Page 1

Retail price: U.S. $7.50, Can. $8.50

ISSUE NO. 29

Display until arrival

of Issue No. 30.

"Hip Boots,"

our classic column that

relentlessly waded through

the mire of misinformation

in the audio press, comes to

a reluctant but inevitable end.

Also in this issue:

A slew of unusually thorough loudspeaker reviews, by Don Keele,

Tom Nousaine, and Glenn Strauss.

Reviews of AV electronics, power amplifiers, and assorted other

electronic components and accessories.

Plus our standard features, columns, letters to the

Editor, CD/SACD/DVD reviews, etc.

pdf 1

Page 2

contents

Our Last Hip Boots Column

By Peter Aczel

Speakers:

Five Loudspeakers (One a Time-Honored Exotic)

and a Headphone

By Ivan Berger, D. B. Keele Jr., Tom Nousaine, and Glenn O. Strauss

2-Way Audio/Video Minimonitor Loudspeaker:

Definitive Technology StudioMonitor 450 7

Powered Monitor Speaker: Genelec HT210 13

Floor-Standing 2-Way Loudspeaker System: Thiel CS1.6 17

Floor-Standing 2-Way Speaker: Ohm Acoustics Walsh 200 Mk-2 21

2-Way Minimonitor: B&W Nautilus 805 30

Noise-Canceling Headphones: Bose QuietComfort 2 Headphones 32

AV Electronics:

High Efficiency Meets Hi-Fi, in Analog and Digital

Embodiments

By Peter Aczel and David A. Rich, Ph.D.

2- & 5-Channel Power Amplifiers: AudioControl Avalon & Pantages . . .33

DVD Audio/Video Player & 7-Channel AV Surround Receiver:

Denon DVD-9000 & AVR-5803 35

CD/SACD/DVD Digital Disc Player/Receiver: Sony AVD-S50ES 37

Peripherals:

Four Audio Side Dishes: Two Good Little Radios, the

World's Best CD Rack, and a Switcher for Recordists

By Ivan Berger

Two Good Little Radios: Boston Acoustics Recepter Radio

& Tivoli Audio PAL 45

CD Storage: Davidson-Whitehall STORAdisc LS-576 47

Recorder Switchbox: Esoteric Sound Superconnector 48

Audio's Top Urban Legend

By Tom Nousaine

Capsule CD Reviews

By Peter Aczel

Box 978: Letters to the Editor

ISSUE NO. 29 • SUMMER/FALL 2003 1

pdf 2

Page 3

2 THE AUDIO CRITIC

After Ivan Berger had written the above, further unforeseen

delays took place. What's more, and worse, we lost our second-class

mailing permit, "due to nonuse" (too true, alas). The consequences

remain to be assessed. Will we continue to publish? You bet. Adversity just makes us more stubborn. —Ed. (RA.)

From the

Still in Transition.

This is the first magazine I've ever edited completely, and

the first issue of The Audio Critic that Peter Aczel has not.

He's neither gone nor going, just taking a step back and letting

someone else—me—handle the daily work.

In the last issue, Peter introduced me as the former Technical Editor of Audio, but I feel some further introduction is in

order.

I've been writing about audio since my beard was black,

stereo was new, and everything was analog. I appreciate good

sound, maintain a healthy skepticism about the "scientific"

claims of manufacturers and designers, and realize that audio

components can sound good even when those claims do not

make sense—and sound bad even when they do.

My writings have appeared in many magazines, several languages (including Portuguese and Flemish), and under a few

pen names. (At one time, I was writing for Audio, Stereo Re-

view, and High Fidelity, which the magazines didn't mind as

long as I used a separate name for each; an editor once called

me "three of the best-known hi-fi writers in America.") I've

also been an editor at Popular Mechanics, Popular Electronics,

and Video, as well as Audio. It's my editing that counts, here,

and you can judge that for yourselves.

Of the other transitions Peter Aczel mentioned in the last

issue, the partnership with The CM Group stopped progressing, and is gone. Progress has been made in getting us caught

up with our four-time-a-year schedule; we're far from there, as

yet, but we're continuing to move in that direction. This issue

came a little faster than the last; the next should come faster

still.

Editor and Publisher

Peter Aczel

Guest Editor

Ivan Berger

Technical Editor David A. Rich

Contributing Editor D. B. Keele Jr.

Contributing Editor Tom Nousaine

Contributing Editor Glenn O. Strauss

Technical Consultant (RF) Richard T. Modafferi

Art Director Michele Raes

Design and Prepress Tom Aczel

Layout Daniel MacBride

Business Manager Bodil Aczel

The Audio Critic® (ISSN 0146-4701) is published at

somewhat irregular intervals (the eventual goal being four

times a year), for $24 per four issues, by Critic Publications,

Inc., 1380 Masi Road, Quakertown, PA 18951 -5221. Post-

master: Send address changes to The Audio Critic, P.O.

Box 978, Quakertown, PA 18951-0978.

Any conclusion, rating, recommendation, criticism, or

caveat published by The Audio Critic represents the

personal findings and judgments of the Editor and the

Staff, based only on the equipment available to their scrutiny

and on their knowledge of the subject, and is therefore not

offered to the reader as an infallible truth nor as an irreversible opinion applying to all extant and forthcoming samples of a particular product. Address all editorial correspondence to The Editor, The Audio Critic, P.O. Box 978,

Quakertown, PA 18951-0978.

Contents of this issue copyright © 2003 by Critic Publications, Inc. All rights reserved under international and

Pan-American copyright conventions. Reproduction in

whole or in part is prohibited without the prior written permission of the Editor. Paraphrasing of product reviews for

advertising or commercial purposes is also prohibited without prior written permission. The Audio Critic will use all

available means to prevent or prosecute any such unauthorized use of its material or its name.

Subscription Information and Rates

You do not need a special form. Simply write your name

and address as legibly as possible on any piece of paper.

Preferably print or type. Enclose with payment. That's all.

We also accept VISA, MasterCard, and Discover, either by

mail, by telephone, or by fax.

We currently have only two subscription rates. If you live

in the U.S. or Canada, you pay $24 for four issues. If you

live in any other country, you pay $38 for a four-issue subscription by airmail. All payments from abroad, including

Canada, must be in U.S. funds, collectable in the U.S.

without a service charge.

You may start your subscription with any issue, although

we feel that new subscribers should have a few back issues to gain a better understanding of what The Audio

Critic is all about. We still have Issues No. 11,13, and 16

through 28 in stock. Issues earlier than No. 11 are now out

of print, as are No. 1 2, No. 14, and No. 15. Specify which

issues you want (at $24 per four). Please note that we don't

sell single issues by mail. You'll find those at somewhat

higher cost at selected newsdealers, bookstores, and audio stores.

Address all subscriptions to:

The Audio Critic, P.O. Box 978,

Quakertown, PA 18951-0978.

VISA/MasterCard/Discover: (215) 538-9555

Fax:(215)538-5432

Printed in Canada

pdf 3

Page 4

Some of our readers still don't understand what kind of letter is likely to be

published in this column. Zen hint to the intuitive: not the kind that begins with

"I have a Schmigehgie QX-200 amplifier-in your opinion is it. . ." Please

address all editorial correspondence to the Editor, The Audio Critic, P.O.

Box 978, Quakertown, PA 18951 0978.

to the Editor

The Audio Critic:

I hope Issue No. 28 was not the last

issue of The Audio Critic, since it shines

by an absence of the typical technical

nonsense that I find in all the other audio magazines. On top of that the tone

of presentation makes it so much more

readable than often in the past.

In the introduction to "Speakers"

(page 15), you point out that good

speaker design is the sum of many,

many aspects that were properly dealt

with. I agree wholeheartedly, and also

with your example of the Waveform

Mach 17 speaker system. Yet this

speaker, and all the ones that Floyd

Toole referred to in the feature article,

suffer from being caught in the box paradigm. The ultimate performance and

accuracy of reproduction that can be

achieved within this paradigm are limited, and the best of Toole's examples

have reached that plateau.

There are two fundamental problems with box speakers: (1) selective reradiation of the sound energy inside

the box through the cone and walls and

(2) a power response, or directivity index, that changes at least 10 dB between low and high frequencies. The

reradiation problem has been addressed

to varying degrees of success by different designers. Constant power response,

though, requires drivers and box features that decrease in size as frequency

increases, to maintain wide and uniform polar response beyond what the

speakers in Toole's article achieve. The

result of failing to deal with these two

problems is the typical, generic box-

loudspeaker sound that is immediately

recognized in comparison to live, unamplified sounds.

Loudspeakers end up in rooms. The

off-axis radiation therefore matters, as

Toole's findings clearly point out, but

10 dB variation in power response is too

much and limits this design approach.

The improvement beyond it is via omnidirectional box speakers or full-range,

open-baffle dipole speakers. Some planar electrostatic or magnetic designs

show the potential of this approach,

but ultimately they are limited by being acoustically too large at higher frequencies, yet having insufficient volume displacement for low-frequency

reproduction at near realistic levels.

These problems can be overcome with

conventional dynamic drivers on open

baffles. As it turns out, such speakers are

significantly less sensitive to the room

both below and above 500 Hz.

The "preservation of the art" problem, or the "circle of confusion," can

only be resolved by using unamplified

sound as a reference and not other loudspeakers. This will also point out the

need to reduce nonlinear distortion and

stored energy, which are at least equal

in importance to the different steadystate frequency responses.

Siegfried Linkwitz

Linkwitz Lab

Corte Madera, CA

Siegfried Linkwitz is one of the most

distinguished practitioners in audio—

what audiophile hasn't heard of the

Linkwitz-Riley crossover? He was a

Hewlett-Packard scientist before he

started designing loudspeaker systems for

Audio Artistry and Linkwitz Lab, all of

which are based on the dipole principle.

Thus the above letter is motivated by a designer's agenda, but that doesn't make it

less valid. The arguments in favor of the

dipole approach are powerful and not to

be ignored. We wish we could test one of

the Linkwitz-designed loudspeakers—

how about it, Siegfried? We listed you as

one of the White Hats (good guys of audio) in Issue No. 24, but that was based

mainly on your engineering papers and

spoken commentary, not specific products.

It's time for some hands-on. As for your

favorable comments on our publication,

they couldn't come from a more authoritative source and are therefore especially

welcome.

—Ed.

The Audio Critic:

In response to Issue No. 28, "Sci-

ence in the Service of Art"—is Floyd E.

Toole colorblind? First picture: a por-

trait painted under a light with 3 dB too

much red versus when viewed under

natural, neutral light. I've been painting for over 40 years and I never knew

light could be measured in dB.

As for the rest of your magazine,

you've done better. As far as your plan

to retire to a primarily supervisory position is concerned, just retire and let

Ivan Berger take over.

