Page 1

COMMODORE

n

DISK

DRIVE

useris

guide

v

■

Page 2

USER'S

MANUAL

STATEMENT

WARNING:

This

equipment has

been

certified

to

comply

with

the

limits

for

a

ClassBcomputing

device,

pursuant

to

subpartJof

Part

15

of

the

Federal

Communications

Commission's

rules,

which

are

designed

to

pro

vide

reasonable

protection

against

radio

and

television

interference

in

a

residential

installation.

If

not

installed

properly,

in

strict

accordance

with

the

manufacturer's

instructions,

it

may

cause

such

interference.

If

you

suspect

interference,

you

can

test

this

equipment

by

turning

it

off

and

on.

If

this

equipment

does

cause

interference,

correct

it

by

doing

any

of

the

following:

•

Reorient

the

receiving

antenna

or

AC

plug.

•

Change

the

relative

positions

of

the

computer

and

the

receiver.

•

Plug

the

computer

intoadifferent

outlet

so

the

computer

and

receiver

are

on

different

circuits.

CAUTION:

Only

peripherals

with

shield-grounded cables

(computer

input-

output

devices,

terminals,

printers,

etc.),

certified

to

comply

with

Class

B

limits,

can

be

attached

to

this

computer.

Operation

with

non-certified

peripherals

is

likely

to

result

in

communications

interference.

Your

house

AC

wall

receptacle

must beathree-pronged

type

(AC

ground).

If

not,

contact

an

electrician

to

install

the

proper

receptacle.

If

a

multi-connector

box

is

used

to

connect

the

computer

and

peripherals

to

AC,

the

ground

must

be

common

to

all

units.

If

necessary,

consult

your

Commodore

dealer

or

an

experienced

radio-

television

technician

for

additional

suggestions.

You

may

find

the

following

FCC

booklet

helpful:

"How

to

Identify

and

Resolve

Radio-TV

Interference

Problems."

The

booklet

is

available

from

the

U.S.

Government

Printing

Office,

Washington,

D.C.

20402,

stock

no.

004-000-00345-4.

Page 3

Page 4

1581

Disk

Drive

User's

Guide

Page 5

Copyright

©

1987

by

Commodore

Electronics

Limited

All

rights

reserved

This

manual

contains

copyrighted

and

proprietary

information.

No

part

of

this

publication

may

be

reproduced,

stored

inaretrieval

system,

or

transmitted

in

any

form

or

by

any means,

electronic,

me

chanical,

photocopying,

recording

or

otherwise,

without

the

prior

written

permissibn

of

Commodore

Electronics

Limited.

COMMODORE64isaregistered

trademarkofCommodore

Electronics

Limited

COMMODORE

128,

Plus4,and VIC20are

trademarks

of

Commodore

Electronics

Limited

Page 6

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

1

HOW

THIS

GUIDE

IS

ORGANIZED

1

PART

ONE:

BASIC

OPERATING

INFORMATION

CHAPTER

1:

UNPACKING,

SETTING

UP

AND

USING

THE

1581

3

step-by-step

instructions

3

troubleshooting

guide

5

tips

for

maintenance

and

care

7

inserting

a

diskette

8

using

pre-programmed

(software)

diskettes

8

how

to

prepareanew

diskette

10

diskette

directory

11

selective

directories

12

printing

a

directory

13

pattern

matching.

13

splat

files

14

CHAPTER

2:

BASIC

2.0

COMMANDS

15

error

checking

16

BASIC

hints

17

save

17

save

with

replace

18

verify

19

scratch

20

more

about

scratch.

21

rename

22

renaming

and

scratching

troublesome

files....

23

copy

24

validate

25

initialize

26

CHAPTER

3:

BASIC

7.0

COMMANDS

27

error

checking

27

save

27

save

with

replace

28

verify

'.

29

copy

29

concat

30

Page 7

scratch

30

more

about

scratch

31

rename

32

renaming

and

scratching

troublesome

files

33

collect

34

dclear

35

|

PART

TWO:

ADVANCED

OPERATION

AND

PROGRAMMING

|

CHAPTER

4:

SEQUENTIAL

DATA

FILES

37

openingafile

38

closing

a

file

43

reading

file

data:

using

input#

44

more

about

input#

45

numeric

data

storage

on

diskette

47

reading

file

data:

using

get#

48

demonstration

of

sequential

files

51

CHAPTER

5:

RELATIVE

DATA

FILES

53

files,

records,

and

fields

53

file

limits

54

creating

a

relative

file

54

using

relative

files:

record#

command

56

completing

relative

file

creation

58

expanding

a

relative

file

60

writing

relative

file

data

60

designing

a

relative

record

60

writing

the

record

61

reading

a

relative

record

64

the

value

of

index

files

67

CHAPTER

6:

DIRECT

ACCESS

COMMANDS

69

openingadata

channel

for

direct

access

69

block-read

70

block-write

71

the

original

block-read

and

block-write

commands

72

the

buffer

pointer

74

allocating

blocks

75

freeing

blocks

76

partitions

and

sub-directories

77

using

random

files

79

Page 8

CHAPTER

7:

INTERNAL

DISK

COMMANDS

81

memory-read.

82

memory-write

84

memory-execute

85

block-execute

85

user

commands

86

utility

loader

87

auto

boot

loader

88

CHAPTER

8:

MACHINE

LANGUAGE

PROGRAMS

89

disk-related

kernal

subroutines

89

CHAPTER

9:

BURST

COMMANDS

91

cmdl-read

91

cmd2-write

92

cmd3-inquire

disk

92

cmd4-format

93

cmd6-query

disk

format

94

cmd7-inquire

status

94

cmd8-dump

track

cache

buffer

95

chgutl

utility

95

fastload

utility

96

status

byte

breakdown

96

burst

transfer

protocol

97

explanation

of

procedures

98

CHAPTER

10:1581

INTERNAL

OPERATION

101

logical

versus

physical

disk

format

101

track

cache

buffer

101

controller

job

queue

102

vectored

jump

table

108

APPENDICES:

A:

changing

the

device

number

Ill

B:

dos

error

messages

113

C:

dos

diskette

format

119

D:

disk

command

quick

reference

chart

123

E:

specifications

of

the

1581

disk

drive

125

F:

serial

interface

information

127

USER'S

MANUAL

STATEMENT

inside

back

cover

Page 9

Page 10

INTRODUCTION

The

Commodore

1581

isaversatile

3.5"

disk

drive

that

can

be

used

withavariety

of

computers,

including

the

COMMODORE

128™,

the

COMMODORE

64®,

the

Plus

4™,

COMMODORE

16™,

and

VIC

20.™

Also,

in

addition

to

the

convenience

of

3.5"

disks,

the

1581

offers

the

following

features:

•

Standard

and

fast

serial

data

transfer

rates—The

1581

auto

matically

selects

the

proper

data

transfer

rate

(fast

or

slow)

to

match

the

operating

modes

available

on

the

Commodore

128

computer.

•

Double-sided,

double-density

MFM

data

recording—Provides

more

than

800K

formatted

storage

capacity

per

disk

(400K

+

per

side).

•

Special

high-speed

burst

commands—These

commands,

used

for

machine

language

programs,

transfer

data

several

times

faster

than

the

standard

or

fast

serial

rates.

HOW

THIS

GUIDE

IS

ORGANIZED

This

guide

is

divided

into

two

main

parts

and

seven

appendices,

as

described below:

PART

ONE:

BASIC

OPERATING

INFORMATION—includes

all

the

information

needed

by

novices

and

advanced

users

to

set

up

and

begin

using

the

1581

disk

drive.

PART

ONE

is

subdivided

into

three

chapters:

•

Chapter

1,

Unpacking,

Setting

Up

and

Using

the

1581,

tells

you

how

to

use

disk

software

programs

that

you

buy.

These

pre

written

programs

help

you

performavariety

of

activities

in

fields

such

as

business,

education,

finance,

science,

and

recrea

tion.

If

you're

interested

only

in

loading

and

running

pre

packaged

disk

programs,

you

need

read

no

further

than

this

chapter.

If

you

are

also

interested

in

saving,

loading,

and

run

ning

your

own

programs,

you

will

want

to

read

the

remainder

of

the

guide.

•

Chapter

2,

Basic

2.0

Commands,

describes

the

use

of

the

BASIC

2.0

disk

commands

with

the

Commodore

64

and

Com

modore

128

computers.

•

Chapter

3,

Basic

7.0

Commands,

describes

the

use

of

the

BASIC

7.0

disk

commands

with

the

Commodore

128.

Page 11

PART

TWO:

ADVANCED

OPERATION

AND

PROGRAMMING—is

primarily

intended

for

users

familiar

with

computer

program

ming.

PART

TWO

is

subdivided

into

six

chapters:

•

Chapter

4,

Sequential

Data

Files,

discusses

the

concept

of

data

files,

defines

sequential

data

files,

and

describes

how

sequen

tial

data

files

are

created

and

used

on

disk.

•

Chapter

5,

Relative

Data

Files,

defines

the

differences

between

sequential

and

relative

data

files,

and

describes

how

relative

data

files

are

created

and

used

on

disk.

•

Chapter

6,

Direct

Access

Commands,

describes

direct

access

disk

commands

asatool

for

advanced

users

and

illustrates

their

use.

•

Chapter

7,

Internal

Disk

Commands,

centers

on

internal

disk

commands.

Before

using

these

advanced

commands,

you

should

know

how

to

programa6502

chip

in

machine

lan

guage.

•

Chapter

8,

Machine

Language

Programs,

provides

a

list

of

disk-related

kernal

ROM

subroutines

and

givesapractical

ex

ample

of

their

use

inaprogram.

•

Chapter

9,

Burst

Commands,

gives

information

on

high-speed

burst

commands.

•

Chapter

10,1581

Internal

Operations,

describes

how

the

1581

operates

internally.

APPENDICES

ATHROUGH

F—provide

various

reference

information;

for

example,

AppendixAtells

you

how

to

set

the

device

number

through

use

of

two

switches

on

the

back

of

the

drive.

