Page 1

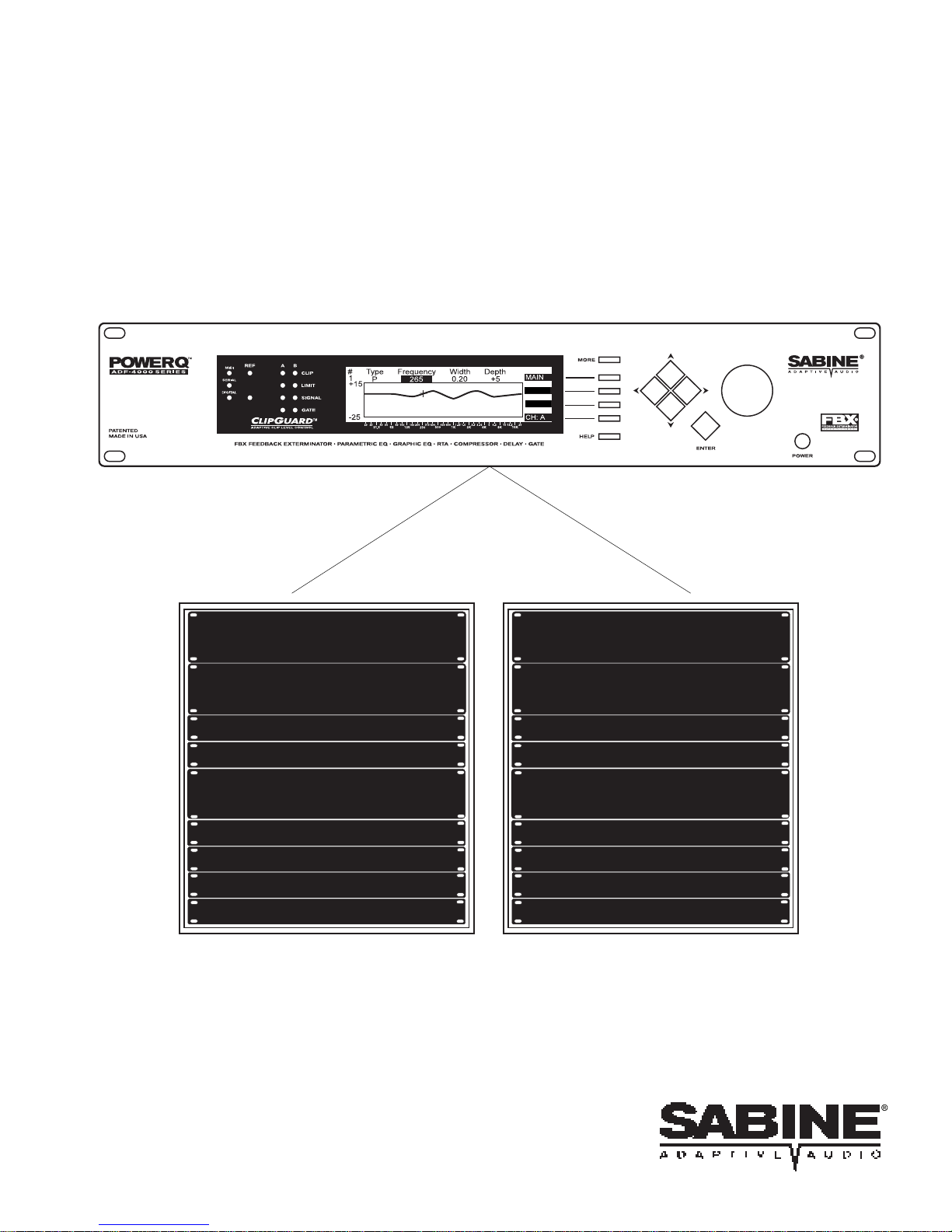

The two-channel POWER-Q gives you

two full racks of gear -- all in one!

CURVE

TURB -

Automatic Room Flattening EQ

Program Shaping EQ

FBX Feedback Exterminator

Parametric EQ

Real-Time Analyzer

Compressor/Limiter

Downward Expander/Gate

Digital Delay

Digital Delay

Program Memory

Automatic Room Flattening EQ

Program Shaping EQ

FBX Feedback Exterminator

Parametric EQ

Real-Time Analyzer

Compressor/Limiter

Downward Expander/Gate

Digital Delay

Digital Delay

Program Memory

Page 2

Table of Contents

1.0 Introduction..................................................................................................................4

2.0 Front and Back Panel Views and Controls...................................................................5

3.0 Block Diagram/Internal Signal Path .............................................................................6

4.0 Installation ...................................................................................................................7

5.0 Quick Start-up Reference ............................................................................................9

6.0 Overview and Philosophy ...........................................................................................10

7.0 Optimizing the Sound System and the Room with the POWER-Q: Five Steps ...........12

POWER-Q operating information

Background information

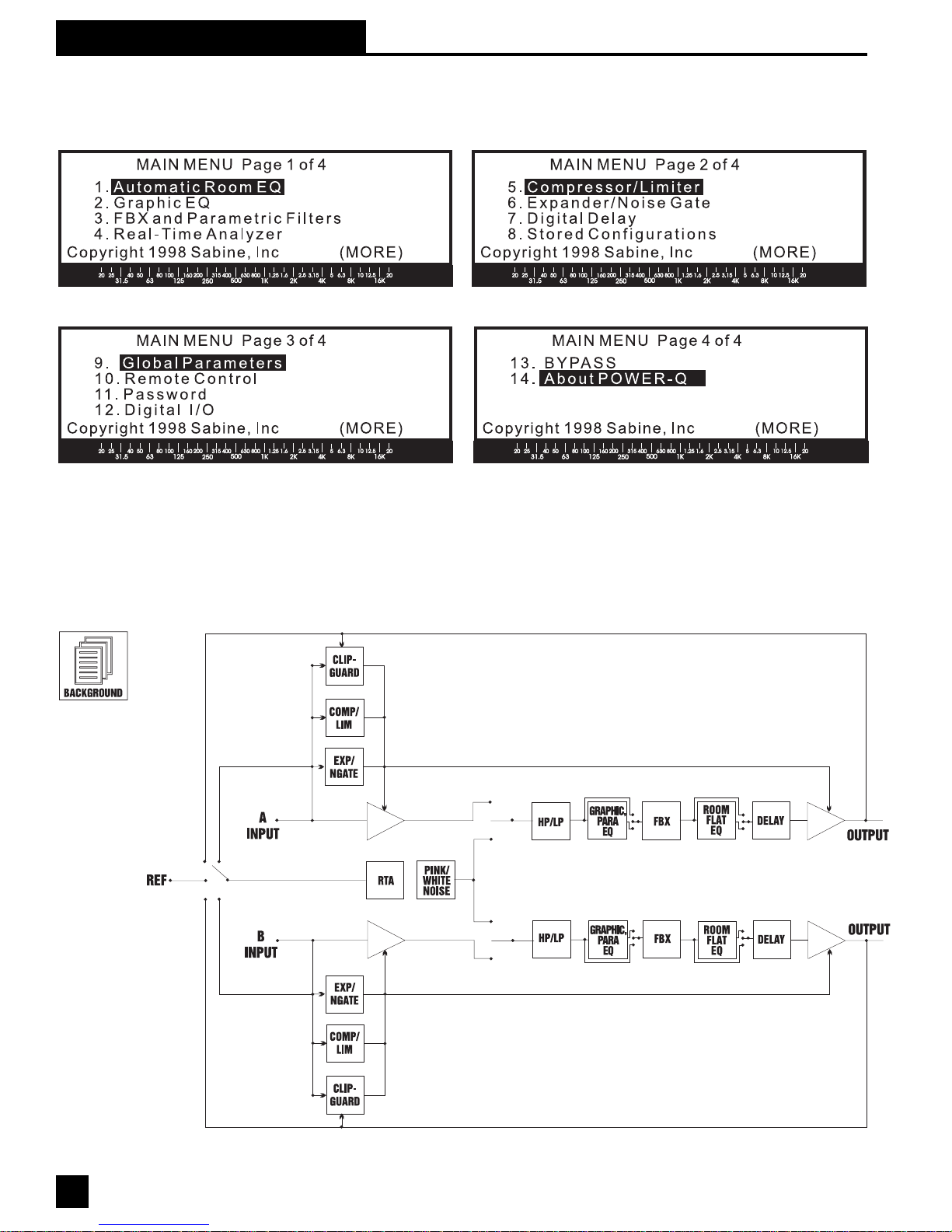

2.1 Main Menu windows (quick reference)

4.1 Where to install your POWER-Q in the sound system

4.2 Bypassing the POWER-Q

5.1 EQing an acoustic environment: Quick Instructions

5.2 Exterminating feedback: Quick instructions

6.1 Quest for loudness

6.2 Quest for clarity

7.1 Step One: The physical space

7.2 Step Two: Time alignment of speakers

7.3 Step Three: Setting the system and room to a “flat” response curve

7.4 Step Four: Tweaking the EQ

7.5 Step Five: FBX filters

8.0 Using the POWER-Q Digital Delay .............................................................................14

8.1 Digital delay applications and use

8.2 POWER-Q digital delay adjustments: Manual and automatic

9.0 Using the POWER-Q Automatic Room EQ ................................................................23

9.1 What is Automatic Room EQ?

9.2 How Automatic Room EQ works

9.3 Reference microphone choice

9.4 Reference microphone placement

9.5 POWER-Q controls for Automatic Room EQ

10.0 Using the POWER-Q Graphic Equalizer...................................................................29

10.1 Graphic equalizer applications

10.2 POWER-Q graphic EQ screens and options: Graphic EQ, Curve

Display , Reset Filters

1 1.0 Using the POWER-Q FBX/Parametric Equalizer ......................................................32

1 1.1 Types of filters: Fixed FBX, Dynamic FBX, and Parametric

1 1.2 FBX TURBO/Auto TURBO setup modes mode

11.3 POWER-Q FBX/parametric filter adjustments

1 1.4 Filter control menu: List Mode and Curve Mode

1 1.5 The “MORE” button for the FBX/parametric window

1 1.6 Preventing feedback in the event of equipment failure

12.0 Using the POWER-Q High and Low Pass Filters......................................................38

Page 3

13.0 Using the POWER-Q Real-Time Analyzer................................................................39

13.1 Using a real-time analyzer

13.2 POWER-Q RTA adjustments

13.3 Using the POWER-Q RTA and digital delay settings to minimize comb filters

13.4 Using the POWER-Q RTA during performance

14.0 Using the POWER-Q Compressor/Limiter................................................................42

14.1 Compressor/limiter applications and use

14.2 POWER-Q compressor/limiter adjustments

15.0 Using the POWER-Q Expander/Noise Gate.............................................................44

15.1 Expander/noise gate applications and use

15.2 POWER-Q expander/noise gate adjustments

16.0 Saving and Loading Stored Configurations...............................................................46

16.1 Recall and storage options and use

16.2 Saving EQ Settings: Room EQ and Program EQ

16.3 Using the POWER-Q stored configuration window

17.0 Global Parameters: Configuring Internal Default V alues..........................................48

18.0 Password.................................................................................................................50

19.0 POWER-Q Options ..................................................................................................51

20.0 Remote Control of the POWER-Q ............................................................................51

20.1 Computer Requirements

20.2 Installing SABINE POWER-Q Remote Software

20.3 Using SABINE POWER-Q Remote Software

20.4 POWER-Q Remote Software Guide

21.0 POWER-Q Digital I/O Option.......................................................................................60

22.0 Bypass Options

23.0 Using the ADF: A Pro’s Guide, with Ken Newman ....................................................62

24.0 Troubleshooting T ips ................................................................................................64

25.0 Engineering Specifications........................................................................................65

26.0 Cautions and Warranty .............................................................................................66

Operating Guide Version 8 -- for POWER-Q firmware v2.40

Special thanks to Hans Drobilitsch of Hans Drobilitsch Audio GmbH. (Austria) and

Andreas Schneider (Chief Sound Engineer, Austria Center V ienna) for their valuable

contributions to the design and implementation of the POWER-Q

.

Page 4

Section 1: Introduction

Section 1: Introduction

Congratulations and welcome to the new digital equalization and signal processing power of

the Sabine POWER-Q ADF-4000, two whole racks' worth of power in a single 2-U unit. Patch

the POWER-Q between the output of your mixer and the input to your crossover or power

amp, and you’re ready to harness the power of an arsenal of digital signal processing. (Note:

You can also use the POWER-Q in other configurations. See Section 4.1.)

The POWER-Q is truly remarkable because of its multi-tasking ability and ease of operation.

It's the latest breakthrough in the Sabine ADF Adaptive Digital Filter Workstation product line

and offers many of the features of the Sabine REAL-Q2 Real-Time Adaptive Equalizer - all in

one package.

The POWER-Q encompasses the following functions, all of which operate concurrently:

• Two separate, 2-channel, 31-band digital graphic equalizers

• Up to 12 additional filters per channel, configurable as any combination of:

• High and low-pass filters for each channel

• 2 channel fully adjustable compressor/limiter

• Full featured, filter-based RT A

• 2 channel digital delay for programmable time alignment of speakers by up to 83.2

mSec.

• 99 memory settings. Instant recall of all or selected parameters.

• Automatic Room EQ. Calibrate a system in any acoustic space to a flat response

curve automatically in just a few seconds.

