Financial Conduct Authority PS21/3 User Manual

Building operational resilience:

Feedback to CP19/32 and final rules

Policy Statement

PS21/3

March 2021

PS21/3

Search

How to navigate this document

takes you to helpful abbreviations

returns you to the contents list

takes you to the previous page

takes you to the next page

prints document

email and share document

Financial Conduct Authority

Building operational resilience: Feedback to CP19/32 and nal rules

This relates to

Consultation Paper 19/32

which is available on our website at

www.fca.org.uk/publications

Email:

cp19-32@fca.org.uk

Contents

1 Summary 3

2 Important business services 9

3 Impact tolerances 16

4 Transitional arrangements 26

5 Mapping and scenario testing 28

6 Communications, governance and self-assessment

and responses to our cost benet analysis 38

Annex 1

List of non-condential respondents 48

Annex 2

Examples of relevant existing

FCA requirements 50

Annex 3

Abbreviations used in this paper 56

Sign up for our

news and publications alerts

See all our latest

press releases,

consultations

and speeches.

Appendix 1

Made rules (legal instrument)

2

PS21/3

Search

Chapter 1

Financial Conduct Authority

Building operational resilience: Feedback to CP19/32 and nal rules

1 Summary

Introduction

1.1 In December 2019, we consulted on proposed changes to how firms approach their

operational resilience. Our proposals were set out in CP19/32, ‘Building operational

resilience: impact tolerances for important business services and feedback to

DP18/04’.

1.2 These proposals were developed in partnership with the Bank of England – in its

capacity of supervising financial market infrastructures (FMIs) – and the Prudential

Regulation Authority (PRA) to improve the operational resilience of the UK financial

sector.

1.3 Ensuring the UK financial sector is operationally resilient is important for consumers,

firms and financial markets. It ensures firms and the sector can prevent, adapt,

respond to, recover and learn from operational disruptions. Operational disruptions

and the unavailability of important business services have the potential to cause widereaching harm to consumers and risk to market integrity, threaten the viability of firms

and cause instability in the financial system. The disruption caused by the coronavirus

(Covid-19) pandemic has shown why it is critically important for firms to understand

the services they provide and invest in their resilience.

1.4 This Policy Statement (PS) summarises the feedback we received to CP19/32 and our

response, and sets out final rules.

Who this applies to

1.5 These changes will affect banks, building societies, designated investment firms,

insurers, Recognised Investment Exchanges (RIEs), enhanced scope senior managers’

and certification regime (SM&CR) firms and entities authorised or registered under the

Payment Services Regulations 2017 (PSRs 2017) or the Electronic Money Regulations

2011 (EMRs 2011).

1.6 Firms not subject to these rules should continue to meet their existing obligations.

These are set out in Annex 4 of the CP and Annex 2 of this PS. Firms may also want to

consider the policy framework set out in this PS.

3

PS21/3

Search

Chapter 1

Financial Conduct Authority

Building operational resilience: Feedback to CP19/32 and nal rules

The wider context of this Policy Statement

Our consultation

1.7 Operational disruptions can have many causes including system failures, changes to

systems, people or processes. Some disruptions may be caused by matters outside

of a firm’s control, such as the pandemic, that lead to the unavailability of access to

infrastructure or key people.

1.8 In CP19/32 we set out changes designed to increase and enhance firms’ operational

resilience. We proposed to apply these changes proportionately to firms, reflecting

the impact on consumers and market integrity if their services are disrupted. We also

proposed an approach that is proportionate and flexible enough to accommodate the

different business models of firms.

1.9 Where we refer to consumers in this PS, we generally mean those that are the direct

consumers of the firm’s services or in other ways dependent upon them. This includes

both retail and wholesale market participants. We use the defined Glossary term

'client' in our rules, as amended in SYSC 15A.

1.10 Where we refer to market integrity in this PS, we mean the soundness, stability

or resilience of the UK financial system, and the orderly operation of the financial

markets.

1.11 Our proposed rules were not intended to conflict with or supersede existing

requirements on firms to manage operational risk or business continuity planning, but

rather to set new requirements that enhance firms’ resilience.

1.12 In Chapter 8 of the CP, we set out firms’ existing obligations in relation to third-party

service provision and outsourcing. We did not propose new requirements in this area,

but reminded firms of the importance of any existing requirements which apply to

them. Firms may find our information on the relationship between outsourcing and

existing requirements helpful.

Summary of feedback and our response

1.13 We received 73 responses to CP19/32. Most respondents supported our proposals.

In some cases, respondents asked us to clarify how the rules would apply. In a small

number of cases, respondents opposed our other proposals or suggested changes to

the proposed rules.

1.14 We have made changes to the policy position in response to feedback to provide firms

with more time and flexibility to meet mapping and scenario testing requirements.

More detail can be found in Chapters 4 and 5 of this PS.

1.15 In general, we have implemented our other proposals as consulted on, and have made

amendments to reflect the feedback received. Key themes of the feedback included:

• Respondents asked for more clarity around the level of granularity to which they’ll

be expected to go to comply with dierent elements of our proposals.

4

PS21/3

Search

Chapter 1

Financial Conduct Authority

Building operational resilience: Feedback to CP19/32 and nal rules

• Firms were keen to better understand how they should treat dierent consumer

groups, particularly vulnerable consumers.

• There was strong support for closer alignment between the PRA and FCA’s

approach, and with other regulators internationally.

• Some respondents commented on the extent of time and eort rms needed

to get ready for the new rules and to be consistently able to operate within their

impact tolerances. An impact tolerance reects the rst point at which a disruption

to an important business service would cause intolerable levels of harm to

consumers or risk to market integrity.

• Some respondents asked us to illustrate how rms, dierent to those example

rms included in the CP, might approach applying our proposals.

1.16 We have addressed this feedback by:

• clarifying how our rules t with the broader domestic and international regulatory

landscape and other FCA policy initiatives, such as the treatment of vulnerable

consumers

• setting out how we will further support rms in implementing the rules

• including more varied examples of how dierent types of rm might apply our

proposals, eg with the inclusion of new examples, as outlined below

1.17 Feedback and our responses are set out in more detail in Chapters 2 – 6.

Example firms

1.18 We use 3 fictional example firms throughout this PS to illustrate how some elements

of our rules might apply to different types of firms. We acknowledge that in practice

firms delivering business services would consider many other operational issues,

dependencies, nuances in business models and risk management considerations.

These examples are non-exhaustive and purely illustrative. Firms will need to consider

how the elements apply to their own circumstances.

