Page 1

SUSE Linux Enterprise

www.novell.com10 SP1

May08,2008 The Linux Audit Framework

Page 2

The Linux Audit Framework

All content is copyright © Novell, Inc.

Legal Notice

This manual is protected under Novell intellectual property rights. By reproducing, duplicating or

distributing this manual you explicitly agree to conform to the terms and conditions of this license

agreement.

This manual may be freely reproduced, duplicated and distributed either as such or as part of a bundled

package in electronic and/or printed format, provided however that the following conditions are fullled:

That this copyright notice and the names of authors and contributors appear clearly and distinctively

on all reproduced, duplicated and distributed copies. That this manual, specically for the printed

format, is reproduced and/or distributed for noncommercial use only. The express authorization of

Novell, Inc must be obtained prior to any other use of any manual or part thereof.

For Novell trademarks, see the Novell Trademark and Service Mark list http://www.novell

.com/company/legal/trademarks/tmlist.html. * Linux is a registered trademark of

Linus Torvalds. All other third party trademarks are the property of their respective owners. A trademark

symbol (®, ™ etc.) denotes a Novell trademark; an asterisk (*) denotes a third party trademark.

All information found in this book has been compiled with utmost attention to detail. However, this

does not guarantee complete accuracy. Neither Novell, Inc., SUSE LINUX Products GmbH, the authors,

nor the translators shall be held liable for possible errors or the consequences thereof.

Page 3

Contents

About This Guide v

1 Understanding Linux Audit 1

1.1 Introducing the Components of Linux Audit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

1.2 Conguring the Audit Daemon . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

1.3 Controlling the Audit System Using auditctl . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

1.4 Passing Parameters to the Audit System . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

1.5 Understanding the Audit Logs and Generating Reports . . . . . . . . . 15

1.6 Querying the Audit Daemon Logs with ausearch . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

1.7 Analyzing Processes with autrace . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

1.8 Visualizing Audit Data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

2 Setting Up the Linux Audit Framework 35

2.1 Determining the Components to Audit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

2.2 Conguring the Audit Daemon . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

2.3 Enabling Audit for System Calls . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

2.4 Setting Up Audit Rules . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39

2.5 Adjusting the PAM Conguration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

2.6 Conguring Audit Reports . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

2.7 Conguring Log Visualization . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

3 Introducing an Audit Rule Set 47

3.1 Adding Basic Audit Conguration Parameters . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

3.2 Adding Watches on Audit Log Files and Conguration Files . . . . . . . 49

3.3 Monitoring File System Objects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50

3.4 Monitoring Security Conguration Files and Databases . . . . . . . . . 51

3.5 Monitoring Miscellaneous System Calls . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54

Page 4

3.6 Filtering System Call Arguments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54

3.7 Managing Audit Event Records Using Keys . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 57

4 Useful Resources 59

A Creating Flow Graphs from the Audit Statistics 61

B Creating Bar Charts from the Audit Statistics 65

Page 5

About This Guide

The Linux audit framework as shipped with this version of SUSE Linux Enterprise

provides a CAPP-compliant auditing system that reliably collects information about

any security-relevant events. The audit records can be examined to determine whether

any violation of the security policies has been committed and by whom.

Providing an audit framework is an important requirement for a CC-CAPP/EAL certication. Common Criteria (CC) for Information Technology Security Information is

an international standard for independent security evaluations. Common Criteria helps

customers judge the security level of any IT product they intend to deploy in missioncritical setups.

Common Criteria security evaluations have two sets of evaluation requirements, functional and assurance requirements. Functional requirements describe the security attributes of the product under evaluation and are summarized under the Controlled Access

Protection Proles (CAPP). Assurance requirements are summarized under the Evaluation Assurance Level (EAL). EAL describes any activities that must take place for the

evaluators to be condent that security attributes are present, effective, and implemented.

Examples for activities of this kind include documenting the developers' search for security vulnerabilities, the patch process, and testing.

This guide provides a basic understanding of how audit works and how it can be set

up. For more information about Common Criteria itself, refer to the Common Criteria

Web site [http://www.commoncriteria-portal.org].

This guide contains the following:

Understanding Linux Audit

Get to know the different components of the Linux audit framework and how they

interact with each other. Refer to this chapter for detailed background information.

Setting Up the Linux Audit Framework

Follow the instructions to set up an example audit conguration from start to nish.

If you need a quick start document to get you started with audit, this chapter is it.

If you need background information about audit, refer to Chapter 1, Understanding

Linux Audit (page 1) and Chapter 3, Introducing an Audit Rule Set (page 47).

Page 6

Introducing an Audit Rule Set

Learn how to create an audit rule set that matches your needs by analyzing an example rule set.

Useful Resources

Check additional online and system information resources for more details on audit.

1 Feedback

We want to hear your comments and suggestions about this manual and the other documentation included with this product. Please use the User Comments feature at the

bottom of each page of the online documentation and enter your comments there.

2 Documentation Updates

For the latest version of this documentation, see the SLES 10 SP1 doc Web site

[http://www.novell.com/documentation/sles10].

3 Documentation Conventions

The following typographical conventions are used in this manual:

• /etc/passwd: lenames and directory names

• placeholder: replace placeholder with the actual value

• PATH: the environment variable PATH

• ls, --help: commands, options, and parameters

• user: users or groups

•

Alt, Alt + F1: a key to press or a key combination; keys are shown in uppercase as

on a keyboard

•

File, File > Save As: menu items, buttons

vi The Linux Audit Framework

Page 7

• ►amd64 ipf: This paragraph is only relevant for the specied architectures. The

arrows mark the beginning and the end of the text block.◄

►ipseries s390 zseries: This paragraph is only relevant for the specied architectures. The arrows mark the beginning and the end of the text block.◄

•

Dancing Penguins (Chapter Penguins, ↑Another Manual): This is a reference to a

chapter in another manual.

About This Guide vii

Page 8

Page 9

Understanding Linux Audit

Linux audit helps make your system more secure by providing you with a means to

analyze what is going on on your system in great detail. It does not, however, provide

additional security itself—it does not protect your system from code malfunctions or

any kind of exploits. Instead, Audit is useful for tracking these issues and helps you

take additional security measures, like Novell AppArmor, to prevent them.

Audit consists of several components, each contributing crucial functionality to the

overall framework. The audit kernel module intercepts the system calls and records the

relevant events. The auditd daemon writes the audit reports to disk. Various command

line utilities take care of displaying, querying, and archiving the audit trail.

Audit enables you to do the following:

Associate Users with Processes

Audit maps processes to the user ID that started them. This makes it possible for

the administrator or security ofcer to exactly trace which user owns which process

and is potentially doing malicious operations on the system.

IMPORTANT: Renaming User IDs

Audit does not handle the renaming of UIDs. Therefore avoid renaming

UIDs (for example, changing tux from uid=1001 to uid=2000) and

obsolete UIDs rather than renaming them. Otherwise you would need to

change auditctl data (audit rules) and would have problems retrieving old

data correctly.

1

Understanding Linux Audit 1

Page 10

Review the Audit Trail

Linux audit provides tools that write the audit reports to disk and translate them

into human readable format.

Review Particular Audit Events

Audit provides a utility that allows you to lter the audit reports for certain events

of interest. You can lter for:

• User

• Group

• Audit ID

• Remote Hostname

• Remote Host Address

• System Call

• System Call Arguments

• File

• File Operations

• Success or Failure

Apply a Selective Audit

Audit provides the means to lter the audit reports for events of interest and also

to tune audit to record only selected events. You can create your own set of rules

and have the audit daemon record only those of interest to you.

Guarantee the Availability of the Report Data

Audit reports are owned by root and therefore only removable by root. Unauthorized users cannot remove the audit logs.

Prevent Audit Data Loss

If the kernel runs out of memory, the audit daemon's backlog is exceeded, or its

rate limit is exceeded, audit can trigger a shutdown of the system to keep events

from escaping audit's control. This shutdown would be an immediate halt of the

system triggered by the audit kernel component without any syncing of the latest

2 The Linux Audit Framework

Page 11

logs to disk. The default conguration is to log a warning to syslog rather than to

kernel

audit

auditd

auditd.conf

auditctl

audit.rules

audit.log

audispd

autrace

aureport

ausearch

application

halt the system.

If the system runs out of disk space when logging, the audit system can be congured to perform clean shutdown (init 0). The default conguration tells the audit

daemon to stop logging when it runs out of disk space.

