Page 1

IN 112 Rev. A 0399

Providing Exceptional Consumer Optical Products Since 1975

Customer Support (800) 676-1343

E-mail: support@telescope.com

Corporate Offices (831) 763-7000

P.O. Box 1815, Santa Cruz, CA 95061

INSTRUCTION MANUAL

Orion

®

Skywatcher

™

90mm EQ

#9024 Equatorial Refracting Telescope

Page 2

2

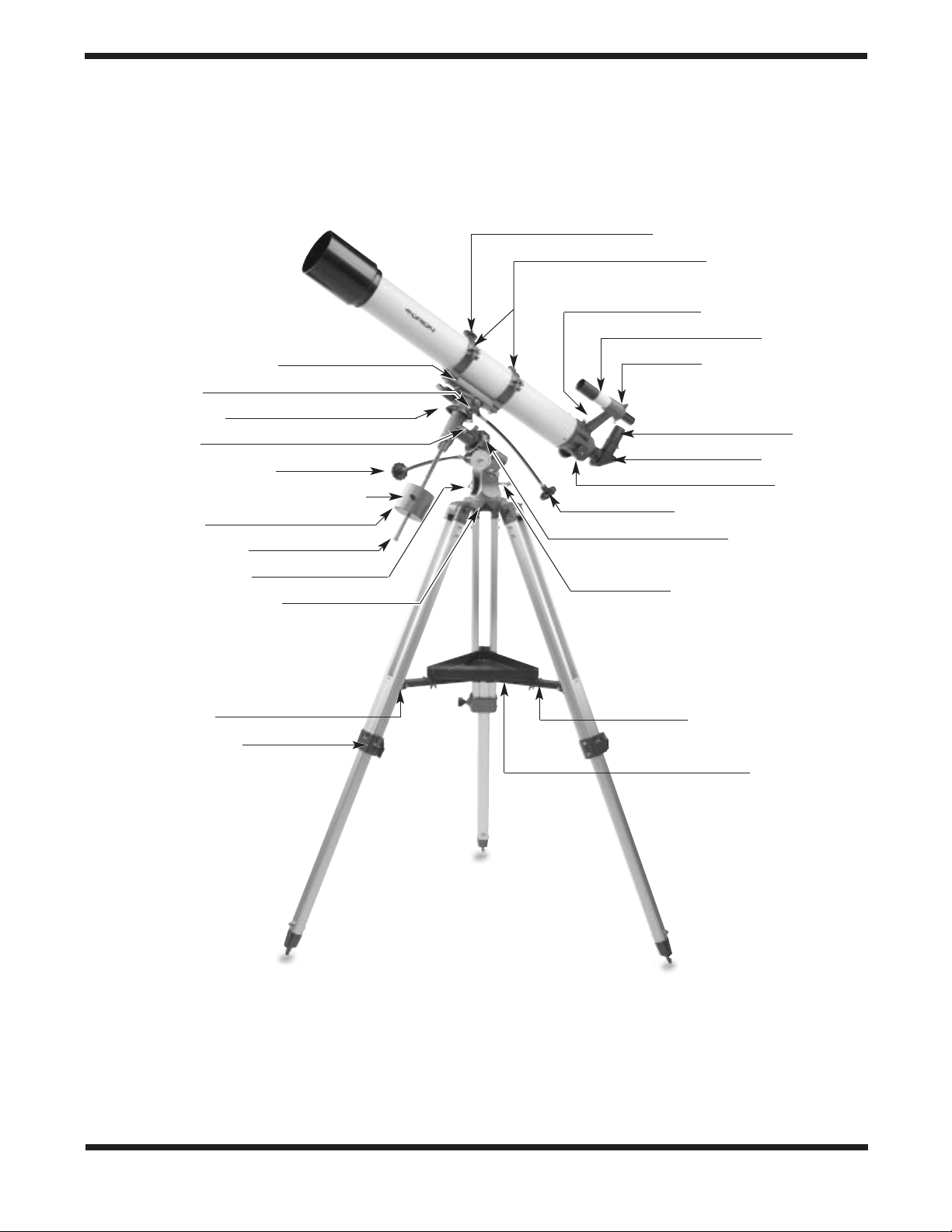

Figure 1. Skywatcher 90 EQ Parts Diagram

Tube ring mounting plate

Dec. lock knob

Dec. setting circle

R.A. lock knob

R.A. slow-motion control

Counterweight locking thumbscrew

Counterweight

Counterweight shaft

Latitude locking t-bolt

Azimuth adjustment knob

Accessory tray bracket

attachment point

Tripod leg lock knob

Piggy back camera adapter

Tube mounting rings

Finder scope bracket

Finder scope

Alignment screws (3)

Eyepiece

Star diagonal

Focus knob

Dec. slow-motion control

R.A. setting circle

Latitude adjustment t-bolt

Accessory tray bracket

Accessory tray

Page 3

3

1. Parts List

Qty. Description

1 Optical tube assembly

1 German-type equatorial mount

2 Slow-motion control cables

1 Counterweight

1 Counterweight shaft

3 Tripod legs

1 Accessory tray with mounting hardware

1 Accessory tray bracket

2 Optical tube mounting rings (located on optical tube)

1 6x30 achromatic crosshair finder scope

1 Finder scope bracket

1 Mirror star diagonal (1.25")

1 25mm (36x) Kellner eyepiece (1.25")

1 10mm (91x) Kellner eyepiece (1.25")

1 Objective lens dust cap

4 Assembly Tools (2 wrenches, Phillips-head screwdriver,

flat-head screwdriver key)

2. Assembly

Carefully open all of the boxes in the shipping container. Make

sure all the parts listed in Section 1 are present. Save the box es

and packaging material. In the unlikely event that you need to

return the telescope, you must use the original packaging.

Assembling the telescope for the first time should take about

20 minutes. No tools are needed other than the ones provided. All bolts should be tightened securely to eliminate flexing

and wobbling, but be careful not to o v er-tighten or the threads

may strip.Refer to Figure 1 during the assembly process.

During assembly (and anytime, for that matter), DO NOT touch

the surfaces of the telescope objective lens or the lensesof the

C

ongratulations on your purchase of a quality Orion telescope.

Your new Skywatcher 90mm EQ

Refractor is designed for high-resolution viewing of astronomical objects. With its precision optics and

equatorial mount, you’ll be able to locate and enjoy hundreds of fascinating celestial denizens, including

the planets, Moon, and a variety of deep-sky galaxies, nebulas, and star clusters.

