Page 1

McAfee VirusScan

Anti-Virus Software

User’s Guide

Version 4.5

Page 2

COPYRIGHT

Copyright © 1995-2000 Networks Associates Technology, Inc. All Rights Reserved. No part of

this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, transcribed, stored in a retrieval system, or

translated into any language in any form or by any means without the written permission of

Networks Associates Technology, Inc., or its suppliers or affiliate companies.

TRADEMARK ATTRIBUTIONS

* ActiveHelp, Bomb Shelter, Building a World of Trust, CipherLink, Clean-Up, Cloaking, CNX,

Compass 7, CyberCop, CyberMedia, Data Security Letter, Discover, Distributed Sniffer System, Dr

Solomon’s, Enterprise Secure Cast, First Aid, ForceField, Gauntlet, GMT, GroupShield, HelpDesk,

Hunter, ISDN Tel/Scope, LM 1, LANGuru, Leading Help Desk Technology, Magic Solutions,

MagicSpy, MagicTree, Magic University, MagicWin, MagicWord, McAfee, McAfee Associates,

MoneyMagic, More Power To You, Multimedia Cloaking, NetCrypto, NetOctopus, NetRoom,

NetScan, Net Shield, NetShield, NetStalker, Net Tools, Network Associates, Network General, Network

Uptime!, NetXRay, Nuts & Bolts, PC Medic, PCNotary, PGP, PGP (Pretty Good Privacy),

PocketScope, Pop-Up, PowerTelnet, Pretty Good Privacy, PrimeSupport, RecoverKey,

RecoverKey-International, ReportMagic, RingFence, Router PM, Safe & Sound, SalesMagic,

SecureCast, Service Level Manager, ServiceMagic, Site Meter, Sniffer, SniffMaster, SniffNet, Stalker,

Statistical Information Retrieval (SIR), SupportMagic, Switch PM, TeleSniffer, TIS, TMach, TMeg,

Total Network Security, Total Network Visibility, Total Service Desk, Total Virus Defense, T-POD,

Trusted Mach, Trusted Mail, Uninstaller, Virex, Virex-PC, Virus Forum, ViruScan, VirusScan,

VShield, WebScan, WebShield, WebSniffer, WebStalker WebWall, and ZAC 2000 are registered

trademarks of Network Associates and/or its affiliates in the US and/or other countries. All

other registered and unregistered trademarks in this document are the sole property of their

respective owners.

LICENSE AGREEMENT

NOTICE TO ALL USERS: FOR THE SPECIFIC TERMS OF YOUR LICENSE TO USE THE

SOFTWARE THAT THIS DOCUMENTATION DESCRIBES, CONSULT THE README.1ST,

LICENSE.TXT, OR OTHER LICENSE DOCUMENT THAT ACCOMPANIES YOUR

SOFTWARE, EITHER AS A TEXT FILE OR AS PART OF THE SOFTWARE PACKAGING. IF

YOU DO NOT AGREE TO ALL OF THE TERMS SET FORTH THEREIN, DO NOT INSTALL

THE SOFTWARE. IF APPLICABLE, YOU MAY RETURN THE PRODUCT TO THE PLACE OF

PURCHASE FOR A FULL REFUND.

Issued March 2000/VirusScan v4.5.0

Page 3

Table of Contents

Preface . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ix

What happened? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ix

Why worry? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ix

Where do viruses come from? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .x

Virus prehistory . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .x

Viruses and the PC revolution . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . xi

On the frontier . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . xiv

Where next? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . xvi

How to protect yourself . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .xvii

How to contact McAfee and Network Associates . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . xviii

Customer service . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . xviii

Technical support . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . xix

Download support . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .xx

Network Associates training . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .xx

Comments and feedback . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .xx

Reporting new items for anti-virus data file updates . . . . . . . . . . . . . . xxi

International contact information . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .xxii

Chapter 1. About VirusScan Software . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

Introducing VirusScan anti-virus software . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .25

How does VirusScan software work? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .27

What comes with VirusScan software? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .29

What’s new in this release? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .33

Chapter 2. Installing VirusScan Software . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

Before you begin . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .37

System requirements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .37

Other recommendations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .37

Preparing to install VirusScan software . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .38

Installation options . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .38

Installation steps . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .39

Using the Emergency Disk Creation utility . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .51

Determining when you must restart your computer . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .56

User’s Guide iii

Page 4

Table of Contents

Testing your installation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .57

Modifying or removing your VirusScan installation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .58

Chapter 3. Removing Infections From Your System . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61

If you suspect you have a virus... . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .61

Deciding when to scan for viruses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .64

Recognizing when you don’t have a virus . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .65

Understanding false detections . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .66

Responding to viruses or malicious software . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .67

Submitting a virus sample . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .78

Using the SendVirus utility to submit a file sample . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .78

Capturing boot sector, file-infecting, and macro viruses . . . . . . . . . . . .81

Chapter 4. Using the VShield Scanner . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 87

What does the VShield scanner do? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .87

Why use the VShield scanner? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .88

Browser and e-mail client support . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .89

Enabling or starting the VShield scanner . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .90

Using the VShield configuration wizard . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .95

Setting VShield scanner properties . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .99

Using the VShield shortcut menu . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .155

Disabling or stopping the VShield scanner . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .155

Tracking VShield software status information . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .161

Chapter 5. Using the VirusScan application . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 163

What is the VirusScan application? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .163

Why use the VirusScan application? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .164

Starting the VirusScan application . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .165

Configuring the VirusScan Classic interface . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .171

Configuring the VirusScan Advanced interface . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .176

Chapter 6. Creating and Configuring Scheduled Tasks . . . . . . . . . . . . 193

What does VirusScan Console do? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .193

Why schedule scan operations? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .193

Starting the VirusScan Console . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .194

iv McAfee VirusScan Anti-Virus Software

Page 5

Table of Contents

Using the Console window . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .196

Working with default tasks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .198

Working with the VShield task . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .200

Working with the AutoUpgrade and AutoUpdate tasks . . . . . . . . . . . .201

Creating new tasks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .202

Enabling tasks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .206

Checking task status . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .208

Configuring VirusScan application options . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .210

Chapter 7. Updating and Upgrading VirusScan Software . . . . . . . . . . 229

Developing an updating strategy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .229

Update and upgrade methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .230

Understanding the AutoUpdate utility . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .232

Configuring the AutoUpdate Utility . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .233

Understanding the AutoUpgrade utility . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .242

Configuring the AutoUpgrade utility . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .243

Using the AutoUpgrade and SuperDAT utilities together . . . . . . . . . .252

Chapter 8. Using Specialized Scanning Tools . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 255

Scanning Microsoft Exchange and Outlook mail . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .255

When and why you should use the E-Mail Scan extension . . . . . . . . .255

Using the E-Mail Scan extension . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .256

Configuring the E-Mail Scan extension . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .257

Scanning cc:Mail . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .271

Using the ScreenScan utility . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .271

Chapter 9. Using VirusScan Utilities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 279

Understanding the VirusScan control panel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .279

Opening the VirusScan control panel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .279

Choosing VirusScan control panel options . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .280

Using the Alert Manager Client Configuration utility . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .283

VirusScan software as an Alert Manager client . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .284

Configuring the Alert Manager client utility . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .284

User’s Guide v

Page 6

Table of Contents

Appendix A. Default Vulnerable and Compressed File Extensions . . 289

Adding file name extensions for scanning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .289

Current list of vulnerable file name extensions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .290

Current list of compressed files scanned . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .294

Appendix B. Network Associates Support Services . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 297

