Page 1

Programming Guide

HP

83751A/B

and HP

Synthesized Sweeper

83752A/B

Page 2

HP

part number: 83750-90005

Master set: 83750-90002

Printed in USA March 1997

Serial Numbers.

Supersedes: October 1994

This manual applies directly to instruments with serial

prel% 3447A

and

below.

This manual also applies to firmware revision 2.0 and above. For

Grmware

revisions below 2.0 contact your nearest Hewlett-Packard service center for a

firmware upgrade.

Notice.

The information contained in this document is subject to change without

notice.

Hewlett-Packard makes no warranty of any

ldnd

with regard to this material,

including but not limited to, the implied warranties of merchantability and

fitness for a particular purpose. Hewlett-Packard shall not be liable for errors

contained herein or for incidental or consequential damages in connection

with the furnishing, performance, or use of this material.

@Copyright Hewlett-Packard Company

All

Rights

Reserved. Reproduction, adaptation, or translation without prior

1993,1997

written permission is prohibited, except as allowed under the copyright laws.

1400 Fountaingrove Parkway, Santa Rosa, CA 95403-1799, USA

Page 3

Certification

Hewlett-Packard Company certifies that this product met its published

specifications

further certifies that its calibration measurements are traceable to the United

States National Institute of Standards and Technology, to the extent allowed

by the Institute’s calibration facility, and to the calibration facilities of other

International Standards Organization members.

Regulatory Information.

at the time of shipment from the factory. Hewlett-Packard

The User’s Guide contains

SCPI Conformance Information is found in Chapter 5, “SCPI Conformance

Information.

”

ISO/IEC

regulatory information.

. . .

ill

Page 4

Warranty

This Hewlett-Packard instrument product is warranted against defects in

material and workmanship for a period of one year from date of shipment.

During the warranty period, Hewlett-Packard Company will, at its option,

either repair or replace products which prove to be defective.

For warranty service or repair, this product must be returned to a service

facility designated by Hewlett-Packard. Buyer shall prepay shipping charges

to Hewlett-Packard and Hewlett-Packard shall pay shipping charges to return

the product to Buyer. However, Buyer shah pay

and taxes for products returned to Hewlett-Packard from another country.

alI

shipping charges, duties,

Hewlett-Packard warrants that its software and

Hewlett-Packard for use with an instrument will execute its programming

instructions when properly installed on that instrument. Hewlett-Packard

does not warrant that the operation of the instrument, or software, or

Ermware will be uninterrupted or error-free.

LIMITATION OF WARRANTY

The foregoing warranty shah not apply to defects resulting from improper

or inadequate maintenance by Buyer, Buyer-supplied software or

interfacing, unauthorized modification or misuse, operation outside of the

environmental specifications for the product, or improper site preparation

or maintenance.

NO OTHER WARRANTY IS EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED. HEWLETT-PACKARD

SPECIFICALLY DISCLAIMS THE IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF

MERCHANTABILITY AND FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE.

EXCLUSIVE REMEDIES

THE REMEDIES PROVIDED HEREIN ARE BUYER’S SOLE AND EXCLUSIVE

REMEDIES. HEWLETT-PACKARD SHALL NOT BE LIABLE FOR ANY

DIRECT, INDIRECT, SPECIAL, INCIDENTAL, OR CONSEQUENTIAL

DAMAGES, WHETHER BASED ON CONTRACT, TORT, OR ANY OTHER

LEGAL THEORY.

firmware

designated by

iv

Page 5

Assistance

Product maintenance agreements and other customer assistance agreements

are available

Fbr any assistance, contact your nearest Hewlett-Packard Sales and service

Ome.

for

Hewlett-Packard products.

V

Page 6

Safety Notes

The following safety notes are used throughout this manual. Familiarize

yourself with each of the notes and its meaning before operating this

instrument.

CAUTION

WARNING

The caution note denotes a hazard. It calls attention to a procedure which,

if not correctly performed or adhered to, could result in damage to or

destruction of the instrument. Do not proceed beyond a caution note until

the indicated conditions are fully understood and met.

The warning note denotes a hazard. It calls attention to a procedure

which, if not correctly performed or adhered to, could result in injury or

loss of life. Do not proceed beyond a

warnzing

note until the indicated

conditions are fully understood and met.

Instruction The instruction manual symbol. The product is marked with this symbol when it is necessary

Manual

for the user to refer to the instructions in the manual.

vi

Page 7

General Safety Considerations

WARNING

WARNING

CAUTION

Before this instrument is switched on, make sure it has been properly

grounded through the protective conductor of the ac power cable to a

socket outlet provided with protective earth contact.

Any interruption of the protective (grounding) conductor, inside or

outside the instrument, or disconnection of the protective earth terminal

can result in personal injury.

There are many points in the instrument which can, if contacted, cause

personal injury. Be extremely careful.

Any adjustments or service procedures that require operation of the

instrument with protective covers removed should be performed only by

trained service personnel.

Before this

instrument is switched on, make sure its primary power circuitry

has been adapted to the voltage of the ac power source.

Failure to set the ac power input to the correct voltage could cause damage to

the instrument when the ac power cable is plugged in.

Vii

Page 8

How to Use This Guide

This guide uses the following conventions.

(Front-Panel

Sof

Screen Text

K~-J

tkey

This represents a key physically located on the instrument.

This indicates a “softkey, II a key whose label is determined

by the instrument’s

This indicates text displayed on the instrument’s screen.

firmware.

Vlll

. . .

Page 9

Contents

1. Getting Started Programming

HP-IB General Information

Interconnecting Cables

Instrument Addresses

HP-IB Instrument Nomenclature

Listener

Talker

Controller

Programming the Sweeper

HP-IB Command Statements

Abort

Related statements used by some computers

Remote

Some BASIC examples

Local

Lockout

A BASIC example

Local

Some BASIC examples

Clear

Some BASIC examples

Related statements used by some computers

output

A BASIC example

Related statements used by some computers

Enter

Related statements used by some computers

Getting Started with SCPI

Definitions of Terms

Standard Notation

Command Mnemonics

Angle Brackets

How to Use Examples

Command Examples

Response Examples

Essentials for Beginners

Program and Response Messages

....................

.....................

...................

......................

.....................

...................

................

......................

......................

......................

................

......................

.................

.................

.................

..............

...............

...............

..........

.............

............

....

..............

..............

..............

....

....

....

..............

..............

...............

...............

...............

...............

..........

l-3

l-3

1-3

l-4

l-4

l-4

l-4

l-4

l-5

l-6

l-6

l-7

l-7

l-8

l-8

l-8

1-8

l-9

l-9

l-9

l-10

l-11

l-11

l-12

1-13

1-14

l-15

1-16

l-16

l-16

l-16

l-17

1-17

l-18

l-19

Contents- 1

Page 10

Forgiving Listening and Precise Talking

Types of Commands

Subsystem Command Trees

The Command Tree Structure

Paths Through the Command Tree

Subsystem Command Tables

Reading the Command Table

More About Commands

Query and Event Commands

Implied Commands

Optional Parameters

Program Message Examples

Example 1

Example 2

Example 3

Example 4

Parameter Types

Numeric Parameters

Extended Numeric Parameters

Discrete Parameters

Boolean Parameters

Reading Instrument Errors

Example Programs

Example Program

Program Comments

Details of Commands and Responses

Program Message Syntax

SCPI Subsystem Command Syntax

Common Command Syntax

Response Message Syntax

SCPI Data Types

Parameter Types

Numeric Parameters

Extended Numeric Parameters

Discrete Parameters

Boolean Parameters

Response Data Types

Real Response Data

Integer Response Data

Discrete Response Data

String Response Data

...................

...................

...................

...................

................

.............

............

...........

..............

...........

...............

...............

............

.................

...............

...............

...............

.............

................

................

...............

..............

.............

.............

.................

.................

...............

...............

...............

...............

...............

..............

.............

..............

......

..........

........

..........

..........

.........

..........