Page 12

PART

ONE

BASIC

OPERATING

INFORMATION

CHAPTER

1

HOW

TO

UNPACK,

SET

UP

AND

BEGIN

USING

THE

1581

STEP-BY-STEP

INSTRUCTIONS

1.

Inspect

the

shipping

carton

for

damage.

If

you

find

any

damage

to

the

shipping

carton

and

suspect

that

the

disk

drive

may

have

been

affected,

contact

your

dealer.

2.

Check

the

contents

of

the

shipping

carton.

Packed

with

the

1581

and

this

book,

you

should

find

the

following:

electrical

power

supply,

interface

cable,

Test/Demo

diskette,

and

a

warranty

card

to

be

filled

out

and

returned

to

Commodore.

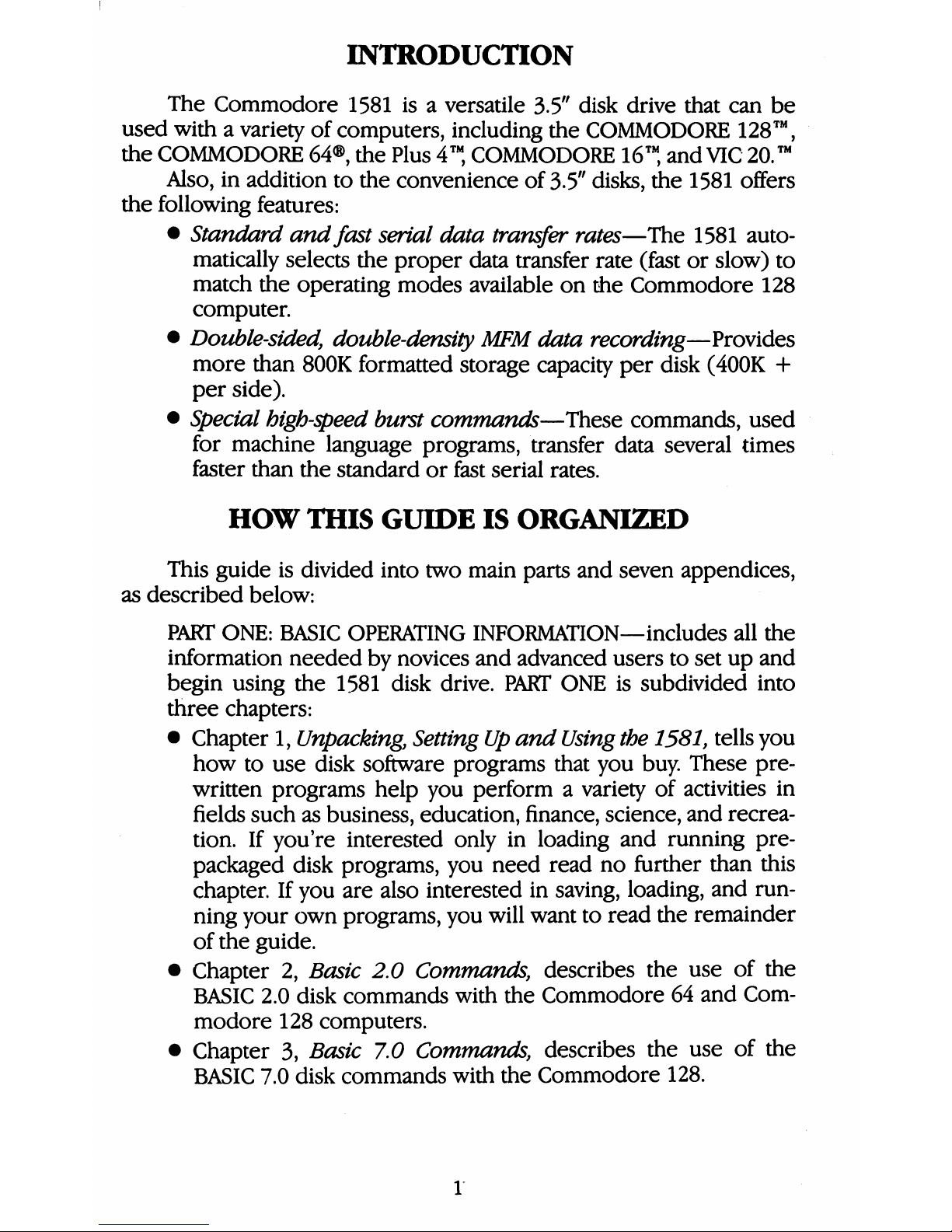

3.

Remove

the

shipping

spacer

from

the

disk

drive.

The

spacer

is

there

to

protect

the

inside

of

the

drive

during

shipping.

To

remove

it,

push

the

button

on

the

front

of

the

drive

(see

Figure

1)

and

pull

out

the

spacer.

