Page 1

Microsoft® Combat Flight Simulator 3.0

http://www.replacementdocs.com

http://www.replacementdocs.com

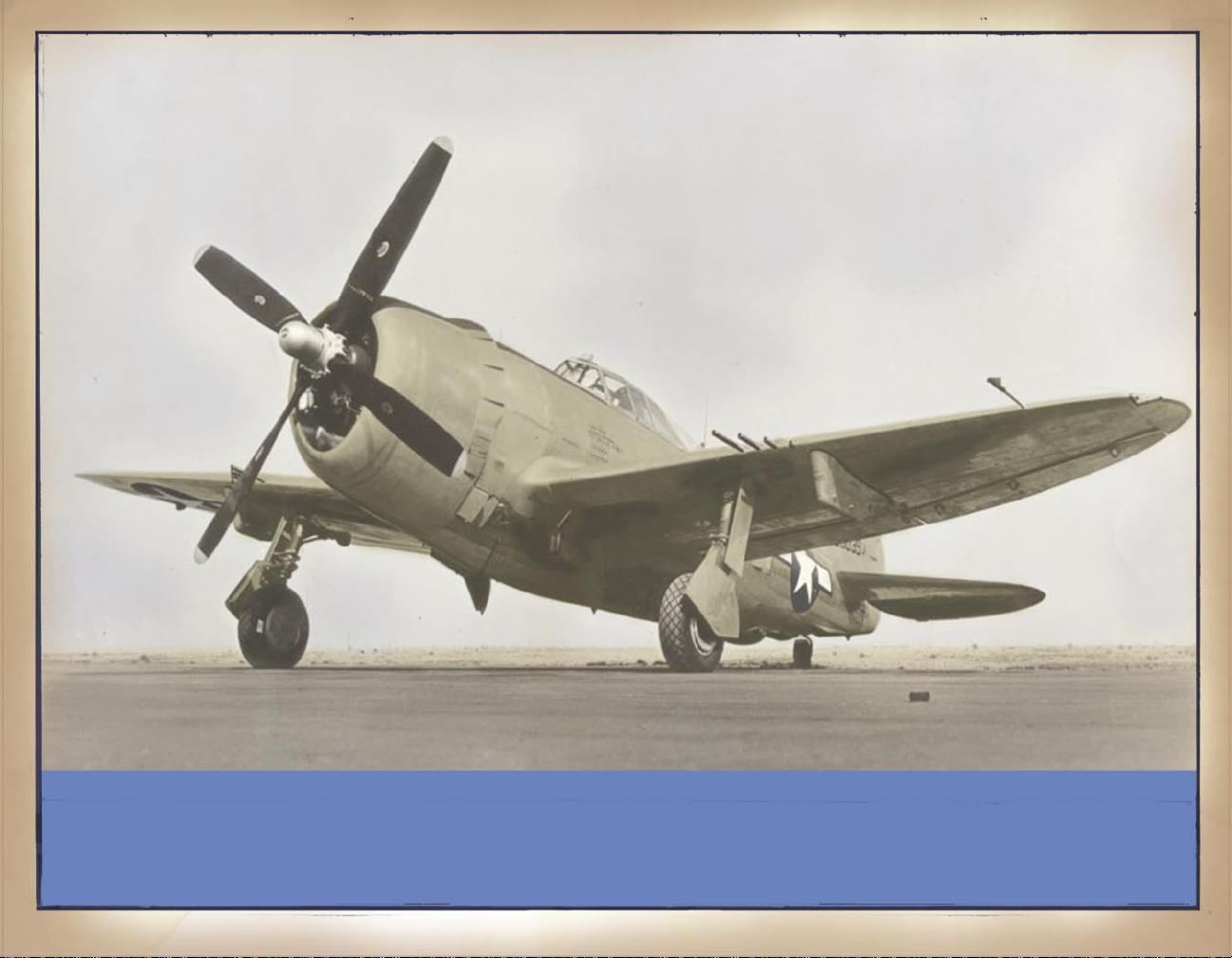

Air Force Historical Research Agency Photo

FLIGHT SCHOOL

handbook

Page 2

FLYING CLASSROOM: A FOR

MATION OF AT-6 “TEXAN”

TRAINERS.

Basic Flight

If you make assumptions about how

an airplane works you put your machine,

your life, and your country at risk.

Practice and study every aspect of

ight and combat, and when you go to

sleep--dream it.

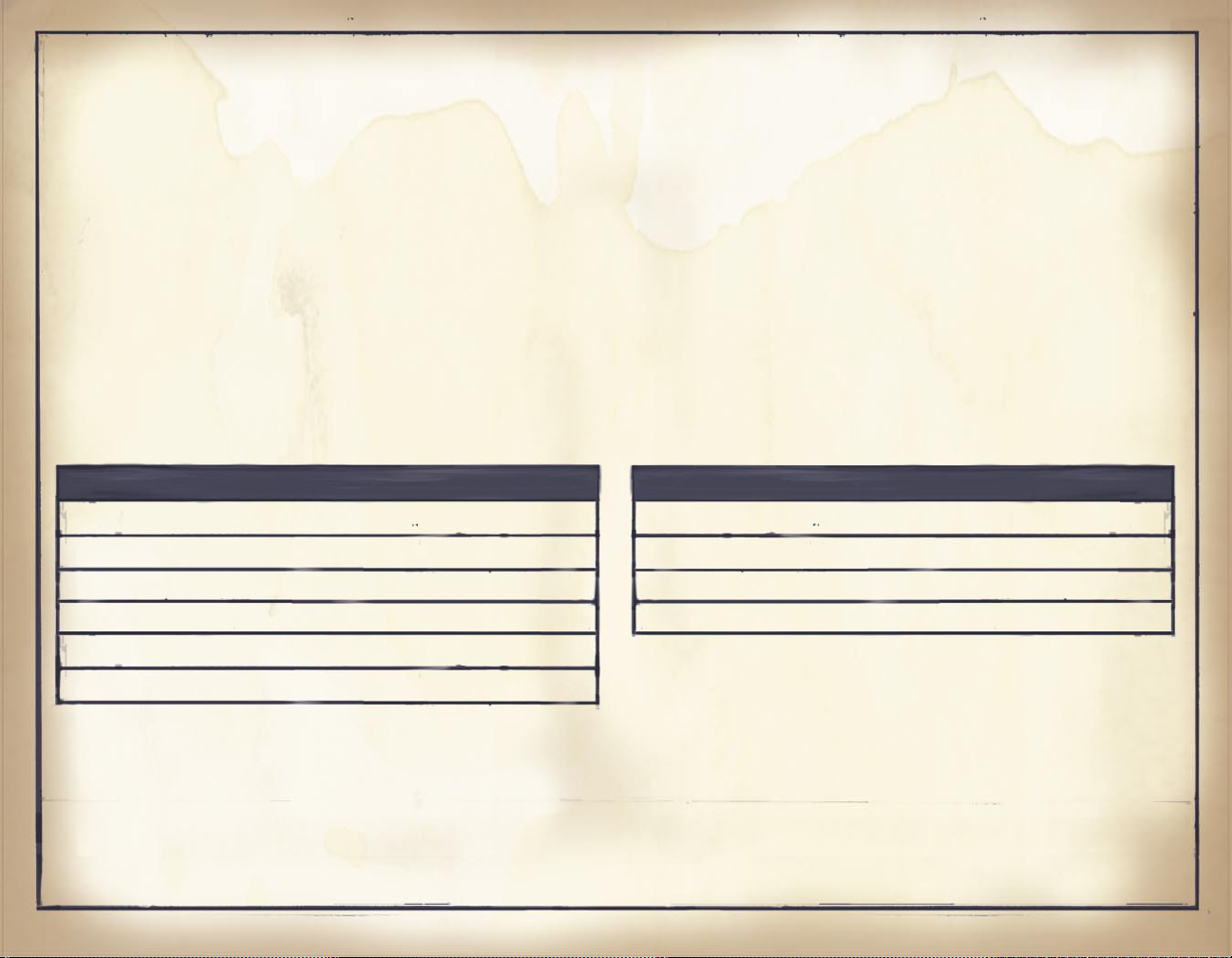

First Things First................ 3

The Instrument Panel.............. 4

Flight Controls................... 5

Engine Controls................... 8

Getting Up and Back.............. 11

Air Force Historical Research Agency Photo

Basic Flight Maneuvers........... 14

Why it All Works................. 18

Basic Aerobatic Maneuvers........ 22

* * *

Air Combat

Dropping a bomb onto a moving

target–-it seems like you’ll never get

it right. Your troops are depending

on you to clear out the hornets nest

impeding their advance. What can you

-

do? Plenty!

Tools of the Trade............... 26

Ground Attack Philosophy......... 31

Basic Air Combat Maneuvers....... 38

Authorized licensees of this game may print (or have printed at their expense) a single

copy of this manual for their personal home use in conjunction with the play and use of

the game on this CD.

- 1 -

Tactical Air Combat Maneuvers.... 43

A Few Tips....................... 49

Telling Friend from Foe.......... 50

Page 3

Air Force Historical Research Agency Photo

BASIC FLIGHT

- 2 -

Page 4

FIRST THINGS FIRST

You’re about to take on a huge responsibility by

participating in the greatest struggle so far in the 20th

century. Are you up to it? Your country and your squadron

mates are counting on you, so we’re going to get you up

to speed.

You’ve been assigned to the tactical air support

role, which means you’ll be ying low where you’re

vulnerable to enemy antiaircraft guns. Give yourself a

ghting chance by rst going through training. Military

ight training consists of these three steps:

1. First, you’ll read this handbook.

2. Then you’ll watch movies that show several basic

combat maneuvers you need to master.

3. Finally, you’ll practice what you’ve learned by

actually ying.

When you’re done training, you’ll know how to handle

a powerful airplane and how to use it to hit the enemy

hard.

The Flight School handbook

Read this handbook and study the diagrams to learn

the basics of ight, how your plane works and ies, and

how to execute combat maneuvers. If you’re a novice,

begin with the basics of ight; if you’re an experienced

yer, jump right into the air combat training section

so we can use you as soon as possible. If you understand

the material in this handbook, you’ll be a better ghter.

Read it now!

The movies

After you’ve read the handbook, watch the training

movies. (You can access them in the CFS3 Training

Materials section of online Help.) These movies

demonstrate two tactical air combat and two dogghting

maneuvers that can be applied in a variety of situations.

The training missions

Finally, get in the plane and practice tactical air

combat maneuvers, such as dive bombing, strang, and

level bombing. You’ll use these skills to aid the ground

soldiers as they advance. Practice the maneuvers until

they’re second nature so you don’t have to think about

them when you’re in combat. Here are some tips for getting

up to speed quickly:

- Study the Quick Reference Card. Memorize key commands

to help you do things quickly when time is of the

essence.

