ENDEAVOUR E40, 40 Owner's Manual

ENDEAVOUR 40 OWNERS MANUAL

ENDEAVOUR 40 OWNERS MANUAL

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. List of Figures

3. Construction

3.1 Hull

3.2 Deck

3.3 Deck/Hull Joint

3.4 Rudder and Steering

3.5 Ballast

3.6 Interior Construction

4. Spars and Rigging

4.1 Spars

4.2 Standing Rigging, Running Rigging, Chainplates

4.3 Static Tuning (at the Dock)

4.4 Dynamic Tuning (under Sail)

5. Fuel System

5.1 Fuel Tank

5.2 Fueling

6. Engine and Transmission of Power

6.1 Engine

6.2 Transmissions

6.3 Propeller Shaft and Stuffing Box

6.4 Shaft Alignment

6.5 Propellers

6.6 Removal of Propellers

6.7 Installation of Propellers

6.8 Propeller Alignment

6.9 Exhaust System

7. Engine Controls

7.1 Description

7.2 Starting the Engine

7.3 Stopping the Engine

8. Electrical System

8.1 General

8.2 Direct Current (D.C.) System

8.3 Battery Maintenance

8.4 Alternating Current (A.C.) System

8.5 A.C. Shore Power

8.6 A.C. Ship’s Power (Auxiliary Generator)

8.7 Generator Diesel

2

9. Plumbing System

9.1 Head and Holding Tank

9.2 Galley Stove Operation

10. Maintenance

10.1 Gelcoat Surfaces

10.2 Ports and Hatches

10.3 Teak

10.4 Hull Bottom

10.5 Standing Rigging

10.6 Running Rigging

10.7 Lifelines, Pulpits, Stanchions

10.8 Winches and Block

10.9 Engine

10.10 Power Train

10.11 Electrical Maintenance

10.12 Upholstery

10.13 Steering

11. Fitting Out

11.1 Prior to Launching

11.2 After Launching

11.3 Stepping the Spar

12. Laying Up for Winter Storage

12.1 Hauling (Slings)

12.2 Cradle Support

12.3 After Haul Out

12.4 Fresh Water. System

12.5 Head and Holding Tank

12.6 Batteries

2. LIST OF FIGURES

Figure Title Page

1 Deck-to-Hull Joint 4

1A Topside Deck Layout 4

1B Interior Deck Layout 5

2 Chainplate Installation 6

3 Reefing System 8

4 Deck Wiring 15

5 Head System Description 15

6 Plumbing System Description 16

7 LPG System 16

8 Alcohol Stove System 17

9 Lift Strap Locations 21

10 AC/DC Electrical Panel Wiring Diagram (no generator) not avail.

11 DC Panel Wiring Diagram (generator option) not avail.

12 AC Panel Wiring Diagram (generator option) not avail.

13 Cockpit Instrument Panel Wiring 12

3

3. CONSTRUCTION

3.1) Hull:

The hull is molded as a single unit of a combination of polyester resin and fiberglass woven roving and

multi-directional chopped strand fiber (MCSF). The keel is molded integrally with the hull and all

ballast is contained inside. The exterior finish is a pigmented gelcoat molded onto the fiberglass. The

boot and sheer stripe are also gelcoat molded permanently into the hull.

3.2) Deck:

The deck and cockpit, like the hull, are molded as a single unit of a combination of polyester resin and

fiberglass woven roving and MCSF. Plywood coring is incorporated between layers of fiberglass in the

cabin top, deck, seat, and cockpit sole areas to give additional stiffness. The non-skid finish is molded

into the deck. All exterior deck surfaces are a pigmented gelcoat molded onto the fiberglass.

3.3) Deck/Hull Joint:

The joint between the hull and deck is one of the

most important assembly steps in the construction of

a yacht. The method used by Endeavour Yacht is

simple, strong, and reliable. Figure #1 illustrates

details of this assembly.

During assembly, the top of the integral hull flange is

liberally coated with a combination adhesive/sealant.

