Page 1

Mackie Industrial White Paper

Noise Sensing Using a Variation of the

nLMS Adaptive Filter with Auto Calibration

CHRIS JUBIEN, AES Member, COSTA LAKOUMENTAS, AES Member,

This White Paper discusses a system that will compensate for the noise level in a room by

measuring the program and noise level sensed through an ambient microphone. The system

then changes the program level in proportion to the noise level that was sensed through the

microphone. The technique that is presented here uses a combination of analog to digital

conversion (ADC), adaptive digital ltering running on a digital signal processor (DSP), and

digital to analog conversion (DAC). The adaptive lter employed is a variation on the Normalized Least Mean Squares (nLMS) method. This approach effectively “nulls out” any music

that was sensed at the ambient microphone after which the only thing that remains is the noise.

A Root Mean Square (RMS) measure of this noise level provides the ability to adjust the program level accordingly.

BRIAN RODEN, AES Member, DALE SHPAK, AES Member,

JEFF SONDERMEYER, AES Member

Mackie Designs, Woodinville, WA

0 Introduction

Virtually anyone who has ever listened to music in an automobile has realized this fundamental fact: while driving, the

music level must be louder than while the car is parked. The

reason for this is because while driving the noise level (wind,

road, etc.) is louder than while parked. This requires that the

listener constantly adjust the music level to compensate for the

varying noise levels. This is not only a problem for automobiles but virtually all sound systems where background noise

is varying substantially. For example: in a factory setting,

the music would be set to one level while the machinery is

running and another while it is not running. For most systems,

this requires that someone always adjust the level in proportion to the noise. The question naturally arises: “why can’t

this be done automatically?” Mackie Designs has invested

a considerable amount of time in research and development

to nd an answer to this very question. In the process, we

have developed a sophisticated DSP noise sensing algorithm

that will perform this task precisely. Mackie’s SP-DSP1™

is an automatic level controller that maximizes intelligibility

by changing gain in proportion to environmental noise level

changes [6]. Basically, this system senses the level of the

ambient noise of a room and adjusts the system gain accordingly. To work properly, the controller must “null out” any

effect that the program material (music) has on the noise being

received by the ambient microphone. The method we have

employed to differentiate the noise from the program material

is what makes our algorithm unique (patent pending). One

innovative feature of our algorithm is that it adapts over time

to the varying room acoustics (i.e. people, drapes, sliding

doors, etc.) to provide the best possible music rejection. This

signicantly reduces the possibility of “runaway” gain as

exhibited in existing hardware-based implementations [10].

