Page 1

Success is a question

of attitude

ErgoHandbook™

Page 2

Page 3

ErgoHandbook™, Leica Microsystems Ltd

Contents

Section

The purpose of this handbook 1

What do you mean by ergonomics ? 2

Ergonomics applied to improving microscopy workstations 3

Ergonomics, illustrations and tables 4

Assessment of the workplace 5

Why invest in ergonomics? 6

Dimensions with Leica ergonomics modules 7

Want to know more about ergonomics? 8

Agencies 9

Questionnaire about the ergonomic arrangement

of the workplace 10

Current publicity material 11

– Fax order form

Page 4

Page 5

ErgoHandbook™, Leica Microsystems Ltd – Section 1 – The purpose of this handbook 1

1. The purpose of this handbook

For an employee to feel "at home" while at work,

ergonomic (human-engineered) workstations

and work sequences are essential. They increase motivation and lead to improved performance. Ergonomics, properly applied, brings higher

productivity and increased profits.

Any works doctor with experience in this field

will tell you that workstations equipped with

optical instruments can bring with them a host of

medical problems, particularly as regards postural strain and eyestrain. The ergonomics of video

display terminals have been widely discussed in

the press, but it is less well known that workstations which include a microscope put considerably higher demands on the user.

The intention of this handbook is to make you

more familiar with the importance of ergonomic

microscopy workstations and with their advantages, to set out the basic principles of ergonomics, and to show you how to arrange your

workstation to ensure minimum stress. Leica

has given more thought than any other stereomicroscope manufacturer to this subject and

has introduced the world's widest range of

ergonomic accessories. This fact gives Leica a

considerable advantage, particularly in view of

the increasing strictness with which the product-liability laws are being applied (see inset).

Ignoring or neglecting basic ergonomic rules can cost plenty.

Government sources in the USA put a price label of a hundred

thousand million dollars on the annual cost to the U.S. economy of unsatisfactory ergonomics. Escalating claims for

damages are pushing the authorities to introduce legislation.

In a widely-publicized legal case, three female employees successfully sued the manufacturer of their computer keyboards

for damages running into millions of dollars. Working at the

keyboard had caused damage to the fingers, the wrist and the

arm. This verdict affects not only the computer industry, but

also other industrial activities. Many manufacturers will now

have to come to grips with ergonomic facts and to introduce

appropriate measures, because the Brooklyn court declared

industry to be liable for the damage caused by its products.

This specific legal case, together with calculations showing

that injury due to repetitive movement is costing the U.S. health

organizations $20,000 million a year , have driven the authorities

to force the introduction of ergonomic product design by

means of appropriate legislation. In November 1996, California

became the first state in the USA to introduce a law to this

effect.

from USA TODAY, 9. January 1997

An actual example

Page 6

ErgoHandbook™, Leica Microsystems Ltd – Section 1 – The purpose of this handbook2

Page 7

ErgoHandbook™, Leica Microsystems Ltd – Section 2 – What do you mean by ergonomics? 1

2. What do you mean by

ergonomics?

The term ‘Ergonomics’ is derived from the Greek words ergos meaning "work" and nomos meaning "natural laws of" or "study of".

‘ergon’= work and ‘nomos’= according to statutes

Ergonomics investigates and analyzes the relationship between

people and their work, with the aim of improving the performance

of the entire work system and of reducing the negative impact on

the individual. Industrial ergonomics involves the systematic

technical equipping of workplaces and the effect on the person

working there. It is the task of ergonomics to derive rules for

fitting the task to the person.

Human engineering and

ergonomics

Starting with the foundations laid by the work of

Taylor in the field of scientific business management, the science of "human factors" or "human

engineering" has arisen, and is well established

in Europe and in the USA. This new science is in

harmony with the mechanistic views of the 19th

century, which claim that the laws of classical

physics can be applied to all natural phenomena, including human life (refer in this connection to Releaux and to the psychophysics of

Fechner).

Core definition of human engineering according

to the German "Gesellschaft für Arbeitswissenschaft"

Human engineering is the systematic analysis,

ordering and arrangement of the technical,

organizational and social conditions relating to

work processes. Its purpose is to ensure that

employees engaged in productive and efficient

work processes

• work under safe, achievable conditions,

• see that appropriate social standards regarding work content, work analysis, work environment, remuneration and cooperation are

being met,

• have room for manoeuvre, have the opportunity to learn and, in cooperation with others, can

preserve and further develop their personalities.