Adding value to your McAfee product . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .297

PrimeSupport options for corporate customers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .297

Ordering a corporate PrimeSupport plan . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .300

PrimeSupport options for home users . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .302

How to reach international home user support . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .304

Ordering a PrimeSupport plan for home users . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .304

Network Associates consulting and training . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .305

Professional Services . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .305

Total Education Services . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .306

Appendix C. Using the SecureCast Service to Get New Data Files . . 307

Introducing the SecureCast service . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .307

Why should I update my data files? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .308

Which data files does the SecureCast service deliver? . . . . . . . . . . . .308

Installing the BackWeb client and SecureCast service . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .309

System requirements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .309

Troubleshooting the Enterprise SecureCast service . . . . . . . . . . . . . .319

Unsubscribing from the SecureCast service . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .319

Support resources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .319

SecureCast service . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .319

BackWeb client . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .320

Appendix D. Understanding iDAT Technology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .321

Understanding incremental .DAT files . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .321

How does iDAT updating work? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .322

What does McAfee post each week? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .323

Best practices . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .324

Frequently asked questions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .325

Index . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 327

vi McAfee VirusScan Anti-Virus Software

Page 7

Preface

What happened?

If you’ve ever lost important files stored on your hard disk, watched in dismay

as your computer ground to a halt only to display a prankster’s juvenile

greeting on your monitor, or found yourself having to apologize for abusive

e-mail messages you never sent, you know first-hand how computer viruses

and other harmful programs can disrupt your productivity. If you haven’t yet

suffered from a virus “infection,” count yourself lucky. But with more than

50,000 known viruses in circulation capable of attacking Windows- and

DOS-based computer systems, it really is only a matter of time before you do.

The good news is that of those thousands of circulating viruses, only a small

proportion have the means to do real damage to your data. In fact, the term

“computer virus” identifies a broad array of programs that have only one

feature in common: they “reproduce” themselves automatically by attaching

themselves to host software or disk sectors on your computer, usually without

your knowledge. Most viruses cause relatively trivial problems, ranging from

the merely annoying to the downright insignificant. Often, the primary

consequence of a virus infection is the cost you incur in time and effort to track

down the source of the infection and eradicate all of its traces.

Why worry?

So why worry about virus infections, if most attacks do little harm? The

problem is twofold. First, although relatively few viruses have destructive

effects, that fact says nothing about how widespread the malicious viruses are.

In many cases, viruses with the most debilitating effects are the hardest to

detect—the virus writer bent on causing harm will take extra steps to avoid

discovery. Second, even “benign” viruses can interfere with the normal

operation of your computer and can cause unpredictable behavior in other

software. Some viruses contain bugs, poorly written code, or other problems

severe enough to cause crashes when they run. Other times, legitimate

software has problems running when a virus has, intentionally or otherwise,

altered system parameters or other aspects of the computing environment.

Tracking down the source of resulting system freezes or crashes can drain time

and money from more productive activities.

Beyond these problems lies a problem of perception: once infected, your

computer can serve as a source of infection for other computers. If you

regularly exchange data with colleagues or customers, you could unwittingly

pass on a virus that could do more damage to your reputation or your dealings

with others than it does to your computer.

User’s Guide vii

Page 8

Preface

The threat from viruses and other malicious software is real, and it is growing

worse. Some estimates have placed the total worldwide cost in time and lost

productivity for merely detecting and cleaning virus infections at more than

$10 billion per year, a figure that doesn’t include the costs of data loss and

recovery in the wake of attacks that destroyed data.

Where do viruses come from?

As you or one of your colleagues recovers from a virus attack or hears about

new forms of malicious software appearing in commonly used programs,

you’ve probably asked yourself a number of questions about how we as

computer users got to this point. Where do viruses and other malicious

programs come from? Who writes them? Why do those who write them seek

to interrupt workflows, destroy data, or cost people the time and money

necessary to eradicate them? What can stop them?

Why did this happen to me?

It probably doesn’t console you much to hear that the programmer who wrote

the virus that erased your hard disk’s file allocation table didn’t target you or

your computer specifically. Nor will it cheer you up to learn that the virus

problem will probably always be with us. But knowing a bit about the history

of computer viruses and how they work can help you better protect yourself

against them.

Virus prehistory

Historians have identified a number of programs that incorporated features

now associated with virus software. Canadian researcher and educator Robert

M. Slade traces virus lineage back to special-purpose utilities used to reclaim

unused file space and perform other useful tasks in the earliest networked

computers. Slade reports that computer scientists at a Xerox Corporation

research facility called programs like these “worms,” a term coined after the

scientists noticed “holes” in printouts from computer memory maps that

looked as though worms had eaten them. The term survives to this day to

describe programs that make copies of themselves, but without necessarily

using host software in the process.

A strong academic tradition of computer prank playing most likely

contributed to the shift away from utility programs and toward more

malicious uses of the programming techniques found in worm software.

Computer science students, often to test their programming abilities, would

construct rogue worm programs and unleash them to “fight” against each

other, competing to see whose program could “survive” while shutting down

rivals. Those same students also found uses for worm programs in practical

jokes they played on unsuspecting colleagues.

viii McAfee VirusScan Anti-Virus Software

Page 9

Some of these students soon discovered that they could use certain features of

the host computer’s operating system to give them unauthorized access to

computer resources. Others took advantage of users who had relatively little

computer knowledge to substitute their own programs—written for their own

purposes—in place of common or innocuous utilities. These unsophisticated

users would run what they thought was their usual software only to find their

files erased, to have their account passwords stolen, or to suffer other

unpleasant consequences. Such “Trojan horse” programs or “Trojans,” so

dubbed for their metaphorical resemblance to the ancient Greek gift to the city

of Troy, remain a significant, and growing, threat to computer users today.

Viruses and the PC revolution

What we now think of as true computer viruses first appeared, according to

Robert Slade, soon after the first personal computers reached the mass market

in the early 1980s. Other researchers date the advent of virus programs to 1986,

with the appearance of the “Brain” virus. Whichever date has the better claim,

the link between the virus threat and the personal computer is not

coincidental.

Preface

The new mass distribution of computers meant that viruses could spread to

many more hosts than before, when a comparatively few, closely guarded

mainframe systems dominated the computing world from their bastions in

large corporations and universities. Nor did the individual users who bought

PCs have much use for the sophisticated security measures needed to protect

sensitive data in those environments. As further catalyst, virus writers found

it relatively easy to exploit some PC technologies to serve their own ends.

Boot-sector viruses

Early PCs, for example, “booted” or loaded their operating systems from

floppy disks. The authors of the Brain virus discovered that they could

substitute their own program for the executable code present on the boot

sector of every floppy disk formatted with Microsoft’s MS-DOS, whether or

not it included system files. Users thereby loaded the virus into memory every

time they started their computers with any formatted disk in their floppy

drives. Once in memory, a virus can copy itself to boot sectors on other floppy

or hard disks. Those who unintentionally loaded Brain from an infected

floppy found themselves reading an ersatz “advertisement” for a computer

consulting company in Pakistan.

With that advertisement, Brain pioneered another characteristic feature of

modern viruses: the payload. The payload is the prank or malicious behavior

that, if triggered, causes effects that range from annoying messages to data

destruction. It’s the virus characteristic that draws the most attention—many

virus authors now write their viruses specifically to deliver their payloads to

as many computers as possible.

User’s Guide ix

Page 10

Preface

For a time, sophisticated descendants of this first boot-sector virus represented

the most serious virus threat to computer users. Variants of boot sector viruses

also infect the Master Boot Record (MBR), which stores the partition

information your computer needs to figure out where to find each of your

hard disk partitions and the boot sector itself.

