Beginners Introduction to the

Assembly Language of

ATMEL-AVR-Microprocessors

by

Gerhard Schmidt

http://www.avr-asm-tutorial.net

October 2004

Avr-Asm-Tutorial 1 http://www.avr-asm-tutorial.net

Content

Why learning Assembler?..........................................................................................................................1

Short and easy.......................................................................................................................................1

Fast and quick........................................................................................................................................1

Assembler is easy to learn.....................................................................................................................1

AT90Sxxxx are ideal for learning assembler........................................................................................1

Test it!....................................................................................................................................................1

Hardware for AVR-Assembler-Programming...........................................................................................2

The ISP-Interface of the AVR-processor family...................................................................................2

Programmer for the PC-Parallel-Port....................................................................................................2

Experimental board with a AT90S2313................................................................................................3

Ready-to-use commercial programming boards for the AVR-family...................................................4

Tools for AVR assembly programing........................................................................................................5

The editor..............................................................................................................................................5

The assembler........................................................................................................................................6

Programming the chips..........................................................................................................................7

Simulation in the studio.........................................................................................................................7

Register......................................................................................................................................................9

What is a register?.................................................................................................................................9

Different registers................................................................................................................................10

Pointer-register....................................................................................................................................10

Recommendation for the use of registers............................................................................................11

Ports.........................................................................................................................................................12

What is a Port?....................................................................................................................................12

Details of relevant ports in the AVR...................................................................................................13

The status register as the most used port.............................................................................................13

Port details...........................................................................................................................................14

SRAM..................................................................................................................................................15

Using SRAM in AVR assembler language.........................................................................................15

What is SRAM?...................................................................................................................................15

For what purposes can I use SRAM?..................................................................................................15

How to use SRAM?.............................................................................................................................15

Use of SRAM as stack.........................................................................................................................16

Defining SRAM as stack................................................................................................................16

Use of the stack...............................................................................................................................17

Bugs with the stack operation.........................................................................................................17

Jumping and Branching............................................................................................................................19

Controlling sequential execution of the program................................................................................19

What happens during a reset?.........................................................................................................19

Linear program execution and branches..............................................................................................20

Timing during program execution.......................................................................................................20

Macros and program execution...........................................................................................................21

Subroutines..........................................................................................................................................21

Interrupts and program execution........................................................................................................23

Calculations..............................................................................................................................................25

Number systems in assembler.............................................................................................................25

Positive whole numbers (bytes, words, etc.)..................................................................................25

Signed numbers (integers)..............................................................................................................25

Binary Coded Digits, BCD.............................................................................................................25

Packed BCDs..................................................................................................................................26

Numbers in ASCII-format..............................................................................................................26

Bit manipulations................................................................................................................................26

Shift and rotate....................................................................................................................................27

Adding, subtracting and comparing....................................................................................................28

Format conversion for numbers...........................................................................................................29

Multiplication......................................................................................................................................30

Decimal multiplication...................................................................................................................30

Binary multiplication......................................................................................................................30

Avr-Asm-Tutorial 2 http://www.avr-asm-tutorial.net

AVR-Assembler program...............................................................................................................31

Binary rotation................................................................................................................................32

Multiplication in the studio.............................................................................................................32

Division...............................................................................................................................................34

Decimal division.............................................................................................................................34

Binary division...............................................................................................................................34

Program steps during division........................................................................................................35

Division in the simulator................................................................................................................35

Number conversion.............................................................................................................................37

Decimal Fractions................................................................................................................................37

Linear conversions..........................................................................................................................37

Example 1: 8-bit-AD-converter with fixed decimal output............................................................38

Example 2: 10-bit-AD-converter with fixed decimal output..........................................................40

Annex.......................................................................................................................................................41

Commands sorted by function.............................................................................................................41

Command list in alphabetic order.......................................................................................................43

Assembler directives.......................................................................................................................43

Commands......................................................................................................................................43

Port details...........................................................................................................................................45

Status-Register, Accumulator flags................................................................................................45

Stackpointer....................................................................................................................................45

SRAM and External Interrupt control............................................................................................45

External Interrupt Control...............................................................................................................46

Timer Interrupt Control..................................................................................................................46

Timer/Counter 0..............................................................................................................................47

Timer/Counter 1..............................................................................................................................48

Watchdog-Timer.............................................................................................................................49

EEPROM........................................................................................................................................49

Serial Peripheral Interface SPI........................................................................................................50

UART.............................................................................................................................................51

Analog Comparator........................................................................................................................51

I/O Ports..........................................................................................................................................52

Ports, alphabetic order.........................................................................................................................52

List of abbreviations............................................................................................................................53

Errors in previous versions..................................................................................................................54

Avr-Asm-Tutorial 1 http://www.avr-asm-tutorial.net

Why learning Assembler?

Assembler or other languages, that is the question. Why should I learn another language, if I already

learned other programming languages? The best argument: while you live in France you are able to get

through by speaking english, but you will never feel at home then, and life remains complicated. You can

get through with this, but it is rather inappropriate. If things need a hurry, you should use the country's

language.

Short and easy

Assembler commands translate one by one to executed machine commands. The processor needs only to

execute what you want it to do and what is necessary to perform the task. No extra loops and unnecessary

features blow up the generated code. If your program storage is short and limited and you have to optimize

your program to fit into memory, assembler is choice 1. Shorter programs are easier to debug, every step

makes sense.

Fast and quick

Because only necessary code steps are executed, assembly programs are as fast as possible. The

duration of every step is known. Time critical applications, like time measurements without a hardware

timer, that should perform excellent, must be written in assembler. If you have more time and don't mind if

your chip remains 99% in a wait state type of operation, you can choose any language you want.

Assembler is easy to learn

It is not true that assmbly language is more complicated or not as easy to understand than other

languages. Learning assembly language for whatever hardware type brings you to understand the basic

concepts of any other assembly language dialect. Adding other dialects later is easy. The first assembly

code does not look very attractive, with every 100 additional lines programmed it looks better. Perfect

programs require some thousand lines of code of exercise, and optimization requires lots of work. As

some features are hardware-dependant optimal code requires some familiarity with the hardware concept

and the dialect. The first steps are hard in any language. After some weeks of programming you will laugh

if you go through your first code. Some assembler commands need some monthes of experience.

AT90Sxxxx are ideal for learning assembler

Assembler programs are a little bit silly: the chip executes anything you tell it to do, and does not ask you if

you are sure overwriting this and that. All protections must be programmed by you, the chip does anything

like it is told. No window warns you, unless you programmed it before.

Basic design errors are as complicated to debug like in any other computer language. But: testing

programs on ATMEL chips is very easy. If it does not do what you expect it to do, you can easily add some

diagnostic lines to the code, reprogram the chip and test it. Bye, bye to you EPROM programmers, to the

UV lamps used to erase your test program, to you pins that don't fit into the socket after having them

removed some douzend times.

Changes are now programmed fast, compiled in no time, and either simulated in the studio or checked incircuit. No pin is removed, and no UV lamp gives up just in the moment when you had your excellent idea

about that bug.

Test it!

Be patient doing your first steps! If you are familiar with another (high-level) language: forget it for the first

time. Behind every assembler language there is a certain hardware concept. Most of the special features

of other computer languages don't make any sense in assembler.

The first five commands are not easy to learn, then your learning speed rises fast. After you had your first

lines: grab the instruction set list and lay back in the bathtub, wondering what all the other commands are

like.

Don't try to program a mega-machine to start with. This does not make sense in any computer language,

and just produces frustration.

Comment your subroutines and store them in a special directory, if debugged: you will need them again in

a short time.

Have success!

Avr-Asm-Tutorial 2 http://www.avr-asm-tutorial.net

Hardware for AVR-Assembler-Programming

Learning assembler requires some simple hardware equipment to test your programs, and see if it works

in practice.

This section shows two easy schematics that enable you to homebrew the required hardware and gives

you the necessary hints on the required background. This hardware really is easy to build. I know nothing

easier than that to test your first software steps. If you like to make more experiments, leave some more

space for future extensions on your experimental board.

If you don't like the smell of soldering, you can buy a ready-to-use board, too. The available boards are

characterised in this section below.

