Page 1

ENGLISH

PPoow

weerrSSeeeekkeerr

®

®

SSeerriieess TTeelleessccooppeess

IINNSSTTRRUUCCTTIIOONN MMAANNUUAALL

●● PPoowweerrSSeeeekkeerr 6600EEQQ ## 2211004433 ●● PPoowweerrSSeeeekkeerr 7700EEQQ ## 2211003377

●● PPoowweerrSSeeeekkeerr 8800EEQQ ## 2211004488 ●● PPoowweerrSSeeeekkeerr 111144EEQQ ## 2211004455

●● PPoowweerrSSeeeekkeerr 112277EEQQ ## 2211004499

Page 2

Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................................3

ASSEMBLY ................................................................................................................................... 6

Setting up the Tripod............................................................................................................................................. 6

Attaching the Equatorial Mount .......................................................................................................................... 7

Installing the Counterweight Bar & Counterweight(s) ...................................................................................... 7

Attaching the Slow Motion Cables....................................................................................................................... 8

Attaching the Telescope Tube to the Mount........................................................................................................ 8

Installing the Diagonal & Eyepiece (Refractor).................................................................................................. 9

Installing the Eyepiece on the Newtonian............................................................................................................ 9

Installing the Finderscope................................................................................................................................... 10

Aligning the Finderscope..................................................................................................................................... 10

Installing and Using the Barlow Lens ................................................................................................................ 10

Moving the Telescope Manually......................................................................................................................... 11

Balancing the Mount in R.A. .............................................................................................................................. 11

Balancing the Mount in Dec................................................................................................................................ 11

Adjusting the Equatorial Mount ........................................................................................................................ 12

Adjusting the Mount in Altitude......................................................................................................................... 12

TELESCOPE BASICS .................................................................................................................13

Image Orientation................................................................................................................................................ 14

Focusing................................................................................................................................................................ 14

Calculating Magnification................................................................................................................................... 14

Determining Field of View .................................................................................................................................. 15

General Observing Hints..................................................................................................................................... 15

ASTRONOMY BASICS .............................................................................................................. 16

The Celestial Coordinate System........................................................................................................................ 16

Motion of the Stars .............................................................................................................................................. 16

Polar Alignment with the Latitude Scale........................................................................................................... 17

Pointing at Polaris................................................................................................................................................ 18

Finding the North Celestial Pole......................................................................................................................... 18

Polar Alignment in the Southern Hemisphere .................................................................................................. 19

Aligning the Setting Circles................................................................................................................................. 21

Motor Drive.......................................................................................................................................................... 22

CELESTIAL OBSERVING .........................................................................................................23

Observing the Moon ............................................................................................................................................ 23

Observing the Planets.......................................................................................................................................... 23

Observing the Sun................................................................................................................................................ 23

Observing Deep-Sky Objects .............................................................................................................................. 24

Seeing Conditions................................................................................................................................................. 24

ASTROPHOTOGRAPHY............................................................................................................ 25

Short Exposure Prime Focus Photography ....................................................................................................... 25

Piggyback Photography....................................................................................................................................... 25

Planetary & Lunar Photography with Special Imagers................................................................................... 25

CCD Imaging for Deep Sky Objects .................................................................................................................. 25

Terrestrial Photography...................................................................................................................................... 25

TELESCOPE MAINTENANCE.................................................................................................. 26

Care and Cleaning of the Optics......................................................................................................................... 26

Collimation of a Newtonian................................................................................................................................. 26

OPTIONAL ACCESSORIES ..................................................................................................... 29

POWERSEEKER SPECIFICATIONS......................................................................................... 30

2

Page 3

Congratulations on your purchase of a PowerSeeker telescope. The PowerSeeker Series of telescopes come in

several different models and this manual covers five models mounted on a German Equatorial Mount --- 60mm

refractor, 70mm refractor, 80mm refractor, 114mm Newtonian, and 127mm Newtonian. The PowerSeeker Series is

made of the highest quality materials to ensure stability and durability. All this adds up to a telescope that gives you

a lifetime of pleasure with a minimal amount of maintenance.

These telescopes were designed for the First Time Buyer offering exceptional value. The PowerSeeker series

features a compact and portable design with ample optical performance to excite any newcomer to the world of

amateur astronomy.

PowerSeeker telescopes carry a two year limited warranty. For details see our website at www.celestron.com

Some of the many standard features of the PowerSeeker include:

• All coated glass optical elements for clear, crisp images.

• Smooth functioning, rigid equatorial mount with setting circles in both axes.

• Preassembled aluminum tripod ensures a stable platform.

• Quick and easy no-tool set up.

• CD-ROM “The Sky” Level 1 -- astronomy software which provides education about the sky and printable sky

maps.

• All models can be used terrestrially as well as astronomically with the standard accessories included.

Take time to read through this manual before embarking on your journey through the Universe. It may take a few

observing sessions to become familiar with your telescope, so you should keep this manual handy until you have

fully mastered your telescope’s operation. The manual gives detailed information regarding each step as well as

needed reference material and helpful hint to make your observing experience as simple and pleasurable as possible.

Your telescope is designed to give you years of fun and rewarding observations. However, there are a few things to

consider before using your telescope that will ensure your safety and protect your equipment.

Warning

y Never look directly at the sun with the naked eye or with a telescope (unless you have the proper

solar filter). Permanent and irreversible eye damage may result.

y Never use your telescope to project an image of the sun onto any surface. Internal heat build-up can

damage the telescope and any accessories attached to it.

y Never use an eyepiece solar filter or a Herschel wedge. Internal heat build-up inside the telescope can

cause these devices to crack or break, allowing unfiltered sunlight to pass through to the eye.

y Do not leave the telescope unsupervised, either when children are present or adults who may not be

familiar with the correct operating procedures of your telescope.

3

Page 4

8

12

13

16

1

4

5

2

15

3

8

14

7

6

9

11

10

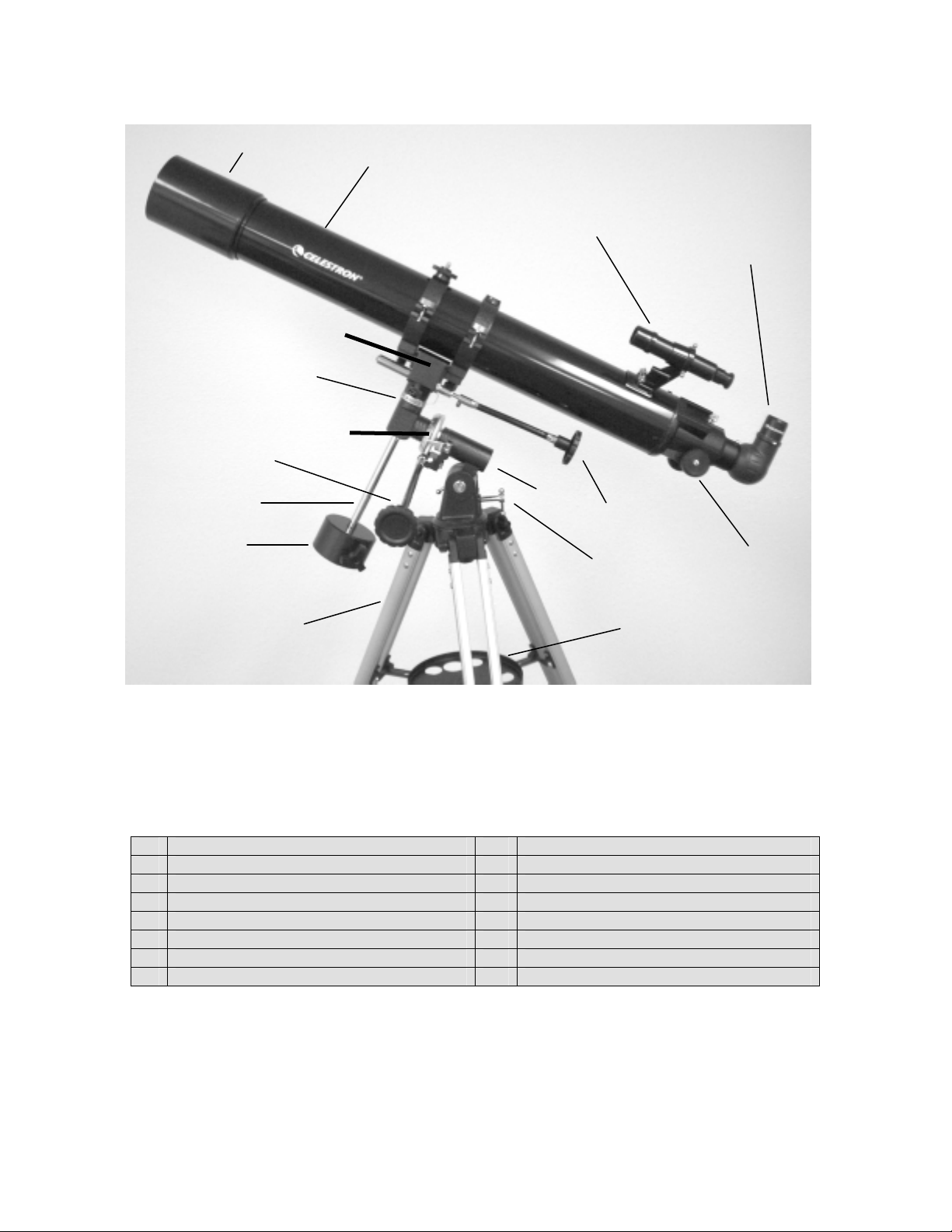

Figure 1-1 PowerSeeker 80EQ Refractor

PowerSeeker 60EQ & PowerSeeker 70EQ Similar

1. Telescope Optical Tube 9. Latitude Adjustment Screw

2. Mounting Bracket w/ Tube Rings 10. Tripod Accessory Tray

3. R.A. Setting Circle 11. Tripod

4. Finderscope 12. Counterweight Bar

5. Eyepiece & Diagonal 13. Counterweight

6. Focus Knob 14. Equatorial Mount

7. Dec. Slow Motion Cable 15. Dec. Setting Circle

8. R.A. Slow Motion Cable 16. Objective Lens

4

Page 5

1

14

2

13

12

10

6

7

9

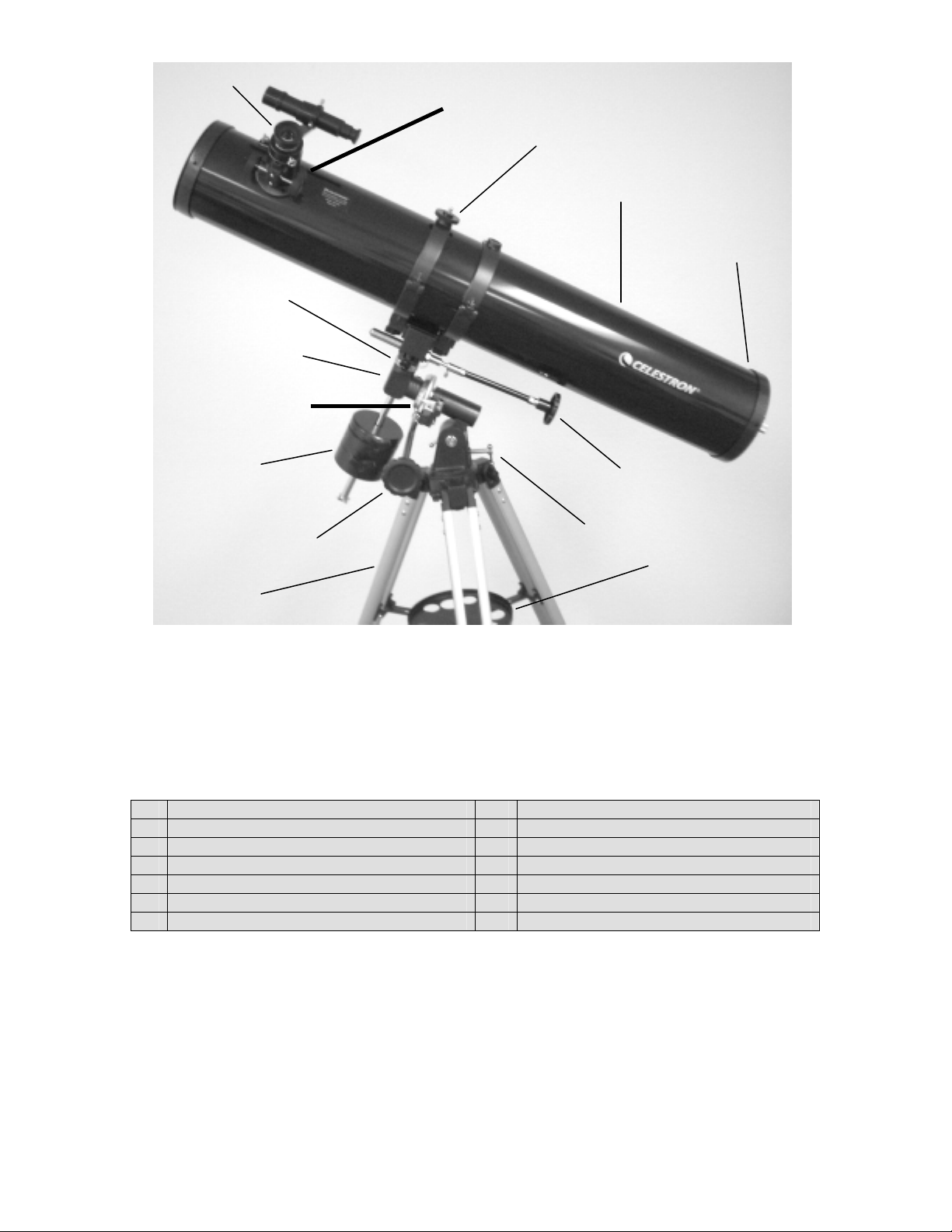

Figure 1-2 PowerSeeker 114EQ Newtonian

PowerSeeker 127EQ Newtonian Similar

1. Eyepiece 8. Tripod Accessory Tray

2. Tube Ring 9. Tripod

3. Telescope Optical Tube 10. Counterweight

4. Primary Mirror 11. R.A. Setting Circle

5. Dec. Slow Motion Cable 12. Equatorial Mount

6. R.A. Slow Motion Cable 13. Dec. Setting Circle

7. Latitude Adjustment Screw 14. Focus Knob

3

4

5

8

5

Page 6

This section covers the assembly instructions for your PowerSeeker telescope. Your telescope should be set up

indoor the first time so that it is easy to identify the various parts and familiarize yourself with the correct assembly

procedure before attempting it outdoor.

Each PowerSeeker comes in one box. The pieces in the box are – optical tube, tube rings (except 60EQ), German

equatorial mount, counterweight bar, counterweight, R.A. & Dec. slow-motion cables, 4mm eyepiece – 1.25”,

20mm eyepiece – 1.25” (erect image for 114EQ & 127EQ), erect image diagonal 1.25” (for 60EQ, 70EQ, and

80EQ), 3x Barlow Lens 1.25”, “The Sky” Level 1 CD-ROM.