Realistically, nearly every step in the boot process, from reading the MBR to

loading the operating system, is vulnerable to virus sabotage. Some of the

most tenacious and destructive viruses still include the ability to infect your

computer’s boot sector or MBR among their repertoire of tricks. Among other

advantages, loading at boot time can give a virus a chance to do its work before

your anti-virus software has a chance to run. Many McAfee anti-virus

products anticipate this possibility by allowing you to create an emergency

disk you can use to boot your computer and remove infections.

But most boot sector and MBR viruses had a particular weakness: they spread

by means of floppy disks or other removable media, riding concealed in that

first track of disk space. As fewer users exchanged floppy disks and as

software distribution came to rely on other media, such as CD-ROMs and

direct downloading from the Internet, other virus types eclipsed the boot

sector threat. But it’s far from gone—many later-generation viruses routinely

incorporate functions that infect your hard disk boot sector or MBR, even if

they use other methods as their primary means of transmission.

Those same viruses have also benefitted from several generations of evolution,

and therefore incorporate much more sophisticated infection and concealment

techniques that make it far from simple to detect them, even when they hide

in relatively predictable places.

File infector viruses

At about the same time as the authors of the Brain virus found vulnerabilities

in the DOS boot sector, other virus writers found out how to use other

software to help replicate their creations. An early example of this type of virus

showed up in computers at Lehigh University in Pennsylvania. The virus

infected part of the DOS command interpreter COMMAND.COM, which it

used to load itself into memory. Once there, it spread to other uninfected

COMMAND.COM files each time a user entered any standard DOS command

that involved disk access. This limited its spread to floppy disks that

contained, usually, a full operating system.

Later viruses quickly overcame this limitation, sometimes with fairly clever

programming. Virus writers might, for instance, have their virus add its code

to the beginning of an executable file, so that when users start a program, the

virus code executes immediately, then transfers control back to the legitimate

software, which runs as though nothing unusual has happened. Once it

activates, the virus “hooks” or “traps” requests that legitimate software makes

to the operating system and substitutes its own responses.

x McAfee VirusScan Anti-Virus Software

Page 11

Preface

Particularly clever viruses can even subvert attempts to clear them from

memory by trapping the CTRL+ALT+DEL keyboard sequence for a warm

reboot, then faking a restart. Sometimes the only outward indication that

anything on your system is amiss—before any payload detonates, that

is—might be a small change in the file size of infected legitimate software.

Stealth, mutation, encryption, and polymorphic techniques

Unobtrusive as they might be, changes in file size and other scant evidence of

a virus infection usually gives most anti-virus software enough of a scent to

locate and remove the offending code. One of the virus writer’s principal

challenges, therefore, is to find ways to hide his or her handiwork. The earliest

disguises were a mixture of innovative programming and obvious giveaways.

The Brain virus, for instance, redirected requests to see a disk’s boot sector

away from the actual location of the infected sector to the new location of the

boot files, which the virus had moved. This “stealth” capability enabled this

and other viruses to hide from conventional search techniques.

Because viruses needed to avoid continuously reinfecting host systems—

doing so would quickly balloon an infected file’s size to easily detectable

proportions or would consume enough system resources to point to an

obvious culprit—their authors also needed to tell them to leave certain files

alone. They addressed this problem by having the virus write a characteristic

byte sequence or, in 32-bit Windows operating systems, create a particular

registry key that would flag infected files with the software equivalent of a “do

not disturb” sign. Although that kept the virus from giving itself away

immediately, it opened the way for anti-virus software to use the “do not

disturb” sequence itself, along with other characteristic patterns that the virus

wrote into files it infected, to spot its “code signature.” Most anti-virus

vendors now compile and regularly update a database of virus “definitions”

that their products use to recognize those code signatures in the files they scan.

In response, virus writers found ways to conceal the code signatures. Some

viruses would “mutate” or transform their code signatures with each new

infection. Others encrypted themselves and, as a result, their code signatures,

leaving only a couple of bytes to use as a key for decryption. The most

sophisticated new viruses employed stealth, mutation and encryption to

appear in an almost undetectable variety of new forms. Finding these

“polymorphic” viruses required software engineers to develop very elaborate

programming techniques for anti-virus software.

User’s Guide xi

Page 12

Preface

Macro viruses

By 1995 or so, the virus war had come to something of a standstill. New viruses

appeared continuously, prompted in part by the availability of ready-made

virus “kits” that enabled even some non-programmers to whip up a new virus

in no time. But most existing anti-virus software easily kept pace with updates

that detected and disposed of the new virus variants, which consisted

primarily of minor tweaks to well-known templates.

But 1995 marked the emergence of the Concept virus, which added a new and

surprising twist to virus history. Before Concept, most virus researchers

thought of data files—the text, spreadsheet, or drawing documents created by

the software you use—as immune to infection. Viruses, after all, are programs

and, as such, needed to run in the same way executable software did in order

to do their damage. Data files, on the other hand, simply stored information

that you entered when you worked with your software.

That distinction melted away when Microsoft began adding macro

capabilities to Word and Excel, the flagship applications in its Office suite.

Using the stripped-down version of its Visual Basic language included with

the suite, users could create document templates that would automatically

format and add other features to documents created with Word and Excel.

Other vendors quickly followed suit with their products, either using a

variation of the same Microsoft macro language or incorporating one of their

own. Virus writers, in turn, seized the opportunity that this presented to

conceal and spread viruses in documents that you, the user, created yourself.

The exploding popularity of the Internet and of e-mail software that allowed

users to attach files to messages ensured that macro viruses would spread very

quickly and very widely. Within a year, macro viruses became the most potent

virus threat ever.

On the frontier

Even as viruses grew more sophisticated and continued to threaten the

integrity of computer systems we all had come to depend upon, still other

dangers began to emerge from an unexpected source: the World Wide Web.

Once a repository of research papers and academic treatises, the web has

transformed itself into perhaps the most versatile and adaptable medium ever

invented for communication and commerce.

Because its potential seems so vast, the web has attracted the attention and the

developmental energies of nearly every computer-related company in the

industry.

xii McAfee VirusScan Anti-Virus Software

Page 13

Convergences in the technologies that have resulted from this feverish pace of

invention have given website designers tools they can use to collect and

display information in ways never previously available. Websites soon sprang

up that could send and receive e-mail, formulate and execute queries to

databases using advanced search engines, send and receive live audio and

video, and distribute data and multimedia resources to a worldwide audience.

Much of the technology that made these features possible consisted of small,

easily downloaded programs that interact with your browser software and,

sometimes, with other software on your hard disk. This same avenue served

as an entry point into your computer system for other—less benign—

programs to use for their own purposes.

Java, ActiveX, and scripted objects

These programs, whether beneficial or harmful, come in a variety of forms.

Some are special-purpose miniature applications, or “applets,” written in Java,

a programming language first developed by Sun Microsystems. Others are

developed using ActiveX, a Microsoft technology that programmers can use

for similar purposes.

Preface

Both Java and ActiveX make extensive use of prewritten software modules, or

“objects,” that programmers can write themselves or take from existing

sources and fashion into the plug-ins, applets, device drivers and other

software needed to power the web. Java objects are called “classes,” while

ActiveX objects are called “controls.” The principle difference between them

lies in how they run on the host system. Java applets run in a Java “virtual

machine” designed to interpret Java programming and translate it into action

on the host machine, while ActiveX controls run as native Windows software

that links and passes data among other Windows programs.

