Page 1

Engineered Humidification Systems

Load Calculation Guide

H e r r m i d i f i e r® | w w w . h e r r m i d i f i e r- h v a c . c o m

Page 2

L o a d C a l c u l a t i o n G u i d e

TABLE OF CONTENTS

SECTION I PREFACE

Preface ...........................................................................................................................................................3

SECTION II BASIC INFORMATION

Denition Of “Relative Humidity” ....................................................................................................................4

“Dry Air” From Heating ....................................................................................................................................4

“Dry Air” From Cooling .................................................................................................................................... 4

The Psychrometric Chart ................................................................................................................................5

Equilibrium Moisture Content .........................................................................................................................5

“Regain” Of Hygroscopic Materials.................................................................................................................5

“Dry Air” And Comfort .....................................................................................................................................5

Humidity And Dust ..........................................................................................................................................6

Humidity And Its Effect On Bacteria And Virus Life ........................................................................................ 6

“Dry Air” And Static Electricity ......................................................................................................................... 6

“Dry Air” And Hygroscopic Materials ............................................................................................................... 7

Woodworking And Humidication ................................................................................................................... 8

Paper Products And Humidication ................................................................................................................8

Printing And Humidication.............................................................................................................................9

Textiles And Humidication .............................................................................................................................9

Food Storage, Processing And Humidication ............................................................................................... 9

Leather Processing And Humidication .......................................................................................................... 10

A Humidication Synopsis .............................................................................................................................. 10

SECTION III LOAD CALCULATIONS

The Psychrometric Chart ................................................................................................................................11

Heating Load ..................................................................................................................................................12

Cooling Load ..................................................................................................................................................14

Product Load ..................................................................................................................................................15

Process Reduction .........................................................................................................................................16

People Reduction ...........................................................................................................................................16

SECTION IV TYPES OF EQUIPMENT

Atomization .....................................................................................................................................................17

Evaporation ....................................................................................................................................................19

Steam .............................................................................................................................................................19

2 w w w. h e r r mi di f i e r- h v a c . co m

L o a d C al c u l a t io n G u i de

Page 3

Preface

L o a d C a l c u l a t i o n G u i d e

HERRMIDIFIER welcomes you to the world of engineered

humidication systems. HERRMIDIFIER was founded in

1945 and humidication is our only business. We are your

“Total Capability Humidication Resource.”

This Guide will familiarize you with both the need and the

benets of controlled humidication. It will also acquaint you

with the technical facets of accurately calculating humidication demand loads and the selection of the best and most

appropriate system for your application.

HERRMIDIFIER’s recognized leadership position within the

industry is borne from many reasons.

They include:

•Committed to Quality

•Broadest Range of Humidication Systems

-Electrode Steam Generators

-Electric Resistive Steam Generators

-Central Steam

-Steam to Steam

-Air/Water Atomizing Systems

-High Pressure Water Atomizing Systems

-In-Duct Systems

-In-Space Systems

-Water Pretreatment Systems

•Factory Trained Sales Force

-A nationwide network of factory-trained technical sales

representatives.

•Technical Support

-Or Engineering staff will custom design a system to ll

your specic needs.

•Technical Leadership

-State-of-the-art, engineered and patented energy efcient system development.

•Market Diversication Telecommunications

-Computer Rooms

-Electronic Manufacturing

-Textile

-Woodworking

-Printing

-Paper Storage

-Food Storage

-Hospitals

-Ofce Buildings

•Service

We trust this Guide answers your questions. We have more

engineering data for your use and we are ready to help you

solve your dry air problems. Give us a call!

L o a d C al c u l a t io n G u i de

w w w. h e r r mi di f i e r- h v a c . co m

3

Page 4

L o a d C a l c u l a t i o n G u i d e

CU. FT.

7.80 Grains

CU. FT.

.78 Grains

SECTION II BASIC INFORMATION

Relative Humidity and Its Place in Environmental Control

“Dry Air” From Heating

Since the beginning of modern day engineering, environmental control in factories, ofces and homes has become

increasingly more important as its benets to personnel and

product alike were realized. There are three basic parts to

environmental control:

1) air quality-its cleanliness and purity,

2) temperature

3) relative humidity

Of the three, the most ignored is the level of relative humidity-probably because the effects of temperature and air quality are more easily seen and felt than the effects of relative

humidity. Relative humidity is important as it can affect human health and comfort, operation of production machinery,

quality and workability of production material. Proper control

of relative humidity can also be an important factor in the

total energy use and operating efciency of a factory. To develop an understanding of relative humidity and its effect, it

is rst necessary to dene some terms.

Denition Of “Relative Humidity”

HUMIDITY is dened as “the amount of moisture in the air.”

This moisture must be in the form of water vapor. Visible water droplets that have not evaporated to the vapor state do

not affect humidity. The term RELATIVE HUMIDITY is used

to describe “the amount of moisture in a given volume of

air as compared with the greatest amount of moisture that

that volume of air could contain at the same temperature,

expressed as a percentage,” so that:

%RH = (Ma/Mg)

Ma = Amount of moisture in the air

Mg = Maximum amount of moisture in the air

If that cubic foot of air is saturated at 1O°F (100% R.H.) and

raised to 69°F, without adding or subtracting any moisture,

it will now contain only 1/10 the amount of moisture it could

hold at saturation; thus it now has a relative humidity of

10%...2-1/2 times drier than the Sahara Desert!

This is essentially why, during the heating season, air is drier.

The cold, moist outdoor air, brought in by forced air makeup,

exhaust, or natural inltration is heated and becomes warm

dry air. To bring this air to an acceptable level of relative humidity, moisture must be added.

“Dry Air” From Cooling

Under certain conditions, cooling by air conditioning and

refrigeration can remove moisture from the air and reduce

its relative humidity to unsatisfactory low levels. This occurs

when the air is cooled below its DEW POINT-the temperature at which the air becomes saturated and if cooled further

the excess moisture will condense out of the air. For example: Air at 70°F and 75% R.H. will have about 6.08 grains of

moisture per cubic foot.

Air at 55°F can hold only 4.89 grains of moisture per cubic foot at saturation. Therefore, if the 70°F 75% R.H. air is

cooled to 55°F it will now be at 100% R.H. and will contain

a maximum of 4.89 grains of moisture per cubic foot having

lost the excess of 1.19 grains (6.08-4.89 = 1.19) by condensation. When this 55°F 100% R.H. air is discharged back into

the room and again warms to 70°F it will now have a relative

humidity of 60% since it now contains only 4.89 grains of

moisture per cubic foot instead of the original 6.08 grains.

1.19 grains of moisture per cubic foot must now be added to

return the air to its original level of 75% R.H.

The greatest amount of moisture that a given volume of air

can contain changes as the temperature of that air changes. The higher the temperature of that air, the greater the

amount of moisture it can hold when saturated. The key word

here is “temperature.” For example: a cubic foot of air at 69°F

can hold ten (10) times as much moisture as the same cubic

foot of air at 1O°F.

FIGURE 1

4 w w w. h e r r mi di f i e r- h v a c . co m

69°F

10°F

L o a d C al c u l a t io n G u i de

Page 5

The Psychrometric Chart

L o a d C a l c u l a t i o n G u i d e

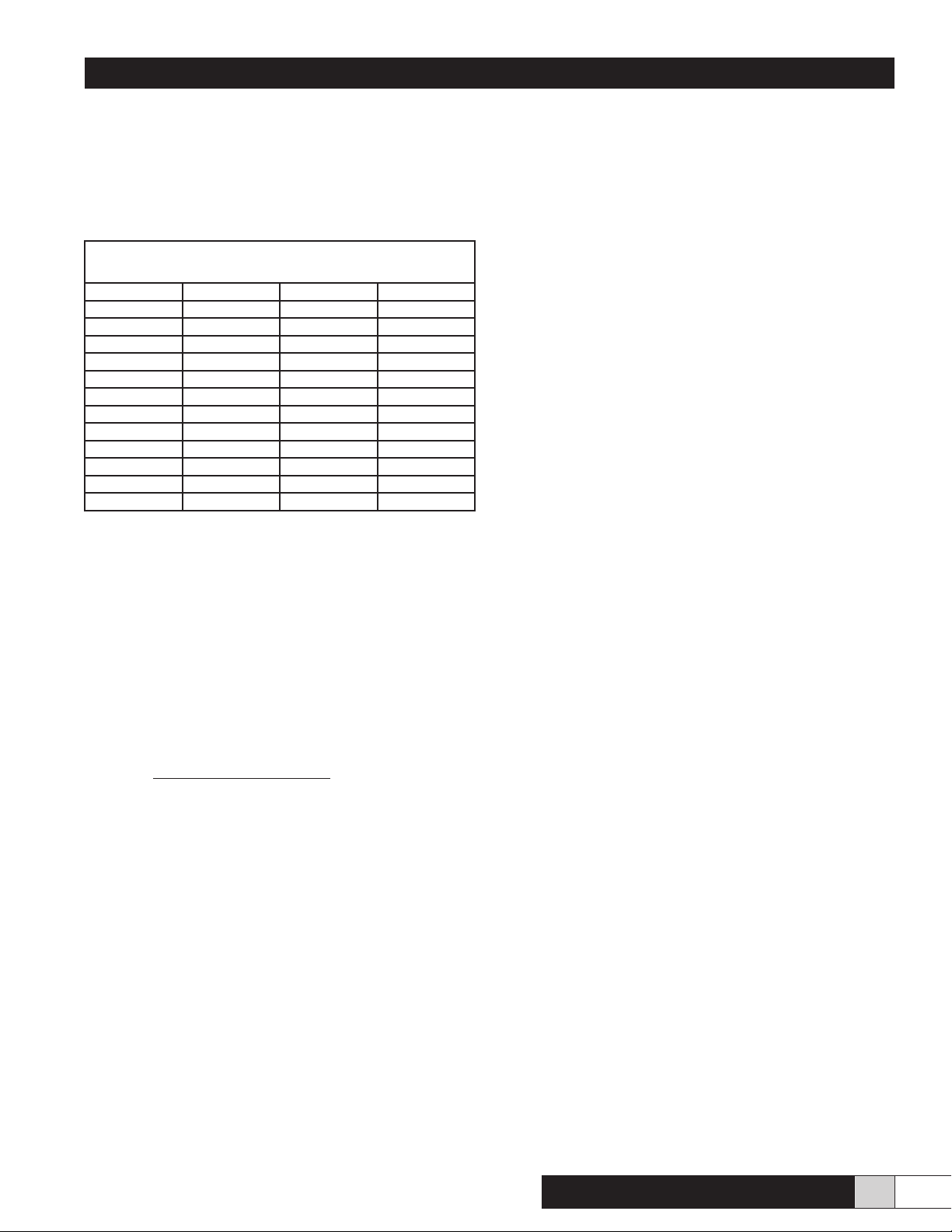

To further illustrate the moisture holding ability of air at various temperatures, following is a chart showing the grains of

water per cubic foot of saturated air, at various temperatures.

This chart was abstracted from the ASHRAE Handbook.

Table 1-A

GRAINS OF WATER PER CUBIC FOOT (AIR)

Saturated Air, Various Temperatures

°F Grains °F Grains

0 .475 60 5.795

5 .609 65 6.845

10 .776 70 8.055

15 .984 75 9.448

20 1.242 80 11.04

25 1.558 85 12.87

30 1.946 90 14.94

35 2.376 95 17.28

40 2.863 100 19.95

45 3.436 105 22.95

50 4.106 110 26.34

55 4.889 115 30.13

As you can see, from the above Table 1 -A, as the temperature of the air increases, so does its ability to hold moisture.

Determinations of MAXIMUM HUMIDIFICATION DEMAND

LOAD are made from this chart. To determine a heating humidication load, simply take the maximum indoor and minimum outdoor temperatures, refer to the chart above, and

write down the corresponding grains of moisture. Then multiply these times the percent of relative humidity desired. Use

the lowest design R. H. for the outdoor gure. Now subtract

the lower temperature gure from higher temperature gure

and insert the result into the following formula for Grains/

Cu. Ft., also inserting the cubic foot of air to be humidied

per hour:

LOAD = Grains/Cu. Ft. X Cu. Ft./Hr.