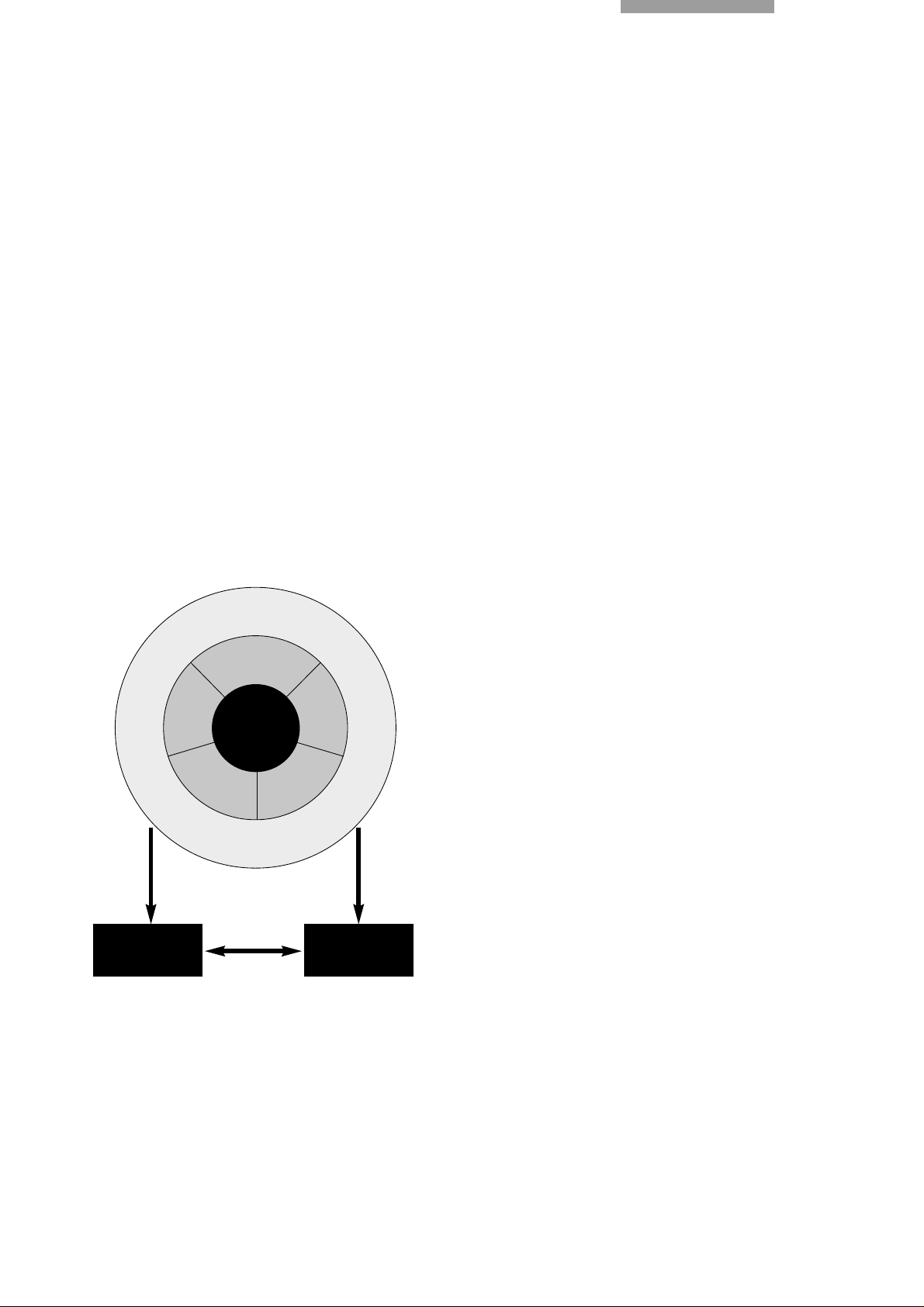

This "ergonomic wheel diagram" includes all of the factors which affect the wellbeing of the employee and which therefore impact on the profitability of the

business. The individual and the task are at the centre. The inner circle (activities)

includes the dynamic ergonomic processes which directly affect the fields in the

outer circle (reaction).

Diagram from: Ergonomics, a success factor for every organization.

Swiss Accident Insurance (SUVA)

Human /

task

Safety at work

Economics

Health protection

Motivation

Human

Work

environ-

ment

Work

content

Work

organization

Work-

place

Well-being at

the workplace

Good

results

Page 8

ErgoHandbook™, Leica Microsystems Ltd – Section 2 – What do you mean by ergonomics?2

In 1857, the Polish investigator Wojciech

Jastrzebowski coined the word "ergonomics" to

denote a branch of science covering certain

aspects of man-machine interaction, but the

term did not become generally accepted at that

time.

In 1949, scientific co-workers of Murell re-introduced the word to denote a new branch of

science researching the capabilities and

properties of humans when using technical

equipment. The stated purpose was to establish

facts enabling proposals to be formulated for the

design of tools, instruments and machines. The

roots of this research originated during the

Second World War, when both the Allies and the

Germans carried out investigations which were

considered to be so important that they should

be applied to civilian activities.

The main task of ergonomics is to reduce the

stress on the human operator while improving

the performance of the entire work system.

These goals are achieved by analyzing the task,

the working environment and the interplay

between human and machine. (Schmidtke,

1993).

Human engineering is multidisciplinary. It derives its basic principles from the human sciences, from engineering, from economics and from

the social sciences. It includes the disciplines of

medicine, psychology, teaching, technology and

law insofar as they all relate to occupational

aspects, and it also embraces industrial sociology. Each of these disciplines is concerned with

human work as seen from the point of view of

the particular aspect science. For the purposes

of practical applicability, this basic knowledge is

combined into what are known as praxeologies

(practical aspects). Of these, organization

theory is primarily social-centred; it provides the

guidelines for organization and for working

groups, whereas ergonomics is more engineering-centred and has the goal of providing guidelines for the technical planning of workplaces

and tools (Luczak and Volpert, 1987).