The deck is then lowered onto the hull and fastened

in place with stainless steel bolts. When the bolts are

tightened, the excess compound is forced into all

crevices and out the sides. The teak cap is then

installed, bedded in a heavy layer of the same

compound and secured in place, doubly ensuring

water tightness.

3.4) Rudder and Steering:

The rudder is molded as a single piece of solid high

density foam with a protective skin of fiberglass and

a gelcoat finish. The foam material is of high

strength structural grade and has exceptional

toughness. The rudder post, molded integrally inside

4

rudder, is solid stainless steel, which is welded to a steel blade in the interior of the rudder.

Where the rudder post passes through the hull, water tightness is ensured by means of a stuffing box. It

is recommended that the packing inside the stuffing box be replaced annually to ensure continued

water tightness. Packing of the proper size is available from most marine hardware stores. The

Endeavour 40 requires 3/8” square packing. Cut packing in individual rings rather than a long spiral to

prevent binding on the rotating shaft.

The pedestal steering system installed on your yacht operates with stainless steel cables rotating a

quadrant bolted and keyed to the rudder post. The cables run through a conduit attached to a massive

steel support frame at the rudder and the motor mount then to the pedestal where they are shackled to a

stainless steel chain running over a sprocket on the steering sheel shaft. Normal maintenance should

only require occasional oiling of all the moving parts with teflon grease, inspection of cables for wear

and proper tension, and a check of all bolted connections for tightness.

3.5) Ballast:

All ballast is internally mounted inside the keel, which is molded integrally with the hull. Cast pieces

of lead are placed in the hull, encapsulated in a polyester bonding resin, and then covered with a layer

of woven roving to form a fiberglass cap. When finished, the ballast becomes a structural part of the

hull.

3.6) Interior Construction:

The interior of your Endeavour 40 is built up of wood. First, a framework of floor timbers is

constructed and placed in the bilge and heavily bonded in place with woven roving. A plywood sole is

glued and screwed on top of these floor timbers and bonded to the hull all around its periphery with

woven roving.

All timbers and plywood are saturated with polyester resin before assembly to seal all exposed wood.

Next, the entire sole is covered with teak parquet flooring, bonded in place with a waterproof adhesive.

All bulkheads are bonded to the hull with two layers of woven roving on both sides.

5

4. SPARS AND RIGGING

4.1) Spars:

All spars (masts, booms, and spreaders) are extruded aluminum 6061-T6 alloy with a protective

coating on all external surfaces. The main mast of the E-43 is stepped through the cabin roof onto the

keel. The mizzen mast is stepped on deck with a supporting post or structure immediately under the

mast.

