Page 1

COMMODORE

0

DISK

DRIVE

useris

guide

Page 2

Page 3

COMIVIODORE

1541-H

DISK

DRIVE

USER'S

GUIDE

ft

commodore

COMPUTERS

Page 4

The

information

in

this

manual

has

been

reviewed

andisbelieved

tobeentirely

reliable.

No

responsibility,

however,isassumed

for

inaccuracies.

The

material

in

this

manual

is

for

information

purposes

only,

and

may

be changed

without

notice.

©

Commodore

Electronics

Ltd.,

1986

"All

rights

reserved."

Page 5

TABLE

OF

CONTENTS

Introduction

1

The

advantages

ofadisk

drive

1

Featuresofthe

1541

1

Howtouse

this

book

2

Basic

Operating

Steps

2

Specifications

of

the

1541

Disk

Drive

4

PART

ONE:

GUIDETOOPERATION

Chapter1:Disk

Drive

5

Unpacking

.

5

Empty

the

drive

6

Connecting

the

cables

6

Turningonthe

power

7

Troubleshooting

guide

9

Simple

maintenance

tips

11

Chapter2:Diskettes

.

12

Whatisa

diskette?

12

Safety

rules

for

diskette

care

13

Inserting

a

diskette

13

Safety

rules

for

removing

diskettes

14

Loadingapackaged

program

14

Howtoprepareanew

diskette

15

Reusinganold

diskette

16

Organizing

a

diskette

library

17

Backups

17

Chapter3:Directories

18

Whatisa

directory?

....

18

Viewingadirectory

18

Whatadirectory

shows

18

Watch

out

for

splat

files

20

Printingadirectory

21

Readingadirectory

asafile

21

Another

waytobe

selective

21

Pattern

matching

and

wild

cards

22

Page 6

PART

TWO:

GUIDETOADVANCED

OPERATION

AND

PROGRAMMING

Chapter4:Commands

,

25

Command

Channel

25

Reading

the

Error

Channel

26

Housekeeping

hints.

«

28

Saving

programs

29

Save

with

replace

a

30

Verifying

programs

30

Erasing

programs

.

31

Scratch

for

advanced

users

33

Renaming

programs

34

Renaming

and

scratching

troublesome

programs

36

Copying

programs

37

Validating

the

diskette

38

Initializing

40

Chapter

5:

Sequential

Data

Files

42

The

conceptoffiles

42

Openingasequential

file

42

Addingtoa

sequential

file

45

Writing

file

data:

Print#

46

Closingafile

48

Reading

file

data

using

INPUT#

49

More

about

INPUT

(advanced)

50

Numeric

Data

StorageonDiskette

51

Reading

File

Data:

Using

GET#

,...

52

Demonstration

of

Sequential

Files

54

Chapter6:Relative

Data

Files

55

The

valueofrelative

access

55

Files,

Records,

and

Fields

55

File

limits

56

Creating

a

relative

file

56

Using

relative

files:

Record#

57

Completing

relative

file

creation

59

Expandingarelative

file

60

Writing

relative

file

data

61

Designing

a

relative

record

61

Writing

the

record

62

Readingarelative

record

63

The

valueofindex

files

64

Page 7

Chapter7:Direct

Access

Commands

65

A

tool

for

advanced

users

...

65

Diskette

organization

65

Openingadata channel 65

Block-Read

66

Block-Write

67

The

original

commands

68

The

buffer

pointer

.

69

Allocating

blocks

70

Freeing

blocks 71

Using

random

files

(advanced)

72

Chapter

8:

Internal

Disk

Commands

73

1541

Memory

Map

73

Memory

Read

..

74

Memory

Write

75

Memory

Execute

77

Block

Execute

77

User

commands

78

Chapter

9:

Machine

Language Programs

80

Disk-related

kernafl

subroutines

80

Appendices

A.

Changing

the

Device

Number

81

B.

Error

Messages

83

C.

Diskette

Formats

87

D.

Disk

Command

Quick

Reference

Chart

92

E.

Test/Demo

Diskette

'.

93

ListofFigures

1.

Front

Panel

5

2.

Back

Panel

6

3.

Floppy

Disk

Hookup

8

4.

Position for

Diskette

Insertion

12

Page 8

Page 9

INTRODUCTION

The

1541

disk

drive

greatly

increases

the

speed,

storage

capacity,

flexibility

and

reliabil

ityofyour

Commodore

computer.Asyou

use

the

1541

disk

drive,

you

will

appreciate

its

superiority

to

the

cassette

recorder

you

may

have

used

before

andtodisk

drives

offered

for

other

brandsofcomputers.

The

1541-n

disk

driveisfully

compatible

with

the

commodore

1541

disk

drive,

therefore

we

may

often

omit

the

"-II"

suffix

throughout

the

remainder

of

this

manual.

THE

ADVANTAGESOFA

DISK

DRIVE

•

Speed

If

you

have

usedacassette

recorder

for

data

storage,

you

probably

knowitcan

take

up

toanhour

justtosearch

one

long

cassette

tape

looking

foraspecific

program.

With

the

1541

disk

drive,alistofall

the

programsona

diskette

appearsonyour

screen

in

seconds.

The

speedofprogram

loadingisalso

greatly

improved.

It

takes

the

1541

only

a

minutetoloadalarge

program

that

would

takeahalf-hour

to

load

from

tape.

•

Reliability

Reliability

is

another

reason

for

choosingadisk

drive.Itis

all

too

common

foracassette

usertoaccidentally

eraseavaluable

programbysavinganew

programontopofthe

old

one,

without

realizing

it.

The

1541

disk

drive

automatically

verifies

everything

it

records.

•

Direct

File

Access

A

third

advantageofa

disk

driveisthe

abilitytouse

relative

files

(discussed

in

Chapter

6).Ona

diskette,

any

partofa

relative

file

canbeaccessed

and

altered

separately,

without

affecting

the

restofthe

file.

Overall,

usingadisk

drive

makes

for

easier

and

more

powerful

computing.

FEATURESOFTHE

1541

The

1541isoneofthe

most

affordable

disk

drivesonthe

market.

Compared

to

competitors,

the

1541

has high

capacity,

and

even

higher

intelligence.

Itisoneofthe

most

cost-effective

disk drives

available.

Most

home

and

personal

computers

that

useadisk

takeatleast

10KofRAM

memory

from

the

computertoholdadisk

operating

system

(knownasa

DOS.)

This

large

program

mustbein

memory

the

whole

time

the

disk

is

being

used,

and

muchofit

must

alsobekeptonevery

diskette.

The

Commodore

1541

works

differently

and

more

effectively.

It

contains

its

own

built-in

microcomputer

to

control

its

various

operations,

along

with

enough

ROM

and

RAM

memory

to

operate

without

any

help

from

the

computer.

Commodore's

DOS

"lives"

entirely

inside

the

disk

drive,

and

does

not

require

any

internal

memory

in

the

computer

to

do

its

work,

nor

does

it

have

to

be

loaded

before

use

like

DOS

on

other

computers.

It

is

so

independent

that

once

it

begins

working

onacommand,

it

will

complete

it

while

the

computer

goes

on

to

some

other

task,

effectively

allowing

you

to

do

two

thingsatonce.

Page 10

Another

key

advantage

of

the

Commodore

1541

over

disk

drives

for

other

computers

is

its

dynamic

allocation

of

disk

space.

Many

other

disk

drives

make

you

think

about

every

program

you

save.

Where

canIstore

it

on

this

diskette,

and

should

I

pack

the

disk

first?

(Packingisthe

processofmoving

all

the

leftover

work

areastothe

endofthe

diskette's

storage

space.)

All

thisishandled

automatically

on

Commodore

disk

drives.

The

1541

disk

drive

always

knows

where

the

next

program

will

go,

and

automatically

fits

it

into

the

best

available

spot.

Diskettes

created

on

the

1541

may

be

read

by

several

other

Commodore

disk

drives,

including

the

former

1540,

2040,

and

4040,

and

the

2031.

It

is

usually

possi

ble,

though

not

recommended,

to

write

data

to

any

one

of

these

drives

from

any

of

the

others.

The

1541

communicates

with

the

computer

and

other

devices

overacable

and

interface

knownasthe

Commodore

serial

bus.Itis

patterned

after

the

IEEE-488

bus

used

on

Commodore's

PET

and

CBM

models,

except

that

the

serial

version

only

uses

one

wire

for

data.

The

two

serial

ports

on

the

1541

allow

several

devices

to

be

connected

together

at

once,

each

plugged

into

the

next

in

*'daisy

chain"

fash

ion.Upto4disk

drives

and2printers

canbeconnected

this

way.

HOW

TO

USE

THIS

BOOK

This

bookisdivided

into

two

main

parts.

The

first

part

gives

you

the

information

you

needtouse

the

1541

effectively,

evenifyou

know

littleornothing

about

programming.

This

partofthe

book

tells

you

howtosetupthe

system,

howtoprepare

diskettes

for

use,

howtoreadadirectory,

and

howtoload

programs.

Part

twoofthe

bookisfor

advanced

users

and

those

who

would

liketobecome

advanced

users.

This

part

provides

more

advanced

commands,

tells

about

the

different

files

the

1541

uses,

and

howtomanage

them,aswellasgivingafew

hints

for

machine

language

programmers.

Both

beginning

and

advanced

users

will

find

valuable

information

in

the

appendi

ces—a

quick

reference

listofdisk

commands,alistofdisk

error

messages

and

what

they

mean,aglossaryofwords

usedinthis

manual,

howtouse

twoormore

disk

drives

at

once,

and

explanations

of

some

programsonthe

Test/Demo

diskette

packed

with

your

1541.

Since

ownersoffour

different

Commodore

computers

use

the

1541,wehave

separated

several

explanations

into

two

versions,

dependingonwhich

Basic

your

com

puter

uses.Ifyou

haveaVIC20or

Commodore

64,

please

read

the

pages

marked

Basic

2.

Those

with

the

Commodore16or

the

Plus/4

should

read

pages

marked

Basic

3.5.

For

many

commands,

there

will

be an

added

pageortwooffurther

comments

and

advanced

techniques.

Feel

free to

skip

anything

you

don't

understand

on

those

pages

now,

and

come

back

later.

BASIC

OPERATING

STEPS

If

you're

like

most

people,

you're

anxioustostart

using

your

new

disk

drive

(

right

away.Inviewofthat,wehave

outlined

the

basic

steps

you

needtoknow

in

ordertoget

started.

Page 11

Once

you've

mastered

the

basic

steps

however,

you

will

needtorefertothe

rest

of

this

manual

in

order

to

make

full

use

of

the

1541

*s

features.

