Page 1

Mastering with Ozone™

Tools, tips and techniques

© 2003 iZotope, Inc. All rights reserved. iZotope and Ozone are either registered trademarks or

trademarks of iZotope, Inc. in the United States and/or other countr ies. Other product or company names

mentioned herein may be the trademarks of their respective owners.

Page 2

INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................4

What’s Wrong With My Song? ..................................................................................4

Intended Audience For This Guide ............................................................................4

WHAT IS MASTERING? ..............................................................................................6

The “Commercial Sound” ........................................................................................6

Consistency across the CD ......................................................................................6

Preparation for Duplication......................................................................................6

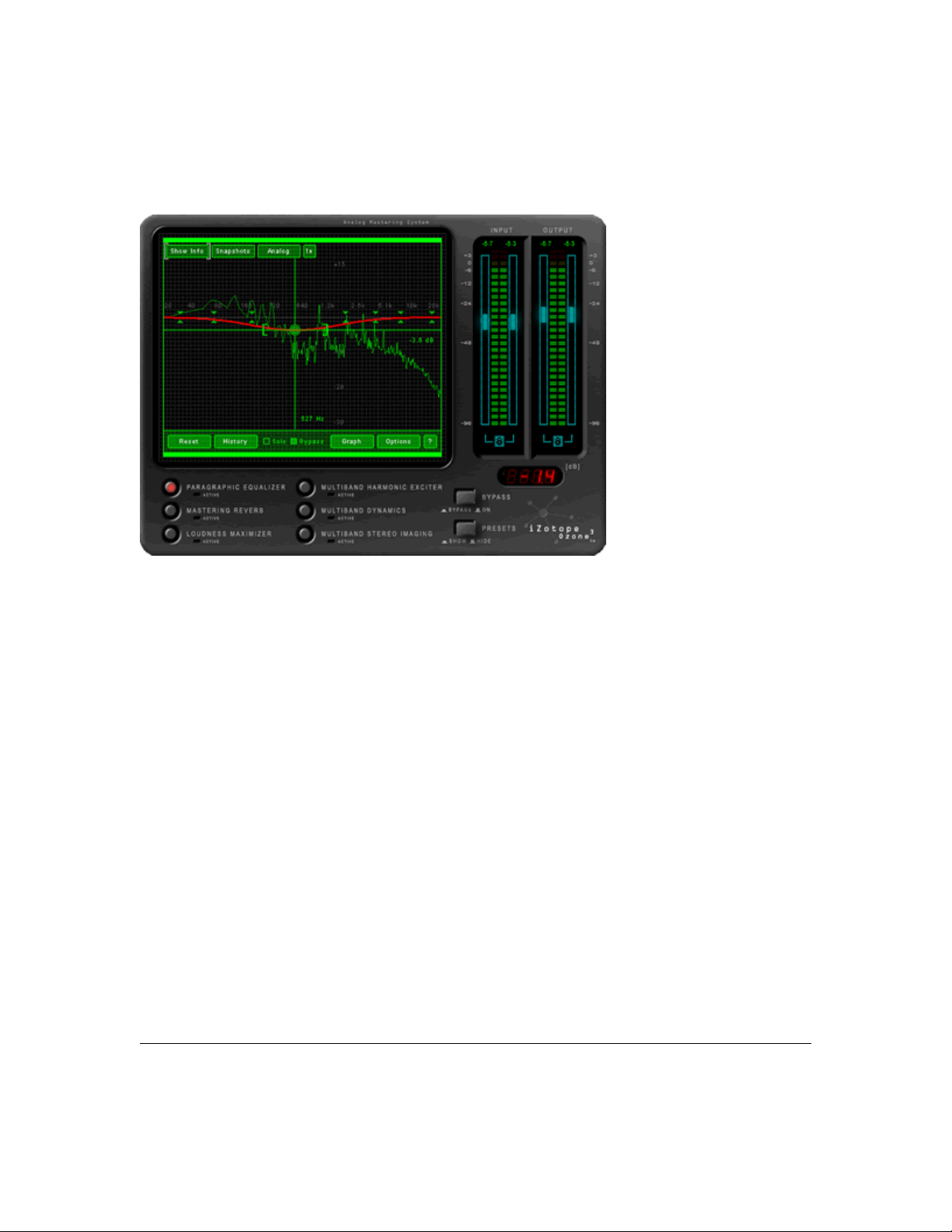

WHAT IS OZONE?.....................................................................................................7

A Mastering System ...............................................................................................7

64-bit Audio Processing ..........................................................................................7

Analog Modeling ....................................................................................................7

Digital Precision.....................................................................................................7

Meters and DSP.....................................................................................................7

UI Efficiency..........................................................................................................8

GETTING SETUP FOR MASTERING...............................................................................9

Software and Sound Card........................................................................................9

Mastering Effects ...................................................................................................9

Monitors............................................................................................................. 10

Headphones........................................................................................................ 12

SEVEN SUGGESTIONS WHILE MASTERING................................................................. 13

EQ........................................................................................................................ 14

What’s the Goal of EQ when Mastering? .................................................................. 14

EQ Principles....................................................................................................... 14

Using the Ozone Paragraphic Equalizer.................................................................... 15

EQ Shapes.......................................................................................................... 16

EQ the Midrange.................................................................................................. 19

EQ the Bass ........................................................................................................ 20

EQ the Highs....................................................................................................... 21

EQ’ing with Visual Feedback .................................................................................. 22

Spectrum Options ................................................................................................ 22

Snapshots........................................................................................................... 24

Digital or Analog EQ............................................................................................. 24

Matching EQ........................................................................................................ 25

General EQ Tips................................................................................................... 28

MASTERING REVERB............................................................................................... 29

What’s the Goal of Reverb when Mastering?............................................................. 29

Reverb Principles ................................................................................................. 29

Using the Ozone Mastering Reverb .........................................................................29

General Reverb Tips ............................................................................................. 32

MULTIBAND EFFECTS.............................................................................................. 34

Using Multiband Effects in Ozone............................................................................ 34

Setting Multiband Cutoffs...................................................................................... 35

Crossover Options................................................................................................ 35

Multiband Main Points........................................................................................... 36

MULTIBAND HARMONIC EXCITER.............................................................................. 37

Using the Multiband Harmonic Exciter in Ozone........................................................ 37

General Exciter Tips .............................................................................................38

MULTIBAND STEREO IMAGING ................................................................................. 39

Using Multiband Stereo Widening in Ozone .............................................................. 40

Phase Meter........................................................................................................ 40

Vectorscope ........................................................................................................ 41

Multiband Stereo Delay......................................................................................... 42

General Multiband Stereo Imaging Tips................................................................... 42

MULTIBAND DYNAMICS........................................................................................... 44

Compression Basics.............................................................................................. 44

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 2 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 3

Dynamics Meters ................................................................................................. 46

Overall Compression Strategy................................................................................ 49

Bringing Limiting and Expansion into the Mix ........................................................... 49

Limiter ............................................................................................................... 50

Compressor ........................................................................................................50

Expander............................................................................................................ 50

Limiter/Compressor/Expander Summary ................................................................. 51

Multiband Dynamics............................................................................................. 51

Bass Boost.......................................................................................................... 52

Warmth.............................................................................................................. 53

Vocal Treatment .................................................................................................. 54

Noise Gating .......................................................................................................54

LOUDNESS MAXIMIZER ........................................................................................... 56

Loudness Maximizer Principle................................................................................. 56

Using the Ozone Loudness Maximizer......................................................................57

General Loudness Maximizer Tips........................................................................... 59

GENERAL OZONE TOOLS ......................................................................................... 60

Automation......................................................................................................... 60

History List ......................................................................................................... 61

Setting the Order of the Mastering Modules .............................................................62

Preset Manager ................................................................................................... 63

Shortcut Keys and Mouse Wheel Support................................................................. 64

SUMMARY.............................................................................................................. 66

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 3 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 4

INTRODUCTION

You’ve just finished recording what you think is a pretty good song in your project studio. The

playing is good, the recording is clean and the mix is decent. So you burn it to a CD and

proudly pop it in your CD player. But when you hear it played after a “commercial” CD, you

realize that something is wrong.

What’s Wrong With My Song?

• It’s not loud enough. It sounds wimpy next to other CDs. Turning it up or mixing down

at a higher level doesn’t solve the problem. It sounds louder, but not, well LOUDER.

• It sounds dull. Other CDs have a sparkle that cuts through with excitement. You try

boosting the EQ at high frequencies, but now your song just sounds harsh and noisy.

• The instruments and vocals sound thin. Commercial songs have a fullness that you

know comes from some sort of compression. So you patch in a compressor and turn

some controls. Now the whole mix sounds squashed. The vocal might sound fuller, but

the cymbals have no dynamics. It’s full…and lifeless.

• The bass doesn’t have punch. You boost it with some low end EQ, but that just sounds

louder and muddier. Not punchier.

• You can hear all the instruments in your mix, and they all seem to have their own

“place” in the stereo image, but the overall image sounds wrong. Your other CDs have

width and image that you just can’t seem to get from panning the individual tracks.

• You had reverb on the individual tracks, but it just sounds like a bunch of instruments

in a bunch of different spaces. Your other CDs have a sort of cohesive space that

brings all the parts together. Not like rooms within a room, but a “sheen” that works

across the entire mix.

Don’t worry. It’s not that you’re doing anything wrong. There are just some things you still

need to do to get that “sound”. You just need the right tools and an understanding of how to

use them. You won’t become Bob Ludwig

dramatic improvements in your master recordings with a little work.

We put this document together to help others in their quest for better sounding masters. We

don’t claim to be mastering masters. If we could master the next Christina Aguilera hit would

we be writing code and manuals or sitting in a mastering studio with Christina Aguilera?

What we can give you is professional quality mastering software (iZotope Ozone™) and

guidance on how to use it. But in the end there are no right answers, no wrong answers, and

no rules. At least if there are, we still haven’t found them. So in the end just experiment and

have fun.

Intended Audience For This Guide

• If you don’t know anything about mastering and don’t have Ozone, we still

hope this guide will help you. Sure, we think you should use Ozone. But we

learned a lot about mastering from “the online audio community” and we

1

overnight (or probably ever) but you can make

1

http://www.gatewaymastering.com/ Bob Ludwig has won the TEC award for mastering every year he’s

been eligible. That pretty much sums it up.

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 4 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 5

want to give something back in return (in addition to iZotope Vinyl2). This

guide can be freely copied or distributed for noncommercial purposes for that

reason.

• If you don’t understand mastering but do have Ozone, you’re in luck. Ozone

gives you the tool to get “that sound” and this guide shows you how to do it.

• If you have Ozone and know the basics of mastering, this guide will stil l show

you tricks or techniques that are possible in Ozone. Just say “yeah, I knew

that” when appropriate for the other parts.