- Familiarize yourself with the instrument panel. Roll

the cursor over each instrument to see both what it

is and its current reading.

- Use the Free Flight option. (Click the Quick Combat

tab, and then click Free Flight.) Use Free Flight

to practice both basic and combat maneuvers without

getting shot at. You need to master these maneuvers

to stay alive and help us WIN!

- Fly some training missions. (Click the Missions tab,

and then select a mission from the Training tab.) By

ying training missions, you can practice what you’ve

learned, but with the heat turned up a notch.

- Practice your level bombing skills. Level bombing

means you must y level over the target, which can

be difcult when you’re being shot at. You’ll need to

switch between three positions: cockpit, gunner, and

bombardier. You can y your plane from the cockpit,

but you can also jump to a gunner position and

defend, or jump to the bombardier position and drop

your load on the target. Dropping a bomb load while

looking through a bombsight is tougher than it might

seem. Practice!

Time is wasting so get busy. We’ve got an important

mission and we need you!

- 3 -

Page 5

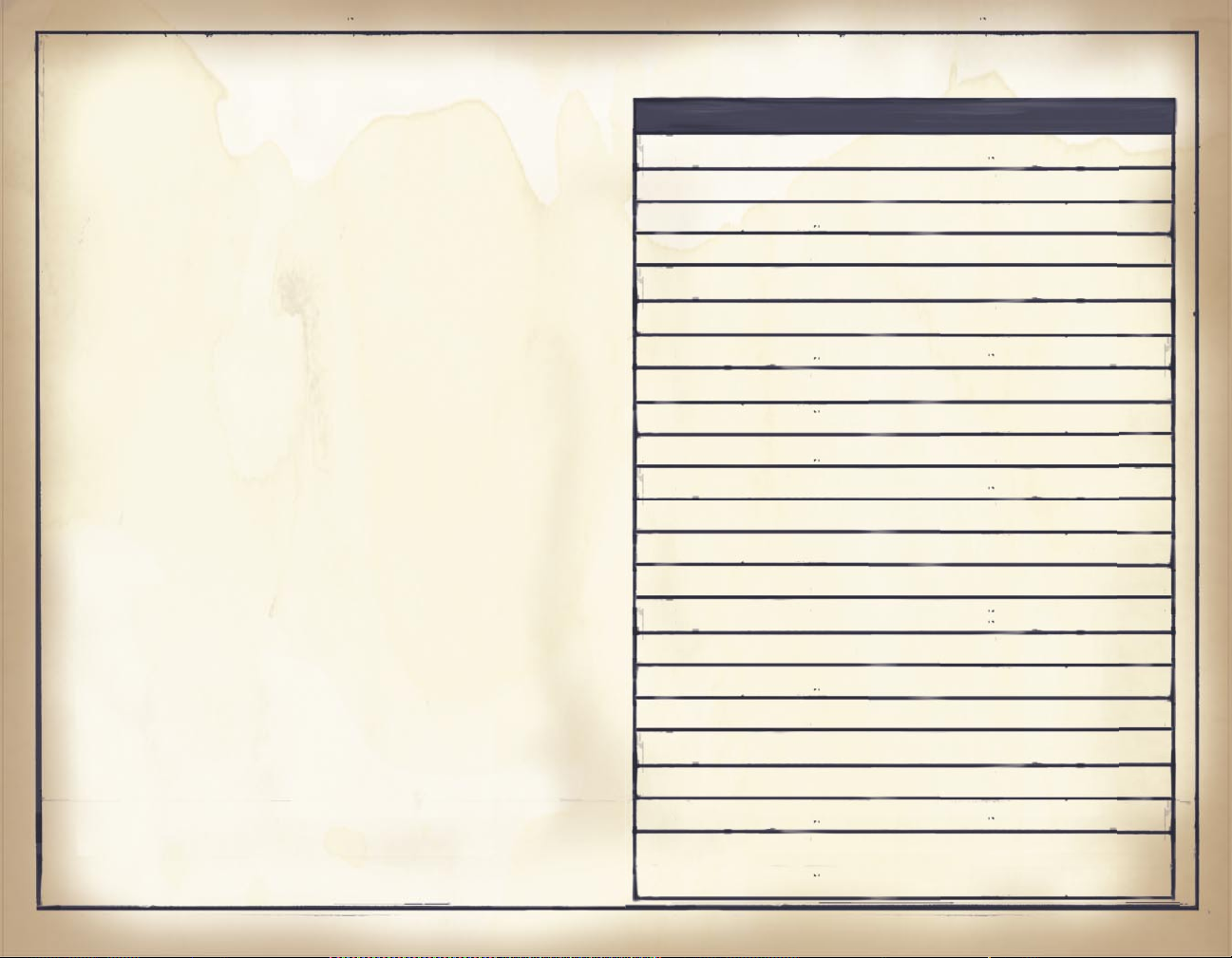

THE INSTRUMENT PANEL

The instrument panel in your aircraft provides key

information about your position and your aircraft’s

health, among other things. It may look confusing and

foreign at rst, but you’ll come to rely on it after you

get used to it. Every aircraft has a different panel,

but for the most part, each panel features the same basic

elements.

- Gauges: Each aircraft has its own set of gauges that

indicate how your aircraft is performing and where

you’re going.

- Mouse rollover Help: While you y, you can nd out an

instrument’s name by pointing to the instrument with

the mouse.

Although there area several aircraft for each

nationality in Microsoft® Combat Flight Simulator 3,

you only need to learn three basic instrument sets. The

accompanying images show the basic set of instruments for

American, German, and British aircraft.

* * *

AMERICAN GERMAN BRITISH

- 4 -

HEADING INDICATOR ALTIMETER AIRSPEED ARTIFICIAL HORIZON

Page 6

- 5 -

FLIGHT CONTROLS

PRIMARY CONTROL SURFACES

Ailerons

Moving the stick left and right moves your plane’s

ailerons. These hinged rectangular surfaces are located

on the trailing edges of the wings near the wing tips,

and they control your plane’s banking (rolling) motion.

The ailerons move in opposite directions. If you move

the stick left, the left aileron moves up, reducing lift

(upward force) on the left wing. At the same time the

right aileron moves down, increasing lift on the right

wing. The result? The airplane banks (rolls) to the left.

When the wings reach the angle of bank you want, center

the stick. Banking with the ailerons is what causes a

plane to turn

.

Note: All keyboard commands noted in this manual are the default

Combat Flight Simulator 3 combat keyboard commands. If you

want to change your settings to your own keyboard commands

or to Microsoft Flight Simulator keyboard commands, click

Control Options on the Options tab and follow the prompts.

KEYBOARD

ACTION JOYSTICK (NUM LOCK ON)

Bank left/ Move joystick left Num Pad

4

Left aileron

Bank right/ Move joystick right Num Pad

6

Right aileron

Stop banking/ Center joystick Num Pad

5

Center ailerons

Aileron

Trim

Rudder

Elevator Flap

You control an airplane’s movement with the stick and

rudder pedals. In Combat Flight Simulator 3 (CFS3), the

stick and rudder are simulated by the joystick and rudder

pedals (both optional), and the keyboard. No matter what

your setup, you’ll use these controls to move control

surfaces that cause the airplane to turn, climb, and

descend.

Page 7

- 6 -

Rudder

Pushing the rudder pedals moves your plane’s rudder.

The rudder is a hinged surface located on the vertical

stabilizer of the tail. It controls your craft’s yawing

(pivoting) motion to the left and right. The rudder is

used to counteract your plane’s tendency to yaw in the

direction opposite a turn, and to counteract your engine’s

torque. (Learn more about the effects of torque in “A few

words about torque” later in this handbook.)

JOYSTICK/RUDDER KEYBOARD

ACTION PEDALS (NUM LOCK OFF)

Yaw left/ Twist joystick left (not Num Pad

0

Left rudder all joysticks twist) or

press left rudder pedal

Yaw right/ Twist joystick right or Num Pad

ENTER

Right rudder press right rudder pedal

Yaw center/ Center joystick or Num Pad

5

Neutralize center rudder pedals

rudder

Elevator

Moving the stick forward and backward moves your

plane’s elevator. This hinged surface is located on

the horizontal stabilizer of the tail and controls your

airplane’s pitch (up and down) motion. Moving the stick

forward decreases pitch attitude (lowers the nose), while

moving it back increases pitch attitude (raises the nose).

The elevator controls pitch attitude, but it doesn’t

necessarily make your plane climb or descend. You’ll learn

why in “Basic Flight Maneuvers” later in this handbook.

KEYBOARD

ACTION JOYSTICK (NUM LOCK OFF)

Pitch up Move joystick back Num Pad

2

Pitch down Move joystick forward Num Pad

8

Page 8

- 7 -

Flaps

Flaps are hinged surfaces on the trailing edges

of the wings, next to the fuselage. They are usually

used during takeoff and landing. When extended, the

aps increase lift by helping the wings de ect more air

downward, which means your plane can ascend more rapidly.

They also increase drag (the resistance of the air),

allowing your aircraft to descend more steeply without

building up speed.

The aps are extended in increments, which vary

depending on the aircraft. As you extend or retract the

aps, be prepared for changes in pitch. The nose will rise

or fall from the resulting change in lift. Add forward- or

back-pressure on the stick to maintain the pitch attitude

you want, and after the airspeed stabilizes, use elevator

trim to relieve that pressure.

ACTION KEYBOARD

Retract aps fully

SHIFT+V

key

Retract aps in increments

V

key

Extend aps fully

SHIFT+F

Extend aps in increments

F

key

SECONDARY CONTROL SURFACES

Trim

Trim tabs are small, hinged surfaces on the elevator,

rudder, and ailerons that help you maintain speci c

control positions without needing to exert pressure

on the controls. Moving a trim tab one way de ects the

elevator, rudder, or aileron the other way. When your

airplane is properly trimmed, you can y “hands off,”

applying only occasional, small control-pressures to

compensate for the occasional bump or minor changes in

heading. (On some aircraft, elevator trim moves the entire

elevator slightly, instead of moving a tab on it.)

Use trim to relieve control pressure, not to y.

If you want to change the airplane’s attitude (position

relative to the horizon), rst move the stick or rudder

and change the power setting if necessary. Then, after

the airplane stabilizes, trim off the pressure.

