEEP National Appliance and Equipment Energy Program (Australia)

NAEEEC National Appliance and Equipment Energy Efficiency Committee (Australia)

NFEE National Framework for Energy Efficiency (Australia)

NPV Net present value

Ownership The ratio of stock to the total number of households.

Penetration The proportion of households in which a particular appliance type is present

(irrespective of the number of units of that appliance in the household).

Saturation The number of specified appliances per household, for those households that

have the appliance.

SDTV Standard-definition television

Statistics NZ Statistics New Zealand

STB Set top box

TTMRA Trans-Tasman Mutual Recognition Agreement

TV Television

VCR Video cassette recorder

Page 3

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 7

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

Executive Summary

This report provides a New Zealand perspective on Australian proposals to introduce a MEPS

and comparative labelling scheme. It recommends that a MEPS and comparative labelling

scheme for televisions in New Zealand should be implemented in tandem with Australia. The

MEPS should cover both on-mode and standby energy consumption. The setting of MEPS

levels should be designed initially, as in Australia to encourage the removal of the 30% of

worst performing TVs from the marketplace, and to match the best practice levels of our

product source countries.

Since the scheme will probably now be voluntary, consultation with the importers and major

retailers will be necessary to ensure that there is no undue resistance to the scheme, to

maximise compliance and adherence to the principles of the scheme.

The most common form of television used in the residential sector in both New Zealand and

Australia is still the analogue colour TV using cathode ray tube technology. However the sales

volume of slimline televisions (LCD, plasma and rear projection) is increasing rapidly almost

doubling from 5.2 to 9.6% last year. The features offered by TVs now include 100 Hz picture

frequency, widescreen format, and stereo which all increase the power of the set. Another

significant change will be the introduction of digital television. Consumers with analogue sets

will have to purchase a set top box to convert digital broadcasts to analogue, although i

receiver decoder sets will come to market soon

.

ntegrated

New Zealand imports all of its TVs, and has done so since 1990-91, and Australia is also now

primarily an importer of televisions. The main source for New Zealand supply is China, with a

smaller number originating in Europe, Japan, and Korea.

The total number of TVs in New Zealand is estimated at 2,785,600, a 98% penetration. Of

these 590,200 are single TV households. The numbers of TVs currently sold each year is

currently 318,847 an increase of 25% on the previous year. The current economic life of

standard CRT style TVs is assessed as averaging 7 years.

The total energy use of TVs is estimated to be 320 GWh per year, which is of the order of 40%

of the annual energy increase for New Zealand of 800 GWh. Savings of 20% of this 320 GWh

over the next 5-7 years are expected to be achievable using some form of MEPS, and would

contribute significantly to lowering New Zealand’s energy growth profile. Standby power of

around 6W is also a significant contributor to the overall TV power use, and a reduction of

some 30% could be achieved, with a long term goal of less than 1W.

In Europe, there are a number of initiatives to encourage industry best practice through a

voluntary energy labelling scheme, which uses an Energy Efficiency Index. At least 20% of

analogue TVs already on the market in Europe comply with this index. Mandatory or

obligatory programs are the Japanese Top Runner program, and China is planning the

imminent introduction of a labelling and MEPS program within the next year. However

“business as usual” will also produce a natural reduction in energy usage for TVs of 2% per

year from savings due to design improvements by manufacturers.

It will be important to ensure that a New Zealand or Australasian MEPS scheme is compatible

with other national schemes that have a larger manufacturing or consumer base. It is

anticipated that contracts for TV purchase will have to include requirements for type testing

from overseas test laboratories and possibly labelling.

Page 4

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 8

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

The effect of the Trans-Tasman Mutual Recognition Agreement means that goods that are

acceptable for sale in one jurisdiction can legally be sold anywhere in Australia and New

Zealand. If Australia has a mandatory MEPS regime − which now seems unlikely − and New

Zealand does not, theoretically it would be possible to import non-compliant TVs to Australia

although the dangers are more apparent than real.

The introduction of a MEPS scheme would see annual energy savings increase from 8 GWh in

2006 to 29 GWh in 2025, with a cumulative saving in this period of 392 GWh. In addition

avoided power costs would save additional carbon charges with a net present value of the

cumulative savings till 2025 of $10.78 million.

The cost of applying MEPS would be largely absorbed by retailers and consumers, but could

attract annual administration costs of $100,000 with an NPV of $2.2 million. Compared with

the NPV of the electricity saved of $8.3 million, there is a substantial benefit cost ratio of

almost four. If the savings in carbon charges are included the benefits are almost doubled.

Although Australia originally aimed to introduce a combined MEPS/labelling scheme by 2006,

recent stakeholder feedback in Australia has opposed mandatory labelling, and it is now

unlikely to proceed, although voluntary labelling and MEPS will still go ahead. It would still

be advisable to keep our alignment with Australia, and it is recommended that New Zealand

introduce a similar scheme to whatever is finally agreed to in Australia.

Further consultation with the importers and major retailers will be necessary to ensure that

there is no undue resistance to the scheme, to maximise compliance and adherence to the

principles of the scheme. It should be possible to introduce such a MEPS and labelling scheme

by the end of 2006 if decisions and consultation begin as soon as possible.

Page 5

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 9

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

1 Introduction

1.1 Background

In November 2004 the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority commissioned Wise

Analysis Ltd to provide a review of the document “Minimum Energy Performance Standards −

Televisions”

Ltd. In particular this report was to “provide a New Zealand perspective to the differences

between the two countries with respect to:

• markets, including a quantitative discussion compatible with the section entitles

• available technologies

• economic implications (especially costs, and energy savings).”

As background to the Australian report, the Australian National Appliance and Equipment

Energy Efficiency Committee (NAEEEC) had tracked over three years the energy usage − in

particular standby power consumption − of appliances sold in retail outlets across Australia.

NAEEEC also had an intrusive survey of standby consumption in households, and had a

telephone survey done of 800 households to determine appliance ownership and usage. This

meaningful research data became the backbone of the Australian Government’s standby policy

development.

Leading on from this research, in 2002 the Australian Ministerial Council on Energy in 2002

released a policy document Money Isn’t all You’re Saving

Power Strategy 2002 – 2012. The strategy outlined the products and appliances that required

“immediate” or “subsequent” action in the standby power program, among which were

televisions

of use including on-mode and not just standby modes, might better meet the Australian

government’s efficiency goals. A report was thus commissioned to consider a range of policy

options, including mandatory measures like appliance energy rating labelling and Minimum

Energy Performance Standards (MEPS), to achieve that outcome. The report also investigated

the potential for energy and greenhouse savings through the use of a combination of policy

tools.

