Page 1

HHB CDR-800 Professional Compact

Disc Recorder. HHB Communications

USA, LLC, 1410 Centinela Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90025, (310) 319-1111, FAX

(310) 319-1311, E-Mail sales@hhbusa.

com; Website www.hhbusa.com.

HHB Communications is a British-based

firm specializing in digital audio recording equipment and media for the professional audio industry. In addition to CD

recorders, HHB manufactures portable

DAT recorders, a line of vacuum-tube

processors (including mike preamps,

compressors, and parametric equalizers),

and studio monitor loudspeakers (including nearfield monitors and powered subwoofers). HHB also distributes the Genex

line of high bit rate, high sampling rate

magneto-optical digital recorders. Their

complete line of digital media includes

professional-quality recordable compact

discs (CD–R), ADAT tapes, MiniDiscs

(MD), and rewriteable magneto-optical

(MO) discs.

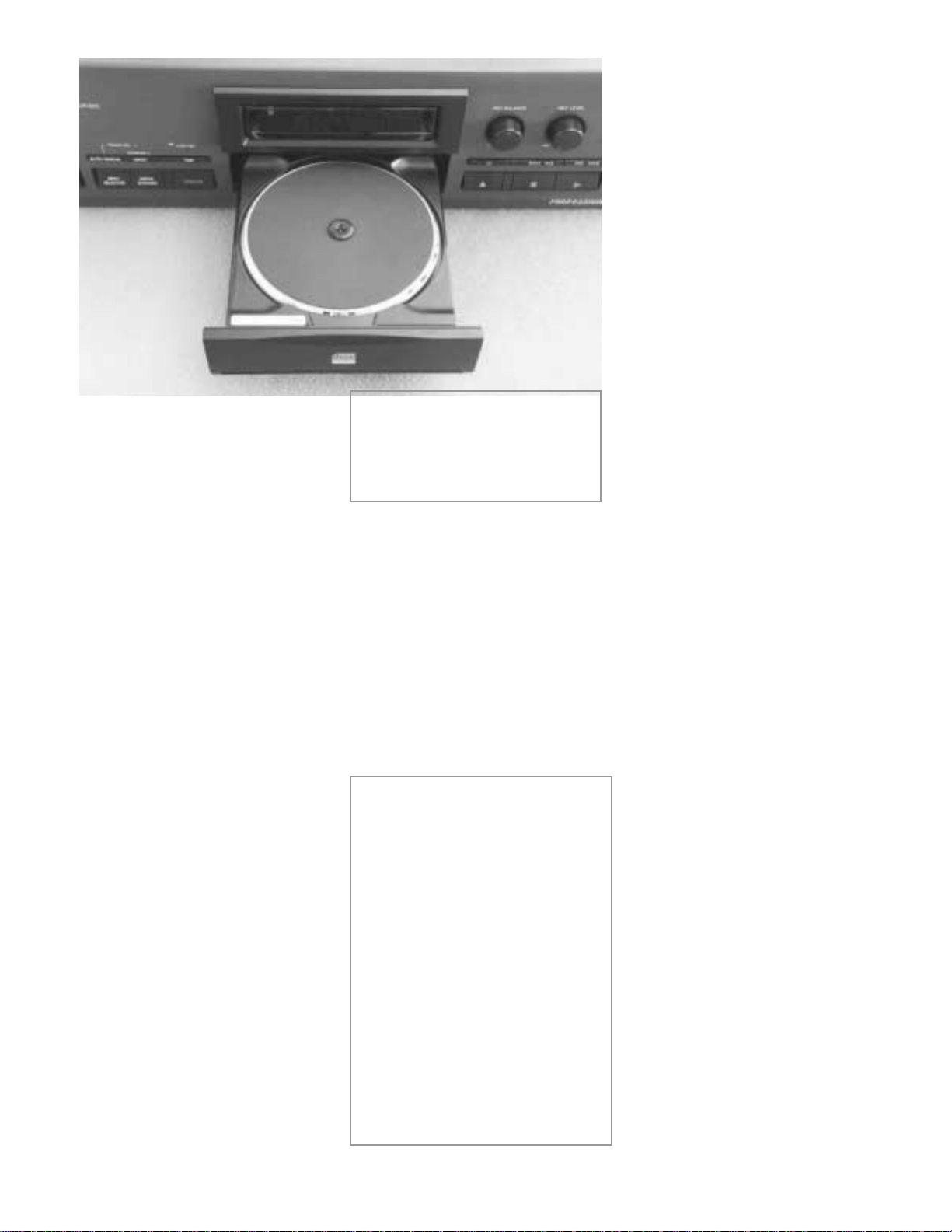

The CDR–800 Compact Disc

recorder (Photo 1) has been on the

market for over two years. At the time it

was introduced, the CDR–800 represented a price breakthrough in professional CD recorders. The list price of

$2200 has become irrelevant, since the

unit now sells for around $1200 at most

pro audio dealers.

The CDR–800 looks suspiciously like

the Pioneer PDR–05 and PDR–99 consumer CD recorders, which are essentially identical—the PDR–99 is marketed as

part of Pioneer’s Elite line, and features

their glossy Urushi front panel and Rosewood side panels. While based on the

consumer models, the CDR–800 is actually manufactured by Pioneer for the proaudio user, and incorporates a number of

features not found on the consumer

units. The Pioneer consumer players

have only unbalanced (RCA) analog inputs and outputs, along with S/PDIF and

Toslink digital inputs and outputs. To

these interfaces, the CDR–800 adds balanced XLR analog inputs, along with a

balanced XLR AES/EBU digital input

(Photo 2).

All analog and digital outputs on the

CDR–800 remain unbalanced. This may

appear odd at first, but most pro audio

users are likely to use the CDR–800 with