ACTION KEYBOARD (NUM LOCK OFF)

Aileron trim left

CTRL+

Num Pad

4

Aileron trim right

CTRL+

Num Pad 6

Rudder trim left

CTRL+

Num Pad

0

Rudder trim right

CTRL+

Num Pad

ENTER

Elevator trim up Num Pad

1

Elevator trim down Num Pad

7

Page 9

- 8 -

ENGINE CONTROLS

ACTION COMMAND

Engine auto-start

E

key

Throttle (decrease)

-

(MINUS SIGN)

Throttle (increase)

=

(EQUAL SIGN)

10% throttle Keyboard

1

20% throttle Keyboard

2

30% throttle Keyboard

3

40% throttle Keyboard 4

50% throttle Keyboard

5

60% throttle Keyboard

6

70% throttle Keyboard

7

80% throttle Keyboard 8

90% throttle Keyboard 9

100% throttle Keyboard 0

Prop (decrease rpm)

SHIFT+-

(MINUS SIGN)

Prop (increase rpm)

SHIFT+=

(EQUAL SIGN)

Prop (min pitch)

CTRL+F6

Prop (max pitch)

CTRL+F7

Mixture (lean)

CTRL+-

(MINUS SIGN)

Mixture (enrich)

CTRL+=

(EQUAL SIGN)

Mixture (idle cutoff)

CTRL+SHIFT+F6

Mixture (full rich)

CTRL+SHIFT+F7

Engage War Emergency Power (WEP)

W

key

or Water/Methanol-Water

injection (toggle)

To start the engine automatically, press the E key:

You’ll see the controls move, and then you’ll hear the

engine start. If you’d rather do all the work yourself,

you can start the engine manually. For details, see the

next section in this handbook, “Starting the engine.”

Your aircraft has three basic engine controls:

- Throttle control lever (the control that has the most

direct effect on power)

- Propeller control lever (to adjust the prop’s pitch

angle and thus the prop’s rotation speed)

- Mixture control lever (to adjust the air/fuel mixture

as the airplane climbs and descends)

All three levers can be controlled with the keyboard.

You can also control the throttle with a slider or wheel

on your joystick (optional).

Page 10

Starting the engine

In most missions you’ll start on the runway, all

lined up and ready to go. Start your engine, and follow

your squadron mates into the sky!

To automatically start the engine

- Press the E key.

To manually start the engine

1. Set the prop control lever to the Max. pitch

position (CTRL+F7).

2. Set the mixture control lever to the Full Rich

position (CTRL+SHIFT+F7). If you’re ying a jet,

instead move the fuel valve to On (CTRL+SHIFT+F7).

3. Set the throttle control lever to the Idle

position, and then move it forward just a bit

(MINUS and EQUAL keys).

4. Turn the battery switch to On (CTRL+B).

5. If your aircraft has a magneto, click the Magneto

switch to move it to the Both position (CTRL+M or

SHIFT+M).

6. Engage the starter and then release it (CTRL+S).

Throttle control lever

The throttle regulates the amount of fuel and air

that enters the engine cylinders. When fully open, the

throttle allows the maximum amount of fuel and air to

enter the system to produce maximum power. When the

throttle is closed, only a small amount of fuel and air

can get in, and the engine produces minimum power.

To open the throttle, move the control lever forward.

To close it, pull it backward. The manifold pressure

gauge on the instrument panel shows the pressure of the

air moving into the engine’s cylinders, and it gives

an approximate measurement of engine power. Generally

speaking, the higher the manifold pressure, the more

power you have.

- 9 -

Page 11

- 10 -

Mixture control lever

Because your aircraft’s engine operates over a wide

range of altitudes, you can adjust the air/fuel mixture

for maximum ef ciency as you climb into less dense air or

descend into more dense air. A mixture that is too rich

contains too much fuel for the amount of air available at

that altitude and will cause the engine to run rough and

lose power. The solution is to “lean the mixture.” As you

climb, make the mixture leaner by pulling the mixture

control lever backward. Don’t lean the mixture too much,

though--a mixture that is too lean can cause the engine

to overheat or cause detonation (a sudden, explosive

combustion of fuel within the cylinders).

Note: By default, mixture control is handled automatically in

Combat Flight Simulator. To adjust the mixture manually,

click Realism Options on the Options tab, and in the Aircraft

section clear the Auto mixture check box.

Propeller control lever

Adjusting the propeller in an airplane is a lot like

using gears in a car. In low gear the engine turns fast

to get you moving. Once you’re underway, there’s no need

to use a lot of power, so you shift to a higher gear to

make more ef cient use of less power. In an airplane,

the propeller control lever indirectly changes the

angle at which the propeller blades meet the air, which

affects how fast the engine turns. The tachometer on the

instrument panel shows how fast your engine is turning.

During takeoff, in combat, and during landing (in

case you need to abort and take off again) you’ll need

every bit of power your engine can develop. So during

these three phases of ight, keep the propeller lever

forward: the angle of the blades will be low, slicing

through the air easily so you can get the engine’s full

power (like using a low gear in a car). During cruise,

you can pull the propeller lever backward a bit: the

angle of the blades will increase and take a bigger bite

out of the air, making more ef cient use of the engine’s

power (like using a high gear in a car).

Because your aircraft has a constant-speed propeller,

any time you change the throttle setting a governor

automatically adjusts the angle of the blades to maintain

that speed. This reduces your workload!

Note: The default setting of your airplane’s prop control lever is the

forward (high speed) position. Don’t change this setting if

you don’t need to. As a ghter pilot, you’ll want this setting

most of the time. Leaving the prop control lever forward during

cruising ight means you’ll y less ef ciently and use more

fuel, but it won’t cause any damage.

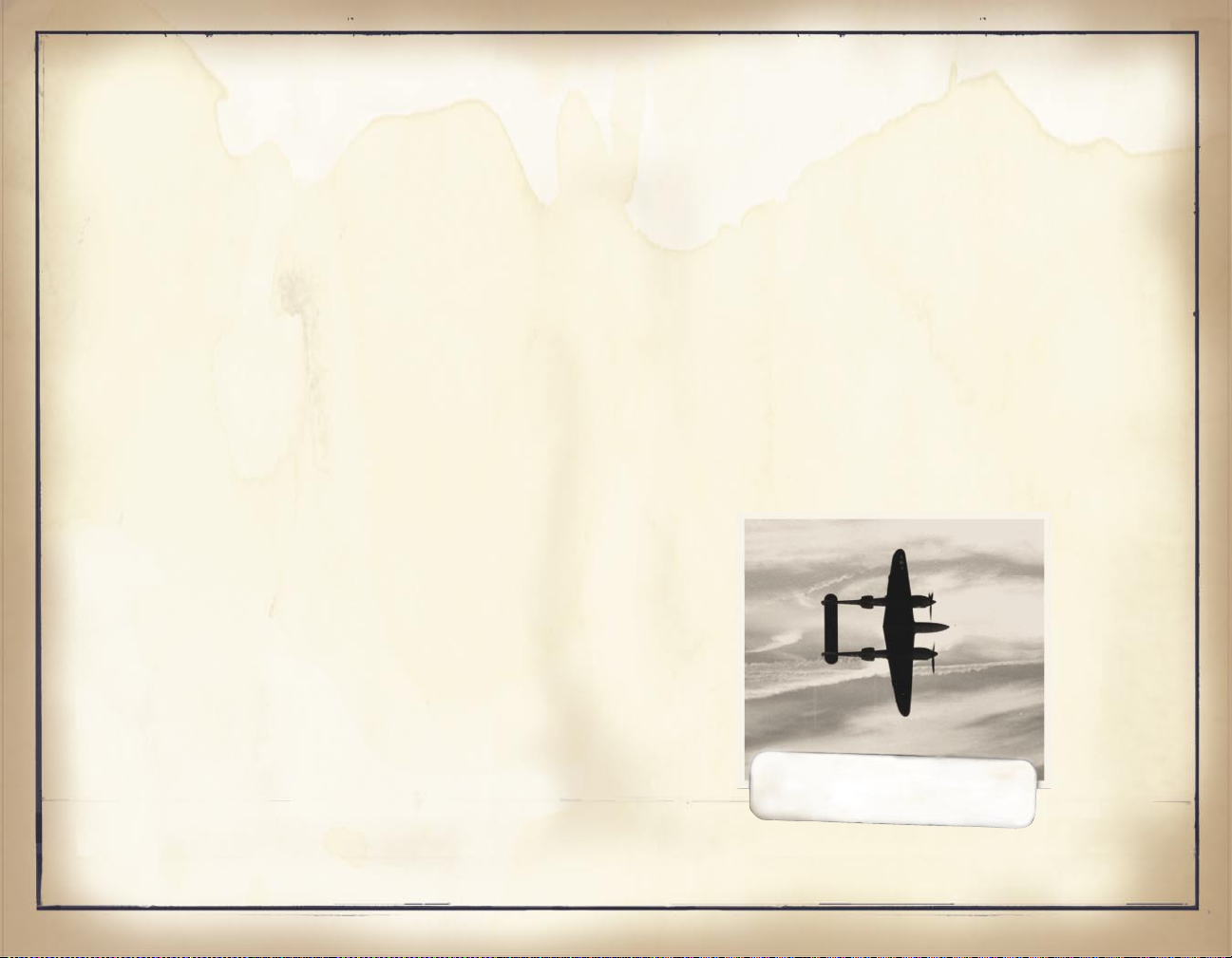

P-38 LIGHTNING BANKS FOR

BOMB RUN.

Air Force Historical Research Agency Photo

Page 12

GETTING UP AND BACK

TAXIING

When you’re taxiing, remember that if you’re ying

a taildragger (an aircraft with a tailwheel instead of

tricycle landing gear), it’s hard to see over the nose

when you’re on the ground. To get a good view, make gentle

S-turns by using the rudder pedals, and look to either

side. Aircraft with tricycle landing gear are easier to

manage on the ground--you can see over the nose so you

just use the rudder to steer the aircraft.

Note: When auto-rudder is set to On, you can steer by moving

the stick left and right—the ailerons and the rudder are

connected. To turn auto-rudder on or off, click Realism Options

on the Options tab, and in the Aircraft section select or clear

the Auto-rudder check box.

To taxi

1. Hold the stick back to keep the tailwheel on the

ground (with a taildragger).

2. Taxi with the throttle at idle and use the brakes

as little as possible.

3. To turn sharply, brake just on the side you’re

turning toward (press the COMMA for the left brake

or the PERIOD for the right brake).

4. When you reach the runway, stop at a right angle

and scan the sky for any approaching aircraft.

TAKING OFF

Taking off is something even experienced pilots

get excited about. But don’t lose your head during this

critical stage of ight. Every plane performs differently

during takeoff, so use the checklists in online Help for

specic aircraft specs. Here are some general guidelines:

To take off (taildragger)

1. Line up on the runway. LOCK THE TAILWHEEL

(SHIFT+L). This is important as the airplane’s

left turning tendency is exaggerated in a

tailwheel airplane.

2. Incrementally add some aps if appropriate in your

airplane (press the F key).