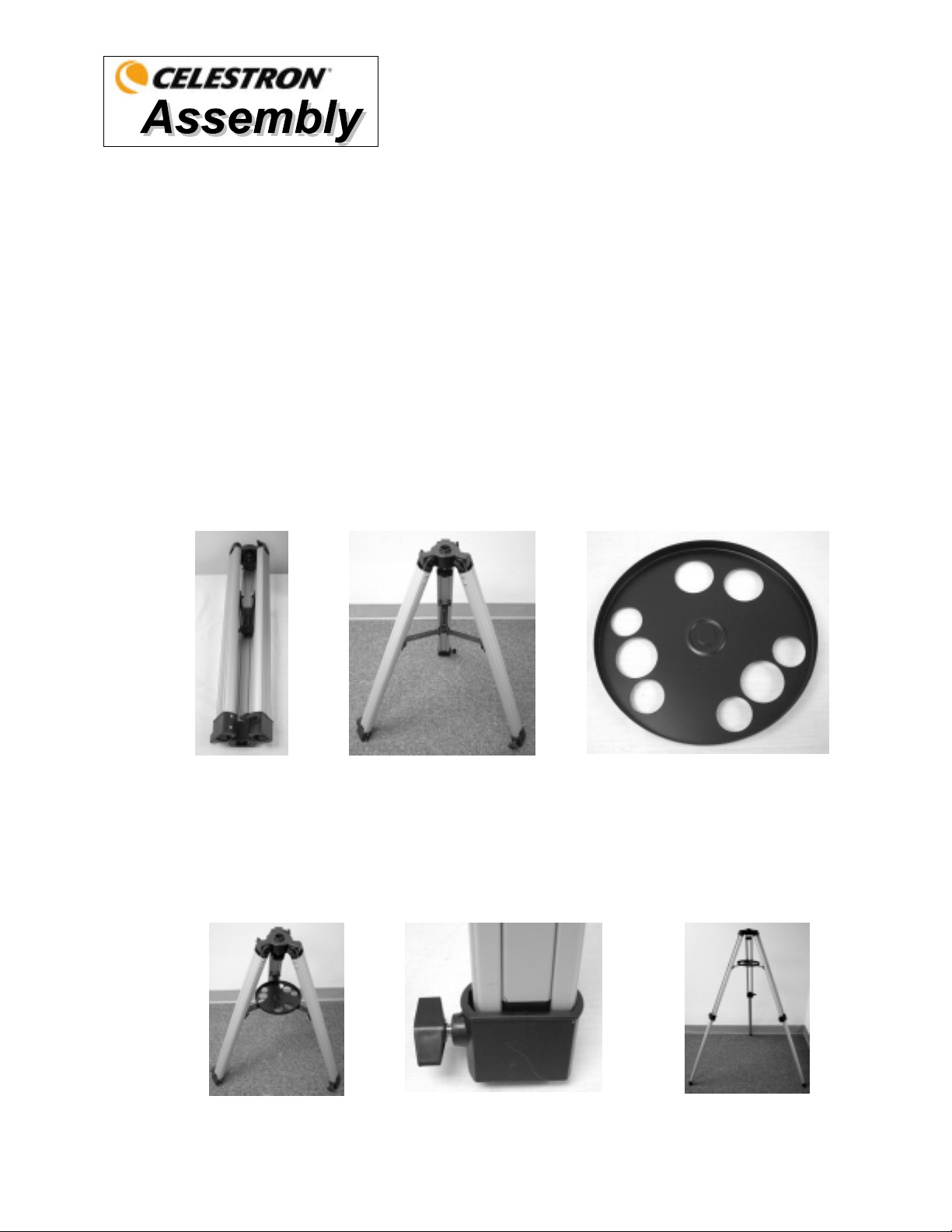

SSeettttiinngg uupp tthhee TTrriippoodd

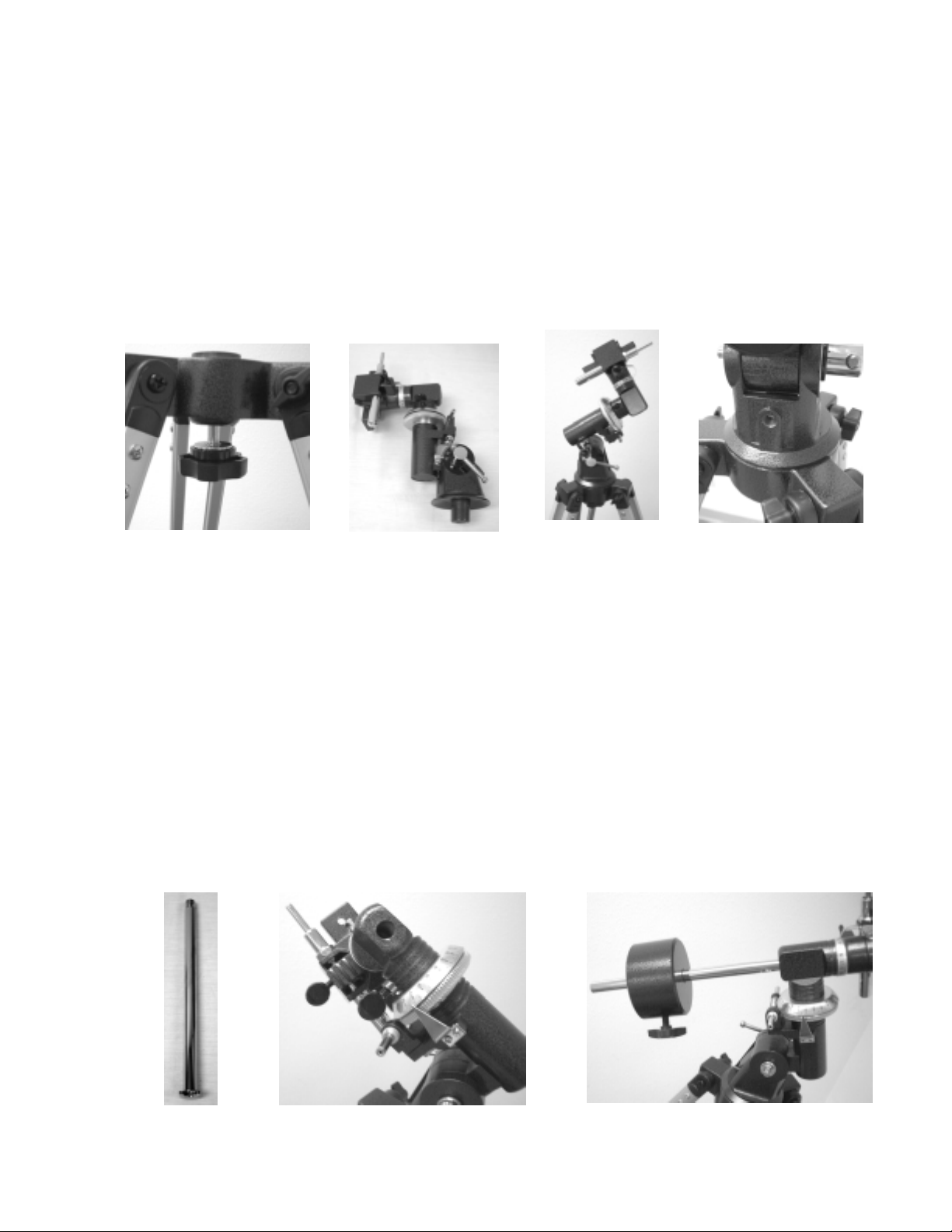

1. Remove the tripod from the box (Figure 2-1). The tripod comes preassembled so that the set up is very

easy.

2. Stand the tripod upright and pull the tripod legs apart until each leg is fully extended and then push down

slightly on the tripod leg brace (Figure 2-2). The very top of the tripod is called the tripod head.

3. Next, we will install the tripod accessory tray (Figure 2-3) onto the tripod leg brace (center of Figure 2-2).

4. On the bottom of the tripod tray is a screw attached to the center. The screw attaches into a threaded hole

in the center of the tripod leg brace by turning it counterclockwise - note: pull up slightly on the tripod leg

brace to make it easy to attach. Continue turning the tray until hand tight – don’t over tighten the tray.

5. The tripod is now completely assembled (Figure 2-4).

6. You can extend the tripod legs to the height you desire. At the lowest level the height is 26” (66cm) and

7. The tripod will be the most rigid and stable at the lower heights.

Figure 2-1 Figure 2-2 Figure 2-3

extends to 47” (119cm). You unlock the tripod leg lock knob at the bottom of each leg (Figure 2-5) by

turning them counterclockwise and pull the legs out to the height you want & then lock the knob securely.

A fully extended the tripod looks like the image in Figure 2-6.

Figure 2-4 Figure 2-5 Figure 2- 6

6

Page 7

t

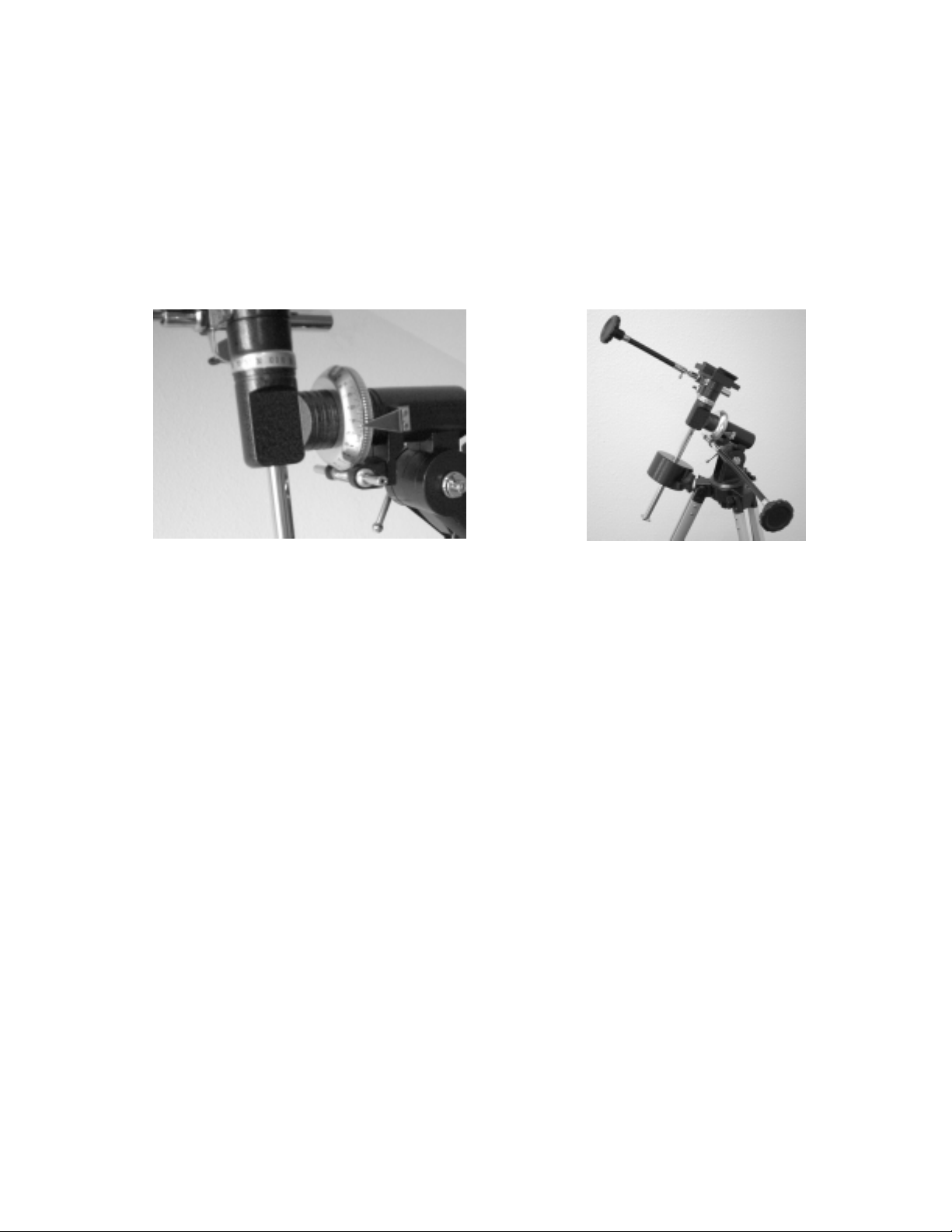

AAttttaacchhiinngg tthhee EEqquuaattoorriiaall MMoouunnt

The equatorial mount allows you to tilt the telescopes axis of rotation so that you can track the stars as they move

across the sky. The PowerSeeker mount is a German equatorial mount that attaches to the tripod head. To attach

the mount:

1. Remove the equatorial mount from the box (Figure 2-8). The mount has the latitude locking bolt attached to

it (Figure 2-27). The latitude adjustment screw attaches to the threaded hole in the mount as shown in Figure

2-10.

2. The mount will attach to the tripod head and more specifically to the knob with bolt attached under the tripod

head (Figure 2-7). Push the mount (large flat portion with a small tube sticking out) into the center hole of the

tripod head until it is flush and hold it steady. Then, reach under the tripod head with your other hand and

turn the knob counterclockwise which will thread it into the bottom of the mount. Continue turning until it is

tight. The completed assembly of the mount to the tripod is seen in Figure 2-9.

Figure 2-7 Figure 2-8 Figure 2-9 Figure 2-10

IInnssttaalllliinngg tthhee CCoouunntteerrwweeiigghhtt BBaarr && CCoouunntteerrwweeiigghhtt((ss))

To properly balance the telescope, the mount comes with a counterweight bar and one or two counterweights

(depending on the model you have). To install them:

1. Remove the counterweight safety screw from the counterweight bar (at the opposite end of the threaded rod)

by unthreading it counterclockwise – see Figure 2-11.

2. Install the large threads of the counterweight bar into the threaded hole in the Dec. axis of the mount and turn

clockwise-- see Figure 2-12 until it is tight. Now you are ready to attach the counterweight(s).

3. Orient the mount so that the counterweight bar points toward the ground.

4. Loosen the locking knob on the side of the counterweight so that the threads do not protrude through the

center hole of the counterweight.

5. Slide the counterweight onto the counterweight bar about half way up and tighten the locking knob securely.

The correct orientation of the weight is shown in Figure 2-13.

6. Slide the second counterweight (if your model has a second weight) onto the counterweight bar flush up

against the first one and then lock securely.

7. Replace the safety screw and thread it on securely. The completed assembly is shown in Figure 2-13.

Figure 2-11 Figure 2-12 Figure 2-13

7

Page 8

AAttttaacchhiinngg tthhee SSllooww MMoottiioonn CCaabblleess

The PowerSeeker mount comes with two slow motion control cables that allow you to make fine pointing

adjustments to the telescope in both R.A. and Declination. To install the cables:

1. Locate the two cables with knobs on them. The longer one is for the R.A. axis and make sure the screw on

each cable end does not protrude through the opening.