In

fact,

before

you

begin,

you

should

takealookatthe

following

short

sections,

which

offer

precautions

on

handling

the

equipment:

"Simple

maintenance

tips,"

"Safety

rules

for

diskette

care,"

and

"Safety

rules

for

removing

diskettes."

1.

Unpack,

hook-up,

and

turnonthe

disk

drive.

There'snoshortcut

through

this

part.

You'll

havetoread

this

sectiontofind

out

what

connectstowhat,

whentoturn

everything

on,

and

howtoempty

the

drive.

If

you

run

into

any

problemsatthis

point,

refertothe

Troubleshooting

Guide.

Gently

insertapre-programmed

diskette.

For

the

purposeofdemonstration,

use

the

Test/Demo

diskette

that

was

included

with

the

disk

drive.

If

you

run

into

any

problemsatthis

point,

refertoChapter2,"Inserting

a

Diskette."

3.

Type:

LOAD

"HOW

TO

USE",8

(forBasic2)

DLOAD

"HOW

TO

USE"(for

Basic

3.5)

Press:

RETURN

HOW

TO

USE

is

the

name

ofaparticular

program

on

the

Text/Demo

diskette.

To

loadadifferent

BASIC

program,

substitute

the

name

of

that

program

inside

the

quotation

marks.

If

you

want

to

loadaprogram

that

isn't

written

in

BASIC

language,

you

must

use

the

Basic2command

and

add

the

following

after,the

8

in

that

command:

,1

If

you

run

into

any

problems

at

this

point,

refer

to

Chapter

2,

the

section

enti

tled

"LoadingaPackaged

Program."

4.

After

you

perform

step3,the

following

will

appearonthe

screen:

SEARCHING

FOR

HOW

TO

USE

LOADING

READY

At

this

point,

type

RUN

and

press

the

RETURN

key

and

follow

the

directions

for

the

program.

Page 12

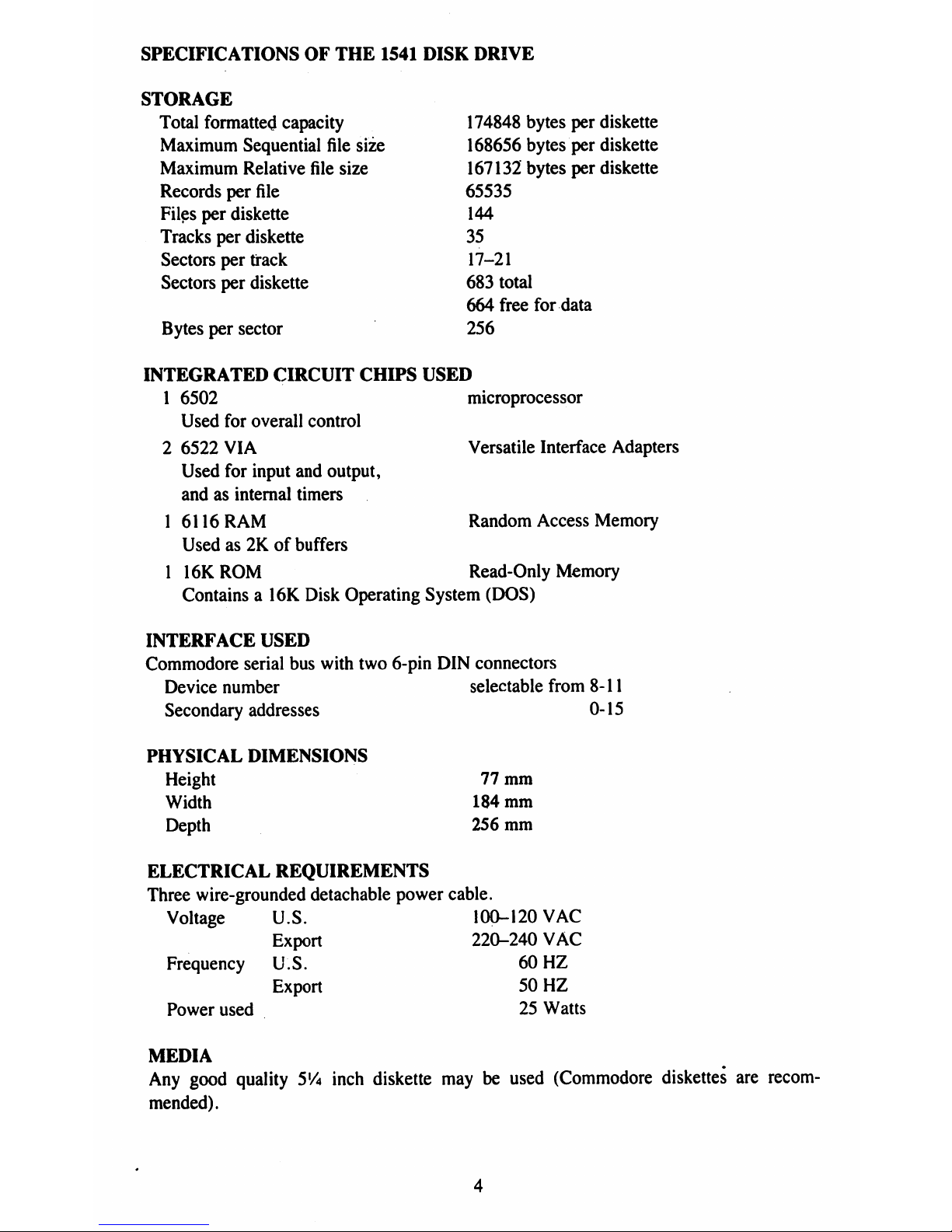

SPECIFICATIONSOFTHE

1541

DISK

DRIVE

STORAGE

Total

formatted

capacity

174848

bytes

per

diskette

Maximum

Sequential

file

size

168656

bytes

per

diskette

Maximum

Relative

file

size

167132

bytes

per

diskette

Records

per

file

65535

Files

per

diskette

144

Tracks

per

diskette

35

Sectors

per

track

17-21

Sectors

per

diskette

683

total

664

free

for

data

Bytes

per

sector

256

INTEGRATED

CIRCUIT

CHIPS

USED

1

6502

microprocessor

Used

for

overall

control

2

6522

VIA

Versatile

Interface

Adapters

Used

for

input

and

output,

andasinternal

timers

16116

RAM

Random

Access

Memory

Usedas2Kofbuffers

1

16KROM

Read-Only

Memory

Containsa16K

Disk

Operating

System

(DOS)

INTERFACE

USED

Commodore

serial

bus

with

two

6-pin

DIN

connectors

Device

number

selectable

from

8-11

Secondary

addresses

0-15

PHYSICAL

DIMENSIONS

Height

Width

Depth

77

mm

184

mm

256

mm

ELECTRICAL

REQUIREMENTS

Three

wire-grounded

detachable

power

cable.

Voltage

U.S.

100-120

VAC

Export

220-240

VAC

Frequency

U.S.

60

HZ

Export

50

HZ

Power

used

25

Watts

MEDIA

Any

good

quality

5lA

inch

diskette

maybeused

(Commodore

diskettes

are

recom

mended).

Page 13

PART

1:

GUIDE

TO

OPERATION

CHAPTER

1

DISK

DRIVE

UNPACKING

The

first

thing

you

will

needtodo

with

your

disk

driveisunpack

it.

Inside

the

carton

in

which

you

found

this

manual,

there

should

also

be: a

1541

disk

drive,

supply

power

a

black

cabletoconnect

the

disk

drivetothe

computer,

a

demonstration

diskette,

and

a

warranty

cardtobe

filled

out

and

returnedtoCommodore.

Please

don't

connect

anything

until

you've

read

the

next

three

pages!Itcould

save

youalotoftrouble.