Much of the data in the Australian report, for example on power measurements could not be

independently verified, and has been taken as given. In addition the depth of demographic

information obtainable in New Zealand was also limited compared with Australia. However

the key to the study is not so much the starting data as the assumptions made as to future

growth of the stock of televisions, and it’s make up and changes to efficiency. The assumptions

made in this report are given later in 9.1.

A general comparison of the two countries is given in the following table:

1

which was prepared for the Australian Greenhouse Office by Energy Consult Pty

“Market Profile”

2

outlining Australia’s Standby

3

. Further research for NAEEEC4 suggested that a program that examined all modes

1

Minimum Energy Performance Standards: Televisions, NAEEEP Report 2004/11 (prepared for prepared for the Australian Greenhouse

Office

2

Money Isn’t All You’re Saving, Australia’s Standby Power Strategy 2002-2012, MCE

3

Where ever the term “televisions” appears in this report without further descriptive information, the term covers all television types,

including digital, wide screen, plasma, rear projection, CRT, etc.

4

Sustainable Solutions A Study of Home Entertainment Equipment Operational Energy Use Issues. NAEEEC 2003

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Page 6

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 10

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

Table 1: General comparison between New Zealand and Australia

New Zealand Australia

Area

Population

GDP

268,000 sq km 7,682,300 sq km

4 million 20 million

$120 billion = A$105 billion $750 billion

Per capita GDP NZ$30,000 = A$26,000 A$37,000

Principal exports

Primary (rural) products (54%) Resources (45%), rural (30%)

On a purely population basis the ratio between Australia to New Zealand is thus approximately

fivefold.

2 Product Description

2.1 General

Analogue colour televisions using cathode ray tube (CRT) technology are currently the most

common form of television used in the residential sector in both New Zealand and Australia.

They are based on the European PAL system with free to air broadcasts using VHF and UHF

bands. There are also various pay TV broadcasts made using UHF via microwave, and satellite

and cable using digital technology (these usually go through a converter/decoder to product a

suitable analogue output).

The most significant change coming to television in both Australia and New Zealand since its

introduction in 1950s is the introduction of digital television which is currently being trialled in

Auckland, and was enabled in Australia in 2001 by legislation. Digital television was launched

in the five mainland metropolitan areas (Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide, Perth and Brisbane) on

1 January 2002. In Australia, broadcasters are required to deliver a hybrid system of SDTV

with some HDTV programming where possible. Broadcasters in Australia must provide at least

20 hours of digital programs within two years of commencing. Trial digital TV broadcasts are

being made in Auckland.

For consumers, digital television means clearer, sharper pictures and a reduction in the

interference and ghosting that currently affect many viewers in built-up areas or where there is

hilly terrain. The change to digital television will also enable viewers to receive datacasting

and enhanced television services that may include subtitles, captioning, further information on

programming and a choice of viewing angles. No date for the ceasing analogue transmission

has been set in New Zealand, although 2008 has been quoted for Australia. To be able to watch

television, consumers with analogue sets will have to purchase a set top box (STB) which will

convert digital broadcasts to analogue.

The Television New Zealand 2004 annual report states that: “For New Zealand households to

convert to a fully digital environment there needs to be investment in new distribution

infrastructure as well as additional and enhanced services from television broadcasters. This

infrastructure will take at least a decade to implement.” This would put the date at which the

changeover to digital technology could occur at approximately 2014, although some service

could be introduced gradually before then.

Digital television signals can be transmitted in either standard definition or high definition.

Standard-definition television (SDTV) reportedly has improved reception capability when

Page 7

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 11

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

compared with existing analogue services while High-definition television (HDTV) provides

cinema-quality viewing with surround sound. Digital television will be broadcast in widescreen format in both SDTV and HDTV (HDTV broadcasting began only recently). New

Zealand has committed to the Digital Video Broadcasting (DVB) European-based standards.

A summary of the options available to consumers is as follows:

2.2 Transmission Types

The type of transmission affects the configuration of televisions and thus the features supplied,

which in turn affects the power consumption of the set.

(a) Analogue

This is currently the most widely available transmission option that comes at no additional cost

to the consumer other than the initial purchase of a television unit. Television units using this

method of transmission will require a STB to receive a signal as analogue is phased out and

digital transmission phased in around 2008 in Australia, and probably later in New Zealand.

(b) Standard-Definition TV (SDTV)

SDTVs give the consumer all of the benefits of the basic set-top box as well as a digital picture

in widescreen format. New Zealand is planning to introduce SDTV digital TV transmission in

the future.

(c) High Definition TV (HDTV)

HDTVs receive both HDTV and SDTV signals and display digital HDTV pictures in cinema

quality, wide-screen 16:9 format. A HDTV set will also provide all of the benefits of a basic

set-top box. More common in the market are Digital Display Devices, which will display both

SD and HD signals in a 16:9 wide-screen format.

Digital Display Devices are typically LCD or plasma screens which will only display digital

signals and require a set-top box to receive the digital or analogue TV transmission and convert

it to digital.

2.3 Television Receiver Types

A brief description of television types is provided below. All of the television types described

below with the exception of CRT television types may have the standard analogue, SDTV or

HDTV receiver types. More detail on the technology used is provided in NAEEEP Report

2004/11

5

.

2.3.1 TV Technology

There are a number of technologies used to display the image to be viewed. Common

technologies however relate to features such as passive standby. Older sets had an on/off

switch which physically removed the electricity supply from power supply components. The

5

NAEEEP Report 2004/11 (Appendix B: Television Technology Types p17).

Page 8

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 12

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

advent of remote switching controls made it imperative that the voltage was removed by a solid

state switching device, able to be turned on by the remote control. But this “holding off” uses

power itself, and when the TV is in this mode it is termed “passive standby” or just standby. In

this report where standby is used it means passive standby. The same technology is used for

other remote controlled devices such as set top boxes.

(a) Standard Cathode Ray Tube (CRT)

As noted in 2.1, most existing televisions in Australia and New Zealand use cathode ray tube

(CRT) technology and these existing televisions are usually set up to receive analogue

broadcasts. CRT TVs can be purchased in standard (4:3) or wide screen format (16:9).

The features provided by a TV affect the power usage. The features on a CRT TV that have

most impact on power (with the mean effect in brackets − Huenges Wajer et al

6

) are 100 Hz

picture frequency (37.8W), stereo sound (11.5W), surround sound (15.2W), second tuner

(12.2W), satellite tuner (10.1W). Not all these features are offered in New Zealand. Screen size

itself has a relatively minor effect.

(b) Slimline televisions

While the sales volume of slimline televisions in New Zealand in 2003 was 5.2% compared

with 95% CRT, by 2004 this had increased to 9.6% slimline televisions. Sales of LCD TVs in

Australia have also been low to date, largely because of their cost, but recent improvements to

LCD technology and an international trend toward LCD televisions may see prices fall and the

market share increase. LCD televisions boast lower energy consumption levels compared with

other television types. For example the NAEEEC Store Survey measurements showed a meanin-use power of 56.4W for LCD sets compared with 79.1W for CRT sets.