Your "Hip Boots" column is sorely

missed because it keeps the crazy audio

drivel in check. Don't give that up! Tom

Nousaine's "Urban Audio Legends"

ISSUE NO. 29 • SUMMER/FALL 2003 3

pdf 4

Page 5

comes close but does not have the "bite"

of "Hip Boots."

Maron Horonzak

Stoutsville, MO

Marrone, Maron! You never knew

that light could be measured in dB? Well,

it seems there are lots of things you never

knew, and this is one of them. A dB number can be just an expression of a ratio,

e.g., 20 dB is a ratio of 10 to 1, 10 dB is

a ratio of 3.16 to 1,3 dB is a ratio of l.41

to 1. Thus 3 dB too much red means 1.41

times as much red as there should be—

41 % too much. Your assumption that it's

Floyd Toole, Ph.D., who doesn't know

what he is talking about, rather than you,

reveals a lot about you.

Now, about Issue No. 28 not being as

good as some others, you may be right.

When there are three or more of anything,

one will be the best, one will be the least

good, and the other(s) will be in between.

That doesn't mean, however, that they

aren't all good. As for my total retirement

and letting Ivan Berger take over, it's a

staggeringly simplistic suggestion innocent

of all business/financial/professional/personal considerations. Didn't it occur to

you that it just might be more complicated

than that? lastly, "Hip Boots" is back in

this issue but, as explained there, not as a

continuing feature. Thanks for all your

concerns.

—Ed.

The Audio Critic:

I was truly delighted to find Issue

No. 28 in my mailbox yesterday. It is so

good to see that someone is still out

there battling the fakes and frauds. Peter, you are my hero. [Mutual admira-

tion society! See below.—Ed.]

It is most pleasing to see the excellent authors you have corralled and the

fine articles that you have published. In

your editorial you claim to be getting

old and tired. But cheer up. What you

are doing with The Audio Critic is such

excellent work that it must go on.

I have retired from the audio field after many years and am now, 10 years into

retirement, simply relaxing with my music and other hobbies. These are gardening, astronomy, and mineral collecting. Still, I think about audio matters

very often and still do a bit of consulting in room acoustics and audio systems.

I have taken the liberty of sending

you a couple of photos of my listening

room as it is now and has been for 22

years. I am still pleased with it and find

no reason to change anything. It is now

the music that counts for me.

Very best regards and best wishes for

future success.

Sincerely,

Dick Greiner

Madison, WI

Dr. R. A. Greiner is Emeritus Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Wisconsin, and one

of my heroes, as our regular readers know.

For quite a few decades before his retirement he embodied the academic community's most authoritative, and at the

same time most genial, voice on the sub-

ject of audio. Talk about "battling the

fakes and frauds"—he was at all times in

the font lines, patiently refuting charlatanry with irrefutable science. My admiration for him is unlimited, hence his frequent presence in this column. We may

not have anything near the circulation of

Stereophile, but could they ever, in a

million years, have elicited a letter like the

above from Dick Greiner?

As for your music system and listening room, Dick, should I be surprised

that you are not looking for a change?

What, only eight monstrous woofers? Only

24 visible smaller drivers? Only a dozen

electronic units? I have never seen a 1980

setup like yours, and very, very few 21st

century rigs like it. It really amuses me

when you say that only the music matters;

it's like a Rolls Royce owner saying that,

well, it's basic transportation. May you listen to that music in good health and spirits for many years to come—and thank

you for your compliments.

—Ed.

The Audio Critic:

Hello Peter, I have come to praise

you, not to bury you!

Item One: I received the latest issue

of The Audio Critic (No. 28) and immediately went to die "From the Editor"

column. Your explanation as to the reason for the disintegration of your relationship with The CM Group caught

my attention. Wanting to hear the other

side of the story, I placed a call to The

CM Group publisher, Greg Keilty . . .

... Greg had not read your explanation

as to what happened between you and

The CM Group, so I read your explanation to him (verbatim). Was I surprised at his response! He agreed with

you completely! To be completely honest (which is a much better form of honesty than partially honest!), I was expecting at least a minor disagreement

from Greg regarding your explanation.

There wasn't. Not only did he agree with

your explanation but spoke very highly

of

you!

Son of a

gun!

You get an A+ for

editorial integrity and my apology for

doubting your word. It's somewhat

humbling to admit I was wrong, but it

would be a mortal sin not to admit so

and apologize.

Item Two: I received the latest issue

of Invention & Technology magazine

(Fall 2002). Within this issue of the

magazine was an article (the cover story)

titled "The Tube Is Dead, Long Live the

Tube," written by Mark Wolverton. No

need to tell you that I couldn't wait to

read Mr. Wolverton's article. I was expecting more of the idiotic subjective

audio-cult gibberish printed as fact by

mainstream publications {Wall Street

Journal, Business Week, Fortune, to name

a few). Fortunately, this time, the

cultists were shown as believing (?) and

propagating myths based only on their

emotional or financial involvement

with tube equipment—something you

have been preaching for quite a while.

Much to my pleasant surprise, you and

David Rich were quoted regarding the

(continued on page 44)

4

THE AUDIO CRITIC

pdf 5

Page 6

By PETER ACZEL, Editor

Our Last

Column

How come? Because "wading through the mire of misinformation in the audio press" (our former subtitle) is no longer

meaningful when nearly the entire audio press is dedicated to

misinformation.

B

efore we stopped running our

"Hip Boots" column three issues

ago, its subject was almost invariably the ignorant and/or irresponsible

subjectivity of certain audio reviewers,

more often than not Bob Harley (ignorant) or John Atkinson (irresponsible) or

Harry Pearson (ignorant and irresponsible). Occasionally we addressed purely

technical errors in various publications,

sometimes even the mass media, that a

good fact checker could have corrected,

but most of the time our target was the

absence of accountability in one or the

other of the same three or four audio

magazines. That's where the mire lay that

only hip boots could wade through.

Lately the ground has shifted—or,

rather, it has expanded, spread out, in a

totally engulfing mode. We have reached

the point where virtually the entire audio press is in tacit denial of the realities

of electrical engineering and electroacoustics. All debate on the subject has

ceased. The false assumptions we used to

attack have become the self-evident

givens of the audio journalists. Fiction is

now accepted fact, mindless misinfor-

mation is unquestioned mainstream.

So—what's the point of singling out individual examples of this sad state of affairs? Whatever nonsense reviewer X

writes is echoed just as unthinkingly and

self-assuredly by reviewer Y and reviewer

Z. Why "hip boot" X but not Y or Z?

Do you think I'm overreacting or

exaggerating? Then tell me which

equipment reviewer refrains from ascribing a personality to amplifiers, preamplifiers, and CD players. They all do

it, except David Ranada, technical editor of Sound&Vision, the one magazine that is at least a partial exception

to the rule—but their other reviewers

are not as careful and tend to fall into

the trap of characterizing the sound of

electronic equipment.

For our newer readers I should perhaps point out all over again the pa-

thetic fallacy of talking about the

soundstaging, or front-to-back depth,

or open/closed quality, or graininess,

or any other sonic characteristic of

purely electronic signal paths that are

less than, say, 20 years old. What the

human ear can differentiate are fre-

quency response, level, noise, and to a

lesser extent distortion. That's all.

Since all modern audio components,

from a $15,000 rip-off amplifier to a

$69 portable CD player, have flat frequency response, negligible noise, and

negligible distortion, their sound has

no signature, no personality. Any two

of them—two amplifiers, two pre-

amps, two CD players, etc.—will

sound exactly the same, as long as their

levels are matched within ±0.15 dB. I

solemnly guarantee it. There has not

been a single properly conducted listening test—double blind, at matched

levels—to contradict that statement.

This will surprise only some of the

aforementioned newer readers and

elicit a chorus of denial from the more

obstinate of the high-end reviewers,

but it is an ironclad truth. Think about

it. There is no such thing as an effect

without a cause, and what could cause

a sonic difference except a skewed frequency response, a high noise floor, or

unusually high distortion? What you

are told in Stereophile, The Absolute

Sound, and other such publications is

ISSUE NO. 29 • SUMMER/FALL 2003 5

pdf 6

Page 7

6 THE AUDIO CRITIC

arbitrary effect without an explainable

cause—"Hip Boots" material over and

over again.

I'll grant maybe a rare exception to

the above in the case of the most eccentric "retro" vacuumtube designs, which

depart so radically from the flat/low

noise/lowdistortion model that, for all

I know (and I don't care), they sound different. The gullible are welcome to these

electronic abortions. I'll also grant that

matching levels within ±0.15 dB (preferably within ±0.1 dB) is a fussy, sweaty,

boring process, requiring some instrumentation, and for all those reasons not

done when it should be. That is un-

questionably the main nonideological

reason for all the stonewalling denials of

the soundalike outcomes. (Larry Klein,

former technical editor of Stereo Review,

Sound & Visions predecessor, once suggested a delightfully ironic solution to

this problem. He said you don't need

any instrumentation to match levels

within ±0.1 dB; all you need to do is fuss

with the volume controls until A and B

sound exactly alike, at which point the

levels will be perfectly matched. Bingo!

I love it!)

Let us also address the opposite end

of the spectrum, where there are always

large differences in sound—loudspeakers.

Every loudspeaker ever made is at least

slightly different in frequency response

from every other and therefore necessarily sounds different. Unfortunately, this

creates another likely "Hip Boots" situation. The various subjective equipment

reviewers have no clue as to how to relate the measured performance of a loudspeaker—if indeed they have measured

it—to its sound. Let us say it has rapidly

falling lowfrequency response below 60

Hz. In that case they would probably

praise its superior bass. Or it has almost

deadflat highfrequency response over a

large angle. In that case they would complain about its attenuated treble. If it has

a huge suckout in the crossover region at,

say, 1.8 kHz, they would praise the highly

accurate upper midrange. And so on. It

isn't just one or two reviewers that do

this. I look at the subjective highend

magazines and find absolutely no correlation between measured performance

and listening appraisal. Not that more

than one or two of them do any measuring at all, but I do and I can't find a single loudspeaker reviewer whose perceptions agree with mine and track my

measurements. (Tom Nousaine of

Sound & Vision is an exception, but he

doesn't count because he also writes for

The Audio Critic.) Since none of them do

an orderly, logical, disciplined job—like

Don Keele or David Rich or me in this

publication—what's the point of "hip

booting" one or two of them?

My conclusions from all this actually go beyond the futility of continuing "Hip Boots." I am beginning to

think that all comparative (A/B) listening tests have become unnecessary.

What? How can an audio equipment

reviewer possibly be saying this? Bear

with me for a moment. Since all mod-

ern electronic signal paths sound the

same, why go through the motions of

A/Bing them? I can guarantee that the

results will be the same over and over

again, and therefore the exercise is a

waste of time. (Don't misunderstand

me. I'm not suggesting that we stop lis-

tening to and enjoying music through

the various components. I'm talking

about A/Bing.) You can try it, as I have,

with a multikilobuck highend amplifier (A) and a dirtcheap Japanese mass

market receiver (B). You'll see.