• ClipGuard™ Adaptive Clip Level Control. This patented Sabine function

automatically prevents digital clipping and expands dynamic range to over 1 10dB.

• Optional remote control via RS-232 interface (for Windows™ computers)

• Optional Digital I/O: Allows user-selectable sample rate and input source.

• fully parametric filters

• fixed or dynamic automatic feedback control filters with Sabine’s patented

FBX Automatic Feedback Control technology

Y ou may quickly refer to the sections you need by scanning for the appropriate icons:

This manual is written to provide background information for implementing the POWER-Q’s

features in appropriate situations. These sections of the manual are denoted with the “BACKGROUND” icon.

Sections of the manual pertaining to operating the POWER-Q are indicated by the “HANDS

ON” icon.

Any information we think is essential is highlighted with an “IMPORTANT! READ THIS!” icon.

If you really can’t wait to get started using your POWER-Q immediately , refer to our “quick

start” section (Section 5). We do recommend you read the manual for a fuller understanding

and more complete utilization of the POWER-Q's features.

4

Page 5

Section 2: Front & Back Panel Views & Controls

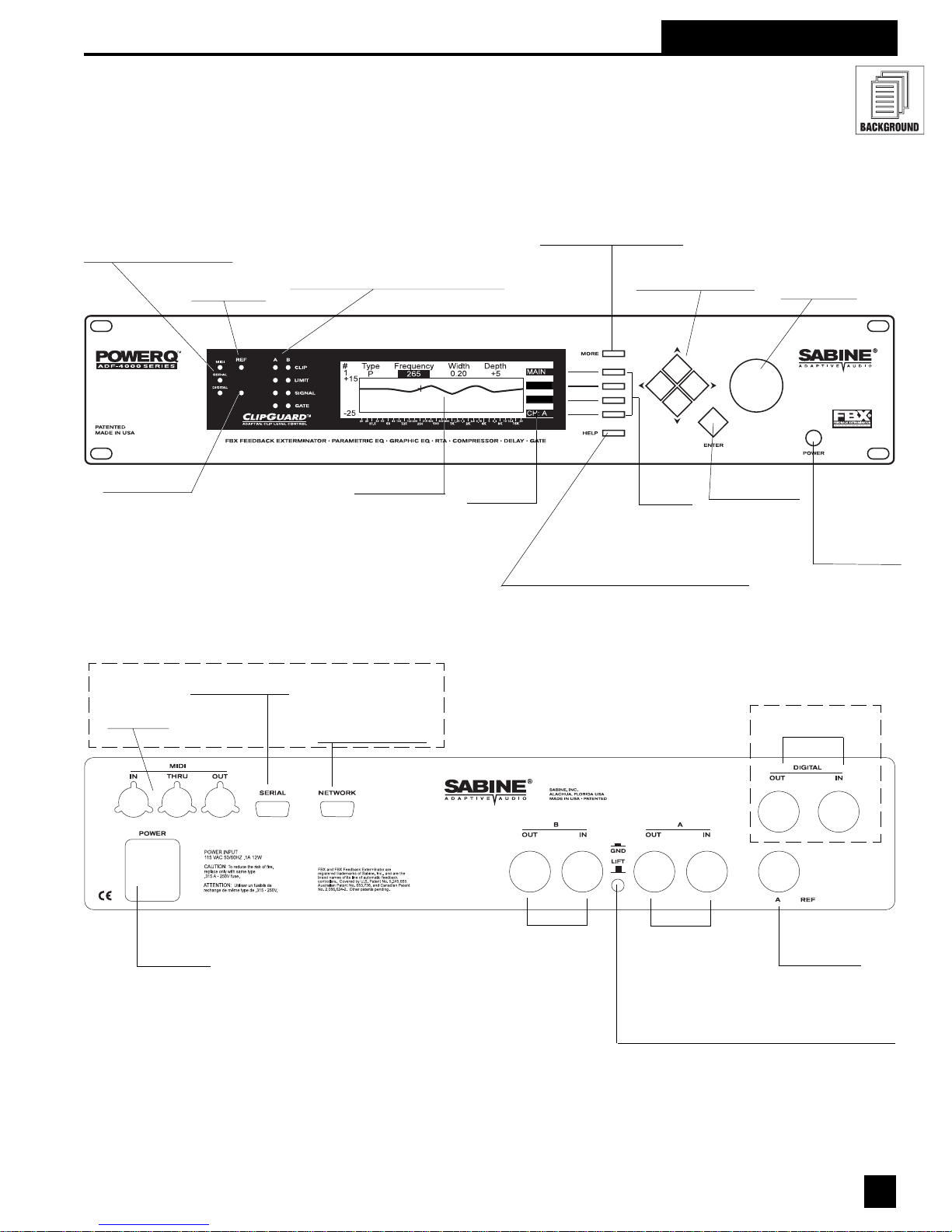

Fig. 1: POWER-Q Front Panel

Function Indicators for each channel

CLIP: CLIP LEVEL indicator lights when the input

Remote Control Indicators

MIDI: MIDI data

SERIAL: RS232 serial port data

DIGITAL: AES/EBU digital interface

*

Reference Mic

Clip Indicator

level is 3 dB below clipping level.

LIMIT: Indicates signal above limit or compressor

threshold.

SIGNAL:Lights when signal level is above -30 dBV

peak.

GATE: Indicates signal below gate or expander

threshold.

MORE Button chooses

additional POWER-Q menus

or soft key selections

CURVE

TURB -

Section 2: Controls

Up, Down, Left, Right

Cursor Movement Keys

Data Wheel

selects values

Reference Mic

Signal Indicator

Fig. 2: POWER-Q Back Panel

RS232 Remote

Control Connector

MIDI I/O

*

Connectors

Display Window

SERIAL REMOTE OPTION

RS232 POWER-Q

Network Connector

(for multiple POWER-Qs)

Soft Key

Menu Items

Soft Key

Selectors

Online Context-Sensitive HELP button

(When HELP screen is activated, "HELP" will

appear in lower right of display window. To escape

HELP screen, press HELP button again.)

ENTER Key

initiates action

Power On/Off

The POWER-Q will

automatically pass

signal through a

hard wire bypass

when the unit is

switched off.

DA-I/O OPTION

Digital Audio I/O

Connectors (XLR-3)

IEC-320/C14

AC Power

Connector

as of this publication, MIDI control of the POWER-Q is not yet implemented.

*

Channel B Input

and Output

(XLR-3)

Channel A Input

and Output (XLR-3)

Ground Lift Switch

(Differing ground potentials between or among interconnected

equipment racks may introduce hum or noise into the sound

system. The POWER-Q ground lift switch isolates the AC

ground from the chassis when in the extended position.)

Reference Mic

Input (XLR-3)

5

Page 6

Sections 2 & 3: Menus & Diagrams

2.1 MAIN MENU WINDOWS (QUICK REFERENCE)

Fig. 3: Main Menu Items

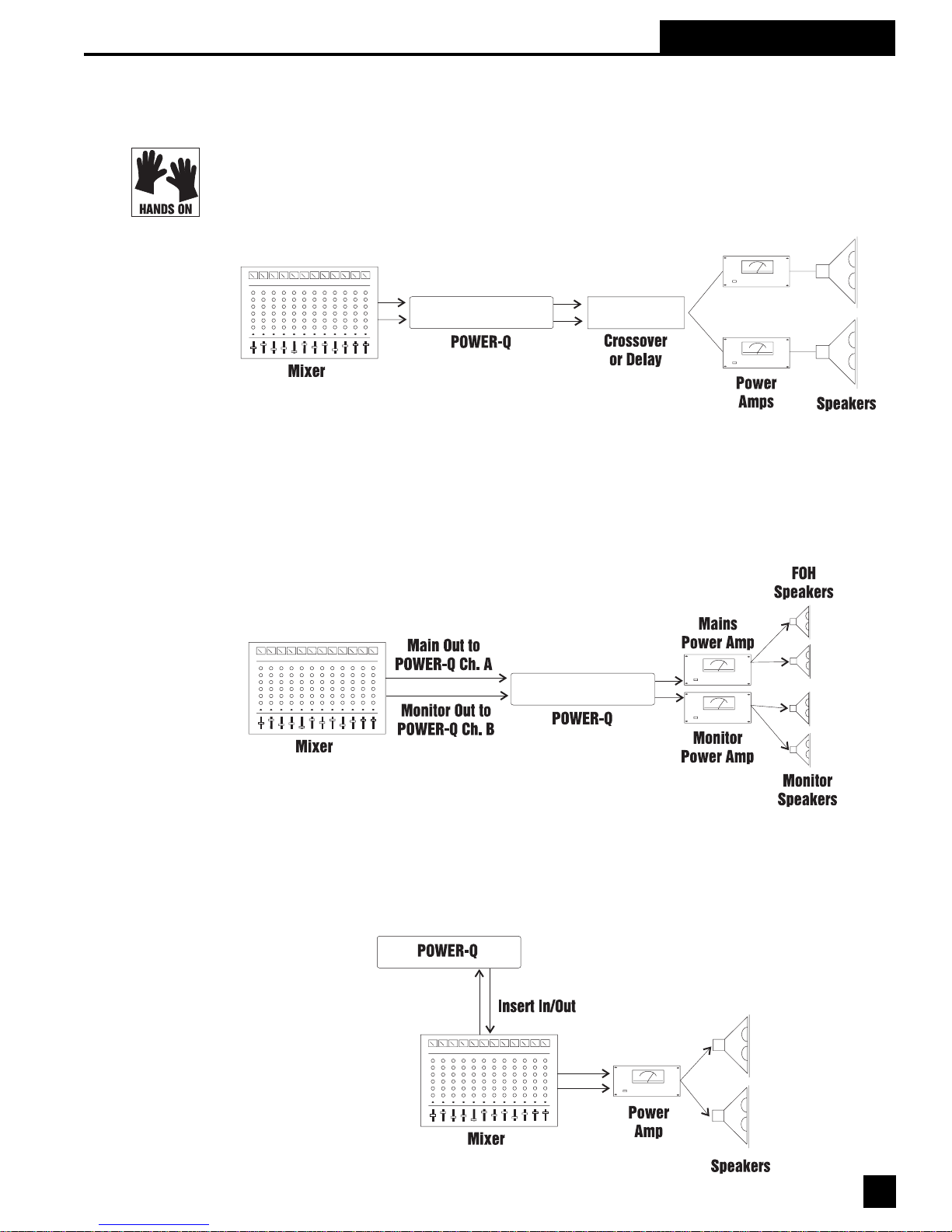

Section 3: Block Diagram/Internal Signal Path

Fig. 4: POWER-Q

Internal Signal

Path

6

Page 7

Section 4: Installation

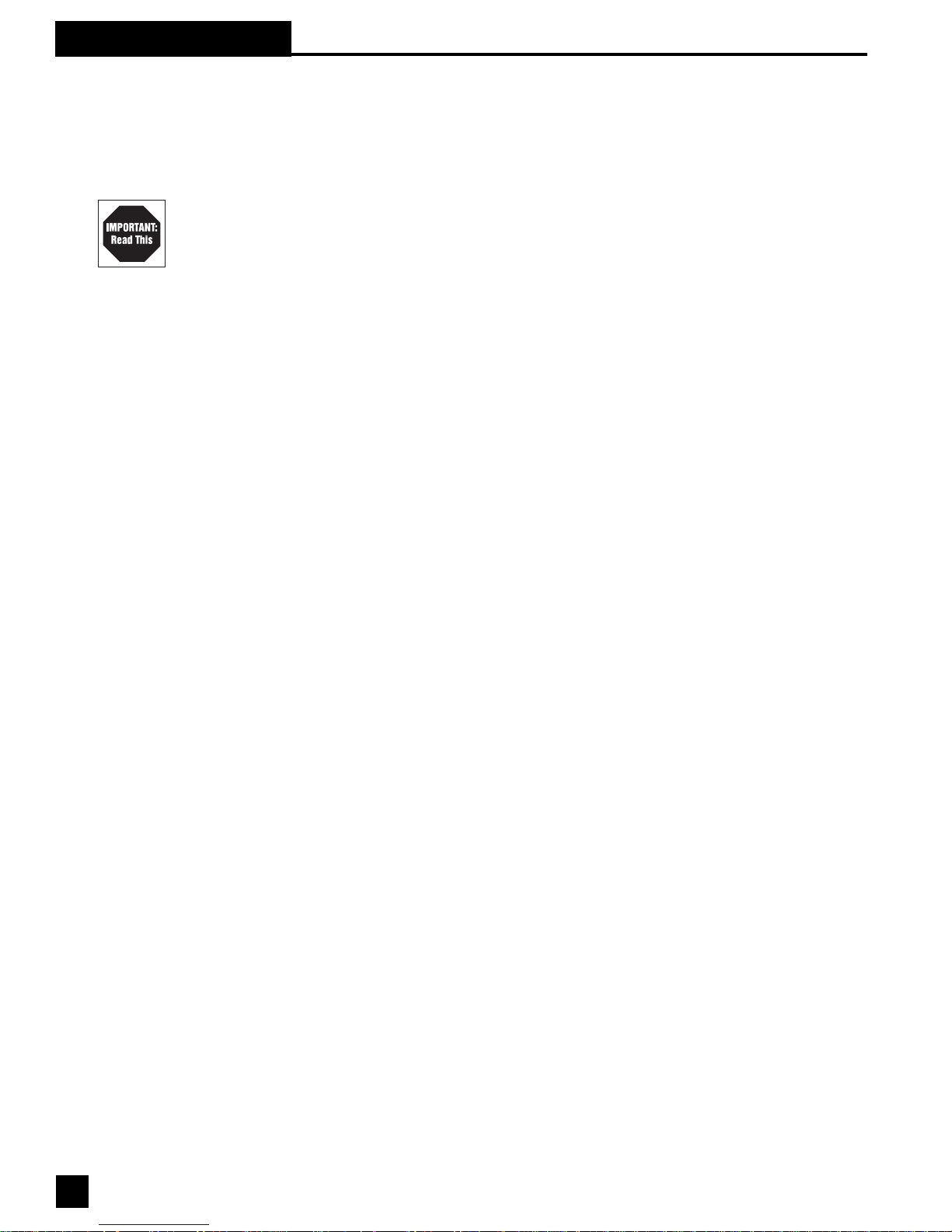

4.1 WHERE TO INSTALL YOUR POWER-Q IN THE SOUND SYSTEM. The most common placement of the

POWER-Q is between the output of a mixing console and the input to a power amplifier. If your

system requires a crossover or additional delays (such as the Sabine DQX-206), put the POWER-Q

in line after the mixer, but before those units. The configuration looks like this:

Fig. 5: Most common

setup

A variation of this setup might involve using the POWER-Q as a “dual mono” unit. Patch the main

output of your mixer into Channel A of the POWER-Q, and the monitor output into Channel B.

