Page 1

Model HHG 21

Manual UN-01-244

April, 2001

Rev. A

OMEGA

All rights reserved.

GAUSS / TESLA METER

Instruction Manual

Page 2

This symbol appears on the instrument and probe. It

refers the operator to additional information

contained in this instruction manual, also identified

by the same symbol.

NOTICE:

See Pages 3-1 and 3-2

for SAFETY

instructions prior to first use!

Page 3

Table of Contents

SECTION-1 INTRODUCTION

Understanding Flux Density.............................................. 1-1

Measurement of Flux Density............................................ 1-2

Product Description........................................................... 1-5

Applications....................................................................... 1-6

SECTION-2 SPECIFICATIONS

Instrument......................................................................... 2-1

Standard Transverse Probe.............................................. 2-3

Standard Axial Probe........................................................ 2-4

Optional Probe Extension Cable....................................... 2-5

Zero Flux Chamber............................................................ 2-6

SECTION-3 OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS

Operator Safety................................................................. 3-1

Operating Features........................................................... 3-3

Instrument Preparation...................................................... 3-5

Power-Up.......................................................................... 3-7

Power-Up Settings............................................................ 3-8

Low Battery Condition....................................................... 3-9

Overrange Condition......................................................... 3-10

UNITS of Measure Selection............................................. 3-11

RANGE Selection.............................................................. 3-12

ZERO Function.................................................................. 3-13

Automatic ZERO Function................................................. 3-14

Manual ZERO Function..................................................... 3-16

Sources of Measurement Errors........................................ 3-18

WARRANTY....................................................................

4-1

i

Page 4

List of Illustrations

Figure 1-1 Flux Lines of a Permanent Magnet............ 1-1

Figure 1-2 Hall Generator............................................ 1-2

Figure 1-3 Hall Probe Configurations.......................... 1-4

Figure 2-1 Standard Transverse Probe....................... 2-3

Figure 2-2 Standard Axial Probe................................. 2-4

Figure 2-3 Optional Probe Extension Cable................ 2-5

Figure 2-4 Zero Flux Chamber.................................... 2-6

Figure 3-1 Auxiliary Power Connector Warnings......... 3-1

Figure 3-2 Probe Electrical Warning........................... 3-2

Figure 3-3 Operating Features.................................... 3-3

Figure 3-4 Battery Installation..................................... 3-5

Figure 3-5 Probe Connection...................................... 3-6

Figure 3-6 Power-Up Display...................................... 3-7

Figure 3-7 Missing Probe Indication............................ 3-8

Figure 3-8 Low Battery Indication................................ 3-9

Figure 3-9 Overrange Indication ................................ 3-10

Figure 3-10 UNITS Function.......................................... 3-11

Figure 3-11 RANGE Function....................................... 3-12

Figure 3-12 Automatic ZERO Function......................... 3-15

Figure 3-13 Manual ZERO Function.............................. 3-17

Figure 3-14 Probe Output versus Flux Angle................ 3-19

Figure 3-15 Probe Output versus Distance................... 3-19

Figure 3-16 Flux Density Variations in a Magnet........... 3-20

ii

Page 5

Section 1

Introduction

UNDERSTANDING FLUX DENSITY

Magnetic fields surrounding permanent magnets or electrical

conductors can be visualized as a collection of magnetic flux

lines; lines of force existing in the material that is being subjected

to a magnetizing influence. Unlike light, which travels away from

its source indefinitely, magnetic flux lines must eventually return

to the source. Thus all magnetic sources are said to have two

poles. Flux lines are said to emanate from the “north” pole and

return to the “south” pole, as depicted in Figure 1-1.

Figure 1-1

Flux Lines of a Permanent Magnet

One line of flux in the CGS measurement system is called a

maxwell (M

commonly used.