But that's not all. I'll go further. Why

A/B loudspeakers? The flatter they are

in frequency response and the lower

they are in distortion, the more nearly

they will approach total neutrality, total transparency, which is both the goal

and the reference point. Conversely, the

more they deviate from flat and distortionfree response, the more they will

deviate from neutrality/transparency.

These relationships, as I have found out

over the years, are linear—the approximation of the ideal sound is exactly proportional to the degree of perfection obtained from the measurements. In other

words, there are no surprises in the listening tests—in which case why bother

with them? The only reason to do so is

that our measurements are incomplete;

we would need the 72 different meas-

urement points in a 4π space that Floyd

Toole uses at Harman International to

be sure that we have characterized each

speaker completely. If we had the laboratory facilities to do that, I wouldn't

A/B test anymore (although Floyd still

does). We have reached the point in audio where the laboratory instruments

know it all and tell it all, much as the

goldenear boys hate to admit it.

All of the above considerations are

made more complicated by surround

sound, which has its own rules. It is

not easy to understand that the audible

differences between Dolby Pro Logic

(I and II), Dolby Digital, DTS, Home

THX Cinema, 5.1, 6.1, 7.1, etc., etc.,

are not a matter of signal paths but of

algorithms. The differences are determined mathematically, not acoustically.

(There are also differences in bit rate between Dolby Digital and DTS, but

none that I consider to have audible

significance.) Listening tests, therefore,

are quite limited when it comes to sorting out the inherent audible characteristics of each configuration, because basically the sound is determined before

it reaches the amplifier/speaker stage. It

could actually be better studied from a

block diagram. Again, remember that

I'm talking about comparative listening,

not musical enjoyment.

In general, the paradigms have

shifted, journalistically, electroacousti

cally, psychoacoustically, every which

way. You can't take the old perspectives

for granted. We are well into the 21st

century. Or perhaps I should say, discomforting as it is, we aren't in Kansas

anymore.

pdf 7

Page 8

ISSUE NO. 29 • SUMMER/FALL 2003 7

By Ivan Berger, Guest Editor

D. B. Keele Jr., Contributing Editor

Tom Nousaine, Contributing Editor

Glenn O. Strauss, Contributing Editor

Five Loudspeakers (One a TimeHonored Exotic) and a Headphone

Definitive Technology, 11433 Cronridge

Drive, Owens Mills, MD 21117.

Voice: (800) 228-7148. Fax: (410) 363-

9998. E-mail: info@definitivetech.com.

Web: www.definitivetech.com. StudioMoni-

tor 450 shielded audio/video minimonitor

loudspeaker. $329.00 each ($658.00 the

pair). Tested samples on loan from the

manufacturer.

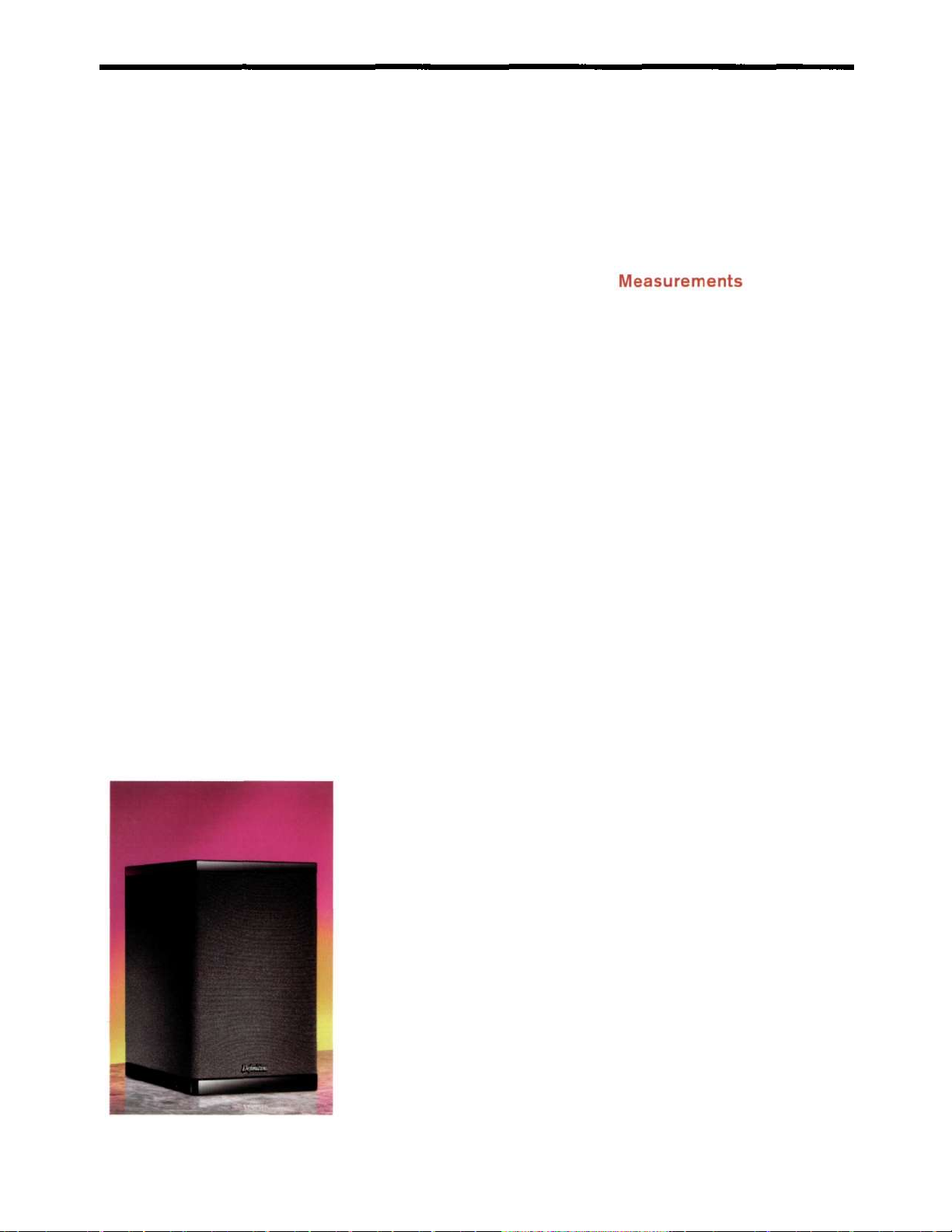

A 10-inch, side-mounted woofer in

a full-range speaker this small? Not

quite. It's something Definitive Technologies calls a "planar-technology pressure-driven subwoofer"—in other

words, a passive radiator (sometimes

called a PR, drone cone, auxiliary bass

radiator, or flapping baffle). Typically,

passive radiators substitute for vents,

or ports, in small speakers designed to

deliver substantial bass output. That's

a good description of the StudioMonitor 450, a member of Definitive Technologies' "Monitor Series" of modestly

priced home-theater loudspeakers.

Using a ported cabinet instead of

a closed box extends a speaker's lowfrequency response and reduces its

distortion. It does this by coupling an

acoustic resonant system (the enclosure and a port—usually a tube—that

vents its output into the room) to the

rear of the speaker's diaphragm. This

sets up an acoustic resonance between

the mass of air moving in the port

and the stiffness of the air in the enclosure. By matching the enclosure

and port sizes to the characteristics of

the driver, this resonator is typically

tuned to a frequency near the lowest

frequency the system is intended to

reproduce, and radiates low frequencies over a range of roughly two-thirds

of an octave around its resonance. If

the system is properly designed, far

more sound comes from the port

(within its operating range) than from

the driver. Because the ported enclosure's acoustic resonant system is typically more linear than the mechanical resonant system of the speaker, its

distortion is lower. Below its resonance, unfortunately, the port's output is essentially out of phase with

the loudspeaker's, which makes the

system's bass output roll off much

faster than that of an equivalent

closed-box system.

pdf 8

Page 9

There is, however, a catch to all

this: At high volume levels, the air in

the vent can move fast enough to generate significant turbulence, which

causes extraneous noise and limits the

port's output. This turbulence can be

tamed by increasing the port's area,

but that calls for lengthening the port

to increase the air mass within it. Otherwise, the box resonance, and hence

the shape of the speaker's response

curve, will change. For small boxes

that are tuned to low frequencies and

designed to radiate a lot of acoustic

power, enlarging the port's mouth

would call for very long port tubes

that take up a lot of space in the box;

sometimes, tubes that are long enough

won't fit!

Using a passive radiator sidesteps

these problems. Typically, a passive radiator is a speaker (frame, cone, surround, and sometimes spider) without

a magnet and voice coil. Here, the

ported-box resonance is a function of

the mass of the passive radiator and

the compliance of the air trapped in the

enclosure. Because it is shallow, the radiator can be made large enough to

avoid turbulence while taking up

hardly any space within the cabinet.

And because the radiator's mass is in-

dependent of its area, any size will do

as long as its air-moving capability (area

times stroke) is sufficient. A properly

designed passive radiator requires

roughly two to four times the air-moving capability (1.5 to 2 times the diameter) of its companion driver and

must have a self, or free-air, mechanical resonance at least an octave below

box resonance.

In Definitive Technology's compact, two-way StudioMonitor 450,

the companion driver to the 10-inch

passive radiator is a 6½-inch cone

woofer/midrange, used with a 1-inch

aluminum-dome tweeter. Both active

drivers are mounted on the front of

the cabinet, with the tweeter on top

and offset about an inch to one side.

The speakers are provided in mirrorimage pairs, with black, white, or

golden-cherry piano-gloss finishes on

the top and bottom. The front, sides,

and rear are covered in a wrap-around

grille cloth, held in place by the removable top and bottom pieces. Connection is through a single pair of

gold-plated multiway binding posts,

spaced for double banana plugs, on

the bottom rear of the cabinet. Cabinet construction is quite heavy-duty

for a speaker system of this size and

price: The medium-density fiberboard

(MDF) front panel is a full inch thick,

and the remaining panels are ¾-inch

MDF. The cabinet is well braced and

quite solid.

The magnetically shielded, 1-inch

aluminum-dome tweeter is essentially

the same as that used in Definitive

Technology's top-of-the-line systems.

The 6½-inch bass/midrange driver, also

magnetically shielded, has a cast basket.

The 10-inch passive radiator is simply

a rigid circular plate with an attached

surround.

The SM 450's crossover is wired

on a small PC board mounted near the

speaker's input cup and can be reached

by removing the cup. The crossover,

a second-order design, has an iron-

8 THE AUDIO CRITIC

core inductor connecting the

woofer/midrange, an air-core inductor

in the tweeter circuit, four power resistors, and three capacitors. That's

one more resistor and capacitor than

usual; the extra components probably

act as an impedance-compensating

network.