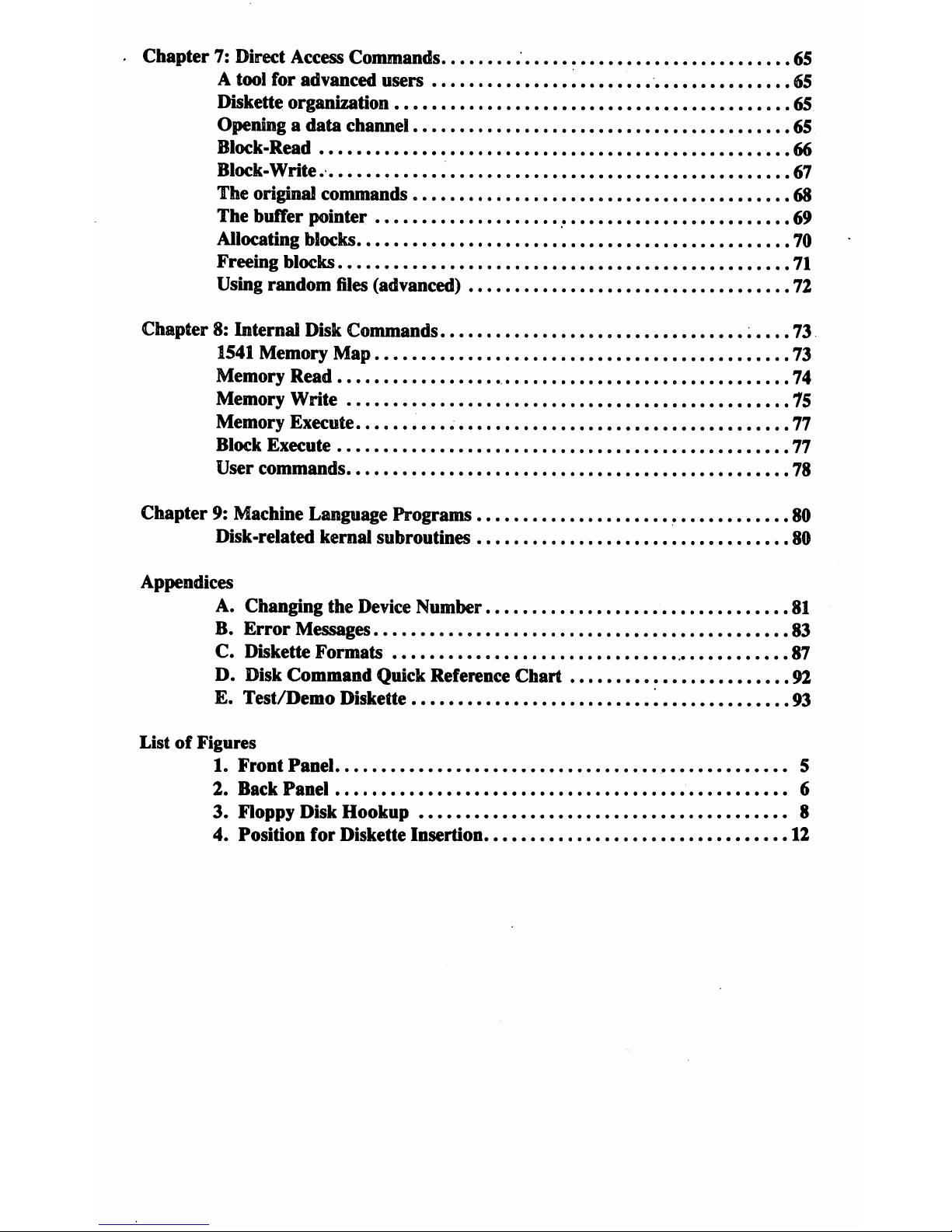

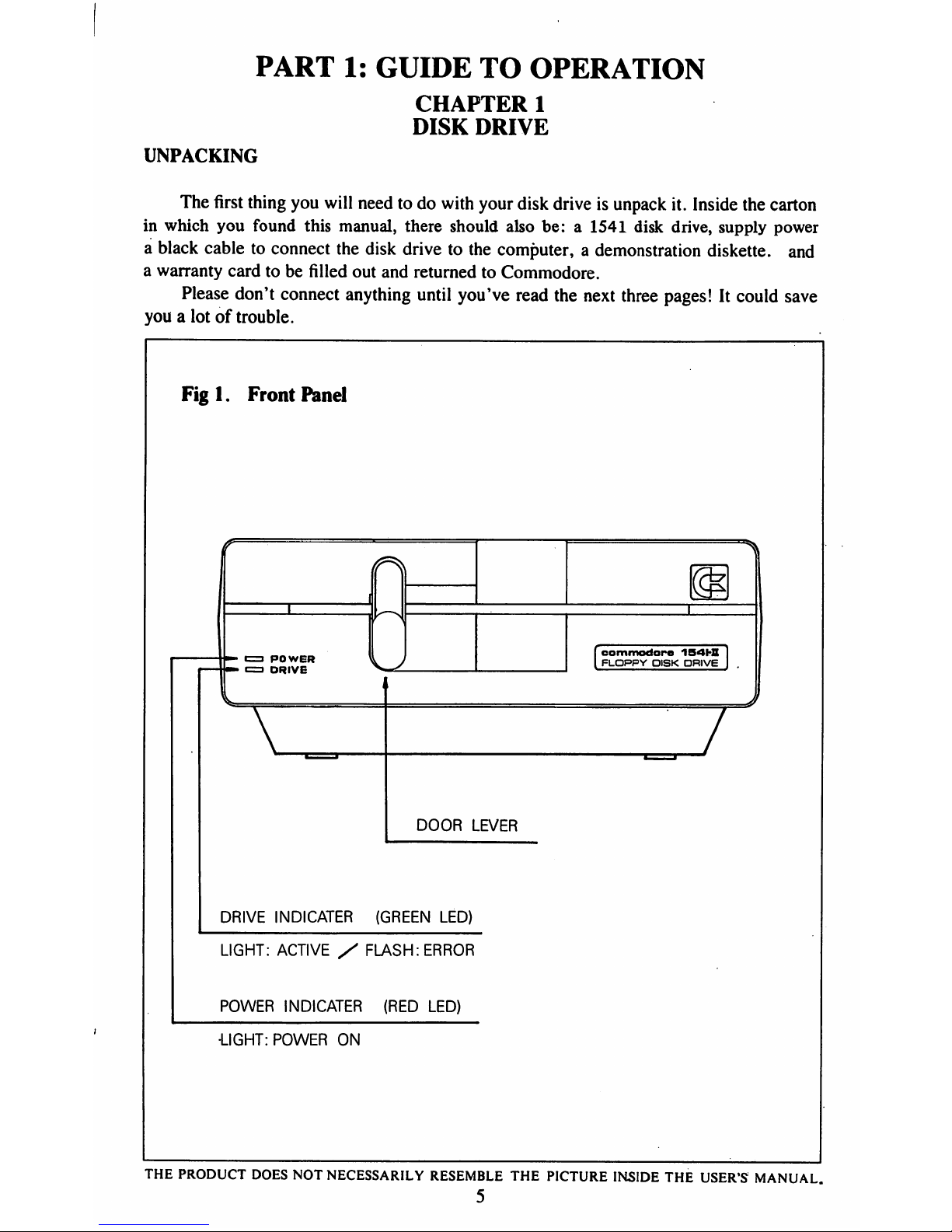

Figl.

Front

Panel

I

POWER

I

DRIVE

[commodore

154W

I

FLOPPY

DISK

DRIVE

I

V

7

DOOR

LEVER

DRIVE

INDICATER

(GREEN

LED)

LIGHT:

ACTIVE/FLASH:

ERROR

POWER

INDICATER

(RED

LED)

•LIGHT:

POWER

ON

THE

PRODUCT

DOES

NOT

NECESSARILY

RESEMBLE

THE

PICTURE

INSIDE

THE

USER'S

MANUAL.

5

Page 14

EMPTY

THE

DRIVE

First,itis

very

important

tobesure

nothingisinside the

disk

drive.Ifyou

turn

the

power

off

or

oh

withadiskette

in

the

drive,

you

could

lose

its

contents

and

have

to

re-

record

it.

Since

you

wouldn't

like

havingtodo

that,

always

checktobe

sure

nothing

is

inside

the

drive

before

turningitofforon.

When

you

first

unpack

the

disk

drive,

you

will

findacardboard

shipping spacer

inside.

Following

the

instructions

below,

pullitoutasthoughitwereadiskette,

but

don't

throwitaway.

You

will

wanttoputitback

inside

the

slot

any

time

you

moveorship

the

disk

drive

later.

To

check

whether

the

driveisempty

(Fig.

1),

simply

rotate

the

leveronthe

front

of

the

disk

drive

counter-clockwise

untilitstops,

one-quarter

turnatmost.

Then

reach

inside

the

long

slot

the

lever

covers

whenitpoints

down,

and

pull

out

any

diskette

you

find

there.

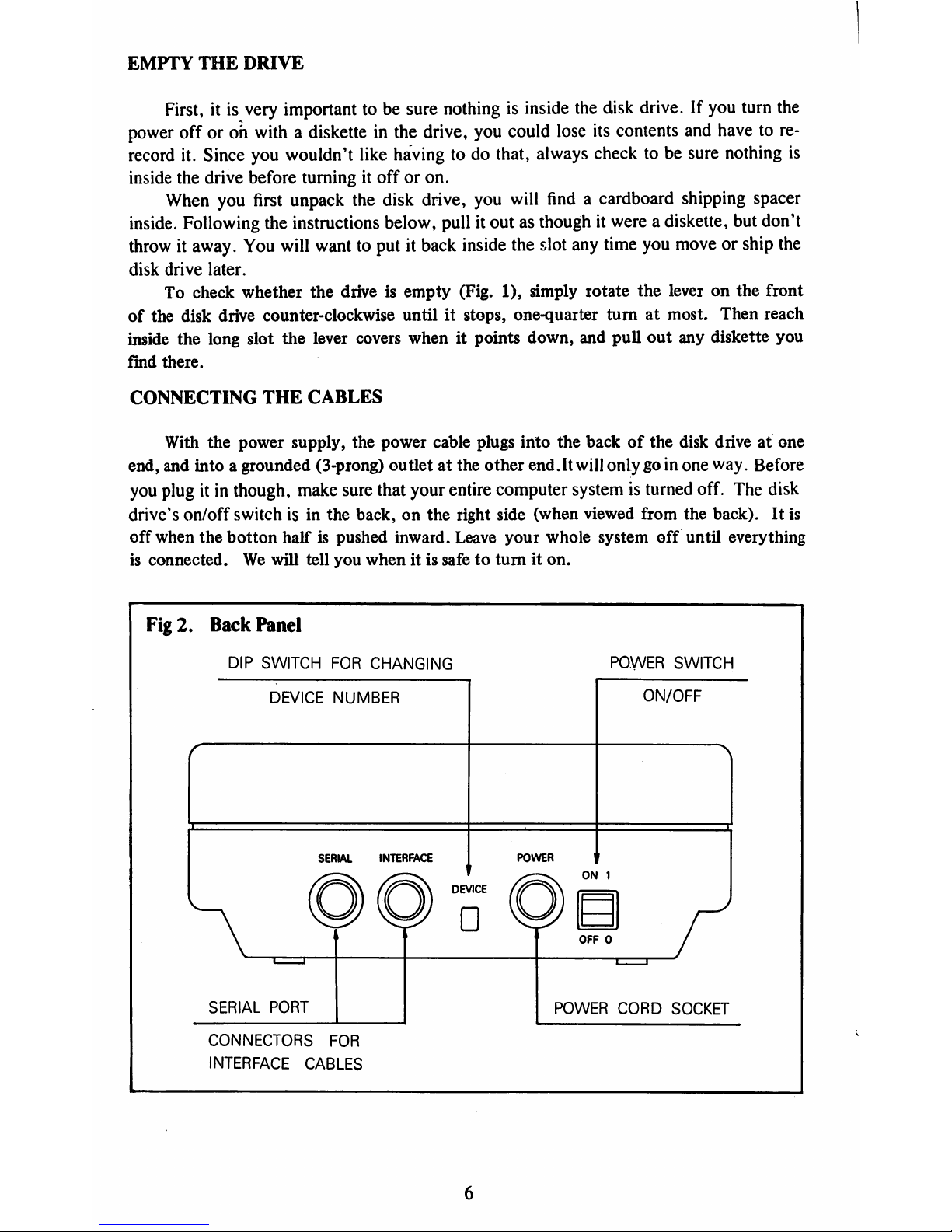

CONNECTING

THE

CABLES

With

the

power

supply,

the

power

cable

plugs

into

the

backofthe

disk

driveatone

end,

and

intoagrounded

(3-prong)

outletatthe

other

end.It

will

onlygoin

one

way.

Before

you

plugitin

though,

make

sure

that

your

entire

computer

systemisturned

off.

The

disk

drive's

on/off

switchisin

the

back,onthe

right

side

(when

viewed

from

the

back).Itis

off

when

the

botton

halfispushed

inward.

Leave

your

whole

system

off

until

everything

is

connected.Wewill

tell

you

whenitis

safe

to turniton.

Fig

2.