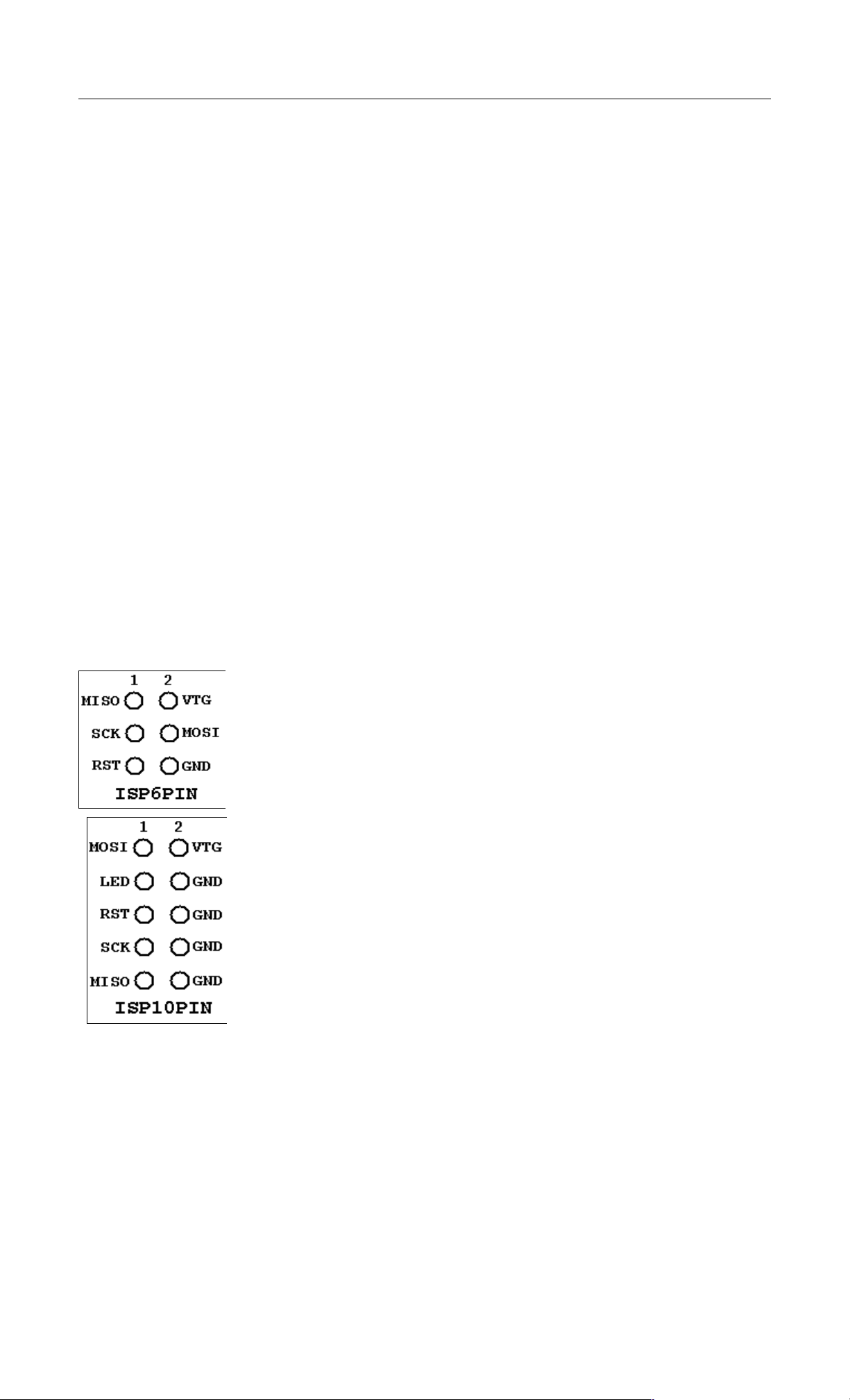

The ISP-Interface of the AVR-processor family

Before going into practice, we have to learn a few essentials on the serial programming mode of the AVR

family. No, you don't need three different voltages to program and read an AVR flash memory. No, you

don't need another microprocessor to program the AVRs. No, you don't need 10 I/O lines to tell the chip

what you like it to do. And you don't even have to remove the AVR from your experimental board, before

programming it. It's even easier than that.

All this is done by a build-in interface in the AVR chip, that enables you to write and read the content of the

program flash and the built-in-EEPROM. This interface works serially and needs three signal lines:

• SCK: A clock signal that shifts the bits to be written to the memory into an internal shift register, and

that shifts out the bits to be read from another internal shift register,

• MOSI: The data signal that sends the bits to be written to the AVR,

• MISO: The data signal that receives the bits read from the AVR.

These three signal pins are internally connected to the programming machine only if you change the

RESET (sometimes also called RST or restart) pin to zero. Otherwise, during normal operation of the AVR,

these pins are programmable I/O lines like all the others.

If you like to use these pins for other purposes during normal operation, and for insystem-programming, you'll have to take care, that these two purposes do not

conflict. Usually you then decouple these by resistors or by use of a multiplexer.

What is necessary in your case, depends from your use of the pins in the normal

operation mode. You're lucky, if you can use them for in- system-programming

exclusively.

Not necessary, but recommendable for in-system-programming is, that you supply

the programming hardware out of the supply voltage of your system. That makes it

easy, and requires two additional lines between the programmer and the AVR

board. GND is the common ground, VTG (target voltage) the supply voltage

(usually 5.0 volts). This adds up to 6 lines between the programmer and the AVR

board. The resulting ISP6 connection is, as defined by AMEL, is shown on the left.

Standards always have alternative standards, that were used earlier. This is the

technical basis that constitutes the adaptor industry. In our case the alternative

standard was designed as ISP10 and was used on the STK200 board. It's still a

very widespread standard, and even the STK500 is still equipped with it. ISP10

has an additional signal to drive a red LED. This LED signals that the programmer

is doing his job. A good idea. Just connect the LED to a resistor and clamp it the

positive supply voltage.

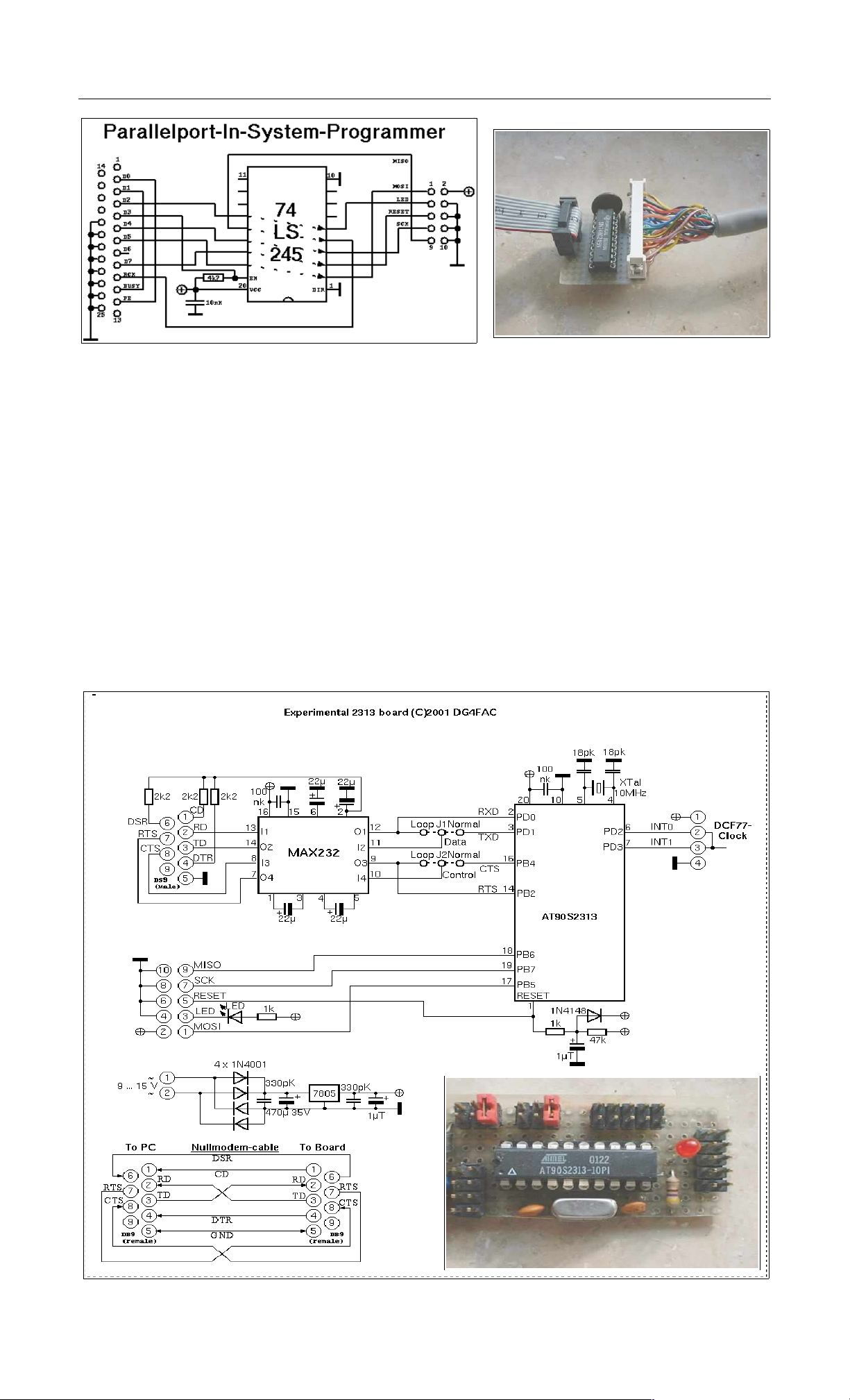

Programmer for the PC-Parallel-Port

Now, heat up your soldering iron and build up your programmer. It is a quite easy schematic and works

with standard parts from your well-sorted experiments box.

Yes, that's all you need to program an AVR. The 25-pin plug goes into the parallel port of your PC, the 10pin-ISP goes to your AVR experimental board. If your box doesn't have a 74LS245, you can also use a

74HC245 or a 74LS244/74HC244 (by changing some pins and signals). If you use HC, don't forget to tie

unused inputs either to GND or the supply voltage, otherwise the buffers might produce extra noise by

capacitive switching.

Avr-Asm-Tutorial 3 http://www.avr-asm-tutorial.net

The necessary program algorithm is done by the ISP software, that is available from ATMEL's software

download page.

Experimental board with a AT90S2313

For test purposes we use a AT90S2313 on an experimental board. The schematic shows

• a small voltage supply for connection to an AC transformer and a voltage regulator 5V/1A,

• a XTAL clock generator (here with a 10 Mcs/s, all other frequencies below the maximum for the 2313

will also work),

• the necessary parts for a safe reset during supply voltage switching,

• the ISP-Programming-Interface (here with a ISP10PIN-connector).

So that's what you need to start with. Connect other peripheral add-ons to the numerous free I/O pins of

the 2313.

The easiest output device can be a LED, connected via a resistor to the positive supply voltage. With that,

you can start writing your first assembler program switching the LED on and off.

Avr-Asm-Tutorial 4 http://www.avr-asm-tutorial.net

Ready-to-use commercial programming boards for the

AVR-family

If you do not like homebrewed hardware, and if have some extra money left that you don't know what to do

with, you can buy a commercial programming board. Easy to get is the STK500 (e.g. from ATMEL. It has

the following hardware:

• Sockets for programming most of the AVR types,

• serial und parallel programming,

• ISP6PIN- and ISP10PIN-connector for external In-System-Programming,

• programmable oscillator frequency and suplly voltages,

• plug-in switches and LEDs,

• a plugged RS232C-connector (UART),

• a serial Flash-EEPROM,

• access to all ports via a 10-pin connector.