As in my previous reviews, I used

two different test techniques to measure frequency responses. I used nearfield

measurements to assess low-frequency

response, and measured response at

middle to high frequencies with win-

dowed in-room tests (my test microphone was centered between the

tweeter and woofer/midrange axes, 1

meter away). The test signal for these

measurements was the usual 2.83 V

rms, and the curves were subjected to

one-tenth-octave smoothing.

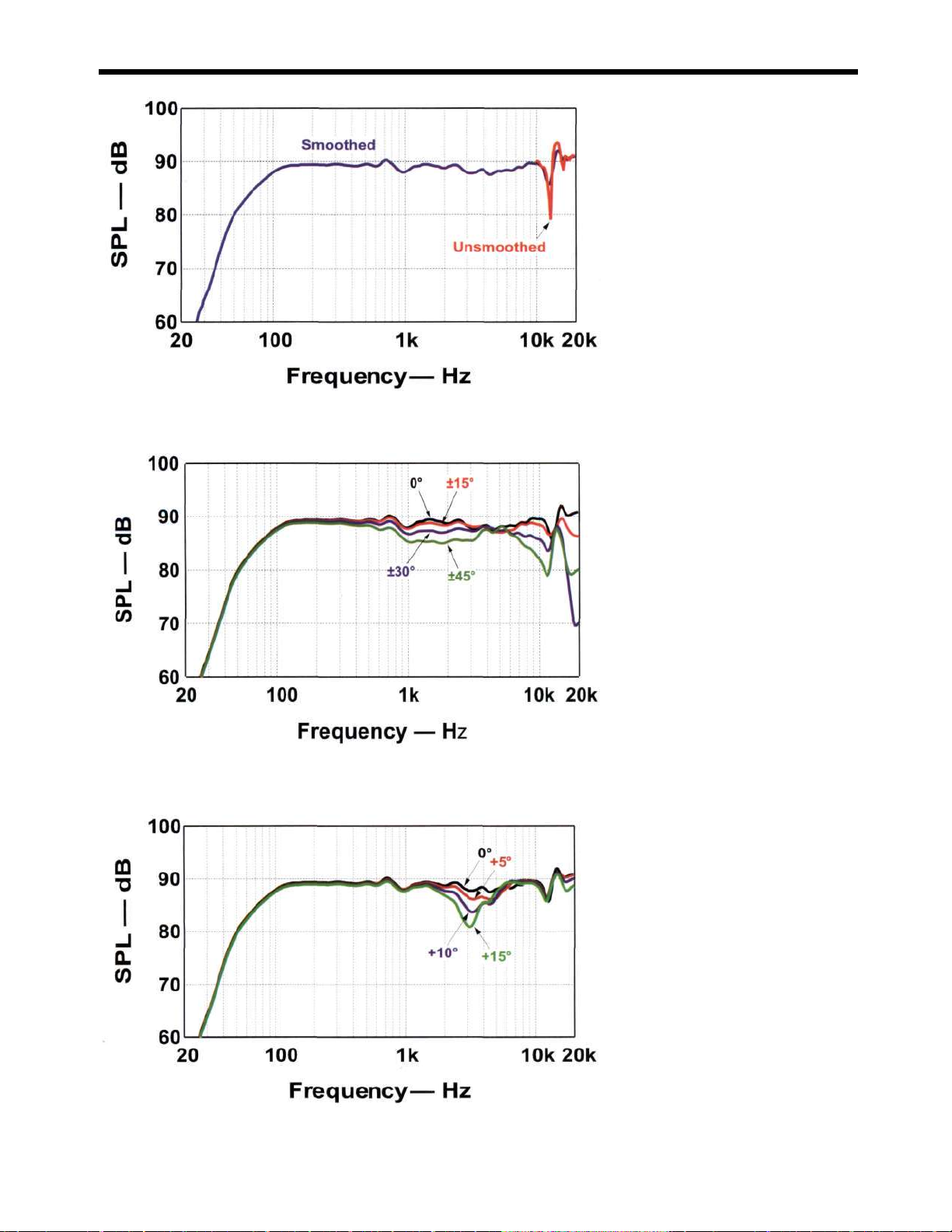

The on-axis response of the Studio

Monitor 450 is shown in Fig. 1, including smoothed and unsmoothed

responses above 10 kHz. Only the response with the grille on is shown, because the grille cloth is not designed to

be removed; fortunately, the grille had

essentially no effect on the SM 450's

response except for very small deviations of less than ±0.5 dB between 8

and 12 kHz. The smoothed curve is

quite well behaved and fits a tight (2.5dB) window from about 95 Hz to 12

kHz. At higher frequencies, the unsmoothed curve exhibits a sharp dip of

about 10 dB at 12.9 kHz followed by

a less energetic peak of about 4 dB at

14.5 kHz, both presumably caused by

a resonance in the tweeter's metal

dome. At low frequencies, the system

rolls off slowly, reaching -3 dB at 83

Hz, -6 dB at 63 Hz, and -9 dB at

about 50 Hz (which is near the SM

450's vented-box resonance). Below

50 Hz, the system rolls off rapidly,

about 24 dB per octave, as is common

with vented-box systems. However,

this curve was measured in free space,

pdf 9

Page 10

Fig. 3a: Frequency response above axis.

ISSUE NO. 29 • SUMMER/FALL 2003 9

Fig. 2: Horizontal off-axis frequency response.

Fig. 1: On-axis frequency response.

without reflecting surfaces to augment

the bass; in a room, reflections from

the walls would enhance the bass considerably. Averaged between 250 Hz

and 4 kHz, the SM 450's sensitivity

was high (89 dB), just 1 dB less than

Definitive Technology specifies. The

left and right speakers matched within

+ 1 dB, with most of the difference occurring in the tweeters' range.

The SM 450's horizontal and vertical off-axis frequency responses are

shown in Fig. 2 and 3. Fig. 2 shows

the horizontal off-axis curves, in 15°

increments out to ±45°. Between 1

and 3 kHz the response shelves downward, the dip worsening as the offaxis angle is increased. There are also

significant high-frequency aberrations

above 8 kHz at extreme off-axis angles. These aberrations include a dip

above 10 kHz, followed by a peak at

about 13 kHz.

That high-frequency dip and peak

are also seen in the responses measured

above and below the tweeter's axis. The

above-axis curves (Fig. 3a) are quite

well-behaved, except for a dip in the

3 kHz crossover region that deepens

progressively as the listening angle in-

creases, and the previously mentioned

aberrations above 10 kHz. Response

below axis (Fig. 3b) is significantly

smoother. Between 3.5 kHz and 7 kHz

the output below axis slightly exceeds

the on-axis output, which indicates that

the SM 450's response is smoothest a bit

below axis. This implies that these

speakers should be aimed above ear

level, or possibly be mounted upside

down to provide the smoothest re-

sponse for seated or standing listeners.

Luckily, the cabinet bottoms are fin-

ished like the tops, although there are

four small bumps that serve as feet. Un-

fortunately, the logos on front of the

speakers are upside down when the

speakers are inverted.

The input impedance magnitude

of the StudioMonitor 450 (Fig. 4a)

drops to a low of 3.2 ohms in the lower

pdf 10

Page 11

midrange (at about 200 Hz) and

reaches a high of about 14 ohms

slightly below crossover, at 1.6 kHz.

The two impedance peaks that mark

the 450 as a vented box are clearly evident; the impedance minimum (3.7

ohms at about 55 Hz) shows where the

box is tuned. The impedance phase

(Fig. 4b) is well behaved and varies

only moderately, about ±38°. The SM

450 should be an easy load for any

competent power amplifier or hometheater receiver.

To measure the distortion of the

450 (Figs. 5a and 5b), I used some software I recently wrote that works in conjunction with Igor Pro 4.0, a graphics

and data-analysis program (available for

Mac and PC from www.wavemetrics.com) and an external audio in-

terface with 24-bit A/D and D/A con-

verters, the Sound Devices USBPre

(www.sounddevices.com). In this setup,

test signals generated by Igor are fed

through the USBPre and my amplifier

to the 450s, while signals from my test

microphone are fed to the computer

through the USBPre, then analyzed and

plotted on graphs by Igor.

Fig. 5a shows the sine-wave harmonic distortion of the 450, evaluated

from 40 to 500 Hz at frequencies 1/12 octave apart. The distortion was evaluated

at each frequency by applying a sine

wave to the system for one half second

and then evaluating the harmonic distortion of the system's output, measuring the total energy of the 2nd

through 5th harmonics by using FFT

(Fast Fourier Transform) to compute

the frequency spectrum of that out-

put. (Results are expressed as a per-

centage of the fundamental's signal

level, not as a percentage of the total

output. Note that this calculation

method allows distortion levels above

100% if the energy of the harmonics

is greater than the energy of the fundamental.) The harmonic distortion at

each frequency was evaluated at three

different power levels, 6 dB apart. (The

10 THE AUDIO CRITIC

Fig. 4b: Impedance phase.

Fig. 4a: Impedance magnitude.

Fig. 3b: Frequency response below axis.

pdf 11

Page 12

Fig. 5b: Intermodulation distortion versus frequency and power level.

0 dB level was 2.5 V rms, or 25 watts

assuming a 4-ohm impedance.) Measurements were made with the speaker

on its side on the ground plane, passive

radiator facing up, and the test microphone at the ground plane, on the

woofer/midrange driver's axis and 0.25

meters away.

For frequencies above 125 Hz, the

harmonic distortion percentage stays

roughly constant and generally doubles when the input power does. Below 125 Hz, the distortion reaches a

maximum at about 70 Hz, falls to a

minimum between 50 and 55 Hz, and

then rises rapidly at lower frequencies. The dip in the vicinity of 50 Hz

coincides with the system's ventedbox tuning frequency, where the passive radiator is producing most of the

sound. (As you can see from the slight

shift in this dip when the power level

changes, box tuning varies slightly

with the test conditions; this is why

the impedance measurement, above,

indicates 55 Hz as the tuning frequency.) At the highest power level, 25

watts, the maximum distortion is a

When I first unpacked the Stu-

dioMonitor 450s, I was quite impressed

with their overall appearance, especially

the cabinets' piano-black top and bottom panels. At first, I could not figure

out how to get the grille cloth off so I

could see the drivers, but I soon determined that the top and bottom panels

could be removed, as they are attached

to the cabinet with four pegs that engage holes in the panels. When a panel

is removed, it uncovers the grille cloth,

which is tightened around the cabinet

with a captive drawstring. The grille

wraps completely around the cabinet

and has a cutout at the rear for the in-

put-terminal cup.

ISSUE NO. 29 • SUMMER/FALL 2003 11

moderate 16% or so, occurring at 70

Hz. At the power levels I used for this

test, the distortion did not become ir-

ritating until the test frequency

dropped below 45 Hz.