Then plug Channel A POWER-Q output into your main power amp, and Channel B POWER-Q

output into your monitor power amp. This will allow use of the POWER-Q as if it were two separate mono units. The configuration looks like this:

Section 4: Installation

Fig. 6: Using the

POWER-Q as a "dual

mono" unit

Fig. 7: Using the

POWER-Q at a mixer

insert point

The POWER-Q may also be used at a mixer insert point, either for a single input channel, or for a

group or bus insert point. This will dedicate all of the features of the POWER-Q to a pair of single

channel inputs on your mixer or to a subgroup of inputs (for example, all the drums in your mix).

The patching will look like this:

7

Page 8

Section 4: Installation

The reference microphone for the POWER-Q plugs in the back of the unit, into the jack labeled

“Ref A.” The “Ref B” jack is blank.

THE POWER-Q SHOULD NOT BE USED IN THE FOLLOWING CONFIGURATIONS:

·Do not plug a microphone directly into the channel A or B XLR input connections on the back

of the POWER-Q. These plugs are for balanced line level inputs, not microphones.

·Do not use the POWER-Q in an effects or auxiliary loop. Since such a patch is designed for

mixing processed (wet) and unprocessed (dry) signals together in a variable proportion, the

processing of the POWER-Q will be mixed with the unprocessed signal.

·Do not patch the output of any amplifier into any POWER-Q input. This will VOID your

warranty .

4.2 BYPASSING THE POWER-Q. The POWER-Q allows flexible options for bypassing all or part of its

internal processing. For more details please refer to Section 22.

A “quick bypass” can be accomplished simply by turning the unit off, which routes the input jack

directly to the output. However, please note two cautions when turning the POWER-Q on and/or

off:

1. If you turn the unit off, any suppressed feedback may suddenly reappear . As a precaution,

turn down the gain on your power amplifier.

2. When you turn the unit on, the unit will briefly be in bypass (for a few seconds) until the

processing is engaged. Suppressed feedback may occur during these few seconds. As a

precaution, keep your mixer and/or power amp turned down until the POWER-Q processing

engages.

8

Page 9

Section 5: Quick Start-Up Reference

If you want to get going in a hurry , first make sure your POWER-Q is correctly patched into your

system. There are two main tasks the POWER-Q will perform: equalizing the tonal balance of the

system and eliminating feedback.

5.1 EQing AN ACOUSTIC ENVIRONMENT: QUICK INSTRUCTIONS. There are three basic methods of equalizing a sound system with the POWER-Q: Automatic Room EQ, Real-Time Analysis, or by ear .

Automatic Room EQ. Make sure you have a reference mic positioned correctly and plugged

into “Ref A” on the back of the POWER-Q (very important for optimal results). Select #1 (“AUTOMA TIC ROOM EQ”) from the MAIN MENU. Follow the on-screen instructions. Your system will be

analyzed and the EQ adjustments in the POWER-Q will be made in 10 seconds per channel.

Real-Time Analysis. Alternatively, you may elect to play pink noise through your speakers and adjust the Graphic EQ to balance the frequency response. To do this, first make sure you

have a reference mic positioned correctly and plugged into “Ref A” on the back of the POWER-Q.

Then select #4 (“REAL-TIME ANAL YSIS”) from the MAIN MENU, press the “MORE” button and

turn on the pink noise independently for Channel A. Use the superimposed Graphic EQ sliders to

make additional adjustments. Repeat the procedure for Channel B.

Section 5: Start-Up

Equalizing By Ear. You won’t need to plug in a reference mic to EQ your system by ear.

Select soft key #2 (“GRAPHIC EQ”) from the MAIN MENU. This will display the graphic EQ

screen, one channel at a time (you may select which channel with a soft key). You may adjust

individual filters using a combination of left/right arrow keys and the data wheel.

In addition to or instead of the Graphic EQ, you may affect system equalization with the POWER-Q

parametric EQ. This is accessed by selecting MAIN MENU option #3, “FBX AND PARAMETRIC

FILTERS,” and playing an audio source through your sound system and the POWER-Q. Twelve

filters and a high and low pass filter are available for each channel. These filters are accessed using

the up/down arrow keys and can be set to parametric (“PARAM”) using the data wheel. The data

wheel and left/right arrows set the frequencies, filter widths, and filter depths of all filters. Any changes

made to the parametric filters will add to the overall EQ of the system, including graphic EQ settings.

5.2 EXTERMINATING FEEDBACK: QUICK INSTRUCTIONS.

1. Once your room is equalized to your liking (or you may elect not to equalize and proceed

directly to feedback control, though we don’t recommend this), set up your microphones and

acoustic instruments in the positions where they will be used.

2. If you are using your POWER-Q in a 2 channel system, turn the power amp to zero gain for one

channel. This will allow you to set FBX Filters for the other channel.

3. Set all other controls for your sound system at the settings that will be used for performance.

Select soft key #3 (“FBX AND P ARAMETRIC FILTERS”) from the MAIN MENU. The POWERQ defaults to seven fixed FBX, three dynamic FBX and two parametric filters, and has up to 12

total filters available for each channel. (This means that using parametric filters for room

equalization by changing these defaults reduces the number of FBX filters available for feedback control.)

4. Press the MORE button until you see “TURB-” on the screen. Press the adjacent soft key .

5. Highlight “Automatic Setup” with the arrow keys.

6. Raise the master gain of your mixer until feedback is just starting, then press ENTER on the

POWER-Q front panel.

7. The POWER-Q will automatically raise its output gain and set filters, until either all available

FBX filters are set, or until the first dynamic FBX filter is set. Then the POWER-Q will reduce

its output gain to its original level.

8. Repeat this procedure for the second channel, turning down the power amp for the channel just

filtered, and turning up the gain for the second channel.

(This is just one scenario for setting FBX filters. Please refer to Section 1 1 for additional details.)

9

Page 10

Section 6: Overview

Section 6: Overview & Philosophy

Live sound reinforcement can be a challenging business. Look what we have to deal with: The

guitar player turns up to 1 1 and still complains that she can’t hear herself. The podium speaker

points the mic at his sternum and mumbles, drowned out by the chatter of people eating dinner, in

a boxy hotel convention room. The rock singer asks for - no, DEMANDS - a monitor level loud

enough to hear over a drag race in a hurricane. The minister clips on the lavalier mic and wanders around while preaching, sometimes right past the speaker cabinet...

As an antidote to premature aging and undue stress, we at Sabine have dedicated ourselves to

simplifying the demands of live sound amplification by creating adaptive equipment that handles

some of the tedious (but important) mixing chores automatically . This allows sound engineers to

concentrate on making a mix sound good instead of dealing with acoustical problems!

The POWER-Q’s features are designed to help you achieve two important goals in sound reinforcement:

risk of sounding like a drill sergeant, let’s call this the desire to be LOUD and CLEAR.

6.1 QUEST FOR LOUDNESS. At least two bad things happen in the pursuit of loudness (putting aside

the deafness potential): feedback and lack of headroom.

getting more gain before feedback

, and

more clarity and definition in the sound

. At the

Let’s consider headroom first. The dynamic range of DSP is limited by the word length of an

individual datum: The more bits in a word, the greater the dynamic range. The POWER-Q offers

24 bit resolution and a dynamic range spec of >1 10 dB (with ClipGuard™). Plus, our ClipGuard™

Adaptive Clip Level Control system is designed to make it all but impossible for our units to clip

digitally; so if you’re hearing distortion in your system, it’s not likely coming from your POWER-Q,

because we’ve taken steps to prevent that. (Note: Make sure the FBX TURBO setup mode is off

before your program begins; see section 1 1.2.) Likewise, the compressor/limiter built into the

POWER-Q will raise the average gain level of your mix while protecting your speakers from hot

shot sound engineers whose goal in life is to explore the extremes of speaker cone flexion. All of

these functions are designed to maximize your gain without distortion.

Maximizing gain would be a far simpler matter if it weren’t for the problem created by adding gain

to a microphone in the presence of a speaker, which in turn reproduces the mic’ s sound, with the

mic in turn amplifying its own input, and so on. At some point, at least one frequency will regenerate. This is techno-speak for that dreadful ringing sound commonly known as feedback. The

nature and severity of the feedback will depend on the sound system and the acoustical environment, but feedback generally will occur before you reach the limits of your potential amplification.

This means that the most likely volume limitation of your sound system is not the power of your

amplifiers or the size of your speakers, but the threshold of feedback.

Enter the Sabine FBX. In the pre-FBX dark ages, feedback was often controlled by passing a mix

through a graphic equalizer and pulling out frequencies as close as possible to the ringing feedback. While this technique can reduce feedback, it also reduces the sound quality of the overall

mix. The one octave-wide filters of a third-octave equalizer (you read that right—the filters are

usually an octave wide, spaced on overlapping third-octave centers) are far too clumsy and

inaccurate to target feedback specifically . You don’t shoot a mosquito with a shotgun or do brain

surgery with hockey gloves. Shotguns, hockey gloves and graphic equalizers are valuable tools,

but only in the right applications. A graphic EQ is great to shape the overall sound of your mix

(and that’s why we’ve loaded your POWER-Q with two), but when you use it to control feedback

by pulling down EQ sliders, you’re also pulling out a big chunk of audio that is NOT feedback.

An FBX filter automatically detects feedback within a 1Hz resolution, places a tenth-octave wide

filter on it, and pulls down the level only as far as necessary to get rid of the feedback at a given

gain level. It is far more accurate in identifying and eliminating feedback and far less destructive

to your sound than even the best graphic equalizer. Plus it finds the feedback automatically in a

fraction of a second. You’d need to drink A LOT of coffee to react that quickly .

10

Page 11

Section 6: Overview

The POWER-Q provides up to 12 feedback filters per channel, thus allowing you to excel in your

quest for loudness without compromising your second, equally important goal: QUEST FOR

CLARITY.

6.2 QUEST FOR CLARITY. Clarity in the sound coming out of your speakers is a result of a myriad of

considerations: the quality of the components you’re using, the skill you and others demonstrate

in setting up and operating the system, and the all-important acoustic properties of the room in

which you’re operating your system.

Now, it’ s no secret that some architects skipped class the day of the 20 minute lecture on room

acoustics, which is why so many rock concerts take place in basketball arenas and live sound

people sport premature gray hair. Standing waves, flutter echoes, boominess...the list of problems is as big as a lead singer’s ego. (Our congratulations to those architects who DO pay

attention to room acoustics.)

The good news is that in addition to all the graphic, parametric, and FBX control in your POWER-Q,

you are also the proud possessor of a full-blown Real-Time Analyzer. Y ou can generate pink noise

to help determine the frequency response curve of the surrounding acoustic space and compensate

for its peaks and valleys with your EQ controls, while viewing a graphic display of the results in real

time.

If you’d rather use your time to set up mics, patch in the rest of your gear or take a break, the

POWER-Q Automatic Room EQ feature will analyze the room for you and optimize your system

EQ to the response curve you specify . At the next venue, you can do a quick room analysis (in

less than a minute), then you can recall the memory of all your other EQ settings and every other

parameter previously set on the POWER-Q. You’ll be done before the guitarist finishes tuning

(unless he uses a Sabine tuner, in which case it might be a tie).

You can also use the POWER-Q for clearer sound by time aligning speaker stacks with our built-in

digital delay . You can delay sound in one set of speakers by as much as 83.2 milliseconds (with

20 microsecond resolution) to allow sound to reach listeners’ ears at the same time. This improves the phase consistency of the program, greatly enhances intelligibility , and synchronizes the

perceived sound origination point so the directional cues from your ears match the visual cues

from your eyes.

In conclusion, the POWER-Q is your friendly rack of goodies conveniently condensed to a 2U box.

It will automatically align your speakers, tune your system to any room, automatically detect and

eliminate feedback before and DURING performance, compress your mix bus, and remember

your setup for a given artist or application. Sorry , it doesn’t make cof fee, but with everything the

POWER-Q does for you, you’ll have plenty of time to make it yourself.