Firm A

Firm A is an electronic money institution authorised under the EMRs 2011, with global

operations, servicing more than 8m retail customers and 200k business customers,

with core markets in the UK and European Economic Areas (EEA). It oers multiple

payment products including electronic money 'e-wallet accounts' and pre-paid cards.

The rm currently serves around 1m daily active users and processes around 3m

transactions daily – for users based in the UK, this encompasses 20% of daily active

users and 25% of daily transactions.

Firm B

Firm B is an enhanced scope SM&CR rm that provides insurance intermediary

services. It sells insurance products oered by insurers to retail customers to help

them meet their specic needs. In addition, certain insurers have outsourced claims

handling to Firm B and it holds claims money to be paid to customers under risk

transfer agreements. Firm B oers its services mainly via its online portal as well as via

agents in their contact centres.

5

PS21/3

Search

Chapter 1

Financial Conduct Authority

Building operational resilience: Feedback to CP19/32 and nal rules

Firm C

Firm C is an enhanced scope SM&CR rm that provides asset management services.

Firm C is at the centre of a complex ecosystem. On the customer side, the rm

is connected with retail and institutional investors as well as the advisers; wealth

managers; investment consultants; fund platforms; transfer agents; and messaging

systems through which these customers transact with the rm. On the operational

and markets side, the rm’s dependencies include: data and risk modelling tool

providers; order management and execution tools to create trade instructions;

custodians which safeguard client assets; depositaries which oversee them; fund

accountants which value the investment funds; brokers which execute instructions;

clearing houses which clear transactions; banks; transaction reporting specialists to

comply with its regulatory obligations; and markets.

Firm C is critically dependent on third parties for the delivery of its core services. Some

of these third parties are regulated rms. Examples include the rms providing middle

and back oce processing; custody; fund accounting; and transfer agency. Many,

though not all, of the technology tools and messaging systems relied on are from

unregulated rms. Outsourcing oversight is one of Firm C’s highest priorities.

Impact of coronavirus

1.19 We recognise that the coronavirus pandemic has had a significant impact on the

firms we regulate. The disruption caused has shown why it is critically important for

firms to understand the services they provide and invest in their resilience to protect

themselves, their consumers and the market from disruption. Some respondents

included in their feedback to the CP experiences of the pandemic and lessons learned

for the future. Key themes included:

a. The ‘interconnectedness’ of the nancial sector – respondents identied

coronavirus as an example of a ‘severe but plausible’ scenario. The pandemic showed

dependencies across rms/sectors and markets. It also highlighted the importance

of co-ordinating approaches to operational resilience at an international level due to

the global nature of the pandemic.

b. Third-party providers and risks – generally respondents had a positive experience

with the scalability and security of services received from cloud providers, but the

pandemic highlighted increasing dependence on third parties and outsourcing

arrangements. For example, some rms experienced challenges with oshore

third-party providers, particularly where providers were under lockdown in another

geographical location, which aected continuity of service to UK consumers.

c. People risks – mass remote working brought with it a range of challenges to

resilience, conduct, data protection and professional indemnity. Firms had to adapt

their systems, processes and controls to address emerging people risks.

1.20 The feedback we have received on the impact of the pandemic has reinforced the

importance of our policy proposals. Our proposal to require firms to map their

important business services, by identifying and documenting the people, processes,

technology, facilities and information that support them, provides a useful example of

this. By focusing on mapping, firms have a clear picture of the resources that enable an

important business service to function, and the impact if any of these are disrupted.

6

PS21/3

Search

Chapter 1

Financial Conduct Authority

Building operational resilience: Feedback to CP19/32 and nal rules

1.21 Staff play an essential role in delivering those services and firms need to understand

which staff are pivotal to delivering an important business service, with contingency

plans if those staff become incapacitated. We have found that firms that had mapped

their important business services ahead of the pandemic found themselves in a much

stronger position. For example, they could identify their key workers more quickly in

line with government guidance, and activate continuity plans for mass home working

and staff unavailability.

1.22 Overall, firms have been able to maintain continuity of service for consumers during

the pandemic and we’ve seen a good degree of resilience. This follows co-ordinated

response and action from industry, the Government and the FCA alongside the

PRA and the Bank of England. Other severe disruptions are likely to have different

characteristics and could be more firm-specific. Firms should progress the

implementation of our policy proposals to help them improve existing, and embed new,

standards of resilience.

Outcome we are seeking and measuring success

1.23 In implementing the policy, we want firms and the financial sector to better prevent,

adapt, respond to, recover and learn from operational disruptions. Through

improvements to firms’ operational resilience, we expect harm to consumers and risk

to market integrity caused through disruption to be minimised.

1.24 Through our ongoing supervisory work, we will assess the impact of the policy

to ensure its introduction is driving the right resilience changes within firms and

minimising harm. Longer term we would expect to see a positive change in the

number/type of incidents reported.

How it links to our objectives

1.25 Market integrity: Ongoing availability of business services reduces risk to market

integrity. Operational disruptions pose risks to the soundness, stability and resilience

of the UK financial system and the orderly operation of financial markets. Our final

policy will help build the resilience of the market to continue to function as effectively

as possible and quickly return to full operations following a disruption.

1.26 Effective competition: Resilient firms can promote effective competition. We

consider that consumers may be more likely to choose firms that are more resilient to

operational disruptions. This may drive firms to improve their operational resilience as

one way to compete for, and keep, customers.

1.27 Consumer protection: Ongoing availability of business services reduces consumer

harm. In identifying their important business services, setting impact tolerances and

restoring their important business services quickly after a disruption, firms can ensure

consistent provision of important business services and supply of new business to

consumers.

7

PS21/3

March 2021

Search

Chapter 1

Financial Conduct Authority

Building operational resilience: Feedback to CP19/32 and nal rules

Equality and diversity considerations

1.28 In the CP, we stated how we didn’t consider our proposals would adversely impact any

of the groups with protected characteristics under the Equality Act 2010. We set out

how our aim to strengthen the consideration given to vulnerable consumers during

operational disruptions would have a positive impact on some groups with protected

characteristics who also have characteristics of vulnerability.