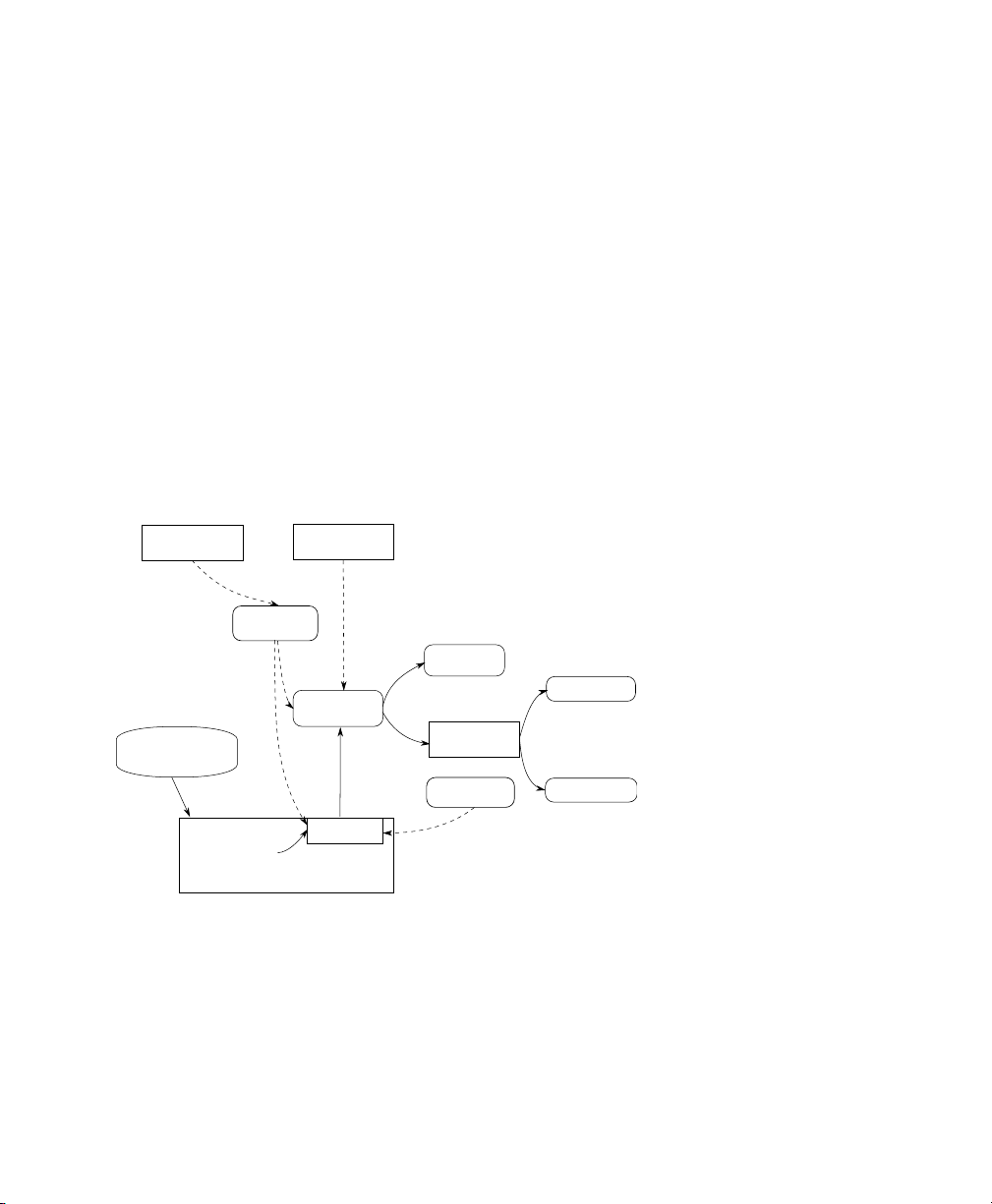

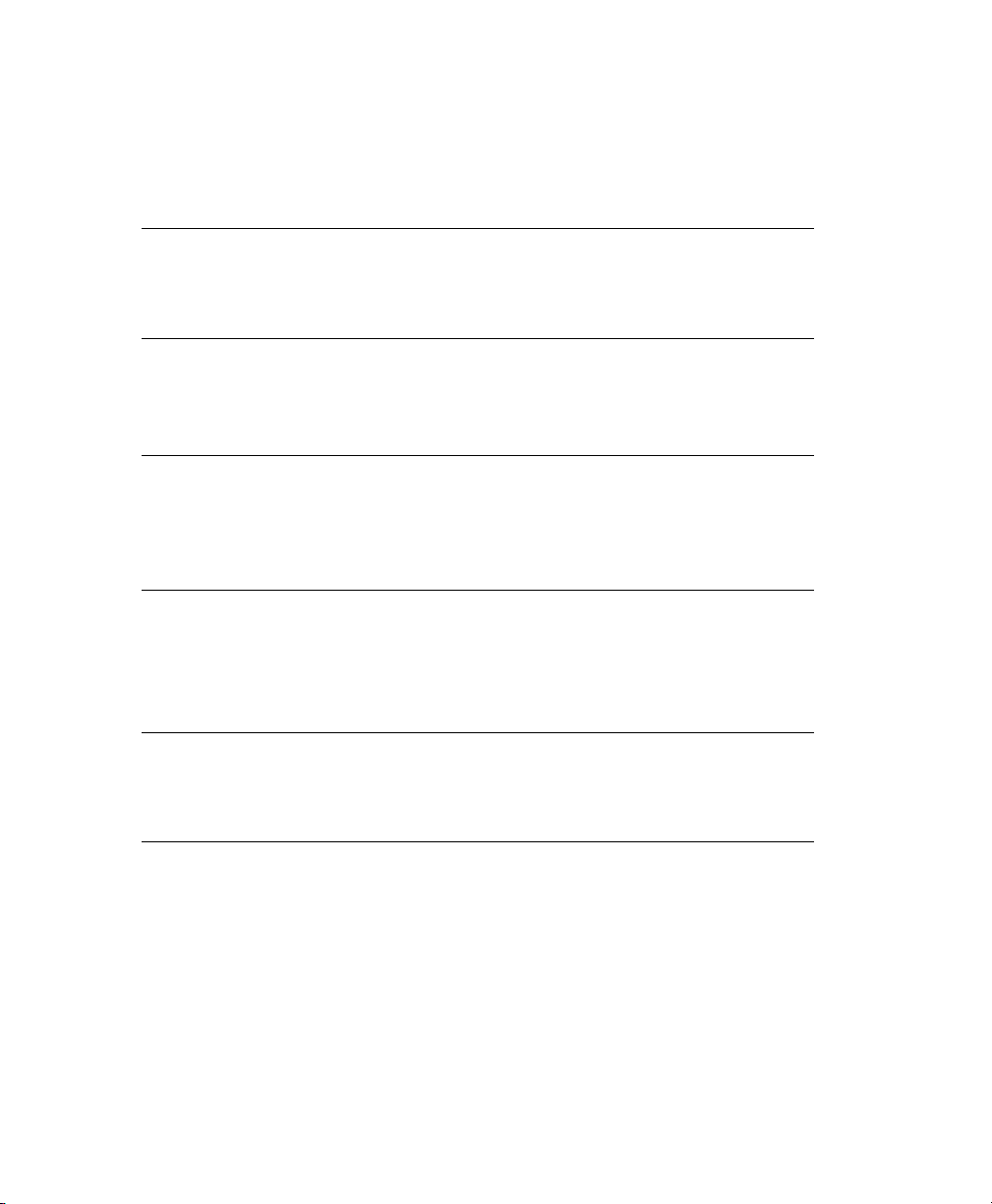

1.1 Introducing the Components of

Linux Audit

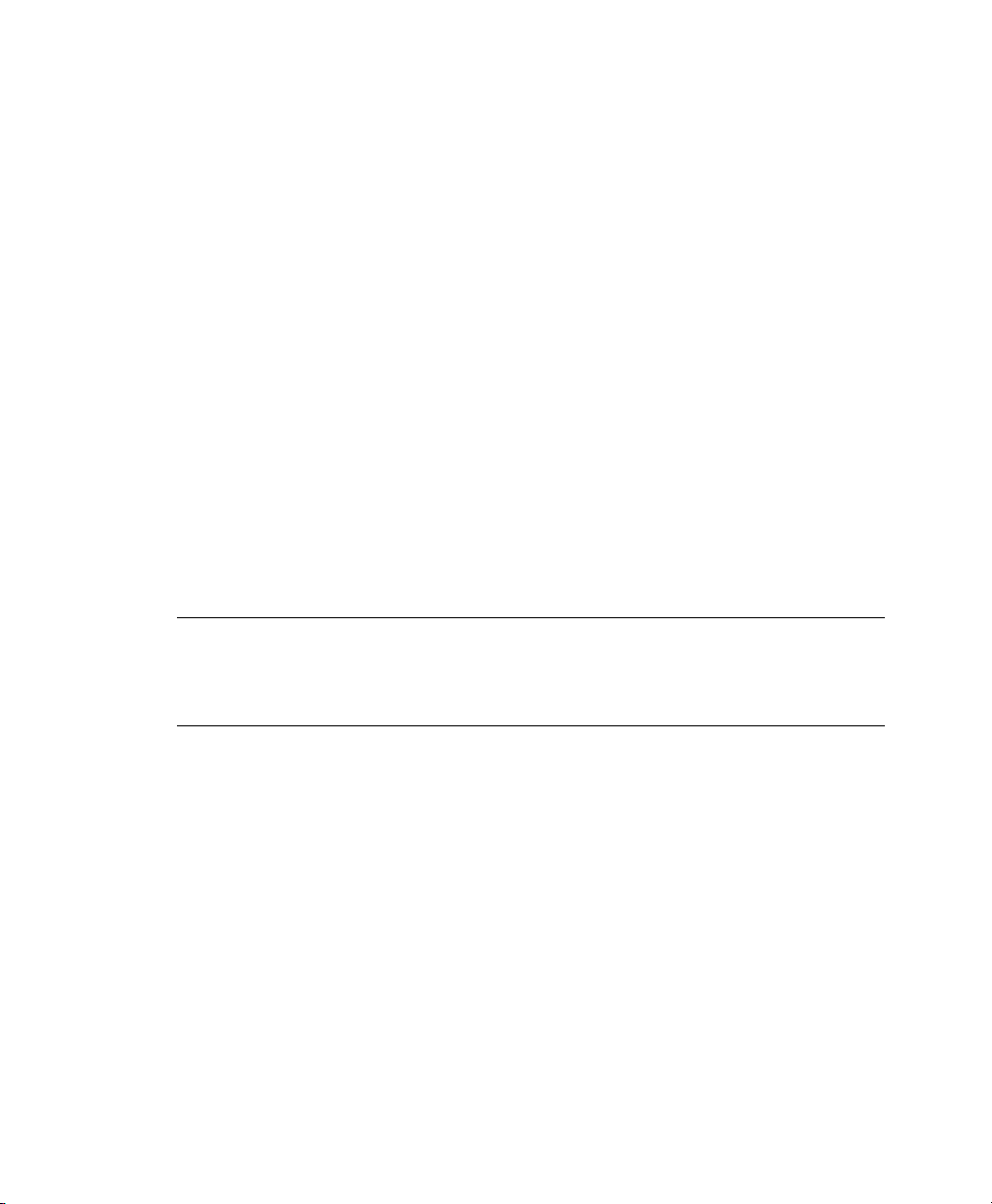

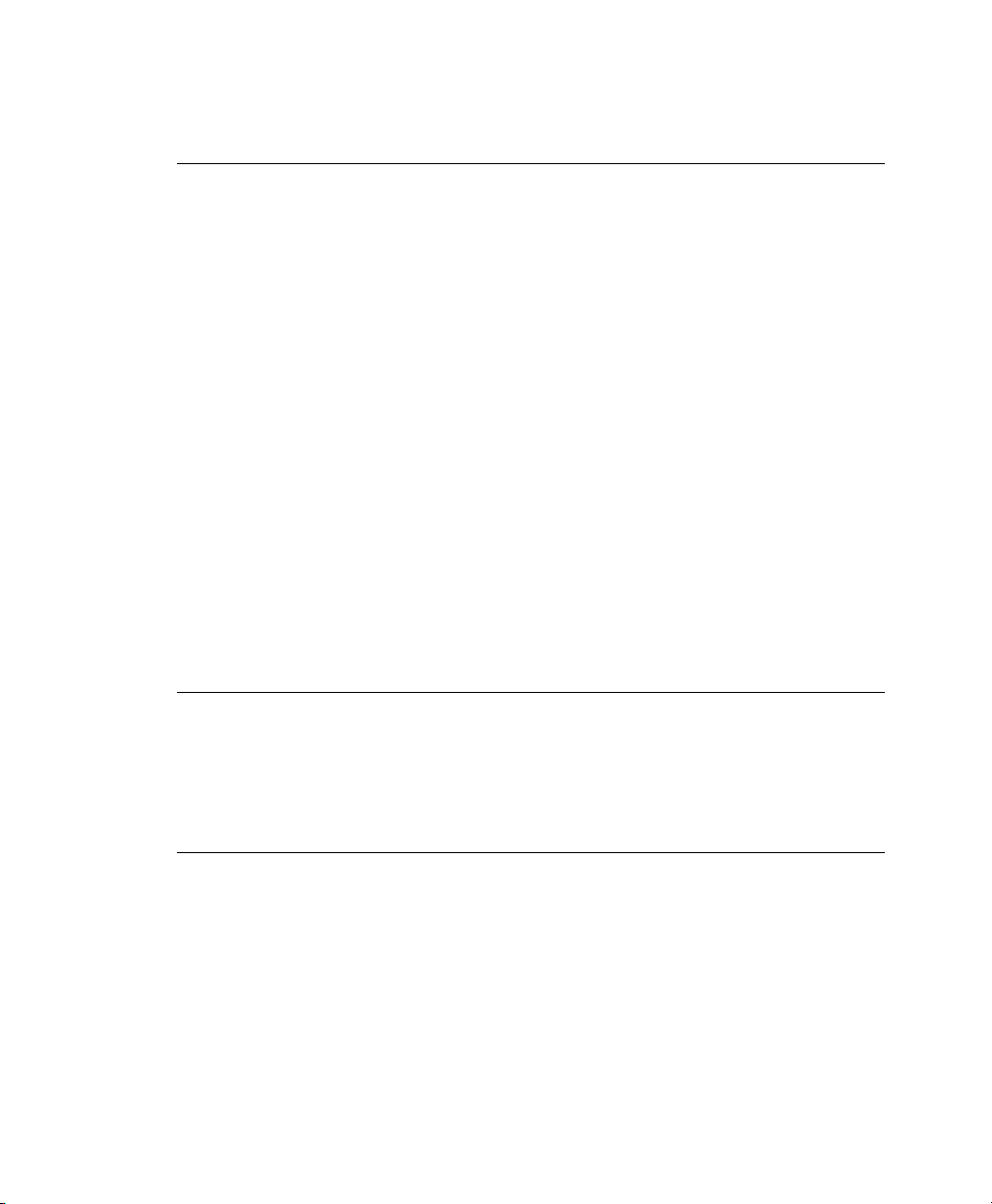

The following gure illustrates how the various components of audit interact with each

other:

Figure 1.1

Straight arrows represent the data ow between components while dashed arrows represent lines of control between components.

auditd

The audit daemon is responsible for writing the audit messages to disk that were

generated through the audit kernel interface and triggered by application and system

activity. How the audit daemon is started is controlled by its conguration le,

Introducing the Components of Linux Audit

Understanding Linux Audit 3

Page 12

/etc/sysconfig/auditd. How the audit system functions once it is started

is controlled by /etc/auditd.conf. For more information about auditd and

its conguration, refer to Section 1.2, “Conguring the Audit Daemon” (page 5).

auditctl

The auditctl utility controls the audit system. It controls the log generation parameters and kernel settings of the audit interface as well as the rule sets that determine

which events are tracked. For more information about auditctl, refer to Section 1.3,

“Controlling the Audit System Using auditctl” (page 10).

audit rules

The le /etc/audit.rules contains a sequence of auditctl commands that

are loaded at system boot time immediately after the audit daemon is started. For

more information about audit rules, refer to Section 1.4, “Passing Parameters to

the Audit System” (page 11).

aureport

The aureport utility allows you to create custom reports from the audit event log.