Flux density, also called magnetic induction, is the number of flux

lines passing through a given area. It is commonly assigned the

symbol “B” in scientific documents. In the CGS system a gauss

(G) is one line of flux passing through a 1 cm

), but the weber (Wb), which is 108 lines, is more

x

2

area. The more

1-1

Page 6

INTRODUCTION

commonly used term is the tesla (T), which is 10,000 lines per

2

. Thus

cm

1 tesla = 10,000 gauss

1 gauss = 0.0001 tesla

Magnetic field strength is a measure of force produced by an

electric current or a permanent magnet. It is the ability to induce

a magnetic field “B”. It is commonly assigned the symbol “H” in

scientific documents. It is important to know that magnetic field

strength and magnetic flux density are not

the same.

MEASUREMENT OF FLUX DENSITY

A device commonly used to measure flux density is the Hall

generator. A Hall generator is a thin slice of a semiconductor

material to which four leads are attached at the midpoint of each

edge, as shown in Figure 1-2.

1-2

Figure 1-2

Hall Generator

Page 7

INTRODUCTION

A constant current (Ic) is forced through the material. In a zero

magnetic field there is no voltage difference between the other

two edges. When flux lines pass through the material the path of

the current bends closer to one edge, creating a voltage

difference known as the Hall voltage (Vh). In an ideal Hall

generator there is a linear relationship between the number of

flux lines passing through the material (flux density) and the Hall

voltage.

The Hall voltage is also a function of the direction in which the

flux lines pass through the material, producing a positive voltage

in one direction and a negative voltage in the other. If the same

number of flux lines pass through the material in either direction,

the net result is zero volts.

The Hall voltage is also a function of the angle at which the flux

lines pass through the material. The greatest Hall voltage occurs

when the flux lines pass perpendicularly through the material.

Otherwise the output is related to the cosine of the difference

between 90° and the actual angle.

The sensitive area of the Hall generator is generally defined as

the largest circular area within the actual slice of the material.

This active area can range in size from 0.2 mm (0.008”) to 19

mm (0.75”) in diameter. Often the Hall generator assembly is too

fragile to use by itself so it is often mounted in a protective tube

and terminated with a flexible cable and a connector. This

assembly, known as a Hall probe, is generally provided in two

configurations:

1-3

Page 8

INTRODUCTION

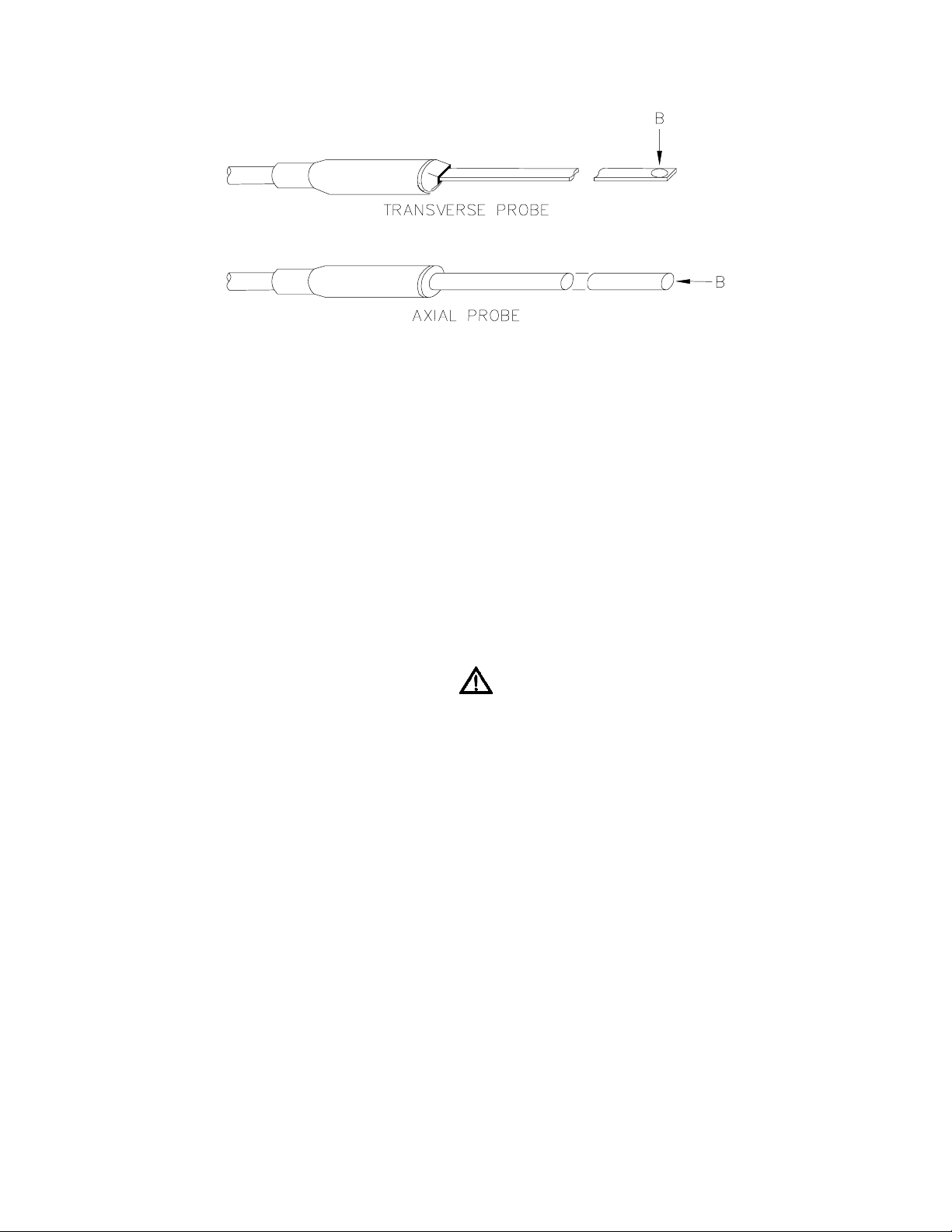

Figure 1-3

Hall Probe Configurations

In “transverse” probes the Hall generator is mounted in a thin, flat

stem whereas in “axial” probes the Hall generator is mounted in a

cylindrical stem. The axis of sensitivity is the primary difference,

as shown by “B” in Figure 1-3. Generally transverse probes are

used to make measurements between two magnetic poles such

as those in audio speakers, electric motors and imaging

machines. Axial probes are often used to measure the magnetic

field along the axis of a coil, solenoid or traveling wave tube.

Either probe can be used where there are few physical space

limitations, such as in geomagnetic or electromagnetic

interference surveys.

Handle the Hall probe with care. Do not bend the stem or

apply pressure to the probe tip as damage may result. Use

the protective cover when the probe is not in use.

1-4

Page 9

INTRODUCTION

PRODUCT DESCRIPTION

The MODEL HHG-21 GAUSS / TESLAMETER is a portable

instrument that utilizes a Hall probe to measure static (dc)

magnetic flux density in terms of gauss or tesla. The

measurement range is from 0.1 mT (1 G) to 1.999T (19.99 kG).

The MODEL HHG-21 consists of a palm-sized meter and various

detachable Hall probes. The meter operates on standard 9 volt

alkaline batteries or can be operated with an external ac-to-dc

power supply. A retractable bail allows the meter to stand upright

on a flat surface. A notch in the bail allows the meter to be wall

mounted when bench space is at a premium. The large display is

visible at considerable distances. The instrument is easily

configured using a single rotary selector and two pushbuttons.

Two measurement ranges can be selected. A “zero” function

allows the user to remove undesirable readings from nearby

magnetic fields (including earth’s) or false readings caused by

initial electrical offsets in the probe and meter. Included is a “zero

flux chamber” which allows the probe to be shielded from external

magnetic fields during this operation. The “zero” adjustment can

be made manually or automatically.

The meter, probes and accessories are protected when not in

use by a sturdy carrying case.

1-5

Page 10

INTRODUCTION

APPLICATIONS

• Sorting or performing incoming inspection on permanent

magnets, particularly multi-pole magnets.

•

Testing audio speaker magnet assemblies, electric motor

armatures and stators, transformer lamination stacks,

cut toroidal cores, coils and solenoids.

•

Determining the location of stray fields around medical

diagnostic equipment.

•

Determining sources of electromagnetic interference.

•

Locating flaws in welded joints.

•

Inspection of ferrous materials.

•

3-dimensional field mapping.