The SM 450 woofer's intermodulation distortion (IM) was measured

with the same power levels and test

conditions as in the harmonic distortion test but over a slightly different

range of frequencies. For this test, I

applied two tones of equal level, one

fixed at 440 Hz, the other varying

from 31.6 to 100 Hz in half-octave

steps. The dual-tone test signals were

applied to the speaker for one half second each. The test results, expressed

as a percentage of the energy of the

two original test tones, represent the

total energy of three intermodulation

sidebands above and three below the

higher test frequency. The IM (Fig.

5b) varies slightly over the tested frequency range and increases as the

power level increases. At the highest

test level (25 watts) the IM rises to

roughly 10% at the lowest test modulating frequency. While 10% harmonic distortion is not annoying,

10% IM distortion is. At power levels of-6 dB (5 watts) and less, the IM

remains below 3%.

Fig. 5a: Harmonic distortion versus frequency and power level.

pdf 12

Page 13

When uncovered, the speakers and

cabinet had a meticulous, no-nonsense look that showed careful craftsmanship and attention to detail. Under the grille cloth, the enclosure was

finished in an attractive satin black.

The SM 450s are provided with wallmounting brackets that screw into

routed-out holes on the rear panel—

a nice touch.

The large passive radiator essentially takes up one whole side of the

cabinet; in an enclosure this size, it

looks like a monster woofer. The ra-

diator is inset " to protect it from

damage. When energized by highlevel sine waves, the speaker sounded

quite clean down to 40 Hz, but distortion was audibly significant at

lower frequencies. At the box tuning

frequency, the woofer's motion almost

ceased and the passive radiator's excursion became quite large. The deep

null in the woofer's excursion showed

that the box and the passive radiator

work extremely well.

At and near the system's tuning

frequency, maximum clean excursion

was about 0.3" peak-to-peak for the

woofer and a healthy 0.4" peak-topeak for the passive radiator. The ef-

fective radiating diameter of the pas-

sive radiator is about 8.35" and that

of the woofer about 5". This makes

the drone cone's radiating area approximately 2.7 times that of the

woofer—and with its higher excursion capability, it can move roughly 3

to 3½ times as much air as the

woofer. As I said above, this is good

design practice for a passive-radiator

system.

For my listening, I placed the systems on 24" stands (which raised the

tweeter to about 34½" above the

floor) about 7 feet apart and well

away from room's side walls. I drove

them with my Crown Macro Reference power amplifier and Krell KRC

preamp. The SM 450s are smooth-

sounding speakers, and their sensitivity is quite high, especially as com-

pared to my reference B&W Matrix

801 Series 3 systems. In A/B comparison tests, I had to attenuate the

input to the Definitive Technology

speakers by about 4 to 4.5 dB to

match their levels to the B&Ws'. The

LED level monitors on my power amplifier showed that the amp was

working noticeably less hard when

driving the SM 450s. The Definitive

Technology speakers performed well

as long as the deep bass levels were

modest, but were no match for the

B&Ws in the low bass. Otherwise,

their overall balance was quite similar to the B&Ws'.

The SM 450s performed admirably on recordings with high peak

content, which profit from high playback levels—big-band material with

prominent brass sections and drum

rim shots, for example. With the peakexercising special effects on Ein

Straussfest (Telarc CD-80098—one of

my favorites, even though it dates

back to 1985!) I could actually get

slightly more volume from the Definitive Technology speakers than

from the B&Ws, because the latter's

lower sensitivity caused my amplifier

to clip before they reached the 450s'

maximum level. However, when I got

carried away with the volume control

on some of the Telarc CD's very loud

low-bass passages, I could overload

the 450s severely. The 450s' bass response was quite adequate on most of

the material I listened to. On shaped

tone bursts, bass response was quite

acceptable down to 50 Hz, with usable output at 40 Hz—but not at

lower frequencies. Teaming the 450s

up with a subwoofer improved the

sound significantly, putting the 450s

on a more equal footing with the

much larger 801s.

On well-recorded female vocals,

the 450s did exhibit some slight uppermidrange irregularities, but on highfrequency sibilants they did quite well,

reproducing them without harshness,

strain, or spittiness. After my lab tests

revealed high-frequency response aberrations caused by the tweeter resonance mentioned earlier, I listened to

the speakers again, but could hear no

problems caused by this. (Although

my hearing, at this point, is rolled off

in the range of this resonance, I sometimes can detect the subharmonics of

such resonances.) The 450s were the

full equal of the 801s on male speaking voices.

On the stand-up/sit-down pinknoise test, I heard moderate uppermidrange irregularities when I stood

up. With the speakers turned upside

down, the sound heard from a standing position matched the on-axis

sound more closely. I did perform sideby-side A/B mono listening comparisons between an upright and an upside-down speaker. Differences were

much less evident with music than

with pink noise.

The imaging and soundstaging of

the 450s were excellent. Mono center

images were quite stable and did not

shift when the recording's frequency

content changed. The 450s did extremely well on classical a cappella

choral music, reproducing the voices

and the room's reverberant sound with

great precision.

Considering their reasonable price,

good looks, and great sound, I highly

recommend the Definitive Technology StudioMonitor 450 speakers for

stereo use or for a home theater setup.

With a competent subwoofer, they

provide real competition for many

much larger systems. Their high sensitivity and smooth response will be

welcome in any music system.