2. Slide the cable onto the R.A. shaft (see Figure 2-14) so the screw fits over the groove in the R.A. Shaft.

There are two R.A. shafts, one on either side of the mount. It makes no difference which shaft you use since

both work the same (except if using a motor drive). Use whichever one you find more convenient.

3. Tighten the screw on the R.A. cable to hold it securely in place.

4. The DEC slow motion cable attaches in the same manner as the R.A. cable. The shaft that the DEC slow

motion knob fits over is toward the top of the mount, just below the telescope mounting platform.

Figure 2-14

R.A. Shaft on bottom below the R.A. Setting

Circle Dec. Shaft on top above the Dec. Setting

Circle

AAttttaacchhiinngg tthhee TTeelleessccooppee TTuubbee ttoo tthhee MMoouunntt

R.A. & Dec. Cables attached

Figure 2-15

The telescope optical tube attaches to the equatorial mount with tube rings (except on the 60EQ) supporting it to the

mounting bracket at the top of the mount (Figure 2-16). For the 60EQ refractor, the tube mounts directly to the

mounting bracket with the screw studs attached to the optical tube. Before you attach the optical tube, make sure

that the declination and right ascension locking knobs are tight (Figure 2-24). Then, make sure that the

latitude adjustment screw and latitude locking bolt (Figure 2-27) are tight. This will ensure that the mount does

not move suddenly while attaching the telescope optical tube. Also, remove the objective lens cap (refractor) or the

front opening cap (Newtonian). To mount the telescope tube:

1. Remove the protective paper covering the optical tube. You will have to remove the tube rings (Figure 2-16)

before removing the paper.

2. Remove the knobs from the threaded posts at the bottom of the tube rings (Figure 2-16).

3. Now put the posts through the holes in the top of the mount platform (Figure 2-17) and put the knobs back on

and tighten and they will look like Figure 2-18.

4. Open the tube rings (loosen the large chromed knobs) so that the optical tube can be put on.

5. Hold the optical tube carefully with one hand and center in the tube rings and close the rings and latch and

tighten the knurled knobs of the tube rings which will look like Figure 2-19.

6. Note that you could attach the tube rings to the optical tube first and then attach to the mounting platform on

the equatorial mount as this is a personal preference.

NOTE: Never loosen any of the knobs on the telescope tube or mount other than the R.A. and DEC knobs.

Hint: For maximum rigidity of the telescope and mount, make sure the knobs/screws holding the tripod legs to the

tripod head are tight.

8

Page 9

Figure 2-16 Figure 2-17 Figure 2-18 Figure 2-19

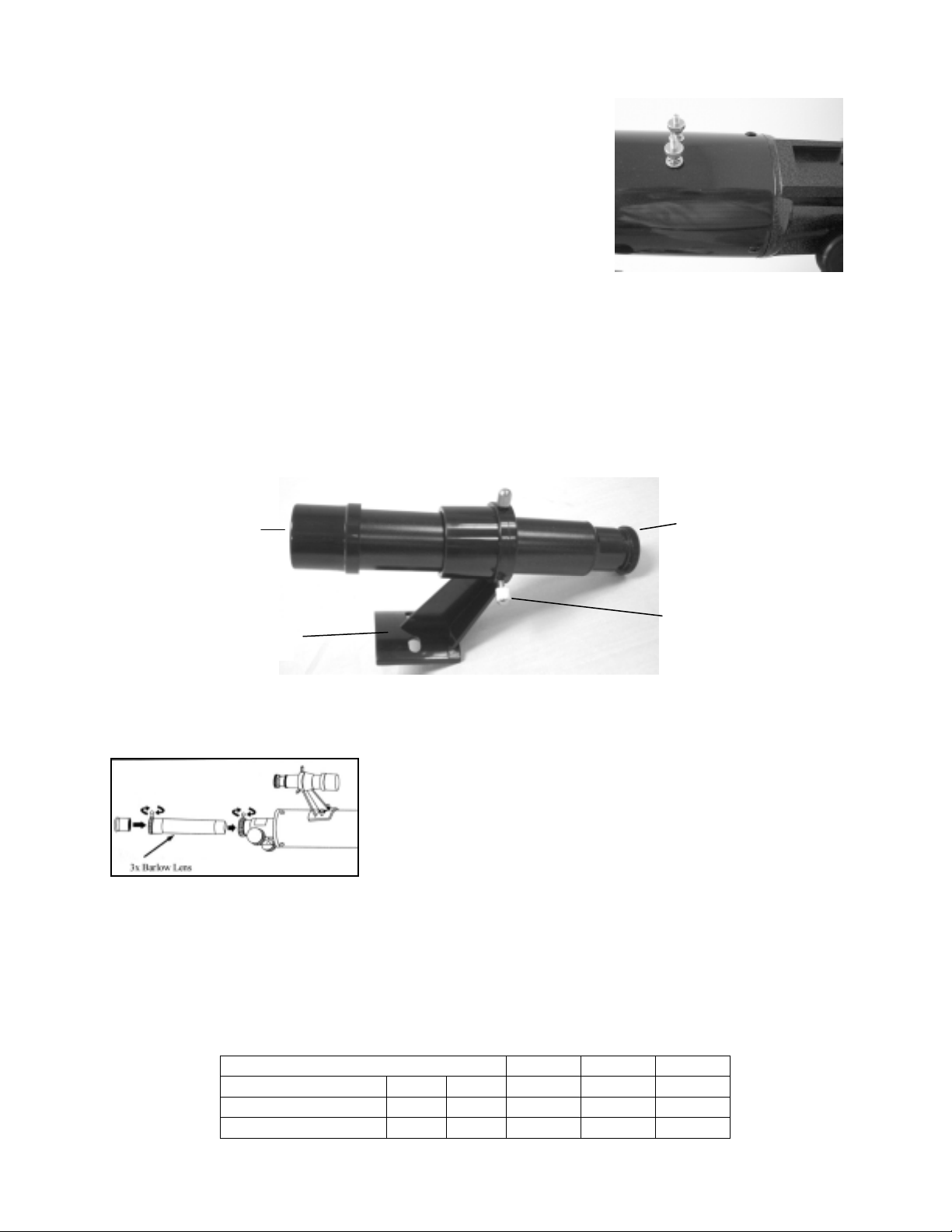

IInnssttaalllliinngg tthhee DDiiaaggoonnaall && EEyyeeppiieeccee ((RReeffrraaccttoorr))

The diagonal is a prism that diverts the light at a right angle to the light path of

the refractor. This allows you to observe in a position that is more comfortable

than if you had to look straight through. This diagonal is an erect image model

that corrects the image to be right side up and oriented correctly left-to-right

which is much easier to use for terrestrial observing. Also, the diagonal can be

rotated to any position which is most favorable for you. To install the diagonal

and eyepieces:

1. Insert the small barrel of the diagonal into the 1.25” eyepiece adapter of the

focus tube on the refractor – Figure 2-20. Make sure the two thumbscrews

on the eyepiece adapter do not protrude into the focuser tube before

installation and the plug up cap is removed from the eyepiece adapter.

2. Put the chrome barrel end of one of the eyepieces into the diagonal and

tighten the thumb screw. Again, when doing this make sure the thumb

screw is not protruding into the diagonal before inserting the eyepiece.

3. The eyepieces can be changed to other focal lengths by reversing the

Figure 2-20

procedure in step 2 above.

IInnssttaalllliinngg tthhee EEyyeeppiieeccee oonn tthhee NNeewwttoonniiaann

The eyepiece (or ocular) is an optical element that magnifies the image focused by

the telescope. Without the eyepiece it would be impossible to use the telescope

visually. Eyepieces are commonly referred to by focal length and barrel diameter.

The longer focal length (i.e., the larger the number) the lower the eyepiece

magnification (i.e., power). Generally, you will use low-to-moderate power when

viewing. For more information on how to determine power, see the section on

“Calculating Magnification”. The eyepiece fits directly into the focuser of the

Newtonian. To attach the eyepieces:

1. Make sure the thumbscrews are not protruding into the focuser tube. Then,

insert the chrome barrel of the eyepieces into the focus tube (remove the

plug up cap of the focuser first) and tighten the thumbscrews – see

Figure 2-21.

2. The 20mm eyepiece is called an erecting eyepiece since it corrects the

image so it is right side up and corrected left to right. This makes the

telescope useful for terrestrial viewing.

Figure 2-21

3. The eyepieces can be changed by reversing the procedure as described

above.

9

Page 10

IInnssttaalllliinngg tthhee FFiinnddeerrssccooppee

To install the finderscope:

1. Locate the finderscope (it will be mounted inside the finderscope

bracket) – see Figures 1-1 and 1-2.

2. Remove the knurled nuts on the threaded posts on the optical tube –

see Figure 2-22.

3. Mount the finderscope bracket by placing it over the posts protruding

from the optical tube and then holding it in place thread on the

knurled nuts and tighten them down – note that the finderscope

should be oriented so that the larger diameter lens is facing toward

the front of the optical tube.

4. Remove the lens caps from both ends of the finderscope.

AAlliiggnniinngg tthhee FFiinnddeerrssccooppee

Use the following steps to align the finderscope:

1. Locate a distant daytime object and center it in a low power (20mm) eyepiece in the main telescope.

2. Look through the finderscope (the eyepiece end of the finderscope) and take notice of the position of the

same object.

3. Without moving the main telescope, turn the adjustment thumb screws located around the finderscope

bracket until the crosshairs of the finderscope are centered on the object chosen with the main telescope.

Figure 2-22

Objective Lens

Finderscope Bracket

Figure 2-22a Finderscope with Bracket

10

IInnssttaalllliinngg aanndd UUssiinngg tthhee BBaarrllooww LLeennss

Your telescope also comes with a 3x Barlow Lens which triples the

magnifying power of each eyepiece. However, the greatly magnified

images should only be used under ideal conditions – see the “Calculating

Magnification” section of this manual.

To use the Barlow lens with refractors, remove the diagonal and insert the Barlow directly into the focuser tube.

You then insert an eyepiece into the Barlow lens for viewing. You can also, insert the diagonal into the Barlow lens

and then use an eyepiece in the diagonal but you may not be able to reach focus with all eyepieces.

For Newtonian telescopes, insert the Barlow directly into the focuser. Then, insert an eyepiece into the Barlow lens.

Note: Start by using a low power eyepiece as it will be easier to focus.

Figure 2-23

3x Barlow Lens Magnification

60EQ 70EQ 80EQ 114EQ 127EQ

w/20mm Eyepiece 135x 105x 135x 135x 150x

w/4mm Eyepiece 675x 525x 675x 675x 450x

Eyepiece

Adjustment Screws

Page 11

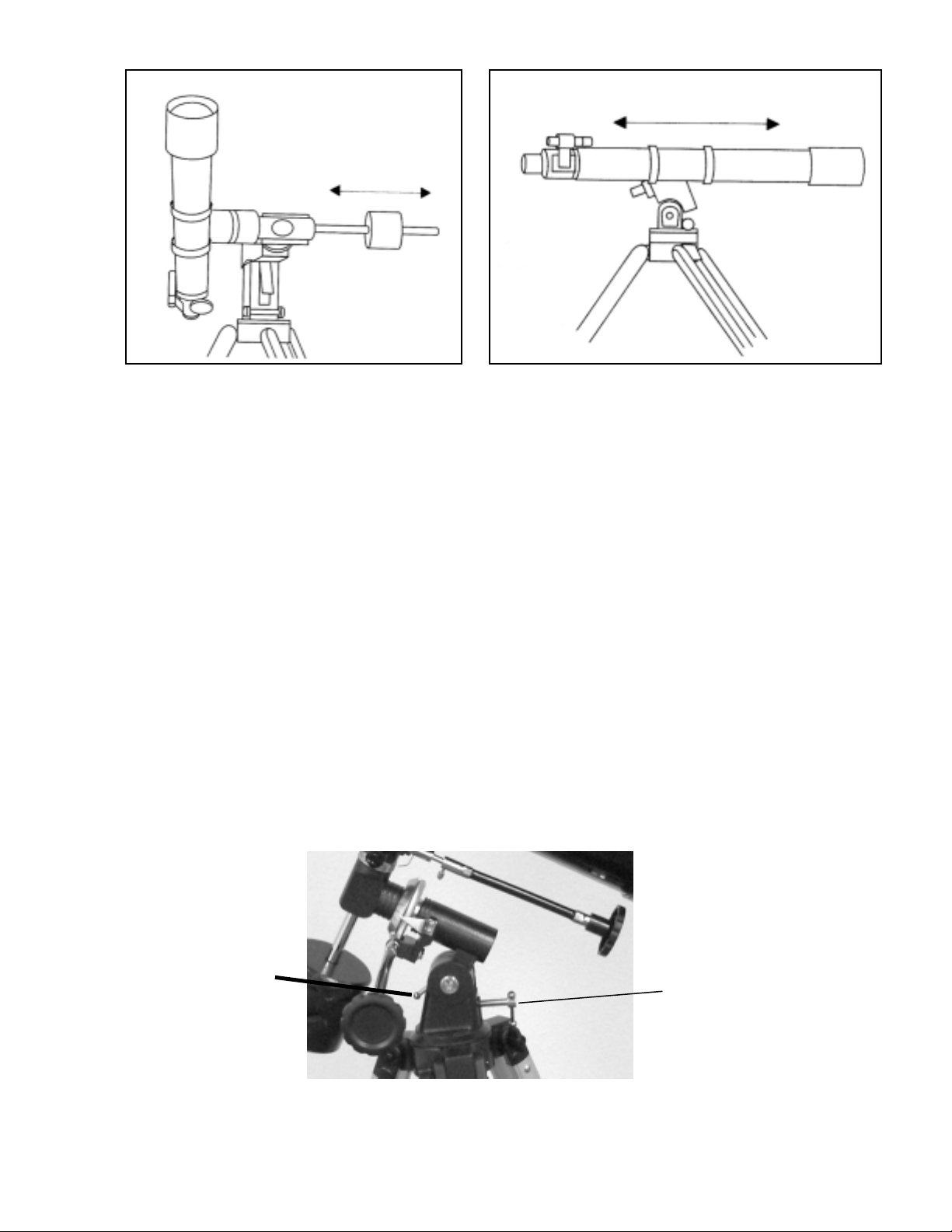

MMoovviinngg tthhee TTeelleessccooppee MMaannuuaallllyy

In order to properly use your telescope, you will need to move your

telescope manually at various portions of the sky to observe different

objects. To make rough adjustments, loosen the R.A. and Dec. locking

knobs slightly and move the telescope in the desired direction. To make

fine adjustments, when the knobs are locked you turn the slow motion

control cables.

Both the R.A. and Dec. axis have locking knobs to clutch down each axis

of the telescope. To loosen the clutches on the telescope, unlock the

locking knobs.