1.29 Some respondents asked us to clarify how different elements of our proposals interact

with vulnerable consumers, specifically:

• how to correctly determine vulnerability of consumers given the transience of both

vulnerability and harm

• whether separate impact tolerances were needed for vulnerable consumers,

and how this should aect communications plans to eectively reach vulnerable

consumers

1.30 We have considered the equality and diversity issues that may arise from the final rules in

1.31 The legal instrument accompanying this PS contains final rules and guidance. Our rules

1.32 Firms must be able to remain within their impact tolerances as soon as reasonably

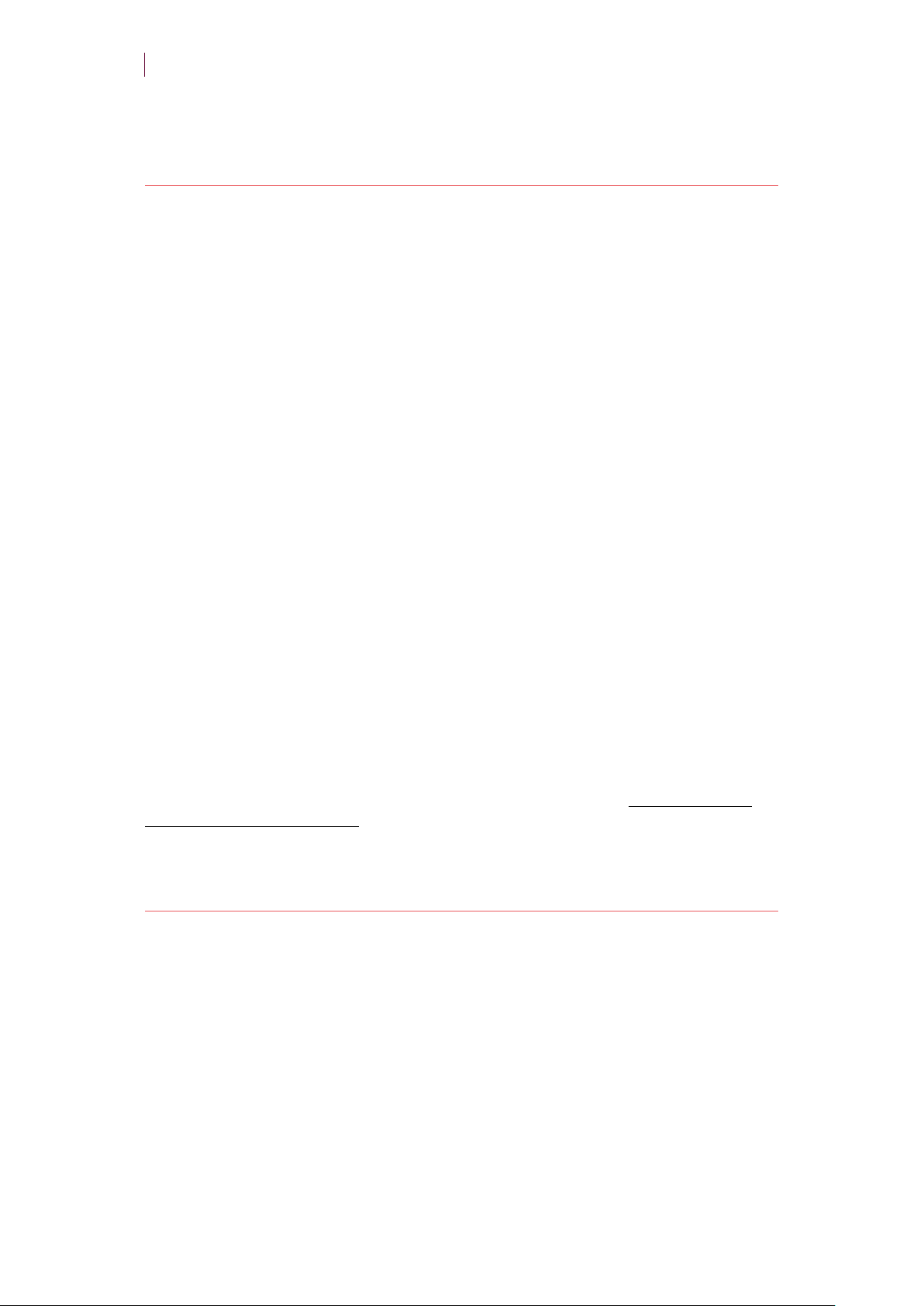

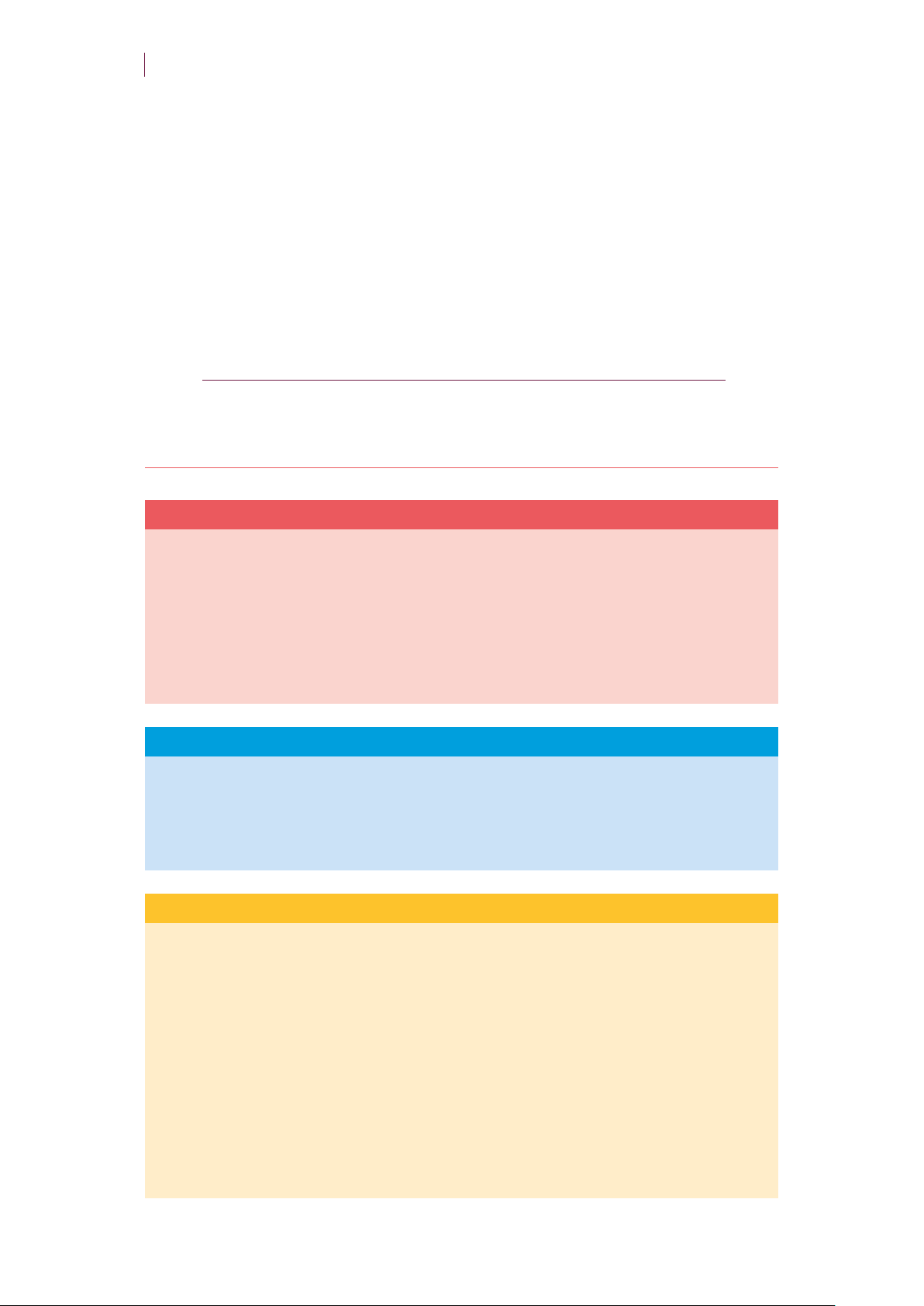

1.33 The implementation timeline is shown in Figure 1 below.

this PS. We remain mindful of the impact that resilience issues can have on some groups

with protected characteristics and vulnerable consumers, including the continuance of

access to key financial services. Further detail is included in Chapters 3 and 6.

Next steps

and guidance will come into force on 31 March 2022.

practicable, but no later than 3 years after the rules come into effect on 31 March

2022.

Figure 1

Firms should

PS21/3 published

1 year

implementation

period begins for

firms to

operationalise the

policy framework

March 2022

Final rules come

into force

Implementation

period ends

3 year transitional

period begins for

firms to remain

within their impact

tolerances as soon

as reasonably

practicable

March 2025

Transitional

period ends

ensure that

they are able

to operate

within their

impact

tolerances

8

PS21/3

Search

Chapter 2

Financial Conduct Authority

Building operational resilience: Feedback to CP19/32 and nal rules

2 Important business services

2.1 In this chapter, we summarise the feedback received on our proposals for firms to

identify their important business services and our responses.

CP proposals

2.2 We proposed that firms should identify their important business services. These are

services which, if disrupted, could potentially cause intolerable harm to the consumers

of the firm’s services or risk to market integrity.

2.3 We proposed firms should identify their important business services at least once a

year, or whenever there is a relevant change to their business or the market in which

they operate.

2.4 We also proposed that important business services should be clearly identifiable as

a separate service and not a collection of services. For example, accessing an online

mortgage account and telephone mortgage banking are 2 separate services, while the

provision of mortgages is a collection of services. The users of the important business

service would also need to be clearly identifiable.

2.5 Finally, we included a list of factors for firms to consider when identifying their

important business services. This was not an exhaustive list.

2.6 We asked 2 questions on important business services:

Q1: Doyouagreewithourproposalforrmstoidentifytheir

importantbusinessservices?Ifnot,pleaseexplainwhy.

Q2: Doyouagreewithourproposedguidanceonidentifying

importantbusinessservices?Arethereanyotherfactors

forrmstoconsider?

Feedback and responses

2.7 We received 62 responses to question 1 and 59 to question 2. While respondents were

broadly in support of our proposals, they suggested areas where we should further

clarify or refine the policy.

Processofidentifyingimportantbusinessservices

2.8 Some respondents commented on the process for identifying their important

business service. Two respondents suggested that firms identify all their business

services before going on to identify their important business services. Another

respondent asked us to confirm the point at which they should consider new

policyholders and when they would be at a greater risk of detriment than existing

customers.

9

PS21/3

Search

Chapter 2

Financial Conduct Authority

Building operational resilience: Feedback to CP19/32 and nal rules

2.9 Some respondents provided feedback around when an internal service may be

recognised as an important business service. This included payroll and treasury and

liquidity management services, which if disrupted could affect the resilience of the

business.

Our response

Identication of business services

We recognise that rms may nd it helpful to identify all their business

