Page 1

Bridge Circuits

Marrying Gain and Balance

Jim Williams

Application Note 43

June 1990

Bridge circuits are among the most elemental and powerful

electrical tools. They are found in measurement, switching, oscillator and transducer circuits. Additionally, bridge

techniques are broadband, serving from DC to bandwidths

well into the GHz range. The electrical analog of the mechanical beam balance, they are also the progenitor of all

electrical differential techniques.

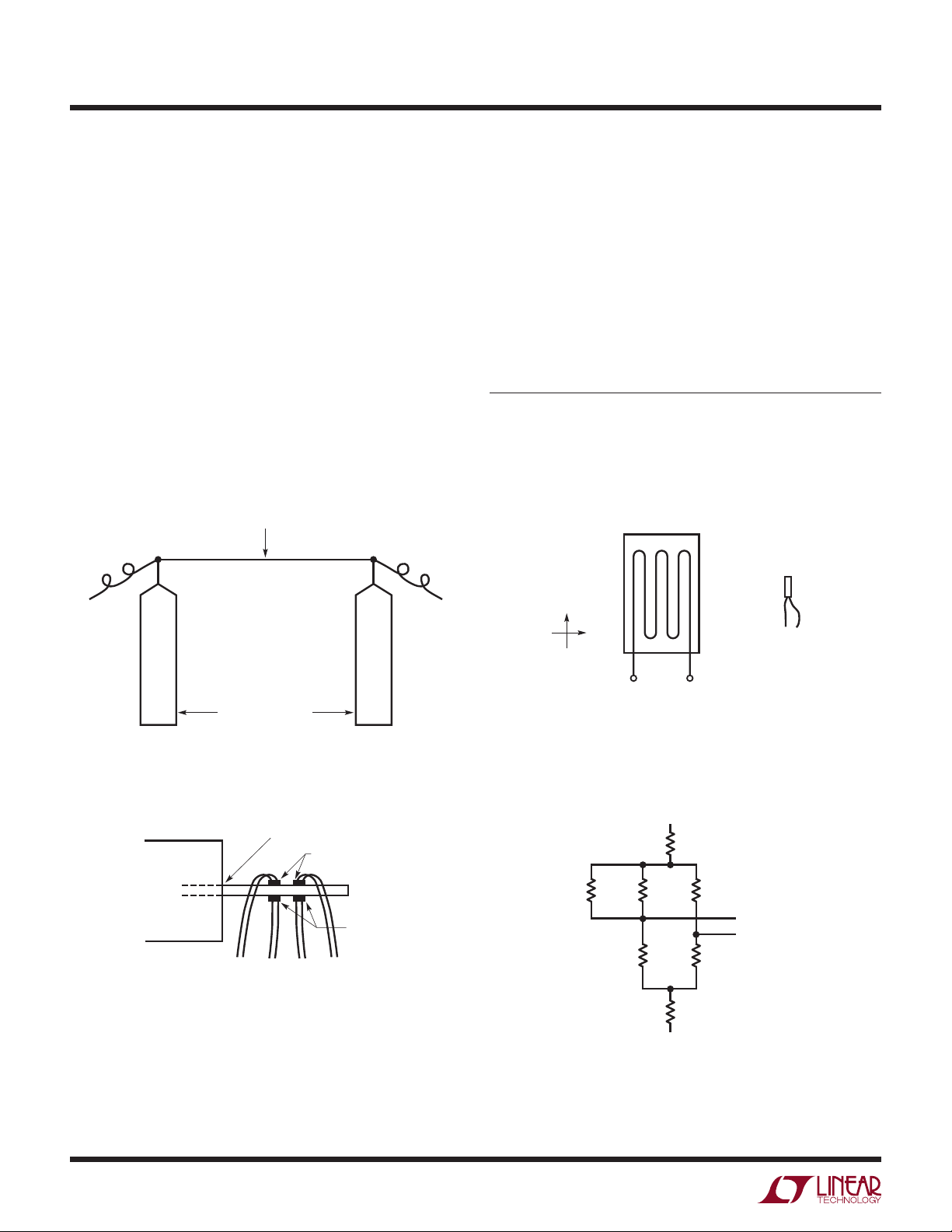

Resistance Bridges

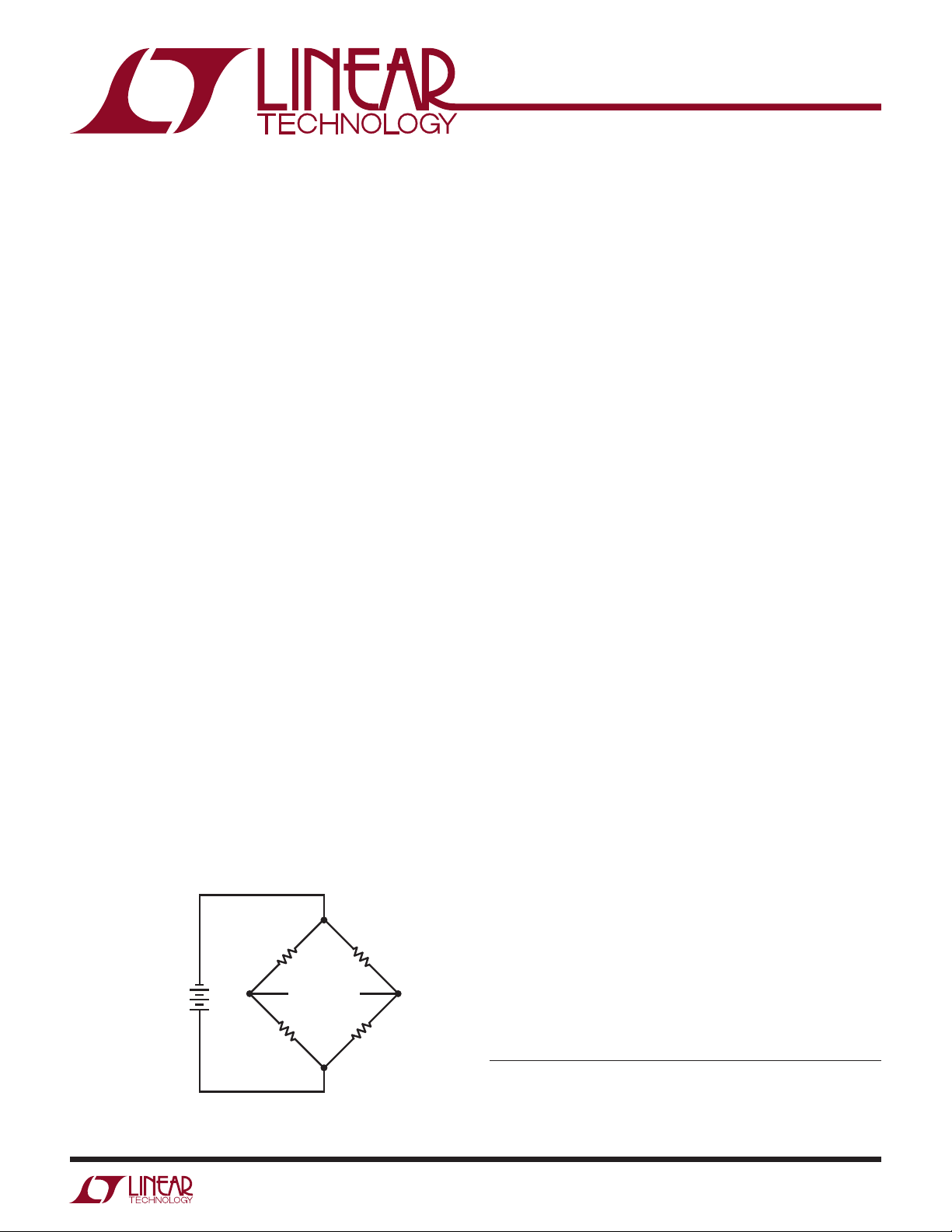

Figure 1 shows a basic resistor bridge. The circuit is

usually credited to Charles Wheatstone, although S. H.

Christie, who demonstrated it in 1833, almost certainly

1

preceded him.

If all resistor values are equal (or the two

sides ratios are equal) the differential voltage is zero. The

excitation voltage does not alter this, as it affects both

sides equally. When the bridge is operating off null, the

excitation’s magnitude sets output sensitivity. The bridge

output is nonlinear for a single variable resistor. Similarly,

two variable arms (e.g., R

and RB both variable) produce

C

nonlinear output, although sensitivity doubles. Linear

outputs are possible by complementary resistance swings

in one or both sides of the bridge.

A great deal of attention has been directed towards this

circuit. An almost uncountable number of tricks and techniques have been applied to enhance linearity, sensitivity

R

EXCITATION

VOLTAGE

A

DIFFERENTIAL

OUTPUT

+

VOLTAGE

R

B

R

C

R

D

and stability of the basic configuration. In particular, transducer manufacturers are quite adept at adapting the bridge

to their needs (see Appendix A, “Strain Gauge Bridges”).

Careful matching of the transducer’s mechanical characteristics to the bridge’s electrical response can provide a

trimmed, calibrated output. Similarly, circuit designers

have altered performance by adding active elements (e.g.,

amplifiers) to the bridge, excitation source or both.

Bridge Output Amplifiers

A primary concern is the accurate determination of the

differential output voltage. In bridges operating at null the

absolute scale factor of the readout device is normally

less important than its sensitivity and zero point stability.

An off-null bridge measurement usually requires a well

calibrated scale factor readout in addition to zero point

stability. Because of their importance, bridge readout

mechanisms have a long and glorious history (see Appendix B, “Bridge Readout—Then and Now”). Today’s

investigator has a variety of powerful electronic techniques

available to obtain highly accurate bridge readouts. Bridge

amplifiers are designed to accurately extract the bridges

differential output from its common mode level. The

ability to reject common mode signal is quite critical. A

typical 10V powered strain gauge transducer produces

only 30mV of signal “riding” on 5V of common mode

level. 12-bit readout resolution calls for an LSB of only

7.3μV…..almost 120dB below the common mode signal!

Other significant error terms include offset voltage, and

its shift with temperature and time, bias current and gain

stability. Figure 2 shows an “Instrumentation Amplifier,”

which makes a very good bridge amplifier. These devices

are usually the first choice for bridge measurement,

and bring adequate performance to most applications.

AN43 F01

Figure 1. The Basic Wheatstone Bridge,

Invented by S. H. Christie

Note 1: Wheatstone had a better public relations agency, namely himself.

For fascinating details, see reference 19.

L, LT, LTC, LTM, Linear Technology and the Linear logo are registered trademarks of Linear

Technology Corporation. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners.

an43f

AN43-1

Page 2

Application Note 43

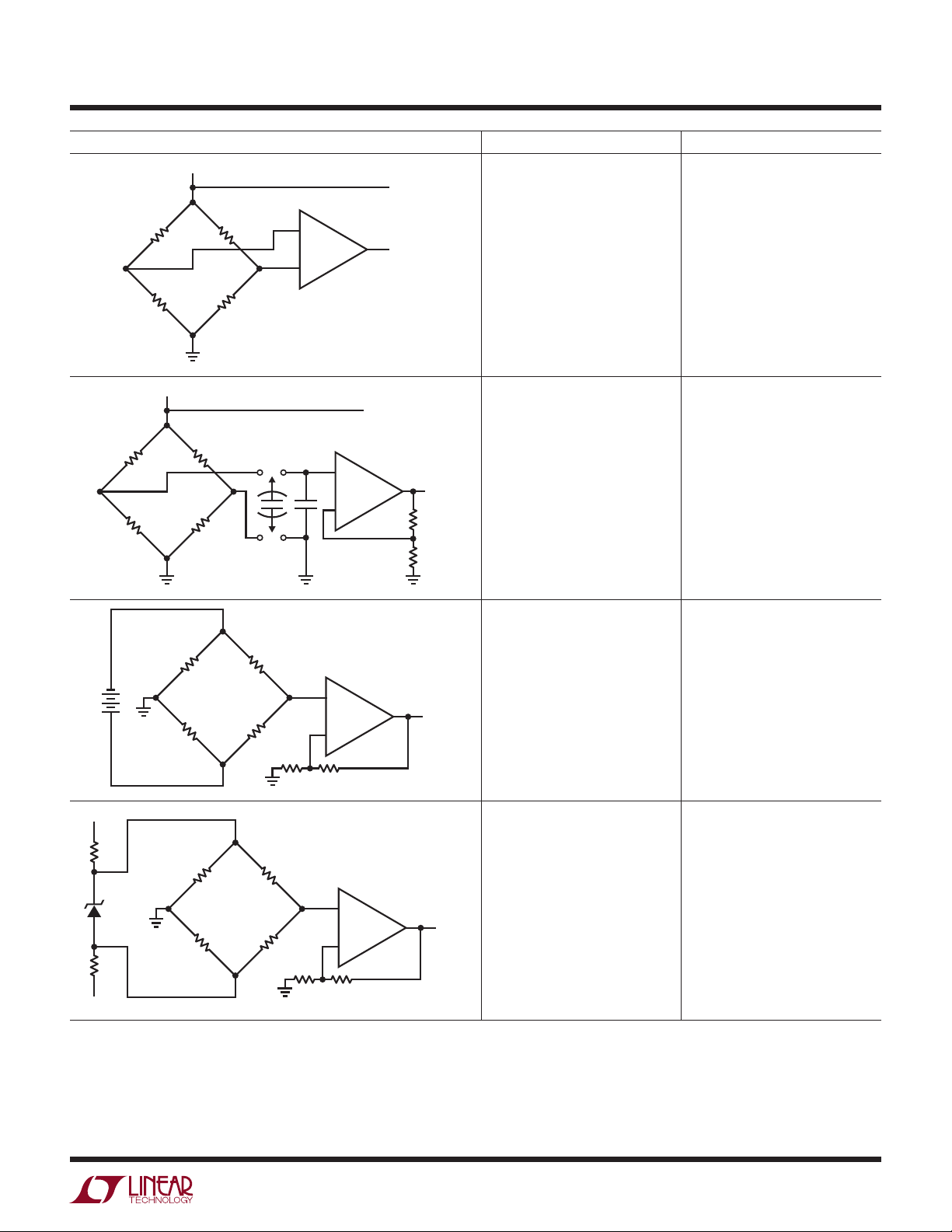

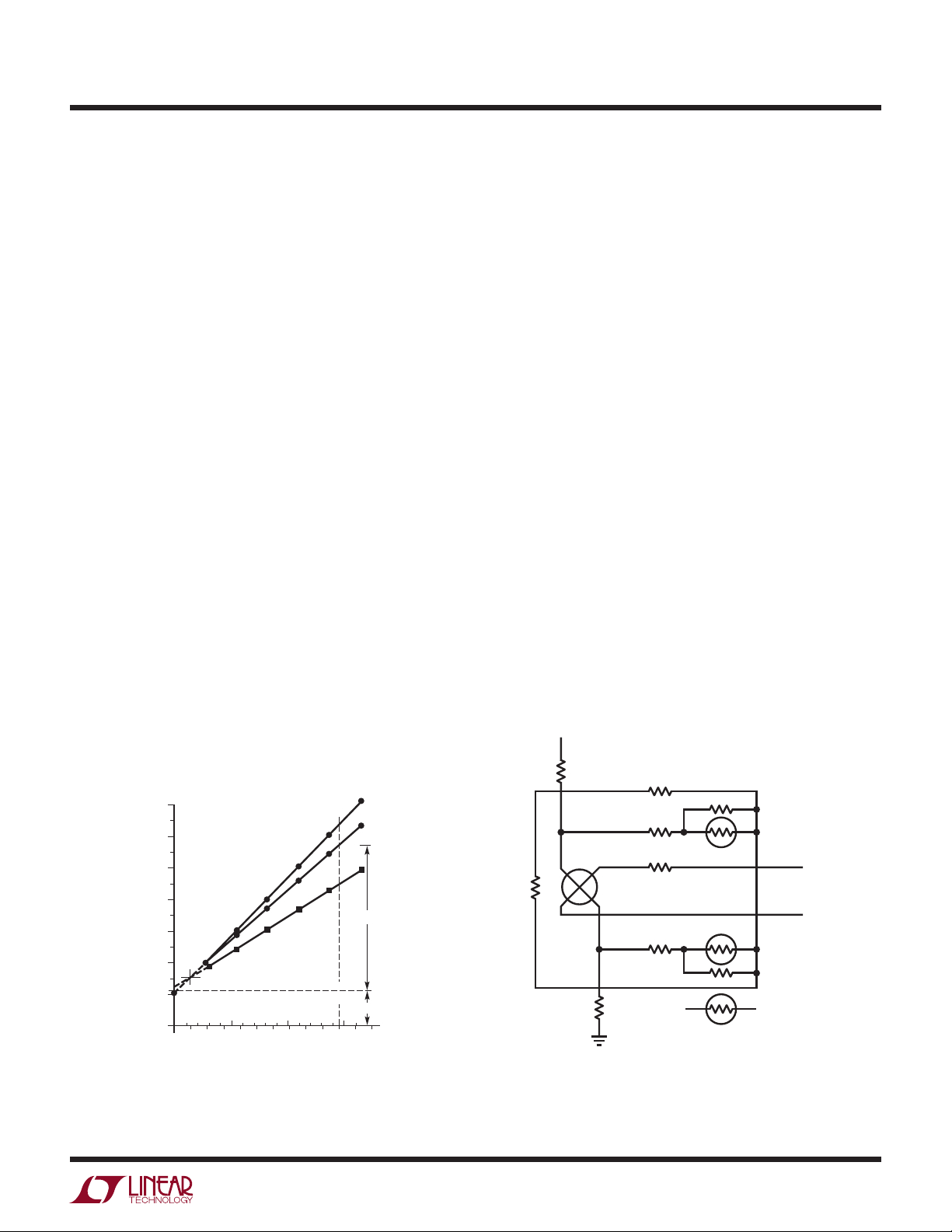

In general, instrumentation amps feature fully differential

inputs and internally determined stable gain. The absence

of a feedback network means the inputs are essentially passive, and no significant bridge loading occurs. Instrumentation amplifiers meet most bridge requirements. Figure 3

lists performance data for some specific instrumentation

amplifiers. Figure 4’s table summarizes some options

for DC bridge signal conditioning. Various approaches

are presented, with pertinent characteristics noted. The

constraints, freedoms and performance requirements of

any particular application define the best approach.

