Crown CM-200A, CM-310A, CM-700, GLM-100, LM-201 Application Manual

...

© 2000 Crown International, All rights reserved.

PZM® , PCC®, SASS® and DIFFEROID®, are registered trademarks of

Crown International, Inc. Also exported as Amcron

131374-1

®

6/00

Crown International, Inc

P.O. Box 1000, Elkhart, Indiana 46515-1000

(219) 294-8200 Fax (219) 294-8329

www.crownaudio.com

MICROPHONE TECHNIQUES FOR VIDEO

No matter what your video application — sports,

news, corporate training — the soundtrack quality

depends on the microphones you choose and where

you place them. This booklet covers microphone

techniques to help you achieve better audio for

your video productions.

There are many types of microphones, each designed to help you solve a specific audio problem.

We’ll sort out these types and tell where each one is

useful. Then we’ll cover specific applications — how

to use microphones effectively in various

situations.

TRANSDUCER TYPES

A microphone is a transducer, a device that converts energy from one form into another. Specifically, a microphone converts acoustical energy

(sound) into electrical energy (the signal).

A ribbon microphone works the same, except that

the diaphragm is also the conductor. It is a thin metal

foil or ribbon suspended in a magnetic field.

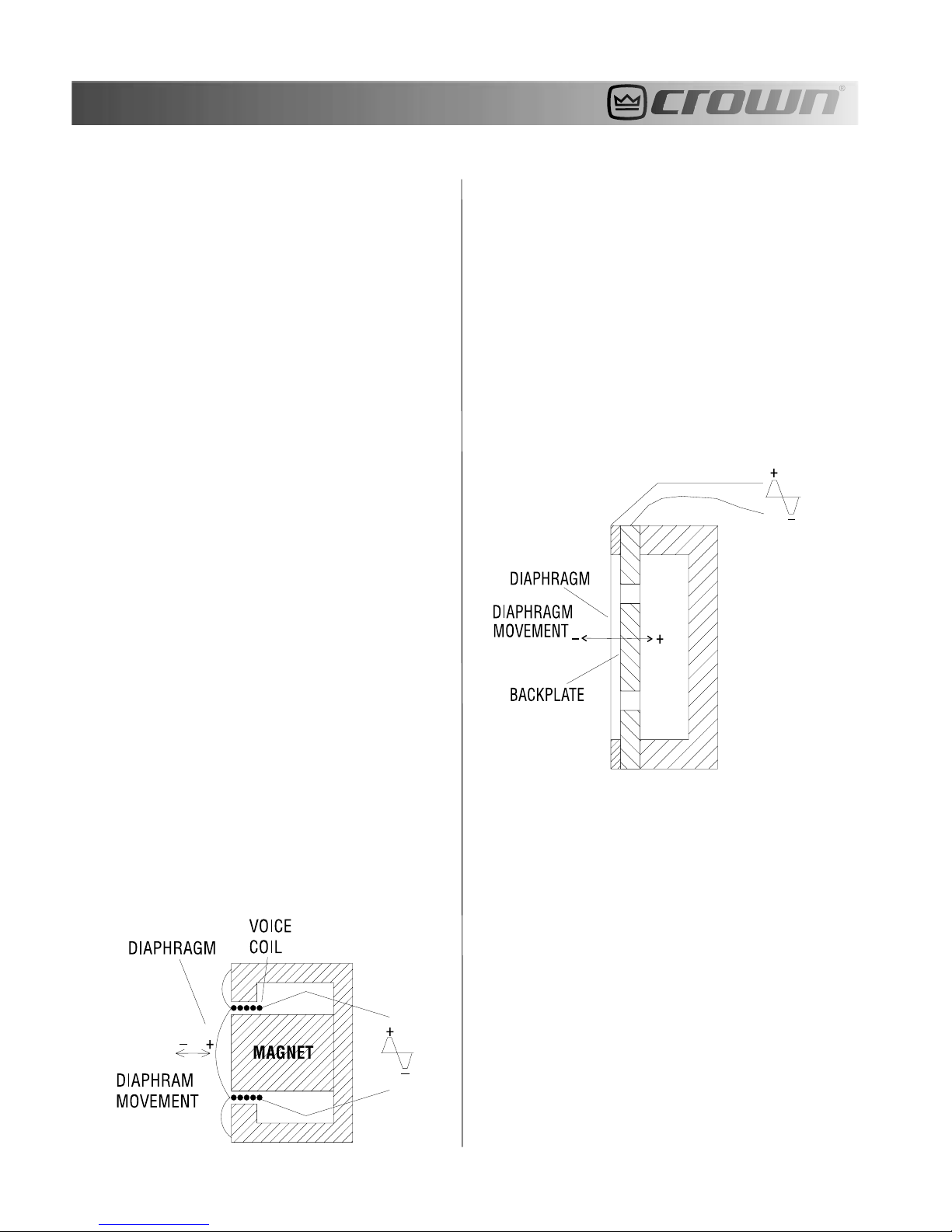

In a condenser microphone (Figure 2), a diaphragm

and an adjacent metallic disk (backplate) are

charged to form two plates of a capacitor. Sound

waves striking the diaphragm vary the spacing between the plates; this varies the capacitance and

generates an electrical signal similar to the incoming sound wave.

