Crown PZM-2.5, PZM-11, PZM-10LL, PZM-11LL, PZM-6D Application Manual

...

PZM, PCC, SASS AND BOUNDARIES

© 2000 Crown International, All rights

reserved PZM® , PCC®, SASS® and

DIFFEROID®, are registered trademarks of

Crown International, Inc. Also exported

as Amcron

127018-1

7/00

®

Crown International, Inc

P.O. Box 1000, Elkhart, Indiana 46515-1000

(219) 294-8200 Fax (219) 294-8329

www.crownaudio.com

Contents

Background to boundary microphones 1

How the boundary microphone works 2

The PCC microphone 3

Boundary microphone techniques for recording 4

Boundary microphone techniques for sound reinforcement 8

PZM boundaries 9

The SASS PZM stereo microphone 17

How to use the SASS microphone 20

INTRODUCTION

A boundary microphone is a miniature microphone

designed to be used on a surface such as a piano lid,

wall, stage floor, table, or panel. Mounting a miniature

mic on a surface gives several benefits:

• A clearer, more natural sound quality

• Extra sensitivity and lower noise

• Consistent tone quality anywhere around the

microphone

• Natural-sounding pickup of room reverberation

Crown boundary microphones include the PZM, PCC,

MB, and SASS series microphones. This guide explains

how they work and how to use them. For information

on the CM, GLM, and LM models, please see the Crown

Microphone Application Guide.

BACKGROUND

In many recording and reinforcement applications,

the sound engineer is forced to place microphones near

hard reflective surfaces. Some situations where this

might occur are recording an instrument surrounded

by reflective baffles, reinforcing drama or opera with the

microphones near the stage floor, or recording a piano

with the microphone close to the open lid.