To accomplish this, we have utilized a combination of digital

hardware (SP-DSP1™) running a complex software algorithm

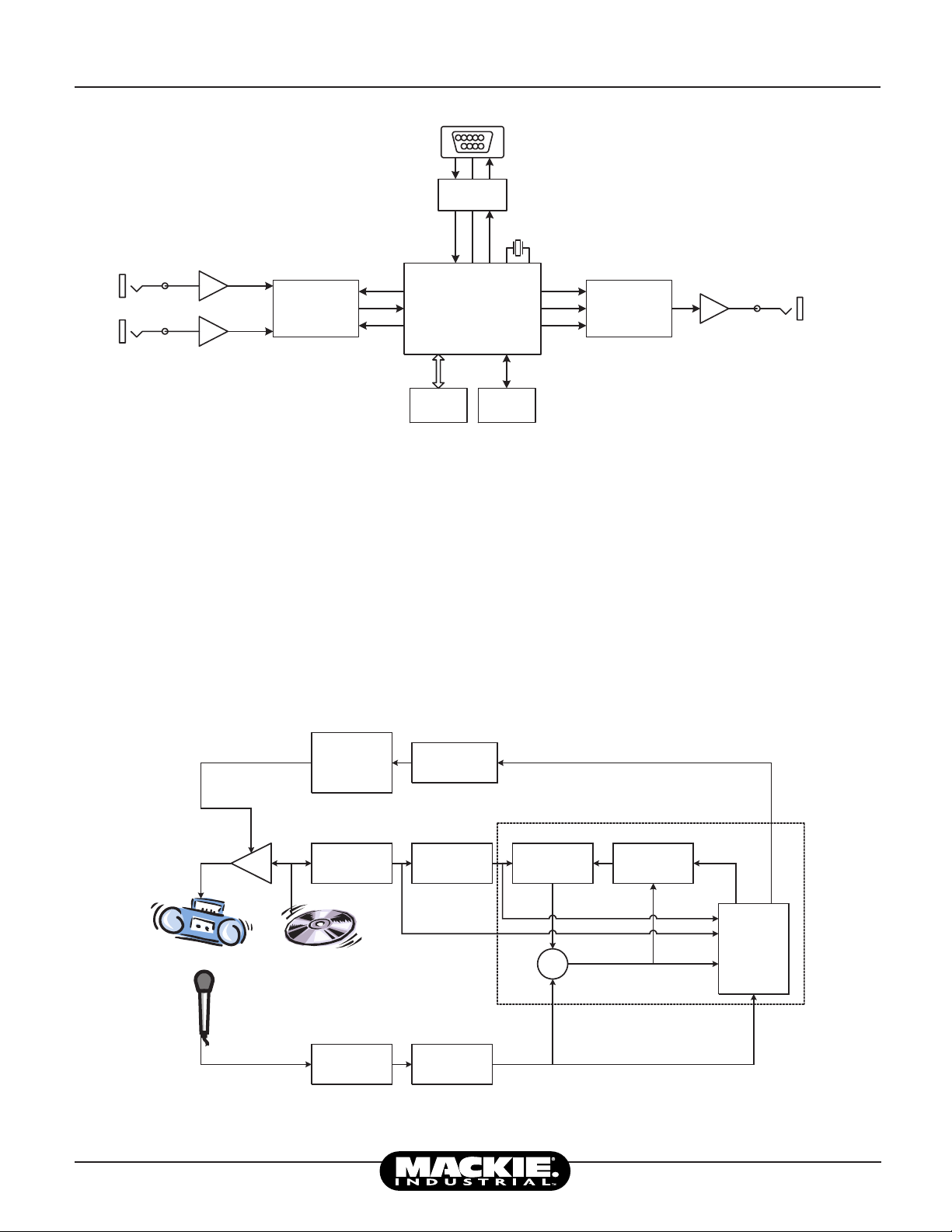

[8]. Figure 0 shows the hardware block diagram of the noise

sensor. The software is actually twofold: an embedded software algorithm plus application software (SP-Control™ for

the Palm™) to allow for ease of user control. Additionally,

the SP-DSP1™ algorithm allows for a high level of automation,

which in-turn, makes this system extremely easy to setup

and use. Unlike some of the earlier attempts at “noise sensing”,

the SP-Control™ software requires no complex procedures

during setup and calibration. The user simply places his speaker(s)

as needed and positions the ambient microphone so that it is

listening to the primary noise source. Then the appropriate

gain structure is setup as well as a few room-specic user

parameters. Finally, while playing music, an Auto Calibration

is initiated. It’s fast and simple!

September 2000

1

Page 2

Mackie Industrial White Paper Noise Sensing

32-bit

Floating-Point

DSP

Stereo

DAC

Stereo

ADC

EPROM

SERIAL

EEPROM

Program Input

Ambient Mic

Input

Program

Output

RX

GND

`

TX

RS-232

TRANS.

RS-232 DSUB9

FIR

Down

Sampler

Down

Sampler

Anti-Alias

Filter

Anti-Alias

Filter

G

RMS

Measure

Coefficient

Calculator

Compander

error

Y

-

+

Noise

Threshold

Override

nLMS Adaptive Filter

Figure 0: Hardware Block Diagram

1 Algorithm Overview

This section summarizes the Ambient Noise Sensing Algorithm

(see Figure 1) implemented in the SP-DSP1™. The algorithm is

used to increase the sensitivity to ambient noise in the room by

rejecting the source signal (music) that is broadcast into the room.

This allows the SP-DSP1™ to control the volume of the music

based on the room ambient noise. The better the rejection of the

music signal the more sensitive the gain control without runaway

gain problems.

The algorithm adapts to the room characteristics by comparing

the room response to the source signal. It computes its own

approximation of the room response in order to cancel the music

signal from the signal picked up by a room microphone [1-5,7].

Room size is the most important factor determining the effectiveness of the algorithm. Small rooms (ofce size) can achieve as

much as 40dB music rejection, while larger rooms (nightclubs

or restaurants) might only achieve 10-20dB. Even 10dB rejection

allows noticeably better sensitivity to noise.

2

Figure 1: Algorithm Block Diagram

September 2000

Page 3

Mackie Industrial White Paper Noise Sensing

1.1 Algorithm Block Diagram

The ambient noise sensor algorithm is a variation of a Normalized LMS Adaptive Filter [2-4, 7, 11-12]. The coefcient

calculator in the system uses the error signal, some Root Mean

Square (RMS) signal levels and energies, and the current coefcients to compute a new set of Finite Impulse Response (FIR)

coefcients that approach the Room Transfer Function (RTF) [5].

Down sampling has been used to optimize the adaptation characteristics of the algorithm for the largest room possible using

minimum MIPS and memory [8, 9]. The compander controls the

gain of the music signal based on the ambient noise detected and

the user input parameters.