Figure 2-24

Dec. Lock Knob on top of Dec.circle

& R.A. Lock Knob on top of R.A.

circle

BBaallaanncciinngg tthhee MMoouunntt iinn RR..AA..

To eliminate undue stress on the mount, the telescope should be properly balanced around the polar axis. In

addition, proper balancing is crucial for accurate tracking if using an optional motor drive. To balance the mount:

1. Release the R.A. lock knob (see figure 2-24) and position the telescope off to one side of the mount (make sure

that the dovetail mounting bracket knob is tight). The counterweight bar will extend horizontally on the

opposite side of the mount (see figure 2-25).

2. Release the telescope — GRADUALLY — to see which way the telescope “rolls” or falls.

3. Loosen the counterweight locking knob on the counterweights (one at a time if you have two counterweights)

while holding the counterweight(s) and slowly release them.

4. Move the counterweight to a point where they balance the telescope (i.e., it remains stationary when the R.A.

lock knob is released).

5. Tighten the locking knobs to hold the counterweights in place.

BBaallaanncciinngg tthhee MMoouunntt iinn DDeecc..

The telescope should also be balanced on the declination axis to prevent any sudden motions when the Dec. lock

knob (Fig 2-24) is released. To balance the telescope in Dec.:

1. Release the R.A. locking knob and rotate the telescope so that it is on one side of the mount (i.e., as described in

the previous section on balancing the telescope in R.A.).

2. Lock the R.A. locking knob to hold the telescope in place.

3. Release the Dec. locking knob and rotate the telescope until the tube is parallel to the ground (figure 2-26).

4. Release the tube — GRADUALLY — to see which way it rotates around the declination axis. DO NOT LET

GO OF THE TELESCOPE TUBE COMPLETELY!

5. For the 70EQ, 80EQ, 114EQ, and 127EQ --- while holding the optical tube with one hand, loosen the knurled

screws that hold the telescope tube inside the tube rings and slide the telescope either forwards or backwards

until it remains stationary when the Dec. lock knob is released. There is no adjustment for the 60EQ as it is

fixed in place on the mounting bracket of the mount.

6. Tighten the tube ring screws firmly to hold the telescope in place.

11

Page 12

AAddjjuussttiinngg tthhee EEqquuaattoorriiaall MMoouunnt

In order for a motor drive to track accurately, the telescope’s axis of rotation must be parallel to the Earth’s axis of

rotation, a process known as polar alignment. Polar alignment is achieved NOT by moving the telescope in R.A. or

Dec., but by adjusting the mount vertically, which is called altitude. This section simply covers the correct

movement of the telescope during the polar alignment process. The actual process of polar alignment, that is

making the telescope’s axis of rotation parallel to the Earth’s, is described later in this manual in the section on

“Polar Alignment.”

AAddjjuussttiinngg tthhee MMoouunntt iinn AAllttiittuuddee

• To increase the latitude of the polar axis, loosen the latitude locking bolt slightly -- Figure 2-27.

• To increase or decrease the latitude of the polar axis, tighten or loosen the latitude adjustment screw. Then,

tighten the latitude locking bolt securely. Be careful when turning the screws to avoid hitting your fingers or

having them scrapped on other screws, etc.

The latitude adjustment on the PowerSeeker mount has a range from approximately 20° to 60°.

It is best to always make final adjustments in altitude by moving the mount against gravity (i.e. using the rear

latitude adjustment screw to raise the mount). To do this you should loosen the latitude adjustment screw and then

manually push the front of the mount down as far as it will go. Then tighten the adjustment screw to raise the mount

to the desired latitude.

Figure 2-25

t

Figure 2-26

Latitude Locking Bolt

Figure 2-27

12

Latitude Adjustment

Screw

Page 13

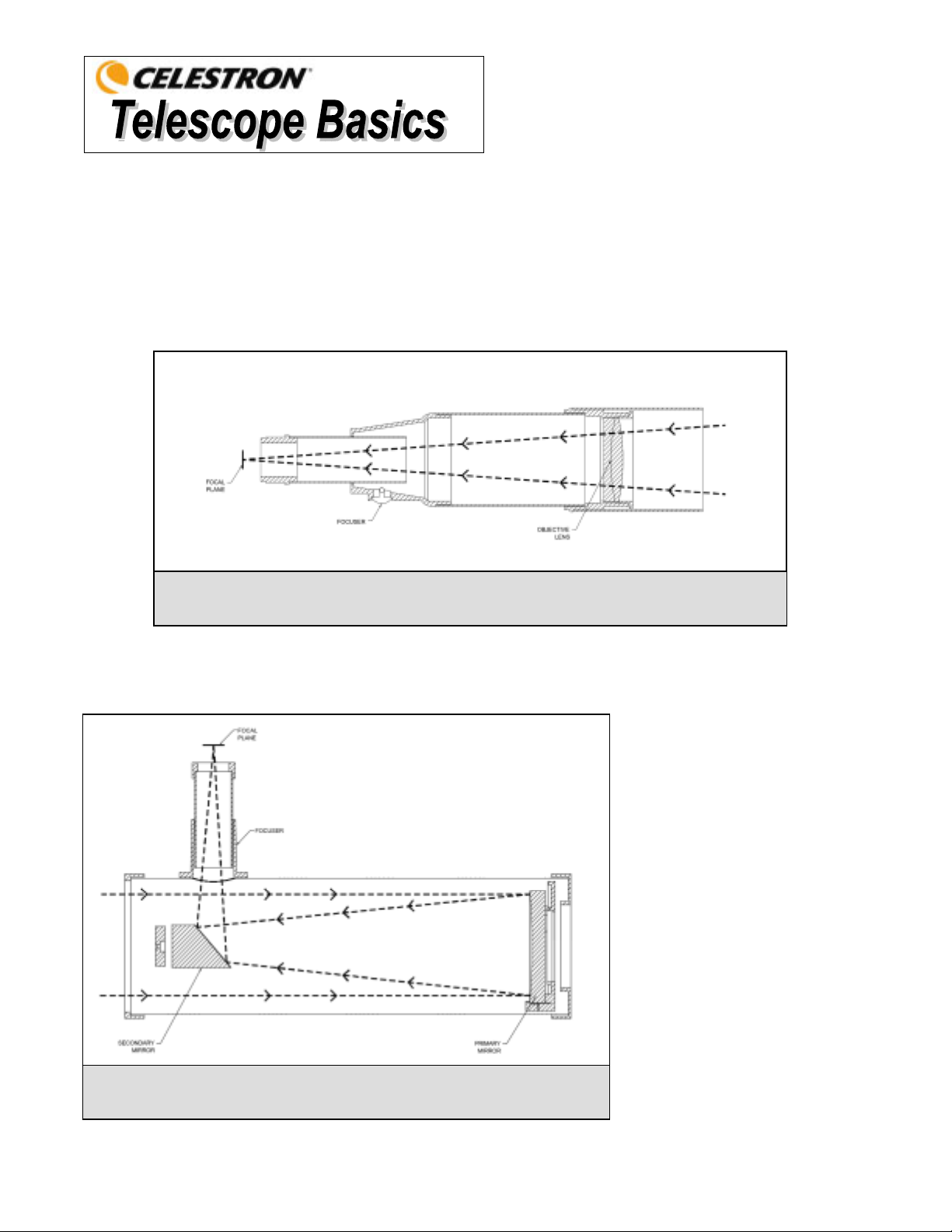

A telescope is an instrument that collects and focuses light. The nature of the optical design determines how the light is focused.

Some telescopes, known as refractors, use lenses, and other telescopes, known as reflectors (Newtonians), use mirrors.

Developed in the early 1600s, the refractor is the oldest telescope design. It derives its name from the method it uses to focus

incoming light rays. The refractor uses a lens to bend or refract incoming light rays, hence the name (see Figure 3-1). Early

designs used single element lenses. However, the single lens acts like a prism and breaks light down into the colors of the

rainbow, a phenomenon known as chromatic aberration. To get around this problem, a two-element lens, known as an

achromat, was introduced. Each element has a different index of refraction allowing two different wavelengths of light to

be focused at the same point. Most two-element lenses, usually made of crown and flint glasses, are corrected for red and

green light. Blue light may still be focused at a slightly different point.

A cutaway view of the light path of the Refractor optical design

Figure 3-1

A Newtonian reflector uses a single concave mirror as its primary. Light enters the tube traveling to the mirror at the back

end. There light is bent forward in the tube to a single point, its focal point. Since putting your head in front of the telescope

to look at the image with an eyepiece would keep the reflector from working, a flat mirror called a diagonal intercepts the

light and points it out the side of the tube at right angles to the tube. The eyepiece is placed there for easy viewing.

Newtonian Reflector telescopes

replace heavy lenses with mirrors to

collect and focus the light, providing

much more light-gathering power for

the money spent. Because the light

path is intercepted and reflected out

to the side, you can have focal

lengths up to 1000mm and still enjoy

a telescope that is relatively compact

and portable. A Newtonian Reflector

telescope offers such impressive

light-gathering characteristics you

can take a serious interest in deep

space astronomy even on a modest

budget. Newtonian Reflector

telescopes do require more care and

maintenance because the primary

mirror is exposed to air and dust.

However, this small drawback does

not hamper this type of telescope’s

Figure 3-2

Cutaway view of the light path of the Newtonian optical design

popularity with those who want an

economical telescope that can still

resolve faint, distant objects.

13

Page 14

n

IImmaaggee OOrriieennttaattiioon

The image orientation changes depending on how the eyepiece is inserted into the telescope. When using a star

diagonal with refractors, the image is right-side-up, but reversed from left-to-right (i.e., mirror image). If inserting

the eyepiece directly into the focuser of a refractor (i.e., without the diagonal), the image is upside-down and

reversed from left-to-right (i.e., inverted). However, when using the PowerSeeker refractor and the standard erect

image diagonal, the image is correctly oriented in every aspect.

Newtonian reflectors produce a right-side-up image but the image will appear rotated based on the location of the

eyepiece holder in relation to the ground. However, by using the erect image eyepiece supplied with the

PowerSeeker Newtonians, the image is correctly oriented

Image orientation as seen with the

unaided eye & using erecting

devices on refractors & Newtonians.

FFooccuussiinngg

To focus your refractor or Newtonian telescope, simply turn the focus knob located directly below the eyepiece

holder (see Figures 2-20 and 2-21). Turning the knob clockwise allows you to focus on an object that is farther

than the one you are currently observing. Turning the knob counterclockwise from you allows you to focus on an

object closer than the one you are currently observing.

Note: If you wear corrective lenses (specifically glasses), you may want to remove them when observing with an

eyepiece attached to the telescope. However, when using a camera you should always wear corrective lenses to

ensure the sharpest possible focus. If you have astigmatism, corrective lenses must be worn at all times.

CCaallccuullaattiinngg MMaaggnniiffiiccaattiioonn

You can change the power of your telescope just by changing the eyepiece (ocular). To determine the

magnification of your telescope, simply divide the focal length of the telescope by the focal length of the eyepiece

used. In equation format, the formula looks like this:

Focal Length of Telescope (mm)

Magnification =

Focal Length of Eyepiece (mm)

Let’s say, for example, you are using the 20mm eyepiece that came with your telescope. To determine the

magnification you divide the focal length of your telescope (the PowerSeeker 80EQ for this example has a focal

length of 900mm) by the focal length of the eyepiece, 20mm. Dividing 900 by 20 yields a magnification of 45x.

Reversed from left to right, as

viewed using a Star Diagonal on a

refractor.

Figure 3-3

Inverted image, normal with

Newtonians & as viewed with

eyepiece directly in a refractor.

Although the power is variable, each instrument under average skies has a limit to the highest useful magnification.

The general rule is that 60 power can be used for every inch of aperture. For example, the PowerSeeker 80EQ is

3.1” inches in diameter. Multiplying 3.1 by 80 gives a maximum useful magnification of 189 power. Although this

is the maximum useful magnification, most observing is done in the range of 20 to 35 power for every inch of

aperture which is 62 to 109 times for the PowerSeeker 80EQ telescope. You can determine the magnification for

your telescope the same way.

14

Page 15

DDeetteerrmmiinniinngg FFiieelldd ooff VViieeww

Determining the field of view is important if you want to get an idea of the angular size of the object you are

observing. To calculate the actual field of view, divide the apparent field of the eyepiece (supplied by the eyepiece

manufacturer) by the magnification. In equation format, the formula looks like this:

Apparent Field of Eyepiece

True Angular Field =

Magnification

As you can see, before determining the field of view, you must calculate the magnification. Using the example in

the previous section, we can determine the field of view using the same 20mm eyepiece that is supplied standard

with the PowerSeeker 80EQ telescope. The 20mm eyepiece has an apparent field of view of 50°. Divide the 50° by

the magnification, which is 45 power. This yields an actual (true) field of 1.1°.

To convert degrees to feet at 1,000 yards, which is more useful for terrestrial observing, simply multiply by 52.5.

Continuing with our example, multiply the angular field of 1.1° by 52.5. This produces a linear field width of 58

feet at a distance of one thousand yards.

GGeenneerraall OObbsseerrvviinngg HHiinnttss

When working with any optical instrument, there are a few things to remember to ensure you get the best possible

image.

Never look through window glass. Glass found in household windows is optically imperfect, and as a

y

result, may vary in thickness from one part of a window to the next. This inconsistency can and will

affect the ability to focus your telescope. In most cases you will not be able to achieve a truly sharp

image, while in some cases, you may actually see a double image.

y

Never look across or over objects that are producing heat waves. This includes asphalt parking lots on

hot summer days or building rooftops.

Hazy skies, fog, and mist can also make it difficult to focus when viewing terrestrially. The amount of

y

detail seen under these conditions is greatly reduced.

y If you wear corrective lenses (specifically glasses), you may want to remove them when observing with

an eyepiece attached to the telescope. When using a camera, however, you should always wear

corrective lenses to ensure the sharpest possible focus. If you have astigmatism, corrective lenses must

be worn at all times.

15

Page 16

Up to this point, this manual covered the assembly and basic operation of your telescope. However, to understand your telescope

more thoroughly, you need to know a little about the night sky. This section deals with observational astronomy in general and

includes information on the night sky and polar alignment.