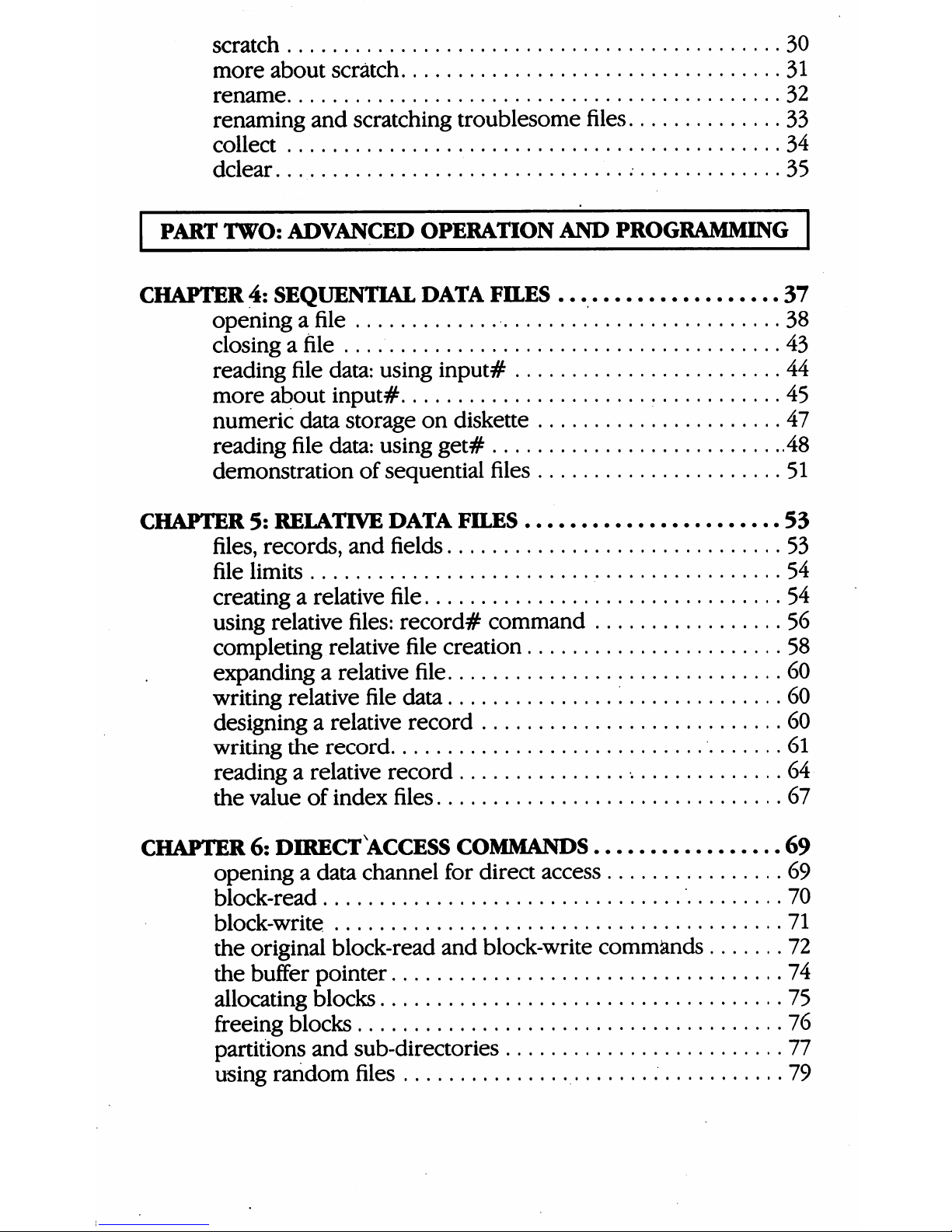

Figure1.Frontof1581

Disk

Drive

H

■

commodore

1581

^H

1

FLOPPY

DISK

DRIVE

■

V

THE

PRODUCT

DOES

NOT

NECESSARILY

RESEMBLE

THE

PICTURE

INSIDE

THE

USER'S

MANUAL

3

Page 13

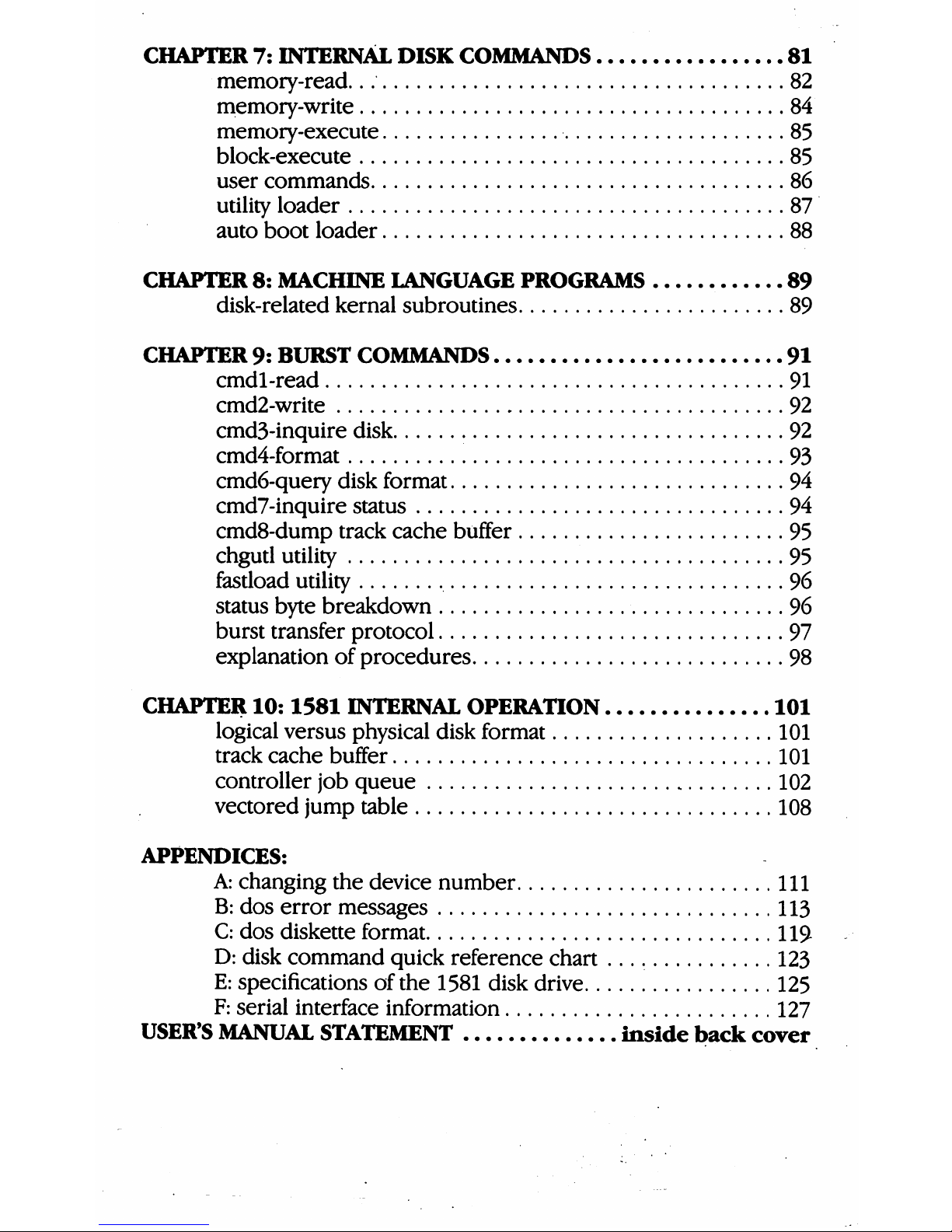

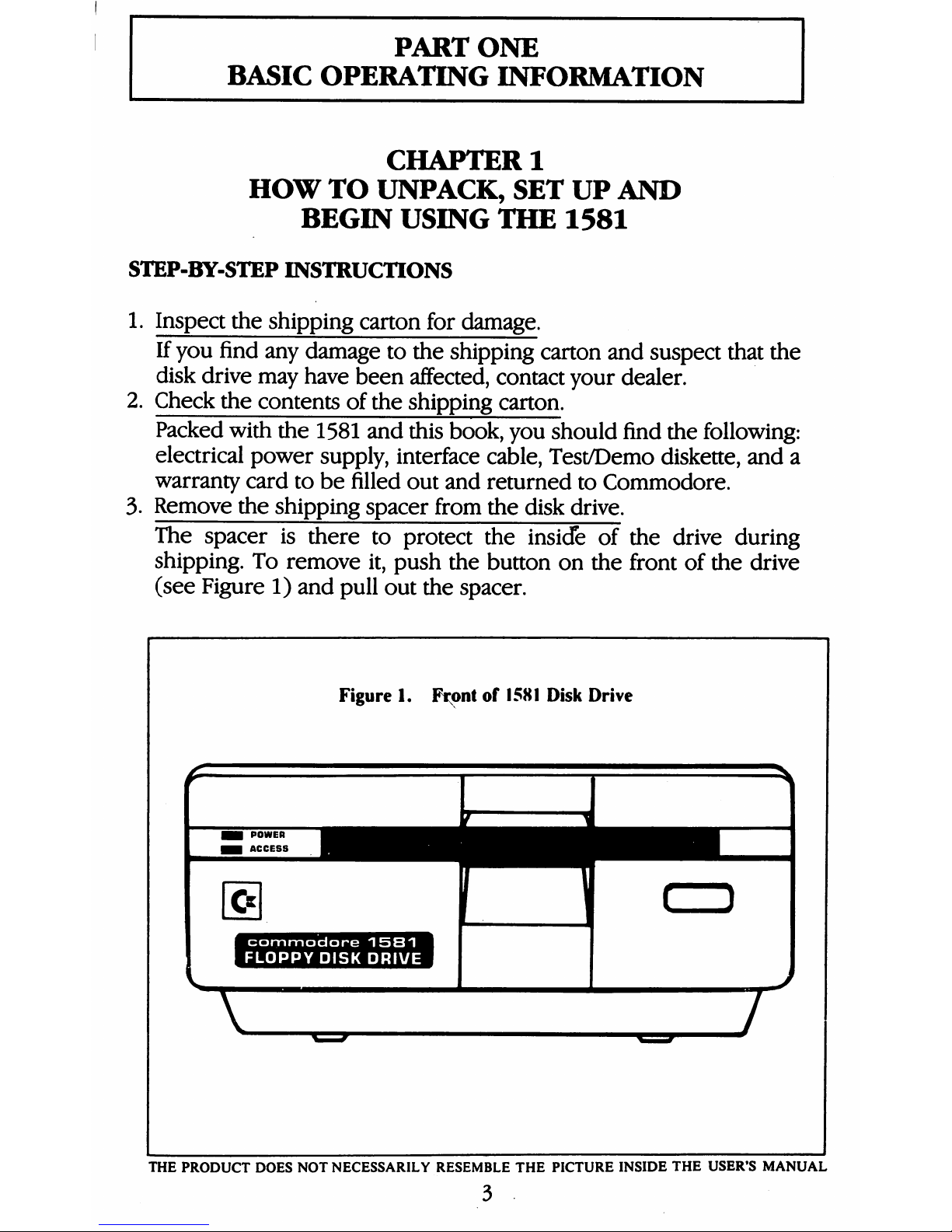

4.

Connect

the

power

cord.

Check

the

ON/OFF

switch

on

the

back

of

the drive

(see

Figure

2)

and

make

sure

it's

OFF.

Connect

the

power

supply

where

indicated

in

Figure

2.

Plug

the

other

end

into

an

electrical

outlet.

Don't

turn

the

power

on

yet.

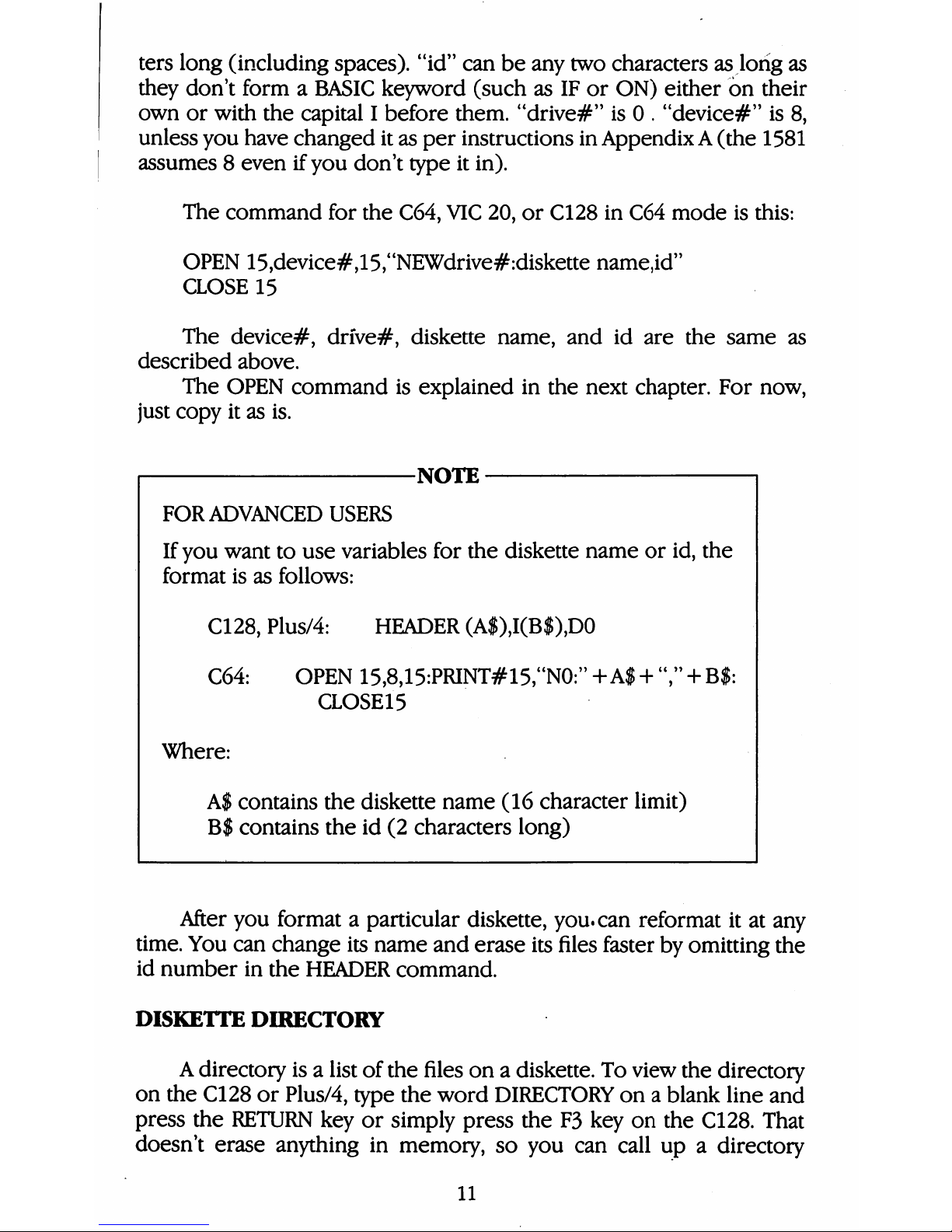

Figure2.ConnectionofPower

Cord

and

Interface

Cablesto1581

BACK

OF

C128

SERIAL

PORT

CONNECTOR

ON

C128

POWER

CORD

SOCKET

BACK

OF

1581

SERIAL

PORT

CONNECTORS

FOR

INTERFACE

CABLES

DIP

SWITCHES

FOR

CHANGING

DEVICE

NUMBER

ON/OFF

SWITCH

POWER

OUTLET

Page 14

5.