(i) Liquid Crystal Display (LCD)

LCD televisions utilise the same technology as computer monitors and until very recently have

had smaller screens than conventional full sized CRT technology and plasma units. They were

also considerably more expensive than CRT technology, comparable size for size with plasma

screens. However, LCD televisions are brighter, crisper, and have a better contrast ratio and a

better viewing angle compared to plasma units and a much greater life expectancy.

(ii) Plasma Screens and TVs

In simple terms plasma screens are made up of lots of tiny fluorescent lights to produce a high

quality image for television viewing. The technology allows for a greater viewing angle - 160

degrees compared to about 60 degrees in the standard CRT televisions. As such, it isn’t

necessary to be directly in front of the television to be able to view the picture. Plasma screens

boast a wide-screen format, light weight and low radiation compared to CRT television types.

Many of the plasma screens available require a set top box, VCR or home theatre package to

produce images, as they do not contain a TV tuner, although more models are now being

produced that do contain an integrated digital or analogue tuner. Plasma televisions are plasma

screens with built in television tuners.

6

Huenges Wajer B.P.F., Siderius P.J.S., Analysis of Energy Consumption and Efficiency Potential for TVs in on-mode, EC report November

1998 http://www.vhknet.com/download/TV_on-mode_final_report.pdf

Page 9

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 13

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

Plasma and rear projection sets use approximately double the power of CRT type TVs. For

example the NAEEEC Store Survey measurements showed a mean-in-use power of 156.5W

for Plasma sets, and 150.4W for projection sets, compared with 79.1W for CRT sets.

(iii) Rear Projection

Rear projection televisions are wide-screen televisions that beam images from three picture

tubes (CRTs) or LCD projectors to the back of a 102 cm to 150-plus cm screen. The main

attraction of rear projection televisions is that they provide a wide-screen or cinematic view for

a more comparable price to plasma or LCD wide-screen television technologies. These screens

can be in the 4:3 or 16:9 format.

(iv) Set top boxes

Set top boxes for conversion of digital to analogue signals are similar to the decoders presently

used by Sky and Telstra. Typical energy consumptions range between 12W and 17W. Standby

figures would typically be 8 to 10W or less (see Table 7). Standby figures of 2W are

achievable.

2.3.2 TV Formats

Regular televisions have a width to height ratio (or aspect ratio) of 4:3, whereas widescreen

televisions have an aspect ratio of 16:9, making the unit almost twice as wide as it is high. A

VCR normally shows videos in the standard format, while a DVD player has options to enable

the user to watch movies in wide-screen format. The wide-screen is designed to give the user a

greater television experience by making the television appear more like a cinema screen. The

actual screen size of wide-screen televisions varies and usually starts at around 66cm. There

are many variations on the types of wide-screen televisions available and these are described in

detail overleaf.

2.4 Sources of Product

New Zealand imports totally all of its televisions, and has done for many years. Australia is

also primarily an importer of televisions, with the exception of one brand Matsushita that still

manufactures in NSW.

The primary source for New Zealand supply is China, with a smaller number originating in

Europe, Japan, and Korea. However the place of manufacture is diverse, leading to televisions

being imported from a wide range of countries, mainly throughout Asia.

3 Market Profile

3.1 All Television Types

Television manufacturing and assembly in New Zealand finally ceased in 1990-91 with Fisher

& Paykel, the licensees for Panasonic being the last. Colour televisions first became readily

available in New Zealand in 1974 to coincide with the country’s hosting of the 1974

Commonwealth Games (black and white TV transmission was first introduced in New Zealand

in 1960).

Page 10

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 14

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

Data on the overall ownership profile for televisions in New Zealand became limited when

licensing ceased in 1999, and data collection is now only carried out by Statistics New Zealand

and through surveys by firms such as A C Nielsen, all of whom charge for detailed

information.

The data in Table 2 was obtained from Statistics New Zealand’s Household Economic Survey,

and excludes TVs in commercial premises such as hotels. In using it for the purposes of

economic analysis, it will thus produce conservative numbers. It does indicate that the number

of principal (first or only) TVs in households is 1,463,900 compared with a total number of

TVs of 2,785,600, i.e. on average almost every household has two TVs.

Table 2: Estimated number of TVs in households for the year ended June 2004

Number of TVs in

household

Estimated

number of

households

Percent

Total No

of TVs

Equivalent

Australian

Data (2000) %

0 30,600 2 0 0.5

1 590,200 39.5 590,200 38.6

2 541,900 36.3 1,083,800 39.4

3 242,200 16.2 726,600 15.3

4 63,000 4.2 252,000 ) 6.2

5+ 26,600 1.8 133,000 )

Total all households 1,494,500 100 2,785,600 100

Note: Household numbers are rounded to the nearest hundred

Source: Statistics New Zealand, Household Economic Survey

The available Australian data suggests that television penetration probably increased linearly

from 0% in 1956 (the date of introduction) to about 90% by 1975. The New Zealand data

appears to lag the Australian data slightly in some categories, but probably not significantly.

Television ownership is in excess of 1.86 televisions per household.

Table 3: Penetration of Television Ownership – Australia & New Zealand

New Zealand (Year and source) Australia (Year and source)

1959 (no TV) 0% 1955 (no TV) 0%

1961 (Census − NSW)

1966 (Census − NSW)

1970 (Census − NSW)

48%

70%

90%

2000 (NAEEEC) 99.5%

2004 (Statistics NZ) 98%

The average age of TVs in New Zealand is not known. Current economic life of standard CRT

style TVs is assessed as averaging 7 years, with 70% falling between 6-11 years. Before the

advent of video game accessories such as Playstation and X-Box older TVs were passed on to

children for their bedroom, or taken to holiday homes. However with the advent of

Audio/Video (A/V) input requirements for Playstations etc, more modern TVs were demanded

by users. As the prices for smaller new TVs dropped, the older stock was replaced, although

the older sets probably still account for the 22% of homes with 3 or more TVs.