3. Make sure the prop control lever is in the full

forward position (default setting), and then

smoothly advance the throttle to takeoff power.

See “Engine Controls” earlier in this handbook

for details. Do not jam the throttle forward, or

torque effect may cause loss of control!

4. Maintain back-pressure on the stick to keep the

tailwheel on the ground until your rudder becomes

effective.

5. Slowly ease forward on the stick so the tail

rises.

6. At your aircraft’s takeoff speed, gently pull back

on the stick and y the plane off the runway.

7. Once airborne, retract the landing gear (press the

G key) and aps (press the V key repeatedly until

the aps are fully retracted).

8. Adjust your pitch attitude to climb out at your

plane’s best-climb speed.

- 11 -

Page 13

- 12 -

Air Force Historical

Research Agency Photo

To take off (tricycle landing gear)

1. Line up on the runway.

2. Incrementally add some aps if appropriate in your

airplane (press the F key).

3. Make sure the prop control lever is in the full

forward position (default setting), and then

smoothly advance the throttle to takeoff power.

See “Engine Controls” earlier in this handbook

for details.

4. At your aircraft’s takeoff speed, pull back on

the stick so the nose rises.

5. Once airborne, retract the landing gear (press

the G key) and aps (press the V key repeatedly

until the aps are fully retracted).

6. Adjust your pitch attitude to climb out at your

plane’s best-climb speed.

LANDING

A good landing starts with a good approach,

and that means setting up with the right speed and

con guration. Every plane lands differently, so check

the online Help checklists for best approach speeds, gear

extension speeds, and ap settings. Here are some general

guidelines:

To land (taildragger)

1. Slow your plane down to its maximum gear-extension

speed.

2. Lower the landing gear (press the G key) and start

a shallow 500-foot-per-minute descent toward the

runway. Watch the descent rate by looking at the

runway and occasionally glance at the rate of

climb/descent indicator on the instrument panel.

Note: If your hydraulic system is damaged, you may need to

manually pump the landing gear down (press SHIFT+G key

repeatedly).

3. Incrementally add aps to steepen the approach

(press the F key).

4. Maintain the approach speed recommended for your

aircraft, and use pitch to control airspeed.

To speed up, move the stick forward slightly to

lower the nose. To slow down, gently pull the

stick back.

5. Pick a touchdown point and use the throttle to

control descent rate. If the touchdown point

appears to move down your windscreen, decrease

power: you’re too high. If the touchdown point

seems to move up, add power: you’re too low.

6. As you cross the end of the runway, ease the

throttle back to idle.

XIX TAC THUNDERBOLT

LANDS ON A NEW AIRSTRIP

IN FRANCE.

Page 14

7. Flare about 20 feet above the runway by pulling

back slowly on the stick to raise the nose

slightly, and touch down in a nose-high, “threepoint” attitude. All three wheels should contact

the ground at the same moment. Hold the stick full

back after you touch down.

8. During and after touchdown, maintain directional

control with the rudder. (If auto-rudder is on,

then move the stick left and right--the ailerons

and the rudder are connected.)

9. After the aircraft has slowed to walking speed,

apply the brakes (press the B key).

10. Unlock the tailwheel to taxi (SHIFT+L).

To land (tricycle landing gear)

1. Slow your plane down to its maximum gear-extension

speed.

2. Lower the landing gear (press the G key) and start

a shallow 500-foot-per-minute descent toward the

runway. Watch the rate of climb/descent indicator

on the instrument panel.

Note: If your hydraulic system is damaged, you may need to

manually pump the landing gear down (press the SHIFT+G

keys).

3. Incrementally add aps to steepen the approach

(press the F key).

4. Maintain the approach speed recommended for your

aircraft, and use pitch to control airspeed.

To speed up, move the stick forward slightly

to lower the nose. To slow down, gently pull

the stick back.

5. Pick a touchdown point and use the throttle to

control descent rate. If the touchdown point

appears to move down your windscreen, decrease

power: you’re too high. If the touchdown point

seems to move up, add power: you’re too low.

6. As you y across the end of the runway, ease the

throttle back to idle.

7. Flare about 20 feet above the runway by pulling

back slowly on the stick to raise the nose

slightly, and touch down on the main landing gear

rst. After you touch down, hold the stick full

back to keep the nose wheel off the ground until

it gently settles as you slow.

Note: With tricycle gear aircraft, you don’t want all three wheels

touching simultaneously—you’ll bounce.

8. During and after touchdown, maintain directional

control with the rudder. (If auto-rudder is on,

then move the stick left and right--the ailerons

and the rudder are connected.)

9. After the aircraft has slowed to walking speed,

apply the brakes (press the B key).

* * *

USING CHECKLISTS

Good pilots don’t rely solely on memory. As you y,

you can view checklists for takeoff, cruise, descent, and

landing to help you with these important phases of ight.

To display the checklist, press F1 to display Help, and

then click the link for the checklist you want to use.

- 13 -

Page 15

- 14 -

Air Force Historical

Research Agency Photo

Air Force Historical

Research Agency Photo

BASIC FLIGHT MANEUVERS

FLYING STRAIGHT-AND-LEVEL

Flying straight-and-level may look simple, but it’s

one of the more dif cult maneuvers to master. Because

hotshot pilots like to be in control, they overdo it most

of the time and interfere with their airplane’s basic

stability. Like a balancing act, straight-and-level ight

requires that you make smooth, small corrections to keep

from wobbling all over the sky. There are two components

to ying straight-and-level: holding a constant altitude

and holding a constant heading

Hold a constant altitude

Keep an eye on the altimeter. If your altitude starts

to change, make small, smooth corrections on the throttle

or the stick. Use the stick to correct deviations of

less than 100 feet. If your altitude has deviated more

than 100 feet, you may want to add or reduce power a bit.

Use elevator trim to keep the pitch attitude where you

want it.

To slow down without losing altitude

- Reduce power and keep the nose from falling by gently

pulling back on the stick.

To speed up without gaining altitude

- Add power and keep the nose from rising by gently

pushing forward on the stick.

Hold a constant heading

Check the heading indicator on the instrument panel

frequently to make sure the nose is pointed in the right

direction. Crosscheck the turn indicator and the wing tips

to hold the wings level and to correct minor deviations.

Pick a point on the horizon and keep ying toward it.

Use aileron trim and rudder trim if available to make the

job easier.

There are four basic maneuvers to master: ying

straight-and-level, turning, climbing, and descending.

Practice these maneuvers in Free Flight so you don’t get

shot down.

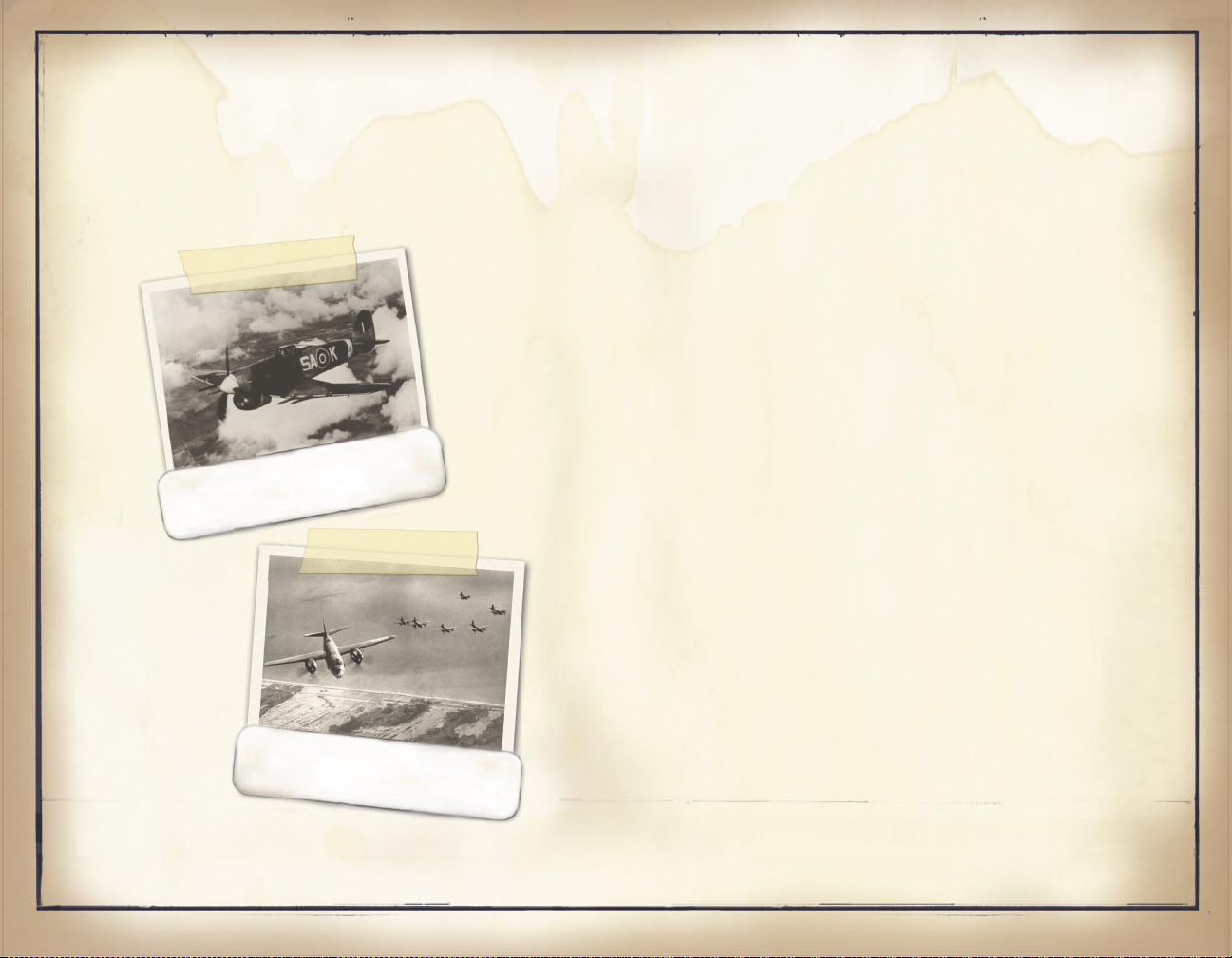

HAWKER TYPHOON IN FLIGHT.

B-26S OVER THE COAST OF

FRANCE.

Page 16

TURNING

You might think that the faster you go, the faster

you can turn. But ying fast in a turn means more

centrifugal force, and that means a bigger turn radius.

The result? The turn takes longer! So sometimes to turn

faster you’ll need to y slower. How fast you can turn

(and how much sky you can do it in) depends on your bank

angle and your airspeed. How well you can turn depends

on your ability to simultaneously bank the wings and add

both rudder and up-elevator while you “paint the horizon”

with the nose of the plane.