Back

Panel

DIP

SWITCH

FOR

CHANGING

POWER

SWITCH

DEVICE

NUMBER

SERIAL

INTERFACE

POWER

ON/OFF

ON

1

SERIAL

PORT

OFF

0

POWER

CORD

SOCKET

CONNECTORS

FOR

INTERFACE

CABLES

Page 15

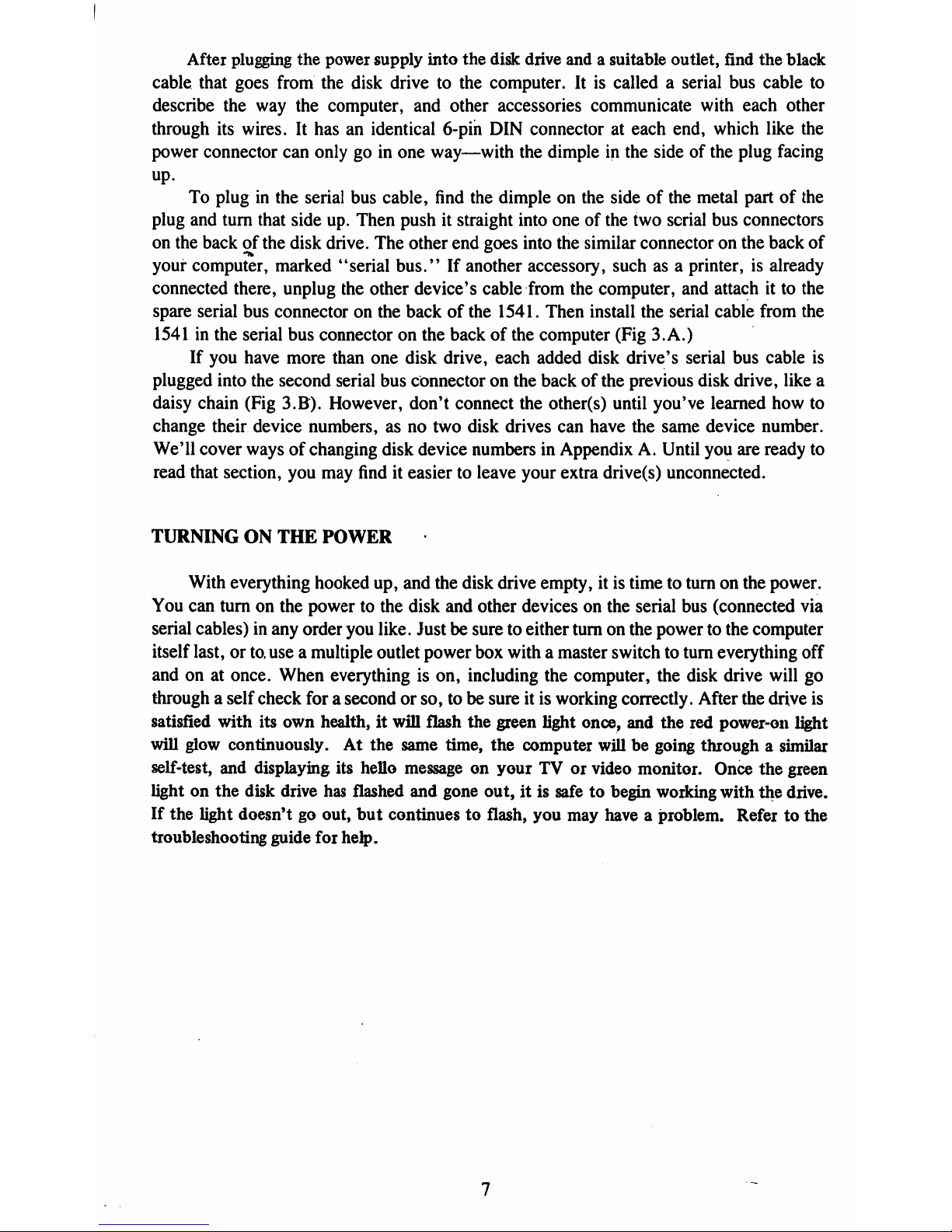

After

plugging the

power

supply

into

the

disk

drive

andasuitable

outlet,

find

the

black

cable

that

goes

from

the

disk

drivetothe

computer.Itis

calledaserial

bus

cable

to

describe

the

way

the

computer,

and

other

accessories

communicate

with

each

other

through

its

wires.Ithasanidentical

6-pin

DIN

connectorateach

end,

which

like

the

power

connector

can

onlygoin

one

way—with

the

dimpleinthe

sideofthe

plug

facing

up.

To

pluginthe

serial

bus

cable,

find

the

dimpleonthe

sideofthe

metal

partofthe

plug

and

turn

that

side

up.

Then

pushitstraight

into

oneofthe

two

serial

bus

connectors

on

the

backofthe

disk

drive.

The

other

end

goes

into

the

similar

connectoronthe

back

of

your

computer,

marked

'*serial

bus."Ifanother

accessory,

suchasa

printer,isalready

connected

there,

unplug

the

other

device's

cable

from

the

computer,

and

attachitto

the

spare

serial

bus

connectoronthe

backofthe

1541.

Then

install

the

serial

cable

from

the

1541inthe

serial

bus

connectoronthe

backofthe

computer

(Fig

3.A.)

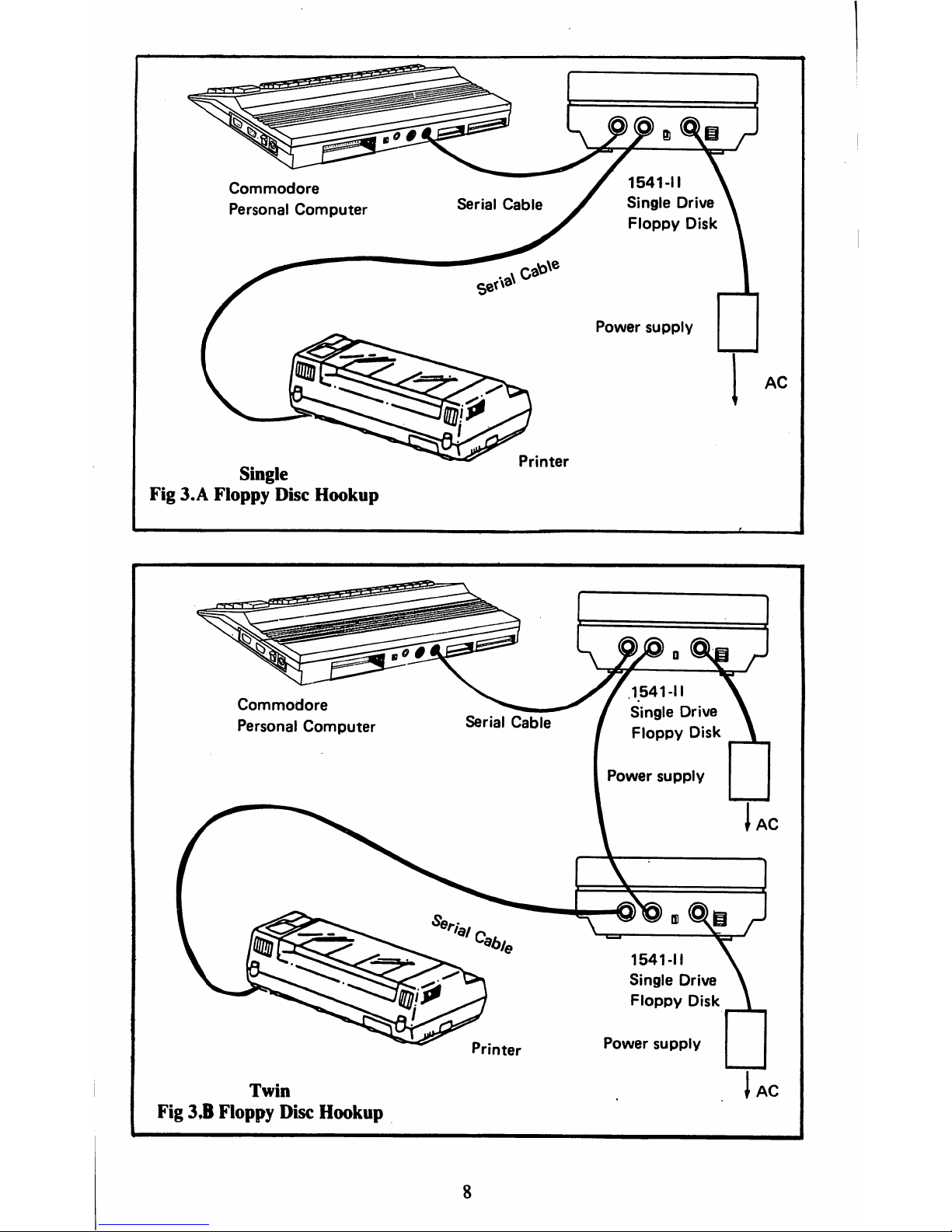

If

you

have

more

than

one

disk

drive,

each

added

disk

drive's

serial

bus

cable

is

plugged

into

the

second

serial

bus

connectoronthe

backofthe

previous

disk

drive,

like

a

daisy

chain

(Fig

3.B).

However,

don't

connect

the

other(s)

until

you've

learned

how

to

change

their

device

numbers,asno

two

disk

drives

can

have

the

same

device

number.

We'll

cover

waysofchanging

disk

device

numbersinAppendixA.Until

you

are

ready

to

read

that

section,

you

may

finditeasiertoleave

your

extra

drive(s)

unconnected.

TURNINGONTHE

POWER

With

everything

hooked

up,

and

the

disk

drive

empty,itis

timetoturnonthe

power.

You

can

turnonthe

powertothe

disk

and

other

devicesonthe

serial

bus

(connected

via

serial

cables)inany

order

you

like.

Justbesuretoeither

turnonthe

powertothe

computer

itself

last,orto.

use a

multiple

outlet

power

box

withamaster

switchtoturn

everything

off

andonat

once.

When

everything

is

on,

including

the

computer,

the

disk

drive

will

go

throughaself

check

forasecondorso, tobesureitis

working

correctly.

After

the

drive

is

satisfied

with

its

own

health,itwill

flash

the

green

light

once,

and

the

red

power-on

light

will

glow

continuously.Atthe

same

time,

the

computer

willbegoing

throughasimilar

self-test,

and

displaying

its

hello

messageonyourTVor

video

monitor.

Once

the

green

lightonthe

disk

drive

has

flashed

and

gone

out,itis

safetobegin

working

with

the

drive.

If

the

light

doesn'tgoout,

but

continuestoflash,

you

may

haveaproblem.