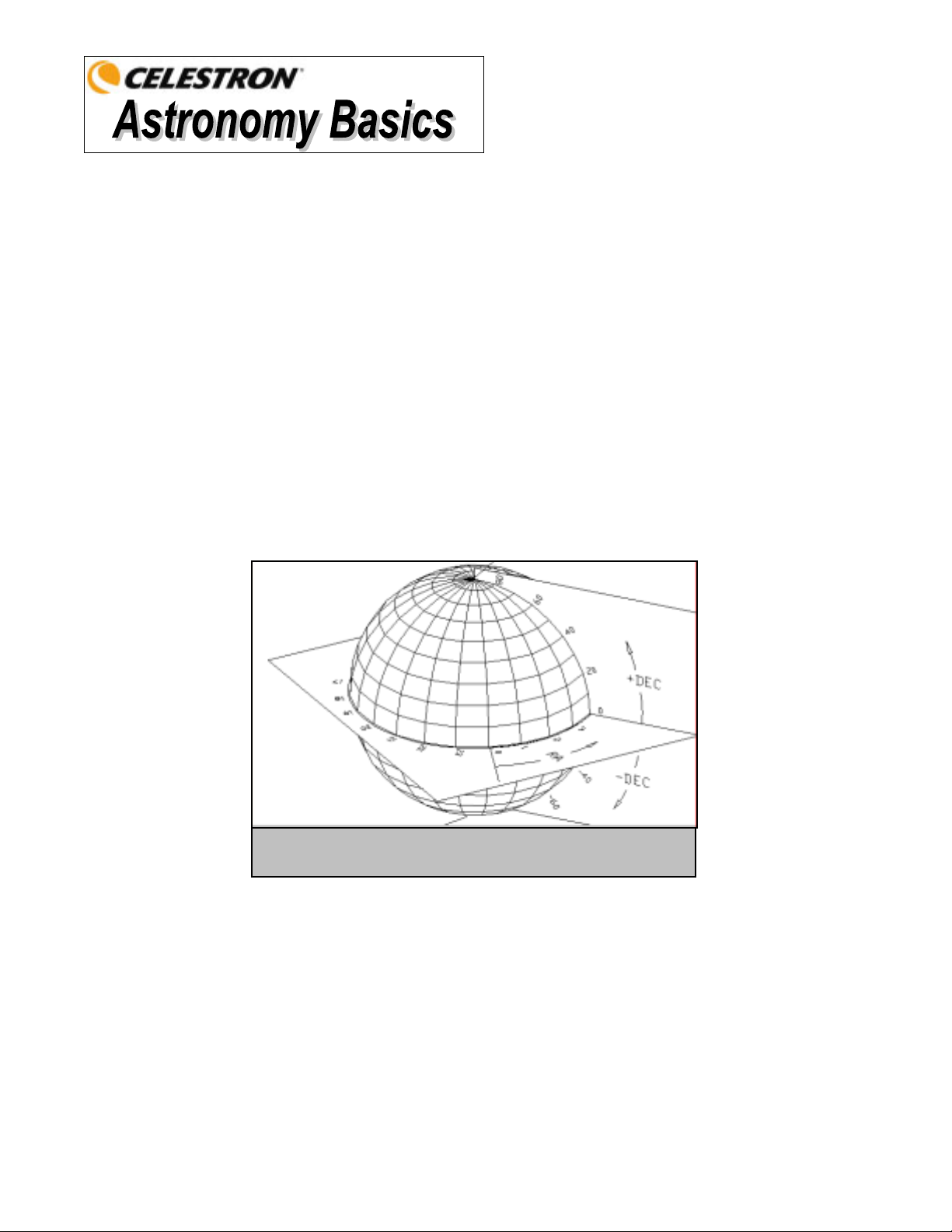

TThhee CCeelleessttiiaall CCoooorrddiinnaattee SSyysstteemm

To help find objects in the sky, astronomers use a celestial coordinate system that is similar to our geographical co-ordinate

system here on Earth. The celestial coordinate system has poles, lines of longitude and latitude, and an equator. For the most

part, these remain fixed against the background stars.

The celestial equator runs 360 degrees around the Earth and separates the northern celestial hemisphere from the southern. Like

the Earth's equator, it bears a reading of zero degrees. On Earth this would be latitude. However, in the sky this is referred to as

declination, or DEC for short. Lines of declination are named for their angular distance above and below the celestial equator.

The lines are broken down into degrees, minutes of arc, and seconds of arc. Declination readings south of the equator carry a

minus sign (-) in front of the coordinate and those north of the celestial equator are either blank (i.e., no designation) or preceded

by a plus sign (+).

The celestial equivalent of longitude is called Right Ascension, or R.A. for short. Like the Earth's lines of longitude, they run

from pole to pole and are evenly spaced 15 degrees apart. Although the longitude lines are separated by an angular distance, they

are also a measure of time. Each line of longitude is one hour apart from the next. Since the Earth rotates once every 24 hours,

there are 24 lines total. As a result, the R.A. coordinates are marked off in units of time. It begins with an arbitrary point in the

constellation of Pisces designated as 0 hours, 0 minutes, 0 seconds. All other points are designated by how far (i.e., how long)

they lag behind this coordinate after it passes overhead moving toward the west.

The celestial sphere seen from the outside showing R.A. and DEC.

Figure 4-1

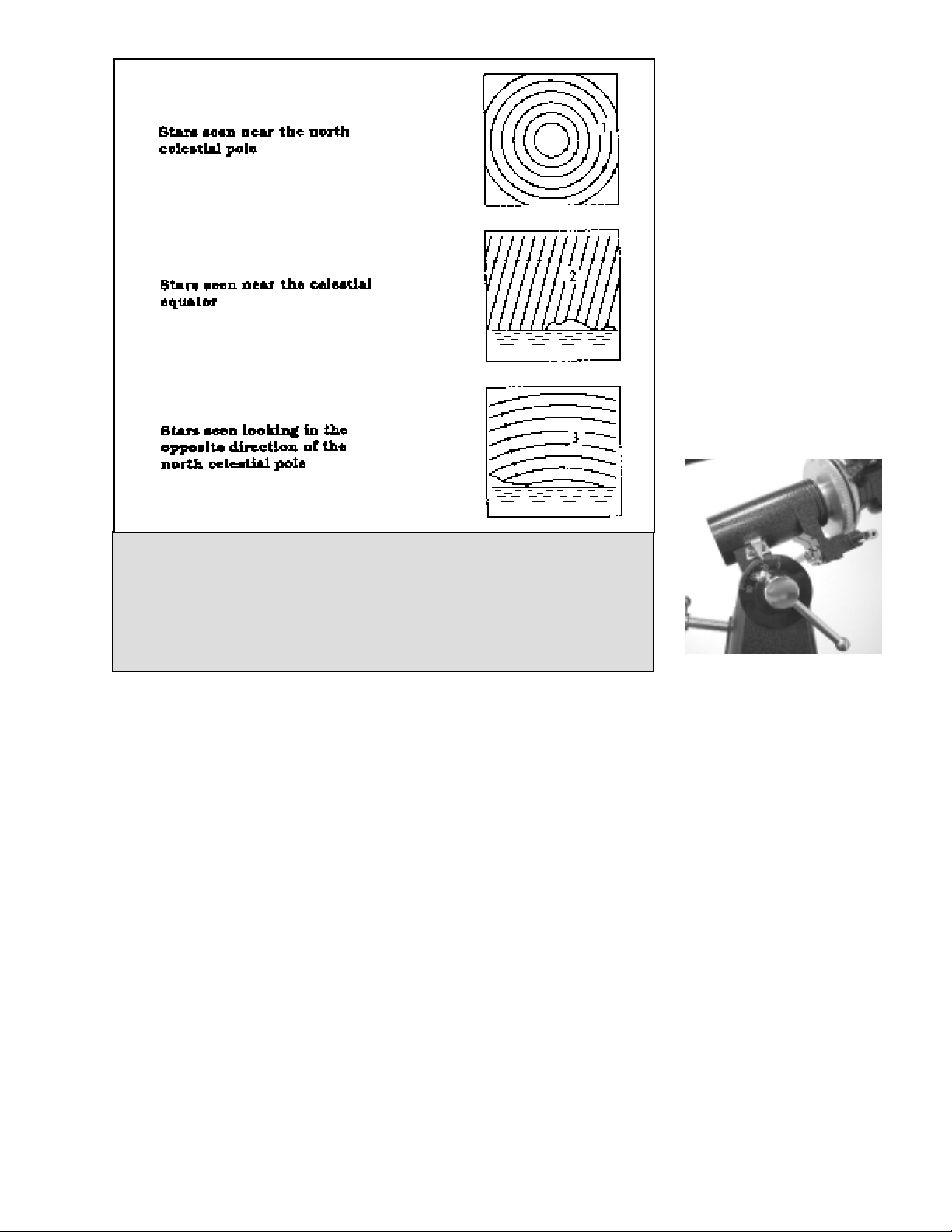

MMoottiioonn ooff tthhee SSttaarrss

The daily motion of the Sun across the sky is familiar to even the most casual observer. This daily trek is not the Sun

moving as early astronomers thought, but the result of the Earth's rotation. The Earth's rotation also causes the stars to do

the same, scribing out a large circle as the Earth completes one rotation. The size of the circular path a star follows

depends on where it is in the sky. Stars near the celestial equator form the largest circles rising in the east and setting in

the west. Moving toward the north celestial pole, the point around which the stars in the northern hemisphere appear to

rotate, these circles become smaller. Stars in the mid-celestial latitudes rise in the northeast and set in the northwest. Stars

at high celestial latitudes are always above the horizon, and are said to be circumpolar because they never rise and never

set. You will never see the stars complete one circle because the sunlight during the day washes out the starlight.

However, part of this circular motion of stars in this region of the sky can be seen by setting up a camera on a tripod and

opening the shutter for a couple hours. The timed exposure will reveal semicircles that revolve around the pole. (This

description of stellar motions also applies to the southern hemisphere except all stars south of the celestial equator move

around the south celestial pole.)

Page 17

pp

Figure 4-2

All stars appear to rotate around the celestial poles. However, the appearance of this

motion varies depending on where you are looking in the sky. Near the north celestial pole

the stars scribe out recognizable circles centered on the pole (1). Stars near the celestial

equator also follow circular paths around the pole. But, the complete path is interrupted by

the horizon. These appear to rise in the east and set in the west (2). Looking toward the

opposite pole, stars curve or arc in the opposite direction scribing a circle around the

o

osite pole (3).

e

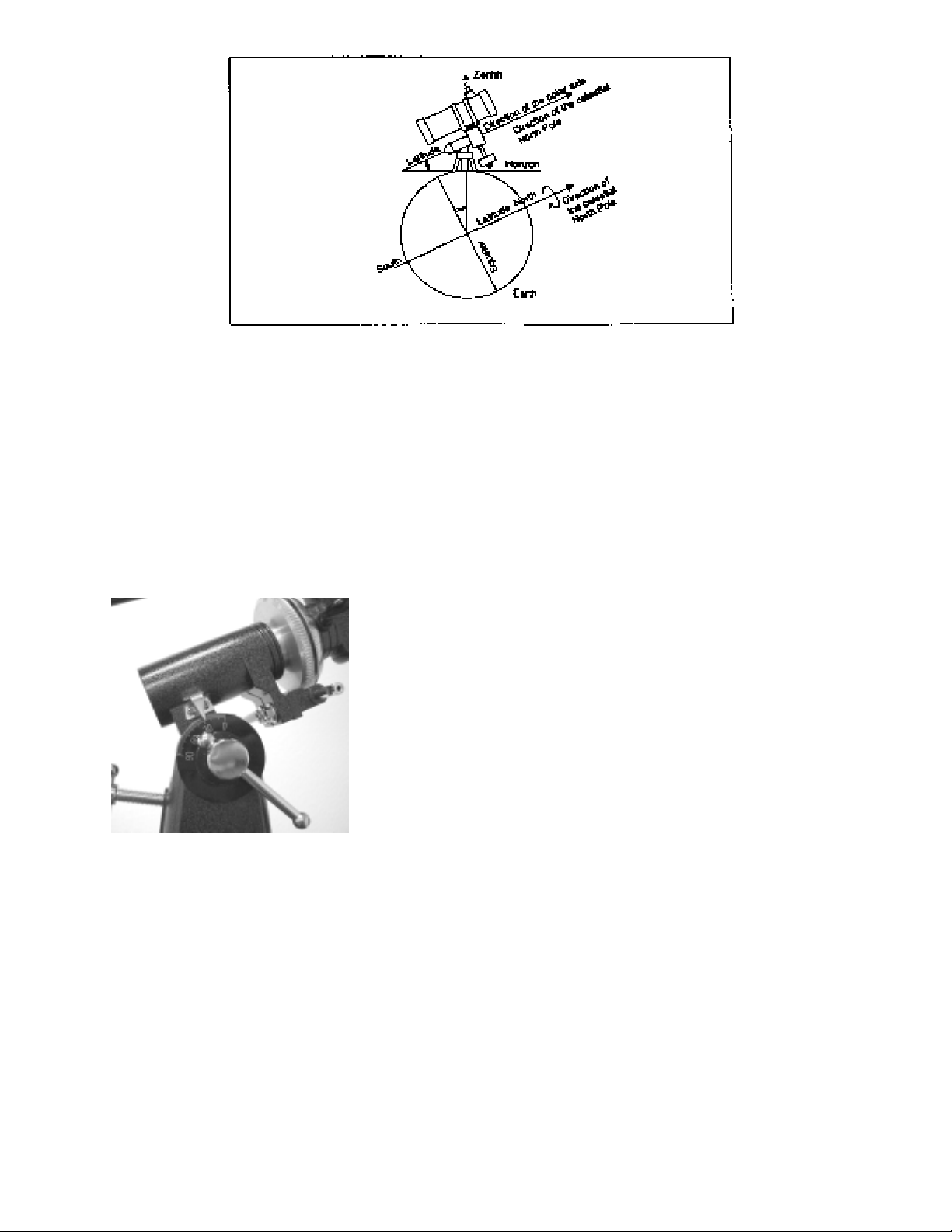

PPoollaarr AAlliiggnnmmeenntt wwiitthh tthhee LLaattiittuuddee SSccaalle

The easiest way to polar align a telescope is with a latitude scale. Unlike other methods that require you to find the celestial pole

by identifying certain stars near it, this method works off of a known constant to determine how high the polar axis should be

pointed. The PowerSeeker equatorial mount can be adjusted from about 20 to 60 degrees (see figure 4-3).

The constant, mentioned above, is a relationship between your latitude and the angular distance the celestial pole is above the

northern (or southern) horizon. The angular distance from the northern horizon to the north celestial pole is always equal to

your latitude. To illustrate this, imagine that you are standing on the north pole, latitude +90°. The north celestial pole, which

has a declination of +90°, would be directly overhead (i.e., 90 above the horizon). Now, let’s say that you move one degree

south — your latitude is now +89° and the celestial pole is no longer directly overhead. It has moved one degree closer toward

the northern horizon. This means the pole is now 89° above the northern horizon. If you move one degree further south, the

same thing happens again. You would have to travel 70 miles north or south to change your latitude by one degree. As you can

see from this example, the distance from the northern horizon to the celestial pole is always equal to your latitude.

If you are observing from Los Angeles, which has a latitude of 34°, then the celestial pole is 34° above the northern horizon.

All a latitude scale does then is to point the polar axis of the telescope at the right elevation above the northern (or southern)

horizon.