Based on a seven year life, the stock of TVs in households owning one and two TVs is

approximately 1.7 million and an approximate sales figure would be one seventh, or 240,000

Page 11

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 15

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

per year plus an allowance for market growth. Figures for sales into the retail market show that

the New Zealand market for the last three years is as follows:

Table 4A: New Zealand annual TV market based on type

2001-02 units 2002-03 units 2003-04 units

Standard 4:3

Widescreen 16:9

Unidentified

173,967 231,095 272,080

9,170 23,089 40,784

875 5,983

Total 183,967 255,059 318,847

Table 4B: New Zealand annual TV market based on feature

2001-02 units 2002-03 units 2003-04 units

CRT

LCD

Rear projection

Plasma

Unidentified

178,603 242,474 290,499

100 1,604 7,846

4,222 8,906 13,887

212 2,075 6,152

463

Total 183,967 255,059 318,847

The sales of new TVs in 2004 are 11.45% of the total number of TVs estimated to be in the

country. On that basis the stock is replaced approximately just under every nine years. This

equates to the assessed current economic life of seven years for TVs assessed by

manufacturers.

The size of the New Zealand market, as an influencing tool is small. With typical factory

production rates of 75,000 units per month, the entire New Zealand market can be supplied by

just over four month’s production in Europe or China from a single factory.

The market share data for New Zealand is not readily available, but the market is dominated by

three major players − Philips, Sony and Panasonic who together account for 80% of total

7

sales

. The comparable figures for market share in Australia by these manufacturers, is only

19.5%. The market in New Zealand is thus more concentrated in the hands of major players,

than in Australia. However the total number of brands is still similar, but the lesser known

brands have only a niche market.

3.2 Wide-screen Televisions

Slimline TVs - the majority of which are widescreen format - have increased their share of the

market from 4.9% to 8.7% between 2003 and 2004, an increase of 77%, compared with an

increase in CRT sets of only 20%. This suggests that both slimline and wide-screen televisions

are increasing their market share in New Zealand rapidly at the expense of traditional CRT

models.

Very little Australian data exists on penetration and ownership of wide-screen televisions

either. Between 2001 and 2002 sales figures reportedly tripled. Between 2002 and 2003 sales

of widescreen CRT TVs increased by 50%, plasma TVs by 100% and LCDs increased from a

zero base. The overall increase was 78%.

7

Personal communication from Garth Wyllie, Consumer Electronics Association of New Zealand.

Page 12

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 16

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

Summary − TV demographics

The total number of TVs in New Zealand is around 2,785,600 with overall television

penetration is around 98%. Television ownership is now in excess of 1.86 televisions per

household and increasing slightly. The TV market is dominated by three major suppliers

Sony, Philips and Panasonic. Slimline TVs are increasing their market share with almost a

doubling of sales between 2003 and 2004. If CRT widescreens are included, there was

probably a trebling of this sector.

4 Energy Consumption

4.1 Household Energy Consumption

The impacts of policies to improve the efficiency of televisions is based largely on future sales

of TVs, and changes to the efficiency of these technologies over the next 15 to 20 years given

current life expectations of these appliances of seven years.

Energy consumption in New Zealand households has been surveyed since 1997 by BRANZ for

EECA in its Household Energy End-use Project (HEEP)

annual energy consumption of all televisions in New Zealand is estimated to be lie between 70

and 325 GWh.

The usage data for TVs in NZ has been surveyed by BRANZ

the purposes of this report, an average of 4 hours in-use and 20 hours standby a day has been

assumed. Second and subsequent TVs usage is 50% of the principal TV.

The energy consumption is estimated as follows:

Average power usage (in use) = 80W

Standby = 6W

Usage: Watching = 4 hours/day

Standby = 20 hours/day

Average energy usage per day = (20 x 6) + (4 x 80) Wh

= 440 Wh

Total population of TVs = 2,785,600

Average total energy per year (344 days) = 422 GWh

Note: 344 days is the commonly used figure for number of days used, and assumes 21

days of out of home vacation.

The figure of 422 GWh assumes that the entire number of TVs in New Zealand of 2,785,600 is

used in the same way for a certain number of hours per year, as above. However if only the

principal TV in a household with one or more TVs is considered to have the stated usage, i.e. a

total principal TV population of 1,463,900 then this figure drops to 221 GWh. Energy usage

thus falls within the range from 221 to 422 GWh. A more realistic usage assumption is that the

8

Stoecklein A., Pollard, A., Isaacs, N. (ed), Ryan, G., Fitzgerald, G., James, B., & Pool, F. 1997 Energy Use in New Zealand Households:

Report on the Household Energy End-use Project (HEEP) – Year 1. Energy Efficiency & Conservation Authority (EECA), Wellington.

9

Stoecklein, A. Pollard A., Isaacs N., Bishop S. and James B., Energy end-use and socio/demographic occupant characteristics of New

Zealand households, Conference paper CP52, 1998 http://www.branz.co.nz/branzltd/publications/pdfs/con52.pdf

Page 13

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

8

. Using data from HEEP the total

9

but the data is inconclusive. For

−

Page 17

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

principal TV is assumed to have the assumed usage of 440 Wh above, but second and

subsequent TVs in a household use only 50% of this energy or 220 Wh per day. The total

energy use would then be 322 GWh. These figures are shown in the following table:

Table 5: Energy usage against TV penetration

Number of TVs in

household

Estimated

number of

households

Total

number

of TVs

Energy usage

GWh

(440Wh/day)*

0 30,600 0 0

1 590,200 590,200 89

2 541,900 1,083,800 123

3 242,200 726,600 73

4 63,000 252,000 24

5+ 26,600 133,000 12

Total all households 1,494,500 2,785,600 322

* Second and subsequent TVs are assumed to use 50% of this figure.

Total energy consumption of all televisions in Australia is estimated at 1,055 GWh pa in 2003

(Harrington & Foster 1999

10

), and is estimated to increase to 1,361 GWh by 2010. The

proportion of total household energy use attributed to televisions is also estimated to be 5% −

considerably greater than a clothes washer (1%), clothes dryer (1%) or dishwasher (1%) and

only marginally less than refrigerators/freezers (10%). All of these household appliances

already carry an energy rating label and freezers are subject to MEPS.

As an indicative figure only, on a population pro rata basis, New Zealand’s TV energy

consumption would be approximately 20% of the Australian estimate or 211 GWh − somewhat

less than the 322 GWh above, even making allowances for New Zealand’s population of TVs

possibly being somewhat older than the equivalent Australian population.

A best guess estimate is probably that the present energy consumption by all TVs is around 320

GWh. According to some commentators, normal appliance technology improvements under

“business as usual” will improve the efficiency of conventional TV designs by around 2% per

year (see Table 9). However changes in the market mix may act in the opposite direction.

Slimline TVs do not necessarily use less energy - for example LCDs use less energy, but

plasma (and projection) TVs use significantly more - 300W or greater. Whilst Table 4B

indicates that slimline TVs have only 5% of CRT market share, LCD sales increased fivefold

and plasma sales threefold in the last year. Ultimately whether the energy usage continues to

fall, will depend whether the market moves more towards LCD or plasma screens in the next 5

to10 years.