Connect

the

interface

cable.

Make

sure

your

computer

and

any

other

peripherals

are

OFF.

Plug

either

end

of

the

interface

cable

into

either

serial

port

on

the

back

of

the

drive

(see

Figure

2).

Plug

the

other

end

of

the

cable

into

the

back

of

the

computer.

If

you

have

another

peripheral

(printer

or

extra

drive),

plug

its

interface

cable

into

the

remaining

serial

port

on

the

drive.

6.

Turn

ON

the

power.

With

everything

hooked

up

and

the

drive

empty,

you

can

turn

on

the

power

to

the

peripherals

in

any

order,

but

turn

on

the

power

to

the

computer

lasfe

When

everything

is

on,

the

drive

goes

through

a

self

test.

If

all

is

well,

the

green

light

will

flash

once

and

the

red

power-on

light

will

glow

continuously.

If

the

red

light

continues

to

flash,

there

may

beaproblem.

In

that

case,

refer

to

the

Trouble

shooting

Guide.

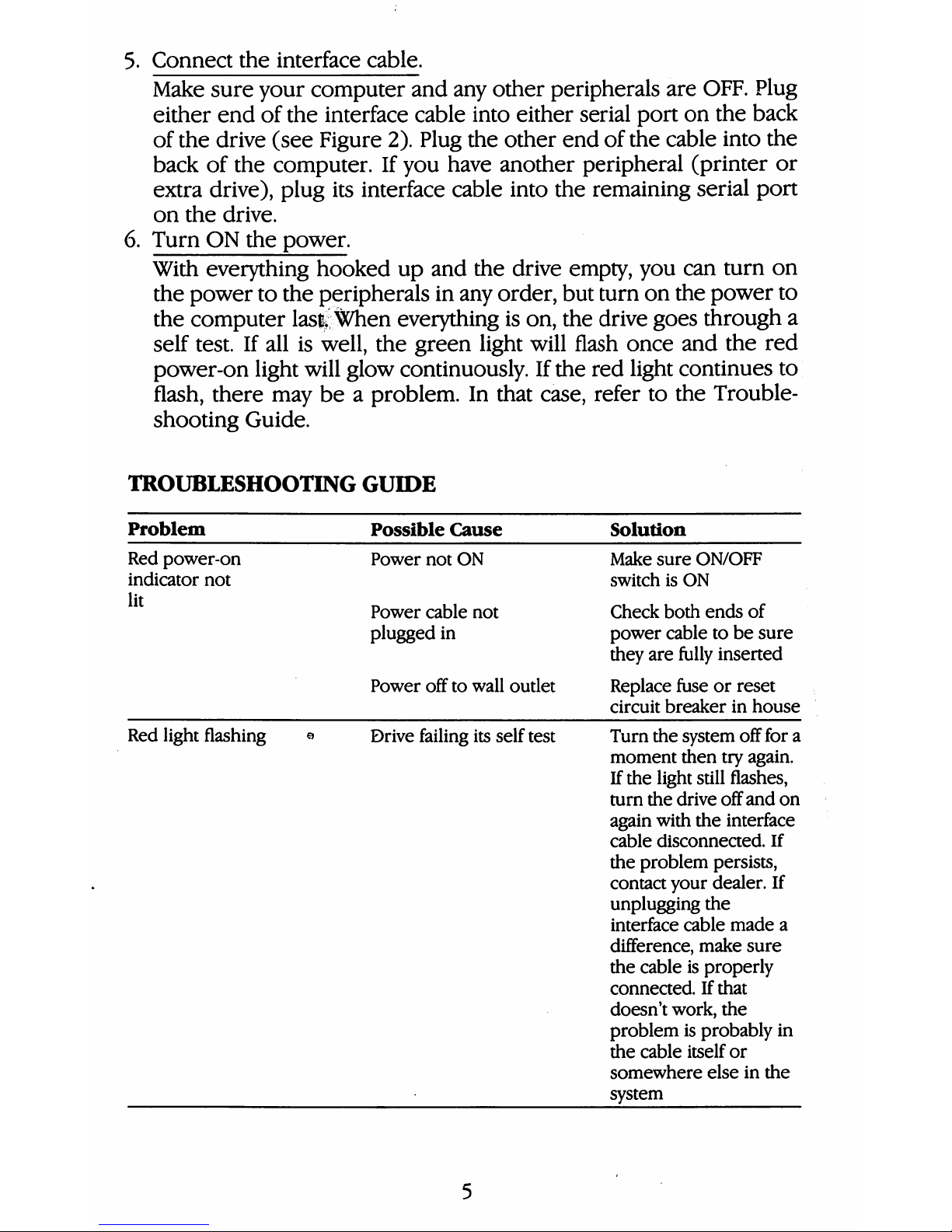

TROUBLESHOOTING

GUIDE

Problem

Red

power-on

indicator

not

lit

Red

light

flashing

e

Possible

Cause

Power

not

ON

Power

cable

not

plugged

in

Power

offtowall

outlet

Drive

failing

its

self

test

Solution

Make

sure

ON/OFF

switchisON

Check

both

ends

of

power

cabletobe

sure

they

are

fully

inserted

Replace

fuseorreset

circuit

breakerinhouse

Turn

the

system

off

for

a

moment

then

try

again.

If

the

light

still

flashes,

turn

the

drive

off

and

on

again

with

the

interface

cable

disconnected.

If

the

problem

persists,

contact

your

dealer.

If

unplugging

the

interface

cable

made

a

difference,

make

sure

the

cableisproperly

connectedIfthat

doesn't

work,

the

problemisprobably

in

the

cable

itself

or

somewhere

elseinthe

system

Page 15

TROUBLESHOOTING

GUIDE

(Cont.)

Programs

won't

load

and

the

computer

says

"DEVICE

NOT

PRESENT

ERROR"

Programs

won't

load,

but

the

computer

and

disk

drive

givenoerror

message

Interface

cable

not

well

connectedordrive

not

ON

Switchesonback

of

drive

may

notbeset

for

correct

device

number

Another

panofthe

system

may

be

interfering

Be

sure

the

cable

is

properly

connected

and

the

driveisON

Check

AppendixAfor

correct

settingtomatch

LOAD

command

Unplug

all

other

^machinesonthe

computer.Ifthat

cures

it,

plug

theminoneata

time.

The

one

just

added

when

the

trouble

repeatsismost

likely

the

problem

Tryingtoload

a

machine

language

program

into

BASIC

space

will

cause

this

problem

Programs

won't

load

and

red

light

flashes

Disk

error

Check

the

error

channel

to

determine

the

error,

then

follow

the

advice

in

AppendixBto

correct

it.

The

error

channel

is

explainedinChapters

2

and3

o

(Be

suretospell

program

names

correctly

and

include

the

exact

punctuation

when

loading

the

programs)

Your

programs

load

OK,

but

commercial

programs

and

those

from

other

1581s

don't

Either

the

diskette

is

faulty,oryour

disk

drive

is

misaligned

Try

another

copyofthe

program.Ifseveral

programs

from

several

sources

failtoload,

have

your

dealer*align

your

disk

drive

Your

programs

that

usedtoload,

won't

anymore,

but

programs

savedonnewly-

formatted

diskettes

will

Older

diskettes

have

been

damaged

The

disk

drive

has

gone

outofalignment

Recopy

from

backups

Have

your

dealer

align

your

disk

drive

Page 16

TIPS

FOR

MAINTENANCE

AND

CARE

1.

Keep

the

drive

well

ventilated.

A

couple

of

inches

of

space

to

allow

air

circulation

on

all

sides

will

prevent

heat

from

building

up

inside

the

drive.

2.

The

1581

should

be

cleaned

onceayear

in

normal

use.

Several

items

are

likely

to

need

attention:

the

two

read/write

heads

may

need

cleaning

(with

91%

isopropyl

alcohol

onacotton

swab).

Tjfcte

rails

along

which

the

head

moves

may

need

lubrication

(with

a

special

molybdenum

lubricant,

not

oil),

and

the

write

protect

sen

sor

may

need

to

be

dusted.

Since

these

chores

require

special

materials

or

parts,

it

is

best

to

leave

the

work

to

an

authorized

Commodore

service

center.

If

you

want

to

do

the

work

yourself,

ask

your

dealer

for

the

appropriate

materials.

IMPORTANT:

Home

repair

of

the

1581

will

void

your

warranty.

3.

Use

good

quality

diskettes.

Badly-made

diskettes

can

cause

increased

wear

on

the

drive's

read/

write

head.

If

you're

usingadiskette

that

is

unusually

noisy,

it

could

be

causing

added wear

and

should

be

replaced.

4.

Keep

diskettes

(and

disk

drive)

away from

magnets.

That

includes

the

electromagnets

in

telephones,

televisions,

desk

lamps,

and

calculator

cords.

Keep

smoke,

moisture,

dust,

and

food

off

the

diskettes.

5.

Removeadiskette

before

turning

the

drive

off.

If

you

don't,

you

might

lose

part

or

all

the

data

on

the

diskette.

6.

Don't

removeadiskette

from

the

drive

while

the

green

light

is

glowing

and

the

drive

motor

is

turning.

If

you

remove

the

diskette

then,

you

might

lose

the

information

currently

being

written

to

the

diskette.