an external digital processor for play-

back, making balanced analog outputs

unnecessary. One other important difference between the CDR–800 and its Pioneer counterparts concerns the types of

recordable CDs you can use. The Pioneer

consumer machines will only recognize

consumer-type CD–R blanks. The

CDR–800 will also work with computertype CD blanks. The CDR–800 is also

equipped with standard 19-inch rack

mounts.

One important feature of the

CDR–800 is Pioneer’s Stable-Platter

mechanism (Photo 3), which includes a

full-size platter upon which the CD is

placed upside down. There are a couple

of advantages to this system. First, the

disc is supported over its entire surface,

minimizing vibration, which, in turn,

should reduce clock jitter. This serves

the same purpose as the disc dampers

many of us have used, but Pioneer’s solution is far more effective. Second, the

laser now faces down, so it is far less likely to accumulate dust.

Operation

Operationally, the HHB CDR–800 is extremely well thought out, and is really

not much more difficult to operate than

an analog cassette deck. For the most

32

Audio Electronics 2/00

P

RODUCT

R

EVIEW

HHB Compact Disc Recorder

Reviewed by Gary Galo

PHOTO 1: Front view of the HHB CDR–800 Professional Compact Disc Recorder and its remote control.

PHOTO 2: Rear panel of the CDR–800.

In addition to the RCA-type analog and

digital inputs, balanced XLR analog inputs and an AES/EBU balanced digital

input are also provided.

Page 2

part, the manual is clearly written, and

includes numerous illustrations. Input

and output connections are straightforward, but the rear panel also contains a

couple of switches that you may need to

reset. A three-position slide switch located between the balanced analog input

connectors selects either the unbalanced

RCA line inputs or the balanced XLR

connectors at +4dBu or −8dBu levels.

A digital out switch mutes the digital

outputs if only the analog outputs are

used. You select digital copy permission/prohibition with a pair of DIP

switches, which you can set to allow unlimited copies of your recording, onetime-only copying, or no copying at all.