The overwhelming majority of these objects are useful, even necessary, parts

of any interactive website. But despite the best efforts of Sun and Microsoft

engineers to design security measures into them, determined programmers

can use Java and ActiveX tools to plant harmful objects on websites, where

they can lurk until visitors unwittingly allow them access to vulnerable

computer systems.

Unlike viruses, harmful Java and ActiveX objects usually don’t seek to

replicate themselves. The web provides them with plenty of opportunities to

spread to target computer systems, while their small size and innocuous

nature makes it easy for them to evade detection. In fact, unless you tell your

web browser specifically to block them, Java and ActiveX objects download to

your system automatically whenever you visit a website that hosts them.

User’s Guide xiii

Page 14

Preface

Instead, harmful objects exist to deliver their equivalent of a virus payload.

Programmers have written objects, for example, that can read data from your

hard disk and send it back to the website you visited, that can “hijack” your

e-mail account and send out offensive messages in your name, or that can

watch data that passes between your computer and other computers.

Even more powerful agents have begun to appear in applications that run

directly from websites you visit. JavaScript, a scripting language with a name

similar to the unrelated Java language, first appeared in Netscape Navigator,

with its implementation of version 3.2 of the Hyper Text Markup Language

(HTML) standard. Since its introduction, JavaScript has grown tremendously

in capability and power, as have the host of other scripting technologies that

have followed it—including Microsoft VBScript and Active Server Pages,

Allaire Cold Fusion, and others. These technologies now allow software

designers to create fully realized applications that run on web servers, interact

with databases and other data sources, and directly manipulate features in the

web browser and e-mail client software running on your computer.

As with Java and ActiveX objects, significant security measures exist to

prevent malicious actions, but virus writers and security hackers have found

ways around these. Because the benefits these innovations bring to the web

generally outweigh the risks, however, most users find themselves calculating

the tradeoffs rather than shunning the technologies.

Where next?

Malicious software has even intruded into areas once thought completely out

of bounds. Users of the mIRC Internet Relay Chat client, for example, have

reported encountering viruses constructed from the mIRC scripting language.

The chat client sends script viruses as plain text, which would ordinarily

preclude them from infecting systems, but older versions of the mIRC client

software would interpret the instructions coded into the script and perform

unwanted actions on the recipient’s computer.

The vendors moved quickly to disable this capability in updated versions of

the software, but the mIRC incident illustrates the general rule that where a

way exists to exploit a software security hole, someone will find it and use it.

Late in 1999, another virus writer demonstrated this rule yet again with a

proof-of-concept virus called VBS/Bubbleboy that ran directly within the

Microsoft Outlook e-mail client by hijacking its built-in VBScript support. This

virus crossed the once-sharp line that divided plain-text e-mail messages from

the infectable attachments they carried. VBS/Bubbleboy didn’t even require

you to open the e-mail message—simply viewing it from the Outlook preview

window could infect your system.

xiv McAfee VirusScan Anti-Virus Software

Page 15

How to protect yourself

McAfee anti-virus software already gives you an important bulwark against

infection and damage to your data, but anti-virus software is only one part of

the security measures you should take to protect yourself. Anti-virus software,

moreover, is only as good as its latest update. Because as many as 200 to 300

viruses and variants appear each month, the virus definition (.DAT) files that

enable McAfee software to detect and remove viruses can get quickly

outdated. If you have not updated the files that originally came with your

software, you could risk infection from newly emerging viruses. McAfee has,

however, assembled the world’s largest and most experienced anti-virus

research staff in its Anti-Virus Emergency Response Team (AVERT)*. This

means that the files you need to combat new viruses appear as soon as—and

often before—you need them.

Most other security measures are common sense—checking disks you receive

from unknown or questionable sources, either with anti-virus software or

some kind of verification utility, is always a good idea. Malicious

programmers have gone so far as to mimic the programs you trust to guard

your computer, pasting a familiar face on software with a less-than-friendly

purpose. Neither McAfee nor any other anti-virus software, however, can

detect when someone substitutes an as-yet unidentified Trojan horse or other

malicious program for one of your favorite shareware or commercial

utilities—that is, until after the fact.

Preface

Web and Internet access poses its own risks. VirusScan* anti-virus software

gives you the ability to block dangerous web sites so that users can’t

inadvertently download malicious software from known hazards; it also

catches hostile objects that get downloaded anyway. But having a top-notch

firewall in place to protect your network and implementing other network

security measures is a necessity when unscrupulous attackers can penetrate

your network from nearly any point on the globe, whether to steal sensitive

data or implant malicious code. You should also make sure that your network

is not accessible to unauthorized users, and that you have an adequate training

program in place to teach and enforce security standards. To learn about the

origin, behavior and other characteristics of particular viruses, consult the

Virus Information Library maintained on the AVERT website.

McAfee can provide you with other powerful software in the Active Virus

Defense* (AVD) and Total Virus Defense (TVD) suites, the most

comprehensive anti-virus solutions available. Related companies within the

Network Associates family provide other technologies that also help to protect

your network, including the PGP Security CyberCop product line, and the

Sniffer Technologies network monitoring product suite. Contact your

Network Associates representative, or visit the Network Associates website,

to find out how to enlist the power of these security solutions on your side.

User’s Guide xv

Page 16

Preface

How to contact McAfee and Network Associates

Customer service

On December 1, 1997, McAfee Associates merged with Network General

Corporation, Pretty Good Privacy, Inc., and Helix Software, Inc. to form

Network Associates, Inc. The combined Company subsequently acquired Dr

Solomon’s Software, Trusted Information Systems, Magic Solutions, and

CyberMedia, Inc.

A January 2000 company reorganization formed four independent business

units, each concerned with a particular product line. These are:

• Magic Solutions. This division supplies the Total Service desk product line

and related products

• McAfee. This division provides the Active Virus Defense product suite

and related anti-virus software solutions to corporate and retail customers.

• PGP Security. This division provides award-winning encryption and

security solutions, including the PGP data security and encryption product

line, the Gauntlet firewall product line, the WebShield E-ppliance

hardware line, and the CyberCop Scanner and Monitor product series.

• Sniffer Technologies. This division supplies the industry-leading Sniffer

network monitoring, reporting, and analysis utility and related software.

Network Associates continues to market and support the product lines from

each of the new independent business units. You may direct all questions,

comments, or requests concerning the software you purchased, your

registration status, or similar issues to the Network Associates Customer

Service department at the following address:

Network Associates Customer Service

4099 McEwan, Suite 500

Dallas, Texas 75244

U.S.A.

The department's hours of operation are 8:00 a.m. and 8:00 p.m. Central time,

Monday through Friday

Other contact information for corporate-licensed customers:

Phone: (972) 308-9960

Fax: (972) 619-7485 (24-hour, Group III fax)

E-Mail: services_corporate_division@nai.com

Web: http://www.nai.com

xvi McAfee VirusScan Anti-Virus Software

Page 17

Other contact information for retail-licensed customers:

Phone: (972) 308-9960

Fax: (972) 619-7485 (24-hour, Group III fax)

E-Mail: cust_care@nai.com

Web: http://www.mcafee.com/

Technical support

McAfee and Network Associates are famous for their dedication to customer

satisfaction. The companies have continued this tradition by making their sites

on the World Wide Web valuable resources for answers to technical support

issues. McAfee encourages you to make this your first stop for answers to

frequently asked questions, for updates to McAfee and Network Associates

software, and for access to news and virus information

World Wide Web http://www.nai.com/asp_set/services/technical_support

Preface

.