New Zealand’s total electrical energy consumption is presently of the order of 40,000 GWh,

and increasing by 2% per annum (800 GWh). The present total TV energy consumption of 320

GWh is thus of the order of 40% of the annual growth in energy usage. A 10% saving by using

some form of MEPS is thus not insignificant in managing the electricity demand profile

growth.

10

Harrington, L & Damnics, M. 2003, Energy Labelling and Standards Programs Throughout the World, National Appliance and Equipment Energy

Efficiency Committee, Canberra.

Page 14

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 18

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

4.2 Trends in TV Power Consumption

No available measurement data has been obtained for New Zealand. The energy consumption

characteristics of TVs will however be similar to those measured in Australian store surveys

and intrusive surveys commissioned by NAEEEC4 over the last four years, and previous

studies of residential appliances are summarized below. The report cautions that the data

“should be treated with careful optimism as many factors influence the survey and only future

monitoring will reveal if in-use consumption is actually trending downwards”.

The various television types are discussed below.

(a) Standard CRT Televisions

The data in MEPS-TV (Fig 2ff) shows that the majority of televisions use between 50W and

100W although 2003 saw an increase in those using less than 50W in-use. Average in-use

power consumption fell significantly from 2001 from 2002 to 2003 and 2003-04 from around

88W to 79W, a reduction of some 10%.

As well from 2001 to 2004 average standby power fell from around 6W to 4.1W a reduction of

some 30%. In the off mode all TVs consumed less than 1W with the vast majority having zero

consumption.

(b) LCD Televisions

The data in MEPS-TV (Fig 4ff) was based on limited numbers of units measured, apart from

2003-04. Thus no trend was evident. The average in-use consumption was 56.4W, ranging

from 24W to 134W. Standby showed large differences ranging from 0.6W to 18.5W, averaging

2.8W. Data from the European website Market Transformation Program

11

for LCD TVs

indicate that for in-use consumption best practice is currently (2003):

Table 6: Best practice for LCD TVs

In-use consumption Watts Standby Watts

Best Practice 35 Best Practice 1

Average 50 Average 3

Maximum 75 Maximum 5

(c) Projection Televisions

The data in MEPS-TV (Fig 7ff) shows an average in-use power of 156W ranging from 94W to

223W. Standby averaged 7.7W ranging from 0.4W to 45W. The average off mode

consumption was 0.1W.

(d) Plasma Televisions

Plasma TVs use considerably more energy than other types of TV. The data in MEPS-TV (Fig

9ff) showed average in-use consumption in 2003-04 was 150W, down from 292.4 in 2003. The

maximum energy used showed a similar decline. Standby averaged 2.4W, ranging from 0.7W

to 4.4W. Some 25% of sets did not have an on/off switch.

11

URL − http://www.mtprog.com

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Page 15

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 19

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

(e) Set top boxes

Figures for US set top box power usage were given in Rainer et al 2004.

12

Table 7: Average Set Top Box Power Levels

Type Standby (W) In-use (W)

Analogue cable 10 12

Digital cable 22 23

Satellite 16 17

Internet Protocol TV 14 15

Digital TV adaptor 8 17

They say that “Reducing the energy use of set-top boxes is complicated by their

multiple complex operating and communication modes. Although improvements in

power supply design and efficiency will be effective in reducing STB energy use, the

major energy savings will be obtained through the use of protocols and software to

better control the device (energy management).”

Summary − TV energy consumption

Overall television energy consumption is around 320 GWh, and could reduce over

the next 5-7 years by 20% if a MEPS regime is introduced. Although there is

considerable variation between manufacturers, energy consumption of various TV

types is likely to continue to fall as technology improves.

5 Technology Scope for Energy Efficiency

A 1998 report by Huenges and Siderius13 stated that TV in-use energy consumption can be

reduced through two options:

• Options regarding components:

o Use less

o Use more efficient

o Use specifically designed components

• Options regarding design (hardware and software)

o Lower voltages

o Fewer voltages

o Power management

At that time the data showed a trend to decreasing power consumption only for smaller TVs

(below 49cm). For medium and larger sizes there was still a large variation. Because of their

short life times and high ownership growth rates, STBs perhaps also provide a great

opportunity for significant short term energy savings.

12

“What's On the TV: Trends in U.S. Set-Top Box Energy Use, Design, and Regulation” Rainer L, Thorne Amann J., Hershberg C., Meier A.,

Nordman B, IEA Conference paper URL − http://www.iea.org/dbtw-wpd/textbase/papers/2004/am_stb.pdf

13

Huenges Wajer B.P.F., Siderius P.J.S., Analysis of Energy Consumption and Efficiency Potential for TVs in on-mode, EC report November

1998 http://www.vhknet.com/download/TV_on-mode_final_report.pdf

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 16

Page 20

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

6 Standards Development

There are currently no national or international standards applying to the energy consumption

of TVs. A new joint standard, AS/NZS 62087:2004 that defines the methods of measurement

for the power consumption of audio, video and related equipment has recently been published.

This standard derives from international standard IEC 62087 and covers televisions, VCRs,

Set Top Boxes, audio equipment (separate components) and combination equipment (such as

integrated stereos).

The Australian government is also currently communicating with the relevant committees on

developing a standard that includes voluntary efficiency performance requirements for standby

energy consumption. These initial voluntary requirements would be published by SAI in a new

part of the AS/NZS 62301, which provides a test procedure to determine the power

consumption of a range of appliances in standby mode. The interim standard, which is identical

to the IEC draft TC59 WG/9 (IEC 62301) is a provisional Standard with the two year life

intended to provide a guide to the direction that future standardisation may take. By then it is

anticipated that the IEC standard will have been published and it is expected that this will be

subsequently adopted as the joint Australian/New Zealand standard.

7 Test Laboratory Capability

The need for local test laboratories to carry out tests on overseas manufactured TVs has not

been demonstrated. It is anticipated that contracts for purchase will include requirements for

type testing and possibly labelling. International TV suppliers have been testing to the IEC

62087 for a number of years, and the acceptance of international testing laboratory test results

should be acceptable in any proposed MEPS regime.

The ability of local Australasian testing laboratories to perform the tests in accordance with

AS62087 is also certainly feasible as the test equipment and methodology is not different from

standard testing requirements.

8 International Energy Efficiency Programs

8.1 Voluntary Programs

Various voluntary programs that address standby and in-use power consumption exist

internationally. The international ENERGY STAR Program is the only voluntary program that

operates in Australia and is recognized in New Zealand. It addresses standby power

consumption primarily of office equipment but not currently in-use consumption.

In Europe, there are a number of initiatives that target power consumption in televisions. The

Group for Energy Efficient Appliances (GEEA), which is made up of representatives from

European national energy agencies and government departments, encourages industry best

practice through a voluntary energy labelling scheme, which uses an Energy Efficiency Index

that takes into consideration energy consumption in-use. At least 20% of the analogue TVs

already on the market in Europe comply with this index.

