Page 1

OWNER'S MANUAL

LANGEVINLANGEVIN

LANGEVIN

LANGEVINLANGEVIN

MINI MASSIVEMINI MASSIVE

MINI MASSIVE

MINI MASSIVEMINI MASSIVE

STEREO EQSTEREO EQ

STEREO EQ

STEREO EQSTEREO EQ

MANLEY

LABORATORIES, INC.

MANLEY LABORATORIES, INC.

13880 MAGNOLIA AVE.

CHINO, CA. 91710

TEL: (909) 627-4256

FAX: (909) 628-2482

http://www.manleylabs.com

email: emanley @ manleylabs.com

email: service @ manleylabs.com

Rev. 3/29/09 CD

Page 2

CONTENTS

SECTION PAGE

INTRODUCTION 3

BACK PANEL & CONNECTING 4

FRONT PANEL 5, 6

Designer's Notes 7-9

THE MASSIVE PASSIVE

BEGINNINGS, THE SUPER PULTEC 10

THE PASSIVE PARAMETRIC 11

WHY PASSIVE, WHY PARALLEL 12

PHASE SHIFT, WHY TUBES 13

CURVES 14 -16

TRIMS and The GUTZ 17

MAINS VOLTAGE SETTING 18

EQUALIZING

EQUALIZERS (GENERAL) 19

EQUALIZER TECHNIQUES 20 -25

TRANSLATIONS 26

TROUBLESHOOTING 27, 28

MAINS CONNECTIONS 29

SPECIFICATIONS 30

APPENDIX 1 - TEMPLATE FOR STORING SETTINGS 31

Page 3

INTRODUCTION

THANK YOU!...

for choosing the Langevin MINI MASSIVE STEREO EQUALIZER. This equalizer is based on the

Manley Massive Passive Stereo Tube EQ and might be described as an evolution and an alternative to the

original.The Massive Passive and the Mini Massive share a number of qualities. Both are based on passive

circuits comprised of resistors, capacitors and inductors to sculpt tone; the exact same circuits for the most

part. These EQ circuits substantially attenuate the signal, and gain is needed to restore signal levels to

nominal unity gain when ‘flat’ and provide the apparent EQ boosts. The Massive Passive uses mostly

tubes to provide the gain and the Mini Massive uses solid-state gain blocks. The Massive uses tubes and

transformers simply because it was designed for a certain amount of color and character. The Mini

Massive was designed to be clean and pristine and is an alternative for people wanting the magic of it's

big brother, but who generally prefer EQs that have less intrinsic color.

The Massive Passive was intended to be a brute-force EQ in the same vein as classic vintage units,

most useful on close-miked instruments needing some drastic treatment. Like many things, the users

found many applications that the designer had not expected, such as stereo buss, mastering and subtle

vocal treatments. The Mini Massive should be even better suited for these tasks for some people,

because of its basic cleanliness and more minimalist design. Of course, the best choice is maintaining

choices and options. So besides a good surgical analog parametric, a familiar vintage EQ, a few good

digital EQs, the Mini Massive holds a place in your arsenal for it's unique flavor and capabilities.

Some sections of this manual have been directly 'borrowed' from the Massive Passive manual and some

parts are fresh and only pertain to the Mini Massive. As usual, the manual is mostly just train-of-thought,

random ramblings from one engineer to another and can be read with a grain of salt or a smile.

GENERAL NOTES

LOCATION & VENTILATION

The Langevin MINI MASSIVE must be installed in a stable location with ample ventilation. It is

recommended, if this unit is rack mounted, that you allow enough clearance on the top of the unit such

that a constant flow of air can move through the ventilation holes. Airflow is primarily through the top.

You should also not mount the MINI MASSIVE where there are likely to be strong magnetic fields, such

as directly over or under power amplifiers or large power consuming devices. The other gear's fuse values

tend to give a hint of whether it draws major power and is likely to create a bigger magnetic field. Magnetic

fields might cause a hum in the EQ and occasionally you may need to experiment with placement in the

rack to eliminate the hum. In most situations the Mini Massive should be quiet and trouble free.

WATER & MOISTURE

As with any electrical equipment, this equipment should not be used near water or moisture.

SERVICING

The user should not attempt to service this unit beyond what is described in the owner's manual.

Refer all servicing to your dealer or Manley Laboratories. The factory technicians are available for

questions by phone at (909) 627-4256 or by email at <service@manleylabs.com>. Fill in your warranty

card! Check the manual - your questions are probably anticipated and answered within these pages......

3

Page 4

THE BACK PANEL

OUTPUT

7

CHANNEL 2

PIN 1 GROUND

PIN 2 HOT +

PIN 3 LOW -

N9512423

6

INPUT

IF IN DOUBT USE +4 BALANCED

& “IRON” IF OPTION IS INSTALLED

INPUT OUTPUT

TRANSFORMER

LEVELS

+4 UNBALANCED

+4

BAL

-10 UNBALANCED

5

OPTION

VINTAGE

BYPASS

IRON

MINI MASSIVE

SERIAL NUMBER

VOLTAGE

123

MANLEY LABS

13880 MAGNOLIA AVE., CHINO, CA 91710

PHONE (909) 627-4256 fax (909) 628-2482

www.manleylabs.com

FUSE 1A @ 117V

FUSE .5A @ 220V

CAUTION - RISK OF ELECTRIC SHOCK

DO NOT OPEN. REFER SERVICING TO

QUALIFIED PERSONNEL ONLY

4

OUTPUT

78

CHANNEL 1

BY MANLEY LABS

MINI-MASSIVE

TWO CHANNEL EQUALIZER

DESIGNED BY HUTCH

INPUT

6

First connect all the cables, then turn on the power, wait 30 seconds, then have fun. As if we had to tell you....

1) POWER CONNECTOR. First verify the POWER SWITCH on the front panel is off (down). Use the power cable supplied with your

Mini Massive. One end goes here and the other end goes to the wall outlet. You know all this.

2) VOLTAGE LABEL (ON SERIAL STICKER). Just check that it indicates the same voltage as is normal in your country. It should

be. If it says 120V and your country is 220V, then call your dealer up. If it says 120V and you expect 110 it should work fine.

3) FUSE. The fuse holder on this unit is part of the IEC power connector and can be accessed by flipping open the small rectangular panel.

Before attempting this be sure the power cable is removed to ensure there is no possibilty of getting shocked As to be expected, the big

hint that the fuse is blown is that there seems to be no power, no LEDs lit no matter where the switches are set, in other words, the same

symptoms as the power cable not being plugged into the wall or the Mini Massive (which should be the first thing to check). Fuses are meant

to "blow" when an electrical problem occurs and are essentially safety devices to prevent fires, shocks and big repair bills. Only replace

it if it has "blown" and only with the same value and type (1A slo-blo for 120V, .5A slo-blo for 220V). A blown fuse either looks

blackened internally or the little wire inside looks broken. Because the Mini Massive automatically goes into "hard-wire bypass" when

power is removed audio will pass through the unit even when there is a blown fuse.

4) Fuse Value. Just in case you don't read manuals (including this one obviously) we remind you of the right value of fuse to use on the

back panel. In fact, there are a few other bits of technical info on the back panel that you may refer to occasionally.

5) Input / Output Level Switch. This 3 position toggle is important to set properly. It allows you to properly interface the Mini Massive

with your studio. For most situations the default setting will be the center position, "+4 Balanced", that should work with most pro gear.

The other settings are "+4 Unbalanced" and "-10 Unbalanced". In most situations, especially with typical balanced audio gear, when this

switch is improperly set, the symptoms are subtle, with only a loss of headroom being the significant factor. If in doubt, set this switch to

the middle position and read the section on page 25 for a more complete explanation.

6) COMBO JACK INPUTS. Accepts balanced or unbalanced and XLR or 1/4 inch Tip-Sleeve or Tip-Ring-Sleeve plug sources. These

are just the Input jacks and will easily interface with most gear.

7) XLR JACK OUTPUTS. These are the basic output jacks and should easily interface with virtually any audio equipment whether

balanced or unbalanced when the appropriate setting is chosen at the Input / Output Level Switch. Pin 1 is Ground, Pin 2 is hot or + and

Pin 3 is low or -. These outputs are not the typical pseudo-balanced or cross-coupled type which automatically compensate for unbalanced

inputs but are often unstable and may significantly reduce hum rejection. These outputs maintain a constant and very balanced output

impedance regardless of loading conditions.