Page 17

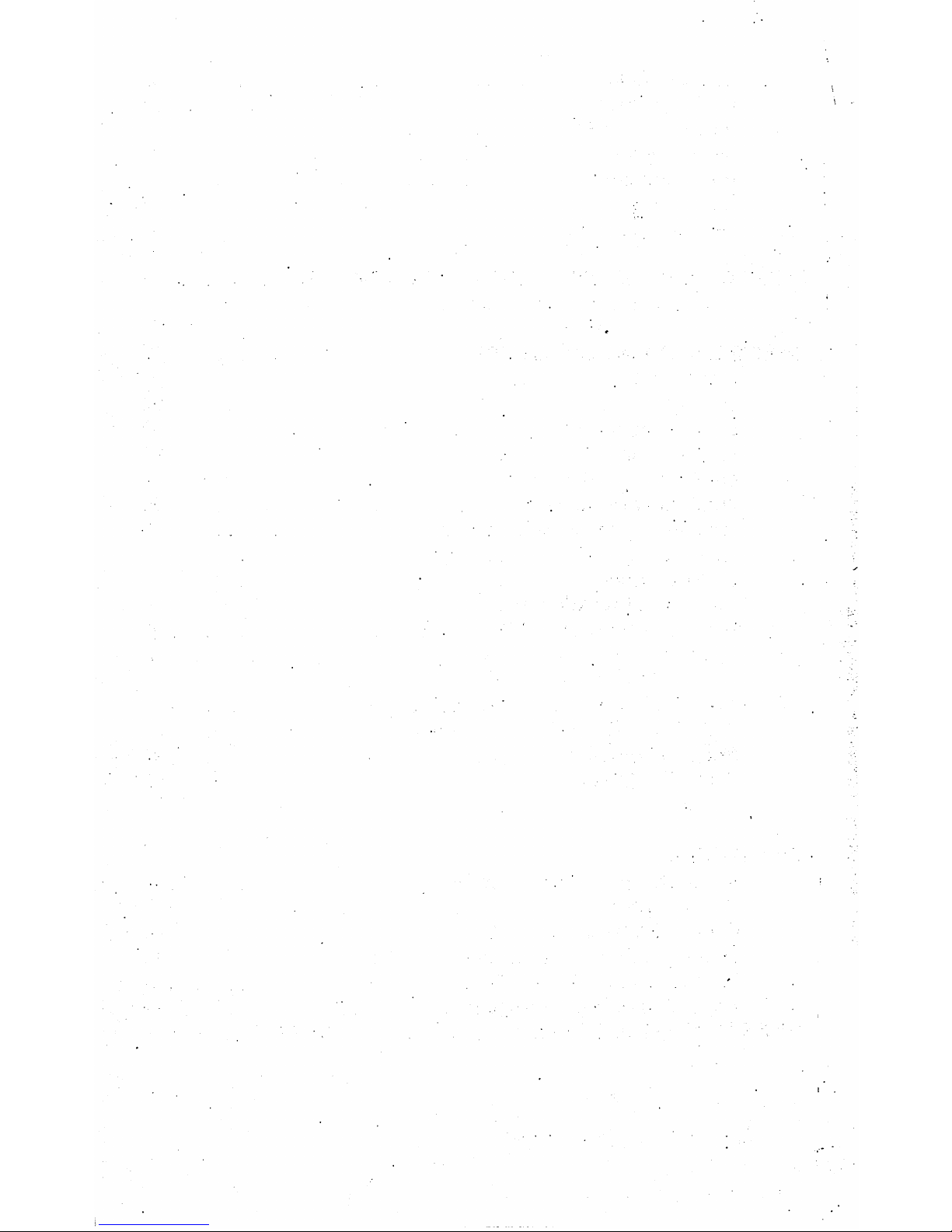

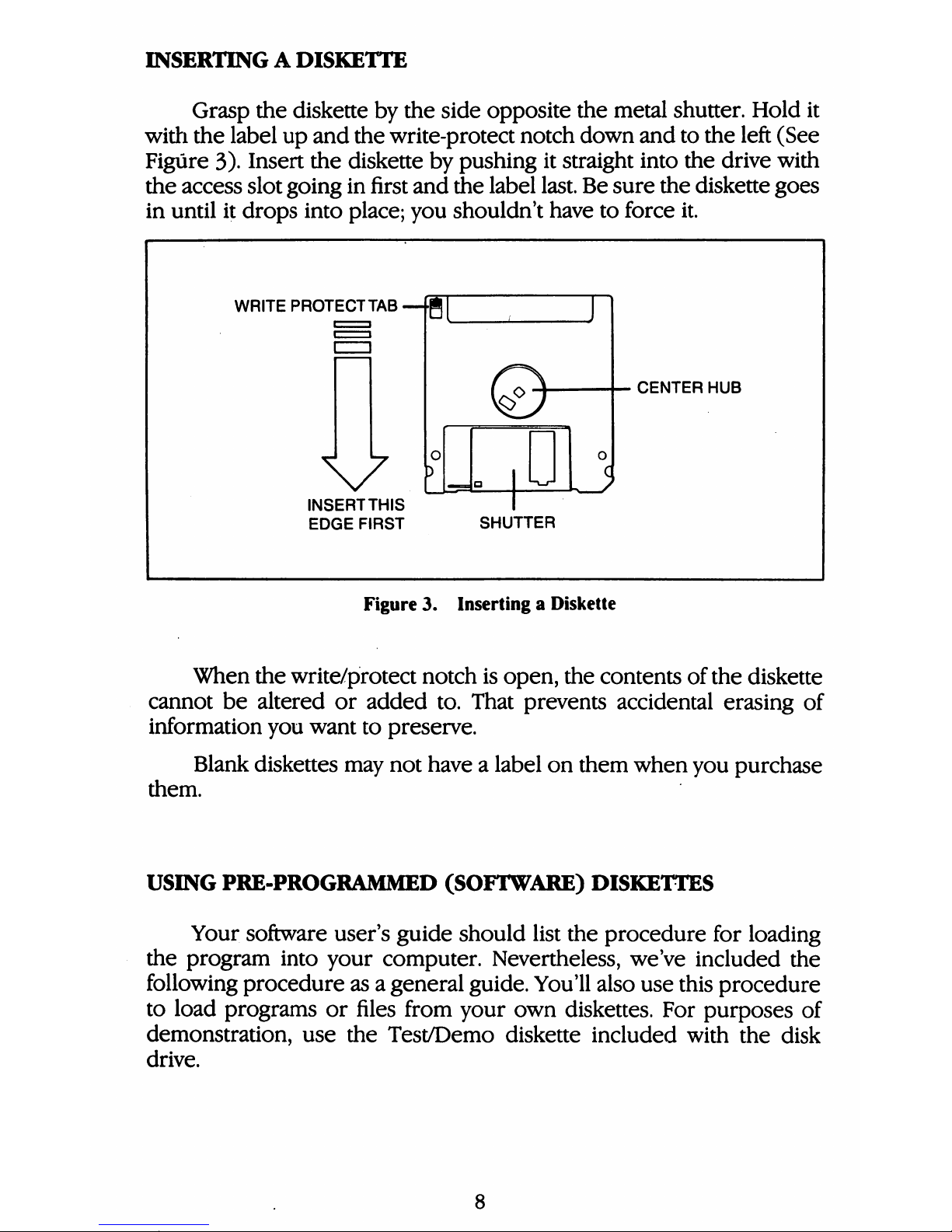

INSERTINGADISKETTE

Grasp

the

diskette

by

the

side

opposite

the

metal

shutter.

Hold

it

with

the

label

up

and

the

write-protect

notch

down

and

to

the

left

(See

Figure

3).

Insert

the

diskette

by

pushing

it

straight

into

the

drive

with

the

access

slot

going

in

first

and

the

label

last.

Be

sure

the

diskette

goes

in

until

it

drops

into

place;

you

shouldn't

have

to

force

it.

WRITE

PROTECT

TAB—g[

V

INSERTTHIS

EDGE

FIRST

.