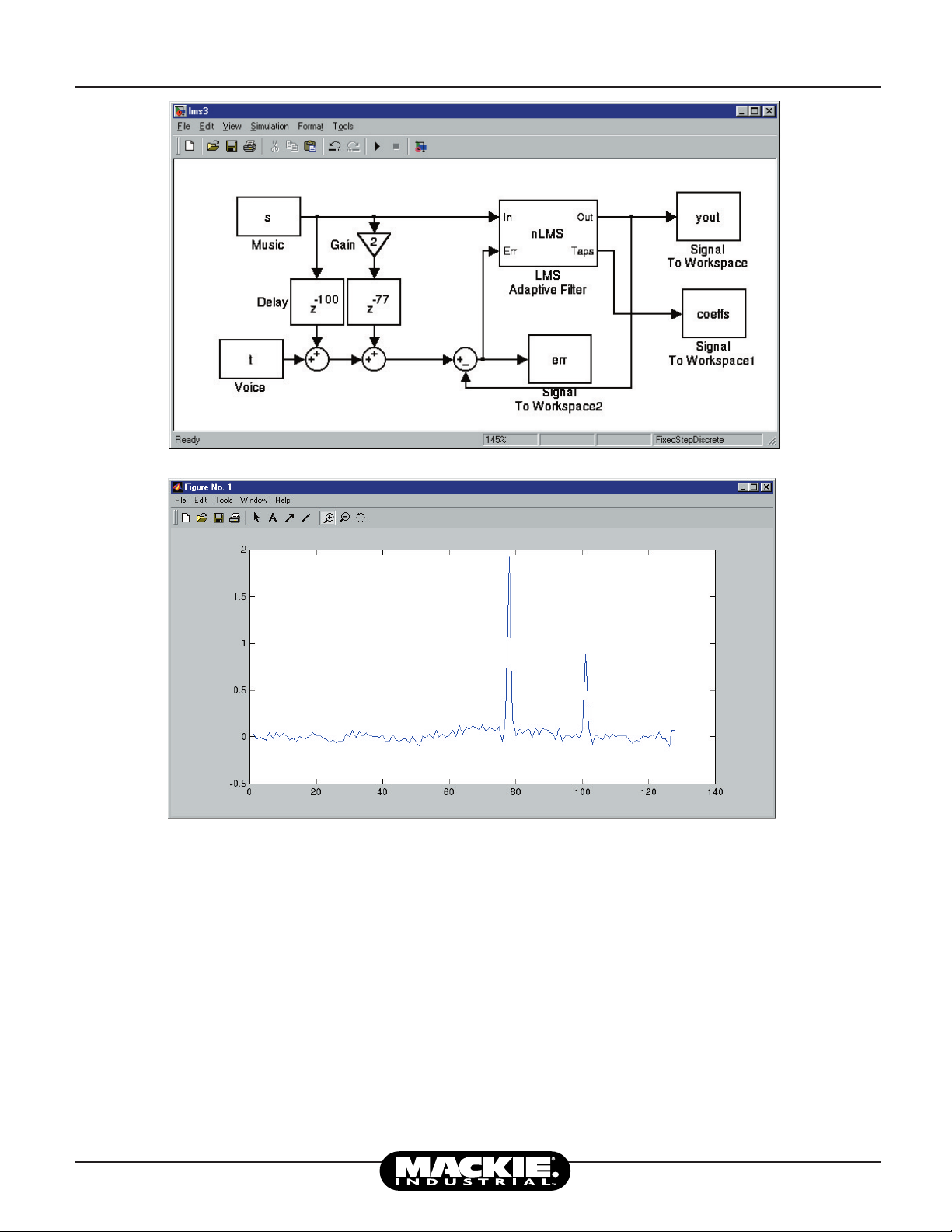

1.2 Normalized LMS Adaptive Filter

The Normalized Least Mean Square (nLMS) Adaptive Filter

portion of the Ambient Noise Sensor consists of the FIR lter

(Equation 1), Coefcient Calculator (Equation 2), Summation

(producing the error signal), and RMS measurements, and can

be considered equivalent to the MATLAB1 simulation shown

in Diagram 1 [1, 9, 10]. In this simulation the ‘Voice’ signal

is the ambient noise signal, the delays represent the RTF, and

the nLMS lter adapts to produce the ‘Out’ signal which

is an approximation of the music combined with the RTF.

When the output signal from the nLMS is subtracted from the

input signal (Voice + RTF (Music)) the ‘err’ or error signal

approximates the original ‘Voice’ or noise signal. Look at

the gains and delays shown in the blocks of Diagram 1 (simulating the direct sound plus one reection). The amplitude

versus time plot was generated with the coefcients from the

‘Taps’ output of nLMS lter. As you can see from this simple

example, this lter is the RTF. Obviously, in the real world,

the exact RTF is not obtainable. However, the better the

FIR approximates the RTF, the closer the error signal is

to the actual noise in the room [2-4, 11-12]. The nLMS Adaptive Filter is constantly adapting to the room characteristics.

This provides optimum performance when the room acoustics

change. Room acoustics can change signicantly due to the

arrangement of furnishings, opening or closing drapes, the

number of people in the room changing, or more dramatic

changes such as moveable walls or room dividers.

The effectiveness of the nLMS is determined mostly by the

number of taps in the FIR (internal to the nLMS adaptive

Filter), the adaptation algorithm, and the density and duration

of the RTF. In the SP-DSP1™ the processing capability and

memory allocation has limited the FIR length to about 1500

taps. As a result, the signals are down sampled to allow for

good cancellation even in reasonably large rooms. Since the

1

MATLAB is the trademark of a comercial matrix-based processing

language.

speed of sound is approximately 1 ft/ms, we designed the

system to provide adequate rejection for music paths (direct

sound plus reections) up to about 300 feet.

A standard Transversal n-point FIR lter was used [1, 5, 8].

Input buffering is n points long plus a little extra buffer space.

The Output, y, forms another buffer:

N-1

y(n) = ∑ w

(n)*u(n-i)

i

i=0

(1)

where

N = number of FIR taps or the order of the lter

n = time index

y = FIR output

w = adaptation coefcients

u = FIR input

Calculation of new coefcients (coefcient calculator) is

performed if the following two conditions are met:

• If the normalization energy is greater than zero (if

negative or 0 it is a debug error condition).

• If the Error Threshold signal is above the threshold

computed as a portion of the normalization energy of the

input signal.

Mathematical calculations for coefcient updating are

according to a slightly modied nLMS formula [2-4, 7,

11-12]:

Wi(n+1) = Wi(n)+ ————————

e(n) * beta * u(n-i)

epsilon * E(n)

(2)

where

n = time index

i = 0..n-1

W = FIR lter coefcients

e = error

u = FIR input data

E = Normalization Energy

beta = adaptation rate (function)

epsilon = stability coefcient

Our slightly different use of beta (not shown) plus the use

of an Error Threshold are unique adaptations of the standard

nLMS algorithm. The new beta function allows faster adaptation when the error, e, gets smaller. The normal use of beta

as a scaling value (shown above) requires a small value to

guarantee stability of the algorithm when the error is large,

September 2000

3

Page 4

Mackie Industrial White Paper Noise Sensing

Diagram 1: Matlab simulation Block Diagram and Results

which signicantly reduced the adaptation amount when the

error was small, extending the adaptation time to well over 30

minutes. Our beta function (patent pending) gives stability to

the algorithm when the error is large, but effectively shortens

the adaptation time dramatically when the error becomes

small. This allows the algorithm to adapt to a room in only

a few minutes.