(Lbs. Water/Hr.) 7000/Grains/lb.

Other factors inuencing the maximum humidication demand load are:

• Natural Air Inltration

• Exhaust Equipment

• Make-up Air

• Construction of Building

• Air Conditioning or Refrigeration

• Vacuum Equipment

• Vapor Barriers

• Window Area

• Hygroscopic Material

Because of all the factors involved, humidication can be

simple or rather complicated. It is best to consult a humidication expert such as Herrmidier Co., Inc. and allow them to

conduct a humidication survey. (Free help can be obtained

by lling out Herrmidier’s form DI-5 and mailing it to us. This

form contains all necessary information for us to help you

design a project).

Equilibrium Moisture Content

Dry air pulls moisture from everything it contacts- HYGROSCOPIC materials (able to absorb or emit moisture), living tissues, etc. Conversely, moist air gives up moisture to

dry hygroscopic materials. An equilibrium will eventually be

reached when the moisture gain of a material equal its moisture loss. This is the EQUILIBRIUM MOISTURE CONTENT

OR “EMC.” This “EMC” changes with temperature, R.H. and

from material to material. The reaching of this “EMC” can

sometimes be detrimental as we shall see.

“Regain” Of Hygroscopic Materials

All hygroscopic materials-and a long list is so classied-take

on or give off moisture when the EMC is disturbed. At a given

level of R.H. a given hygroscopic material will hold a certain

amount of moisture. The weight of this moisture so help compared with the dry weight of the material is called “Regain”

and is expressed as a percentage. Regain varies with R.H.

for a given material. For example: EMC values for average

wood are 5.9% Regain with 30% R.H. air; 9.3% Regain with

50% R.H. air; 14% Regain with 70% R,.H. air; etc. A standard Regain is often specied for hygroscopic items sold by

weight. If the standard Regain is not attained, economic loss

to the seller results.

Variations in Regain cause hygroscopic materials to change

in dimensions, weight, quality, workability, etc.; therefore, it

is best to stabilize the Regain at the most desirable level for

manufacturing, processing, testing, storage, use, consumption, etc. To do this, the R.H. of the air in contact with the material must be stabilized at the proper level, as we shall see.

“Dry Air” And Comfort

Dry air pulls moisture from anything it contacts, including

the human body. Dry air will cause moisture to evaporate

more readily from the surface of the skin, causing a feeling

of chilliness-even at temperatures as high as 75°F! Dry air

also pulls moisture from living membranes, such as the nasal

passages, throat, eyes and ears, leading to the uncomfortable parched throat and sore eyes of winter. Proper control

of relative humidity can help to eliminate these problems.

L o a d C al c u l a t io n G u i de

w w w. h e r r mi di f i e r- h v a c . co m

5

Page 6

L o a d C a l c u l a t i o n G u i d e

When moisture evaporates from the surface of the skin it

causes a degree of evaporative cooling. During the winter,

when heated air is dry, this evaporation occurs more readily,

causing a higher degree of evaporative cooling and a feeling of chilliness. Raising the temperature will help alleviate

the feeling of chilliness, but will actually aggravate the other

problems of dry, parched throat and eyes, because the air

at this higher temperature can now hold still more moisture

(refer to Table 1 -A), which causes the R. H. to drop and the

pull for moisture from body to air becomes even greater.

More comfort can readily be obtained by raising the level of

relative humidity. Often, by raising the R.H. the temperature

can then be lowered while maintaining the same comfort

level. The following Table 1 -B illustrates various comfort

levels possible. As you can see from the chart, raising

the R.H. could result in your being able to lower the temperature, thereby saving energy. In this age of expensive

energy, this could be a big boost for any industry, ofce or

home. In addition the annoying parched throat, sore eyes

and dry nose may be eliminated. Generally, R.H. levels of

35% to 50% are considered to be in the comfort range.

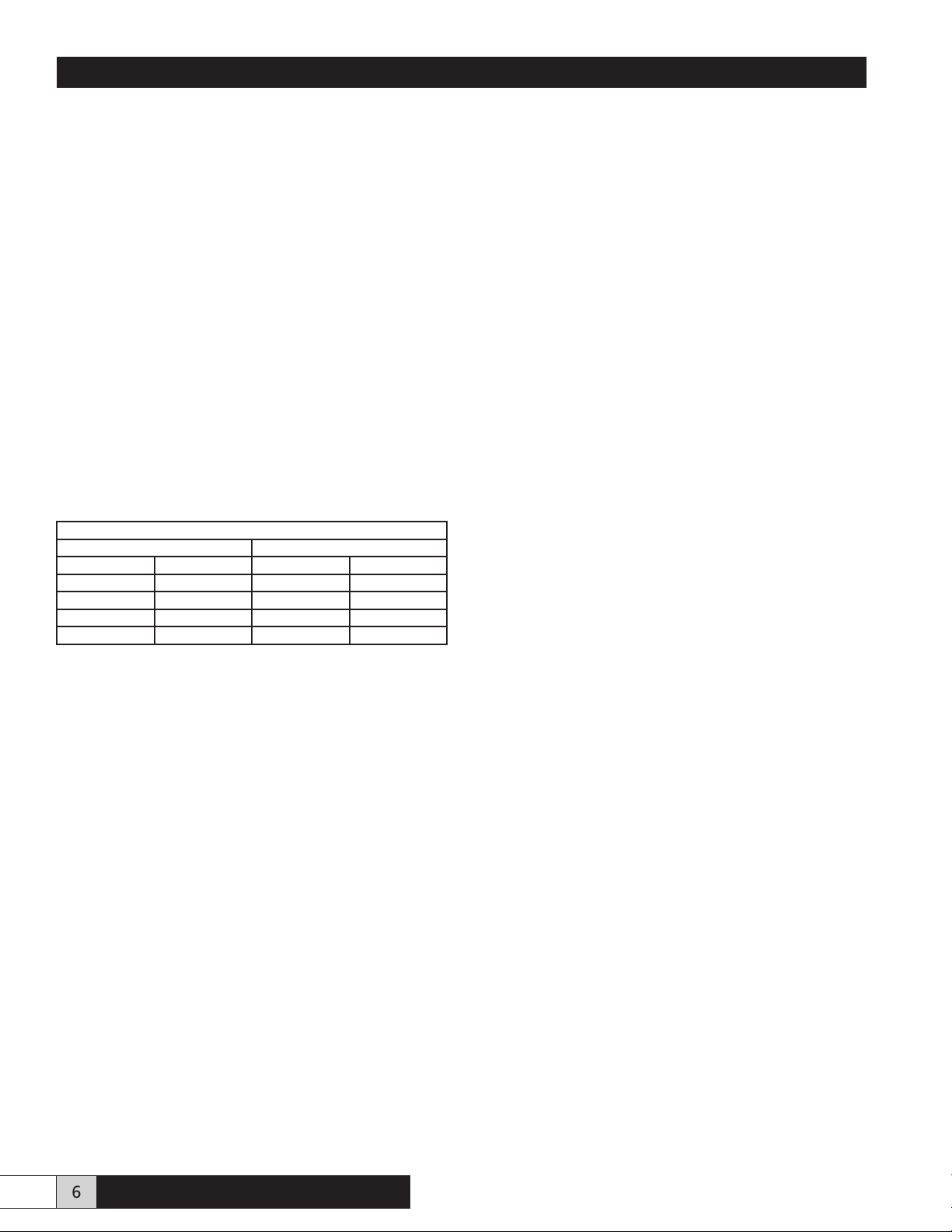

Table 1-B

Comfort Levels vs. Temperature/Humidity

Factory Ofce

°F % RH °F % RH

65 40 68 45

68 30 70 40

72 20 76 25

78 10 79 20

Humidity And Dust

Dust is not only a cleaning and maintenance nuisance but

a common vehicle for microorganisms. It is well known

that the R.H. of the air will signicantly affect the amount of

dust in the air. A higher level of R.H. (50%) will cause the

particles to settle out of the air.

Also, dry air will pull moisture from the bers of carpets and

rugs causing them to become brittle, break off and oat in

the air. By raising the level of R.H. in the air this problem

can be signicantly reduced. For example, in one study a

carpet cleaned weekly, under low levels of relative humidity, produced 3 to 4 bags of broken bers or “fuzz.” After the

R.H. in the ofce was raised to 50% the weekly cleaning

produced only a half bag of “fuzz.” Needless to say, the

carpet life was probably extended, as well as a reduction of

dust from the bers of the carpet achieved.

Humidity And Its Effect On Bacteria And Virus Life

Several studies on various bacterial strains and viruses

have shown that at R.H. levels close to 50% these microorganisms fail to survive for long periods of time. Possible

explanations of this are that at low levels of R.H. these microorganisms can enter a “dormant” state and simply oat

around in the air until such time as they contact a moist

surface where they can become “active” again. At high levels of R.H. there is enough moisture in the air that these microorganisms may be able to thrive “actively.” In the middle

levels of R.H., near 50%, there is enough moisture in the

air that these microorganisms cannot remain “dormant,” but

not enough that they can thrive “actively” either.

“Dry Air” And Static Electricity

Dry air permits the buildup of static electricity charges

on machinery, materials and people. These electrostatic

charges may cause production problems because of the

electrostatic attraction built up between materials, unpleasant shocks to personnel, and in some cases, explosion

hazards.

Static electricity charges are built up by movement of

machinery and materials, such as in a printing press or

a spinning machine, by people walking across carpeted

oors, etc. These charges are constantly being generated

and their buildup and discharge are affected by the level

of R.H. Relative humidity levels above 45% will serve to

eliminate electrostatic charge buildup and discharge. What

happens when R.H. is higher is that an invisible moisture

lm will form on the surface of materials and equipment.

This lm contains impurities, from the air, which allow it to

be a conductor. As electrostatic charges are generated, this

lm conducts the charges to ground before they can build

up sufciently high to cause a spark to jump.

Control of static electricity is important in many industries.

Printing plants need to eliminate the static electricity caused

problems of erratic feeding, sticking sheets, tacky ink and

misregistration of color. Textile mills can ill afford to have

huge electrostatic charges build up on spindles and cards.

Data Processing is especially sensitive to static electricity

as it can cause malfunction by improper feeding of cards

and paper, brittle tape and electrostatic discharges. Explosive production areas must be humidied. To chance a

static discharge in an explosive atmosphere is extremely

dangerous.

6 w w w. h e r r mi di f i e r- h v a c . co m

L o a d C al c u l a t io n G u i de

Page 7

“Dry Air” And Hygroscopic Materials

L o a d C a l c u l a t i o n G u i d e

HYGROSCOPIC materials (those able to take on or give

up moisture) are particularly sensitive to humidity changes

in their environment. Materials so classied would include

wood and wood products, paper and paper products, textiles, leather, ceramics, food and a long list of others.

These materials respond to their environment by taking on or

giving up moisture, thereby changing their REGAIN. When

these materials nally reach a balance, where they are stable and no longer take on or give off moisture, they are said

to have reached their EQUILIBRIUM MOISTURE CONTENT

(EMC).

When a hygroscopic material is stabilized at is EMC for a

particular temperature and R.H., there is little effect on the

material. The problems begin when the R.H. begins to drop

and the air pulls moisture from the material, upsetting its

EMC. When the material loses moisture it will shrink, warp,

crack, check, become thirsty for solvents, etc. This causes

problems not only with the material, but also with the machinery, nishing processes, coatings and so on. Weight and

texture are also affected.