—Don Keele

12

THE AUDIO CRITIC

pdf 13

Page 14

ISSUE NO. 29 • SUMMER/FALL 2003 13

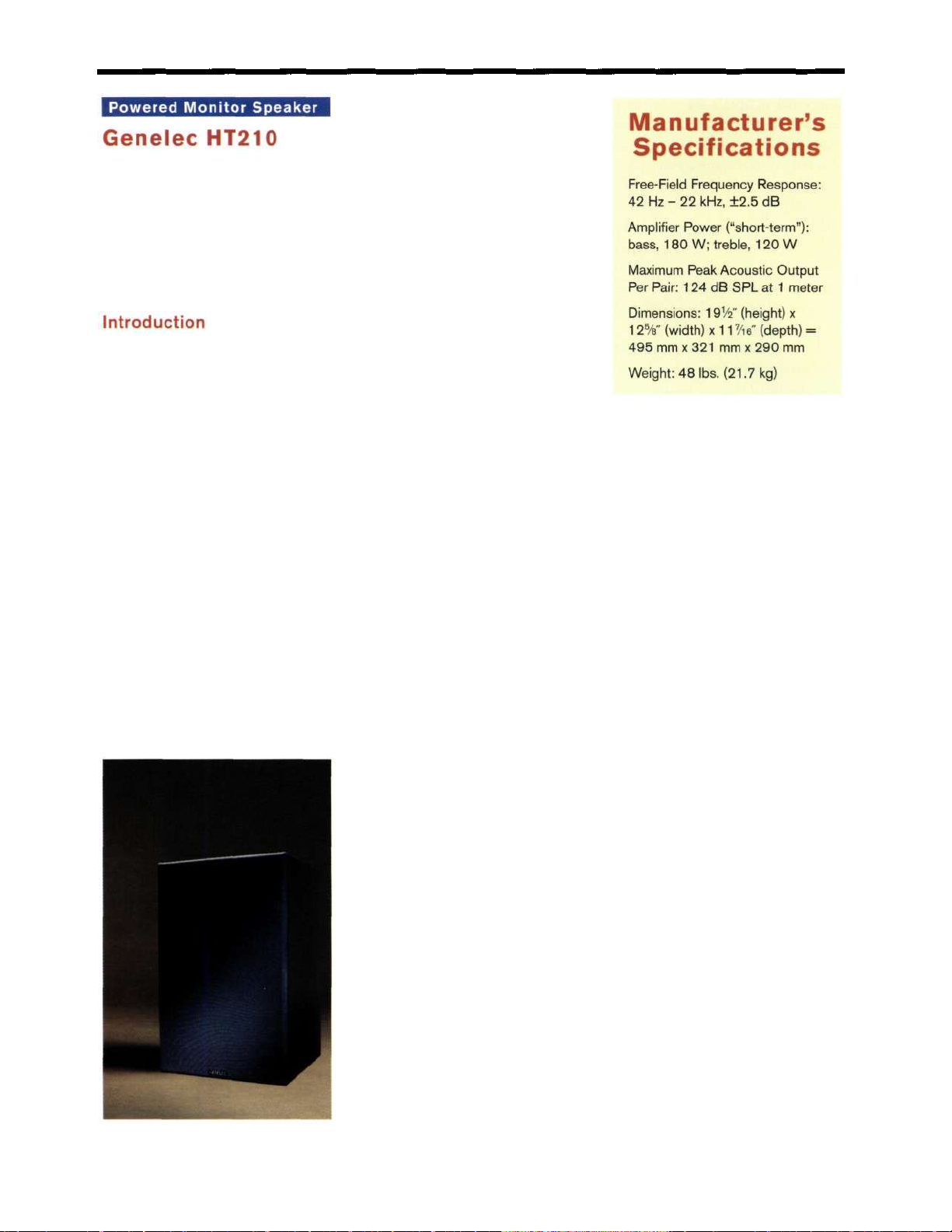

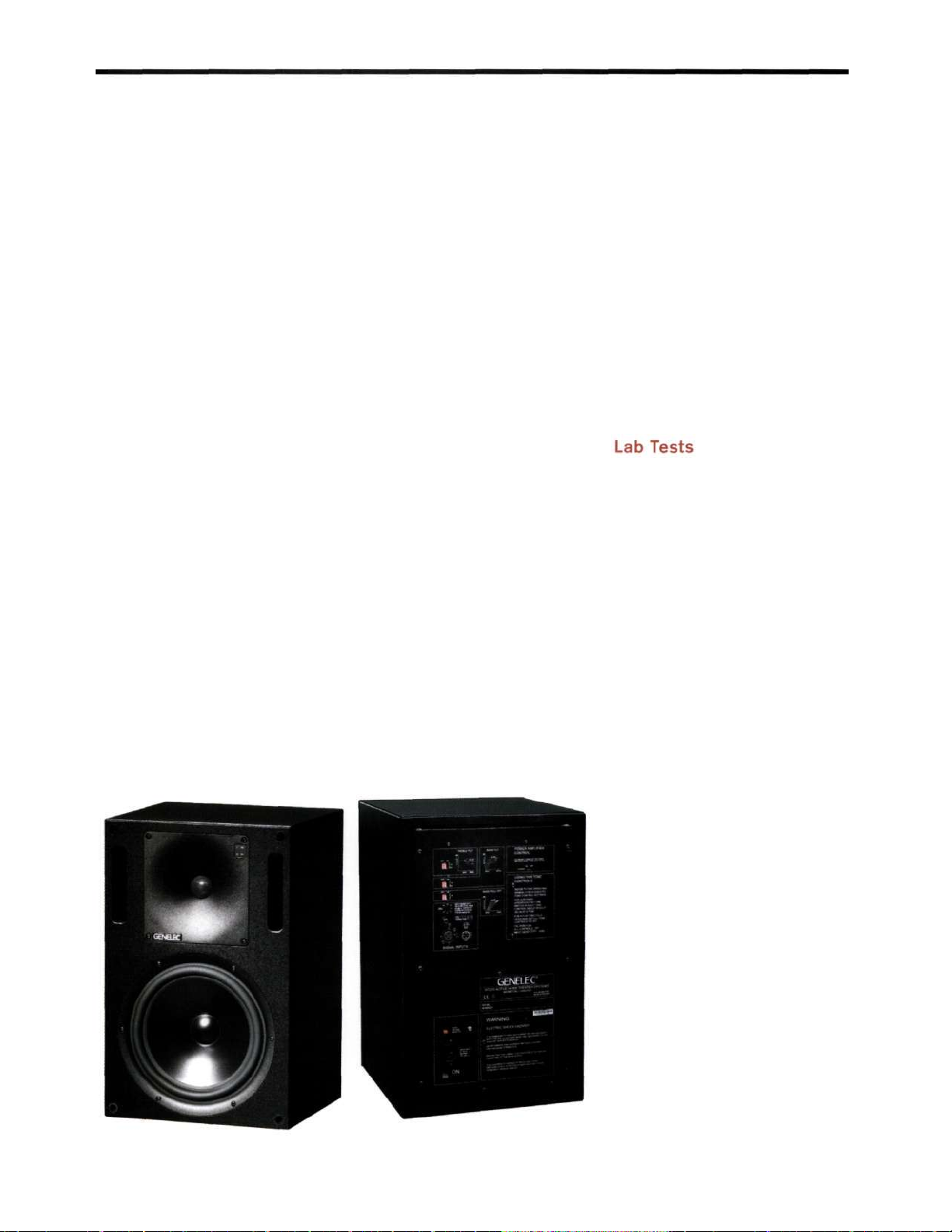

Genelec Inc., 7 Tech Circle, Natick, MA

01760. Voice: (508) 652-0900.

Fax: (508) 652-0909. E-mail:

genelec.usa@genelec.com. Web:

www.genelec.com. Model HT210 2-way

active loudspeaker, $2800.00 each in

black; other finishes optional. Tested sam-

ples on loan from manufacturer.

No audio component is perfect,

and speakers are the least perfect of all.

The imperfections of other compo-

nents can be too small for anyone to

hear, but speakers—all of them—have

readily audible deficiencies. The virtue

of "active," or powered, speakers is that

their electronics can make those de-

fects far less audible: Dedicated elec-

tronic equalizers can minimize the

speaker's frequency-response errors.

Built-in amplifiers can provide the ex-

act power that the speaker (or, better

yet, each driver) requires and, if each

driver is powered separately, precise ac-

tive crossovers can be employed instead

of cruder, passive ones. What's more,

protective circuitry can be custom-tai-

lored to the drivers it safeguards.

Despite their obvious potential for

improved performance and reliability, active loudspeakers have never

taken off in the home market, probably because most audio consumers already have receivers with a full complement of channel power, or even a

stack of amplifiers. Why buy power

again?

The complexity of modern audio

and home theater systems may change

that. In the days of stereo, all you

needed was a record player, a tuner, a

tape deck, a preamplifier, and a stereo

power amplifier, plus five shelves to

hold everything. Today, you might

have seven source components, a preamplifier, satellite receiver, and an

equalizer (well, I do). Who has rack

space for an additional seven or eight

channels' worth of amplifiers? I sure

don't.

So I use active speakers throughout my 7.1-channel reference system;

they perform better, conserve space,

and (because of their driver-matched

power levels and protective circuits)

let me leave my system in the hands

of a friend without coming home to

fried tweeters and the smell of melting voice-coil glue.

Genelec is a fairly new name in

the consumer market, but this Finnish

company's active speakers are highly

regarded and widely used in pro

sound, where active speakers have

long been common. Now, the company is angling for consumer sales,

with several series of active home-theater speakers. The HT210 is the larger

two-way speaker system in the Intimate Home Theater series (there's also

a three-way system), recommended

for rooms of 3,000 to 4,200 cubic

feet; other series are designed for

rooms of under 3,000, 5,000 to

10,000, and over 10,000 cubic feet.

The line also includes an in-wall

model and two subwoofers.

The HT210 has a 10-inch woofer,

which is unusual in a two-way speaker.

The primary reason you don't see

many 8-, 10-, or 12-inch two-way designs is that the directivity of large

drivers narrows rapidly as they reach

the crossover point, which is also the

frequency where a tweeter's directivity is widest. Passive crossovers can

have little or no influence on directivity, especially while retaining

smooth response off axis. Better-performing satellites use 6- or 6½-inch

woofers at most, because such drivers

are the largest ones capable of offering

both a reasonable low-frequency extension and a woofer directivity that

closely matches the tweeter's near the

crossover (1.8 kHz). With electronic

crossovers the designer can play a few

little trade-off games regarding directivity; in the case of the HT210, however, the excellent directivity over the

entire operating range from 42 Hz to

22 kHz, despite the comparatively

large woofer, appears to be due to the

shallow, hornlike "Directivity Control Waveguide" surrounding the

tweeter.

The HT210 has two internal amplifiers: a woofer amp with a "shortterm" power rating of 180 watts, and

a tweeter amp with a 120-watt "shortterm" output rating. Genelec doesn't

say what the hell "short-term" watts

are, but who cares? Amplifier power

ratings for active speakers (powered

subwoofers included) have no signif-

pdf 14

Page 15

14 THE AUDIO CRITIC

icance. We need to know how much

energy comes out of the speaker, not

how much energy goes in to produce

that output. (Of course, if manufac-

turer X gets 120 dB SPL with a 2,000-

watt amplifier and manufacturer Y

does it with 20 watts, I might prefer

the latter because it's easier on my

electric bill.) What is significant is

that Genelec specifies peak output for

a pair of HT210s as 124 dB SPL at 1

meter with "music material."

Unlike the controls on passive

speakers, the Bass Tilt, Bass Roll-Off,

and Treble Tilt controls in the

HT210's electronics work almost exactly as specified, even at low frequencies. An "Autostart" function

turns the unit off if no signal has been

present for 5 minutes, but restarts it

immediately when a new signal is received. Additional controls on the rear

panel (wouldn't remote controls be

cool?) include an on-off switch, a

110/220-volt mains selector, XLR and

RCA input jacks, and a rotary control

for matching input sensitivity to the

output levels of upstream components. Units currently in production

have two additional features: a set of

contacts for on-off switching using

12-volt trigger signals, and switches

that control the LED indicators.

(Users will be able to select whether

the LEDs remain off, show only yellow for standby and green for operation, or also show red for overload.)

The speaker is magnetically shielded,

so you can use it near a TV set or

other cathode-ray tube (CRT) display.

The HT210 is relatively large for

a satellite speaker. (With its bass response specified as -2.5 dB at 42 Hz,

the HT210 could conceivably be

used without a subwoofer, but I think

few would use it that way.) Although

it has a small, 1-foot-square footprint, the cabinet occupies 2.8 cubic

feet of space in a listening room, and

its 48-lb. weight means that you

won't be hoisting these speakers off

their stands with one hand while

dusting with the other. The MDF

cabinet of my samples had a flat black

pro-style finish, and lacked the optional ($79) grilles. In speakers selling for $5,600 a pair, the utility

finish and the extra charge for grilles

were disappointing. However,

HT210s are now available in glossy

piano black and three wood-veneer

finishes, all complete with grilles

(prices not established at press time).

As I did not have the grilles, I could

not measure what effect, if any, they'd

have on the sound.

The tweeter waveguide plate can

be removed and rotated 90° so the

Genelec logo will be upright if you

mount the speaker horizontally. The

electronics panel on the rear is resiliently mounted, a pro-sound carryover that protects the system against

rough handling on tour. The enclosure

seems relatively tourproof, too: when I

accidentally knocked the HT210 off

my measurement stand, the 6-foot

drop left only a -by-2½-inch gouge

on the rear corner of the cabinet and

did not affect the speaker's operation.

How did the Genelec HT210 measure up? Let's discuss how it performed

in the lab first. Basic measurements

were taken at 2 meters in my large,

7,600-cubic-foot, room; maximum

output for a stereo-arrayed pair was

measured at 4 meters in the same room.

All measurements were taken with a

DRA Laboratories MLSSA acoustic an-

alyzer and an AudioControl SA-3050A

third-octave real-time analyzer and

sound-level meter.