8) Transformer Option Switch. Switches between the output transformer options. With the switch in the lower position, the transformer

is bypassed and the output is direct coupled from the line drivers. The advantage is a wider frequency response, extending from 1 Hz to

100 kHz, and slighly lower distortion or less color. With the switch in the center position the output goes through the transformer. The

advantages include "Floating" outputs which are very forgiving when it comes to interfacing and the slightly warmer and smoother color

caused by the transformer. The transformer sound in this case is deliberately exagerated a little just because we all expect a bit of tonal

change,and in truth when this transformer is used raw the difference sonically may be too subtle to justify its inclusion, so the circuit pushes

it for extra color . The upper position of the switch further exagerates the transformer by biasing a separate winding with enough DC current

to increase the even order distortions and is intented to begin to simulate some Class A discrete British console circuits from the mid 70's.

This position may seem to increase the apparent lows especially as the user increases the low boosts on the front panel. It may be too much

for some purposes and may be most appropriate where a little less fidelity may be desired - rock guitars for example.

Maybe it might be worth pointing out to those with less time behind the soldering irons and oscilloscopes, that modern transformers tend

to be a lot more transparent than marketing suits may want you to believe (remember when "tubes make it warm" was the hype). We pointed

out that it was more like the old transformers that gave that vintage warmth and now this is the new hype. Basically, some old (and new)

transformers used cheap steel (low permeability) laminations and this caused some low freq distortions. Of course, any distortion can be

said to both be useful on some things but a disaster on other sounds. It's not platinum record magic, it's just familiar distortions. OK?

4

Page 5

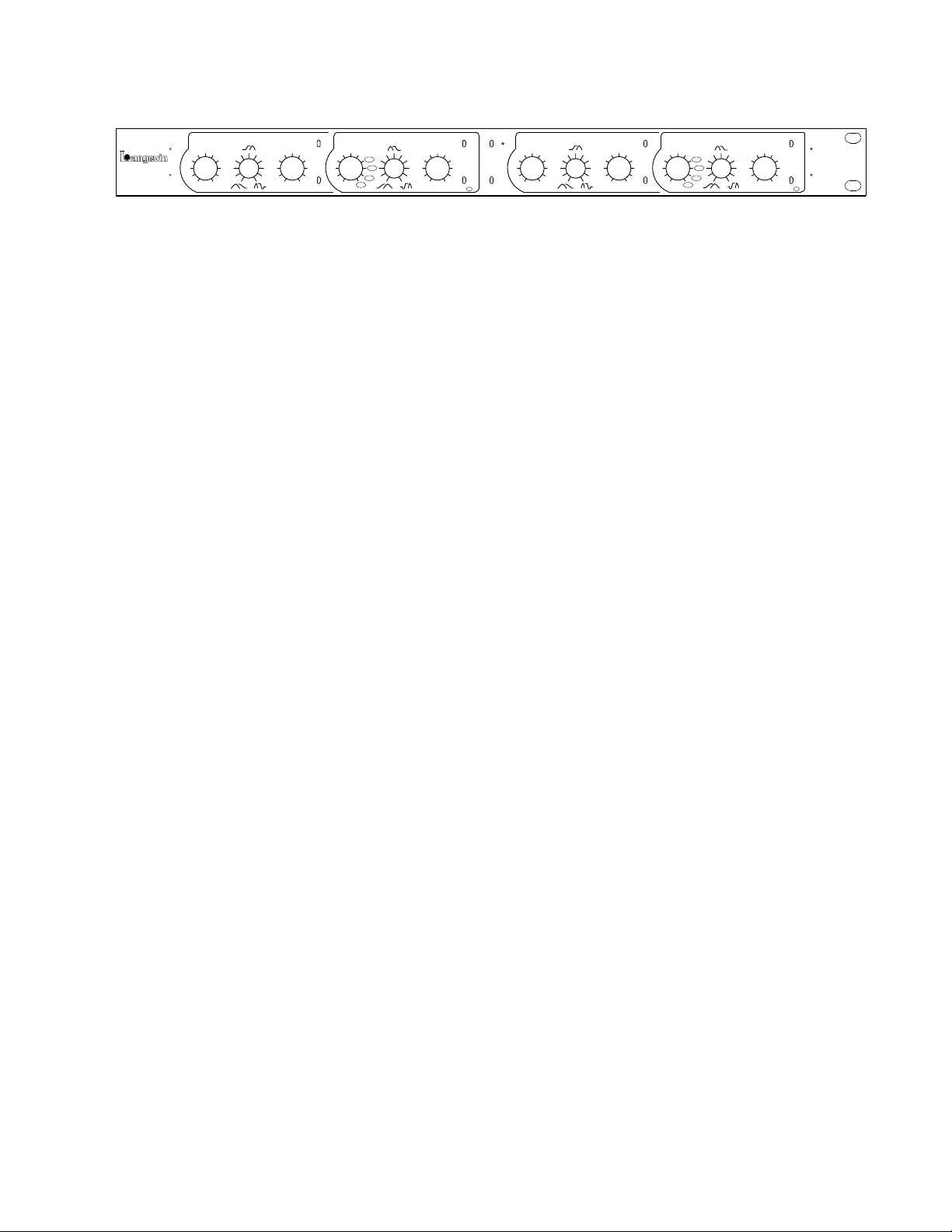

THE FRONT PANEL

233

EQ IN

BOOST

OUT

8

CUT

SHELF

BELL

P

0

20

B

BELL 2

POWER

150

100

220

68

330

47

470

33

680

1K 560

1

BY MANLEY LABS

LOW FREQUENCY EQ

68

47

33

FREQUENCY

100

22

BANDWIDTH

150

220

330

470

680

1K

HZ HZ HZ HZ

LEVEL

0820

BOOST

FREQUENCY BANDWIDTH LEVEL

OUT

2K7

CUT

1K8

1K2

SHELF

820

560

P

B

BELL

HI FREQUENCY EQ HI FREQUENCY EQLOW FREQUENCY EQ

3K9

5K6

8K2

12K

16K

27K 22

446

1) The Power Switch: First things first; flip the toggle up to turn on the Mini Massive. There is no "power LED", instead

the "Bypass" LED indicator is lit red for a few seconds as the unit warms up and stabilizes. If the "EQ IN" switch is also up,

then a few seconds later the LED changes from red to green. The Mini Massive has a "hard-wire bypass" so even when power

is off it will pass audio untouched. In fact, because this EQ is quite transparent when set flat, one of our tests is cycling power

on and off while listening for any audible change - it should be as transparent through the unit as when hardwire bypassed.

2) EQ IN toggle: This activates both sides of the EQ and is intended as a convenience feature. Of course, it is pretty easy to

bypass the two individual sections per side using the "OUT" setting (Switch#3) so one can easily use the unit as two mono

EQs. This master EQ IN switch makes auditioning and comparing the effect of the total stereo EQ extremely easy.

3) BOOST / OUT / CUT, TOGGLE. Each band has individual toggles to select whether that band will boost or cut or be

bypassed. "OUT" is a hardwire bypass for that band. Unlike most EQs, you must select boost or cut for each band. There are

several good reasons for this arrangement. First, because the boost part of the circuit is in a different place than the cut part

because it is passive, this allows us to use the same components in both sections but doing essentially opposite functions. The

conventional arrangement of a boost/zero/cut pot (baxandall) circuit was avoided to really make it passive. This switch also

allows twice the resolution of the "GAIN" pot and a much more accurate "zero". The center detent of conventional EQs is rarely

the "electrical" center of the pot so what you expect is zero is often a little EQed. This toggle allows some of us, who use dip

EQ to reduce offending frequencies to verify those frequencies in "Boost" and then switch to "Cut". Finally, it allows us to

bypass each band individually, without losing our "GAIN" pot setting rather than resetting a band to zero or bypassing the

entire EQ.

3

BOOST

FREQUENCY BANDWIDTH LEVELFREQUENCY BANDWIDTH LEVEL

OUT

8

0

20

P

B

SHELF

3K9

2K7

5K6

CUT

1K8

8K2

1K2

12K

820

16K

27K

BELL

8

0

P

B

4

3

BOOST

OUT

CUT

mini

massive

SHELF

BELL

20

BELL 2

457 6 57 6 57 6 57

4) SHELF & BELL toggle. The two lowest (leftmost) bands can each be a special Low Shelf or conventional Bell shape. The

two highest (rightmost) bands can each be a special High Shelf or conventional Bell shape. Shelf & Bell describe the EQ's

shape. We included some diagrams to help visualize these curves. Bell curves focus their boost and cut at given frequency and

the further away we get from that frequency, the less boost or cut. The bell curves on the Mini Massive are moderately wide

and the "Bandwidth Control" does not have a lot of range and it also affects the maximum boost and cut (like a Pultec). Shelf

slopes generally boost (or cut) towards the highs or lows (thus high shelves and low shelves). These are not to be confused

with "high or low filters" which purely cut above or below a given frequency. Shelves also have gain or dB controls which

allow you to just boost or cut a little bit if desired - filters never have these controls.