Free translation of an extract from the brochure of the

Institute for Ergonomics, Technical University, Munich,

Germany

http://www.lfe.mw.tu-muenchen.de/wasist.html

References

Bubb, H. und Schmidtke, H.:

Systemstruktur. In H. Schmidtke

(Hrsg.): Ergonomie.

Hilf, H.: Einführung in die

Arbeitswissenschaft.

Luczak, H., Volpert, W., Raithel, A. &

Schwier, W.: Arbeitswissenschaftliche

Kerndefinition, Gegenstandskatalog,

Forschungsgebiete.

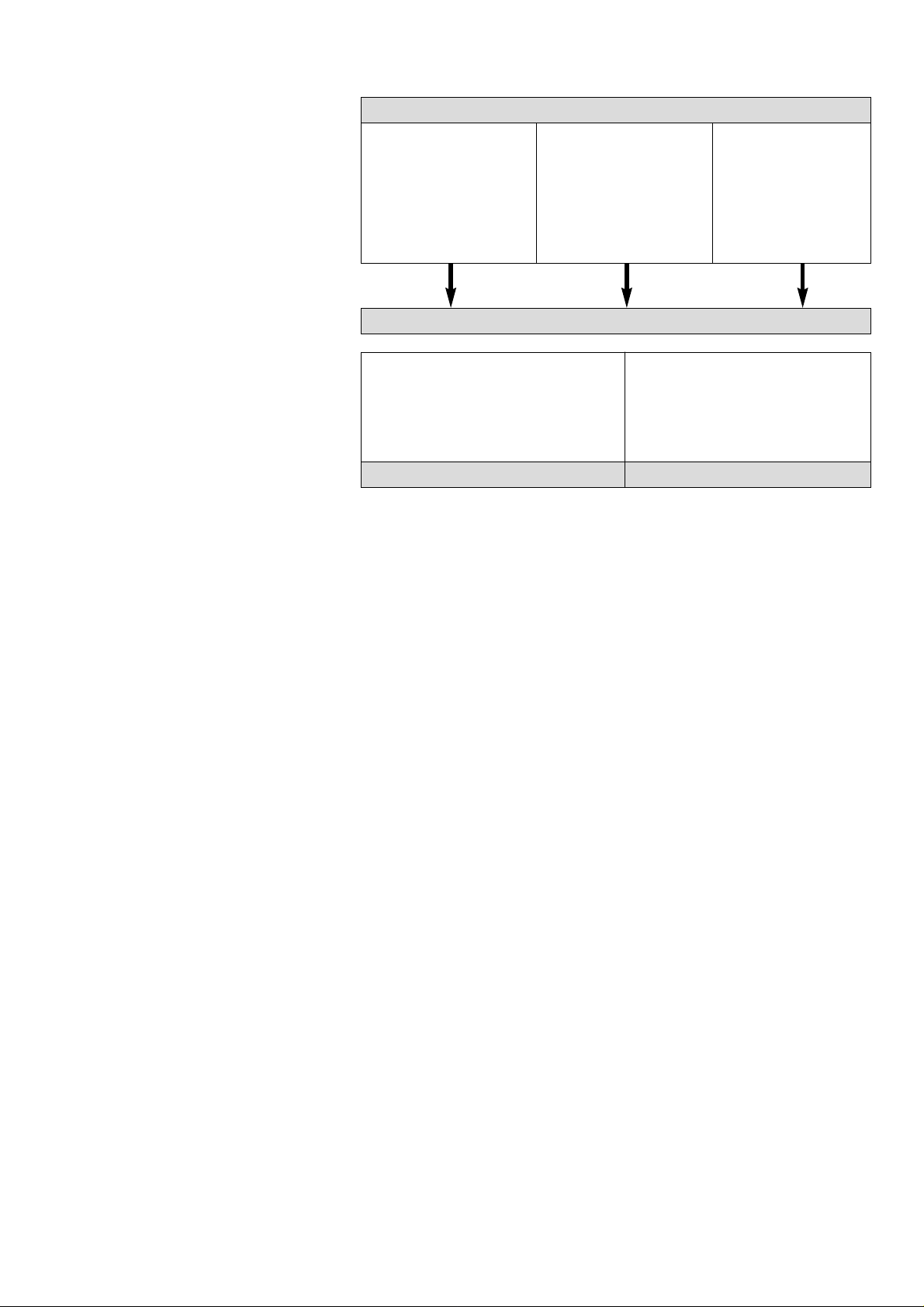

Human engineering and its constituents

Theoretical aspects

Human sciences

– Medicine

– Psychology

– Sociology

– Teaching

Engineering

– Physics

– Construction

– Measurement and

control technology

Economics and

social science

– Economics

– Law

Ergonomics.

Oriented to engineering.