2

http://www.izotope.com/products/vinyl/vinyldx.html Analog modeli ng plug-in for lo-fi destruction. Tha t

pretty much sums that up.

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 5 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 6

WHAT IS MASTERING?

Although there are many definitions of what “mastering” is, for the purpose of this guide we

refer to “mastering” as the process of taking a mix and preparing it for manufacturing. In

general, this involves the following steps and goals.

The “Commercial Sound”

The goal of this step is to take a good mix (usually in the form of a stereo file) and put the

final touches on it. This can involve adjusting levels and in general “sweetening” the mix.

Think of it as the final coat of polish, or the difference between a good sounding mix and a

professional sounding master. This process can involve adding broad equalization, multiband

compression, harmonic excitation, loudness maximization, etc. This process is often actually

referred to as “premastering” but we’re going to refer to it as mastering for simplicity. Ozone

was created to specifically address this step of the process: to put that final professional or

“commercial” sound on a project that’s been mixed down to a stereo file.

Consistency across the CD

Consideration has to be made for how the individual tracks of a CD work together when played

one after another. Is there a consistent sound? Are the levels matched? Does the CD have a

common “character”? This process is generally the same as the previous step, with the

additional consideration of how individual tracks sound in sequence. This doesn’t mean that

you can make one preset in Ozone and just use it on all the tracks so that they all have a

consistent sound. Instead, the goal is to minimize the differences between tracks, which will

most likely mean different settings for different tracks.

Preparation for Duplication

The final step usually involves preparing the song or sequence of songs for manufacturing and

duplication. This step varies depending on the intended delivery format. In the case of a CD it

can mean converting to 16 bit/44.1 kHz audio through resampling and dithering, and setting

track indexes, track gaps, PQ codes, and other CD specific markings. Ozone is not designed to

address these functions by itself, but instead meant to work within dedicated products such as

Steinberg Wavelab, Sonic Foundry Sound Forge, Cakewalk SONAR, Adobe Audition (Cool Edit)

and others.

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 6 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 7

WHAT IS OZONE?

A Mastering System

Technically, Ozone is a plug-in, although it really encompasses several modules to

provide a complete system for mastering (or technically “pre-mastering” as it addresses the

processing but not the CD layout, file conversion, etc.) In addition to providing audio

processing, it provides meters, tools for taking snapshots of mixes, comparing settings, and

rearranging the order of the mastering modules within the system.

64-bit Audio Processing

When processing audio, Ozone can perform hundreds of calculations on a single sample of

audio. In a digital system, each of these calculations has a finite accuracy, limited by the

number of bits used in the calculation. To avoid rounding errors from interfering with the

audible portion of the audio, Ozone performs each calculation using 64-bits. Can you hear 64

bits? No. But that’s the point. The rounding errors (inherent not just in Ozone but in any

digital system) are pushed down into the inaudible range with Ozone.

Analog Modeling

Ozone is the result of extensive research in analog modeling, i.e. creating digital processing

algorithms that mimic the character of analog equipment. While it’s technically impossible to

model analog equipment exactly with digital 1s and 0s, Ozone provides compression,

equalization, and harmonic excitation that recreates the behavior exhibited by analog

equipment.

So what is this “character” of analog? There have been volumes written on this topic, and

we’re not sure if anyone really can explain it completely. But in the most general sense,

analog processing has certain nonlinear aspects that a mathematician would consider "wrong"

but many people believe sounds better musically. Any analog equalizer, for example, applies a

small phase delay to the sound. These types of “imperfections” provide the analog

characteristics of warmth, bass, sparkle, depth and just an overall pleasing sound.

Digital Precision

While analog modeling can provide a pleasant character or “colorization” of the sound, in some

situations precise or “transparent” signal processing is desired. For example, you may wish to

equalize or notch out a frequency without introducing the phase delay inherent in analog

filters as which was mentioned above. For these applications, Ozone also provides digital or

“linear phase” equalizer modes and multiband crossovers. Which should you use? It’s entirely

subjective, and with Ozone you have the choice of processing modes.

Meters and DSP

Some mastering engineers don’t need meters. They only need to listen. They can hear a

sound and know its frequency, or hear a level and know when it’s compressing. For the rest of

us, though, each module within Ozone combines audio processing controls with visual

feedback through appropriate meters. When equalizing, you can see a spectrum. When

compressing, you can see a histogram of levels. When widening, you can see phase meters.

There is no substitute for using your ears, but think of it like driving a car. When you first start

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 7 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 8

driving, you spend a lot of time looking at the speedometer. Over time, you develop an

instinct and need the meters less. But from time to time, we’ve all looked down and thought

“hmmm, I had no idea I was driving that fast”. Whether using Ozone or not, whether you’re

just starting with mastering or have been doing it for years, you can always benefit from the

second opinion that a good set of visual displays can provide.

UI Efficiency

A mastering session can be long and tiring. The last thing you need to be stressed about is

how to turn a knob with a mouse. There are no knobs in Ozone. It’s pure software, not

software stuck in some hardware paradigm of yesteryear

3

. Instead of spending time thinking

about how to make Ozone look like a 1960s compressor, we spent countless hours using it

and refining it to make it as usable as possible. It’s flat and simple with support for keyboard

shortcuts and wheel mice.

3

We’re not religiously against the hardware look. iZotope Vinyl has knobs and screws and brushed steel.

In a simple plug-in that can be fun, but Ozone had far too much depth to continue that “hardware”

paradigm.

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 8 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 9

GETTING SETUP FOR MASTERING

Software and Sound Card

To master on a PC you need some type of editing software and a sound card. There are plenty

of reviews and articles on software and sound cards, so we defer to other sources for you to

make your choice.

One important point is that when mastering you’re really just focused on improving a mixed

down stereo file. Applications such as Wavelab, Sound Forge, and Adobe Audition (Cool Edit)

are designed specifically for working with stereo files. However, you can bring a stereo file into

a multitrack program (i.e. SONAR, SAW, Samplitude, Vegas, Cubase, Nuendo, Logic, etc.) as a

single stereo track and master it that way. We caution you against doing mixing and

mastering in one step, though. That is, trying to master while also mixing the multitrack

project. While you could put Ozone as a master effect on a multitrack project, the first

practical problem is that this requires more CPU than necessary as the software is both trying

to mix your tracks as well as run Ozone (which does require more CPU than a typical plug-in).

The second problem is that you’re tempted to try to mix, master, arrange, and maybe even

rerecord in the same session. When we’re working we like the separation of recording/mixing

and mastering. You focus on the overall sound of the mix and improving that instead of

thinking “I wonder how that synth part would sound with a different patch?” Get the mix you

want, mix down to a stereo file, and then master as a separate last step

Mastering Effects

When mastering, you’re typically working with a limited set of specific effects.

• Compressors, limiters, expanders and gates are used to adjust the dynamics of a mix. For

adjusting the dynamics of specific frequencies or instruments (such as adding punch to

bass or warmth to vocals) a multiband dynamic effect is required, as opposed to a

single band compressor that applies to the entire range of frequencies in the mix.

• Equalizers are used to shape the tonal balance.

• Reverb can add an overall sheen to the mix, in addition to the reverb that may have

been applied to individual tracks.

• Stereo Imaging effects can adjust the perceived width and image of the sound field.

• Harmonic Exciters can add a presence or “sparkle” to the mix.

• Loudness Maximizers can increase the loudness of the mix while simultaneously

limiting the peaks to prevent clipping.

• Dither provides the ability to convert higher word length recordings (e.g. 24 or 32 bit) to

lower bit depths for CD (e.g. 16 bit) while maintaining dynamic range and minimizing

quantization distortion.

4

4

Like everything in this guide, this is just our suggestion based on the way we work (when we’re working

on music and not coding DSP). Work the way you work best.

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 9 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 10

We don’t think there’s any single “correct” order for effects when mastering. In Ozone, the

default order of the mastering modules (the path the signal follows through Ozone) is:

1) Paragraphic Equalizer

2) Mastering Reverb

3) Multiband Dynamics

4) Multiband Harmonic Exciter

5) Multiband Stereo Imaging

6) Loudness Maximizer

7) Dither

This order can be changed. In fact, you should experiment with different orders. The only

exception in all cases that we can imagine is that if you’re using the Loudness Maximizer and

Dither they should be placed last in the chain.

Bonus Tip: For a complete guide on dither, we invite you to check out our dithering guide at

http://www.izotope.com/products/audio/ozone/guides.html

To change the order in Ozone, click the “Graph” button.

This brings up a display of

the modules. You can

reorder the modules by

simply dragging them

around.

Note that the location of

the meters in the signal

chain can also be changed.

This allows you to set

whether the spectrum is

based on the signal going

into or coming out of the

EQ, for example.

Monitors

It’s important that you monitor on decent equipment when mastering. If your playback system

is coloring the sound, you can’t possibly know what’s in the mix and what’s caused by your

playback system.

That doesn’t mean that you can’t get decent results with relatively inexpensive equipment.

The key is knowing the limitations of what you’re monitoring on and learning to adjust for it in

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 10 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 11

your listening.

For studio monitors, the most common problem is lack of bass, specifically below 40 Hz or so.

These monitors just don’t have the size or mass to move that much air at that low a

frequency. One solution is to complement a pair of studio monitors with a subwoofer. If so,

make sure you adjust the subwoofer so that it doesn’t exaggerate the bass.

How do you do this? If you have a mic that’s flat down to 20 Hz, here’s a quick and dirty way

to do it.

1) Take a song with a good range of frequencies in it. We just randomly chose Vasoline

(Stone Temple Pilots)

say this was the quick and dirty method)

2) Put Ozone’s spectrum in average mode and loop a section of the song. Save it as a

snapshot (click the Snapshot button, click Snapshot button A and you’ll see a frozen

blue line)

3) Place the mic in the spot where you would be listening from, and play the loop through

the monitor/subwoofer combination. We used Cakewalk SONAR with effects on input

enabled, so that we could see the result in real time.

4) Adjust the subwoofer level until the sound picked up by the microphone (the green

line) is close to the spectrum of the source (the blue snapshot).

5

. As long as there’s a broad spectrum, it doesn’t matter (we did

It’s not exact and there are several variables here (the response and location of the

microphone being the most significant) but it can get you close.

You’ll never get a perfect listening environment, and you can never predict how what you’re

listening to will translate to the systems others will use to playback your song. With that in

mind, here are some tips we’ve picked up over the years for learning to master on studio

monitors:

1) Listen to music that you know well and have listened to on many systems. Spend

some time “getting to know” your monitors. Play your favorite CDs through them. You

probably know how these CDs sound on a home system, a car radio, etc. and this will

help you learn to adjust your listening for your monitors.

5

Not entirely randomly, as we lik e STP and the CD was nearby. But there’s no scien tific reason.