The High band also has a special setting labelled BELL 2 that only operates on the 4 highest frequencies. It simply narrows

the Q for those 4 highest frequencies. This can be useful for controlling the apparent air or sweetness of the extreme highs.

One may notice the ovals marked around the 4 highest freqs and a corresponding oval around the Bell 2 setting.

It is a bit of an refinement from the Massive Passive which doesn't offer that feature and which followed a more general

philosophy of maintaining very similar curve shapes across the spectrum. While the SHELF curves on both the Massive

Passive and Mini Massive are capable of good control of 'air', it seems many users missed that idea because they generally

favor bell curves and in the case of the Massive Passive the bell Q is probably too wide for great 'air' control. The Mini Massive

includes 3 features that vastly improve 'air' control. The first is this narrower Q in Bell 2, the second is reshaped curves for

the 4 highest shelf frequencies, and the third is the incredible clarity offered by the Rapture amps along with transformerless

outputs, which extents the frequency and phase response. These features were considered important for a basic 2 band stereo

EQ more aimed at mastering than the Massive Passive was, where ironically it has seen a lot of use.

Similarly, we reshaped the 4 lowest shelf curves for more fatness, depth and punch compared to the Massivo. These new curves

might be considered more Pultec-like but are not in the strictest sense. They just offer a similar usefulness and essentially

increase the range that the bandwidth control can be effectively used for those lowest freqs. It also breaks away from the

philosophy on the Massivo of maintaining similar curve shaping across the spectrum. The Mini shifts the dip aspect of the shelf

curves more towards the low mids and mids for those lowest 4 frequencies.

It may also be worth pointing out that the shelf curves that were introduced by the Massive Passive were quite unique at that

time and while there have been imitations since, these shelves are still unique, unusual and certainly unconventional compared

to most EQs and are worth exploring and learning. Let us just say that the biggest fans of the Massive are the engineers who

quickly learned the strange shelf 'features' and those who approached it as a whole new tool, and not just a standard EQ.

5

Page 6

5) GAIN. This sets the boost and/or cut depth or amount and works with the BOOST, OUT, CUT toggle. FLAT is fully counter-

clockwise not straight up "12:00" like most EQs. It is more like a Pultec in this regard. Maximum boost or cut is fully clockwise

and can be up to 20 dB - but not necessarily. There is a fair amount of interaction with the BANDWIDTH control. The maximum

of 20 dB is available in Shelf modes when the Bandwidth is CCW and is about 12 dB when the Bandwidth is CW.

The maximum of 20 dB is available in Bell modes when the Bandwidth is CW and is about 6 dB when the Bandwidth is CCW.

At straight up "12:00" in Bell mode "narrow" expect about 8 dB of boost or cut. In other words, you shouldn't expect the markings

around the knob to indicate a particular number of dBs. Many Eqs are this way. On the other hand, this interaction is the result

of natural interactions between components and tends to "feel" and sound natural as opposed to contrived.

The 2 bands will have some interaction and interdependence especially when both are set towards mid frequencies. It is a parallel

EQ rather than the far more common series connected style. If you set up all 2 bands to around 1kHz and boosed each 20 dB,

the total boost will be 20 dB rather than 40dB (20+ db of boost and 20 dB into clipping). This also implies, that if you first boost

one band, that the next will not seem to do much if it is at similar frequencies and bandwidths. Virtually all other parametrics

are both series connected and designed for minimal interaction, which seems to be quite appealing if you wear a white lab coat

with pocket protectors ;.) Actually, there are valid arguements for those goals and there are definately some applications that

require them. However, there is also a valid point for an EQ that is substantially different from the "norm", and for audio toys

that have artistic merit and purpose and not just scientific interest or gimmickry. We tried to balance artistic, technological and

practical considerations in both the Massive Passive and Mini Massive, and offer both some new and old approaches that appealed

to the ears of recording engineers (and our own ears).

6) BANDWIDTH. Similar to the "Q" control found in many EQs. A more accurate term here would be "Damping" or

"Resonance" but we used "Bandwidth" to stay with Pultec terminology and because it is a "constant bandwidth" (*) design rather

than "constant Q" and because of the way it uniquely works in both Bell and Shelf modes. In Bell modes, you will find it similar

to most Q controls with a wider shape fully CCW and narrower fully CW. The widest Q (at maximum boost) is about 1 and the

narrowest Q is about 2.5 to 3 generally. On paper, the bell widths appear to have less effect than is apparent on listening and the

sound is probably more due to "damping" or "ringing" and the way it interacts with the gain. Also some people associate a wide

bell on conventional EQs with more energy boost or cut, and at first impression the Massivo seems to work backward compared

with that and narrow bandwidths give more drastic results. On the Massive Passive a narrow bandwidth bells will allow up to

the full 20 dB of boost (or cut) and wide bandwidths significantly less at about 6 dB maximum.

In Shelf Modes the Bandwidth has a special function. When this knob is fully CCW, the shelf curves are very similar to almost

all other EQs. As you increase the Bandwidth control, you begin to introduce a bell curve in the opposite direction. So if you

have a shelf boost, you gradually add a bell dip which modifies the overall shelf shape. At straight up, it stays flatter towards the

mid range, and begins to boost further from the mids with a steeper slope but the final maximum part of the boost curve stays

relatively untouched. With the Bandwidth control fully CW, that bell dip becomes obvious and is typically 6dB down at the

frequency indicated. The boost slope is steeper and the maximum boost may be about 12 dB. These curves were modelled from

Pultec EQP1-As and largely responsible for the outrageous "phatness" they are known for. As you turn the Bandwidth knob (CW),

it seems as if the shelf curve is moving further towards the extreme frequencies, but mostly of this is just the beginning part of

the slope changing and not the peak. This also implies, that you may find yourself using frequencies closer to the mids than you

might be used to. These shelf curves have never been available for an analog high shelf before and provide some fresh options.

7) FREQUENCY. Each band provides a wide range of overlapping and interleaving frequency choices. Each switch position

is selecting a different capacitor and inductor. In fact, in SHELF mode the EQ could be deemed third order sections, which implies

3 frequency dependent components are in play, 2 capacitors and an inductor or two inductors and a capacitor. Normal shelf EQs

are first order with only one capacitor creating the EQ shape, and this shape is less steep and controllable by the user.

At extreme high and low frequencies (including 10K and 12K), you might get some unexpected results because of the Bandwidth/

Shelf function. For example, you can set up 20 dB of boost at 12K and it can sound like you just lost highs instead of boosting.

This happens when the Bandwidth control is more CW only and not when it is CCW. Why? You are creating a dip at 12K and

the shelf is only beginning at the fringes of audibility but the dip is where most of us can easily percieve. It takes a little getting

used to the way the controls interact. The reverse is also true, where you set up a shelf cut and you get a boost because of the

Bandwidth control being far CW. In some ways this simulates the shape of a resonant synthesizer filter or VCF except it doesn't

move. These weird highs are useful for raunchy guitars and are designed to work well with the Filters. There are a lot of creative

uses for these bizarre settings including messing with the minds of back-seat engineers.

6

Page 7

NOTES

1) Do not assume the knob settings "mean" what you expect they should mean. Part of this is due to the interaction of the controls. Part

is due to the new shelf slopes and part due to a lack of standards regarding shelf specification.

2) You may find yourself leaning towards shelf frequencies closer to the mids than you are used to and the "action" seems closer to the edges

of the spectrum than your other EQs. Same reasons as above.

3) You may also find yourself getting away with what seems like a massive amount of boost. Where the knobs end up, may seem scarey

particularly for mastering. Keep in mind that, even at maximum boost, a wide bell might only max out at 6 dB of boost (less for the lowest

band) and only reaches 20 dB at the narrowest bandwidth. On the other hand, because of how transparent this EQ is, you might actually

be EQing more than you could with a different unit. Taste rules, test benches don't make hit records, believe your ears.

4) Sometimes the shelfs will sound pretty weird, especially (only) at the narrow bandwidth settings. They might seem to be having a

complex effect and not only at the "dialed in" frequency. This is certainly possible. Try wider bandwidths at first.

5)A reasonable starting point for the Bandwidth for shelves is straight up or between 11:00 and 1:00. It was designed this way and is roughly

where the maximum flatness around the "knee" is, combined with a well defined steep slope.