/tech_intro.asp

If you do not find what you need or do not have web access, try one of our

automated services.

Internet techsupport@mcafee.com

CompuServe GO NAI

America Online keyword MCAFEE

If the automated services do not have the answers you need, contact Network

Associates at one of the following numbers Monday through Friday between

8:00

A.M. and 8:00 P.M. Central time to find out about Network Associates

technical support plans.

For corporate-licensed customers:

Phone (972) 308-9960

Fax (972) 619-7845

For retail-licensed customers:

Phone (972) 855-7044

Fax (972) 619-7845

This guide includes a summary of the PrimeSupport plans available to

McAfee customers. To learn more about plan features and other details, see

Appendix B, “Network Associates Support Services.”

User’s Guide xvii

Page 18

Preface

To provide the answers you need quickly and efficiently, the Network

Associates technical support staff needs some information about your

computer and your software. Please include this information in your

correspondence:

• Product name and version number

• Computer brand and model

• Any additional hardware or peripherals connected to your computer

• Operating system type and version numbers

• Network type and version, if applicable

• Contents of your AUTOEXEC.BAT, CONFIG.SYS, and system LOGIN

script

• Specific steps to reproduce the problem

Download support

To get help with navigating or downloading files from the Network Associates

or McAfee websites or FTP sites, call:

Corporate customers (801) 492-2650

Retail customers (801) 492-2600

Network Associates training

For information about scheduling on-site training for any McAfee or Network

Associates product, call Network Associates Customer Service at:

(972) 308-9960.

Comments and feedback

McAfee appreciates your comments and reserves the right to use any

information you supply in any way it believes appropriate without incurring

any obligation whatsoever. Please address your comments about McAfee

anti-virus product documentation to: McAfee, 20460 NW Von Neumann,

Beaverton, OR 97006-6942, U.S.A. You can also send faxed comments to

(503) 466-9671 or e-mail to tvd_documentation@nai.com.

xviii McAfee VirusScan Anti-Virus Software

Page 19

Reporting new items for anti-virus data file updates

McAfee anti-virus software offers you the best available detection and

removal capabilities, including advanced heuristic scanning that can detect

new and unnamed viruses as they emerge. Occasionally, however, an entirely

new type of virus that is not a variation on an older type can appear on your

system and escape detection.

Because McAfee researchers are committed to providing you with effective

and up-to-date tools you can use to protect your system, please tell them about

any new Java classes, ActiveX controls, dangerous websites, or viruses that

your software does not now detect. Note that McAfee reserves the right to use

any information you supply as it deems appropriate, without incurring any

obligations whatsoever. Send your questions or virus samples to:

virus_research@nai.com Use this address to send questions or

virus samples to our North America

and South America offices

Preface

vsample@nai.com Use this address to send questions or

virus samples gathered with Dr

Solomon’s Anti-Virus Toolkit* software

to our offices in the United Kingdom

To report items to the McAfee European research office, use these e-mail

addresses:

virus_research_europe@nai.com Use this address to send questions or

virus samples to our offices in Western

Europe

virus_research_de@nai.com Use this address to send questions or

virus samples gathered with Dr

Solomon’s Anti-Virus Toolkit software

to our offices in Germany

To report items to the McAfee Asia-Pacific research office, or the office in

Japan, use one of these e-mail addresses:

virus_research_japan@nai.com Use this address to send questions or

virus samples to our offices in Japan

and East Asia

virus_research_apac@nai.com Use this address to send questions or

virus samples to our offices in Australia

and Southeast Asia

User’s Guide xix

Page 20

Preface

International contact information

To contact Network Associates outside the United States, use the addresses,

phone numbers and fax numbers below.

Network Associates

Australia

Level 1, 500 Pacific Highway

St. Leonards, NSW

Sydney, Australia 2065

Phone: 61-2-8425-4200

Fax: 61-2-9439-5166

Network Associates

Belgique

BDC Heyzel Esplanade, boîte 43

1020 Bruxelles

Belgique

Phone: 0032-2 478.10.29

Fax: 0032-2 478.66.21

Network Associates

Canada

Network Associates

Austria

Pulvermuehlstrasse 17

Linz, Austria

Postal Code A-4040

Phone: 43-732-757-244

Fax: 43-732-757-244-20

Network Associates

do Brasil

Rua Geraldo Flausino Gomez 78

Cj. - 51 Brooklin Novo - São Paulo

SP - 04575-060 - Brasil

Phone: (55 11) 5505 1009

Fax: (55 11) 5505 1006

Network Associates

People’s Republic of China

139 Main Street, Suite 201

Unionville, Ontario

Canada L3R 2G6

Phone: (905) 479-4189

Fax: (905) 479-4540

Network Associates Denmark

Lautruphoej 1-3

2750 Ballerup

Danmark

Phone: 45 70 277 277

Fax: 45 44 209 910

New Century Office Tower, Room 1557

No. 6 Southern Road Capitol Gym

Beijing

People’s Republic of China 100044

Phone: 8610-6849-2650

Fax: 8610-6849-2069

NA Network Associates Oy

Mikonkatu 9, 5. krs.

00100 Helsinki

Finland

Phone: 358 9 5270 70

Fax: 358 9 5270 7100

xx McAfee VirusScan Anti-Virus Software

Page 21

Preface

Network Associates

France S.A.

50 Rue de Londres

75008 Paris

France

Phone: 33 1 44 908 737

Fax: 33 1 45 227 554

Network Associates Hong Kong

19th Floor, Matheson Centre

3 Matheson Way

Causeway Bay

Hong Kong 63225

Phone: 852-2832-9525

Fax: 852-2832-9530

Network Associates

Deutschland GmbH

Ohmstraße 1

D-85716 Unterschleißheim

Deutschland

Phone: 49 (0)89/3707-0

Fax: 49 (0)89/3707-1199

Network Associates Srl

Centro Direzionale Summit

Palazzo D/1

Via Brescia, 28

20063 - Cernusco sul Naviglio (MI)

Italy

Phone: 39 02 92 65 01

Fax: 39 02 92 14 16 44

Network Associates Japan, Inc.

Toranomon 33 Mori Bldg.

3-8-21 Toranomon Minato-Ku

Tokyo 105-0001 Japan

Phone: 81 3 5408 0700

Fax: 81 3 5408 0780

Network Associates

de Mexico

Andres Bello No. 10, 4 Piso

4th Floor

Col. Polanco

Mexico City, Mexico D.F. 11560

Phone: (525) 282-9180

Fax: (525) 282-9183

Network Associates Latin America

1200 S. Pine Island Road, Suite 375

Plantation, Florida 33324

United States

Phone: (954) 452-1731

Fax: (954) 236-8031

Network Associates

International B.V.

Gatwickstraat 25

1043 GL Amsterdam

The Netherlands

Phone: 31 20 586 6100

Fax: 31 20 586 6101

User’s Guide xxi

Page 22

Preface

Network Associates

Portugal

Av. da Liberdade, 114

1269-046 Lisboa

Portugal

Phone: 351 1 340 4543

Fax: 351 1 340 4575

Network Associates

South East Asia

78 Shenton Way

#29-02

Singapore 079120

Phone: 65-222-7555

Fax: 65-220-7255

Net Tools Network Associates

South Africa

Bardev House, St. Andrews

Meadowbrook Lane

Epson Downs, P.O. Box 7062

Bryanston, Johannesburg

South Africa 2021

Phone: 27 11 706-1629

Fax: 27 11 706-1569

Network Associates

Spain

Orense 4, 4

a

Planta.