Guidelines for planning tools and

workstations.

Organization of work.

Oriented to the social sciences.

Guidelines for planning operations

and working groups.

Human engineering

Practical aspects

Page 9

ErgoHandbook™, Leica Microsystems Ltd – Section 3 – Ergonomics applied to improving microscopy workstations 1

3. Ergonomics applied to

improving microscopy

workstations

Ergonomics is just a craze. Ergonomics in the

workplace is only a luxury, something for lazy

and difficult people.

Prejudices like these still crop up now and

again. They are based on false information or on

ignorance, because it has been long confirmed

by many investigations in occupational medicine

the world over that ergonomics, scientifically

applied in the workplace, directly affects not

only the individual well-being of employees, but

also their performance and therefore the profits

of the business.

Workstations equipped with optical aids such as

the microscope make seeing easier, but when

used continuously for many hours a day they

place enormous demands on the eyes, the musculo-skeletal system and the powers of

concentration (see fig. 2, section 4). These

demands are considerably greater than those

associated with VDUs, but the latter have received much greater publicity. The present section

is directed primarily towards users of optical

aids and to those responsible for procuring and

installing microscopy workstations. It includes

suggestions for reducing the health risk by

means of:

• ergonomic instruments

• ergonomic workstations

• variety within the work process

• the introduction of work breaks

• appropriately-qualified personnel

• training for users

• problem-awareness in the user.

People are very different

There are tall and short people, some slimmer

than others. This makes workplace requirements into a personal matter. For example, the

existing height of a microscope equipped for a

certain task with accessories and with a particular working distance may be quite unsuitable

for the specific user . Aches and pains, and reduced performance, are inevitable. If the viewing

height is too low, the observer will be forced to

bend forward while working, with resulting muscular tension in the neck region. In the ideal

microscope, therefore, the viewing height and

the viewing angle should be adjustable to the

build of the user. In addition, a variable viewing

height is the best way to prevent an entirelysedentary posture (see fig. 1, section 4). It permits the observer to adopt a personal sitting

posture and to change it periodically in accordance with the natural urge to shift around from

time to time. It is true that the height of the chair

can be altered so that a relaxed, slightly-bent

posture is substituted for the previous rigidlyupright one (see fig. 3, section 4), but this is not

the best approach. It is much simpler and more

comfortable to use a variable binocular tube in

order to compensate for the height difference.

Page 10

ErgoHandbook™, Leica Microsystems Ltd – Section 3 – Ergonomics applied to improving microscopy workstations2

Dynamic sitting reduces to a

minimum the stresses placed

on the back muscles, putting a

stop to the decrease in performance and staving off the

onset of fatigue (see fig. 4, section 4).

All controls ready at hand

Two conditions must be met for frequently-used

controls such as the zoom and focus to be used

comfortably. Firstly, these controls must be as

far down as possible on the microscope and

secondly, it must be possible to operate them

with the forearms supported and the shoulders

relaxed. To avoid unnecessary stress to the

shoulder girdle, the need to stretch out the arms

too far should be avoided. Ergonomically, this

means that the best posture is with the arms

horizontal or sloping slightly downwards, and

with the hands resting on their edges. The drive

knobs should be neither too slack nor too tight;

ideally, their ease of movement should be adjustable to individual requirements. For higher

magnifications there should be a fine-focus

mechanism.

About the chair and the table

Ergonomics at the workplace naturally relates

not only to the instrument itself, but also to the

chair and table which are used. The limited

adjustment possibilities of the instrument itself

can accommodate the finer ergonomic tuning,

but first the chair and table must be chosen and

arranged so as to meet the more basic ergonomic requirements. Their height and their tilt must

ensure that the whole person, from head to foot,

including back, head, arms, hands and legs, can

sit and work in the best possible posture.

Because microscopical observation generally

extends over a considerable period of time, and

requires great concentration, the posture is

decisive. In general, the ideal in terms of relaxed

and comfortable sitting is offered by a microscopy table with adjustable height and which offers

a sufficiently-large surface on which to rest the

hands, combined with a chair which is adaptable to the build of the user and which should

have a tall backrest tiltable backwards by up to

30° (see fig. 6, 7, section 4). If the task requires

the user to lean forwards, this forward tilt should

not exceed 20°.

Special arm- and hand supports

To carry out the fine movements required to

position, manipulate and prepare objects, support should be provided by arm- and handrests

which have no sharp edges. The base of the

microscope stand itself can be designed to provide this support. The elbow joint should not be

supported. It is also important that ancillary tools

such as soldering irons are designed adequately; they should not be too heavy, and neither

should they force the hand to adopt an unfavourable position.

About the optical systems

The literature of occupational medicine contains

the results of numerous investigations into

eyestrain resulting from microscopical observation. A discussion of this aspect requires a specialized knowledge of the properties of optical

instruments and of illumination technology, and

is outside the scope of the present handbook.

One important fact is however this: An

elaborate lens system is more expensive, but in

the long term it pays off because it protects the

eyes and reduces fatigue. High-quality microscopes have optical and mechanical properties

which simple instruments cannot offer.