Refertothe

troubleshooting

guide

for

help.

Page 16

Commodore

Personal

Computer

Single

Fig

3.A

Floppy

Disc

Hookup

Printer

1541-11

Single

Drive

Floppy

Disk

Power

supply

Printer

Twin

Fig

3.B

Floppy

Disc

Hookup

Power

supply

1541-11

Single

Drive

Floppy

Disk

Commodore

Personal

Computer

lAC

Page 17

TROUBLESHOOTING

GUIDE

Symptom

Red

indicator

light

on

the

1541

not

on

Cause

Disk

drive

not

turned

on

Power

supply

not

plugged

in

Power

off

to

wall

outlet

Remedy

Make

sure

power

switch

isinthe

"on"

position

Check

both

cordsofpower

cabletobe

sure

they

are

fully

inserted

Replace

fuseorreset

circuit

breakerinhouse

Green

error

light

The

disk

drive

is

Turn

the

system'off

for

on

anve

Hashes

failing

its

power-on

a

minute

and

try

again,

continously

on

self-test

Ifitrepeats,

try

again

power-up,

before

with

the

serial

bus

any

disk

commands

disconnected.

If

it

have

been

given

still

repeats,

call

your

dealer.Ifunplugging

the

serial

cable

made

a

difference,

check

the

cable

for

proper

connection

at

both

ends.

This

can

alsobecaused

by

some

cartridges

on

the

C-64

and

always

by

a

16K

cartridgeonthe

VIC

20.

Remove

the

cartridge

and

power-up

the

disk

drive

again

to

determine

where

the

problem

is.

(The

principle

behind

unplugging

the

serial

cableis"divide

and

conquer.'1

The

drive

candoits

power-on

test

even

when

not

connectedtoa

computer.Ifit

succeeds

that

way,

then

the

problem

is

probablyinthe

cableorthe

restofthe

system,

not

the

1541.)

Page 18

TROUBLESHOOTING

GUIDE

Symptom

Cause

Program's

won't

load,

and

computer

says

"DEVICE

NOT

PRESENT

ERROR.''

Programs

won't

load,

but

computer

and

disk

drive

givenoerror

message.

Serial

bus

cable

not

well

connected,

or

disk

not

turned

on.

Another

deviceonthe

serial

bus

may

be

interfering.

Be

sure

serial

bus

cable

is

correctly

inserted

and

disk

driveisturned

on

Unplug

all

other

devices

on

the

serial

bus.

If

that

cures

it,

plug

them

in

oneata

time.

The

one

just

added

when

the

trouble

repeatsismost

likely

the

problem.

Also,

tryingtoload

a

machine

language

program

into

BASIC

space

will

cause

this

problem.

(Such

devices

may

notbeturnedonproperly,

or

may

have

conflicting

device

numbers.

Only

one

deviceonthe

bus

can

have

any

one

device

number.)

Programs

won't

load

and

disk

error

light

flashes.

A

disk

error

has

occurred.

Check

the

disk

error

channeltosee

why

the

error

occurred.

Follow

the

adviceinAppendix

B

to

correct

it.

(Be

suretospell

program

names

exactly

right,

as the

disk

driveisvery

particular,

even

about

spaces

and

punctuation

marks,

and

will

not

loadaprogram

unless

you

callitexactly

the

same

thingitwas

called

whenitwas

savedonthe

diskette.)

Your

own

programs

Load

fine,

but

commercial

programs

and

those

from

other

1541

owners

failtoload.

Either

the

diskette

you

are

loadingisfaulty,

(some

mass-produced

diskettes

are)oryour

disk

driveismisaligned.

Try

another

copyofthe

troublesome

programs.

If

several

programs

from

several

sources

always

failtoload,

have

your

dealer

align

your

disk

drive.

Your

own

programs

that

usedtoLoad

won't

any

more,

but

programs

savedonnewly-formatted

diskettes

still

work.

Older

diskettes

have

been

damaged.

The

disk

drive

has

gone

outofalignment.

See

the

sectiononsafety

rules

for

diskette

care.

Recopy

from

backups.

Have

your

dealer

align

your

disk

drive.

The

disk

drive

powers

up

with

the

activity

light

blinking.

Hardware

failure

(RAM,

ROM,

PCB).

Have

your

dealer

send

it

out

for

repair.

10

Page 19

SIMPLE

MAINTENANCE

TIPS

Your

1541

should

serve

you

well

for

yearstocome,

but

there

areafew

things

you

candoto

avoid

costly

maintenance.

1.

Keep

the

drive

well-ventilated.

Likearefrigerator,

it

needsafew

inchesofair

circulation

on

all

sidestowork

properly.

2.

Use

only

good

quality

diskettes.

Badly-made

diskettes

could

cause

increased

wear

on

the

drive's

read/write

head.Ifa

particular

diskette

is

unusually

noisyinuse,itis

probably

causing

added

wear,

and

shouldbereplaced.

3.

Avoid

using

programs

that

"thump"

the

driveasthey

load.

Many

commercial

programs,

and

diskettes

that

are

failing,

cause

the

disk

drivetomakeabumping

or

chattering

noiseasit

attemptstoreadabad

sector.

If

the

diskette

canbecopiedtoa

fresh

diskette,

dosoimmediately.

Ifitis

protected

by

its

maker

against

copying,

the

thumping

is

intentional

and

will

havetobe

endured.Beaware,

however,

that

excessive

thumping,

especially

when

the

driveishot,

caused

some

older

1541'stogo

outofalignment

and

led

to

costly

repairs.

Current

1541's

have been

redesigned

to

prevent

the

problem.

Note:

the

"Memory-Write"

exampleinChapter8temporarily

turns

off

the

bumps.

4.Itwouldbea

good

ideatohave your

1541

checked

over

about

onceayearinnormal

use.

Several

items

are

likelytoneed

attention:

the

felt

load

padonthe

read/write

head

may

be

dirty

enoughtoneed

replacement,

the

head

itself

may

needabitofcleaning

(with

91%

isopropyl

alcoholona

cotton

swab),

the

rails

along

which

the

head

moves

may

need

lubrication

(with a

special

Molybdenum

lubricant,

NOT

oil),

and

the

write

protect

sensor

may

needtobe

dustedtobe

sure

its

optical

sensor

hasaclear

view.

Since

mostofthese

chores

require

special

materialsorparts,itis

besttoleave

the

worktoan

authorized

Commodore

service

center.Ifyou

wishtodo

the

work

yourself,

ask

your

dealertoorder

the

1541

maintenance

guide

for

you

(part

number

990445),

butbeaware

that

home

repair

of

the

1541

will

void

your

warranty.

11

Page 20

CHAPTER

2

DISKETTES

WHAT

ISADISKETTE?

Beforeweactually

begin

using

the

drive,

let's

takeamomenttolookatthe

Test/Demo

diskette

packed

with

the

disk

drive.Todo

this,

graspitby

the

label,

which

shouldbesticking

outofthe

paper

jacket.

Then

pullitoutofthe

jacket

which

keepsitfree

of

dust

and

other

contaminants.

(Save

the

jacket;

the

diskette

should

alwaysbekeptinits

jacket

except

when

actually

in

useinthe

disk

drive.)Itis

often

calledafloppy

diskette,

becauseitis

flexible,

even

thoughitis

not

safetobend

diskettes.

A

diskette

is

much

likeacassette

tape,

butinthe

formofa

circle

and

enclosed

within

a

protective

square

plastic

cover.Asonacassette

tape,

onlyasmall

exposed

portion

of

the

magnetic

recording

surfaceissensitive.

You

may

touch

the

restofthe

diskette

any

time

you

like,

but

avoid

touching

the

few

small

portions

that

are

not

coveredbythe

protective

cover.

Also,

never

trytoremove

this

cover.

Unlike

the

paper

jacket,

the

plastic

diskette

coverisintendedtoremainonpermanently.

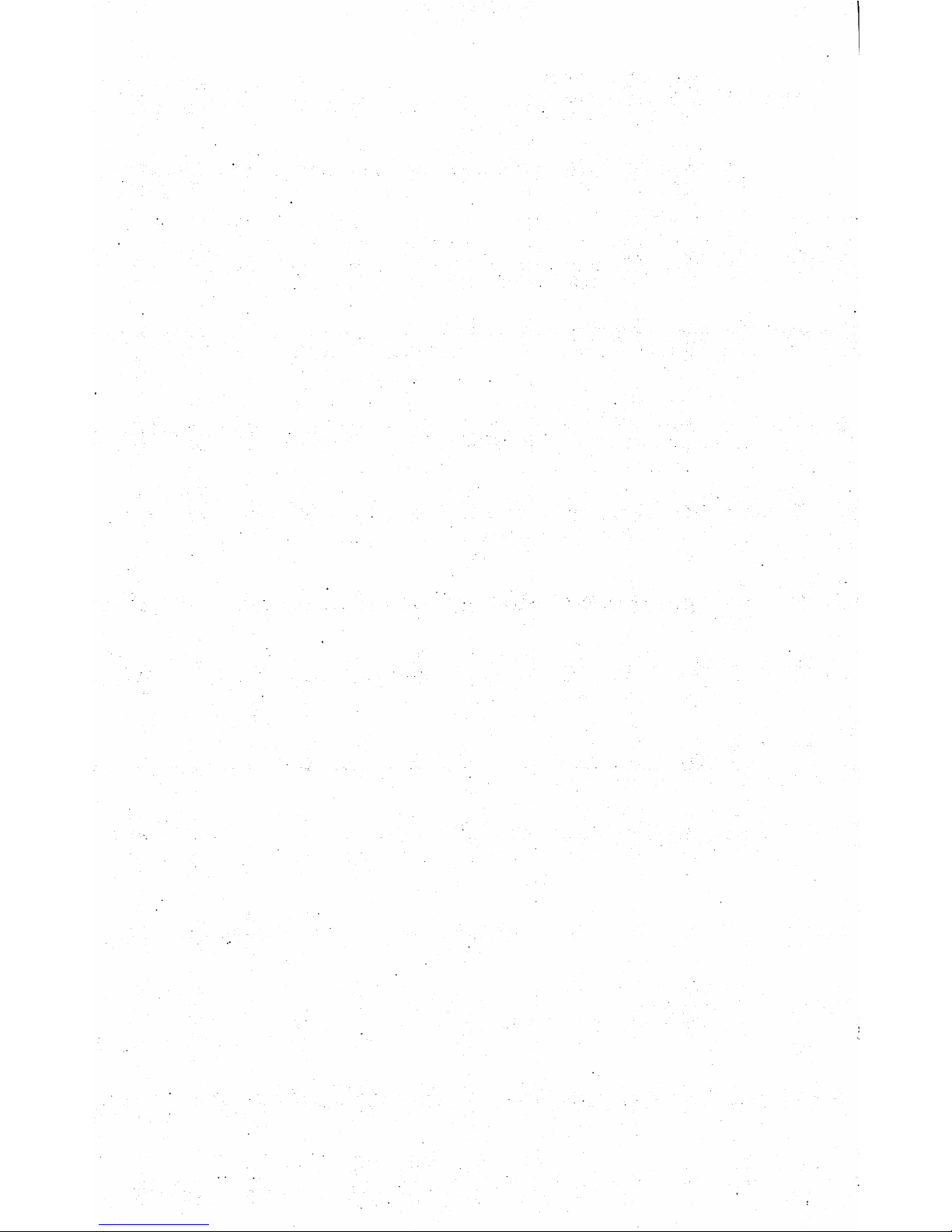

Next,

notice

the

notchonone

sideofthe

diskette

(it

maybecoveredbya

piece

of

tape).