Edificio Trieste

28020 Madrid, Spain

Phone: 34 9141 88 500

Fax: 34 9155 61 404

Network Associates Sweden

Datavägen 3A

Box 596

S-175 26 Järfälla

Sweden

Phone: 46 (0) 8 580 88 400

Fax: 46 (0) 8 580 88 405

Network Associates

Taiwan

Suite 6, 11F, No. 188, Sec. 5

Nan King E. Rd.

Taipei, Taiwan, Republic of China

Phone: 886-2-27-474-8800

Fax: 886-2-27-635-5864

Network Associates AG

Baeulerwisenstrasse 3

8152 Glattbrugg

Switzerland

Phone: 0041 1 808 99 66

Fax: 0041 1 808 99 77

Network Associates

International Ltd.

227 Bath Road

Slough, Berkshire

SL1 5PP

United Kingdom

Phone: 44 (0)1753 217 500

Fax: 44 (0)1753 217 520

xxii McAfee VirusScan Anti-Virus Software

Page 23

1About VirusScan Software

Introducing VirusScan anti-virus software

Eighty percent of the Fortune 100—and more than 50 million users

worldwide—choose VirusScan anti-virus software to protect their computers

from the staggering range of viruses and other malicious agents that has

emerged in the last decade to invade corporate networks and cause havoc for

business users. They do so because VirusScan software offers the most

comprehensive desktop anti-virus security solution available, with features

that spot viruses, block hostile ActiveX and Java objects, identify dangerous

websites, stop infectious e-mail messages—and even root out “zombie” agents

that assist in large-scale denial-of-service attacks from across the Internet.

They do so also because they recognize how much value McAfee anti-virus

research and development brings to their fight to maintain network integrity

and service levels, ensure data security, and reduce ownership costs.

With more than 50,000 viruses and malicious agents now in circulation, the

stakes in this battle have risen considerably. Viruses and worms now have

capabilities that can cost an enterprise real money, not just in terms of lost

productivity and cleanup costs, but in direct bottom-line reductions in

revenue, as more businesses move into e-commerce and online sales, and as

virus attacks proliferate.

1

VirusScan software first honed its technological edge as one of a handful of

pioneering utilities developed to combat the earliest virus epidemics of the

personal computer age. It has developed considerably in the intervening years

to keep pace with each new subterfuge that virus writers have unleashed. As

one of the first Internet-aware anti-virus applications, it maintains its value

today as an indispensable business utility for the new electronic economy.

Now, with this release, VirusScan software adds a whole new level of

manageability and integration with other McAfee anti-virus tools.

Architectural improvements mean that each VirusScan component meshes

closely with the others, sharing data and resources for better application

response and fewer demands on your system. Full support for McAfee ePolicy

Orchestrator management software means that network administrators can

handle the details of component and task configuration, leaving you free to

concentrate on your own work. A new incremental updating technology,

meanwhile, means speedier and less bandwidth-intensive virus definition and

scan engine downloads—now the protection you need to deal with the

blindingly quick distribution rates of new-generation viruses can arrive faster

than ever before. To learn more about these features, see “What’s new in this

release?” on page 31.

User’s Guide 23

Page 24

About VirusScan Software

The new release also adds multiplatform support for Windows 95, Windows

98, Windows NT Workstation v4.0, and Windows 2000 Professional, all in a

single package with a single installer, but optimized to take advantage of the

benefits each platform offers. Windows NT Workstation v4.0 and Windows

2000 Professional users, for example, can run VirusScan software with

differing security levels that provide a range of enforcement options for

system administrators. That way, corporate anti-virus policy implementation

can vary from the relatively casual—where an administrator might lock down

a few critical settings, for example—to the very strict, with predefined settings

that users cannot change or disable at all.

At the same time, as the cornerstone product in the McAfee Active Virus

Defense and Total Virus Defense security suites, VirusScan software retains

the same core features that have made it the utility of choice for the corporate

desktop. These include a virus detection rate second to none, powerful

heuristic capabilities, Trojan horse program detection and removal, rapidresponse updating with weekly virus definition (.DAT) file releases, daily beta

.DAT releases, and EXTRA.DAT file support in crisis or outbreak situations.

Because more than 300 new viruses or malicious software agents appear each

month McAfee backs its software with a worldwide reach and 24-hour “follow

the sun” coverage from its Anti-Virus Emergency Response Team (AVERT).

Even with the rise of viruses and worms that use e-mail to spread, that flood

e-mail servers, or that infect groupware products and file servers directly, the

individual desktop remains the single largest source of infections, and is often

the most vulnerable point of entry. VirusScan software acts as a tireless

desktop sentry, guarding your system against more venerable virus threats

and against the latest threats that lurk on websites, often without the site

owner’s knowledge, or spread via e-mail, whether solicited or not.

In this environment, taking precautions to protect yourself from malicious

software is no longer a luxury, but a necessity. Consider the extent to which

you rely on the data on your computer and the time, trouble and money it

would take to replace that data if it became corrupted or unusable because of

a virus infection. Corporate anti-virus cleanup costs, by some estimates,

topped $16 billion in 1999 alone. Balance the probability of infection—and

your company’s share of the resulting costs—against the time and effort it

takes to put a few common sense security measures in place, and you can

quickly see the utility in protecting yourself.

Even if your own data is relatively unimportant to you, neglecting to guard

against viruses might mean that your computer could play unwitting host to

a virus that could spread to computers that your co-workers and colleagues

use. Checking your hard disk periodically with VirusScan software

significantly reduces your system’s vulnerability to infection and keeps you

from losing time, money and data unnecessarily.

24 McAfee VirusScan Anti-Virus Software

Page 25

How does VirusScan software work?

VirusScan software combines the anti-virus industry’s most capable scan

engine with top-notch interface enhancements that give you complete access

to that engine’s power. The VirusScan graphical user interface unifies its

specialized program components, but without sacrificing the flexibility you

need to fit the software into your computing environment. The scan engine,

meanwhile, combines the best features of technologies that McAfee and Dr

Solomon researchers developed independently for more than a decade.

Fast, accurate virus detection

The foundation for that combination is the unique development environment

that McAfee and Dr Solomon researchers constructed for the engine. That

environment includes Virtran, a specialized programming language with a

structure and “vocabulary” optimized for the particular requirements that

virus detection and removal impose. Using specific library functions from this

language, for instance, virus researchers can pinpoint those sections within a

file, a boot sector, or a master boot record that viruses tend to infect, either

because they can hide within them, or because they can hijack their execution

routines. This way, the scanner avoids having to examine the entire file for

virus code; it can instead sample the file at well defined points to look for virus

code signatures that indicate an infection.

About VirusScan Software

The development environment brings as much speed to .DAT file construction

as it does to scan engine routines. The environment provides tools researchers

can use to write “generic” definitions that identify entire virus families, and

that can easily detect the tens or hundreds of variants that make up the bulk of

new virus sightings. Continual refinements to this technique have moved

most of the hand-tooled virus definitions that used to reside in .DAT file

updates directly into the scan engine as bundles of generic routines.

Researchers can even employ a Virtran architectural feature to plug in new

engine “verbs” that, when combined with existing engine functions, can add

functionality needed to deal with new infection techniques, new variants, or

other problems that emerging viruses now pose.

This results in blazingly quick enhancements the engine’s detection

capabilities and removes the need for continuous updates that target virus

variants.

Encrypted polymorphic virus detection

Along with generic virus variant detection, the scan engine now incorporates

a generic decryption engine, a set of routines that enables VirusScan software

to track viruses that try to conceal themselves by encrypting and mutating

their code signatures. These “polymorphic” viruses are notoriously difficult to

detect, since they change their code signature each time they replicate.