Page 17

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 21

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

The European Association of Consumer Electronics Manufacturers (EACEM) established a

voluntary agreement in 1997 with the European Commission to target standby losses of TVs.

EACEM has now merged its activities with the European Information & Communications

Technology Industry Association and is now known as the European Information,

Communications and Consumer Electronics Technology Industry Associations (EICTA). The

updated agreement covers CRT based televisions, non CRT based televisions and DVD’s and

now addresses on mode consumption in addition to standby. The aim is to reduce standby

power consumption to a maximum of 1W by 2007. The agreement also aims for a minimum of

5% improvement in energy efficiency by 2007.

The energy efficiency index is a formula which takes into consideration numerous factors such

as on mode consumption, standby consumption and screen size/format/type. The European

Commission also funds a pan-European database of energy efficient appliances called

HomeSpeed. The EC have also developed an Eco-Label (“Flower”) that applies to more

environmentally friendly products and services.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) has a “One Watt Initiative” energy saving program to

cut world-wide electricity losses from appliances in stand-by, launched in 1999. This aims to

encourage equipment manufacturers towards consuming no more than one watt when the

equipment is in standby mode. The Australian Government has endorsed the one watt standby

target for appliances sold in Australia. New Zealand has yet to formally endorse targets.

8.2 Mandatory Programs

So far no mandatory programs set minimum standards for TV energy efficiency although

China is planning the introduction of a labelling and MEPS program within the next year. The

Japanese Top Runner program, is based around target standard values for energy consumption

efficiency in accordance with the Energy Conservation Law, and is obligatory for

manufacturers to adhere to them to enhance the energy consumption efficiency of their

products on a weighted average basis. In contrast to other overseas jurisdictions however,

Japanese standards do not exclude from the market equipment that fails to satisfy the standards.

It will be important to ensure that a New Zealand or Australasian MEPS scheme is compatible

with other such schemes, with a larger manufacturing or consumer base.

Page 18

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 22

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

Table 8 Summary of Testing Standards and Energy Efficiency Programs

Summary − International Standards and Programs

Testing standards are now available for standby power measurement, but no standards

currently exist for energy consumption in-use.

Voluntary programs such as Energy Star only target standby energy use. The Energy

Efficiency Index promoted in Europe covers in-use mode and at least 20% of European

sets comply.

Any New Zealand MEPS scheme should be compatible with any overseas obligatory

programs such as Japan’s “Top Runner” initiative.

Page 19

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 23

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

9 Economic Implications

9.1 Energy Cost Savings

The key driver for introducing a MEPS regime is the achievement of savings in the cost of

energy used in TVs, both the on and standby modes.

In arriving at a set of figures to carry out the economic analysis a number of assumptions were

necessary:

• The first and most basic assumption is the number of TVs, and how that will change over

time. Rather than a compounding percentage increase it is likely that the growth of TV

numbers will follow a logistical growth or S-curve with saturation effects. The degree to

which this applies depends on a number of factors, but a key one is the population

growth of New Zealand. Statistics New Zealand predict that with their mid-range Series

5 projection, the population which is currently 4.08 million will reach - and peak million by 2041. This assumes, amongst other factors, a net migration gain of 10,000 per

year.

• The numbers of new TVs currently sold is 318,847 annually an increase of 25% on the

previous year. This degree of increase is unsustainable in the long term, and for the

purposes of this analysis the rate of increase was reduced each year by a factor

proportional to the inverse of the population increase to the power of five. This gives a

reasonable approximation to an S-curve effect. All new TVs are assumed to be used as

the principal TV in a household, with 20% of principal TVs being retired to second and

subsequent TV status.

at 5

• The number of TVs disposed of - or becoming unused - was assumed to be 10% of the

stock of second and subsequent TVs. At this rate, the number of disposed TVs is always

less than the number of new TVs, allowing for a build-up of numbers.

• Average annual energy use per TV now is 152 kWh. This is based on the figures in 4.1 -

average TV power for the set mix at present of 80w, and on-use of 4 hours/day with 20

hours standby giving 440Wh for the first or principal TV, for 344 days a year. The

second and subsequent TVs are assumed to use 50% of the energy of the principal TV

due to reduced on-mode periods, or 220Wh.

• Business as usual (BAU) will produce a natural reduction in energy usage for TVs of 2%

per year

14

(Fig 6.1) from so-called autonomous - natural design improvement savings - by

manufacturers.

• Autonomous savings, and moves towards more energy efficient LCD slimline TVs may

however also be offset by moves of consumers to larger plasma slimline TVs, or those

with more features such as IRD, at the expense of medium size TVs. Thus at this stage it is

probably wise to assume no net efficiency improvements in the overall new TV stock.

14

Huenges Wajer B.P.F., Siderius P.J.S., Analysis of Energy Consumption and Efficiency Potential for TVs in on-mode, EC report November

1998 http://www.vhknet.com/download/TV_on-mode_final_report.pdf

Page 20

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 24

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

Figure 1 − Chart of Television Set Numbers in New Zealand.

10,000,000

9,000,000

8,000,000

7,000,000

Total No. of TVs (year start)

New TVs

6,000,000

5,000,000

4,000,000

3,000,000

Number of TVs

2,000,000

1,000,000

0

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

2023

2024

2025

Figure 2 − Energy Usage Figures for Televisions in New Zealand − BAU and MEPS.

700

600

500

400

300

Tota l energy use (GWh) - BAU

Tota l energy use (GWh) - MEPS

Energy usage (GWh)

200

100

0

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

2023

2024

2025

The total energy saved is 8 GWh in 2006, when MEPS is introduced, rising to 29 GWh in

2025. The cumulative energy savings between 2006 and 2025 is 392 GWh, and the net present

value of these savings at a discount rate of 10% based on a current energy cost of 7.3 c/kWh is

$8.3 million.

9.2 Trans-Tasman Trade Agreement

CER is a series of agreements and arrangements that began with the entry into force on 1

January 1983 of the New Zealand Australia Closer Economic Relations Trade Agreement.

Total free trade in goods was achieved by 1990 (five years ahead of schedule) with the

elimination of all tariffs and quantitative restrictions. The Trans-Tasman Mutual Recognition

Agreement of goods (and occupations) means that goods that are acceptable for sale in one

jurisdiction can legally be sold anywhere in Australia and New Zealand. A joint communiqué

Page 21

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 25

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

from the Australia New Zealand Trade Ministers' Meeting in 2003 stated that: “To this end, we

are committed to ensuring that the Arrangement is supported by the continued development of

joint Australian and New Zealand standards. We recognise the importance of joint standards to

our business communities.”