Fig. 2 – A condenser microphone.

Microphones differ in the way they convert sound

to electricity. Three popular transducer types are dynamic, ribbon, and condenser.

In a dynamic microphone (Figure 1), a coil of wire

attached to a diaphragm is suspended in a magnetic field. When sound waves vibrate the diaphragm, the coil vibrates in the magnetic field and

generates an electrical signal similar to the incoming sound wave.

Fig. 1 – A dynamic microphone.

The diaphragm and backplate can be charged either by an externally applied voltage or by a permanently charged electret material in the diaphragm

or on the backplate.

Because of its lower diaphragm mass and higher

damping, a condenser microphone responds faster

than a dynamic microphone to rapidly changing

sound waves (transients).

Dynamic microphones offer good sound quality, are

especially rugged, and require no power supply.

Condenser microphones require a power supply to

operate internal electronics, but generally provide

a clear, detailed sound quality with a wider,

smoother response than dynamics.

2

Currently, all Crown microphones are the electret

condenser type — a design of proven reliability and

studio quality.

POLAR PATTERNS

Microphones also differ in the way they respond to

sounds coming from different directions. The sensitivity of a microphone might be different for

sounds arriving from different angles. A plot of microphone sensitivity verses the angle of sound incidence is called its polar pattern. Several polar

patterns are shown in Figure 3.

Fig. 3 – Polar patterns.

Three types of unidirectional patterns are the cardioid, supercardioid, and hypercardioid pattern. The

cardioid pattern has a broad pickup area in front of

the microphone. Sounds approaching the side of

the mic are rejected by 6 dB; sounds from the rear

(180 degrees off-axis) are rejected 20 to 30 dB. The

supercardioid rejects side sounds by 8.7 dB, and

rejects sound best at two “nulls” behind the microphone, 125 degrees off-axis.

The hypercardioid pattern is the narrowest pattern

of the three (12 dB down at the sides), and rejects

sound best at two nulls 110 degrees off-axis. This

pattern has the best rejection of room acoustics,

and provides the most gain-before-feedback from

the main sound reinforcement speakers.

Choose an omnidirectional mic when you need:

All-around pickup

Best pickup of room acoustics (ambience or

reverb)

An omnidirectional (omni) microphone is equally

sensitive to sounds coming from all directions. A

unidirectional microphone is most sensitive to

sounds coming from one direction — in front of

the microphone. A bidirectional (figure-eight)

microphone is most sensitive in two directions:

front and rear.

An omni microphone is also called a pressure mi-

crophone; a uni- or bi-directional microphone is

also called a pressure-gradient microphone.

Extended low-frequency response

Low handling noise

Low wind noise

No up-close bass boost

Choose a unidirectional mic when you need:

Selective pickup

Rejection of sounds behind the microphone

Rejection of room acoustics and leakage

More gain-before-feedback

Up-close bass boost

An omnidirectional boundary microphone (such as

a PZM) has a half-omni or hemispherical polar pattern. A unidirectional boundary microphone (such

as a PCC-160 or PCC-170) has a half-supercardioid

polar pattern. The boundary mounting increases the

directionality of the microphone, thus reducing

pickup of room acoustics.