For small rooms a signicant portion of the music energy due

to the paths from speaker to microphone (including reections) are removed by the nLMS algorithm, as there would

4

have to be many reections before the sound could have traveled this far. Each reection reduces the energy of the music

signal, and the amount of reduction of the energy is related

to the shape and material of the reecting surface. The more

‘live’ the room, the longer and more dense the RTF is, the

less the energy of the music signal that can be removed by the

nLMS lter [6]. Even without a lot of reections a very large

room may have poor cancellation due to the small number of

reections before the music signal has traveled the maximum

‘distance’ of the FIR.

September 2000

Page 5

Mackie Industrial White Paper Noise Sensing

1.3 RMS Measurements

The nLMS algorithm requires normalized energies for calculating the FIR coefcients. A real RMS algorithm is used to

measure the signal levels [2, 4, 11-12]. This is accomplished by

buffering the squares of each sample of the input signal (Square),

averaging the sum of these squares every sample (Mean), and

taking the square root of the mean (Root). For every input sample

an RMS value is produced, which is itself buffered and ltered

by a 256-point window function, to smooth the response of the

detector by a xed known delay and amplitude.

The main benet of ltered RMS measurement is to reduce

the impact of low frequency room energy variations caused by

the music broadcast into the room, which can give variations

in the room energy readings by 2 or 3 dB. This amount of

variation could cause the compander to constantly turn the

volume of the music up and down by a similar amount, which

is quite noticeable and undesirable.

Several RMS detectors are required in the system. The nLMS

Coefcient Calculator requires the energy of the FIR output,

error and music signals. The Compander requires the level of

the music and microphone signals.

1.4 Down Sampling

To extend the effective FIR length for larger rooms the LMS

lter is down sampled from the converter sample rate [8,9]. In

this implementation, 44100 Hz (Fs) is the converter sample rate

for the music and microphone signals. Down sampling also helps

reduce the memory and MIPS requirement. This also has the

effect of comparing energies of signals ltered at half of the

down sampled Nyquist rate. As long as the noise signal has a

proportional amount of its energy in this spectrum, the ambient

noise sensor will approximate the level of the noise signal. As we

have found, this is a valid assumption.

1.5 Compander

User parameters control the operation of the compander.

Minimum Gain, Gain Range, Noise Threshold, Noise Range,

Attack/Release Times, and RMS measurement parameters

determine how much gain (or attenuation) is applied to the

music signal.

The compander Attack and Release parameters control the

rate at which the gain is turned up or down. These are important to control the gain during loud sudden events such as door

slams, yells, or dropped dish trays, which would normally

cause the music level to be turned up very loud. A slow attack

rate (more than 10 seconds) with a faster release rate will

reduce the level of gain applied to the music. This allows the

compander to track the ambient room noise while ‘rejecting’

these singular events if desired.

1.6 Auto-Calibration

The biggest single problem with controlling the music gain based

on the room noise is runaway gain. Runaway gain occurs when

the compander turns up the music volume which is measured

as ‘room noise’, which tells the compander to further increase

the music volume. The compander must have the appropriate

information to prevent this cycle from occuring.

A calibrated algorithm for computing the approximate location at which runaway gain might occur is used as an override

to limit the sensitivity to the room noise. Although the algorithm constantly adapts to the room acoustics it takes a

signicant amount of time for the algorithm to get to its best

approximation of the RTF. Until this point is reached it is

not possible to determine the override conditions required to

prevent runaway gain. This condition would occur every time

the unit was reset (power on/off) were it not for the Auto

Calibration process, and the internal non-volatile storage of

the calibration parameters.

The Auto Calibration uses a real music signal with xed gain

to adapt and monitor the ambient room noise. As long as the

algorithm is making progress towards the RTF it will continue

to adapt and monitor the noise level. During calibration it

is best to have a minimum amount of room noise so that

the algorithm can determine the progress towards the RTF.

Once the progress towards the RTF has slowed signicantly

the current adaptation coefcients are stored and the Noise

Threshold Override is computed. Every time the unit is reset

the calibration coefcients and Noise Threshold Override are

restored. This allows the compander to prevent runaway gain

on reset and during normal operation. The algorithm continues to adapt at all times to keep up with room acoustic

changes, and as long as the room acoustics do not change

drastically the gain should be prevented from running away.

2 Hardware Setup

The SP-DSP1™ was designed to be an expansion card that is

added to our new “SP” or Sound Palette® series mixer/ampliers

(SP2400/1200). These ampliers provide one or two zones of

200 watts per channel in a two-rack-space package. Since the

SP-DSP1™ operates only on a mono program signal, one card

is required per channel. Once the card is installed, the user

needs to connect an ambient microphone to the rear panel of

SP2400/1200. Note that the connection requires a 3.08mm 3-pin

male Phoenix connector (i.e. Euroblock).

September 2000

5

Page 6

Mackie Industrial White Paper Noise Sensing

2.1 Ambient Microphone

Mackie Designs recommends the Mackie Industrial

MT3100® omnidirectional Electret microphone. This is an

excellent multi-standard phantom condenser microphone perfectly suited for noise sensing applications. However, for

many applications, any inexpensive low-impedance, omnidirectional microphone will sufce. An installer may nd that

a directional microphone is better suited for installations in

smaller or noisier rooms. The microphone should be placed

where it can “hear” the ambient noise within the room. This

(direct vibrations) from speaker to microphone should be

avoided as well as placing the microphone away from the

speakers to provide the best noise-to-signal ratio.