Experiments can start with the also supplied AT90S8515. The board is connected to the PC using a serial

port (COMx) and is controlled by later versions of AVR studio, available from ATMEL's webpage. This

covers all hardware requirements that the beginner might have.

Avr-Asm-Tutorial 5 http://www.avr-asm-tutorial.net

Tools for AVR assembly programing

This section provides informations about the necessary tools that are used to program AVRs with the

STK200 board. Programming with the STK500 is very different and shown in more detail in the Studio

section. Note that the older software for the STK200 is not supported any more.

Four basic programs are necessary for assembly programming. These tools are:

• the editor,

• the assembler program,

• the chip programing interface, and

• the simulator.

The necessary software tools are ©ATMEL and available on the webpage of ATMEL for download. The

screenshots here are ©ATMEL. It should be mentioned that there are different versions of the software

and some of the screenshots are subject to change with the used version. Some windows or menues look

different in different versions. The basic functions are mainly unchanged. Refer to the programer's

handbook, this page just provides an overview for the beginner's first steps and is not written for the

assembly programing expert.

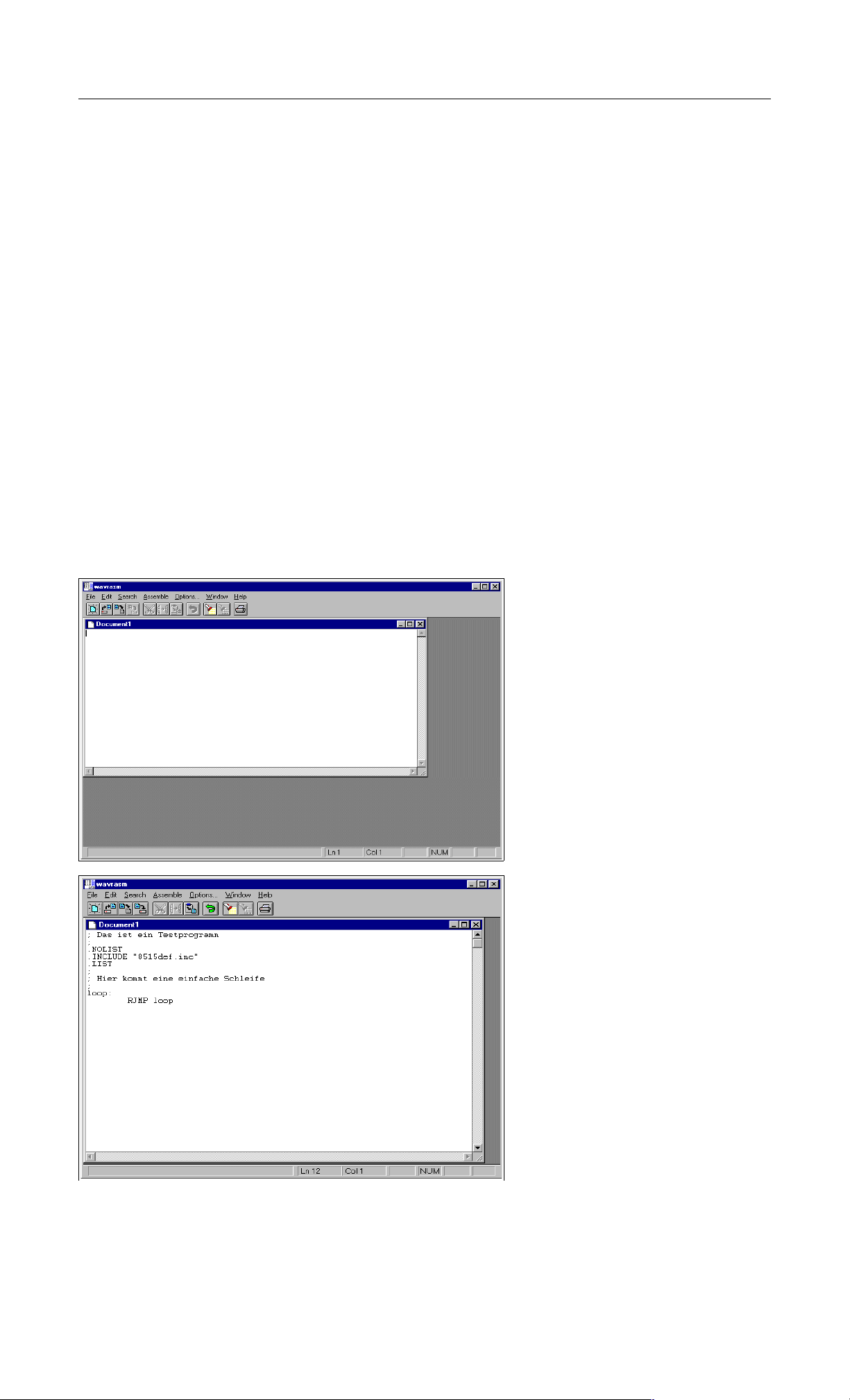

The editor

Assembler programs are written with a editor. The editor just has to be able to create and edit ASCII text

files. So, basically, any simple editor does it. I recommend the use of a more advanced editor, either

WAVRASM©ATMEL or the editor written by Tan Silliksaar (screenshot see below).

An assembly program written with

WAVRASM© goes like this. Just install

WAVRASM© and start the program:

Now we type in our directives and

assembly commands in the WAVRASM

editor window, together with some

comments (starting with ;). That should

look like this:

Now store the program text, named to something.asm into a dedicated directory, using the file menue. The

assembly program is complete now.

If you like editing a little more in a sophisticated manner you can use the excellent editor written by Tan

Silliksaar. This editor tools is designed for AVRs and available for free from Tan's webpage. In this editor

our program looks like this:

Avr-Asm-Tutorial 6 http://www.avr-asm-tutorial.net

The editor recognizes commands automatically and uses

different colors (syntax highlighting) to signal user constants

and typing errors in those

commands (in black). Storing

the code in an .asm file provides

nearly the same text file.

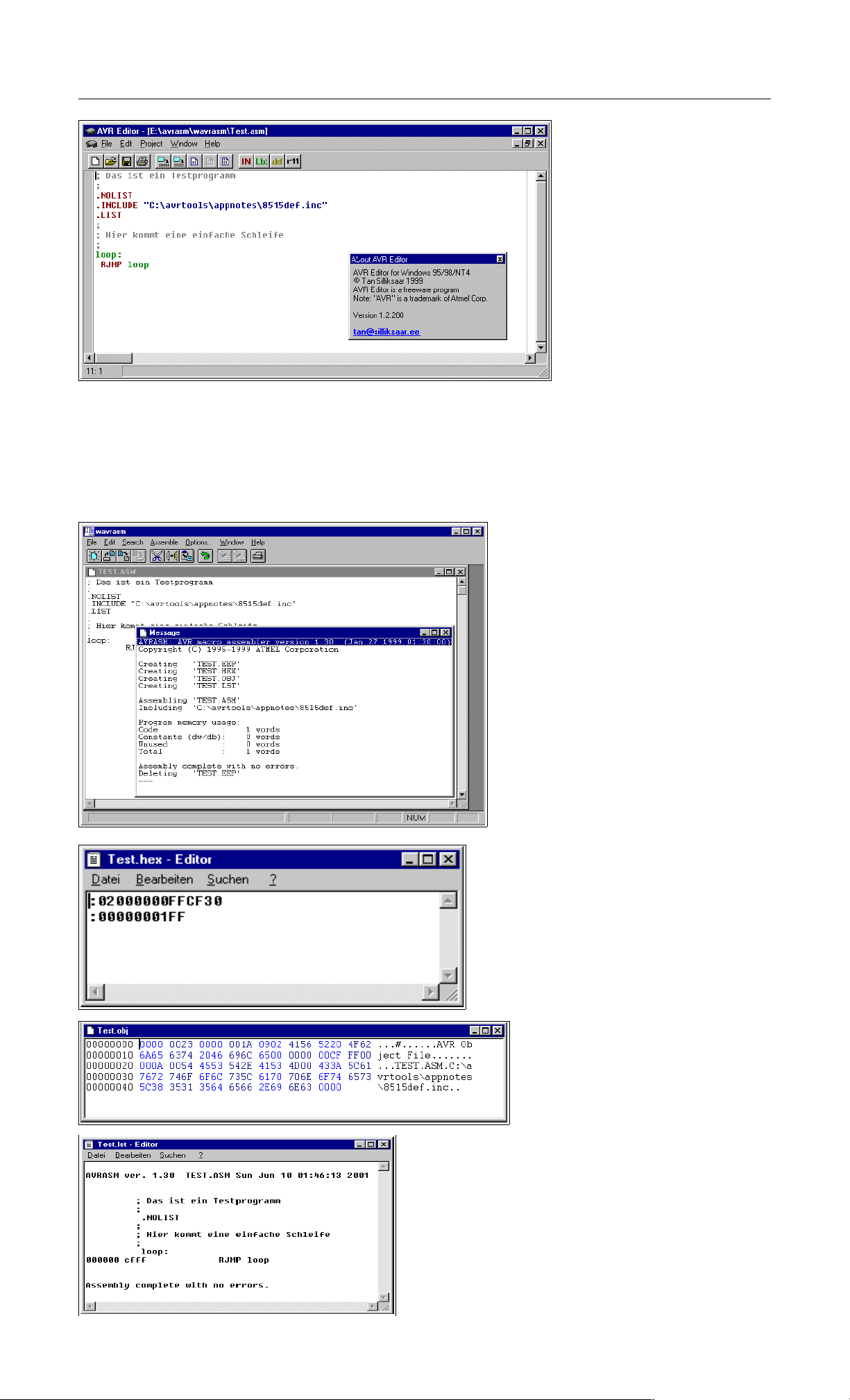

The assembler

Now we have to translate this code to a machine-oriented form well understood by the AVR chip. Doing

this is called assembling, which means collecting the right command words. If you use WAVRASM© just

click assemble on the menue. The result is shown here:

The assembler reports the complete

translation with no errors. If errors occur

these are notified. Assembling resulted in

one word of code which resulted from the

command we used. Assembling our single

asm-text file now has produced four other

files (not all apply here).