3

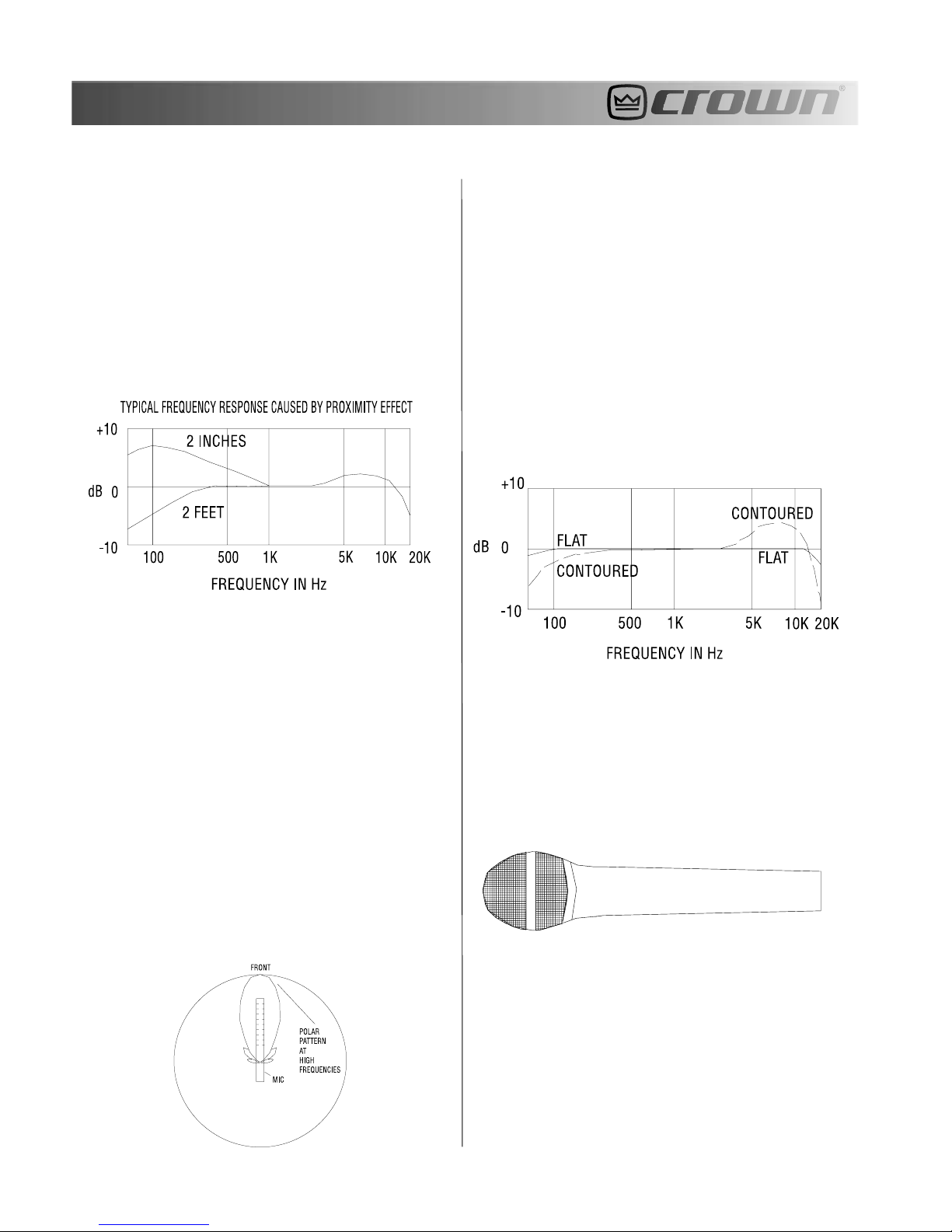

Most unidirectional mics have proximity effect, a

rise in the bass when used up close. Figure 4 is a

frequency-response graph that illustrates proximity effect. When the microphone is 2 feet from the

sound source, its low-frequency response rolls off.

But when the microphone is 2 inches from the sound

source, its low-frequency response rises, giving a

warm, bassy effect.

Fig. 4 – Proximity effect.

A special type of unidirectional microphone is the

variable-D type. Compared to a standard single-D

directional microphone, the variable-D has almost

no proximity effect, so it sounds natural when used

close up. The variable-D type also has less handling

noise and pop.

The most highly directional pattern is that of the

shotgun or line microphone (Figure 5). The shotgun microphone is used mainly for distant miking

(say, for dialog pickup where you want the mic to

be off-camera). It is highly directional at high

frequencies and hyper-cardioid at low frequencies.

The longer the shotgun mic is, the more directional

it is at mid-to-low frequencies.

Fig. 5 – Shotgun microphone and its polar pattern.

FREQUENCY RESPONSE

Each microphone has a different frequency response, which indicates the tonal characteristics

of the microphone: neutral, bright, bassy, thin, and

so on. Figure 6 shows two types of frequency response: bright (contoured) and flat. A bright frequency response has an emphasized or rising highfrequency response, which adds clarity, brilliance,

and articulation. A flat frequency response sounds

natural.

Fig. 6 – Frequency response.

FORMS OF MICROPHONES

Microphones come in many shapes that have different functions:

Fig. 7 – Handheld microphone.

Handheld (Figure 7). Used in the hand or on a mic

stand. An example is the Crown CM-200A cardioid

condenser microphone.