There are no specific dispute resolution procedures. The close and long-standing political

relationship between Australia and New Zealand means that any issues of grievance or concern

are addressed through discussion between the two governments. The effect of the TTMRA is

that if Australia has a MEPS regime, whilst New Zealand does not, theoretically it would be

possible to import non-compliant TVs to Australia on the grounds that the equivalent set was

acceptable for sale in New Zealand. In practice the selling margin between the two grades of

set, would not be sufficient to offset the loss of marketing edge of such a move. Thus the

dangers are more apparent than real.

9.3 Greenhouse Gas Reduction Potential

Avoided power costs are usually considered to save energy at marginal generation costs, which

are thermal, and thus emit CO

Te Āpiti design document

from of 572 g CO

period is 635 g CO

/kWh in 2005, to 698 g CO2/kWh in 2025. The average over this 20 year

2

/kWh.

2

. The methodology is demonstrated in some detail in Meridian’s

2

15

which shows a CO2 emission factor for thermal generation rising

Annual energy savings increase from 8 GWh in 2006 to 29 GWh in 2025, with a cumulative

saving in this period of 392 GWh. The greenhouse gas reduction inherent in these figures

increases from 4,700 tonnes CO

-e/yr in 2006 to 20,000 tonnes CO2-e/yr in 2025. The net

2

present value of the cumulative savings costed at $15 per tonne, a conservative figure based on

estimates of the charge likely to apply from 1 April 2007, and a discount factor of 10% is

$10.78 million.

Figure 3 − Savings in CO

0.50

0.45

0.40

0.35

0.30

0.25

0.20

CO2)

0.15

0.10

Emissions (MT-e/ yr

0.05

0.00

Emissions − BAU and MEPS.

2

Emi ss i ons MT CO2-e/ y r (BAU)

Emissions MT CO2-e/yr (MEPS)

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

2020

2022

2024

15

Te Āpiti Wind Farm Project: Project Design Document (ERUPT 3) www.senter.nl/sites/erupt/contents/i001413/ meridian_energy_eru _03_

06_pdd_final.pdf

Page 22

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 26

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

10 Policy and Program Approaches to Improve Energy Efficiency

Table 9: Summary of program approaches/policy tools

10.1 Information Programs

As in Australia, apart from the ENERGY STAR program which will be familiar to workers in

office environment, or those using personal computers, there are no other programs currently in

New Zealand addressing the issue of energy efficiency of TVs. The ENERGY STAR program

does not address the issue of on-mode energy use.

10.2 Labelling Programs

Labelling programs can be voluntary, mandatory or a combination for part of the market.

Voluntary labelling is more in the nature of consumer information, providing comparative

information in a format agreed by the signatories. Mandatory labelling also provides

Page 23

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 27

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

consumer information similar to that currently applied to whitegoods, but in a format regulated

by standards. A MEPS regime is a government regulatory programme that not only covers

labelling but actively excludes from the market products that do not meet minimum energy

performance standards.

Realistic options for New Zealand will either be associated with other international programs,

since our TVs are sourced from overseas, or included as part of an integrated Australasian

MEPS approach.

Ideas canvassed in the AGO NAEEEP report are summarised in Table 9. The most acceptable

option appeared to be to develop a comparative star-based labelling system in conjunction with

the introduction of a MEPS regime for TVs.

10.3 Minimum Energy Performance Standards (MEPS)

MEPS are documents produced under the aegis of Standards New Zealand and/or Standards

Australia, which means that a product sold on the New Zealand market must comply with

specific criteria for energy efficiency. New Zealand works closely with Australia to ensure

MEPS levels are aligned. All of these standards are, or will soon be, joint standards with

Australia.

By introducing a mandatory MEPS regime, the aim is firstly (Stage 1) to remove the

approximately 30% of the least efficient new products available at the retail level; secondly

(Stage 2) to move towards the more stringent Japanese MEPS levels, and the EU targets.

It may be difficult for New Zealand to match the Japanese levels in the first instance as they are

very stringent MEPS although our product is primarily based on Japanese and to a lesser extent

European designed product, largely manufactured in Asia.

The EU has not implemented a MEPS, but has targeted reductions with voluntary agreements

with major suppliers. A voluntary agreement could work in New Zealand but could potentially

be sabotaged by the smaller suppliers ratcheting up their market share without having to

comply with the agreement.

As utilised in Europe, the method of measuring energy efficiency should take into

consideration the screen size, aspect ratio, type of receiver/processor, scan rate and other

consumer-desired features. This ensures that manufacturers are not penalised simply for

providing more features for consumers. The formulae for determining energy efficiency are

called algorithms, and the methodology used for a proposed MEPS would be similar to the

approach used by the EU’s GEEA voluntary labelling program and the European Industry SelfCommitment.

The EU has adopted a method of test, with the full support of the GEEA and EU, so there is no

need to consider other testing methods. Australia and New Zealand could use the EU methodof-test standard (IEC 62087), which has been adopted as an Australian New Zealand Standard

(AS/NZS 62087:2004: Methods of measurement for the power consumption of audio, video

and related equipment). However the Australian standards committee TE001 is now working

with the EU in reviewing the test method, and it is likely that it will adopt a new method that

simplifies the current test, allowing a comparison with all screen technologies. New Zealand is

currently not represented on this committee, but could be included.

Page 24

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 28

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

10.4 Costs of MEPS

The Australian TV MEPS report did not address this issue, but stated:

“A full economic study has not been conducted, as this usually is undertaken as part of the

Regulatory Impact Statement (RIS) process when more information is available. However, it is

worth noting that when mandatory programs are implemented through regulations, the

requirements apply equally to manufacturers and importers. As a result, any additional costs

of compliance are borne by all competitors. This situation is not always the case for voluntary

programs, where companies who ‘do the right thing’ might be undercut by other company’s

products which do not match their energy performance standards.”

The likely energy savings compared with the cost of introducing and operating a MEPS

scheme has been assessed. According to EECA the cost of running such a scheme is likely to

be less than $100,000 a year, together with some initial setup costs, of say equal value. The net

present value of these costs at a discount rate of 10% is $2.2 million. Compared with the NPV

of the electricity saved of $8.3 million, there is a substantial benefit cost ratio of approximately

four, above the threshold needed to proceed. If the savings in carbon charges are included the

benefit are almost doubled.

Secondly the cost of applying a MEPS regime would be partly borne by consumers. However

in practice because of the competitive nature of the market, these costs, which would only be

nominal, may not be passed on. For example a wide screen CRT TV that would retail for

$2,499, might attract additional MEPS costs of $5 per unit. Because of the pricing bands (or

points) used by retailers to set prices, where prices are set to keep below break points (e.g.