services before proceeding to identify which of these are ‘important’.

However, our rules only require rms to identify their important business

services for the purposes of operational resilience.

Capturing internal processes

While internal processes (such as payroll) are important for maintaining

a firm’s operational resilience, they do not in of themselves constitute

important business services. Instead, such processes which are

necessary to the provision of important business services and should

be captured by firms as part of their mapping exercises, where they

identify and document the people, processes, technology, facilities

and information that support their important business services.

Granularityandproportionality

2.10 Some respondents commented on the level of granularity they need to go to when

defining their important business services. Some respondents felt that firms should

have more flexibility in how, and to what granularity level, they define these services.

One such respondent asked us to confirm if they should undertake a full detailed endto-end analysis of a business service that is considered important or if they could

instead document the processes that are key/critical to providing the service and

those that are not and then focus on the key activities such as payment or settlement.

2.11 Additionally, 5 respondents requested more detail for smaller firms on how best to

identify their important business services. One respondent also felt that the PRA

and FCA consultations were inconsistent in how they presented granularity when

identifying important business services.

2.12 Some respondents suggested it was harder to identify consumer harm in the

wholesale sector, and highlighted that consumer harm is not relevant in global

wholesale markets where professional and eligible counterparties come together.

2.13 Two respondents commented on the proportionality of our important business

services proposals and, more specifically, how they should approach important

business services where only a small number of customers would be adversely

affected by disruption.

2.14 Two respondents asked if they would be able to review and update their important

business services every 2 years, if there were no significant changes to their business/

operations during that period. One other respondent asked us to clarify what

constitutes a significant/material change.

10

PS21/3

Search

Chapter 2

Financial Conduct Authority

Building operational resilience: Feedback to CP19/32 and nal rules

Our response

Granularity and proportionality when identifying important business

services

A common theme of the feedback was the level of granularity rms

should go to when identifying their important business services. Our

operational resilience framework is intended to provide rms with the

exibility to identify their important business services as appropriate in

the context of their business.

Given feedback received to both the CP and earlier DP, we consider

that rms are best placed to identify which of their services should be

classed as important business services in the context of their business

models. Firms can identify important business services in the way they

consider most appropriate and eective, but ultimately must comply

with our rules (SYSC 15A.2.1R–2R). We consider rms have the clearest

understanding of the service disruption which would cause intolerable

levels of harm to consumers or risk to market integrity.

We have included additional and varied rm examples in this PS, along

with Handbook guidance, to help rms in identifying their important

business services.

Denition of important business services

We have reviewed the drafting of our proposed Handbook Glossary term

‘important business service’ and have made a small change to clarify the

drafting to conrm that the denition only refers to ‘intolerable levels

of harm’ to consumers and not to ‘intolerable levels of risk’ to market

integrity. The change ensures our denition aligns with that of the Bank

and the PRA. The revised denition for an ‘important business service is:

means a service provided by a rm, or by another person on behalf of the

rm, to one or more clients of the rm which, if disrupted, could:

1. cause intolerable levels of harm to one or more of the rm’s clients; or

2. pose a risk to the soundness, stability or resilience of the UK nancial

system or the orderly operation of nancial markets.