The first of these four new files,

TEST.EEP, holds the content that should

be written to the EEPROM of the AVR.

This is not very interesting in our case,

because we didn't program any content

for the EEPROM. The assembler has

therefore deleted this file when he

completed the assembly run.

The second file, TEST.HEX, is more relevant

because this file holds the commands later

programmed into the AVR chip. This file

looks like this.

The hex numbers are written in a special

ASCII form, together with adress informations

and a checksum for each line. This form is

called Intel-hex-format, and it is very old. The

form is well understood by the programing

software.

The third file, TEST.OBJ, will be

introduced later, this file is needed to

simulate an AVR. Its format is

hexadecimal and defined by ATMEL.

Using a hex-editor its content looks

like this. Attention: This file format is

not compatible with the programer software, don't use

this file to program the AVR (a very common error when

starting).

The fourth file, TEST.LST, is a text file. Display its

content with a simple editor. The following results.

The program with all its adresses, comands and error

messages are displayed in a readable form. You will

need that file in some cases to debug errors.

Avr-Asm-Tutorial 7 http://www.avr-asm-tutorial.net

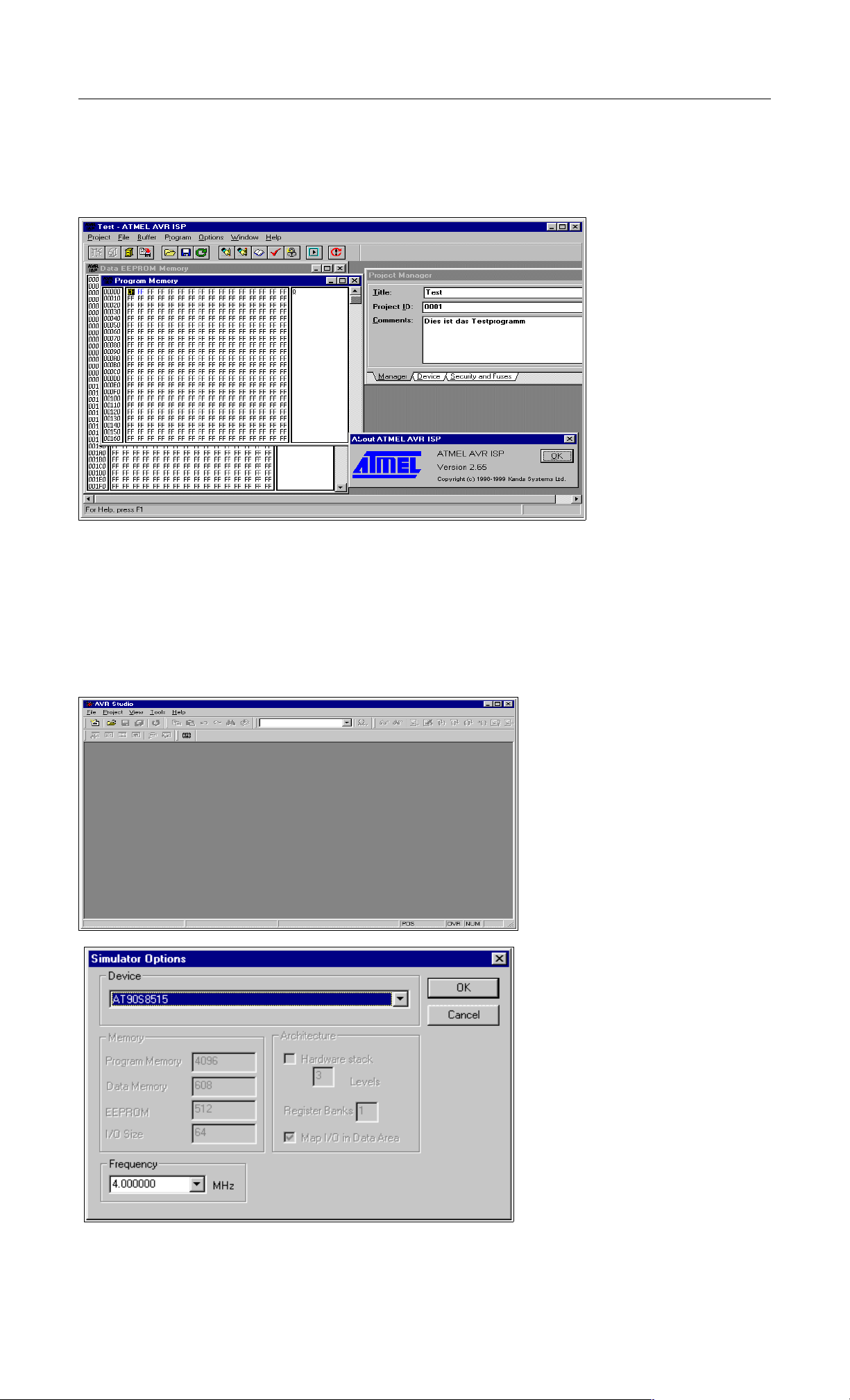

Programming the chips

To program our hex code to the AVR ATMEL has written the ISP software package. (Not that this software

is not supported and distributed any more.) We start the ISP software and load the hex file that we just

generated (applying menue item LOAD PROGRAM). That looks like this:

Applying menue item

PROGRAM will burn our

code in the chip's program

store. There are a number

of preconditions necessary

for this step (the correct

parallel port has to be

selected, the programming

adapter must be

connected, the chip must

be on board the adapter,

the power supply must be

on, etc.).

Besides the ATMEL-ISP

and the programming

boards other programming

boards or adapters could

be used, together with the

appropriate programming software. Some of these alternatives are available on the internet.

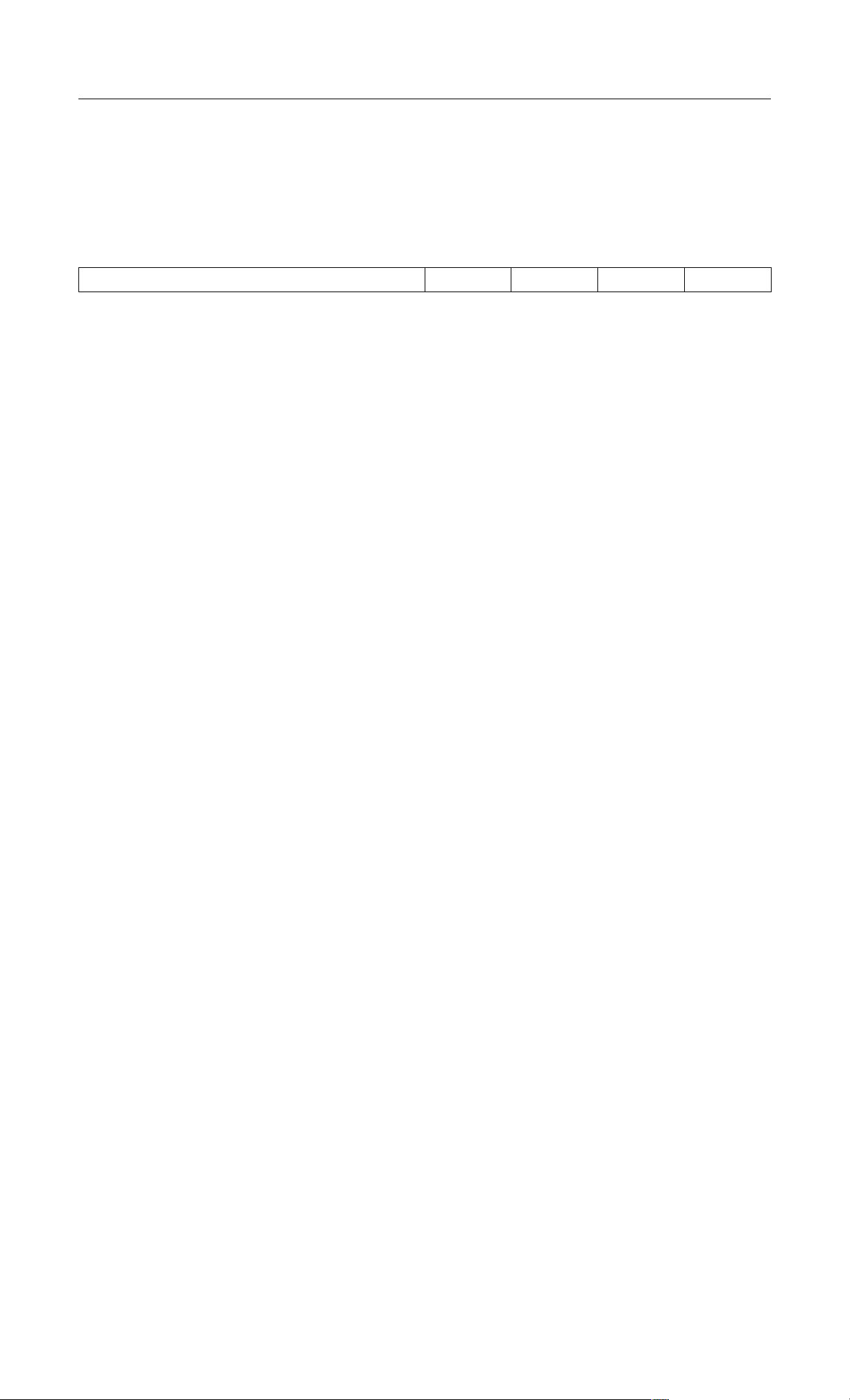

Simulation in the studio

In some cases self-written assembly code, even assembled without errors, does not exactly do what it

should do when burned into the chip. Testing the software on the chip could be complicated, esp. if you

have a minimum hardware and no opportunity to display interim results or debugging signals. In these

cases the studio from ATMEL provides ideal opportunities for debugging. Testing the software or parts of it

is possible, the program could be tested step-by-step displaying results.