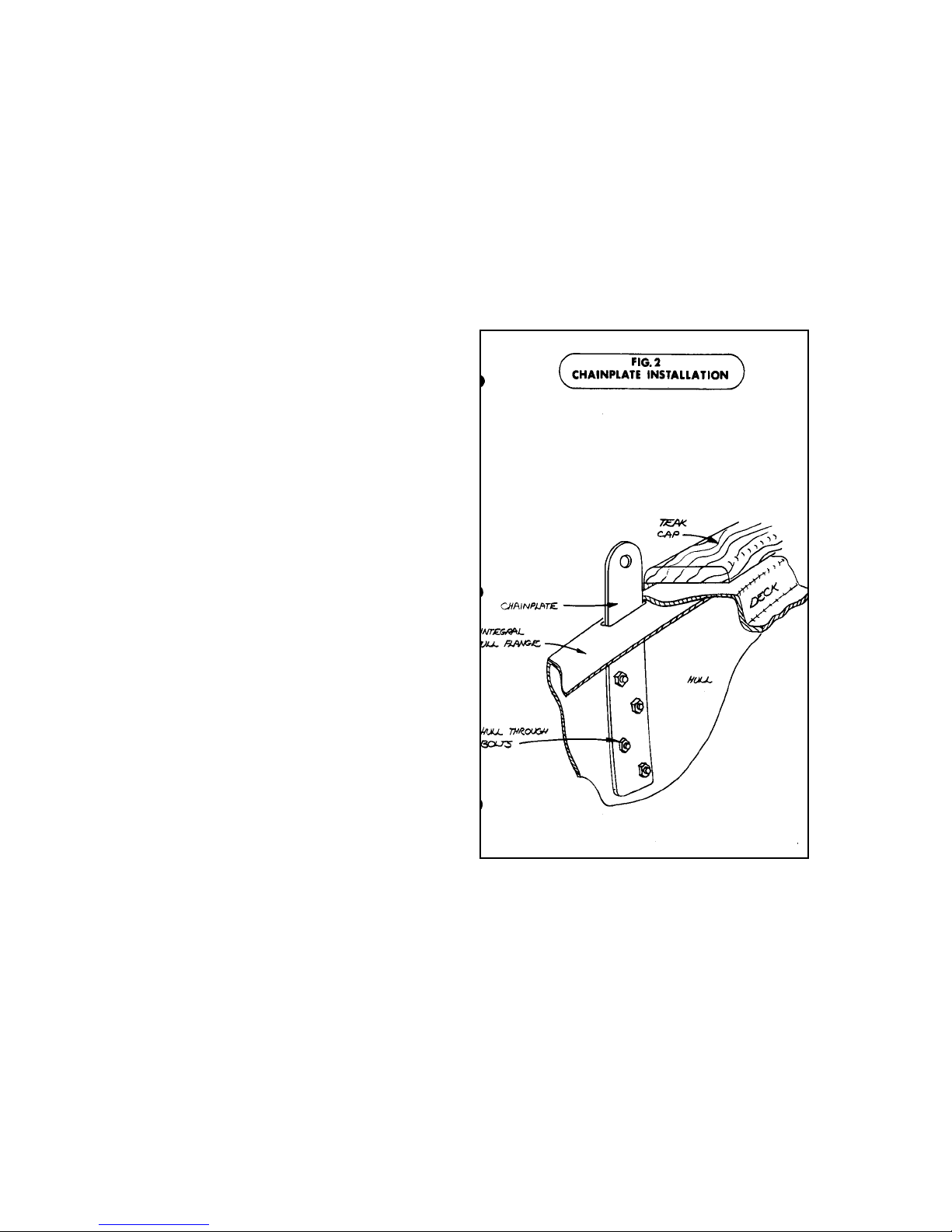

4.2) Standing Rigging, Running Rigging, Chainplates:

Standing rigging refers to all the fixed pieces of

stainless steel wire which support the mast. If

they principally support the spar in a fore and

aft direction, they are called “stays” (backstay,

forestay, etc.). If they support mainly from side

to side, they are called “shrouds” (upper

shroud, etc.).

The forestay attaches to the stem head fitting at

the bow. This is fabricated of welded stainless

steel and through bolted to the hull with backup plates. All other stays and shrouds are

attached to chainplates at the edge of the deck.

These chainplates are stainless steel straps

through bolted to the hull. Additional fiberglass

reinforcement is molded into the hull in all

chainplate areas. See Figure #2 for a

description of this installation.

All standing rigging is attached to chainplates

with adjustable turnbuckles that allow fine

tuning of rigging tension.

Running rigging includes all working lines or

cables that normally require adjustment when

sailing. Examples of these include halyards,

sheets, reefing gear, outhauls, etc.

All halyards are stainless steel wire rope spliced

to dacron line tails to minimize stretch, reduce

windage aloft, and maximize service life. All

halyards are run externally to the mast to

facilitate inspection, repair, or replacement.

4.3) Static Tuning (At the Dock)

First, make certain that the mast is centered on the boat, straight up and down when viewed from the

bow or stern. To make certain the mast is plumb transversely, slacken the lower shrouds fully by

undoing their turnbuckles. Make sure the mast wedges are removed from the main mast, which is

stepped through the deck. Take the main halyard and lead the shackle end to a point at the deck edge

so the shackle just touches the chainplate or rail with a given tension. Tie off the halyard. Take the

halyard to the same location on the other side and with the same tension the shackle should just touch

the rail or chainplate. If not, let off one upper shroud’s turnbuckle and take up on the other to bring the

masthead closer to centerline until the halyard shackle touches both points under the same tension. The

6

particular part of the rail or deck you choose as your reference point is not important as long as it is the

same point on each side After the mast is centered transversely, tighten both upper shroud turnbuckles

uniformly, one full turn on one side, then one full turn of the other. Repeat until the turnbuckles

become difficult to turn. Pin the turnbuckles Tighten up the lower shroud turnbuckle so that almost all

of the slack is removed. That is, the shroud itself should be able to flop about 1” in each direction.