This

notchiscalled

the

write

protect

notch.

Whenitis

covered

with

the

opaque

tape

packed

with

blank

diskettes,

the

disk

drive

cannot

change

the

contentsofthat

diskette.

Never

remove

the

tapeonthe

Test/Demo

diskette.

The

labelonthe

topofthe

diskette

says

"1541

Test/Demo"onit,

and

tells

you

which

diskette

you

are

using.

Blank

diskettes

come

with

extra

labelsinaddition

to

one

appliedbythe

makerofthe

diskette.

Use

themtodescribe

your

own

diskettes.

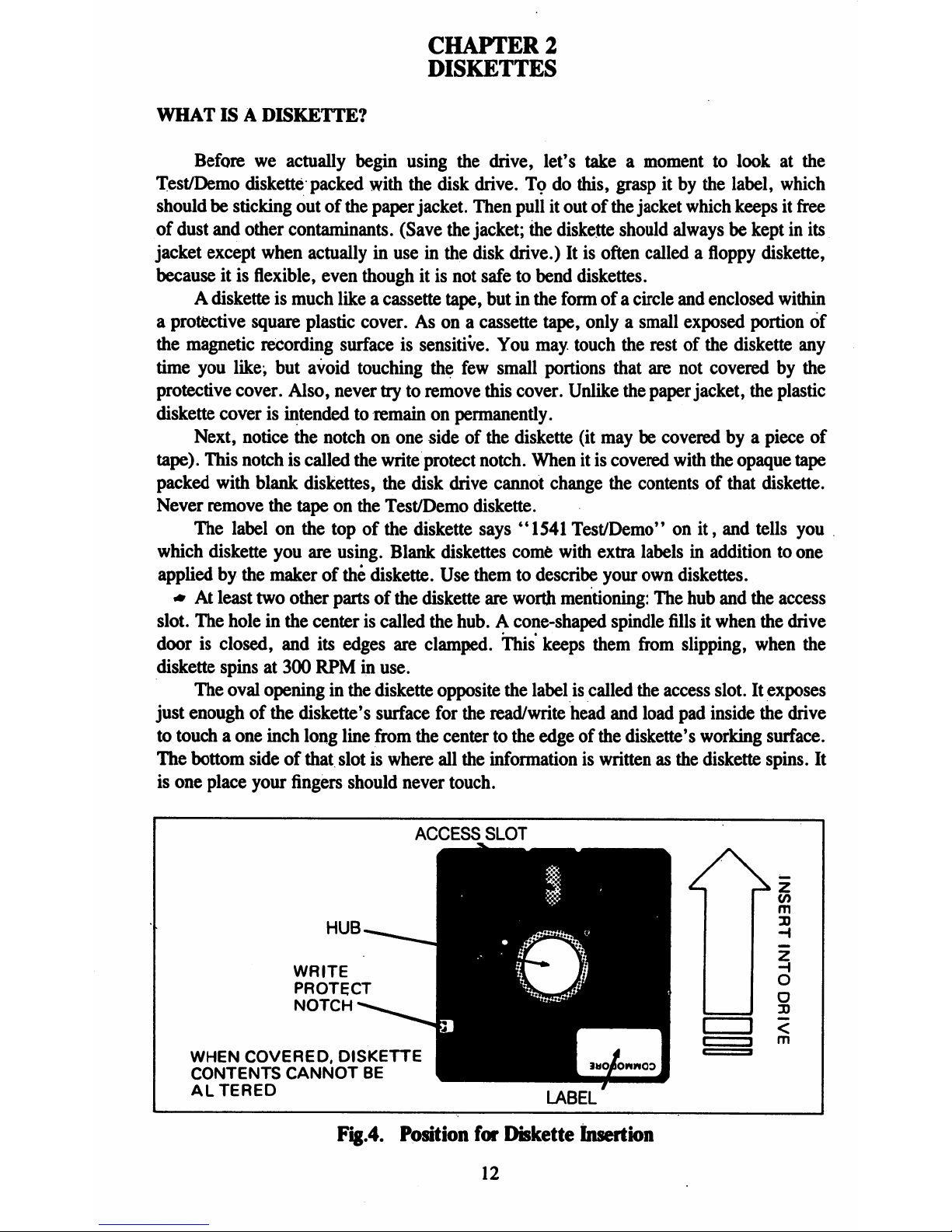

<*Atleast

two

other

partsofthe

diskette

are

worth

mentioning:

The

hub

and

the

access

slot.

The

holeinthe

centeriscalled

the

hub.Acone-shaped

spindle

fillsitwhen

the

drive

doorisclosed,

and

its

edges

are

clamped.

This

keeps

them

from

slipping,

when

the

diskette

spinsat300

RPMinuse.

The

oval

openinginthe

diskette

opposite

the

labeliscalled

the

access

slot.Itexposes

just

enoughofthe

diskette's

surface

for

the

read/write

head

and

load

pad

inside

the drive

to

touchaone

inch

long

line

from

the centertothe

edgeofthe

diskette's

working

surface.

The

bottom

sideofthat

slotiswhere

all

the

information

is

writtenasthe

diskette

spins.

It

is

one

place

your

fingers

should

never

touch.

ACCESS

SLOT

HUB

WRITE

PROTECT

NOTCH

WHEN

COVERED,

DISKETTE

CONTENTS

CANNOT

BE

ALTERED

LABEL

Fig.4.

Position

for

Diskette

Insertion

12

Page 21

SAFETY

RULES

FOR

DISKETTE

CARE

1.

Keep

the

disk

drive

and

its

diskettes

away

from

all

moisture,

dust,

smoke,

food,

and

magnets

(including

the

electromagnets

in

telephones

and

TV's).

Also

keep

them

away

from

temperatures

either

too

hotortoo cold

for

youtoworkinfor

extended

periods.

2.

When

notinthe

drive,

diskettes

shouldbestored

upright

inside

their

paper

jackets.

Do

not

allow

themtobecome

bentorfolded.

Since

the

working

partofthe

diskette

is

on

the

bottom,

never

setitdownona

table

top,orother

place

where

dustormoisture

might

affect

it,

andbeespecially

carefultokeep

your

fingers

away

from

the

openings

in

the

diskette

cover.

3.

Although

some

people

sell

kits

intendedto"double

your

diskette's

capacity"

by

cuttinganextra

write-protect

notch

intoadiskette,

itisbest

nottouse

the

other

side

of

the

diskette

on

the

1541

drive,

evenifyour

diskette

is

labeled

"double-sided."

Doing

so

will

cause

added

weartoyour

diskettes

and

drive,

and

may

cost

youanimportant

program

some

day.

4.

When

buying

diskettes,

you

may

use

any

good

quality

5lA

inch

diskette.

5.

Make

sure

the

diskette

center

holeismoreorless

centeredinits

opening

before

inserting

the

diskette

into

the

drive.

Although

the

hub

assembly

will

correctly

center

most

any

diskette,

it

wouldbevery

difficult

to

rescue

data

fromadiskette

recorded

with

its

hub

off-center.

One

waytohelp

center

diskettes

isto"tickle"

the

drive

door

shut

insteadofslammingitdown.Bygently

closing

it

part-way,

and

then

openingabit

and

then

closing

the

restofthe

way,

you

give

the

spindle

more

chancestocenter

the

diskette

properly.

Another

waytoease

diskette

centering

istobuy

diskettes

that

come

with

reinforced

hubs.

These

hard

plastic

rings

around

the

hub

opening

make

the

diskette

hub

more

rigid,

and

easiertocenter

properly.

INSERTINGADISKETTE

To

insertadisketteina

1541

(Fig.

1),

first

open

the

drive

doorbyrotating

the

door

lever

counter-clockwise

one

quarter

turn

untilitstops,

with

the

lever

level

with

the

slot

in

the

frontofthe

drive.

Grasp

the

diskettebythe

side

opposite

the

large

oval

access

slot,

and

holditwith

the

labelupand

the

write-protect

notchtothe

left.

Now

insert

the

diskettebypushing

it

straight

into

the

slot,

the

access

slot

goinginfirst

and

the

label

last.Besure

the

diskette

goesinuntilitstops

naturally,

withnopart

showing

outside

the

drive,

but

you

shouldn't

havetoforceorbenditto

getitthere.

With

the

disketteinposition,

seatitproperly

for

usebytwisting

the

door

lever

clockwise

one-quarter

turn,

vertically

over

the

slot

untilitstops.Ifit

does

not

move

easily,

stop!

You may

have

put

the

diskette

in

the

wrong

way,orincompletely.

If

that

happens,

reposition

the

diskette

until

the

door

lever

closes

easily.

13

Page 22

SAFETY

RULES

FOR

REMOVING

DISKETTES

Always

remove

diskettes

before

turningadrive

offoron.Ifa

diskette

wereinplace

and

the

door

closedatpoweronor

off,

you

could

lose

partorallofthe

dataonthat

diskette.

Similarly,

do

not

removeadiskette

from

its

drive

when

the green

drive

activity

light

is

on!

That

light

only

glows

when

the

driveisactually

in

use.

Removing

the

diskette

with

it

on

may

resultinyour

losing

information

currently

being

writtentothe

diskette.

LOADINGAPACKAGED

PROGRAM

To

use

prepackaged

BASIC

programs

available

on

diskette,

hereisthe

procedure:

After

turningonyour

computer

system,

carefully

insert

the

preprogrammed

diskette

as

describedonthe

previous

page.

For

purposeofdemonstration,

use

the

Test/Demo

diskette

included

with

the

disk

drive.