If you have never owned a telescope before, we would like to welcome you to amateur astronomy.Take

some time to familiarize yourself with the night sky. Lear n to recognize the patterns of stars in the major

constellations; a star wheel, or planisphere, available from Orion or from your local telescope shop, will

greatly help.With a little practice, a little patience, and a reasonably dark sky away from city lights, you’ll

find your telescope to be a never-ending source of wonder, exploration, and relaxation.

These instructions will help you set up, properly use, and care f or y our telescope.Please read them ov er

thoroughly before getting started.

Table of Contents

1. Parts List............................................................................................................................... 3

2. Assembly.............................................................................................................................. 3

3. Balancing the Telescope.......................................................................................................4

4. Aligning the Finder Scope.................................................................................................... 5

5. Setting Up and Using the Equatorial Mount ......................................................................... 5

6. Using Your T elescope-Astronomical Observing.................................................................... 7

7. Astrophotography................................................................................................................. 9

8. Terrestrial Viewing................................................................................................................. 10

9. Care and Maintenance......................................................................................................... 10

10. Specifications........................................................................................................................ 10

WARNING:

Never look directly at the Sun

through your telescope or its finder scope—

even for an instant—without a professionally

made solar filter that completely covers the

front of the instrument, or permanent eye

damage could result.Young children should use

this telescope only with adult supervision.

Page 4

4

finder scope or eyepieces with your fingers. The optical surfaces have delicate coatings on them that can easily be

damaged if touched inappropriately .NEVER remove any lens

assembly from its housing for any reason, or the product w arranty and return policy will be void.

1. Lay the equatorial mount on its side. Attach the tripod

legs, one at a time, to the mount by sliding the bolts

installed in the tops of the tripod legs into the slots at the

base of the mount and tightening the wingnuts finger-tight.

Note that the accessory tray bracket attachment point on

each leg should face inward.

2. Tighten the leg lock knobs at the base of the tripod legs.

For now, keep the legs at their shor test (fully retracted)

length; you can extend them to a more desirable length

later, after the scope is completely assembled.

3. With the tripod legs now attached to the equatorial mount,

stand the tripod upright (be careful!) and spread the legs

apart enough to connect each end of the accessory tray

bracket to the attachment point on each leg. Use the bolt

that comes installed in each attachment point to do this.

First remove the bolt, then line up one of the ends of the

bracket with the attachment point and reinstall the bolt.

Make sure the smooth side of the accessory tray bracket

faces upwards.

4. Now , with the accessory tra y br acket attached, spread the

tripod legs apart as far as they will go, until the bracket is

taut. Attach the accessory tray to the accessory tray

bracket with the 3 wingnut-head bolts already installed in

the tray. This is done by pushing the bolts up through the

holes in the accessory tray bracket, and then threading

them into the holes in the accessory tray.

5. Next, tighten the bolts at the tops of the tripod legs, so the

legs are securely fastened to the equatorial mount. Use

the larger wrench and your fingers to do this.

6. Orient the equatorial mount as it appears in Figure 1, at a

latitude of about 40, (i.e., so the pointer next to the latitude

scale—located directly above the latitude locking t-bolt—

is pointing to the hash mark at “40.”) To do this, loosen the

latitude locking t-bolt, and turn the latitude adjustment tbolt until the pointer and the “40” line up.Then tighten the

latitude locking t-bolt. The declination (Dec.) and right

ascension (R.A.) axes may need repositioning (rotation)

as well. Be sure to loosen the R.A. and Dec. lock knobs

before doing this.Retighten the R.A. and Dec. lock knobs

once the equatorial mount is properly oriented.

7. Slide the counterweight onto the counterweight shaft.

Make sure the counterweight locking thumbscrew is adequately loosened so the metal pin the thumbscrew pushes

against (inside the counterweight) is recessed enough to

allow the counterweight shaft to pass through the hole in

the counterweight.

8. Now, with the counterweight locking thumbscrew still

loose, grip the counterweight with one hand and thread

the shaft into the equatorial mount (at the base of the declination axis) with the other hand. When it is threaded as

far in as it will go, position the counterweight about

halfway up the shaft and tighten the counterweight locking

thumbscrew.

9. Attach the two tube rings to the equatorial head using the

bolts that come installed in the bottom of the rings. First

remove the bolts, then push the bolts, with the washers

still attached, up through the holes in the tube ring mounting plate (on the top of the equatorial mount) and

re-thread them into the bottom of the tube rings. Tighten

the bolts securely with the smaller wrench. Open the tube

rings by first loosening the knurled ring clamps.

10.Lay the telescope optical tube in the tube rings at about the

midpoint of the tube’s length. Rotate the tube in the rings

so the focus knobs are on the underside of the telescope.

Close the rings over the tube and tighten the knurled ring

clamps finger-tight to secure the telescope in position.

11.Now attach the two slow-motion cables to the R.A.and Dec.

worm gear shafts of the equatorial mount by positioning the

setscrew on the end of the cable over the indented slot on

the worm gear shaft.Then tighten the setscrew.

12. Place the finder scope in the finder scope bracket by first

backing off all three alignment screws until the screw tips

are flush with the inside diameter of the bracket.Place the

O-ring that comes on the base of the bracket over the

body of the finder scope until it seats into the slot in the

middle of the finder scope.Slide the ey epiece end (narrow

end) of the finder scope into the end of the bracket’s cylinder that does not have the adjustment screws. Push the

finder scope through the bracket until the groove on the

eyepiece end of the finder scope lines up with the three

adjustment screws.The O-r ing should seat just inside the

front opening of the bracket’s cylinder. Tighten the three

alignment screws equally to secure the finder scope in

place. You may need to first back off the knurled locking

nuts on the adjustment screws to do this.

13. Insert the base of the finder scope bracket into the dovetail slot on the top of the focuser housing.Lock the br ac k et

in position by tightening the knurled setscrew on the dov etail slot.

14.Insert the chrome barrel of the star diagonal into the

focuser drawtube and secure with the thumbscrew on the

drawtube.

15.Then insert an eyepiece into the star diagonal and secure

it in place with the thumbscrews on the diagonal. (Always

loosen the thumbscrews before rotating or removing the

diagonal or an eyepiece.)

3. Balancing the Telescope

To insure smooth movement of the telescope on both axes of

the equatorial mount, it is imperative that the optical tube be

properly balanced. We will first balance the telescope with

respect to the R.A. axis, then the Dec. axis.

1. Keeping one hand on the telescope optical tube, loosen

the R.A. lock knob. Make sure the Dec. lock knob is

locked, for now. The telescope should now be able to

Page 5

5

rotate freely about the R.A. axis. Rotate it until the counterweight shaft is parallel to the ground (i.e., horizontal).