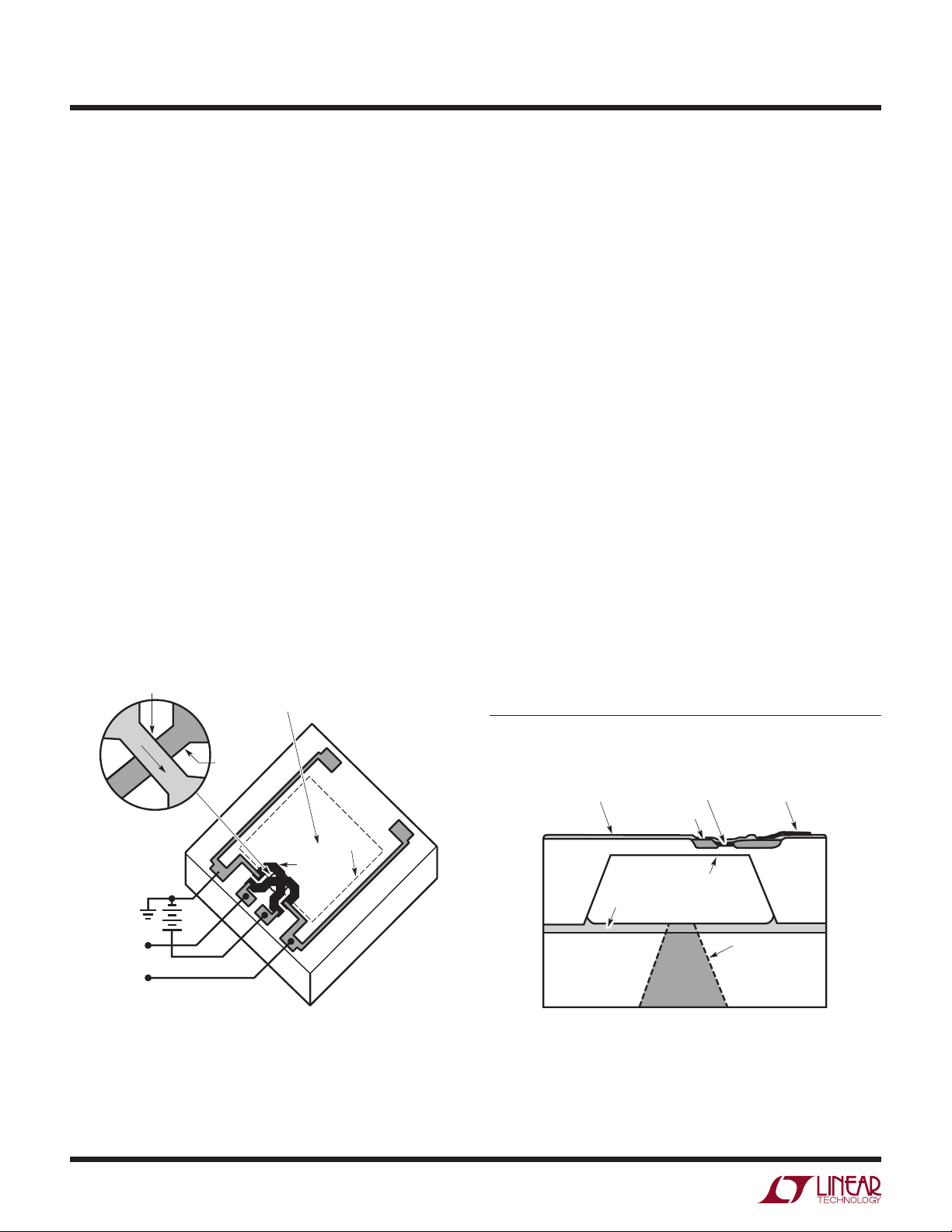

+

–

mNO FEEDBACK RESISTORS USED

mGAIN FIXED INTERNALLY (TYP 10 OR 100)

OR SOMETIMES RESISTOR PROGRAMMABLE

mBALANCED, PASSIVE INPUTS

Figure 2. Conceptual Instrumentation Amplifier

AN43 F02

DC Bridge Circuit Applications

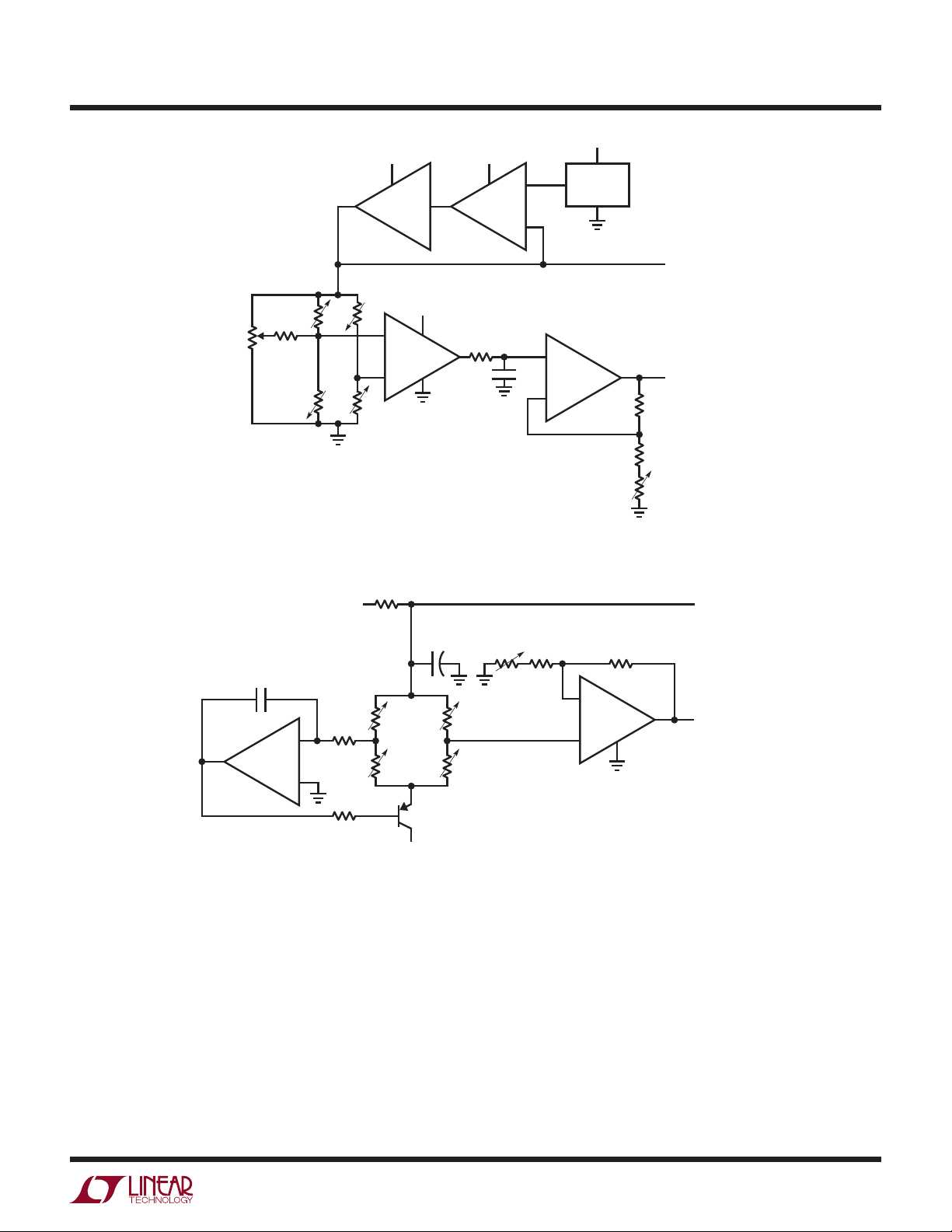

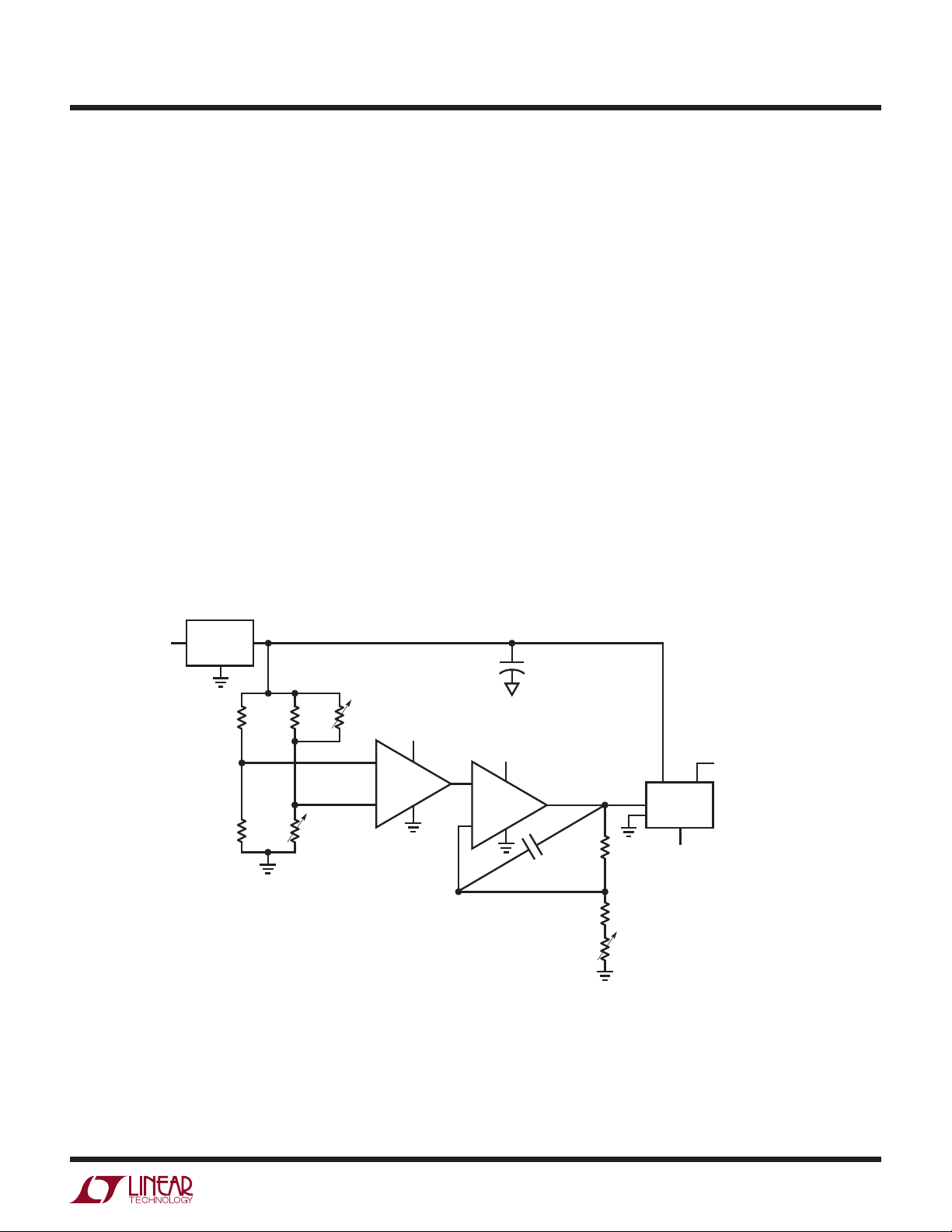

Figure 5, a typical bridge application, details signal conditioning for a 350Ω transducer bridge. The specified

strain gauge pressure transducer produces 3mV output

per volt of bridge excitation (various types of strain-based

transducers are reviewed in Appendix A, “Strain Gauge

®

Bridges”). The LT

1021 reference, buffered by A1A and

A2, drives the bridge. This potential also supplies the

circuits ratio output, permitting ratiometric operation of

a monitoring A/D converter. Instrumentation amplifier

A3 extracts the bridge’s differential output at a gain of

100, with additional trimmed gain supplied by A1B. The

configuration shown may be adjusted for a precise 10V

output at full-scale pressure. The trim at the bridge sets

the zero pressure scale point. The RC combination at A1B’s

input filters noise. The time constant should be selected

for the system’s desired lowpass cutoff. “Noise” may

originate as residual RF/line pick-up or true transducer

responses to pressure variations. In cases where noise

is relatively high it may be desirable to filter ahead of A3.

T h i s p r e v e n t s a n y p o s s i b l e s i g n a l i n f i d e l i t y d u e t o n o n l i n e a r

A3 operation. Such undesirable outputs can be produced

by saturation, slew rate components, or rectification

effects. When filtering ahead of the circuits gain blocks

remember to allow for the effects of bias current induced

errors caused by the filter’s series resistance. This can be

a significant consideration because large value capacitors,

particularly electrolytics, are not practical. If bias current

induced errors rise to appreciable levels FET or MOS input

amplifiers may be required (see Figure 3).

To trim this circuit apply zero pressure to the transducer

and adjust the 10k potentiometer until the output just

comes off 0V. Next, apply full-scale pressure and trim the

1k adjustment. Repeat this procedure until both points

are fixed.

Common Mode Suppression Techniques

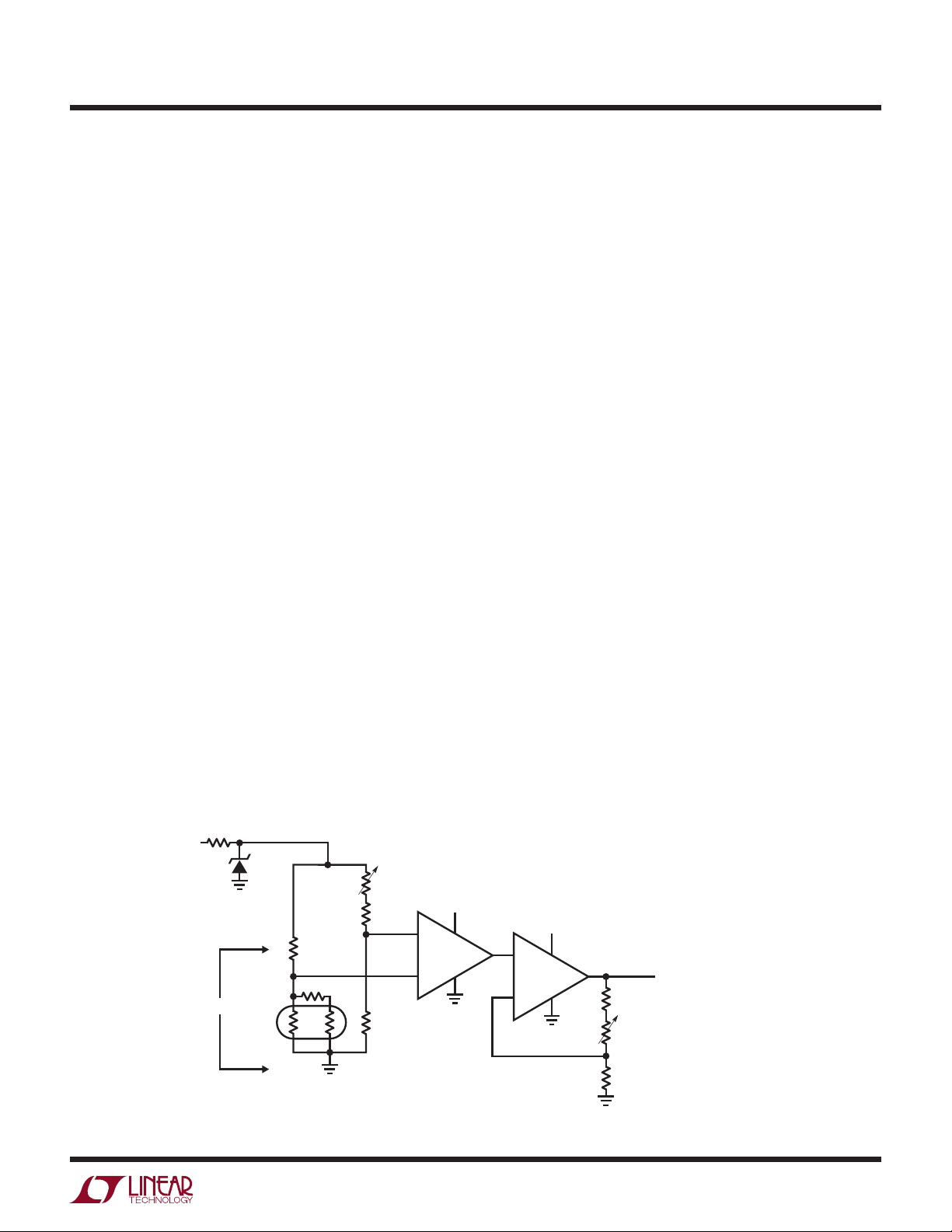

Figure 6 shows a way to reduce errors due to the bridges

common mode output voltage. A1 biases Q1 to servo the

bridges left mid-point to zero under all operating conditions. The 350Ω resistor ensures that A1 will find a stable

operating point with 10V of drive delivered to the bridge.

This allows A2 to take a single-ended measurement,

PARAMETER LTC1100 LT1101 LT1102

Offset

Offset Drift

Bias Current

Noise (0.1Hz to 10Hz)

Gain

Gain Error

Gain Drift

Gain Nonlinearity

CMRR

Power Supply

Supply Current

Slew Rate

Bandwidth

10μV

100nV/°C

50pA

2μV

P-P

100

0.03%

4ppm/°C

8ppm

104dB

Single or Dual, 16V Max

2.2mA

1.5V/μs

8kHz

Figure 3. Comparison of Some IC Instrumentation Amplifiers

160μV

2μV/°C

8nA

0.9μV

10,100

0.03%

4ppm/°C

8ppm

100dB

Single or Dual, 44V Max

105μA

0.07V/μs

33kHz

500μV

2.5μV/°C

50pA

2.8μV

10,100

0.05%

5ppm/°C

10ppm

100dB

Dual, 44V Max

5mA

25V/μs

220kHz

AN43-2

(USING LTC1050 AMPLIFIER)

LTC1043

0.5μV

50nV/°C

10pA

1.6μV

Resistor Programmable

Resistor Limited 0.001% Possible

Resistor Limited <1ppm/°C Possible

Resistor Limited 1ppm Possible

160dB

Single, Dual 18V Max

2mA

1mV/ms

10Hz

an43f

Page 3

Application Note 43

CONFIGURATION ADVANTAGES DISADVANTAGES

+V

RATIO

OUT

Best general choice. Simple,

straightforward. CMRR typically

>110dB, drift 0.05μV/°C to 2μV/°C,

gain accuracy 0.03%, gain drift

4ppm/°C, noise 10nV√Hz – 1.5μV

for chopper-stabilized types. Direct

ratiometric output.

AN43 F04a

+

–

INSTRUMENTATION

AMPLIFIER

OUT

CMRR, drift and gain stability

may not be adequate in highest

precision applications. May require

second stage to trim gain.

+V

RATIO

OUT

CMRR > 120dB, drift 0.05μV/°C.

Gain accuracy 0.001% possible.

Gain drift 1ppm with appropriate

resistors. Noise 10nV√Hz – 1.5μV

Multi-package—moderately

complex. Limited bandwidth.

Requires feedback resistors to set

gain.

for chopper-stabilized types. Direct

+

OUT

–

ratiometric output. Simple gain

trim. Flying capacitor commutation

provides lowpass filtering. Good

choice for very high performance—

monolithic versions (LTC1043)

available.

OP AMP

AN43 F04b

CMRR > 160dB, drift 0.05μV/°C to

0.25μV/°C, gain accuracy 0.001%

possible, gain drift 1ppm/°C with

appropriate resistors plus floating

Requires floating supply. No direct

ratiometric output. Floating supply

drift is a gain term. Requires

feedback resistors to set gain.

supply error, simple gain trim,

+

OUT

+

Noise 1nV√Hz possible.

–

OP AMP

+V

AN43 F04c

CMRR ≈ 140dB, drift 0.05μV/°C to

0.25μV/°C, gain accuracy 0.001%

possible, gain drift 1ppm/°C with

appropriate resistors plus floating

supply error, simple gain trim,

noise 1nV√Hz possible.

+

OUT

–

No direct ratiometric output.

Zener supply is a gain and offset

term error generator. Requires

feedback resistors to set gain.

Low impedance bridges require

substantial current from shunt

regulator or circuitry which

simulates it. Usually poor choice if

precision is required.

–V

OP AMP

AN43 F04d

Figure 4. Some Signal Conditioning Methods for Bridges

an43f

AN43-3

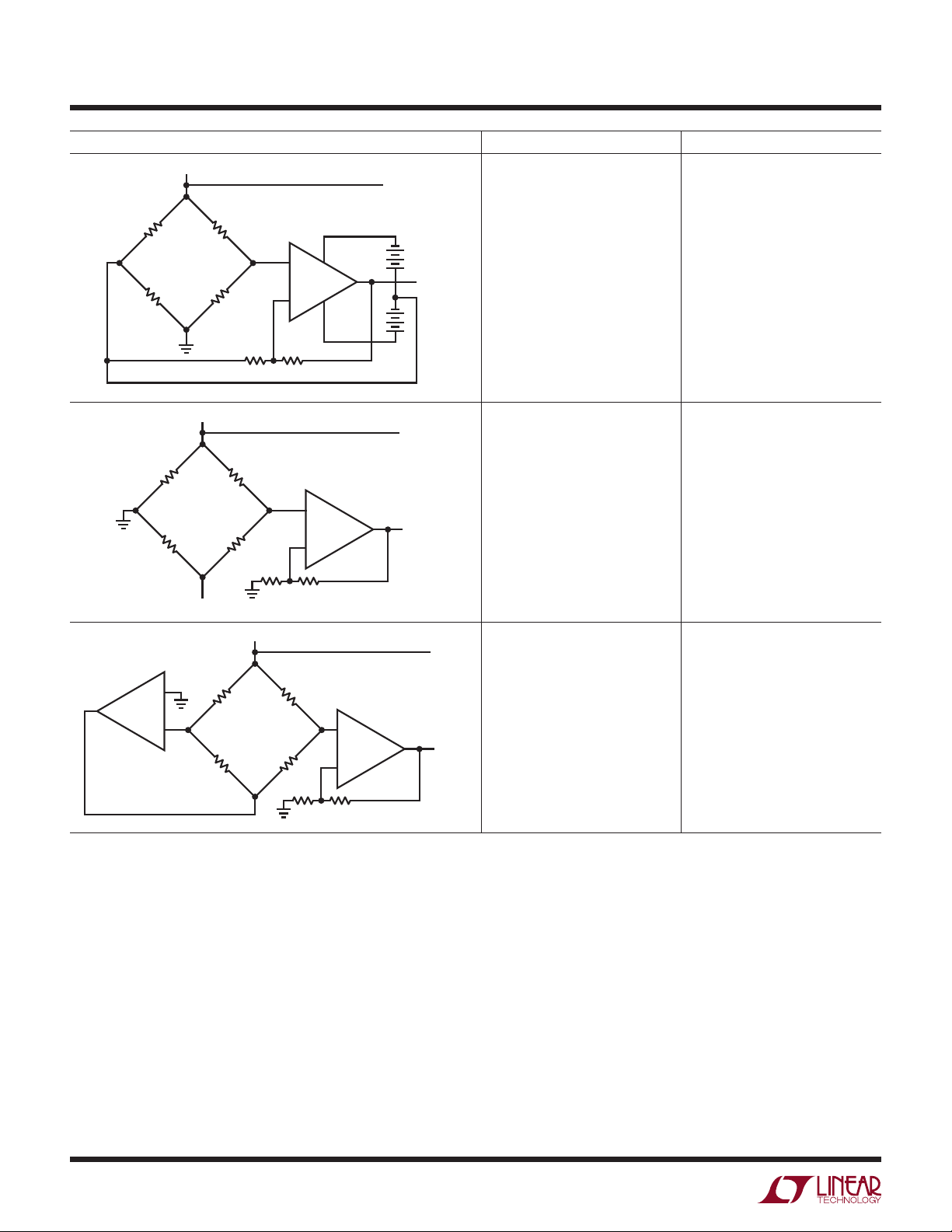

Page 4

Application Note 43

CONFIGURATION ADVANTAGES DISADVANTAGES

+V

+

–

OP AMP

RATIO

OUT

AN43 F04e

CMRR > 160dB, drift 0.05μV/°C to

0.25μV/°C, gain accuracy 0.001%

possible, gain drift 1ppm/°C with

appropriate resistors, simple gain

trim, ratiometric output, noise

1nV√Hz possible.