1-19

l-19

1-21

l-21

1-21

l-24

l-25

l-26

l-26

l-26

l-26

l-27

l-27

l-27

l-28

l-28

l-29

l-29

l-30

l-31

l-31

1-32

l-33

l-33

l-35

l-36

l-37

l-38

l-39

l-40

1-41

l-42

1-42

l-43

l-44

l-44

l-45

l-45

l-45

1-46

l-46

Contents-2

Page 11

Programming Typical Measurements

Using the Example

Use of the Command Tables

HP-IB Check, Example Program 1

Program Comments

Local Lockout Demonstration, Example Program

Program Comments

Setting Up A Typical Sweep, Example Program 3 .

Program Comments

Queries, Example Program 4

Program Comments

Saving and Recalling States, Example Program 5

Program Comments

Looping and Synchronization, Example Program 6 .

Program Comments

Using the

Program Comments

Using the User Flatness Correction Commands,

*WA1

Example Program 8

Programming the Status System

General Status Register Model

Condition Register

Transition Filter

Event Register

Enable Register

An Example Sequence

HP 83750 Series Status Register Model

Synthesized Sweeper Status Groups

The Status Byte

The Standard Event Status Group

The Standard Operation Status Group

The Questionable Data Status Group

Status Register System Programming Example

Programming the Trigger System

Generalized Trigger Model

Description of Triggering in Sweepers

Advanced Trigger Configurations

Trigger Keyword Definitions

ABORt

IMMediate

SOURce

Programs

.............

.............

.............

.............

.............

.............

Command, Example Program 7

.............

..............

.............

..............

...............

...............

............

Group

..................

.................

..................

...........

...........

........

...........

..........

........

..........

.........

.........

......

.......

.......

.....

.....

.........

......

.......

..........

l-47

l-47

. .

. .

. .

. .

2

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

.

. .

. .

. .

. .

.

. .

l-48

l-51

l-51

l-52

l-53

l-54

l-55

l-56

l-56

l-58

l-59

l-60

l-61

l-62

1-63

l-64

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

.

. .

. .

. .

1-68

l-69

l-69

l-70

l-70

l-70

l-71

l-72

l-72

l-72

l-74

1-75

l-76

l-77

l-80

l-80

l-82

l-83

. .

. .

. .

. .

l-84

l-84

l-84

l-84

Contents-3

Page 12

Related Documents . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.

Programming Commands

Command Syntax

IEEE 488.2 Common Commands

*CLS

(Clear Status Command)

*DMC (Define Macro Command)

*EMC (Enable Macros Command)

Query Syntax

*ESE (Standard Event Status Enable Command)

Query Syntax

*ESR? (Standard Event Status Register Query)

*GMC? (Get Macro Contents Query)

‘IDN?

(Identification Query)

*LMC? (List Macro Query)

*LRN? (Learn Device Setup Query)

*OPC (Operation Complete Command)

Query Syntax

*OPT? (Option Identification Query)

*PMC (Purge Macros Command)

*PSC (Power-On Status Clear Command)

Example

Query Syntax

*RCL (Recall Command)

*RMC (Remove Macro Command)

*RST (Reset Command)

*SAV (Save Command)

*SRE (Service Request Enable Command)

Query Syntax

*STB? (Read Status Byte Query)

*TRG (Trigger Command)

*TST? (Self-Test Query)

*WA1

(Wait-to-Continue Command)

Subsystem Commands

ABORt

AM:STAT; : : : : : : : : : : : : :

Query Syntax

AM:SOURce

Query Syntax

Calibration Subsystem

CALibration:PEAKing

..................

...........

...........

..........

.........

..................

..................

........

............

.............

.........

.......

..................

........

..........

......

....................

..................

..............

.........

..............

..............

......

..................

..........

.............

..............

.........

................

.......

.......

..................

...................

..................

................

...............

...

....

l-85

2-3

2-4

2-4

2-4

2-5

2-5

2-5

2-5

2-5

2-6

2-6

2-6

2-6

2-7

2-7

2-7

2-8

2-8

2-8

2-8

2-9

2-9

2-9

2-9

2-10

2-10

2-10

2-10

2-11

2-11

2-12

2-12

2-12

2-12

2-13

2-13

2-14

2-14

Contents-4

Page 13

Query Syntax

CA.Libration:

CALibration:PMETer:FLATness:INITiate?

CALibration:PMETer:FLATness:NEXT?

Correction Subsystem

CORRection:FLATness:FREQ

Query Syntax

CORRection:FLATness:AMPL

Query Syntax

CORRection:FLATness:POINts?

CORRection[:STATe]

Query Syntax

CORRection:VOLTs:SCALe

Query Syntax

CORRection:VOLTs:OFFSet

Query Syntax

Diagnostic Subsystem

DIAG:LRNS?

DIAGnostic:TEST:FULLtest?

DIAGnostic:TEST:FULLtest:REPort?

Display Subsystem

DISPlay[:STATe]

Query Syntax

FM Subsystem

FM:COUPling

Query Syntax

FM:STATe

Query Syntax

FM:SENSitivity

Query Syntax

FM:SOURce

Query Syntax

Frequency Subsystem

FREQuency:CENTer

Query Syntax

Example 1

Example 2

Example 3

FREQuency[:CW[:FIXed]

Query Syntax

..................

TRACk

....................

..................

................

...........

..................

...........

..................

..........

...............

..................

............

..................

............

..................

................

...................

............

.................

.................

..................

...................

..................

..................

..................

..................

..................

...................

..................

................

...............

..................

...................

...................

...................

.............

..................

......

.......

........

2-14

2-14

2-15

2-15

2-16

2-16

2-16

2-17

2-17

2-17

2-18

%2:

2-18

2-19

%l:

2-20

2-20

2-21

2-22

2-22

2-22

2-23

2-23

2-23

2-23

%2:

i:?t

2-24

2-25

2-25

,2:2:

2-26

2-26

2-27

2-27

Contents-5

Page 14

FREQuency[:CW]:AUTO and

FREQuency[:FIXed]:AUTO

Query Syntax

FREQuency:MANual

Query Syntax

FREQuency:MODE

Query Syntax

FREQuency:MULTiplier

Query Syntax

FREQuency:MULTiplier:STATe

Query Syntax

FREQuency:OFFSet

Query Syntax

FREQuency:OFFSet:STATe

Query Syntax

FREQuency:SPAN

Query Syntax

FREQuency:STARt

Query Syntax

FREQuency:STEP[:INCRement]

Query Syntax

FREQuency:STOP

Query Syntax

Triggering in the Sweeper

1NITiate:CONTinuous

Query Syntax

INITiate[:IMMediate]

Marker Subsystem

MARKer[n]:AMPLitude

Query Syntax

MARKer[n]:AOFF

MARKer[n]:FREQuency

Query Syntax

MARKer[n]:MODE

Query Syntax

MARKer[n]:REFerence

Query Syntax

MARKer[n][:STATe]

Query Syntax

Memory Subsystem

MEMory:RAM:INITialize

...................

...............

..................

................

..................

..................

..................

................

..................

..................

................

..................

................

..................

..................

................

..................

..............

...............

..................

...............

..................

..............

..................

.................

..............

...................

................

..................

...............

..................

................

..................

.................

...........

..............

...........

............

..........

.............

2-27

2-27

2-28

22:

2::

22:

,22::

22;

22:

Z3:

i-g:

-

23:

22:

2-36

f3:

2-37

2-37

22:

2-39

22-i:

-

;!:I

i1&;

22:

2-43

Contents-6

Page 15

Output Subsystem

OUTPut

:

STATe

Query Syntax

OUTPut:IMPedance?

Power Subsystem

POWer:ALC:CFACtor

Query Syntax

POWer:ALC:SOURce

Query Syntax

POWer:ALC[:STATe]

Query Syntax

POWer:ATTenuation

Query Syntax

......

........

......

...

......

...

......

...

......

...

......

...

......

POWer:ATTenuation:AUTO

Query Syntax

POWer:CENTer

Query Syntax

POWer[:LEVel]

Query Syntax

......

......

......

......

......

POWer:MODE FIXedlSWEep

Query Syntax

POWer:OFFSet

Query Syntax

POWer:OFFSet:STATe

Query Syntax

POWer:SLOPe

Query Syntax

POWer:SLOPe:STATe

Query Syntax

POWer:SPAN

Query Syntax

POWer:STARt

Query Syntax

POWer:STATe

Query Syntax

......