To align your telescope:

1. Make sure the polar axis of the mount is pointing due north. Use a landmark that you know faces north.

2. Level the tripod. Leveling the tripod is only necessary if using this method of polar alignment.

3. Adjust the mount in altitude until the latitude indicator points to your latitude. Moving the mount affects the angle the

polar axis is pointing. For specific information on adjusting the equatorial mount, please see the section “Adjusting the

Mount.”

This method can be done in daylight, thus eliminating the need to fumble around in the dark. Although this method does NOT

put you directly on the pole, it will limit the number of corrections you will make when tracking an object.

17

Figure 4-3

Page 18

s

PPooiinnttiinngg aatt PPoollaarriis

This method utilizes Polaris as a guidepost to the north celestial pole. Since Polaris is less than a degree from the celestial

pole, you can simply point the polar axis of your telescope at Polaris. Although this is by no means perfect alignment, it

does get you within one degree. Unlike the previous method, this must be done in the dark when Polaris is visible.

1. Set the telescope up so that the polar axis is pointing north – see Figure 4-6.

2. Loosen the Dec. clutch knob and move the telescope so that the tube is parallel to the polar axis. When this is done,

the declination setting circle will read +90°. If the declination setting circle is not aligned, move the telescope so that

the tube is parallel to the polar axis.

3. Adjust the mount in altitude and/or azimuth until Polaris is in the field of view of the finder.

Remember, while Polar aligning, do NOT move the telescope in R.A. or DEC. You do not want to move the

telescope itself, but the polar axis. The telescope is used simply to see where the polar axis is pointing.

Like the previous method, this gets you close to the pole but not directly on it. The following method helps improve your

accuracy for more serious observations and photography.

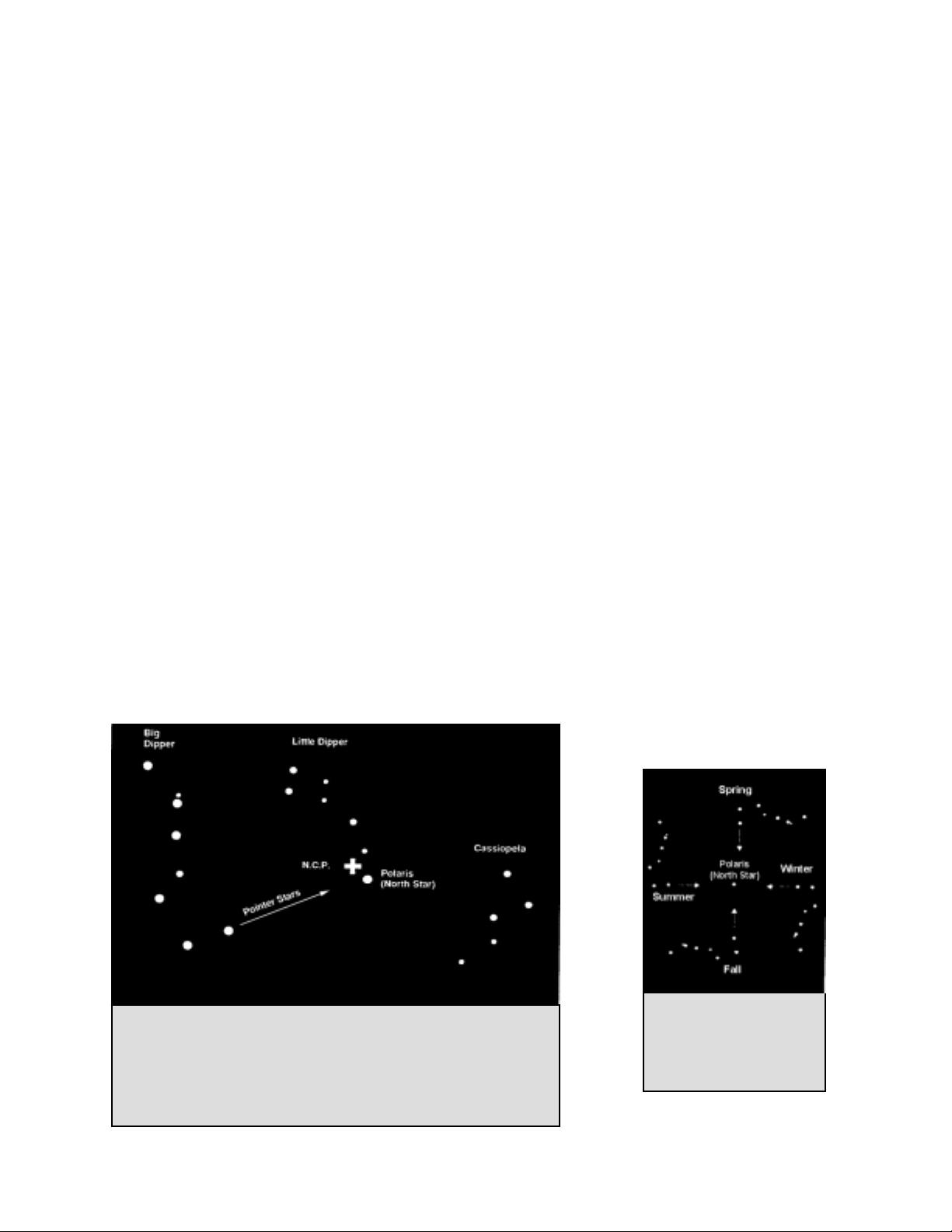

FFiinnddiinngg tthhee NNoorrtthh CCeelleessttiiaall PPoollee

In each hemisphere, there is a point in the sky around which all the other stars appear to rotate. These points are called the

celestial poles and are named for the hemisphere in which they reside. For example, in the northern hemisphere all stars

move around the north celestial pole. When the telescope's polar axis is pointed at the celestial pole, it is parallel to the

Earth's rotational axis.

Many methods of polar alignment require that you know how to find the celestial pole by identifying stars in the area. For

those in the northern hemisphere, finding the celestial pole is not too difficult. Fortunately, we have a naked eye star less

than a degree away. This star, Polaris, is the end star in the handle of the Little Dipper. Since the Little Dipper

(technically called Ursa Minor) is not one of the brightest constellations in the sky, it may be difficult to locate from urban

areas. If this is the case, use the two end stars in the bowl of the Big Dipper (the pointer stars). Draw an imaginary line

through them toward the Little Dipper. They point to Polaris (see Figure 4-5). The position of the Big Dipper (Ursa

Major) changes during the year and throughout the course of the night (see Figure 4-4). When the Big Dipper is low in the

sky (i.e., near the horizon), it may be difficult to locate. During these times, look for Cassiopeia (see Figure 4-5).

Observers in the southern hemisphere are not as fortunate as those in the northern hemisphere. The stars around the south

celestial pole are not nearly as bright as those around the north. The closest star that is relatively bright is Sigma Octantis.

This star is just within naked eye limit (magnitude 5.5) and lies about 59 arc minutes from the pole.

Definition:The north celestial pole is the point in the northern hemisphere around which all stars appear to rotate. The

counterpart in the southern hemisphere is referred to as the south celestial pole.

Figure 4-5

The two stars in the front of the bowl of the Big Dipper point to Polaris

which is less than one degree from the true (north) celestial pole.

Cassiopeia, the “W” shaped constellation, is on the opposite side of the

pole from the Big Dipper. The North Celestial Pole (N.C.P.) is marked

by the “+” sign.

Figure 4-4

The position of the Big

Dipper changes throughout

the year and the night.

18

Page 19

Figure 4-6

Aligning the equatorial mount to the polar axis of the Earth

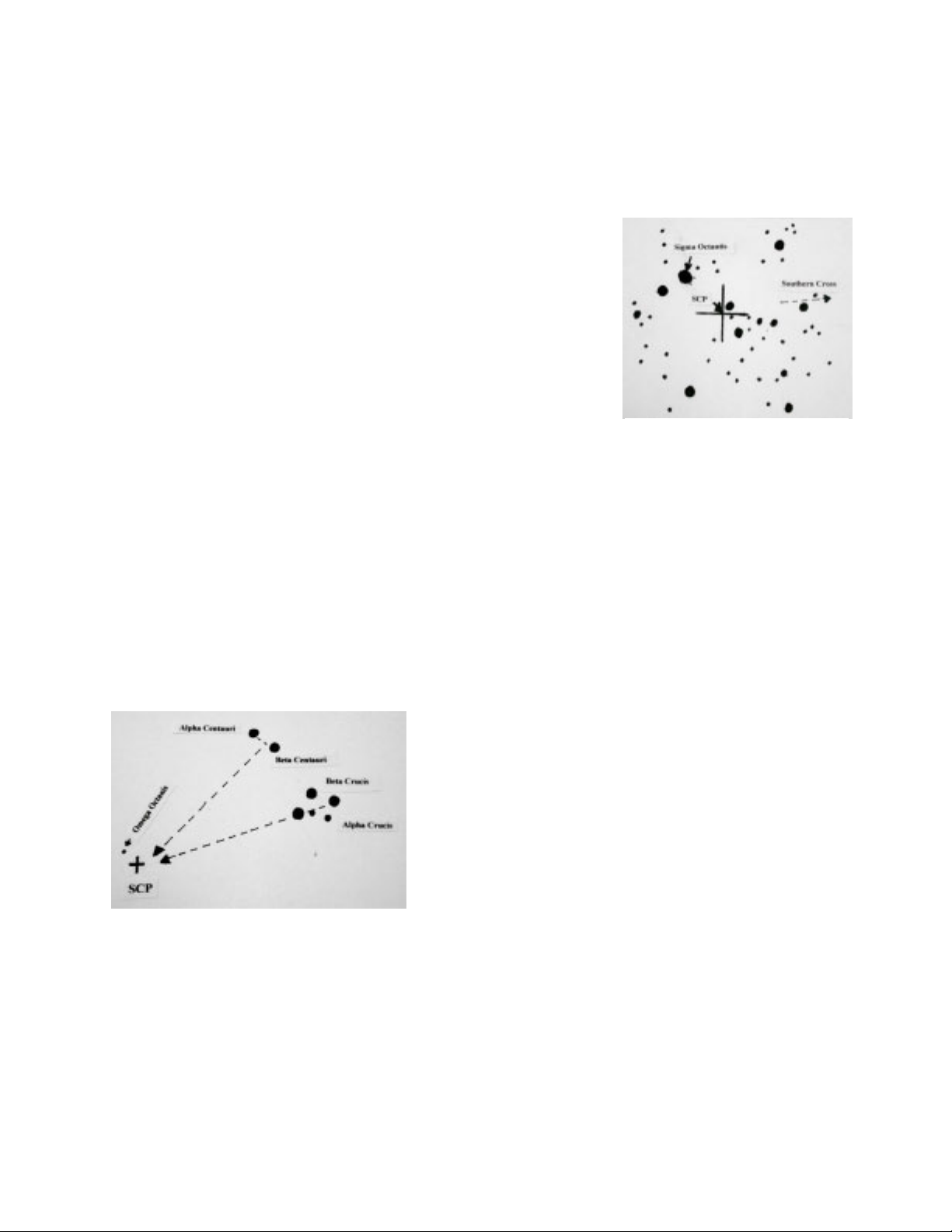

PPoollaarr AAlliiggnnmmeenntt iinn tthhee SSoouutthheerrnn HHeemmiisspphheerree

Polar alignment to the South Celestial Pole (SCP) is a little more challenging due to the fact that there is no very

bright star close to it like Polaris is in the NCP. There are various ways to polar align your telescope and for casual

observing the methods below are adequate and will get you reasonably close to the SCP.

Polar Alignment with the Latitude Scale

The easiest way to polar align a telescope is with a latitude scale. Unlike other methods that require you to find the

celestial pole by identifying certain stars near it, this method works off of a known constant to determine how high

the polar axis should be pointed.

The constant, mentioned above, is a relationship between your latitude and

the angular distance the celestial pole is above the southern horizon. The

angular distance from the southern horizon to the south celestial pole is

always equal to your latitude. To illustrate this, imagine that you are

standing on the south pole, latitude -90°. The south celestial pole, which

has a declination of -90°, would be directly overhead (i.e., 90° above the

horizon). Now, let’s say that you move one degree north — your latitude is

now -89° and the celestial pole is no longer directly overhead. It has moved

one degree closer toward the southern horizon. This means the pole is now

89° above the southern horizon. If you move one degree further north, the

same thing happens again. You would have to travel 70 miles north or south

to change your latitude by one degree. As you can see from this example,

the distance from the southern horizon to the celestial pole is always equal

to your latitude.

Figure 4-7

If you are observing from Sydney, which has a latitude of -34°, then the celestial pole is 34° above the southern

horizon. All a latitude scale does then is to point the polar axis of the telescope at the right elevation above the

southern horizon. To align your telescope:

1. Make sure the polar axis of the mount is pointing due south. Use a landmark that you know faces south.

2. Level the tripod. Leveling the tripod is only necessary if using this method of polar alignment.

3. Adjust the mount in altitude until the latitude indicator points to your latitude. Moving the mount affects the

angle the polar axis is pointing. For specific information on adjusting the equatorial mount, please see the

section “Adjusting the Mount” in your telescope manual.

4. If the above is done correctly, you should be able to observe near the pole through the finderscope and a low

power eyepiece.

This method can be done in daylight, thus eliminating the need to fumble around in the dark. Although this method

does NOT put you directly on the pole, it will limit the number of corrections you will make when tracking an

object.

19

Page 20

Pointing at Sigma Octantis

This method utilizes Sigma Octantis as a guidepost to the celestial pole. Since Sigma Octantis is about 1° degree

from the south celestial pole, you can simply point the polar axis of your telescope at Sigma Octantis. Although this

is by no means perfect alignment, it does get you within one degree. Unlike the previous method, this must be done

in the dark when Sigma Octantis is visible. Sigma Octantis has a magnitude of 5.5 and may be difficult to see and a

binocular may be helpful as well as the finderscope.

1. Set the telescope up so that the polar axis is pointing south.

2. Loosen the DEC clutch knob and move the telescope so that the tube is

parallel to the polar axis. When this is done, the declination setting circle

will read 90°. If the declination setting circle is not aligned, move the

telescope so that the tube is parallel to the polar axis.

3. Adjust the mount in altitude and/or azimuth until Sigma Octantis is in the

field of view of the finder.

4. If the above is done correctly, you should be able to observe near the pole

through the finderscope and a low power eyepiece.

Remember, while Polar aligning, do NOT move the telescope in R.A. or

DEC. You do not want to move the telescope itself, but the polar axis. The

telescope is used simply to see where the polar axis is pointing.

Like the previous method, this gets you close to the pole but not directly on it.

FFiinnddiinngg tthhee SSoouutthh CCeelleessttiiaall PPoollee ((SSCCPP))

This method helps improve your polar alignment and gets you closer to the pole that the above methods. This will

improve your accuracy for more serious observations and photography.

In each hemisphere, there is a point in the sky around which all the other stars appear to rotate. These points are

called the celestial poles and are named for the hemisphere in which they reside. For example, in the southern

hemisphere all stars move around the south celestial pole. When the telescope's polar axis is pointed at the celestial

pole, it is parallel to the Earth's rotational axis.