6) The back panel I/O level switch is important to set properly in order to maximize headroom and ensure that there is not an unwanted

6 dB level loss. However, there may be situations where a deliberate goal might be to make the Mini Massive clip early. For example, one

could use the "+4 UNBALANCED" setting (assuming it is patched into balanced gear) and get 6 dB less headroom or use the "-10

UNBALANCED" setting which will clip the input 12 dB early.

7) And speaking of clipping, there are no "Clip LEDs" mostly because like the Massive Passive, the headroom is generally outrageous. For

example the balanced output clips at +30 dBm which is about 6 dB more than most gear and 8-10 dB more than most A to D converters.

That said, one still needs to always be listening and should be aware that clipping may be possible with extreme settings.

8) The Mini Massive may sound remarkably different from other high end EQs and completely different from the console EQs. Yes, this

is quite deliberate. Hopefully it sounds better, sweeter, more musical and it complements your console EQs. We saw little need for yet

another variation of the standard parametric with only subtle sonic differences. We suggest using the Mini Massive before tape, for the

bulk of the EQ tasks and then using the console EQs for some fine tweaking and where narrow Q touch-ups like notches are needed. The

Mini Massive is equally at home doing big, powerful EQ tasks such as is sometimes required for tracking drums, bass and guitars, or for

doing those demanding jobs where subtlety is required like vocals and mastering.

9) Of course the Mini will get compared to the Massive Passive which gets compared to vintage Pultecs and to Manley's Enhanced Pultec

EQs so maybe a few words from the designer are appropriate. First things first - The vintage Pultec EQ section was designed by Western

Electric and decades later Eugene Shenk added his gain stage and formed a company called Pulse Technologies to manufacture these EQs.

Shenk's design used 4 triodes (2 tubes) in a balanced topology and 3 transformers, and we might point to the interstage transformer and

less than optimal drive circuitry for its vintage Pultec crunch . This made it a favorite for kick and sometimes bass guitar during the 70's

and 80's but may have been too low fidelity to be used on much else. Of course, most Pultecs by that time had drifted to the point where

if one had 10, one was lucky if two sounded similar enough for stereo. The Manley Pultecs were designed initially for mastering and a

cleaner gain stage was used and transformers were chosen that were flatter and cleaner and more consistant. Of course, the exact values

of the original EQ components were used, but the quality of capacitors, resistors and pots had improved and were used. So the original EQ

shapes are intact along with several new frequencies added. Pultecs have been a studio and broadcast standard since the 60's and that most

engineers used both the boost and cut knobs at the same time - so it may be a bit funny that what we call "the Pultec Curve" wasn't described

until the late 90's and wasn't resurrected earlier.

The Massive Passive was designed as a tracking EQ and as an alternative or addition to the usual tools like console EQs and plugs.

A) There were hundreds of op-amp based parametric EQs and a growing number of software based simulations of that idea. Even a Manley

variation on that idea wouldn't have been so different and we didn't want to use op-amps (but ended up using one in the end)

B) Nobody had really addressed the issue that most engineer's favorite EQs were Neves, APIs and Pultecs and nobody had really done an

new inductor based EQ design in decades.

C) There was more of a percieved need for a new tracking EQ than a 'mastering EQ'. Besides back then there were a lot fewer people calling

themselves mastering engineers. The idea of strapping an EQ across the mix at that time was pretty unusual and almost unheard of.

D) So we set out to design an EQ that would be good for guitars, bass, keys and drums, and of course it ended up being used for almost

everything else (like vocals) and started a fashion of EQing the stereo buss (for better or worse).

The Mini Massive came about due to the designer finally finding a solid state gain stage he liked a lot (it was developed for an A/D converter)

and because he appreciated how the Massive came to be used and how that style of EQ might be improved for some users. Of course, some

use the Massive for its color and there was no need to repeat that (if that is what you need we still build the Massive). The Mini was envisioned

as a buss EQ so and was optimised for that (it is clean), so, of course, we expect it will get used for everything else.

7

Page 8

More Mini-Ponderings from the Designer

Clean versus colored - Active versus Passive - Tape versus Digital - well it all gets a bit tiresome. Here is the

real deal: they are all a bit colored and for the most part remarkably clean. So if anything we are basing our

preferences on which subtle flavor of color we either happen to like, or believe we need (based on something

we read somewhere) which may be just a slightly familiar sound rather than some magnificient life changing

event. No magic, just good tools. The music is the magic.

Does Digital require some analog warmth, some color to make a great recording? Not necessarily. For

example some recordings call for "as clean as possible" and even some instruments within an otherwise

grungy mix may sound best or provide a wonderful contrast when made as clean as possible. And while this

designer doesn't claim that today's hi end digital is absolutely clean and transparerent or clinical and sterile,

adding more and more stages of processing whether analog or digital will mostly tend to make it less

transparent, less true to the source. Choose wisely.

Will some analog processor fix digital's flaws? This designer hears digital's flaws as a subtle form of time

smear. Much analog on the other hand can be characterized as having various forms of harmonic and

intermodulation distortion, plus often some time smear caused by phase shifts which are practically inevitable

given the normal frequency responses of audio gear. One form of distortion doesn't cancel out the other and

adding more time smear should make things worse. However, there are some families of distortion that may

be euphonic and either add to the effect of 3D depth, some distortions give an effect of fatness or warmth

(transformers), and some distortions that seem to evoke vintage tone like a familiar smell. So, 'as clean as

possible' is appropriate for some situations and somewhat controlled dirt is appropriate for others. Beware of

getting the mind-set that either goal is appropriate for every sound and every situation. Should every house

should be the same color?

There are many situations where one might want a processor (or preamplifier) that doesn't leave its thumbprint

on the sound. Typically mastering is one place for a transparent EQ, especially when the mix is already pretty

damn fine. Other situations include most classical and live ensemble or choir recordings, a lot of acoustic

recordings, folk, country, jazz, choir, classical, etc. While the MiniMassive does have very transparent gain

stages, and the EQ sections are passive so they have less artifacts at low to modereate settings than most opamp based EQs, it should be pointed out that the 'most useful' settings with any EQ or compressor regardless

of how clean it started, will probably leave a thumbprint. Sometimes 'natural' is very good goal, and it can be

the most familiar. The place to start is player, instrument, room and then mic choice & position, preamp &

converter. When one is lucky enough to get the above right, rarely is EQ or compression even required.

With the MiniMassive, expect a generally clean and natural sound with conservative to moderate settings.

However, it will gradually introduce a signature color at more drastic settings. With the transformer,

one can introduce some vintage color and subtle warmth. The downside with iron, and there is always a

downside, is some subtle time smear that might be noticed with sounds that have lots of energy (and tightness)

at the edges of the spectrum. Worth a check on big solid mixes or kick drum tracks or high hat tracks. Drastic

EQ settings (from any EQ) can 'time-smear' too. EQ changes generally introduce phase shift so listen for time

smear with spectrum changes.

And for those who have need for more color and more of that elusive vintage vibe, we designed another EQ to

do that function. It is called the Massive Passive, and it is a vacuum tube based unit originally designed to be

an alternative to the typically boring EQs available then. Ya know? In other words, if you like chocolate then

buy chocolate, if you like strawberry buy strawberry, if you like both get both. And yes, there are far more

similarities than differences between the Massive Passive and MiniMassive and the differences are meant to

reach out more to those for who the Massivo wasn't quite right. And for those who seriously dig the Massivo

for everything it is (and isn't), well, we have no plans of discontinueing it or changing it.

8

Page 9

Just a few notes for plug-in users.

One question that gets asked a lot is “Why no ‘Link’ switch “or “Why not a stereo EQ with one set of

controls?” Yeah, it would be sweet sometimes, especially if fewer knobs resulted in lower cost. The most

accurate answer is “you guys are spoiled, ha ha”. To do it in digital is almost a no-brainer and is just a matter

of passing a few numbers to the other side's parameter registers. To do it on an analog compressor is a bit

more involved but still pretty easy and not pricey. But doing it on an analog EQ, requires big expensive

multi-deck switches, pots, and practically all audio switching be done with relays or FETs. Now given that

the rotary switches and all the pots are already custom and difficult to source, getting ones that are twice as

deep, and 4 times rarer, and not eliminate the need for individual channel control, would add a lot of cost to

the unit. Besides that, considering that the Mini is really stuffed with parts, just routing printed circuit board

traces, would be difficult and involve compromises to the integrity. Basically, a stereo link or single set of

knobs is way more difficult to do for an analog EQ, somewhat easier for some analog compressors and

linking within an algorithm is extremely easy. Many DSP guys envy analog for how simple designs often

just sound great, we analog-heads envy a few cheap & easy aspects of digital.