+

OUT

+

Requires precision analog level

shift, usually with isolation

amplifier. Requires feedback

resistors to set gain.

+V

+

–

–V

+

–

OP AMP

+V

+

–

OP AMP

AN43 F04f

RATIO

OUT

OUT

AN43 F04g

RATIO

OUT

OUT

CMRR ≈ 120dB to 140dB, drift

0.05μV/°C to 0.25μV/°C, gain

accuracy 0.001% possible, gain

drift 1ppm/°C with appropriate

resistors, simple gain trim, direct

ratiometric output, noise 1nV√Hz

possible.

CMRR = 160dB, drift 0.05μV/°C to

0.25μV/°C, gain accuracy 0.001%

possible, gain drift 1ppm/°C,

simple gain trim, direct ratiometric

output, noise 1nV√Hz possible.

Requires tracking supplies.

Assumes high degree of bridge

symmetry to achieve best CMRR.

Requires feedback resistors to set

gain.

Practical realization requires two

amplifiers plus various discrete

components. Negative supply

necessary.

Figure 4. Some Signal Conditioning Methods for Bridges (Continued)

eliminating all common mode voltage errors. This approach

works well, and is often a good choice in high precision

work. The amplifiers in this example, CMOS chopper-stabilized units, essentially eliminate offset drift with time and

temperature. Trade-offs compared to an instrumentation

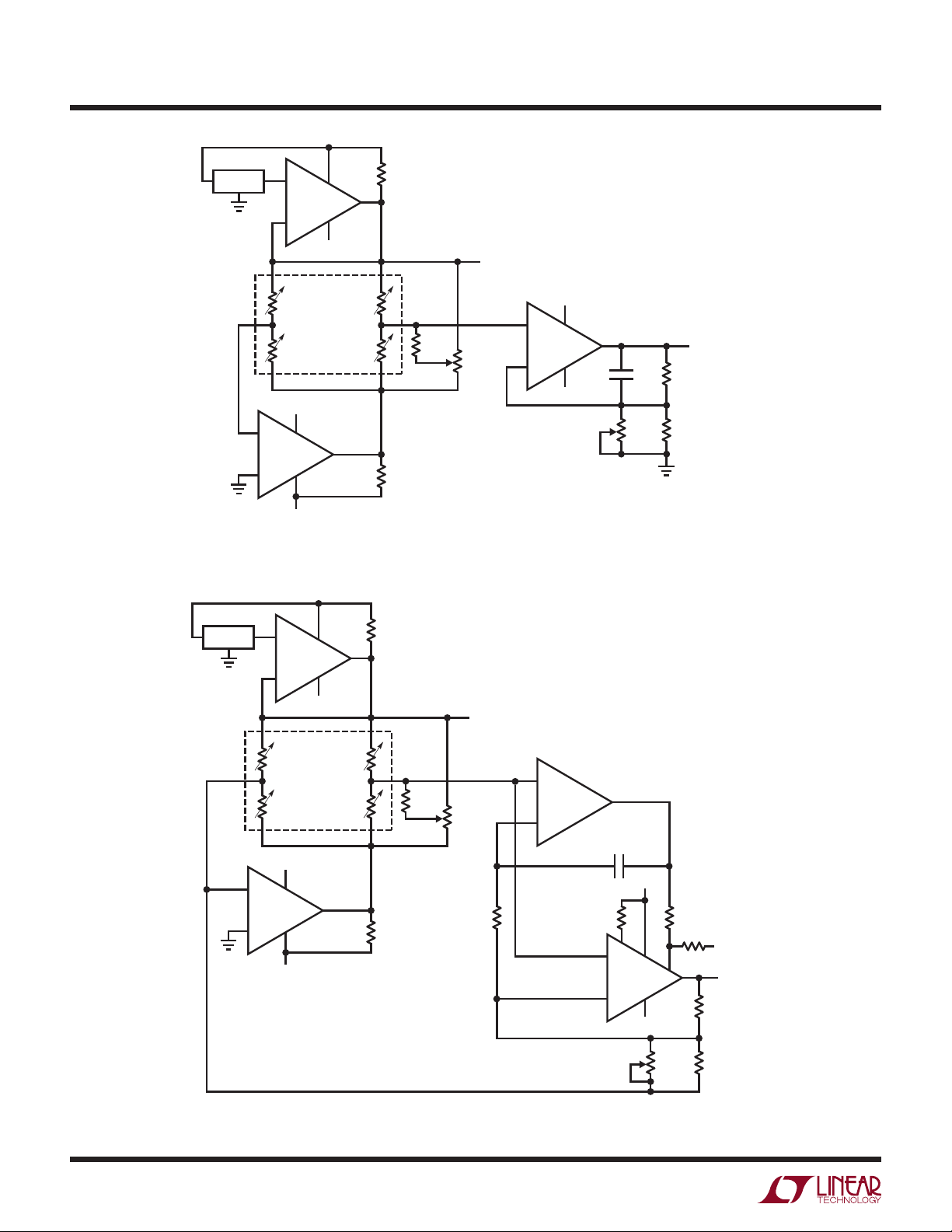

amplifier approach include complexity and the requirement for a negative supply. Figure 7 is similar, except that

low noise bipolar amplifiers are used. This circuit trades

slightly higher DC offset drift for lower noise and is a good

candidate for stable resolution of small, slowly varying

measurands. Figure 8 employs chopper-stabilized A1 to

AN43-4

reduce Figure 7’s already small offset error. A1 measures

the DC error at A2’s inputs and biases A1’s offset pins to

force offset to a few microvolts. The offset pin biasing at

A2 is arranged so A1 will always be able to find the servo

point. The 0.01μF capacitor rolls off A1 at low frequency,

with A2 handling high frequency signals. Returning A2’s

feedback string to the bridges mid-point eliminates A4’s

offset contribution. If this was not done A4 would require

a similar offset correction loop. Although complex, this

approach achieves less than 0.05μV/°C drift, 1nV√Hz noise

and CMRR exceeding 160dB.

an43f

Page 5

10k

ZERO

301k*

15V 15V

A2

LT1010

350Ω STRAIN GAGE

PRESSURE TRANSDUCER

15V

+

A3

LT1101

A = 100

–

1/2 LT1078

100k

A1A

+

–

0.33

LT1021

+

A1B

1/2 LT1078

–

Application Note 43

15V

10V

10V RATIO

OUTPUT

OUTPUT

0V TO 10V =

0 TO 250 PSI

10k*

*1% FILM RESISTOR

PRESSURE TRANSDUCER =

BLH #DHF-350—3MV/VOLT GAIN FACTOR

Figure 5. A Practical Instrumentation Amplifier-Based Bridge Circuit

0.02

A1

LTC1150

*1% FILM RESISTOR

Figure 6. Servo Controlling Bridge Drive Eliminates Common Mode Voltage

3.65k*

1k – GAIN

AN43 F05

350Ω

15V

1/2W

10μF

+

OUTPUT

TRIM

100Ω

250* 100k*

RATIO

OUTPUT

–

350Ω

100k

–

+

1k

STRAIN

GAUGE

BRIDGE

3MV/V

TYPE

Q1

2N2905

–15V

LTC1150

+

A2

AN43 F06

OUTPUT

0V TO 10V

Single Supply Common Mode Suppression Circuits

The common mode suppression circuits shown require a

negative power supply. Often, such circuits must function

in systems where only a positive rail is available. Figure 9

®

shows a way to do this. A2 biases the LTC

1044 positiveto-negative converter. The LTC1044’s output pulls the

bridge’s output negative, causing A1’s input to balance at

0V. This local loop permits a single-ended amplifier (A2)

to extract the bridge’s output signal. The 100k-0.33μF RC

filters noise and A2’s gain is set to provide the desired

output scale factor. Because bridge drive is derived from

the LT1034 reference, A2’s output is not affected by supply

shifts. The LT1034’s output is available for ratio operation.

Although this circuit works nicely from a single 5V rail the

transducer sees only 2.4V of drive. This reduced drive

an43f

AN43-5

Page 6

Application Note 43

15V

LT1021-5

350Ω

BRIDGE

3

5V

2

2

–

A3

LT1028

3

+

–15V

+

–

15V

7

A1

LT1007

4

–15V

7

6

4

330Ω

6

RATIO

REFERENCE

OUT

15V

330Ω

301k*

10k

ZERO

TRIM

*1% FILM RESISTOR

3

2

+

LT1028

–

A3

–15V

7

6

4

1μF

5k

GAIN

TRIM

Figure 7. Low Noise Bridge Amplifier with Common Mode Suppression

15V

0V TO 10V

OUTPUT

30.1k*

49.9Ω*

AN43 F07

LT1021-5

350Ω

BRIDGE

*1% FILM RESISTOR

3

+

5V

2

–

15V

2

–

A4

LT1028

3

+

–15V

A3

LT1007

7

4

–15V

7

4

330Ω

6

REFERENCE

OUT

+

301k*

10k

ZERO

TRIM

6

330Ω

A1

LTC1150

–

0.01

15V

130Ω100k 30k

1

7

+

LT1028

–

A2

–15V

8

4

5k

GAIN

TRIM

68Ω

15V

OUTPUT

30.1k*

(A = 1000)

49.9Ω*

AN43 F08

AN43-6

Figure 8. Low Noise, Chopper-Stabilized Bridge Amplifier with Common Mode Suppression

an43f

Page 7

Application Note 43

1.2V REFERENCE OUTPUT

TO A/D CONVERTER

FOR RATIOMETRIC

OPERATION. 0.1mA MAXIMUM

10k

ZERO

TRIM

+

A2

1/2 LT1078

39k

0.1μF

–

A1

1/2 LT1078

5V

220

LT1034

1.2V

+

PRESSURE

TRANSDUCER

350Ω

D

E A

C

2.4V

301k

100k

0.33μF

–

100μF

8

+

V

2

+

CAP

+

3

LTC1044

CAP

GND

V

–

OUT

5

LV

100μF

+

64

*1% FILM RESISTOR

PRESSURE TRANSDUCER-BLH/DHF-350

CIRCLED LETTER IS PIN NUMBER

= 350Ω

Z

IN

0.047μF

Figure 9. Single Supply Bridge Amplifier with Common Mode Suppression

OUTPUT

0V TO 3.5V =

0 TO 350 PSI

2k

GAIN

TRIM

46k*

100Ω*

AN43 F09

40Ω

5V

10μF

+

5k

OUTPUT

TRIM

5k*

1M*

–

A2

1/2 LT1078

+

OUTPUT

0V TO 3V

AN43 F10

10μF

350Ω

3k

STRAIN

GAUGE

BRIDGE

3mV/V

TYPE

Q2

2N2222

100k

+

A1

1/2 LT1078

0.02

200k

1

FB/SD

2

+

+

CAP

LT1054

3

GND

4

–

CAP

V

*1% FILM RESISTOR

OUT

5V

8

+

V

+

5

–

100μF

SOLID

TANTALUM

100k

100μF

+

8V

10k

1μF

Figure 10. High Resolution Version of Figure 9. Bipolar Voltage Converter Gives Greater Bridge Drive, Increasing Output Signal

results in lower transducer outputs for a given measurand

value, effectively magnifying amplifier offset drift terms.

The limit on available bridge drive is set by the CMOS

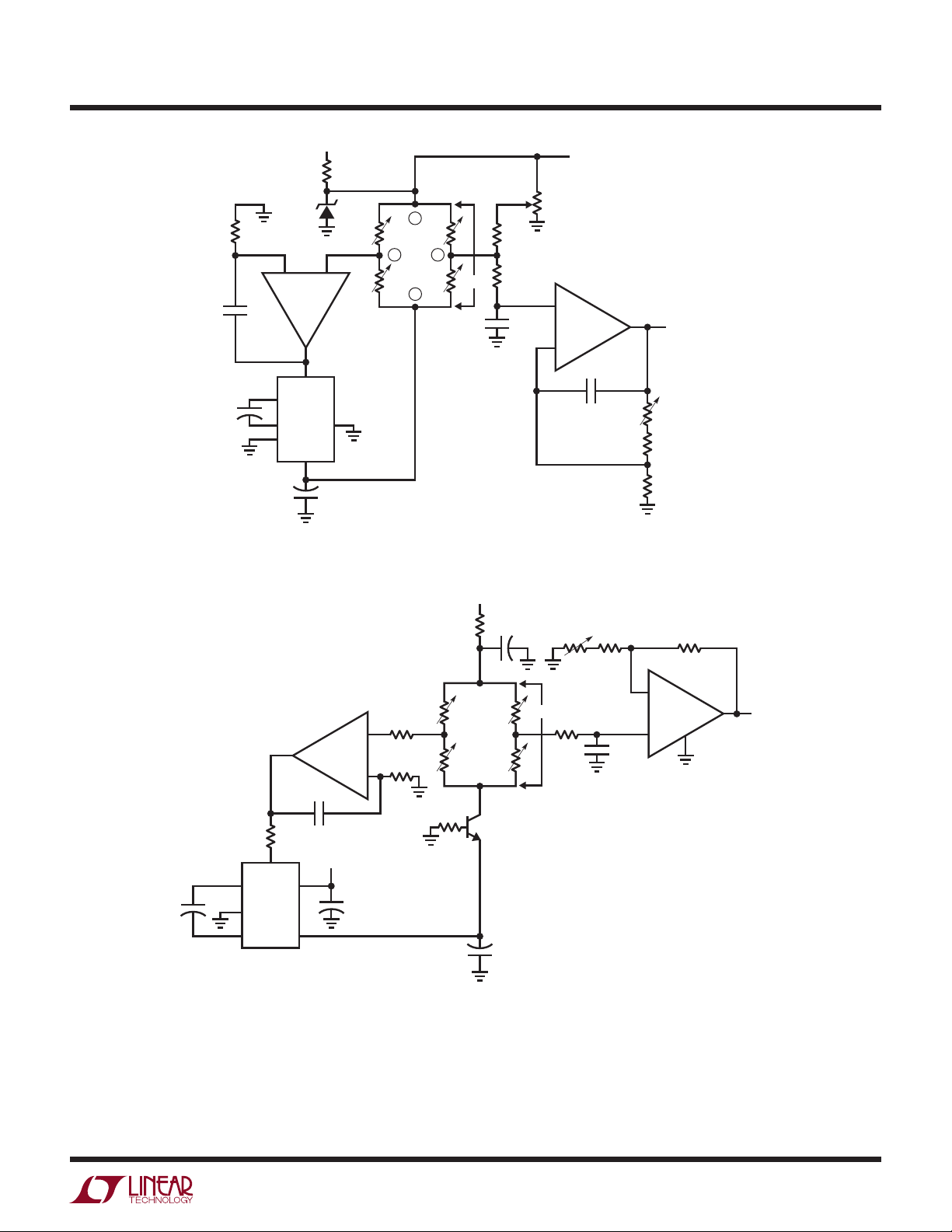

LTC1044’s output impedance. Figure 10’s circuit employs

a bipolar positive-to-negative converter which has much

lower output impedance. The biasing used permits 8V to

appear across the bridge, requiring the 100mA capability

LT1054 to sink about 24mA. This increased drive results

in a more favorable transducer gain slope, increasing

signal-to-noise ratio.

an43f

AN43-7

Page 8

Application Note 43

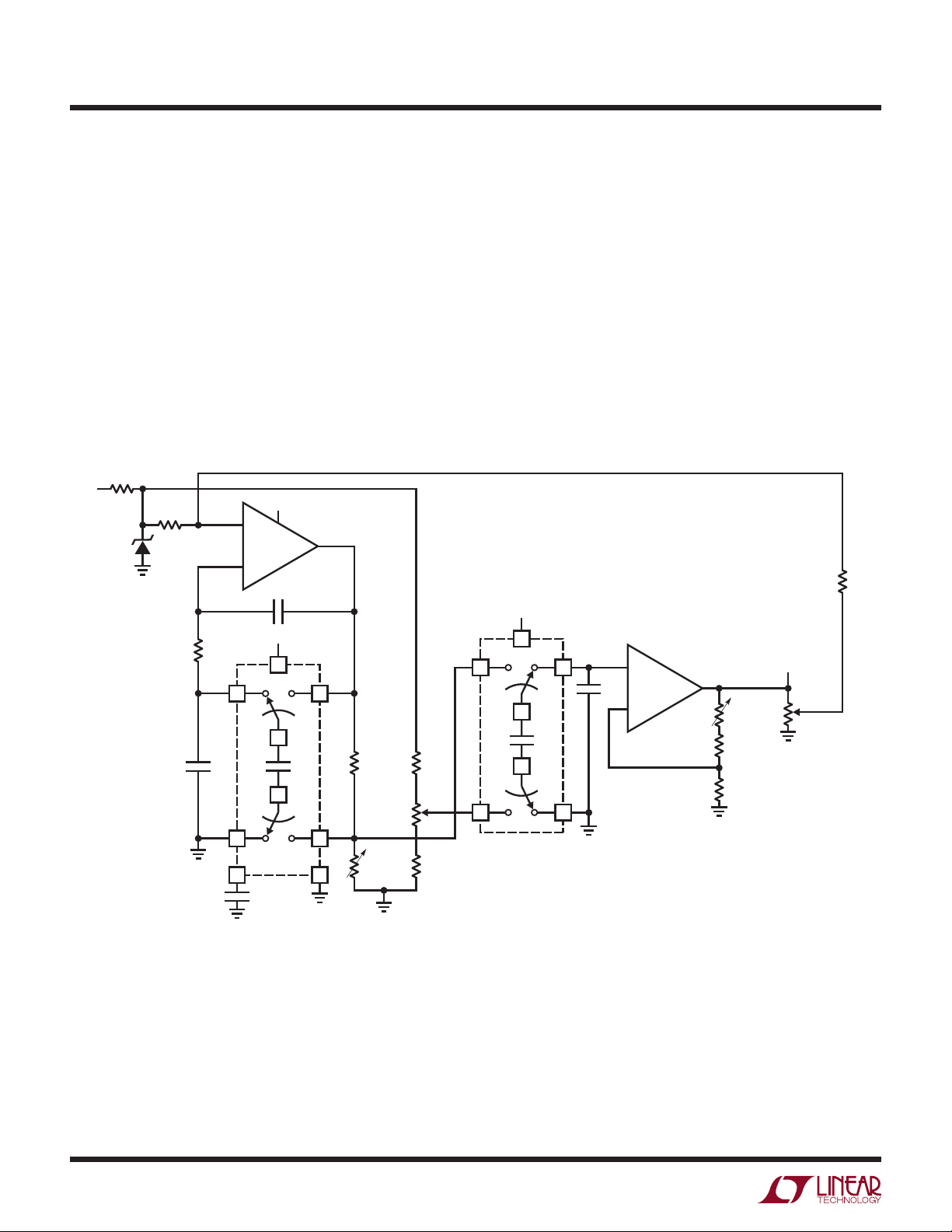

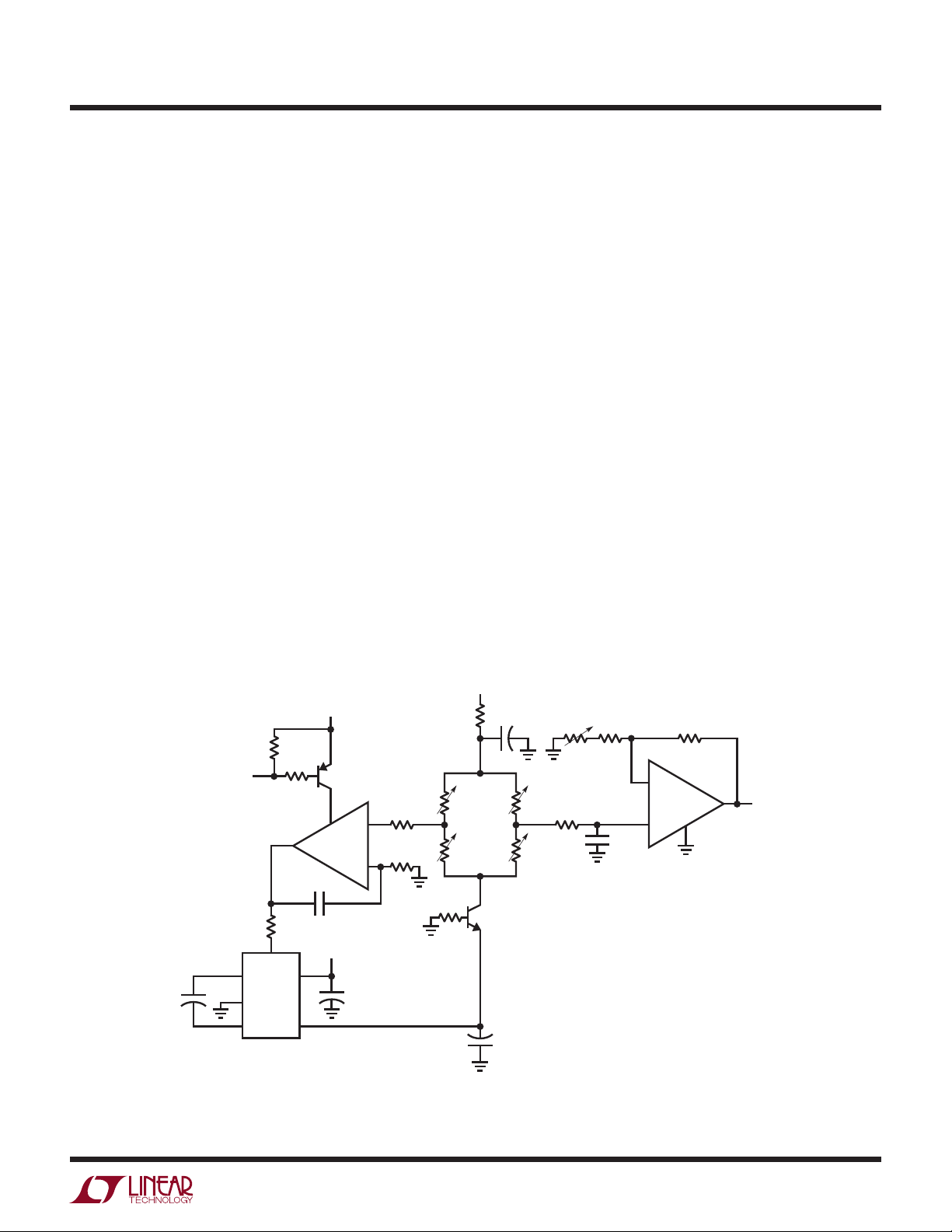

Switched-Capacitor Based Instrumentation Amplifiers

Switched-capacitor methods are another way to signal

condition bridge outputs. Figure 11 uses a flying capacitor

configuration in a very high precision-scale application. This

design, intended for weighing human subjects, will resolve

0.01 pound at 300.00 pounds full scale. The strain gauge

based transducer platform is excited at 10V by the LT1021

reference, A1 and A2. The LTC1043 switched-capacitor

building block combines with A3, forming a differential

input chopper-stabilized amplifier. The LTC1043 alternately

connects the 1μF flying capacitor between the strain gauge

bridge output and A3’s input. A second 1μF unit stores

the LTC1043 output, maintaining A3’s input at DC. The

LTC1043’s low charge injection maintains differential to

single-ended transfer accuracy of about 1ppm at DC and

low frequency. The commutation rate, set by the 0.01μF

capacitor, is about 400Hz. A3 takes scaled gain, providing

3.0000V for 300.00 pounds full-scale output.