2. Now loosen the counterweight locking thumbscrew and

slide the weight along the shaft until it exactly counterbalances the telescope. (Figure 2a) That’s the point at which

the shaft remains horizontal even when you let go with

both hands (Figure 2b).

3. Retighten the counterweight locking thumbscrew. The telescope is now balanced on the R.A. axis.

4. To balance the telescope on the Dec. axis, first tighten the

R.A.lock knob , with the counterweight shaft still in the horizontal position.

5. With one hand on the telescope optical tube, loosen the

Dec. lock knob (Figure 2c). The telescope should now be

able to rotate freely about the Dec. axis. Loosen the tube

ring clamps a few turns, until you can slide the telescope

tube forward and back inside the rings (this can be aided

by using a slight twisting motion on the optical tube while

you push or pull on it) (Figure 2d).

6. Position the telescope in the mounting rings so it remains

horizontal when you carefully let go with both hands.This

is the balance point for the optical tube with respect to the

Dec. axis (Figure 2e).

7. Retighten the tube ring clamps.

The telescope is now balanced on both axes.Now when you

loosen the lock knob on one or both axes and manually point

the telescope, it should move without resistance and should

not drift from where you point it.

4. Aligning the Finder Scope

A finder scope has a wide field of view to facilitate the location of objects for subsequent viewing through the main

telescope, which has a much narrower field of view. The finder scope and the main telescope must be aligned so they

point to exactly the same spot in the sky.

Alignment is easiest to do in daylight hours. First, inser t the

lowest-power (25mm) eyepiece into the star diagonal. Then

loosen the R.A. and Dec. lock knobs so the telescope can be

moved freely.

Point the main telescope at a discrete object such as the top

of a telephone pole or a street sign that is at least a quartermile away. Move the telescope so the target object appears in

the very center of the field of view when you look into the eyepiece. Now tighten the R.A. and Dec. lock knobs. Use the

slow-motion control knobs to re-center the object in the field of

view , if it mo ved off-center when you tightened the lock knobs.

Now look through the finder scope. Is the object centered in

the finder scope’s field of view, (i.e., at the intersection of the

crosshairs)? If not, hopefully it will be visible somewhere in

the field of view, so that only fine adjustment of the finder

scope alignment screws will be needed to center it on the

crosshairs. Otherwise you’ll have to make coarser adjustments to the alignment screws to redirect the aim of the finder

scope. Make sure the knurled lock nut on each alignment

screw is loosened before making any adjustments.

Once the target object is centered on the crosshairs of the

finder scope, look again in the main telescope’s e y epiece and

see if it is still centered there as well. If it isn’t, repeat the

entire process, making sure not to move the main telescope

while adjusting the alignment of the finder scope.

When the target object is centered on the crosshairs of the

finder scope and in the telescope’s eyepiece, tighten the

knurled lock nuts on the alignment screws to lock the finder

scope into position.The finder scope is now aligned and ready

to be used for an observing session. The finder scope and

bracket can be remov ed from the do v etail for storage, and then

re-installed without changing the finder scope’s alignment.

Note that the image seen through the finder scope appears

upside down.This is normal for astronomical finder scopes.

5. Setting Up and Using

the Equatorial Mount

When you look at the night sky, you no doubt have noticed

that the stars appear to move slowly from east to west over

time. That apparent motion is caused by the Earth’s rotation

(from west to east). An equatorial mount (Figure 3) is

designed to compensate for that motion, allowing you to easily “track” the movement of astronomical objects, thereby

keeping them from drifting out of the telescope’s field of view

while you’re observing.

This is accomplished by slowly rotating the telescope on its

right ascension (polar) axis, using only the R.A. slow-motion

cable.But first the R.A. axis of the mount must be aligned with

the Earth’s rotational (polar) axis—a process called polar

alignment.

Polar Alignment

For Northern Hemisphere observers, approximate polar

alignment is achieved b y pointing the mount’s R.A. axis at the

North Star, or Polaris. It lies within 1 degree of the north

celestial pole (NCP), which is an extension of the Earth’s rotational axis out into space. Stars in the Nor thern Hemisphere

appear to revolve around Polaris.

To find Polaris in the sky, look north and locate the patter n of

the Big Dipper (Figure 4). The two stars at the end of the

“bowl” of the Big Dipper point right to Polaris.

Observers in the Southern Hemisphere aren’t so fortunate to

have a bright star so near the south celestial pole (SCP).The

star Sigma Octantis lies about 1 degree from the SCP, but it

is barely visible with the naked eye (magnitude 5.5).

For general visual observation, an approximate polar alignment is sufficient:

1. Level the equatorial mount by adjusting the length of the

three tripod legs.

2. Loosen the latitude locking t-bolt.Turn the latitude adjusting t-bolt and tilt the mount until the pointer on the latitude

Page 6

6

scale is set at the latitude of your observing site. If you

don’t know your latitude, consult a geographical atlas to

find it. For example, if your latitude is 35° North, set the

pointer to +35. Then retighten the latitude locking t-bolt.

The latitude setting should not have to be adjusted again

unless you move to a different viewing location some distance away.

3. Loosen the Dec. lock knob and rotate the telescope optical tube until it is parallel with the R.A.axis.The pointer on

the Dec.setting circle should read 90°.Retighten the Dec.

lock knob.

4. Loosen the azimuth adjustment knob and rotate the entire

equatorial mount left-to-right so the telescope tube (and

R.A. axis) points roughly at Polaris. If you cannot see

Polaris directly from your observing site, consult a compass and rotate the equatorial mount so the telescope

points North. Retighten the azimuth adjustment knob.

The equatorial mount is now approximately polar-aligned for

casual observing.More precise polar alignment is required for

astrophotography.Sever al methods exist and are described in

many amateur astronomy reference books and astronomy

magazines.

Note: From this point on in your observing session, you

should not make any further adjustments in the azimuth

or the latitude of the mount, nor should you move the tripod.Doing so will undo the polar alignment.The telescope

should be moved only about its R.A. and Dec. axes.

Tracking Celestial Objects

When you observe a celestial object through the telescope,

you’ll see it drift slowly across the field of view. To keep it in

the field, if your equatorial mount is polar-aligned, just turn the

R.A. slow-motion control.The Dec. slow-motion control is not

needed for tracking. Objects will appear to move faster at

higher magnifications, because the field of view is narrower.