•

Inspection of magnetic recording heads.

1-6

Page 11

Section 2

Specifications

INSTRUMENT

RANGE RESOLUTION

gauss tesla Gauss tesla

2 kG 200 mT 1 G 0.1 mT

20 kG 2 T 10 G 1 mT

ACCURACY (including probe): ± 4 % of reading, ± 3 counts

ACCURACY CHANGE WITH

TEMPERATURE

(not including probe): ± 0.02 % / ºC typical

WARMUP TIME TO RATED

ACCURACY: 15 minutes

OPERATING TEMPERATURE: 0 to +50ºC (+32 to +122ºF)

STORAGE TEMPERATURE: -25 to +70ºC (-13 to +158ºF)

BATTERY TYPE: 9 Vdc alkaline (NEDA 1640A)

BATTERY LIFE: 8 hours typical (two batteries)

AUXILIARY POWER: 9 Vdc, 300 mA

AUXILIARY POWER CONNECTOR: Standard 2.5 mm I.D. / 5.5 mm

O.D. connector. Center post is

positive (+) polarity.

2-1

Page 12

SPECIFICATIONS

METER DIMENSIONS:

Length: 13.2 cm (5.2 in)

Width: 13.5 cm (5.3 in)

Height: 3.8 cm (1.5 in)

WEIGHT:

Meter w/batteries: 400 g (14 oz.)

Shipping: 1.59 kg (3 lb., 8 oz.)

REGULATORY INFORMATION:

Compliance was demonstrated to the following specifications as

listed in the official Journal of the European Communities:

EN 50082-1:1992 Generic Immunity

IEC 801-2:1991 Electrostatic Discharge

Second Edition Immunity

IEC 1000-4-2:1995

ENV 50140:1993 Radiated Electromagnetic

IEC 1000-4-3:1995 Field Immunity

EN 50081-1:1992 Generic Emissions

EN 55011:1991 Radiated and Conducted

Emissions

2-2

Page 13

SPECIFICATIONS

STANDARD TRANSVERSE PROBE

MODEL NUMBER: HTV56-0602

FLUX DENSITY RANGE: 0 to ± 2 T (0 to ± 20 kG)

FREQUENCY BANDWIDTH: dc only

OFFSET CHANGE WITH

TEMPERATURE: ± 30 µT (300 mG) / ºC typical

ACCURACY CHANGE WITH

TEMPERATURE: - 0.05% / ºC typical

OPERATING TEMPERATURE RANGE: 0 to +75 ºC (+32 to +167ºF)

STORAGE TEMPERATURE RANGE: -25 to +75 ºC (-13 to +167ºF)

Figure 2-1

Standard Transverse Probe

2-3

Page 14

SPECIFICATIONS

STANDARD AXIAL PROBE

MODEL NUMBER: SAV56-1904

FLUX DENSITY RANGE: 0 to ± 2 T (0 to ± 20 kG)

OFFSET CHANGE WITH

TEMPERATURE: ± 30 µT (300 mG) / ºC typical

ACCURACY CHANGE WITH

TEMPERATURE: - 0.05% / ºC typical

FREQUENCY BANDWIDTH: dc only

OPERATING TEMPERATURE RANGE: 0 to +75 ºC (+32 to +167ºF)

STORAGE TEMPERATURE RANGE: -25 to +75 ºC (-13 to +167ºF)

2-4

Figure 2-2

Standard Axial Probe

Page 15

SPECIFICATIONS

OPTIONAL PROBE EXTENSION CABLE

MODEL NUMBER: X5000-0006

OPERATING TEMPERATURE RANGE: 0 to +75 ºC (+32 to +167ºF)

STORAGE TEMPERATURE RANGE: -25 to +75 ºC (-13 to +167ºF)

Figure 2-3

Optional Probe Extension Cable

2-5

Page 16

SPECIFICATIONS

ZERO FLUX CHAMBER

MODEL NUMBER: YA-111

CAVITY DIMENSIONS:

Length: 50.8 mm (2”)

Diameter: 8.7 mm (0.343”)

ATTENUATION: 80 dB to 30 mT (300 G)

PURPOSE: To shield the probe from

external magnetic fields during

the ZERO operation.