4

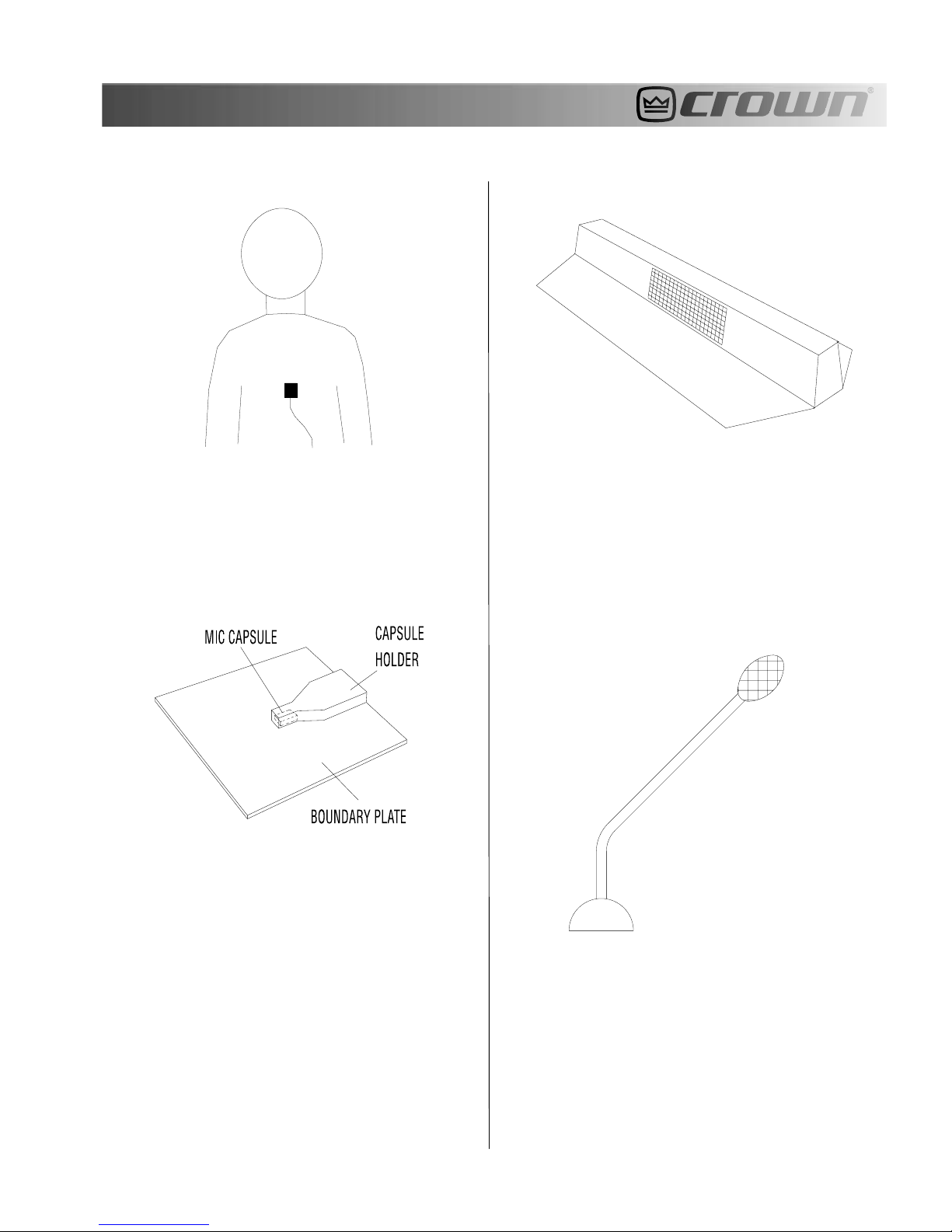

Fig. 8 – Lavalier microphone.

Lavalier (Figure 8). A miniature microphone which

you clip onto the clothing of the person speaking.

Two examples are the Crown GLM-100 (omni) and

GLM-200 (hypercardioid).

Fig. 9 – Boundary microphone.

Fig. 10 – Unidirectional boundary microphone.

The PCC (Figure 10) is a unidirectional boundary

microphone. When you place it on a surface, it has

a half-supercardioid polar pattern. The rugged PCC160 is especially useful for stage-floor pickup of

drama and musicals; the PCC-170 has a sleeker look

for miking a group discussion at a conference table.

Fig. 11 – Lectern microphone

Boundary (Figure 9). Boundary microphones are

meant to be used on large surfaces such as stage

floors, piano lids, hard-surfaced panels, or walls.

Boundary mics are specially designed to prevent

phase interference between direct and relected

sound waves, and have no off-axis coloration. Free-

field microphones are meant to be used away from

surfaces, say for up-close miking.

Crown Pressure Zone Microphones® (PZMs®) and

Phase Coherent Cardioids® (PCCs®) are boundary

microphones; Crown GLMs, CMs, and

LMs are free-field microphones.

Lectern A lectern microphone (Figure 11) is designed to mount on a lectern or pulpit. For example,

the Crown LM-300A and LM-300AL are slim, elegant units that plug into an XLR connector in the

lectern. The LM-301A screws onto a mic stand or

desk stand. Each has a silent-operating gooseneck.

The Crown LM-201 mounts permanently on the lectern, and has a rugged ball-and-socket swivel that

adjusts without any creaking.

5

Loading...

Loading...