15V

15V

LT1021

10V

+

–

7

13

A1

LT1012

LTC1043

15V

4

11

1μF

12

16 17

0.01

14

8

A2

LT1010

301k

1% FILM

1μF

5.8k*

2.5k

ZERO

80k*

15V

+

A3

LTC1150

–

0.68μF

10k

1% FILM

50k

GAIN

0.68/2μF = POLYSTYRENE

* = ULTRONIX 105A RESISTOR

STRAIN BRIDGE PLATFORM = NCI 3224

15k

25Ω

135k* 1k

1k*

100k

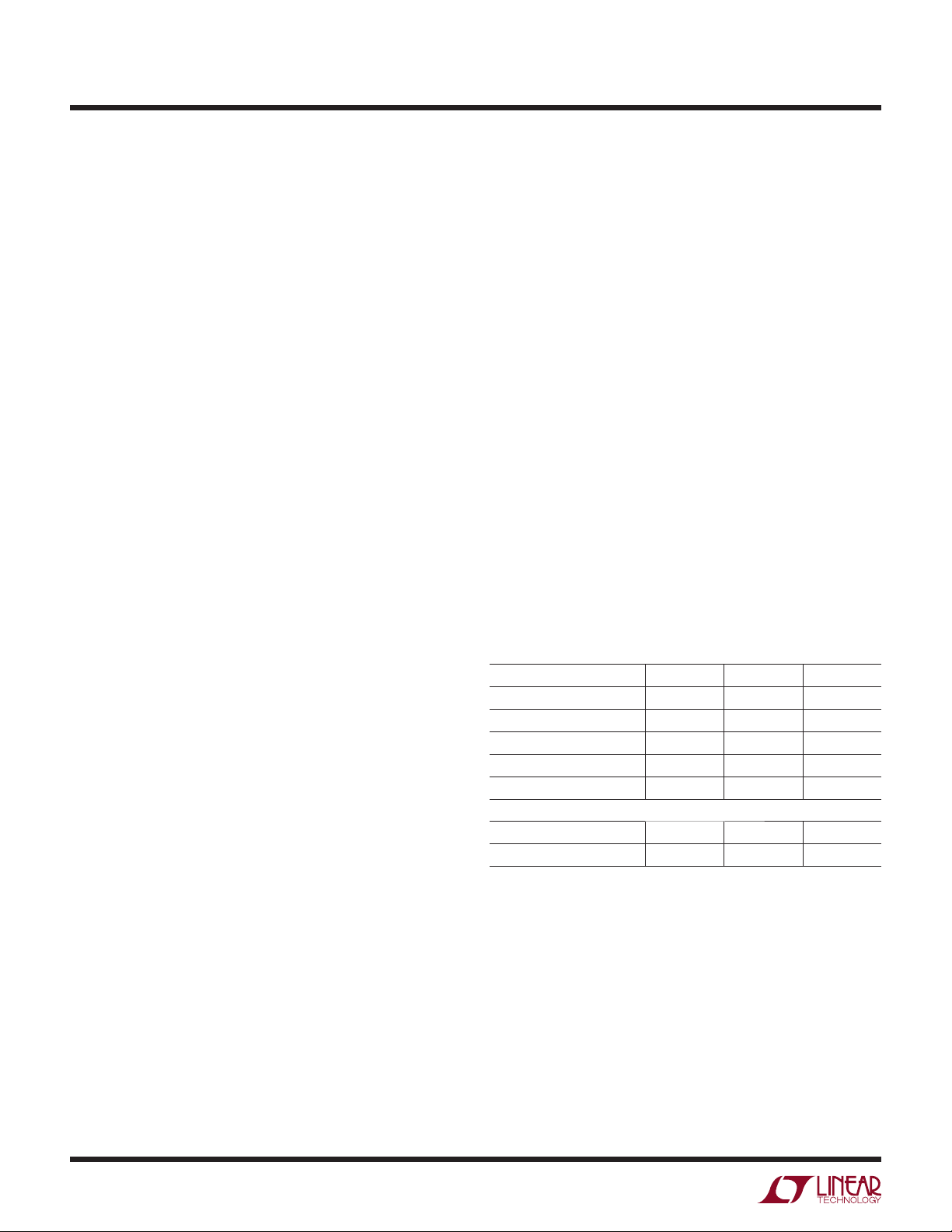

The extremely high resolution of this scale requires filtering

to produce useful results. Very slight body movement acting

on the platform can cause significant noise in A3’s output.

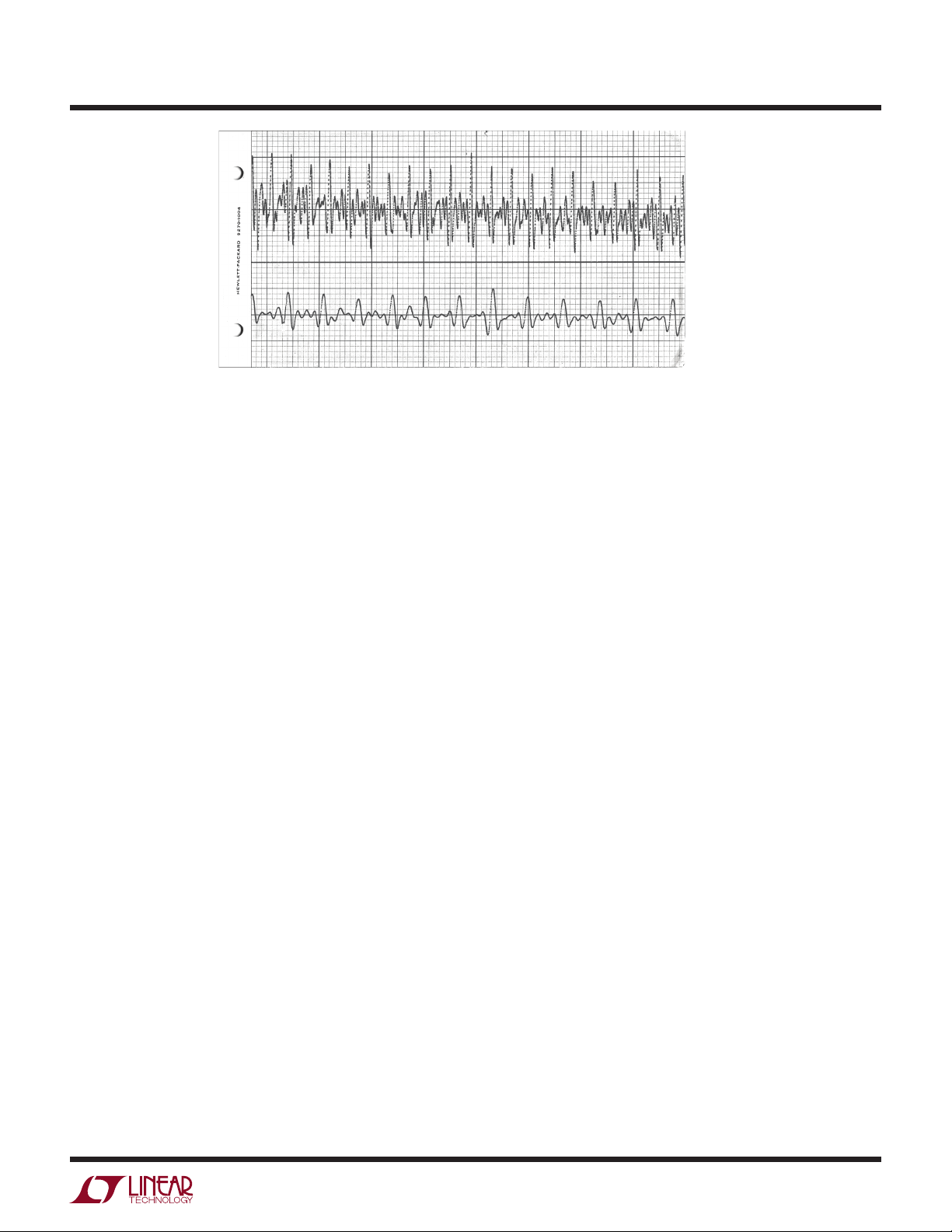

This is dramatically apparent in Figure 12’s tracings. The

total force on the platform is equal to gravity pulling on

the body (the “weight”) plus any additional accelerations

within or acting upon the body. Figure 12 (Trace B) clearly

shows that each time the heart pumps, the acceleration due

to the blood (mass) moving in the arteries shows up as

“weight”. To prove this, the subject gets off the scale and

runs in place for 15 seconds. When the subject returns to

the platform the heart should work harder. Trace A confirms

this nicely. The exercise causes the heart to work harder,

forcing a greater acceleration-per-stroke.

Note 2: Cardiology aficionados will recognize this as a form of

Ballistocardiograph (from the Greek “ballein”—to throw, hurl or eject

and “kardia,” heart). A significant amount of effort was expended in

attempts to reliably characterize heart conditions via acceleration detection

methods. These efforts were largely unsuccessful when compared against

the reliability of EKG produced data. See references for further discussion.

15V

–

A5A

1/2 LT1018

+

–

LT1012

+

15V

–

A5B

1/2 LT1018

+

RC FILTER

680k

39k 2μF

2k

2

10V RATIO

OUTPUT

HEARTBEAT

OUTPUT

A4

WEIGHT

OUTPUT

0V TO 3.0000V =

0LB TO 300.00LB

AN43 F11

AN43-8

= HEWLETT-PACKARD HSSR-8200

Figure 11. High Precision Scale for Human Subjects

an43f

Page 9

A = 0.45LB/FULL SCALE

B = 0.45LB/FULL SCALE

Application Note 43

HORIZ = 1s/INCH

Figure 12. High Precision Scale’s Heartbeat Output. Trace B Shows Subject at Rest; Trace A After Exercise. Discontinuous Components

in Waveforms Leading Edges Are Due to XY Recorder Slew Limitations

Another source of noise is due to body motion. As the

body moves around, its mass doesn’t change but the

instantaneous accelerations are picked up by the platform

and read as “weight” shifts.

All this seems to make a 0.01 pound measurement meaningless. However, filtering the noise out gives a time averaged value. A simple RC lowpass will work, but requires

excessively long settling times to filter noise fundamentals

in the 1Hz region. Another approach is needed.

A4, A5 and associated components form a filter which

switches its time constant from short to long when the

output has nearly arrived at the final value. With no weight

on the platform A3’s output is zero. A4’s output is also

zero, A5B’s output is indeterminate and A5A’s output is

low. The MOSFET opto-couplers LED comes on, putting the

RC filter into short time constant mode. When someone

gets on the scale A3’s output rises rapidly. A5A goes high,

but A5B trips low, maintaining the RC filter in its short

time constant mode. The 2μF capacitor charges rapidly,

the 2μF capacitor, returning A4’s output rapidly to zero.

The bias string at A5A’s input maintains the scale in fast

time constant mode for weights below 0.50 pounds. This

permits rapid response when small objects (or persons)

are placed on the platform. To trim this circuit, adjust

the zero potentiometer for 0V out with no weight on the

platform. Next, set the gain adjustment for 3.0000V out

for a 300.00 pound platform weight. Repeat this procedure

until both points are fixed.

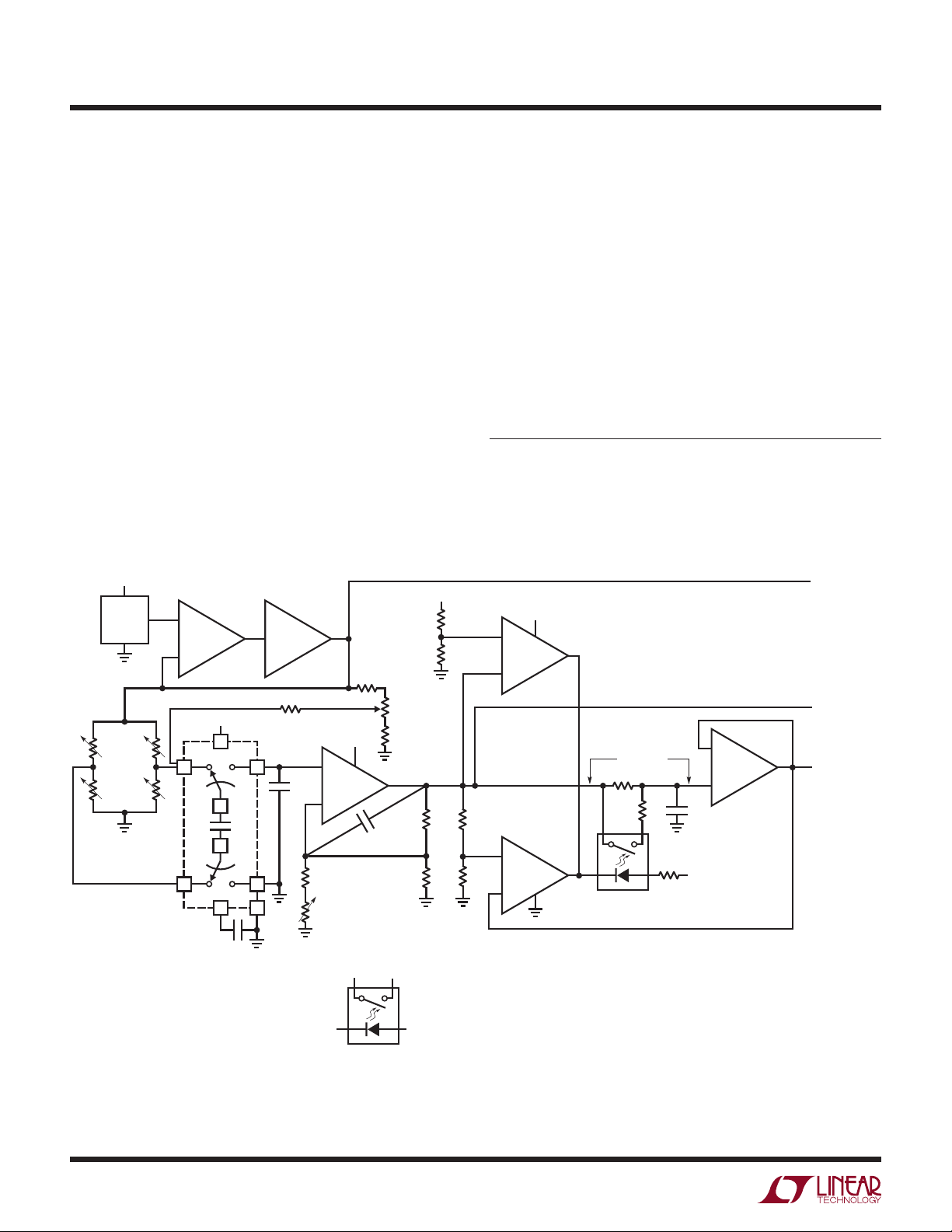

Optically Coupled Switched-Capacitor

Instrumentation Amplifier

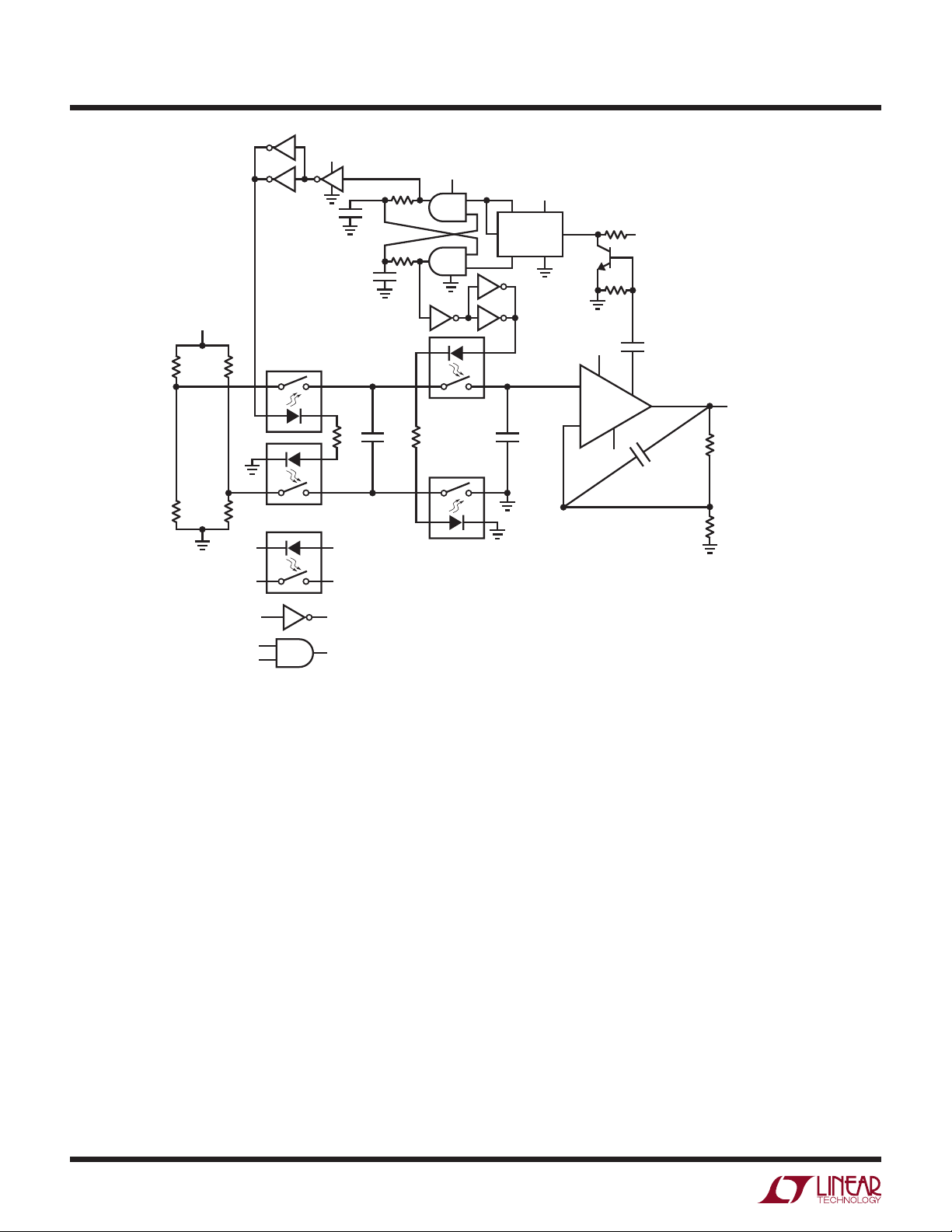

Figure 13 also uses optical techniques for performance

enhancement. This switched-capacitor based instrumentation amplifier is applicable to transducer signal

conditioning where high common mode voltages exist.

The circuit has the low offset and drift of the LTC1150

but also incorporates a novel switched-capacitor “front

end” to achieve some specifications not available in a

conventional instrumentation amplifier.