CENTER

HUB

SHUTTER

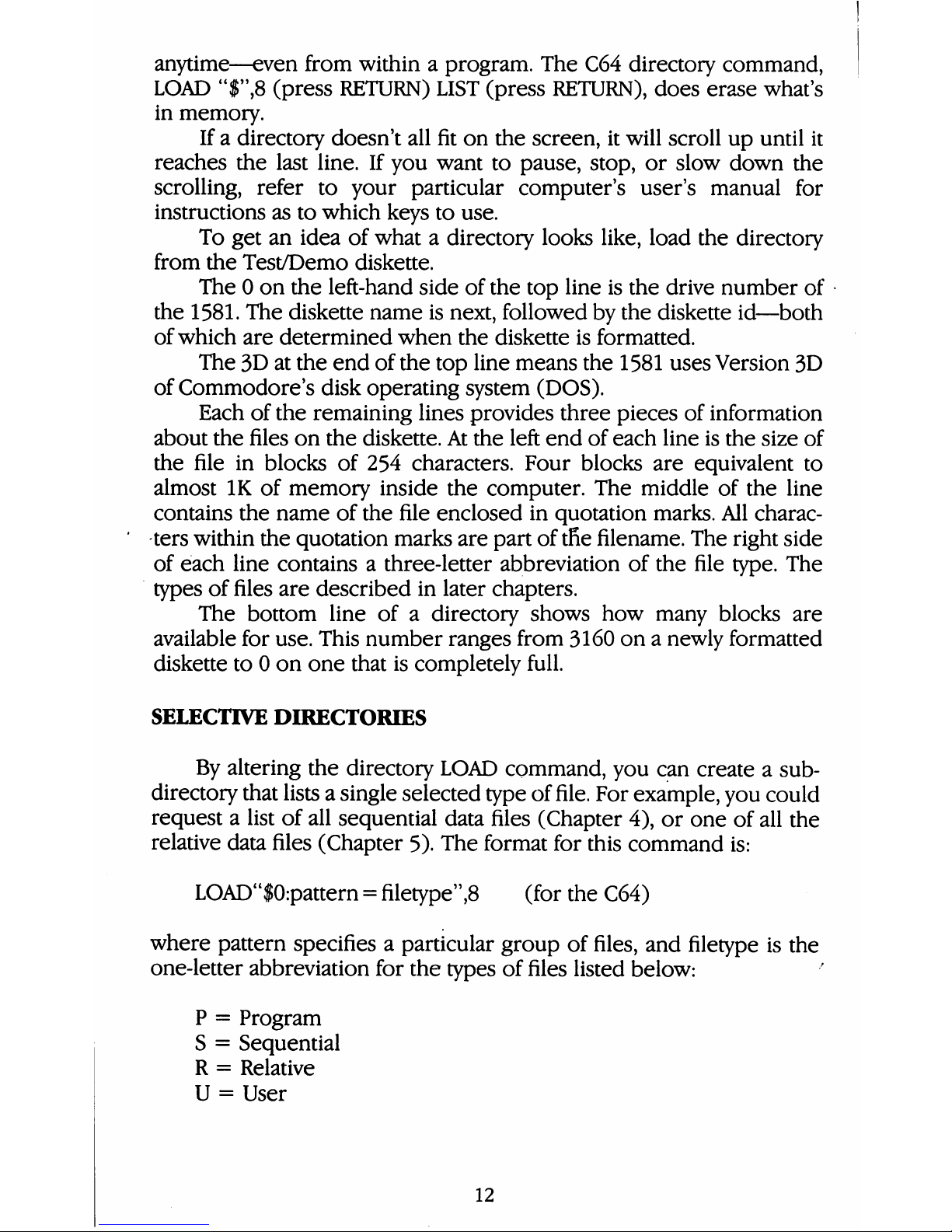

Figure3.Inserting

a

Diskette

When

the

write/protect

notch

is

open,

the

contents

of

the

diskette

cannot

be

altered

or

added

to.

That

prevents

accidental

erasing

of

information

you

want

to

preserve.

Blank

diskettes

may

not

havealabel

on

them

when

you

purchase

them.

USING

PRE-PROGRAMMED

(SOFTWARE)

DISKETTES

Your

software

user's

guide

should

list

the

procedure

for

loading

the

program

into

your

computer.

Nevertheless,

we've

included

the

following

procedure

asageneral

guide.

You'll

also

use

this

procedure

to

load

programs

or

files

from

your

own

diskettes.

For

purposes

of

demonstration,

use

the

Test/Demo

diskette

included

with

the

disk

drive.

Page 18

1.

Turn

on

system.

2.

Insert

diskette.

3.

If

you

are

usingaVIC

20,

Commodore

64,

oraCommodore

128

computer

in

C64

mode,

type:

LOAD

"HOW

TO

USE",8

If

you

are

usingaPlus/4

or

Commodore

128

in

C128

mode,

type:

DLOAD

"HOW

TO

USE"

4.

Press

the

RETURN

key.

5.

The

following

will

then

appear

on

the

screen:

SEARCHING

FOR

0:HOW

TO

USE

LOADING

READY

I

6.

Type:

RUN

7.

Press

the

RETURN

key.

To

loadadifferent

program

or

file,

simply

substitute

its

name

in

place

of

HOW

TO

USE

inside

the

quotation

marks.

-NOTE

The

HOW

TO

USE

program

is

the

key

to

the

Test/

Demo

diskette.

When

you

LOAD

and

RUN

it,

it

provides

instructions

for

using

the

rest

of

the

programs

on

the

dis

kette.

To

find

out

what

programs

are

on

your

Test/Demo

diskette,

refer

to

the

section

entitled

"DIRECTORIES"

later

in

this

chapter.

Ifaprogram

doesn't

load

or

run

properly

using

the

above

meth

od,

it

may

be

that

it

isamachine

language

program.

But

unless

you'll

be

doing

advanced

programming,

you

need

not

know

anything

about

machine

language.

A

program's

user's

guide

should

tell

you

if

it

is

written

in

machine

language.

If

it

is,

or

if

you

are

having

trouble

loadingaparticular

program,

simply

adda;1

(comma

and

number

1)

at

the

end

of

the

command.

Page 19

NOTE

Throughout

this

manual,

when

the

format

foracom

mand

is

giv^n,

it

will

followaparticular

style.

Anything

that

is

capitalized

must

be

typed

in

exactly

as

it

is

shown

(these

commands

are

listed

in

capital

letters

for

style

purposes,

DO

NOT

use

the

SHIFT

key

when

entering

these

com

mands).

Anything

in

lower

case

is

more

or

lessadefinition

of

what

belongs

there.

Anything

in

brackets

is

optional.

For

instance,

in

the

format

for

the

HEADER

command

given

on

the

following

page,

the

word

HEADER,

the

capital

I

in

lid,

the

capitalDin

Ddrive#,

and

the

capitalUin

Ude*-

vice#

must

all

be

typed

in

as

is

(Ddrive#

and

Udevice#

are

optional).

On

the

other

hand,

diskette

name

tells

you

that

you

must

enteraname

for

the

diskette,

but

it

is

up

to

you

to

decide

what

that

name

will

be.

Also,

the

id in

lid

is

left

to

your

discretion,

as

is

the

device#

in

Udevice#.

The

drive#

in

Ddrive#

is

always0on

the

1581,

but

could

be0or1on

a

dual

disk

drive.

Be

aware,

however,

that

there

are

certain

limits

placed

on

what

you

can

use.

In

each

case,

those

limits

are

explained

immediately

following

the

format

(for

in

stance,

the

diskette

name

cannot

be

more

than

sixteen

characters

and

the

device#

is

usually

8).

Also

be

sure

to

type

in

all

punctuation

exactly

where

and

how

it

is

shown

in

the

format.

Finally,

press

the

RETURN

key

at

the

end

of

each

command.

HOW

TO

PREPAREANEW

DISKETTE

A

diskette

needsapattern

of

circular

magnetic

tracks

in

order

for

the

drive's

read/write

head

to

find

things

on

it.

This

pattern

is

not

on

your

diskettes

when

you

buy

them,

but

you

can use

the

HEADER

command

or

the

NEW

command

to

add

it

toadiskette.

That

is

known

as

formatting

the

disk.

This

is

the

command

to

use

with

the

C128

in

C128

mode

or

Plus/4:

HEADER

"diskette

name",Iid,Ddrive#[,Udevice#]

Where:

"diskette

name"

is

any

desired

name

for

the

diskette,

up

to

16

charac-

10

Page 20

ters

long

(including

spaces),

"id"

can

be

any

two

characters

as

long

as

they

don't

formaBASIC

keyword

(such

as

IF

or

ON)

either

on

their

own

or

with

the

capital

I

before

them.

"drive#"

is0.

"device#"

is

8,

unless

you

have

changed

it

as

per

instructions

in

AppendixA(the

1581

assumes8even

if

you

don't

type

it

in).

The

command

for

the

C64,

VIC

20,

or

C128

in

C64

mode

is

this:

OPEN

15,device#,15,"NEWdrive#:diskette

name,id"

CLOSE

15

The

device#,

drive#,

diskette

name,

and

id

are

the

same

as

described

above.

The

OPEN

command

is

explained

in

the

next

chapter.

For

now,

just

copy

it

as

is.

-NOTE

FOR

ADVANCED

USERS

If

you

want

to

use

variables

for

the

diskette

name

or

id,

the

format

is

as

follows:

C128,

Plus/4:

HEADER

(A$),I(B$),D0

C64:

OPEN

15,8,15:PRINT#15,"N0:"

+A$+","+B$:

CLOSE15

Where:

A$

contains

the

diskette

name

(16

character

limit)

B$

contains

the

id

(2

characters

long)

After

you

formataparticular

diskette,

you.

can

reformat

it

at

any

time.

You

can

change

its

name

and

erase

its

files

faster

by

omitting

the

id

number

in

the

HEADER

command.

DISKETTE

DIRECTORY

A

directory

isalist

of

the

files

onadiskette.

To

view

the

directory

on

the

C128

or

Plus/4,

type

the

word

DIRECTORY

onablank

line

and

press

the

RETURN

key

or

simply

press

the

F3

key

on

the

C128.

That

doesn't

erase

anything

in

memory,

so

you

can

call

upadirectory

11

Page 21

anytime—even

from

withinaprogram.

The

C64

directory

command,

LOAD

"$",8

(press

RETURN)

LIST

(press

RETURN),

does

erase what's

in

memory.

Ifadirectory

doesn't

all

fit

on

the

screen,

it

will

scroll

up

until

it

reaches

the

last

line.

If

you

want

to

pause,

stop,

or

slow

down

the

scrolling,

refer

to

your

particular

computer's

user's

manual

for

instructions

as

to

which

keys

to

use.

To

get

an

idea

of

whatadirectory

looks

like,

load

the

directory

from

the

Test/Demo

diskette.

The0on

the

left-hand

side

of

the

top

line

is

the

drive

number

of

the

1581.

The

diskette

name

is

next,

followed

by

the

diskette

id—both

of

which

are

determined

when

the

diskette

is

formatted.

The

3D

at

the

end

of

the

top

line

means

the

1581

uses

Version

3D

of

Commodore's

disk

operating

system

(DOS).

Each

of

the

remaining

lines

provides

three

pieces

of

information

about

the

files

on

the

diskette.

At

the

left

end

of

each

line

is

the

size

of

the

file

in

blocks of

254

characters.

Four

blocks

are

equivalent

to

almost

IK

of

memory

inside

the

computer.

The

middle

of

the

line

contains

the

name

of

the

file

enclosed

in

quotation

marks.

All

charac

ters

within

the

quotation

marks

are

part

of

tfie

filename.

The

right

side

of

each

line

contains

a

three-letter

abbreviation

of

the

file

type.

The

types

of

files

are

described

in

later

chapters.

The

bottom

line

ofadirectory

shows

how

many

blocks

are

available

for

use.

This

number

ranges

from

3160

onanewly

formatted

diskette

to0on

one

that

is

completely

full.

SELECTIVE

DIRECTORIES

By

altering

the

directory

LOAD

command,

you

can

createasub

directory

that

lists

a

single

selected

type

of

file.

For

example,

you

could

requestalist

of

all

sequential

data

files

(Chapter

4),

or

one

of

all

the

relative

data

files

(Chapter

5).