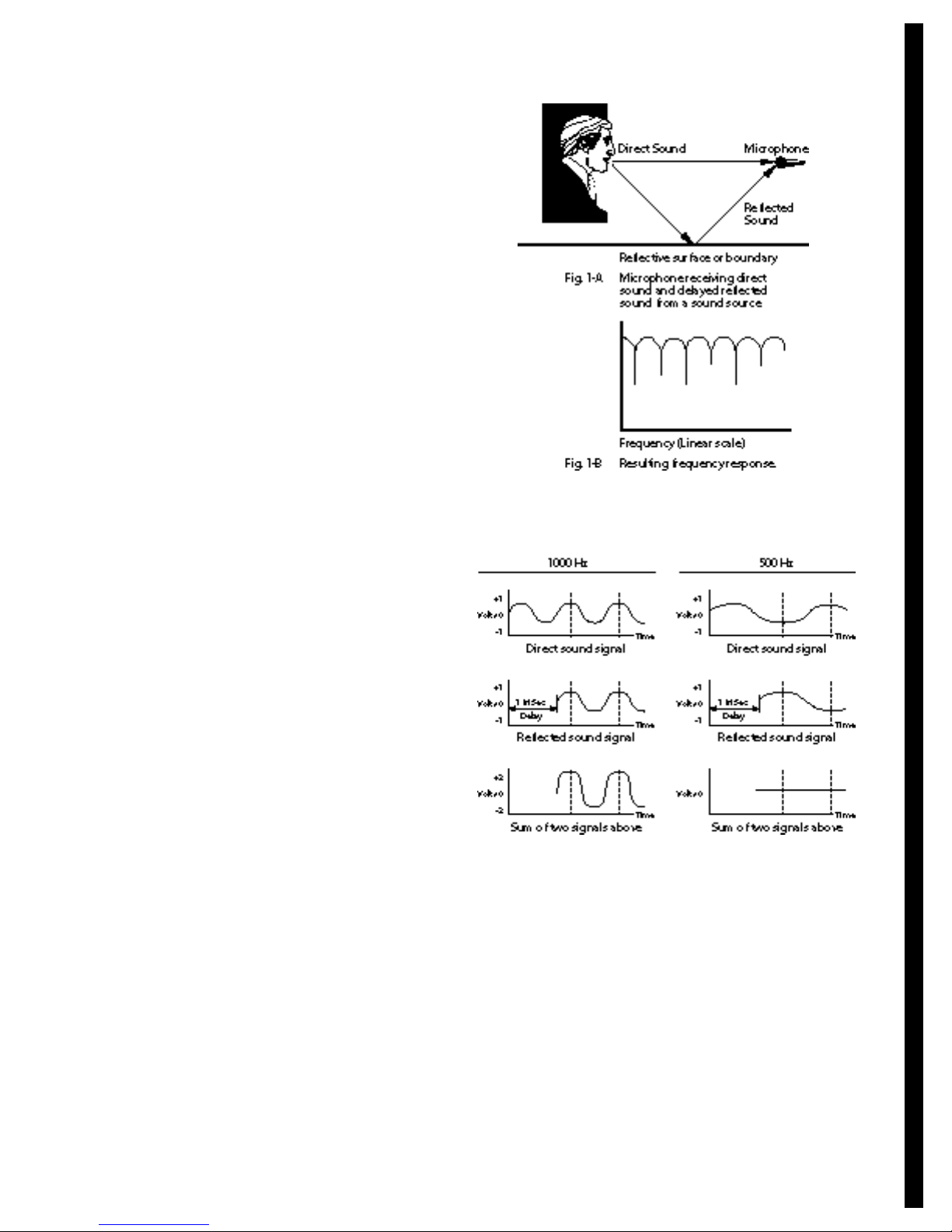

When a microphone is placed near a reflective surface,

sound travels to the microphone via two paths: (1) directly from the sound source to the microphone, and

(2) reflected off the surface (as in Fig. 1-A). Note that

the reflected sound travels a longer path than the direct

sound, so the reflected sound is delayed relative to the

direct sound. The direct and delayed sounds combine

at the microphone diaphragm.

All frequencies in the reflected sound are delayed by the

same time. Having the same time delay for all frequencies creates different phase delays for each frequency,

because different frequencies have different wavelengths. For example, a time delay of 1 millisecond

causes a 360-degree phrase shift for a 1000-Hz wave,

but only a 180-degree phase shift for a 500-Hz wave.

Fig. 2 illustrates this point.

At frequencies where the direct and delayed sounds are

in-phase (coherent), the signals add together, doubling

the pressure and boosting the amplitude 6 dB. At frequencies where the direct and delayed signals are outof-phase, the signals cancel each other, creating a dip

or notch in the response. There results a series of peaks

and dips in the net frequency response called a comb-

filter effect , so named because the response looks like

the teeth of a comb. (Fig. 1-B).

This bumpy frequency response colors the tonal reproductions, giving an unnatural sound. To solve this prob-

Fig. 1

Fig. 2 - Example of wave addition and

cancellation at two different frequencies.

lem, we need to shorten the delay of the reflected sound

so that it arrives at the microphone at the same time the

direct sound does.

If the microphone is placed on the reflective surface (as

in Fig. 3), the direct and reflected sound paths become

nearly equal. There is still a short delay in the reflected

sound because the center of the microphone diaphragm

(where the two sound paths combine) is slightly above

the surface. Consequently, the high frequencies may be

cancelled, giving a dull sound quality.

1

HOW THE BOUNDARY

MIC WORKS

By orienting the diaphragm parallel with the boundary

(as in Fig. 4), the diaphragm can be placed as close to

the boundary as desired. Then the direct and reflected

waves arrive simultaneously at the microphone sound

entry (the slit between the microphone diaphragm and

the boundary). Any phase cancellations are moved outside the audible band, resulting in a smooth frequency

response.

response is not severely degraded.

The Pressure Zone can be defined another way: The

Pressure Zone is the distance from the boundary that

the microphone diaphragm must be placed to achieve

the desired high-frequency response. The closer the

diaphragm is placed to the boundary (up to a point),

the more extended is the high-frequency response.

Let’s show some examples.

For a frequency response down a maximum of 6 dB

at 20 kHz, the mic-to-boundary spacing should be .11."

Or you could say the Pressure Zone is .11" thick. This

spacing corresponds to

1

⁄6 wavelength at 20 kHz.

For a response down 3 dB maximum at 20 kHz, the

spacing should be .085" (

1

⁄8 wavelength at 20 kHz).