AN43 F12

and A4 quickly settles to final value ± body motion and

heartbeat noise. A5B’s negative input sees 1% attenuation

from A3; its positive input does not. This causes A5B to

switch high when A4’s output arrives within 1% of final

value. The opto-coupler goes off and the filter switches

into long time constant mode, eliminating noise in A4’s

output. The 39k resistor prevents overshoot, ensuring

monotonic A4 outputs. When the subject steps off the

scale A3 quickly returns to zero. A5A goes immediately

Common mode rejection ratio at DC for the front end

exceeds 160dB. The amplifier will operate over a ±200V

common mode range and gain accuracy and stability are

limited only by external resistors. A1, a chopper stabilized

unit, sets offset drift at 0.05μV/°C. The high common

mode voltage capability of the design allows it to withstand transient and fault conditions often encountered in

industrial environments.

low, turning on the opto-coupler. This quickly discharges

an43f

AN43-9

Page 10

Application Note 43

15V

ACQUIRE

0.05

10k

10k

0.05

15V

15V

Q

74C74

DCK

÷ 4

Q

2N3904

10k

10k

15V

+E BRIDGE

+

S1

C1

2k 2k

1μF

S2

–

= HEWLETT-PACKARD HSSR-8200

= 1/6 74C04

= 1/4 74C02

* = 1% FILM RESISTOR

Figure 13. Floating Input Bridge Instrumentation Amplifier with 200V Common Mode Range

The circuit’s inputs are fed to LED-driven optically-coupled

MOSFET switches, S1 and S2. Two similar switches, S3

and S4, are in series with S1 and S2. CMOS logic functions, clocked from A1’s internal oscillator, generate nonoverlapping clock outputs which drive the switch’s LEDs.

When the “acquire pulse” is high, S1 and S2 are on and

C2 acquires the differential voltage at the bridge’s output.

During this interval, S3 and S4 are off. When the acquire

pulse falls, S1 and S2 begin to go off. After a delay to allow

S1 and S2 to fully open, the “read pulse” goes high, turning on S3 and S4. Now C1 appears as a ground-referred

voltage source which is read by A1. C2 allows A1’s input

to retain C1’s value when the circuit returns to the acquire

mode. A1 provides the circuit’s output. Its gain is set in

normal fashion by feedback resistors. The 0.33μF feedback

capacitor sets roll-off. The differential-to-single-ended

transition performed by the switches and capacitors means

that A1 never sees the input’s common mode signal. The

READ

S3

15V

+

LTC1150

C2

1μF

S4

–

A1

–15V

100pF

CLK OUT

OUTPUT

100k*

0.33

100Ω*

AN43 F13

breakdown specification of the optically-driven MOSFET

switch allows the circuit to withstand and operate at common mode levels of ±200V. In addition, the optical drive

to the MOSFETs eliminates the charge injection problems

common to FET switched-capacitive networks.

Platinum RTD Resistance Bridge Circuits

Platinum RTDs are frequently used in bridge configurations for temperature measurement. Figure 14’s circuit is

highly accurate and features a ground referred RTD. The

ground connection is highly desirable for noise rejection.

The bridges RTD leg is driven by a current source while

the opposing bridge branch is voltage biased. The current

drive allows the voltage across the RTD to vary directly with

its temperature induced resistance shift. The difference

between this potential and that of the opposing bridge leg

forms the bridges output.

an43f

AN43-10

Page 11

15V

27k

10k*

LT1009

2.5V

2k

* = 1% FILM RESISTOR

= ROSEMOUNT 118MFRTD

R

P

15V

+

A1A

1/2 LT1078

–

0.1μF

LT1101

A = 10

Application Note 43

274k*

15V

88.7Ω*

R

P

100Ω AT

0°C RTD

50k

ZERO

8.25k*

–

LT1101

A = 10

+

A3

LINEARITY

+

A2

–

250k*

+

5k

A1B

1/2 LT1078

–

0V TO 10V

0°C TO 400°C ±0.05°C

2k

GAIN

13k*

10k*

AN43 F14

OUT

=

Figure 14. Linearized Platinum RTD Bridge. Feedback to Bridge from A3 Linearizes the Circuit

A1A and instrumentation amplifier A2 form a voltage-controlled current source. A1A, biased by the LT1009 reference, drives current through the 88.7Ω resistor and the

RTD. A2, sensing differentially across the 88.7Ω resistor,

closes a loop back to A1A. the 2k-0.1μF combination sets

amplifier roll-off, and the configuration is stable. Because

A1A’s loop forces a fixed voltage across the 88.7Ω resistor,

the current through R

is constant. A1’s operating point is

P

primarily fixed by the 2.5V LT1009 voltage reference.

The RTD’s constant current forces the voltage across it

to vary with its resistance, which has a nearly linear positive temperature coefficient. The nonlinearity could cause

several degrees of error over the circuit’s 0°C to 400°C

operating range. The bridges output is fed to instrumentation amplifier A3, which provides differential gain while

simultaneously supplying nonlinearity correction. The

correction is implemented by feeding a portion of A3’s

output back to A1’s input via the 10k-250k divider. This

causes the current supplied to R

to slightly shift with

P

its operating point, compensating sensor nonlinearity to

within ±0.05°C. A1B, providing additional scaled gain,

furnishes the circuit output.

To calibrate this circuit, substitute a precision decade

box (e.g., General Radio 1432k) for R

. Set the box to

P

the 0°C value (100.00Ω) and adjust the offset trim for a

0.00V output. Next, set the decade box for a 140°C output

(154.26Ω) and adjust the gain trim for a 3.500V output

reading. Finally, set the box to 249.0Ω (400.00°C) and trim

the linearity adjustment for a 10.000V output. Repeat this

sequence until all three points are fixed. Total error over

the entire range will be within ±0.05°C. The resistance

values given are for a nominal 100.00Ω (0°C) sensor.

Sensors deviating from this nominal value can be used

by factoring in the deviation from 100.00Ω. This deviation, which is manufacturer specified for each individual

sensor, is an offset term due to winding tolerances during

fabrication of the RTD. The gain slope of the platinum is

primarily fixed by the purity of the material and has a very

small error term.

an43f

AN43-11

Page 12

Application Note 43

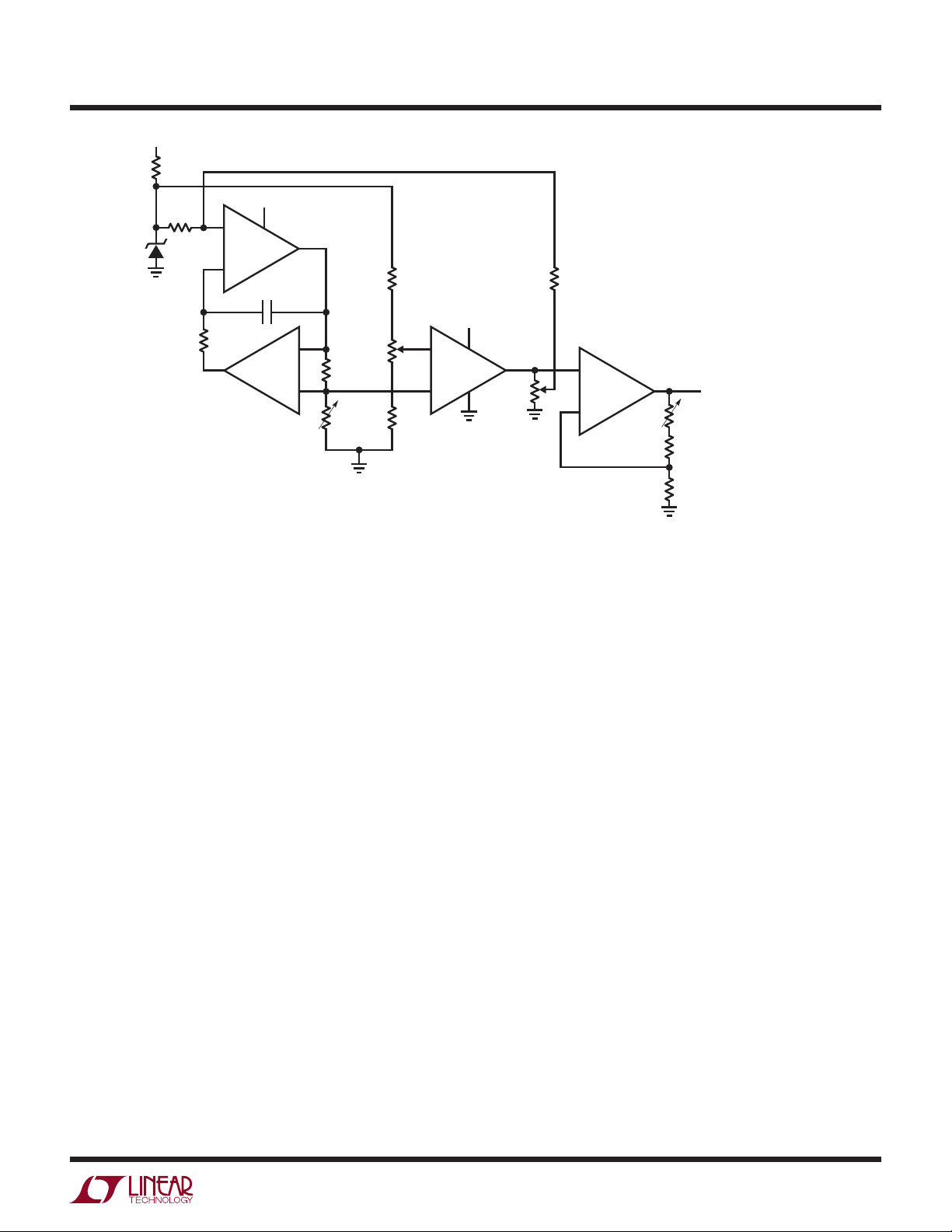

Figure 15 is functionally identical to Figure 14, except that

A2 and A3 are replaced with an LTC1043 switched-capacitor

building block. The LTC1043 performs the differentialto-single-ended transitions in the current source and

bridge output amplifier. Value shifts in the current source

and output stage reflect the LTC1043’s lack of gain. The

primary trade-off between the two circuits is component

count versus cost.

Digitally Corrected Platinum Resistance Bridge

The previous examples rely on analog techniques to

achieve a precise, linear output from the platinum RTD

bridge. Figure 16 uses digital corrections to obtain similar results. A processor is used to correct residual RTD

27k

15V

10k*

LT1009

2.5V

15V

+

1/2 LT1078

–

0.1μF

nonlinearities. The bridges inherent nonlinear output is

also accommodated by the processor.

The LT1027 drives the bridge with 5V. The bridge differential

output is extracted by instrumentation amplifier A1. A1’s

output, via gain scaling stage A2, is fed to the LTC1290

12-bit A/D. The LTC1290’s raw output codes reflect the

bridges nonlinear output versus temperature. The processor corrects the A/D output and presents linearized,

calibrated data out. RTD and resistor tolerances mandate

zero and full-scale trims, but no linearity correction is

necessary. A2’s analog output is available for feedback

control applications. The complete software code for the

68HC05 processor, developed by Guy M. Hoover, appears

in Figure 17.

250k*

15V

2k

1μF

15V

4

7

13

0.01μF

8

11

1μF

12

14

1716

887Ω*

R

P

100Ω

AT 0°C

274k*

50k

ZERO

8.25k*

4

1/2 LTC1043

5

2

3

15

* = 1% FILM RESISTOR

R

6

1μF

18

= ROSEMOUNT 118MFRTD

P

5

1μF

6

+

1/2 LT1078

–

GAIN

ADJUST

0°C TO 400°C ±0.05°C

7

2k

LINEARITY

13k*

619Ω*

AN43 F15

0V TO 10V

5k

OUT

=

Figure 15. Switched-Capacitor-Based Version of Figure 14

AN43-12

an43f

Page 13

Application Note 43

Thermistor Bridge

Figure 18, another temperature measuring bridge, uses

a thermistor as a sensor. The LT1034 furnishes bridge

excitation. The 3.2k and 6250Ω resistors are supplied

with the thermistor sensor. The networks overall response

is linearly related to the thermistor’s sensed temperature.

The network forms one leg of a bridge with resistors furnishing the opposing leg. A trim in this opposing leg sets

bridge output to zero at 0°C. Instrumentation amplifier A1

takes gain with A2 providing additional trimmed gain to

furnish a calibrated output. Calibration is accomplished

in similar fashion to the platinum RTD circuits, with the

linearity trim deleted.

Low Power Bridge Circuits

Low power operation of bridge circuits is becoming increasingly common. Many bridge-based transducers are low

impedance devices, complicating low power design. The

most obvious way to minimize bridge power consumption

is to restrict drive to the bridge. Figure 19a is identical to

Figure 5, except that the bridge excitation has been reduced to 1.2V. This cuts bridge current from nearly 30mA

to about 3.5mA. The remaining circuit elements consume

negligible power compared to this amount. The trade-off

is the sacrifice in bridge output signal. The reduced drive

causes commensurately lowered bridge outputs, making

the noise and drift floor a greater percentage of the signal.

More specifically, a 0.01% reading of a 10V powered 350Ω

strain gauge bridge requires 3μV of stable resolution. At

1.2V drive, this number shrinks to a scary 360nV.

Figure 19b is similar, although bridge current is reduced

below 700μA. This is accomplished by using a semiconductor-based bridge transducer. These devices have

significantly higher input resistance, minimizing power

dissipation. Semiconductor-based pressure transducers

have major cost advantages over bonded strain gauge

types, although accuracy and stability are reduced. Appendix A, “Strain Gauge Bridges,” discusses trade-offs

and theory of both technologies.

5V

12k*

1k*

OUT

12.5k*

500k

ZERO°C

TRIM

–

+

R

PLAT

*TRW-IRC MAR-6 RESISTOR—0.1%

**1% FILM RESISTOR

= 1kΩ AT 0°C—ROSEMOUNT #118MF

R

PLAT

15V

A1

LT1101

A = 10

+

LT1006

–

+

10μF

15V

V

A2

30.1k**

1μF

3.92M**

AN43 F16

LTC1290

500k

400°C

TRIM

REF

+V

15V

SERIAL OUT TO

68HC05 PROCESSOR

LT102715V

Figure 16. Digitally Linearized Platinum RTD Signal Conditioner

an43f

AN43-13

Page 14

Application Note 43

* PLATINUM RTD LINEARIZATION PROGRAM (0.0 TO 400.0 DEGREES C)

* WRITTEN BY GUY HOOVER LINEAR TECHNOLOGY CORPORATION

* 3/14/90

* N IS THE NUMBER OF SEGMENTS THAT RTD RESPONSE IS DIVIDED INTO

* TEMPERATURE (DEG. C*10)=M*X+B

* M IS SLOPE OF RTD RESPONSE FOR A GIVEN SEGMENT

* X IS A/D OUTPUT MINUS SEGMENT END POINT

* B IS SEGMENT START POINT IN DEGREES C *10.

*

*****************************************************************************************

* LOOK UP TABLES

*

ORG $1000

* TABLE FOR SEGMENT END POINTS IN DECIMAL

* X IS FORMED BY SUBTRACTING PROPER SEGMENT END POINT FROM A/D OUTPUT

FDB 60,296,527,753,976,1195,1410,1621,1829,2032

FDB 2233,2430,2623,2813,3000,3184,3365,3543,3718,3890

ORG $1030

* TABLE FOR M IN DECIMAL

* M IS SLOPE OF RTD OVER A GIVEN TEMPERATURE RANGE

FDB 3486,3535,3585,3685,3735,3784,3884,3934,3984,4083

FDB 4133,4232,4282,4382,4432,4531,4581,4681,4730,4830

ORG $1060

* TABLE FOR B IN DECIMAL

* B IS DEGREES C TIMES TEN

FDB 0,200,400,600,800,1000,1200,1400,1600,1800

FDB 2000,2200,2400,2600,2800,3000,3200,3400,3600,3800

ORG $10FF

FCB 39 (N*2)-1 IN DECIMAL

*

* END LOOK UP TABLES

*****************************************************************************************

* BEGIN MAIN PROGRAM

*

ORG $0100

LDA #$F7 CONFIGURATION DATA FOR PORT C DDR

STA $06 LOAD CONFIGURATION DATA INTO PORT C

BSET 0,$02 INITIALIZE B0 PORT C

MES90L NOP

LDA #$2F DIN WORD FOR 1290 CH4 WITH RESPECT

* TO CH5, MSB FIRST, UNIPOLAR, 16 BITS

STA $50 STORE DIN WORD IN DIN BUFFER

JSR READ90 CALL READ90 SUBROUTINE (DUMMY READ)

JSR READ90 CALL READ90 SUBROUTINE (MSBS IN $61 LSBS IN $62)

LDX $10FF LOAD SEGMENT COUNTER INTO X \ FOR N=20 TO 1

DOAGAIN LDA $1000,X LOAD LSBS OF SEGMENT N \

STA $55 STORE LSBS IN $55 \

DECX DECREMENT X \

LDA $1000,X LOAD MSBS OF SEGMENT N \

STA $54 STORE MSBS IN $54 \ FIND B

JSR SUBTRCT CALL SUBTRCT SUBROUTINE /

BPL SEGMENT IF RESULT IS PLUS GOTO SEGMENT /

JSR ADDB CALL ADDB SUBROUTINE /

DECX DECREMENT X /

JMP DOAGAIN GOTO CODE AT LABEL DOAGAIN / NEXT N

AN43-14

Figure 17. Software Code for 68HC05 Processor-Based RTD Linearization

an43f

Page 15

Application Note 43

*

*

*

*

*

SEGMENT LDA $1030,X LOAD MSBS OF SLOPE \

STA $54 STORE MSBS IN $54 \

INCX INCREMENT X \ M*X

LDA $1030,X LOAD LSBS OF SLOPE /

STA $55 STORE LSBS IN $55 /

JSR TBMULT CALL TBMULT SUBROUTINE /

LDA $1060,X LOAD LSBS OF BASE TEMP \

STA $55 STORE LSBS IN $55 \

DECX DECREMENT X > B ADDED TO M*X

LDA $1060,X LOAD MSBS OF BASE TEMP /

STA $54 STORE MSBS IN $54 /

JSR ADDB CALL ADDB SUBROUTINE

* TEMPERATURE IN DEGREES C * 10 IS IN $61 AND $62

* END MAIN PROGRAM

*****************************************************************************************

*

*

JMP MES90L RUN MAIN PROGRAM IN CONTINUOUS LOOP

*

*****************************************************************************************

* SUBROUTINES BEGIN HERE

*

*****************************************************************************************

* READ90 READS THE LTC1290 AND STORES THE RESULT IN $61 AND $62

*

READ90 LDA #$50 CONFIGURATION DATA FOR SPCR \

STA $0A LOAD CONFIGURATION DATA > CONFIGURE PROCESSOR

LDA $50 LOAD DIN WORD INTO THE ACC /

BCLR 0,$02 BIT 0 PORT C GOES LOW (CS GOES LOW) \

STA $0C LOAD DIN INTO SPI DATA REG. START TRANSFER. |

BACK90 TST $0B TEST STATUS OF SPIF |

BPL BACK90 LOOP TO PREVIOUS INSTRUCTION IF NOT DONE |

LDA $0C LOAD CONTENTS OF SPI DATA REG. INTO ACC |

STA $0C START NEXT CYCLE |

STA $61 STORE MSBS IN $61 | XFER

BACK92 TST $0B TEST STATUS OF SPIF | DATA

BPL BACK92 LOOP TO PREVIOUS INSTRUCTION IF NOT DONE |

BSET 0,$02 SET BIT 0 PORT C (CS GOES HIGH) |

LDA $0C LOAD CONTENTS OF SPI DATA REG INTO ACC |

STA $62 STORE LSBS IN $62 /

LDA #$04 LOAD COUNTER WITH NUMBER OF SHIFTS \

SHIFT CLC CLEAR CARRY \

ROR $61 ROTATE MSBS RIGHT THROUGH CARRY \ RIGHT

ROR $62 ROTATE LSBS RIGHT THROUGH CARRY / JUSTIFY

DECA DECREMENT COUNTER / DATA

BNE SHIFT IF NOT DONE SHIFTING THEN REPEAT LOOP /

RTS RETURN TO MAIN PROGRAM

*

* END READ90

*****************************************************************************************

Figure 17. Software Code for 68HC05 Processor-Based RTD Linearization (Continued)

an43f

AN43-15

Page 16

Application Note 43

*****************************************************************************************

*

* SUBTRCT SUBTRACTS $54 AND $55 FROM $61 AND $62. RESULTS IN $61 AND $62

*

SUBTRCT LDA $62 LOAD LSBS

SUB $55 SUBTRACT LSBS

STA $62 STORE REMAINDER

LDA $61 LOAD MSBS

SBC $54 SUBTRACT W/CARRY MSBS

STA $61 STORE REMAINDER

RTS RETURN TO MAIN PROGRAM

*

* END SUBTRCT

*****************************************************************************************

*****************************************************************************************

*

*ADDB RESTORES $61 AND $62 TO ORIGINAL VALUES AFTER SUBTRCT HAS BEEN PERFORMED

*

ADDB LDA $62 LOAD LSBS

ADD $55 ADD LSBS

STA $62 STORE SUM

LDA $61 LOAD MSBS

ADC $54 ADD W/CARRY MSBS

STA $61 STORE SUM

RTS RETURN TO MAIN PROGRAM

*

* END ADDB

*****************************************************************************************

*****************************************************************************************

*

*TBMULT MULTIPLIES CONTENTS OF $61 AND $62 BY CONTENTS OF $54 AND $55.