Examples are parfocality, which eliminates the

constant need to refocus; and plano objectives,

which produce an image which is sharp right to

the edge and not (as with simpler objectives)

either in the middle or in the peripheral area.

The eyepiece: right next to the user

In every microscope, the eyepieces have a very

important function, because they represent the

visual interface to the user. Wide-field eyepie-

ces for spectacle wearers, and

with dioptric correction and

adjustable eyepieces, are particularly recommended. "Wide field"

means that these eyepieces show

a larger area of the object at any

one time, which makes long-term

observation more effective on

account of easier navigation and

because the eye does not need to

adapt so much. Eyepieces for spectacle wearers have a high eyepoint, well away from the

eyelens of the eyepiece, and so present the option of working with spectacles or without. The

eyecups keep out stray light from the side, and

prevent disturbing reflections on the eyelens.

Page 11

ErgoHandbook™, Leica Microsystems Ltd – Section 3 – Ergonomics applied to improving microscopy workstations 3

A few words about the work environment

Performance and work satisfaction depend not

only on the ergonomics of the workstation, but

also on the position of that workstation within

the room. Temperature, humidity, light, noise,

vibration and pollutants all have an immediate

effect on the well-being and productivity of

operators. For example, matching the room

brightness and the microscope-field brightness

to one another makes a major contribution to

reducing strain on the eyes. The illumination

provided by these sources should be uniform,

and moderately bright. Avoid reflections, flickering and dazzling; all of these can result in premature fatigue.

Pauses for thought

Variety is the spice of life. In this context, job

rotation is a good way of avoiding muscular problems. It is a good idea to alternate frequently

between various different microscopical tasks

and, if possible, to intersperse these tasks with

others which do not require the microscope. If

these options are not available, the daily working hours at the microscope should be restricted and the operator encouraged to take fre-

quent breaks of appropriate

length. It is known that eyes

and muscles can recover

quickly under these conditions.

If these deliberate breaks in

work are accompanied by physical exercises, work takes on

a new dimension.

Microscopy is not for everybody

Those who work at the microscope carry a high

responsibility, whether they are in the research

laboratory or in industrial quality assurance. A

lot is expected of their expertise, their powers of

concentration and their attention to detail.

Microscope operators need to be selected partly on the basis of their eyesight and of the capabilities of their musculo-skeletal systems. Fine

work with the stereomicroscope needs good

eyes and steady hands. The tendency to trembling is an important example; it depends on individual makeup, on health and on age. Persons

with back problems, arthritis, sinovial inflammation, carpal syndrome or peripheral circulation

problems are likely to have considerable

problems. Difficulties are also to be expected

with overweight persons, because the distance

between the eye and the eyepiece cannot be

changed.

More training means less troubles

The more demanding the task, the more comprehensive the training required for it. Thorough

instruction for working with the microscope

should include ergonomic aspects, work planning and optical considerations. Continuous

monitoring and advice from the field of occupational medicine are also very important. The key

to minimizing bodily and optical difficulties in

microscopical work is to know, and to practise to know what can be done to arrange and organize a workstation as well as possible, to apply

that knowledge, and to repeatedly practise routine microscope adjustments such as dioptric

setting, focusing, and the resetting of the illumination, until they become second nature.

A healthy approach brings success

The life style and personal attitudes of the individual affect the subjective perception of stress.

Too little sleep, the taking of medicines and the

use of coffee, tobacco and alcohol, can all reduce the visual power. They can all lead to an

increase in hand tremor, as can energetic sport

immediately before working with the microscope. On the other hand, regular and reasonable

exercise in the form of sport during leisure time

is to be encouraged as a means of improving

health generally and of preventing the deterioration of muscles and joints.

To summarize:

Ergonomics is not a slogan; it is a fundamental

theme which relates to the well-being of the

individual when at work. If basic ergonomic

principles are followed during the creation of

microscopical workstations, health problems

are less likely to arise. As many as possible of

the parameters involved need to be matched to

one another so that the individual can work productively and without making mistakes, and so

that eyes and muscles are not overtaxed. Each

person has a different bodily build, and each

activity has its own specific requirements.

Page 12

ErgoHandbook™, Leica Microsystems Ltd – Section 3 – Ergonomics applied to improving microscopy workstations4

Consequently every workstation must be considered separately and equipped individually.

The assessment needs to be

repeated at regular intervals.

The optimization process

covers not only the workstation

itself, but also the content and organization of

the work, and the optical aid itself. To implement

these points successfully, the person responsible needs a sound specialized knowledge of

the physiology of vision and of body motoricity.

Finally, it must be emphasized that the initial high

capital outlay invested in ergonomic workplaces

and tooling pays for itself very quickly and brings

long-term benefits for all concerned - through

better performance, a higher-quality end product, and a lower failure rate.

Page 13

ErgoHandbook™, Leica Microsystems Ltd – Section 4 – Ergonomics, illustrations and tables 1

4. Ergonomics, illustrations

and tables

Diagrams from: Physiologische Arbeitsgestaltung, Etienne Grandjean.