For a response down 1 dB maximum at 20 kHz, the

spacing should be .052" (

1

⁄13 wavelength at 20 kHz).

Note that the thickness of the Pressure Zone is an arbitrary number depending on frequency. For example,

the direct and reflected waves of a 100-Hz tone are

effectively in-phase within a Pressure Zone 10" thick.

The Crown PZM microphone-to-boundary spacing

is only .020", which relates to 1 dB down at 52 kHz.

Pressure doubling

As stated earlier, comb-filtering is eliminated when the

direct and reflected waves add together in-phase. There

is another benefit: the sound pressure doubles, giving a

6 dB increase in acoustic level at the microphone. Thus

the effective microphone sensitivity increases 6 dB, and

the signal-to-noise ratio also increases 6 dB.

Consistent tonal reproduction

independent of source height

The microphone placements shown in Figs. 1 and 3

cause another problem in addition to rough response.

As the sound source moves up or down relative to the

surface, the reflected path length changes, which varies

the comb-filter notch frequencies. Consequently, the effective frequency response changes as the source moves.

But with the PZM, the reflected path length stays equal

to the direct path length, regardless of the sound-source

position. There is no change in tone quality as the

source moves.

Lack of off-axis coloration

Yet another problem occurs with conventional microphones: off-axis coloration. While a microphone may have

a flat response to sounds arriving from straight ahead

(on-axis), it often has a rolled-off or colored response to

sounds arriving from other directions (off-axis).

That fault is mainly due to the size of the microphone

and its forward orientation. When sound strikes the microphone diaphragm on-axis, a pressure boost occurs at

The technique of mounting a microphone in this manner is called the Pressure Recording Process

TM

(invented

by Ed Long and Ron Wickersham). They developed the

first microphone to use this process. The first manufactured microphone using the principle was the Pressure

Zone Microphone

®

(developed by Ken Wahrenbrock).

PZM

®

s are now manufactured by Crown International,

the first company licensed to the build microphones

using the Pressure Recording Process.

The Pressure Zone is the region next to the boundary

where the direct and reflected waves are in-phase (or

nearly so). There may be a slight phase shift between

the direct and reflected waves, as long as the frequency

2

Fig. 3 - Conventional microphone on floor receiving

direct sound and slightly delayed reflected sound.

Fig. 4

frequencies where the wavelength is comparable to

the microphone diameter (usually above about 10 kHz).

This phenomenon is called diffraction. Sounds approaching the microphone from the sides or rear,

however, do not experience a pressure boost at high

frequencies. Consequently, the high-frequency response

is greater on-axis than off-axis. The frequency response

varies with the position of the sound source.

Since the PZM capsule is very small, and because all

sound enters the capsule through a tiny, radially symmetric slit, the response stays constant regardless of the

angle at which sound approaches the microphone. The

effective frequency response is the same for sounds

from the front as it is for sounds from other directions.

In other words, there is little or no off-axis coloration

with the PZM. The reproduced tone quality doesn’t

change when the sound source moves.

As further benefit, the PZM has an identical frequency

response for random-incidence sound as it has for direct sound. Direct sound is sound traveling directly

from the source to the microphone; random incidence

sound is sound arriving from all directions randomly.

An example of random-incidence sound is ambience

or reverberation – sounds reflected off the walls, ceiling,

and floor of the recording environment.

With most conventional microphones, the response

to reverberant, random-incidence sound is rolled off in

the high frequencies compared to the response to direct

sound. The direct sound may be reproduced accurately,

but the reproduced reverberation may sound duller

than in real life.

This fact leads to some problems in recording classical

music with the microphones placed far enough away to

pick up concert-hall ambience. The farther from the

sound source the microphone is placed, the more reverberant is the sound pickup, and so the duller the sound

is. The effective microphone frequency response may

become duller (weaker in the high frequencies) as the

microphone is placed farther from the sound source.

This doesn’t occur with the PZM when it’s used on the

floor. The effective response stays the same regardless

of the mic-to-source distance. The response to ambient

sound (reverberation) is just as accurate as the response

to the direct sound from the source. As a result, the total

reproduction is brighter and clearer.

Reach

“Reach” is the ability to pick up quiet distant sounds

clearly. “Clearly” means with a high signal-to-noise ratio, a wide smooth frequency response, and a high ratio

of direct sound to reverberant sound.