Since the CDR–800 is a professional

product, it is not bound by the consumer

Serial Copy Management System—the

user controls the copy management.

Input selection is done with a momentary contact button on the front panel—

you toggle through the various analog

and digital inputs by repeatedly depressing the button. The CDR–800 has five

modes of operation—three are automatic

and two are manual. One of the most useful of the automatic modes is ID–SYNC

for recording from DAT sources. This

mode copies index numbers from your

DAT and automatically turns them into

track numbers on your CD–R.

The AES/EBU interface does not transmit DAT ID codes, so you must use the

S/PDIF connection. To do so, simply load

a blank disc and toggle the INPUT SELECTOR until the correct input appears—the

display should recognize DAT as the

source at this point. Now, cue up your

DAT tape to a point about five seconds

ahead of the first DAT index number you

wish to record. Next, toggle the DIGITAL

SYNCHRO button until ID–SYNC appears in the display. The CDR–800 will

begin a short setup procedure, which

takes a few seconds.

After this setup, ID–SYNC returns to

the display, and SYNC flashes in red. You

are now ready to begin recording. Simply press the play button on your DAT

recorder—when the next index number

appears, the CDR–800 automatically begins recording, making that index number track 1 on the CD. You don’t even

need to press RECORD on the CDR–800.

Each subsequent DAT index number au-

Audio Electronics 2/00

33

PHOTO 3: A close-up view of the Pioneer

Stable-Platter mechanism used in the

CDR–800. The CD must be inserted upside down, but this mechanism greatly

reduces disc vibration and dust accumulation on the laser pickup.

T ABLE 1: MANUFACTURER’S SPECIFICATIONS

Applicable discs: CD and CD-R

Frequency response: 2Hz–20kHz

Playback S/N: 110dB (EIAJ)

Playback dynamic range: 97dB (EIAJ)

Playback THD: 0.0027% (EIAJ)

Recording S/N (analog RCA input): 90dB

Recording dynamic range (analog RCA input): 90dB

Recording THD (analog RCA input): 0.005%

Recording S/N (S/PDIF digital input): 105dB

Recording dynamic range (S/PDIF digital input): 95dB

Recording THD (S/PDIF digital input): 0.003%

Wow and flutter: Less than measurable limit (

±

0.001%

weighted peak) (EIAJ)

Analog input impedance: 10k

Analog XLR line input level: +4 or +8dBu, switchable

Analog RCA line input level: 500mV RMS

Analog output voltage: 2V RMS

Power supply: US model: 120V AC, 60Hz; European

model: 220-230V AC, 50/60Hz

Power consumption: 21W

Weight: 6.2kg (13 lbs. 11 oz)

Dimensions: 482mm (W) ×294mm (D) ×134mm (H)

(18

³¹₃₂″×

11

⁹₁₆″×5 ⁹₃₂″

)

Page 3

tomatically generates a track number on

the CD. It makes sense to prepare a DAT

master, including all of the index points

you desire, before making a CD–R.

The CDR–800 will also copy other

digital sources the same way, including

MiniDisc, Digital Compact Cassette, and

CD, using the AL–SYNC mode. There is

also a 1–SYNC mode that allows automatic copying of 1 track from any of the

above digital sources. After the one

track of the original has been recorded,

the recording process stops. You can

add additional tracks to your recording,

using this mode, until the CD–R is filled

to capacity.

The CDR–800 also allows manual

copying of analog or digital sources, one

track at a time. During manual recording, the CDR–800’s REC LEVEL and REC

BALANCE function the same as on any

other recording device. You can record

an individual track, stop, and continue at

a later time. If you manually record a single track, a process called “fixation” automatically takes place before and after

the track is recording. During fixation,

the lead-in and lead-out information for

that track is written.

When you have finished recording a

CD, you must perform a process called

“finalization,” which allows the CD–R to

be played on any conventional CD player. During this process, the absolute leadin and lead-out information for the entire

disc, and the table of contents, are written to the CD, along with a code that prevents further recording on the disc.