*16 MSBS OF RESULT ARE PLACED IN $61 AND $62

*

TBMULT CLR $68 CLEAR CONTENTS OF $68 \

CLR $69 CLEAR CONTENTS OF $69 \ RESET TEMPORARY

CLR $6A CLEAR CONTENTS OF $6A / RESULT REGISTERS

CLR $6B CLEAR CONTENTS OF $6B /

STX $58 STORE CONTENTS OF X IN $58. TEMPORARY HOLD REG. FOR X

LSL $62 MULTIPLY LSBS BY 2 \

ROL $61 MULTIPLY MSBS BY 2 \

LSL $62 MULTIPLY LSBS BY 2 \

ROL $61 MULTIPLY MSBS BY 2 \ MULTIPLY $61 AND $62 BY 16

LSL $62 MULTIPLY LSBS BY 2 / FOR SCALING PURPOSES

ROL $61 MULTIPLY MSBS BY 2 /

LSL $62 MULTIPLY LSBS BY 2 /

ROL $61 MULTIPLY MSBS BY 2 /

LDA $62 LOAD LSBS OF 1290 INTO ACC

LDX $55 LOAD LSBS OF M INTO X

MUL MULTIPLY CONTENTS OF $55 BY CONTENTS OF $62

STA $6B STORE LSBS IN $6B

STX $6A STORE MSBS IN $6A

LDA $62 LOAD LSBS OF 1290 INTO ACC

LDX $54 LOAD MSBS OF M INTO X

MUL MULTIPLY CONTENTS OF $54 BY CONTENTS OF $62

ADD $6A LSBS OF MULTIPLY ADDED TO $6A

STA $6A STORE BYTE

TXA TRANSFER X TO ACC

AN43-16

Figure 17. Software Code for 68HC05 Processor-Based RTD Linearization (Continued)

an43f

Page 17

Application Note 43

ADC $69 ADD NEXT BYTE

STA $69 STORE BYTE

LDA $61 LOAD MSBS OF 1290 INTO ACC

LDX $55 LOAD LSBS OF M INTO X

MUL MULTIPLY CONTENTS OF $55 BY CONTENTS OF $61

ADD $6A ADD NEXT BYTE

STA $6A STORE BYTE

TXA TRANSFER X TO ACC

ADC $69 ADD NEXT BYTE

STA $69 STORE BYTE

LDA $61 LOAD MSBS OF 1290 INTO ACC

LDX $54 LOAD MSBS OF M INTO X

MUL MULTIPLY CONTENTS OF $54 BY CONTENTS OF $61

ADD $69 ADD NEXT BYTE

STA $69 STORE BYTE

TXA TRANSFER X TO ACC

ADC $68 ADD NEXT BYTE

STA $68 STORE BYTE

LDA $6A LOAD CONTENTS OF $6A INTO ACC

BPL NNN IF NO CARRY FROM $6A GOTO LABEL NNN

LDA $69 LOAD CONTENTS OF $69 INTO ACC

ADD #$01 ADD 1 TO ACC

STA $69 STORE IN $69

LDA $68 LOAD CONTENTS OF $68 INTO ACC

ADC #$00 FLOW THROUGH CARRY

STA $68 STORE IN $68

NNN LDA $68 LOAD CONTENTS OF $68 INTO ACC

STA $61 STORE MSBS IN $61

LDA $69 LOAD CONTENTS OF $69 INTO ACC

STA $62 STORE IN $62

LDX $58 RESTORE X REGISTER FROM $58

RTS RETURN TO MAIN PROGRAM

*

* END TBMULT

*****************************************************************************************

*

* END

*****************************************************************************************

Figure 17. Software Code for 68HC05 Processor-Based RTD Linearization (Continued)

33k

15V

T1

THERMISTOR

LT1034

1.235V

3.2k

6250Ω

1k

0°C TRIM

16.2k*

15V

+

A1

LT1101

A = 10

–

107k*

T1 = YELLOW SPRINGS #44201

* = 1% FILM RESISTOR

+

LT1006

–

15V

A2

51.1k*

0V TO 10V =

0°C TO 100.0°C ±0.25°C

500Ω

100°C

TRIM

100k*

AN43 F18

Figure 18. Linear Output Thermistor Bridge. Thermistor Network Provides Linear Bridge Output

an43f

AN43-17

Page 18

Application Note 43

10k

ZERO

301k*

9V

9V

100k

+

1/2 LT1078

–

350Ω STRAIN GAGE

PRESSURE TRANSDUCER

9V

LT1004

1.2V

+

LT1101

A = 100

–

* = 1% FILM RESISTOR

PRESSURE TRANSDUCER = BLH #DHF-350

100k

(19a)

0.33

+

1/2 LT1078

–

1.2V RATIO

OUTPUT

OUTPUT

0V TO 5V =

0 TO 350PSI

100k*

7.5k*

1000 – GAIN

AN43 F19a

9V

9V

100k

+

1/2 LT1078

–

LT1004

1.2V

+

LT1101

A = 100

–

* = 1% FILM RESISTOR

PRESSURE TRANSDUCER = MOTOROLA MPX2200AP

ZIN = 1800Ω

100k

0.33

+

1/2 LT1078

–

OUTPUT

0V TO 5V =

0 TO 30PSI

100k*

10k*

2k – GAIN

AN43 F19b

(19b)

Figure 19. Power Reduction by Reducing Bridge Drive. Circuit is a Low Power Version of Figure 5

AN43-18

an43f

Page 19

Application Note 43

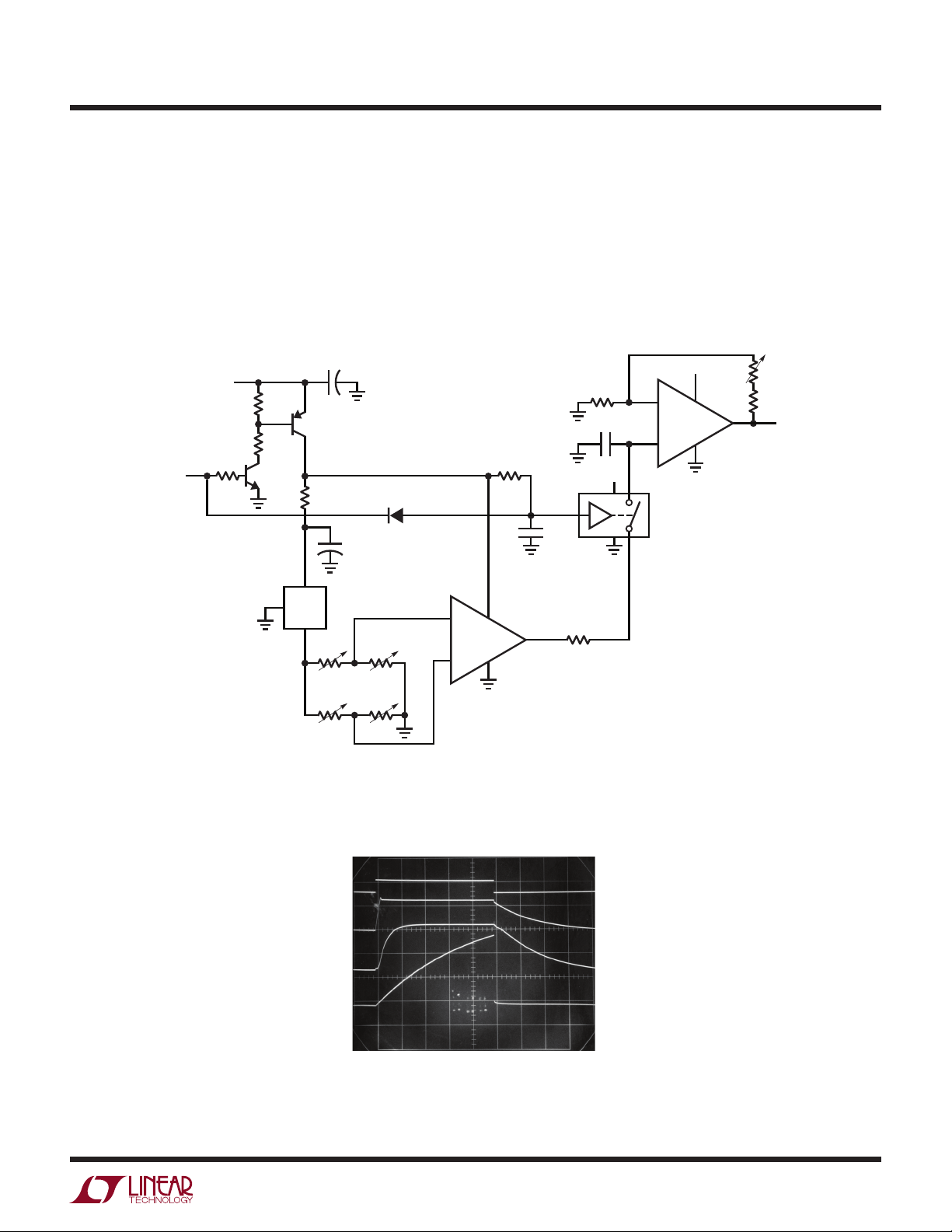

Strobed Power Bridge Drive

Figure 20, derived directly from Figure 10, is a simple way

to reduce power without sacrificing bridge signal output

level. The technique is applicable where continuous output is not a requirement. This circuit is designed to sit in

the quiescent state for long periods with relatively brief

on-times. A typical application would be remote weight

information in storage tanks where weekly readings are

sufficient. Quiescent current is about 150μA with on-state

current typically 50mA. Bridge power is conserved by

simply turning it off.

With Q1’s base unbiased, all circuitry is off except the

LT1054 plus-to-minus voltage converter, which draws a

150μA quiescent current. When Q1’s base is pulled low,

its collector supplies power to A1 and A2. A1’s output

goes high, turning on the LT1054. the LT1054’s output

(Pin 5) heads toward –5V and Q2 comes on, permitting

bridge current to flow. To balance its inputs, A1 servo

controls the LT1054 to force the bridge’s midpoint to 0V.

The bridge ends up with about 8V across it, requiring the

100mA capability LT1054 to sink about 24mA. The 0.02μF

capacitor stabilizes the loop. The A1-LT1054 loop’s negative

output sets the bridge’s common mode voltage to zero,

allowing A2 to take a simple single-ended measurement.

The “output trim” scales the circuit for 3mV/V type strain

bridge transducers, and the 100k-0.1μF combination

provides noise filtering.

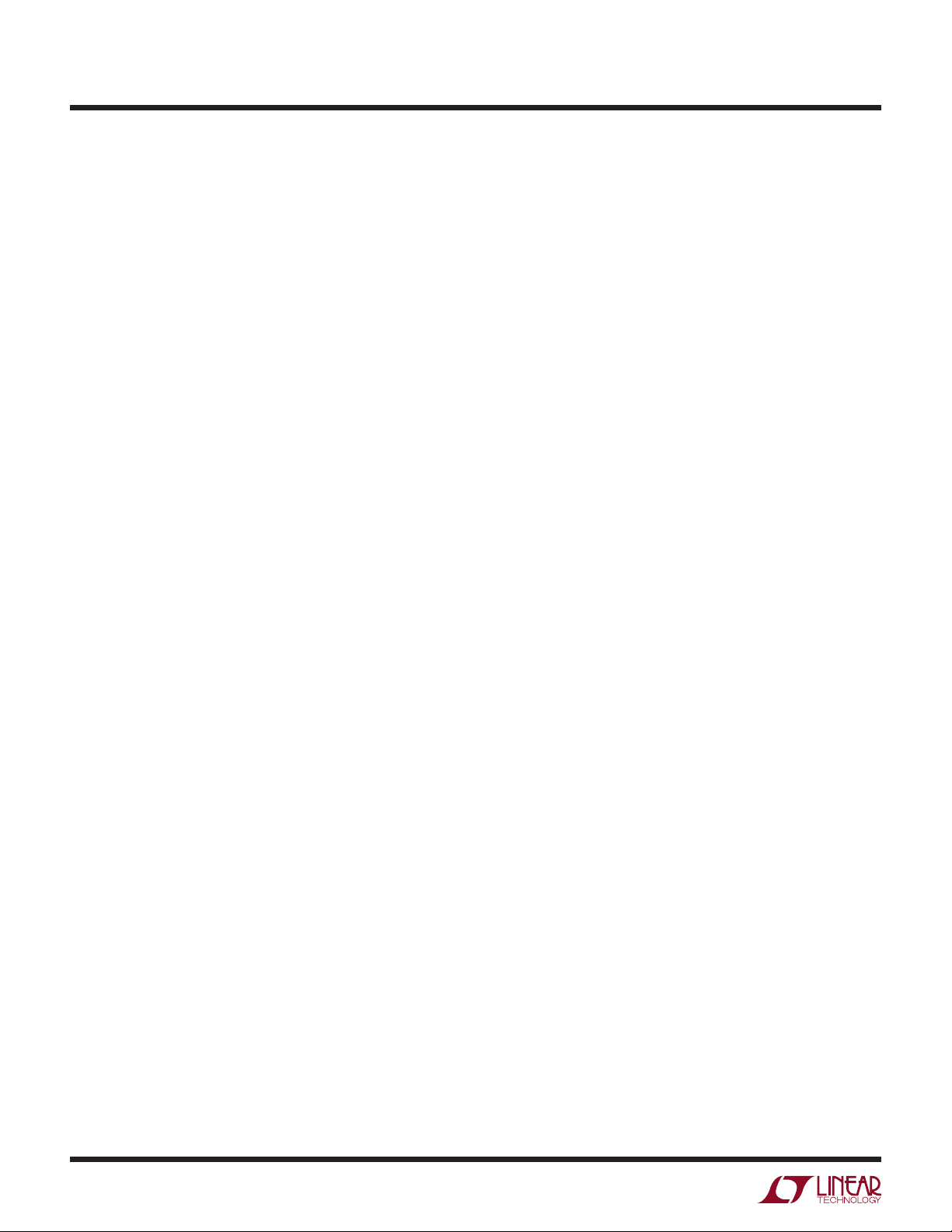

Sampled Output Bridge Signal Conditioner

Figure 21, an obvious extension of Figure 20, automates

the strobing into a clocked sequence. Circuit on-time is

restricted to 250μs, at a clock rate of about 2Hz. This

keeps average power consumption down to about 200μA.

Oscillator A1A produces a 250μs clock pulse every 500ms

(Trace A, Figure 22). A filtered version of this pulse is

fed to Q1, whose emitter (Trace B) provides slew limited

bridge drive. A1A’s output also triggers a delayed pulse

produced by the 74C221 one-shot output (Trace C). The

timing is arranged so the pulse occurs well after the A1BA2 bridge amplifier output (Trace D) settles. A monitoring

A/D converter, triggered by this pulse, can acquire A1B’s

output.

The slew limited bridge drive prevents the strain gauge

bridge from seeing a fast rise pulse, which could cause

long term transducer degradation. To calibrate this circuit

trim zero and gain for appropriate outputs.

10μF

+

SAMPLE

COMMAND

2

CAP

3

GND

4

CAP

* = 1% FILM RESISTOR

FB/SD

+

LT1054

–

V

10k

200k

1

OUT

10k

+

V

5V

+V

1/2 LT1078

0.02

5V

8

+

5

Q1

2N2907

A1

100μF

SOLID

TANTALUM

5V

40Ω

10μF

+

350Ω

3k

STRAIN

GAUGE

BRIDGE

3mV/V

TYPE

Q2

2N2222

100μF

+

100k

+

100k

–

50k

OUTPUT

TRIM

100k

49.9k*

0.1μF

Figure 20. Strobed Power Strain Gauge Bridge Signal Conditioner

10M*

–

A2

1/2 LT1078

+

OUTPUT

PULSE

0V TO 3V

AN43 F20

an43f

AN43-19

Page 20

Application Note 43

0.068

9V

9V

15k

2

3

100k

9V

–

A1A

1/2 LT1078

+

15k

3k

4

11

1N4148 22M

1

100k

100k

15 13

0.068

14

7

0.068

6

CONVERT COMMAND

74C221

TO A/D

4.7k 330Ω

1

5

0.01

10k

9

350Ω

STRAIN

GAGE

BRIDGE

301k*

9V

47μF

Q1

2N2219

+

–

* = 1% FILM RESISTOR

TO A/D RATIO

REFERENCE

A2

LT1101

A = 100

+

A1B

1/2 LT1078

–

Figure 21. Sampled Output Bridge Signal Conditioner Uses Pulsed Excitation to Save Power

TO A/D

2k*

200Ω

GAIN TRIM

750Ω*

AN43 F21

A = 10V/DIV

B = 5V/DIV

C = 10V/DIV

D = 2V/DIV

HORIZ = 50μs/DIV

AN43 F22

Figure 22. Figure 21’s Waveforms. Trace C’s Delayed Pulse Ensures

A/D Converter Sees Settled Output Waveform (Trace D)

AN43-20

an43f

Page 21

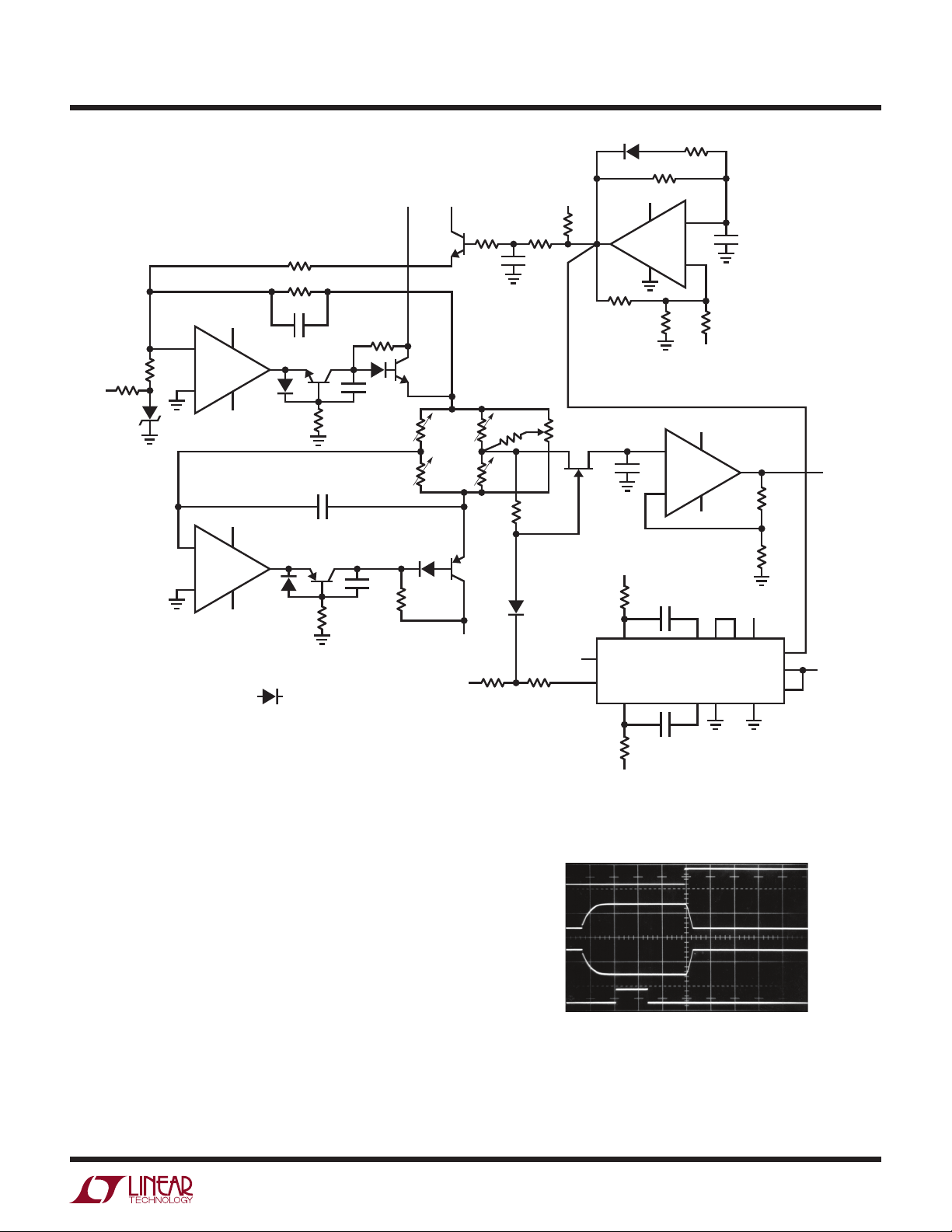

Continuous Output Sampled Bridge Signal Conditioner

Application Note 43

Figure 23 extends the sampling approach to include a

continuous output. This is accomplished by adding a

sample-hold stage at the circuit output. In this circuit, Q2

is off when the “sample command” is low. Under these

conditions only A2 and S1 receive power, and current drain

is inside 60μA. When the sample command is pulsed high,

Q2’s collector (Trace A, Figure 24) goes high, providing

47μF

SOLID TANTALUM

10k

10k

Q1

2N3904

LT1021

3mV/V

TYPE

+

Q2

2N3906

10Ω

+

IN

5V

OUT

350Ω STRAIN

GAUGE BRIDGE

1μF

1N4148

+

LT1101

A = 100

–

A1

10Hz

SAMPLE

COMMAND

6.5V TO 10V

V

10k

+

power to all other circuit elements. The 10Ω-1μF RC at the

LT1021 prevents the strain bridge from seeing a fast rise

pulse, which could cause long term transducer degradation. The LT1021-5 reference output (Trace B) drives the

strain bridge, and instrumentation amplifier A1 output

responds (Trace C). Simultaneously, S1’s switch control

input (Trace D) ramps toward Q2’s collector.