This report generation can easily be scripted and the output used by various other

applications, for example, to plot these results. For more information about aureport,

refer to Section 1.5, “Understanding the Audit Logs and Generating Reports”

(page 15).

ausearch

The ausearch utility can search the audit log le for certain events using various

keys or other characteristics of the logged format. For more information about

ausearch, refer to Section 1.6, “Querying the Audit Daemon Logs with ausearch”

(page 27).

audispd

The audit dispatcher daemon (audispd) can be used to relay event notications to

other applications instead of or in addition to writing them to disk in the audit log.

autrace

The autrace utility traces individual processes in a fashion similar to strace. The

output of autrace is logged to the audit log. For more information about autrace,

refer to Section 1.7, “Analyzing Processes with autrace” (page 31).

4 The Linux Audit Framework

Page 13

1.2 Conguring the Audit Daemon

Before you can actually start generating audit logs and process them, congure the

audit daemon itself. Congure how it is started in the /etc/sysconfig/auditd

conguration le and congure how the audit system functions once the daemon has

been started in /etc/auditd.conf.

The most important conguration parameters in /etc/sysconfig/auditd are:

AUDITD_LANG="en_US"

AUDITD_DISABLE_CONTEXTS="no"

AUDITD_LANG

The locale information used by audit. The default setting is en_US. Setting it to

none would remove all locale information from audit's environment.

AUDITD_DISABLE_CONTEXTS

Disable system call auditing by default. Set to no for full audit functionality including le and directory watches and system call auditing.

The /etc/auditd.conf conguration le determines how the audit system functions

once the daemon has been started. For most use cases, the default settings shipped with

SUSE Linux Enterprise should sufce. For CAPP environments, most of these parameters need tweaking. The following list briey introduces the parameters available:

log_file = /var/log/audit/audit.log

log_format = RAW

priority_boost = 3

flush = INCREMENTAL

freq = 20

num_logs = 4

dispatcher = /usr/sbin/audispd

disp_qos = lossy

max_log_file = 5

max_log_file_action = ROTATE

space_left = 75

space_left_action = SYSLOG

action_mail_acct = root

admin_space_left = 50

admin_space_left_action = SUSPEND

disk_full_action = SUSPEND

disk_error_action = SUSPEND

Understanding Linux Audit 5

Page 14

Depending on whether you want your environment to satisfy the requirements of CAPP,

you need to be extra restrictive when conguring the audit daemon. Where you need

to use particular settings to meet the CAPP requirements, a “CAPP Environment” note

tells you how to adjust the conguration.

log_file and log_format

log_file species the location where the audit logs should be stored.

log_format determines how the audit information is written to disk. Possible

values for log_format are raw (messages are stored just as the kernel sends

them) or nolog (messages are discarded and not written to disk). The data sent

to the audit dispatcher is not affected if you use the nolog mode. The default setting

is raw and you should keep it if you want to be able to create reports and queries

against the audit logs using the aureport and ausearch tools.

NOTE: CAPP Environment

In a CAPP environment, have the audit log reside on its own partition. By

doing so, you can be sure that the space detection of the audit daemon is

accurate and that you do not have other processes consuming this space.

priority_boost

Determine how much of a priority boost the audit daemon should get. Possible

values are 0 to 3, with 3 assigning the highest priority. The values given here

translate to negative nice values, as in 3 to -3 to increase the priority.

flush and freq

Species whether, how, and how often the audit logs should be written to disk.

Valid values for flush are none, incremental, data, and sync. none tells

the audit daemon not to make any special effort to write the audit data to disk.

incremental tells the audit daemon to explicitly ush the data to disk. A frequency must be specied if incremental is used. A freq value of 20 tells the

audit daemon to request the kernel to ush the data to disk after every 20 records.

The data option keeps the data portion of the disk le in sync at all times while

the sync option takes care of both metadata and data.

6 The Linux Audit Framework

Page 15

NOTE: CAPP Environment

In a CAPP environment, make sure that the audit trail is always fully up to

date and complete. Therefore, use sync or data with the flush parameter.

num_logs

Specify the number of log les to keep if you have given rotate as the

max_log_file_action. Possible values range from 0 to 99. A value less than

2 means that the log les are not rotated at all. As you increase the number of les

to rotate, you increase the amount of work required of the audit daemon. While

doing this rotation, auditd cannot always service new data that is arriving from the

kernel as quickly, which can result in a backlog condition (triggering auditd to react

according to the failure ag, described in Section 1.3, “Controlling the Audit System

Using auditctl” (page 10)). In this situation, increasing the backlog limit is recom-

mended. Do so by changing the value of the -b parameter in the /etc/audit

.rules le.

dispatcher and disp_qos

The dispatcher is started by the audit daemon during its start. The audit daemon

relays the audit messages to the application specied in dispatcher. This application must be a highly trusted one, because it needs to run as root. disp_qos

determines whether you allow for lossy or lossless communication between

the audit daemon and the dispatcher. If you choose lossy, the audit daemon might

discard some audit messages when the message queue is full. These events still get

written to disk if log_format is set to raw, but they might not get through to

the dispatcher. If you choose lossless the audit logging to disk is blocked until

there is an empty spot in the message queue. The default value is lossy.

max_log_file and max_log_file_action

max_log_file takes a numerical value that species the maximum le size in

megabytes the log le can reach before a congurable action is triggered. The action

to be taken is specied in max_log_file_action. Possible values for

max_log_file_action are ignore, syslog, suspend, rotate, and

keep_logs. ignore tells the audit daemon to do nothing once the size limit is

reached, syslog tells it to issue a warning and send it to syslog, and suspend

causes the audit daemon to stop writing logs to disk leaving the daemon itself still

alive. rotate triggers log rotation using the num_logs setting. keep_logs

Understanding Linux Audit 7

Page 16

also triggers log rotation, but does not use the num_log setting, so always keeps

all logs.

NOTE: CAPP Environment

To keep a complete audit trail in CAPP environments, the keep_logs

option should be used. If using a separate partition to hold your audit logs,

adjust max_log_file and max_log_file_action to use the entire

space available on that partition.

action_mail_acct

Specify an e-mail address or alias to which any alert messages should be sent. The

default setting is root, but you can enter any local or remote account as long as

e-mail and the network are properly congured on your system and /usr/lib/

sendmail exists.

space_left and space_left_action

space_left takes a numerical value in megabytes of remaining disk space that

triggers a congurable action by the audit daemon. The action is specied in

space_left_action. Possible values for this parameter are ignore, syslog,

email, suspend, single, and halt. ignore tells the audit daemon to ignore

the warning and do nothing, syslog has it issue a warning to syslog, and email

sends an e-mail to the account specied under action_mail_acct. suspend

tells the audit daemon to stop writing to disk but remain alive while single triggers

the system to be brought down to single user mode. halt triggers a full shutdown

of the system.

NOTE: CAPP Environment

Make sure that space_left is set to a value that gives the administrator

enough time to react to the alert and allows him to free enough disk space

for the audit daemon to continue to work. Freeing disk space would involve

calling aureport -t and archiving the oldest logs on a separate archiving

partition or resource. The actual value for space_left depends on the

size of your deployment. Set space_left_action to email.

admin_space_left and admin_space_left_action

admin_space_left takes a numerical value in megabytes of remaining disk

space. The system is already running low on disk space when this limit is reached

8 The Linux Audit Framework

Page 17

and the administrator has one last chance to react to this alert and free disk space

for the audit logs. The value of admin_space_left should be lower than the

value for space_left. The values for admin_space_left_action are the

same as for space_left_action.

NOTE: CAPP Environment

Set admin_space_left to a value that would just allow the administrator's actions to be recorded. The action should be set to single or halt.

disk_full_action

Specify which action to take when the system runs out of disk space for the audit

logs. The possible values are the same as for space_left_action.

NOTE: CAPP Environment

As the disk_full_action is triggered when there is absolutely no more

room for any audit logs, you should bring the system down to single-user

mode (single) or shut it down completely (halt).

disk_error_action

Specify which action to take when the audit daemon encounters any kind of disk

error while writing the logs to disk or rotating the logs. The possible value are the

same as for space_left_action.

NOTE: CAPP Environment

Use syslog, single, or halt depending on your site's policies regarding

the handling of any kind of hardware failure.

Once the daemon conguration in /etc/sysconfig/auditd and /etc/auditd

.conf is complete, the next step is to focus on controlling the amount of auditing the

daemon does and to assign sufcient resources and limits to the daemon so it can operate

smoothly.

Understanding Linux Audit 9

Page 18

1.3 Controlling the Audit System Using auditctl

auditctl is responsible for controlling the status and some basic system parameters of

the audit daemon. It controls the amount of auditing performed on the system. Using

audit rules, auditctl controls which components of your system are subjected to the

audit and to what extent they are audited. Audit rules can be passed to the audit daemon

on the auditctl command line as well as by composing a rule set and instructing

the audit daemon to process this le. By default, the rcaudit script is congured to

check for audit rules under /etc/audit.rules. For more details on audit rules,

refer to Section 1.4, “Passing Parameters to the Audit System” (page 11).

The main auditctl commands to control basic audit system parameters are:

• auditctl -e to enable or disable audit

• auditctl -f to control the failure ag

• auditctl -r to control the rate limit for audit messages

• auditctl -b to control the backlog limit

• auditctl -s to query the current status of the audit daemon

The -e, -f, -r, and -b options can also be specied in the audit.rules le to

avoid having to enter them each time the audit daemon is started.

Audit status messages include information on each of the above-mentioned parameters.

The following example highlights the typical audit status message. This message is

output to the terminal any time you query the status of the audit daemon with auditctl

-s or change the status ag with auditctl -e flag.

Example 1.1

AUDIT_STATUS: enabled=1 flag=2 pid=3105 rate_limit=0 backlog_limit=8192 lost=0

backlog=0

10 The Linux Audit Framework

Querying the audit Status

Page 19

Table 1.1

Audit Status Flags

CommandMeaning [Possible Values]Flag

flag

rate_limit

backlog_limit

lost

backlog

Set the enable ag. [0|1]enabled

Set the failure ag. [0..2] 0=silent,

1=printk, 2=panic (immediate halt without

syncing pending data to disk)

Set a limit in messages per second. If the

rate is not zero and it is exceeded, the action specied in the failure ag is triggered.

Specify the maximum number of outstanding audit buffers allowed. If all buffers are

full, the action specied in the failure ag

is triggered.

messages.

audit buffers.

auditctl -e

[0|1]

auditctl -f

[0|1|2]

—Process ID under which auditd is running.pid

auditctl -r

rate

auditctl -b

backlog

—Count the current number of lost audit

—Count the current number of outstanding

1.4 Passing Parameters to the Audit System

Commands to control the audit system can be invoked individually from the shell using

auditctl or batch read from a le using auditctl -R. This second method is used

by the init scripts to load rules from the le /etc/audit.rules after the audit

daemon has been started. The rules are executed in order from top to bottom. Each of

Understanding Linux Audit 11

Page 20

these rules would expand to a separate auditctl command. The syntax used in the rules

le is the same as that used for the auditctl command.

Changes made to the running audit system by executing auditctl on the command line

are not persistent across system restarts. For changes to persist, add them to the /etc/

audit.rules le and, if they are not currently loaded into audit, restart the audit

system to load the modied rule set by using the rcauditd restart command.