2-6

Figure 2-4

Zero Flux Chamber

Page 17

Section 3

Operating Instructions

OPERATOR SAFETY

Do not connect the auxiliary power connector to an ac power

source. Do not exceed 15 Vdc regulated or 9 Vdc

unregulated. Do not reverse polarity. Use only an ac-to-dc

power supply certified for country of use.

Figure 3-1

Auxiliary Power Connector Warnings

3-1

Page 18

OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS

Do not allow the probe to come in contact with any voltage

source greater than 30 Vrms or 60 Vdc.

Figure 3-2

Probe Electrical Warning

This instrument may contain ferrous components which will

exhibit attraction to a magnetic field. Care should be utilized

when operating the instrument near large magnetic fields, as

pull-in may occur. Extension cables are available to increase

the probe cable length, so that the instrument can remain in a

safe position with respect to the field being measured with

the probe.

3-2

Page 19

OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS

OPERATING FEATURES

Figure 3-3

Operating Features

1 Display. Liquid crystal display (LCD).

2 Manual ZERO Control. In the ZERO mode of operation

the user can manually adjust the zero point using this

control.

3 Function Selector. This control allows the operator to

change the meter’s range and units of measure. It also

engages the ZERO and MEASURE modes of operation.

4 Battery Compartment Cover. This cover slides open to

allow one or two 9 volt batteries to be installed.

5 Power Switch. Push-on / push-off type switch to apply

power to the meter.

6 SELECT Switch. Momentary pushbutton used in

conjunction with the Function Selector 3 to configure

the meter’s range and units of measure.

3-3

Page 20

OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS

7 AUTO Switch. Momentary pushbutton used to start an

automatic ZERO operation when in the ZERO mode.

8 Auxiliary Power Connector. This is an industry standard

2.5 mm I.D. / 5.5 mm O.D. dc power connector. The

meter will accept a regulated dc voltage in the range of 6 15 Vdc at 300 mA minimum current or unregulated 9Vdc.

The center pin is positive (+). The internal batteries are

disconnected when using this connector.

Do not connect the auxiliary power connector to an ac power

source. Do not exceed 15 Vdc regulated or 9Vdc

unregulated. Do not reverse polarity. Use only an ac-to-dc

power supply certified for country of use.

9 Probe Connector. The Hall probe or probe extension

cable plugs into this connector and locks in place. To

disconnect, pull on the body of the plug, not the cable

!

10 Meter Stand. Retractable stand that allows the meter to

stand upright when placed on a flat surface. A notch in

the stand allows the meter to be mounted to a vertical

surface.

3-4

Page 21

OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS

INSTRUMENT PREPARATION

1) With the power switch turned off (POWER pushbutton in the

full up position) apply pressure to the battery compartment cover

at the two points shown in Figure 3-4. Slide the cover open and

remove.

2) Install one or two 9 volt alkaline batteries (two batteries will

provide longer operating life). The battery compartment is

designed so that the battery polarity cannot be reversed.

Reinstall the battery compartment cover.

Figure 3-4

Battery Installation

3-5

Page 22

OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS

3) If using an ac-to-dc power supply review Figure 3-1 for safety

notes and the SPECIFICATIONS section for voltage and current

ratings. When using a power supply the batteries are

automatically disconnected.

4) Install the probe or probe extension cable by matching the key

way in the connector to that in the mating socket in the meter.

The connector will lock in place. To disconnect, pull on the body

of the plug, not the cable!

Figure 3-5

Probe Connection

3-6

Page 23

OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS

POWER-UP

Depress the POWER switch. There will be a momentary audible

beep and all display segments will appear on the display.

Figure 3-6

Power-Up Display

The instrument will conduct a self test before measurements

begin. If a problem is detected the phrase “Err” will appear on the

display followed by a 3-digit code. The circuitry that failed will be

retested and the error code will appear after each failure. This

process will continue indefinitely or until the circuitry passes the

test. A condition in which a circuit fails and then passes should

not be ignored because it indicates an intermittent problem that

should be corrected.