Bank the wings

Move the stick right or left to manipulate the

ailerons and initiate a bank. Center the stick when you

reach the bank angle you want. By banking the wings, you

deect some of their vertical lift sideways. This part

of the airplane’s total lift is called the “horizontal

component of lift,” and it is this force that pushes

the plane around in a turn.

Add some rudder

Your plane will have a tendency to yaw (pivot)

opposite the turn. So as you bank, apply some rudder

pressure in the same direction as the turn using rudder

pedals, a joystick that supports rudder control, or the

keyboard (press the numeric keypad 0 key for left rudder

or the keypad ENTER key for right rudder). As you bank

left, add a little left rudder, and vice versa. How much

rudder? Just enough to keep the ball/needle in the turn

indicator centered. In theory, you could skid an airplane

through a turn without banking using just the rudder,

but it’s an inefcient and uncomfortable way to change

direction. (In combat, though, you can use skidding to

confuse an enemy on your tail.)

Note: Auto-rudder is automatically set to Off if rudder controls are

detected. Otherwise auto-rudder is automatically set to On.

When auto-rudder is set to On, the rudder moves automatically

to maintain coordinated ight in turns, making your airplane

easier to y. To turn auto-rudder on or off, click Realism

Options on the Options tab, and in the Aircraft section select or

clear the Auto-rudder check box.

Use some up-elevator

Because some of the lift is deected sideways in

a turn, you need to raise the nose slightly to generate

more lift. Add a little back-pressure on the stick as

you roll into a turn. The steeper the turn, the more upelevator pressure you add to maintain altitude. You might

even need to add some power. As you roll out of the turn,

remember to relax the back-pressure on the stick.

“Paint the horizon”

To maintain level ight as you turn (or to turn

while climbing or descending at a constant speed and

rate), “paint the horizon” with the nose--keep the

pitch attitude the same after you’ve started the turn.

In general, if the nose moves up as you’re turning, you

climb. If it moves down, you descend.

* * *

CLIMBING

There are two ways to get your aircraft to go up-by using momentum or by using excess thrust.

Use momentum

Pull back on the stick to create a “hill” and your

airplane will start to climb. You’ll go higher but you’ll

also slow down--just like climbing a hill on a bicycle.

Pulling back on the stick to go up means you trade

airspeed for altitude.

- 15 -

Page 17

Use excess thrust

A sustained climb is made possible by using thrust

to pull your plane up the “hill.” Set the steepness of

the “hill” by pulling back on the stick. Then add power

with the throttle to pull yourself up, just like pedaling

a bike faster. Using excess thrust is a way to gain

altitude without losing airspeed.

Every aircraft has a best-climb speed. With full

power, this is the speed where the airplane gains altitude

fastest in a sustained climb. Adjust your speed by raising

or lowering the nose.

* * *

DESCENDING

There are two ways to get your aircraft to descend-by diving or by reducing power.

Dive

Push forward on the stick to make a steep “hill”

to dive down. As you descend, your speed will increase.

Pushing forward on the stick to go down means you trade

altitude for airspeed. Be careful! If the air traveling

over your wings in a high-speed dive exceeds the speed of

sound, your control surfaces may lose their effectiveness

and you may not be able to pull out of the dive.

Reduce power

To descend more slowly than in a dive, make a

shallow “hill” with the stick (or leave the stick where

it is), and reduce your throttle a bit. When the engine

stops producing enough thrust to maintain level ight,

your plane will start to glide slowly toward the ground.

Descending at low power is a way to lose altitude without

gaining airspeed.

Every aircraft has a best-glide speed. If the engine

quits, this is the speed that lets the airplane glide the

farthest. Adjust your speed by raising or lowering the nose.

DON’T STALL!

A stall has nothing to do with an airplane’s engine

sputtering. You can stall at any airspeed--even when the

plane is in a fast dive!

A stall has to do with the angle of attack--the angle

at which a wing meets the oncoming air (not the angle

of the wing to the ground). If you increase the angle of

attack too much, the wings won’t generate enough lift to

counteract the plane’s weight--so you stall--your plane

starts to fall toward the ground. (See “Why it All Works”

later in this handbook.)

A wing always stalls at the same critical angle of

attack, at any attitude, no matter how fast or slow you’re

ying. More fuel and more ammunition make the plane weigh

more. But so does maneuvering. In a turn, for example,

centrifugal force will push you into your seat, so it’s

as if both you and the airplane are heavier. Then you

need more lift to offset that weight and maintain level

ight. To get the additional lift, you have to increase

the angle of attack--but that puts you closer to the

critical angle of attack--and a stall.

So go easy on the stick when you’re maneuvering. Just

because you’re going fast doesn’t mean you can’t stall!

Warning signs

A stall near the ground can be deadly. But you can

learn to sense one coming and prevent it. As the air

owing over the top of the wings gets turbulent, you’ll

feel a slight shaking or buffeting, and you’ll see a

red stall light illuminate on the instrument panel.

Immediately reduce the angle of your climb or dive.

- 16 -

Page 18

Recover promptly

The only way to recover from or prevent a stall is to

reduce the angle of attack. Apply forward-pressure on the

stick, and add some throttle to compensate for the loss

of altitude. If you continue to pull back on the stick

(the intuitive thing to do, since your nose is dropping!),

your ship will not recover. If one wing drops before the

other, the stall may become a spin.

* * *

DON’T SPIN!

You go into a spin when one wing stalls more than

the other wing. The plane corkscrews toward the ground

at a steep angle of descent and at a low airspeed. Sound

scary? It’s no big deal once you’ve done a few. But

understand that for an airplane to spin it must rst

be stalled. Avoid a stall and you’ll avoid a spin.

Note: When auto-rudder is set to On, it’s unlikely a stall will develop

into a spin. To turn auto-rudder on or off, click Realism Options

on the Options tab, and in the Aircraft section select or clear

the Auto-rudder check box.

You don’t have many options if you get into a

spin close to the ground. Press the O key three times

(that’s the letter O) and bail out! If you think you have

enough altitude to recover (at least 5,000 feet in most

aircraft), here’s what to do.

To maneuver out of a spin

A handy acronym to remember to help you handle spins

is PARE:

P Power off

A Ailerons neutral

R Rudder opposite of the direction of spin

E Elevator forward to brake the stall

1. Reduce the throttle.

2. Center the stick--that neutralizes the ailerons.

3. Apply full rudder opposite the direction of your

spin.

4. Relax the back-pressure on the stick to decrease

the angle of attack and break the stall. (In

some planes you’ll have to “pop” the stick

forward sharply.) As soon as the rotation stops,

neutralize the rudder.

As your airspeed builds after recovery, smoothly pull

back on the stick to recover from the dive. As the pitch

attitude returns to level ight, smoothly add power to

maintain your airspeed.

- 17 -

Page 19

- 18 -

Air Force Historical

Research Agency Photo

WHY IT ALL WORKS

LIFT

Lift is the upward force produced by a wing as it

moves through the air. It’s the force that counteracts

the gravity of an airplane’s weight.

There are four forces that affect an airplane in

ight, and they act in pairs: lift opposes weight, and

thrust opposes drag. To get your crate to behave like

you want it to, you’ve got to manage these four forces.

Understanding them makes it easier.

Thrust

Lift

Drag

Weight

How a wing works

Ask engineers how a wing works and they’ll go on

about circulation theory, the shape of the wing, and

Bernoulli’s Theorem. They’ll talk your ear off, but the

most useful explanation for a combat pilot learning to

y in a hurry is admittedly simplistic: a wing keeps an

airplane up by de ecting the air down

.

The angle that matters most

The angle at which a wing meets the air is called

the angle of attack. This is not the angle between the

airplane’s nose and the horizon. It’s the difference

between where your wing is pointing and where it’s

actually going.

AN EARLY ALLISON-POWERED

MUSTANG SPORTS A CAMO

PAINT JOB.

Page 20

Changing the amount of lift

You can control the amount of lift a wing generates

by adjusting two things: speed and angle of attack. To

produce a certain amount of lift at low speeds, the air

must be deected using a large angle of attack. To produce

the same amount of lift at high speeds, the air must be

deected using a small angle of attack. If the speed is

very low, the angle of attack you’ll need to maintain

lift will be so large at a certain point (the critical

angle of attack) that the air cannot ow smoothly over

the wing, and the wing will stall.

You can also add lift by extending the aps, which

increase the curvature of the wing. With the aps

extended, more air is deected downward, so there is

more lift. Flaps also cause an increase in drag.

Playing with lift

Think about what happens to your hand when you stick

it out the window of a moving automobile, letting it get

bounced around by the wind. If the car speeds up, you

can reduce the angle of your hand relative to the wind

(the angle of attack) to keep it from blowing upward.

If the car slows down, you can increase the angle of your

hand to keep it from falling downward. If you increase

the angle of your hand too much, it will stop generating

lift, and fall (stall).

WEIGHT

Weight opposes lift--it’s the downward force caused

by gravity pulling an airplane toward the center of the

earth.

For your ship to y, the wings must develop enough

lift to counteract its weight. The real weight of your

aircraft changes as fuel and ammunition are used up. But

changes in apparent gravity (measured in G-forces) are

caused by maneuvering. For example, a level turn with

a 60-degree bank puts a 2-G load on the plane and its

pilot. Both seem to weigh twice as much as they do when

in straight-and-level ight--and in a way they do--because

of the increase in apparent gravity.

Compensating for G-forces

During maneuvers, you have to adjust the amount of

lift to compensate for the changes in weight caused by

G-forces. To stay level during a steeply banked turn, for

example, you’ll need to raise the nose slightly (increase

the angle of attack) and add more power (thrust) to

produce more lift to balance you out.

Blackout and redout

Most maneuvers create only slight, brief G-forces.

But combat maneuvers produce strong, rapidly changing Gforces that can be uncomfortable, or even incapacitating.

Positive Gs: Rapid pull-ups and steeply banked,

level turns create positive G-forces that act toward

your feet. As the blood circulation to your brain

decreases, your visual eld narrows and you may experience

blackout: You’ll lose color vision and eventually lose

consciousness.

- 19 -

Page 21

- 20 -

Negative Gs: Rapid pushovers and certain aerobatic

maneuvers create negative G-forces that act toward

your head. As the forces increase, you’ll experience

discomfort, headache, “redout” caused by excessive blood

ow to your eyes, and even unconsciousness. Most pilots

have a harder time handling negative Gs than positive Gs.

To turn the redout and blackout on or off in Combat

Flight Simulator 3, click the

Realism Options on the

Options tab, and then in the Visuals section select or

clear the

G-effects check box.