Example 1.2

-b 1000❶

-f 1❷

-r 10❸

-e 1❹

Specify the maximum number of outstanding audit buffers. Depending on the

❶

Example Audit Rules—Audit System Parameters

level of logging activity, you might need to adjust the number of buffers to avoid

causing too heavy an audit load on your system.

Specify the failure ag to use. See Table 1.1, “Audit Status Flags” (page 11) for

❷

possible values.

Specify the maximum number of messages per second that may be issued by the

❸

kernel. See Table 1.1, “Audit Status Flags” (page 11) for details.

Enable or disable the audit subsystem.

❹

Using audit, you can track any kind of le system access to important les, congurations or resources. You can add watches on these and assign keys to each kind of watch

for better identication in the logs.

12 The Linux Audit Framework

Page 21

Example 1.3

-w /etc/shadow❶

-w /etc -p rx❷

-w /etc/passwd -k fk_passwd -p rwxa❸

The -w option tells audit to add a watch to the le specied, in this case /etc/

❶

Example Audit Rules—File System Auditing

shadow. All system calls requesting access permissions to this le are analyzed.

This rule adds a watch to the /etc directory and applies permission ltering for

❷

read and execute access to this directory (-p wx). Any system call requesting

any of these two permissions is analyzed. Only the creation of new les and the

deletion of existing ones are logged as directory-related events. To get more specic events for les located under this particular directory, you should add a

separate rule for each le. A le must exist before you add a rule containing a

watch on it. Auditing les as they are created is not supported.

This rule adds a le watch to /etc/passwd. Permission ltering is applied for

❸

read, write, execute, and attribute change permissions. The -k option allows you

to specify a key to use to lter the audit logs for this particular event later.

System call auditing lets you track your system's behavior on a level even below the

application level. When designing these rules, consider that auditing a great many system

calls may increase your system load and cause you to run out of disk space due. Consider carefully which events need tracking and how they can be ltered to be even more

specic.

Example 1.4

-a entry,always -S mkdir❶

-a entry,always -S access -F a1=4❷

-a exit,always -S ipc -F a0=2❸

-a exit,always -S open -F success!=0❹

-a task,always -F auid=0❺

-a task,always -F uid=0 -F auid=501 -F gid=wheel❻

This rule activates auditing for the mkdir system call. The -a option adds system

❶

Example Audit Rules—System Call Auditing

call rules. This rule triggers an event whenever the mkdir system call is entered

(entry, always). The -S option adds the system call to which this rule should

be applied.

This rule adds auditing to the access system call, but only but only if the second

❷

argument of the system call (mode) is 4 (R_OK). entry,always tells audit to

Understanding Linux Audit 13

Page 22

add an audit context to this system call when entering it and write out a report as

soon as the call exits.

This rule adds an audit context to the IPC multiplexed system call. The specic

❸

ipc system call is passed as the rst syscall argument and can be selected using

-F a0=ipc_call_number.

This rule audits failed attempts to call open.

❹

This rule is an example of a task rule (keyword: task). It is different from the

❺

other rules above in that it applies to processes that are forked or cloned. To lter

these kind of events, you can only use elds that are known at fork time, such as

UID, GID, and AUID. This example rule lters for all tasks carrying an audit ID

of 0.

This last rule makes heavy use of lters. All lter options are combined with a

❻

logical AND operator, meaning that this rule applies to all tasks that carry the

audit ID of 501, have changed to run as root, and have wheel as the group. A

process is given an audit ID on user login. This ID is then handed down to any

child process started by the initial process of the user. Even if the user changes

his identity, the audit ID stays the same and allows tracing actions to the original

user.

TIP: Filtering System Call Arguments

For more details on ltering system call arguments, refer to Section 3.6, “Filter-

ing System Call Arguments” (page 54).

You can not only add rules to the audit system, but also remove them. Delete rules are

used to purge the rule queue of rules that might potentially clash with those you want

to add. There are different methods for deleting the entire rule set at once or for deleting

system call rules or le and directory watches:

Example 1.5

-D❶

-d entry,always -S mkdir❷

-W /etc❸

Clear the queue of audit rules and delete any preexisting rules. This rule is used

❶

Deleting Audit Rules and Events

as the rst rule in /etc/audit.rules les to make sure that the rules that

are about to be added do not clash with any preexisting ones. The auditctl

14 The Linux Audit Framework

Page 23

-D command is also used before doing an autrace to avoid having the trace rules

clash with any rules present in the audit.rules le.

This rule deletes a system call rule. The -d option must precede any system call

❷

rule that should be deleted from the rule queue and must match exactly.

This rule tells audit to discard the rule with the directory watch on /etc from

❸

the rules queue. This rule deletes any rule containing a directory watch on /etc

regardless of any permission ltering or key options.

To get an overview of which rules are currently in use in your audit setup, run

auditctl -l. This command displays all rules with one rule per line.

Example 1.6

LIST_RULES: exit,always watch=/etc perm=rx

LIST_RULES: exit,always watch=/etc/passwd perm=rwxa key=fk_passwd

LIST_RULES: exit,always watch=/etc/shadow perm=rwxa

LIST_RULES: entry,always syscall=mkdir

LIST_RULES: entry,always a1=4 (0x4) syscall=access

LIST_RULES: exit,always a0=2 (0x2) syscall=ipc

LIST_RULES: exit,always success!=0 syscall=open

NOTE: Creating Filter Rules

You can build very sophisticated audit rules by using the various lter options.

Refer to the auditctl(8) man page for more information about options

available for building audit lter rules and audit rules in general.

Listing Rules with auditctl -l

1.5 Understanding the Audit Logs and Generating Reports

To understand what the aureport utility does, it is vital to know how the logs generated

by the audit daemon are structured and what exactly is recorded for an event. Only then

can you decide which report types are most appropriate for your needs.

Understanding Linux Audit 15

Page 24

1.5.1 Understanding the Audit Logs

The following examples highlight two typical events that are logged by audit and how

their trails in the audit log are read. The audit log or logs (if log rotation is enabled) are

stored in the /var/log/audit directory. The rst example is a simple less command. The second example covers a great deal of PAM activity in the logs when a user

tries to remotely log in to a machine running audit.

Example 1.7

type=SYSCALL msg=audit(1175176190.105:157): arch=40000003 syscall=5 success=yes

exit=4 a0=bfba161c a1=8000 a2=0 a3=8000 items=1 ppid=4457 pid=4462 auid=0

uid=0 gid=0 euid=0 suid=0 fsuid=0 egid=0 sgid=0 fsgid=0 tty=pts0 comm="less"

exe="/usr/bin/less" subj=unconstrained key="LOG_audit_log"

type=CWD msg=audit(1175176190.105:157): cwd="/tmp"

type=PATH msg=audit(1175176190.105:157): item=0

name="../var/log/audit/audit.log" inode=458325 dev=03:01 mode=0100640 ouid=0

ogid=0 rdev=00:00

A Simple Audit Event—Viewing the Audit Log

The above event, a simple less /var/log/audit/audit.log, wrote three

messages to the log. All of them are closely linked together and you would not be able

to make sense of one of them without the others. The rst message reveals the following

information:

type

The type of event recorded. In this case, it assigns the SYSCALL type to an event

triggered by a system call (less or rather the underlying open). The CWD event was

recorded to record the current working directory at the time of the syscall. A PATH

event is generated for each path passed to the system call. The open system call

takes only one path argument, so only generates one PATH event. It is important

to understand that the PATH event reports the pathname string argument without

any further interpretation, so a relative path requires manual combination with the

path reported by the CWD event to determine the object accessed.

msg

A message ID enclosed in brackets. The ID splits into two parts. All characters

before the : represent a UNIX epoch time stamp. The number after the colon represents the actual event ID. All events that are logged from one application's system

call have the same event ID. If the application makes a second system call, it gets

another event ID.

16 The Linux Audit Framework

Page 25

arch

References the CPU architecture of the system call. Decode this information using

the -i option on any of your ausearch commands when searching the logs.

syscall

The type of system call as it would have been printed by an strace on this particular

system call. This data is taken from the list of system calls under /usr/include/

asm/unistd.h and may vary depending on the architecture. In this case,

syscall=5 refers to the open system call (see man open(2)) invoked by the

less application.

success

Whether the system call succeeded or failed.

exit

The exit value returned by the system call. For the open system call used in this

example, this is the le descriptor number. This varies by system call.

a0 to a3

The rst four arguments to the system call in numeric form. The values of these

are totally system call dependent. In this example (an open system call), the following are used:

a0=bfba161c a1=8000 a2=0 a3=8000

a0 is the start address of the passed pathname. a1 is the ags. 8000 in hex notation

translates to 100000 in octal notation, which in turn translates to O_LARGEFILE.

a2 is the mode, which, because O_CREAT was not specied, is unused. a3 is not

passed by the open system call. Check the manual page of the respective system

call to nd out which arguments are used with it.

items

The number of strings passed to the application.

ppid

The process ID of the parent of the process analyzed.

pid

The process ID of the process analyzed.

Understanding Linux Audit 17

Page 26

auid

The audit ID. A process is given an audit ID on user login. This ID is then handed

down to any child process started by the initial process of the user. Even if the user

changes his identity (for example, becomes root), the audit ID stays the same.

Thus you can always trace actions to the original user who logged in.

uid

The user ID of the user who started the process. In this case, 0 for root.

gid

The group ID of the user who started the process. In this case, 0 for root.

euid, suid, fsuid

Effective user ID, set user ID, and le system user ID of the user that started the

process.

egid, sgid, fsgid

Effective group ID, set group ID, and le system group ID of the user that started

the process.

tty

The terminal from which the application is started. In this case, a pseudoterminal

used in an SSH session.

comm

The application name under which it appears in the task list.

exe

The resolved pathname to the binary program.

subj

auditd records whether the process is subject to any security context, such as

AppArmor. unconstrained, as in this case, means that the process is not conned with AppArmor. If the process had been conned with audit, the binary

pathname plus the AppArmor prole mode would have been logged.

key

If you are auditing a large number of directories or les, assign key strings each

of these watches. You can use these keys with ausearch to search the logs for

events of this type only.

18 The Linux Audit Framework

Page 27

The second message triggered by the example less call does not reveal anything apart

from just the current working directory when the less command was executed.

The third message reveals the following (the type and message ags have already

been introduced):

item

In this example, item references the a0 argument—a path—that is associated

with the original SYSCALL message. Had the original call had more than one path

argument (such as a cp or mv command), an additional PATH event would have

been logged for the second path argument.

name

Refers to the pathname passed as an argument to the less (or open) call.

inode

Refers to the inode number corresponding to name.

dev

Species the device on which the le is stored. In this case, 03:01, which stands

for /dev/hda1 or “rst partition on the rst IDE device.”

mode

Numerical representation of the le's access permissions. In this case, root has

read and write permissions and his group (root) has read access while the entire

rest of the world cannot access the le at all.

ouid and ogid

Refer to the UID and GID of the inode itself.

rdev

Not applicable for this example. The rdev entry only applies to block or character

devices, not to les.