Next question…”Why no Manley EQ plug-in?” Maybe we are a bit too picky, but we haven’t heard a plug in

that really approximates the subtleties of an inductor based EQ or even a transformer. Maybe some day, we’ll

combine our knowledge with some DSP wizard’s knowledge and do something cool, and cheap (which is

really what you are asking for, right?). We might also say, that we would prefer to do something new and

different than try to clone our existing stuff. If and when Manley does a plug-in it should be at least as radical

and special as the hardware. In other words, take advantage of digital technology and do what it can do best,

rather than the questionable effort of trying to recreate (again) analog processes especially if this is where

digital technology is at its weakest or most immature for now. However, like yourselves, we do use plug-ins,

music programs, etc, and evaluate too many to name, and we are keeping our ears and eyes open. Of course,

some of you know that the we have contributed to some non-Manley plug-ins that are highly regarded.

Meanwhile progress continues and we are continuing to listen, and maybe some day we'll hook up with some

adventurous DSP hot shots with more on their minds than "clone market $". We've lost count on how many

1176 and N*VE emulations and simulations and copies and look-alikes there are. One was enough and none

seem to truly stand out, but all seem to fall short of the original for most pundits. In fact, in their day, most of

the originals had a far weaker reputation (disposable) than eBay sellers might want you to think about.

Or this question…” Have you guys thought about digital controlled analog so that maybe we can control the

EQ like a plug-in and automate or even recall settings?” Gee, we would love to but….. we, as an industry,

just don’t have the technology yet that would enable that without compromising the signal integrity (and do it

at a reasonable cost). For us, that has to be a prime consideration, and it is really why most of our customers

come to Manley. We’ve been approached by a few companies asking to put our front panels on a computer

screen for recalls, but none have suggested any reason why that would be better or more accurate or cheaper

than a pencil and paper, especially when we supply a paper template in the back of the manual. So, our

decisions are based on why people buy our stuff, which is usually the quality and sound. Meanwhile, we are

keeping our ears and eyes open for some enabling technology that might allow no-loss remote control .

Or the big question…”Why do analog EQs sound better or at least different than my 50 plug-ins?” Maybe

DSP guys trying to model analog have zero experience with analog (or music production). Maybe young

guys who haven’t yet developed their ears are developing audio software. Maybe we can motivate the DSP

wizards to develop their hearing if we point out that the best analog was all done by guys with great

ears.Maybe FIR filters used everywhere in digital audio might be a little more audible than some gurus

presume. Maybe human hearing and both analog and digital processing are deeper topics than most people

believe and all of us are still learning. The good news is that the difference is narrowing every year and

maybe some day the choice will be mostly whether this signal path is analog or digital or the order that you

prefer to process or whether you prefer LCD screens or physical knobs and switches.

9

Page 10

This section is borrowed from the Massive Passive Manual

Beginnings

The very earliest equalizers were very simple and primitive by

todays standards. Yes, simpler than the hi-fi "bass" and "treble"

controls we grew up with. The first tone controls were like the tone

controls on an electric guitar. They used only capacitors and

potentiometers and were extremely simple. Passive simply means

no "active" (powered) parts and active parts include transistors,

FETs, tubes and ICs where gain is implied. "Passive" also implies

no boost is possible - only cut. The most recent "purely passive EQ"

we know of was the EQ-500 designed by Art Davis and built by a

number of companies including United Recording and Altec Lansing.

It had a 10 dB insertion loss. No tubes. It had boost and cut positions

but boost just meant less loss. Manley Labs re-created this vintage

piece and added a tube gain make-up amp for that 10 dB or makeup gain to restore unity levels. It has a certain sweetness too.

You have probably heard of passive crossovers and active crossovers

in respect to speakers or speaker systems. Each has advantages.

Almost all hi-fi speakers use a passive crossover mounted in the

speaker cabinet. Only one amp is required per speaker. Again,

passive refers to the crossover using only capacitors, inductors and

resistors. Active here refers to multiple power amplifiers.

One of the main design goals of the Massive Passive was to use only

capacitors, inductors and resistors to change the tone. Pultecs do it

this way too and many of our favorite vintage EQs also relied on

inductors and caps. In fact, since op-amps became less expensive

than inductors, virtually every EQ that came out since the mid '70's

substituted ICs for inductors. One is a coil of copper wire around a

magnetic core and the other is probably 20 or more transistors. Does

the phrase "throwing out the baby with the bath water" ring a bell?

Another design goal was to avoid having the EQ in a negative

feedback loop. Baxandall invented the common circuit that did this.

It simplified potentiometer requirements, minimised the number of

parts and was essentially convenient. Any EQ where "flat" is in the

middle of the pot's range and turning the pot one way boosts and the

other way cuts is a variation of the old Baxandall EQ. Pultecs are not

this way. Flat is fully counter-clockwise. For the Massive Passive,

Baxandall was not an option. The classical definition of "passive"

has little to do with "feedback circuits" and we are stretching the

definition a bit here, however, it certainly is more passive this way.

We only use amplification to boost the signal. Flat Gain ! What goes

in is what comes out. If we didn't use any amplifiers, you would need

to return the signal to a mic pre because the EQ circuit eats about 50

dB of gain. Luckily, you don't have to think about this.

We visited a few top studios and asked "what do you want from a

new EQ ?" They unanamously asked for "click switch frequencies",

"character" rather than "clinical" and not another boring, modern

sterile EQ. They had conventional EQs all over the console and

wanted something different. They had a few choice gutsy EQs with

"click frequencies" that were also inductor/capacitor based (which

is why the frequencies were on a rotary switch). Requests like

"powerful", "flexible", "unusual" and "dramatic" kept coming up.

We started with these goals: modern parametric-like operation,

passive tone techniques through-out, and features different from

anything currently available and it had to sound spectacular.

"The Super-Pultec"

Manley Labs has been building a few versions of the Pultec-style

EQs for many years as well as an updated version of the EQ-500

(another vintage EQ). These are classic passive EQs combined with

Manley's own gain make-up amplifiers. Engineers loved them but

we often heard requests for a Manley Parametric EQ with all the

modern features but done with tubes. Another request we had was

for a "Super-Pultec". We briefly considered combining the "best of"

Pultecs into a new product but the idea of some bands only boosting

and some only cutting could only be justified in an authentic vintage

re-creation and not a new EQ.

The next challenge was to make an EQ that sounded as good or better

than a Pultec. With all the hundreds of EQs designed since the

Pultec, none really beat them for sheer fatness. We knew why. Two

reasons. EQP1-A's have separate knobs for boost and cut. People

tend to use both at the same time. You might think that this would

just cancel out - wrong.... You get what is known as the "Pultec

Curve" . The deep lows are boosted, the slope towards "flat"

becomes steeper, and a few dB of dip occurs in the low mids. The

second reason for the fatness and warmth was the use of inductors

and transformers that saturate nicely combined with vacuum tubes

for preserving the headroom and signal integrity.

Could we use a "bandwidth control" to simulate the "Pultec Curve(s)?

The Pultec curve is officially a shelf and shelf EQs don't have a

"bandwidth or Q knob"- only the bell curves. So, if we built a passive

parametric where each band could switch to shelf or bell and used

that "bandwidth" knob in the shelf modes we could not only simulate

the Pultecs but add another parameter to the "Parametric EQ" We

found that we could apply the "Pultec Curve" to the highs with

equally impressive results. This is very new.

The Massive Passive differs from Pultecs in several important areas.

Rather than copy any particular part of a Pultec, we designed the

"Massivo" from the ground up. As mentioned, each band being able

to boost or cut and switch from shelf to bell is quite different from

Pultecs. This required a different topology than Pultecs which like

most EQs utilize a "series" connection from band to band. The

Massive Passive uses a "parallel" connection scheme.

A series connection would imply that for each band's 20 dB of boost,

there is actually 20 dB (more in reality) of loss in the flat settings.

Yeah, that adds up to over 80 dB, right there, and then there is

significant losses involved if one intends to use the same components

to cut and to boost. And more losses in the filter and "gain trim". That

much loss would mean, that much gain, and to avoid noise there

would need to be gain stages between each band and if done with

tubes would end up being truly massive, hot and power hungry.

Instead, we used a parallel topology. Not only are the losses much

more reasonable (50 dB total!) but we believe it sounds more

"natural" and "musical". In many ways the Massive Passive is a very

unusual EQ, from how it is built, to how it is to operate and most

importantly how it sounds.