11

Page 12

Section 7: Five Steps

Section 7: Optimizing The Sound System And The Room With

The POWER-Q: Five Steps

Remember, our quest is to amplify sound in a room to a desirable level without creating feedback

and distortion or sacrificing clarity. T o make the most of a sound system in a particular acoustical

environment, you will need to follow five simple steps:

1. Optimize the physical arrangement of your stage setup, speaker placement, and room

acoustics;

2. Time align your speaker stacks so that sound traveling from displaced speakers (and from

sound sources on stage) arrives at a designated reference position at the same time and/

or provides audio cues consistent with visuals;

3. “Flatten” the frequency response of your sound system in the acoustical environment so all

frequencies are heard in equal proportion at the reference position;

4. Adjust the equalization of the system to your personal preference or the requirements of a

particular application or performer (the POWER-Q will remember these settings and load

them from memory);

5. Apply FBX filters to live microphones to increase gain before feedback and insure maxi-

mum clarity , volume and microphone mobility.

The POWER-Q is amazingly useful for realizing steps 2 through 5 (see sections 8, 9, 10, 1 1, 12

and 13). Here are some suggestions for implementing all five steps.

7.1 STEP ONE: THE PHYSICAL SPACE. Unfortunately, the POWER-Q cannot physically rearrange your

stage setup or dampen reflective surfaces in your room. Y ou may not be able to build a bass trap

in a boomy room, find enough stage space to set the front-of-house speaker cabinets far enough

in front of the mic line to avoid howling feedback, or convince a night club owner to carpet the

dance floor. Ideally, a room with nonparallel, non-reflective surfaces that is large enough to

accommodate a full wave length (30 feet+) low bass frequency will provide you with fewer resonance points, a more evenly balanced room curve and less feedback. This acoustic ideal is

seldom found in the real world, so you should make the best of the situation with careful speaker

and microphone placement. To go beyond the limitations inherent in a less-than-desirable acoustical space, you’ll have to call in the artillery (electronics and equalization) to optimize your sound

system. This is why a device like the POWER-Q is worth every cent (and then some) of its very

reasonable price.

7.2 STEP TWO: TIME ALIGNMENT OF SPEAKERS. Compared to light or electronic signals, sound

travels very slowly . Sound traveling across a night club or concert hall, or from speakers at the

front of the stage to speakers half way to the back of the hall, is slow enough to often warrant

speaker time alignment with a digital delay . The sound emanating from a speaker farther away

from the listener is delayed relative to speakers close to the listener. The sound traveling to the

listeners’ ears from stage speakers takes longer to get there than the sound from the closer

speakers because most of the path for the latter is electrical. The correction is designed to allow

the sound from both sets of speakers to arrive at the listening position at the same time. (Obviously , in a situation where there is only a left and right front of house speaker stack, time alignment may be less of an issue. See Section 8 for a full discussion of these issues.)

The POWER-Q allows you to delay each output by up to 83.2 milliseconds. The delay time for each

channel can be set independently. For more details about setting the delay in your POWER-Q

output, refer to section 8.2. For more demanding delay applications involving up to six separate

outputs, automatic calculation of delay times and air temperature compensation, use the Sabine

DQX-206 delay/equalizer/limiter.

7.3 STEP THREE: SETTING THE SYSTEM AND THE ROOM TO A FLAT RESPONSE CURVE. Once the system

is in place and the speakers are time aligned, you are ready to even out (make equal, or “equalize”) the frequency response of the system in the room. This typically is done with broad filters,

such as the octave-wide filters of a 31-band graphic equalizer. Graphic EQ filters are spaced on

12

Page 13

Section 7: Five Steps

third-octave centers, but are typically an octave wide, overlapping across adjacent filter controls.

You can vary the width of the POWER-Q’s filters by accessing the “GLOBAL PARAMETERS”

option on the MAIN MENU (see Section 17).

The POWER-Q excels at the task of room equalization, offering both automatic and manual

frequency response adjustment. In the Automatic Room EQ mode (see section 9), a reference

microphone (with a reasonably flat frequency response) is placed at your choice of listening

positions in the acoustical environment. The POWER-Q automatically plays a short burst of pink

noise, and measures the energy across the audible spectrum as heard at the reference mic. The

POWER-Q then makes automatic adjustments to produce as flat a response as possible at the

reference position. Y ou can make additional EQ adjustments (parametric and/or graphic) after

Automatic Room EQ, to tweak your system response by ear. The entire Automatic Room EQ

process takes less than a minute for both channels of the POWER-Q.

Alternatively , you may choose to equalize your system by playing pink noise over the loudspeakers

and observing the REAL-TIME ANAL YSIS of the propagated energy across frequencies as heard

by the reference microphone (see Section 13). You must then manually adjust the equalization

faders of the POWER-Q’s graphic equalizer section to produce the desired frequency response.

Note that the POWER-Q allows you to see both your equalization faders and the RTA response

the same window,

while you make adjustments.

which spares you the cumbersome task of scrolling from one window to another

in

7.4 STEP FOUR: TWEAKING THE EQ. Once the room is flat, you may want to customize the room

equalization to meet your own personal tastes or to match the entertainers' performance style.

You may do this either by making further adjustments with a second graphic equalizer (see

Section 10) or by inserting up to 12 parametric filters per channel for very precise adjustment (see

Section 1 1). These filters can be added in list (tabular) form or drawn as a response curve using

the data wheel. Once you have room and system tweaked to your ideal, you can save and name

up to 99 settings for future quick recall (Section 16).

7.5 STEP FIVE: FBX FILTERS. In live sound reinforcement, the true limitation for system loudness is

not usually the wattage of the amplifiers, the headroom of the mixer or the power handling maximum of the speakers. Before the system clips, you will almost certainly encounter feedback. And

for eliminating feedback, there is no better system than the Sabine FBX Feedback Exterminator.

Once the sound system is properly equalized, the narrow filters of the FBX will go a long way

towards increasing loudness without feedback. Placing the FBX filters in line WITHOUT first

using a graphic equalizer to reduce broad resonant room frequencies may produce several narrow

FBX filters clustered together closely at a point. This means you will quickly exhaust available FBX

filters trying to do a job better suited to a wider filter (i.e., a graphic EQ fader), you’ll reduce the

amount of potential increased loudness, and you won't get the maximum benefit of FBX.

The POWER-Q is the most complete system on the market that allows this much control over the

steps to maximize clarity and gain in any acoustical environment, using any sound system.

13

Page 14

Section 8: Digital Delay

Section 8: Using the POWER-Q Digital Delay

8.1 DIGITAL DELAY APPLICATIONS AND USE. This section goes beyond the typical operating guide that

only explains the front and back panel adjustments of a piece of equipment. Instead, we discuss

the basic acoustical concepts needed to get the most out of the use of digital delay in sound

systems. If you are familiar with these principles, feel free to skip ahead. Some principles may

require additional delay channels and options available with the Sabine DQX-206.

Why Digital Delays? The most intelligible sound occurs when two people speak face to face.

The sound is loud and dry , and the direction of the sound aligns with the speaker. The most

intelligible sound systems are the ones that come closest to emulating face to face communication. If this is your goal, a digital delay is essential to your sound system.

There are three distinct applications for digital delays. The first and most important is synchroni-

zation of the loudspeakers to control excess reverberation and echo. Second, digital delays

help control comb filter distortion, and finally, digital delays are useful for aligning the acous-

tic image so the direction of the sound seems to be coming from the performer rather than from

the loudspeaker.

Loudspeaker Synchronization

Sound travels at about 1,130 feet per second in air, or about 1 foot per millisecond. On the other

hand, electronic signals travel almost one million times faster through your sound system to the

loudspeakers. The main task for digital delays is to synchronize multiple loudspeakers so the

sound traveling different distances arrives at the listener’s ears at about the same time. Synchronizing the loudspeakers reduces reverberation and echoes for improved intelligibility.

How to Synchronize Your Signals

There are several powerful tools available for precisely measuring the time a loudspeaker signal

takes to arrive at a certain point in the audience. Most of these tools are very sophisticated and

tend to be quite expensive. Fortunately, simpler tools are sufficient for most applications.

In the 1930’s, engineers synchronized the low and high frequency speakers in movie theaters by

feeding a sharp click through the system. They moved the speakers until they could only hear a

single sharp click coming from both speakers. You can use this same method with a common

child’s toy called a clicker. Pressing the thin metal strip makes a loud sharp click. A clicker is

especially useful when synchronizing the direct sound from the performer with the sound from the

loudspeakers.

Alternatively, you can use a phase checker especially for synchronizing the signals of two loudspeakers (either LF and HF or two full range systems) since most of the phase checkers include a

click generator and receiver. Phase checkers are quite affordable and have other uses besides

synchronization.

Processing (or Group) Delays

Converting signals back and forth from the analog to digital domain always delays the signal a

little. These conversion delays are often called processing (or group) delays, and usually range

between 0.9 and 5 milliseconds. You will notice that Sabine delays always display the processing

delay as the smallest possible delay value. For the POWER-Q, the processing delay is 1.38

milliseconds. You can bypass the unit for 0 seconds delay.

Not all manufacturers acknowledge processing delays in their specifications, but you

them into account when synchronizing your system. Make sure all digital equipment is on and not

bypassed when synchronizing. Also, be careful to make an appropriate adjustment in your delay

lines if you later add any type of digital equipment to the system.

14

must

take

Page 15

Section 8: Digital Delay

Center Cluster Speakers

Center cluster speakers offer several advantages over systems that have speakers mounted on

the sides. The most obvious advantage is that the distance to the closest and most distant

locations in the audience is often almost equal, so most listeners hear about the same level.

Center clusters also offer two other advantages regarding visual imaging.

Studies have shown that people can detect even small horizontal changes in the direction of a

sound source, but vertical shifts are much less noticeable. This suggests that the sound from

center-cluster speakers is more likely to be visually aligned with the performer than loudspeakers

placed on each side of the stage.

All those in the audience who are closer to the performer than the center cluster will hear the

direct sound from the performer before they hear the sound from the loudspeakers. This makes

the sound seem to come from the performer, not the loudspeakers. (See the Precedence Effect

below.)

Comb Filter Distortion

Many who took high school science may remember ripple tank experiments where waves are

generated from two separate point sources. The waves from each source combine to form visible

interference patterns. In some places the wave crests and troughs are in phase so they combined

to make a larger wave. In other places the crests are out of phase, so the crest of one wave

source is canceled by the trough of the other. Ripple tank experiments show the interference

patterns are strongest when the amplitudes of the waves from each source are equal.

A similar interference occurs in sound systems when a signal is delayed and mixed back into the

original signal. These interference patterns are called COMB FILTERS because their frequency

response plots look like the teeth of a comb (see Figs. 8 & 9). There are a number of common

situations that cause comb filters. For example, when the program is played through two loudspeakers, the loudspeaker that is farther away interferes with the closer loudspeaker. Comb

filters are also created when a performer is picked up by two microphones, one closer than the

other. You even introduce comb filters by mixing digital effects back into the “dry” signal at the

mixer’s effects loop.