Optional Motor Drives for Automatic Tracking

and Astrophotography

An optional DC motor drive (#7827) can be mounted on the

R.A. axis of the Skywatcher’s equatorial mount to provide

hands-free tracking.Objects will then remain stationary in the

field of view without any manual adjustment of the R.A.slowmotion control. The motor drive is necessary for

astrophotography.

Understanding the Setting Circles

The setting circles on an equatorial mount enable you to

locate celestial objects by their “celestial coordinates.” Every

astronomical object resides in a specific location on the

“celestial sphere.” That location is denoted by two numbers:

its right ascension (R.A.) and declination (Dec.). In the same

way, every location on Earth can be described by its longitude

and latitude. R.A. is similar to longitude on Earth, and Dec. is

similar to latitude. The R.A. and Dec. values for celestial

objects can be found in any star atlas or star catalog.

So, the coordinates for the Orion Nebula listed in a star atlas

will look like this:

R.A. 5h 35.4m Dec. -5° 27'

That’s 5 hours and 35.4 minutes in right ascension, and -5

degrees and 27 arc-minutes in declination (the negative sign

denotes south of the celestial equator).There are 60 minutes

in 1 hour of R.A. and there are 60 arc-minutes in 1 degree of

declination.

The telescope’s R.A. setting circle is scaled in hours, from 1

through 24, with small hash marks in between representing

10-minute increments. The lower set of numbers (closest to

the plastic R.A. gear cover) apply to viewing in the Northern

Hemisphere, while the numbers above them apply to viewing

in the Southern Hemisphere.The Dec.setting circle is scaled

in degrees.

Before you can use the setting circles to locate objects, the

mount must be polar aligned, and the setting circles must be

calibrated.The declination setting circle was calibrated at the

factory, and should read 90° when the telescope optical tube

is pointing exactly along the polar axis.

Calibrating the Right Ascension Setting Circle

1. Identify a bright star near the celestial equator and look up

its coordinates in a star atlas.

2. Loosen the R.A. and Dec. lock knobs on the equatorial

mount, so the telescope optical tube can move freely.

3. Point the telescope at the bright star near the celestial equator whose coordinates you know. Center the star in the

telescope’s field of view. Lock the R.A. and Dec. lock knobs.

4. Rotate the R.A. setting circle so the pointer indicates the

R.A. listed for the bright star in the star atlas.

Finding Objects With the Setting Circles

Now that both setting circles are calibrated, look up in a star

atlas the coordinates of an object you wish to view.

1. Loosen the Dec. lock knob and rotate the telescope until

the Dec. value from the star atlas matches the reading on

the Dec.setting circle.Retighten the lock knob.Note:If the

telescope is aimed south and the Dec. setting circle pointer passes the 0° indicator, the value on the Dec. setting

circle becomes a negative number.

2. Loosen the R.A. lock knob and rotate the telescope until

the R.A. value from the star atlas matches the reading on

the R.A. setting circle. Retighten the lock knob.

Most setting circles are not accurate enough to put an object

dead-center in your finder scope’s field of view, but they’ll get

you close, assuming the equatorial mount is accurately polaraligned. The R.A. setting circle should be re-calibrated every

time you wish to locate a new object.Do so by calibrating the

setting circle for the centered object before moving on to the

next one.

Confused About Pointing the Telescope?

Beginners occasionally experience some confusion about

how to point the telescope overhead or in other directions.In

Page 7

7

Figure 1 the telescope is pointed north as it would be during

polar alignment. The counterweight shaft is oriented downward.But it will not look like that when the telescope is pointed

in other directions. Let’s say you want to view an object that is

directly overhead, at the zenith.How do you do it?

One thing you DO NOT do is make any adjustment to the latitude adjusting t-bolt. That will undo the mount’s polar

alignment. Remember, once the mount is polar-aligned, the

telescope should be moved only on the R.A. and Dec. axes.

To point the scope overhead, first loosen the R.A. lock knob

and rotate the telescope on the R.A. axis until the counterweight shaft is horizontal (parallel to the ground).Then loosen

the Dec. lock knob and rotate the telescope until it is pointing

straight overhead.The counterweight shaft is still horizontal.

Then retighten both lock knobs.

Similarly, to point the telescope directly south, the counterweight shaft should again be horizontal. Then you simply

rotate the scope on the Dec. axis until it points in the south

direction (Figure 5a).

What if you need to aim the telescope directly north, but at an

object that is nearer to the horizon than Polaris? You can’t do

it with the counterweight down as pictured in Figure 1.Again,

you have to rotate the scope in R.A. so the counterweight

shaft is positioned horizontally.Then rotate the scope in Dec.

so it points to where you want it near the horizon (Figure 5b).

To point the telescope to the east (Figure 5c) or west (Figure

5d), or in other directions, rotate the telescope on its R.A.and

Dec. axes. Depending on the altitude of the object you want

to observe, the counterweight shaft will be oriented somewhere between vertical and horizontal.

The key things to remember when pointing the telescope is that

a) you only move it in R.A.and Dec., not in azimuth or latitude

(altitude), and b) the counterweight and shaft will not always

appear as it does in Figure 1. In fact it almost never will!

6. Using Your Telescope Astronomical Observing

Choosing an Observing Site

When selecting a location for observing, get as far away as

possible from direct artificial light such as streetlights, porch

lights, and automobile headlights.The glare from these lights

will greatly impair your dark-adapted night vision.Set up on a

grass or dirt surface, not asphalt, because asphalt radiates

more heat. Heat disturbs the surrounding air and degrades

the images seen through the telescope. Avoid viewing over

rooftops and chimneys, as they often have warm air currents

rising from them. Similarly, avoid observing from indoors

through an open (or closed) window, because the temperature difference between the indoor and outdoor air will cause

image blurring and distortion.

If at all possible, escape the light-polluted city sky and head

for darker country skies.You’ll be amazed at how many more

stars and deep-sky objects are visible in a dark sky!

Cooling the Telescope

All optical instruments need time to reach “thermal equilibrium. ”The bigger the instrument and the larger the temperature

change, the more time is needed.Allow at least a half-hour f or

your telescope to cool to the temperature outdoors. In very

cold climates (below freezing), it is essential to store the telescope as cold as possible. If it has to adjust to more than a

40° temperature change, allow at least one hour.