Once you have finished recording a disc,

press the FINALIZE button. After a few

seconds of setup, the display will indicate a time of 4:03 or 4:07, depending

on the length of the recording. This is

the amount of time it will take to finalize

the disc.

Now, press the PAUSE button to begin

the process. The time display begins

counting down—when it reaches 0:00,

the process is complete, and the CD–R

may be played in any CD player. The

CDR–800 has a SKIP–ID function that

can be used during finalization. This

function allows you to effectively eliminate any unwanted tracks on your CD

after it has been recorded. Suitably

equipped CD players will then ignore

those tracks during playback.

The CDR–800 is supplied with a remote control that duplicates the functions of the front-panel controls. You

must use the remote to enter track numbers for CD playback—numeric buttons

for track selection are not included on

the main chassis of the CDR–800. Remote-control operation can be defeated

with a DIP switch on the rear panel. The

rear panel of the CDR–800 is also fitted

with an 8-pin DIN Parallel Remote socket, which allows you to construct your

own wired remote control, duplicating

PLAY, PAUSE, RECORD, STOP, MA NUAL

TRACK NO., WRITE, and the two

TRACK SEARCH BUTTONS. A connection diagram is included in the CDR–800

manual.

Circuitry and Construction

As Photo 4 shows, the CDR–800 is

packed with circuitry. There are no less

than 13 PC boards in the CDR–800, varying in size from large servo and audio

digital boards to several very small

boards, including the headphone amp.

Two power transformers are used, one

for the audio and digital circuitry, and another dedicated to the servo. Like most

products of Far East origin, the CDR–800

uses standard 3-terminal IC regulators for

the power supplies. Several of these regulators are located on the two powersupply PC boards, but the analog/digital

board and the servo board each house a

pair of local IC regulators.

34

Audio Electronics 2/00

Page 4

Audio Electronics 2/00

35

The physical structure of a CD–R disc is

shown in Fig. 1. The recordable CD is

molded with a continuous groove spiral

from the inside to the outside of the disc’s

polycarbonate substrate. The “pregrooved” disc is necessary in order to

provide the recorder with a physical reference. The groove also contains timing

information that the recorder uses to

keep the CD spinning at the correct

speed at all points along the disc surface.

After the polycarbonate substrate is molded, the disc is spin-coated with the

recording layer, an organic dye such as

cyanine, phthalocyanine, or azo.

The recording layer is then coated with

a vacuum-deposited reflective layer, followed by a spin coat of protective lacquer. Most CD–R manufacturers add a

label coating to further protect the disc

from scratches. Special discs are available

with a label area compatible with an inkjet printer specifically made for printing

CD–R discs.

Inexpensive CD labeling systems are

also available, from a variety of sources.

Most of these allow you to print or write

on a circular label with adhesive backing.

These labeling systems carefully center

the label on the CD in order to ensure

smooth disc rotation. The adhesive backing on the CD labels is compatible with

the materials from which the disc is manufactured, and should not impair the performance of the disc, or shorten its life. If

you label CDs by hand, you should avoid

solvent-based inks that could damage the

disc. TDK makes a pen specifically for labeling CDs, which you can purchase

from any pro audio dealer.

The recording laser beam is the same

wavelength as that used for CD playback—780nm. The laser in the CD

recorder literally burns the organic

recording layer, momentarily raising the

temperature of the recording layer at

that spot to over 300°F. The width of a

burned area, the equivalent of a pit on a

prerecorded CD, is only 0.6 microns.

The burning alters the optical characteristics of the organic dye, producing a different level of reflection from burned vs

non-burned areas.

The most common organic dye found

in CD–R disc is cyanine. Azo dye, originally developed for types of optical

recording media, is also used for CD–R

discs. Cyanine and azo-based discs are

sensitive to ultraviolet light, as well as

heat and humidity. As such, their archival

life expectancy is only about ten years.