Services where only a small number of consumers would be aected

by disruption

In identifying their important business services rms should consider

both the size and nature of the consumer base. It is reasonable to

expect that in some cases only a small number of customers would be

aected by disruption but having considered all other factors the rm still

considers the service to be important. Firms are encouraged to identify

their important business services holistically, considering them in the

broader context of size, complexity and focus on achieving operationally

resilient outcomes.

Reviewing important business services

Firms should, from 31 March 2021, begin identifying their important

business services. Firms will need to have completed this exercise before

the rules take eect, on 31 March 2022. After 31 March 2022, rms will

11

PS21/3

Search

Chapter 2

Financial Conduct Authority

Building operational resilience: Feedback to CP19/32 and nal rules

then need to review their important business services at least once

per year, or whenever there is a material change to their business or

the market in which they operate. We consider it necessary for rms to

review their important business services at least once per year to ensure

that no emerging vulnerabilities are overlooked. Firms do not need to

undertake the whole exercise once a year. We are only requiring that they

review their existing identication against changes to their business or

operating market over the course of the year. Where there have been no

material changes, we would expect this to be straightforward.

Material changes

We consider a ‘material change’, which would require a rm to review their

important business services, to include:

• the rm beginning to carry out a new activity/ceasing to provide an

existing activity, or

• the rm outsourcing a new/existing service to a third-party service

provider, or

• changes to an existing service in terms of scale or potential impact

(considering the factors set out in paragraph 4.21 of the CP, number

of customers or substitutability of the service, for example)

Firms may wish to review other changes, that are not considered

material, in line with the review of their self-assessment

documentation.

Centralsharedservicesforgroupsandcollectionsofservices

2.15 Respondents were broadly supportive of our proposal not to publish a prescriptive

taxonomy for firms to use when identifying their important business services. But

several respondents asked us to clarify how group shared services should be viewed in

terms of identifying important business services.

2.16 Some respondents asked us to clarify the distinction between a separate service and a

collection of services.

2.17 Several respondents asked us to further clarify the taxonomy between collection of

services, business service and process, and how they interact with critical functions

and other existing taxonomies.

Our response

Central shared services

We have considered the feedback about central shared services within

groups being dened as important business services. We have identied

the following examples of central shared services:

• architecture and underlying technology provided centrally

• operational processes, such as transactions booking or risk

management

• audit and other 2nd line functions

• IT services

12

PS21/3

Search

Chapter 2

Financial Conduct Authority

Building operational resilience: Feedback to CP19/32 and nal rules

We consider that such services are unlikely to constitute important

business services. These enable the provision of an important

business service and should be identified by firms when they carry out

their mapping exercises. Services can only be identified as important

business services where they are provided by a firm, or by another

person on behalf of the firm, to one or more consumers.

2.18 For further information on important business services and critical functions please

see the PRA’s Policy Statement.

Interactionwithexisting/proposedframeworks

2.19 Some respondents commented on the interaction between FCA-defined terms, such

as the Glossary definition of ‘important business service’ and other definitions such as

‘critical operations’ and ‘critical business service’ featured in the consultation published

by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) and the European Banking

Authority (EBA) Guidelines. The respondents called for global regulatory alignment

through a common lexicon of terms. A respondent also commented on the differences

between the FCA’s definition of ‘important business service’ and that of the PRA.

2.20 Two respondents asked us to consider the link between our important business

service proposals and existing related legislation, such as the Payment Services

Directive 2 (PSD 2) and Operational Continuity in Resolution (OCIR).

2.21 We proposed that users of the service should be identifiable so that the impacts

of disruption (through process, cyber security or technology failures) are clear.

Two respondents queried how this interacts with existing General Data Protection

Regulation (GDPR) and Data Protection Act (DPA) requirements. More specifically, 1

respondent asked whether regulated entities within scope were required to contact

individuals affected by service disruption or whether it was acceptable to have systems

in place to notify such individuals automatically (eg through email notifications). This

respondent added that it may be difficult to access information with which to contact

individuals given this may be encrypted.

Our response

Links to existing requirements

As with the CP, we have considered in detail the interaction of our nal

rules with existing requirements and recent regulatory developments (see

Annex 2). This includes the recent consultations published by the BCBS

and the European Commission (EC) and international approaches (CPMIIOSCO guidance; G7, FSB and IOSCO membership), with the objective

to achieve greater consistency in global standards/mitigate the risk of

divergence, through work in key global Standard Setting Bodies (SSBs).

A key driver for us in introducing a high-level, principles-based framework

is to provide sucient exibility for rms to take account of all aspects

of their approach to resilience. This includes those arising from other

regulatory requirements through the lens of providing important

business services to customers. We believe this delivers on our

objectives in the context of the rms we regulate in the UK market.

13

PS21/3

Search

Chapter 2

Financial Conduct Authority

Building operational resilience: Feedback to CP19/32 and nal rules

‘Identiable’ service users

Where we proposed that service users be ‘identifiable’, we intended

that firms should be able to recognise which of their consumer base

use a certain important business service. This does not require the

firm to identify individual consumers by name, or change existing

requirements for the handling of customer data. The final rules

proceed with that intention.

Scopeoftheproposals

2.22 One respondent asked that we clarify the services to which a firm authorised or

registered under the PSRs 17 or EMRs 2011 ('payments firms') would need to apply

the policy. More specifically, the respondent felt a change was needed to clarify our

expectations for firms who would be outside the scope of the policy, but for their

PSRs 2017 or EMRs 2011 permission. The respondent stated that only those services

operated under the PSRs 2017 should be in scope for consideration as important

business services and subject to the requirements. It also asked us to clarify whether

certain other regulated activities should or should not be identified as important

services in the context of the proposals and the provider’s SM&CR status.

2.23 One respondent considered that the proposals could go further in establishing service

failure criteria. The respondent stated that it is crucial for firms to understand where a

service is degraded to the point of failure (failover) but still operating. The respondent

suggested that, given the interconnectedness between critical services, it is not just

outage, but also service degradation thresholds, which are relevant.

2.24 Another respondent suggested that we may want to include products, in addition

to services, as important business services. The respondent suggested that we

could provide further guidance on services that are essentially comprised of multiple

products and whether these products constitute important business services.