Aiming the Telescope

To view an object in the main telescope, first loosen both the

R.A.and Dec.lock knobs.Aim the telescope at the object you

wish to observe by “eyeballing” along the length of the telescope tube (or use the setting circles to “dial in” the object’s

coordinates). Then look through the (aligned) finder scope

and move the telescope tube until the object is generally centered on the finder’s crosshairs.Retighten the R.A. and Dec.

lock knobs.Then accurately center the object on the finder’s

crosshairs using the R.A. and Dec. slow-motion controls.The

object should now be visible in the main telescope with a lowpower (long focal length) e yepiece.If necessary, use the R.A.

and Dec. slow-motion controls to reposition the object within

the field of view of the main telescope’s eyepiece.

Focusing the Telescope

Practice focusing the telescope in the daytime before using it

for the first time at night. Start by turning the focus knob until

the focuser drawtube is near the center of its adjustment

range. Insert the star diagonal into the focuser drawtube and

an eyepiece into the star diagonal (secure with the thumbscrews). Point the telescope at a distant subject and center it

in the field of view. Now, slowly rotate the focus knob until the

object comes into sharp focus. Go a little bit beyond sharp

focus until the image just starts to blur again, then reverse the

rotation of the knob, just to make sure you hit the exact focus

point. The telescope can only focus on objects at least 50 to

100 feet away.

Do You Wear Eyeglasses?

If you wear eyeglasses, you may be able to keep them on

while you observe, if your eyepieces have enough “eye relief”

to allow you to see the whole field of view.You can try this by

looking through the eyepiece first with your glasses on and

then with them off, and see if the glasses restrict the view to

only a portion of the full field. If they do, you can easily

observe with your glasses off by just refocusing the telescope

the needed amount.

Calculating the Magnification

It is desirable to have a range of eyepieces of different focal

lengths, to allow viewing over a range of magnifications. To

calculate the magnification, or power, of a telescope, simply

divide the focal length of the telescope by the focal length of

the eyepiece (the number printed on the eyepiece):

Telescope F.L. ÷Eyepiece F.L. = Magnification

Page 8

8

For example , the Skywatcher 90 EQ, which has a focal length

of 910mm, used in combination with a 25mm eyepiece, yields

a power of

910 ÷ 25 = 36x.

Every telescope has a useful limit of power of about 45x-60x

per inch of aperture. Claims of higher power by some telescope manufacturers are a misleading advertising gimmick

and should be dismissed.Keep in mind that at higher po wers ,

an image will always be dimmer and less sharp (this is a fundamental law of optics). The steadiness of the air (the

“seeing”) will limit how much magnification an image can tolerate.

Always start viewing with your lowest-power (longest focal

length) eyepiece in the telescope.After you have located and

looked at the object with it, you can try switching to a higher

power eyepiece to ferret out more detail, if atmospheric conditions permit. If the image you see is not crisp and steady,

reduce the magnification by switching to a longer focal length

eyepiece. As a general rule, a small but well-resolved image

will show more detail and provide a more enjoy able view than

a dim and fuzzy, over-magnified image.

Let Your Eyes Dark-Adapt

Don’t expect to go from a lighted house into the darkness of

the outdoors at night and immediately see faint nebulas,

galaxies, and star clusters—or even very many stars, for that

matter. Your eyes take about 30 minutes to reach perhaps

80% of their full dark-adapted sensitivity. As your eyes

become dark-adapted, more stars will glimmer into view and

you’ll be able to see fainter details in objects you view in your

telescope.

To see what you’re doing in the darkness, use a red-filtered

flashlight rather than a white light. Red light does not spoil

your eyes’ dark adaptation like white light does. A flashlight

with a red LED light is ideal, such as the Orion RedBeam

(part #5744), or you can cover the front of a regular incandescent flashlight with red cellophane or paper. Beware, too,

that nearby porch lights, streetlights, and car headlights will

ruin your night vision.

“Seeing” and Transparency

Atmospheric conditions vary significantly from night to night.

“Seeing”refers to the steadiness of the Earth’s atmosphere at

a given time.In conditions of poor seeing, atmospheric turbulence causes objects viewed through the telescope to “boil.” If

the stars are twinkling noticeably when you look up at the sky

with just your eyes, the seeing is bad and you will be limited

to viewing with low powers (bad seeing aff ects images at high

powers more severely). Planetary observing may also be

poor.

In conditions of good seeing, star twinkling is minimal and

images appear steady in the eyepiece. Seeing is best overhead, worst at the horizon. Also, seeing generally gets better

after midnight, when much of the heat absorbed by the Earth

during the day has radiated off into space.

Avoid looking over buildings, pavement, or any other source

of heat, as they will cause “heat wave” disturbances that will

distort the image you see through the telescope.

Especially important for observing faint objects is good “transparency”—air free of moisture, smoke, and dust. All tend to

scatter light, which reduces an object’s brightness.

Transparency is judged by the magnitude of the faintest stars

you can see with the unaided eye (6th magnitude or fainter is

desirable).

How to Find Interesting Celestial Objects

To locate celestial objects with your telescope, you first need

to become reasonably familiar with the night sky. Unless you

know how to recognize the constellation Orion, for instance,

you won’t have much luck locating the Orion Nebula, unless,

or course, you look up its celestial coordinates and use the

telescope’s setting circles. Even then, it would be good to

know in advance whether that constellation will be above the

horizon at the time you plan to observe.A simple planisphere,

or star wheel, can be a valuable tool both f or learning the constellations and for determining which ones are visible on a

given night at a given time.

A good star chart or atlas will come in very handy for helping

find objects among the dizzying multitude of stars overhead.

Except for the Moon and the brighter planets, it’s pretty timeconsuming and frustrating to hunt for objects randomly,

without knowing where to look.You should have specific targets in mind before you begin observing.

Start with a basic star atlas, one that shows stars no fainter

than 5th or 6th magnitude. In addition to stars, the atlas will

show the positions of a number of interesting deep-sky objects,

with different symbols representing the different types of

objects, such as galaxies, open star clusters, globular clusters,

diffuse nebulas, and planetary nebulas. So, for example, your

atlas might show a globular cluster sitting just above the lid of

the “Teapot” pattern of stars in Sagittarius. You then know to

point your telescope in that direction to home in on the cluster,

which happens to be 6.9-magnitude Messier 28 (M28).

You can see a great number and variety of astronomical

objects with your Skywatcher 90 EQ, including:

The Moon

With its rocky, cratered surface, the Moon is one of the easiest and most interesting targets to view with your telescope.

The best time to observe our one and only natural satellite is

during a partial phase, that is, when the Moon is NOT full.

During partial phases, shadows on the surface reveal more

detail, especially right along the border between the dark and

light portions of the disk (called the “terminator”). A full Moon

is too bright and devoid of surface shadows to yield a pleasing view .Try using a Moon Filter (Orion part #5662) to dim the

Moon when it is very bright. It simply threads onto the bottom

of the eyepieces (you must first remo v e the e y epiece from the

star diagonal to attach the Moon filter).