User’s Guide 25

Page 26

About VirusScan Software

This meant that the simple pattern-matching method that earlier scan engine

incarnations used to find many viruses simply no longer worked, since no

constant sequence of bytes existed to detect. To respond to this threat, McAfee

researchers developed the PolyScan Decryption Engine, which locates and

analyzes the algorithm that these types of viruses use to encrypt and decrypt

themselves. It then runs this code through its paces in an emulated virtual

machine in order to understand how the viruses mutate themselves. Once it

does so, the engine can spot the “undisguised” nature of these viruses, and

thereby detect them reliably no matter how they try to hide themselves.

“Double heuristics” analysis

As a further engine enhancement, McAfee researchers have honed early

heuristic scanning technologies—originally developed to detect the

astonishing flood of macro virus variants that erupted after 1995—into a set of

precision instruments. Heuristic scanning techniques rely on the engine’s

experience with previous viruses to predict the likelihood that a suspicious file

is an as-yet unidentified or unclassified new virus.

The scan engine now incorporates ViruLogic, a heuristic technique that can

observe a program’s behavior and evaluate how closely it resembles either a

macro virus or a file-infecting virus. ViruLogic looks for virus-like behaviors

in program functions, such as covert file modifications, background calls or

invocations of e-mail clients, and other methods that viruses can use to

replicate themselves. When the number of these types of behaviors—or their

inherent quality—reaches a predetermined threshold of tolerance, the engine

fingers the program as a likely virus.

The engine also “triangulates” its evaluation by looking for program behavior

that no virus would display—prompting for some types of user input, for

example—in order to eliminate false positive detections. This double-heuristic

combination of “positive” and “negative” techniques results in an

unsurpassed detection rate with few, if any, costly misidentifications.

Wide-spectrum coverage

As malicious agents have evolved to take advantage of the instant

communication and pervasive reach of the Internet, so VirusScan software has

evolved to counter the threats they present. A computer “virus” once meant a

specific type of agent—one designed to replicate on its own and cause a

limited type of havoc on the unlucky recipient’s computer. In recent years,

however, an astounding range of malicious agents has emerged to assault

personal computer users from nearly every conceivable angle. Many of these

agents—some of the fastest-spreading worms, for instance—use updated

versions of vintage techniques to infect systems, but many others make full

use of the new opportunities that web-based scripting and application hosting

present.

26 McAfee VirusScan Anti-Virus Software

Page 27

About VirusScan Software

Still others open “back doors” into desktop systems or create security holes in

a way that closely resembles a deliberate attempt at network penetration,

rather than the more random mayhem that most viruses tend to leave in their

wakes.

The latest VirusScan software releases, as a consequence, do not simply wait

for viruses to appear on your system, they scan proactively at the source or

work to deflect hostile agents away from your system. The VShield scanner

that comes with VirusScan software has three modules that concentrate on

agents that arrive from the Internet, that spread via e-mail, or that lurk on

Internet sites. It can look for particular Java and ActiveX objects that pose a

threat, or block access to dangerous Internet sites. Meanwhile, an E-Mail Scan

extension to Microsoft Exchange e-mail clients, such as Microsoft Outlook, can

“x-ray” your mailbox on the server, looking for malicious agents before they

arrive on your desktop.

VirusScan software even protects itself against attempts to use its own

functionality against your computer. Some virus writers embed their viruses

inside documents that, in turn, they embed in other files in an attempt to evade

detection. Still others take this technique to an absurd extreme, constructing

highly recursive—and very large—compressed archive files in an attempt to

tie up the scanner as it digs through the file looking for infections. VirusScan

software accurately scans the majority of popular compressed file and archive

file formats, but it also includes logic that keeps it from getting trapped in an

endless hunt for a virus chimera.

What comes with VirusScan software?

VirusScan software consists of several components that combine one or more

related programs, each of which play a part in defending your computer

against viruses and other malicious software. The components are:

• The VirusScan application. This component gives you unmatched control

over your scanning operations. You can configure and start a scan

operation at any time—a feature known as “on-demand” scanning—

specify local and network disks as scan targets, tell the application how to

respond to any infections it finds, and see reports on its actions. You can

start with the VirusScan Classic window, a basic configuration mode, then

move to the VirusScan Advanced mode for maximum flexibility. A related

Windows shell extension lets you right-click any object on your system to

scan it. See “Using the VirusScan application” on page 161 for details.

• The VirusScan Console. This component allows you to create, configure

and run VirusScan tasks at times you specify. A “task” can include

anything from running a scan operation on a set of disks at a specific time

or interval, to running an update or upgrade operation. You can also enable

or disable the VShield scanner from the Console window.

User’s Guide 27

Page 28

About VirusScan Software

the Console comes with a preset list of tasks that ensures a minimal level of

protection for your system—you can, for example, immediately scan and

clean your C: drive or all disks on your computer. See “Creating and

Configuring Scheduled Tasks” on page 191 for details.

• The VShield scanner. This component gives you continuous anti-virus

protection from viruses that arrive on floppy disks, from your network, or

from various sources on the Internet. The VShield scanner starts when you

start your computer, and stays in memory until you shut down. A flexible

set of property pages lets you tell the scanner which parts of your system

to examine, what to look for, which parts to leave alone, and how to

respond to any infected files it finds. In addition, the scanner can alert you

when it finds a virus, and can generate reports that summarize each of its

actions.

The VShield scanner comes with three other specialized modules that

guard against hostile Java applets and ActiveX controls, that scan e-mail

messages and attachments that you receive from the Internet via Lotus

cc:Mail, Microsoft Mail or other mail clients that comply with Microsoft’s

Messaging Application Programming Interface (MAPI) standard, and that

block access to dangerous Internet sites. Secure password protection for

your configuration options prevents others from making unauthorized

changes. The same convenient dialog box controls configuration options

for all VShield modules. See “Using the VShield Scanner” on page 85 for

details.

• The E-Mail Scan extension. This component allows you to scan your

Microsoft Exchange or Outlook mailbox, or public folders to which you

have access, directly on the server. This invaluable “x-ray” peek into your

mailbox means that VirusScan software can find potential infections before

they make their way to your desktop, which can stop a Melissa-like virus

in its tracks. See “Scanning Microsoft Exchange and Outlook mail” on page

253 for details.

• A cc:Mail scanner. This component includes technology optimized for

scanning Lotus cc:Mail mailboxes that do not use the MAPI standard.

Install and use this component if your workgroup or network uses cc:Mail

v7.x or earlier. See “Choosing Detection options” on page 116 for details.

• The Alert Manager Client configuration utility. This component lets you

choose a destination for Alert Manager “events” that VirusScan software

generates when it detects a virus or takes other noteworthy actions. You

can also specify a destination directory for older-style Centralized Alerting

messages, or supplement either method with Desktop Management

Interface (DMI) alerts sent via your DMI client software. See “Using the

Alert Manager Client Configuration utility” on page 281 for details.

• The ScreenScan utility. This optional component scans your computer as

your screen saver runs during idle periods. See “Using the ScreenScan

utility” on page 269 for details.

28 McAfee VirusScan Anti-Virus Software

Page 29

About VirusScan Software

• The SendVirus utility. This component gives you an easy and painless

way to submit files that you believe are infected directly to McAfee

anti-virus researchers. A simple wizard guides you as you choose files to

submit, include contact details and, if you prefer, strip out any personal or

confidential data from document files. See “Using the SendVirus utility to

submit a file sample” on page 76 for details.