THRUST

Thrust is the forward force provided by an airplane’s

propeller or a jet engine’s exhaust, and it is opposed

by drag (the resistance of the air as the airplane moves

through it).

An airplane’s propeller creates thrust in the same

way its wings create lift: air is de ected backward,

so the propeller (and the aircraft) move forward. The more

powerful the engine (and the bigger the propeller), the

greater the thrust, and the faster the airplane can y.

Thrust is also the most important factor in determining

a plane’s ability to climb.

* * *

DRAG

Drag is the rearward-pulling force that opposes

thrust, and it has two components: parasite drag and

induced drag.

Parasite drag

Parasite drag is caused by friction between the air

and an airplane’s structure. The more things there are

sticking out into the air ow (antennas, landing gear,

bombs, etc.), the higher the parasite drag. Your plane

is designed to have as little parasite drag as possible,

but the faster you go, the more there will be.

Induced drag

As the angle of attack increases, lift pulls an

airplane upward and backward. The upward component of

lift is called “effective lift”; the backward component

is called “induced drag.” Effective lift counteracts

weight to keep the airplane ying. Induced drag

counteracts thrust and slows the airplane down. The slower

you go (the bigger the angle of attack), the greater the

induced drag. Eventually, you’ll need to add more power

to generate the lift necessary to remain aloft.

Page 22

Playing with induced drag

You can understand how induced drag works by sticking

your hand out the car window again. If you hold your hand

relatively at (at a low angle of attack), your hand gets

pushed upward and slightly backward. As you increase the

angle of attack, you’ll notice an increase in both the

upward force (effective lift) and in the backward force

(induced drag). Increase the angle too much and your hand

will stall.

A few words about torque

“Torque” is a catch-all term used to describe your

plane’s tendency to yaw and bank in either one direction

or the other at certain power settings. A ghter’s

powerful engine and big propeller make this effect very

pronounced, especially when the throttle’s on high but

the airspeed is low (as during takeoff). To counter these

turning tendencies, you’ll need to use the rudder and

ailerons, although torque can be used to your advantage

in a dogght.

What causes torque? Four phenomena--reactive force,

spiraling slipstream, gyroscopic precession, and P factor.

Reactive force

When the powerful engine of a ghter plane turns the

propeller in one direction, there is an equal and opposite

force that makes the plane roll in the other direction.

When your throttle’s high but your airspeed’s low (as

during takeoff), the plane will roll in a direction

opposite to the rotation of the prop. This effect is most

pronounced during acceleration.

Spiraling slipstream

A propeller’s spiraling slipstream (the air mass

that the propeller propels behind it) hits one side of

the tail and causes the nose of the plane to yaw (rotate

left or right around the vertical axis) in the same

direction that the reactive force causes it to roll.

The result? An even stronger tendency to turn.

Gyroscopic precession

Because it’s big and spins rapidly, your plane’s

propeller behaves like a gyroscope. This makes it subject

to the effects of gyroscopic precession. When a force

acts on a gyroscope, the gyroscope behaves as if the

force were applied at a point 90 degrees in the direction

of rotation. If your plane’s propeller turns clockwise

(viewed from the cockpit), then when the tail comes up

on the takeoff run--the nose goes down--and gyroscopic

precession makes the plane swerve to the left.

P factor

A propeller is a bunch of small wings moving around

a crankshaft. Each propeller blade produces a certain

amount of thrust. When an airplane is ying at a high

angle of attack, the downward-moving propeller blades have

higher angles of attack and produce more thrust than the

upward-moving blades. The result is asymmetric propeller

loading--or P factor--which creates a yawing motion.

- 21 -

Page 23

- 22 -

BASIC AEROBATIC MANEUVERS

AILERON ROLL

Purpose

Rarely used on its own in battle, the aileron roll is

worth learning because it’s part of many combat maneuvers.

To perform

Raise the nose slightly. Pick a reference point on

the horizon, then smoothly push the stick all the way

to one side and hold it there. Use the stick to keep the

nose on the reference point, then center the stick as the

wings approach level again. Practice stopping the roll

partway through for a half-roll. That’s an easy way to

get inverted quickly.

There’s ying an airplane, and then there’s ying

an airplane in combat. Get familiar with these basic

aerobatic moves before you learn combat maneuvers and

you’ll have a ghting chance! Practice these maneuvers in

Free Flight so you don’t get shot down.

For information on air combat maneuvers, see “Basic

Air Combat Maneuvers” and “Tactical Air Combat Maneuvers”

later in this handbook.

Page 24

- 23 -

BARREL ROLL

Purpose

This basic aerobatic maneuver can be used in combat

to shake an enemy from your tail. You’ll corkscrew through

the sky and lose airspeed, causing your opponent to y

right by.

To perform

Raise the nose, bank sharply left or right, and

gently pull back on the stick to maintain the roll. Hold

the sideways-pressure on the stick as you roll inverted,

then center it when you return to level ight. During this

move, the stick is essentially in the left- or rightrear position. The nose will draw a circle on the horizon

instead of rotating around a point, as in an aileron

roll. If you do a barrel roll perfectly, you won’t lose

any altitude.

LOOP OVER

Purpose

Commonly referred to as a “loop,” this move is a

way to make a vertical circle in the sky and end up back

where you started. Practicing loops will help you get

accustomed to unusual pitch attitudes, rapidly changing

airspeeds, and the effects of G-forces.

To perform

Make sure you have enough airspeed or you’ll stall

at the top of the loop. Slowly pull back on the stick.

As you climb, you’ll lose airspeed. Once inverted, ease

off on the stick. As you start down the back side, add

a little back-pressure and reduce the throttle.

Tip: Watch your left wingtip to see where in the loop you are.

The wing should draw a circle on the horizon.

Page 25

- 24 -

LOOP UNDER

Purpose

A loop under is basically a reverse loop over, but

it’s more useful in combat since you gain speed early.

Your airspeed has to be high to do a loop over, but your

plane has to be high to do a loop under--or you’ll hit

the ground! Make sure you have enough altitude before you

try this one, and don’t pull too many negative Gs. The

negative G-loads most aircraft can handle are half that

of the positive G-loads

.

To perform

Do a half–aileron roll to get inverted, and then pull

back on the stick smoothly. You’ll gain airspeed, which

will let you start up the other side of the loop. As you

start to climb, keep back-pressure on the stick. You’ll

slow down as you become inverted. Push forward on the

stick slightly to stop the loop, and then nish the

maneuver with another half–aileron roll. You should end

up ying in the same direction and at the same altitude

as when you started.

Page 26

Air Force Historical Research Agency Photo

AIR COMBAT

Page 27

TOOLS OF THE TRADE

USING VIEWS

You can use a joystick or keyboard commands to

see everything you’d see from the cockpit of a real

airplane--and more. Different views serve different

purposes. Experiment with them in Quick Combat to learn

your favorite views for tracking the enemy. For a list

of all of the views and view commands, see the “View

Commands” table on the Quick Reference Card.

Note: All keystrokes referred to in this handbook are the Microsoft®

Combat Flight Simulator 3 combat key commands. If you want

to change your key commands to Flight Simulator settings or

your own customized keystrokes, go to the Control Options screen

(click Control Options from the Options tab).

In combat, you’ll probably use several of the

following views at various times. Press F4 to cycle

through the main views (all of the views except Full

and Padlock views).

Virtual Cockpit view

Virtual Cockpit view is the default view; it puts

you right in the pilot’s seat. (Press F3 to cycle between

Full view and Virtual Cockpit view.)

Spot view

Spot view shows you an outside view of your aircraft.

You can position the view anywhere around your own

aircraft (use the arrow keys on the keyboard or the hat

switch on your joystick).

Chase view

Chase view puts you behind your aircraft (press

CTRL+F4 to toggle on and off). Press the TAB key to cycle

between a chase view of your aircraft and other aircraft.

Float view

Float view puts you outside your aircraft and the

camera seems to oat as the aircraft moves (as opposed

to the xed camera in Spot view).

Flyby view

In yby view your aircraft ies past as though lmed

from a stationary camera.

Player Target view

In Player Target view the camera follows the current

target as seen relative to an external view of your

aircraft. You must press the TAB key to target an object.

Full view

Full view provides the best visibility by hiding

the instrument panel (press F3 to toggle on and off).

When used with the Heads Up Display (HUD), it gives you

most of the important information you need. (Press F5

to display the HUD.)

- 26 -

Page 28

- 27 -

Zooming in and out

Using the zoom commands helps you see distant

targets:

- Press the LEFT BRACKET ([) to zoom out.

- Press the RIGHT BRACKET (]) to zoom in.

GETTING A GOOD LOOK

You can use the controls on a joystick or the numeric

keypad to look around as you y. Experiment with the

numeric keypad view commands--they’re easy to use.

When in Cockpit or Full view

The default view is straight ahead. To look

elsewhere, use your joystick’s hat switch (on top of the

joystick) or the number keys on the numeric keypad. For a

list of all view commands, see the “View Commands” table

on the Quick Reference Card.

In most views, you have two ways to look around:

panning and snap-to. Panning provides you with a smooth

continuous view. Snap-to jumps to a particular view,

such as a 90-degree side view. (Toggle Num Lock to switch

between these two options.)

* * *

USING THE HEADS UP DISPLAY

The Heads Up Display (HUD) gives you important

information without the need to look at the entire

instrument panel. The HUD shows your pitch and bank

status, as well as information about your heading,

altitude, speed, ap and gear positions, available

ammunition (guns, cannon, rockets, bombs), and fuel.

Press

F5 to toggle the HUD on or off.

To move any element of the HUD to any position in

the CFS3 window, drag the element to the location where

you want it. To change the measurement system the HUD

uses (between meters and feet), press the

U key.

Padlock view

Padlock view locks your view onto the currently

selected enemy and puts yellow brackets around the plane

for easy identi cation (press the

ACCENT key to toggle on

and off). The padlocked aircraft also appears as a yellow

dot on the Tactical Display (see “Using the Tactical

Display” later in this section of the handbook). To lock

onto a different target, press the

TAB key. To cycle

backwards through the available targets, press

SHIFT+TAB.

Although it takes some practice to use Padlock view

effectively, it’s a good way to stay on the enemy’s tail

once you’re there. When you exit Padlock view, the last

padlocked target still appears as a yellow dot on the

Tactical Display, and the Enemy Indicator points toward

it (see “Using the Enemy Indicator” later in this section

of the handbook). To cancel the target, press

SHIFT+`

(SHIFT+ACCENT).

Moving eyepoint

The eyepoint is where your eyes are looking from in

the cockpit. Moving the eyepoint around in the virtual

cockpit view is useful to see over the cockpit when

landing or getting a different vantage point on anything

you’re trying to view. Experiment with these commands.