3 Palm™ Control

Mackie Designs has designed the SP-DSP1™ to run under the

Palm™ OS or any compatible palmtop device. The SP-Control™ Palm™ application (on 3 1/2 inch disk) is included with

the SP-DSP1™ hardware card and can be downloaded from

our WEB site at www.mackieindustrial.com. All necessary

cabling is provided to install the card into the SP2400/1200.

Additionally, a 3-inch null-modem adapter cable is provided

to connect a standard Palm™ Cradle or the HotSync® Cable

to the 9-pin female D-Sub on the front of the SP2400/1200.

After installing the application to your device, to run the SPControl™ software, simply select the “SP-Control” from the

available applications. You should see the main SP-Control™

window (see Figure 2). The main display has six user parameters and four bar graphs indicating the relevant levels. Because

of limited screen space, we used two-letter symbols designating the parameters and levels. Table 1 summarizes the six

parameter ranges and their default settings after a Factory

Restore.

Figure 2 SP-Control™ Main Screen

does not imply that the SP-DSP1™ can not differentiate

between the noise and the program material. However, to

get the best possible performance and rejection, the ambient

microphone should be placed where it is listening to the

“intended” ambient noise source. Any mechanical feedback

“MG”= “GR”= “NT”= “NR”= Attack/

Min. Gain Gain Range Noise Noise Range Release

(dB) (dB) Threshold (dB) (dB) Time (sec.)

Minimum: -40 0 -80 1 1

Maximum: 0 40 0 60 300

Default: -40 40 -40 40 1

3.1 User Parameters (Sliders)

As the parameter Minimum Gain implies, this is the lowest

level to which the system can attenuate. With this slider

default at –40dB, the system can attenuate the program input

by as much as 40dB. Please note that the SP-DSP1™ can

only attenuate program material that is present on the input.

That is, this system (see Figure 0) will never allow gain from

input to output (≤ 0dB). By setting the Minimum Gain and the

second parameter, Gain Range, you are actually establishing

the program operating window within which the levels for

the program material must remain. For example, if the user

wanted his music levels to operate in a range ±10dB around

-15dB down from the input level, he would set MG =-25dB

and GR=20.

Table 1: SP-Control™ User Parameter Ranges and Defaults

6

September 2000

Page 7

Mackie Industrial White Paper Noise Sensing

+10dB

+5dB

0dB

-5dB

-10dB

-15dB

-20dB

-25dB

-30dB

-40dB

-35dB

-50dB

-45dB

-55dB

-60dB

-65dB

-70dB

-75dB

-80dB

Default setting

Ratio: 1:1

Note: Ratio=Noise:Program

NT=-80

MG=-30

NR

GR

=Program Operating Window

=Noise Window

Unity:

FS:

GR NR

NT=-40MG=-40

Lowest NT, Highest NR

Ratio: 2:1

Sensitive to low noise

GR

NR

NT=-30

MG=-20

GR

NR

NT=-60

MG=-35

Average setting

Ratio: 3:2

Good for small room

Average setting

Ratio: 2:3

More Sens., Larger room

Good starting point

The second parameter, Gain Range, also sets the maximum

gain attainable from the Minimum Gain. That is:

Prog. Operating Window = Min. Gain + Gain Range = Max. Gain

(3)

The Gain Range slider “re-scales” so that system gain (input

to output) is never greater than 0dB. So, if MG =-10dB, then

GR≤10dB. In most cases, the user can ignore the Gain Range

parameter. He would simply set the desired Minimum Gain of

the music (either by listening or from calculation) and leave

the Gain Range at the default “re-scaled” setting.

The third parameter, Noise Threshold, sets the noise “trigger”

of the algorithm. Until the noise level exceeds this threshold,

the throughput program level is unaffected. This slider actually sets the “noise” sensitivity of the algorithm. NT is relative

to the unity point which is –10dBFs (from full scale). Therefore, if NT=-80dB, this would indicate a noise threshold level

of –90dBFs (where Fs = 1V RMS). In simplistic terms, the

lower the Noise Threshold (more negative), the more sensitive

program level changes are to noise level variations. The Noise

Threshold parameter in conjunction with the fourth parameter, Noise Range, actually sets the operating window of the

noise source. This noise “window” sets the level and range

that the noise must be within to effect the program level:

Noise Window = Noise Threshold + Noise Range (4)

The Noise Range setting gives the user control over how much

noise level change causes the program level to span it’s Gain

Range. By setting a small Noise Range (say 20dB) with regard

to the Gain Range (say 30dB), you are allowing a 20dB noise

level change to cause the program output level to span 30dB.

This is assuming that the noise level has crossed the Noise

Threshold. In other words, these settings would represent a

2:3 noise level to program level change (see Chart 1). For

every 2dB change in noise level, the output level changes by

3dB. On the other hand, NR=40 and GR=40 (default settings)

September 2000

Chart 1: Noise Window vs. Program Operating Window Examples

7

Page 8

Mackie Industrial White Paper Noise Sensing

would represent a 1:1 noise level versus program level change.

You can start to see the exibility of this system (see Chart 1).

By having control over the program operating window (MG

and GR) and the noise window (NT and NR), the user can

actually move the noise window with respect to the program

operating window and visa versa. In this way, the system can

be set to be “sensitive” to small noise changes or “insensitive”

to large noise changes and everything in between.