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 11 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 12

2) The bass will typically be under-represented on small studio monitors.

3) Monitors are very focused in terms of their soundfield, and the imaging is typically

more pronounced than on other systems.

Headphones

Heaphones are another option for monitoring. There are entire sites and forums dedicated to

headphones (such as http://headroom.headphone.com) so again we’ll leave our hardware

recommendations out of it and just advise you to ask around on forums.

When working with headphones, here are a few things to keep in mind.

1) Bass is sometimes under-represented on headphones, since bass on loudspeakers is

often perceived from physical vibrations (what you feel) as well as from the acoustics

(what you hear)

2) Imaging on headphones is very different than imaging on speakers.

3) Equalization can be very different on headphones compared to loudspeakers. The

listening room, your head and even your outer ear have filtering properties that alter

the frequency response of the music. This “natural equalization” is bypassed when you

listen on headphones. If you’re interested in learning more about this phenomenon,

look into “diffuse field” headphones.

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 12 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 13

SEVEN SUGGESTIONS WHILE MASTERING

Before you jump into a marathon mastering session, here are seven things that are good to

remind yourself of periodically.

1) Have someone else master your mixes for you. OK, in most project studios we realize

that the same person is often the performer, producer, mixer, and mastering engineer. At

least get someone else to listen with you. Or find someone who will master your mixes if you

master theirs. You’re too close to your own music. You’ll hear things other listeners won’t

hear, and you’ll miss things that everyone else does hear.

2) Take breaks and listen to other CDs in between. Refresh your ears in terms of what other

stuff sounds like. OK, the pros just instinctively know what sound they’re working towards, but

for the rest of us being reminded from time to time during the process isn’t such a bad idea.

3) Move your listening position. Studio reference monitors are very focused and directional.

The sound can change significantly depending on your listening position. Shift around a bit.

Stand across the room for a moment.

4) Listen on other speakers and systems. Burn a CD with a few different variations and play it

on your home stereo system, or drive around and listen to it in your car. Don’t obsess over

the specific differences, but just remind yourself what other systems sound like.

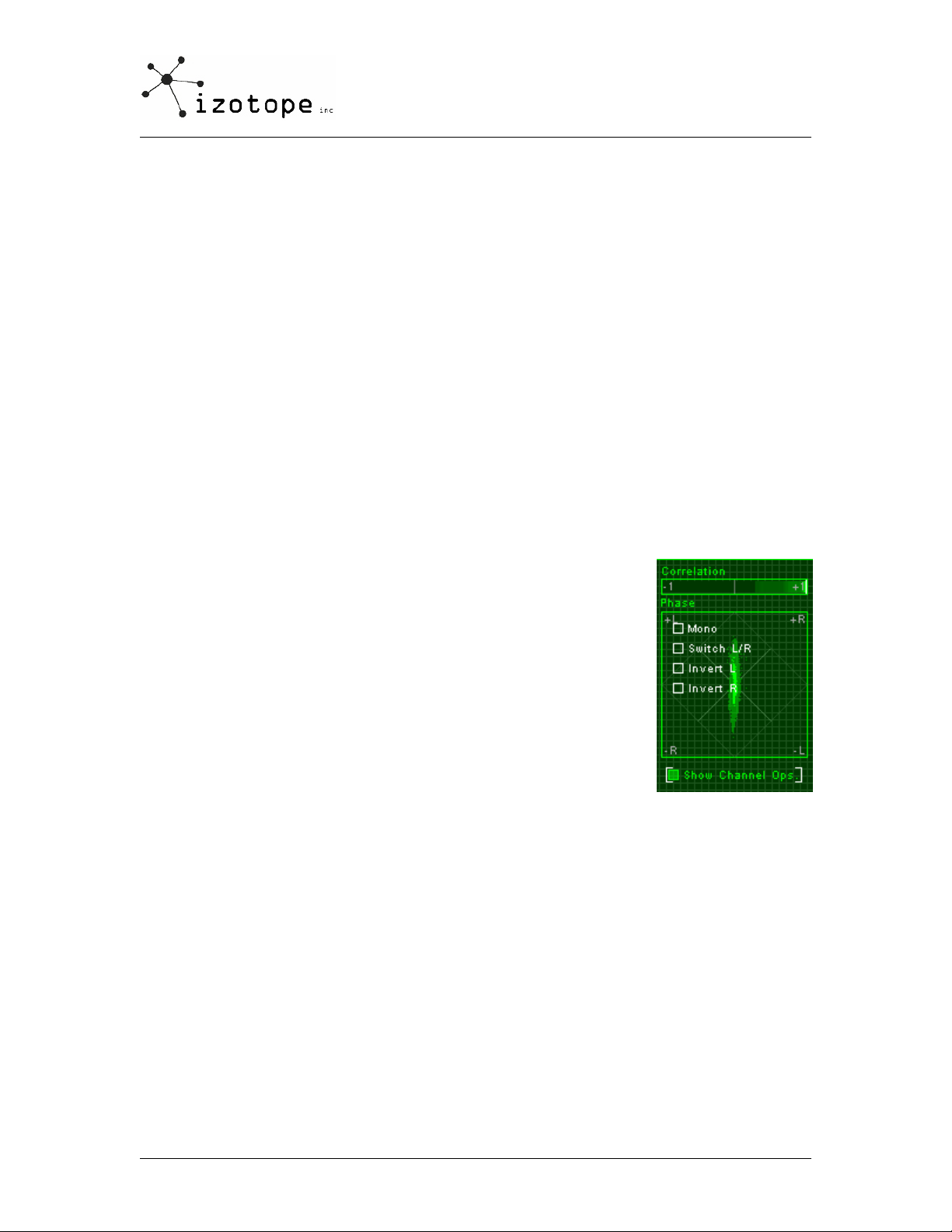

5) Check how it sounds in mono. Check how it sounds with the polarity

inverted on one speaker. People will listen to it this way (although

maybe not intentionally) and while your master probably won’t sound

great this way hopefully it won’t completely fall apart either. Ozone

provides a quick check for this by clicking on the Channel Ops button.

You can quickly switch to mono, switch left and right speakers, and flip

the polarity of speakers.

6) Monitor at normal volumes, but periodically check it at a higher

volume. When you listen at low to medium volumes, you tend to hear

more midrange (where the ear is most sensitive) and less of the lows

and highs. This is related to something called the Fletcher-Munson

effect, which involves how different frequencies are heard differently

depending on the playback volume. So check from time to time how it

sounds at different volume levels.

7) When you think you’re done, go to bed, and listen again the next morning.

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 13 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 14

EQ

A reasonable starting point when mastering is equalization. While most people understand

how equalizers work and what they can do, it’s not always easy to balance a mix with one.

What’s the Goal of EQ when Mastering?

When we’re trying to get our mixes to sound good, what we’re shooting for is a “tonal

balance”. Any instrument specific equalization has hopefully been done during arranging and

mixdown, so we’re just trying to shape the overall sound into something that sounds natural.

Sometimes that’s easier said than done, but there are some general techniques you can use to

get a decent tonal balance.

EQ Principles

Here’s a basic review of the principles of equalizers before jumping into the process.

There are many different types of equalizers, but they are all meant to boost or cut specific

frequencies or ranges of frequencies. Our focus here is on parametric equalizers, which

provide the greatest level of control for each band.

Parametric EQs are typically made up of several bands. A band of EQ is a single filter. You can

use each band to boost or cut frequencies within the range of the band. By combining bands,

you can create a practically infinite number of equalization shapes.

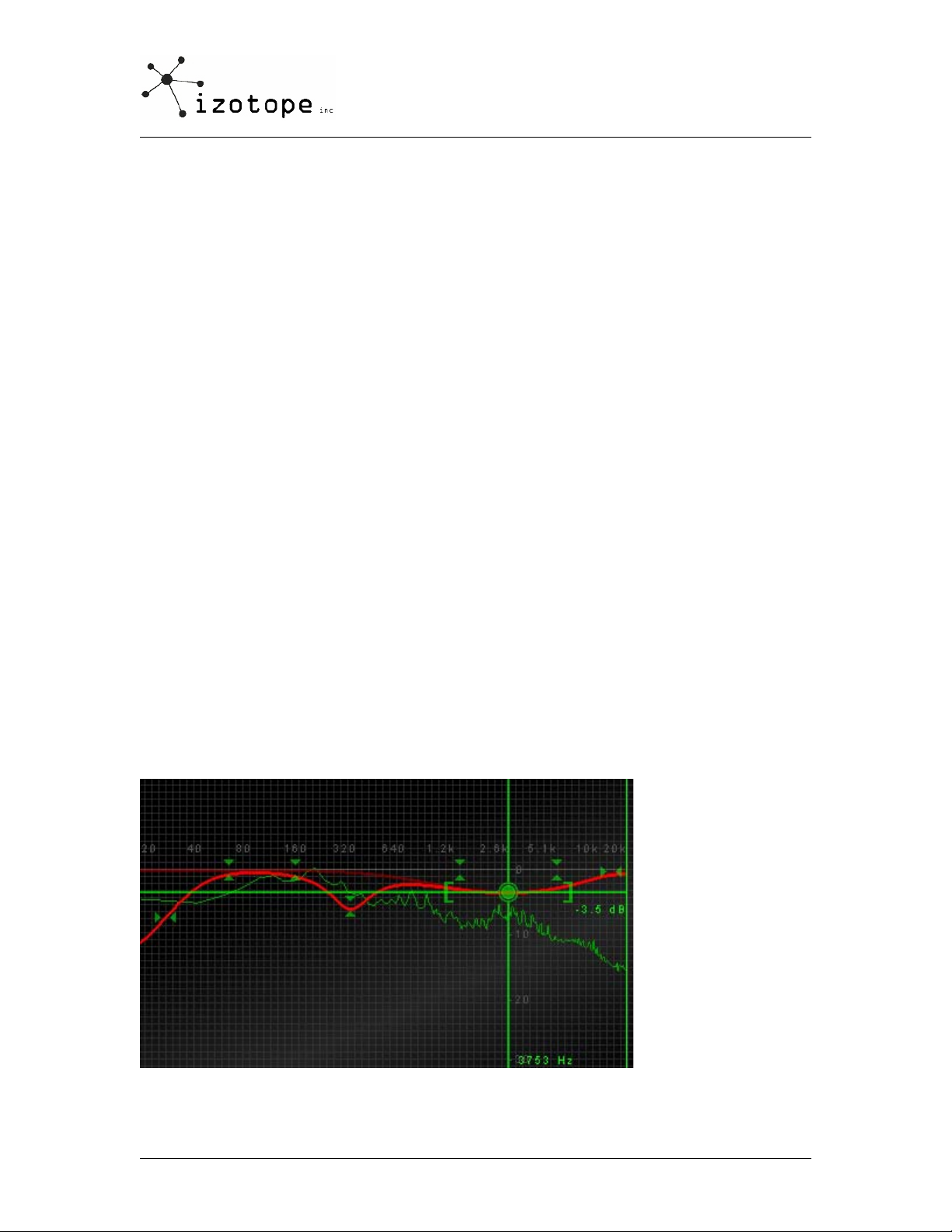

The picture below shows the equalizer screen in Ozone, but the principles are the same for

most parametric EQs. There are 8 sets of arrows, which represent 8 bands of equalization.