As described earlier; the PZM has several performance attributes that contribute to excellent reach. The signal-to-

noise ratio is high because the signal sensitivity is boosted

6 dB by the on-surface mounting. The frequency response

is wide and smooth because comb filtering is eliminated,

and because reverberant sound is picked up with a full

high-frequency response. The direct-to-reverberant sound

ratio is high because the direct sound is boosted 6 dB near

the surface, while the reverberant sound, being incoherent,

is boosted only about 3 dB.

If the PZM element is mounted in a corner, the direct sound

is boosted 18 dB, while reverberant sound is boosted only

9 dB. This gives the PZM a 9 dB advantage over a conventional omnidirectional microphone in the ratio of direct-toreverberant sound. In other words, distant sources sound

closer and clearer with the PZM than they do with a conventional omnidirectional microphone.

Low vibration sensitivity

The low mass and high damping of the PZM diaphragm

make it relatively insensitive to mechanical vibrations

such as table and floor thumps and clothing noise.

The only pickup of theses sounds is acoustic pickup

through the air, not mechanical pickup through the

microphone housing.

Small size

In addition to the acoustic benefits of the PZM, there are

psychological benefits related to its low-profile design.

Its inconspicuous appearance reduces “mic fright.” Since

the PZM does not point at the performers, they may feel

more relaxed in not having to aim their instruments at

the microphone.

PZMs can be hidden in theatre sets. In TV-studio applications, the PZM practically disappears on-camera.

PZMs reduce clutter on the conference tables and lecterns, giving the feeling that no microphones are in use.

THE PCC

The Phase Coherent Cardioid (PCC) is a surfacemounted supercardioid microphone which provides

the same benefits previously mentioned for the PZM.

Unlike the PZM, however, the PCC uses a subminiature

supercardioid mic capsule. Its directional polar pattern

improves gain-before-feedback, reduces unwanted room

noise and acoustics, and rejects sound from the rear.