Dynamic and static exertion

- Dynamic exertion is characterized by rhythmic tensioning and

relaxation. The blood circulation is enhanced, particularly in the

muscles, and waste products are washed away. Dynamic exertion can be continued for very long periods at an appropriate

rhythm before the first signs of fatigue appear.

- Static exertion (microscopy is an example) is characterized by

tensioning of the muscles over long periods. The blood circulation is at a low level. Little or no sugar or oxygen is supplied to

the muscles. Waste products are not washed away; instead

they trigger the pain of muscle fatigue. For this reason, we cannot tolerate static exertion for very long without introducing

some movement.

Fig .1

The effect of dynamic exertion on blood circulation in the muscles is

analogous to that of a motor pump. By contrast, static exertion leads to

restriction of the blood circulation.

Bodily complaints

Static exertion and inappropriate planning of the workplace lead to an increased incidence of back trouble and of

pain in the neck, shoulders,

knees and feet.

Fig. 2

Bodily complaints resulting from a

sedentary posture

Contraction Relaxation

Direction of blood flow

Restriction of blood flow

Page 14

ErgoHandbook™, Leica Microsystems Ltd – Section 4 – Ergonomics, illustrations and tables2

Sitting upright, sitting relaxed

– Sitting upright tensions the back muscles.

– With a relaxed sitting posture, with the body

leaning slightly forwards, the weight of the

trunk is in equilibrium and over the long term

the back muscles are used less.

Fig. 3

Sitting upright, sitting relaxed

Pressure on intervertebral disks

– When the trunk is relaxed and

inclined slightly backwards, the pressure on

the intervertebral disks is minimized.

– The pressure on the intervertebral disks is less

for backrests which are convex in the lumbar

region than it is for straight ones.

Fig. 4

The influence of various sitting postures on the pressure

applied to intervertebral disks.

Lumbar vertebrae L3/L4. Mpa = 10.2kp/cm2

Back relaxed

Writing position

Work at the typewriter

Lifting

Pressure on intervertebral disks L3/L

4

Page 15

ErgoHandbook™, Leica Microsystems Ltd – Section 4 – Ergonomics, illustrations and tables 3

Body dimensions

To ensure a natural posture (position of trunk,

arms and legs) it is essential to match the workplace to the build of the individual, and for this

purpose it is necessary to know body dimensions. The extreme range of body dimensions

displayed among members of different sexes

and races, and among individuals within a category, presents great difficulties in this respect.

Fig. 5

Average values for the body dimensions of individuals

within one Swiss industrial organization.

Chair and table

A tall backrest, slightly concave towards the

top and markedly convex in the lumbar region,

provokes less muscular tension, subjects the

intervertebral disks to a minimum of pressure,

and causes the minimum of back problems.

Fig. 6

Favourable dimensions for chairs, tables and footrests

Fig. 7

If the backrest is tilted slightly backwards

(by about 25° to 30°),

the pressure on the intervertebral disks

is minimized.

Length of forearm

and hand together

Men 47.5

Women 43.8

Length of upper arm

Men 36.3

Women 33.7

Back of knee to sole

of foot

Men 45.4

Women 37.4

Back of knee

to spine

Men 46.8

Women 46.6

Knee height

Men 52.5

Women 47.1

Page 16

ErgoHandbook™, Leica Microsystems Ltd – Section 4 – Ergonomics, illustrations and tables4

Angle of observation

The working area which is constantly inspected

with the eyes must be positioned so that the

observer has a comfortable head posture. An

angle of observation which is inclined too

steeply upwards or downwards will cause neck

fatigue in due course.

Fig. 8

Favourable angle of observation

Posture

An observation tube with variable viewing can

be matched to the build of the user, who can

then change position at intervals while working

(dynamic sitting).

Fig. 9

Relaxed body and head, arms comfortably

supported, adequate space for the legs,

good use of the chair.

Page 17

ErgoHandbook™, Leica Microsystems Ltd – Section 4 – Ergonomics, illustrations and tables 5

Monotonous work

Monotony is the reaction of a person to conditions which exhibit little change and offer little stimulation. Examples

are easy activities which extend over a long period, or a situation which changes only very occasionally. The main

symptoms of monotony are fatigue, sleepiness, apathy, and decreasing alertness.

Monotonous repetitive work as seen from the viewpoint of various sciences

As seen by Possible consequences

Medicine Atrophy of mental and physical organic systems

Occupational physiology Monotony; risk of mistakes and accidents

Occupational psychology Decrease in work satisfaction

Ethics Obstacle to self-development

Human engineering Increased absenteeism, increased difficulties in recruiting personnel

Precision work

Work beneath the microscope requires rapid and small muscle contractions, coordination and precision in muscle

movements, concentration, and visual inspection.

Making procedures easier during precision work

Procedure Measures taken

Perception Work accompanied by visual inspection.

Optimization of visual inspection procedure.

Clear understanding of task.

Adequate light and colour.

Alertness Screening-out of distractions. Protection against noise.

Clear arrangement of workplace.

Logical organization of work.

Sequence of movements Work rhythms.

Only one operation at any one time.

Ergonomic arrangement of working area.