If the self test is successful the meter will perform a self

calibration. During this phase the meter will display the software

revision number, such as “r 1.0”. Calibration will halt if there is no

Hall probe connected. Until the probe is connected the phrase

“Err” will appear accompanied by a flashing “PROBE” annunciator

as shown in Figure 3-7.

3-7

Page 24

OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS

Figure 3-7

Missing Probe Indication

After power-up the position of the FUNCTION selector switch will

determine what happens next. For instance if the selector is in

the RANGE position the meter will wait for the user to change the

present range. If in the MEASURE position flux density

measurements will begin.

Allow adequate time for the meter and probe to reach a stable

temperature. See the SPECIFICATIONS section for specific

information.

POWER-UP SETTINGS

The meter permanently saves certain aspects of the instrument’s

setup and restores them the next time the meter is turned on.

The conditions that are saved are:

RANGE setting

UNITS of measure (gauss or tesla)

Other aspects are not

saved and default to these conditions:

ZERO mode (inactive)

3-8

Page 25

OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS

NOTE: The present setup of the instrument is saved only when

the FUNCTION selector is returned to the MEASURE position.

For example assume the meter is in the MEASURE mode on the

200 mT range. The FUNCTION selector is now turned to the

RANGE position and the 2 T range is selected. The meter is

turned off and on again. The meter will be restored to the 200

mT range because the FUNCTION selector was never returned

to the MEASURE mode prior to turning it off.

LOW BATTERY CONDITION

The meter is designed to use one or two standard 9V alkaline

batteries (two batteries will provide longer operating life). When

the battery voltage becomes too low the battery symbol on the

display will flash, as shown in Figure 3-8. Replace the batteries

or use an external ac-to-dc power supply.

Instrument specifications are not guaranteed when a low

battery condition exists !

Figure 3-8

Low Battery Indication

3-9

Page 26

OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS

OVERRANGE CONDITION

If the magnitude of the magnetic flux density exceeds the limit of

the selected range the meter will display a flashing value of

“1999”. The next highest range should be selected. If already on

the highest range then the flux density is too great to be

measured with this instrument.

Figure 3-9

Overrange Indication

3-10

Page 27

OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS

UNITS OF MEASURE SELECTION

The meter is capable of providing flux density measurements in

terms of gauss (G) or tesla (T). To choose the desired units,

rotate the function selector to the UNITS position. Press the

SELECT pushbutton to select G or T on the display.

This setting is saved and will be restored the next time the meter

is turned on.

Figure 3-10

UNITS Function

3-11

Page 28

OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS

RANGE SELECTION

The meter is capable of providing flux density measurements on

one of two fixed ranges. The available ranges are listed in the

SPECIFICATIONS section of this manual. The ranges advance

in decade steps. The lowest range offers the best resolution

while the highest range allows higher flux levels to be measured.

To choose the desired range rotate the function selector to the

RANGE position. The “RANGE” legend will flash. Press the

SELECT pushbutton to select the desired range on the display.

This setting is saved and will be restored the next time the meter

is turned on.

3-12

Figure 3-11

RANGE Function

Page 29

OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS

ZERO FUNCTION

“Zeroing” the probe and meter is one of the most important steps

to obtaining accurate dc flux density measurements. The ideal

Hall generator produces zero output in the absence of a magnetic

field, but actual devices are subject to variations in materials,

construction and temperature. Therefore most Hall generators

produce some output even in a zero field. This will be interpreted

by the meter as a flux density signal.

Also, the circuits within the meter can produce a signal even

when there is no signal present at the input. This will be

interpreted as a flux density signal. Lastly magnetic sources

close to the actual field being measured, such as those from

electric motors, permanent magnets and the earth (roughly 0.5

gauss or 50 µT), can induce errors in the final reading.

It is vital to remove these sources of error prior to making actual

measurements. The process of “zeroing” removes all of these

errors in one operation. The meter cancels the combined dc

error signal by introducing another signal of equal magnitude with

opposite polarity. After zeroing the only dc signal that remains is

that produced by the probe when exposed to magnetic flux.