1M

OUTPUT

TRIM

1M

0V TO 5V

OUTPUT

200k

0.003

200Ω

1M

C1 1μF**

+V

6.5V TO 10V = +V

–

A2

LT1077

+

S1

1/4 CD4016

* = 1% METAL FILM RESISTOR

** = POLYSTYRENE

AN43 F23

Figure 23. Pulsed Excitation Bridge Signal Conditioner. Sample-Hold Stage Gives DC Output

A = 20V/DIV

B = 4V/DIV

C = 0.5V/DIV

D = 2V/DIV

HORIZ = 200μs/DIV

AN43 F24

Figure 24. Waveforms for Figure 23’s Sampled Strain Gauge

Signal Conditioner

an43f

AN43-21

Page 22

Application Note 43

At about one-half Q2’s collector voltage (in this case just

before mid-screen) S1 turns on, and A1’s output is stored

in C1. When the sample command drops low, Q2’s collector falls, the bridge and its associated circuitry shut down

and S1 goes off. C1’s stored value appears at gain scaled

A2’s output. The RC delay at S1’s control input ensures

glitch-free operation by preventing C1 from updating

until A1 has settled. During the 1ms sampling phase,

supply current approaches 20mA but a 10Hz sampling

rate cuts effective drain below 250μA. Slower sampling

rates will further reduce drain, but C1’s droop rate (about

1mV/100ms) sets an accuracy constraint. The 10Hz rate

provides adequate bandwidth for most transducers. For

3mV/V slope factor transducers the gain trim shown allows calibration. It should be rescaled for other types. This

circuit’s effective current drain is about 250μA, and A2’s

output is accurate enough for 12-bit systems.

It is important to remember that this circuit is a sampled

system. Although the output is continuous, information

is being collected at a 10Hz rate. As such, the Nyquist

limit applies, and must be kept in mind when interpreting

results.

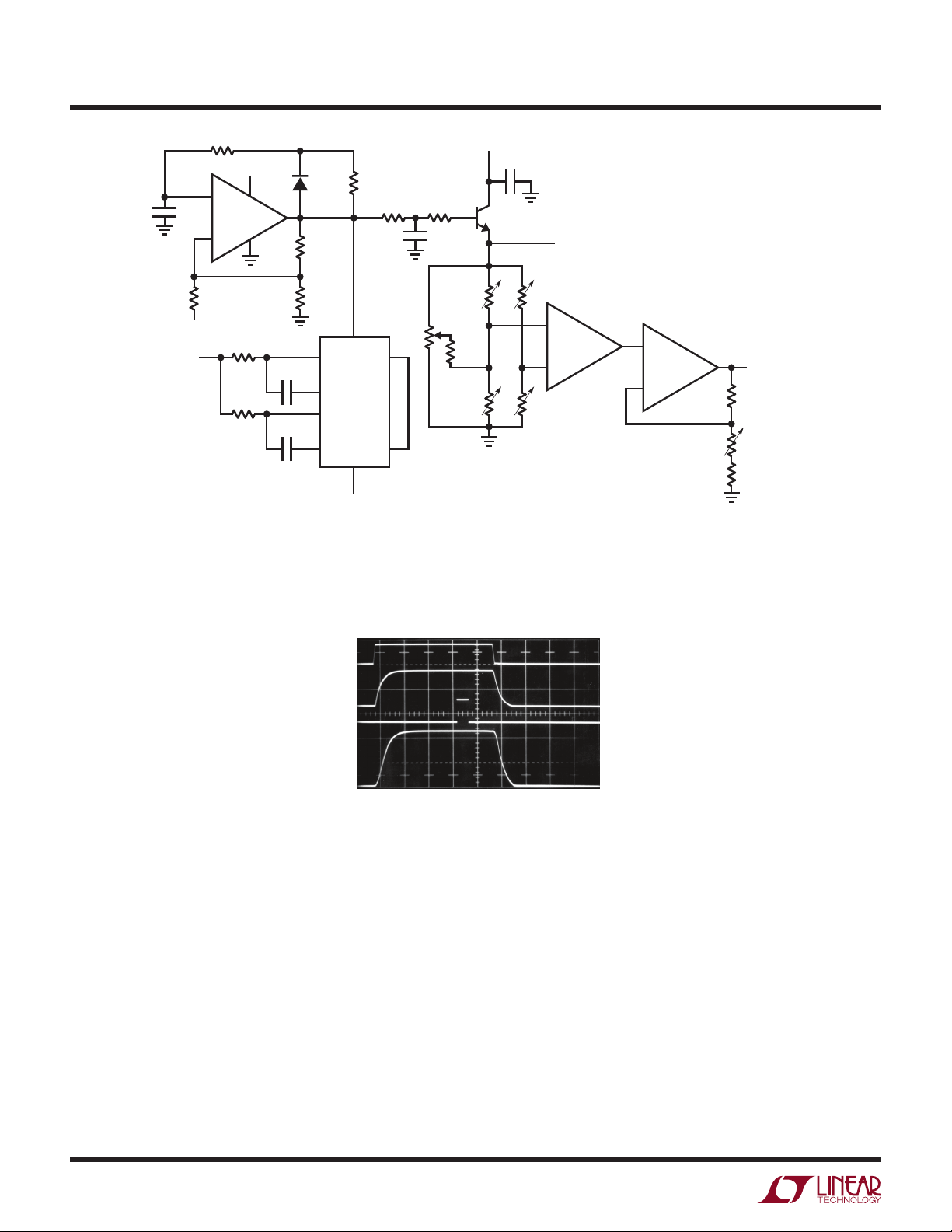

High Resolution Continuous Output Sampled Bridge

Signal Conditioner

Figure 25 is a special case of sampled bridge drive. It is

intended for applications requiring extremely high resolution outputs from a bridge transducer. This circuit puts

100V across a 10V, 350Ω strain gauge bridge for short

periods of time. The high pulsed voltage drive increases

bridge output proportionally, without forcing excessive

dissipation. In fact, although this circuit is not intended

for power reduction, average bridge power is far below

the normal 29mA obtained with 10V

Combining the 10× higher bridge gain (300mV full scale

versus the normal 30mV) with a chopper-stabilized amplifier in the sample-hold output stage is the key to the high

resolution obtainable with this circuit.

When oscillator A1A’s output is high Q6 is turned on and

A2’s negative input is pulled above ground. A2’s output

goes negative, turning on Q1. Q1’s collector goes low,

excitation.

DC

robbing Q3’s base drive and cutting it off. Simultaneously, A3 enforces it’s loop by biasing Q2 into conduction,

softly turning on Q4. Under these conditions the voltage

across the bridge is essentially zero. When A1A oscillates

low (Trace A, Figure 26) RC filter driven Q6 responds by

cutting off slowly. Now, A2’s negative input sees current

only through the 3.6k resistor. The input begins to head

negative, causing A2’s output to rise. Q1 comes out of

saturation, and Q3’s emitter (Trace B) rises. Initially this

action is rapid (fast rise slewing is just visible at the start

of Q3’s ascent), but feedback to A2’s negative input closes

a control loop, with the 1000pF capacitor restricting rise

time. The 72k resistor sets A2’s gain at 20 with respect

to the LT1004 2.5V reference, and Q3’s emitter servo

controls to 50V.

Simultaneously, A3 responds to the bridges biasing by

moving its output negatively. Q2 tends towards cut-off,

increasing Q4’s conduction. A3 biases its loop to maintain

the bridge midpoint at zero. To do this, it must produce a

complimentary output to A2’s loop, which Trace C shows

to be the case. Note that A3’s loop roll-off is considerably

faster than A2’s, ensuring that it will faithfully track A2’s

loop action. Similarly, A3’s loop is slaved to A2’s loop

output, and produces no other outputs.

Under these conditions the bridge sees 100V drive across

it for the 1ms duration of the clock pulse.

A1A’s clock output also triggers the 74C221 one-shot.

The one-shot delivers a delayed pulse (Trace D) to Q5. Q5

comes on, charging the 1μF capacitor to the bridges output

voltage. With A3 forcing the bridges left side midpoint to

zero, Q5, the 1μF capacitor and A4 see a single-ended, low

voltage signal. High transient common mode voltages are

avoided by the control loops complimentary controlled rise

times. A4 takes gain and provides the circuit output. The

74C221’s pulse width ends during the bridge’s on-time,

preserving sampled data integrity. When the A1A oscillator

goes high the control loops remove bridge drive, returning

the circuit to quiescence. A4’s output is maintained at DC

by the 1μF capacitor. A1A’s 1Hz clock rate is adequate to

prevent deleterious droop of the 1μF capacitor, but slow

enough to limit bridge power dissipation. The controlled

AN43-22

an43f

Page 23

Application Note 43

4.7k

2.7M

–15V

2.7k

LT1004

2.5V

3.6k

–

LT1012

+

–

LT1007

+

15V

A2

–15V

15V

A3

–15V

* = 1% FILM RESISTOR

2k

72k

1000pF

MPSA42

MPSA92

= 1N4148

Q1

100pF

Q2

4.7k

4.7k

55V 15V 15V

4.7k

Q6

2N3904

10k

Q3

MJE344

68pF

350Ω

BRIDGE

Q4

–15V

MJE350

–55V

12k 10k

68pF

10k

1M

0.002

10M

4.7k

50k

ZERO

15V

1k

Q5

2N4391

C2

Q2

2.7M

15V

R1

R2

15V

A1A

1/2 LT1018

1μF

10k

0.05

–

+

2.7M

+

A4

LTC1150

–

74C221

15V

15V

–15V

C1

C2

2.7M

Q1 B1

A2

0.33

15V

33k*

100Ω*

A1

B1

C1

OUTPUT

15V

AN43 F25

0.05

3k

15V

Figure 25. High Resolution Pulsed Excitation Bridge Signal Conditioner. Complementary 50V Drive Increases Bridge Output Signal

rise and fall times across the bridge prevent possible

A = 20V/DIV

long-term transducer degradation by eliminating high

ΔV/ΔT induced effects.

B = 50V/DIV

When using this circuit it is important to remember that it

is a sampled system. Although the output is continuous,

information is being collected at a 1Hz rate. As such, the

Nyquist limit applies, and must be kept in mind when

C = 50V/DIV

D = 20V/DIV

HORIZ = 200μs/DIV

AN43 F26

interpreting results.

Figure 26. Figure 25’s Waveforms. Drive Shaping Results in

Controlled, Complementary Bridge Drive Waveforms. Bridge

Power is Low Despite 100V Excitation

an43f

AN43-23

Page 24

Application Note 43

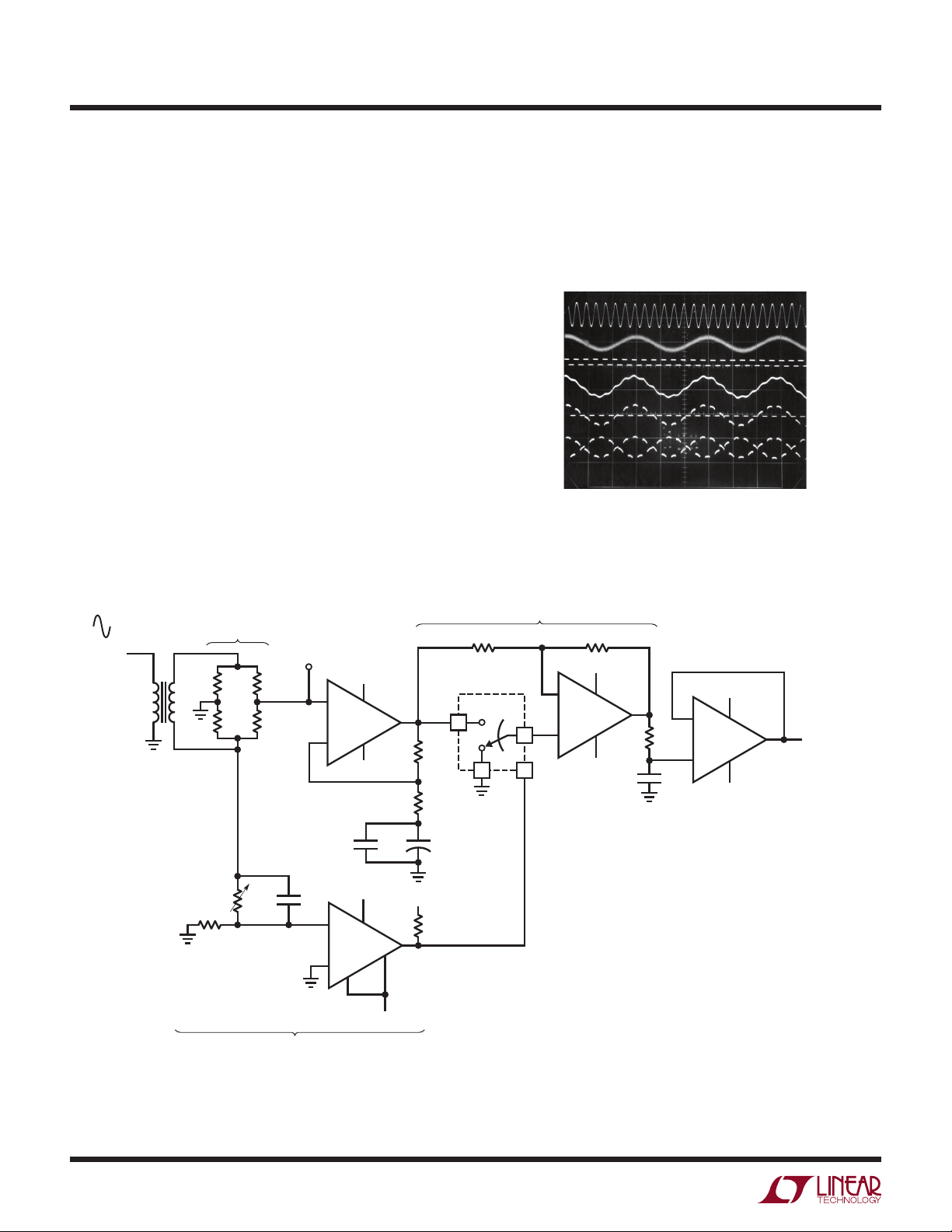

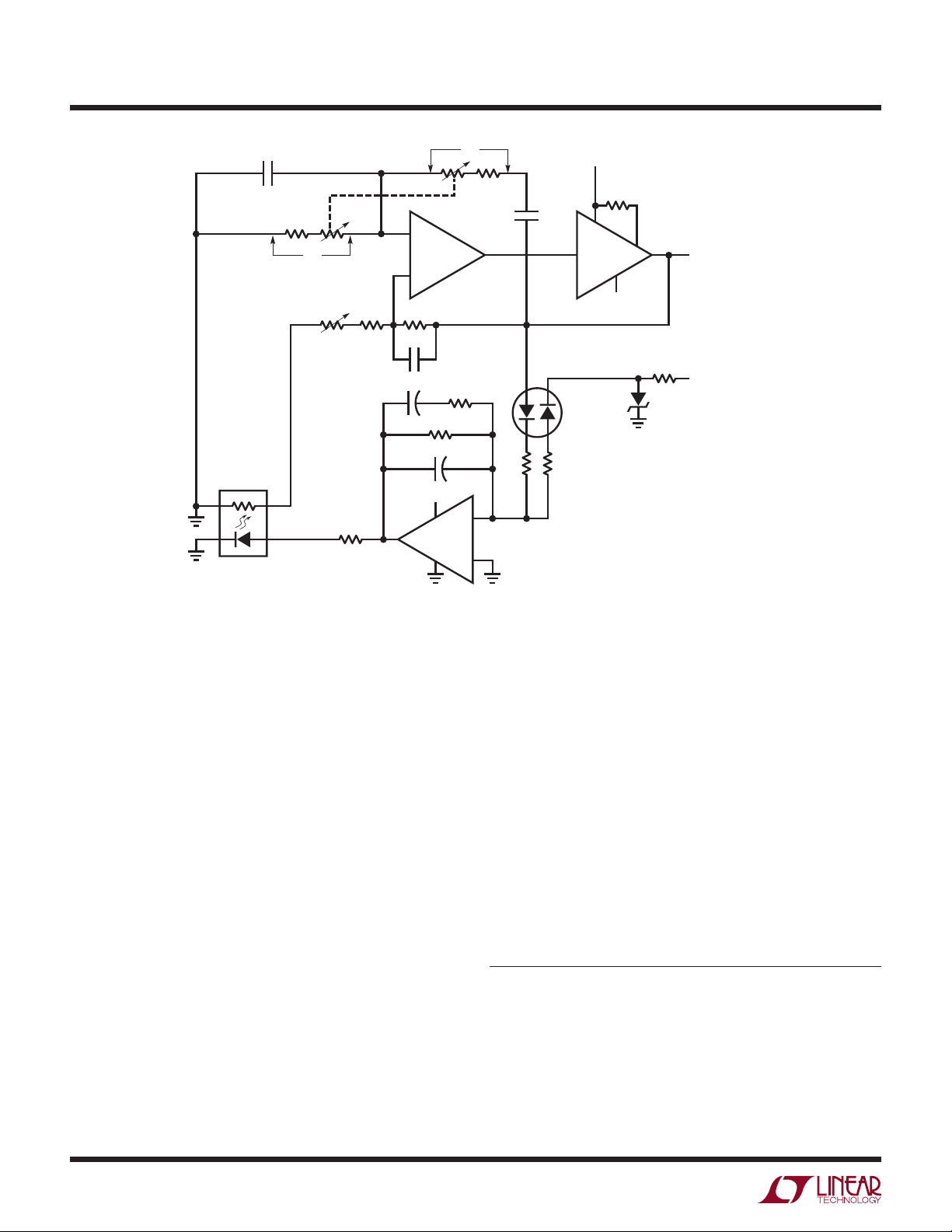

AC Driven Bridge/Synchronous Demodulator

Figure 27, an extension of pulse excited bridges, uses

synchronous demodulation to obtain very high noise

rejection capability. An AC carrier excites the bridge and

synchronizes the gain stage demodulator. In this application, the signal source is a thermistor bridge which

detects extremely small temperature shifts in a biochemical

microcalorimetry reaction chamber.

The 500Hz carrier is applied at T1’s input (Trace A, Figure 28). T1’s floating output drives the thermistor bridge,

which presents a single-ended output to A1. A1 operates

at an AC gain of 1000. A 60Hz broadband noise source

is also deliberately injected into A1’s input (Trace B). The

carrier’s zero crossings are detected by C1. C1’s output

clocks the LTC1043 (Trace C). A1’s output (Trace D) shows

the desired 500Hz signal buried within the 60Hz noise

source. The LTC1043’s zero-cross-synchronized switching

at A2’s positive input (Trace E) causes A2’s gain to alternate

between plus and minus one. As a result, A1’s output is

synchronously demodulated by A2. A2’s output (Trace F)

consists of demodulated carrier signal and non-coherent

components. The desired carrier amplitude and polarity

information is discernible in A2’s output and is extracted

by filter-averaging at A3. To trim this circuit, adjust the

phase potentiometer so that C1 switches when the carrier

crosses through zero.