......

......

...

......

......

......

...

......

.......

......

......

......

......

......

POWer:STEP[:INCRement] .

Query Syntax

POWer:STOP

Query Syntax

Pulse Subsystem

PULSe:PER.iod

......

.......

......

......

......

. . . . . . . . . . . .

............

............

............

............

............

............

............

............

............

............

............

............

............

............

............

............

............

...........

............

............

............

............

............

............

............

............

............

............

............

............

............

............

............

............

............

............

............

. . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . .

2-44

2-44

2-44

2-44

2-45

2-45

2-45

2-45

2-45

2-46

2-46

2-46

2-46

2-47

2-47

2-48

2-48

2-49

2-49

2-49

2-49

2-50

2-50

2-50

2-50

2-51

2-51

2-51

2-51

2-52

2-52

2-52

2-52

2-53

2-53

2-53

2-53

2-54

2-54

2-55

2-55

Contents-7

Page 16

Query Syntax

PULSe:FREQuency

Query Syntax

PULSe:WIDTh

Query Syntax

PULM:SOURce

Query Syntax

PULM:STATe

Query Syntax

ROSCillator:SOURce

Query Syntax

ROSCillator:SOURce:AUTO

Query Syntax

Status Subsystem

STATus:OPERation:CONDition?

STATus:OPERation:ENABle

Query Syntax

STATus:OPERation[:EVENt]?

STATus:OPERation:NTRansition

Query Syntax

STATus:OPERation:PTRansition

Query Syntax

STATUS:PRESet

STATus:QUEStionable:CONDition?

STATus:QUEStionable:ENABle

Query Syntax

STATus:QUEStionable[:EVENt]?

STATus:QUEStionable:NTRansition

Query Syntax

STATus:QUEStionable:PTRansition

Query Syntax

Sweep Subsystem

SWEep:CONTrol:TYPE

Query Syntax

SWEep:DWELl

Query Syntax

SWEep:DWELl:AUTO

Query Syntax

SWEep:POINts

Query Syntax

SWEep:POWer:STEP

..................

..................

..................

..................

..................

..................

..................

...................

..................

...............

..................

..................

..................

..................

..................

..................

.................

..................

..................

..................

..................

..............

..................

..................

..................

...............

..................

..................

..................

...............

............

..........

............

...........

..........

..........

.........

...........

..........

.........

.........

2-55

2-56

%2:

ir$;

%g;

%2;

%?-?i

E1z5

2-59

2-59

C&i

2-60

iI%:

%&I

2-61

2-61

24:

2-62

;-$

-

&2:

2-64

%2:

%2;

irEg

22::;

Contents-8

Page 17

Query

SWEep[

Query Syntax

SWEep:TIME

Query Syntax

SWEep:TIME:AUTO

Query Syntax

SWEep:TIME:LLIMit

Query Syntax

SWEep:GENeration

Query Syntax

SWEep:MODE

Query Syntax

SWEep:MANud[:RELative]

Query Syntax

SWEep:MANual:POINt

Query Syntax

SWEep:MARKer:STATe

Query Syntax

SWEep:MARKer:XFER

SWEep[:POINts]:TRIGger:SOURce

Query Syntax

SWEep:POINts:TRIGger:

System Subsystem

SYSTem:ALTernate

Query Syntax

SYSTem:ALTernate:STATe

Query Syntax

SYSTem:COMMunicate:GPIB:ADDRess

SYSTem:COMMunicate:PMETer:ADDRess

Query Syntax

SYSTem:COMMunicate:PMETer:TYPE

Query Syntax

SYSTem:ERRor?

SYSTem:KEY[:CODE]

Query Syntax

SYSTem:KEY:DISable

Query Syntax

SYSTem:KEY:ENABle

SYSTem:LANGuage

Query Syntax

Syntax

:FREQuency]:STEP

..................

..............

..................

...................

..................

...............

..................

...............

..................

................

..................

..................

..................

............

..................

..............

..................

..............

..................

..............

..................

.............

..................

................

..................

.............

..................

..................

..................

.................

...............

..................

...............

..................

...............

................

..................

.........

.......

......

.......

2-6’7

2-68

2-68

2-69

;I;;

%V7:

i-7’:

-

.22;;

;I;;

%??i

t1;f

%2t

2-75

%ZE

2-76

2-76

%2:

%2;

2-77

i:?i

i-;i

-

2-79

2-79

2-81

“2::;

2-82

2-82

Contents-9

Page 18

SYSTem:PRESet[:EXECute]

SYSTem:PRESet:SAVE

SYSTem:PRESet:TYPE . .

Query Syntax . . . . . .

SYSTem:SECurity:CLEar .

SYSTem:SECurity:COUNt .

SYSTem:SECurity:KLOCk .

SYSTem:SECurity:ZERO . .

SYSTem:VERSion? . . . .

Trigger Subsystem . . . . . .

TRIGger[:IMMediate] . . .

TRIGger:SOURce . . . . .

Query Syntax . . . . . .

TSWeep

HP

3.

835OB

Introduction

Data

Input Syntax

Function Codes (Prefix Active)

Numeric Value (Numeric Format)

Numeric Terminators

Valid Characters

Instrument Preset

Output Data

Learn String

Mode String

Interrogate Function

Active Function

Status

Trigger

Input Programming Codes

Clear

Remote/Local Changes

Service Request

Status Byte

Status Bit

Pass Control

Abort

Interface Function Codes

HP 83750 Series Status Byte Descriptions

. . . . . . . . .

Compatibility Guide

....................

........................

...................

....................

...................

...................

..................

......................

.......................

.......................

...................

.....................

.....................

....................

.......................

. . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . .

............

............

............

............

............

............

............

............

............

............

............

. . . . . . . . . . . .

...........

..........

...............

.................

.................

................

.............

................

...............

......

2-82

2-82

2-83

2-83

2-83

2-84

2-84

2-84

2-85

2-86

2-86

2-87

2-87

2-88

3-1

3-l

3-1

3-2

3-2

3-3

3-3

3-4

3-4

3-5

3-6

3-13

3-13

3-14

3-14

3-15

3-22

3-22

3-23

3-24

3-24

3-24

3-24

3-25

3-26

Contents-10

Page 19

4. Error Messages

:ERRor?

SYSTem:ERRor

The Error/Event Queue

Error numbers

No Error

SCPI Error Messages

Error Message Description

Example Error

Command Error

......................

Execution Error

Device-Specific Error

Query

Instrument Specific Error Messages

Block Transfer Errors

Bus Control Errors

Parsing and Compatibility Errors

Diagnostics and Self-Test Errors

Internal Hardware Errors

Hardware Configuration Errors

Calibration Routine Errors

Loops Unlocked Errors

Miscellaneous Hardware Dependent Errors

Error

................

...............

...................

................

.............

.................

..................

..................

................

....................

.........

...............

................

..........

...........

..............

...........

.............

...............

......

4-3

4-4

4-5

4-5

4-6

4-6

4-6

4-8

4-14

4-20

4-22

4-24

4-24

4-25

4-26

4-29

4-33

4-33

4-34

4-36

4-37

5. SCPI Conformance Information

SCPI Conformance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Index

5-3

Contents-l

1

Page 20

Figures

l-l. SCPI Command Types

l-2.

A Simplified Command Tree

l-3.

Proper Use of the Colon and Semicolon

l-4. Simplified SWEep

l-5. Voltage Controlled Oscillator Test

l-6.

Simplified Program Message Syntax

l-7.

SCPI

l-8. Simpliiied

l-9.

Simplified Response Message Syntax

l-10.

Generalized Status Register Model

l-11.

Typical Status Register Bit Changes

l-12.

Status Registers

l-

13. The TRIG Trigger Configuration

l-14. Simplified Trigger Model

2-l. Instrument Trigger Model

Simplified

Common Command Syntax

Command Tree

Subsystem Command Syntax

.....................

..................

.................

Tables

...............

..........

.............

.............

............

........

...........

............

.............

............

..............

................

l-20

l-21

l-23

l-24

l-33

l-37

l-38

l-39

l-40

l-69

l-71

l-78

l-81

l-82

2-34

l-l. Command Table

l-2.

SCPI Data Types

l-3.