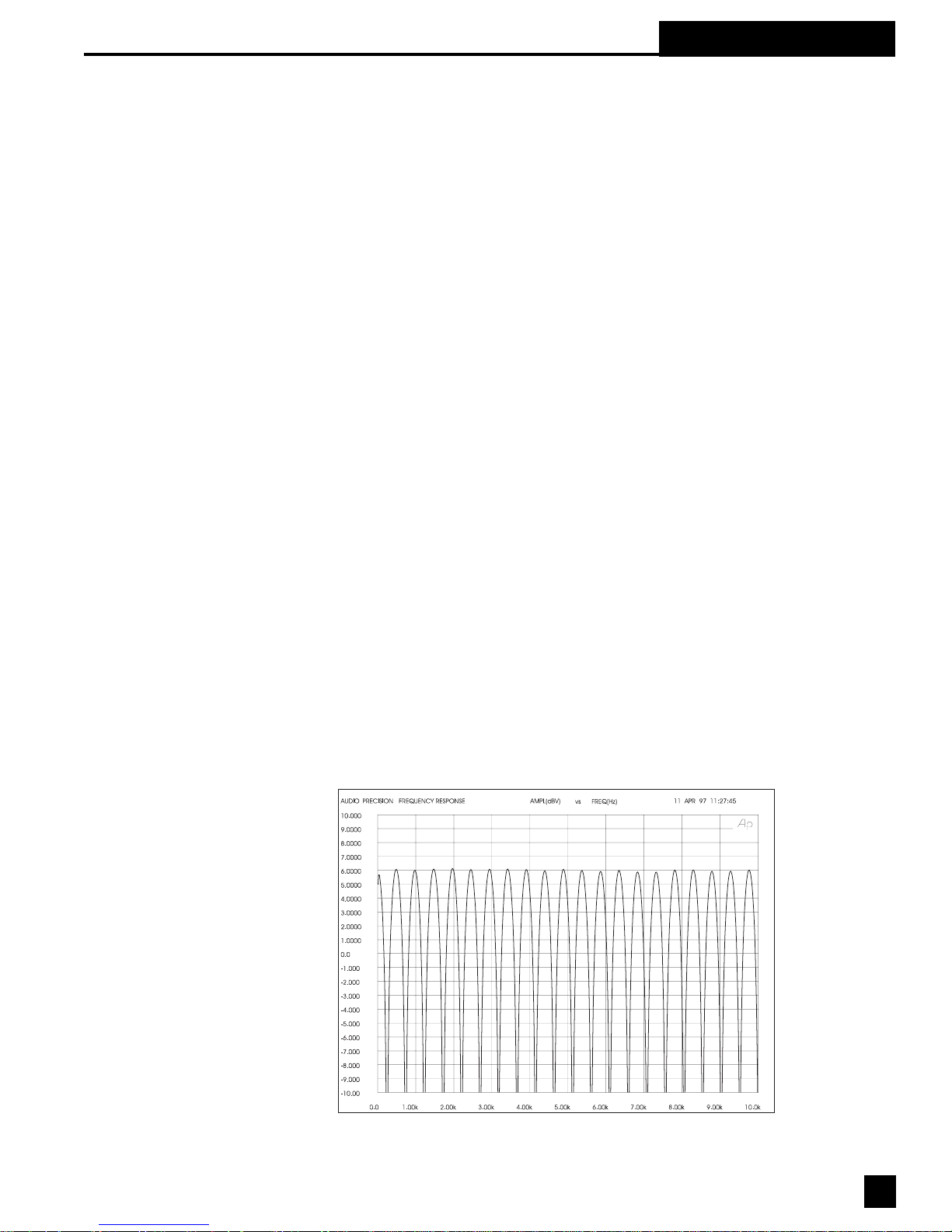

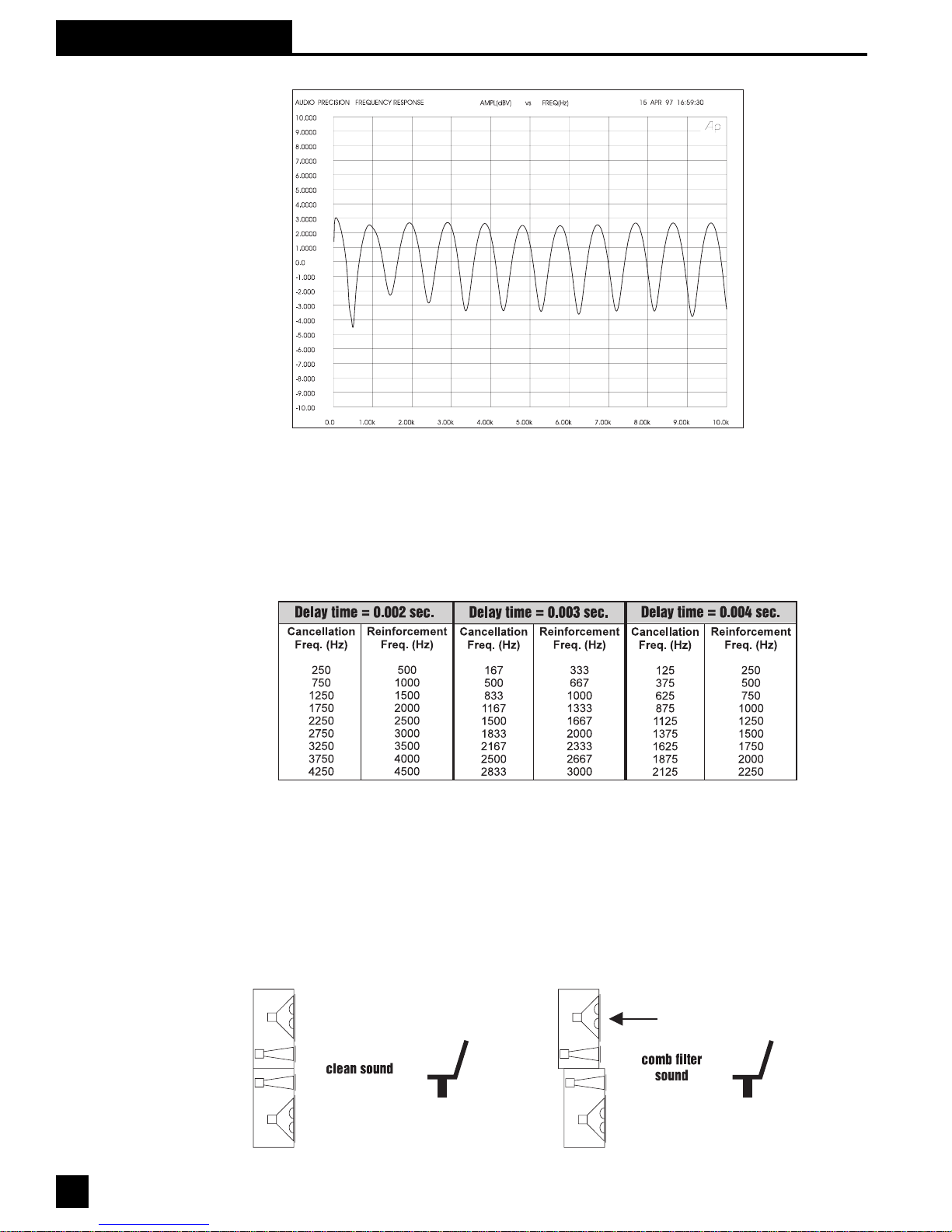

Fig. 8: COMB FILTERS. Input

signal mixed with a 2 msec.

delayed signal. (Both signals

have the same amplitude.

Max. filter gain is +6dB, and

max. depth is -4.)

15

Page 16

Section 8: Digital Delay

Fig. 9: COMB FILTERS. Input

signal mixed with a 2 msec.

delayed signal. (Delayed

signal has 10dB less amplitude. Max. filter gain is

+2.5dB, and max. depth is -3.)

Reducing the amplitude of the

delayed signal reduces the

comb filters' effect.

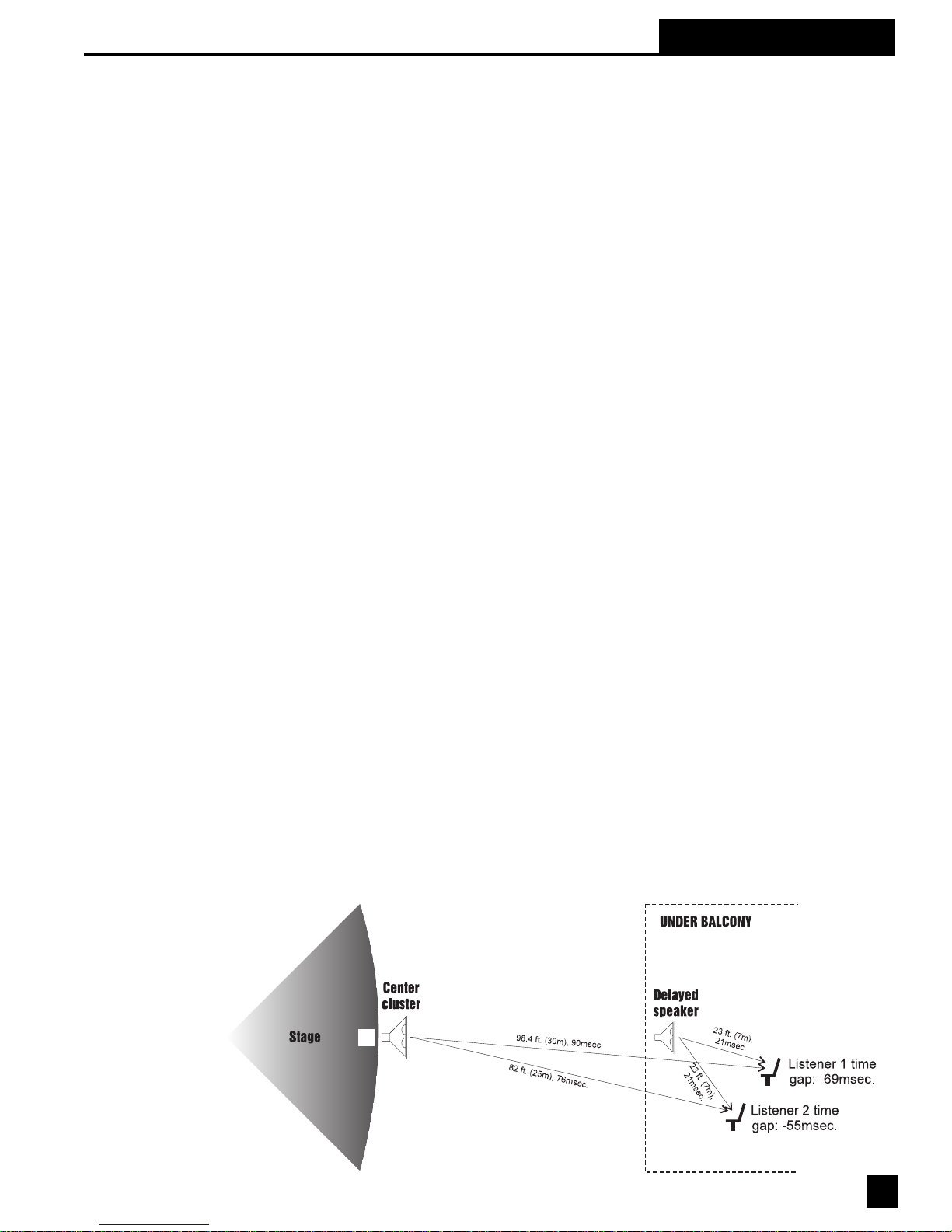

Calculating Comb Filter Frequencies

The frequencies of the reinforcements and cancellations depend on the delay time (the time

difference between the arrival time of the original signal and the delayed signal). The frequency of

the first cancellation occurs at 1/(2t) Hz, where t = the delay time in seconds. The cancellations

are separated by (1/ t) Hz. Fig. 11 shows how the comb filters change with the delay time.

Fig. 10: Comb filters get closer

as delay time increases.

Comb Filter Amplitude

If the original signal and the delayed signal are the same amplitude, the reinforced frequencies

increase in amplitude by 6 dB, while the out-of-phase frequencies cancel completely to -4 dB.

Comb filters cause a lot of problems. The frequencies that are reinforced are prone to excite

feedback, while the out-of-phase cancellations make the program sound thin and over equalized.

Try this simple experiment to hear what comb filters do to your sound.

Fig. 11: Comb filters noticeably affect your sound.

16

Page 17

Section 8: Digital Delay

Stack two identical full-range loudspeakers as shown in Fig. 12. Carefully align the HF horns and

wire the speakers in mono. Stand in front while listening to your favorite full-spectrum CD. Ask a

friend to move the top speaker slowly away from you. The degradation in sound quality you hear

is caused by comb filters. The experiment is most dramatic when you use good quality speakers.

Correcting Comb Filters

Comb filters are inevitable to some degree in every live sound system, and they cannot be

corrected with equalization. Fortunately, most comb filter problems can be reduced to a

minimum by synchronizing the signals and reducing the amplitude of the delayed signal. The

examples below show several practical applications.

The Precedence Effect: Aligning the Acoustic Image

Helmut Haas published a study in 1951 describing a series of experiments that demonstrated how

people perceive delayed signals and echoes. In his experiments, a listener was positioned

between two speakers placed 3 meters away; one was placed 45 degrees to the right and the

other was placed 45 degrees to the left. When the same program was played through both

speakers simultaneously, the listener perceived the acoustic image (the direction from which the

sound seemed to be coming) centered between the speakers.

When Haas delayed the signal going to one of the speakers by somewhere between 5 to 35

milliseconds, the listener perceived a shift in the acoustic image to the speaker heard first. While

the delayed speaker did not contribute to the apparent direction of the sound, it did make the

program seem louder and “fuller.”

Haas showed that you must increase the loudness of the delayed signal by about 8 to 10 dB

(twice the perceived loudness) in order for the acoustic image to move back to the original center

position. Increasing the loudness more than this, or increasing the delay somewhat more than 35

milliseconds, makes the delayed signal sound like an echo.

The phenomenon describing how the acoustic image follows the signal we hear first is called the

Precedence Effect. The phenomenon that makes two distinct sounds heard less than 35 msec.

apart seem like only one sound is call the Haas Effect. However, the terms are often used

interchangeably in the sound industry.

THREE APPLICATIONS FOR DIGITAL DELAYS

APPLICATION I: Under-The-Balcony Speakers

Fig. 12: Overhead view of

under-balcony application.

17

Page 18

Section 8: Digital Delay

Fig. 12 shows a typical situation where the performer is amplified by a center cluster hanging

above the stage. Almost everybody in the audience will enjoy good sound, except those seated in

the shadow of the balcony. So we add an under-balcony speaker to fill in the shadow.

Now we have sufficient volume under the balcony, but the sound from the two speakers arrives at

the listener’s ears some 55 to 69 milliseconds apart. The two signals, along with their echoes,

result in an unintelligible cacophony. We must delay the sound from the under-balcony speaker to

synchronize the signals. Do we set the POWER-Q delay to 55 or 69 milliseconds? Obviously, the

geometry will not allow us to exactly synchronize every location under the balcony; we have to

compromise.

First, consider the program type. For spoken word programs, you will produce the best intelligibility if the signals from the under-balcony speakers arrive within 10 msec. of the signals from the

center cluster. Therefore we should set the delay to 65-69 msec. You can allow a little more

reverberation for programs that are mostly music.

Next, we must eliminate comb filter distortion. Find the axis where the levels of the center cluster

and under-balcony speaker are equal. (See "Comb Filter Distortion," p.15.) You can use the

POWER-Q to precisely synchronize the speakers along this axis to eliminate the most severe

comb filters. Comb filters off the equal-level axis are much less of a problem since a louder signal

is not affected very much by a weaker signal.