A = 2V/DIV

B = 2V/DIV

C = 50V/DIV

D = 5V/DIV

E = 5V/DIV

F = 5V/DIV

HORIZ = 5ms/DIV

Figure 28. Details of Lock-In Amplifier Operation. Narrowband

Synchronous Detection Permits Extraction of Coherent Signals

Over 120dB Down

AN43 F28

500Hz

SINE DRIVE

THERMISTOR BRIDGE

IS THE SIGNAL SOURCE

T1

1

4

3

2

6.19k

6.19k

6.19kR

T

PHASE TRIM

50k

10k

C1

0.002

ZERO CROSSING DETECTOR

TEST

POINT

A

SYNCHRONOUS

DEMODULATOR

–

2

1/2 LT1057

3

+

10k*

5V

A2

1M

–5V

T1 = TF5SX17ZZ, TOROTEL

= YSI THERMISTOR 44006

R

T

≈ 6.19k AT 37.5°C

* = MATCH 0.05%

6.19k = VISHAY S-102

OPERATE LTC1043 WITH

±5V SUPPLIES

1μF

–

2

1/2 LT1057

3

+

5V

A3

–5V

t%$

V

OUT

BRIDGE SIGNAL

10k*

5V

3

+

A1

LT1007

2

–

6

–5V

+

5V

2

+

LT1011

3

–

1

5V

8

7

4

–5V

1/4 LTC1043

13

12

100k

14 16

100Ω

47μF0.01

1k

AN43 F27

AN43-24

Figure 27. “Lock-In” Bridge Amplifier. Synchronous Detection Achieves Extremely Narrow Band Gain,

Providing Very High Noise Rejection

an43f

Page 25

AC Driven Bridge for Level Transduction

Application Note 43

Level transducers which measure angle from ideal level

are employed in road construction, machine tools, inertial

navigation systems and other applications requiring a

gravity reference. One of the most elegantly simple level

transducers is a small tube nearly filled with a partially

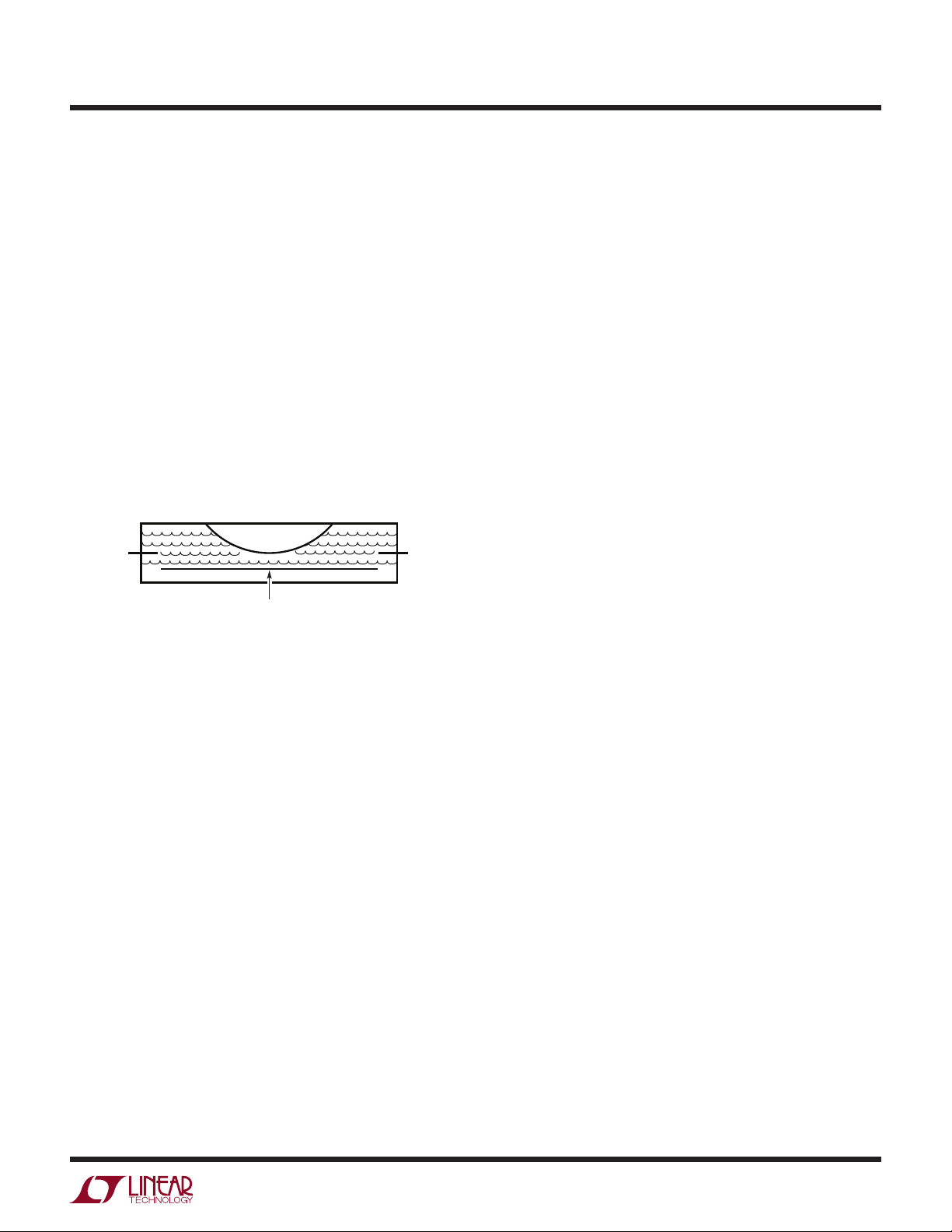

conductive liquid. Figure 29a shows such a device. If the

tube is level with respect to gravity, the bubble resides in

the tube’s center and the electrode resistances to common are identical. As the tube shifts away from level,

the resistances increase and decrease proportionally. By

controlling the tube’s shape at manufacture it is possible

to obtain a linear output signal when the transducer is

incorporated in a bridge circuit.

PARTIALLY

CONDUCTIVE

LIQUID IN

SEALED

GLASS TUBE

BUBBLE

ELECTRODEELECTRODE

AN43 F29a

COMMON ELECTRODE

Figure 29a. Bubble-Based Level Transducer

Transducers of this type must be excited with an AC waveform to avoid damage to the partially conductive liquid

inside the tube. Signal conditioning involves generating

this excitation as well as extracting angle information and

polarity determination (e.g., which side of level the tube is

on). Figure 29b shows a circuit which does this, directly

producing a calibrated frequency output corresponding to

level. A sign bit, also supplied at the output, gives polarity

information.

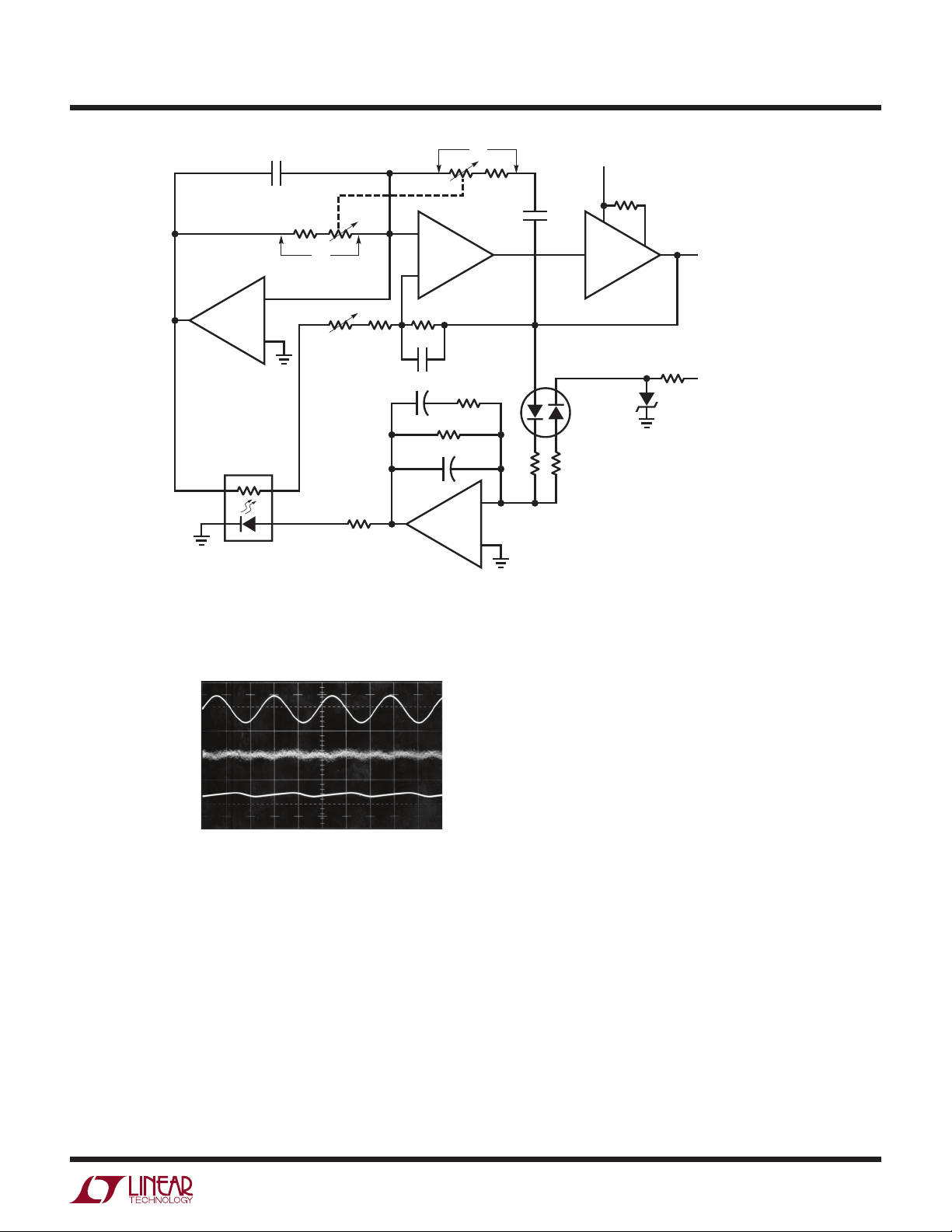

The level transducer is configured with a pair of 2kΩ resistors to form a bridge. The required AC bridge excitation is

developed at C1A, which is configured as a multivibrator.

C1A biases Q1, which switches the LT1009’s 2.5V potential

through the 100μF capacitor to provide the AC bridge drive.

The bridge differential output AC signal is converted to a

current by A1, operating as a Howland current pump. This

current, whose polarity reverses as bridge drive polarity

switches, is rectified by the diode bridge. Thus, the 0.03μF

capacitor receives unipolar charge. Instrumentation amplifier A2 measures the voltage across the capacitor and

presents its single-ended output to C1B. When the voltage

across the 0.03μF capacitor becomes high enough, C1B’s

output goes high, turning on the LTC201A switch. This

discharges the capacitor. When C1B’s AC positive feedback

ceases, C1B’s output goes low and the switch goes off. The

0.03μF unit again receives constant current charging and

the entire cycle repeats. The frequency of this oscillation

is determined by the magnitude of the constant current

delivered to the bridge-capacitor configuration. This current’s magnitude is set by the transducer bridge’s offset,

which is level related.

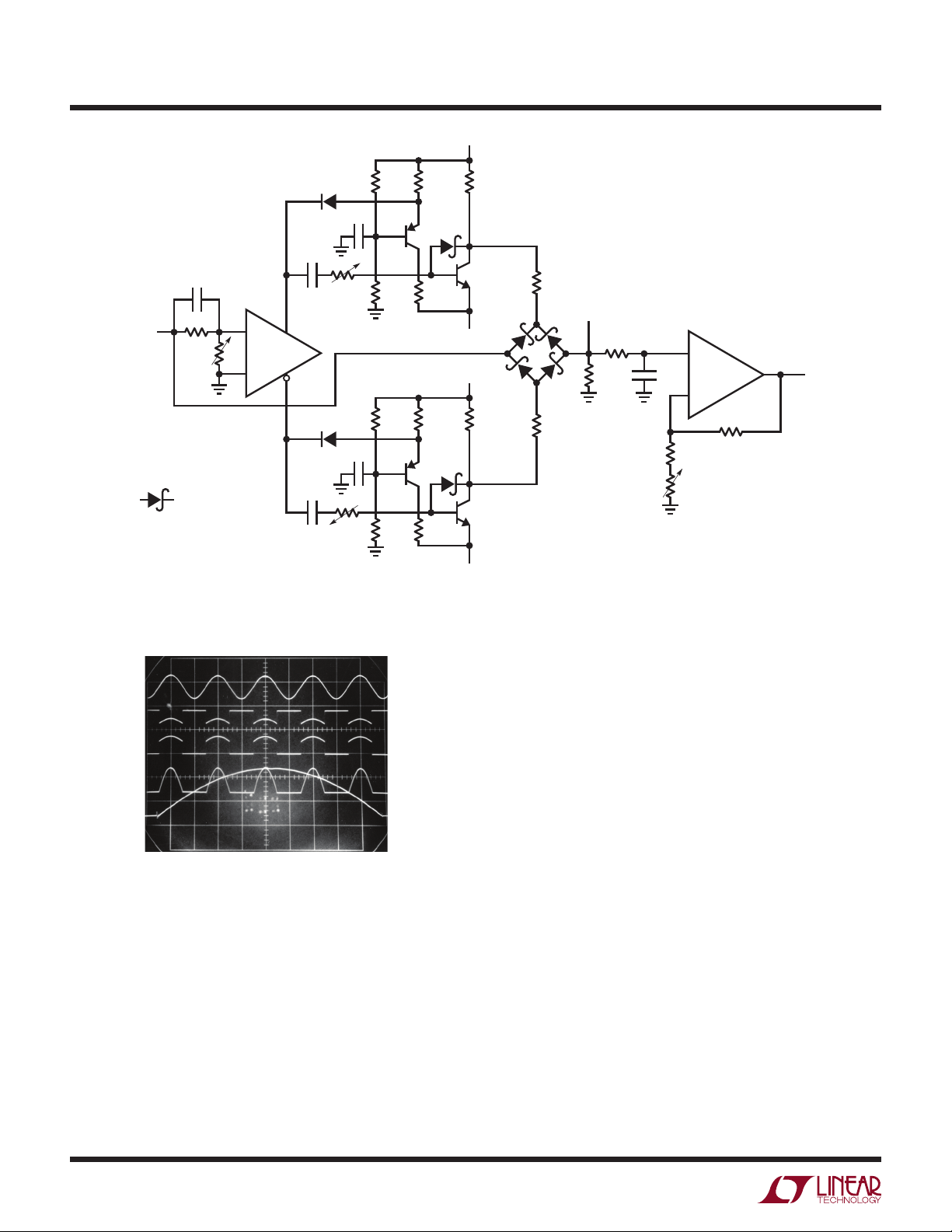

Figure 30 shows circuit waveforms. Trace A is the AC

bridge drive, while Trace B is A1’s output. Observe that

when the bridge drive changes polarity, A1’s output flips

sign rapidly to maintain a constant current into the bridgecapacitor configuration. A2’s output (Trace C) is a unipolar,

ground-referred ramp. Trace D is C1B’s output pulse and

the circuit’s output. The diodes at C1B’s positive input

provide temperature compensation for the sensor’s positive tempco, allowing C1B’s trip voltage to ratiometrically

track bridge output over temperature.

A3, operating open loop, determines polarity by comparing the rectified and filtered bridge output signals with

respect to ground.

To calibrate this circuit, place the level transducer at a

known 40 arc-minute angle and adjust the 5kΩ trimmer

at C1B for a 400Hz output. Circuit accuracy is limited by

the transducer to about 2.5%.

an43f

AN43-25

Page 26

Application Note 43

5V

–

1/2 LT1057

+

1N4148

w4

1/4

LTC201A

5V

C1A

1/2 LT1018

–5V

A1

–

+

–

+

10k*

10k*

A2

LT1102

A = 10

0.01μF

220pF

CALIBRATE

330Ω

1N4148

0.1

10M

0.1

1N4148

3.01k

5k

5V

1N4148

LT1009

2.5V

10M

220k

1.3k

–

A3

1/2 LT1057

+

–

C1B

1/2 LT1018

+

47pF

SIGN BIT

+ OR – FOR

EITHER SIDE

OF LEVEL

5V

1k

FREQUENCY OUT

0 TO 40 ARC

MINUTES =

0Hz TO 400Hz

2M

+

10μF

Q1

2N3906

10k

10k

10k

200k

+

100μF

2k*2k*

LEVEL

TRANSDUCER

499k*

499k*

200k

I

K

0.03

Figure 29b. Level Transducer Digitizer Uses AC Bridge Technique

A = 5V/DIV

B = 1V/DIV

C = 2V/DIV

D = 20V/DIV

HORIZ = 20ms/DIV

AN43 F30

Figure 30. Level Transducer Bridge Circuit’s Waveforms

* = 1% RESISTOR

LEVEL TRANSDUCER = FREDERICKS #7630

AN43 F29b

Time Domain Bridge

Figure 31 is another AC-based bridge, but works in the

time domain. This circuit is particularly applicable to

capacitance measurement. Operation is straightforward.

With S1 closed the comparators output is high. When S1

opens, capacitor C

charges. When CX’s potential crosses

X

the voltage established by the bridge’s left side resistors

the comparator trips low. The elapsed time between the

switch opening and the comparator going low is proportionate to C

’s value. This circuit is insensitive to supply and

X

an43f

AN43-26

Page 27

Application Note 43

15V

10k*

10k*

–

LT1011

15V

1k

OUTPUT

+

20k*

C

X

LTC201A

INPUT

AN43 F31

* = 1% FILM RESISTOR

Figure 31. Time Domain Bridge

repetition rate variations and can provide good accuracy if

time constants are kept much larger than comparator and

switch delays. For example, the LT1011’s delay is about

200ns and the LTC201A contributes 450ns. To ensure 1%

accuracy the bridges right side time constant should not

drop below 65μs. Extremely low values of capacitance

may be influenced by switch charge injection. In such

cases switching should be implemented by alternating

the bridge drive between ground and +15.

Bridge Oscillator—Square Wave Output

Only an inattentive outlook could resist folding Figure 31’s

bridge back upon itself to make an oscillator. Figure 32

does this, forming a bridge oscillator. This circuit will also

be recognized as the classic op amp multivibrator. In this

version the 10k to 20k bridge leg provides switching point

hysteresis with C

When C

reaches the switching point the amplifier’s output

X

charged via the remaining 10k resistor.

X

changes state, abruptly reversing the sign of its positive

input voltage. C

’s charging direction also reverses, and

X

oscillations continue. At frequencies that are low compared

to amplifier delays output frequency is almost entirely

dependent on the bridge components. Amplifier input

errors tend to ratiometrically cancel, and supply shifts are

similarly rejected. The duty cycle is influenced by output

saturation and supply asymmetrys.

Quartz Stabilized Bridge Oscillator

Figure 33, generically similar to Figure 32, replaces one

of the bridge arms with a resonant element. With the

crystal removed the circuit is a familiar noninverting gain

of 2 with a grounded input. Inserting the crystal closes a

positive feedback path at the crystal’s resonant frequency.

The amplifier output (Trace A, Figure 34) swings in an

attempt to maintain input balance. Excessive circuit gain

prevents linear operation, and oscillations commence as

the amplifier repeatedly overshoots in its attempts to null

the bridge. The crystal’s high Q is evident in the filtered

waveform (Trace B) at the amplifiers positive input.

CRYSTAL

20kHz

NT CUT

100k

Figure 33. Bridge-Based Crystal Oscillator

A = 10V/DIV

100Ω

100Ω

–

LT1056

+

AN43 F33

10k*

10k*

15V

–

LT1056

C

X

+

20k*

–15V

* = 1% FILM RESISTOR

AN43 F32

Figure 32. “Bridge Oscillator” (Good Old Op Amp

Multivibrator with a Fancy Name)

B = 5V/DIV

HORIZ = 20μs/DIV

AN43 F34

Figure 34. Bridge-Based Crystal Oscillator’s Waveforms.

Excessive Gain Causes Output Saturation Limiting

AN43-27

an43f

Page 28

Application Note 43

Sine Wave Output Quartz Stabilized Bridge Oscillator

Figure 35 takes the previous circuit into the linear region to

produce a sine wave output. It does this by continuously

controlling the gain to maintain linear operation. This

arrangement uses a classic technique first described by

Meacham in 1938 (see References).

In any oscillator it is necessary to control the gain as well

as the phase shift at the frequency of interest. If gain is too

low, oscillation will not occur. Conversely, too much gain

produces saturation limiting, as in Figure 33. Here, gain

control comes from the positive temperature coefficient

of the lamp. When power is applied, the lamp is at a low

resistance value, gain is high and oscillation amplitude

builds. As amplitude builds, the lamp current increases,

heating occurs and its resistance goes up. This causes a

reduction in amplifier gain and the circuit finds a stable

operating point. The 15pF capacitor suppresses spurious

oscillation.

Operating waveforms appear in Figure 36. The amplifiers

output (Trace A, Figure 36) is a sine wave, with about 1.5%

distortion (Trace B). The relatively high distortion content

is almost entirely due to the common mode swing seen

by the amplifier. Op amp common mode rejection suffers

at high frequency, producing output distortion. Figure 37

eliminates the common mode swing by using a second

3

amplifier to force the bridge’s midpoint to virtual ground.

It does this by measuring the midpoint value, comparing

it to ground and controlling the formerly grounded end

of the bridge to maintain its inputs at zero. Because the

bridge drive is complementary the oscillator amplifier

now sees no common mode swing, dramatically reducing

distortion. Figure 38 shows less than 0.005% distortion

(Trace B) in the output (Trace A) waveform.

Note 3: Sharp-eyed readers will recognize this as an AC version of the DC

common mode suppression technique introduced back in Figure 6.

CRYSTAL

20kHz

NT CUT

100Ω

–

AN43 F35

RMS

20kHz

15pF

100k

#327

LAMP

LT1056

+

OSCILLATOR

OUT

1V

Figure 35. Figure 33 with Lamp Added for Gain Stabilization

0.005

COMMON MODE

SUPRESSION

CRYSTAL

20kHz

NT CUT

100Ω

–

OUT

1V

RMS

20kHz

15pF

100k

#327

LAMP

1/2 LT1057

+

OSCILLATOR

AN43 F37

–

1/2 LT1057

+

A = 2V/DIV

B = 0.1V/DIV

(1.5% DISTORTION)

HORIZ = 20μs/DIV

Figure 36. Lamp-Based Amplitude Stabilization

Produces Sine Wave Output

A = 2V/DIV

B = 0.2V/DIV

(0.005% DISTORTION)

HORIZ = 20μs/DIV

AN43 F36

AN43 F38

Figure 37. Common Mode Suppression for Quartz Oscillator

Lowers Distortion

AN43-28

Figure 38. Distortion Measurements for Figure 37.

Common Mode Suppression Permits 0.005% Distortion

an43f

Page 29

Wien Bridge-Based Oscillators

Application Note 43

Crystals are not the only resonant elements that can be

stabilized in a gain-controlled bridge. Figure 39 is a Wien

bridge (see References) based oscillator. The configuration

shown was originally developed for telephony applications.

The circuit is a modern adaptation of one described by a

4

Stanford University student, William R. Hewlett,

in his

1939 masters thesis (see Appendix C, “The Wien Bridge