Our response

Payments and e-money rms in scope

We have considered the feedback in relation to payments and e-money

rms and the services in scope of the proposals. Our proposals apply to

payments rms, to all rms and entities authorised or registered under

the PSRs 2017 or EMRs 2011. However, there are some payments rms

which also have permissions to carry on FSMA regulated activities which

would not be in scope of this policy based on these activities considered

on a standalone basis. Where this is the case, payments rms only have

to apply our operational resilience proposals to their payments and/or

e-money activities.

To clarify this, we have amended SYSC 15A.1 (Application).

Service failure criteria

We acknowledge the feedback asking us to develop criteria in respect

of service failure. We agree that there will be circumstances where a

service is degraded but still operating. Chapter 3 on impact tolerances

addresses this feedback in more detail.

14

PS21/3

Search

Chapter 2

Financial Conduct Authority

Building operational resilience: Feedback to CP19/32 and nal rules

Products

We consider it unnecessary to bring products into scope of the

proposals. Most products are supported by, and offered because of,

important business services. For example, a fixed-rate mortgage

product provided by a retail bank would likely be underpinned by one

or multiple important business services (customer access to online

mortgage calculators and telephone provision of mortgage advice,

for example). If the supporting service is captured as an important

business service then there is no additional merit in separately

identifying relevant products.

How our example rms might identify important business services

Firm A

Firm A identies the provision of its multi-currency e-wallet account from which users

can initiate electronic payment transactions as 1 of its important business services for

the purposes of operational resilience. Users access their e-wallet account through

the rm’s proprietary Apple and Android mobile apps.Access is via App only, there is

no web-browser option.

Firm A considers that loss of access to the e-wallet accounts can cause signicant

harm to its users, many of which are consumers, as that is the primary channel

through which they manage payment transactions and interact with the rm.

Firm B

Firm B identies claims handling for its customers as one of its important business

services for the purposes of operational resilience.

Firm B considers that disruption to the claims handling process could cause intolerable

harm to consumers. For example, if consumers are unable to notify Firm B of their

claim, submit a claim and/or and receive a claims payout/benet under the policy.

Firm C

Firm C identiesgenerating orders to meet client subscription and redemption

requests as an important business service. The rm uses an order management

system(OMS)to provide the service.The OMS is central to the rm’s portfolio

management activity as it is essential for generating orders and to adjust the portfolio

so that it delivers the objectives of the mandates and funds for which the rm is

responsible. Disruptionto the OMS could cause operational challenges within hours.

These may aect both the rm’s customers and, potentially, the markets in which the

rm operates.

Customer harm could include investors being unable to buy or redeem units in funds

or their investments suering from lower performance because of fund transactions

being delayed or incorrect. Outage has the potential to lead to market harm to the

extent that some of a rm’s market abuse controls are embedded in the system. Both

the rm’s reputation and customer condence could also suer.

15

PS21/3

Search

Chapter 3

Financial Conduct Authority

Building operational resilience: Feedback to CP19/32 and nal rules

3 Impact tolerances

3.1 In this chapter, we summarise the feedback received on our proposals for firms to set

impact tolerances for each important business service and our response.

CP proposals

3.2 We proposed firms should set their impact tolerances at the first point at which a

disruption to an important business service would cause intolerable levels of harm

to consumers or risk to market integrity. We provided further guidance on relevant

considerations to help firms in making this judgement. We also proposed firms should

set and review their impact tolerances at least once per year or if there is a relevant

change to the firm’s business or the market in which it operates.

3.3 We proposed that firms should use metrics, including a mandatory metric of time/

duration, to measure their impact tolerances.

3.4 The FCA and PRA set out proposals for how dual-regulated firms should approach

impact tolerances. We proposed firms would need to set 1 impact tolerance at the

first point at which there is an intolerable level of harm to consumers or risk to market

integrity for our purposes. And under the PRA’s rules, another separate tolerance at

the first point at which financial stability is put at risk or a firm’s safety and soundness

or, in the case of insurers, where policyholder protection is affected.

3.5 In the CP, we asked 3 questions on impact tolerances:

Q3: Doyouagreewithourproposalsforrmstosetimpact

tolerances?Ifnot,pleaseexplainwhy.

Q4: Doyouagreethatduration(time)shouldalwaysbeusedas

1ofthemetricsinsettingimpacttolerances?Arethereany

othermetricsthatshouldalsobemandatory?

Q5: Doyouagreewithourproposalfordual-regulatedrmsto

setupto2impacttolerancesandsolo-regulatedrmsto

set1impacttoleranceperimportantbusinessservice?

Feedback and responses

3.6 We received 64 responses to question 3, 53 responses to question 4 and 52 responses

to question 5. Respondents were broadly in support of our proposals but asked for

clarification and refinement in some areas. Any consequential amendments to the

policy are set out in our response.

Implementationchallenges

3.7 Some respondents suggested how we could clarify certain aspects of our proposals to

make implementation more straightforward. Respondents suggested we could:

16

PS21/3

Search

Chapter 3

Financial Conduct Authority

Building operational resilience: Feedback to CP19/32 and nal rules

• benchmark tolerances across the sector and provide more sector-specic support

• align the factors for consideration across those ‘important business services’ and

‘impact tolerances’

• review and clarify the dierences between our proposals to set impact tolerances

and Business Impact Analysis

• clarify what we mean by ‘intolerable harm’

3.8 In addition, 1 respondent considered that setting impact tolerances at the point at

which ‘intolerable harm’ would be caused to consumers/market integrity was too late.

The respondent considered that impact tolerances should be set before this point is

reached to enable preventative measures to be taken.

Our response

As with other areas of the policy, we consider rms are best placed to

set their impact tolerances at the appropriate level. Firms should use the

considerations we have provided to help inform their judgements when

setting impact tolerances. This exible and proportionate approach is

important given the wide range of rms from dierent sectors and with

varying customer bases which are in scope. So we are proceeding with

our proposals largely as consulted on, with some minor changes and

clarications based on the feedback received. These are set out below.

We consider that requiring rms to set their impact tolerances at the

point at which disruption would cause intolerable harm to consumers or

risk to market integrity remains appropriate. Setting impact tolerances

at this point does not hinder rms from taking appropriate steps to

prevent disruption. Moreover, it aims to ensure that rms build sucient

resilience before they reach their impact tolerance. We expect that rms

manage their business to ensure they can operate within tolerance at

all times including during severe but plausible scenarios. Firms should

still be mindful of existing requirements which focus on preventative

measures.