The

format

for

this

command

is:

LOAD"$0:pattern

=

filetype",8

(for

the

C64)

where

pattern

specifies

a

particular

group

of

files,

and

filetype

is

the

one-letter

abbreviation

for

the

types

of

files

listed

below:

P=Program

S=Sequential

R=Relative

U

=

User

12

Page 22

The

command

for

the

C128

and

Plus/4

is

this:

DIRECTORY"pattern

=

filetype"

Some

examples:

LOAD"$0:*

=

R",8

and

DIRECTORY"*

=

R"

display

all

relative

files.

LOAD"$0:Z*

=

R",8

and

DIRECTORY"Z*

=

R"

display

a

sub-directo

ry

consisting

of

all

relative

files

that

start

with

the

letterZ(the

asterisk

(*)

is

explained

in

the

section

entitled

"Pattern

Matching."

PRINTINGADIRECTORY

To

printout

a

directory,

use

the

following:

LOAD'T',8

OPEN4,4:CMD4:LIST

PRINT#4:CLOSE4

PATTERN

MATCHING

You

can

use

special

pattern-matching

characters

to

loadapro

gram

fromapartial

name

or

to

provide

the

selective

directories

described

earlier.

The

two

characters

used

in

pattern

matching

are

the

asterisk

(*)

and

the

question

mark

(?).

They

act

something

likeawild

card

in

a

game

of

cards.

The

difference

between

the

two

is

that

the

asterisk

makes

all

characters

in

and

beyond

its

position

wild,

while

the

ques

tion

mark

makes

only

its

own

position

wild.

Here

are

some

examples

and

their

results:

LOAD

"A*",8

loads the

first

file

on

disk

that

begins

with

an

A,

regardless

of

what

follows

DLOAD"SM?TH"

loads

the

first

file

that

starts

with

SM,

ends

with

TH,

and

one

other

character

between

DIRECTORY"Q*"

loadsadirectory

of

files

whose

names

begin

withQ

LOAD"*",8

isaspecial

case.

When

an

asterisk

is

used

alone

as

a

name,

it

matches

the

last

file

used

(on

the

C64

and

C128

in

C64

mode).

13

Page 23

LOAD

"0:*",8

loads the

first

file

on

the

diskette

(C64

and

C128

in

C64

mode).

DLOAD

"*"

loads

the

first

file

on

the

diskette

(Plus/4

and

C128

in

C128

mode).

SPIAT

FILES

One

indicator

you

may

occasionally

notice

onadirectory

line,

after

you

begin

saving

programs

and

files,

is

an

asterisk

appearing

just

before

the

file

type

ofafile

that

is0blocks

long.

This

indicates

the

file

was

not

properly

closed

after

it

was

created,

and

that

it

should

not

be

relied

upon.

These

"splat"

files

normally

need

to

be

erased

from

the

diskette

and

rewritten.

However,

do

not

use

the

SCRATCH

command

to

get

rid

of

them.

They

can

only

be

safely

erased

by

the

VALIDATE

or

COLLECT

commands.

One

of

these

should

normally

be

used

when

everasplat

file

is

noticed

onadiskette.

All

of

these

commands

are

described

in

the

following

chapters.

There

are

two

exceptions

to

the

above

warning:

one

is

that

VALIDATE

and

COLLECT

cannot

be

used

on

some

diskettes

that

in

clude

direct

access

(random)

files

(Chapter

6).

The

other

is

that

if

the

information

in

the

splat

file

was

crucial

and

can't

be

replaced,

there

is

a

way

to

rescue

whatever

part

of

the

file

was

properly

written.

This

option

is

described

in

the

next

chapter.

14

Page 24

CHAPTER

2

BASIC

2.0

COMMANDS

This

chapter

describes

the

disk

commands

used

with

the

VIC

20,

Commodore

64

or

the

Commodore

128

computer

in

C64

mode.

These

are

Basic

2.0

commands.

You

send

command

data

to

the

drive

through

something

called

the

command

channel.

The

first

step

is

to

open

the

channel

with

the

following

command:

OPEN15,8,15

The

first

15

isafile

number

or

channel

number.

Although

it

could

be

any

number

from1to

255,

we'll

use

15

because

it

is

used

to

match

the

secondary

address

of

15,

which

is

the

address

of

the

command

channel.

The

middle

number

is

the

primary

address,

better

known

as

the

device

number.

It

is

usually

8,

unless

you

change

it

(see

Appendix

A).

Once

the

channel

has

been

opened,

use

the

PRINT#

command

to

send

information

to

the

disk

drive

and

the

INPUT#

command

to

receive

information

from

the

drive.

You

must

close

the

channel

with

the

CLOSE15

command.

The

following

examples

show

the

use

of

the

command

channel

to

NEW

an

unformatted

disk:

OPEN15,8,15

PRINT#15,"NEWdrive#:diskname,id"

CLOSE15

You

can

combine

the

first

two

statements

and

abbreviate

the

NEW

command

like

this:

OPEN15,8,15,"Ndrive#

:diskname,id"

If

the

command

channel

is

already

open,

you

must

use

the

following

format

(trying

to

openachannel

that

is

already

open

results

ina"FILE

OPEN"

error):

PRINT#15,uNdrive#:diskname,id"

15

Page 25

ERROR

CHECKING

In

Basic

2.0,

when

the

red

drive

light

flashes,

you

must

write

a

small

program

to

find

out

what

the

error

is.

This

causes

you

to

lose

any

program

variables

already

in

memory.

The

following

is

the

error

check

program:

10OPEN15,8,15

20

INPUT#15,EN,EM$,ET,ES

30

PRINT

EN,

EM$,ET,ES

40

CLOSE15

This

little

program

reads

the

error

channel

into

four

BASIC

variables

(described below),

and

prints

the

results

on

the

screen.

A

message

is

displayed

whether

there

is

an

error

or

not,

but

if

there

was

an

error,

the

program

clears

it

from

disk

memory

and

stops

the

error

light

from

blinking.

Once

the

message

is

on

the

screen,

you

can

look

it

up

in

Appen

dixBto

see

what

it

means,

and

what

to

do

about

it.

For

those

of

you

who

are

writing

programs,

the

following

is

a

small

error-checking

subroutine

you

can

include

in

your

programs:

59980

REM

READ

ERROR

CHANNEL

59990

INPUT#15,EN,EM$,ET,ES

60000

IF

EN>1

THEN

PRINT

EN,EM$,ET,ES:STOP

60010

RETURN

This

assumes

file

15

was

opened

earlier

in

the

program,

and

that

it

will

be

closed

at

the

end

of

the

program.

The

subroutine

reads

the

error

channel

and

puts

the

results

into

the

named

variables—EN

(Error

Number),

EM$

(Error

Message),

ET

(Error

Track),

and

ES

(Error

Sector).

Of

the

four,

only

EM$

has

to

be

a

string.

You

could

choose

other

variable

names,

although

these

have

become

traditional

for

this

use.

Two

error

numbers

are

harmless—0

means

everything

is

OK,

and

1

tells

how

many

files

were

erased

byaSCRATCH

command

(de

scribed

later

in

this

chapter).

If

the

error

status

is

anything

else,

line

60000

prints

the

error

message

and

halts

the

program.

Because

this

isasubroutine,

you

access

it

with

the

BASIC

GOSUB

command,

either

in

immediate

mode

or

fromaprogram.

The

RETURN

statement

in

line

60010

will

jump

back

to

immediate

mode

or

the

next

statement

in

your

program,

whichever

is

appropriate.

16

Page 26

BASIC

HINTS

h

It

is

best

to

open

file

15

once

at

the

very

start

ofaprogram,

and

only

close

it

at

the

end

of

the

program,

after

all

other

files

have

already

been

closed.

By

opening

it

once

at

the

start,

the

file

is

open

whenever

needed

for

disk

commands

elsewhere

in

the

program.

2.

If

BASIC

halts

with

an

error

when

you

have

files

open,

BASIC

aborts

them

without

closing

them

properly

on

the

disk.

To

close

them

properly

on

the

disk,

you

must

type:

CLOSE

15:OPEN

15,8,15,'T':CLOSE

15

This

opens

the

command

channel

and

immediately

closes

it,

along

with

all

other

disk

files.

Failure

to

closeadisk

file

properly

both*

in

BASIC and

on

the

disk

may

result

in

losing

the

entire

file.

3.

One

disk

error

message

is

not

always

an

error.

Error

73,

"COPY

RIGHT

CBM DOS

V10

1581"

will

appear

if

you

read

the

disk

error

channel

before

sending

any

disk

commands

when

you

turn

on

your

computer.

This

isahandy

way

to

check

which

version

of

DOS

you

are

using.

However,

if

this

message

appears

later,

after

other

disk

com

mands,

it

means

there

isamismatch

between

the

DOS

used

to

format

your

diskette

and

the

DOS

in

your

drive.

DOS

is

Disk

Operating

System.

4.

To

reset

drive,

type:

OPEN

15,8,15,"UJ":CLOSE

15.

SAVE

The

SAVE

command

preserves

a

program

or

file

onaformatted

diskette

for

later

use.

FORMAT FOR

THE

SAVE

COMMAND

SAVE

"drive

#:file

name",device

#

where

"file

name"

is

any

string

expression

of

up

to

16

characters,

preceded by

the

drive

number

andacolon,

and

followed

by

the

device

number

of

the

disk,

normally

8.

However,

the

SAVE

command

will

not

work

in

copying

programs

that

are

not

in

the

BASIC

text

area,

such

as

"DOS

5.1"

for

the

C64.

To

copy

it

and

similar

machine-language

programs,

you

will

need

a

machine-language

monitor

program,

such

as

the

one

resident

in

the

C128.

17

Page 27

FORMAT FORAMONITOR

SAVE

S "drive

#:file

name",device

#,starting

address,ending

ad

dress

+1

where

"drive

#:"

is

the

drive

number,0on

the

1581;

"file

name"

is

any

valid

file

name

up

to

14

characters

long

(leaving

two

for

the

drive

number

and

colon);

"device

#"

isatwo

digit

device

number,

normally

08

(the

leading0is

required);

and

the

addresses

to

be

saved

are

given

in

Hexadecimal

but

withoutaleading

dollar

sign

($).