One band is selected, and has been dragged down to cut the frequencies in the range of 3753

Hz by –3.5 dB.

The bright red curve shows the composite or overall effect of all the bands combined. The

darker red curve shows the effect of the single band that’s selected.

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 14 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 15

Each band of parametric equalization typically has three controls:

Frequency

The center frequency dictates where the center of the band is placed.

Q and/or Bandwidth

Q represents the width of the band, or what range of frequencies will be affected by the band.

A band with a high Q will affect a narrow band of frequencies, where a band with a low Q will

affect a broad range of frequencies.

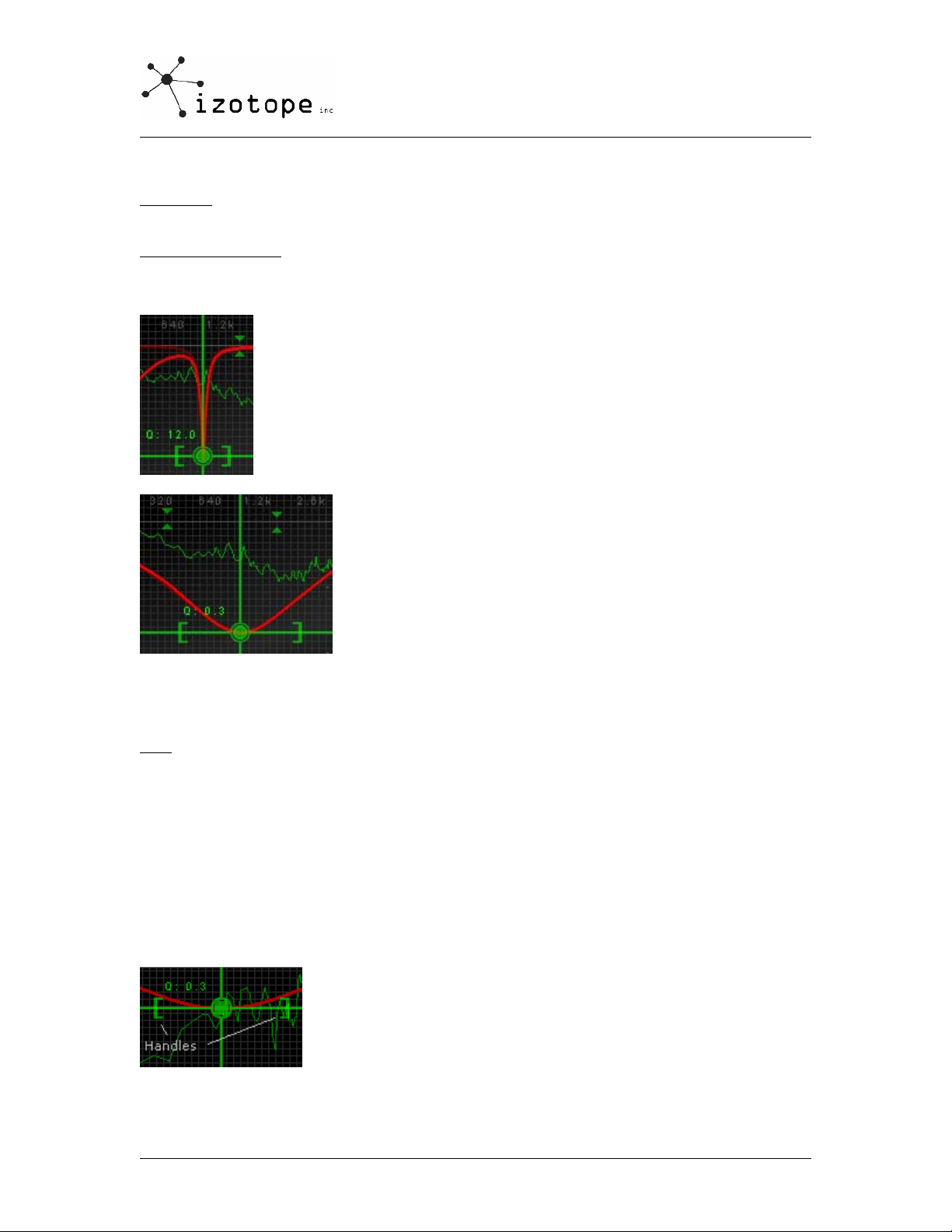

A Narrow Filter (Q=12 )

A Broad Filter (Q=0.3)

Q and bandwidth are related by the formula Q=(filter center frequency)/(filter bandwidth). So

as Q gets higher, the bandwidth of the filter gets narrower.

Gain

This determines how much each band boosts (turns up) or cuts (turns down) the sound at its

center frequency.

Using the Ozone Paragraphic Equalizer

Ozone includes a parametric equalizer presented in a graphical way, which is often referred to

as a paragraphic equalizer.

The paragraphic equalizer has 8 adjustable filter bands which can be used to boost or cut

frequencies. To adjust the gain of a band, you grab the center and move up or down. To

adjust the frequency, you drag left or right.

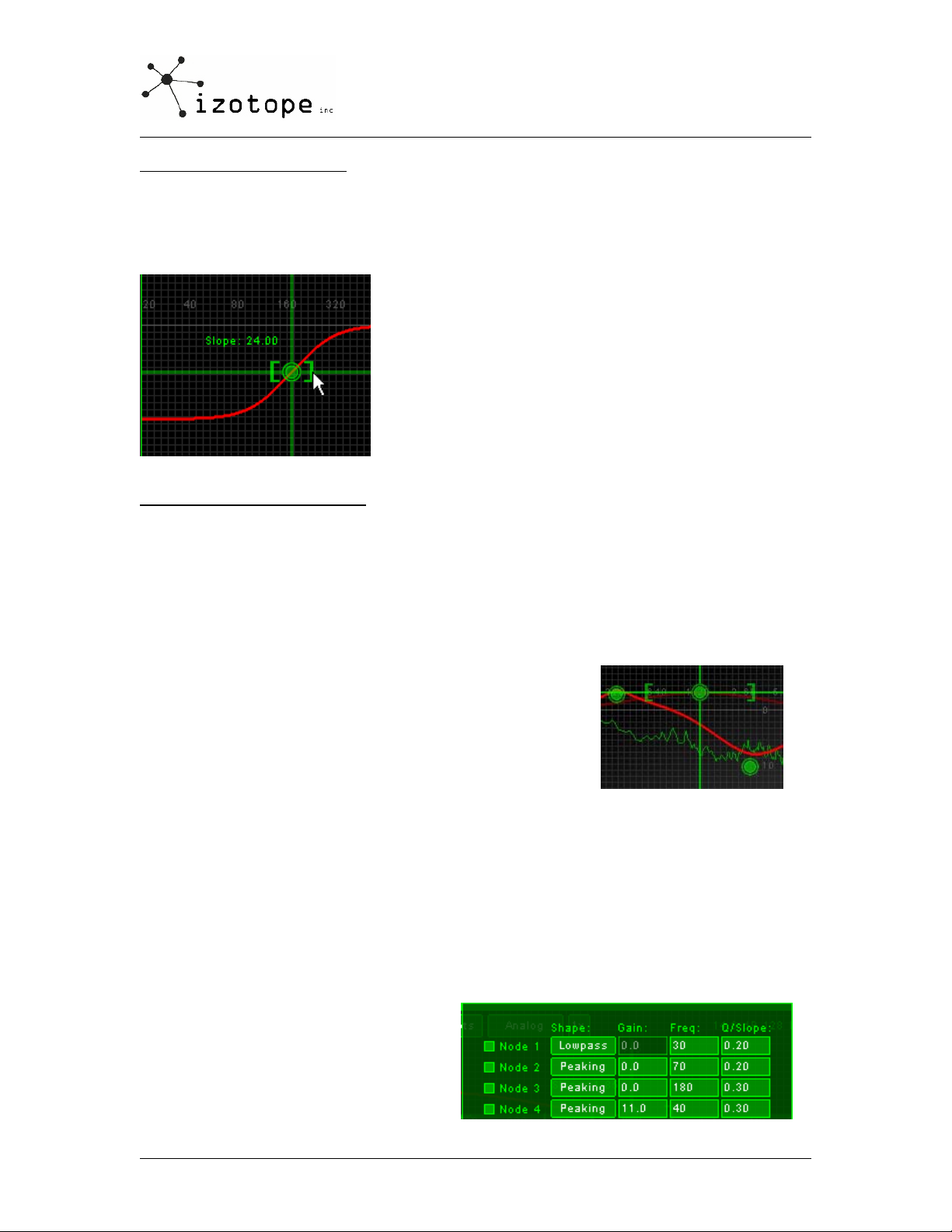

To adjust the Q or width of a band, you can grab the side handles of

the band and drag them apart.

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 15 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 16

EQ Shapes

Any of the eight filters in Ozone can be configured to be a bell (also referred to as a peak

filter), lowpass, highpass, lowshelf or highshelf. You can specify the shape of a filter by

clicking on the “Show Info” button and selecting a different shape for the filter from the table.

Bell Filter

As shown below, a bell filter has a width (Q) as well as a gain. The gain can be positive or

negative – to boost or cut the specified range of frequencies within the bell.

Lowpass and Highpass Filters

Unlike a Bell Filter, Lowpass and Highpass filters only have one “side” to them. You specify the

point that you want to start attenuating frequencies, and any frequencies below that point (for

a highpass filter) or above that point (for a lowpass filter) are filtered. The Q control for

lowpass/highpass filters specifies the slope of the filter, with lower Q values providing more

gradual rolloff.

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 16 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 17

Lowshelf and Highshelf filters

Like lowpass/highpass filters, these filters also are “one sided”. Shelf filters, however, don’t

drop off indefinitely. Instead, they resemble, well, a shelf, as you can see below. In this case,

the horizontal handles provide a slope control which specifies how tall the shelf should be – or

how much cut should be applied before leveling off to a constant (horizontal) line.

Controls for Adjusting EQ Bands

In addition to basic mouse support, Ozone supports the following controls for adjusting EQ

bands:

1) You can use the arrow keys to adjust a band up/down or left/right. If you hold down

the Shift key when using the arrow keys the adjustment is accelerated.

2) You can adjust the Q of a band by using the wheel of a wheel mouse or the

PgUp/PgDn keys.