ACTION COMMAND

Move eyepoint up

SHIFT+ENTER

Move eyepoint down

SHIFT+BACKSPACE

Move eyepoint backward

CTRL+ENTER

Move eyepoint forward

CTRL+BACKSPACE

Move eyepoint left

CTRL+SHIFT+BACKSPACE

Move eyepoint right

CTRL+SHIFT+ENTER

Return eyepoint to the

SHIFT+CTRL+SPACE

default forward view

Page 29

- 28 -

USING THE ENEMY INDICATOR

The Enemy Indicator is a cone that points to the

nearest enemy aircraft or to an aircraft you have

“padlocked” in Padlock view (see “Using Views” earlier

in this section of the handbook). To nd the enemy plane,

turn in the direction the Enemy Indicator is pointing.

When the enemy aircraft is visible through the front

windscreen, the Enemy Indicator disappears. The Enemy

Indicator is on by default. Press the

I key to toggle

it on or off. Press

TAB to cycle through the enemy

targets. Press

CTRL+TAB to cycle through friendly targets

to check wingmen positions.

USING THE TACTICAL DISPLAY

The Tactical Display helps you keep track of friendly

and enemy aircraft, ships, vehicles, or other surface

targets. The display appears in the upper-left corner

of the screen, but you can drag it anywhere on the screen.

The Tactical Display is on by default. Press

SHIFT+T to

toggle it on or off. Press

CTRL+SHIFT+T to cycle the

range of the Tactical Display.

With this feature you can see the tactical situations

of these areas: Buildings, Ships, Vehicles, Aircraft,

and All. Press the

T key to cycle through the views.

In the Tactical Display, your aircraft is represented

by an airplane symbol (two intersecting lines), friendly

aircraft by a blue dot in the center of the screen, and

enemy aircraft by a red dot. A padlocked aircraft appears

as a yellow dot (see “Using Views” earlier in this section

of the handbook). If you’re not engaged in combat, the

Tactical Display shows information about waypoints in the

mission.

Aircraft

8 NM

Throttle 1 :79

Gun Rnds :1696

Bombs :0

Rockets :0

Fuel :50%

Flaps :0

Gear :0

Ali Falck - 945

All

4 NM

Herman Geiger - 781

Page 30

- 29 -

DISPLAYING AIRCRAFT LABELS

With aircraft labels turned on, it’s much easier

to spot and keep track of other planes. By watching the

distance change you can tell whether an enemy aircraft

is getting closer to you or farther away and if it’s

within range of your guns.

To display or hide aircraft labels, press

CTRL+SHIFT+L. When labels are displayed, you’ll see

the name of each pilot in your formation, as well as

the type of each enemy aircraft you see. You’ll also

see the distance between you and the other aircraft, in

meters or feet. (Press the

U key to toggle between meters

and feet.)

USING GUNSIGHTS

The aircraft in Combat Flight Simulator 3 feature

a re ector gunsight that consists of a circle with

crosshairs and a center aiming point--all projected

onto a glass screen. To hit the target, take your own

aircraft’s movement and that of the enemy’s into account:

once you’re within range, position the center of the

gunsight where you gure the enemy will be when the

bullets land. Then re!

Aircraft

1 NM

Arno Losigkeit - 332

Jacques Winke - 249

Russ Santodomingo - 524

Page 31

- 30 -

USING WEAPONS

The types of aircraft and missions that you y

determine the variety of weapons at your disposal. To

change the weapons loadout, go to the

Aircraft tab prior

to beginning the mission, select your aircraft, and then

on the Aircraft Information Panel, adjust the loadout.

Note that these weapons aren’t guided. You have to aim

carefully, and it takes a lot of practice to hit the

target.

You can also choose

Unlimited weapons by clicking

Realism Options on the Options tab. This feature is handy

while you’re learning--once you get to be a better shot,

you might want to change this setting to a more realistic

level. You can use four types of weapons to battle the

enemy:

- Guns are used for attacking other aircraft and for

stra ng ground targets, including parked aircraft and

“soft-skinned” vehicles.

- Cannon pack a heavier punch and have less range

than guns, but they are used for the same purposes:

air-to-air combat and stra ng. The weight and

explosive force of a cannon’s projectile makes ships

and armored vehicles, including tanks, vulnerable.

- Rockets are used in air-to-air attacks on bombers,

or against tough ground targets, including structures

and tanks.

- Bombs are used to attack bridges, ships, air elds,

tanks, and other targets.

Here are the commands you need to re your weapons.

ACTION COMMAND

Fire guns

SHIFT+SPACEBAR

Fire cannon

CTRL+SPACEBAR

/Joystick Button

2

Fire guns and cannon

SPACEBAR

/Joystick Button

1

Fire/drop ordnance

ENTER

Cycle ordnance type

BACKSPACE

Page 32

- 31 -

GROUND ATTACK PHILOSOPHY

When you y a ghter-bomber for close air support,

stay in a looser formation. And when you return to

base after escort or ghter-bomber missions, spend your

remaining ammo on trains, convoys, air elds, and other

targets of opportunity. Whenever you’re close to the

ground, watch for small arms re--the ratio of losses

for ground attack compared to aerial combat is about ve

to one.

You need to perfect your ground attack techniques-your ground troops are depending on you! During close air

support missions, you’re often going to be down in the

heat, smoke, and debris that ground forces eat and you’d

better get used to it. Your ability to see targets and

deliver ordnance ahead of your own forces can pave the

way for your advancing ground units. By taking advantage

of “targets of opportunity,” you can set the enemy’s

ghting forces back considerably, and by attacking rail

and shipping, you can disrupt their supply of materiel.

Allied and Axis forces use a number of middle- and

low-level ground attack techniques. When coordinating

with ground troops or tank columns, a controller on the

ground, in a tank, or in a spotter plane directs the

attacking aircraft to their targets. Fighter-bombers or

medium bombers sweep in to knock out the opposition so

the ground units can advance.

Depending on the situation and the resistance

expected, the attacking force assembles in different

formations. At mid-level altitudes, the aircraft in your

squadron should form up close to concentrate their bombs

on the target. Intense antiaircraft re, however, dictates

that you use a loose formation in level ight and then

switch to a tighter formation during the short run over

the target.

Page 33

CAA-NRC COMMITTEE ON SELECTION AND

TRAINING OF AIRCRAFT PILOTS, 1942

Know your airplane

Every aircraft has strengths and weaknesses. Make

sure you know yours and those of the enemy aircraft you’re

most likely to encounter. Knowing you can out climb, out

accelerate, outturn, or outgun your foe changes the way

you y. So does knowing your own plane’s vulnerabilities.

For plane specs, see “Aircraft” in the

handbook.

Keep your head on a swivel

Visualizing the positions and movements of fastmoving objects in a three-dimensional space is difcult.

But it’s what separates ghter pilots from ghter aces.

Being a good shot is a useless skill if you can’t keep

track of the enemy. (In Combat Flight Simulator, you

can use joystick and keyboard commands to scan the sky

rapidly. To learn more, see “Using Views” earlier in this

handbook.)

Use the element of surprise

When you come in from behind or below the enemy

he can’t see you; dropping in from above gives you the

potential for greater speed. While you’re closing in,

use the enemy’s blind spots to your advantage. Come out

of the sun or the clouds with your guns blazing so you

can shoot him down before he even knows you’re there.

Stay one move ahead of the enemy

A good ghter pilot’s actions in the present are

dictated by his prediction of the future. If you merely

react to your opponent’s actions you will be shot down.

If you anticipate his actions and respond intuitively

without hesitation, you will emerge the victor.

Machines of War

Trade altitude and airspeed

Are you ying too fast? Pull back on the stick and

you’ll slow down as you climb. Be careful though: pulling

up to shake the enemy off your tail is a dangerous move!

Your airspeed will drop quickly, and a slow ship under

re is a sitting duck.

Are you ying too slowly? Nose your ship over into a

dive to gain some airspeed. Trading altitude and airspeed

is an essential part of all aerial combat maneuvers.

Fly slower to turn faster

When you ride a bicycle around a corner quickly you

want to go fast, but not too fast--it’s the same with

your aircraft. At fast speeds, centrifugal force causes

the plane’s turn radius to increase and its turn rate

to decrease. Every ship has a speed at which maximumperformance turns are possible. In general, though, a

slower-ying aircraft will outturn a faster-ying one.

Turn into your opponent

Turning into the enemy’s direction of movement

increases the angle between your movement and his guns,

making you harder to hit. Turning away decreases the

angle, making you an easier target--and making it much

easier for him to get on your tail.

Use deection shooting

Attacking an enemy aircraft from in front or behind

is easy. Just aim and shoot when you’re close enough

to hit the target. Attacking from other angles is more

complicated. You must coordinate your shooting with your

speed, and re ahead of the target so that he runs into

your bullets. This difcult skill is called “deection

shooting,” and it is the mark of a good combat pilot.

Learning it is essential to your success.

- 32 -

Page 34

Don’t shoot until he lls your windscreen

Wait until you’re so close that you’re sure you’ll

hit him--you’ll save ammunition. This strategy takes

less concentration than deection shooting, but it isn’t

always practical--especially if you’re meeting the enemy

head on!

Never stop an attack once you’ve initiated it

If you run away when you’re within range of the

enemy, it’s easier for him to get a shot at you. Courage

is not the absence of fear; it’s action in the face of

fear. If you’ve decided to attack, be courageous and

follow through. Cowardice at close range will get you

killed.

THE FIVE STAGES OF AERIAL COMBAT

1. Detecting

Find the enemy before he nds you, so that you

have the advantage of surprise. Most pilots who

are shot down never see their attackers.

2. Closing

Once you’ve detected the enemy, move into a

position close enough to shoot him down--without

being discovered.

3. Attacking

When you’re close enough to shoot the enemy,

commence the attack. If you re too soon you’ll

waste ammunition, and he might see you coming.

Remember: your weapons don’t move. To aim, you

must move your entire plane and use a deection

angle. If you fail to defeat your enemy, you’ll

need to maneuver.

4. Maneuvering

Dogghting is a test of skill in which each

opponent tries to get into a position to re.

Maneuvering means dogghting. Many novice combat

pilots think that dogghting is the way all aerial

combat occurs, but combat veterans will tell you

that dogghting should be avoided if possible.

If you’re successful at detecting, closing in

on, and attacking your enemy, you won’t need to

dogght with him. You should maneuver when any of

the following occurs after the attack:

- Neither side has gained an advantage during

detection.

- The enemy sees and successfully evades during your

closing.

- Your attack fails to down the enemy aircraft.

5. Disengaging

Disengaging means putting space between you and

the enemy so you’re out of the ght. You can

disengage on purpose or by accident. Be careful

though: just because you want to leave doesn’t

mean the ght will end.