The studio is started and looks like

this.

First we open a file (menue item FILE

OPEN). We demonstrate this using

the tutorial file test1.asm, because

there are some more commands and

action that in our single-command

program above.

Open the file TEST1.OBJ that results

by assembling TEST1.asm. You are

asked which options you like to use (if

not, you can change these using the

menue item SIMULATOR OPTIONS).

The following options will be selected:

In the device selection section we

select the desired chip type. The

correct frequency should be selected

if you like to simulate correct timings.

In order to view the content of some registers and what the processor's status is we select VIEW

PROCESSOR and REGISTERS. The display should now look like this.

Avr-Asm-Tutorial 8 http://www.avr-asm-tutorial.net

The processor window displays all

values like the command counter, the

flags and the timing information (here:

1 MHz clock). The stop watch can be

used to measure the necessary time

for going through routines etc.

Now we start the program execution. We use the single step

opportunity (TRACE INTO or F11). Using GO would result in

continous exection and not much would be seen due to the high

speed of simulation. After the first executed step the processor

window should look like this.

The program counter is at step 1, the cycle counter at 2 (RJMP

needed two cycles). At 1 MHz clock two microseconds have

been wasted, the flags and pointer registers are not changed.

The source text window displays a pointer on the next command

that will be executed.

Pressing F11 again executes the next command, register mp

(=R16) will be set to 0xFF. Now the register window should

highlite this change.

Register R16's new

value is displayed in

red letters. We can

change the value of a

register at any time to

test what happens

then.

Now step 3 is

executed, output to the

direction register of Port B.

To display this we open a

new I/O view window and

select Port B. The display

should look like this.

The Data Direction

Register in the I/O-view

window of Port B now

shows the new value. The

values could be changed

manually, if desired, pin by

pin.

The next two steps

are simulated using

F11. They are not

displayed here.

Setting the output

ports to one with

the command LDI

mp,0xFF and OUT PORTB,mp results in the following picture in the I/O view. Now the output port bits are

all one, the I/O view shows this.

That is our short trip through the simulator software world. The simulator is capable to much more, so it

should be applied extensively in cases of design errors. Visit the different menue items, there is much

more than showed here.

Avr-Asm-Tutorial 9 http://www.avr-asm-tutorial.net

Register

What is a register?

Registers are special storages with 8 bits capacity and they look like this:

Bit 7 Bit 6 Bit 5 Bit 4 Bit 3 Bit 2 Bit 1 Bit 0

Note the numeration of these bits: the least significant bit starts with zero (20 = 1).

A register can either store numbers from 0 to 255 (positive number, no negative values), or numbers from

-128 to +127 (whole number with a sign bit in bit 7), or a value representing an ASCII-coded character

(e.g. 'A'), or just eight single bits that do not have something to do with each other (e.g. for eight single

flags used to signal eight different yes/no decisions).

The special character of registers, compared to other storage sites, is that

• they can be used directly in assembler commands,

• operations with their content require only a single command word,

• they are connected directly to the central processing unit called the accumulator,

• they are source and target for calculations.

There are 32 registers in an AVR. They are originally named R0 to R31, but you can choose to name them

to more meaningful names using an assembler directive. An example:

.DEF MyPreferredRegister = R16

Assembler directives always start with a dot in column 1 of the text. Instructions do NEVER start in column

1, they are always preceeded by a Tab- or blank character!

Note that assembler directives like this are only meaningful for the assembler but do not produce any code

that is executable in the AVR target chip. Instead of using the register name R16 we can now use our own

name MyPreferredRegister, if we want to use R16 within a command. So we write a little bit more text each

time we use this register, but we have an association what might be the content of this register.

Using the command line

LDI MyPreferredRegister, 150

which means: load the number 150 immediately to the register R16, LoaD Immediate. This loads a fixed

value or a constant to that register. Following the assembly or translation of this code the program storage

written to the AVR chip looks like this:

000000 E906

The load command code as well as the target register (R16) as well as the value of the constant (150) is

part of the hex value E906, even if you don't see this directly. Don't be afraid: you don't have to remember

this coding because the assembler knows how to translate all this to yield E906.

Within one command two different registers can play a role. The easiest command of this type is the copy

command MOV. It copies the content of one register to another register. Like this:

.DEF MyPreferredRegister = R16

.DEF AnotherRegister = R15

LDI MyPreferredRegister, 150

MOV AnotherRegister, MyPreferredRegister

The first two lines of this monster program are directives that define the new names of the registers R16

and R15 for the assembler. Again, these lines do not produce any code for the AVR. The command lines

with LDI and MOV produce code:

000000 E906

000001 2F01

The commands write 150 into register R16 and copy its content to the target register R15. IMPORTANT

NOTE:

The first register is always the target register where the result is written to!

(This is unfortunately different from what one expects or from how we speak. It is a simple convention that

was once defined that way to confuse the beginners learning assembler. That is why assembler is that

complicated.)

Avr-Asm-Tutorial 10 http://www.avr-asm-tutorial.net

Different registers

The beginner might want to write the above commands like this:

.DEF AnotherRegister = R15

LDI AnotherRegister, 150

And: you lost. Only the registers from R16 to R31 load a constant immediately with the LDI command, R0

to R15 don't do that. This restriction is not very fine, but could not be avoided during construction of the

command set for the AVRs.

There is one exception from that rule: setting a register to Zero. This command

CLR MyPreferredRegister

is valid for all registers.

Besides the LDI command you will find this register class restriction with the following additional

commands:

• ANDI Rx,K ; Bit-And of register Rx with a constant value K,

• CBR Rx,M ; Clear all bits in register Rx that are set to one within the constant mask value M,

• CPI Rx,K ; Compare the content of the register Rx with a constant value K,

• SBCI Rx,K ; Subtract the constant K and the current value of the carry flag from the content of

register Rx and store the result in register Rx,

• SBR Rx,M ; Set all bits in register Rx to one, that are one in the constant mask M,

• SER Rx ; Set all bits in register Rx to one (equal to LDI Rx,255),

• SUBI Rx,K ; Subtract the constant K from the content of register Rx and store the result in register

Rx.

In all these commands the register must be between R16 and R31! If you plan to use these commands

you should select one of these registers for that operation. It is easier to program. This is an additional

reason why you should use the directive to define a register's name, because you can easier change the

registers location afterwards.

Pointer-register

A very special extra role is defined for the register pairs R26:R27, R28:R29 and R30:R31. The role is so

important that these pairs have extra names in AVR assembler: X, Y and Z. These pairs are 16-bit pointer

registers, able to point to adresses with max. 16-bit into SRAM locations (X, Y or Z) or into locations in

program memory (Z).

The lower byte of the 16-bit-adress is located in the lower register, the higher byte in the upper register.

Both parts have their own names, e.g. the higher byte of Z is named ZH (=R31), the lower Byte is ZL

(=R30). These names are defined in the standard header file for the chips. Dividing these 16-bit-pointernames into two different bytes is done like follows:

.EQU Adress = RAMEND ; RAMEND is the highest 16-bit adress in SRAM

LDI YH,HIGH(Adress) ; Set the MSB

LDI YL,LOW(Adress) ; Set the LSB

Accesses via pointers are programmed with specially designed commands. Read access is named LD

(LoaD), write access named ST (STore), e.g. with the X-pointer:

Pointer Sequence Examples

X Read/Write from adress X, don't change the pointer LD R1,X or ST X,R1

X+ Read/Write from/to adress X and increment the pointer afterwards by

LD R1,X+ or ST X+,R1

one

-X Decrement the pointer by one and read/write from/to the new adress

LD R1,-X or ST -X,R1

afterwards

Similiarly you can use Y and Z for that purpose.

There is only one command for the read access to the program storage. It is defined for the pointer pair Z

and it is named LPM (Load from Program Memory). The command copies the byte at adress Z in the

program memory to the register R0. As the program memory is organised word-wise (one command on

one adress consists of 16 bits or two bytes or one word) the least significant bit selects the lower or higher

byte (0=lower byte, 1= higher byte). Because of this the original adress must be multiplied by 2 and access

is limited to 15-bit or 32 kB program memory. Like this:

Avr-Asm-Tutorial 11 http://www.avr-asm-tutorial.net

LDI ZH,HIGH(2*Adress)

LDI ZL,LOW(2*Adress)

LPM

Following this command the adress must be incremented to point to the next byte in program memory. As

this is used very often a special pointer incrementation command has been defined to do this:

ADIW ZL,1

LPM

ADIW means ADd Immediate Word and a maximum of 63 can be added this way. Note that the assembler

expects the lower of the pointer register pair ZL as first parameter. This is somewhat confusing as addition

is done as 16-bit- operation.

The complement command, subtracting a constant value of between 0 and 63 from a 16-bit pointer

register is named SBIW, Subtract Immediate Word. (SuBtract Immediate Word). ADIW and SBIW are

possible for the pointer register pairs X, Y and Z and for the register pair R25:R24, that does not have an

extra name and does not allow access to SRAM or program memory locations. R25:R24 is ideal for

handling 16-bit values.

How to insert that table of values in the program memory? This is done with the assembler directives .DB

and .DW. With that you can insert bytewise or wordwise lists of values. Bytewise organised lists look like

this:

.DB 123,45,67,89 ; a list of four bytes

.DB "This is a text. " ; a list of byte characters

You should always place an even number of bytes on each single line. Otherwise the assembler will add a

zero byte at the end, which might be unwanted.