3.2 Attack and Release Parameters

The Attack parameter denes the time, in seconds, it takes for

the Program Gain to increase by 40dB. Likewise, the Release

parameter denes the time it takes for the Program Gain to

decrease by 40dB. The combination of these two parameters

gives the user the ability to “average” the noise to provide

a relatively constant Program Gain over time. Otherwise,

with short attack and release times (i.e. the default settings),

the user will hear every program level shift as it relates to

a specic noise level shift. To keep impulsive noise bursts

from affecting the program level, a good setting would be

an Attack =20 seconds and Release =20 seconds. This would

avoid the impulsive change but would still allow a fairly

“responsive” program level change as it relates to a noise

level change (~40 seconds). In a plant setting where there are

numerous pages and “break time” buzzers, setting the Attack

and Release Time on the order of minutes, will eliminate

program level changes on all but the average long-term noise

level. There may be a situation where you want a long Attack

and a short Release Time or visa versa. For example: in a plant

with background music, equipment may be turned on sequentially (relatively slowly) in the morning but in the evening

all are switched off together. A long Attack but short Release

Time might be advantageous by allowing the music level to

decrease instantly when the noise level fades.

is executed, ensure that the microphone level is within the

range from 0 to –10dB for the loudest noise plus program

expected. On the rear panel of the SP2400/1200 ampliers,

there is an “ambient mic” trim potentiometer. Adjust this trim

potentiometer (0-55dB) to get the proper levels as indicated by

the “MI” meter. Note that the SP-DSP1™ does not have a mic

preamp. Therefore, it is essential that the ambient microphone

input receives a line-level signal (1 V RMS Full-scale). The

third meter from the left as shown on the SP-Control™ screen

is the “PG” meter which is the Program Gain. This meter

represents the gain (0 to 60dB) that algorithm applies to

the Program Input. The last meter is the “PO” which is the

Program Output meter. This is the level at the output of the

SP-DSP1™ (0 to 60dB). The following condition will always

be true:

Prog. Output level = Prog. Input level + Prog. Gain (in dB) (5)

A good way to set the proper “MI” level is to select the Bypass

button on the main screen. Then, while playing typical program

material, adjust the microphone preamp trim potentiometer on

the rear panel of the SP2400/1200 until the “MI” meter is within

0 to –10dB. This allows us to adjust the level while the microphone is “hearing” both the program material plus the noise so

that we do not inadvertently clip the SP-DSP1™ microphone

input during calibration. Clipping the microphone or program

input (ADC) will produce erratic controller behavior and should

be avoided.

3.3 Bar Graphs/Metering

The main screen of the SP-Control™ Palm™ application has

four meters that allow the user to monitor levels during setup

and normal operation (see Figure 2). “PI” is the Program

Input meter and it indicates the input level into the DSP (range

from 0 to 60dB). During setup before Auto Calibration, the

user needs to ensure that the input program source has sufcient signal level by monitoring this meter. The input level

should be between 0 and –10dB during the loudest portions

of the program material. “MI ” is the Microphone Input meter.

This meter indicates the ambient microphone input level in

a range from 0 to 60dB. Again, before an Auto Calibration

8

Figure 3: SP-Control™ Save Conrmation

September 2000

Page 9

Mackie Industrial White Paper Noise Sensing

3.4 Additional Main Screen Options

The main screen of the SP-Control™ also provides the ability

to save and recall 10 presets. These presets are stored in the

EEPROM onboard the SP-DSP1™ (see Figure 3). A preset

consists of the following parameters: Minimum Gain, Gain

Range, Noise Threshold, Noise Range, Attack and Release

Times. There are two Global parameters that are recalled at

power up and displayed when Connect is selected on the main

screen. These include the Bypass state and the CAL or calibration value. Additionally, the preset that was saved or recalled

when the SP-Control™ was last connected will be stored in

the EEPROM and recalled at power up. The CAL value is set

during Auto Calibration and will be discussed in the next section. The Bypass toggle, as its name implies, allows the user

to bypass program input to program output and effectively

disables the algorithm. This is a useful feature during setup

to ensure the proper levels are obtained. Finally, the DSP1/2

toggle allows the user to change between communicating with

DSP1 or DSP2. As you are already aware, the SP2400/1200

can support two SP-DSP1™ cards; one for each zone. Therefore, if your system has two controllers, this toggle allows you

to control each card separately and independently.

tion to ensure that all levels are in their target range as

suggested in Section 3.3 Bar Graphs/Metering. If you nd that

the microphone and input levels are too low or too high, you

may want to Abort the calibration by selecting the appropriate

button and then readjust the levels accordingly. There is also

an End & Save button if the user nds that calibration is

3.5 Auto Calibration

The Drop Menu of the SP-Control™ has several functions

shown in Figure 4. The Auto Calibration provides the user

with the ability to automatically adapt his speaker-microphone

placement to the room acoustics (patent pending). This function eliminates the tedious calibration procedures associated

with other competitor’s products. Additionally, the possibility

of “runaway” system gain is greatly reduced because the algorithm (a modied nLMS adaptive lter) is constantly making

“running” changes to obtain the best noise-to-signal ratio.

To maximize the results, an Auto Calibration should be performed while the room noise is at a minimum. However, since

the algorithm adapts over time, this is not a critical requirement. Once the speaker(s) and ambient microphone are in

their xed locations and the microphone gain and input levels

have been adjusted (per Section 3.3 Bar Graphs/Metering),

simply select Auto Calibration while playing standard program material. Prior to performing the Auto Calibration,

please ensure that the front panel level control on the

SP2400/1200 is set to the maximum sound level that you

would ever expect the system to deliver. Recall that the noise

sensor only attenuates the signal from input to output. During

the calibration, a count-down timer is initiated at 90 seconds

and a progress meter is displayed. If the algorithm nds that

adaptation improvements are possible, the timer is reset to

90 seconds. A typical calibration period is 2-3 minutes. It is

advised to monitor the main four meter levels during calibra-

Figure 4: SP-Control™ Function

taking too long or music breaks are causing count-down timer

resets. Typically, music breaks between songs are no problem.