Sight up the trailing edge of the spar to make sure that it is still straight. Now, check your rake. With

the main halyard hanging plumb behind the mast, the shackle end should be about one mast width

away from the back face of the mast, near the gooseneck. It’s best to do this on a calm day and to hang

a weight on the halyard such as a hammer, wrench, or bucket of water.

Ease off the forestay or backstay as required and tighten the other to adjust the rake. Large adjustments

may also necessitate tightening and loosening of the forward and aft lower shrouds. Once proper rake

is established, further adjustment should not be necessary of either the forestay or backstay. Tighten

the turn-buckles to obtain proper tension and pin.

Reinstall the mast wedges and trim collar on the main mast.

Check that the spreaders are angled upward slightly to equalize the angles above and below between

the spreader and the shroud. Tape and pad the spreader ends to avoid wear and tear on sails.

4.4) Dynamic Tuning (Under Sail)

Select a pleasant day with a steady 8 to 12 knots of breeze. Put the boat on a starboard tack, close

hauled Sight up the luff groove of the spar. If the mast seems to fall off to leeward at the spreaders, luff

up slightly and tighten the starboard lower shrouds a couple of turns. Put the boat back on the wind and

check the spar again. When the mast appears straight, put the boat about and do the same on the port

side. Check the following carefully. First, if the upper shrouds are at optimum tension, then the

leeward rigging should begin to look slack when at about l5

leeward shrouds should never be tightened. Secondly, when close hauled under genoa and main, the

forestay will appear quite sagged. Tensioning the backstay will reduce the amount of sag, but the sag

itself can never be completely eliminated.

0

-200 of heel. This is quite natural and the

The forward lower shrouds should be tightened marginally more than the aft lowers to encourage a bit

of a forward bow to the mast. This forward bow is counteracted by the luff of the mainsail and the aft

lowers. Aft bow of the mast should not be allowed, it destroys the sail shape and is countered only by

the forward lower shrouds. If you find that the mast tends to bow aft rather than forward under

backstay tension, the problem may then lie in your mast step. For example, if the mast is resting on its

forward end, it may tend to bow aft. Therefore, to correct this situation, wedge up the after part of the

heel to encourage a forward bow.

If yours is a brand new boat, chainplates may seat and the rigging may stretch to the extent that tuning

from scratch will be necessary in a matter of weeks. This is expected and typical of any new boat.

However, after this initial working-in period, you will find that your boat tends to hold this tune for

fairly long periods of time. After becoming used to the feel of the boat, you may wish to either increase

or decrease the amount of “weather helm” - that is, the amount of feel on the wheel. Any sailboat when

going upwind should have a tendency to “round up” slightly or head into the wind if you let go of the

helm. However, if you’re constantly fighting the boat in order to hold her off the wind, you have too

much weather helm. This can be alleviated by taking some rake out of the spar; i.e., raking the spar

further forward, and thus moving the center of effort of the sailplan further forward. If you find when

sailing upwind that the boat tends to fall off the wind and you are constantly having to push her to

weather, then you probably have lee helm. This can be overcome by putting a bit more rake into the

spar.

With constant tuning as the season progresses, your boat performance will improve. The boat will feel

more comfortable to sail. You will find that tuning is a bit of an art; you’ll begin to notice subtle

changes in the behaviour and response of your boat as you make subtle changes in tuning. The

important thing to remember is to go about things in a slow and orderly fashion, and before you make

any change, make sure it makes sense in your own mind.

7

Loading...

Loading...