Sample Sweeper Commands

2-l.

Interactions between Dwell, Sweep Time, and Points. _ _ _ .

2-2. HP 83750 SCPI Sweep Mode Programming Table

2-3. Sweeper Key Codes

5-l. SCPI Conformance

Contents-12

.....................

....................

...............

...................

....................

......

l-25

l-41

l-49

2-64

2-71

2-80

5-4

Page 21

1

Getting Started

Programming

Page 22

Getting Started Programming

HP-& the Hewlett-Packard Interface Bus, is the instrument-to-instrument

communication system between the sweeper and up to 14 other instruments.

Any instrument having

including non-HP instruments that have

or

‘IEC-625”

electricahy equivalent although

portion of the manual specifically describes interfacing the sweeper to a

computer.

capability (these are common generic terms for

HP-II3

capability

W-625

can

be interfaced to the sweeper,

“GPIB,” “IEEE-488, ’

uses a unique connector). This

“ANSI

HP-E!;

MCl.

all are

1,”

The first part of this section provides general

the Standard Commands for Programmable Instruments language

introduced, and example programs are given.

HP-LB

information. Later,

(SCPI)

is

l-2

Page 23

HP-IB General Information

Interconnecting Cables

The Installation Guide shows the sweeper rear-panel

and suitable cables, and describes the procedures and limitations for

interconnecting instruments. Cable length restrictions, also described in the

Installation Guide, must be observed to prevent transmission line propagation

delays that might disrupt HP-IB timing cycles.

HIP-B

connector

Instrument Addresses

Each in.stnunent in an HP-IB network must have a unique address, an integer

ranging in value from 0 to 30. The default address for the sweeper is 19, but

this can be changed using the

(m) [m)

keys or rear panel switch.

1-3

Page 24

Getting Started Programming

HP-IB General Information

Listener

Talker

Controller

HP-B

An HP-IB instrument is categorized as a ‘listener, n “talker, * or “controller,

Instrument Nomenclature

n

depending on its current function in the network.

A listener is a device capable of receiving data or commands from other

instruments. Any number of instruments in the HP-IB network can be

listeners simultaneously.

A talker is a device capable of transmitting data or commands to other

instruments.

‘lb

avoid confusion, an HP-IB system

allows

only one device at a

time to be an active talker.

A controller is an instrument, typically a computer, capable of managing the

various HP-IB activities. Only one device at a time can be an active controller

Programming the Sweeper

The sweeper can be controlled entirely by a computer (although the line

POWER switch must be operated manually). Several functions are possible

only by computer (remote) control. Computer programming procedures for

the sweeper involve selecting an

the

specific

sweeper (SCPI, Analyzer) programming codes to that statement

to achieve the desired operating conditions. The programming codes can be

categorized into two groups: Those that mimic front panel keystrokes; and

those that are unique, and have no front panel equivalent.

HP-IE3

command statement, then adding

In the

progmmming

explanations that

follow,

specific examples are included

that are written in a generic dialect of the BASIC language. BASIC was

selected because the majority of HP-IB computers have BASIC language

capability. However, other languages can also be used.

l-4

Page 25

Getting Started Programming

HP-IB General

lnfomation

HP-II3

Command statements form the nucleus of

understood by all mstruments in the network and, when combined with

the

communication instructions for the system.

An explanation of the eight fundamental command statements follows.

However, some computers use a slightly different terminology, or support an

extended or enhanced version of these

explanations as a starting point, but for detailed information consult the

BASIC language reference manual, the

manual for the particular computer used.

Syntax drawings accompany each statement: All items enclosed by a circle or

oval are computer specific terms that must be entered exactly as described;

items enclosed in a rectangular box are names of parameters used in the

statement; and the arrows indicate a path that generates a valid combination

of statement elements.

Command Statements

progmmming

language codes, they provide all management and data

HP-D

programming; they are

conunands.

I/O

programming guide, and the

Consider the following

HP-IB

l-5

Page 26

Page 27

Getting Started Programming

HP-IB General lnfomation

Remote

Remote causes an instrument to change from local control to remote control.

In remote control, the front panel keys are disabled (except for the

key and the POWER switch), and the REMOTE Annunciator is lighted. The

syntax is:

[E?Kj

Some BASIC examples

where the device selector is the address of the instrument appended to the

HP-E3

port number. Typically, the

HP-II3

port number is 7, and the default

address for the sweeper is 19, so the device selector is 719.

10

REMOTE7

which prepares

all HP-II3

instruments for remote operation (although

nothing appears to happen to the instruments until they are addressed to

talk), or

10

REMOTE719

which affects the HP-B instrument located at address 19, or

10

REMOTE719,

which effects four instruments that

721, 726, 715

have addresses

19, 21,

26,

and

15.

1-7

Page 28

Getting Started Programming

HP-IB General Information

-

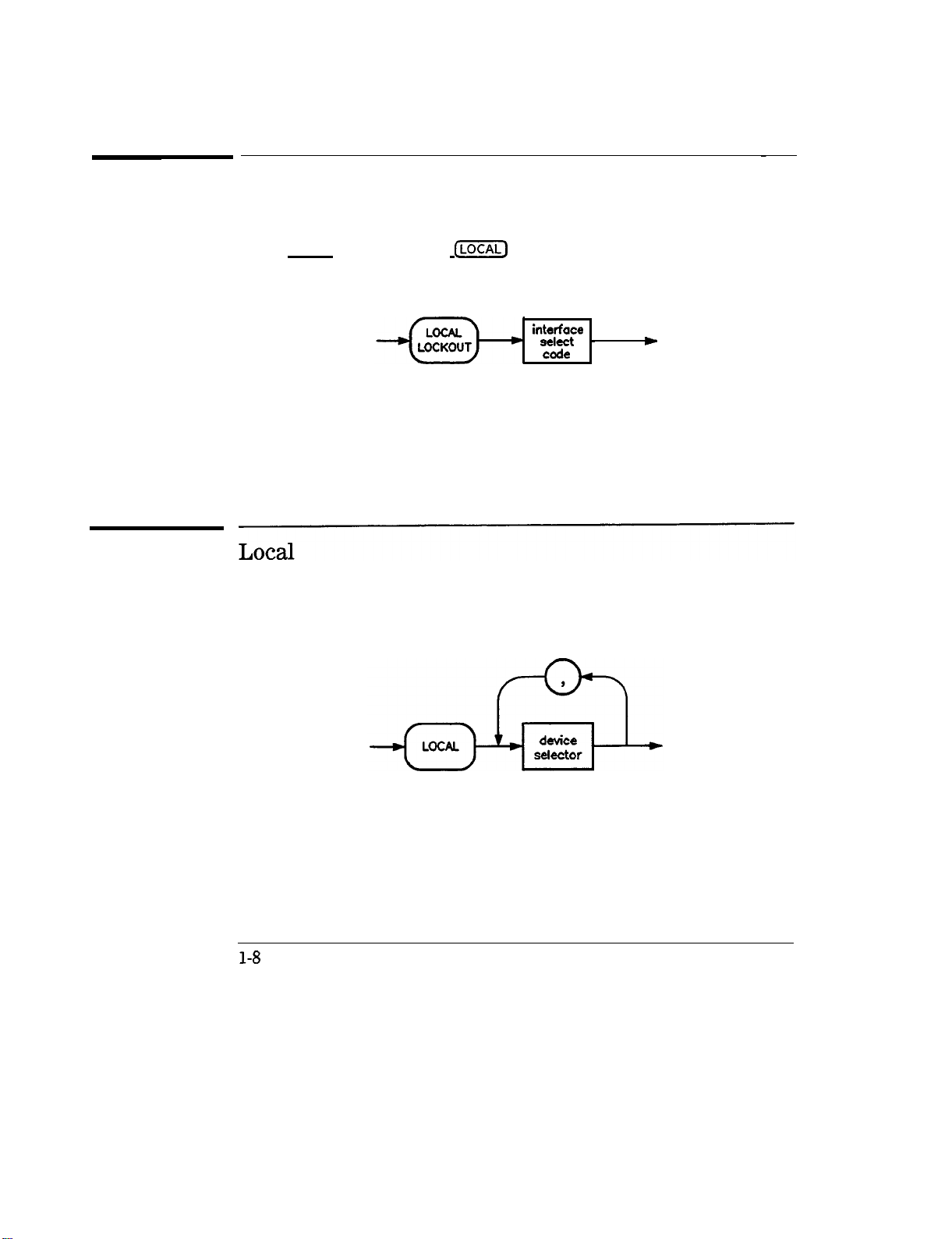

Local Lockout

Local Lockout can be used in conjunction with REMOTE to disable the front

panel (LOCAL) key. With the

hard reset by the POWER switch) can restore local control. The syntax is:

(ml

key disabled, only the controller (or a

A BASIC example

10

20

REMOTE

719

LOCALLOCKOUT

interface

sect -

code

w

Local is the complement to REMOTE, causing an instrument to return to local

control with a fully enabled front panel. The syntax is:

Some BASIC examples

LOCAL 7

10

which effects all instruments in the network, or

LOCAL 719

10

for an addressed instrument (address 19).

l-8

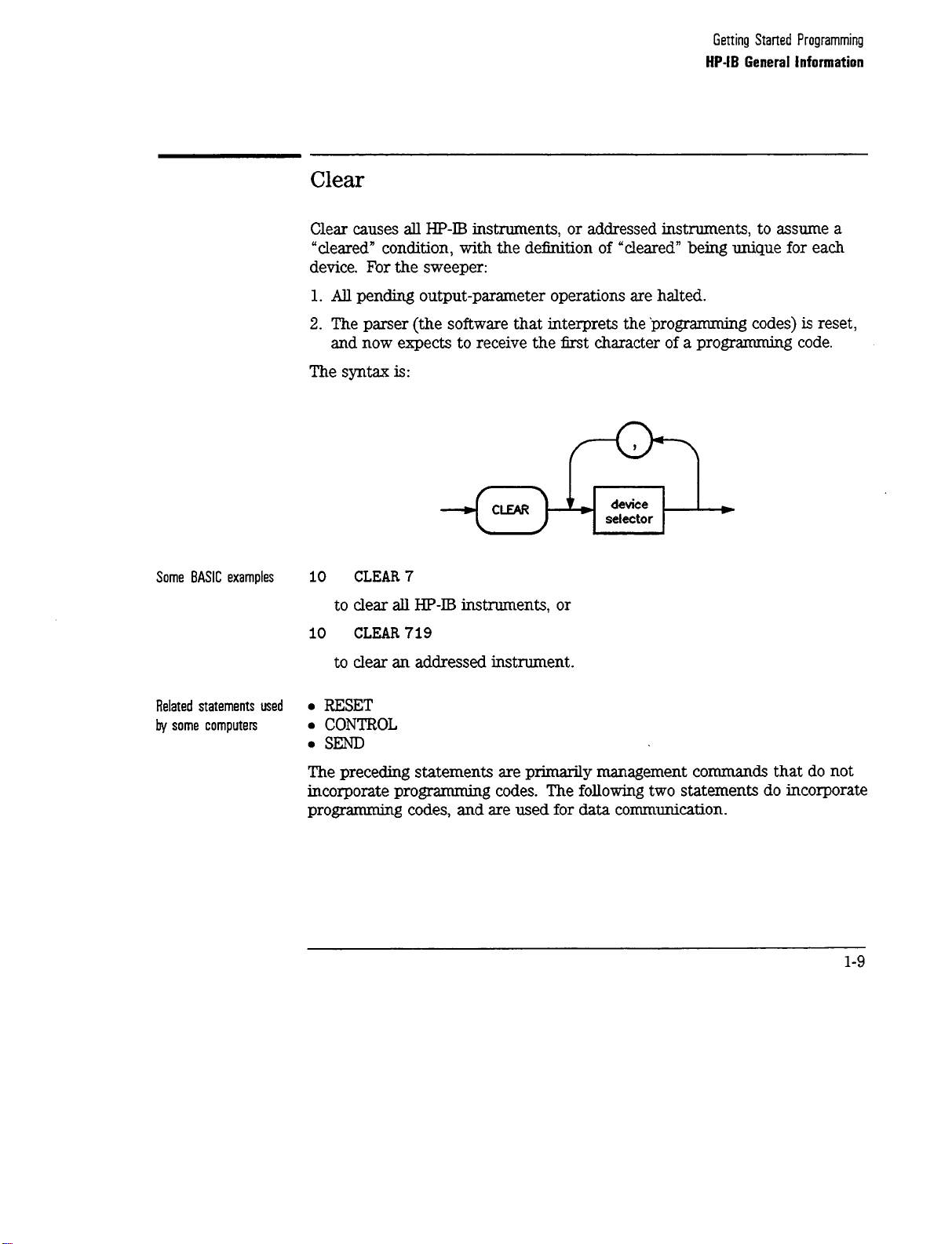

Page 29

Page 30

Getting Started Programming

HP-IB General Information

output

Output is used to send function commands and data commands from the

controller to the addressed instrument. The syntax is:

where USING is a secondary command that formats the output in a particular

way, such as a binary or ASCII representation of numbers. The USING

command is followed by “image items” that precisely define the format of the

output; these image items can be a string of code characters, or a reference

to a statement line in the computer program. Image items are explained in

the

programming

codes where they are needed. Notice that this syntax

is

virtually identical to the syntax for the ENTER statement that follows.

l-10

Page 31

Page 32

Getting Started Programming

HP-18

General Information

Enter

Enter is the complement of OUTPUT, and is used to transfer data from the

addressed instrument to the controller. The syntax is:

ENTER is always used in conjunction with OUTPUT, such as:

100

OUTPUT 719; ‘I . . . programming codes . . .

110

ENTER 719; ” . . . response data.. .

”

”

ENTER statements are commonly formatted, which requires the secondary

command USING and the appropriate image items. The most-used image

items involve end-of-line (end or identify) suppression, binary inputs, and

literal inputs.

Example

100 EXTER719USING ‘I#, B”;

suppresses the EOI sequence

are to be filled with binary

100

ENTER

719 USING

I’#, 123A”

A, B, C

(#),

and indicates that variables A, B, and C

(B)

data. As another example,

; A$

suppresses EOI, and indicates that string variable A$ is to be filled with

123 bytes of literal data

(123A).

1-12

Page 33

Getting Started Programming

HP-IB General Information

NOTE

Be careful when using byte-counting image specifiers. If the requested number of bytes does not

match the actual number available, data might be lost, or the program might enter an endless wait

state.

The suppression of the EOI sequence is frequently necessary to prevent a

premature termination of the data input. When not specified, the typical

EOI termination occurs when an ASCII LF (line feed) is received. However,

the LF bit pattern could coincidentally occur randomly in a long string of

binary data, where it might cause a false termination. Also, the bit patterns

for the ASCII CR (carriage return), comma, or semicolon might cause a false

termination. Suppression of the EOI causes the computer to accept all bit

patterns as data, not conunands, and relies on the HP-IB EOI (end or identify)

line for correct end-of-data termination.

Related statements used

by some computers

. CONVERT

. IMAGE

l

IOBUFFER

l

ONTIMEOUT

. SET TIMEOUT

. TRANSFER

This completes the HP-IB Command Statements subsection. The following

material explains the SCPI programming codes, and shows how they are used

with the OUTPUT and ENTER HP-IB command statements.

1-13

Page 34

Getting Started with SCPI

This section of chapter 1 describes the use of the Standard Commands for

Programmable Instruments language

SCPI commands in general. The instrument command summary

lists the specific commands available in the instrument. This section presents

only the basics of SCPI. If you want to explore the topic in greater depth, see

the paragraph titled, “Related Documents.

(SCPl).

This section explains how to use

n

in Chapter 5

1-14

Page 35

Definitions of Terms

You need a general understanding of the terms listed below before you

continue.

controller

instrument

program

message

response

message

command

A controller is any computer used to communicate with a

SCPI instrument. A controller can be a personal computer,

a minicomputer, or a plug-in card in a card cage. Some

intelligent instruments can also function as controllers.

An instrument is any device that implements SCPI. Most

instruments are electronic measurement or stimulus devices,

but this is not a requirement. Similarly, most instruments

use an

concepts apply regardless of the instrument function or the

type of interface used.