Note

the

ending

address

listed

must

be

one

location

beyond

the

last

location

to

be

saved.

EXAMPLE:

Here

is

the

required

syntax

to

SAVEacopy

of

"DOS

5.1"

S

"0:DOS

5.r,08,CC00,D000

SAVE

WITH

REPLACE

Ifafile

already

exists,

it

can't

be

saved

again

with

the

same

name

because

the

disk

drive

only

allows

one

copy

of

any

given

file

name

per

diskette.

It is

possible

to

get

around

this

problem

using

the

RENAME

and

SCRATCH

commands

described

later.

However,

if

all

you

wish

to

do

is

replaceaprogram

or

data

file

witharevised

version,

another

command

is

more

convenient.

Known

as

SAVE-WITH-REPLACE,

or

@SAVE,

this

option

tells

the

disk

drive

to

replace

any

file

it

finds

in

the

diskette

directory

with

the

same

name,

substituting

the

new

file

for

the

old

version.

FORMAT

FOR

SAVE

WITH

REPLACE:

SAVE"@Drive

#:file

name",

device

#

where

all

the

parameters

are

as

usual

except

for

addingaleading

"at"

sign

(@.)

The

"drive

#:"

is

required

here.

EXAMPLE:

SAVE"@0:REVISED

PROGRAM",8

The

actual

procedure

is

that

the

new

version

is

saved

completely,

then

the

old

version

is

erased.

Because

it

works

this

way,

there

is little

18

Page 28

dangeradisaster

such

as

losing

power

midway

through

the

process

would

destroy

both

the

old

and

hew

copies

of

the

file.

Nothing

happens

to

the

old

copy

until

after

the

new

copy

is

saved

properly.

VERIFY

The

VERIFY

command

can

be

used

to

make

certain

thatapro

gram

file

was

properly

saved

to

disk.

It

works

much

like

the

LOAD

command,

except

that

it

only

compares

each

character

in

the

program

against

the

equivalent

character

in

the

computer's

memory,

instead

of

actually

being

copied

into

memory.

If

the

disk

copy

of

the

program

differs

evenatiny

bit

from

the

copy

in

memory,

"VERIFY

ERROR"

will

be

displayed,

to

tell

you

that

the

copies

differ.

This

doesn't

mean

either

copy

is

bad,

but

if

they

were

supposed

to

be

identical,

there

isaproblem.

Naturally,

there's

no

point

in

trying

to

VERIFYadisk

copy,

of

a

program

after

the

original

is

no

longer

in

memory.

With

nothing

to

compare

to,

an

apparent

error

will

always

be

announced,

even

though

the disk

copy

is

automatically

verified

as

it

is

written

to

the

diskette.

FORMAT

FOR THE

VERIFY

COMMAND:

VERIFY

"drive#:pattern",device#,relocate

flag

where

"drive#:"

is

an

optional

drive

number,

"pattern".is

any

string

expression

that

evaluates

toafile

name,

with

or

without

pattern-

matching

characters,

and

"device#"

is

the

disk

device

number,

nor

mally

8.

If

the

relocate

flag

is

present

and

equals

1,

the

file

will

be

verified

where

originally

saved,

rather

than

relocated

into

the

BASIC

text

area.

A

useful

alternate

form

of

the

command

is:

VERIFY"*",device

#

It

verifies

the

last

files

used

without

having

to

type

its

name

or

drive

number.

However,

it

won't

work

properly

after

SAVE-WITH-REPLACE,

because

the

last

file

used

was

the

one

deleted,

and

the

drive

will

try

to

compare

the

deleted

file

to

the

program

in

memory.

No

harm

will

result,

but

"VERIFY

ERROR"

will

always

be

announced.

To

use

VERIFY

after

@SAVE,

include

at

least

part

of

the

file

name

that

is

to

be

verified

in

the

pattern.

19

Page 29

One

other

note

about

VERIFY—when

you

VERIFYarelocated

BASIC

file,

an

error

will

nearly

always

be

announced,

due

to

changes

in

the

link

pointers

of

BASIC

programs

made

during

relocation.

It

is

best

to

VERIFY

files

saved

from

the

same

type

of

machine,

and

identi

cal

memory

size.

For

example,

a

BASIC

program

saved

fromaPlus/4

can't

be

verified

easily

withaC64,

even

when

the

program

would

work

fine

on

both

machines.

This

shouldn't

matter,

as

the

only

time

you'll

be

verifying

files

on

machines

other

than

the

one

which

wrote

them

is

when

you

are

comparing

two

disk

files

to

see

if

they

are

the

same.

This

is

done

by

loading

one

and

verifying

against

the

other,

and

can

only

be

done

on

the

same

machine

and

memory

size

as

the

one

on

which

the

files

were

first

created.

SCRATCH

The

SCRATCH

command

allows

you

to

erase

unwanted

files

and

free

the

space

they

occupied

for

use

by

other

files.

It

can

be

used

to

erase

eitherasingle

file

or

several

files

at

once

via

pattern-matching.

FORMAT

FOR

THE

SCRATCH

COMMAND:

PRINT#15,"SCRATCH0:pattern"

or

abbreviate

it

as:

PRINT#15,"S0:pattern"

"pattern"

can

be

any

file

name

or

combination

of

characters

and

wild

card

characters.

As

usual,

it

is

assumed

the

command

channel

has

already

been

opened

as

file

15.

Although

not

absolutely

necessary,

it

is

best

to

include

the

drive

number

in

SCRATCH

commands.

If

you

check

the

error

channel

afteraSCRATCH

command,

the

value

for

ET

(error

track)

will

tell

you

how

many

files

were

scratched.

For

example,

if

your

diskette

contains

program

ftles

named

"TEST,"

"TRAIN,"

"TRUCK,"

and

"TAIL,"

you

may

SCRATCH

all

four,

along

with

any

other

files

beginning

with

the

letter

"T,"

by

using

the

command:

PRINT#15/S0:T*'

Then,

to

prove

they

are

gone,

you

can

type:

GOSUB

59990

20

Page 30

to

call

the

error

checking

subroutine

given

earlier

in

this

chapter.

If

the

four

listed

were

the

only

files

beginning

with

"T",

you

will see:

01,FILES

SCRATCHED,04,00

READY.

The

"04"

tells

you4files

were

scratched.

MORE

ABOUT

SCRATCH

SCRATCH

isapowerful

command

and

should

be

used

with

caution

to

be

sure

you

delete

only

the

files

you

really

want

erased.

When

using

it

withapattern,

we

suggest

you

first

use

the

same

pattern

inaDIRECTORY

command,

to

be

sure

exactly

which

files

will

be

deleted.

That

way

you'll

have

no

unpleasant

surprises

when

you

use

the

same

pattern

in

the

SCRATCH

command.

If

you

accidentally

SCRATCHafile

you

shouldn't

have,

there

is

stillachance

of

saving

it

by

using

the

"Unscratch"

program

on

your

Test/Demo

diskette.

More

about

Splats

Never

scratch a

splat

file.

These

are

files

that

show

up

in

a

directory

listing

with

an

asterisk

(*)

just

before

the

file

type

for

an

entry.

The

asterisk

(or

splat)

means

that

file

was

never,

properly

closed,

and

thus

there

is

no

valid

chain

of

sector

links

for

the

SCRATCH

command

to

follow

in

erasing the

file.

If

you

SCRATCH

suchafile,

odds

are

you

will

improperly

free

up

sectors

that

are

still

needed

by

other

programs

or

files

and

cause

permanent

damage

to

those

later

when

you

add

more

files

to

the

diskette.

If

you

findasplat

file,

or

if

you

discover

too

late

that

you

have

scratched

suchafile,

immediately

validate

the

diskette

using

the

VALIDATE

command

described

later

in

this

chapter.

If

you

have

added

any

files

to

the

diskette

since

scratching

the

splat

file,

it

is

best

.to

immediately

copy

the

entire

diskette

onto

another

fresh

diskette,

but

do

this

withacopy

program

rather

than

withabackup

programs

Otherwise,

the

same

problem

will

be

recreated

on

the

new

diskette.

When

the

new

copy

is

done,

compare

the

number

of

blocks

free

in

its

directory

to

the

number

free

on

the

original

diskette.

If

the

numbers

match,

no

damage

has

been

done.

If

not,

very

likely

at

least

one

file

on

the

diskette

has

been

corrupted,

and

all

should

be

checked

immedi

ately.

21

Page 31

Locked

Files

Occasionally,

a

diskette

will

containalocked

file;

one

which

cannot

be

erased

with

the

SCRATCH

command.

Such

files

may

be

recognized

by

the

"<"

character

which

immediately

follows

the

file

type

in

their

directory

entry.

If

you

wish

to

erase a

locked

file,

you

will

have

to

useasector

editor

program

to

clear

bit6of

the

file-type

byte

in

the

directory

entry

on

the

diskette.

Conversely,

to

lockafile,

you

would

set

bit6of

the

same

byte.

RENAME

The

RENAME

command

allows

you

to

alter

the

name

ofaprogram

or

other

file

in

the

diskette

directory.

Since

only

the

directory

is

affected,

RENAME

works

very

quickly.

FORMAT

FOR

RENAME

COMMAND:

PRINT#15,"RENAME0:new

name=old

name"

or

it

may

be

abbreviated

as:

PRINT#15,"R0:new

name=old

name"

where

"new

name"

is

the

name

you

want

the

file

to

have,

and

"old

name"

is

the

name

it

has

now.

"new name"

may

be

any

valid

file

name,

up

to

16

characters

in

length.

It

is

assumed

you

have

already

opened

file

15

to

the

command

channel.

One

caution—be

sure

the

file

you

are

renaming

has

been

proper

ly

closed

before

you

rename

it.

EXAMPLES:

Just

before

saving a

new

copy

ofa"calendar"