The

following

commands

will

loadaprogram

from

the

diskette

into

the

computer:

BASIC

2:

LOAD

"program

name",device

number,relocate

flag

Example:

LOAD

"HOW

TO

USE",8

BASIC3.5:

DLOAD

"program

name",Ddrive

#,Udevice

number,relocate

flag

Example:

DLOAD

"HOW

TO

USE"

After

each

command

press

the

RETURN

key

In

both

cases

the

exact

nameofthe

program

wantedisplaced

between

quotation

marks.Drive#is

optional.

Nextisthe

device

numberofyour

disk

drive

which,

unless

you

change

it,isalways

8

on

the

1541.Ifyou

have

more

than

one

drive

however,

you

will

needtochange

the

device

numberonany

additional

drive

(see

AppendixAfor

instructions

on

setting

a

drive's

device

number).

14

Page 23

Lastisthe

relocate

flag.Itcan

have

oneoftwo

values,0and1.If

the

relocate

flag

is

0oromitted,

all

Commodore

computers

that

use

the

1541

automatically

relocate

the

programs

they

loadtoliveinthe

partofcomputer

memory

reserved

for

BASIC

programs.

If

the

relocate

flag

valueis1,

auto-relocation

is

turned

off,

and

the

programisloaded

into

the

exact

partofmemory

from

whichitwas

originally

saved.

This

feature

allows

machine-language

and

other

special

purpose

programstocome

into

the

computer

at

the

correct

location

for

themtooperate

properly.Atthis

pointinyour

learning,

the

only

thing

you

needtoknow

about

the

relocate

flagishowtouse

it.

Simply

include

the1at

the

endofthe

LOAD

commandifa

particular

program

doesn't

run

properly

when

loaded

the

usual

way.

After

you

typeinthe

command

and

press

the

RETURN

key,

the

fallowing

will

appearonthe

screen:

SEARCHING

FOR

"HOW

TO

USE"

LOADING

READY.

When

the

word

READY

and

the

flashing

cursor

reappearonthe

screen

and

the

green

light

goes

offonthe

drive,

the

program

named

"HOW

TO

USE"onthe

Test/Demo

diskette

has

been

loaded

into

the

computer.Touse

it,

just

type

the

word

RUN

and

press

the

RETURN

key.

The

same Load

command

will

also

allow

youtoload

other

prepackaged

programs

from

the

Test/Demoorother

diskettes.

Merely

substitute

the

exact

program

name

that

you

wanttouse

between

the

quotation

marksinthe

above

example,

and

that

willbethe

program

the

computer

will

load(alistofTest/Demo

programsisshowninChapter3,in

the

section

entitled

"WhataDirectory

Shows").

Note:

here

andinthe

remainderofthe

book,wewill

assume you

areingraphic

mode,

seeing

upper

case

letters

and

graphic

characters

when

you

type.

Thisisthe

normal

condition

of

all

Commodore

computers

coveredbythis

manual

when

they

are

first

turned

on.Ifyou

now

see

lower-case

letters

when

you

type

without

using

the

SHIFT

key,

you

are

in

text

mode

instead.

Press

the

COMMODORE

key

(Q:),atthe

lower

left

cornerofyour

keyboard,

together

with a

SHIFT

keytoswitchtographic

mode.

HOW

TO

PREPAREANEW

DISKETTE:

BASIC

2

A

diskette

needsapatternofmagnetic

groovesinorder

for

the

drive's

read/write

headtofind

thingsonit.

This

patternisnotonyour

diskettes

when

you

buy

them,

but

addingittoadisketteissimple

once

you

knowtodo

it.

Hereisthe

procedure:

FORMAT

FOR

THE

DISK

NEW

COMMAND

OPEN

15,device

#,15,"Ndrive

#:diskette

name,id"

CLOSE

15

This

Open

command

willbedescribed

more

fully in

Chapters

4

and5.For

now,

just

copyitas

is,

replacing

only

the

parts

giveninlower

case.

These

include:

the

device

15

Page 24

numberofthe

1541,

normally8;the

drive

number,

always0on

the

1541;

any

desired

name

for

the

diskette,

upto16

characters

in

length,

followedbya2character

diskette

ID

number.

The

Close

command

is

often

optional;

just

don't

Open

that

same

file

again

without

Closingitthe

first

time.

EXAMPLE:

OPEN

15,8,15,"N0:MY

FIRST

DISK,01":

CLOSE

15

Note:

the

chattering

or

thumping

noise

you

hear

just

after

the

disk

New

command

beginsisentirely

normal.

The

disk

mustbesureitisattrack1,whichitassures

by

stepping

outward45times

(ona35

track

diskette.)

The

noise

you

hearisthe

head

assembly

hitting

the

track1bumper

after

its

inevitable

arrival.

HOW

TO

PREPAREANEW

DISKETTE:

BASIC

3.5

A

diskette

needsapatternofmagnetic

groovesinorder

for

the

drive's

read/write

headtofind

thingsonit.

This

patternisnotonyour

diskettes

when

you

buy

them,

but

addingittoadiskette

is

simple

once

you

knowtodo

it.

Hereisthe

procedure:

FORMAT

FOR

THE

HEADER

COMMAND

HEADER'diskette

name''

,Iid,Ddrive

#

,Udevice

#

Where

"diskette

name"isany

desired

name

for

the

diskette,

upto16

characters

in

length;

"id"isa2character

disketteIDnumber;

"drive#"is

the

drive

number, 0

if

omitted

(asitmustbeon

the

1541);

and

"device#"is

the

disk's

device

number,

assumed

tobe8ifomitted.Asdescribedinthe

next

page,

"id"isoptionalif(and

only

if)

the

diskette

has

been

previously

formattedona

1541.

Also,

theIDmustbea

string

literal,

not

a

variableorexpression,

and

may

not

include

Basic

reserved

words.

Thus,

",IFI"

cannot

be

used

becauseIfisaBasic

keyword,

and

",I(A$)"isnot

allowed

becauseA$is

a

variable.

",IA$"isallowed,

but

theIDnumber

willbethe

letter

"A"

plusadollar

sign

($),

not

the

contents

of

the

variable

A$.Ifyou

needavariable

ID

number,

use

the

Basic

2

formofthe

format

command.

EXAMPLE:

HEADER

"MY

FIRST

DISK,I01,DO"

Note:

the

chattering

or

thumping

noise

you

hear

just

after

the

Header

command

beginsisentirely

normal.

The

disk

mustbesureitisattrack1,whichitassures

by

stepping

outward45times

(ona35

track

diskette).

The

noise

you

hearisthe

head

assembly

hitting

the track1bumper

after

its

inevitable

.arrival.

REUSINGANOLD

DISKETTE

After

you

have

once

formatted

a

particular

diskette,

you

can

re-format

itasthough

it

were

brand

newatany

time,

using

the

above

procedures.

However,

you

can

also

change

its

name

and

erase

its

programs

more

quickly

and

easilybyomitting

theIDnumber

in

16

Page 25

your

format

command.Byleaving

off

theIDnumber,

the

format

command

will

finishina

few

seconds

insteadofthe

usual90seconds.

ORGANIZINGADISKETTE

LIBRARY

Though

you

may

not

believe

it

now,

you

will

eventually

have

dozens,

if

not

hundreds

of

diskettes.

You

can

ease

life

thenbyplanning

now.

Assign

each

diskette

a

unique

ID

number

when

you

format

it.

There

are

diskette

cataloging

programs

you

can

buy,

that

store

and

alphabetize

a

listofall

your

file

names,

but

areoflimited

value

unless

your

disketteIDnumbers

are

unique.

At

least

two

valid

approaches

are

usedinassigning

ID

numbers.

One

startsat00

with

the

first

diskette,

and

continues

upward

with

each

new

diskette,

through

99,

and

then

onward

fromAA

through

ZZ.

Another

organizes

diskettes

within

small

categories,

and

starts

theIDnumber

for

each

diskette

in

that

category

with

the

same

first

character,

going

from0to

9 andAtoZwith

the

second

character

as before.

Thus,

all

'Tax"

diskettes

could

haveIDnumbers

that

begin

with

"T."

Either

approach

works

well

when

followed

diligently.

Whileonthis

subject,

maywesuggest

you

choose

names

for

diskettes

on

the

same

basis,

so they

too

willbeunique,

and

descriptive

of

the

filesonthem.

BACKUPS

WhentodoaBackup

Although

the

1541isfar

more

reliable

thanacassette

drive

under

most

circum

stances,

its

diskettes

are

still

relatively

fragile,

and

haveauseful

lifeofonlyafew

years

in

steady

use.

Therefore,

itisimportant

to

make

regular

backupsofimportant

programs

and

files.

Makeabackup

whenever you

wouldn't

wanttoredo

your

current

work.

Justasyou

should

save

your

work

every

half

hourorso

when

writing a

new

program,soyou

should

also

backupthe

diskette

you're

usingatleast

daily

while

you

are

changingitfrequently.

Inabusiness,

you

would

makeanarchival

backup

every

time

important

information

was

duetobe

erased,

suchaswhenanew

accounting

period

begins.

HowtodoaBackup

We

have

included

programsonthe

Test/Demo

diskette

that

can be

used

for

similar

purposes.

These

programs

are

described

furtherinAppendix

E.

HowtoRotate

Backups

Once

you

begintoaccumulate

backups,

you'll

wanttorecycle

older

ones.

One

good

methodisto

date

each

backup.

Then

retain

all

backups

until

the

current

projectisfinished.

When

you

are

sure

the

last

backupiscorrect,

make

another

backupofittofile,

and

move

all

older

backupstoa

boxofdiskettes

that

maybereused.

One

other

popular

approach,

suitedtoprojects

that

never

end,isto

rotate

backups

in

a

chain,

wherein

there

are

son

backups,

father

backups,

and

grandfather

backups.

Then,

when

another

backupisneeded,

the

grandfather

diskette

is

reused,

the

father

becomes

the

grandfather,

and

the

son

becomes

the

father.

Whichever

approachisused,itis

recommended

that

the

newly-made

backup

become

the

diskette

thatisimmediately

used,

and

the

diskette

thatisknowntobe

good

should

be

filed

away

as the

backup.

That

way,ifthe

backup

fails,

you'll

knowitimmediately,

rather

than

after

all

the

other

backups

have

failed

some

dark

day.

17

Page 26

CHAPTER

3

DIRECTORIES

WHAT

ISADIRECTORY?