The Planets

The planets don’t stay put like the stars (they don’t have fixed

R.A. and Dec. coordinates), so you’ll have to refer to charts

Page 9

9

published monthly in

Astronomy, Sky & Telescope

, or other

astronomy magazines to locate them. Venus, Mars, Jupiter,

and Saturn are the brightest objects in the sky after the Sun

and the Moon. Not all four of these planets are normally visible at any one time.

JUPITER The largest planet, Jupiter, is a great subject to

observe.You can see the disk of the giant planet and watch

the ever-changing positions of its four largest moons, Io,

Callisto, Europa, and Ganymede. If atmospheric conditions

are good, you may be able to resolve thin cloud bands on the

planet’s disk.

SATURN The ringed planet is a breathtaking sight when it is

well positioned.The tilt angle of the rings varies over a period

of many years; sometimes they are seen edge-on, while at

other times they are broadside and look like giant “ears” on

each side of Saturn’s disk. A steady atmosphere (good seeing) is necessary for a good view .Y ou ma y probab ly see a tin y,

bright “star” close by; that’s Saturn’s brightest moon, Titan.

VENUS At its brightest, Venus is the most luminous object in

the sky, excluding the Sun and the Moon. It is so bright that

sometimes it is visible to the naked eye during full daylight!

Ironically, Venus appears as a thin crescent, not a full disk,

when at its peak brightness.Because it is so close to the Sun,

it never wanders too far from the morning or evening horizon.

No surface markings can be seen on Venus, which is always

shrouded in dense clouds.

MARS If atmospheric conditions are good, you may be able

to see some subtle surface detail on the Red Planet, possibly

even the polar ice cap .Mars makes a close approach to Earth

every two years; during those approaches its disk is larger

and thus more favorable for viewing.

Stars

Stars will appear like twinkling points of light in the telescope.

Even powerful telescopes cannot magnify stars to appear as

more than points of light! You can, however, enjoy the different colors of the stars and locate many pretty double and

multiple stars. The famous “Double-Double” in the constellation Lyra and the gorgeous two-color double star Albireo in

Cygnus are favorites. Defocusing the image of a star slightly

can help bring out its color.

Deep-Sky Objects

Under dark skies, you can observe a wealth of fascinating

deep-sky objects, including gaseous nebulas, open and globular star clusters, and different types of galaxies.Most deep-sky

objects are very faint, so it is important that you find an observing site well away from light pollution.Take plenty of time to let

your eyes adjust to the darkness. Don’t expect these subjects

to appear like the photographs you see in books and magazines; most will look like dim gray smudges.(Our eyes are not

sensitive enough to see color in such faint objects.) But as you

become more experienced and your observing skills get

sharper, you will be able to discern more subtle details.

Remember that the higher the magnification you use, the dimmer the image will appear. So stick with low power when

observing deep-sky objects, because they’re already v ery faint.

Consult a star atlas or observing guide for information on finding and identifying deep-sky objects. A good source to star t

with is the Orion DeepMap 600 (part #4150).

7. Astrophotography

There are several diff erent types of astrophotogr aphy that can

be successfully attempted with the Skywatcher 90:

Moon Photography

This is perhaps the simplest form of astrophotography, as no

motor drive is required. All that is needed is a Universal 1.25"

Camera Adapter (part #5264) and a t-ring for your specific

camera. Connect the t-ring to your camera body, and then

connect the nosepiece of the camera adapter to the t-ring (the

body of the camera adapter is not needed).Insert the camera,

with the camera adapter attached, directly into the telescope’s

focuser drawtube (remove the star diagonal), and secure firmly with the setscrew on the drawtube.Make sure the setscrew

is tight, or your camera may fall to the ground!

Now you’re ready to shoot. Point the telescope toward the

Moon, and center it within the camera’s viewfinder.Focus the

image with the telescope’s focuser. Try several exposure

times, all less than 1 second, depending on the phase of the

Moon and the ISO (film speed) of the film being used. A

remote shutter release is recommended (part #5232), since

touching the camera’s shutter release can vibrate the camer a

enough to ruin the exposure.

This method of taking pictures is the same method with which

a daytime, terrestrial photograph could be taken through the

Skywatcher 90.

Planetary Photography

Once you’ve mastered basic Moon photography, you’re ready

to get images of the planets. This type of astrophotography

also may be used to capture highly magnified shots of the

Moon. In addition to the adapters already mentioned, the single-axis motor drive is also required.This is because a longer

exposure is necessary, which would cause the image to blur

if no motor drive were used for trac king.The equatorial mount

must be precisely polar aligned, too.

As before, connect the t-ring to your camera.Before connecting

the camera adapter to the t-ring, an eyepiece must now be

inserted and locked into the body of the camera adapter.Start

by using a medium-low power e y epiece (about 25mm);you can

increase the magnification later by using a higher-power eyepiece. Then connect the entire camera adapter, with eyepiece

inside, to the t-ring.Insert the whole system into the telescope’s

focuser drawtube and secure firmly with the setscrew.

Aim the telescope at the planet (or Moon) you wish to shoot.

The image will be highly magnified, so you may need to use

the finder scope to center it within the camera’s viewfinder.

Turn the motor drive on.Adjust the telescope’ s f ocuser so that

the image appears sharp.The camera’s shutter is now ready

to be opened. A remote shutter release must be used or the

image will be blurred beyond recognition! Try exposure times

between 1 and 10 seconds, depending on the brightness of

Page 10

10

the planet to be photographed and the ISO of the film being

used.

“Piggybacking” Photography

The Moon and planets are interesting targets for the budding

astrophotographer, but what’s next? Literally thousands of

deep-sky objects can be captured on film with a type of

astrophotography called “piggybacking.” The basic idea is that

a camera with its own camera lens attached rides on top of the

main telescope.The telescope and camera both move with the

rotation of the Earth when the mount is polar aligned and the

motor drive is engaged.This allows for a long exposure through

the camera without blurring of the object or background stars.

In addition to the motor drive, an illuminated reticle eyepiece is

also needed (Orion part #8481 is recommended). The t-r ing

and camera adapter are not needed, since the camera is

exposing through its own lens. Any camera lens with a focal

length between 50mm and 400mm is appropriate.

On the top of one of the tube rings is a piggyback camera

adapter. This is the black knob with the threaded shaft protruding through its center. The tube ring with the piggyback

adapter on it should be closest to the front of the telescope.