The similiar list of words looks like this:

.DW 12345,6789 ; a list of two words

Instead of constants you can also place labels (jump targets) on that list, like that:

Label1:

[ ... here are some commands ... ]

Label2:

[ ... here are some more commands ... ]

Table:

.DW Label1,Label2 ; a wordwise list of labels

Labels ALWAYS start in column 1!. Note that reading the labels with LPM first yields the lower byte of the

word.

A very special application for the pointer registers is the access to the registers themselves. The registers

are located in the first 32 bytes of the chip's adress space (at adress 0x0000 to 0x001F). This access is

only meaningful if you have to copy the register's content to SRAM or EEPROM or read these values from

there back into the registers. More common for the use of pointers is the access to tables with fixed values

in the program memory space. Here is, as an example, a table with 10 different 16-bit values, where the

fifth table value is read to R25:R24:

MyTable:

.DW 0x1234,0x2345,0x3456,0x4568,0x5678 ; The table values, wordwise

.DW 0x6789,0x789A,0x89AB,0x9ABC,0xABCD ; organised

Read5: LDI ZH,HIGH(MyTable*2) ; Adress of table to pointer Z

LDI ZL,LOW(MyTable*2) ; multiplied by 2 for bytewise access

ADIW ZL,10 ; Point to fifth value in table

LPM ; Read least significant byte from program memory

MOV R24,R0 ; Copy LSB to 16-bit register

ADIW ZL,1 ; Point to MSB in program memory

LPM ; Read MSB of table value

MOV R25,R0 ; Copy MSB to 16-bit register

This is only an example. You can calculate the table adress in Z from some input value, leading to the

respective table values. Tables can be organised byte- or character-wise, too.

Recommendation for the use of registers

• Define names for registers with the .DEF directive, never use them with their direct name Rx.

• If you need pointer access reserve R26 to R31 for that purpose.

• 16-bit-counter are best located R25:R24.

• If you need to read from the program memory, e.g. fixed tables, reserve Z (R31:R30) and R0 for that

purpose.

• If you plan to have access to single bits within certain registers (e.g. for testing flags), use R16 to

R23 for that purpose.

Avr-Asm-Tutorial 12 http://www.avr-asm-tutorial.net

Ports

What is a Port?

Ports in the AVR are gates from the central processing unit to internal and external hard- and software

components. The CPU communicates with these components, reads from them or writes to them, e.g. to

the timers or the parallel ports. The most used port is the flag register, where results of previous operations

are written to and branch conditions are read from.

There are 64 different ports, which are not physically available in all different AVR types. Depending on the

storage space and other internal hardware the different ports are either available and accessable or not.

Which of these ports can be used is listed in the data sheets for the processor type.

Ports have a fixed address, over which the CPU communicates. The address is independent from the type

of AVR. So e.g. the port adress of port B is always 0x18 (0x stands for hexadecimal notation). You don't

have to remember these port adresses, they have convenient aliases. These names are defined in the

include files (header files) for the different AVR types, that are provided from the producer. The include

files have a line defining port B's address as follows:

.EQU PORTB, 0x18

So we just have to remember the name of port B, not its location in the I/O space of the chip. The include

file 8515def.inc is involved by the assembler directive

.INCLUDE "C:\Somewhere\8515def.inc"

and the registers of the 8515 are all defined then and easily accessable.

Ports usually are organised as 8-bit numbers, but can also hold up to 8 single bits that don't have much to

do with each other. If these single bits have a meaning they have their own name associated in the include

file, e.g. to enable manipulation of a single bit. Due to that name convention you don't have to remember

these bit positions. These names are defined in the data sheets and are given in the include file, too. They

are provided here in the port tables.

As an example the MCU General Control Register, called MCUCR, consists of a number of single control

bits that control the general property of the chip (see the description in MCUCR in detail). It is a port, fully

packed with 8 control bits with their own names (ISC00, ISC01, ...). Those who want to send their AVR to

a deep sleep need to know from the data sheet how to set the respective bits. Like this:

.DEF MyPreferredRegister = R16

LDI MyPreferredRegister, 0b00100000

OUT MCUCR, MyPreferredRegister

SLEEP

The Out command brings the content of my preferred register, a Sleep-Enable-Bit called SE, to the port

MCUCR and sets the AVR immediately to sleep, if there is a SLEEP instruction executed. As all the other

bits of MCUCR are also set by the above instructions and the Sleep Mode bit SM was set to zero, a mode

called half-sleep will result: no further command execution will be performed but the chip still reacts to

timer and other hardware interrupts. These external events interrupt the big sleep of the CPU if they feel

they should notify the CPU.

Reading a port's content is in most cases possible using the IN command. The following sequence

.DEF MyPreferredRegister = R16

IN MyPreferredRegister, MCUCR

reads the bits in port MCUCR to the register. As many ports have undefined and unused bits in certain

ports, these bits always read back as zeros.

More often than reading all 8 bits of a port one must react to a certain status of a port. In that case we don't

need to read the whole port and isolate the relevant bit. Certain commands provide an opportunity to

execute commands depending on the level of a certain bit (see the JUMP section). Setting or clearing

certain bits of a port is also possible without reading and writing the other bits in the port. The two

commands are SBI (Set Bit I/o) and CBI (Clear Bit I/o). Execution is like this:

.EQU ActiveBit=0 ; The bit that is to be changed

SBI PortB, ActiveBit ; The bit will be set to one

CBI PortB, Activebit ; The bit will be cleared to zero

These two instructions have a limitation: only ports with an adress smaller than 0x20 can be handled, ports

above cannot be accessed that way.

For the more exotic programmer: the ports can be accessed using SRAM access commands, e.g. ST and

LD. Just add 0x20 to the port's adress (the first 32 addresses are the registers!) and access the port that

way. Like demonstrated here:

.DEF MyPreferredRegister = R16

LDI ZH,HIGH(PORTB+32)

Avr-Asm-Tutorial 13 http://www.avr-asm-tutorial.net

LDI ZL,LOW(PORTB+32)

LD MyPreferredRegister,Z

That only makes sense in certain cases, but it is possible. It is the reason why the first address location of

the SRAM is always 0x60.

Details of relevant ports in the AVR

The following table holds the most used ports. Not all ports are listed here, some of the MEGA and

AT90S4434/8535 types are skipped. If in doubt see the original reference.

Component Portname Port-Register

Accumulator SREG Status Register

Stack SPL/SPH Stackpointer

External SRAM/External Interrupt MCUCR MCU General Control Register

External Interrupt GIMSK Interrupt Mask Register

GIFR Interrupt Flag Register

Timer Interrupt TIMSK Timer Interrupt Mask Register

TIFR Timer Interrupt Flag Register

Timer 0 TCCR0 Timer/Counter 0 Control Register

TCNT0 Timer/Counter 0

Timer 1 TCCR1A Timer/Counter Control Register 1 A

TCCR1B Timer/Counter Control Register 1 B

TCNT1 Timer/Counter 1

OCR1A Output Compare Register 1 A

OCR1B Output Compare Register 1 B

ICR1L/H Input Capture Register

Watchdog Timer WDTCR Watchdog Timer Control Register

EEPROM EEAR EEPROM Adress Register

EEDR EEPROM Data Register

EECR EEPROM Control Register

SPI SPCR Serial Peripheral Control Register

SPSR Serial Peripheral Status Register

SPDR Serial Peripheral Data Register

UART UDR UART Data Register

USR UART Status Register

UCR UART Control Register

UBRR UART Baud Rate Register

Analog Comparator ACSR Analog Comparator Control and Status Register

I/O-Ports PORTx Port Output Register

DDRx Port Direction Register

PINx Port Input Register

The status register as the most used port

By far the most often used port is the status register with its 8 bits. Usually access to this port is only by

automatic setting and clearing bits by the CPU or accumulator, some access is by reading or branching on

certain bits in that port, in a few cases it is possible to manipulate these bits directly (using the assembler

command SEx or CLx, where x is the bit abbreviation). Most of these bits are set or cleared by the

accumulator through bit-test, compare- or calculation-operations. The following list has all assembler

commands that set or clear status bits depending on the result of the execution.

Avr-Asm-Tutorial 14 http://www.avr-asm-tutorial.net

Bit Calculation Logic Compare Bits Shift Other

Z ADD, ADC, ADIW, DEC,

INC, SUB, SUBI, SBC,

SBCI, SBIW

C ADD, ADC, ADIW, SUB,

SUBI, SBC, SBCI, SBIW

N ADD, ADC, ADIW, DEC,

INC, SUB, SUBI, SBC,

SBCI, SBIW

V ADD, ADC, ADIW, DEC,

INC, SUB, SUBI, SBC,

SBCI, SBIW

S SBIW - - BCLR S,

H ADD, ADC, SUB, SUBI,

SBC, SBCI

T - - - BCLR T,

AND, ANDI, OR,

ORI, EOR, COM,

NEG, SBR, CBR

COM, NEG CP, CPC,

AND, ANDI, OR,

ORI, EOR, COM,

NEG, SBR, CBR

AND, ANDI, OR,

ORI, EOR, COM,

NEG, SBR, CBR

NEG CP, CPC,

CP, CPC,

CPI

CPI

CP, CPC,

CPI

CP, CPC,

CPI

CPI

BCLR Z,

BSET Z, CLZ,

SEZ, TST

BCLR C,

BSET C,

CLC, SEC

BCLR N,

BSET N, CLN,

SEN, TST

BCLR V,

BSET V, CLV,

SEV, TST

BSET S, CLS,

SES

BCLR H,

BSET H, CLH,

SEH

BSET T, BST,

CLT, SET

ASR, LSL,

LSR, ROL,

ROR

ASR, LSL,

LSR, ROL,

ROR

ASR, LSL,

LSR, ROL,

ROR

ASR, LSL,

LSR, ROL,

ROR

- -

- -

- -

CLR

-

CLR

CLR

I - - - BCLR I, BSET

I, CLI, SEI

Port details

Port details of the most common ports are shown in an extra table (see annex).