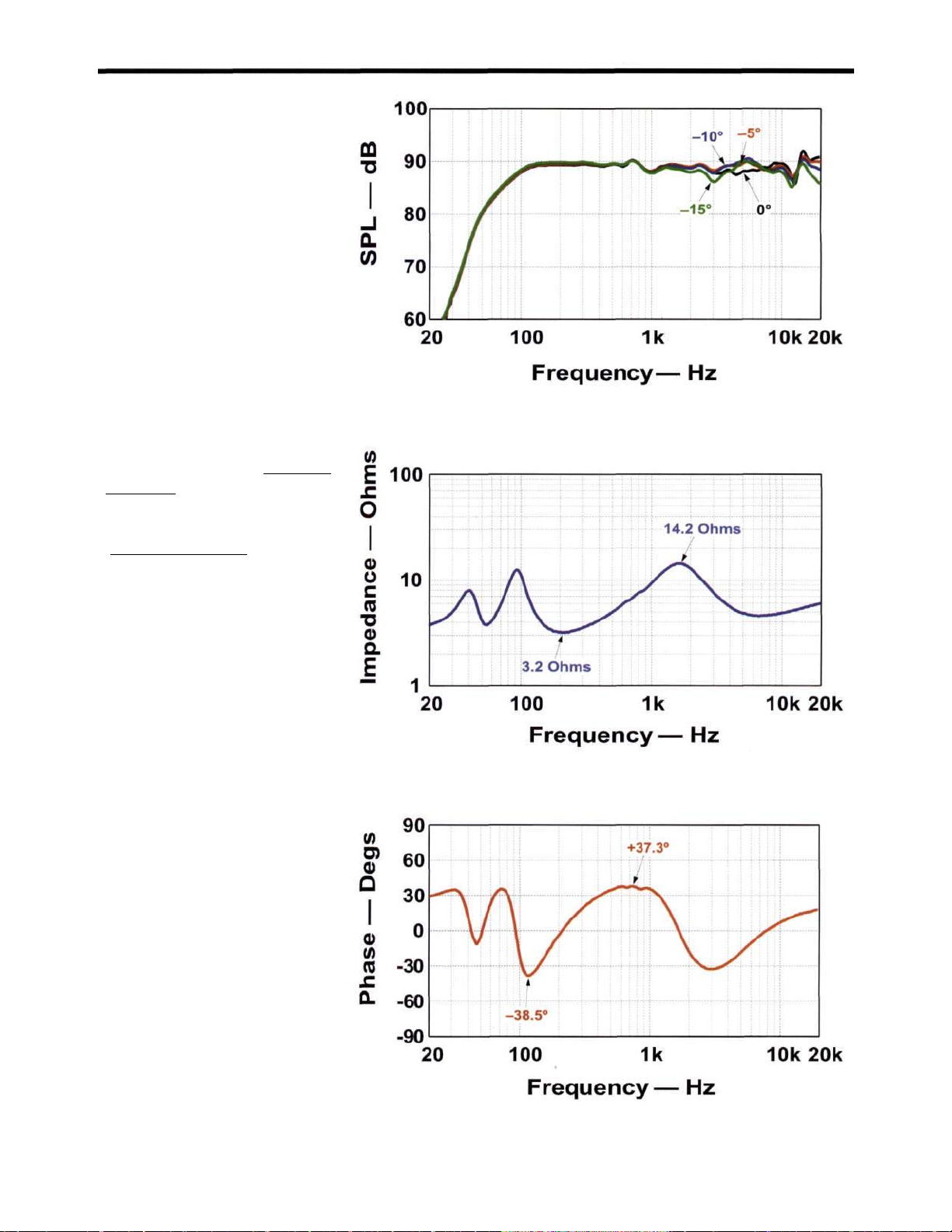

The horizontal response graph

(Fig. 1) shows that the HT210 is in-

credibly smooth out to 60° off axis.

Directly on axis, its response fits in

a ±3 dB window from 55 Hz to

20 kHz, shelved up by approximately

2 dB between 1 and 10 kHz. Horizontal directivity is remarkably smooth

and wide. This is not due to some kind

of electronic trickery; there is no suggestion to that effect in Genelec's specs

and literature. As it is most unusual for

a 10-inch two-way system to work this

well off axis, the explanation probably

lies, as I suggested earlier, in the shallow, hornlike baffle ("Directivity Control Waveguide") of the tweeter.

Vertical radiation patterns (Fig.

2a/b) are less uniform. Below the axis,

there's a sharp, deep notch at 1.6 kHz,

followed by irregularities at greater ra-

pdf 15

Page 16

Fig. 1: Horizontal on- and off-axis frequency responses.

diating angles. Above-axis response is

smooth to about 20°, with notching

near the crossover frequency as the angle increases. (These problems are com-

mon when multiway speakers have

drivers placed side by side or when vertically arrayed systems are used hori-

zontally. I beg people with multiple lis-

tening seats to use a vertically arrayed

center channel.) The HT210 should be

used vertically whenever possible, and

when used for a center channel should

preferably be placed below the screen.

The response alterations imposed

by the Bass Roll-Off and Bass Tilt

switches followed almost exactly the

curves printed in the manual and on the

electronics panel on the back of the enclosure, although the magnitude of action was only about 65% of that indicated. For example, the DIP switch for

Bass Roll-Off (a highpass filter whose

slope increases from 6 to 12 dB per octave in small steps) indicates cuts of 2,

4, 6, and 8 dB for frequencies below

100 Hz, but setting the switch at -8 dB

only cut response by only a little more

than 5 dB. Likewise, the Bass Tilt

switch (which should cut 2, 4, or 6 dB

below 1 kHz, depending upon its setting) produced a 4 dB reduction when

set in the -6 dB position.

On the other hand, the action of the

Treble Tilt switch, which cuts in at

about 8 kHz and was indicated as +2,

-2 and -4 dB at 15 kHz, matched the

printed graphs exactly. The tweeter and

woofer can be turned off individually

when the Mute position on the driver's

DIP switch is selected—while this is a

fantastic feature for nearfield measuring

it is of no use I can think of for home

listening.

For a two-way satellite, the

HT210 delivered a healthy output,

though not quite as healthy as suggested by Genelec's specification (124

dB peak per pair at 1 meter, with music). Using the most challenging

recordings I have, I got the HT210s

to crank out a clean 102 dB SPL peak

Fig. 2b: Vertical off-axis frequency response above axis.

Fig. 2a: Vertical off-axis frequency response below axis.

ISSUE NO. 29 • SUMMER/FALL 2003 15

pdf 16

Page 17

(no audible amplifier clipping, lim-

iter action or speaker distress) at 4

meters in my large room, which translates to 114 dB at 1 meter. Turning the

gain up from the default setting (-6

dBu) to its maximum (+4 dBu) enabled the speakers to deliver 105 dB

SPL at 4 meters; however, limiter action and/or amplifier clipping was

clearly evident at sound pressure levels above 102 dB; this surprised me,

as most active speakers will not allow

themselves to be driven into overload.

The HT210's low-frequency abilities were similar to those of many "fullrange" floor-standing loudspeakers I've

used. Speakers seldom have the lowfrequency dynamic capability that reference measurement levels imply. Frequently, full-range models whose

measured low-frequency extension

seems impressive exhibit an upward

spectral balance shift at high output.

This shift occurs because the low-fre-

quency driver lacks the displacement

to keep up with the mid/tweeters; the

highs keep getting louder while the lows

stall out as the system's output level increases.

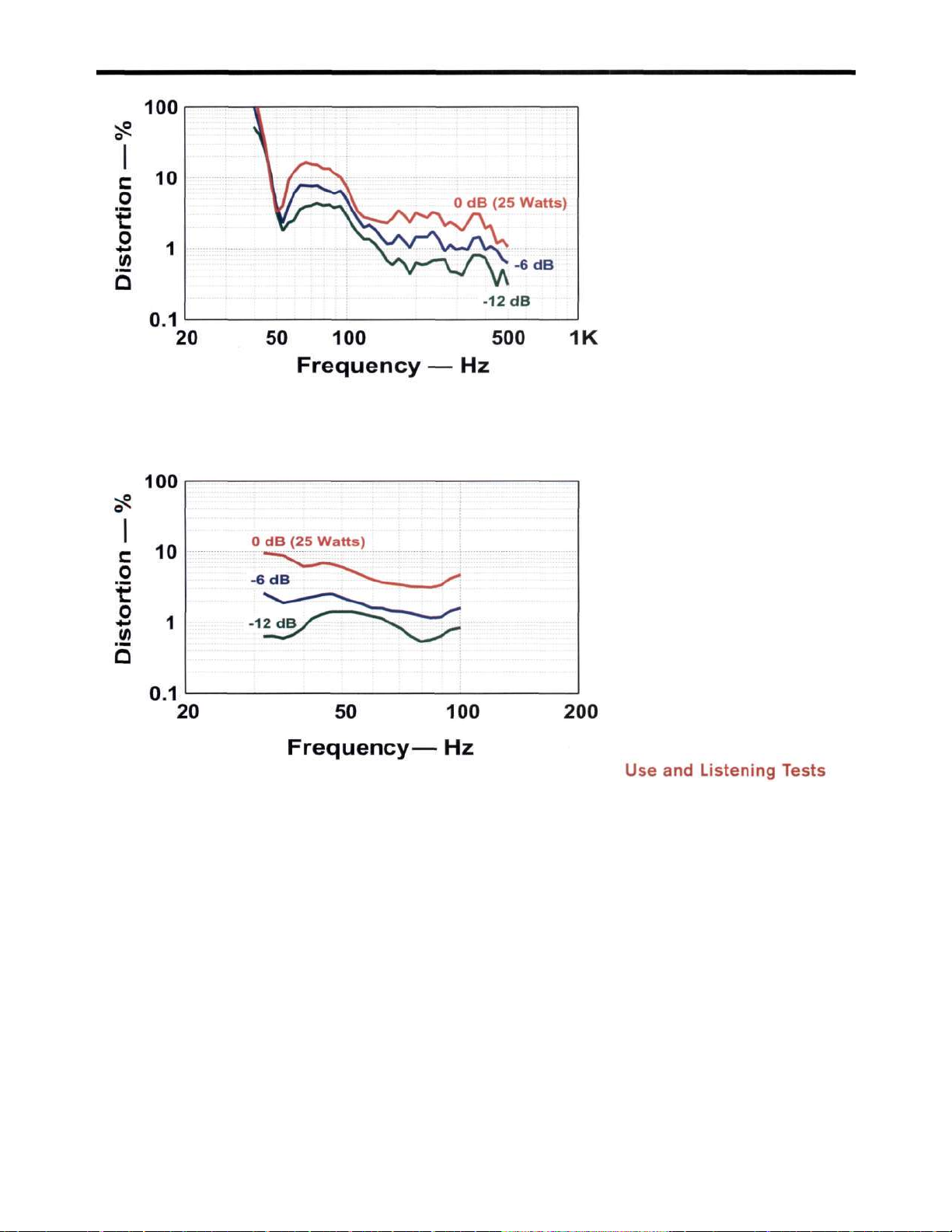

To measure the Genelec's low-frequency abilities, I used a technique

adopted from Don Keele: I fed the

speaker ramped, 6.5-cycle tone bursts at

-octave frequencies, and used a

MLSSA acoustical measurement system

to determine the maximum low-frequency SPL the speaker could deliver at

2 meters (a truly practical listening distance) before distortion reached 10%

or overload protection cut in. While a

distortion figure of 10% seems quite

high, a speaker still sounds clean at that

level. This is because the speaker is just

leaving its linear output range at that

point; as the level increases further, distortion will begin increasing exponentially. (Technically, this happens when

the driver's motor BL product, a measurement of magnetic field strength, has

fallen to 70% of its rest-position value,

or when the suspension has stiffened by

I listened to the HT210 as a stereo

pair. The sound was clean and clear, al-

though somewhat aggressive. With the

Treble Tilt switch set to 0 dB, there

was excessive sibilance when playing

Suzanne Vega's recording of "Tom's

Diner" (on Solitude Standing) and per-

cussion sounded somewhat overemphasized. When I set the Treble Tilt

switch to -4 dB, however, voices and

acoustic instruments were rendered

with natural timbre and excellent de-

tail and clarity, although the speaker

still sounded slightly aggressive.

The Genelecs delivered a wide,

moderately deep soundstage, with excellent image placement and separation. The wide, smooth radiation pattern provided an excellent sense of

ambience, positioned images outboard

of the left/right speaker pair, and

clearly rendered reverb and ambient

effects in the mix. Center images followed me when I moved off axis; this

is normal for two-channel systems, and

the Genelecs do a better job of distributing ambience and retaining far

left/right images than speakers typically do in stereo setups. I believe the

HT210 can be successfully used as a

left/right, center, or surround speaker

in a multichannel system.

The Genelec HT210 will reward

any listener with high-quality, highoutput playback in mono, stereo, and

multichannel music and film systems.