A program message is a combination of one or more

properly formatted SCPI commands. Program messages

always go from a controller to an instrument. Program

messages tell the instrument how to make measurements

and output signals.

A response message is a collection of data in

formats. Response messages always go from an instrument

to a controller or listening instrument. Response messages

tell the controller about the internal state of the instrument

and about measured values.

A command is an instruction in SCPI. You combine

commands to form messages that control instruments. In

general, a command consists of mnemonics (keywords),

parameters, and punctuation.

HP-D3

interface for communication. The same

spetic

SCPI

query

A query is a special type of command. Queries instruct the

instrument to make response data available to the controller.

Query mnemonics always end with a question mark.

1-15

Page 36

Getting

Staned

Programming

Definitions of Terms

Standard Notation

This section uses several forms of notation that have specific meaning.

Command Mnemonics

Angle Brackets

Many commands have both a long and a short form, and you must use either

one or the other (SCPI does not accept a combination of the two). Consider

the

FREQuency

command,for example. The short form is FREQ and the long

form is FREQUENCY (this notation style is a shorthand to document both the

long and short form of commands). SCPI is not case sensitive, so

fREquEnCy

is just as valid as FREQUENCY, but FREQ and FREQUENCY are the only valid

forms of the

FREQuency

command.

Angle brackets indicate that the word or words enclosed represent something

other than themselves. For example,

character with the decimal value 10.

asserted on the

HP-II3

interface. Words in angle brackets have much more

<new

line> represents the ASCII

Siruilarly, <‘END>

means that EOI is

rigidly defined meaning than words used in ordinary text. For example, this

section uses the word “message” to talk about messages generally. But the

bracketed words <program message> indicate a precisely

dellned

element of

SCPI. If you need them, you can find the exact definitions of words such as

<program message> in a syntax diagram.

How to Use Examples

It is important to understand that progr

amming

with SCPI actually requires

knowledge of two languages. You must know the programming language of

your controller (BASIC, C, Pascal) as well as the language of your instrument

(SCPI). The semantic requirements of your controller’s language determine

how the SCPI commands and responses are handled in your application.

1-16

Page 37

Getting Started Programming

Definitions of Terms

Command Examples

Response Examples

Command examples look like this:

:FREQuency:CW?

This example tells you to put the string :

FEEQuency

: CW? in the output

statement appropriate to your application programming language. If you

encounter problems, study the details of how the output statement handles

message terminators such as

<new

line>. If you are using simple OUTPUT

statements in HP BASIC, this is taken care of for you. In HP BASIC, you type:

OUTPUT

Source;“:FREQuency:CW?”

Command examples do not show message terminators because they are used

at the end of every program message.

“Details of Commands and Responses,

n

discusses message terminators in more detail.

Response examples look like this:

1.23

These are the characters you would read from an instrument after

sending a query command. To actually pull them from the instrument into

the controller, use the input statement appropriate to your application

programming language. If you have problems, study the details of how the

input statement operates. In particular, investigate how the input statement

handles punctuation characters such as comma and semicolon, and how it

handles

<new

line> and EOI. ‘lb enter the previous response in HP BASIC,

you type:

ENTER

Source;CW,frequency

Response examples do not show response message terminators because

they are always <new line>

<-END>.

These terminators are typically

automatically handled by the input statement. The paragraph titled “Details

of Commands and Responses” discusses message terminators in more detail.

1-17

Page 38

Essentials for Beginners

This subsection discusses elementary concepts critical to &st-time users of

SCPI. Read and understand this subsection before going on to another. This

subsection includes the following topics:

Program and Response

Messages

Subsystem Command Trees

Subsystem Command Tables

Reading Instrument Errors

Example Programs

These paragraphs introduce the basic types

of messages sent between instruments and

controllers.

These paragraphs describe the tree structure

used in subsystem commands.

These paragraphs present the condensed

tabular format used for documenting

subsystem commands.

These paragraphs explain how to read

and print an instrument’s internal error

messages.

These paragraphs contain two simple

measurement programs that illustrate basic

SCPI programming principles.

1-18

Page 39

Getting Started Programming

Essentials for Beginners

Program and Response Messages

To understand how your instrument and controller communicate using

SCPI, you must understand the concepts of program and response messages.

Program

instrument. Conversely,

the instrument to the controller. Program messages contain one or more

commands, and response messages contain one or more responses.

The controller may send commands at any time, but the instrument sends

responses only when

command used to instruct the instrument to send a response message is the

QZUZQ.

measured values or internal instrument settings. Any internal setting that can

be programmed with SCPI can also be queried.,

messages

are the formatted data sent from the controller to the

response

specifically

messages are the formatted data sent from

instructed to do so. The special type of

All query mnemonics end with a question mark. Queries return either

Forgiving listening and

Precise Talking

Tvpes

of Commands

SCPI uses the concept of forgiving listening and precise talking outlined in

IEEE 488.2.

Rxgiting

listening means that instruments are very flexible in accepting

various command and parameter formats. For example, the sweeper accepts

either

:POWer:STATe ON

R-&e talk%ng

means that the response format for a particular query is

or

:POWer:STATe

ItoturnRFoutputon.

always the same. For example, if you query the power state when it is on

(using

previously sent :

Commands

:POWer:

STATe?), the response is always I,

POWer

: STATe 1 or

:POWer

: STATe ON.

regardless of whether you

can be separated into two groups, common commands and

subsystem commands.

Common comwzun&

are generally not measurement related. They are

used to manage macros, status registers, synchronization, and data storage.

Common commands are easy to recognize because they all begin with an

asterisk, such as

*IDN?, *OPC, and

*RST.

Common commands are defined by

IEEE 488.2.

3&.@em

commands include all measurement functions and some general

purpose functions. Subsystem commands are distinguished by the colon used

3

between keywords,

asin :FREQuency:CW..

Each command subsystem is a

1-19

Page 40

Getting Started Programming

Essentials for Beginners

set of conunands that roughly corresponds to a functional block inside the

instrument. For example, the

POWer

subsystem contains commands for power

generation, while the STATUS subsystem contains commands for accessing

status registers.

*

RST

*

IDN?

: MEAS : VOLT?

:FREQ 1KHz

cg410

Figure l-l. SCPI Command Types

The remaining paragraphs in this subsection discuss subsystem commands in

more detail. Remember, some commands are implemented in one instrument

and not in another, depending on its measurement function.

l-20

Page 41

Subsystem Command Trees

Getting Started Programming

Essentials for Beginners

The Command Tree

Structure

Paths Through the

Command Tree

Most programming tasks involve subsystem commands. SCPI uses a

hierarchical structure for subsystem commands similar to the file systems on

most computers. In SCPI, this command structure is called a command

root

level 1

I

BB

AA

I

cc DD

tree.

d-l

level 2 EE FF GG

Figure 1-2. A Simplified Command Tree

In the command tree shown in Figure

is the root commww!, or simply the root. Notice that you must follow a

particular

to access the GG command, you must follow the path AA to BB to GG.

lb access commands in di8erent paths in the command tree, you must

understand how an instrument interprets commands. A special part of the

instrument firmware, a

The parser breaks up the message into component commands using a set of

rules to determine the command tree path used. The parser keeps track of

the current path, the level in the command tree where it expects to find the

next

appear in different paths. The particular path you use determines how the

keyword is interpreted. The following rules are used by the parser:

puth

command

to reach lower level subcommands. For example, if you wish

panser,

you send. This is important because the same keyword may

decodes each message sent to the instrument.

l-2,

the command closest to the top

HH

JJ

1-21

Page 42

Getting Started Programming

Essentials for Beginners

l

RxwrOnandReset

After power is cycled or after

*RST,

the current path is set to the root.

A message terminator, such as a <new line> character, sets the current

path to the root. Many progr

amming

languages have output statements

that send message terminators automatically. The paragraph titled, “Details

of Commands and Responses, ’ discusses message terminators in more

detail.

When it is between two command mnemonics, a colon moves the current

path down one level in the command tree. For example, the colon in

MEAS

is the

: VOLT

tit

speties

that VOLT is one level below

character of a command, it

spec3ies

MEAS.