Example 1.8, “An Advanced Audit Event—Login via SSH” (page 20) highlights the

audit events triggered by an incoming SSH connection. Most of the messages are related

to the PAM stack and reect the different stages of the SSH PAM process. Several of

the audit messages carry nested PAM messages in them that signify that a particular

stage of the PAM process has been reached. Although the PAM messages are logged

by audit, audit assigns its own message type to each event:

Understanding Linux Audit 19

Page 28

Example 1.8

type=USER_AUTH msg=audit(1175508928.540:4499): user pid=28731 uid=0 ❶

auid=0 msg='PAM: authentication acct=root : exe="/usr/sbin/sshd"

(hostname=earth.example.com, addr=192.168.0.1, terminal=ssh res=success)'

type=USER_ACCT msg=audit(1175508928.540:4500): user pid=28731 uid=0 ❷

auid=0 msg='PAM: accounting acct=root : exe="/usr/sbin/sshd"

(hostname=earth.example.com, addr=192.168.0.1, terminal=ssh res=success)'

type=CRED_ACQ msg=audit(1175508928.544:4501): user pid=28729 uid=0 ❸

auid=0 msg='PAM: setcred acct=root : exe="/usr/sbin/sshd"

(hostname=earth.example.com, addr=192.168.0.1, terminal=/dev/pts/0

res=success)'

type=USER_LOGIN msg=audit(1175508928.544:4502): user pid=28732 uid=0 ❹

auid=0 msg='uid=0: exe="/usr/sbin/sshd" (hostname=earth.example.com,

addr=192.168.0.1, terminal=/dev/pts/0 res=success)'

type=USER_START msg=audit(1175508928.548:4503): user pid=28732 uid=0 ❺

auid=0 msg='PAM: session open acct=root : exe="/usr/sbin/sshd"

(hostname=earth.example.com, addr=192.168.0.1, terminal=/dev/pts/0

res=success)'

type=CRED_REFR msg=audit(1175508928.548:4504): user pid=28732 uid=0 ❻

auid=0 msg='PAM: setcred acct=root : exe="/usr/sbin/sshd"

(hostname=earth.example.com, addr=192.168.0.1, terminal=/dev/pts/0

res=success)'

PAM reports that is has successfully requested user authentication for root from

❶

An Advanced Audit Event—Login via SSH

a remote host (earth.example.com, 192.168.0.1). The terminal where this is happening is ssh.

PAM reports that it has successfully determined whether the user is authorized to

❷

log in at all.

PAM reports that the appropriate credentials to log in have been acquired and that

❸

the terminal changed to a normal terminal (/dev/pts0).

The user has successfully logged in. This event is the one used by aureport

❹

-l to report about user logins.

PAM reports that it has successfully opened a session for root.

❺

PAM reports that the credentials have been successfully reacquired.

❻

1.5.2 Generating Custom Audit Reports

The raw audit reports stored in the /var/log/audit directory tend to become very

bulky and hard to understand. To nd individual events of interest, you might have to

20 The Linux Audit Framework

Page 29

read through thousands of other events before you spot the one that you want. To avoid

this, use the aureport utility and create custom reports.

The following use cases highlight just a few of the possible report types that you can

generate with aureport:

Read Audit Logs from Another File

When the audit logs have moved to another machine or when you want to analyze

the logs of a number of machines on your local machine without wanting to connect

to each of these individually, move the logs to a local le and have aureport analyze

them locally:

aureport -if myfile

Summary Report

======================

Range of time: 04/19/2007 13:42:43.280 - 04/23/2007 21:11:21.533

Number of changes in configuration: 55

Number of changes to accounts, groups, or roles: 0

Number of logins: 20

Number of failed logins: 10

Number of users: 3

Number of terminals: 11

Number of host names: 5

Number of executables: 12

Number of files: 3

Number of AVC denials: 0

Number of MAC events: 0

Number of failed syscalls: 4

Number of anomaly events: 0

Number of responses to anomaly events: 0

Number of crypto events: 0

Number of process IDs: 544

Number of events: 2795

The above command, aureport without any arguments, provides just the standard

general summary report generated from the logs contained in myfile. To create

more detailed reports, combine the -if option with any of the options below. For

example, generate a login report that is limited to a certain time frame:

aureport -l -ts 12:00 -te 13:00 -if myfile

Login Report

============================================

# date time auid host term exe success event

============================================

1. 04/23/2007 12:38:38 PM root earth /dev/pts/0 /usr/sbin/sshd yes 1624

Understanding Linux Audit 21

Page 30

Convert Numeric Entities to Text

Some information, such as user IDs, are printed in numeric form. To convert these

into a human-readable text format, add the -i option to your aureport command.

Create a Rough Summary Report

If you are just interested in the current audit statistics (events, logins, processes,

etc.), run aureport without any other option:

aureport

Summary Report

======================

Range of time: 04/19/2007 13:42:43.280 - 04/23/2007 21:11:21.533

Number of changes in configuration: 55

Number of changes to accounts, groups, or roles: 0

Number of logins: 20

Number of failed logins: 10

Number of users: 3

Number of terminals: 11

Number of host names: 5

Number of executables: 12

Number of files: 3

Number of AVC denials: 0

Number of MAC events: 0

Number of failed syscalls: 4

Number of anomaly events: 0

Number of responses to anomaly events: 0

Number of crypto events: 0

Number of process IDs: 544

Number of events: 2795

Create a Summary Report of Failed Events

If you want to break down the overall statistics of plain aureport to the statistics

of failed events, use aureport --failed:

aureport --failed

Failed Summary Report

======================

Range of time: 04/19/2007 13:42:43.280 - 04/23/2007 21:25:38.406

Number of changes in configuration: 0

Number of changes to accounts, groups, or roles: 0

Number of logins: 0

Number of failed logins: 10

Number of users: 1

Number of terminals: 6

Number of host names: 4

Number of executables: 4

Number of files: 1

Number of AVC denials: 0

22 The Linux Audit Framework

Page 31

Number of MAC events: 0

Number of failed syscalls: 4

Number of anomaly events: 0

Number of responses to anomaly events: 0

Number of crypto events: 0

Number of process IDs: 21

Number of events: 32

Create a Summary Report of Successful Events

If you want to break down the overall statistics of a plain aureport to the

statistics of successful events, use aureport --success:

aureport --success

Success Summary Report

======================

Range of time: 04/19/2007 13:42:43.280 - 04/23/2007 21:31:35.865

Number of changes in configuration: 55

Number of changes to accounts, groups, or roles: 0

Number of logins: 20

Number of failed logins: 0

Number of users: 3

Number of terminals: 10

Number of host names: 5

Number of executables: 12

Number of files: 4

Number of AVC denials: 0

Number of MAC events: 0

Number of failed syscalls: 0

Number of anomaly events: 0

Number of responses to anomaly events: 0

Number of crypto events: 0

Number of process IDs: 535

Number of events: 2787

Create Summary Reports

In addition to the dedicated summary reports (main summary and failed and success

summary), use the --summary option with most of the other options to create

summary reports for a particular area of interest only. Not all reports support this

option, however. This example creates a summary report for user login events:

aureport -u --summary

User Summary Report

===========================

total auid

===========================

5640 root

13 tux

3 geeko

3 news

Understanding Linux Audit 23

Page 32

Create a Report of Events

To get an overview of the events logged by audit, use the aureport -e command.

This command generates a numbered list of all events including date, time, event

number, event type, and audit ID.

aureport -e

Event Report

===========================

# date time event type auid

===========================

1. 04/23/2007 08:00:01 AM 1507 USER_ACCT unset

2. 04/23/2007 08:00:01 AM 1508 CRED_ACQ unset

3. 04/23/2007 08:00:01 AM 1509 LOGIN root

4. 04/23/2007 08:00:01 AM 1510 USER_START root

Create a Report from All Process Events

To analyze the log from a process's point of view, use the aureport -p command. This command generates a numbered list of all process events including

date, time, process ID, name of the executable, system call, audit ID, and event

number.

aureport -p

Process ID Report

======================================

# date time pid exe syscall auid event

======================================

1. 04/23/2007 08:00:01 PM 13097 /usr/sbin/cron 0 unset 1888

2. 04/23/2007 08:00:01 PM 13097 /usr/sbin/cron 0 unset 1889

3. 04/23/2007 08:00:01 PM 13097 ? 0 root 1890

Create a Report from All System Call Events

To analyze the audit log from a system call's point of view, use the aureport

-s command. This command generates a numbered list of all system call events

including date, time, number of the system call, process ID, name of the command

that used this call, audit ID, and event number.

aureport -s

Syscall Report

=======================================

# date time syscall pid comm auid event

=======================================

1. 04/23/2007 08:04:08 PM 5 13374 file root 1900

2. 04/23/2007 08:04:08 PM 5 13376 file root 1901

3. 04/23/2007 08:04:08 PM 5 13368 less root 1902

24 The Linux Audit Framework

Page 33

Create a Report from All Executable Events

To analyze the audit log from an executable's point of view, use the aureport

-x command. This command generates a numbered list of all executable events

including date, time, name of the executable, the terminal it is run in, the host executing it, the audit ID, and event number.

aureport -x

Executable Report

====================================

# date time exe term host auid event

====================================

1. 04/23/2007 08:00:01 PM /usr/sbin/cron cron ? unset 1888

2. 04/23/2007 08:00:01 PM /usr/sbin/cron cron ? unset 1889

3. 04/23/2007 08:00:01 PM /usr/sbin/cron cron ? root 1891

Create a Report about Files

To generate a report from the audit log that focuses on le access, use the

aureport -f command. This command generates a numbered list of all lerelated events including date, time, name of the accessed le, number of the system

call accessing it, success or failure of the command, the executable accessing the

le, audit ID, and event number.

aureport -f

File Report

===============================================

# date time file syscall success exe auid event

===============================================

1. 04/23/2007 06:16:38 PM /var/log/audit/audit.log 5 yes /usr/bin/file

root 1822

2. 04/23/2007 06:16:38 PM /var/log/audit/audit.log 5 yes /usr/bin/file

root 1823

3. 04/23/2007 06:16:38 PM /var/log/audit/audit.log 5 yes /usr/bin/less

root 1824

Create a Report about Users

To generate a report from the audit log that illustrates which users are running what

executables on your system, use the aureport -u command. This command

generates a numbered list of all user-related events including date, time, audit ID,

terminal used, host, name of the executable, and an event ID.

aureport -u

User ID Report

====================================

# date time auid term host exe event

====================================

Understanding Linux Audit 25

Page 34

1. 04/23/2007 08:00:01 PM unset cron ? /usr/sbin/cron 1888

2. 04/23/2007 08:00:01 PM unset cron ? /usr/sbin/cron 1889

3. 04/23/2007 08:00:01 PM root ? ? ? 1890

4. 04/23/2007 08:00:01 PM root cron ? /usr/sbin/cron 1891

5. 04/23/2007 08:00:01 PM root cron ? /usr/sbin/cron 1892

6. 04/23/2007 08:00:01 PM root cron ? /usr/sbin/cron 1893

7. 04/23/2007 08:04:01 PM unset ssh 192.168.0.20 /usr/sbin/sshd 1894

Create a Report about Logins

To create a report that focuses on the login attempts to your machine, run the

aureport -l command. This command generates a numbered list of all loginrelated events including date, time, audit ID, host and terminal used, name of the

executable, success or failure of the attempt, and an event ID.

aureport -l

Login Report

============================================

# date time auid host term exe success event

============================================

1. 04/23/2007 12:38:38 PM root earth.example.com /dev/pts/0 /usr/sbin/sshd

yes 1624

2. 04/23/2007 01:38:12 PM root earth.example.com /dev/pts/1 /usr/sbin/sshd

yes 1655

3. 04/23/2007 03:32:58 PM root 192.168.0.20 /dev/pts/0 /usr/sbin/sshd yes

1712

Limit a Report to a Certain Time Frame

To analyze the logs for a particular time frame, such as only the working hours of

April 23, 2007, rst nd out whether this data is contained in the the current audit

.log or whether the logs have been rotated in by running aureport -t:

aureport -t

Log Time Range Report

=====================

/var/log/audit/audit.log: 04/19/2007 13:42:43.280 - 04/23/2007 22:19:08.087

The current audit.log contains all the desired data. Otherwise, use the -if

option to point the aureport commands to the log le that contains the needed data.

Then, specify the start date and time and the end date and time of the desired time

frame and combine it with the report option needed. This example focuses on login

attempts:

aureport -ts 04/23/2007 8:00 -te 04/23/2007 17:00 -l

Login Report

26 The Linux Audit Framework

Page 35

============================================

# date time auid host term exe success event

============================================

1. 04/23/2007 12:38:38 PM root earth.example.com /dev/pts/0 /usr/sbin/sshd

yes 1624

2. 04/23/2007 01:38:12 PM root earth.example.com /dev/pts/1 /usr/sbin/sshd

yes 1655

3. 04/23/2007 03:32:58 PM root sun.example.com /dev/pts/0 /usr/sbin/sshd

yes 1712

The start date and time are specied with the -ts option. Any event that has a

time stamp equal to or after your given start time appears in the report. If you omit

the date, aureport assumes that you meant today. If you omit the time, it assumes

that the start time should be midnight of the date specied. Use the 24 clock notation

rather than the 12 hour one and adjust the date format to your locale (specied in

/etc/sysconfig/audit under AUDITD_LANG, default is en_US).