Finally, you can experiment with adding 5 to 10 milliseconds delay to both sets of speakers to

enhance the Precedence Effect for the audience seated near the performer.

In the final analysis, every setting is a compromise, and your ear has to be the final judge. Check

the sound in several different locations throughout the auditorium and correct the most severe

irregularities.

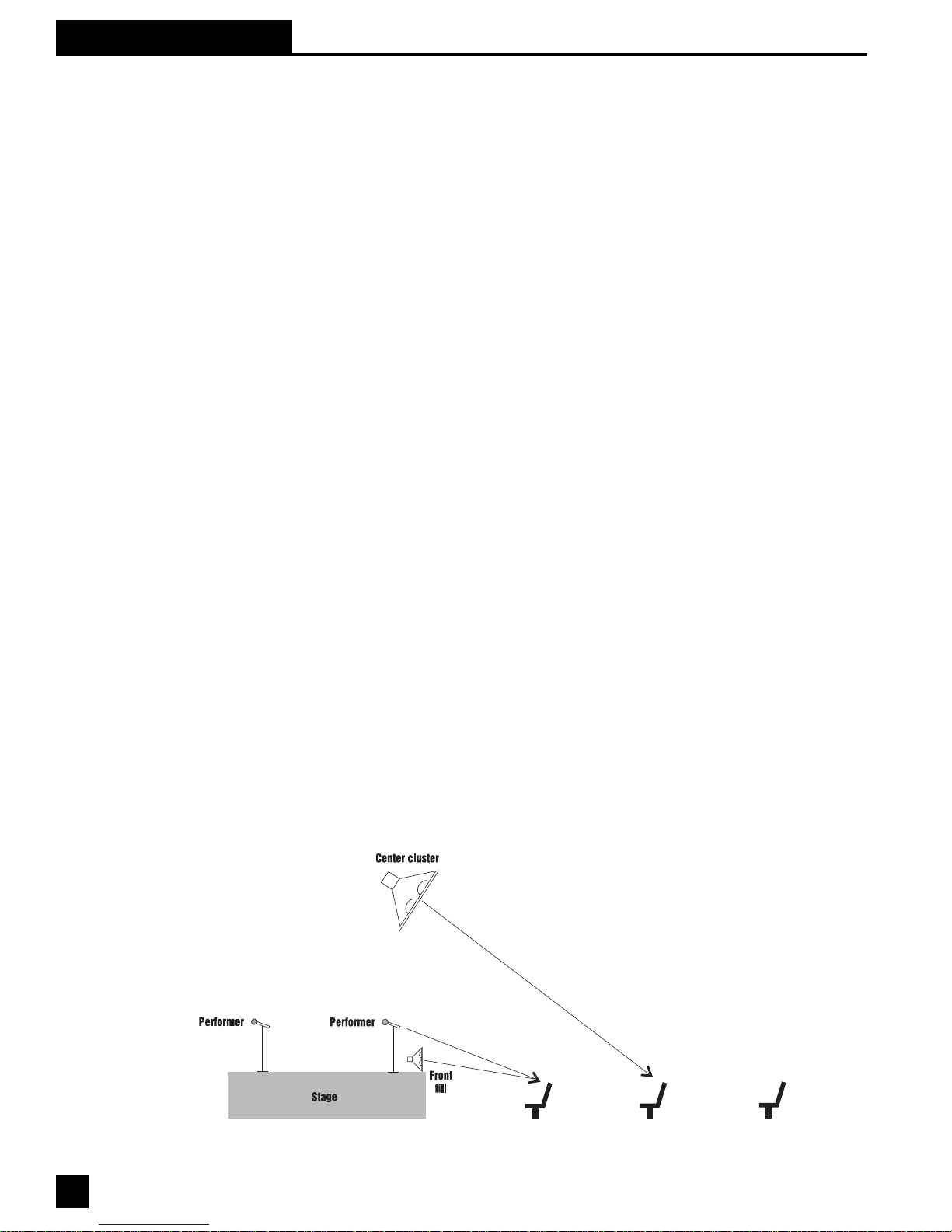

Application II: Center Cluster with Front Fills

Fig. 13 below describes a typical application that has a stage with a microphone, a center cluster

above the stage, and front fills in front of the stage. There must be thousands of installations

throughout the world like this that "get by" without digital delays. But with the POWER-Q, you can

improve the intelligibility and add a new quality without ringing up any significant costs. Use the

POWER-Q in this situation to align the visual image with the acoustic image. The program is

much more enjoyable when the amplified sound seems to be originating with the performer, not

the loudspeakers.

Fig. 13: Synchronizing center

clusters and front fills.

18

Page 19

Section 8: Digital Delay

Find a central place in the audience where the center cluster is 6 to 8 dB louder than the direct

sound from the performer. Delay them so that their sound arrives 5 to 8 milliseconds after the

direct sound from the performer. Experiment by bypassing the POWER-Q in and out to hear how

the source of the sound seems to move from the loudspeakers to the performer and back. Now

your ears have the same directional information as your eyes, so the performance will sound more

natural and exciting. The best seats in the house just got better.

What about the front fills? Their purpose is to add intelligibility and listening comfort to the first few

rows nearest the stage by filling in the areas missed by the center clusters. Add about 8 msec. to

the front fills to take advantage of the Precedence Effect.

The 8 msec. setting presumes the performer is standing on the front few feet of the stage. But

some stages are well over 30 feet deep. What if there is a second performer standing 25 feet

behind the first? The direct sound from his or her voice will reach the first few rows about 25

msec. after the first performer's. The audience will perceive the first performer directly and the

second performer through the loudspeakers.

We can add the advantage of the Precedence Effect to the second performer by placing the

POWER-Q in the mixer's channel insert point and adding a 25 msec. delay.

Certainly taking advantage of the Precedence Effect is not as obvious to the audience as eliminating feedback, but it is nice to know you did all that is possible to make the performance enjoyable.

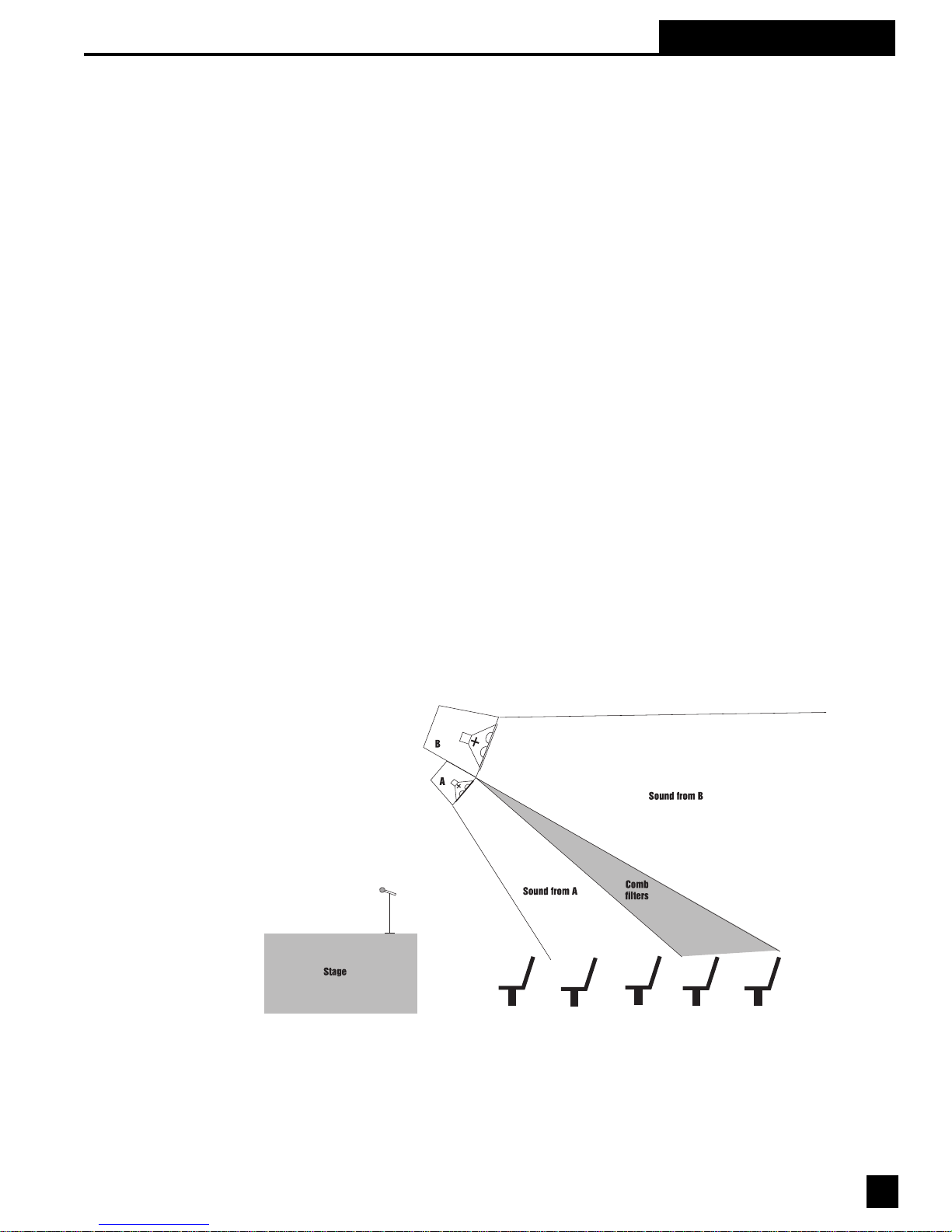

Application III: Synchronizing the signals of a far-throw and short-throw loudspeaker.

In order to reach the proper coverage in larger venues, we often stack two full range speakers - a

short-throw center cluster for the audience below and a far-throw speaker for the back of the

auditorium. It is almost impossible to perfectly align the stacked speakers mechanically, so comb

filter distortion becomes a problem in the area where the levels from both speakers are equal.

The same thing happens with speakers mounted on the right and left sides.

Fig. 14: Aligning far- and

short-throw speakers. (The

level from both speakers is

equal.)

It is impossible to remove comb filters with equalization, but the POWER-Q eliminates them in

short order without affecting the spectral balance for the rest of the audience. Find the axis where

the levels from the two speakers are equal. This is where the comb filters are most severe.

Carefully adjust the POWER-Q so that the signal from both speakers arrives at precisely the same

time. The POWER-Q provides 20 microsecond resolution for this purpose.

Use the same procedure to align speakers within a cluster when necessary .

19

Page 20

Section 8: Digital Delay

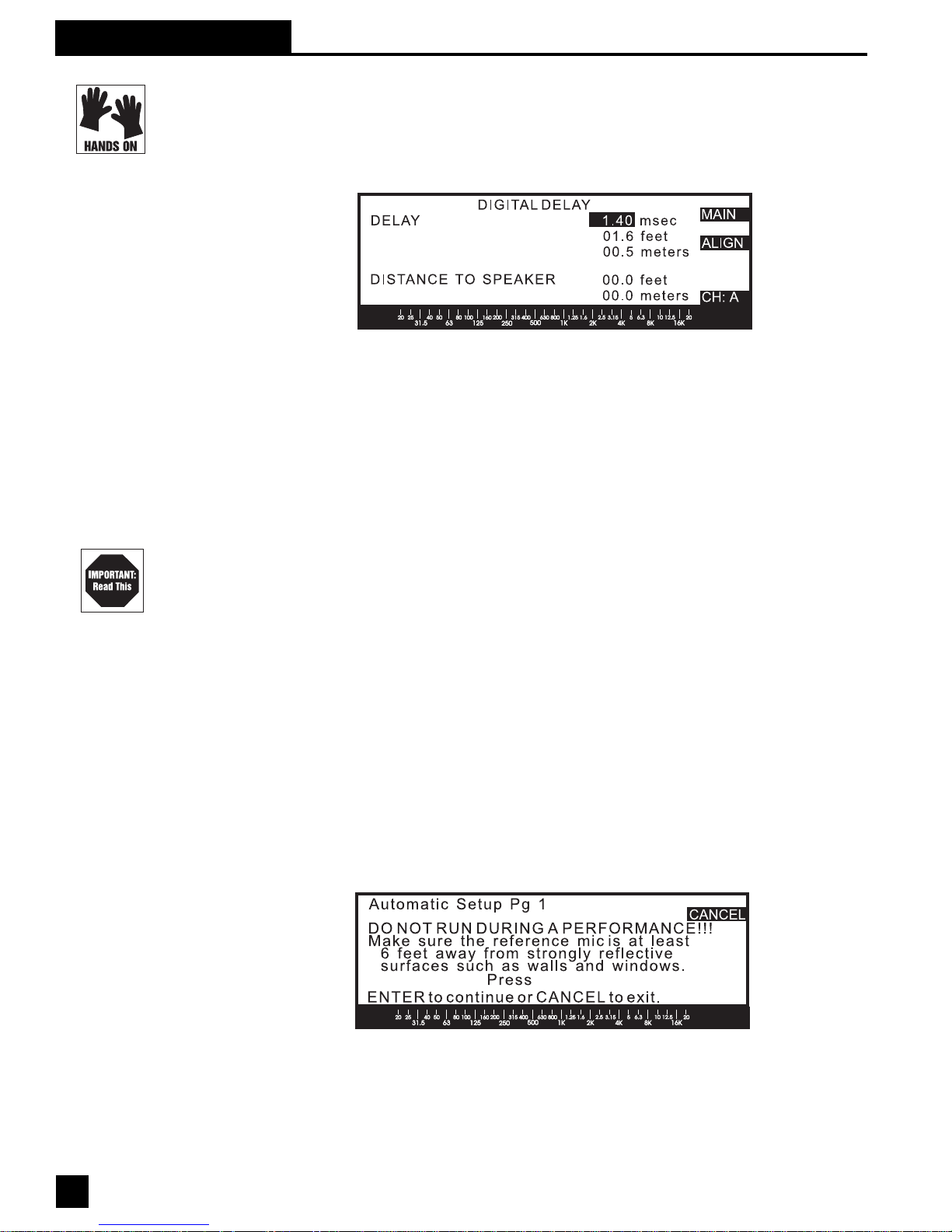

8.2 POWER-Q DIGITAL DELAY ADJUSTMENTS: Manual & Automatic. To access the POWER-Q digital

delay controls, choose #7 (“DIGIT AL DELAY” from the MAIN MENU. Use the up and down arrow

keys to scroll the MAIN MENU screen, and the soft key or ENTER key to select DIGITAL DELAY.