NOTE: Zeroing the meter and probe affects only

the static (dc)

component of the flux density signal.

There may be situations when the user prefers to shield the

probe from all external magnetic fields prior to zeroing. Provided

with the meter is a ZERO FLUX CHAMBER which is capable of

shielding against fields as high as 30 mT (300 G). The probe is

simply inserted into the chamber before the zeroing process

begins.

3-13

Page 30

OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS

Handle the Hall probe with care. Do not bend the stem or

apply pressure to the probe tip as damage may result.

In other situations the user may want the probe to be exposed to

a specific magnetic field during the zeroing process so that all

future readings do not include that reading (such as the earth’s

field). This is possible with the following restrictions:

1) The external field must not exceed 30 mT (300 G).

2) The field must be stable during the zeroing process. It should

not contain alternating (ac) components.

AUTOMATIC ZERO FUNCTION

The meter provides two methods to zero the probe. The first is

completely automatic. Prepare the probe for zeroing, then rotate

the function selector to the ZERO position. The “ZERO” legend

will flash and actual dc flux density readings will appear on the

display. The meter will select the lowest range regardless of

which range was in use prior to using the ZERO function. Recall

that the maximum flux density level that can be zeroed is 30 mT

(300 G).

3-14

Page 31

OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS

Figure 3-12

Automatic ZERO Function

Press the AUTO pushbutton and the process will begin. The

“AUTO” legend will also flash. Once automatic zeroing begins it

must be allowed to complete. During this time all controls are

disabled except for the POWER switch. The process normally

takes from 5 to 15 seconds.

The meter selects the lowest range and adjusts the nulling signal

until the net result reaches zero. If the existing field is too large

or unstable the meter will sound a double beep and the phrase

“OVER” will appear momentarily on the display. At this point the

automatic process is terminated and the flashing “AUTO” legend

will disappear. The “ZERO” legend will continue to flash to

remind the user that the ZERO mode is still active.

3-15

Page 32

OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS

If the nulling process is successful, the highest range is selected.

No further electronic adjustments are made, but at this stage a

reading is acquired which will be mathematically subtracted from

all future readings on this range. When finished, the meter will

sound an audible beep and the flashing “AUTO” legend will

disappear. The “ZERO” legend will continue to flash to remind

the user that the ZERO mode is still active. At this point the

automatic process can be repeated or a manual adjustment can

be performed (see “Manual Zero Function”).

The final zero values will remain in effect until the meter and

probe are zeroed again, if the probe is disconnected or if the

meter is turned off and back on again.

MANUAL ZERO FUNCTION

The second zeroing method is a manual adjustment. This

feature also allows the user to set the “zero” point to something

other than zero, if desired. Position the probe for zeroing, then

rotate the function selector to the ZERO position. The “ZERO”

legend will flash and actual dc flux density readings will appear

on the display. The meter will select the lowest range regardless

of which range was in use prior to selecting the ZERO function.

Recall that the maximum flux density level that can be zeroed is

30 mT (300 G).

3-16

Page 33

OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS

Figure 3-13

Manual ZERO Function

By turning the MANUAL control in either direction the reading will

be altered. Turning the control clockwise adds to the reading,

turning it counterclockwise subtracts from the reading. Turning it

slowly results in a fine adjustment, turning it quickly results in a

coarse adjustment.

NOTE: Making a manual ZERO adjustment not only affects the

lowest range but also the highest range, though to a lesser

extent. For example, assume an automatic ZERO has already

been performed, after which both ranges should read zero. Now

a manual adjustment is made that causes the reading on the

lowest range to be non-zero. The reading on the other range

may also be non-zero depending upon the magnitude of the

3-17

Page 34

OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS

change. The adjustment has 10 times less effect on the highest

range.

SOURCES OF MEASUREMENT ERRORS

When making flux density measurements there are several

conditions that can introduce errors:

1) Operating the meter while the LOW BATTERY symbol

appears.

Instrument specifications are not guaranteed when a low

battery condition exists !

2) Failure to zero the error signals from the meter, probe and

nearby sources of magnetic interference.

3) Subjecting the probe to physical abuse.