Many methods of polar alignment require that you know how to

find the celestial pole by identifying stars in the area. Observers in

the southern hemisphere are not as fortunate as those in the

northern hemisphere. The stars around the south celestial pole are

not nearly as bright as those around the north celestial pole. The

closest star that is relatively bright is Sigma Octantis. This star is

just within naked eye limit (magnitude 5.5) and lies about 1° from

the south celestial pole but can be difficult to locate.

Figure 4-8

Figure 4-9

Therefore, with this method, you will use star patterns to find the south celestial pole. Draw an imaginary line

toward the SCP through Alpha Crucis and Beta Crucis (which are in the Southern Cross). Draw another imaginary

line toward the SCP at a right angle to a line connecting Alpha Centauri and Beta Centauri. The intersecting of

these two imaginary lines will point you close to the south celestial pole.

20

Page 21

AAlliiggnniinngg tthhee SSeettttiinngg CCiirrcclleess

Before you can use the setting circles to find objects in the sky you

need to align the R.A. setting circle which is incremented in minutes.

The declination setting circle is scaled in degrees and it is factory set

and should not need any adjustments. On the R.A. setting circle there

are two sets of numbers on the dial – one for the northern hemisphere

(top) and one for the southern hemisphere (bottom).

In order to align the R.A. setting circle, you will need to know the

names of a few of the brightest stars in the sky. If you don’t, they can

be learned by using the Celestron Sky Maps (#93722) or consulting a

current astronomy magazine.

To align the R.A. setting circle:

1. Locate a bright star near the celestial equator. The farther you are from the celestial pole the better your reading

on the R.A. setting circle will be. The star you choose to align the setting circle with should be a bright one

whose coordinates are known and easy to look up.

2. Center the star in the finderscope.

3. Look through the main telescope and see if the star is in the field. If not, find it and center it.

4. Look up the coordinates of the star.

5. Rotate the circle until the proper coordinate lines up with the R.A. indicator. The R.A. setting circle should

rotate freely.

Dec. Circle @ top and R.A. Circle @ bottom

Figure 4-10

NOTE: Because the R.A. setting circle does NOT move as the telescope moves in R.A., the setting circle must

be aligned each time you want to use it to find an object. However, you do not need to use a star each

time. Instead, you can use the coordinates of the object you are currently observing.

Once the circles are aligned you can use them to find any objects with known coordinates. The accuracy of your

setting circles is directly related to the accuracy of your polar alignment.

1. Select an object to observe. Use a seasonal star chart to make sure the object you chose is above the horizon.

As you become more familiar with the night sky, this will no longer be necessary.

2. Look up the coordinates in a star atlas or reference book.

3. Hold the telescope and release the Dec. lock knob.

4. Move the telescope in declination until the indicator is pointing at the correct declination coordinate.

5. Lock the Dec. lock knob to prevent the telescope from moving.

6. Hold the telescope and release the R.A. lock knob.

7. Move the telescope in R.A. until the indicator points to the correct coordinate.

8. Lock the R.A. lock knob to prevent the telescope from slipping in R.A.

9. Look through the finderscope to see if you have located the object and center the object in the finderscope.

10. Look in the main optics and the object should be there. For some of the fainter objects, you may not be able to

see them in the finderscope. When this happens, it is a good idea to have a star chart of the area so that you can

“star hop” through the field to your target.

11. This process can be repeated for each object throughout any given night.

21

Page 22

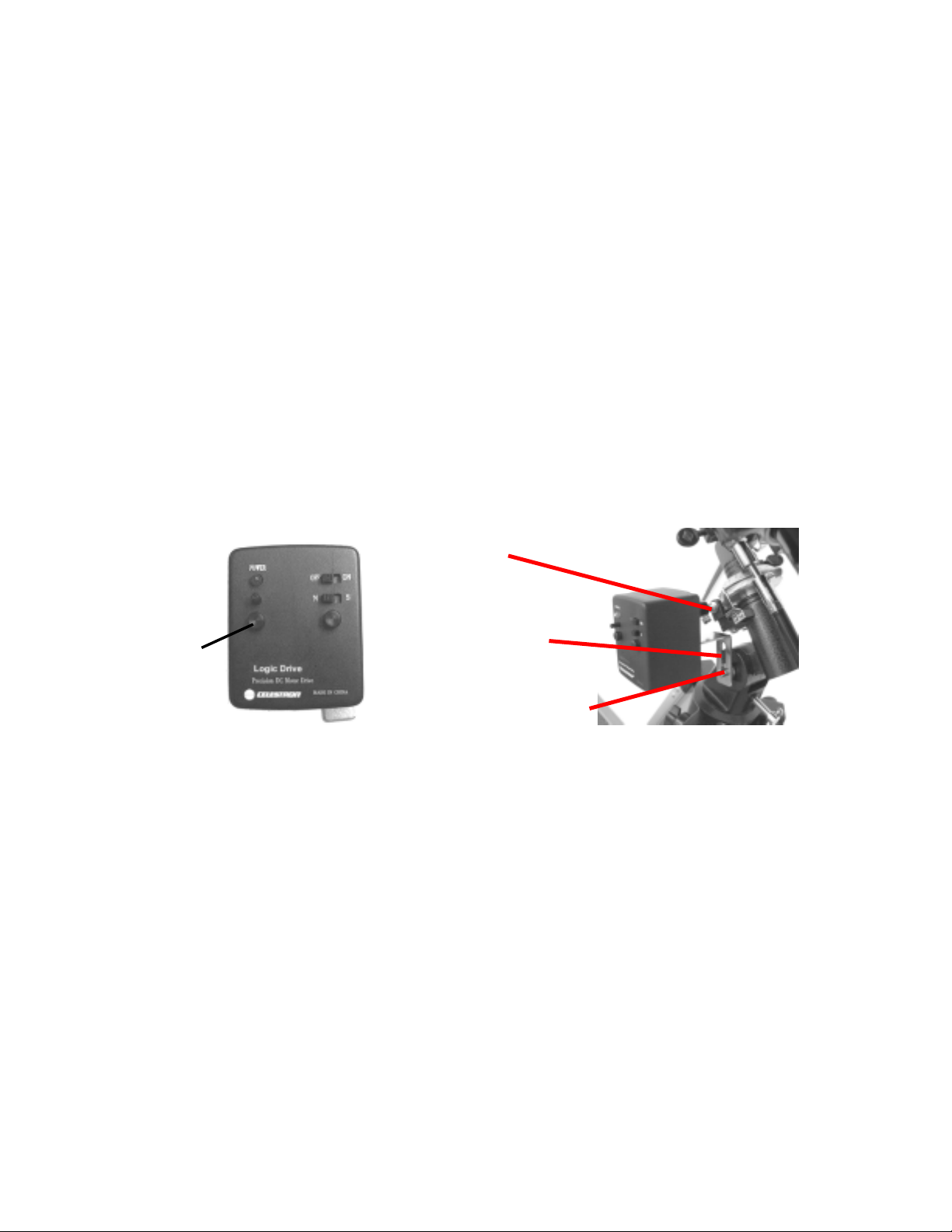

MMoottoorr DDrriivvee

To allow tracking of celestial objects, Celestron offers a single axis DC motor drive for the PowerSeeker equatorial

mount. Once polar aligned, the motor drive will accurately track objects in Right Ascension as they move across the

sky. Only minor adjustments in Declination will be necessary to keep celestial objects centered in the eyepiece for

long periods of time. Some models come standard with this motor drive and it is sold as an optional accessory

( Model # 93514 ) for other models.

Installation of the Motor Drive – for those purchasing it as an optional accessory.

The motor drive attaches to the PowerSeeker equatorial mount via a flexible coupler that mounts to the R.A. slow

motion shaft and a motor bracket that holds the motor in place. To install the motor drive see the description and

photos below:

1. Make sure the R.A. slow motion cable is attached to the R.A. shaft opposite of the latitude scale.

2. Remove the Allen head bolt located on the side of the polar shaft.

3. Slide the open end of the flexible motor coupler over the R.A. shaft. Make sure that the screw on the flexible

motor coupler is positioned over the flat portion of the R.A. shaft.

4. Tighten the motor coupler screw with a flathead screwdriver.

5. Rotate the motor on the shaft until the slotted cutout on the motor bracket aligns with the threaded hole in the

center of the mount’s latitude pivot axis.

6. Place the Allen head bolt through the motor bracket and thread it into the hole on the side of the pivot axis.

Then, tighten the bolt with an Allen wrench.

Flexible Motor Coupler

Mounting

Screws

Figure 4-11 Figure 4-12

Operating the Motor Drive

Motor Bracket

Allen Head Bolt

The motor drive is powered by one 9-volt alkaline battery. This can power the drive for up to 40 hours, depending

on motor speed setting and ambient temperature. The battery should be installed already but if not (or replacing the

battery), unscrew the two mounting screws – Figure 4-11. Remove the control panel plate from the motor assembly

and then remove the motor bracket from the motor. Then, you will be able to get to the battery connected to cables

for installing or replacing. Finally, reverse all steps to remount the motor drive to the mount.

The motor drive is equipped with a speed rate regulator (in Figure 4-11 it is above the mounting screw) that allows

the motor drive to track at a faster or slower speed. This is useful when observing non-stellar objects like the moon

or Sun which travel at a slightly different rate than the stars. To change the speed of the motor, slide the On/Off

switch to the “ON” position and the red power indicator light will illuminate. Then, turn the speed rate regulator

knob clockwise to increase the speed of the motor and counterclockwise to decrease the speed.

To determine the proper rate of speed, the telescope should be roughly polar aligned. Find a star on the celestial

equator (approximately 0° declination) and center it in a low power eyepiece. Now turn the drive on and let the

telescope track for 1 or 2 minutes. If after a few minutes, the star drifts to the West, the motor is tracking too slowly

and you should increase the motor speed. If the star is drifting to the East, then decrease the motor speed. Repeat

this process until the star remains centered in the eyepiece for several minutes. Remember to ignore any star drift in

declination.

The drive also has a “N/S” switch to be set if operating in the Northern or Southern Hemisphere.

22

Page 23

With your telescope set up, you are ready to use it for observing. This section covers visual observing hints for both

solar system and deep sky objects as well as general observing conditions which will affect your ability to observe.

OObbsseerrvviinngg tthhee MMoooonn

Lunar Observing Hints

To increase contrast and bring out detail on the lunar surface, use optional filters. A yellow filter works well at

improving contrast while a neutral density or polarizing filter will reduce overall surface brightness and glare.

OObbsseerrvviinngg tthhee PPllaanneettss

Other fascinating targets include the five naked eye planets. You can see Venus

go through its lunar-like phases. Mars can reveal a host of surface detail and

one, if not both, of its polar caps. You will be able to see the cloud belts of

Jupiter and the great Red Spot (if it is visible at the time you are observing). In

addition, you will also be able to see the moons of Jupiter as they orbit the giant

planet. Saturn, with its beautiful rings, is easily visible at moderate power

Often, it is tempting to look at the Moon when it is full. At this time, the

face we see is fully illuminated and its light can be overpowering. In

addition, little or no contrast can be seen during this phase.

One of the best times to observe the Moon is during its partial phases

(around the time of first or third quarter). Long shadows reveal a great

amount of detail on the lunar surface. At low power you will be able to

see most of the lunar disk at one time. Change to optional eyepieces for

higher power (magnification) to focus in on a smaller area.

.

Planetary Observing Hints

y Remember that atmospheric conditions are usually the limiting factor

on how much planetary detail will be visible. So, avoid observing the

planets when they are low on the horizon or when they are directly over a source of radiating heat, such as

a rooftop or chimney. See the "Seeing Conditions" section later in this section.

y To increase contrast and bring out detail on the planetary surface, try using Celestron eyepiece filters.

OObbsseerrvviinngg tthhee SSuunn

Although overlooked by many amateur astronomers, solar observation is both rewarding and fun. However,

because the Sun is so bright, special precautions must be taken when observing our star so as not to damage your

eyes or your telescope.

For safe solar viewing, use a proper solar filter that reduces the intensity of the Sun's light, making it safe to view.

With a filter you can see sunspots as they move across the solar disk and faculae, which are bright patches seen near

the Sun's edge.

y The best time to observe the Sun is in the early morning or late afternoon when the air is cooler.

y To center the Sun without looking into the eyepiece, watch the shadow of the telescope tube until it forms a

circular shadow.

23

Page 24

s

OObbsseerrvviinngg DDeeeepp--SSkkyy OObbjjeecctts

Deep-sky objects are simply those objects outside the boundaries of our solar system. They include star clusters,

planetary nebulae, diffuse nebulae, double stars and other galaxies outside our own Milky Way. Most deep-sky

objects have a large angular size. Therefore, low-to-moderate power is all you need to see them. Visually, they are

too faint to reveal any of the color seen in long exposure photographs. Instead, they appear black and white. And,

because of their low surface brightness, they should be observed from a dark-sky location. Light pollution around

large urban areas washes out most nebulae making them difficult, if not impossible, to observe. Light Pollution

Reduction filters help reduce the background sky brightness, thus increasing contrast.

SSeeeeiinngg CCoonnddiittiioonnss

Viewing conditions affect what you can see through your telescope during an observing session. Conditions include

transparency, sky illumination, and seeing. Understanding viewing conditions and the effect they have on observing

will help you get the most out of your telescope.

Transparency

Transparency is the clarity of the atmosphere which is affected by clouds, moisture, and other airborne particles.

Thick cumulus clouds are completely opaque while cirrus can be thin, allowing the light from the brightest stars

through. Hazy skies absorb more light than clear skies making fainter objects harder to see and reducing contrast on

brighter objects. Aerosols ejected into the upper atmosphere from volcanic eruptions also affect transparency. Ideal

conditions are when the night sky is inky black.

Sky Illumination

General sky brightening caused by the Moon, aurora, natural airglow, and light pollution greatly affect transparency.

While not a problem for the brighter stars and planets, bright skies reduce the contrast of extended nebulae making

them difficult, if not impossible to see. To maximize your observing, limit deep sky viewing to moonless nights far

from the light polluted skies found around major urban areas. LPR filters enhance deep sky viewing from light

polluted areas by blocking unwanted light while transmitting light from certain deep sky objects. You can, on the

other hand, observe planets and stars from light polluted areas or when the Moon is out.

Seeing

Seeing conditions refers to the stability of the atmosphere and directly affects the amount of fine detail seen in

extended objects. The air in our atmosphere acts as a lens which bends and distorts incoming light rays. The

amount of bending depends on air density. Varying temperature layers have different densities and, therefore, bend

light differently. Light rays from the same object arrive slightly displaced creating an imperfect or smeared image.

These atmospheric disturbances vary from time-to-time and place-to-place. The size of the air parcels compared to

your aperture determines the "seeing" quality. Under good seeing conditions, fine detail is visible on the brighter

planets like Jupiter and Mars, and stars are pinpoint images. Under poor seeing conditions, images are blurred and

stars appear as blobs.