Optimization of work operations.

Page 18

ErgoHandbook™, Leica Microsystems Ltd – Section 4 – Ergonomics, illustrations and tables6

Page 19

ErgoHandbook™, Leica Microsystems Ltd – Section 5 – The Leica ergonomics program 1

5. Assessment of the workplace

Quality is the starting-point for

ergonomics

•

Leica possesses the ISO 9001 certificate,

which confirms that quality management and

quality systems are of a very high level.

•

A high standard of quality and reliability ensures that the stringent demands imposed by

product-liability regulations are met, helps to

minimize risks, and leads to a reduction in

costs.

•

A high level of functionality, absolute reliability and long life, even under extreme conditions, lead to a reduction in future investment

costs.

•

Comprehensive user-friendly product documentation, didactically structured and in

accordance with product-liability requirements, simplifies and shortens the training

period, helps to answer queries arising during

the use of the product, and provides confidence.

•

The presence of a Leica customer service in

more than 100 countries ensures competent

advice and quick service.

Leica

ISO 9001

TQM

Minimizing the strain placed on the stereomicroscope user by the

static posture has long been one of our most important goals. The

user of a Leica stereomicroscope has access to the world's greatest variety of binocular tubes and ergonomics modules, and can

therefore adopt the most comfortable sitting posture and change

this at any time. Compulsion to use one pre-ordered posture is

superseded by a dynamic and less stressful sitting position.

Page 20

ErgoHandbook™, Leica Microsystems Ltd – Section 5 – The Leica ergonomics program2

Leica Design

by Ernest Igl/Christophe Apothéloz

The optical system, the basis for

ergonomic working

•

Design principle - one main objective and two parallel beam

paths - for fatigue-free viewing.

•

High-quality optical glass, multiple-coated for bright and crisp

images.

•

High resolution to enable the finest details to be seen better.

•

Pronounced stereoscopic effect for better perception of depth.

•

Less focusing required, thanks to profound depth of field.

•

Perfectly-matched optical components for parfocality (constant

image sharpness from the lowest magnification to the highest).

•

Large fields of view for a better overall impression of the object.

•

Plano objectives for crisp imaging over the entire field of view.

•

Planapochromatic objectives for the contrast-rich, colour-true

rendering of the finest details.

Page 21

ErgoHandbook™, Leica Microsystems Ltd – Section 5 – The Leica ergonomics program 3

For ergonomic viewing

ErgoTubes™ and ErgoModules™ are usable

with all current and past models of Leica Series

M stereomicroscopes.

® The ‘US Patent and Trademark Office’ entered

the trademarks ErgoWedge, ErgoHandbook,

ErgoTube and ErgoModule in the Principal

Register on 23. February 1999 under the following numbers:

ErgoWedge® Reg. No. 2,228,097

ErgoHandbook® Reg. No. 2,223,420

ErgoTube® Reg. No. 2,270,645

ErgoModule® Reg. No. 2,225,687

The entries remain in force for ten years.

The variable ones

ErgoTube™ 10°-50°

Stock no. 10 445 822

Observation tube with viewing angle continuously

variable between 10° and 50°.

Low viewing angle, long overhang.

Improved viewing conditions for tall and short users and with

various outfits.

Apochromatically corrected.

Manufactured from antistatic material.

ErgoWedge™ 5°-25°

Stock no. 10 446 123

An intermediate piece which enables the viewing angle of the

binocular tube used to be changed continuously within the

range 5° - 25°. The eyepieces are displaced towards the

observer by up to 65mm. Improved viewing conditions with

various binocular tubes. Manufactured from antistatic material.

ErgoModule™ 30mm to 120mm

Stock no. 10 446 171

The ErgoModule™ 30mm to 120mm makes low-built

stereomicroscopes taller, enabling users with different

builds to use the same instrument and to adjust the viewing

height accordingly.

Manufactured from antistatic material.

Page 22

ErgoHandbook™, Leica Microsystems Ltd – Section 5 – The Leica ergonomics program4

The higher ones

ErgoModule™ 50mm

Stock no. 10 446 170

A fixed intermediate piece which increases by 50mm the

viewing height of the binocular tube used. Better viewing

conditions for tall observers when using low outfits.

Straight binocular tube

Stock no. 10 429 783

Provides horizontal viewing if the stereomicroscope is fitted

in a tilted position to the swinging-arm stand or to a bonder.

Higher and closer

ErgoTube™ 45°

Stock no. 10 446 253

Erect body position, because the viewing point is

displaced 65mm upwards and 65mm towards the

observer. Interpupillary distance up to 90mm,

magnification factor 1.6x.

Page 23

ErgoHandbook™, Leica Microsystems Ltd – Section 5 – The Leica ergonomics program 5

The low ones

Trinocular video-/phototube

Stock no. 10 445 924, 50% or 10 446 229, 100%

Combined tube for observation and photography, with low

viewing height. Improved viewing conditions for

photographing in combination with accessories.

Inclined binocular tube, low

Stock no. 10 429 781

Low viewing height for stereomicroscope outfits which are

tall because they have a transmitted-light stand or are

equipped with a video-/phototube, a drawing tube,

a coaxial illuminator etc.