Remove the tube rings from the equatorial mount and swap

their positions, if necessary .Now, connect the camera to the piggyback adapter.There should be a 1/4"-20 mounting hole in the

bottom of the camera’s body.Thread the protruding shaft of the

piggyback adapter into the 1/4"-20 hole in the camera a few

turns.P osition the camera so that it is parallel with the telescope

tube and turn the knurled black knob of the piggyback adapter

counterclockwise until the camera is locked into position.

Aim the telescope at a deep-sky object. It should be a fairly

large deep-sky object, as the camera lens will likely have a

wide field of view. Check to make sure that the object is also

centered in the camera’s vie wfinder.T urn the motor drive on.Now,

look into the telescope’s eyepiece and center the brightest star

within the field of view. Remove the eyepiece and insert the illuminated reticle eyepiece into the telescope’s star diagonal. Turn

the eyepiece’s illuminator on (dimly!). Recenter the bright star

(guide star) on the crosshairs of the reticle eyepiece.Check again

to make sure the object to be photographed is still centered within the camera’s field of view. If it is not, recenter it either by

repositioning the camera on the piggyback adapter , or by mo ving

the main telescope.If you mov e the main telescope , then y ou will

need to recenter another guide star on the eyepiece’ s crosshairs .

Once the object is centered in the camera, and a guide star is

centered in the eyepiece, you’re ready to shoot.

Deep-sky objects are quite faint, and typically require exposures on the order of 10 minutes.T o hold the camera’s shutter

open this long, you will need a locking shutter release cable

(part #5231).You will also need to set the camera’s shutter to

the “B” (bulb) setting for the locking shutter release to work

properly. Depress the release cable and lock it.You are now

exposing your first deep-sky object.

While exposing through the camera lens, you will need to

monitor the accuracy of the mount’s tracking by looking

through the illuminated reticle eyepiece in the main telescope. If the guide star drifts from its initial position, then use

the hand controller of the motor drive to “bump”the guide star

back to the center of the crosshairs.The hand controller only

moves the telescope along the R.A.axis, which is where most

of the corrections will be made.If the guide star appears to be

drifting significantly along the Dec. axis, then the mount’s

slow-motion control cables can be carefully used to move the

guide star back onto the crosshairs. Any drifting along the

Dec. axis is due to imprecise polar alignment. If the drifting is

significant, you may need to polar align the mount more accurately.

When the exposure is complete, unlock the shutter release

cable and close the camera’s shutter.

Astrophotography can be enjo y ab le and rew arding, as w ell as

frustrating and time-consuming. Start slowly and consult outside resources, such as books and magazines, for more

details about astrophotography. Remember ...have fun!

8. Terrestrial Viewing

The Skywatcher 90 may also be used for long-distance viewing over land.F or this application we recommend substitution

of an Orion 45° Correct-Image Diagonal (#8790) for the 90°

star diagonal that comes standard with the telescope.The correct-image diagonal will yield an upright, non-reversed image

and also provides a more comfortable viewing angle, since the

telescope will be aimed more horizontally for terrestrial subjects.

For terrestrial viewing, it’ s best to stick with low powers of 50x

or less.At higher powers the image loses sharpness and clarity. That’s because when the scope is pointed near the

horizon, it is peering through the thickest and most turbulent

part of the Ear th’s atmosphere.

Remember to aim well clear of the Sun, unless the front of the

telescope is fitted with a professionally made solar filter and

the finder scope is covered with foil or some other completely opaque material.

9. Care and Maintenance

If you give your telescope reasonable care, it will last a lifetime. Store it in a clean, dry, dust-free place, safe from rapid

changes in temperature and humidity. Do not store the telescope outdoors, although storage in a garage or shed is OK.

Small components like eyepieces and other accessories

should be kept in a protective box or storage case. Keep the

cap on the front of the telescope when it is not in use.

Your Skywatcher 90 telescope requires very little mechanical

maintenance.The optical tube is aluminum and has a smooth

painted finish that is fairly scratch-resistant. If a scratch does

appear on the tube, it will not harm the telescope.If you wish,

you may apply some auto touch-up paint to the scratch.

Smudges on the tube can be wiped off with a soft cloth and a

household cleaner such as Windex or Formula 409.

Cleaning the Optics

A small amount of dust or a few specks on the glass objectiv e

(main) lens will not affect the performance of the telescope.If

dust builds up, however, simply blow it off with a blower bulb,

or lightly brush it off with a soft camel hair brush. Avoid touch-

Page 11

11

ing optical surfaces with your fingers, as skin oil may etch

optical coatings.

To remove fingerprints or smudges from a lens, use photographic-type lens cleaning fluid and lint-free optical lens

cleaning tissue. Do not use household cleaners or eyeglasstype cleaning cloth or wipes, as they often contain undesirable

additives like silicone, which don’t work well on precision

optics. Place a few drops of fluid on the tissue (not directly on

the lens), wipe gently, then remove the fluid with a dry tissue

or two.Do not “polish” or rub hard when cleaning the lens, as

this will scratch it.The tissue may leave fibers on the lens, but

this is not a problem;they can be blown off with a blower bulb.

Never disassemble the telescope or eyepieces to clean optical surfaces!

10. Specifications

Optical tube: Seamless aluminum

Objective lens diameter: 90mm (3.5")

Objective lens glass: crown and flint, achromat

Objective lens coating: fully coated with multi-coatings

Focal length: 910mm

Focal ratio: f/10

Eyepieces: 25mm and 10mm Kellner, fully coated, 1.25"

Magnification: 36x (with 25mm), 91x (with 10mm)

Focuser: Rack and pinion

Diagonal: 90° star diagonal, mirror type, 1.25"

Finder scope: 6x magnification, 30mm aper ture, achromatic,

crosshairs

Mount: German-type equator ial

Tripod: Aluminum

Motor drives: Optional

Page 12

12

Figure 2c. Preparing the telescope to be balanced on the

Dec. axis by first releasing the Dec. lock knob.

Figure 2d. Balancing the telescope with respect to the Dec.

axis. As shown here, the telescope is out of balance (tilting).

Figure 2e.Telescope is now balanced on the Dec. axis, i.e.,

it remains horizontal when hands are released.

Figure 2a. Balancing the telescope with respect to the R.A.

axis by sliding the counterweight along its shaft.

Figure 2b.Telescope is now balanced on the R.A. axis.That

is, when hands are released, counterweight shaft remains

horizontal.