You will be presented with the following screen:

Fig. 15: Auto Delay page

You may set the delay time for channels A and B independently, either manually or automatically.

Manual adjustment. Delay time can be set in milliseconds, feet, or meters, with an adjustment

resolution of 20 microseconds (approximately 1 cm, or half an inch). Adjusting any one delay

parameter automatically changes the corresponding readout in the unselected measurement

units. The time unit display will always be the most accurate. (The distance displays are approximations based on the speed of sound at standard temperature and pressure conditions: 1 127 feet/

second at 20 degrees C and 760 mm Hg atmospheric pressure.) The minimum delay time

allowable is 1.38 milliseconds per channel; the maximum is 83.2 milliseconds.

Note that manually adjusting the digital delay during audio program may cause discontinuities

(popping sounds) while the adjustments are made. This is unavoidable and will cease when the

delay is set.

Delay times may also be set manually from inside the POWER-Q REAL-TIME ANAL YZER

window. Refer to Section 13.3 for more details.

Automatic Delay Alignment. If you have positioned a reference microphone for RTA analysis, or

Automatic Room EQ, the same microphone can be used by the POWER-Q to measure the

distance from the speaker to the microphone. (The qualities of the microphone are not an important consideration for delay alignment, although they are for EQ adjustments). The POWER-Q will

then set the delay times for its two channels to allow the sound from each speaker to reach the

microphone at the same time, compensating for the different distances from the mic to the two

speakers.

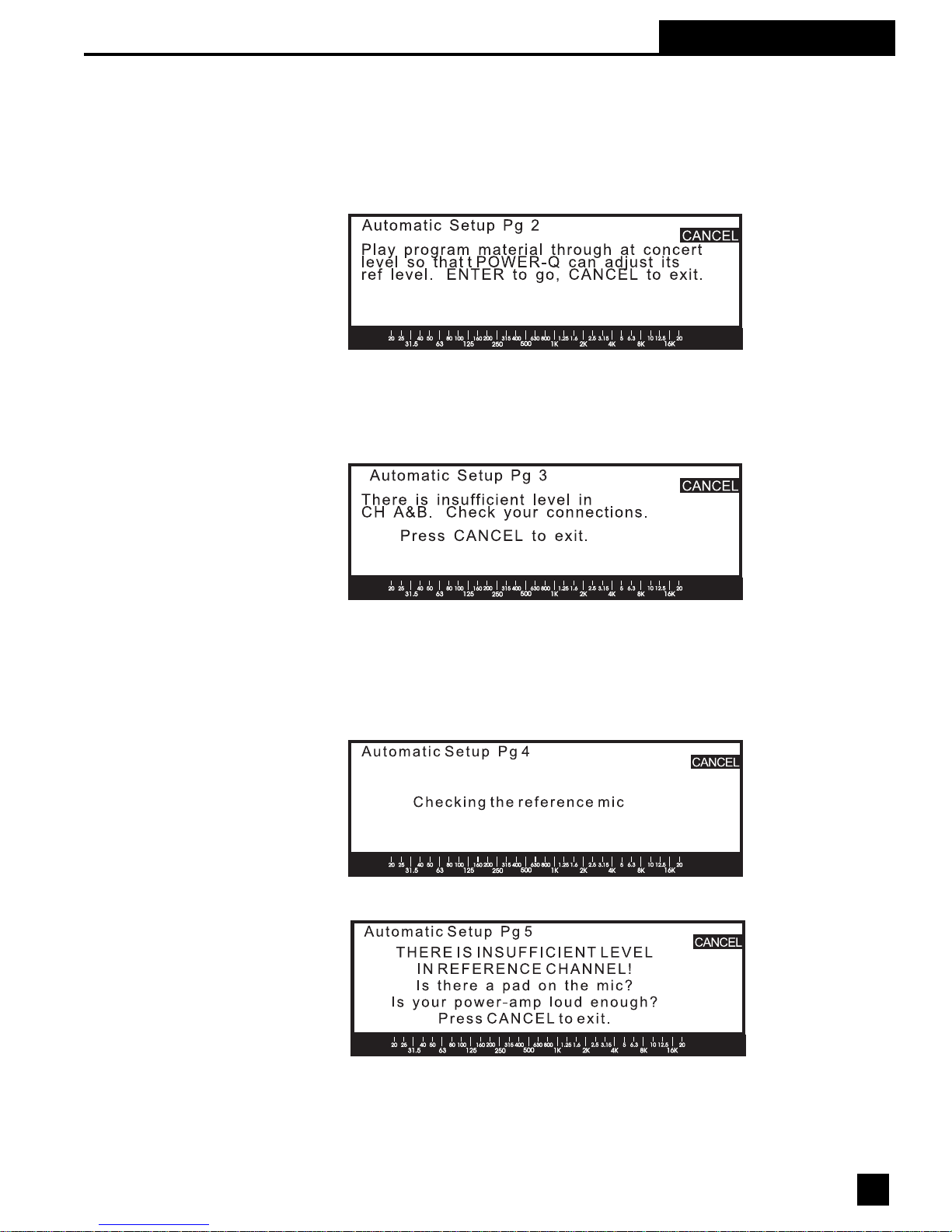

To execute Automatic Delay Alignment, press the ALIGN soft key in the DIGITAL DELA Y screen.

The following screen will appear:

Fig. 16: Auto Delay Setup page 1

20

Page 21

Section 8: Digital Delay

Your sound system must be set up and operational, and the gain of any equipment downstream in the signal path from

the POWER-Q must be turned up to operating level. You must also be able to play audio program (a prerecorded CD

will work fine) through the POWER-Q at concert levels. Finally , the reference microphone must be located in the

position you wish to use as your delay alignment reference.

When these conditions are met, press ENTER. The POWER-Q will display the following screen:

Fig. 17: Auto Delay Setup page 2

Play your audio program and press ENTER. The POWER-Q will verify that audio program is present at both inputs. If

there is no audio signal present in one or both channels, you will receive the following message. Note that there is no

reason to align speakers if you are only operating with one channel of the POWER-Q, and the unit will not allow you to

test only one channel when there is no signal present at one of its inputs.

Fig. 18: Auto Delay Setup page 3

Check your connections and signal path, and repeat the procedure.

If the POWER-Q detects the presence of a signal at its two inputs, it will automatically play a 1 Khz test signal, first to

calibrate the sensitivity of the reference microphone, and, second, to measure the time the signal takes to reach the

microphone after it is generated by the POWER-Q. This test will be repeated for the second channel. While the 1 Khz

signals are being tested, the POWER-Q will display page 4 as follows:

Fig. 19 : Auto Delay Setup page 4

In the event your microphone doesn’t hear a loud enough signal, you’ll see the following error message:

Fig.20: Auto Delay Setup page 5

21

Page 22

Section 8: Digital Delay

You may need to turn up your system gain downstream from the POWER-Q. Check your microphone and connections, and repeat the procedure as needed. Note that the POWER-Q will

automatically turn on or off the 20dB mic reference mic pad, as needed.

In rare instances, conditions may arise in which your microphone will not hear much energy from a

1KHz tone due to one of the following conditions:

· Crossover settings. If you are using a crossover that produces low frequency response at 1

KHz due to its settings, your system may not produce much sound in this frequency band, and

the reference mic may register insufficient level. Try changing your crossover frequencies.

· Room modes and phase cancellation. It’s unlikely but possible that the acoustics of the room

in which you’re set up may tend to de-emphasize 1KHz at particular locations, due to the outof-phase cancellation of direct and reflected sounds. Try moving your microphone position.

Once levels are sufficient, the screen below will appear:

Fig.21: Auto Delay Setup page 6

When the microphone hears the signal, the POWER-Q will time how long the signal takes to

reach the microphone from each channel’s output, and adjust the delay times to make the signals

arrive after the same length of time (subject to the 83.2 millisecond maximum value). The

POWER-Q will revert to displaying the DIGIT AL DELAY screen; however, each speaker’s output

delay , and the distance from each speaker to the reference microphone, will now be displayed,

and the speaker outputs will be aligned - as shown in the screen below:

Fig. 22: Auto Delay Report Screen

The entire procedure takes just a few seconds.

Note that the accuracy of the POWER-Q’s measurement of speaker distance will generally be

correct +/- approximately one foot. Higher frequencies than 1 KHz will produce greater accuracy ,

but may present other measurement problems for sound systems with roll offs in high end frequency response. In addition, in rare instances the reference microphone may confuse direct and

reflected sound, and err in its distance measurement by up to 5 feet. When in doubt, run the auto

setup several times and compare results.

22

Page 23

Section 9: Using The POWER-Q Automatic Room EQ

9.1 WHAT IS AUTOMATIC ROOM EQ? Sabine’s unique AUTOMATIC ROOM EQ feature is simply a

means of fast, automatic equalization, calculated by the POWER-Q on the basis of measurement

of acoustic energy heard at a reference microphone, and designed to provide a neutral, repeatable “starting point” for additional program equalization and signal processing. The EQ curve

calculated is designed to make the response curve heard at the microphone as flat as possible,

compensating for room acoustics and the frequency response of the sound system components.

9.2 HOW AUTOMATIC ROOM EQ WORKS. Sabine’s Automatic Room Equalization works in two steps:

1. Environmental Artifact Removal (EAR). First, the POWER-Q’s Environmental

Artifact Removal function measures the frequency response curve of ambient noise in the room,

as heard by the reference microphone placed in the optimal reference position. Most acoustical

environments exhibit some degree of unwanted sound artifacts (e.g., air conditioner rumble,

running fans). The POWER-Q measures this energy and calculates a temporary “noise curve.”

2. Room Analysis. Second, the POWER-Q measures the energy of pink noise played

through the sound system at the reference microphone. The POWER-Q will automatically boost

or cut frequencies to achieve as flat a room response as possible when the tones are played

through the sound system and heard at the reference microphone. This flat room response is

abbreviated “EQ RM” and is meant to serve as a consistent starting point for further adjustments.

Note that the frequencies heard and analyzed when the pink noise is played discount the “noise

curve” and represent only the interaction of audio played through the sound system and impacted

by the specific acoustics of the auditorium.

Section 9: Auto Room EQ

Note that the accuracy of measuring and compensating for ambient noise will improve when both

noise level and noise frequency are relatively constant. For best results, minimize or eliminate any

ambient noise sources when possible.

9.3. REFERENCE MICROPHONE CHOICE. Microphone placement, the type of microphone you

use, and the acoustics of the environment are important considerations for performing an

acoustic analysis such as the POWER-Q’s Automatic Room EQ. This is potentially quite a

complex subject and a complete discussion is beyond the scope of this manual. Any attempt to

equalize an acoustic environment will be subject to compromises and response variations from

one location to another. Nonetheless, it is possible to make adjustments that will improve the

system/room response for most if not all audience listening areas.

Ask 20 experts and you’re likely to get a variety of opinions and strategies about room equalization; suffice it to say that experience and your unique skill as an engineer will play a significant role

in your choice of mic type, model, and placement. For a more complete discussion on this

subject, please refer to John Murray's excellent article, "Doing the Right Thing" in the July/August

1997 issue of

For those of you who may want a relatively quick summary of what to consider about this topic,

read on.

Let’s first consider the type of microphone to be used.

LIVE SOUND! International.

First of all, the frequency response of the microphone should be as close to flat as possible, within

"1 dB from flat across the audible frequency range (20 Hz to 20khz), and should exhibit flat

response at both loud and quiet sound pressure levels. The greater the deviation from flat

response by the microphone, the greater the deviation from flat response your system may exhibit

when using the mic to set EQ.

23

Page 24

Section 9: Auto Room EQ

Most typically , either a cardioid, an omnidirectional, or a free-field microphone is used as a reference

microphone. A cardioid mic is directional in nature, that is, it is more sensitive to sound entering the front

of the capsule, in the same plane as the long dimension of the microphone, as shown below:

Cardiod mic

Fig. 23: Cardiod pick-up

pattern

rejects sound

from rear

An omnidirectional microphone is more equally sensitive to frequencies from all directions, also measured

in the plane of the microphone’s long dimension, as shown below:

Fig. 24: Omnidirectional pick-up pattern

A free-field microphone is a particular kind of omnidirectional microphone, designed to more closely

approximate the ideal free field (i.e., free from reflected sound) condition of a point-specific microphone

suspended in midair. Free-field mics are typically small diaphragm capsules (to minimize coloration from

sound reflections from the mic itself), and are generally pointed upward when used, to pick up sound in the

plane perpendicular to the plane of the length of the microphone, as shown below:

Sound Source

(facing mic)

Omnidirectional mics reveal no polar rejection of sound

Fig. 25: Free-field pick-up pattern

This orientation is more likely to produce accurate frequency response measurement in the same directional orientation as the ears of the listener, i.e., parallel to the floor and perpendicular to the apparent

direction of the microphone’s pointing.