Intolerable harm

We didn’t propose to dene ‘intolerable harm’ as we consider what this

constitutes will vary from rm-to-rm and across sectors. To identify

intolerable harm, rms should have regard to various factors, some of

which we set out in the CP. These were:

• the number and types (such as vulnerability) of consumers adversely

aected, and nature of impact

• nancial loss to consumers

• nancial loss to the rm where this could harm the rm’s consumers,

the soundness, stability or resilience of the UK nancial system or the

orderly operation of the nancial markets

• the level of reputational damage where this could harm the rm’s

consumers, the soundness, stability or resilience of the UK nancial

system or the orderly operation of the nancial markets

• impacts to market or consumer condence

• the spread of risks to their other business services, rms or the UK

nancial system

17

PS21/3

Search

Chapter 3

Financial Conduct Authority

Building operational resilience: Feedback to CP19/32 and nal rules

• loss of functionality or access for consumers

• any loss of condentiality, integrity or availability of data

Additionally, we would advise firms that intolerable harm constitutes

harm from which consumers cannot easily recover. This could

be, for example, where a firm is unable to put a client back into a

correct financial position, post-disruption, or where there have been

serious non-financial impacts that cannot be effectively remedied.

Intolerable harm is much more severe than inconvenience or harm.

For both ‘harm’ and ‘inconvenience’ we would expect firms to be able

to remediate any disruption so that no ill effects would be felt in the

medium-/long-term by clients/markets.

Approachtovulnerableconsumers

3.9 Five respondents had comments on how our proposals for impact tolerances interact

with the needs of vulnerable consumers. More specifically, respondents asked us to

clarify how impact tolerances should be set given consumer vulnerability and harm can

be transient, and whether specific metrics could be used for vulnerable consumer subgroups.

Our response

Vulnerable consumers

We have carefully considered how our proposal for rms to set impact

tolerances interacts with the needs of, and considerations for, vulnerable

consumers. Firms should consult our nalised guidance on the fair

treatment of vulnerable customers.

More specically for vulnerable consumers and impact tolerances,

in the CP we emphasised that when identifying important business

services, rms should consider their vulnerable consumers (see SYSC

15A.2.4G(1)). The concepts of rst identifying important business

services and then setting impact tolerances for each of these are

inextricably linked. Consideration of the needs of vulnerable consumers

is central to a rm’s setting of an impact tolerance, and rms should

consider these groups when considering how much disruption could be

tolerated. Firms should also construct communications and alternative

mechanisms to minimise harms arising for vulnerable consumers in the

event of disruptions.

Given this, we do not consider it necessary for firms to set specific

impact tolerances for vulnerable consumers as these should already

be considered through the process of identifying important business

services and setting impact tolerances. We have, however, amended

SYSC 15A .2.7G to also make express reference to ‘vulnerable

consumers’ in the guidance on factors to consider when setting

impact tolerances.

18

PS21/3

Search

Chapter 3

Financial Conduct Authority

Building operational resilience: Feedback to CP19/32 and nal rules

Groupapproachtoimpacttolerances

3.10 One respondent asked us to clarify how competing impact tolerances set at group

level and across different legal entities should be treated.

Our response

Impact tolerances at group and entity level

In situations where an entity sets an impact tolerance at a lower level

than that set by the group, the group’s Board should consider and

approve that the entity can, and it is appropriate for it to, work towards

that lower tolerance. The Board should also ensure that the entity

has appropriate resources to meet its identified tolerance. More

information can be found in the PRA’s final policy documents.

Circumstancesoutsidearm’scontrol

3.11 Four respondents asked us to clarify how we view circumstances outside of a firm’s

control in the context of remaining within impact tolerances. Two other respondents

asked for further information on the circumstances in which it would be acceptable for

a firm to deliberately not remain within its impact tolerances (for example, if doing so

would further spread a computer virus).

Our response

Scenario testing as a tool to remain within tolerances

Our policy covers disruptions inside and outside of a rm’s control. To

prepare for such disruptions, rms need to test their impact tolerances

in a range of severe but plausible scenarios. This approach will give rms

a clear idea when they initially test their impact tolerances of where such

unexpected events may mean they cannot remain within tolerance.

In the CP (paragraph 2.4), we gave examples of disruptions outside of a

rm’s control (for example, cyber-attacks and wider telecommunications/

power failures). We remind rms that operational resilience assumes

that disruption is inevitable. While some situations cannot be predicted,

and so will be outside of rms’ severe but plausible testing scenarios, we

encourage rms to approach such situations pragmatically.

If a rm has put in place procedures to improve its operational resilience

and tested in a variety of severe but plausible scenarios it should be

able to eectively translate that eort in the event of an unpredictable

disruption. Firms should view testing in a range of severe but plausible

scenarios as an eective planning tool to ensure services can remain

within tolerance. However, if despite extensive scenario testing a rm

nds itself not able to remain within impact tolerance for any reason, it

should report the issue to the FCA in line with SYSC 15A.2.11G.

Circumstances where remaining within tolerance could cause further

detriment

We know there may be some instances where a rm cannot remain

within impact tolerances because doing so would cause further

19

PS21/3

Search

Chapter 3

Financial Conduct Authority

Building operational resilience: Feedback to CP19/32 and nal rules

detriment. For example, where resuming service could spread a

computer virus. If a rm resumes a compromised service in such a case

this does not constitute remaining within tolerance and neither does it

show increased resilience, which is a key outcome we are seeking.

In line with the above, firms should consider such circumstances in

their testing plans and report any issue with remaining in tolerance to

the FCA in line with SYSC 15A .2.11G. There may be some occasions

where a firm wishes to resume a degraded service. This is acceptable

so long as the firm has assessed whether (a) the degraded service can

safely resume without causing further detriment and (b) the benefits

of resuming a degraded service outweigh the negatives of keeping the

service unavailable until the issues have been remediated/the service

is able to be fully restored to pre-disruption levels.

Multipleservicedisruptions

3.12 Some respondents asked us to clarify how firms should approach impact tolerances

in the event of multiple disruptions to an important business service over a short time

period and when multiple important business services are disrupted simultaneously.

The respondents considered that such disruption could have a greater, and often

faster, impact in aggregate and cause harm after a shorter duration.

Our response

Multiple disruptions to an important business service

In the CP, we focused on the disruption of single important business service.

We recognise there will be some occasions where a service could be

aected by multiple disruptions over a short period of time. However,

rms should continue to set their impact tolerances with reference to a

single disruption rather than an aggregation of a number of disruptions.

This is important for rms in maintaining an impact tolerance as an

accurate metric for maximum tolerable disruption.

Aggregate harm when multiple business services are disrupted

When identifying their important business services and carrying out the

mapping exercise (see Chapter 5 for more detail), rms should consider

the lack of substitutability of a service and recognise where multiple

business services rely on the same underlying system. In these cases,

for substitute services which rely on the same systems, processes or

people, rms should not assume, as part of their testing plans, that

these services won’t be aected in the event of disruption.