- RETI

Avr-Asm-Tutorial 15 http://www.avr-asm-tutorial.net

SRAM

Using SRAM in AVR assembler language

Nearly all AT90S-AVR-type MCUs have static RAM (SRAM) on board (some don't). Only very simple

assembler programs can avoid using this memory space by putting all info into registers. If you run out of

registers you should be able to program the SRAM to utilize more space.

What is SRAM?

SRAM are memories that are not directly accessable to the central processing unit (Arithmetic and Logical

Unit ALU, sometimes called

accumulator) like the registers

are. If you access these

memory locations you usually

use a register as interim

storage. In the following

example a value in SRAM will

be copied to the register R2

(1st command), a calculation

with the value in R3 is made

and the result is written to R3

(command 2). After that this

value is written back to the

SRAM location (command 3,

not shown here).

So it is clear that operations with values stored in the SRAM are slower to perform than those using

registers alone. On the other hand: the smallest AVR type has 128 bytes of SRAM available, much more

than the 32 registers can hold.

The types from AT90S8515 upwards offer the additional opportunity to connect additional external RAM,

expanding the internal 512 bytes. From the assembler point-of-view, external SRAM is accessed like

internal SRAM. No extra commands must be used for that external SRAM.

For what purposes can I use SRAM?

Besides simple storage of values, SRAM offers additional opportunities for its use. Not only access with

fixed addresses is possible, but also the use of pointers, so that floating access to subsequent locations

can be programmed. This way you can build up ring buffers for interim storage of values or calculated

tables. This is not very often used with registers, because they are too few and prefer fixed access.

Even more relative is the access using an offset to a fixed starting address in one of the pointer registers.

In that case a fixed address is stored in a pointer register, a constant value is added to this address and

read/write access is made to that address with an offset. With that kind of access tables are better used.

The most relevant use for SRAM is the so-called stack. You can push values to that stack, be it the content

of a register, a return address prior to calling a subroutine, or the return address prior to an hardwaretriggered interrupt.

How to use SRAM?

To copy a value to a memory location in SRAM you have to define the address. The SRAM addresses you

can use reach from 0x0060 (hex notation) to the end of the physical SRAM on the chip (in the AT90S8515

the highest accessable internal SRAM location is 0x025F). With the command

STS 0x0060, R1

the content of register R1 is copied to the first SRAM location. With

LDS R1, 0x0060

the SRAM content at address 0x0060 is copied to the register. This is the direct access with an address

that has to be defined by the programmer.

Symbolic names can be used to avoid handling fixed addresses, that require a lot of work, if you later want

to change the structure of your data in the SRAM. These names are easier to handle than hex numbers, so

give that address a name like:

.EQU MyPreferredStorageCell = 0x0060

Avr-Asm-Tutorial 16 http://www.avr-asm-tutorial.net

STS MyPreferredStorageCell, R1

Yes, it isn't shorter, but easier to remember. Use whatever name that you find to be convenient.

Another kind of access to SRAM is the use of pointers. You need two registers for that purpose, that hold

the 16-bit address of the location. As we learned in the Pointer-Register-Division pointer registers are the

pairs X (XH:XL, R27:R26), Y (YH:YL, R29:R28) and Z (ZH:ZL, R31:R30). They allow access to the

location they point to directly (e.g. with ST X, R1), after prior decrementing the address by one (e.g. ST -X,

R1) or with subsequent incrementation of the address (e.g. ST X+, R1). A complete access to three cells

in a row looks like this:

.EQU MyPreferredStorageCell = 0x0060

.DEF MyPreferredRegister = R1

.DEF AnotherRegister = R2

.DEF AndAnotherRegister = R3

LDI XH, HIGH(MyPreferredStorageCell)

LDI XL, LOW(MyPreferredStorageCell)

LD MyPreferredRegister, X+

LD AnotherRegister, X+

LD AndAnotherRegister, X

Easy to operate, those pointers. And as easy as in other languages than assembler, that claim to be

easier to learn.

The third construction is a little bit more exotic and only experienced programmers use this. Let's assume

we very often in our program need to access three SRAM locations. Let's futher assume that we have a

spare pointer register pair, so we can afford to use it exclusively for our purpose. If we would use the

ST/LD instructions we always have to change the pointer if we access another location. Not very

convenient.

To avoid this, and to confuse the beginner, the access with offset was invented. During that access the

register value isn't changed. The address is calculated by temporarly adding the fixed offset. In the above

example the access to location 0x0062 would look like this. First, the pointer register is set to our central

location 0x0060:

.EQU MyPreferredStorageCell = 0x0060

.DEF MyPreferredRegister = R1

LDI YH, HIGH(MyPreferredStorageCell)

LDI YL, LOW(MyPreferredStorageCell)

Somewhere later in the program I'd like to access cell 0x0062:

STD Y+2, MyPreferredRegister

Note that 2 is not really added to Y, just temporarly. To confuse you further, this can only be done with the

Y- and Z-register-pair, not with the X-pointer!

The corresponding instruction for reading from SRAM with an offset

LDD MyPreferredRegister, Y+2

is also possible.

That's it with the SRAM, but wait: the most relevant use as stack is still to be learned.

Use of SRAM as stack

The most common use of SRAM is its use as stack. The stack is a tower of wooden blocks. Each

additional block goes onto the top of the tower, each recall of a value removes the upmost block from the

tower. This structure is called Last-In-First-Out (LIFO) or easier: the last to go on top will be the first

coming down.

Defining SRAM as stack

To use SRAM as stack requires the setting of the stack pointer first. The stack pointer is a 16-bit-pointer,

accessable like a port. The double register is named SPH:SPL. SPH holds the most significant address

byte, SPL the least significant. This is only true, if the AVR type has more than 256 byte SRAM. If not, SPH

is undefined and must not and cannot be used. We assume we have more than 256 bytes in the following

examples.

To construct the stack the stack pointer is loaded with the highest available SRAM address. (In our case

the tower grows downwards, towards lower addresses!).

.DEF MyPreferredRegister = R16

LDI MyPreferredRegister, HIGH(RAMEND) ; Upper byte

OUT SPH,MyPreferredRegister ; to stack pointer

LDI MyPreferredRegister, LOW(RAMEND) ; Lower byte

OUT SPL,MyPreferredRegister ; to stack pointer

Avr-Asm-Tutorial 17 http://www.avr-asm-tutorial.net

The value RAMEND is, of course, specific for the processor type. It is defined in the INCLUDE file for the

processor type. The file 8515def.inc has the line:

.equ RAMEND =$25F ; Last On-Chip SRAM Location

The file 8515def.inc is included with the assembler directive

.INCLUDE "C:\somewhere\8515def.inc"

at the beginning of our assembler source code.

So we defined the stack now, and we don't have to care about the stack pointer any more, because

manipulations of that pointer are automatic.

Use of the stack

Using the stack is easy. The content of registers are pushed onto the stack like this:

PUSH MyPreferredRegister ; Throw that value

Where that value goes to is totally uninteresting. That the stack pointer was decremented after that push,

we don't have to care. If we need the content again, we just add the following instruction:

POP MyPreferredRegister ; Read back the value

With POP we just get the value that was last pushed on top of the stack. Pushing and popping registers

makes sense, if

• the content is again needed some lines of code later,

• all registers are in use, and if

• no other opportunity exists to store that value somewhere else.

If these conditions are not given, the use of the stack for saving registers is useless and just wastes

processor time.

More sense makes the use of the stack in subroutines, where you have to return to the program location

that called the routine. In that case the calling program code pushes the return address (the current

program counter value) onto the stack and jumps to the subroutine. After its execution the subroutine pops

the return address from the stack and loads it back into the program counter. Program execution is

continued exactly one instruction behind the call instruction:

RCALL Somewhat ; Jump to the label somewhat

[...] here we continue with the program.

Here the jump to the label somewhat somewhere in the program code,

Somewhat: ; this is the jump address

[...] Here we do something

[...] and we are finished and want to jump back to the calling location:

RET

During execution of the RCALL instruction the already incremented program counter, a 16-bit-address, is

pushed onto the stack, using two pushes. By reaching the RET instruction the content of the previous

program counter is reloaded with two pops and execution continues there.

You don't need to care about the address of the stack, where the counter is loaded to. This address is

automatically generated. Even if you call a subroutine within that subroutine the stack function is fine. This

just packs two return addresses on top of the stack, the nested subroutine removes the first one, the

calling subroutine the remaining one. As long as there is enough SRAM, everything is fine.

Servicing hardware interrupts isn't possible without the stack. Interrupts stop the normal exection of the

program, wherever the program currently is. After execution of a specific service routine as a reaction to

that interrupt program execution must return to the previous location, before the interrupt occurred. This

would not be possible if the stack is not able to store the return address.

The enormous advances of having a stack for interrupts are the reason, why even the smallest AVRs

without having SRAM have at least a very small hardware stack.

Bugs with the stack operation

For the beginner there are a lot of possible bugs, if you first learn to use stack.

Very clever is the use of the stack without first setting the stack pointer. Because this pointer is set to zero

at program start, the pointer points to register R0. Pushing a byte results in a write to that register,

overwriting its previous content. An additional push to the stack writes to 0xFFFF, an undefined position (if

you don't have external SRAM there). A RCALL and RET will return to a strange address in program

memory. Be sure: there is no warning, like a window popping up saying something like „Illegal Access to

Mem location xxxx“.

Avr-Asm-Tutorial 18 http://www.avr-asm-tutorial.net

Another opportunity to construct bugs is to forget to pop a previously pushed value, or popping a value

without pushing one first.

In a very few cases the stack overflows to below the first SRAM location. This happens in case of a neverending recursive call. After reaching the lowest SRAM location the next pushes write to the ports (0x005F

down to 0x0020), then to the registers (0x001F to 0x0000). Funny and unpredictable things happen with

the chip hardware, if this goes on. Avoid this bug, it can even destroy your hardware!