We designed these circuits using precise digital EQ simulations,

SPICE3 for electronic simulations, and beta tested prototypes in

major studios and mastering rooms for opinions from some of the

best "ears" in the business.

10

Page 11

"The Passive Parametric"

For years, we had been getting requests for a Manley parametric

equalizer, but it looked daunting because every parametric we knew

of used many op-amps and a "conventional parametric" would be

very impractical to do with tubes. Not impossible, but it might take

upwards of a dozen tubes per channel. A hybrid design using chips

for cheapness and tubes for THD was almost opposite of how

Manley Labs approaches professional audio gear and tube designs.

Could we combine the best aspects of Pultecs, old console EQs and

high end dedicated parametric EQs?

What is the definition of a "Parametric Equalizer"? We asked the

man who invented the first Parametric Equalizer and coined the

term. He shrugged his shoulders and indicated there really is no

definition and it has become just a common description for all sorts

of EQs. He presented a paper to the AES in 1971 when he was 19.

His name is George Massenburg and still manufactures some of the

best parametric EQs (GML) and still uses them daily for all of his

major recordings. Maybe he originally meant "an EQ where one

could adjust the level, frequency and Q independently". He probably

also meant continuously variable controls (as was the fashion) but

this was the first aspect to be "modified" when mastering engineers

needed reset-ability and rotary switches. The next development was

the variation of "Constant Bandwidth" as opposed to "Constant Q"

in the original circuits. "Constant Q" implies the Q or bell shape

stays the same at every setting of boost and cut. "Constant Bandwidth"

implies the Q gets wider near flat and narrower as you boost or cut

more. Pultecs and passive EQs were of the constant bandwidth type

and most console EQs and digital EQs today are the constant

bandwidth type because most of us prefer "musical" over "surgical".

Lately we have seen the word "parametric" used for EQs without

even a Q control.

We can call the Massive Passive a "passive parametric" but .... it

differs from George's concepts in a significant way. And this is

important to understand, to best use the Massive Passive. The dB

and bandwidth knobs are

Q of the bell curve widens when the dB control is closer to flat. More

significantly, the boost or cut depth varies with the bandwidth

control. At the narrowest bandwidths (clockwise) you can dial in 20

dB of boost or cut. At the widest bandwidths you can only boost or

cut 6 dB (and only 2 dB in the two 22-1K bands). Somehow, this still

sounds musical and natural. The reason seems to be, simply using

basic parts in a natural way without forcing them to behave in some

idealized conceptual framework.

not independent. We already noted that the

Another important concept. When you use the shelf curves the

frequencies on the panel may or may nor correspond to other EQ's

frequency markings. It seems there are accepted standards for filters

and bell curves for specifying frequency, but not shelves. We use a

common form of spec where the "freq" corresponds to the half-way

dB point. So, if you have a shelf boost of 20 db set at 100 Hz, then

at 100, it is boosting 10 dB. The full 20 dB of boost is happening

until below 30 Hz. Not only that, like every other shelf EQ there will

be a few dB of boost as high as 500 Hz or 1K. This is all normal,

except.........

Except we now have a working "bandwidth control" in shelf mode.

With the bandwidth set fully counter-clockwise, these shelves

approximate virtually ever other EQ's shelf (given that some use a

different freq spec). As you turn the bandwidth control clockwise,

everything changes and it breaks all the rules (and sounds awesome).

Lets use an example. If graphs are more your style, refer to these as

well. Suppose we use 4.7K on the third band by switching to "boost"

and "shelf" and turning the "bandwidth control" fully counterclockwise. Careful with levels from here on out. Just for fun, select

4.7kHz and turn the "dB" control to the max - fully clockwise. This

should be like most other shelf EQs, except with better fidelity, (if

you can set them to around 5 kHz!) . Now, slowly turn the

"bandwidth" clockwise. Near 12:00 it should be getting "special". It

also sounds higher (in freq). Keep turning. At fully clockwise it

seems to have gotten a little higher and some of the sibilance is

actually less than in "bypass". It sort of sounds as if the bandwidth

is acting like a variable frequency control but better. More air - less

harshness.

Compared to "conventional parametrics" in all their variations, the

Massive Passive has just "upped the ante" by adding a few useful

new parameters. The first is the use of the "bandwidth" in shelf

modes. Second is the ability to switch each and every band into shelf.

The original parametrics were only "bell". We have seen some EQs

that allow the lowest and highest bands to switch to shelf. Now you

can use two HF shelfs to fine tune in new ways without chaining

several boxes together. Lastly, each band can be bypassed or

switched from boost to cut without losing a knob setting. This allows

twice the resolution from the "dB" pots and allows one to exagerate

an offending note in order to nail the frequency easier, then simply

switch to "cut". You can always check, without losing the dB setting

by switching back to "boost" for a minute. You can also have

absolute confidence that the "zero" position on the dB pot is "flat"

which is not the case with center detented pots. Mechanical center

and electrical center are rarely the same.

"SPICE" printout

"Normal Shelf" Wide Bandwidth

"Special Shelf" Medium Bandwidth

"Pultec Shelf" Narrow Bandwidth

Bell Cut Narrow Bandwidth

11

Page 12

Why Passive?

And Why Parallel?

If you hate tech talk, just skip this section - it has to do with

electronic parts and circuits and design philosophy.

All EQs use capacitors. They are very easy to use, predictible,

cheap and simple. Some sound slightly better than others.

Inductors do almost the mirror function of capacitors.

Unfortunately, they can be difficult to use (they can pick up

hum), they can be difficult to predict (the essential inductance

value usually depends on the power going through them

which varies with audio), they are expensive and generally

have to be custom made for EQs. These are qualities that labcoat engineers tend to scowl at. Some effort was aimed at

replacing the poor inductors and more effort made to badmouth them and justify these new circuits. The main reason

was cost. All of the "classic" Eqs used real inductors and that

has become the dividing line "sought after vintage" and just

old.

What the lab-coats didn't consider was that inductors may

have had real but subtle advantages. Is it only obvious to

"purists" that a coil of copper wire may sound better than 2 or

3 op-amps, each with over twenty transistors, hundreds of dBs

of negative feedback along with "hiss", cross-over distortion

and hard harsh clipping?

We mentioned the inductance value can change with applied

power. This also turns out to be a surprising advantage. For

example, in the low shelf, with heavy boosts and loud low

frequency signals, at some point, the inductor begins to

saturate and loses inductance. Sort of a cross between an EQ

and a low freq limiter. The trick is to design the inductor to

saturate at the right point and in the right way.

In the mid-bands and bell curves a somewhat different effect

happens. The center-frequency shifts slightly depending on

both the waveform and signal envelope. This "sound" is the

easily recognizeable signature of vintage EQs. It is not a type

of harmonic distortion (though it can be mistaken for this on

a test-bench) but more of a slight modulation effect.

Inductors in the form of transformers are also a large part of

why vintage gear is often described as "warm" whether it was

built with tubes or transistors. In fact, the quality of the

transformer has always been directly related to whether a

piece of audio gear has become sought after. Saturation in this

case involves adding odd harmonics to very low frequencies

which either tends to make lows audible in small speakers or

makes the bass sound louder and richer (while still measuring

"flat"). The key is how much. A little seems to be sometimes

desireable (not always) and a little more is beginning to be

muddy and a little more can best be described as "blat". The

number of audio transformer experts has fallen to a mere hand

full and some of them are getting very old.

The Massive Passive is a "parallel design" as opposed to the

far more common "series design". A few pages back, we

mentioned the main reason for going with a parallel design

was to avoid extreme signal loss, which would require extreme

gains and present the problem of noise or extreme cost. The

parallel approach not only avoided this but has a number of

advantages as well.

With the series EQ design, if you set 3 bands to boost the same

frequency 15 dB each, the total boost will be band one plus

two plus three - or 45 dB - but then it would probably be

distorting in a rather ugly way. With the Massive Passive, you

can dial in 4 bands to boost 20 db near 1K and it still will only

boost 20 dB total. If you tend to boost 4 bands at widely

separated frequencies (like what happens on two day mixes

with sneaky producers), it tends sound almost flat, but louder.

Other EQs seem to sound worse and worse as you boost more

and more. For some people it will act as a "safety feature" and

prevent them from goofy EQ. Occasionally, you may be

surprised with what looks like radical settings and how close

to flat it sounds. A side effect is that if you are already boosting

a lot of highs in one band, if you attempt to use another band

to tweak it, the second band will seem rather ineffective. You

may have to back off on that first band to get the desired tone.