- 33 -

Page 35

AIR-TO-AIR COMBAT STRATEGIES

Forget about the old “knights of the air” mythology.

In air-to-air combat, it’s fast, dirty work that is often

over in seconds. The loser has usually lost before they

knew what hit them. You must gain the dominant position

above and behind the enemy through surprise or by the use

of maneuvers.

General tactics

1. In the rst pass, it is usually best to make an

overhead attack from behind. In a situation where

you are able to make an overhead attack from

behind, but instead carry out an overhead attack

from the front, maneuvering for the second pass

will be comparatively difcult and you may end

up in a disadvantageous position. Furthermore,

if your altitude is insufcient, it is best to

pursue from the lower rear rather than head-on.

2. In close combat, achieve mastery of those tactics

which are your own strong points. After gradually

reaching prociency, you will discover your own

characteristics in battle. When you ght with your

favorite tactics, victory will be easy. When you

become aware of these tactics, study and master

them at once. When in battle, it is important

to entice the enemy into your favorite battle

tactics, and make them ght on your terms.

3. When you are suddenly head-on with the enemy, plan

to be resolute in the attack. Never abandon the

line of re too soon to start maneuvering for the

second pass. (In the training period, for safety’s

sake do not execute a head-on attack.)

4. During air combat it is essential to maintain

altitude. However, do not mindlessly concentrate

on the altitude, thereby making essential

maneuvers impossible because your airspeed

has dramatically dropped during a climb. It

is particularly important to pay attention to

selecting the opportune time to make changes of

altitude and speed while approaching the enemy.

5. Air combat is generally easy against an enemy

who is ghting and losing altitude. The enemy

who ghts while maintaining his altitude by skill

in maneuvering at lower speed is formidable.

(In a rough and tumble ght it is essential to

maintain all your speed.) When you advance on a

second enemy or when you go to the aid of an ally,

keep in mind the fact that altitude is better than

a stout heart.

- 34 -

Page 36

Counter-attack

When you have been attacked by the enemy plane,

unless the performance of the enemy plane is inferior

or the pilot’s ability very poor, it is difcult to regain

your position in one counter-attack. However, always try

to regain your position while continuing your counterattacks.

Disrupt the enemy’s ring line as much as you can by

diving. After avoiding their rst pass, maneuver so that

you will be under the enemy.

As soon as the enemy plane starts his run, start a

steep dive immediately and cause the enemy’s ring angle

to be depressed. The enemy will break off the attack

because his speed is excessive and ring is difcult;

as soon as you see him pulling out, turn toward him and

maneuver so that you are in pursuit.

When you nd yourself under attack, use the following

formulas for counter-attack:

- Against the overhead attack from behind. When the

enemy tries to make a run at you, gun your engine and

avoid the line of re by turns or abrupt maneuvers

just before the approaching enemy reaches effective

distance, and strive to regain gradually the

advantage.

- Against the belly attack from behind. Though you

can counter-attack by means of a slanting loop, you

are often a good target for a long period when in a

climbing position, so twist away as soon as possible.

- Against a belly attack from the front. By utilizing

maximum climbing power, seize the dominant position

above the enemy and counter-attack with an overhead

attack from behind.

When you have tried to counter-attack and have been

unsuccessful because of the enemy’s maneuvering skill, or

when as in training, ideal counter-attacks cannot be made

because of their danger, it is important that you hang

on, and strive with your utmost to regain the advantage

while keeping the enemy from attacking, and then make a

sound counter-attack.

- 35 -

Page 37

COMING IN UNDER THE ENEMY

When there is a large altitude difference, make

attack impossible by climbing; take a position beneath

the enemy (almost directly below), and match your ight

pattern with the enemy’s ight. By following the enemy’s

maneuvers you can ordinarily make it impossible for the

enemy to half-roll and attack, and you can recover the

altitude difference gradually. When the enemy turns,

maneuver by ying somewhat to his outside so that

he cannot see you. You can also recover the altitude

difference by heading the same way.

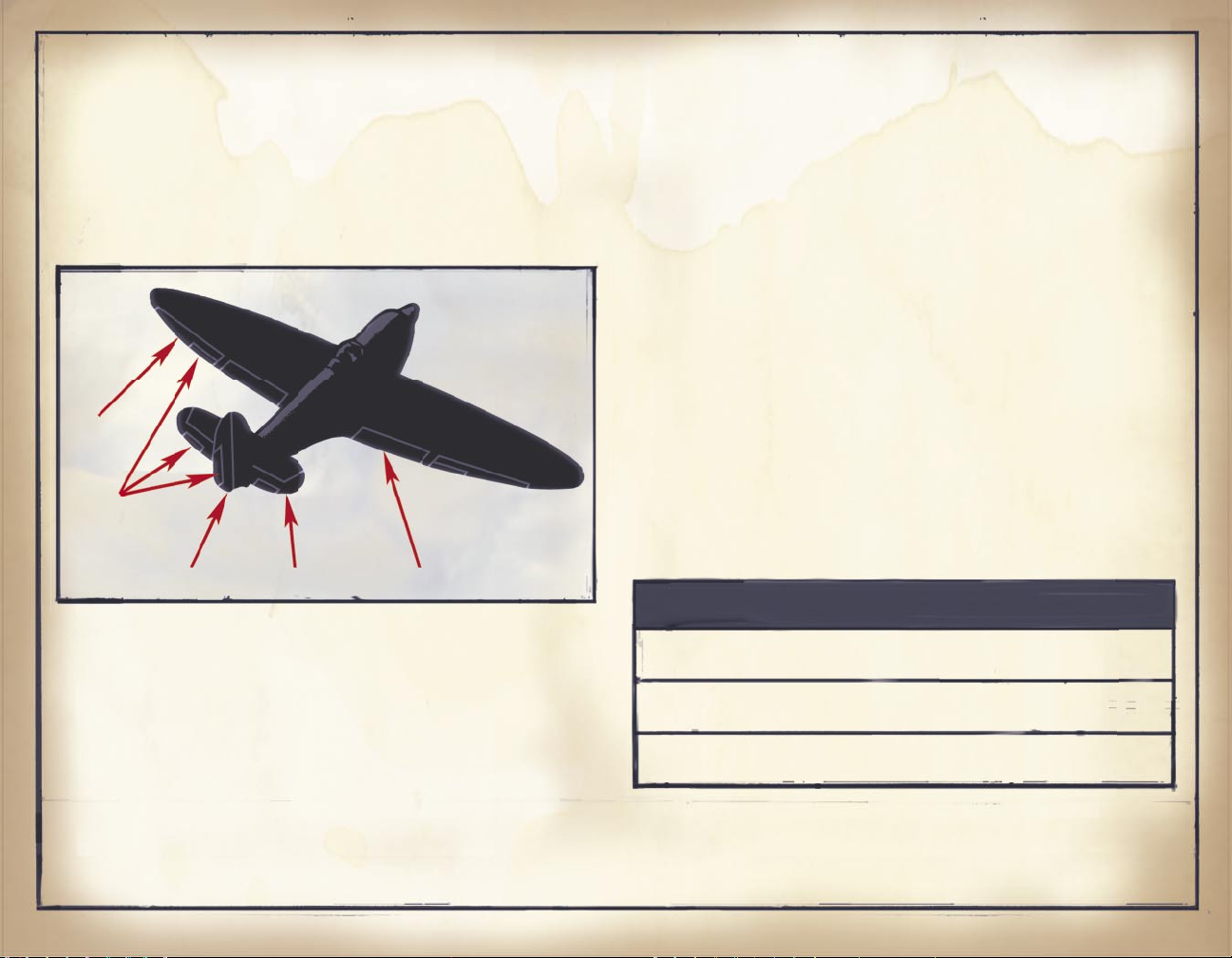

Important: If you’re attacking bombers, be very aware of where their

gunners are. The gunners are positioned to protect the bomber

against attacks from any side.

Measures to take when you are being closely pursued

1. First, always have as your principal object the

avoidance of the line of re, and by the use of

your total capacities and abilities strive to

extend the interval between the planes gradually.

In this situation, straight-line maneuvers should

be absolutely avoided!

2. Ordinary aerobatics will have little effect.

By making particularly good use of the rudder,

maneuver exaggeratedly and confuse the enemy.

3. Even if you gradually extend the interval,

consider the turning radius and do not plan to

pursue until the situation is such that an even

battle can be expected from the start.

4. Remember, if you are getting hit, whatever you

are doing is wrong. Do something radical and do

it fast! It can’t make things worse.

Level dogghting

In this type of battle particularly, incomplete

turning maneuvers have a fatal consequence. The plane,

which must be perfectly controlled while it turns

continuously, will step-by-step close in on the enemy

and nally be able to seize the dominant position. If

you learn the following tips, you can follow through

to success:

- Keep in mind that although you have been pounced

upon from somewhere to the rear, you will never be

red upon when the sights and eyes of the enemy are

not aligned. When an enemy is behind you but to one

side or the other in a level dogght always turn

toward your enemy, even though that brings you in

front of his guns. If you turn toward him, you give

him the most difcult possible shot and increase

the chance he will overshoot. If you turn away from

him, you give him the perfect opportunity to fall

in behind you for an easy shot.

- When you are about to shift to vertical dogghting

from level dogghting, lower the plane’s nose slowly,

accelerate, and maintain your turn. When the enemy

plane follows and starts to dive, still maintain your

turn, climb steeply and make a slanting loop. In case

the turns become very sharp when you are wide open,

there are many situations where you must pull back

on the control column with both hands and increase

the turning speed. In this situation, changing the

angle of inclination of the tail elevator (trim

tabs), that is, putting them at a “down” position,

generally makes piloting easier.

- During turns, aiming and ring are usually difcult,

but when you get an opportunity, shift to aiming and

shoot immediately. When it is difcult to re, shift

your attention to turning maneuvers without letting

the enemy plane escape.

- 36 -

Page 38

- 37 -

Air Force Historical

Research Agency Photo

Vertical dog ghting

Your ghting ability will be shown for what it is

in this type of combat. The so-called “ace” is often

made in this type of warfare. It is easy to get into a

disadvantageous position and lose altitude if you maneuver

clumsily and are fooled by the deceptive maneuvers of

the enemy. Keep the advantage by learning the following

strategies well enough to do in your sleep:

- When you try to shoot down the enemy plane with

one pass, do not be anxious to pursue the track of

the enemy plane too strictly. Keep in mind that the

quickest method of shooting down the enemy is to

wait for a ring opportunity by maneuvering little

by little into a superior position.

- Although it is dif cult to size up a situation

instantly, do not yield a foot when coming face

to face with the enemy.

AN UPGRADED TYPHOON WITH