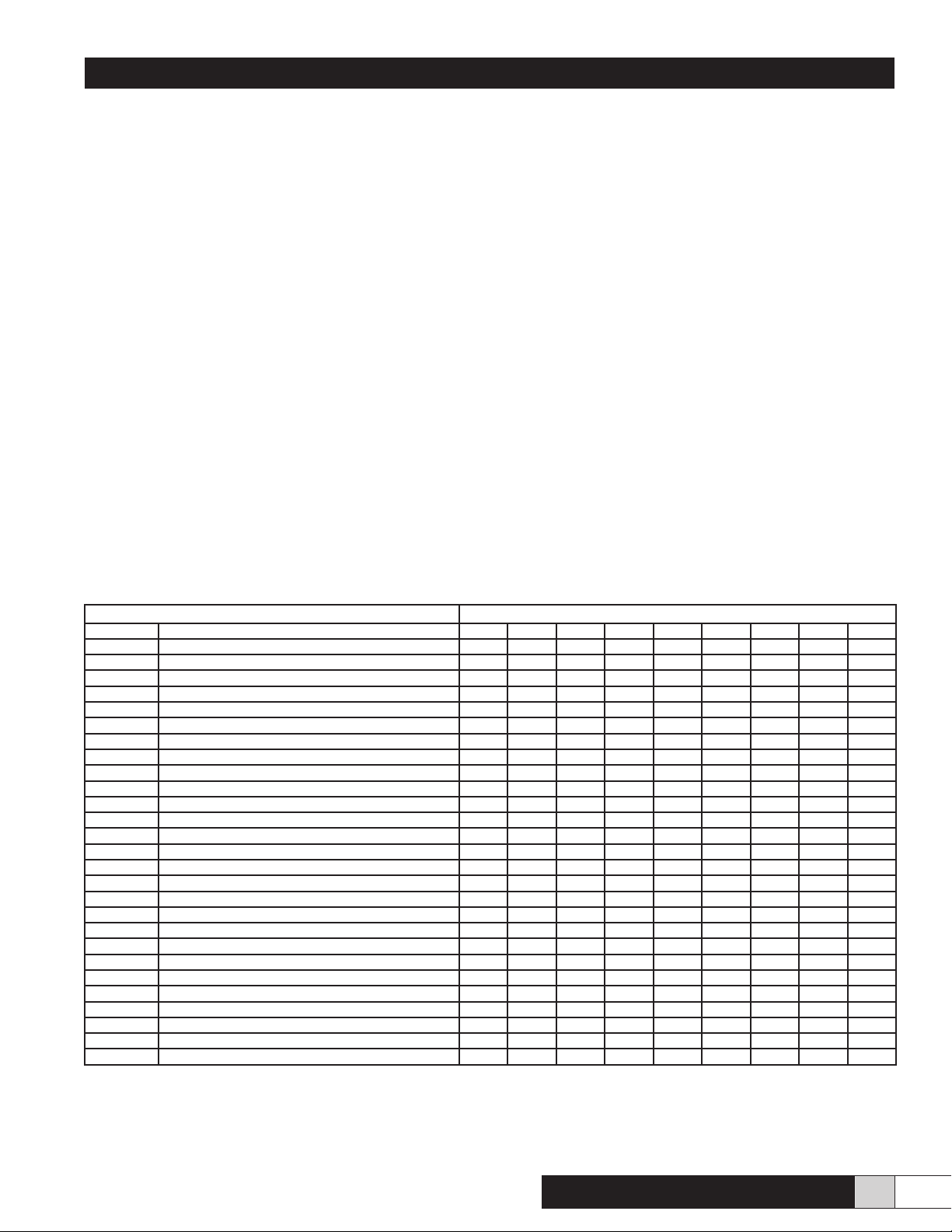

Table 1-C

Hygroscopic materials lose moisture to dry air... pick up moisture from humidied air. This can materially affect your prot!

REGAIN OF HYGROSCOPIC MATERIALS

Moisture Content expressed in Percent of Dry Weight of the Substance at Various Relative Humidities - Temperature 75 °F

When the EMC is upset to the point of damaging a product (cracking, splitting, warping) and rendering it unsaleable,

economic loss results. This includes the loss of any and all

energy required to make that product, (from the raw material rening to the nished product) if the product must be

scrapped, the additional energy input and labor expense

if the product is reworked, down time when machinery is

jammed or damaged and higher per piece costs if machinery must be run slower than normal to prevent electrostatic

buildup. For example, one woodworking plant reported savings of $900 a week after introducing controlled humidity to

the plant. One investment castings company reported savings of $4,800 per week and the textile industry was even

more dramatic with $6,700 per week! These savings are realized from better product workability, faster machine operation and production of less non-saleable units. Following is

a charge listing the Regain for several materials, after which

we shall take a look at some industries in depth.

Industry Materials Relative Humidity %

10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90

Baking: Crackers 2.1 2.8 3.3 3.9 5.0 6.5 8.3 10.9 14.9

Flour 2.6 4.1 5.3 6.5 8.0 9.9 12.4 15.4 19.1

White Bread 0.5 1.7 3.1 4.5 6.2 8.5 11.1 14.5 19.0

Leather: Sole Oak, Tanned 5.0 8.5 11.2 13.6 16.0 18.3 20.6 24.0 29.2

Printing: Paper-Com. Ledger - 75% Rag., 1% Ash 3.2 4.2 5.0 5.6 6.2 6.9 8.1 10.3 13.9

Paper-M.F. Newsprint - 24% Ash 2.1 3.2 4.0 4.7 5.3 6.1 7.2 8.7 10.6

Paper-White Bond Rag - 1% Ash 2.4 3.7 4.7 5.5 6.5 7.5 8.8 10.8 13.2

Paper-Writing - 3% Ash 3.0 4.2 5.2 6.2 7.2 8.3 9.9 11.9 14.2

Textile: Cotton - Absorbent 4.8 9.0 12.5 15.7 18.5 20.8 22.8 24.3 25.8

Cotton - American-cloth 2.6 3.7 4.4 5.2 5.9 6.8 8.1 10.0 14.3

Cotton - Sea Isle-roving 2.5 3.7 4.6 5.5 6.6 7.9 9.5 11.5 14.1

Hemp - Manila & Sisal 2.7 4.7 6.0 7.2 8.5 9.9 11.6 13.6 15.7

Jute - Average grade 3.1 5.2 6.9 8.5 10.2 12.2 14.4 17.1 20.2

Linen - Dry Spun - yarn 3.6 5.4 6.5 7.3 8.1 8.9 9.8 11.2 13.8

Rayon - Cellulose - Acetate-ber 0.8 1.1 1.4 1.9 2.4 3.0 3.6 4.3 5.3

Rayon - Cupromonium - Average Skein 4.0 5.7 6.8 7.9 9.2 10.8 12.4 14.2 16.0

Rayon - Vicose Nitrocel 4.0 5.7 6.8 7.9 9.2 10.8 12.4 14.2 16.0

Silk - Raw Cheyennes - Skein 3.2 5.5 6.9 8.0 8.9 10.2 11.9 14.3 18.8

Wool - Australian - Marino - Skein 4.7 7.0 8.9 10.8 12.8 14.9 17.2 19.9 23.4

Cigarette 5.4 8.6 11.0 13.3 16.0 19.5 25.0 33.5 50.0

Wood: Timber - Average 3.0 404 5.9 7.6 9.3 11.3 14.0 17.5 22.0

Glue - Hide 3.4 4.8 5.8 6.6 7.6 9.0 10.7 11.8 12.5

Misc.: Charcoal - Steam Activated 7.1 14.3 22.8 26.2 28.3 29.2 30.0 31.1 32.7

Gelatin 0.7 1.6 2.8 3.8 4.9 6.1 7.6 9.3 11.4

Silica Gel 5.7 9.8 12.7 15.2 17.2 18.8 20.2 21.5 22.6

Soap 1.9 3.8 5.7 7.6 10.0 12.9 16.1 19.8 23.8

Starch 2.2 3.8 5.2 6.4 7.4 8.3 9.2 10.6 12.7

L o a d C al c u l a t io n G u i de

w w w. h e r r mi di f i e r- h v a c . co m

7

Page 8

L o a d C a l c u l a t i o n G u i d e

Woodworking And Humidication

In the woodworking industry controlled humidication can often mean the difference between a protable operation and

bankruptcy. A company, manufacturing wood products, that

must reject one (1) out of ten units due to cracking, warping, splitting or checking suffers losses due to wasted raw

materials, wasted labor and wasted energy in the production

of nonsaleable items. These losses can be profound- particularly the energy loss, as this goes all the way back to the

cutting of the tree and transporting of the lumber. If the damaged unit can be reworked there is still the added cost of doing so. These losses and added costs must be added to the

costs of producing the other nine out of ten saleable units. It

is not hard to see why controlled humidication can result in

substantial savings for the woodworking industry.

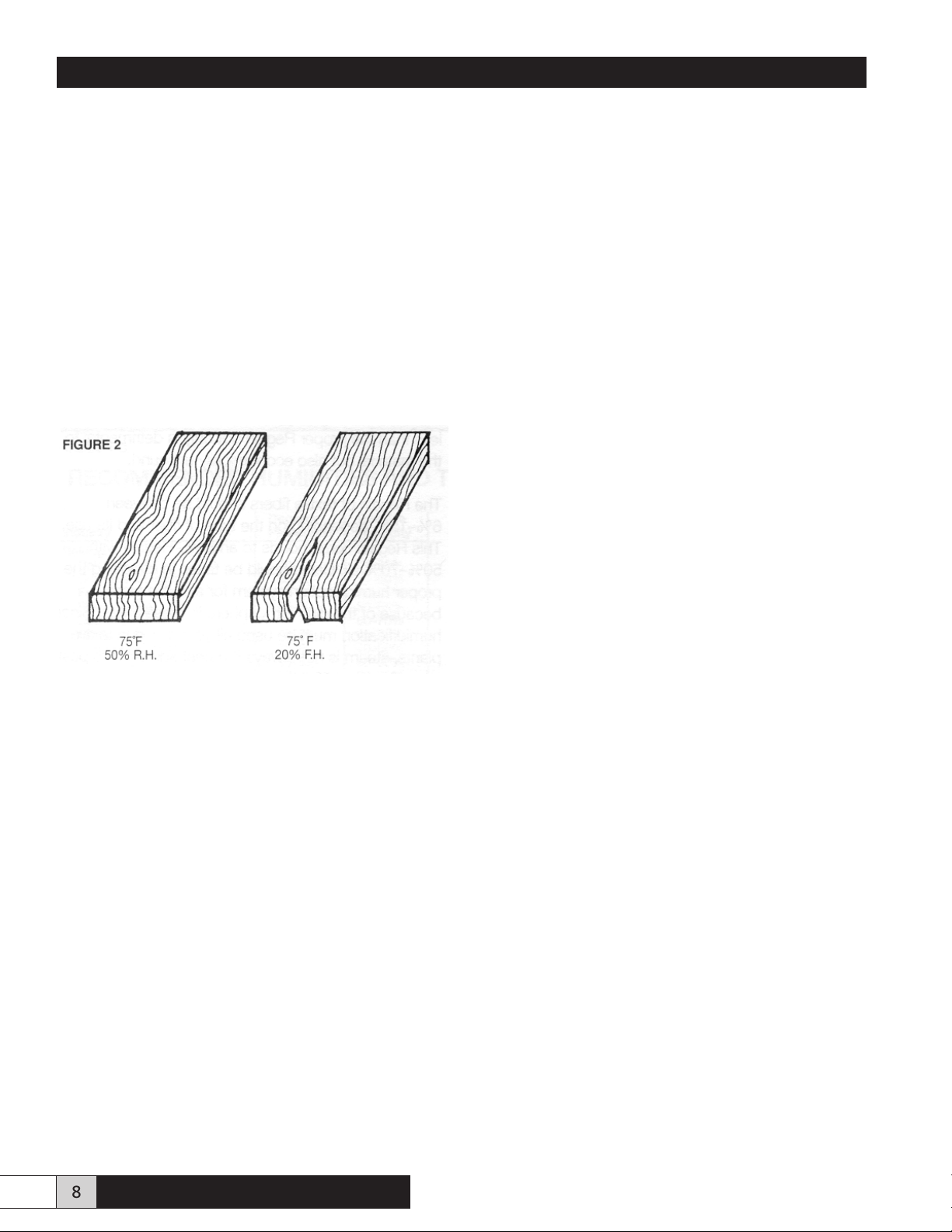

WHY DOES WOOD CRACK OR WARP?