In most circumstances a free-field microphone is the best choice for room analysis. However, in some

instances a cardioid mic may serve better. For example, in a small room, the direct sound field will be

much smaller in comparison to the reverberant field, and a cardioid ref mic aimed away from a close

reflective wall will minimize phase cancellation and coloration from reverberant sound.

The Sabine SQ-1000 is a free-field, exceptionally flat microphone, specially calibrated for use with the

Sabine POWER-Q and REAL-Q2. It is available from authorized Sabine dealers.

24

Free-Field Reference Mic in

Vertical Orientation

Page 25

Section 9: Auto Room EQ

9.4. REFERENCE MIC PLACEMENT It is an unfortunate reality of room acoustics that acoustic analysis may

vary quite a bit with differing reference microphone positions, depending on the size, shape and surface

reflections of the environment. For example, in very small rooms, or in the reverberant field of larger

spaces, the number of paths for sound reflection may produce less than optimal results due to the phase

interference patterns created by direct and reflected sound arriving at the reference microphone at different times. There are several rules of thumb you may follow to achieve the best, most accurate results of

room analysis:

· Position your reference mic where you think the audience will tend to congregate most, thus insuring

the best sound for the largest number of people.

· Keep the mic away from reflective surfaces (e.g., walls, corners, or large structures in the middle of a

room).

· Keep the mic relatively close to the front-of-house speakers (the direct sound field, where reflected

sounds are lower in magnitude relative to the sound coming directly from the speakers). The larger

the component of reflected sound in the sound heard by the reference mic, the greater the phase

cancellation and comb filtering.

· Bass frequency analysis is more prone to measurement anomalies than higher frequencies. The

smaller the room, the greater the problem. Use your ears and listen to bass response at different

room locations, in addition to considering the information and analysis of the POWER-Q.

· When running a mono sound source through two or more speaker stacks or enclosures, run Automatic Room EQ using only one speaker cabinet or stack, since sound arriving from multiple point

sources will arrive at the microphone at different times. When running a stereo source through a

stereo sound system, the POWER-Q will automatically analyze one channel at a time in sequence.

But again, multiple speakers in the sound path of either channel should be selectively disconnected so

only one speaker plays sound during the analysis.

NOTE: Make sure you plug only a microphone level signal into the POWER-Q reference microphone

input. Do not plug a microphone preamp into the reference input. This may cause the reference mic

board to overheat and damage the POWER-Q and will not be covered by the warranty .

9.5. POWER-Q CONTROLS FOR AUTOMATIC ROOM EQ. Select “AUTOMATIC ROOM EQ” from the display

window by pushing soft key #1 from the MAIN MENU.

Fig. 26: Automatic Room EQ, page 1.

Because pink noise is played at audible levels, do not run this procedure during a performance, or even

during rehearsal. Y ou should run the Automatic Room EQ procedure BEFORE the performers or audience arrive. To prevent accidental injection of pink noise through your sound system, the Automatic Room

EQ function requires you to deliberately choose the procedure by hitting the “ENTER” button when

prompted.

You may run the Automatic Room EQ analysis for either the A channel alone, the B channel alone, or both

channels in sequence depending on your application of the POWER-Q. Select “INIT A,” “INIT B,” or “INIT

A&B” using the left/right arrow keys before hitting the “ENTER” button to begin the analysis. NOTE: Any

time you run the Automatic Room EQ for a given channel, it will erase and replace the previous analysis

for the channel(s) chosen. In addition, the current program shaping curve will be erased from active

memory (though you may save the program curve and reload it from memory). For more information

about program shaping curves and memory options, see sections 10.2 and 16.0.

25

Page 26

Section 9: Auto Room EQ

Pressing ENTER displays Page 2 on the screen:

Fig. 27: Automatic Room EQ, page 2.

Make sure your POWER-Q is in place in the system (typically between the mixer output and the power

amp or crossover input), your system is turned on, your reference microphone is in the correct position,

oriented correctly , and plugged into the “Ref A” jack on the POWER-Q back panel, and you are ready to

play your audio program (a prerecorded CD will work fine) at performance levels.

High Frequency Roll-Off Compensation. The POWER-Q automatically calculates its room response curve to

either compensate or not for the high frequency roll-off detected by the reference mic as a function of

distance from the speaker playing the test signal. High frequencies are absorbed over distance to a

greater degree than low frequencies. If the reference mic detects attenuated high frequencies, the

POWER-Q will boost highs in the Room EQ curve to make up for this drop-off if “do not compensate” is

chosen. This may result in an overemphasis of high frequencies for audience members closer to the

speakers than the reference mic.

When the “Compensate” option is chosen, the POWER-Q inserts a high-frequency roll-off filter (12dB per

octave) to compensate for this overemphasis. The POWER-Q automatically measures the distance from the

speaker to the reference mic with a test tone, and calculates the appropriate roll-off, depending on the

speaker-to-mic distance. T o summarize, selecting COMPENSATE will cause the Automatic Room EQ

analysis to produce a response curve with more high frequency information at distances closer to the speakers.

In small rooms this compensation may not be necessary . To implement, simply highlight your choice to

compensate or not. Now play your test audio through the system. Set levels to concert volume, as the

POWER-Q will calibrate to the level you establish. Once the audio is playing, press “ENTER” again.

If the POWER-Q detects insufficient level at its inputs, this screen will notify you of the absence of signal in

either or both channels, as shown below:

Fig. 28: Auto Setup page 3

Note that this INSUFFICIENT LEVEL message refers to the INPUT audio signal present at either or both

inputs of the POWER-Q. You must play and audio signal (CD, tape or live music) long enough for the

POWER-Q to detect the signal and establish an operating level. This will typically take only a few seconds; then you can turn the audio signal. The input signal will be muted once the Automatic Room EQ

analysis begins.

If there is no signal in channel A or B, either your connections to the POWER-Q are bad, the POWER-Q may

be in bypass (“BP ASS” will flash in the upper right of your screen. Turn it off in the “GLOBAL P ARAMETERS”

menu.) or you are not providing an audio source to the POWER-Q. Check your connections, play your CD

and press "ENTER".

26

Page 27

Section 9: Auto Room EQ

When the POWER-Q detects an audio signal at its input(s), page 4 of the Automatic Room EQ menu will

indicate that the POWER-Q is testing the reference microphone for the presence of signal (a 1 KHz tone)

and calibrating the POWER-Q to the reference level heard by the microphone.

Fig. 29: Automatic Room EQ, page 4.

If a weak signal (or no signal) is detected at the reference microphone input, the POWER-Q will prompt

you with Page 5:

Fig. 30: Automatic Room EQ, page 5.

Note that this INSUFFICIENT LEVEL message refers to the audio detected by the reference microphone,

NOT the signal present at the channel inputs of the POWER-Q Make sure you are using a working

microphone plugged into the “REF A” input on the back of the POWER-Q with a correctly wired cable. If

you are using a reference mic that requires phantom power, turn on the phantom power in the “GLOBAL

P ARAMETERS” section, accessed from the MAIN MENU. If all else fails, try moving the microphone. It's

possible your position may not permit the microphone to "hear" the 1kHz tone due to phase cancellation.

In rare instances (e.g., extremely loud conditions) it’s possible that the signal heard at the reference mic

input might be too "hot", which will produce an alternative error message:

Fig. 31: Automatic Room EQ

Alternative page 5.

You may need to put a pad on the microphone or at the POWER-Q input (via Global Parameters). Alternatively , try placing the microphone a further distance from the speakers.

Once your reference microphone is plugged in, positioned correctly and working, the Automatic Room EQ

analysis will begin, as indicated by page 6 of the menu.

Fig. 32: Automatic Room EQ, page 6.

The POWER-Q plays a burst of pink noise for a few seconds, measures energy per octave as heard at the

reference mic input, and performs thousands of calculations to adjust its graphic EQ filters to make this

response as flat as possible. The entire process will take about 10 seconds per channel. Then page 6

screen will indicate the POWER-Q channel being analyzed.

27

Page 28

Section 9: Auto Room EQ

When the analysis is complete, the POWER-Q will display page 7:

Fig. 33: Automatic Room EQ, page 7.

The analysis shows the high and low frequency roll-offs inherent in your sound system, and this

screen allows the user the option of having the POWER-Q insert matching high pass and low

pass filters. Press ENTER to insert the HPF and LPF, or press CANCEL if you choose not to

insert roll-offs. Either ENTER or CANCEL will return you to the MAIN MENU. Note that if your

system response is quite flat from 20 Hz to 20 kHz, page 7 will not be displayed, and the

POWER-Q will return you to the MAIN MENU.

It is possible to interrupt the Automatic Room EQ function at any time by pressing the “CANCEL” soft key. This will return you to the MAIN MENU. If you do this after the procedure

begins, but prior to its conclusion, the ROOM EQ response will be reset to zero boost/cut.

Important: Note that the AUTOMATIC ROOM EQ function will NOT add more than 6 dB boost

to any EQ slider.

Also, note that the Graphic EQ screen on the POWER-Q will NOT show any boost or cut of

sliders after the Automatic Room EQ function is completed. The Auto Room EQ settings are

shown only as a superimposed response curve, leaving the EQ sliders free for you to make

additional changes to the EQ (what we call Program EQ). The total EQ and filtering added by

the POWER-Q will produce an EQ curve that can be displayed by pressing the third soft key

(CURVE/CU A/CU B/CUA&B), which selects the curve display you desire (either channel singly ,

both channels together, or no curve). Prior to adding (or when bypassing these features, using

the BYP ASS screen from the MAIN MENU) any additional filtering or program EQ, this curve

will display the adjustments calculated by the POWER-Q to make the room/system response

as flat as possible at the reference microphone position. Different curve display options thus

can show the results of separate POWER-Q EQ adjustments or all adjustments together. For

more information, see Section 10.

28

Page 29

Section 10: Using The POWER-Q Graphic Equalizer

10.1 GRAPHIC EQUALIZER APPLICATIONS. Automatic Room EQ or an RTA analysis will produce a

room EQ curve that may best be regarded as a starting point or baseline for further fine tuning with

the second level of POWER-Q graphic EQ controls, which are user adjustable. Experienced

graphic equalizer users employ a variety of methods to arrive at their preferred sound, and the

POWER-Q allows your personal touch in determining the way your system sounds.

A graphic equalizer is an engineer’s most common choice for compensating for less than ideal

acoustical reproduction. The quality of equipment used, the placement of speakers and the

acoustical properties of a room will rarely result in tonally balanced sound reproduction. Even the

best sound equipment will not produce sound to its optimal potential in most acoustical environments; for example, reflective parallel room surfaces (wall to wall, floor to ceiling) will create

standing waves and acoustic resonances that will vary as a function of room dimensions.

A multiband graphic equalizer can compensate for unequal acoustical energy across the frequency

bands of the audio spectrum. The POWER-Q graphic EQ provides you with a choice of measurement and calibration aids to perform automatic equalization, or it will allow you to rely on your own

experience and hearing acuity to equalize an acoustical space. Y ou can even combine methods. In

fact, the POWER-Q goes a step further, providing you with some very powerful advantages for making a sound system sound as good as it can. Y ou can arrive at a baseline “flat response” curve by one

of two methods: by performing the POWER-Q Automatic Room EQ function (see Section 9), or by

using the RTA to analyze pink or white noise played through your sound system into a reference

microphone (see Section 13). However, you may not want to stop there. Many sound engineers can

improve the sound of a flat response system and will tweak the sound of the EQ further, perhaps

changing the overall frequency balance to match the performers’ style or the requirements of a particular application. In such situations, the POWER-Q truly lives up to its name.

Section 10: Graphic EQ

To fully understand the powerful options made available with the POWER-Q, think of the unit as

containing two separate graphic EQs. The “first” EQ is automatically set by the POWER-Q using

the Automatic Room EQ function (see Section 9). Its function is to make the frequency response

of the acoustical environment as even as possible, or flat. We call this response curve the “Room

EQ.” Although the POWER-Q makes graphic EQ adjustments to produce the Room EQ, the

actual slider settings for these adjustments are NOT displayed; instead, the graphic EQ screen will

display a graphic EQ settings as flat. Think of this as the default starting point for you to sculpt

sound, adding EQ as needed for the various applications you may use for the POWER-Q, even in

the same auditorium.

In actual practice, many or most sound engineers will choose to adjust EQ settings differently for

various applications. For example, the system EQ desirable for a hip-hop artist would likely require

more low end boost than would be appropriate for an acoustic folk artist. This additional application-specific EQ is the “second” EQ added to the sound. Let’s call it the “Program EQ.”

The actual total EQ added to your program by the POWER-Q is the combination of Room EQ,

Program EQ, FBX filters, parametric filters, and high and low pass filters. The resultant total curve

reflecting all these changes can be viewed in both the graphic EQ and FBX/Parametric Filter

screens. This curve shows a combination of all EQ and filtering currently active in the POWER-Q;

bypassing Room or Program EQ (see Section 22) will change the curve display accordingly . A