Specify the end date and time with the -te option. Any event that has a time stamp

equal to or before your given event time appears in the report. If you omit the date,

aureport assumes that you meant today. If you omit the time, it assumes that

the end time should be now. Use a similar format for the date and time as for -ts.

All reports except the summary ones are printed in column format and sent to stdout,

which means that this data can be piped to other commands very easily. The visualization

scripts introduced in Section 1.8, “Visualizing Audit Data” (page 32) are just one ex-

ample of how to further process the data generated by audit.

1.6 Querying the Audit Daemon Logs with ausearch

The aureport tool helps you to create overall summaries of what is happening on the

system, but if you are interested in the details of a particular event, ausearch is the tool

to use. ausearch allows you to search the audit logs using special keys and search

phrases that relate to most of the ags that appear in event messages in /var/log/

audit/audit.log. Not all record types contain the same search phrases. There are

no hostname or uid entries in a PATH record, for example. When searching, make

sure that you choose appropriate search criteria to catch all records you need. On the

other hand, you could be searching for a specic type of record and still get various

other related records along with it. This is caused by different parts of the kernel contributing additional records for events that are related to the one to nd. For example,

Understanding Linux Audit 27

Page 36

you would always get a PATH record along with the SYSCALL record for an open

system call.

TIP: Using Multiple Search Options

Any of the command line options can be combined with logical AND operators

to narrow down your search.

Read Audit Logs from Another File

When the audit logs have moved to another machine or when you want to analyze

the logs of a number of machines on your local machine without wanting to connect

to each of these individually, move the logs to a local le and have ausearch search

them locally:

ausearch -option -if myfile

Convert Numeric Results into Text

Some information, such as user IDs are printed in numeric form. To convert these

into human readable text format, add the -i option to your ausearch command.

Search by Audit Event ID

If you have previously run an audit report or done an autrace, you might want to

analyze the trail of a particular event in the log. Most of the report types described

in Section 1.5, “Understanding the Audit Logs and Generating Reports” (page 15)

include audit event IDs in their output. An audit event ID is the second part of an

audit message ID, which consists of a UNIX epoch time stamp and the audit event

ID separated by a colon. All events that are logged from one application's system

call have the same event ID. Use this event ID with ausearch to retrieve this event's

trail from the log.

The autrace tool asks you to review the complete trail of the command traced in

the logs using ausearch. autrace provides you with the complete ausearch command

including the audit event ID.

In both cases, use a command similar to the following:

ausearch -a 5451

time->Wed Apr 25 21:59:44 2007

type=PATH msg=audit(1177531184.201:5451): item=0 name="/var/log/audit"

inode=651613 dev=03:01 mode=040700 ouid=0 ogid=0 rdev=00:00

type=CWD msg=audit(1177531184.201:5451): cwd="/root"

type=SYSCALL msg=audit(1177531184.201:5451): arch=40000003 syscall=5

28 The Linux Audit Framework

Page 37

success=yes exit=4 a0=80624a0 a1=18800 a2=0 a3=80624a0 items=1 ppid=29163

pid=29433 auid=0 uid=0 gid=0 euid=0 suid=0 fsuid=0 egid=0 sgid=0 fsgid=0

tty=pts2 comm="aureport" exe="/sbin/aureport" subj=unconstrained

key="LOG_audit"

The ausearch -a command grabs all records in the logs that are related to the

audit event ID provided and displays them. This option cannot be combined with

any other option.

Search by Message Type

To search for audit records of a particular message type, use the ausearch -m

message_type command. Examples of valid message types include PATH,

SYSCALL, and USER_LOGIN. Running ausearch -m without a message type

displays a list of all message types.

Search by Login ID

To view records associated with a particular login user ID, use the ausearch

-ul command. It displays any records related to the user login ID specied provided that user had been able to log in successfully.

Search by User ID

View records related to any of the user IDs (both user ID and effective user ID)

with ausearch -ua. View reports related to a particular user ID with ausearch

-ui uid. Search for records related to a particular effective user ID, use the

ausearch -ue euid. Searching for a user ID means the user ID of the user

creating a process. Searching for an effective user ID means the user ID and privileges that are required to run this process.

Search by Group ID

View records related to any of the group IDs (both group ID and effective group

ID) with the ausearch -ga command. View reports related to a particular user

ID with ausearch -gi gid. Search for records related to a particular effective

group ID, use ausearch -ge egid.

Search by Command Line Name

Viewrecords related to a certain command, using the ausearch -c comm_name

command, for example, ausearch -c less for all records related to the less

command.

Understanding Linux Audit 29

Page 38

Search by Executable Name

View records related to a certain executable with the ausearch -x exe command, for example ausearch -x /usr/bin/less for all records related to

the /usr/bin/less executable.

Search by System Call Name

Viewrecords related to a certain system call with the ausearch -sc syscall

command, for example, ausearch -sc open for all records related to the

open system call.

Search by Process ID

View records related to a certain process ID with the ausearch -p pid command, for example ausearch -p 13368 for all records related to this process

ID.

Search by Event or System Call Success Value

View records containing a certain system call success value with ausearch -sv

success_value, for example, ausearch -sv yes for all successful system

calls.

Search by Filename

View records containing a certain lename with ausearch -f filename,

for example, ausearch -f /foo/bar for all records related to the /foo/

bar le. Using the lename alone would work as well, but using relative paths

would not.

Search by Terminal

View records of events related to a certain terminal only with ausearch -tm

term, for example, ausearch -tm ssh to view all records related to events

on the SSH terminal and ausearch -tm tty to view all events

related to the console.

Search by Hostname

View records related to a certain remote hostname with ausearch -hn

hostname, for example, ausearch -hn earth.example.com. You can

use a hostname, fully qualied domain name, or numeric network address.

30 The Linux Audit Framework

Page 39

Search by Key Field

View records that contain a certain key assigned in the audit rule set to identify

events of a particular type. Use the ausearch -k key_field, for example,

ausearch -k CFG_etc to display any records containing the CFG_etc key.

Limit a Search to a Certain Time Frame

Use -ts and -te to limit the scope of your searches to a certain time frame. The

-ts option is used to specify the start date and time and the -te option is used to

specify the end date and time. These options can be combined with any of the

above, except the -a option. The use of these options is similar to use with aureport.

1.7 Analyzing Processes with autrace

In addition to monitoring your system using the rules you set up, you can also perform

dedicated audits of individual processes using the autrace command. autrace works

similarly to the strace command, but gathers slightly different information. The

output of autrace is written to /var/log/audit/audit.log and does not look

any different from the standard audit log entries.

When performing an autrace on a process, make sure that any audit rules are purged

from the queue to avoid these rules clashing with the ones autrace adds itself. Delete

the audit rules with the auditctl -D command. This stops all normal auditing.

auditctl -D

No rules

autrace /usr/bin/less /etc/sysconfig/auditd

Waiting to execute: /usr/bin/less

Cleaning up...

No rules

Trace complete. You can locate the records with 'ausearch -i -p 7642'

Always use the full path to the executable to track with autrace. After the trace is

complete, autrace provides the event ID of the trace, so you can analyze the entire data

trail with ausearch. To restore the audit system to use the audit rule set again, just restart

the audit daemon with rcauditd restart.

Understanding Linux Audit 31

Page 40

1.8 Visualizing Audit Data

Neither the data trail in /var/log/audit/audit.log nor the different report

types generated by aureport, described in Section 1.5.2, “Generating Custom Audit

Reports” (page 20), provide an intuitive reading experience to the user. The aureport

output is formatted in columns and thus easily available to any sed, perl, or awk scripts

that users might connect to the audit framework to visualize the audit data.

The visualization scripts (see Appendix A, Creating Flow Graphs from the Audit

Statistics (page 61) and Appendix B, Creating Bar Charts from the Audit Statistics

(page 65)) are one example of how to use standard Linux tools available with SUSE

Linux Enterprise or any other Linux distribution to create easy-to-read audit output.

The following examples help you understand how the plain audit reports can be transformed into human readable graphics.