As wood loses moisture it shrinks. However, the tangential

shrinkage is much greater than the radial shrinkage. This

causes dimensional changes and instability in the wood and

the wood pulls apart, along the grain causing cracks. If the

wood is strong enough not to crack it will warp as the uneven shrinkage occurs. This is why it is important to condition wood to the proper Regain for best workability and then

stabilize it at the corresponding EMC by maintaining proper

humidity control.

WHAT IS THE BEST R.H. FOR WOOD?

The Regain should be between 5%-9% depending on the

species of wood and its use. This regain corresponds to the

EMC with 35%--45% R.H. air at 75°F. If you are able to

maintain the proper EMC Regain in the wood by maintaining the proper R.H. in the air surrounding it, rejects will be

sharply reduced, production efciency increased and prots

increased!

WHAT ABOUT GLUING AND FINISHING?

HOW IS WOOD AFFECTED BY HUMIDITY?

Wood is a hygroscopic material, able to take on or give up

moisture to the surrounding air. As wood takes on moisture

it swells. As it gives up moisture it shrinks. It does so in response to the changing atmospheric conditions of temperature and humidity, humidity having the greater effect. The

amount of moisture in the wood, expressed as a percentage

of its dry weight, is referred to as its REGAIN. This Regain

varies with temperature, relative humidity and type of material. When the Regain of a piece of wood reaches a balance,

where it is no longer taking on or giving up moisture, it is said

to have reached its EQUILIBRIUM MOISTURE CONTENT

(EMC) for that particular temperature and R.H. At this state

the wood is stable and will not change dimensionally. The

EMC changes with temperature and R.H. For example, a

piece of wood with an EMC regain of 9.3% at 75F 50% R.H.

will have an EMC regain of only 4.4% at 75°F 20% R.H. (See

Table 1-C.)

When dry thirsty air pulls moisture from it, the wood also becomes thirsty, so that when a varnish or other coating is applied the dry wood will act like a sponge and quickly absorb

the liquid. This leads to a dull nish or excessive use of coating to produce a bright nish. Glue will not cure properly or

quickly if the air and wood that it is in contact with are too dry.

WHAT R.H. DO I NEED FOR GLUING AND FINISHING?

Generally, 40%-50% R.H. is recommended for gluing and a

minimum of 60% R.H. recommended for nishing areas. You

must remember that if wood has not been conditioned previously and enters the humidied gluing and nishing areas

dry and thirsty, it will still produce the problems experienced

before. It is important to maintain the stability of your wood,

from start to nish, by proper humidity control. The economic gains from proper humidity control, can often pay for the

equipment in less than one year.

Paper Products And Humidication

The common problems experienced in every paper industry,

whether it involves manufacture of cardboard boxes, sheet

paper, etc. are: curling of stock, cracking on folds of paper

or boxes, failure to feed properly into machines and glue

that won’t hold. Generally these problems are experienced

in the winter heating season when the R.H. indoors is low.

Once again, the cause of these problems is moisture loss

from materials. Paper and paper products are made up of

brils. When these brils lose moisture they shrink and become brittle.

8 w w w. h e r r mi di f i e r- h v a c . co m

L o a d C al c u l a t io n G u i de

Page 9

L o a d C a l c u l a t i o n G u i d e

This brittleness contributes to cracking when the paper or

cardboard is folded, stretched or deformed. Weight and

strength are also reduced by this loss of moisture. Glues

sometimes will not hold, (for the same reasons as discussed

in woodworking) and printing of cardboard boxes dulls or

misregisters.

The recommended Regain of cardboard is 5% to 7%. This

corresponds to the EMC with air in the range of 40%-50%

R.H., depending on the composition of the paper. (Refer to

Table I -C.) Maintaining a proper level of R.H. will result in

less scrap, less rejects and increased production efciency

Printing And Humidication

The problems suffered in the printing industry are basically

the same as those found in the paper products industries.

The specic problems of the printing industry would include:

brittle paper, curling edges, smeared ink and electrostatic attraction between papers and rolls. These problems are, once

again, caused by dry air pulling moisture from the bers in

the paper.

Paper curling is caused because, as in paper products, moisture loss causes uneven shrinkage of the paper and causes

it to curl with the grain. This leads to difcult handling and

web breakage as paper is fed through the press.

An additional problem encountered in the printing industry

is that of electrostatic charge accumulation. As paper is unwound off a roll, or papers are shufed against each other,

they build up electrostatic charges which cause attraction

between sheets and rolls. The result is to cause the paper unwinding off a roll to pull taut. This also occurs as the

charged paper is attracted to the rollers in the press. These

attractions put undue stress on the paper and, since paper

under these conditions would be dry and brittle, web breakage, misregistration of colors, smeared ink and folding-jogging problems result. These problems are best eliminated by

maintaining a R.H. above 45%.

Huge electrostatic charges can be built up as textiles are

spun and wound. These charges also slow down equipment.

Losses from production problems caused, by dry air can

amount to more than $7,000 per week!

There are also economic reasons to humidify in the textile

industry. The bers used in textiles are hygroscopic and as

such can increase or decrease in weight as they take on or

give up moisture. For example, a cotton yarn shipment of

1,000 pounds that is a 2% Regain will contain 20 pounds of

water. Another shipment at 8% Regain contains 80 pounds

of water. Both shipments weigh 1,000 pounds, including the

water, but the one with 2% Regain has 60 more pounds of

cotton. If the selling price of this cotton is $.40 per pound

it costs the manufacturer of the 2% Regain yarn 60 x $.40

= $24.00 to provide cotton in place of water to match the

weight of his competitor’s shipment. You can see where selling a hygroscopic material by weight at less than the proper

Regain not only is detrimental to the material but also economically unsound.

The Regain of textile bers should be between 6%-15% depending on the type of ber and its use. This Regain corresponds to an EMC Regain with 50%-70% air. Care should

be taken in choosing the proper humidication system for a

textile plant, because of the dirty atmosphere in these areas.

Since humidication must be used all year round in textile

plants, steam is not always the best answer. It is best to consult a humidication expert.

Food Storage, Processing And Humidication

Almost all foods are hygroscopic and will be affected by humidity, or lack of it, with regards to quality, texture, freshness

and taste. Potatoes stored in special humidied and cooled

areas stay meatier and resist sprouting and spoiling for longer periods of time. Apples stored in a proper humidity controlled environment will last longer in a fresh saleable state.

Meats processed in controlled humidity retain their quality

and bright moist color.

The recommended level of R.H. needed in the printing industry is roughly the same as that needed for paper products,

again depending on the composition of the paper. Newsprint,

which is generally about 24% Ash, would require 50%-65%

R.H. Writing paper, generally about 3% Ash, requires 40%50% R.H. (Refer to Table 1 -C.)

Textiles And Humidication

Humidication is vital to the textile industry, both for material value and operation efciency. When the R.H. is too low,

the bers become brittle and will break causing shutdown of

machinery and excessive “y” in the air.

L o a d C al c u l a t io n G u i de

Many ripening fruits and vegetables can be enhanced by

proper humidity control. The level of R.H. in food storage and

processing areas is often high-as high as 95% R.H. while

temperature must be kept low. Because of this low temperature and high humidity the best humidication equipment for

this application is usually atomizing equipment, since it will

add some evaporative cooling. (As we shall see later

on.) For the proper humidication level of R.H. needed for a

particular food, consult Table 1 -D.

w w w. h e r r mi di f i e r- h v a c . co m

9

Page 10

L o a d C a l c u l a t i o n G u i d e

Leather Processing And Humidication

Proper levels of controlled humidity (40%-60% R.H.) will

keep leather soft and pliable, helping it to resist cracking

when handled and worked. Leather should be stored in a

humidity controlled environment before working it to ensure

that it is soft, pliable and at the proper regain. Different tanning processes will require different levels of R.H. (See Table

1 -D.)

A Humidication Synopsis

There is not a single industry that cannot use humidication

in some are of production, either for material or personnel

benet.

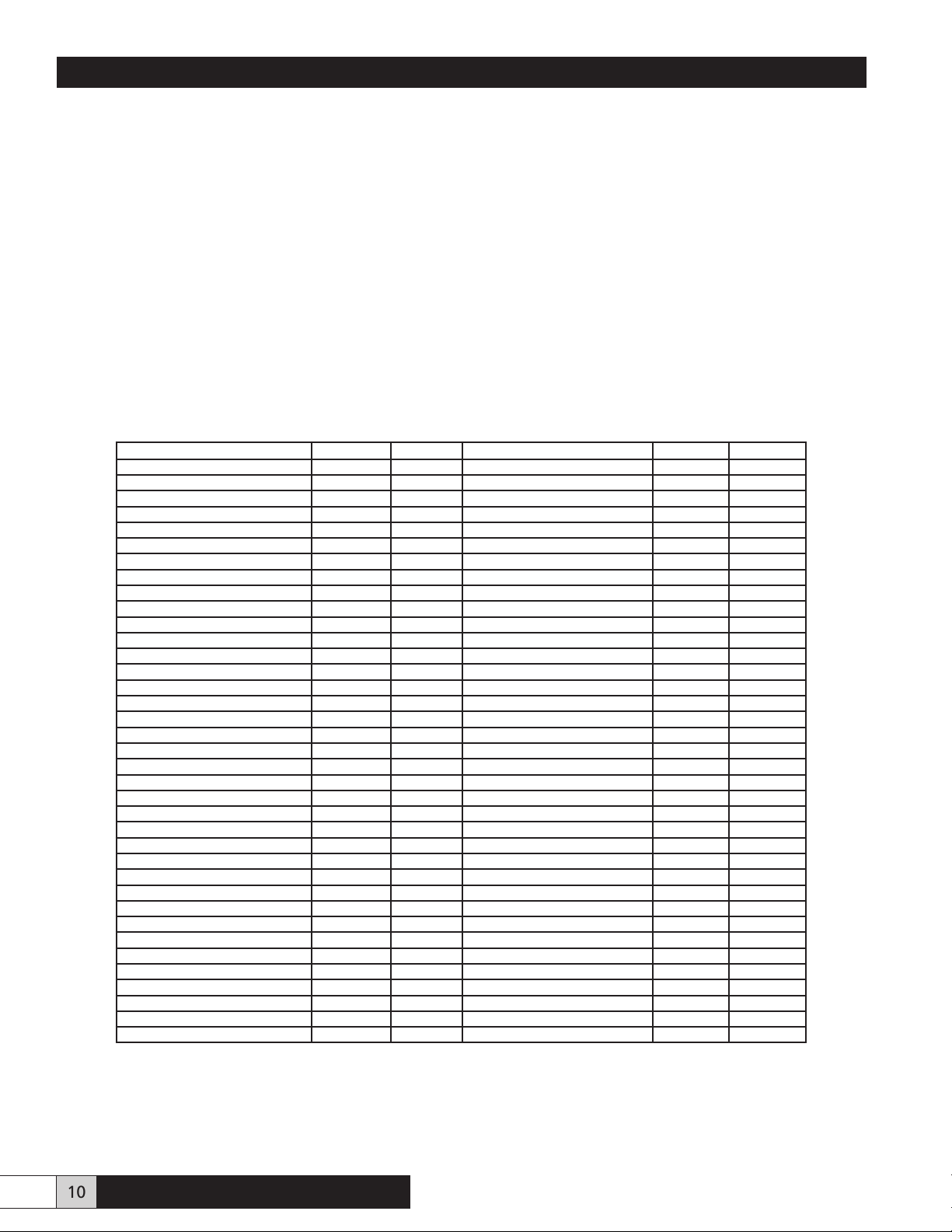

Table 1D

RECOMMENDED HUMIDITIES AND TEMPERATURES FOR VARIOUS INDUSTRIES

Industry °F % RH Industry °F % RH

Baking Hospitals:

Cake mixing 70-75 65% Nurseries 75 50-65%

Crackers & biscuits 60-65 50% Operating room 75 55%

Fermenting 75-80 70-75% Patients’ rooms 75 40-50%

Flour storage 65-80 50-65% Laboratories As required

Loaf cooling 70 60-70% Leather

Make-up room 75-80 65-70% Chrome tanned (dying) 120 45%

Mixer-bread dough 75-80 65-70% Vegetable tanned (drying) 70 75%

Proof box 90-95 80-90% Storage 50-60 40-60%

Yeast storage 32-45 60-75% Libraries & Museums 70-80 40-50%

Bowling Centers 70 35-45% Paint Application:

Cereal: packaging 75-80 45-50% Air drying lacquers 70-90 60%

Confectionary: Air drying oil paint 60-90 60%

Chocolate covering 62-65 50-65% Paper Products:

Centers for coating 80-85 40-50% Binding 70 50-65%

Hard candy 70-80 30-50% Printing & Folding 75-80 45-55%

Storage 60-68 50-65% Storage 75-80 40-60%

Cork Processing 80 45% Schools 72 35-50%

Computers: Textiles:

Data Processing 70-75 45-55% Cotton – carding 75-80 50-55%

Computer Mfg & Assembly 70-75 45-55% Cotton – spinning 60-80 50-70%

Electrical: Cotton – weaving 68-75 85%

Mfg. Cotton covered wire 60-80 60-70% Rayon – spinning 80 50-60%

Storage – general 60-80 35-50% Rayon – throwing 70 85%

Food: Silk Processing 75-80 65-70%

Apple storage 30-32 75-85% Woolens – carding 80-85 65-70%

Banana – ripening 68 90-95% Woolens – spinning 80-85 50-60%

Banana – storage 60 85-90% Woolens – weaving 80-85 60%

Citrus fruit – storage 60 85% Tobacco:

Egg storage 35-55 75-80% Cigar & cigarette 70-75 55-65%

Grain storage 60 30-45% Other processing & storage 75 70-75%

Meat – beef aging 40 80% Casing room 90 88-95%

Mushroom – storage 32-35 80-85% Woodworking:

Potato storage 40-60 85-90% Finished products 65-70 35-40%

Tomato –storage 34 85% Gluing 70-75 40-50%

Tomato – ripening 70 85% Manufacture 65-75 35-40%

Greenhouses 80 70-80% Painting – lacquer (static control) 70-90 60%

Ofces, hospitals, nursing homes, libraries, museums, furniture stores, bowling alleys, etc., all contain hygroscopic

materials (wood, carpets, etc.) which can be damaged by

dry air. Proper humication protects these materials and also

safeguard the comfort of personnel in these areas.

For an overview of some industries and their humidity requirements see Table I -D following. If your particular industry is not listed, contact Herrmidier Co., Inc. and we will

supply you with a humidication fact sheet for your industry

telling you why proper humidication is needed and how it

can be accomplished.

10 w w w. h e r r mi d i f i e r- h v a c. co m

L o a d C al c u l a t io n G u i de

Page 11

L o a d C a l c u l a t i o n G u i d e

SECTION III LOAD CALCULATIONS

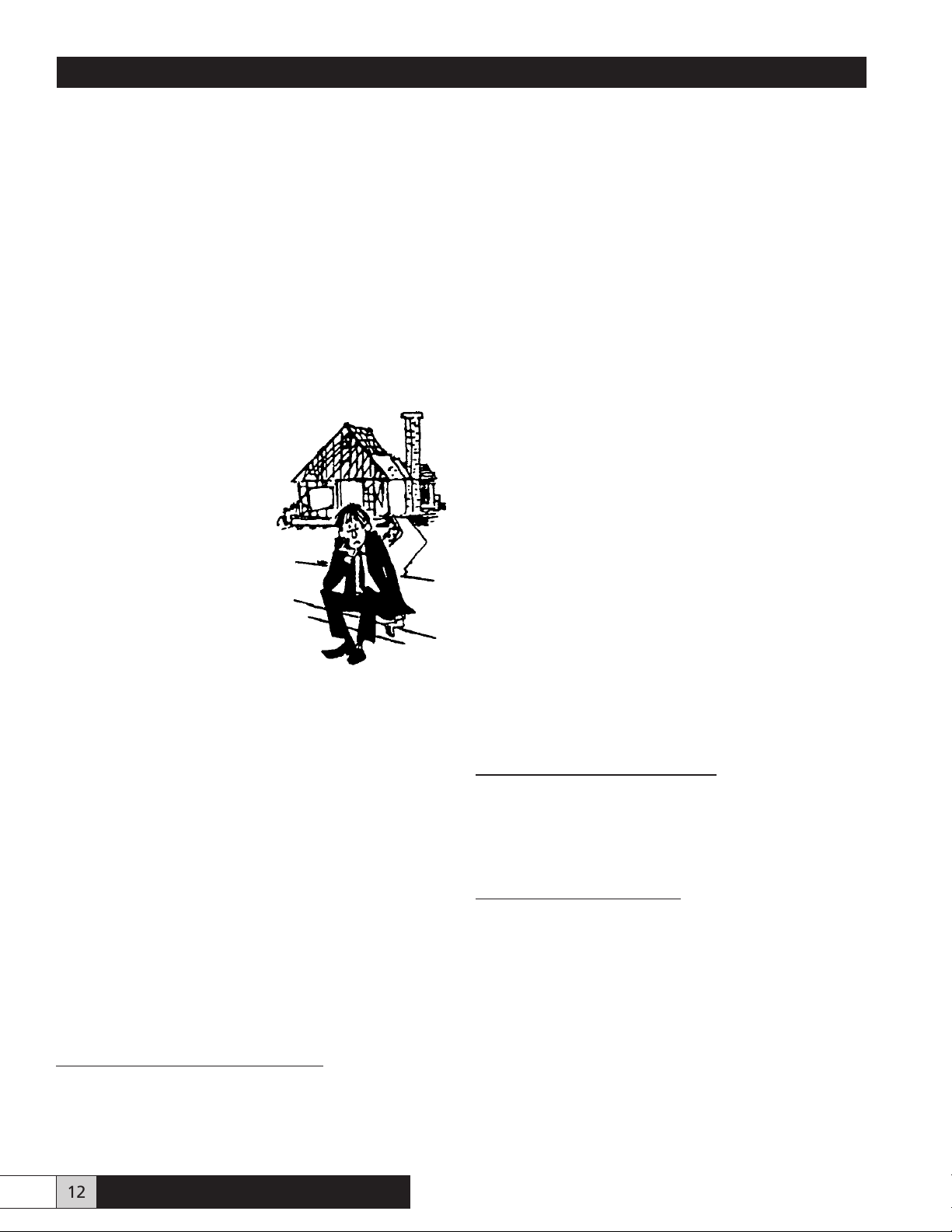

Knowing that controlled humidication is needed is the rst

step toward increasing productivity and cutting losses. The

second, and most important step, is to accurately determine the amount of moisture required to be added to the air

to reach the target R.H. level. A humidication project that

starts out with good intentions can fall at because the demand load was not calculated accurately and too little or too

much humidication equipment was installed. Following is a

simple, accurate guideline for determining your MAXIMUM

HUMIDIFICATION DEMAND LOAD. Help with calculating

this can be obtained by returning form I/C DI-5 to Herrmidier.

The Psychrometric Chart

All humidication calculations involve knowing the maximum amount of moisture a given quantity of air can hold at

saturation (100% R.H.), and being able, by calculations, to

compare this with the amount of moisture present and that

which is desired in that air. The amount of moisture in the air

is measured in grains per cubic foot. This gure is used in

calculations to eventually arrive at a demand load, in pounds

per hour, for the area to be humidied. The following Table

2-A shows the grains of moisture per cubic foot of air at specic temperature.

Table 2-A

°Fahrenheit Grains °Fahrenheit Grains

-10 .29 52 4.41

-5 .37 53 4.56

0 .48 54 4.72

5 .61 55 4.89

10 .78 56 5.06

15 .99 57 5.23

20 1.24 58 5.41

25 1.56 59 5.60

30 1.95 60 5.80

31 2.04 61 6.00

32 2.13 62 6.20

33 2.21 63 6.41

34 2.29 64 6.62

35 2.38 65 6.85

36 2.47 66 7.07

37 2.56 67 7.31

38 2.66 68 7.57

39 2.76 69 7.80

40 2.86 70 8.10

41 2.97 71 8.32

42 3.08 72 8.59

43 3.20 73 8.87

44 3.32 74 9.15

45 3.44 75 9.45

46 3.56 76 9.75

47 3.69 77 10.06

48 3.83 78 10.40

49 3.97 79 10.80

50 4.11 80 11.04

51 4.26 81 11.40

82 11.75 107 24.26

83 12.11 108 24.93

84 12.49 109 25.62

85 12.87 110 26.34

86 13.27 111 27.07

87 13.67 112 27.81

88 14.08 113 28.57

89 14.51 114 29.34

90 14.94 115 30.13

91 15.39 120 34.38

92 15.84 125 39.13

93 16.31 130 44.41

94 16.79 135 50.30

95 17.28 140 56.81

96 17.80 145 64.04

97 18.31 150 72.00

98 18.85 155 80.77

99 19.39 160 90.43

100 19.95 165 101.00

101 20.52 170 112.60

102 21.11 175 125.40

103 21.71 180 139.20

104 22.32 185 154.30

105 22.95 190 170.70

106 23.60 195 188.60

There are basically three (3) humidication load factors and

two (2) humidication reduction factors:

HEATING LOAD: For desired R.H. at maximum indoor temperature maintained when outdoor temperature is at minimum heating design level.

COOLING LOAD: To replace moisture removed by condensation from cooling process -- air conditioning and/or refrigeration.

PRODUCT LOAD: To condition product to nal desired Regain when received under other conditions. This load could

be plus or minus.

PROCESS REDUCTION: Moisture vapors emitted by processes decrease humidication load.

PEOPLE REDUCTION: People give off 0.2 lbs. per hour

when seated; 0.9 lbs. per hour when active, thereby decreasing humidication load. We shall take a more, in depth,

look at these factors in this section.

L o a d C al c u l a t io n G u i de

w w w. h e r r mi di f i e r- h v a c . co m

11

Page 12

L o a d C a l c u l a t i o n G u i d e

Heating Load

To determine the maximum demand load due to heating observe the following steps.

Step 1. Determine the amount of moisture which must be

added per cubic foot of air to be humidied. As you know,

heating air lowers its R.H., but does not obliterate it, so the

moisture already in the cool air before heating must be determined and subtracted since this moisture is already available in the heated air. Using Table 2-A, rst determine the

maximum design indoor temperature and record the grains

of moisture listed to the right of that temperature, then multiply the grains (at 100% R.H.) times the desired level of R.H.

(a percentage) to arrive at the grains of moisture per cubic

foot of air necessary to maintain the desired R.H.

ALWAYS CONSULT AN

EXPERT AT THE START

Step 2. Determine the maximum volume of air per hour that

will need to have moisture added to it. Natural ventilation,

exhaust and makeup air must be considered. You should use

the largest of these, but not all three.

Example: A large woodworking plant.

1. The area of the plant is 100’ x 200’ x 15’H = 300,000

cu. ft. - If it is tight construction, you would use one air

change per hour. If it is loose or old construction - 1-1/2

air changes per hour. Three or four exposed walls and

shipping doors - 2 air changes per hour. Never use less

than one air change per hour unless sealed off with no

trafc in or out. In this example, the building has four exposed walls and two shipping doors. Volume of air to be

humidied is 300,000 cu. ft. x 2 = 600,000 CFH.