3) You can select multiple bands by holding down the Ctrl

key and clicking multiple bands. To adjust them as a

group, drag the first band selected and the rest will

move with appropriate relative motion (or use arrow

keys to move the entire group). This is useful if you

have an overall shape that you like but want to raise

or lower the gain of the entire curve.

4) If you hold down the Alt key and click on the spectrum, you have an audio magnifying

glass that lets you hear only the frequencies that are under the mouse cursor, without

affecting your actual EQ settings. This is useful for pinpointing the location of a

frequency in the mix without messing up your actual EQ bands. Releasing the mouse

button returns the sound to the actual EQ. You can set the width of this filter in the

Options dialog.

5) If you hold down the Shift key and drag an EQ band, the EQ band will be "locked" in

the direction that you're dragging. So if you just want to change the gain without

affecting the frequency (or vice versa) just hold the Shift Key while you drag.

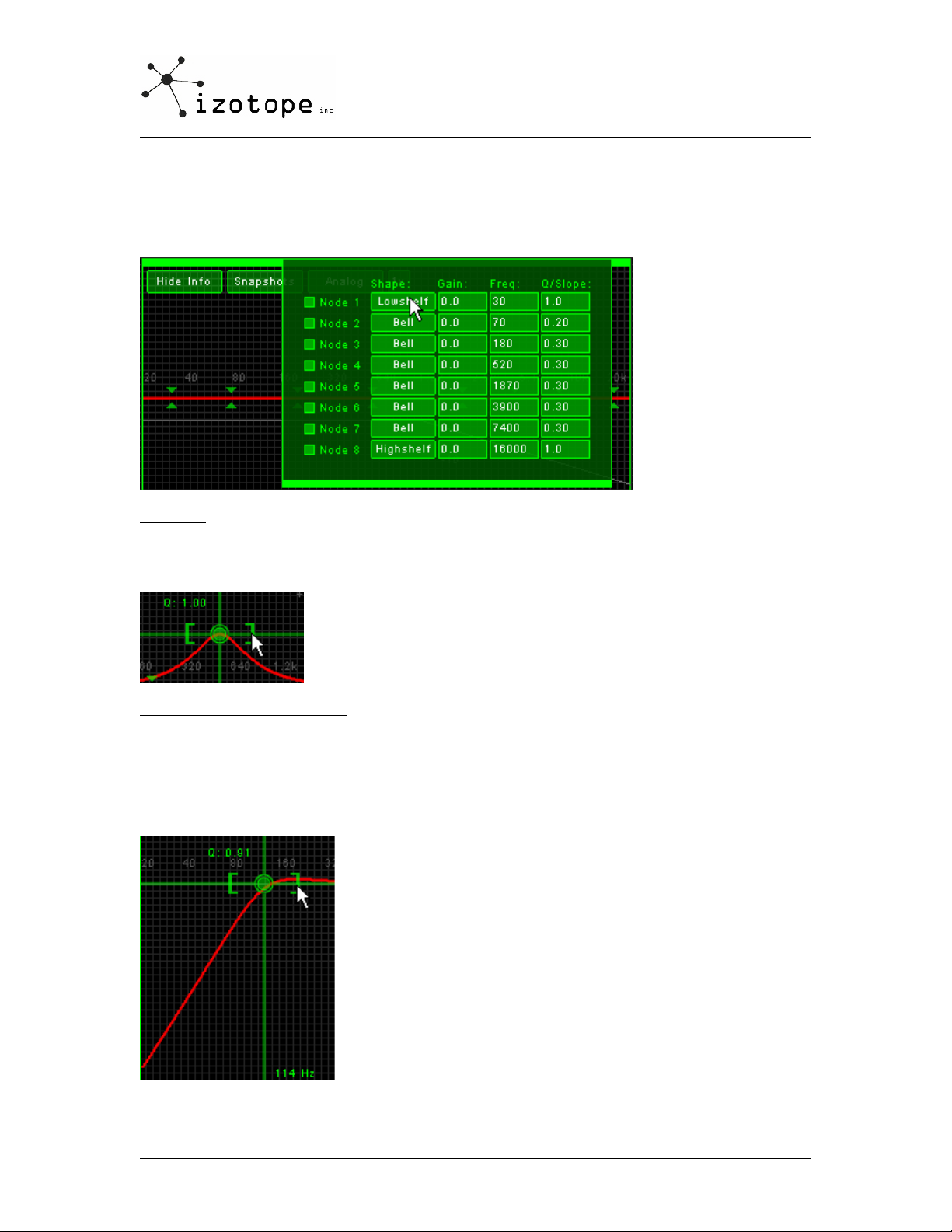

6) If you'd rather use numbers as

opposed to visual EQ bands,

clicking on the Show Info button

gives you a table view of the EQ

band settings. You can enter

values for the EQ bands directly in

this table, or simply position the

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 17 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 18

cursor over a value and change it by turning the wheel of a wheel mouse. You can also

disable bands with this table by clicking on the square box to the left of a band.

7) You can select the shape of a filter by holding down the Ctrl key and right clicking on

the EQ filter. This will cycle it through the lowpass, highpass, bell, lowshelf, highshelf

shape options.

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 18 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 19

EQ the Midrange

So you’re ready to EQ. Now what?

Listen and try to identify any problems that you hear. Start with the midrange (vocals, guitar,

midrange keyboard, etc.) as this will typically represent the heart and soul of the song. Does it

sound too “muddy”? Too nasal? Too harsh? Compare it to another mix, perhaps a commercial

CD. Try to describe to yourself what the difference is between the two mixes around the

midrange.

Too muddy?

Try cutting between 100 to 300 Hz (Band 2 in Ozone is set at 180 Hz by default. Try cutting

the gain a few dB using this band)

Too nasal sounding?

Try cutting between 250 to 1000 Hz. (Band 3 in Ozone is set by default at 520 Hz for this

purpose)

Too harsh sounding?

This can be caused by frequencies in the range of 1000 to 3000 Hz. Try cutting this range a

few dB. (Band 4 in Ozone is set at 1820 Hz for this purpose)

Hopefully, using a band or two in these regions will give you a better sounding midrange.

Remember that you can use the Alt-click feature to focus just on specific ranges and highlight

what you’re hearing. Another common technique is to start by boosting a band to highlight a

region of the spectrum, and then cutting it once you’ve centered on the problem area.

You’ll get the most natural sound using wide bands (Q less than 1.0). If you find yourself using

too narrow a notch filter, or too much gain, you may be trying to fix something that EQ on a

stereo mix can’t fix. Go back to the individual tracks and try to isolate the problem that way.

Note also that the wider the band, in general the less gain you need to apply.

In addition, your ears quickly get used to EQ changes.

You may find yourself boosting more than necessary to

hear the difference. Use the History window (click on

the History button) to go back and audition settings

prior to making changes. Comparing the difference

before and after a series of subtle EQ changes can help

prevent you from overdoing boosts or cuts.

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 19 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 20

EQ the Bass

In comparing your mix to commercial mixes at this stage, you’re probably tempted to boost

the bass using the equalizer. Resist the temptation. Don’t worry, your mix will get that low

end punch, but we’ll do it using a multiband compressor.

A reasonable use of EQ in the low end is to apply a shelf or

highpass filter below 30-40 Hz. Purists might find this alarming, as

yes, we can hear down to 20 Hz and some musical information can

be lost. Typically what people consider “bass” though is in the 50100 Hz region, and the audio in the 20-40 Hz range can usually be

rolled off. The benefit is that you can remove some low frequency

rumble and noise that could otherwise overload your levels.

Keep in mind that for bass, or any EQ change for that matter, every action has an opposite

reaction. If you increase one frequency, you can mask another frequency. The flipside of this

is that cutting one frequency can be perceived as a boost to another frequency. Each change

that you make can affect the perception of the overall tonal balance of a whole.

Bass guitars and kick drums can span a wide frequency range. Where the “oomph” of the kick

drum can be centered around 100 Hz, the attack is usually found in the 1000-3000 Hz region.

Sometimes you can get a sharper sounding “bass” sound by focusing on the higher frequency

attack, as opposed to the 100 Hz region which can cause “mud”.

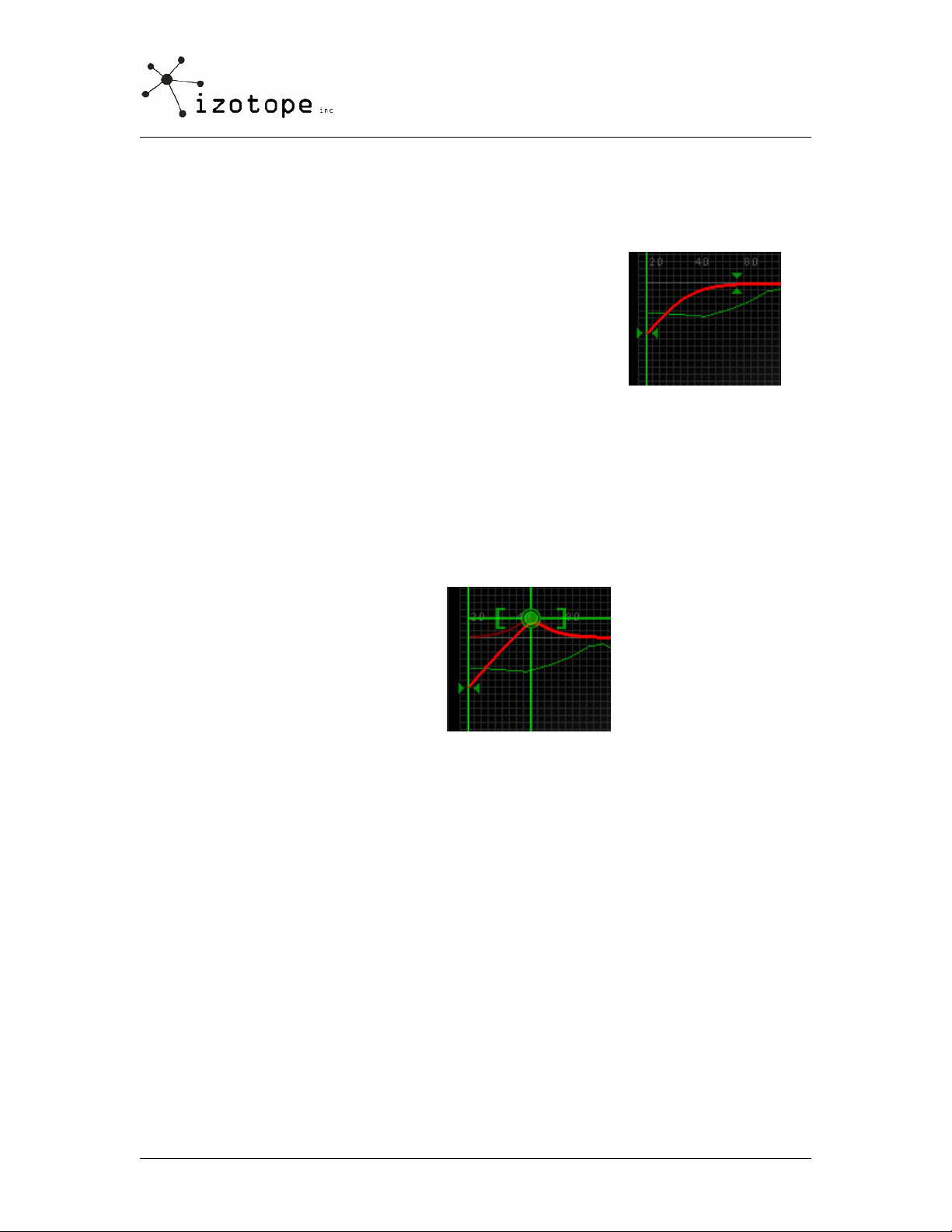

On the other hand, if you want to add

that hip-hop style “ring” to the bass, try

a peak at 50-60 Hz as shown to the

right.