Handle the Hall probe with care. Do not bend the stem or

apply pressure to the probe tip as damage may result. Use

the protective cover when the probe is not in use.

4) One of the most common sources of error is the angular

position of the probe with respect to the field being measured.

As mentioned in Section-1, a Hall generator is not only sensitive

to the number of flux lines passing through it but also the angle at

which they pass through it. The Hall generator produces the

greatest signal when the flux lines are perpendicular to the

sensor as shown in Figure 3-14.

3-18

Page 35

OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS

Figure 3-14

Probe Output versus Flux Angle

The probe is calibrated and specified with flux lines passing

perpendicularly through the Hall generator.

5) As shown in Figure 3-15 the greater the distance between the

magnetic source and the Hall probe the fewer flux lines will pass

through the probe, causing the probe’s output to decrease.

Figure 3-15

Probe Output versus Distance

6) Flux density can vary considerably across the pole face of a

permanent magnet. This can be caused by internal physical

flaws such as hairline cracks or bubbles, or an inconsistent mix of

3-19

Page 36

OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS

materials. Generally the sensitive area of a Hall generator is

much smaller than the surface area of the magnet, so the flux

density variations are very apparent. Figure 3-16 illustrates this

situation.

Figure 3-16

Flux Density Variations in a Magnet

7) Using more than one extension cable can result in

measurement errors. In some cases the meter may report an

error. Total cable length between the meter and the probe

connector should not exceed 2.1 m (7 ft).

The use of more than one extension cable can result in

measurement errors and increase susceptibility to radio

frequency interference (RFI).

8) The accuracies of the probe and meter are affected by

temperature changes. Refer to the SPECIFICATIONS section for

specific information.

3-20

Page 37

WARRANTY

This instrument is warranted to be free of defects in material and workmanship.

MANUFACTURER’s obligation under this warranty is limited to servicing or

adjusting any instrument returned to the factory for that purpose, and to replace

any defective parts thereof. This warranty covers instruments which, within one

year after delivery to the original purchaser, shall be returned with transportation

charges prepaid by the original purchaser, and which upon examination shall

disclose to MANUFACTURER’s satisfaction to be defective. If it is determined

that the defect has been caused by misuse or abnormal conditions of operation,

repairs will be billed at cost after submitting an estimate to the purchaser.

MANUFACTURER reserves the right to make changes in design at any time

without incurring any obligation to install same on units previously purchased.

THE ABOVE WARRANTY IS EXPRESSLY IN LIEU OF ALL OTHER

WARRANTIES EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED AND ALL OTHER OBLIGATIONS

AND LIABILITIES ON THE PART OF MANUFACTURER, AND NO PERSON

INCLUDING ANY DISTRIBUTOR, AGENT OR REPRESENTATIVE OF

MANUFACTURER IS AUTHORIZED TO ASSUME FOR MANUFACTURER’S

ANY LIABILITY ON ITS BEHALF OR ITS NAME, EXCEPT TO REFER THE

PURCHASER TO THIS WARRANTY. THE ABOVE EXPRESS WARRANTY IS

THE ONLY WARRANTY MADE BY MANUFACTURER. MANUFACTURER

DOES NOT MAKE AND EXPRESSLY DISCLAIMS ANY OTHER

WARRANTIES, EITHER EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING WITHOUT

LIMITING THE FOREGOING, WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR

FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE OR ARISING BY STATUE OR

OTHERWISE IN LAW OR FROM A COURSE OF DEALING OR USAGE OR

TRADE. THE EXPRESS WARRANTY STATED ABOVE IS MADE IN LIEU OF

ALL LIABILITIES FOR DAMAGES, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES, LOST PROFITS OR THE LIKE ARISING OUT

OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE SALE, DELIVERY, USE OR

PERFORMANCE OF THE GOODS. IN NO EVENT WILL MANUFACTURER’S

BE LIABLE FOR SPECIAL, INDIRECT OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES

EVEN IF MANUFACTURER’S HAS BEEN ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF

SUCH DAMAGES.

This warranty gives you specific legal rights, and you may also have other rights

that vary from state to state.

4-1

Loading...

Loading...