We agree that the simultaneous disruption of multiple important

business services could mean that aggregate harm is felt more quickly

and severely (for example, if telephone banking customer authentication

went down at the same time as online banking and access to cash). We

consider there are 2 situations in which such disruption is likely:

• Where multiple important business services rely on 1 common

operational asset (such as key people or process), the disruption

20

PS21/3

Search

Chapter 3

Financial Conduct Authority

Building operational resilience: Feedback to CP19/32 and nal rules

of which could cause disruption to all reliant important business

services. Such reliance would be captured in a rm’s mapping exercise

and be factored into testing plans.

• Where multiple important business services could be disrupted

simultaneously due to an external factor directly aecting the service.

For example, this could be due to a cyber-attack which hits a wide

range of operational assets.

Firms should take steps to stay within set impact tolerances in both

situations. Firms do not need to set separate tolerances to address

the disruption of multiple services but should consider when setting

their tolerances how aggregate impact may build in these situations

and in turn, how aggregate impact could affect intolerable harm.

Cross-regulatoryalignment

3.13 Four respondents commented on the differences in the FCA and PRA’s respective

definitions of ‘impact tolerance’.

Our response

Amendments to our ‘impact tolerance’ denition

We have removed the reference to ‘intolerable levels of risk’ to

instead refer to ‘risk’. This aligns with the PRA’s proposed approach.

The PRA has also made a small amendment to its definition to refer

to ‘maximum tolerable level of disruption’ (as opposed to ‘maximum

acceptable level of disruption’) to mirror the drafting in our definition.

We consider any other differences in the definitions necessary to

accurately reflect our respective statutory objectives.

Outsourcedservicesandimpacttolerances

3.14 Five respondents asked for further guidance on how impact tolerances should be

managed by firms outsourcing important business services to third parties.

Our response

Thirdpartiesprovidingimportantbusinessservices

When a firm is using a third-party provider in the provision of important

business services, it should work effectively with that provider to set

and remain within impact tolerances. Ultimately, the requirements

to set and remain within impact tolerances remain the responsibility

of the firm, regardless of whether it uses external parties for the

provision of important business services.

Measuringimpacttolerances

3.15 Most respondents agreed that time/duration should always be used as a mandatory

metric when measuring impact tolerances. Respondents also appreciated the

flexibility we provided in allowing firms to use other metrics in addition to time to

measure impact tolerances.

21

PS21/3

Search

Chapter 3

Financial Conduct Authority

Building operational resilience: Feedback to CP19/32 and nal rules

3.16 A small number of respondents considered that firms should have greater autonomy

when it comes to metrics, preferring that time/duration not be mandated. Some

respondents suggested metrics firms may wish to use. These included:

• cost

• scale

• key business process

• potential value of market impact

• materiality (ie business/customer impact)

• volumes (eg data volume, transaction/account volume)

• type of transaction

• number of customers aected, and the nature of the consumer base

3.17 We also received some comments on how firms could use more than one metric to

most effectively measure impact tolerance. One respondent considered that there

may be occasions where time may not be the most effective metric.

Our response

Measuring impact tolerances

Based on the feedback received, we are proceeding as consulted to

require that rms use time/duration as a mandatory metric to measure

their impact tolerances. Using time/duration as a mandatory metric

willensure that rms plan for time-critical threats where there could

be limited time to react to disruption before intolerable harm or risk to

market integrity is caused. Additionally, the use of time as a common

metric provides a clearstandard, andenables comparison between

rms.

To clarify, the time-based metric can be exible and used in conjunction

with other metrics. The impact tolerance should specify that an

important business service should not be disrupted beyond a certain

period of or point in time. As an example, this could be a number of

hours/days or a point in time, such as the end of the day, in conjunction

with, for example, a certain level of customer complaints.

Using a combination of metrics may be more appropriate for some

important business services, eg where a service could run at a

percentage capacity of its full capability for a certain period (time) before

causing intolerable harm to consumers or risk to market integrity.

Examples of other metrics

We agree with respondents’ suggestions, set out at paragraph 3.16 above,

as to other metrics that may be used in addition to a time/duration-based

metric. Firms are best placed to determine which metrics best measure

impact tolerances for their important business services.

Dual-regulatedrms’approachtoimpacttolerances

3.18 Most respondents agreed with our proposal for dual-regulated firms to set and

manage to ‘up to’ 2 impact tolerances (1 for each regulator’s objectives).

22

PS21/3

Search

Chapter 3

Financial Conduct Authority

Building operational resilience: Feedback to CP19/32 and nal rules

3.19 However, 2 respondents felt that mandating a set number of tolerances was too

prescriptive. These respondents considered that firms should have flexibility to set

as many impact tolerances as they wish. Four respondents also asked us to clarify

our expectations around how dual-regulated firms should manage, in practice, 2

tolerances when they could vary in line with each regulator’s objectives.

3.20 Some respondents also had comments on how smaller dual-regulated firms may

find it more difficult to implement our proposals. More specifically, one respondent

emphasised that, for smaller dual-regulated firms, important business services may be

less likely to have a material impact on financial markets. Consequently, such firms may

find it harder to differentiate between the respective regulatory (FCA/PRA) tolerances.

Our response

Up to 2 impact tolerances for dual-regulated rms

For dual-regulated rms, we maintain the position that these rms

should set up to 2 impact tolerances. This is to ensure that rms

consider their impact tolerances in line with the statutory objectives of

each authority. Taking this focused approach ensures better outcomes

for consumers and market integrity. Our expectation is that, while rms

need to set tolerances for each important business service by reference

to that authority’s operational resilience rules, such rms will eectively

manage the tolerances together.

Firms may set their separate impact tolerances at the same point if they

deem it suitable for the purposes of each authority but will need to be

able to justify this decision if challenged.

We understand that in practice dual-regulated rms may concentrate

their eorts in ensuring they can remain within the more stringent

tolerance. So it will be acceptable for a rm to show it can remain within

the more stringent tolerance if it can demonstrate:

• how it has considered each of the FCA’s and PRA’s objectives when

setting impact tolerances

• how its recovery and response arrangements are also appropriate for

the longer tolerance (ie recovery and response arrangements must

be viable for both shorter and longer time periods)

• that scenario testing has been performed with the longer tolerance

in mind as a short tolerance might constrain the range of severe but

plausible events a rm might consider

While we are requiring dual-regulated rms to set up to 2 clearly

stated impact tolerances, if they nd it benecial to set additional sub-

tolerances they can do so. Both the FCA and PRA will work collaboratively

to ensure we supervise against tolerances eciently.

23

Loading...

Loading...