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 20 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 21

EQ the Highs

Finally, take a listen to the higher end frequencies in your mix.

- Don’t be surprised if when comparing your mix to commercial CDs yours sounds a little dull

or muffled. You could compensate for this with some high frequency EQ, with a low Q (wide

bandwidth) band around 12-15 kHz. Alternatively, you could skip the EQ and add some

sparkle and shine using a multiband harmonic exciter.

- Be careful boosting around 6000-8000 Hz. You can add some “presence” in this area, but you

can also bring out an annoying sibilance or “ssss” sound in the vocals. (note: see the section

on multiband dynamics for “de-essing” or sibilance control)

- Noise reduction is a huge topic in itself, but you can sometimes reduce tape hiss or other

noise by cutting high frequencies around 6000 to 10000 Hz. (You can also approach noise

reduction using multiband gating, or dedicated noise reduction tools)

-A generally pleasing tonal balance is a high frequency spectrum that rolls off gradually.

Shown below is a “signature” spectrum that many commercial recordings exhibit. The song

used in this case was Little Feat’s “Hate to Lose Your Loving”, but if you have Ozone try

analyzing a few CDs with the spectrum in average mode and you’ll probably be amazed at how

many follow the same slope.

This signature is so common that we built into Ozone

the ability to overlay this line on the spectrum.

Click on the Snapshots button from the Paragraphic EQ

screen and select the “6 dB guide”. The sloped yellow

line will appear as a guide for equalizing the high

frequencies of your mix.

For a brighter reference, you can alternatively select

the “Pink Guide” which provides a 3 dB reference

characteristic of many newer pop recordings.

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 21 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 22

EQ’ing with Visual Feedback

The key to setting the tonal balance of a mix with an EQ is developing an ear for what

frequencies correspond to what you’re hearing. The most appropriate visual aid in this case is

a spectrum analyzer.

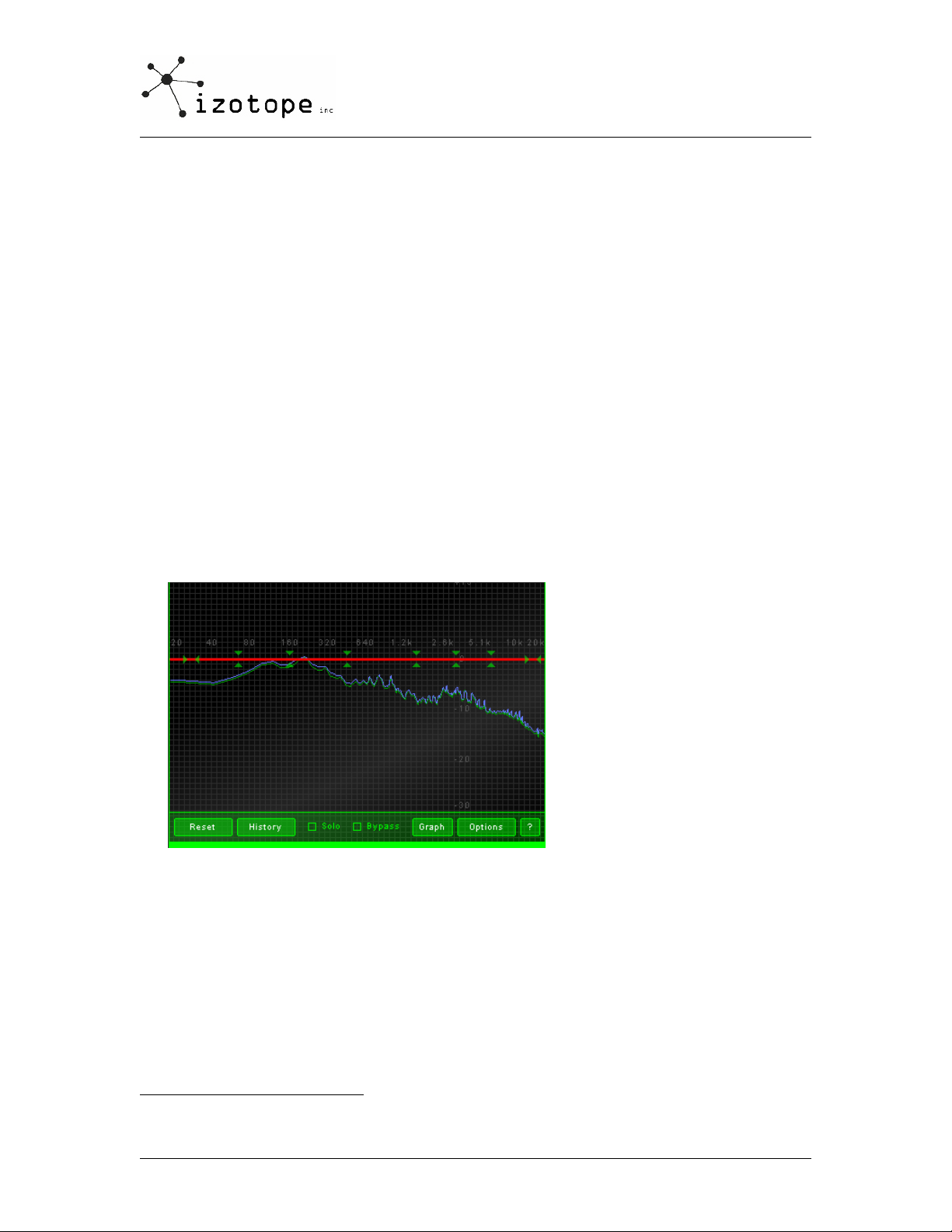

The spectrum analyzer from Ozone is shown below, although others provide similar views and

options. The green line represents the spectrum or FFT, calculated in real time, ranging from

20 Hz to 20 kHz, the range of human hearing.

Peaks along the spectrum represent dominant frequencies. In the case of the song above, you

can see a dip in frequencies between 20 and 160 Hz, which could be compensated by using

low frequency EQ or bass compression.

Spectrum Options

Converting audio into a spectrum representation involves several calculations. You can specify

options related to these calculations by right clicking on the spectrum and selecting the

“Spectrum Options” menu.

Spectrum Type

Ozone allows you to select between linear, third octave and critical band spectrums. Linear

spectrum is a continuous line connecting the calculated points of the spectrum, as shown

below

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 22 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 23

A 1/3 octave display splits the spectrum into bars with a width of 1/3 of an octave as shown

below. Although the spectrum is split into discrete bands, this option can provide excellent

resolution at lower frequencies.

The critical bands option splits the spectrum into bands that correspond to how we hear, or

more specifically how we differentiate between sounds of different frequencies. Each band

represents sounds that are considered "similar" in frequency. A critical band representation is

shown below.

Peak hold: Allows you to show and hold the peaks in the spectrum. (note that in Ozone you

can reset the peak hold at any time by clicking on the spectrum).

Average time: If you’re concerned with peaks or short frequencies you can run the

spectrum real time mode. For comparing mixes and visualizing the overall tonal balance,

Ozone also provides an averaging mode. Instead of overwriting the display of old samples with

new samples, Average mode averages new samples into the prior samples to provide a

running average of the tonal balance. You can reset the average at any time by clicking on the

spectrum.

FFT Size: Without getting into the math, the higher the FFT size, the greater frequency

resolution. An FFT size of 4096 is usually a good choice, although you can go higher if you

want better resolution, especially for focusing in on lower frequencies.

Overlap and Window: These are more advanced options that determine how the window of

audio is selected and transformed into a frequency representation. In general an Overlap of

50% and a Hanning window will give good results.

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 23 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 24

Bonus Tip: You can turn off the spectrum display from the Ozone main options dialog to

conserve CPU or to minimize visual distraction.

Snapshots

Spectrum snapshots are powerful tools for comparing the tonal balance of your mix to other

songs. In Ozone, these snapshots can be accessed by clicking on the Snapshots button.

You have access to eight Snapshots, marked with the buttons labeled A through H. Clicking on

a button takes a snapshot of the spectrum at that instant in time. You can show individual

snapshots by clicking the “Show” checkbox below each Snapshot button.

In most cases, you should use Snapshots when the spectrum is in Average Mode. This will

allow you to compare overall tonal balance without being distracted by short peaks.

Digital or Analog EQ

Analog filters, as mentioned before, impart a character or colorization on the sound. If

precision is your goal, you can toggle to digital linear phase filters as shown below.

The selection is a matter of taste, although in general (or in our opinion) analog filters provide

an excellent sound when applying slight boosts or cuts, while the “transparency” of digital

linear phase filters is useful when applying deep or narrow “surgical” cuts.

When working with digital linear phase filters, Ozone provides a choice of resolution for the

filters. Right click on the EQ screen, select Equalizer Options from the menu, and you’ll be

presented with an Equalizer options screen. The “Digital EQ FFT Size” specifies the resolution

or precision of the digital equalizer, with higher values providing more precise filtering.

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 24 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 25

Bonus Tip: Ozone uses several "digital" algorithms - such as the digital EQ and digital

multiband crossovers - that result in a delay of the signal. That is, Ozone needs some time to

"work on" the audio before it can send it back to the host application. That time represents a

delay when listening or mixing down. Fortunately, many applications provide "delay

compensation" - a means for Ozone to tell the application it has delayed the signal, and the

host application should "undo" the delay on the track. You can access this option in the main

Ozone options screen.

If your host application supports delay compensation, select

this option. If your application doesn't support it, or

skips/stutters with this option on, you can always manually

correct the delay offset in the host application (i.e. manually

edit out the short delay of silence). To help you perform m

correction, in the lower left corner of the options screen Ozone

will display the delay (in samples) that has been introduc

the processed signal.

Matching EQ

If you’re following the concepts of spectrum snapshots, 6 and 3 dB guides, etc. you realize

that one way of approaching EQ is to try to match your spectrum to a known “good” spectrum.