However, if the break is too long, the calibration may be

ineffective resulting in numerous timer resets. If this becomes

a problem, simply changing to different program material

or using music with shorter pauses between songs should correct the situation. Once the calibration is complete, the CAL

value will update. At default, this value is +10 (range: +20

to –80dBr). This number is a measure of how much of the

program material is getting rejected in the environment that

the Auto Calibration was performed. The closer the number

is to +10, the less rejection. A CAL = -15dBr would be an

excellent rejection and would be expected in a small room.

However, in larger rooms and auditoriums, the rejection will

be less (closer to 0dBr). Remember that this number is only

an estimate of rejection that is used by the algorithm to set the

Noise Threshold Override.

September 2000

9

Page 10

Mackie Industrial White Paper Noise Sensing

3.6 Factory Restore

If you nd that the EEPROM is corrupted or has not been initialized from the factory, you can perform a Factory Restore

upon installing the SP-DSP1™ and running the SP-Control™

application. A new SP-DSP© card should have all parameters

of all presets set to default values (see Table 1).

3.7 Upload/Download From/To EEPROM

Occasionally, it is necessary to backup SP-DSP1™ presets and

parameters or to transfer settings from one DSP to another.

To copy the contents of the EEPROM, simply Connect to

the DSP card and then select Upload From EEPROM. The

EEPROM contents are stored in your Palm™. If you would

like to copy contents of the Palm™ into another SP-DSP1™

card, select the Download To EEPROM. Be advised that this

will completely erase the existing contents of the EEPROM

and replace with what was uploaded to the Palm™. Be careful

to do an Upload From EEPROM before the Download To

EEPROM to ensure that valid data exists in the Palm™.

4 Tips for Setting User Parameters

To clarify, setting the user parameters (MG, GR, NT, NR,

Attack Time and Release Time) can be done either before or

after the Auto Calibration. These parameters have no bearing

on the calibration and can be changed at any point. In fact, a

Preset Save and Recall only affect these parameters.

The Auto Calibration only concerns itself with the Calibration

or CAL value and the adaptation coefcients. The user parameters can be set up for runaway gain, but the user would

notice this immediately as the system would “runaway” to

the maximum gain. During calibration, the user parameters

are temporarily overridden to perform the calibration at a

xed gain (easier and better results). However, the xed gain

used during the calibration process is the Maximum Gain

(Minimum Gain + Gain Range). It is probably advisable for

the user to set up these two parameters so that he isn’t “blown

away” by the calibration sequence if his Maximum Gain is

louder than he intends. The Maximum Gain is used as the

calibration value because the algorithm adapts more quickly

when the music is loud. The calibration itself doesn’t limit

the parameters the user can adjust in any way, it just provides

a ‘hidden override’ when he has his Noise Threshold set too

sensitive, which would otherwise cause runaway. You’ll notice

that once your unit has been calibrated you can set the Noise

Threshold as low as you want and you will still seem to get

the same sensitivity. This is because it is being limited by the

Noise Threshold Override (see Figure 1).

As you can see, one of the rst questions that the end-user

needs to answer is “How much overall system gain or attenuation do you want the noise sensor to provide?” By answering

this question you have determined the setting of the Gain

Range (GR). A typical good starting point for the Gain

Range is about 20dB. If you nd the system does not attenu-

ate enough or attenuates too much, adjust accordingly. By

answering this rst question, you are likely to determine the

Minimum Gain (MG) as well. Since the average user would

want his system to attenuate from the unity point (0dB),

which is the highest sound level he would ever want, for

this example the Minimum Gain would be set to –20dB. As

mentioned in Section 3.1 User Parameters (Sliders), by setting

the Minimum Gain and the second parameter, Gain Range,

you are actually establishing the program operating window

within which the levels for the program material must remain.

As in the previous example, if the user wanted his music levels

to operate in a range ±10dB around -10dB down from the

input level (unity point), he would set MG=-20dB and GR=20.

Setting the Noise Threshold (NT) can only be done by determining the noise level at which you want the music to start

to increase in level. This noise threshold point is best found

through trial and error. You must be careful not to set the

NT too low (i.e. more negative), because the noise sensor will

begin “gaining up” the program material with very little noise.

However, setting the NT too high will prevent the system from

making any program gain increases until there is a relatively

high noise level. There is a balance and each room will require

a different NT setting. Keep in mind that setting this level in

an empty room may require some “tweaks” when the room

is full with people. For example, if you set NT=-40dB in an

empty restaurant, you may nd that the system starts gaining

up too fast and is too loud for the occasion. In this case, you

can reduce NT (by bringing the level closer to 0dB) by 5 to

10dB. This would give you NT=-30 to -35dB and the system

would not start “gaining up” until the noise was 10dB “hotter”

than it was previously.

Noise Range (NR) actually sets the amount of noise that makes

the program gain go from the minimum setting to the maximum setting. That is, if NR=40dB and GR=20dB, then for

every 2dB change in the Noise, the Program level is only

10

September 2000

Page 11

Mackie Industrial White Paper Noise Sensing

changed by 1dB. A good starting point is to set NR equal to

the GR setting. This would give a 1:1 noise to program level

change and would sufce for the majority of installations.

Remember, The Noise Threshold Override will protect the

system from runaway gain even if the NT and NR are set

incorrectly

5 What to Avoid

Once an Auto Calibration has been performed, a user should

never move or change the speaker-microphone placements. In

fact, any changes (i.e. adding more speakers, moving equipment, signicantly changing the room layout, etc.) should

be avoided. If these changes are required, simply recalibrate

by initiating another Auto Calibration. You may nd that in

environments that change daily (new equipment added, equipment moves, etc.) a periodic recalibration would be benecial.