Oneofthe

primary

advantages

of a

disk

driveisthatitcan,

with

nearly

equal

ease

and

speed,

access

any

partofa

diskette's

surface,

and

jump

quickly

from

one

spot

to

another.ADATASSETTE™,onthe

other

hand,

usually

readsacassette

file

from

the

beginningtothe

end,

without

skipping

around.Tosee

what'sona

cassette,

itisnecessary

to

lookatits

entire

length,

which

could

takeaslongasan

hour.Ona

disk

drive,byway

of

contrast,

itisa

quick

and

simple

mattertoviewalistofthe

programs

and

data

filesona

diskette.

This

listiscalled

the

directory.

VIEWING

THE

DIRECTORY:

BASIC

2

To

view

the

directory

in

Basic2,itisusually

necessary

to

load

it,

likeaprogram.

As

when

you

load

other

programs,

this

erases

anything

alreadyinBasic

memory,sobe

sure

to

save

any

work

you

don't

wanttolose

before

loading

the

directory

in

Basic2.(Chapter

4

describes

howtoSave

a program.)

For

example,toload

the

entire

directory

from

disk

device8,type:

LOAD'T',8

Then,todisplay*the

directoryonyour

screen

afteritloads

into

computer

memory,

type

LIST.

You

may

slow

the

listingbypressing

the

CONTROL

keyonthe

VIC20and

Commodore

64,

and

haltitentirelybypressing

the

STOP

key.

You

can

also

use

this

commandtolimit

the

directory

to

desired

filesbyusing

pattern-

matching

characters

described

laterinthis

chapter.

VIEWING

THE

DIRECTORY:

BASIC

3.5

To

view

the

directory

in

Basic

3.5,

simply

type

the

word

DIRECTORYona

blank

line,

and

press

the

RETURN

key.

Unlike

Basic

2's

methodofloadingadirectory,

this

does

not

erase

anything

alreadyinBasic

memory,soyou

can

safely

ask

foradirectory

at

almost

any

time,

even

from

within

another

program.

Again,

you

may

slowadirectory

listingonthe

Commodore16and

Plus/4byholding

down

the

COMMODORE

key(Ql),or

haltitentirely

by

pressing

the

STOP

key.

You

may

also

pauseitwith

CONTROL-S

(by

holding

down

the

CONTROL

key

while

pressing

the.

"S"

key),

and

resume by

pressing

any

other

key.

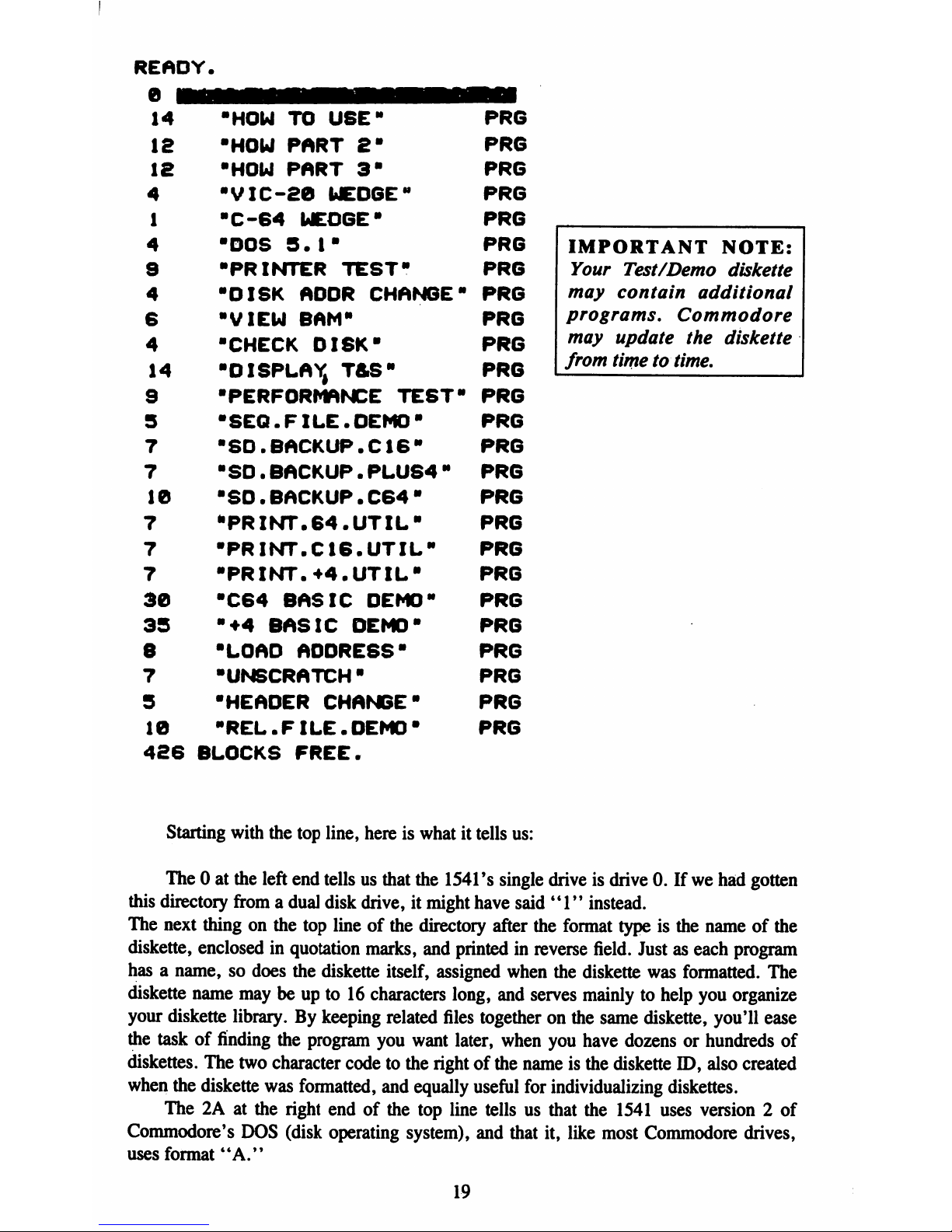

WHATADIRECTORY

SHOWS

Now

let's

lookatatypical

directoryonyour

1541

Test/Demo

Diskette.

18

Page 27

READY.

14

IS

12

4

1

4

S

4

6

4

14

9

S

7

7

10

7

7

7

30

35

8

7

9

10

•

•HOW

TO

USE"

■HOW

PART

Em

•HOW

PART

3"

■VIC-20

WEDGE"

■C-64

WEDGE*

■DOS

3.I"

•PRINTER

TEST"

"DISK

ADDR

CHANGE"

■VIEW

BAM"

■CHECK

DISK"

■DISPLAY,

T&SW

■PERFORMANCE

TEST"

"SEQ.FILE.DEMO"

■SO.BACKUP.C16"

■SD.BACKUP.PLUS4"

■SD.BACKUP.C64"

"PRINT.64.UTIL"

■PRINT.C16.UTIL"

■PRINT.44.UTIL"

■C64

BASIC

DEMO"

"44

BASIC

DEMO"

■LOAD

ADDRESS-

■UNSCRATCH"

■HEADER

CHANGE"

"REL.FILE.DEMO"

PRG

PRG

PRG

PRG

PRG

PRG

PRG

PRG

PRG

PRG

PRG

PRG

PRG

PRG

PRG

PRG

PRG

PRG

PRG

PRG

PRG

PRG

PRG

PRG

PRG

IMPORTANT

NOTE:

Your

Test/Demo

diskette

may

contain

additional

programs.

Commodore

may

update

the

diskette

from

time

to

time.

426

BLOCKS

FREE.

Starting

with

the

top

line,

hereiswhatittells

us:

The0at

the

left

end

tellsusthat

the

1541's

single

driveisdrive0.Ifwehad

gotten

this

directory

fromadual

disk

drive,itmight

have

said

"1"

instead.

The

next

thingonthe

top

lineofthe

directory

after

the

format

typeisthe

nameofthe

diskette,

enclosedinquotation

marks,

and

printedinreverse

field.

Justaseach

program

hasaname,sodoes

the

diskette

itself,

assigned

when

the

diskette

was

formatted.

The

diskette

name

maybeupto16

characters

long,

and

serves

mainlytohelp

you

organize

your

diskette

library.

By

keeping

related

files

together

on

the

same

diskette,

you'll

ease

the

taskoffinding

the

program

you

want

later,

when

you

have

dozensorhundreds

of

diskettes.

The

two

character

code

to

the

right

of

the

name

is

the

diskette

ID,

also

created

when

the

diskette

was

formatted,

and

equally

useful

for

individualizing

diskettes.

The2Aat

the

right

endofthe

top

line

tellsusthat

the

1541

uses

version2of

Commodore's

DOS

(disk

operating

system),

and

that

it,

like

most

Commodore

drives,

uses

format

"A."

19

Page 28

The

restofthe

directory

contains

one

line

per

programorfile,

each

line

supplying

three

piecesofinformation

about

its

subject.

At

the

left

endofeach

lineisthe

sizeofthat

line's

fileinblocks

(or

sectors)

of

256

characters.

Four

blocks

are

equivalent

toIK(1024

characters)

of

RAM

(read/write)

memory

inside

the

computer.

The

middleofeach

directory

line

contains

the

nameofthe

file,

enclosedinquotation

marks.

All

characters

between

the

quote

marks

are

partofthe

name,

and

mustbeincluded

when

loadingoropening

that

file.

The

right

portionofeach

directory

lineisa

three

character

abbreviation

for

the

file

typeofthat

entry.Aswe

will

see

in later

chapters,

there

are

many

waystostore

information

onadiskette,

mostofwhich

are

associated

withadistinctive

file

type.

TYPESOFFILES

AVAILABLE

Currently

used

file

types

include:

PRG =

Program

files

SEQ=Sequential

data

files

REL=Relative

data

files

USR=User

(nearly

identical

to

sequential)

DEL=Deleted

(you

may

never

see

oneofthese.)

(Note:

Direct

Access

files,

also

called

Random

files,donot

automatically

appear

in

the

directory.

They

are

discussed

in

Chapter

7.)

After

all

the directory

entries

have

listed,

the

directory

finishes

withamessage

showing

how

many

blocksofthe

diskette

are

still

available

for

use.

This

number

can

vary

from

664ona

new

diskette

to0on

one

thatisalready

completely

full.

WATCH

OUT

FOR

SPLAT

FILES!

One

indicator

you

may

occasionally

noticeona

directory

line,

after

you

begin

saving

programs and

files,isan

asterisk

appearing

just

before

the

file

typeofa

file

thatis0

blocks

long.

This

indicates

the

file

was

not

properly

closed