Avr-Asm-Tutorial 19 http://www.avr-asm-tutorial.net

Jumping and Branching

Here we discuss all commands that control the sequential execution of a program. It starts with the starting

sequence on power-up of the processor, jumps, interrupts, etc.

Controlling sequential execution of the program

What happens during a reset?

When the power supply of an AVR rises and the processor starts its work, the hardware triggers a reset

sequence. The counter for the program steps will be set to zero. At this address the execution always

starts. Here we have to have our first word of code. But not only during power-up this address is activated:

• During an external reset on the reset pin a restart is executed.

• If the Watchdog counter reaches its maximum count, a reset is initiated. A watchdog timer is an

internal clock that must be resetted from time to time by the program, otherwise it restarts the

processor.

• You can call reset by a direct jump to that address (see the jump section below).

The third case is not a real reset, because the automatic resetting of register- and port-values to a welldefined default value is not executed. So, forget that for now.

The second option, the watchdog reset, must first be enabled by the program. It is disabled by default.

Enabling requires write commands to the watchdog's port. Setting the watchdog counter back to zero

requires the execution of the command

WDR

to avoid a reset.

After execution of a reset, with setting registers and ports to default values, the code at address 0000 is

wordwise read to the execution part of the processor and is executed. During that execution the program

counter is already incremented by one and the next word of code is already read to the code fetch buffer

(Fetch during Execution). If the executed command does not require a jump to another location in the

program the next command is executed immediately. That is why the AVRs execute extremely fast, each

clock cycle executes one command (if no jumps occur).

The first command of an executable is always located at address 0000. To tell the compiler (assembler

program) that our source code starts now and here, a special directive can be placed at the beginning,

before the first code in the source is written:

.CSEG

.ORG 0000

The first directive lets the compiler switch to the code section. All following is translated as code and is

written to the program memory section of the processor. Another target segment would be the EEPROM

section of the chip, where you also can write bytes or words to.

.ESEG

The third segment is the SRAM section of the chip.

.DSEG

Other than with EEPROM content, that really goes to the EEPROM during programming of the chip, the

DSEG segment content is not programmed to the chip. It is only used for correct label calculation during

the assembly process.

The ORG directive above stands for origin and manipulates the address within the code segment, where

assembled words go to. As our program always starts at 0x0000 the CSEG/ORG directives are trivial, you

can skip these without getting into an error. We could start at 0x0100, but that makes no real sense as the

processor starts execution at 0000. If you want to place a table exactly to a certain location of the code

segment, you can use ORG. If you want to set a clear sign within your code, after first defining a lot of

other things with .DEF- and .EQU-directives, use the CSEG/ORG sequence, even though it might not be

necessary to do that.

As the first code word is always at address zero, this location is also called the reset vector. Following the

reset vector the next positions in the program space, addresses 0x0001, 0x0002 etc., are interrupt vectors.

These are the positions where the execution jumps to if an external or internal interrupt has been enabled

and occurs. These positions called vectors are specific for each processor type and depend on the internal

hardware available (see below). The commands to react to such an interrupt have to be placed to the

proper vector location. If you use interrupts, the first code, at the reset vector, must be a jump command, to

jump over the other vectors. Each interrupt vector must hold a jump command to the respective interrupt

service routine. The typical program sequence at the beginning is like follows:

Avr-Asm-Tutorial 20 http://www.avr-asm-tutorial.net

.CSEG

.ORG 0000

RJMP Start

RJMP IntServRout1

[...] here we place the other interrupt vector commands

[...] and here is a good place for the interrupt service routines themselves

Start: ; This here is the program start

[...] Here we place our main program

The command RJMP results in a jump to the label Start:, located some lines below. Remeber, labels

always start in column 1 of the source code and end with a :. Labels, that don't fulfil these conditions are

not taken for serious by many compiler. Missing labels result in an error message ("Undefined label"), and

compilation is interrupted.

Linear program execution and branches

Program execution is always linear, if nothing changes the sequential execution. These changes are the

execution of an interrupt or of branching instructions.

Branching is very often depending on some condition, conditioned branching. As an example we assume

we want to construct a 32-bit-counter using registers R1 to R4. The least significant byte in R1 is

incremented by one. If the register overflows during that operation (255 + 1 = 0), we have to increment R2

similiarly. If R2 overflows, we have to increment R3, and so on.

Incrementation by one is done with the instruction INC. If an overflow occurs during that execution of

INC R1 the zero bit in the status register is set to one (the result of the operation is zero). The carry bit in

the status register, usually set by overflows, is not changed during an INC. This is not to confuse the

beginner, but carry is used for other purposes instead. The Zero-Bit or Zero-flag in this case is enough to

detect an overflow. If no overflow occurs we can just leave the counting sequence.

If the Zero-bit is set, we must execute additional incrementation of the other registers.To confuse the

beginner the branching command, that we have to use, is not named BRNZ but BRNE (BRanch if Not

Equal). A matter of taste ...

The whole count sequence of the 32-bit-counter should then look like this:

INC R1

BRNE GoOn32

INC R2

BRNE GoOn32

INC R3

BRNE GoOn32

INC R4

GoOn32:

So that's about it. An easy thing. The opposite condition to BRNE is BREQ or BRanch EQual.

Which of the status bits, also called processor flags, are changed during execution of a command is listed

in instruction code tables, see the List of Instructions. Similiarly to the Zero-bit you can use the other status

bits like that:

BRCC label/BRCS label; Carry-flag 0 oder 1

BRSH label; Equal or greater

BRLO label; Smaller

BRMI label; Minus

BRPL label; Plus

BRGE label; Greater or equal (with sign bit)

BRLT label; Smaller (with sign bit)

BRHC label/BRHS label; Half overflow flag 0 or 1

BRTC label/BRTS label; T-Bit 0 or 1

BRVC label/BRVS label; Two's complement flag 0 or 1

BRIE label/BRID label; Interrupt enabled or disabled

to react to the different conditions. Branching always occurs if the condition is met. Don't be afraid, most of

these commands are rarely used. For the beginner only Zero and Carry are relevant.

Timing during program execution

Like mentioned above the required time to execute one instruction is equal to the processor's clock cycle.

If the processor runs on a 4 MHz clock frequency then one instruction requires 1/4 µs or 250 ns, at 10 MHz

clock only 100 ns. The required time is as exact as the xtal clock. If you need exact timing an AVR is the

optimal solution for your problem. Note that there are a few commands that require two or more cycles,

e.g. the branching instructions (if branching occurs) or the SRAM read/write sequence. See the instruction

table for details.

Avr-Asm-Tutorial 21 http://www.avr-asm-tutorial.net

To define exact timing there must be an opportunity that does nothing else than delay program execution.

You might use other instructions that do nothing, but more clever is the use of the NO Operation command

NOP. This is the most useless instruction:

NOP

This instruction does nothing but wasting processor time. At 4 MHz clock we need just four of these

instructions to waste 1 µs. No other hidden meanings here on the NOP instruction. For a signal generator

with 1 kHz we don't need to add 4000 such instructions to our source code, but we use a software counter

and some branching instructions. With these we construct a loop that executes for a certain number of

times and are exactly delayed. A counter could be a 8-bit-register that is decremented with the DEC

instruction, e.g. like this:

CLR R1

Count:

DEC R1

BRNE Count

16-bit counting can also be used to delay exactly, like this

LDI ZH,HIGH(65535)

LDI ZL,LOW(65535)

Count:

SBIW ZL,1

BRNE Count

If you use more registers to construct nested counters you can reach any delay. And the delay is

absolutely exact, even without a hardware timer.

Macros and program execution

Very often you have to write identical or similiar code sequences on different occasions in your source

code. If you don't want to write it once and jump to it via a subroutine call you can use a macro to avoid

getting tired writing the same sequence several times. Macros are code sequences, designed and tested

once, and inserted into the code by its macro name. As an example we assume we need to delay program

execution several times by 1 µs at 4 MHz clock. Then we define a macro somewhere in the source:

.MACRO Delay1

NOP

NOP

NOP

NOP

.ENDMACRO

This definition of the macro does not yet produce any code, it is silent. Code is produced if you call that

macro by its name:

[...] somewhere in the source code

Delay1

[...] code goes on here

This results in four NOP incstructions inserted to the code at that location. An additional Delay1 inserts

additional four NOP instructions.

By calling a macro by its name you can add some parameters to manipulate the produced code. But this is

more than a beginner has to know about macros.

If your macro has longer code sequences, or if you are short in code storage space, you should avoid the

use of macros and use subroutines instead.

Subroutines

In contrary to macros a subroutine does save program storage space. The respective sequence is only

once stored in the code and is called from whatever part of the code. To ensure continued execution of the

sequence following the subroutine call you need to return to the caller. For a delay of 10 cycles you need

to write this subroutine:

Delay10:

NOP

NOP

NOP

RET

Subroutines always start with a label, otherwise you would not be able to jump to it, here Delay10:. Three

NOPs follow and a RET instruction. If you count the necessary cycles you just find 7 cycles (3 for the

NOPs, 4 for the RET). The missing 3 are for calling that routine:

[...] somewhere in the source code:

RCALL Delay10

Avr-Asm-Tutorial 22 http://www.avr-asm-tutorial.net

[...] further on with the source code

RCALL is a relative call. The call is coded as relative jump, the relative distance from the calling routine to

the subroutine is calculated by the compiler. The RET instruction jumps back to the calling routine. Note

that before you use subroutine calls you must set the stackpointer (see Stack), because the return address

must be packed on the stack by the RCALL instruction.

If you want to jump directly to somewhere else in the code you have to use the jump instruction:

[...] somewhere in the source code

RJMP Delay10

Return:

[...] further on with source code

The routine that you jumped to can not use the RET command in that case. To return back to the calling

location in the source requires to add another label and the called routine to jump back to this label.

Jumping like this is not like calling a subroutine because you can't call this routine from different locations

in the code.

RCALL and RJMP are unconditioned branches. To jump to another location, depending on some