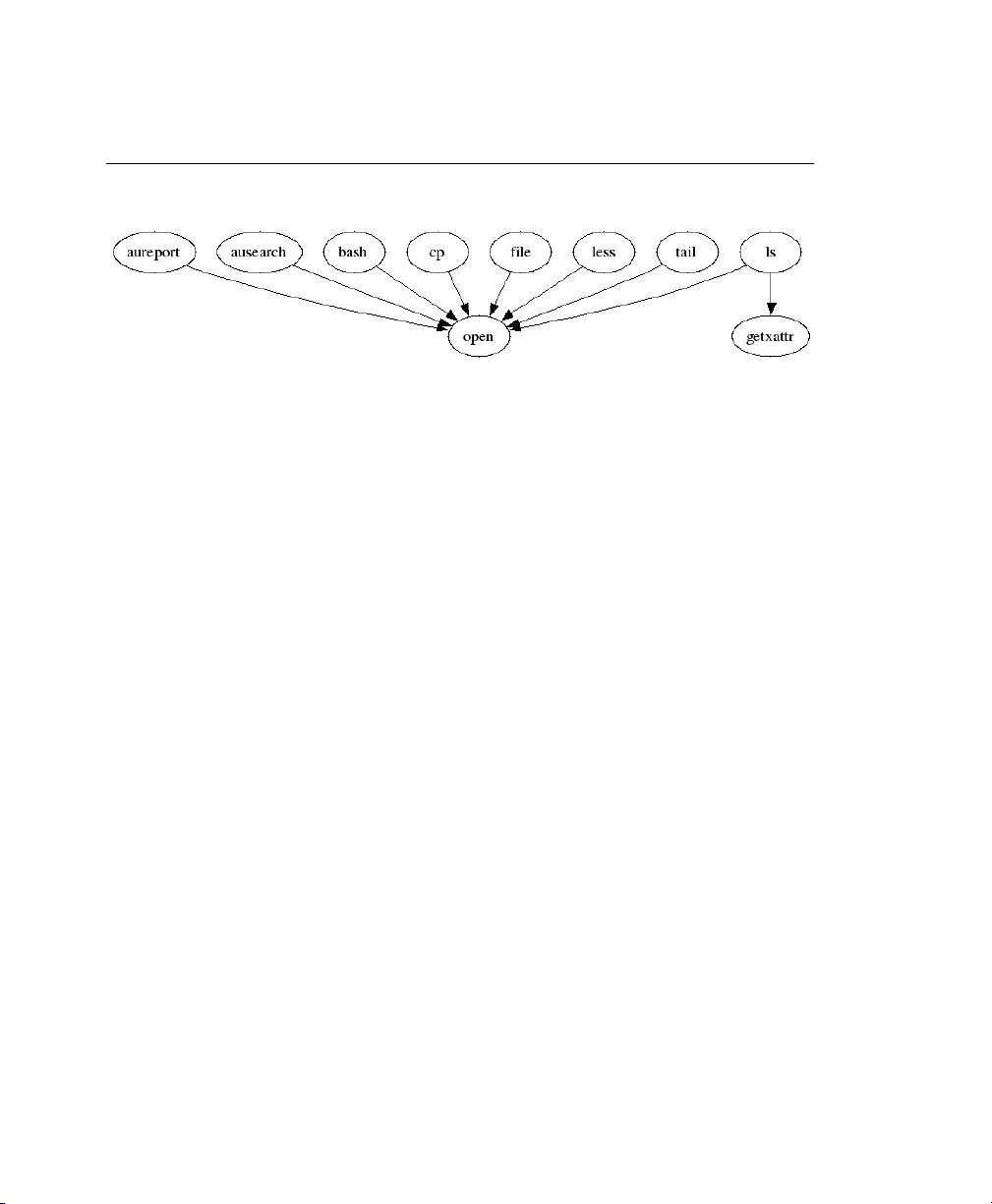

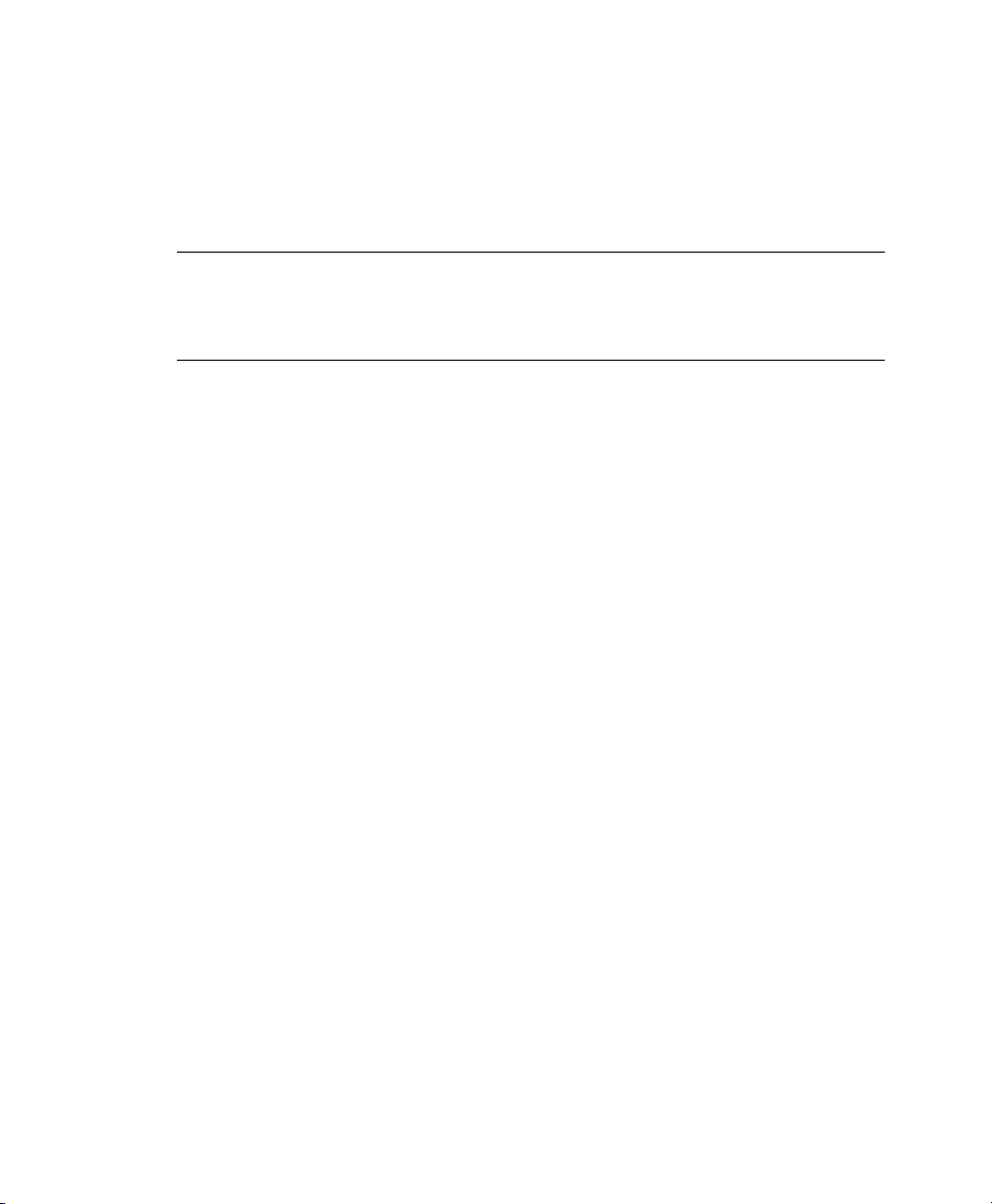

The rst example illustrates the relationship of programs and system calls. To get to

this kind of data, you need to determine the appropriate aureport command that

delivers the source data from which to generate the nal graphic:

aureport -s

Syscall Report

=======================================

# date time syscall pid comm auid event

=======================================

1. 04/23/2007 08:04:08 PM 5 13374 file root 1900

2. 04/23/2007 08:04:08 PM 5 13376 file root 1901

3. 04/23/2007 08:04:08 PM 5 13368 less root 1902

...

The rst thing that the visualization script needs to do on this report is to extract only

those columns that are of interest, in this example, the syscall and the comm columns.

The output is sorted and duplicates removed then the nal output is piped into the visualization program itself:

LC_ALL=C aureport -s -i | awk '/^[0-9]/ { printf "%s %s\n", $6, $4 }' | sort

| uniq| ./mkgraph

NOTE: Adjusting the Locale

Depending on your choice of locale in /etc/sysconfig/auditd, your aureport output might contain an additional data column for AM/PM on time

32 The Linux Audit Framework

Page 41

stamps. To avoid having this confuse your scripts, precede your script calls with

LC_ALL=C to reset the locale and use the 24 hour time format.

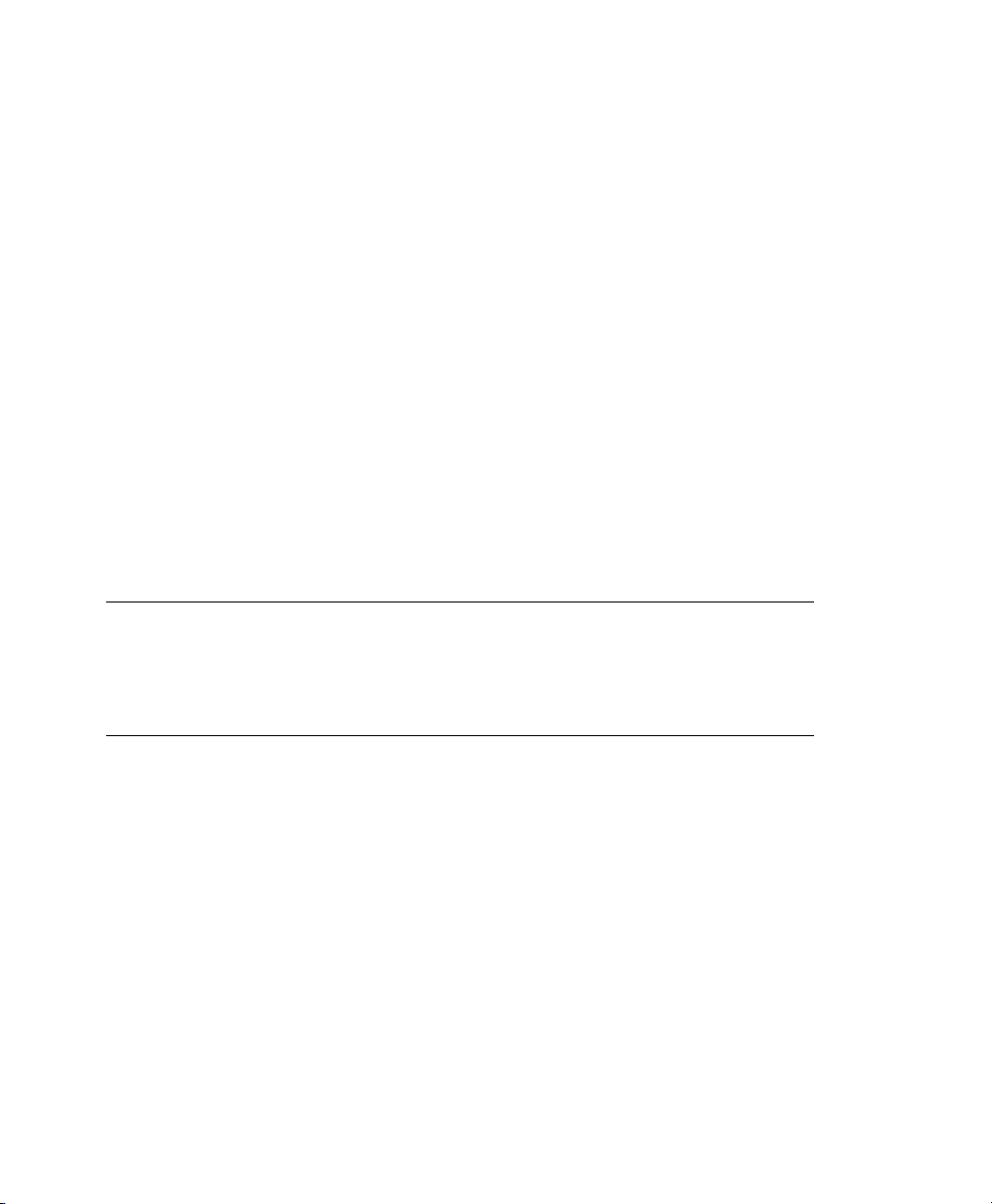

Figure 1.2

Flow Graph—Program versus System Call Relationship

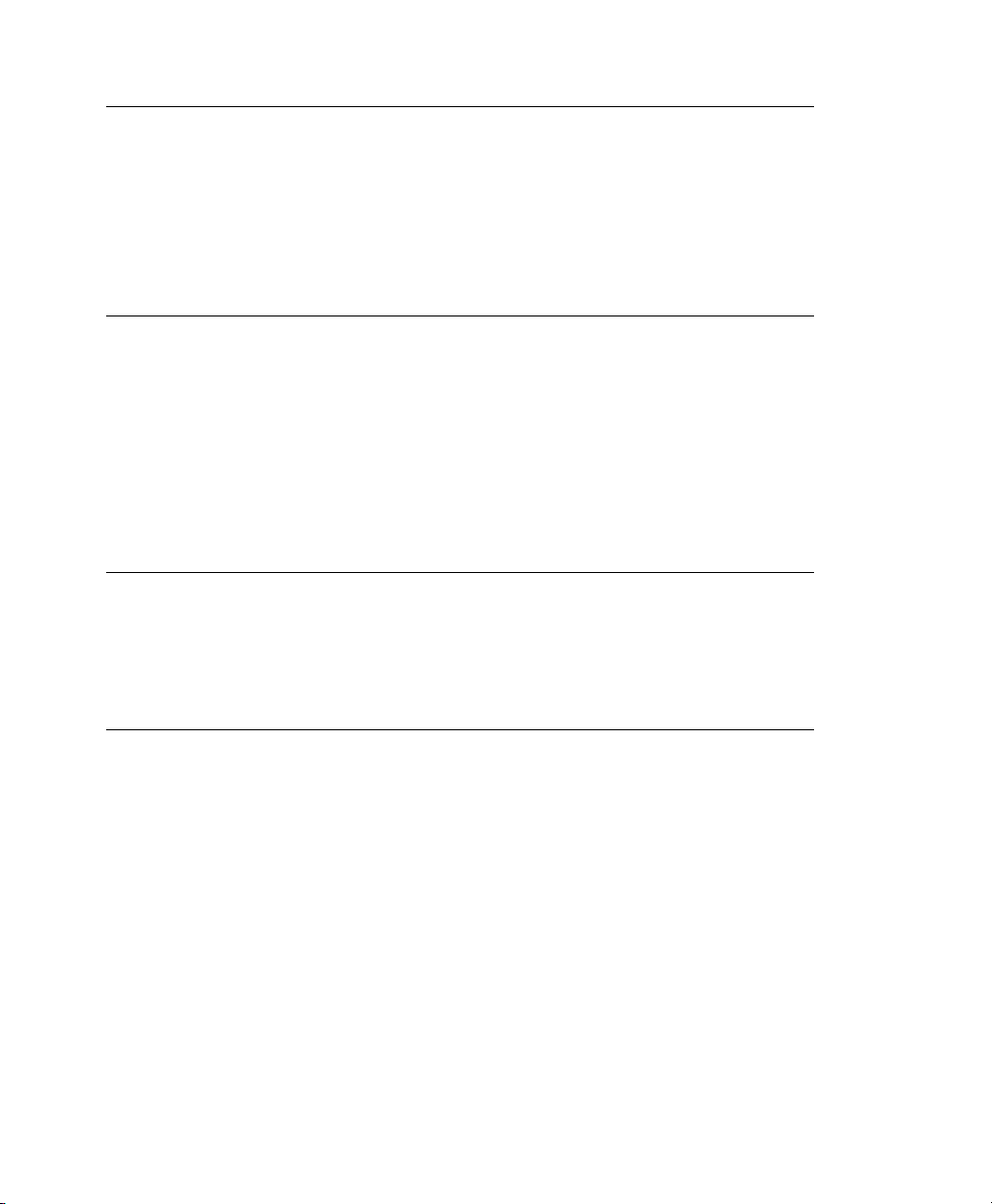

The second example illustrates the different types of events and how many of each type

have been logged. The appropriate aureport command to extract this kind of information is aureport -e:

aureport -e -i --summary

Event Summary Report

======================

total type

======================

2434 SYSCALL

816 USER_START

816 USER_ACCT

814 CRED_ACQ

810 LOGIN

806 CRED_DISP

779 USER_END

99 CONFIG_CHANGE

52 USER_LOGIN

Because this type of report already contains a two column output, it is just piped into

the the visualization script and transformed into a bar chart.