$2,499 rather than $2,550), unless the increase takes the new price into the next higher band, it

may not be applied.

Similarly the costs of applying and administering MEPS, apart from the testing and labelling of

product, need to be assessed and agglomerated with other already existing MEPS programs in

order to minimise them. This would be a matter of natural efficiency rather than a need to

justify the implementation of a MEPS regime.

Summary − Policy and Program Approaches to Improve Energy

Efficiency

Realistic policy options for New Zealand will either be associated with other international

programs, since our TVs are sourced from overseas, or included as part of an integrated

Australasian MEPS approach. Voluntary programs may be sufficient.

A New Zealand MEPS scheme should encourage the removal of the worst performing 30%

of sets at the retail level.

The costs of applying MEPS would likely be passed on by retailers, but due to the

competitive market may also be absorbed. Total costs of a MEPS scheme must be

minimised to achieve viable cost savings, as well as energy savings. The benefit cost ratio

of the present value of energy savings to costs of a MEPS scheme is approximately four,

excluding any carbon charging.

Page 25

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 29

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

11 Recommended Policy Options for New Zealand

11.1 General Policy Recommendations

Energy consumption of TVs in New Zealand is estimated to be 320 GWh, or around 5% of

total household use. This is approximately 40% of the annual increase in energy required by

New Zealand each year. The countries of origin for the TVs we import are implementing either

mandatory or voluntary policies to improve the efficiency of this growing form of energy

consumption.

In particular Australia originally aimed to introduce a combined MEPS/labelling scheme by

2006. However recent stakeholder feedback in Australia opposed mandatory labelling, and it is

unlikely to proceed, although voluntary labelling and MEPS will still go ahead.

It would be advisable to keep our alignment with Australia, and it is recommended that New

Zealand introduce a similar scheme to whatever is finally agreed to in Australia. MEPS and

comparative labelling is still a viable option with only voluntary labelling. It will be necessary

to rely on the competitive nature of the market to exclude products that don’t comply with

MEPS.

11.2 MEPS

A MEPS for televisions in New Zealand should be implemented in tandem with Australia.

Consultation with the importers and major retailers will be necessary to ensure that there is no

undue resistance to the scheme, to maximise compliance and adherence to the principles of the

scheme.

The MEPS should cover both on-mode and standby energy consumption. The setting of MEPS

levels should be designed initially, as in Australia to encourage the removal of the 30% of

worst performing TVs from the marketplace, and to match the best practice levels of our

product source countries. The correlation between energy efficiency indices for TVs and any

labelling scheme needs to be decided on in consultation with Australia.

The Australians already have an Australian Standards Committee TE 1 which may act as the

vehicle to implement the MEPS scheme. New Zealand would have to investigate

representation and integration of its policies with the work of that committee.

11.3 Labelling Scheme

The comparative labelling scheme proposed by Australia would follow the six-star energy

rating system based on the EU model. The purpose of such a label is to allow the consumer to

compare a TV within a particular technology (e.g. widescreen, SDTV, HDTV) and screen type

(e.g. CRT, LCD, plasma). Alternatively labels could be developed that merely compared all

technologies/screen types although this would be less useful. Considerable work is needed to

identify reference TV values, and levels of energy use for various star ratings.

It is not recommended that New Zealand do other than monitor this work, together with

Australia.

Page 26

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 30

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

11.4 Consultation

Industry, through its representative body the Consumer Electronics Association of New

Zealand have already made a submission on the AGO proposals regarding TVs. Their concerns

focused on the following aspects:

• The mandatory nature of the proposal, which they believe can be met by the market.

• The need for the scheme to apply across all screen types, rather than apply a CRT rating

to all.

• The need for labels to be applied in the course of normal packaging.

• An expectation that the standby power target should remain at 3W.

• Concerns about the timeframe, which they would like to have a 3-year lead-in time.

They expect to be consulted further should such a MEPS scheme be proposed to be introduced

in New Zealand.

Summary − Recommended Policy Options for New Zealand

A MEPS for televisions in New Zealand should be implemented in tandem with Australia

which is now likely to implement a voluntary scheme. The MEPS should cover both onmode and standby energy consumption. Stage 1 should encourage the removal of the

worst performing 30% of sets at the retail level.

Any labelling scheme should be based on the six-star EU scheme, and developments

monitored with Australia.

Consultation with the importers and major retailers will be necessary to ensure that there is

no undue resistance to the scheme, to maximise compliance and adherence to the

principles of the scheme.

Page 27

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 31

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

12 Implementation Program

The Australian implementation program is show in Table 10

Table 10: Proposed Implementation Plan for Recommendations

Obviously if this program has been adhered to, New Zealand is somewhat behind, particularly

in becoming deeply involved in any standard making. Because New Zealand is more

responsive than Australia, some catch up may be possible, so that Items 7-12 could still be

achieved with no more than six months slippage. Full implementation could be achieved by the

end of 2006.

13 Summary and Conclusions

Televisions use around 320 GWh per year in energy, and the current stock of TVs is less

efficient than present day sets, being largely CRT-based. Newer LCD slimline sets can offer

reduced power consumption, but even within a particular set type there is a range of energy use

depending on the efficiency of the designs used, and the consumers’ preferences for the type of

set chosen.

The Australian Greenhouse Office has decided to introduce a voluntary MEPS and labelling

scheme for TVs for implementation by October 2006. This is designed to encourage the

removal of the worst performing 30% of sets presently being offered for sale on the retail

market. There are equivalent benefits for New Zealand in introducing a similar scheme, and

indeed implied obligations under the TTMRA to do so.

Page 28

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 32

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

The benefits to New Zealand would accrue in energy savings, and avoided carbon charges over

the next 20 years with net present values of:

• Energy Savings $8.3 million

• Carbon emissions saved $10.78 million

The costs of such a scheme would be largely funded by retailers and consumers, and could cost

$25,000 in administration per annum. The net present value of this at $525,000 is far less than

any savings achieved.

It would be possible to introduce such a scheme by the end of 2006 if decisions and

consultation begin as soon as possible.

WISE ANALYSIS LIMITED

Gerry Coates

MANAGING DIRECTOR

Direct dial: (04) 472 7621

Mobile: (021) 355 099

E-mail: gerry@wise-analysis.co.nz

Page 29

A study produced for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority by

Wise Analysis Ltd

Page 33

MEPS − Televisions April 2005

APPENDIX A − Potential Stakeholders

Stakeholders with an interest in the future development of Television regulations include

manufacturers/importers, government agencies, retailers and industry associations. A list of

potential stakeholders is provided below.

Importers/Manufacturers

Fujitsu

Grundig

Hitachi

Hyundai

JVC

LG Australia

Panasonic

Philips