You actually have to work at making the Massive Passive

sound like heavy-handed EQ by using a balanced combination

of boosts and cuts. In a sense it pushes you towards how the

killer engineers always suggest to use EQs (ie gentle, not

much, more cut than boost). This is good.

While there may be interesting arguments against any

interaction between EQ bands, the reasons tend to be more for

purely technical biases than based on listening. In nature and

acoustics and instrument design, very little of the factors that

affect tone are isolated from each other. Consider how a

guitar's string vibrates the bridge which vibrates the sound

board, resonates in the body, and in turn vibrates the bridge

and returns to the string. What is isolated? The fact that the

bands are NOT isolated from each other in the Massivo is one

of the reasons it does tend to sound more natural and less

electronic. We noticed this effect in a few passive graphic

EQs, notably the "560" and a cut-only 1/3 octave EQ.

There is a type of interaction we did avoid. That is inductor to

inductor coupling. It is caused by the magnetic field created

by one inductor to be picked up by another. It can cause the

inductors to become an unexpected value, or if it is band to

band, can cause effects that can best be described as goofy. In

the Filter Section we utilized close inductor spacing to get

some hum-bucking action but avoid magnetic coupling with

careful positioning. Some kinds of interaction suck and some

are beneficial.

12

Page 13

Phase Shift?

Deadly topic. This is probably the most misunderstood term floating

about in the mixing community. Lots of people blame or name phase

shift for just about any audio problem that doesn't sound like typical

distortion. We ask that you try to approach this subject with an open

mind and forget what you may have heard about phase for now.This

is not to be confused with "time alignment" as used in speakers, or

the "phase" buttons on the console and multi-mic problems.

First - all analog EQs have phase shift and that the amount is directly

related to the "shape" of the EQ curve. Most digital EQs too. In fact,

one could have 3 analog EQs, 3 digital EQs, and an "acoustic

equivilant", and a passive EQ, each with the same EQ shape, and

ALL will have the same phase shift characteristics. This is a law, a

fact and not really a problem. The two exceptions are: digital EQs

with additional algorithms designed to "restore" the phase, and a

rare family of digital EQs called FIR filters based on FFT techniques.

Second - Opinions abound that an EQ's phase shift should fall within

certain simple parameters particularly by engineers who have

designed unpopular EQs. The Massive Passive has more phase shift

than most in the filters and shelfs and leans towards less in the bells.

Does this correspond to an inferior EQ? Judge for yourself.

Third - Many people use the word "phase shift" to describe a nasty

quality that some old EQs have and also blame inductors for this. Its

not phase shift. Some inductor based EQs use inductors that are too

small, tend to saturate way too easily, and create an unpleasant

distortion. The Massivo (of course) uses massive inductors (compared

to the typical type) which were chosen through listening tests. In fact

we use several different sizes in different parts of the circuit based

on experiments as to which size combined the right electrical

characteristics and "sounded best". The other very audible quality

people confuse with phase shift is "ringing". Ringing is just a few

steps under oscillating and is mostly related to narrow Qs. It is more

accurately described as a time based problem than phase shift and

is far easier to hear than phase shift. For our purposes, in this circuit,

these inductors have no more phase shift or ringing than a capacitor.

Fourth - A given EQ "shape" should have a given phase shift, group

delay and impulse response. There also exist easy circuits that

produce phase shift without a significant change in frequency

response. These are generally called "all-pass networks" and are

usually difficult to hear by themselves. You may have experienced

a worse case scenario if you have ever listened to a "phase-shifter"

with the "blend" set to 100% (so that none of the source was mixed

in) and the modulation to zero. Sounded un-effected, didn't it, and

that may have been over 1000 degrees of phase shift. Group delay

and impulse response describe the signal in time rather than frequency

and are just different ways of describing phase shift. Some research

shows these effects are audible and some not. The Massive Passive

tends to show that group delay in the mids is more audible than

towards the edges of the spectrum and there may be interesting

exceptions to generalities and conventional wisdoms. The audible

differences between EQs seems to have more to do with Q, distortions,

headroom and topology than with phase shift.

Fifth - Phase Shift is not as important as functionality. For example,

we chose very steep slopes for some of the filters because we

strongly believe the "job" of a filter is to remove garbage while

minimally affecting the desired signal. A gentler slope would have

brought less phase shift but would not have removed as much crap.

Mini Massive and Massive Passive - Similarities & Differences

The Mini Massive is obviously based on the lowest and highest

bands from the Massive Passive. In fact, they share about 95% of the

same components and about 85% of the same circuit board layout.

Most settings using those two bands can be easily transferred from

one to the other.

One intention of the Mini Massive is to be a good answer for those

who took issue with one or another factor of the Massive Passive

even though the number of those who had any issue were few and

most likely the noisiest of these individuals will still find some

rationalizations in their attempts to be internet-orious. But they did

raise some valid points and inspired an alternative version.

Number 1) The Massivo is too colored for mastering. Maybe for

some, but many of the top mastering engineers do use it 5 days a

week and it happens to be one of the most likely pieces of gear to be

seen in professional mastering rooms. That said, the Mini Massive

is designed to be one of the cleanest and most transparent equalizers

ever offered and which is easily verified by you hitting the hardwire

bypass switch reasonably frequently.

On the other hand, the Massive Passive was designed with tubes and

transformers for deliberate color and for those situations where

some departure from digital sterility is desired it is a better choice

over the Mini Massive. These days you might have a variety of ways

to generate "warmth" so the choice of EQ is more open. In other

words the Massivo was designed more with vintage console and

Pultec EQs in mind and created for similar applications. The Mini

Massive was designed more for buss EQ and mastering as well as for

surround and maybe tighter budgets, which brings us to.....

Number 2) The price... Not much we could do about the cost of the

Massive Passive because it does require a lot of parts and many of

them are custom and most are premium quality. By halving the

number of bands, making the chassis smaller/simpler, & going

with solid state, we were able to offer a slimmed-down version

with a slimmed-down price.

Some might also see the Mini Massive as a single channel 4 band EQ

and set up their cabling or patch bay with that in mind. This gives

them the versatility of a 4 band EQ or a stereo 2 band in a 1 rack unit

package at a competitive price, but with that well known Massive

sound. Great for tracking, great for overdubs, great for mixing.

Number 3) Sculpting in the extreme lows and highs. The Mini

Massive is an evolution of the basic Massive Passive concept and is

designed to really provide some interesting abilities to create huge

bottom that remains tight (transformerless) plus amazingly sweet air

for brilliance or sparkle tweaking. In fact, a warning to not over-do

those kinds of boosts needs to be mentioned. Just because you can

now doesn't mean that you always should. And if you lose fidelity

in other parts of the chain, boosting here might exagerate problems.

Number 4) Portability and reliability. Reliability has never been

much of an issue with the Massive Passive nor are tubes in reality

a fragile technology - quite the opposite, though eventually they

should be replaced. However the myth remains, and for live and

broadcast applications many prefer solid state. These situations also

tend to prefer the smaller size, less heat, the simplicity and lighter

weight. This is for them.

13

Page 14

Just like most EQs, a 100Hz low shelf

doesn't reach "max" until about 10 Hz.

LOW SHELF CURVES

Normal Shelf Wide Bandwidth

(slope =about 4 to 5 dB/oct)

Special Shelf Medium Bandwidth

(slope = about 8 to 10 dB/oct)

"Pultec Shelf" Narrow Bandwidth

Bell Cut Narrow Bandwidth

(just for reference)

These 4 lowest frequency shelf curves are unique

to the Mini Massive. These curves illustrate

LOW FREQ SHEL VES (22, 33, 47, 68 are new)

Boost at maximum and Bandwidth at 11:00.

BANDWIDTH SETTING AT 1 1:00

+20

+18

+16

+14

+12

+10

+8

+6

+4

+2

d

-0

B

r

-2

-4

-6

-8

-10

-12

-14

-16

-18

-20

20 50k50 100 200 500 1k 2k 5k 10k 20k

150Hz

100Hz

68Hz

33Hz

47Hz

22Hz

Hz

FREQUENCY RESPONSE

14

Page 15

MORE 100Hz SHELVES SHOWING

BOOST AND CUT WITH VARIOUS BANDWIDTHS

THIS IS ABOUT +1.5 DB

LOW SHELF +20 WIDE BW

LOW SHELF +20 MED BW

LOW SHELF -20 MED BW

LOW SHELF -20 WIDE BW

AT 300 Hz AND NEGLIGIBLE

SPICE SIMULATION CURVES

THESE CURVES SHOW ONE OF THE IDEOSYNCRACIES

AND IT IS POSSIBLE FOR A LF BOOST TO SOUND AS IF IT HAS LESS LOWS

DEPENDING ON THE FREQUENCY AND INSTRUMENT.