2. The plant contains exhaust equipment exhausting 20,000

CFM to the outside. This volume would be 20,000 CFM

x 60 min./hr. = 1,200,000 CFH. (Note that this volume is

greater than the volume calculated by plant area.)

3. The plant has a makeup air system that supplies 15,000

CFM of outside air to the plant. This volume is 15,000

CFM x 60 min./hr. = 900,000 CFH.

Now take the minimum design outdoor temperature (you are

essentially heating inltrated outdoor air) and its grains of

moisture (at 100% R.H.) times the minimum expected R.H.

to arrive at the moisture content already available before

heating.

Next simply subtract the outdoor design moisture from the

indoor design moisture and arrive at the grains of moisture

per cubic foot of air needed to be added to the heated air to

reach design conditions of R. H.

Example: (From Table 2-A)

Indoor Design Moisture @ 70°F 65% R.H.

8.10 gr. x .65(%) = 5.2 gr./cu. ft.

Outdoor Design Moisture @ 0°F 50% R.H.

.48gr.x.50(%) = .24 gr./cu. Ft.

The greatest volume of air is due to the exhaust - 1,200,000

CFH. This is the maximum volume of air that must be humidied in any given hour. You will note that we are exhausting 1,200,000 CFH but making up only 900,000 CFH. The

balance of 300,000 CFH is brought in by forced inltration

through cracks around doors, windows, etc. It is not this exhaust that we wish to humidify but rather, the air replacing it.

Step 3. THE MAXIMUM HEATING DEMAND LOAD is now

calculated using the following formula:

(step 1) (step 2)

gr. Moisture needed/cu. ft. x CFH air =

7,000 gr./lbs.

lbs. of water per hour required.

or, from the example:

5.02 gr./cu. ft. x 1,200,000 CFH = 860 lbs./hr.water

7,000 gr./lbs.

Indoor Design Moisture = 5.26 gr./cu. ft.

-Outdoor Design Moisture = .24 gr./cu. ft.

Moisture to be added = 5.02 gr./cu. ft

12 w w w. h e r r mi d i f i e r- h v a c. co m

L o a d C al c u l a t io n G u i de

Page 13

L o a d C a l c u l a t i o n G u i d e

So, the MAXIMUM HEATING DEMAND LOAD for the woodworking plant in the example would be 860 lbs. of water

needed to be added per hour when the outside air is at O°F.

Weather Data and Design Conditions (from the ASHRAE

Handbook) do NOT give sufcient information to determine

the moisture content of outside air at various temperatures.

It is necessary to seek assistance from the U.S. Weather

Traditional heating systems are rather easy to calculate humidication demand loads for, however, with the advent of

economizer cycle heating and cooling systems this calculation gets a bit more complicated as we shall see.

Bureau, Aviation Weather or the like in the area in which the

plant is located. You will need to know the MINIMUM level

of relative humidity experienced at the outside design temperature in the area and for 1O°F increments up to the temperature at which I00% outside air is admitted. With this data

Heating Load: Economizer Cycle

and the characteristics of the system, you can then calculate

the demand load for each outside temperature. The highest

In air handling systems using the economizer cycle, outside

air is added to return air in varying quantities to provide a set

mixed air temperature reaching the heating/cooling section

of the system. The amount of outside air added is based on

the outside air temperature and the desired mixed air temperature to be maintained. This volume of outside air is add-

load calculated becomes the maximum demand load for humidication. This maximum demand load will occur at some

outside air temperature OTHER THAN design temperature

when the Economizer Cycle is used. Following, in Tables 2-B

and 2-C, are typical characteristics of two economizer cycle

systems.

ed automatically in varying amounts as the outside air temperature changes. THE MAXIMUM DEMAND LOAD FOR

HUMIDIFICATION is based on the desired indoor conditions

the moisture content of the outside air added and the volume

of outside air being introduced.

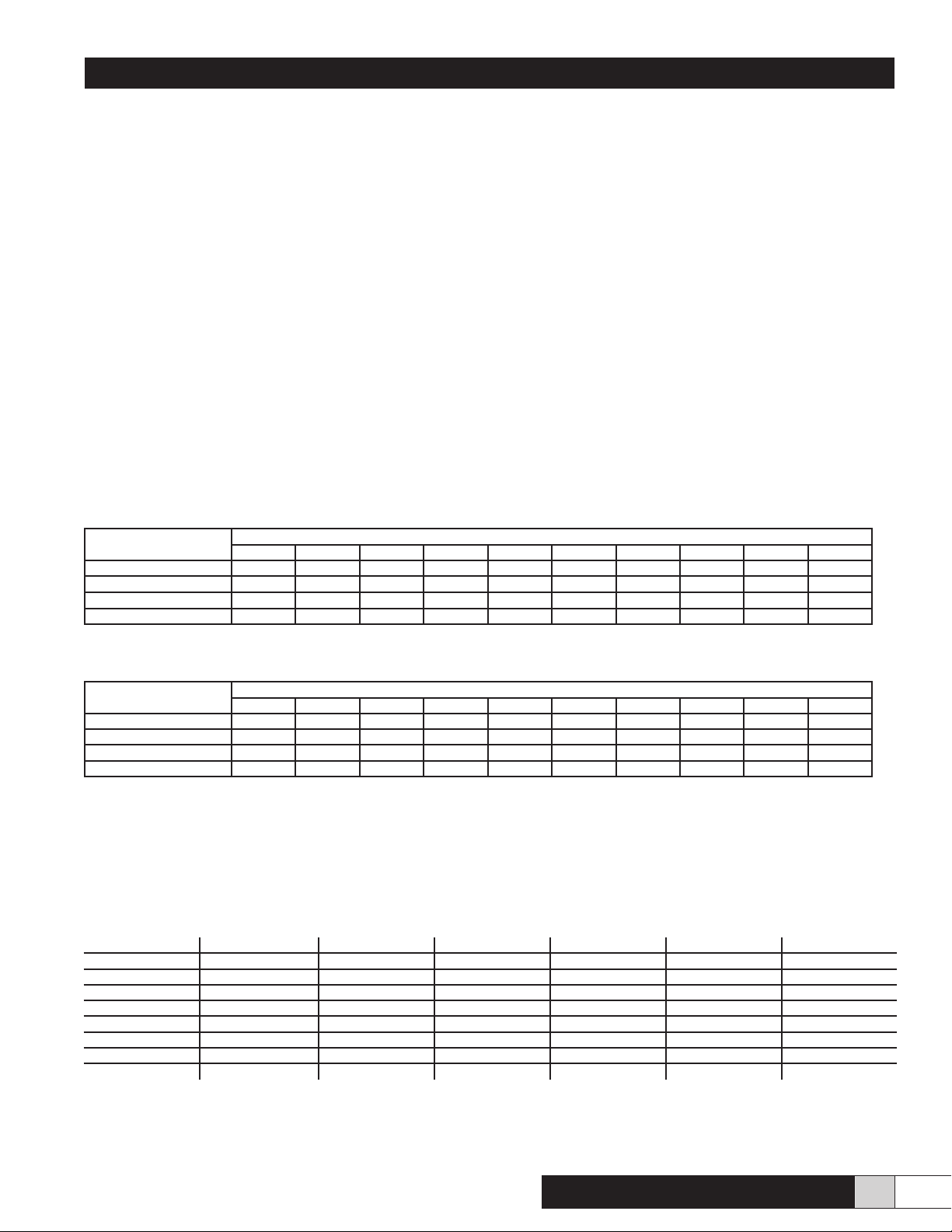

TABLE 2-B: ECONOMIZER WITH 70 F RETURN AIR

Mixed Air Temp. °F % OUTSIDE AIR REQUIRED AT TEMP. SHOWN °F

-10° 0° +10° +20° +30° +40° +50° +55° +60° +65°

50° 25 29 33 40 50 67 100

55° 19 21 25 30 38 50 75 100

60° 12 14 17 20 25 33 50 67 100

65° 6 7 8 10 13 16 25 33 50 100

TABLE 2-C: ECONOMIZER WITH 75 F RETURN AIR

Mixed Air Temp. °F % OUTSIDE AIR REQUIRED AT TEMP. SHOWN °F

-10° 0° +10° +20° +30° +40° +50° +55° +60° +65°

50° 30 33 38 45 56 71 100

55° 23 26 31 36 44 57 80 100

60° 18 20 23 27 33 43 60 75 100

65° 12 13 15 18 22 29 40 50 67 100

The above information must be provided for the system being used. Tables 2-B and 2-C are typical only. Therefore the HUMIDIFICATION DEMAND LOAD for an economizer system such as that shown in Table 2-B could be calculated as follows:

EXAMPLE:

Indoor Design Conditions: 70°F 40% R.H. (8.10x.40=3.24 gr/CF) Mixed Fair Temperature: 55°F

Outside Design Temperature: -10°F System CFM: 30,000

Outside Temp. °F % R.H. Minimum (1) Outside gr/CF (2) % Air(3) (Outside) CFM Air (Outside) gr to Add* Load lb/hr

-10 70 .203 19 5,700 3.037 148

0 65 .312 21 6,300 2.928 158

+10 60 .468 25 7,500 2.772 178

+20 55 .682 30 9,000 2.558 197

+30 50 .975 38 11,400 2.265 221

+40 45 1.260 50 15,000 1.980 254

+50 40 1.644 75 22,500 1.596 308

+55 35 1.712 100 30,000 1.528 393

(1)From Weather Bureau; (2)From Table 2-A; (3)From Table 2-B above; *7,000 gr/lb.

Information in (1) above is the key to the solution. The maximum demand load for Humidication for systems using the Economizer Cycle is almost always at some outside temperature other than

the design temperature for the heating system.

L o a d C al c u l a t io n G u i de

w w w. h e r r mi di f i e r- h v a c . co m

13

Page 14

L o a d C a l c u l a t i o n G u i d e

Notice that the MAXIMUM HEATING DEMAND LOAD in this

example is 393 lbs./hr. which occurs at 55°F, not at design

outdoor temperature as with traditional heating systems.

Therefore, any humidication system installed to handle this

load will have to have a maximum capacity of 393 lbs./hr.

water output.

Cooling Load

As we have seen, moisture is removed by condensation during the cooling process as the air is cooled below its dew

point and then reheats to room temperature. This condensed

moisture must be replaced when its loss causes the R.H. to

fall too low. To determine the maximum demand load due to

cooling observe the following steps:

Step 1. Determine the amount of moisture per cubic foot of

air that will be removed by condensation during the cooling

process as this will have to be replaced. This is done by using Table 2-A to determine the grains of moisture per cubic

foot of air at indoor design temperature and R.H., then determining the grains of moisture per cubic foot of air after it has

been cooled and subtracting this gure from that obtained for

the design temperature and R.H.

In determining the amount of moisture in the air after it has

been cooled, it is necessary to know the air temperature

drop across the cooling coils. This is usually a 15°F drop

with standard air conditioning equipment, but can vary from

manufacturer to manufacturer. It is best to check. Further,

the R.H. of the air after cooling will be about 85% rather than

100% because, only that portion of the air in contact with

the cooling coils will be cooled to coil temperature with condensation resulting. The coil temperature will be less than

the exit air temperature. The following example will illustrate

Step 1.

Step 2. Determine the volume of air passing over the cooling coils per hour. This is usually about 400 CFM per ton of

rated capacity for standard air conditioning equipment, but

this may vary with the make of equipment. It is always best

to check. Computer room air conditioning equipment is often

designed for 500-800 CFM per ton of rated capacity.

Example:

60 ton air conditioning

60 x 400 CFM = 24,000 x 60 min./hr. = 1,440,000 CFH

Step 3. Since almost all standard air conditioning equipment

is usually slightly overrated to allow it to shut down periodically and defrost, it is necessary to determine the maximum

“ON” time during any given hour, since this is when moisture is being removed from the air. This is usually 80%, but

should be checked, as special equipment may be designed

to cool rapidly and use less “ON” time.