High and low

ErgoWedge™ ±15°

Stock no. 10 346 910

A fixed intermediate piece with which the angular tilt range

of the various binocular tubes can be extended by 15° both

upwards and downwards. Improved viewing conditions

with various outfits.

Page 24

ErgoHandbook™, Leica Microsystems Ltd – Section 5 – The Leica ergonomics program6

Standard

Inclined binocular tube 45°

Stock no. 10 445 619

Binocular tube with 45° viewing angle, for standard

outfits. Fits to ErgoModules and to accessories such

as a video-/phototube, a drawing tube, or a coaxial

illuminator.

For competitors’ instruments

Tube adapter

Stock no. 10 446 251 Tube adapter for Nikon

10 446 250 Tube adapter for Olympus

Adaptation of the Leica ErgoTube™ 10°- 50° or of the

ErgoWedge™ 5° - 25° to fit on Nikon and Olympus

stereomicroscopes. Better viewing comfort for the customers of our competitors as well.

Page 25

ErgoHandbook™, Leica Microsystems Ltd – Section 5 – The Leica ergonomics program 7

Wide-field eyepieces for spectacle wearers,

distortion-free

Stock no. 10 445 111 (10x), 10 445 301 (16x)

10 445 302 (25x), 10 445 303 (40x)

Usable either with spectacles or without, adjustable

eyecups, distortion-free imaging.

Dioptric settings adjustable within the range +5 to -5.

Rotatable optics carrier

Leica MS5, MZ6, MZ75, MZ95, MZ125, MZ APO

Optics carrier rotatable 360° in microscope carrier.

Direction of viewing is matched to work situation.

Comfortable observation without twisting the head.

Page 26

ErgoHandbook™, Leica Microsystems Ltd – Section 5 – The Leica ergonomics program8

For ergonomic operation

Motor-focus system

Stock no. 10 446 176 MF drive with column and with

transformer for transmitted-light bases

10 446 259 MF drive with inclinable column and

with transformer for swinging-arm /

table clamp stand

Effortless operation with hand control or footswitch, or

through computer.

Use of the footswitch leaves the hands free for manipulation.

Increased flexibility as regards the working position.

The same ease of movement in both directions of adjustment,

even with heavy outfits.

Rapid travel to stored positions saves time.

Focusing drive

Stock no. 10 445 615 (300mm)

10 446 100 (500mm)

Ease of movement individually adjustable

Low, bilateral drive knobs

Comfortable use with hands supported

Focusing drive, coarse/fine

Stock no. 10 445 616 (300mm)

Fine focusing for high magnifications

Low, bilateral drive knobs

Comfortable use with hands supported

Focusing drive, coarse/fine, for 50mm diameter

columns

Stock no. 10 445 629

Coarse / fine focusing

Bilateral drive knobs

Easy movement even with heavy outfits

Page 27

ErgoHandbook™, Leica Microsystems Ltd – Section 5 – The Leica ergonomics program 9

Microscope carrier

Stock no. 10 445 617

Microscope carrier mountable in two basic positions (low

and high) in accordance with object size and working

distance. The focusing drive can always be placed in an

ergonomically-favourable position.

Incident-light stands

Stock no. 10 445 631 (large)

13 445 630 (small)

Pleasant supporting surface for the hands

Large stage insert, diameter 120mm

Page 28

ErgoHandbook™, Leica Microsystems Ltd – Section 5 – The Leica ergonomics program10

Transmitted-light stands

Stock no. 10 445 387 (bright field)

13 445 363 (bright-/dark field)

Pleasant supporting surface for the hands

Large stage insert, diameter 120mm. Long overhang

(120mm) between column and optical axis.

Comfortable manipulation of larger objects.

Comfortable stages

Stock no. 10 446 301 Gliding stage

Makes it easier to manipulate the object.

Careful displacement of the object.

Usable on incident- and transmitted-light stands, with

black/white stage insert, glass stage plate or cup stage.

Stock no. 10 446 303 Cup stage

A holder for petri dishes.

Rubber surface for pinning plant and insect specimens.

The stage is tiltable, facilitating the observation of spatial

objects from all sides.

Page 29

ErgoHandbook™, Leica Microsystems Ltd – Section 5 – The Leica ergonomics program 11

Ergonomic outfits

LEICA MZ6 stereomicroscope with ErgoWedge™ 5° - 25°,

positions 25° and 5°

ErgoTube™

10° - 50°

ErgoWedge™

5° - 25°

Page 30

ErgoHandbook™, Leica Microsystems Ltd – Section 5 – The Leica ergonomics program12

Ergo-Module™ 30 bis 120mm

ErgoWedge™ ±15°

LEICA MS5 stereomicroscope with ErgoModule™ 50mm

Page 31

ErgoHandbook™, Leica Microsystems Ltd – Section 5 – The Leica ergonomics program 13

LEICA MZ6 stereomicroscope with ErgoTube™ 45°

LEICA MZ12 stereomicroscope with trinocular

video-/phototube

Loading...

Loading...