The recording surface of most CD–R

discs is green, while some appear blue.

This is due to the type of dye used and

the color of the reflective layer. Silver and

gold reflective layers yield a different

color when they reflect light back

through the organic dye.

More recently, the Japanese firm Mitsui

has developed a CD–R disc using phthalocyanine dye. These discs are gold in color,

in part due to the gold reflective layer.

The phthalocyanine discs are far less susceptible to the degrading effects of light,

heat, and humidity, and are expected to

have an archival life in excess of 100

years. Mitsui is manufacturing these gold

discs for a number of other firms, including HHB, and they have licensed the technology to other manufacturers as well.

Care should be exercised in the handling and storage of all CD–R discs. Tests

have shown that the green cyanine-based

discs can be rendered unplayable if left

exposed to bright sunlight for only a few

days. Unless they are being recorded or

played, all CD–R discs should be stored in

their jewel cases at all times. The HHB

CDR–800 recorder automatically adjusts

the intensity of the laser beam to suit the

specific type of dye found on the CD–R

that has been inserted in the recorder.

All CD–R discs from reputable manufacturers are certified to meet “Orange

Book” specifications. The Orange Book is

a document produced by Sony and

Philips describing the technical specifications for the compact disc format. Part II

of the Orange Book describes the CD–R

format. You can find a considerable

amount of information on the CD–R

format on the websites of Maxell

(www.maxell.com) and HHB (ww w.

hhbusa.com or ww w.hhb.co.uk).

CD–R Basics

FIGURE 1: Cut-away view

of a CD–R recordable CD.

The pregrooved polycarbonate substrate is coated with an organic dye

recording layer and a reflective layer. During

recording, the laser beam

burns the organic dye,

momentarily raising the

temperature of the dye

to over 300°°F.

A-1522-1

Page 5

Balanced analog and AES/EBU digital

signals enter the CDR–800 via the input

PC board assembly. The balanced analog

inputs are transformerless; the + and −

legs of the balanced line are each fed to

5532 op amps operated noninverting as

unity gain buffers. The outputs of these

buffers are fed to the + and − inputs of a

single 5532, converting the balanced signal to an unbalanced state.

The use of 5532 op amps is a real disappointment. I fail to understand why

the Japanese audio industry continues to

use these 20-plus-year-old devices when

so many high-performance dual op amps

are now available. A product as sophisticated as the CDR–800 clearly deserves

better, but the Pioneer designers obviously continue to believe that high-performance op amps just don’t make any

difference.

The AES/EBU digital input also dispenses with the usual transformer-coupled input—the balanced to unbalanced

conversion is accomplished with an

SN75157P differential line receiver. The

SN75157P is a dual device; only half of it

is used.

The signals from the balanced input

PC board are fed to the audio digital PC

board assembly, which also houses all of

the analog and digital unbalanced inputs. The unbalanced analog inputs for

each channel are fed to NJM072 input

signal op amps, manufactured by JRC.

These are TL072-equivalents, another extremely dated device (data on JRC op

amps can be found on their web site:

www.njr.co.jp).

I’m not familiar with the analog-to-digital converter chip—it bears the part

number AK5340–VS. HHB claims it uses

the latest 1-bit conversion system, which

is completely free of zero-crossing distortion. The A/D chip design also eliminates nonlinear distortions within the

passband, and does not require external

adjustments.

Digital inputs are fed directly to the

LC89585 EFM encoder chip. The

CDR–800 also includes a built-in sampling-rate converter chip, which converts 32kHz or 48kHz inputs to the CD

standard of 44.1kHz. The sampling-rate

converter functions only when needed—

inputs at the standard 44.1kHz frequency

bypass the sampling-rate converter.