Any gain adjustments made to the microphone preamp should

be done prior to Auto Calibration. Further-more, all level

changes should be made prior to the DSP card. If the system

gain is changed in any way post DSP card, the noise sensor

perceives this as an acoustic noise disturbance. This is why

the level controls on the SP2400/1200 are before the DSP.

Again, any level changes made after the DSP card (i.e. power

amplier, speakers, between the preamp and power amplier,

etc.) will require a recalibration.

6 HyperTerminal Control of SP-DSP1™

If the user does not own a Palm™ or compatible device, he

can use HyperTerminal available on any PC running Windows

OS. HyperTerminal can control all the parameters previously

mentioned. The null-modem adapter is not necessary as the

9-pin female D-Sub on the front of the SP2400/1200 will

connect directly to a PC COMM Port. Mackie Designs will

provide a one-page protocol at the customer’s request.

8 References

[1] Antoniou, A., 1993, Digital Filters: Analysis, Design, and

Applications, 2nd ed., McGraw Hill.

[2] Cowen, C. F. N. and P. M. Grant, 1985, Adaptive Filters,

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

[3] Franklin G. F. and J. D. Powell, 1981, Digital Control of

Dynamic Systems, Reading MA: Addison-Wesley.

[4] Haykin, S., 1986, Adaptive Filter Theory, Englewood

Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

[5] Haykin, S., 1989, Modern Filters, New York: Macmillan.

[6] Hellman, Zwislocki, September 1964, “Loudness Function

of a 1000-cps Tone in the Presence of a Masking Noise”,

Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, v. 36, no. 9, pp.

1618-1627

[7] Morzingo R. A. and T. W. Miller, 1980, Introduction to

Adaptive Arrays, New York: Wiley.

[8] Proakis, J. G. and D.G. Manolakis, 1988, Introduction to

Digital Signal Processing, New York: Macmillan.

[9] Proakis, J. G., 1989, Digital Communications, Chapter 6,

McGraw Hill.

[10] Sondhi, M. M. and D. A. Berkley, August 1980, “Silencing echoes on the telephone network”, Proceedings of the

IEEE, v. 68, no. 8, pp. 948-963.

[11] Treichler, C. R., J. R. Johnson, and M. G. Larimore, 1987,

Theory and Design of Adaptive Filters, New York: Wiley.

[12] Widrow, B. and S. D. Stearns, 1985, Adaptive Signal

Processing, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

7 Patent Protection

The basic principles of noise sensing presented in this paper

are the subject of patent applications.

September 2000

11

Page 12

Mackie Industrial White Paper: Noise Sensing 9/00

THE AUTHORS

Jeff Sondermeyer was born in

Denville, NJ, in 1963. He received his

B. S. in electrical engineering from

Mississippi State University, MS, in

1987 and his M. S. in electrical

engineering from the University of

Colorado, CO, in 1993. His thesis

research was conducted in speech

recognition where a Backpropagation

Neural Network was used to recognize stressed isolated words. During and after his graduate

work, he was a Digital Design Engineer for Peavey Electronics where he designed numerous audio effects processors to

include algorithms for pro audio gear. Presently, he is a Senior

Design Engineer/Digital Design Lead for Mackie Designs

where he has designed the low-cost EMAC multi-effects card

for the PPM and CFX mixers and the DX8; a two-rack 8x2

digital mixer. He is a member of the IEEE and AES.

Dale Shpak was born in Seattle,

WA, in 1957. He received his B. S. elec-

trical engineering from the University

of Calgary, Alta., in 1980 and his

M. S. in electrical engineering (elec-

tronics) from the University of Calgary,

Alta., in 1982. He received a Ph.D.

in electrical engineering from the

University of Victoria, B.C., in 1989.

Presently he is the Vice President of

Software Development with SysCor R&D Inc. He has done

research in digital lter design, signal processing for: audio,

speech, and telecommunications. Additionally he had done

work with networks to include networked Java applications. He

is the author of the DSP Blockset, Signal Processing Toolbox,

and a New Toolbox for Matlab/Simulink. He has numerous

publications in IEEE and one in AES (see: www.ece.uvic.ca/

~dale/cv.pdf). Dr. Shpak is a member of the IEEE.

Brian Roden was born in Ragina,

Sask. Canada, in 1963. He received a

Diploma of Technology in 1983 from

Camosun College, Victoria, Canada

and his Bachelor of Engineering from

University of Victoria, Victoria, B.C.,

Canada. He was previously employed

by IVL Technologies in algorithm

development and DSP implementa-

tion. He co-authored a patent on

Vocal Gender Shifting for IVL Technologies. In 1998, he was

the co-founder of Acuma Labs Inc. and is currently a Senior

Design Engineer.

Chris Jubien was born in Mon-

treal, Canada, in 1967. He received

his B. A. of Science from Waterloo

in 1990 and his M.A. of Science

from the University of Victoria,

B.C., Canada, in 1993. Previously he

work for IVL Technologies in algorithm development and audio effects

design. Presently he is the DSP man-

ager for Acuma Labs Inc. of which he

co-founded in 1998. His passion is real-time DSP algorithm

and effects development and has a strong interest in using

cutting edge technology to create new sounds and products.

Costa Lakoumentas comes from

Vancouver, British Columbia, where

he lived for 29 years. From 1981 until

1999, he owned two sound contracting businesses and represented nearly

all of the leaders in the pro-audio

industry. Joining Mackie Designs

Inc. in 1999, he was responsible

for the development and launch of

the company’s new Mackie Industrial

division. Mr Lakoumentas is currently Vice President of Business Development at Mackie Designs and is responsible for

all product concept and product development activities at the

Company.

12

Loading...

Loading...