• The Emergency Disk creation utility. This essential utility helps you to

create a floppy disk that you can use to boot your computer into a

virus-free environment, then scan essential system areas to remove any

viruses that could load at startup. See “Using the Emergency Disk Creation

utility” on page 49 for details.

• Command-line scanners. This component consists of a set of full-featured

scanners you can use to run targeted scan operations from the MS-DOS

Prompt or Command Prompt windows, or from protected MS-DOS mode.

The set includes:

– SCAN.EXE, a scanner for 32-bit environments only. This is the

primary command-line interface. When you run this file, it first

checks its environment to see whether it can run by itself. If your

computer is running in 16-bit or protected mode, it will transfer

control to one of the other scanners.

– SCANPM.EXE, a scanner for 16- and 32-bit environments. This

scanner provides you with a full set of scanning options for 16- and

32-bit protected-mode DOS environments. It also includes support

for extended memory and flexible memory allocations. SCAN.EXE

will transfer control to this scanner when its specialized capabilities

can enable your scan operation to run more efficiently.

– SCAN86.EXE, a scanner for 16-bit environments only. This scanner

includes a limited set of capabilities geared to 16-bit environments.

SCAN.EXE will transfer control to this scanner if your computer is

running in 16-bit mode, but without special memory configurations.

– BOOTSCAN.EXE, a smaller, specialized scanner for use primarily

with the Emergency Disk utility. This scanner ordinarily runs from

a floppy disk you create to provide you with a virus-free boot

environment.

When you run the Emergency Disk creation wizard, VirusScan

software copies BOOTSCAN.EXE, and a specialized set of .DAT

files to a single floppy disk. BOOTSCAN.EXE will not detect or

clean macro viruses, but it will detect or clean other viruses that can

jeopardize your VirusScan software installation or infect files at

system startup. Once you identify and respond to those viruses, you

can safely run VirusScan software to clean the rest of your system.

User’s Guide 29

Page 30

About VirusScan Software

All of the command-line scanners allow you to initiate targeted scan

operations from an MS-DOS Prompt or Command Prompt window, or

from protected MS-DOS mode. Ordinarily, you’ll use the VirusScan

application’s graphical user interface (GUI) to perform most scanning

operations, but if you have trouble starting Windows or if the VirusScan

GUI components will not run in your environment, you can use the

command-line scanners as a backup.

• Documentation. VirusScan software documentation includes:

– A printed Getting Started Guide, which introduces the product,

provides installation instructions, outlines how to respond if you

suspect your computer has a virus, and provides a brief product

overview. The printed Getting Started Guide comes with the

VirusScan software copies distributed on CD-ROM discs—you can

also download it as VSC45WGS.PDF from Network Associates

website or from other electronic services.

– This user’s guide saved on the VirusScan software CD-ROM or

installed on your hard disk in Adobe Acrobat .PDF format. You can

also download it as VSC45WUG.PDF from Network Associates

website or from other electronic services. The VirusScan User’s Guide

describes in detail how to use VirusScan and includes other

information useful as background or as advanced configuration

options. Acrobat .PDF files are flexible online documents that

contain hyperlinks, outlines and other aids for easy navigation and

information retrieval.

– An administrator’s guide saved on the VirusScan software

CD-ROM or installed on your hard disk in Adobe Acrobat .PDF

format. You can also download it as VSC45WAG.PDF from

Network Associates website or from other electronic services. The

VirusScan Administrator’s Guide describes in detail how to manage

and configure VirusScan software from a local or remote desktop.

– An online help file. This file gives you quick access to a full range of

topics that describe VirusScan software. You can open this file either

by choosing Help Topics from the Help menu in the VirusScan

main window, or by clicking any of the Help buttons displayed in

VirusScan dialog boxes.

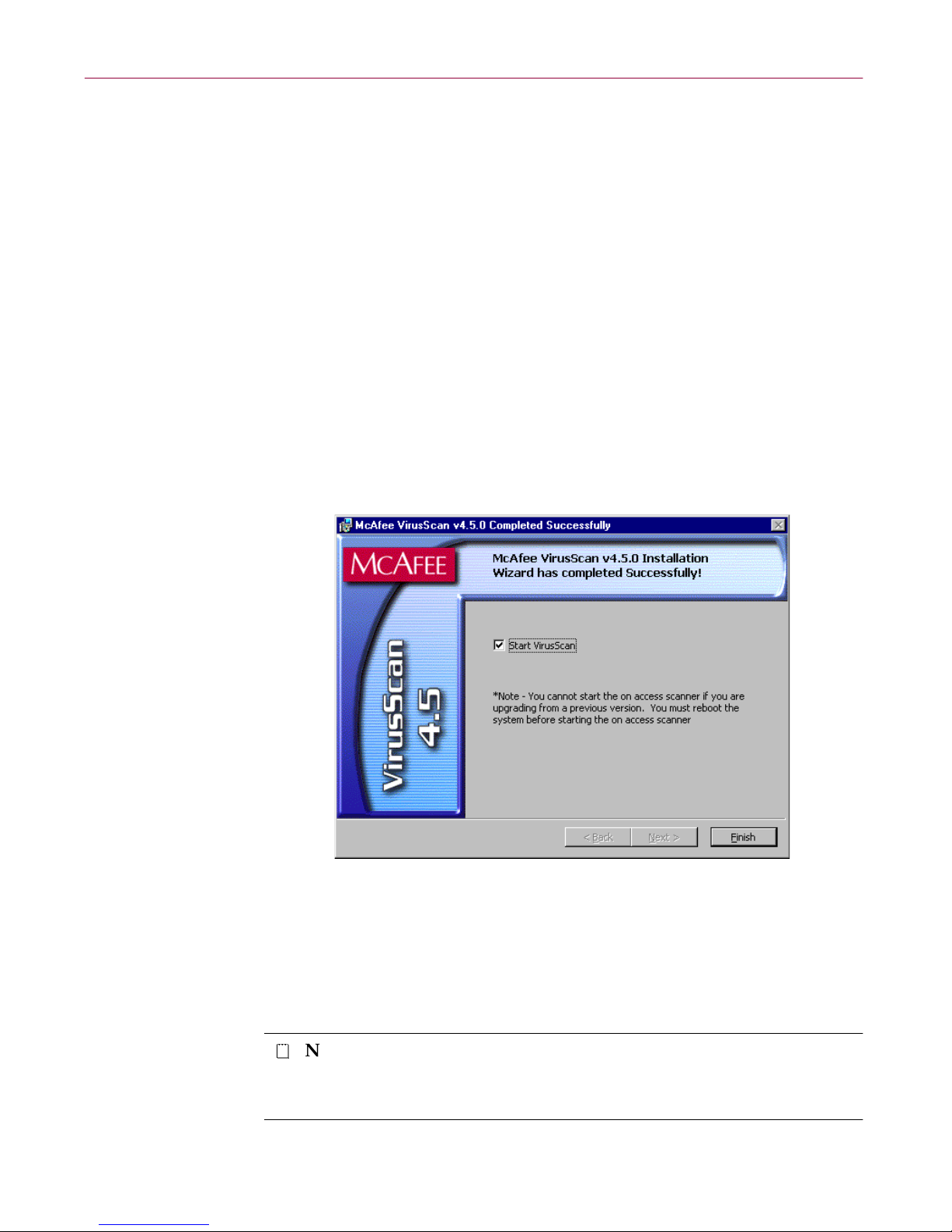

The help file also includes extensive context-sensitive—or “What's