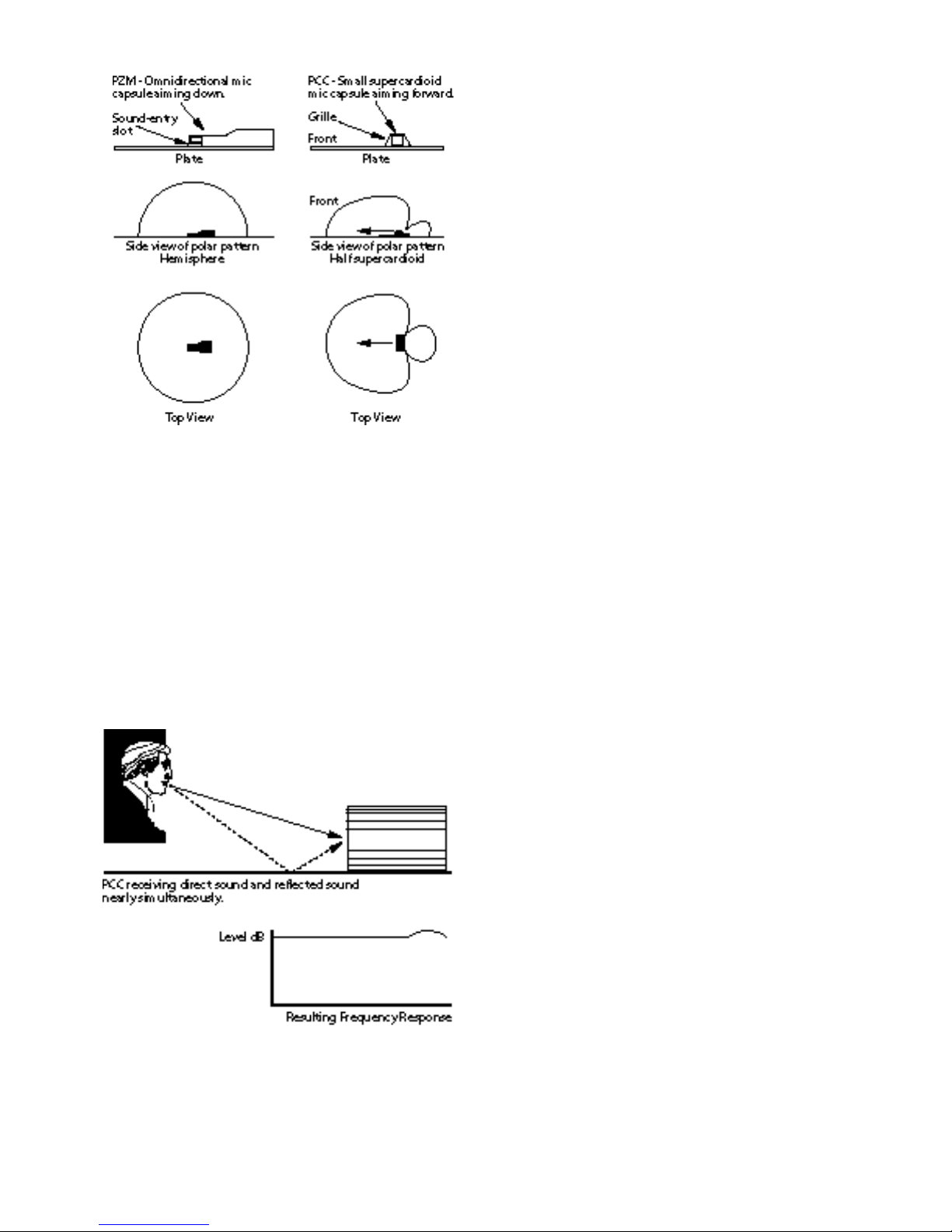

Fig. 5 shows the difference in construction and polar

patterns of the PZM and PCC.

In the Crown PCC, the microphone diaphragm is small

enough so that any phase cancellations are above the

audible range (Fig. 6). This results in a wide, smooth frequency response free of phase interference. In contrast,

the mic capsules in conventional microphones are relatively large. As a result, reflections are delayed enough to

cancel high frequencies, resulting in dull sound (Fig. 3).

3

BOUNDARY MICROPHONE

TECHNIQUES FOR RECORDING

Before placing microphones, work on the “live” sound

of the instrument or ensemble to be recorded. Do what

you can to improve its sound in the studio.

To determine a good starting microphone position, close

one ear with your finger; listen to the instrument with

the other, and move around until you find a spot that

sounds good. Put the PZM there, or put it on the floor

or table at that distance.

Moving the microphone around the instrument will

vary the tone quality, because an instrument radiates a

different spectrum in every direction. Place the PZM to

get the desired tone quality, then use equalization only

if necessary. Note that the response of the PZM does not

change with the angle of incoming sound, but the spectrum of the instrument does change depending on how

it is aimed at the PZM.

To reduce pickup of acoustics, leakage from other instruments and background noise, move the PZM closer

to the sound source. Mike only as close as necessary,

since too-close placement may result in an unnatural

tonal balance. Move the PZM farther from the source

to add ambience or “artistic leakage” to the recording.

To further reduce pickup of unwanted sounds, mount

the PZM on a large baffle or acoustic panel placed between the PZM and the offending noise source.

Use the smallest number of microphones that provide

the desired sound; use as few as necessary. Sometimes

this can be done by covering several sound sources with

a single microphone. The wide polar pattern of the PZM

allows you to pick up several instruments or vocalists on

a single microphone with equal fidelity.

Follow the 3:1 rule: When multiple microphones are

mixed to the same channel, the distance between the

microphones should be at least three times the micto-source distance. This procedure reduces phase interference between the microphones. For example, if two

microphones are each placed 2 feet from the instruments

they cover, the mics should be at least 6 feet apart.

PZMs used in multiple-microphone applications may

pick up a lot of leakage (“off-mic” sounds from other instruments). This leakage usually sounds good, however,

owing to the PZM’s uncolored off-axis response. Artistic

usage of leakage can add pleasing “liveliness” to the recording.

When a PZM is mounted on a wall, the wall becomes

a part of the microphone. When a PZM is mounted in

a corner, then all three walls become part of the microphone. The Pressure Zones of all the walls combine to

reinforce the sound pickup. Use this fact to your advantage by mounting the PZM capsule at the junction of

multiple boundaries whenever possible.