Page 13

13

RIGHT ASCENSION AXIS

Declination (Dec.)

slow motion

control

Latitude adjustment t-bolt

Azimuth adjustment knob

R.A. lock knob

Declination (Dec.)

setting circle

Right ascension

(R.A.) setting circle

Right ascension

(R.A.) slow motion

control

Latitude locking

t-bolt

Latitude scale

Figure 3.The equatorial mount.

DECLINATION AXIS

Figure 4.

To find Polaris in the night sky, look north and find the Big Dipper. Extend an imaginary line from the two “Pointer Stars” in

the bowl of the Big Dipper.Go about five times the distance between those stars and you’ll reach Polaris, which lies within 1°

of the north celestial pole (NCP).

Big Dipper

(in Ursa Major)

Little Dipper

(in Ursa Minor)

N.C.P.

Pointer Stars

Cassiopeia

Polaris

Page 14

14

Figure 5a.Telescope pointing south. Note that in all these

illustrations, the mount and tripod remain stationary; only the

R.A. and Dec. axes are moved.

Figure 5b.Telescope pointing north.

Figure 5c.Telescope pointing east.

Figure 5d.Telescope pointing west.

Page 15

15

One-Year Limited Warranty

This Orion Skywatcher 90 EQ is warranted against defects in materials or workmanship for a

period of one year from the date of purchase.This warranty is for the benefit of the original retail

purchaser only. During this warranty period Orion Telescopes & Binoculars will repair or

replace, at Orion’s option, any warranted instrument that proves to be defective, provided it is

returned postage paid to: Orion Warranty Repair, 89 Hangar W ay, Watsonville, CA 95076.If the

product is not registered, proof of purchase (such as a copy of the original invoice) is required.

This warranty does not apply if, in Orion’s judgment, the instrument has been abused, mishandled, or modified, nor does it apply to normal wear and tear.This warranty gives you specific

legal rights, and you may also ha ve other rights, which vary from state to state.For further warranty service information, contact: Customer Service Department, Orion Telescopes &

Binoculars, P. O. Box 1815, Santa Cruz, CA 95061; (800) 676-1343.

Orion Telescopes & Binoculars

Post Office Box 1815, Santa Cruz, CA 95061

Customer Support Help Line (800) 676-1343 • Day or Evening

Page 16

During recent production of our Skywatcher 90 EQ (#9024),

Explorer 90 AZ (#9025), and ShortTube 80 (#9086) telescopes, we developed an improved design for the finder

scope bracket. The new design makes aiming the finder

scope much easier, since it requires adjustment to only two

alignment screws instead of three.As a result of this improvement, there are some discrepancies with the provided

instruction manuals. These discrepancies will be clarified in

this addendum.

#9024 Skywatcher 90 EQ

In the assembly section of the manual on page 4, line item

12 should now read:

12.To place the finder scope in the finder scope bracket, first

unthread the two adjustment screws until the screw ends

are flush with the inside diameter of the bracket.Place the

O-ring that comes on the base of the bracket over the

body of the finder scope until it seats into the slot on the

middle of the finder scope. Slide the eyepiece end (narrow end) of the finder scope into the end of the bracket’s

cylinder that does not have the adjustment screws while

pulling the spring-loaded tensioner on the bracket with

your fingers. Push the finder scope through the bracket

until the O-ring seats just inside the front opening of the

bracket’s cylinder.Now, release the tensioner and tighten

the adjustment screws a couple of turns each to secure

the finder scope in place.

Page 5 explains how to align the finder scope. The instructions are still valid, but to aim the finder scope, only

adjustments to the two alignment screws are needed. The

new finder scope bracket design also eliminates the need for

knurled lock nuts on the alignment screws.

Refer to Figure 1 to identify the parts of the new finder scope

bracket.

#9025 Explorer 90 AZ

In the assembly section of the manual on page 4, line item 9

should now read:

9. To place the finder scope in the finder scope bracket, first

unthread the two adjustment screws until the screw ends

are flush with the inside diameter of the bracket.Place the

O-ring that comes on the base of the bracket over the

body of the finder scope until it seats into the slot on the

middle of the finder scope. Slide the eyepiece end (narrow end) of the finder scope into the end of the bracket’s

cylinder that does not have the adjustment screws while

pulling the spring-loaded tensioner on the bracket with

your fingers. Push the finder scope through the bracket

until the O-ring seats just inside the front opening of the

bracket’s cylinder.Now, release the tensioner and tighten

the adjustment screws a couple of turns each to secure

the finder scope in place.

Pages 4 and 5 explain how to align the finder scope. The

instructions are still valid, but to aim the finder scope, only

adjustments to the two alignment screws are needed. The

new finder scope bracket design also eliminates the need for

knurled lock nuts on the alignment screws.

Refer to Figure 1 to identify the parts of the new finder scope

bracket.

#9086 ShortTube 80

The second paragraph in the section of the instructions entitled “Getting Started” should now read:

The optics have been installed and collimated at the factory,

so you should not have to make any adjustments to them.To

place the finder scope in the finder scope bracket, first

unthread the two adjustment screws until the screw ends are

flush with the inside diameter of the bracket.Place the O-ring

that comes on the base of the bracket over the body of the

finder scope until it seats into the slot on the middle of the

finder scope.Slide the ey epiece end (narrow end) of the finder scope into the end of the bracket’s cylinder that does not

have the adjustment screws while pulling the spring-loaded

tensioner on the bracket with your fingers. Push the finder

scope through the bracket until the O-ring seats just inside

the front opening of the bracket’s cylinder. Now, release the

tensioner and tighten the adjustment screws a couple of

turns each to secure the finder scope in place. Secure the

bracket to the “dovetail” mount on the optical tube with the

knurled set screw provided. Inser t the 45° diagonal into the

focuser tube and secure with the knurled set screw. Slide an

eyepiece into the diagonal and gently tighten the set screw.

The section in the manual entitled “Aligning the Finder

Scope” is still valid, but to aim the finder scope, only adjustments to the two alignment screws are needed.

Refer to Figure 1 to identify the parts of the finder scope bracket.

Providing Exceptional Consumer Optical Products Since 1975

Customer Support (800) 676-1343

E-mail: support@telescope.com

Corporate Offices (831) 763-7000

P.O. Box 1815, Santa Cruz, CA 95061

IN 135 Rev. A 1199

Improved Finder Scope Bracket

Addendum to the Instructions

#9024, 9025, 9086

Figure 1

O-ring (not pictured)

Alignment screws

Eyepiece end of

finder scope

Spring-loaded tensioner

Dovetail base

Loading...

Loading...