Step 4. The MAXIMUM COOLING DEMAND LOAD for humidication can now be calculated using the following formula:

gr./CF needed x CFH x “ON” time

7,000 gr/lb. = lbs./water req.

Using the preceding examples in Steps 1-3:

1.11 gr./CF x 1,440,000 CFH x.80 “ON” = 183 lbs.

7,000 gr./lb. water/hr.

In this example, the MAXIMUM COOLING DEMAND LOAD

is 183 lbs. water/hr. Therefore, any humidication system

installed to handle this load will have to have a maximum

capacity of 183 lbs./hr. water output.

Example:

60 tons air conditioning (standard) maintaining 70°F at 65%

R.H.

Moisture content of air at design

70°F, 65% R.H. = 8.10 gr./CF x .65(%) = 5.26 gr./CF

-Moisture-content after cooling

55°F, 85% R.H. = 4.89 gr./CF x .85(%) = 4.15 gr./CF

Moisture removed during cooling= 1.11 gr./CF

Therefore we must replace 1.11 grains of moisture per cubic

foot of air to return the air to the desired condition of 70°F,

65% R.H. after cooling in this example.

14 w w w. h e r r mi d i f i e r- h v a c. co m

Cooling Load- Low Temperature (32°F-47°F)

In special applications, such as cold storage, the cooling

equipment (refrigeration) is usually designed to have an air

temperature drop across the coils of less than 15°F, to move

a greater volume of air across the coils than the 400 CFM per

ton experienced with standard air conditioning equipment

and to have a denite “OFF” cycle for defrosting.

L o a d C al c u l a t io n G u i de

Page 15

L o a d C a l c u l a t i o n G u i d e

Air temperature drop across the coils can be considerably

less than 15°F and must be known to accurately calculate

the humidication demand load for cooling. Also, the CFM

air ow across the coils is high and combined with the small

temperature drop, across the coils, will result in less moisture being condensed out of the air onto the coils. Generally,

its safe to gure the exit R.H. at about 90%-95% R.H. The

“OFF” cycle for defrosting is a denite and planned period

during each 24 hours and is usually expressed as “Runs 16

hours out of 24.” You should NOT correct for the “OFF” cycle

in this case since the equipment runs continuously for 16

hours and will remove moisture that must be replaced, continuously.

Example:

Design Conditions: 34°F 95% R.H.

Cooling Capacity: 30 Tons

24,000 CFM across coils

10°F Air temperature drop

Room Air:

34°F 95% R.H. = 2.29x.95(%) = 2.18 gr./CF

-Exit Air:

24°F 90% R.H. = 1.50x.90(%) = 1.35 gr./CF

Moisture removed by Cooling = .83 gr./CF

Using humidication demand load formula:

24,000 CFM x 60 min./hr.x.83 gr./CF = 170 lbs/hr. water

7,000 gr./lb.

Product Load

Many products made of or containing hygroscopic materials

will absorb or give up moisture and as such will need to be

conditioned to the proper Regain for shipment. This load only

occurs as a viable factor in the overall MAXIMUM HUMIDIFICATION DEMAND LOAD when large amounts of products

are being conditioned rapidly, such as textiles. The procedure for determining the product load is relatively simple if

you observe the following steps.

Step 1. Determine the MAXIMUM change in Regain of the

material during processing, using Table I-C to determine the

Regain of the material before and after conditioning and nd

their difference.

Example:

A plant processing 40 tons/hour of product received at 4%

Regain and shipped at 5% Regain will need to add 1% gain

as follows:

Shipping Regain = 5.0%

-Regain when received = 4.0%

Gain = 1.0%

Step 2. Determine the MAXIMUM amount of product, in

pounds, to be processed in any one hour.

Example:

40 tons/hr. x 2,000 lbs/ton = 80,000 lbs. hr.

Therefore, a humidication system designed to handle this

demand must be able to supply a maximum of 170 lbs. water

per hour. The above factors are for illustration. The individual

factors must be determined for each special application. It is

helpful to consult a humidication expert who, no doubt, has

had prior experience with these special applications.

Herrmidier has had extensive experience in all elds of low

temperature humidication, including cold storage as low as

34°F. For a list of previous installations or sizing and recommendations for your own application consult your Herrmidier Representative.

The Herrmidier dual-pneumatic atomizing system is particularly adaptable to cold storage humidication applications.

It has been used successfully to maintain levels as high as

95% R.H. at temperatures as low as 34°F without wetting of

oors.

Step 3. Calculate the MAXIMUM PRODUCT LOAD by taking the maximum amount of product processed per hour

times the gain needed.

Example:

80,000 lbs./hr.x.01 (% gain) = 800 lbs. water/hour

Therefore, any humidication system designed for this application will have to have a maximum capacity of 800 lbs.

water per hr. IN ADDITION to any heating or cooling load.

L o a d C al c u l a t io n G u i de

w w w. h e r r mi di f i e r- h v a c . co m

15

Page 16

L o a d C a l c u l a t i o n G u i d e

Process Reduction

From measurement or design data, determine the amount of

moisture vapor being given off by any sources in the plant,

such as hot water washes, steam curing, etc. This will decrease the maximum demand load for humidication whenever the process is in operation. Be sure it is effective at all

times that the maximum demand load for humidication is

being experienced.

People Reduction

People present in an area will give off moisture and, if enough

people are present, can affect the maximum humidication

load. People give off moisture at a rate of approximately .2

pounds per hour per person if seated and .9 pounds per hour

per person if active. This moisture can be deducted from

the maximum humidication demand load. Be sure these

people are present at all times when the maximum humidication demand load exists, because when they leave, the

maximum humidication demand load will increase by that

amount and if the humidication system was designed for

the load with people present, it will be undersized and unable to maintain the desired level of R.H. which could result

in product damage.

Maximum Demand Load For Humidication

4. Consider the dew point of the humidied atmosphere and

be aware of condensation problems that can occur on cold

surfaces such as: steel roof deck, single glazed windows,

aluminum window and door frames, etc. Dew point is the

temperature at which condensation will begin to occur when

the humidied air is cooled to that level.

5. Check the psychometrics and be sure the volume of air

can absorb the amount of water vapor you will be adding.

(DO NOT EXCEED 100% R.H.)

6. Cold air is difcult to humidity as it does not give up heat

as readily. Special equipment must sometimes be used.

7. Cold fresh air make-up can cause condensation problems

in ducts. Be careful where humidity is introduced.

8. “Free Cooling” using cold outside air can be costly by adding greatly to the maximum demand load for humidication.

It is usually more economical to recirculate the humidied air

and cool it, as required, using air conditioning or refrigeration

equipment.

9. Be sure adequate services are available, or can be obtained; i.e., water, water pressure, electrical, compressed air,

steam, etc.

THE MAXIMUM DEMAND LOAD FOR HUMIDIFICATION

for a plant or building consist of: the Heating or Cooling load,

whichever is greater, plus or minus the Product load (if any),

minus the Process reduction (if any) and the people reduction (if any). There are several other factors and pitfalls to be

aware of. These will be discussed next.

HELPFUL GUIDE LINES

1. Area to be humidied must be isolated from non- humidied areas as moisture travels to dry area by Dalton’s Law of

Partial Pressures. Open doors, elevator shafts, etc. will allow

moisture to escape.

2. WHen a common air handling system is in use and the

area to be humidied is served by a part of the system, you

must consider the air and moisture lost to non-humidied areas in guring demand load, or you must humidify all the air

delivered to the humidied areas by the system; also, this

moisture loss to other areas can cause problems in those

areas if not properly controlled.

3. Be sure the structure will handle the level of relative humidity desired without damage due to condensation, etc.

Moisture migration into wails with no vapor barrier can create problems. Vapor barriers must be installed properly to

be effective in preventing moisture migration from humidied

areas. All barrier joints must be air tight.

10. It is critical to understand your water prior to selecting a

humidication system. Forward a complete water analysis or

water sample to Herrmidier and we can help you optimize

your equipment selection or suggest water pretreatment to

minimize maintenance and maximize performance.

11. For ducted applications, atomization systems require

special application considerations to insure complete evaporation and no duct wetting. Proper selection of controls,

modulation technique and installation location is critical to

satisfactory performance. Please contact Herrmidier for a

copy of our “Herrmidicool Technical Manual” prior to designing your system.

12. Consider rst cost, operating cost, installation cost and

the equipment’s ability to maintain your design conditions

under your system psychrometric limitations. Water quality is

vitally important as well. Simply using DI or RO water with a

system does not eliminate potential water problems!

13. Any humidication system must be accessible for maintenance, especially periodic cleanings.

Energy consumed in humidifying is of great importance.

Be sure to consider the efciency of the equipment you

select.

16 w w w. h e r r mi d i f i e r- h v a c. co m

L o a d C al c u l a t io n G u i de

Page 17

L o a d C a l c u l a t i o n G u i d e

SECTION IV TYPES OF EQUIPMENT

There are basically three types of humidication equipment: Atomizing, Evaporative and Steam. The type of humidication equipment used for any application is extremely

important and should be carefully selected with regards to

the level of R.H. desired to be maintained, the amount of

moisture needed to be added, services available, use of the

area being humidied, feed water equality and energy efciency. Following is an overview of each type of humidication equipment.

Atomization

This type of humidication equipment uses either CENTRIFUGAL or PNEUMATIC forces to break water up into a

ne mist which is discharged into the atmosphere where it

evaporates to the vapor state. This process is endothermic

and takes latent heat from the air to evaporate the mist. (1

000 BTUs are required to evaporate one pound of water.)

Because atomization takes only enough heat from the air

as is needed to evaporate the water, it is usually a very efcient process. Atomizing equipment must be able to deliver

tiny droplets of a consistent size over a relatively narrow size

range. No large droplets should fall before turning to the vapor state as this may cause damaged goods, wet oors, etc.

This puts physical limitations on capacities that can be realized and/or successfully applied in given situations under

known conditions.

to form tiny droplets. Some type of air moving method, usually air vanes, is needed to pick up the mist and convey it into

the air space to be humidied. This type of equipment works

well in the lower capacity ranges (a few pounds of water per

hour) both as free standing or installed in an air handling

system. Larger capacities run into droplet size problems. If

this type of equipment is used in a dirty atmosphere serious

clogging problems result and considerable maintenance is

required to keep its efciency at a satisfactory level. Also,

since there is usually a reservoir and air movement through

the equipment, algae formation and drying minerals can

result in clogging and the need for frequent maintenance.

Water spray nozzles that do not use air are considered to

be centrifugal atomizers and are NOT suited for humidifying

since their droplet size is seldom small enough to prevent

wetting of oors and materials.

Every droplet in the ne mist has the same chemical makeup

as the water supplied to the equipment. When the droplets

evaporate to the vapor state, minerals are left behind in the

form of a white powder-referred to as Mineral Fallout. Use of

softened water does NOT alleviate this problem because in

softening one mineral is simply being substituted for another.

Demineralizers and use of the Reverse Osmosis Process

will remove the minerals and prevent Mineral Fallout. This

Mineral Fallout is usually not a problem except that it is undesirable in certain applications such as computer rooms and

hospitals. There are basically two types of atomizing equipment: Centrifual and Pneumatic.

CENTRIFUGAL ATOMIZERS pump water from a reservoir

onto a rotating disc impeller. The centrifugal force created

throws the water against a breaker screen

PNEUMATIC ATOMIZERS use air pressure to break up water into a ne mist. A much smaller droplet size in the mist is

more readily attained with pneumatic atomizers

L o a d C al c u l a t io n G u i de

w w w. h e r r mi di f i e r- h v a c . co m

17

Page 18

L o a d C a l c u l a t i o n G u i d e

than with centrifugal atomizers. Pneumatic atomizers are

usually manufactured as heads which can be installed on a

ceiling or in a duct. Some pneumatic atomizers use only air

under pressure, and others use air and water under pressure.