SIMILAR CURVES APPLY TO THE HIGH SHELVES AND

PARTICULARLY 10K AND 12K CAN BE STRANGE WHEN THE BW IS NARROW

50 100

NOTICE THIS 8 dB BOOST AT 100 Hz

WHILE SHELF CUTTING 100 Hz

LOW SHELF +20 WIDE BW

LOW SHELF +20 NARROW BW

LOW SHELF -20 NARROW BW

LOW SHELF -20 WIDE BW

AND NOTICE THIS 8 dB DIP

WHILE SHELF BOOSTING

THE HALF WAY (10 dB) POINT

HAS SHIFTED TO 50 Hz

15

Page 16

TYPICAL BELL CURVES

"dB" set at max (20 dB) and changing the Bandwidth

Narrow Bandwidth

Bandwidth at 12:00

Wide Bandwidth

Wide Bandwidth

Bandwidth at 12:00

Narrow Bandwidth

Changing "dB" and Changing Bandwidth

Max Boost Narrow Bandwidth

12:00 Boost Narrow Bandwidth

Max Boost Wide Bandwidth

12:00 Boost Wide Bandwidth

16

Page 17

THE GUTS

GAIN TRIM RIGHT

30

30

AC MAINS

VOLTAGE

1) To Open:There should be little or no reason to open the Mini Massive - No user servicable parts, no tubes to change and

about the only reason to take the top off is unity gain adjustments. One can access the fuse on the back panel power connector

without removing the top. A few Phillips head screws hold the perforated top in place and when these are removed the top should

easily slide back. Other than mains voltage at the power switch and towards the right side of the mains transfomer box, there

are no high voltages or currents but mains voltages can be dangerous so caution cannot be over-emphasized. A trained service

technician is generally the best choice for any service or adjustments. The active gain blocks, the Rapture amps, are potted in

epoxy after critical part numbers are scraped off, but a trained service technician can easily replace a module if needed. They

are definately not interchangable with other epoxied gain blocks.

2) Replacing a fuse. The fuse is located in the IEC power connector on the back panel. Disconnect the power cable first to

prevent any chance of getting a shock. A little rectangular plastic panel needs to be gently pryed open and the fuse becomes

exposed. This is a xyz miniture size fuse and is 1A for 100 and 117 volt AC countries and .5A for 220 and 240 volt countries.

3) Changing AC MAINS VOLTAGE: This operation really does require a technician. For 117 volt AC power there are circuit

board traces that pre-select the proper transformer taps. For 100 volt / 200 / 220 and 240 volt AC power these traces need to

be cut and jumpers soldered in at appropriate pad locations. Manley does this for each destination that a Mini Massive is shipped

to and most international Manley / Langevin dealers are capable of making the change if needed. Part of the reason we did this

is to discourage some grey market sales. However the following page does show this section of the board in detail and what

traces need to be well cut and where jumpers need to be soldered for various AC line voltages.

4) Adjusting unity gain. There are only two trim pots in the Mini Massive and they are located towards the back of the unit.

The left one is for the left side or channel 1, and the right one adjusts the right side. Be sure that each band is in bypass on the

boost/out/cut toggles and the master bypass is not in bypass (green LED). Also be sure that the back panel toggle that sets

interface or I/O level is properly set. Feed the Mini Massive with 1 kHz at an appropriate level (typically +4 dBu or dBm) and

adjust the trim pots for the same level coming out the Mini Massive. Check using the master bypass switch and there should

be less than .1 dB level change, and if the is .01 dB change stop adjusting already. There may be .1 dB level change just due

to the varieties of loading and source impedances in normal studio situations anyways, and that is better than normal. The trim

pots only have a few dB of range and are only meant for unity gain adjustment with the Mini set flat.

17

Page 18

AC MAINS VOLTAGE SELECTION

This may involve soldering jumpers and cutting of printed circuit board traces.

Danger : There is a possibility of electric shock if power is connected and danger of

damage to the Mini Massive if the procedure is done wrong. This should only be done by a

trained technician and ONLY ever be done with the power cable removed.

PCB JUMPERS

PCB JUMPERS

1

23

4

5

7

TRANSFORMER BOX

FOR 117 VAC - PRINTED CIRCUIT BOARD TRACES SHOULD EXIST ON THE BOTTOM OF THE CIRCUIT BOARD

BETWEEN: 1 & 2, BETWEEN 5 & 7, AND BETWEEN 7 & 8 ONLY

IF NOT REMOVE ANY OTHER JUMPERS AND SOLDER THESE IN.

FOR 100 VAC - CUT THE TRACES BETWEEN 5 & 7, AND 7 & 8

A PCB TRACE SHOULD EXIST FROM 1 & 2

SOLDER JUMPERS FROM PADS 4 & 6 AND 6 & 8

FOR 220 / 240 VAC PRINTED CIRCUIT BOARD TRACES SHOULD EXIST ON THE BOTTOM OF THE CIRCUIT BOARD

BETWEEN 7 & 8 ONLY

CUT THE PCB JUMPER BETWEEN 1 & 2, ALSO BETWEEN 5 & 7

SOLDER JUMPERS BETWEEN PADS 2 & 3

6

8

1

2

3

4

5

6

8

7

TRANSFORMER BOX

ADD

ADD

ADD

CUT

TRACES CUT ON BOTTOM OF PRINTED CIRCUIT BOARD

18

Page 19

Equalizers

EQs range from simple bass and treble controls on a hifi system to

pretty tricky parametric EQs and 1/3 octave graphic EQs. As an

audio freak, you have probably tried quite a few EQs and have gotten

both great results and sometimes less than great and you probably

have a favorite EQ. Now that you probably have a digital system,

you may have questions about these digital EQs and the differences

between any analog and digital techniques. Let us begin at the

beginning, and then get into some real techniques. Who invented the

first electronic tone control? Who knows? The first hints of “flat”

electronics came decades later. Simple bell and shelf EQs seem to

have been born in the 1930's for telephone company use. The Pultec

passive circuits came from that era at Western Electric. "Graphic

EQs" seem to have been invented in the mid 60's and were common

by the early 70's. A 19 year old prodigy, George Massenburg first

described, in a 1971 AES paper, the “Parametric Equalizer”.

All EQs do one thing — they can make some bands or areas of

frequencies louder or quieter than others, manipulating the frequency

response. Speakers and mics do that to but we normally think of EQs

as something that allow us to alter the frequency response, deliberately,

with some knobs and buttons - including the GUI ones. Some

equalizers have no controls, they are part of a circuit and generally

are almost “invisible” to the user. A good example of this is the EQ

circuits used as “pre-emphasis” and “de-emphasis” used for analog

tape machines and radio broadcasting. The idea of these is to boost

the high frequencies before it hits the tape (or air), then reduce the

highs on playback (or reception). This reduces the hiss and noise and

usually allows a hotter signal which also improves the noise

performance. These EQs usually have trimmers available but we

would rarely consider using them for adjusting the tone. Instead, the

object is to get a ruler-flat response at this part of the signal chain.

It is still called an equalizer. In fact the original definition of

“equalizer” was a device to restore all the frequencies to be equal

again, in other words, force the frequency response to be as flat as

possible.

Other common EQs that you are probably familiar with include the

common 1/3 octave graphic EQs with about 30 or 60 cheap sliders

across the front panel. These are usually a good tool for tuning a

room, but they may be a difficult thing to use for individual sounds.

Most 1/3 oct EQs excel when a number of little tweaks spaced across

the spectrum are needed but not great for wide tonal changes. Too

many resonances. Some room tune experts are now relying on

parametrics with continuously variable frequency knobs apparently

to "nail" the peaks. One reason 1/3 octave EQs have a bad name are

the "real time analyzers" that display a single aspect of the frequency

response but without any time information, real or otherwise.

People often get much better results with warble tones, or tuning

rooms by ear with music. 1/3 octave EQs are appropriate for some

mastering tasks but are probably less used because they tend to scare

clients. The Mini Massive was not intended for room tuning.

Parametric EQs come in lots of flavours, 3, 4 or 5 bands, most with

3 knobs per band and lots of variations. The earliest ones offered

only bell shapes, no shelves, no filters. Today's most common

variation has 2 mid bells with Q, a high shelf, low shelf and filters.

We see these in many consoles and in outboard EQs at a wide range