aureport -e -i --summary | ./mkbar events

Understanding Linux Audit 33

Page 42

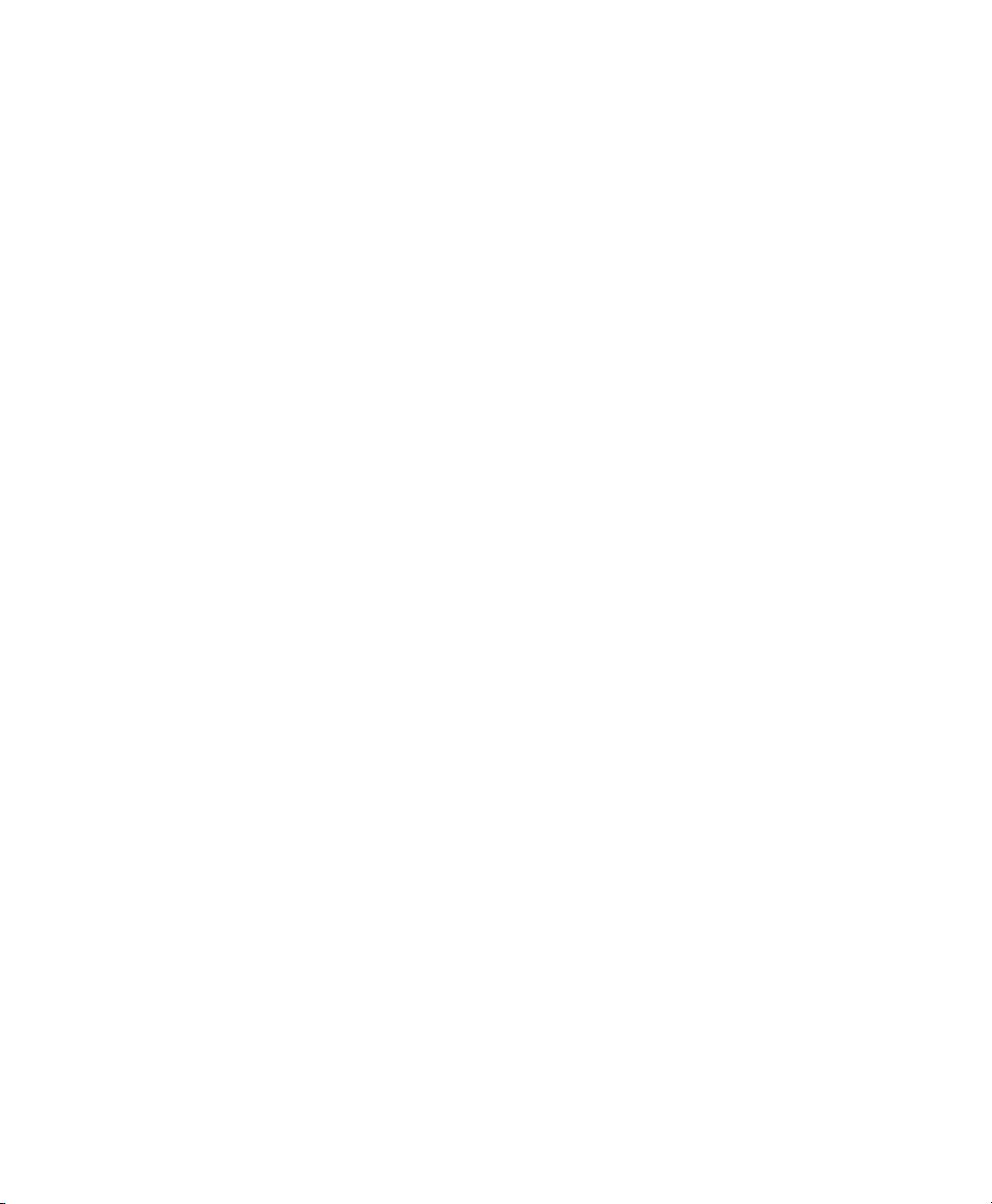

Figure 1.3

Bar Chart—Common Event Types

For background information about the visualization of audit data, refer to the Web site

of the audit project at http://people.redhat.com/sgrubb/audit/

visualize/index.html.

34 The Linux Audit Framework

Page 43

Setting Up the Linux Audit

Framework

This chapter shows how to set up a simple audit scenario. Every step involved in conguring and enabling audit is explained in detail. After you have learned to set up audit,

consider a real-world example scenario in Chapter 3, Introducing an Audit Rule Set

(page 47).

To set up audit on your SUSE Linux Enterprise, you need to complete the following

steps:

Procedure 2.1

Make sure that all required packages are installed: audit, audit-libs, and

1

optionally audit-libs-python. To use the log visualization as described

in Section 2.7, “Conguring Log Visualization” (page 44), install gnuplot

from the SUSE Linux Enterprise media and graphviz from the SUSE Linux

Enterprise SDK.

Determine the components to audit. Refer to Section 2.1, “Determining the

2

Components to Audit ” (page 36) for details.

Check or modify the basic audit daemon conguration. Refer to Section 2.2,

3

“Conguring the Audit Daemon” (page 37) for details.

Setting Up the Linux Audit Framework

2

Enable auditing for system calls. Refer to Section 2.3, “Enabling Audit for System

4

Calls” (page 38) for details.

Compose audit rules to suit your scenario. Refer to Section 2.4, “Setting Up

5

Audit Rules” (page 39) for details.

Setting Up the Linux Audit Framework 35

Page 44

Change your PAM conguration to enable audit IDs. Section 2.5, “Adjusting

6

the PAM Conguration” (page 40).

Generate logs and congure tailor-made reports. Refer to Section 2.6, “Cong-

7

uring Audit Reports” (page 41) for details.

Congure optional log visualization. Refer to Section 2.7, “Conguring Log

8

Visualization” (page 44) for details.

IMPORTANT: Controlling the Audit Daemon

Before conguring any of the components of the audit system, make sure that

the audit daemon is not running by entering rcauditd status as root.

On a default SUSE Linux Enterprise system, audit is started on boot, so you

need to turn it off by entering rcauditd stop. Start the daemon after conguring it with rcauditd start.

2.1 Determining the Components to Audit

Before setting out to create your own audit conguration, determine to which degree

you want to use it. Check the following rules of thumb to determine which use case

best applies to you and your requirements:

• If you require a full security audit for CAPP/EAL certication, enable full audit

for system calls and congure watches on various conguration les and directories,

similar to the rule set featured in Chapter 3, Introducing an Audit Rule Set (page 47).

Proceed to Section 2.3, “Enabling Audit for System Calls” (page 38).

• If you require an occasional audit of a system call instead of a permanent audit for

system calls, use autrace. Proceed to Section 2.3, “Enabling Audit for System

Calls” (page 38).

• If you require le and directory watches to track access to important or securitysensitive data, create a rule set matching these requirements. Enable audit as described in Section 2.3, “Enabling Audit for System Calls” (page 38) and proceed

to Section 2.4, “Setting Up Audit Rules” (page 39).

36 The Linux Audit Framework

Page 45

2.2 Conguring the Audit Daemon

The basic setup of the audit daemon is done in /etc/auditd.conf:

log_file = /var/log/audit/audit.log

log_format = RAW

priority_boost = 3

flush = INCREMENTAL

freq = 20

num_logs = 4

dispatcher = /usr/sbin/audispd

disp_qos = lossy

max_log_file = 5

max_log_file_action = ROTATE

space_left = 75

space_left_action = SYSLOG

action_mail_acct = root

admin_space_left = 50

admin_space_left_action = SUSPEND

disk_full_action = SUSPEND

disk_error_action = SUSPEND

The default settings work reasonably well for many setups. Some values, such as

num_logs, max_log_file, space_left, and admin_space_left depend

on the size of your deployment. If disk space is limited, you might want to reduce the

number of log les to keep if they are rotated and you might want get an earlier warning

if disk space is running out. For a CAPP-compliant setup, adjust the values for

log_file, flush, max_log_file, max_log_file_action, space_left,

space_left_action, admin_space_left, admin_space_left_action,

disk_full_action, and disk_error_action, as described in Section 1.2,

“Conguring the Audit Daemon” (page 5). An example CAPP-compliant conguration

looks like this:

log_file = path_to_separate_partition/audit.log

log_format = RAW

priority_boost = 3

flush = SYNC ### or DATA

freq = 20

num_logs = 4

dispatcher = /usr/sbin/audispd

disp_qos = lossy

max_log_file = 5

max_log_file_action = KEEP_LOGS

space_left = 75

space_left_action = EMAIL

action_mail_acct = root

admin_space_left = 50

admin_space_left_action = SINGLE ### or HALT

Setting Up the Linux Audit Framework 37

Page 46

disk_full_action = SUSPEND ### or HALT

disk_error_action = SUSPEND ### or HALT

The ### precedes comments where you can choose from several options. Do not add

the comments to your actual conguration les.

TIP: For More Information

Refer to Section 1.2, “Conguring the Audit Daemon” (page 5) for detailed

background information about the auditd.conf conguration parameters.

2.3 Enabling Audit for System Calls

A standard SUSE Linux Enterprise system has auditd running by default. There are

different levels of auditing activity available:

Basic Logging

Out of the box without any further conguration, auditd logs only events concerning

its own conguration changes to /var/log/audit/audit.log. No events

(le access, system call, etc.) are generated by the kernel audit component until

requested by auditctl. However, other kernel components and modules may log

audit events outside of the control of auditctl and these appear in the audit log. By

default, the only module that generates audit events is Novell AppArmor.

Advanced Logging with System Call Auditing

To audit system calls and get meaningful le watches, you need to enable audit

contexts for system calls.

As you need system call auditing capabilities even when you are conguring plain le

or directory watches, you need to enable audit contexts for system calls. To enable audit

contexts for the duration of the current session only, execute auditctl -e 1 as

root. To disable this feature, execute auditctl -e 0 as root.

To enable audit contexts for system calls permanently, open the /etc/sysconfig/

auditd conguration le as root and set AUDITD_DISABLE_CONTEXTS to no.

Then restart the audit daemon with the rcauditd restart command. To turn this

feature off temporarily, use auditctl -e 0. To turn it off permanently, set

AUDITD_DISABLE_CONTEXTS to yes.

38 The Linux Audit Framework

Page 47

2.4 Setting Up Audit Rules

Using audit rules, determine which aspects of the system should be analyzed by audit.

Normally this includes important databases and security-relevant conguration les.

You may also analyze various system calls in detail if a broad analysis of your system

is required. A very detailed example conguration that includes most of the rules that

are needed in a CAPP compliant environment is available in Chapter 3, Introducing an

Audit Rule Set (page 47).

A simple rule set for very basic auditing on a few important les and directories could

look like this:

# basic audit system parameters

-D

-b 8192

-f 1

-e 1