On the playback end, the SM5813AP

digital filter feeds a pair of 1-bit Pioneer

36

Audio Electronics 2/00

PHOTO 4: Inside view of the CDR–800. Two

power transformers are used, and the solid

copper chassis provides excellent shielding

against EMI and RFI.

Page 6

PD2028B Pulseflow D/A converter

chips, which are actually stereo devices,

with left and right audio outputs. To improve low-level linearity, an entire chip is

devoted to each channel, configured in a

differential mode. The balanced outputs

from the D/A chips are fed to the ±inputs

of a 5532 op amp. The unbalanced output from the op amp is fed to a second

5532, which functions as an output

buffer. The filter/DAC combination

should provide resolution comparable to

conventional 20-bit converters.

Deemphasis is accomplished in the

analog domain, using a shunt filter located between the first and second 5532.

The deemphasis network is activated

with a single bipolar transistor. The

CDR–800 does not apply emphasis to CD

recordings. Only a handful of commercial CDs, mainly from Denon, are recorded with high-frequency emphasis, and

modern high-resolution converters make

it unnecessary. Overall, the construction

of the CDR–800 is extremely impressive.

This unit should stand up to demanding,

day-in, day-out professional use.

Performance

In order to evaluate the accuracy of

CD–R recordings, I made a demonstration disc cloned from a number of tracks

on commercial CDs that I normally use

for equipment evaluation. I made the

test disc by connecting my CD transport, a modified Denon DCD–1015, to

the S/PDIF input on the CDR–800. My

DCD–1015 has a Canare 75Ω BNC out-

put connector—the two units were connected with a DH Labs D–75 S/PDIF in-

terconnect fitted with a Canare 75Ω

BNC connector on one end, and a

Canare 75Ω RCA connector on the

other.

Every self-respecting, golden-eared audiophile will desire to know exactly

how the CDR–800’s copies compared to

the original CDs. Unfortunately, the answer is not at all straightforward. I can’t

honestly state that the copies were indistinguishable from the originals. However, any differences I heard are no greater

than those caused by substituting one

high-quality digital interconnect for another. The differences were normally far

less than those I associate with changing

CD transports.

In my opinion, digital copies made on

the CDR–800 are faithful reproductions

of the original, and any observed differences may well be attributed to external

factors. The performance of the

CDR–800 will depend primarily on the

quality of your source and the intercon-

nect between your source and the HHB

recorder.

The dated op amps mentioned previously undoubtedly limit the performance of the CDR–800 when used with

its analog inputs and outputs. However,

the excellent performance of the A/D

and D/A converters used in this recorder

make up, in part, for the performance

of the op amps. I have no doubt that replacement of the op amps with the best

dual devices currently available would

significantly improve the analog performance of the CDR–800, allowing the excellent digital circuitry to perform to its

potential.

Conclusions

The HHB CDR–800 is a remarkable product, and a real breakthrough in affordable

professional CD recorders. Used with external digital sources, via its digital input,

the CDR–800 will make compact discs

that are virtual sonic clones of the original digital source. Recently, HHB introduced the CDR–850 rewritable Compact

Disc Recorder (CD–RW), which is priced

about $200 less than the CDR–800. Readers may wonder whether it renders the

800 obsolete. Not at all! The new

CDR–850, also based on a consumer Pioneer product (the PD–R555RW), does

not have the Stable Platter mechanism.

For the ultimate in CD–R mechanical stability, the CDR–800 will continue to be

the recorder of choice.

Home users in need of a CD recorder

should not hesitate to purchase this pro

product. Because of the Stable Platter

mechanism, the CDR–800 will probably

outperform your existing CD transport,

so you may be able to dispense with your

existing playback machine.

When the time came to purchase a

CD recorder for use in my studio at the

Crane School of Music at SUNY Potsdam, where I am employed as audio engineer, I chose the CDR–800. I could not

give a more enthusiastic endorsement. ■

Audio Electronics 2/00

37

Loading...

Loading...