Fig. 5

4

Technically, the PCC is not a Pressure Zone Microphone.

The diaphragm of a PZM is parallel to the boundary;

the diaphragm of the PCC is perpendicular to the

boundary. Unlike a PZM, the PCC “aims” along the

plane on which it is mounted. In other words, the main

pickup axis is parallel with the plane.

Because of its supercardioid polar pattern, the PCC has

nearly a 6 dB higher direct-to-reverberation ratio than

the PZM; consequently, distant sources sound closer and

clearer with the PCC than with the PZM.

Fig. 6

The following are some guidelines for PZM placement

in various recording applications. Many were provided

by users. Although these techniques have worked well

in many situations, they are just suggestions.

Acoustic guitar, mandolin, dobro,

banjo:

• On panel in front, about 2 feet away, guitar height.

• On panel in front and overhead to avoid interference

with audience viewing.

• On floor (for soloist).

String section:

• On panel above and in front of the entire section.

• On panel midway between two instruments, about

6 feet high.

Fiddle or Violin:

• On panel in front or overhead.

• On music stand.

Cello or acoustic bass:

• On panel on floor, in front, tilted toward performer.

• On panel in front and above.

• On floor (for soloist).

String quartet:

• Spaced pair on floor about 3 to 6 feet apart.

• Spaced pair on panels in front and above, spaced

3 to 6 feet apart.

Harp:

• On panel about 2 1⁄2 feet away, aiming toward treble

part of sound board.

Sax, flute, clarinet:

• On panel in front and slightly above.

• On music stand.

Horns, trumpet, cornet, trombone:

• On wall, on hard-surface gobo, or on control-room

window. Performers play to the wall or gobo a few feet

away. Since their sound bounces off the wall back to

them, they can hear each other well enough to produce

a natural acoustic balance.

• On panel in front of and between every two players,

1 to 2 feet away.

• On music stand.

• Tuba – on panel overhead.

Grand Piano:

• Tape a PZM to the underside of the lid in the middle

(Fig. 7). Put the lid on the long stick for best sound

quality. To reduce leakage and feedback, put the lid on

the short stick or close the lid and cover the piano with

a heavy blanket.

• For stereo, use two PZMs taped under the lid – one

over the treble strings near the hammers, one over the

bass strings well away from the hammers. Microphone

placement close to the hammers emphasizes attack;

placement far from the hammers yields more tone.

• To pick up the piano and room ambience with a single

microphone, place a PZM on a panel about 6 to 8 feet

from the piano, 4 feet high. Put the lid on the long stick,

and face the panel at the piano with the panel perpendicular to the lid.

• To add ambience to a close-miked piano, mix in a PZM

or two placed on a wall far from the piano.

• For singers who accompany themselves on a piano,

mount two PZMs on opposite sides of a panel. Place the

panel about where the music rack would be. For stereo,

use a longer panel with two microphones on each side

of the panel.

Amplifier/speaker for electric guitar,

piano, bass:

• On panel in front of amp.

• On floor a few feet in front of amp. For an interesting

coloration, add a panel a few feet behind the microphone.

• Inside the cabinet.

Leslie organ cabinet:

• Two PZMs on either side of the rotating horn, inside the

top of the cabinet. Place another PZM inside the bottom cabinet.

Drum set:

• On panel or hard gobo, 1 to 2 feet in front of set, just

above the level of the tom-toms. Use two microphones

3 feet apart for stereo. The drummer can balance the

sound of the kit as he or she plays. Also hang a smallplate PZM vertically in the kick drum facing the beater

head, with a pillow or blanket pressing against the

beater head. The high sound pressure level will not

cause distortion in the PZM’s signal.

• Try two PZMs overhead, each mounted on a 1-foot

square panel, angled to form a “V,” with the point of the

“V” aiming down. Omit the panel for cymbal miking.

• Two PZMs on a hard floor, about 2 feet to the left and

right of the drummer.

• Tape a PZM to a gauze pad and tape the pad to the kick

drum beater head near the edge. This mic will also pick

up the snare drum.

• See percussion below.

Fig. 7

5

Loading...

Loading...