A Pneumatic Atomizing System that uses only air under

pressure and draws water from open, nonpressurized tanks

is called a GRAVITY SYSTEM. This type of system uses

about 25 CFM of air per 100 lbs. of water atomized per hour,

or more. It is highly susceptible to algae and bacteria growth

in the tanks and clogging is a constant problem. Atomizing

heads of this type often drip at the end of an “ON” cycle and

therefore should not be placed over valuable equipment or

material.

Pneumatic atomizing heads that use air and water under pressure are called DUAL-PNEUMATIC ATOMIZING

HEADS. This is generally a closed system that works well

in unclean atmospheres. Air consumption is much less than

that for the gravity system, and there are no tanks to collect

algae and bacteria. Most of these systems however, will drip

on “start up” because the air and water line are pressurized

at the same time and water will split out of the head before

sufcient atomization pressure has built up in the air lines.

On “shut down” dripping may also occur because of residual

pressure in the water lines. Although most dual-pneumatic

atomizing heads contain a cleaning pin which effectively

cleans the water orice, droplets of water left in the atomizing

section of the head will evaporate and leave minerals behind

which can eventually clog the head. A frequent maintenance

schedule must be followed to insure that the heads will continue to operate satisfactorily.

HERRMIDIFIER’S DUAL-PNEUMATIC ATOMIZING SYSTEM uses a dual-pneumatic head which is activated by water

pressure so that no water can ow without being pressurized.

The design of the head allows the use of only 12 CFM of air

per 100 lbs. of water atomized, not the 25 CFM required by

some others! A special control system prevents water from

owing until sufcient air pressure has been reached to atomize every drop of water allowing not one drop to fall to the

oor! A stainless steel cleaning pin cleans the water orice

at the end of each “ON” cycle and the special control system blows the atomizing section of each head dry to prevent

dripping and clogging. The no-drip feature of this ingenious

system permits it to be installed right over production areas

with no fear of water dripping on equipment or materials. The

self- cleaning mechanisms of the system is so effective that

YEARLY MAINTENANCE is all that is required. The low air

and energy consumption of this system make it especially

attractive with today’s energy shortage.

Applications would include: woodworking, leather working,

textiles, bakeries, cold storage, printing, paper and investment casting. (See Bulletin I/C DP.)

HERRMIDIFIER’S HERRMIDIGOOL IN-DUCT AIR/WATER

ATOMIZING SYSTEM incorporates Herrmidier’s patented

Dual-Pneumatic atomizing heads and utilizing a system of

either pneumatic, electric or electronic control provides for

the installation with an air-handling ducted system. This

system automatically adjusts its output to exactly match demand. The adjustment is accomplished by either modulating

the ow rate of the water to the heads or by individually modulating each head. Multiple systems installed within one air

handier can be staged to insure maximum energy efciency.

Humidity receivers and transmitters installed within the air

handler and monitored through the Herrmidicool controls

cabinet insures the maintenance of precise levels of relative

humidity and provide that saturation and condensation will

not occur.

The need and the preference for an induct atomization humidication system is evident for both the benets of controlled humidication, as well as evaporative cooling. The

evaporative cooling benet is derived from the energy required to evaporate a pound of water. With a Herrmidicool

system, this energy is drawn directly from the ambient air

and is properly referred to as a conversion of sensible heat

to latent heat. As this energy is drawn from the air, a corresponding depression of the dry bulb temperature occurs and

thus “free cooling” is

provided. This can be directly translated to savings in mechanical cooling. The use of either de-ionized or reverse osmosis processed water allows for the use of this system in

clean room environments. Applications would include: Ofce

Buildings, Clean Rooms, Computer Rooms, and Manufacturing Areas. (See Bulletin I/C-HC.)

18 w w w. h e r r mi d i f i e r- h v a c. co m

L o a d C al c u l a t io n G u i de

Page 19

L o a d C a l c u l a t i o n G u i d e

Evaporation

This process actually evaporates the water to the vapor state

before it is discharged into the air. No droplets of water enter

the humidied air. Minerals contained in the water are left behind in the humidication equipment and must be removed

by periodic cleaning. No mineral fallout is experienced with

this type of equipment. Generally a bleedoff or blowdown

mechanism is built in to ush away concentrated minerals

and lengthen maintenance periods. Evaporative equipment

will work well on any quality of water.

Evaporation will occur off the surface on an open pan of water or off a saturated sponge. Since it requires 1000 BTU’s to

evaporate one (1) pound of water, heat is often added to the

water or air to enhance evaporation. There are four types of

evaporative humidiers: heated water and media, pan-coil,

heated air and media and air washers.

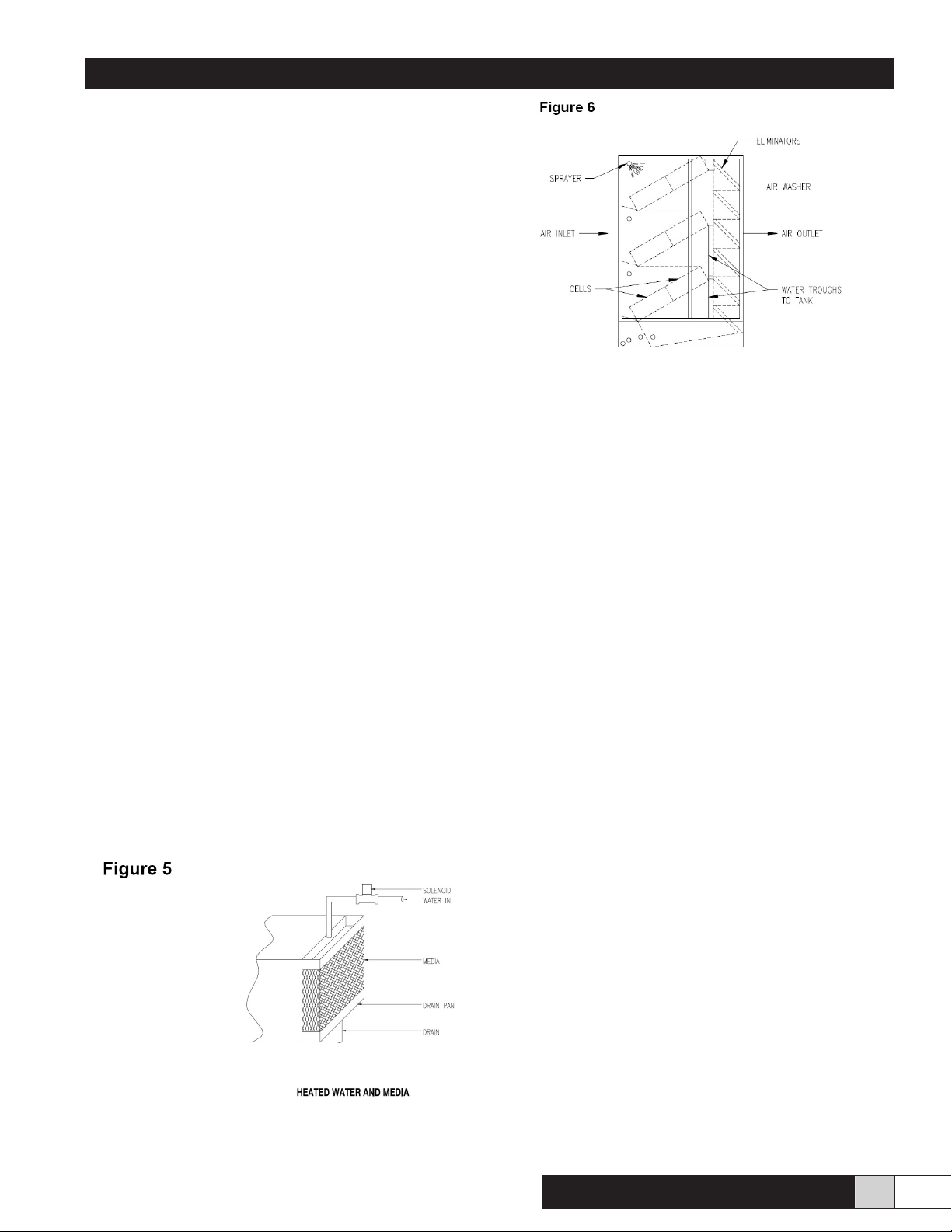

HEATED WATER AND MEDIA humidiers use a wetted

media through which heated water is poured and air blown

through to pick up the moisture. Although effective, large

amounts of heated water and energy are poured down the

drain in the necessary constant blowdown process. These

units are usually placed on a supply duct and therefore add

to the static pressure and blower costs. Overall energy efciency of this type of evaporative humidier is very poor.

AIR WASHERS use the evaporative process by passing

air over a continuous lm of water owing over deectors

which present a large surface of water in contact with the air.

The resulting surface evaporation raises the R.H. of the air.

Because of the evaporative cooling and their large size and

cost, air washers are usually used as evaporative coolers,

puriers AND humidiers. It is necessary that efcient “demistors” be placed in the air stream after the washer section

to remove and drain any water droplets that may have become entrained in the air stream. This often results in high

static loss across the washer. High levels of R.H. usually

cannot be attained by this method of humidication. (Upper

limit is about 55% R.H.)

Steam

This process injects live steam into the air to be humidied

either via manifold in a ducted air system, or direct discharge

into the area. Where good quality steam is available in sufcient quantities, a central steam humidication system will

have a very low “rst cost.” Where a steam boiler must be

installed for humidication, its rst cost is comparable to other forms of humidication. A steam boiler for humidication

must be able to supply good quality steam with very little

droplet entrainment. Any droplet entrainment will result in

mineral clogging of the humidication equipment since these

droplets contain the same chemical makeup as the water in

the boiler.

A central steam humidier consists of a condensate separator (to remove slugs of condensate) and a distribution

manifold (for insertion in ducts) or outlet (for area dispersion). Generally the steam ows through the control value

into the separator manifold. This is where any solid water

particles fall out of the steam providing a good quality steam

for humidication. The Herrmidier Herricane CS Series is

designed for low steam velocities in the distribution tubes

resulting in very low noise levels. The distribution tubes are

also engineered to return any condensate to the header. The

stainless steel nozzles receive their steam from the middle

of the distribution tube where the driest steam is available.

Care must be taken to ensure that any spitting, caused by

heavy slugs of condensate, will not damage duct work or

materials positioned beneath an area steam humidier.

L o a d C al c u l a t io n G u i de

w w w. h e r r mi di f i e r- h v a c . co m

19

Page 20

L o a d C a l c u l a t i o n G u i d e

HERRMIDIFIER’S HERRICANE CS SERIES provides the

ultimate in performance and cost effectiveness in four distinct product families. Each Herricane CS series humidier

offers energy efciency with its standard non- jacketed design, noise minimization compliments of an exclusive nozzle

design and “Guaranteed Evaporative Distance” (G.E.D.) as

a result of its total system design. For complete details of the

Herricane product family, ask for the “Herricane CS Series

Application Guide.”

As we have seen, there are various types of humidication

equipment, each with various advantages and disadvantages according to application.

ATOMIZING equipment is the most energy efcient. It is

ideal for industrial plants, printing plants, bakeries, woodworking, etc. Also, since it adds evaporative cooling, it will

reduce cooling loads and is excellent for use in cold storage

or textile where humidication is needed year round. This

type equipment is also installed in the duct, as Herrmidicool.

HERRMIDIFIER’S HERRTRONIC electronic steam humidiers provide the features required for a variety of needs. The

Herrtronic AD adjusts to incoming water conditions, has diagnostics to aid troubleshooting, indicator lights to show operating conditions and is controlled by an on-off device. The

Herrtronic MD is microprocessor based. It has a user friendly

key pad and features diagnostics, networking up to 29 units,

P & I control and can proportion off a control or a limit input!

Both units are backed by a limited 2-year warranty and are

ETL and CSA listed. (See AD/Bro or MD/Bro.)

EVAPORATIVE equipment is both energy efcient and dust