When the colon

that the next command

mnemonic is a root level command. For example, the colon in : INIT

specifies that INIT is a root level command.

A semicolon separates two commands in the same message without

changing the current path.

Whitespace characters, such as <tab> and <space>, are generally ignored.

There are two important exceptions. Whitespace inside a keyword, such

as

:FREQ

uency, is not allowed. You must use white space to separate

parameters from commands. For example, the <space> between

6.2 in the command :

not

tiect

the current path.

POHer

:

LEVe16.2

is mandatory. Whitespace does

LEVel

and

l

Cbmmas

lf a command requires more than one parameter, you must separate

adjacent parameters using a comma. Commas do not

affect

the current

path.

l

comrnOncOmmands

Common commands, such as

*RST,

are not part of any subsystem. An

instrument interprets them in the same way, regardless of the current path

setting.

l-22

Page 43

Getting Started Programming

Essentials for Beginners

I

BB

I

EE

AkBB:EE;FF;GG

A4zBB:EE; A4zDD:JJ

FF

Figure

I

cc

I

GG

l-3.

Proper Use of the Colon and Semicolon

I

HH

I

DD

I

JJ

R Sets current path

0

to ROOT

N NO change to

0

current path

Figure l-3 shows examples of how to use the colon and semicolon to

navigate efficiently through the command tree. Notice how proper use of the

semicolon can save typing.

Sending this message:

:AA:BB:EE; FF; GG

Is the same as sending these three messages:

:AA:BB:EE

:AA:BB:FF

:AA:BB:GG

l-23

Page 44

Getting Started Programming

Essentials for Beginners

Subsystem Command

These paragraphs introduce a more complete, compact way of documenting

subsystems using a tabular format. The command table contains more

information than just the command hierarchy shown in a graphical tree. In

particular, these tables list command parameters for each command and

response data formats for queries. To begin this exploration of command

tables, consider a simplified

graphical and tabular formats.

SWEep

SWEep

‘Ihbles

subsystem for the sweeper in both the

I

I

DWELI

AUTO

Figure

GENeration

POlNt RELative

l-4.

Simplified SWEep Command Tree

MANuaI

l-24

Page 45

Table

1-l.

Command Table

Getting Started Programming

Essentials for Beginners

Reading the Command

Table

Parameter

Two

:SWEep

:OWEU

:GENeration

:MANual

Command

:AUTO

:POINt

[:RELativel

state

Parameters

BooieanJONCE

Note the three columns in the command table labeled Command, Parameters,

and

parameter Type.

Commands closest to the root level are at the top of

the table. Commands in square brackets are implied commands, which are

discussed in later paragraphs. If a command requires one or more parameters

in addition to the keyword, the parameter names are listed adjacent to the

command. Parameters in square brackets are optional parameters, which

are discussed in later paragraphs. If the parameter is not in square brackets,

it is required and you must send a valid setting for it with the matching

command. The parameter type is listed adjacent to each named parameter.

1-25

Page 46

Getting Started Programming

Essentials for Beginners

More About Commands

Query and Event

Commands

implied Commands

Optional Parameters

Because you can query any value that you can set, the query form of each

command is not shown explicitly in the command tables. For example,

the presence of the sweeper : SWEep :

: SWEep :

DUELl?

also exists. If you see a table containing a command ending

DWELl

command implies that a

with a question mark, it is a query only command. Some commands are

events, and cannot be queried. An event has no corresponding setting if it

causes something to happen inside the instrument at a particular instant. For

example, :

Because it is an event, there is no query form of :

Implied

INITiate

: IMMediate causes a certain trigger sequence to initiate.

INITiate

: IMMediate.

commands appear in square brackets in the command table. If you

send a subcommand immediately preceding an implied command, but do

not send the implied command, the instrument assumes you intend to use

the implied command, and behaves just as if you had sent it. Note that this

means the instrument expects you to include any parameters required by

the implied command. The following example illustrates equivalent ways to

program the sweeper using explicit and implied

commands.

Example sweeper commands with and without an implied commands:

: SWEep :

: SWEep :

MANual

MANual

:

RELative

6

6

u&w explicit commands

using implied wmmands

Optional parameter names are enclosed in square brackets in the command

table. If you do not send a value for an optional parameter, the instrument

chooses a default value. The instrument’s command dictionary documents the

values used for optional parameters.

l-26

Page 47

Getting Started Programming

Essentials for Beginners

Program Message Examples

The following parts of the sweeper SCPI command set will be used to

demonstrate how to create complete SCPI program messages:

:

FRF.Quency

C:CWl

:MULTiplier

:STATE

: POWER

[:LEVEL]

Example 1

Example 2

"FREQuency:CW

5 GHZ;

MULTiplier2"

The command is correct and will not cause errors. It is equivalent to

sending:

"FREQuency:CW

"FREQuency5

5 GHZ;

GHZ;

:FREQuency:MULTiplier2".

MULTiplier2"

This command results in a command error. The command makes use of

the default

the current path position. Since there is no command

[:CWJ

node. When using a default node, there is no change to

WULT”

at the root,

an error results. A correct way to send this is:

“F&Q 5 GHZ; FREQ

:I4ULT 2”

or as in example 1.

l-27

Page 48

Getting Started Programming

Essentials for Beginners

Example 3

Example 4

"FREQuency:MULTiplier2;

MULTiplier:STATEON;

FREQuency:CW5

GHZ"

This command results in a command error. The

F’REQ:CW

portion of the

command is missing a leading colon. The path level is dropped at each

colon until it is in the

F’REQ:h3UI.T

subsystem. So when the

F’REQ:CW

command is sent, it causes confusion because no such node occurs in the

F’REQ:MULT

subsystem. By adding a leading colon, the current path is

reset to the root. The corrected command is:

"FREQuency:MULTiplier2;

5

GHZ".

"FREQ5

GHZ;

POWER4DBM"

Notice that in this example the keyword short

command is correct. It utilizes the default nodes of

MULTiplier:STATE

ON;

formis

[:Cw]

:FFEQuency:CW

used. The

and [LEVEL].

Since default nodes do not affect the current path, it is not necessary to

use a leading colon before POWER.

l-28

Page 49

Parameter Types

Getting Started Programming

Essentials for Beginners

Numeric Parameters

As you saw m the example command table for

SWEep,

there are several

types of parameters. The parameter type indicates what kind of values are

valid instrument settings. The most commonly used parameter types are

numeric, extended numeric, discrete, and Boolean. These common types are

discussed briefly in the following paragraphs. The paragraph titled “Details of

Commands and Responses” explains all parameter types in greater depth.

Numeric parameters are used in both subsystem commands and common

commands. Numeric parameters accept all commonly used decimal

representations of numbers including optional signs, decimal points, and

scientific notation. If an instrument accepts only specifk numeric values, such

as integers, it automatically rounds numeric parameters to fit its needs.

Examples of numeric parameters:

100

100.

-1.23

4.56e<space>3

-7.89E-01

+256

.5

no

decinml

point required

ji-actimal digits optimal

leading signs

space allowed am e in

we either E or e in

allowed

eqwnmt.s

exponentials

leading + allowed

digits

lq? of

decimal point optional

Examples of numeric parameters in commands:

100 OUTPUT @Source; ”:

110

OUTPUT

@Source; “:POWer LEVel

FREQuency

:

STARt

-5”

l.OE+09”

l-29

Page 50

Getting

Staned

Programming

Essentials for Beginners

Extended Numeric

Parameters

Most measurement related subsystems use

IZZWKJ&

numeric parameters to

specify physical quantities. Extended numeric parameters accept all numeric

parameter values and other special values as well. AU extended numeric

parameters accept

MAXimum

and

MINimum

as values. Other special values,

such as UP and DOWN may be available as documented in the instrument’s

command summary. Some instruments also let you to scud engineering units

as

sufhxes

lists the

to extended numeric parameters. The SCPI

sulZxes

available, if any. Note that extended numeric parameters are

Comman

d Summary

not used for common commands or STATUS subsystem commands.

Examples of extended numeric parameters:

ang

100.