The conditions described here apply to both visual and photographic observations.

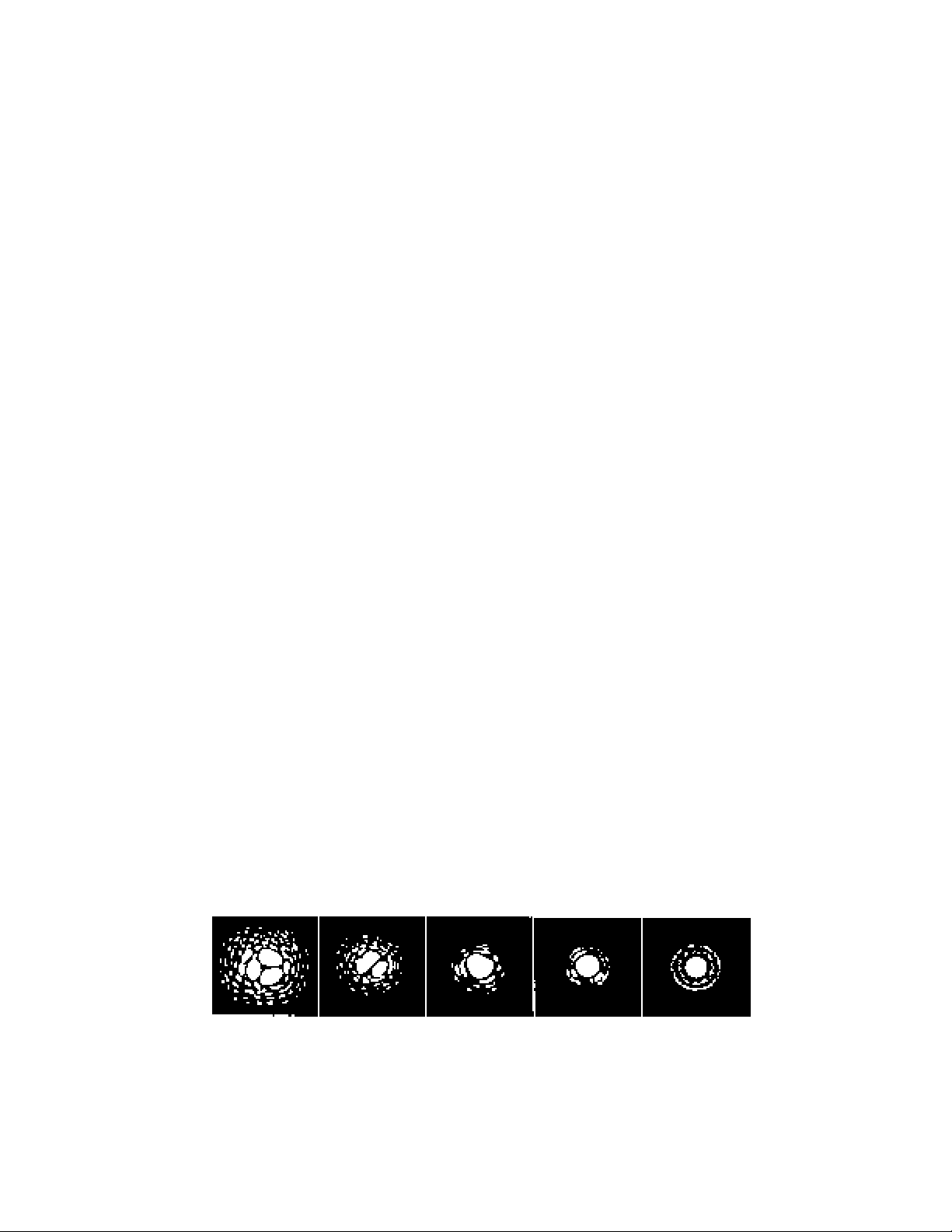

Figure 5-1

Seeing conditions directly affect image quality. These drawings represent a point

source (i.e., star) under bad seeing conditions (left) to excellent conditions (right).

Most often, seeing conditions produce images that lie somewhere between these two

extremes.

24

Page 25

The PowerSeeker series of telescopes was designed for visual observing. After looking at the night sky for a while

you may want to try your hand at photography of it. There are several forms of photography possible with your

telescope for celestial as well as terrestrial pursuits. Below is just a very brief discussion of some of the methods of

photography available and suggest you search out various books for detailed information on the subject matter.

As a minimum you will need a digital camera or a 35mm SLR camera. Attach your camera to the telescope with:

y Digital camera – you will need the Universal Digital Camera Adapter (# 93626). The adapter allows the

camera to be mounted rigidly for terrestrial as well as prime focus astrophotography.

y 35mm SLR camera – you will need to remove your lens from the camera and attach a T-Ring for your

specific camera brand. Then, you will need a T-Adapter (# 93625) to attach on one end to the T-Ring and

the other end to the telescope focus tube. Your telescope is now the camera lens.

SShhoorrtt EExxppoossuurree PPrriimmee FFooccuuss PPhhoottooggrraapphhyy

Short exposure prime focus photography is the best way to begin imaging celestial objects. It is done by attaching

your camera to the telescope as described in the paragraph above. A couple of points to keep in mind:

y Polar align the telescope and start the optional motor drive for tracking.

y You can image the Moon as well as the brighter planets. You will have to experiment with various settings

and exposure times. Much information can be obtained from your camera instruction manual which can

supplement what you can find in detailed books on the subject matter.

y Do your photography from a dark sky observing site if possible.

PPiiggggyybbaacckk PPhhoottooggrraapphhyy

For the 70EQ, 80EQ, 114EQ, and 127EQ telescopes, piggyback

photography is done with a camera and its normal lens riding on top of the

telescope. Through this method you can capture entire constellations and

record large scale nebulae. You attach your camera to the piggyback

adapter screw (Figure 6-1) located on the top of the tube mounting ring

(your camera will have a threaded hole on the bottom to fit this screw).

You will need to polar align the telescope and start the optional motor

drive for tracking

Figure 6-1

.

PPllaanneettaarryy && LLuunnaarr PPhhoottooggrraapphhyy wwiitthh SSppeecciiaall IImmaaggeerrss

During the last few years a new technology has evolved which makes taking superb images of the planets and moon

relatively easy and the results are truly amazing. Celestron offers the NexImage (# 93712) which is a special camera

and included is software for image processing. You can capture planetary images your first night out which rivals

what professionals were doing with large telescopes just a few short years ago.

CCCCDD IImmaaggiinngg ffoorr DDeeeepp SSkkyy OObbjjeeccttss

Special cameras have been developed for taking images of deep sky images. These have evolved over the last

several years to become much more economical and amateurs can take fantastic images. Several books have been

written on how to get the best images possible. The technology continues to evolve with better and easier to use

products on the market.

TTeerrrreessttrriiaall PPhhoottooggrraapphhyy

Your telescope makes an excellent telephoto lens for terrestrial (land) photography. You can take images of various

scenic views, wildlife, nature, and just about anything. You will have to experiment with focusing, speeds, etc. to

get the best image desired. You can adapt your camera per the instructions at the top of this page.

25

Page 26

While your telescope requires little maintenance, there are a few things to remember that will ensure your telescope

performs at its best.

CCaarree aanndd CClleeaanniinngg ooff tthhee OOppttiiccss

Occasionally, dust and/or moisture may build up on the objective lens or primary mirror depending on which type of

telescope you have. Special care should be taken when cleaning any instrument so as not to damage the optics.

If dust has built up on the optics, remove it with a brush (made of camel’s hair) or a can of pressurized air. Spray at an

angle to the glass surface for approximately two to four seconds. Then, use an optical cleaning solution and white tissue

paper to remove any remaining debris. Apply the solution to the tissue and then apply the tissue paper to the optics.

Low pressure strokes should go from the center of the lens (or mirror) to the outer portion. Do NOT rub in circles!

You can use a commercially made lens cleaner or mix your own. A good cleaning solution is isopropyl alcohol mixed

with distilled water. The solution should be 60% isopropyl alcohol and 40% distilled water. Or, liquid dish soap diluted

with water (a couple of drops per one quart of water) can be used.

Occasionally, you may experience dew build-up on the optics of your telescope during an observing session. If you want

to continue observing, the dew must be removed, either with a hair dryer (on low setting) or by pointing the telescope at

the ground until the dew has evaporated.

If moisture condenses on the inside of the optics, remove the accessories from the telescope. Place the telescope in a

dust-free environment and point it down. This will remove the moisture from the telescope tube.

To minimize the need to clean your telescope, replace all lens covers once you have finished using it. Since the cells are

NOT sealed, the covers should be placed over the openings when not in use. This will prevent contaminants from

entering the optical tube.

Internal adjustments and cleaning should be done only by the Celestron repair department. If your telescope is in need of

internal cleaning, please call the factory for a return authorization number and price quote.

CCoolllliimmaattiioonn ooff aa NNeewwttoonniiaann

The optical performance of most Newtonian reflecting telescopes can be optimized by re-collimating (aligning) the

telescope's optics, as needed. To collimate the telescope simply means to bring its optical elements into balance. Poor

collimation will result in optical aberrations and distortions.

Before collimating your telescope, take time to familiarize yourself with all its components. The primary mirror is the

large mirror at the back end of the telescope tube. This mirror is adjusted by loosening and tightening the three screws,

placed 120 degrees apart, at the end of the telescope tube. The secondary mirror (the small, elliptical mirror under the

focuser, in the front of the tube) also has three adjustment screws (you will need optional tools (described below) to

perform collimation. To determine if your telescope needs collimation first point your telescope toward a bright wall or

blue sky outside.

Aligning the Secondary Mirror

The following describes the procedure for daytime collimation of your telescope using the optional Newtonian

Collimation Tool (#94183) offered by Celestron. To collimate the telescope without the Collimation Tool, read the

following section on night time star collimation. For very precise collimation, the optional Collimation Eyepiece 1 ¼” (#

94182) is offered.

If you have an eyepiece in the focuser, remove it. Rack the focuser tube in completely, using the focusing knobs, until

its silver tube is no longer visible. You will be looking through the focuser at a reflection of the secondary mirror,

projected from the primary mirror. During this step, ignore the silhouetted reflection from the primary mirror. Insert the

collimating cap into the focuser and look through it. With the focus pulled in all the way, you should be able to see the

entire primary mirror reflected in the secondary mirror. If the primary mirror is not centered in the secondary mirror,

adjust the secondary mirror screws by alternately tightening and loosening them until the periphery of the primary mirror

is centered in your view. DO NOT loosen or tighten the center screw in the secondary mirror support, because it

maintains proper mirror position.

26

Page 27

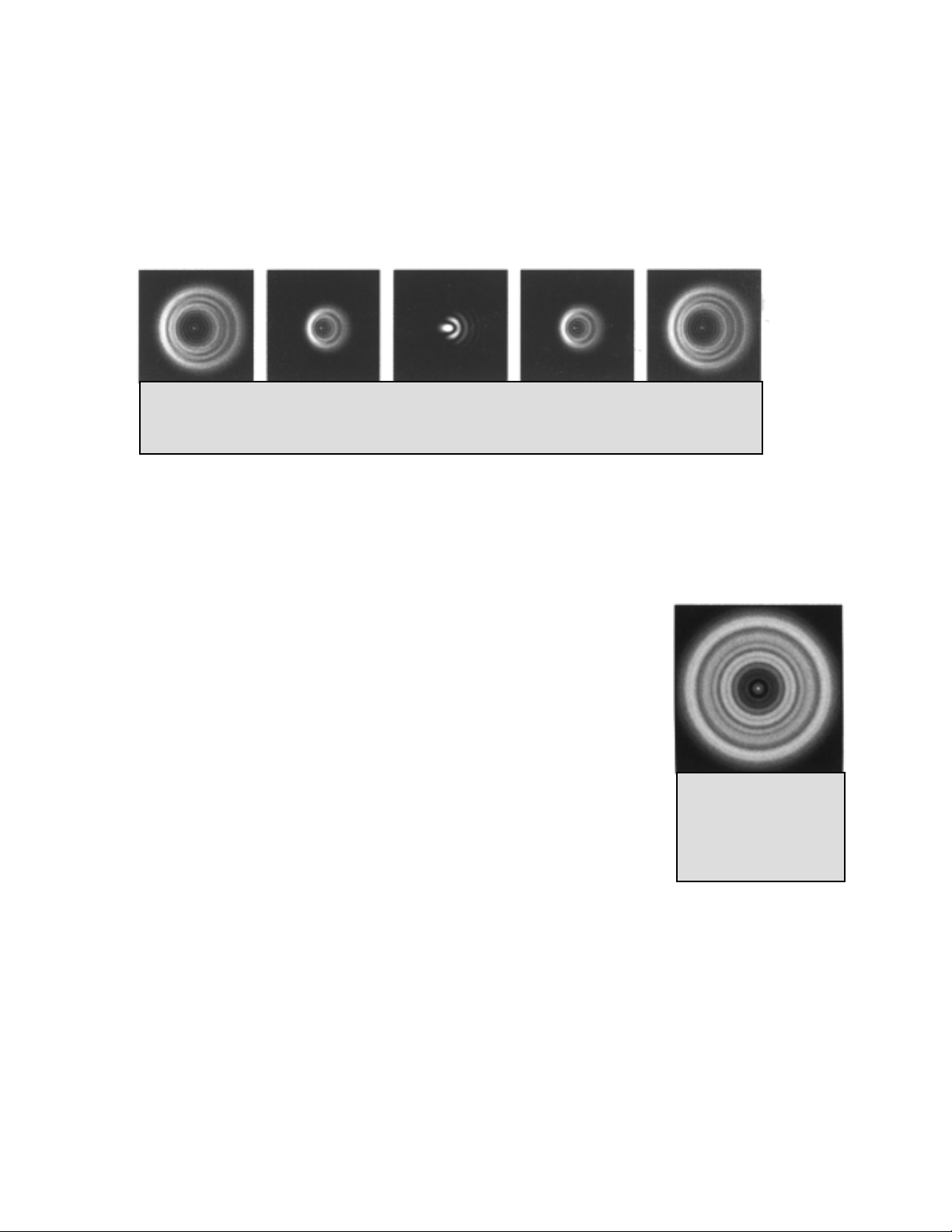

Aligning the Primary Mirror

Now adjust the primary mirror screws to re-center the reflection of the small secondary mirror, so it’s silhouetted

against the view of the primary. As you look into the focuser, silhouettes of the mirrors should look concentric.

Repeat steps one and two until you have achieved this.

Remove the collimating cap and look into the focuser, where you should see the reflection of your eye in the

secondary mirror.

Newtonian collimation views as seen through the focuser using the collimation cap

Secondary mirror needs adjustment.

Secondary

Mirror

Primary mirror needs adjustment.

Primary

Mirror

Mirror Clip

Both mirrors aligned with the collimating

cap in the focuser.