Given that, you’re probably thinking “well, if Ozone knows what the good spectrum looks like,

and what my spectrum looks like, why can’t it just setup the EQ for me to match the two?” We

agree, and Ozone also provides an automatic “Matching EQ” that does exactly that.

anual

ed to

The Matching EQ works hand in hand with spectrum snapshots to "borrow" the spectrum of an

audio clip and apply it to another. Therefore, the first step is to take snapshots of two

spectrums - the mix you want to EQ (we call that the "Source") and the recording that has the

spectrum you want to match (we call that the "Target").

1) Load the Target file - that is, the mix that you want to use for your EQ curve - in your host

audio application.

2) Right-click on the main window of the EQ module to bring up the spectrum options. Set the

averaging time to Infinite, as shown below.

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 25 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 26

What this does is puts the spectrum in an infinite averaging mode. Instead of displaying the

real-time spectrum, it will calculate and display an overall average spectrum for your mix.

While this isn't technically necessary for using the Matching EQ, you most likely want to match

the overall spectrum of a mix, as opposed to an instantaneous spectrum.

3) Click OK to close the Spectrum Options.

4) Open the Snapshot window by clicking on the Snapshot button as shown below.

5) Start playing your file. You'll see the spectrum "dance around" to begin with, but since it's

in infinite averaging mode it will most likely stabilize to some average value after a few

seconds.

6) Click the A button in the Snapshot window and the spectrum will be captured as Snapshot

A. Select "Target" for Snapshot A.

7) Load your Source file in your audio app, play it, and click the B button in the Snapshot

window to save it as Snapshot B. Select "Source" for Snapshot A.

8) Set the Matching Amount and Smoothing sliders to 0. Your screen should look like the one

below (although your actual spectrum will of course be different)

You're now ready to match the EQ.

9) Set the EQ mode to Matching, as shown below.

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 26 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 27

10) Open the Snapshots windows again. Play your Target file, increase the Matching amount

slider, and your Target file will be EQ'd to match the Source.

As you increase the Matching amount, you'll notice a red EQ curve appearing. Most likely, the

more you increase the Matching amount the more "jagged" this Matching EQ curve will

become, with increasing peaks and valleys.

A Matching amount of 100% and a Smoothing amount of 0 might be technically the closest

match to your Source, but in reality it's probably not the most effective combination of

settings. Those settings will try to capture every peak, valley and level, which can result in

extreme (unnatural) EQs.

Instead, we suggest working with the Matching amount around 50%. If your Matching EQ

curve has narrow peaks and valleys, increase the Smoothing parameter to, well, smooth them

out. Your goal is to capture the overall tonal shape of the Source - an overall tone as opposed

to an exact match.

11) Adjust manually as necessary. Close the Snapshots window, and you'll notice that you can

still use the manual EQ nodes to further adjust the equalization. It may not be necessary, but

feel free to further "season to taste" manually.

Bonus Tip: You can get help at any point while using Ozone by clicking on the “?” button as

shown below. Ozone will automatically launch its help file, and open it to the page that

corresponds to the module that you’re currently using.

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 27 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 28

General EQ Tips

1) Try cutting bands instead of boosting them.

2) Cutting or boosting more than 5 dB means you probably have a problem that you can’t

fix from the stereo master. Go back to the multitrack mixing step.

3) Use as few bands as possible

4) Use gentle slopes (wide bandwidth, low Q).

5) Shelve or highpass filter below 30 Hz to get rid of low frequency rumble and noise.

6) Try using bass dynamics (i.e. multiband compression) instead of boosting low EQ if

you’re trying to add punch to the bass or kick.

7) Try bringing out instruments by boosting the attacks or harmonic frequencies of the

instrument instead of just boosting their fundamental “lowest” frequency. If you try to

bring out the fundamentals of every instrument your mix will just sound like mud.

8) Try using multiband harmonic excitation instead of boosting high EQ to add sparkle or

shine. This, like everything in this guide, is purely subjective. Compare harmonic

excitation to the effect of a gentle sloping EQ boost around 12-15 kHz.

9) Use your ears and your eyes. Compare to other mixes using both senses.

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 28 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 29

MASTERING REVERB

What’s the Goal of Reverb when Mastering?

If you’ve done a good job with reverb on the individual tracks and as a result have a cohesive

sense of space, you probably won’t need to add any additional reverb to the final mix. In some

cases, however, a little mastering reverb can add an overall finish to the sound. For example:

1) A recording made “live” in an acoustic space might have troublesome decays or room

modes. In this case, a coat of reverb to the final mix can help smooth over any

imperfections in the original acoustic space.

2) A short reverb can add fullness to the mix. In this case, you’re not trying to add more

perceptible space to the mix, but instead creating a short reverb at a low level that

fills in the sound.

3) In some cases, you don’t have a good sense of ambience or cohesive space in the mix.

Each track or instrument might have its own space, but they don’t seem to gel

together in a common space. Mastering reverb can be used as a “varnish” in this case

to blend together the tracks. Yes, this is a type of band-aid for glossing over a mix,

but sometimes that’s all you can do.

Reverb Principles

In the simplest sense, a reverb simulates the reflections of sound off walls by creating dense

echoes or delays of the original signal. Since walls absorb sound over time, the delays or

reflections in a reverb decay over time. In addition, as the signal is delayed or reflected over

time, the number of echoes increases (although decreasing in level) and you hear a “wash” of

sound as opposed to individual echoes.

There are many types of reverbs, from plates to springs to reverse reverbs to gated reverbs.

In the context of mastering, we (iZotope) tend to separate reverbs into two categories: Studio

and Acoustic. This isn’t a technical definition, but more of a way of thinking about reverb.

Acoustic reverbs

(tracks) in a virtual room, these are excellent choices. You can clearly hear the “early

reflections” from the original signal echoing off the nearest walls, and decaying into a space

with later reflections. You also have a clear sense of the “positioning” of the track in the room.

Studio reverbs on the other hand are artificial simulations of rooms, and while they may not

sound as natural as an acoustic reverb they have been used so much on commercial

recordings that we have come to accept and even expect them. Do they sound like a real

room? No. They are an effect of their own, and they give an overall sheen or “lush” ambience

to a song. You don’t picture the musicians performing in a real acoustic space, but instead

experience a wash of ambience. You can overdo it and it can wash your mix right down the

drain, but just a touch can wash away any imperfections in the original mix and give it a nice

sheen.

Using the Ozone Mastering Reverb

Ozone provides both acoustic room and plate “studio-style” reverbs that you can apply to your

mixes. They are both 64-bit algorithms – the plate mode providing a thick or lush sound and

the room mode providing a natural or acoustic sense of space.

simulate a realistic acoustic space. For placing individual performers

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 29 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 30

The Ozone mastering reverb was also designed to provide you the controls you need, and just

the controls you need, for optimizing your mixes. There are no gate, reverse or other “special

effect” reverb controls that might be great for individual tracks, but not for overall mixes.

Think of it almost as a “coating” reverb for track reverb.

The best way to become familiar with the sound is to load up a song, solo the reverb module

(so you only hear the effect of the reverb processing) and solo the reverb signal so you don’t

even hear the original direct mix. You only hear the reverb.

First of all, turn up the Wet fader. This controls the amount of reverb that is being mixed back

into your mix. Adjust it to a comfortable listening level to go through this section of tutorial,

which will probably be much higher than what you would want if you were actually adding this

much reverb back into your mix.

Room or Plate

This button allows you to select between the acoustic room reverb and the studio plate reverb.

As mentioned above, the plate mode provides a thick or lush sound while the room mode

provides a more natural acoustic sense of space.

Room Size

In an “acoustic” sense, this controls the overall size of the room – or to be technical it controls

the “decay time” of the reverb. Higher values will give longer reverb times, as it will take

longer for the sound to decay.

• If you’re trying to “wash over” a mix, you’ll probably want to try values in the range of

0.3 to 0.6 for this fader. As a general tip, if your mix already has reverb on the

individual tracks (which it probably does) try to set the room size of length of the

reverb slightly longer than the reverb on the original tracks. You can always adjust the

level of the mastering reverb with the Wet slider, and a longer decay time on the

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 30 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 31

overall mix will blend things together better. In general, if we’re going to apply

mastering reverb we usually end up with Wet around 5.0 to 15.0 (and Dry at 100.0)

• Another interesting effect to play around with is to use a small room size, anywhere

from 0.1 to 0.3, and turn up the wet slider a little more to 20 or 30. In some cases

this can create a fuller sound by adding a short reverb or doubling to the mix. It can

also make some mixes sound terrible. (listen before you send it to the duplicator)

You’ll also want to keep the Room Width at 1.0 if you use this effect, as spreading out

an extremely short reverb wouldn’t be very natural since you’d be creating a small

room with wide walls, which just doesn’t make sense (or sound good)

.

Room Width

The Ozone mastering reverb is of course a stereo reverb. It doesn’t return the same reverb

signal in the left and right channels, as this would sound unnatural, and not what would

happen in a room. Instead, it creates a nice spacious “diffuse” sound by returning slightly

different left and right channels of reverb. The Room Width slider lets you control how

different the left and right channels will be. In an “acoustic” sense, you perceive this as the

width of the room, or at least the width of the reverb signal.

• In most cases, you’ll want the width to be from 1.0 to 2.0.

• As you turn up the width, you’ll tend to perceive more reverb. At higher room widths,

try turning down the room size. This might seem counterintuitive, but give it a listen

(turn up the width to an extreme of 3.0) and you’ll hear what we mean. The ideal

balance is, well, a balance between the two.

Damping

In a real room, the sound decays as it bounces off the walls. But not all frequencies decay at

the same rate. A padded cell

Different rooms and wall materials have different absorption properties, and the Damping

control lets you control the characteristics of the high frequency decay of the signal.

• Lower damping settings will result in a brighter sounding reverb. Higher values are,

well, less bright.

• We typically use Ozone with the Damping set from 0.5 to 0.8.

Predelay

Predelay sets the amount of delay in milliseconds between the original signal and the

beginning of the reverb. Consider a large room – you’ll only hear the first bit of reverb after

the original signal has gone out to a wall, bounced off it, and come back to your ears. The

length of time before you hear this initial reflection is controlled with the predelay slider.

High and Low Cutoffs

You may have noticed that the mastering reverb has a spectrum with two vertical lines on it.

These vertical lines are not the same as the multiband controls found in the multiband

6

Not that we’ve actually been in a padded cell, but that’s how we imagine it would sound.

6

would decay the high frequencies faster than a bathroom.

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 31 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 32

modules, but instead control the rolloff of the reverb signal in this module.

You can drag the lines to the left or right to change the bandwidth of the reverberated signal

that is returned and mixed back into your mix. The area between the lines will be the reverb

signal that you hear.