-1.23

simple numeric values

largest valid setting

4.56e<space>3

-7.89E-01

+256

.5

MAX

MIN

valid setting nearest negative

iqjinity

Examples of extended numeric parameters in commands:

100 OUTPUT @Source ; ‘I :

FREQuency

: STOP MAX”

l-30

Page 51

Getting Started Programming

Essentials for Beginners

Discrete Parameters

Boolean Parameters

Use discrete parameters to program settings that have a

values. Discrete parameters use mnemonics

to

represent each valid setting.

finite

number of

They have a long and a short form, like command mnemonics. You can use

mixed upper and lower case letters for discrete parameters.

Examples of discrete parameters:

INTernal level

DIODe

PMETer

MMHead

internally

level using an

level using an

external

-1powermeter

diode

Level using a mm-wave source module

Examples of discrete parameters in commands:

100 OUTPUT

110 OUTPUT

QSource;”

@Source;”

:POWer:ALC:SOUHce INT”

:POWer:ALC:SOUHce mmh”

Although discrete parameters values look like command keywords, do not

confuse the two. ln particular, be sure to use colons and spaces properly.

Use a colon to separate command mnemonics from each other. Use a

space to separate parameters from command mnemonics.

Boolean parameters represent a single binary condition that is either true or

false. There are only four possible values for a Boolean parameter.

Examples of Boolean parameters:

ON

OFF

1

0

Boolean TRUE,

upperher case

Boolean FALSE,

Boolean TRUE

Boolean FALSE

u.er/lozuer

allowed

case allowed

Examples of Boolean parameters in commands:

100 OUTPUT @Source ; I’ : FM :

110 OUTPUT QSource;“:AM:STATe

STATe

On”

I”

1-31

Page 52

Getting

Staned

Programming

Essentials for Beginners

Reading Instrument Errors

When debugging a program, you may want to know if an instrument error

has occurred. Some instruments can display error messages on their front

panels. If your instrument cannot do this, you can put the following code

segment in your program to read and display error messages.

10

!

20 ! The rest of your

30 ! variable declarations

40

!

50

DIM

Err_msg$[751

60

INTEGER

70

!

80 ! Part of your program

90 ! that generates errors

100

!

110

!

200

REPEAT

210

220

230

240

250

260

270

OUTPUT

! Query instrument error

ENTER

! Read error #, message

PRINT

! Print error message

UNTIL Err,num = 0

280 ! Repeat until no errors

290

!

300 ! The rest of your program

310

!

Err,num

@Box;":SYST:ERR?"

QBox;Err,num,Err,msg$

Err,num,Err,msg$

l-32

Page 53

Getting Started Programming

Essentials for Beginners

Exarnple Programs

The following is an example program using SCPI compatible instruments. The

example is written in HP BASIC.

This example is a stimulus and response application. It uses a source and

counter to test a voltage controlled oscillator.

This example demonstrates how several SCPI instruments work together

to perform a stimulus/response measurement. This program measures the

linearity of a voltage controlled oscillator (VCO). A VCO is a device that

outputs a frequency proportional to an input signal level.

how the hardware is configured.

Unit Under Test .

F’igure

1-5 shows

Example Program

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

Stimulus

source

0-5OOmV

Figure 1-5. Voltage Controlled Oscillator Test

!

INTEGER

DIM Id$

First,Last,Testpoint,Dummy

[701

ASSIGN @Stimulus TO 717

ASSIGN @Response TO 718

!

First=0

c

vco

HP

BASIC

Controller

e

Response

Counter

l-33

Page 54

Getting Started Programming

Essentials for Beginners

90

100

110

120

130

140

150

160

170

180

190

200

210

220

230

240

250

260

270

280

290

300

310

320

330

340

350

360

370

380

390

400

410

420

430

440

450

460

470

480

Last=100

!

CLEAR @Stimulus

CLEAR @Response

!

OUTPUT

OUTPUT

QStimulus;"*RST"

OResponse;"*RST"

!

PRINT "Voltage Controlled Oscillator Test"

PRINT

!

PRINT "Source Used .

OUTPUT

ENTER

OStimulus;"*IDN?"

QStimulus;Id$

.."

PRINT Id$

PRINT

!

PRINT "Counter Used .

OUTPUT

ENTER

OResponse;"*IDN?"

OResponse;Id$

.."

PRINT Id$

PRINT

!

OUTPUT

QStimulus;":OUTPUT

ON"

!

PRINT

PRINT "INPUT

PRINT

II--------,-II II------------II

[mv]","OUTPUT CkIizl”

,

PRINT

!

FOR

Testpoint=First

OUTPUT

ENTER

OUTPUT

ENTER

PRINT

QStimulus;":SOURCE:VOLT

QStimulus;Dummy

OResponse;":MEAS:FREQ?"

OResponse;Reading

Testpoint,Reading/lOOO

TO Last

";VAL$(Testpoint/lOOO);";*OPC?"

NEXT Testpoint

!

OUTPUT

QSource;":OUTPUT

OFF"

END

l-34

Page 55

Getting Started Programming

Essentials for Beginners

Program Comments

Lines 20 to 70: Declare variables and

I/O

paths for instruments.

I/O

paths let

you use a name for an instrument m OUTPUT and ENTER statements, instead

of a numeric address.

80 to 100:

110 to 130:

140 to 160:

170 to 190:

200 to 310:

Assign values to the input test limits in

Clear the instrument

HP-LB

interfaces.

Reset each instrument to a known measurement state.

Ftrint

the test report title.

Query measurement instruments’

identikations

mV.

for test

traceability.

320 to 330:

340 to 380:

390 to 460:

Connect the source output signal to the output terminals.

Print results table header.

This is the main measurement loop. Line 400 contains two

commands. :

*OPC?

is used to signal that the preceding command has

SOUFtce

: VOLT sets the output level of the source.

finished executing. To make an accurate measurement, the

source output must be allowed to settle. When the output has

settled,

*OPC?

places a 1 in the source Output Queue. The

program waits at line 410 until the 1 returned by *OPC? is

entered.

Note that following each OUTPUT containing a query is

an

ENTER to retrieve the queried value. If you do not use paired

OUTPUTS and

ENTERs,

you can overwrite data in the instrument

Output Queue and generate instrument errors.

470 to 480:

Disconnect output terminals of the instruments

from

the unit

under test, and end the program. All HP BASIC programs must

have

END

as the last statement of the main program.

l-35

Page 56

Details of Commands and Responses

This subsection describes the syntax of SCPI commands and responses. It

provides many examples of the data types used for

response data. The following topics are explained:

Program Message These paragraphs explain how to properly construct

Syntax

the messages you send from the computer to

instruments.

conkand

parameters and

Response Message

SYnW

SCPI Data Types

These paragraphs discuss the format of messages sent

from instruments to the computer.

These paragraphs explain the types of data contained

in program and response messages.

l-36

Page 57

Getting Started Programming

Details of Commands and Responses

Program Message Syntax

These program messages contain commands combined with appropriate

punctuation and program message terminators.

)

subsystem command

common command

NOTES:

<new line>

AEND

=

<new line>

= ASCII character decimal 10

EOI asserted concurrent with last byte

Figure 1-6. Simplified Program Message Syntax

AEND

As Figure l-6 shows, you can send common commands and subsystem

commands in the same message. If you send more than one command in the

same message, you must separate them with a semicolon. You must always

end a program message with one of the three program message terminators

shown in Figure 1-6. Use

as the program message terminator. The word

asserted on the

HP-D3

interface at the same time the preceding data byte is

<new

line>,

<-END>,

or

<new

<-END>

line>

<-END>

means that EOI is

sent. Most progmmming languages send these terminators automatically.

For example, if you use the HP BASIC OUTPUT statement, <new line> is

automatically sent after your last data byte. If you are using a PC, you can

usually configure the system to send whatever terminator you specify.

l-37

Page 58

Getting Started Programming

Details of Commands and Responses

SCPI Subsystem Command Syntax

NOTE

=

SP

Figure

white

w. ASCil

I-7.

SCPI Simplified Subsystem Command Syntax

characters

O,,

to

9,0

and

ll,,

to

32,,

As Figure l-7 shows, there must be a <space> between the last command

mnemonic and the first parameter in a subsystem command. This is one of

the few places in SCPI where <space> is required. Note that if you send

more than one parameter with a single command, you must separate adjacent