Note: As you drag the handles, wait a second to let the filters fully affect the signal. The

reverb in Ozone uses analog modeled cutoff filters that have a time constant. The downside is

that it takes a second or two after you move a cutoff to hear the fully processed result. The

upside is that they sound smooth and “musical”.

So where should you put the cutoffs? Well, the mastering reverb in Ozone rolls off with high

frequencies by design, so you don’t necessarily need to roll off the high frequencies yourself.

At the same time, rolling off the highs (moving the right line to the left) can take away some

of the “tinny-ness” of the reflections, and rolling of the lows (moving the left line to the right)

can take away some of the rumble of the reflections.

We tend to start with the low cutoff at 100 Hz and the high cutoff at 5 kHz. If we hear

“sibilance” (too much “ssss’s” and “shhh’s”) from the singer we move the high cutoff down

below 2 kHz, as high frequency reverb can accentuate sibilance in an undesirable way.

General Reverb Tips

Like any effect, it’s easy to overdo reverb. Hear are some tips for “keeping it real”

• Bypass the mastering reverb from time to time to get a reality check on what the dry

world sounds like. In most cases, reverb should be “sensed” more than it’s heard, if

used at all on a mix.

• If you want “more” reverb, keep in mind that you have multiple options. You can

increase the wet amount (the level of the reverb mixed into your mix), or you can

increase the room size (the length of the reverb) or you can increase the room width.

Adjust each of these then use the History window (or A/B/C/D feature) to decide which

adjustment was the most effective.

• You can reorder where the reverb is applied in the signal chain. By default, it’s before

the multiband modules. Try putting it after the multiband module for a slightly

different effect. Instead of compressing the reverb, you’ll be adding some reverb to

the compressed signal. You might like the sound of a compressed mix, but with some

uncompressed “air” on top of it.

• Compare to commercial mixes for a reality check. What to compare to depends on the

sound you’re shooting for. Something like Steely Dan is pretty dry (and more of an

acoustic room reverb) where something like George Michael or Phil Collins can be very

lush (with more of a studio plate reverb sound). If you’ve got a pop ballad, you’re

probably going to be able to get away with a thicker coat of reverb than on a hip-hop

mix.

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 32 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 33

• If you’re applying a wide reverb (room width up between 2.0 to 3.0) keep an eye on

the phase meters, and use the Channel Ops (especially the mono switch) to check to

make sure it doesn’t completely fall apart in mono.

Bonus Tip: If you wrap old tennis balls in aluminum foil and bake them slightly in the oven,

you can sometimes get some bounce back into them. Just checking to see if you’re still paying

attention.

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 33 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 34

MULTIBAND EFFECTS

A standard compressor or stereo widener can be a useful tool for processing your mix. The

possibilities become even more interesting when you’re working with multiband effects. With

multiband effects, you can apply processing to individual bands or frequency regions of the

mix. This means that you can choose to compress just the dynamics of the bass region of a

mix, or just widen the stereo image of the midrange.

Ozone includes three multiband effects: A multiband dynamics processor, a multiband stereo

imaging control, and a multiband harmonic exciter. To get the most out of these effects, it’s

useful to first take a second to consider the multiband concept and how to setup multiband

cutoffs for your mix.

Multiband effects have been around for many years in hardware. Engineers realized long ago

that they could filter the bass of a mix with an equalizer, route the filtered output of the

equalizer through a compressor, and then mix the output of the compressor back into the mix.

Software plug-ins eliminate a lot of the wiring complexities of using multiband effects, but still

present design challenges of their own. A multiband effect is essentially splitting your mix into

frequency regions, processing them independently, and then combining them back together

again. In order to sound natural, the design must carefully compensate for how the bands are

split apart and recombined. Ozone has been developed to perform multiband processing with

extremely tight phase coherence, which means that you have the power of multiband

processing while retaining a natural transparent sound.

Using Multiband Effects in Ozone

Before diving into the effects themselves, the first step is to listen to your mix and determine

where to set the band crossover points. Load up a mix and switch to one of the multiband

modules (Multiband Harmonic Exciter, for example)

At the top of the screen you can see a spectrum divided into four bands. The vertical lines

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 34 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 35

represent the crossover points of the multiband effects.

You can adjust the band cutoffs by clicking and dragging them with a mouse. You can also use

the arrow keys after selecting a band cutoff, which is indicated by the horizontal arrows

pointing to the band.

Setting Multiband Cutoffs

So where do you set the bands? In general, you want to try to split your mix so that each

region captures a prominent section of your mix. For example, the strategy behind the default

band cutoffs is as follows:

Band 1: This band is set from 20 to 120 Hz, to focus on the “meat” of the bass instruments

and kick drum.

Band 2: Band 2 extends from 120 Hz to 2.00 kHz. This region usually represents the

fundamentals of the vocals and most midrange instruments, and can represent the “warmth”

region of the mix.

Band 3: Band 3 extends from 2.00 kHz to 10 kHz, which usually can contain the cymbals,

upper harmonics of instruments, and the sibilance or “sss” sounds from vocals. This is the

region that people usually hear as “treble”.

Band 4: Band 4 is the absolute upper frequency range, extending from 10 kHz to 20 kHz. This

is usually perceived as “air”.

Keeping in mind that instruments have harmonics that can extend over several octaves, the

goal is to try to partition your mix into bands. Play your mix, and click on the “M” button on

each of the bands. This mutes the output of that band. Now you can hear exactly which

frequencies are contained in each band. Try adjusting the band cutoffs by dragging them with

the mouse. (Note that because of the analog design of the filters it will take a half second for

the cutoff filter to adjust to the new cutoff).

Note that you can choose to use 1, 2, 3 or 4 bands – i.e. you don’t have to split up your

multiband processing into four bands. Less bands can be easier to manage in some cases, and

can also conserve CPU processing. To add or remove bands, right click on the mini-spectrum

as shown below and choose “Insert Band” or “Remove Band”.

Crossover Options

As mentioned before, the first step of multiband processing is to split up (filtering) the signal

into different bands. As such, you have the option of using analog filters or digital (linear

phase) filters for multiband effects.

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 35 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 36

To select the crossover type, right click on the mini-spectrum and select the “Crossover

Options” menu item as shown below.

Once selected, the Crossover Options screen appears. Here you can specify whether to use

analog or digital filter models for the crossovers. Note that if you use digital crossover, you

can also specify the slope or “Q” of the crossovers.

Which should you use? As always, it’s a matter of taste. Analog multibands can provide a

desirable coloration of the sound, while digital crossovers provide linear phase “transparent”

processing.

Multiband Main Points

If you can hear the “parts” of your mix captured in each of the bands you’re in good shape. If

you don’t know exactly where to set them, don’t worry. Once you start applying processing to

each of the bands you’ll begin to develop an intuition for where they should be set. The main

ideas at this point are simply

• Multiband effects are applied independently on up to four separate bands

• Each band should represent a musical region of your mix (bass, warmth/vocals, air,

etc.)

• You can adjust the cutoffs of each of these bands

• You can mute the output of the bands to hear exactly what is passing through the

remaining bands.

So let’s just leave it at that for now and have some fun with a little multiband processing.

Bonus Tip: Right click on any control and you can copy its value to the clipboard. From there,

you can paste the value to another control, or even another text application (Notepad, Excel,

etc.)

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 36 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 37

MULTIBAND HARMONIC EXCITER

Let’s start with a Multiband Harmonic Exciter as our first venture in Ozone multiband

processing. It’s an easy effect to hear, and is very powerful when used as a multiband effect.

Before we get started with the Multiband Harmonic Exciter in Ozone, though, here’s a little

background on the principle of exciters.

An exciter is typically used to add a sparkle or presence to a mix. It’s a sound heard on many

pop recordings, and was probably used to an extreme on pop in the 80s, but is still commonly

heard today. A beginner might try to get the same “sound” as an exciter with high frequency

EQ boost, but with less than similar results.

There are many design strategies used in the exciters commercially available today, from

waveshaping and distortion to short multiband delays. Distortion in small doses isn’t

necessarily a bad thing. If designed correctly and applied with restraint, distortion can create

harmonics that add an excitement or sparkle to the mix.

Ozone provides a selection of exciters modeled on analog tube or tape saturation. When tubes

saturate, they exhibit a type of harmonic distortion that is surprisingly musical. This distortion

creates additional harmonics that add presence or sparkle to the mix while still preserving a

natural analog characteristic. You can see perhaps why boosting high frequency EQ is not

going to achieve the same effect. Boosting an EQ simply turns up the existing harmonics,

where a harmonic exciter actually creates additional harmonics. Tape saturation provides a

similar effect, although the harmonics that are created are more “odd than even”. That is,

tube saturation typically generates even harmonics that are an octave apart (again,

musical….), while tape saturation is a slightly more aggressive excitation that generates odd

harmonics that are a fifth apart.

It’s also very easy to overdo an exciter. What may sound good at 3.0…might sound even a

little better at 4.0…and once you get used to that you find yourself pushing it up to 5.0 to

keep the “excitement”. Before you get caught up in the excitement (pun intended we guess)

and send it off the duplicator, do a little reality check:

1) Compare it to some commercial mixes. OK, in some cases these are overdone as well, but

it depends on the genre and sound you’re shooting for. What works for a dance mix probably

isn’t going to sound as appropriate on an acoustic jazz number.

2) Live with the “excited” mix for a while. At first listen an exciter is, well, exciting, but over

time it can really sound fatiguing or even harsh and annoying.

Using the Multiband Harmonic Exciter in Ozone

This is a very easy effect to use. That could also be why it’s often overused.

Each of the four bands has a pair of controls. In most cases, you’re going to be using the

Amount control. In addition, you’re probably going to be applying excitation to the upper one

or two bands, although there are some cases where tube saturation in small amounts across

the entire spectrum (all four bands) can be musically pleasing.

With your mix playing (of course) adjust the Amt slider in Band 3 upwards. As you move the

slider up you’ll hear what starts as sparkle and excitement, but can quickly turn against you as

you go up too far. Take note of the point where it starts sounding “annoying” and then turn it

back down to 0.0.

Now try moving up the Amt slider for Band 4. Chances are, you’re going to be able to tolerate

Ozone™ Mastering Guide Page 37 of 66 ©2003 iZotope, Inc.

Page 38

more harmonic excitation in the higher band relative to Band 3. Use this to your advantage

when adding excitation: Higher bands can usually bear higher amounts of excitation.

In most cases, the Mix slider can be left at 100. This represents the level of the saturated

signal that’s being mixed back into the original signal (sort of a Dry/Wet mix control for the

tube saturation/excitation). In slightly simplified terms, the Amount control determines the

number of harmonics that are created, while the Mix control determines the level of these

harmonics. Therefore, as you turn up the Amt an appropriate opposite action, depending on