It has more output capability than any

other two-way home system I've ever

used, and more than many 12-inch

towers. As a satellite speaker, it's a little on the large side. As a full-range

speaker, it's moderate in size but with

the impact of many larger floor-standing systems. Like all satellite and most

full-range systems it will benefit from

a subwoofer if you like high-impact

low-frequency programs.

Some people will consider the

Genelec HT210s pricey (a 5-channel

system would run you about $14,000)

Others, though will see them as a bargain, considering current speakerprice trends and the fact that a full set

of high-performance electronics with

useful precision operating controls is

included in the deal. As far as I'm

concerned, these Genelecs would be

welcome in my house anytime.

—Tom Nousaine

16 THE AUDIO CRITIC

a factor of four.) I define a speaker's bass

limit as the lowest frequency and highest SPL it can deliver within the 10%

distortion threshold. For a single

HT210, the bass limit was 75 dB SPL

at 40 Hz at 2 meters.

Surprisingly few two-way satellites

(or even full-range speakers) can deliver

such usable output at 40 Hz. However,

the HT210's usable output at 40 Hz

was nearly 25 dB below its maximum

clean output at higher frequencies,

which occasionally caused the spectral

balance shift described previously. If

you want full-bandwidth dynamic capability, you'll need to use the Genelec

with a subwoofer.

Dynamically, the HT210 plays

damn loud, yet retains its clarity when

the music gets soft or is simply played

softly. There is some, but less than

usual, upward spectral shift when

playing full-range recordings at very

loud levels. When played at full gain

with ultraloud, dynamic, or ultracompressed program material (Radiohead's Amnesiac, Fugees' Blunted

on Reality, Jay Leonhart's Salamander Pie) the HT210 could play

roughly 3 dB beyond its clean limit.

At such high levels, the Genelec's limiters keep turning on and off and the

sound is sometimes grossly distorted.

(I used hearing protection when

checking this.) But when you're finished abusing the speaker, there will

be no burned or bottomed voice coils,

and the system will play as if it were

still new.

pdf 17

Page 18

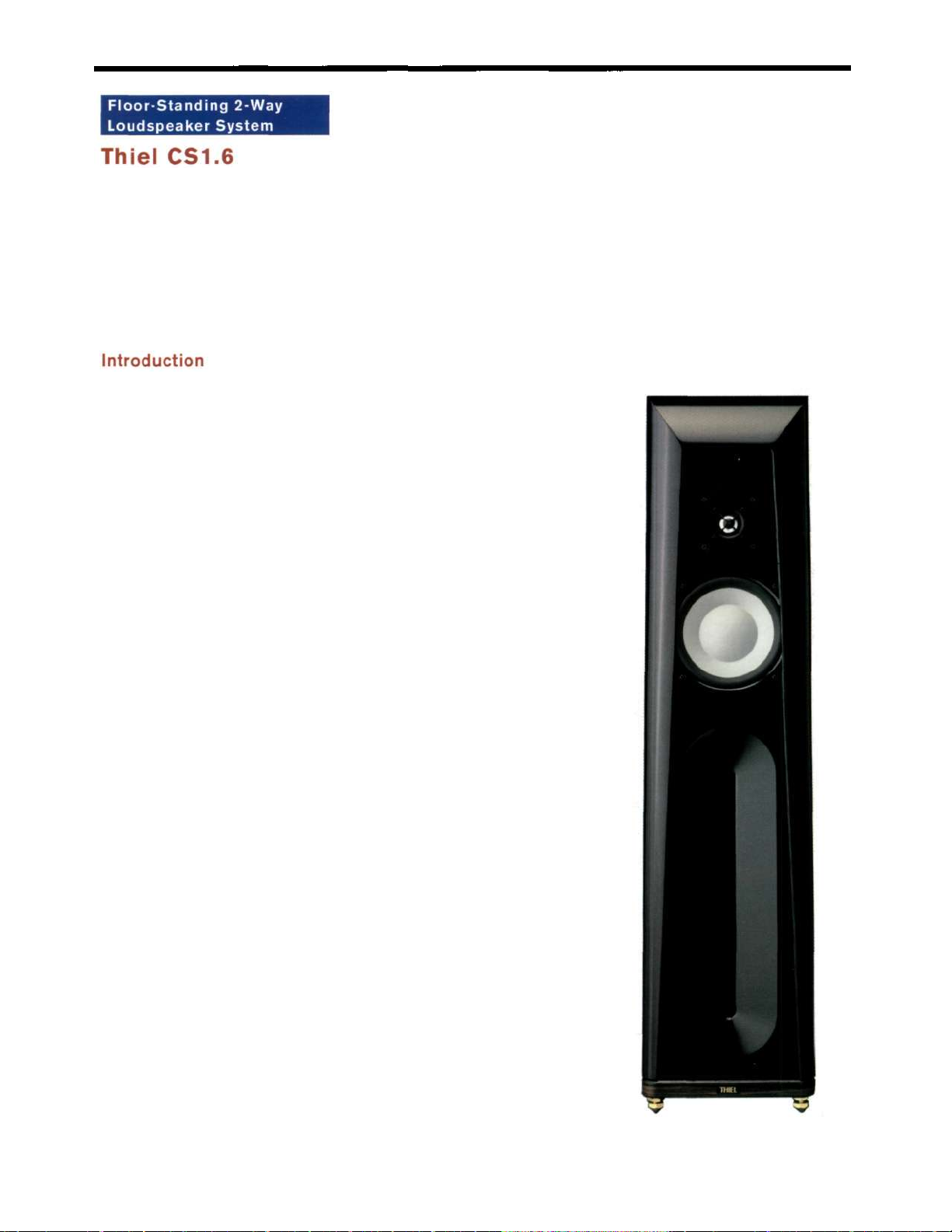

Thiel Audio, 1026 Nandino Boulevard, Lexington, KY 40511-1207. Voice: (859) 254-

9427. Fax: (859) 254-0075. E-mail:

mail@thielaudio.com. Web: www.thielaudio.com. Model CS1.6 coherent source

loudspeaker, $2390.00 per pair in black

ash, cherry, maple, oak, or walnut

($1990.00 the pair painted black). Tested

samples on loan from manufacturer.

The CS1.6 shares the distinctive

look of Kentucky-based Thiel Audio's

other floor-standing speakers: a finely

finished cabinet with a raked-back,

rounded, black front panel. That look

is part of Thiel's "Coherent Source"

design, which, the company says, aims

to eliminate "time and phase distortions that cause alterations in the reproduced musical waveforms of most

loudspeakers." Raking the front panel

moves the tweeter farther from the listener, so its output will arrive at the

same time as the woofer's. The front

panel is claimed to reduce parasitic resonances, and its rounded corners minimize diffraction. Thiel also uses widebandwidth drivers and true, first-order

crossovers to maintain phase coher-

ence. The result, says Thiel, is enhanced

realism, clarity, transparency and im-

mediacy, as well as improved imaging

and a deeper soundstage.

The CS1.6, the second smallest of

Thiel's six CS-series speakers, is a twoway bass reflex system with anodized

aluminum diaphragms on both drivers.

The woofer's construction is unusual. Instead of placing a small voice

coil at the apex of a deep woofer cone,

Thiel gave the CS1.6's woofer a large

(3-inch) coil attached about midway

between the cone's outer surround and

its center. This design distributes the

driving force over a larger area and, by

reducing the unsupported span between the coil and the cone's edge, re-

duces cone breakup. According to

Thiel, it also moves the diaphragm's

spurious resonances to a much higher

frequency, and hence raises the driver's

high-frequency cutoff.

As a result of this driving system, the

woofer's cone is quite shallow and its

dustcap is distinctively large. The large

voice coil enables Thiel to place the

neodymium magnet inside the pole

piece rather than outside it. This topology provides magnetic shielding; when

I set a CS1.6 right next to my computer's monitor, it caused no color dis-

tortion of any kind.

The woofer's extended response is a

necessity, because of the CS1.6's firstorder crossover. The virtues claimed for

first-order crossovers, which have gentle slopes of 6 dB per octave, are simple construction (typically, one capac-

itor and one inductor) and "phase

coherence" (the elimination of phase

changes at the crossover frequency).

The theory is that a first-order crossover

keeps the two drivers in quadrature (90°

apart) at all frequencies, and conse-

quently the sum of the two drivers'

acoustic outputs is theoretically a perfect replica of the crossover's input. The

importance of this from the standpoint

of audibility has long been debated and

belongs in another discussion.

It's not enough for a first-order

speaker system to have crossovers with

6-dB/octave slopes. It's also necessary

to have loudspeaker drivers that operate cleanly for two to three octaves

beyond the crossover point. This is

because moving-coil drivers are second-order devices, which roll off at

12 dB per octave outside their natural passband. Only very wideband

drivers allow the system's roll-off to

start well before the drivers'. A firstorder crossover's gentle slope also does

little to suppress any irregularities in

the driver's response outside its passband. So using such drivers not only

requires an extended upper range for

the woofer, but also a downward ex-

ISSUE NO. 29 • SUMMER/FALL 2003 17

tension of the tweeter's response. Thiel

says quite a bit about technologies

that extend the response of the

CSl.6's woofer upward, but nothing

about the low end of the tweeter's response. Nonetheless, I neither heard

nor measured any of the anomalies I'd

expect if the tweeter lacked low-end

response or had insufficient power

handling at low frequencies.

Despite the appealing simplicity of

basic first-order filter design, it often

pdf 18

Page 19

takes sophisticated networks to maintain a true first-order response several

octaves above and below the crossover

frequency. Thiel's literature says that

the company's speakers "make extensive use of network compensation. Typically, about 40% of the network elements are used to achieve correction of

what would otherwise be minor response irregularities."

The CS1.6 has an unusual bass-reflex port: a half-inch-wide, 12-inchlong slot exiting through a beveled recess on the front panel. The recess flares

outward rapidly to a width of 4½ inches

at the panel's front surface. Thiel says

this design reduces unwanted port

noise, and my experience with the

speaker backs that up.

According to the company, the port

design also reduces "grille loading effects," and—hallelujah!—the grille had

virtually no effect on the sound of the

CS1.6. However, that may have more

to do with the grille's design than the

port's. The grille is a fabric-wrapped

sheet of ultra-thin steel, 80% perforated. Magnets hidden beneath the

cabinet surface hold the grille to the

front baffle, eliminating grille frames

and other constructions that could affect response. That baffle, by the way,

is 2 inches thick, and the other enclosure panels are an inch thick, stiffening

the cabinet and minimizing secondary

radiation.

The cabinet is not only stiff but

beautifully finished, something Thiel

is known for. Buyers have their choice

of 15 fine cabinet finishes, at several

price levels. In the standard finishes

(ash, black ash, cherry, maple, oak, and

walnut veneers), the speakers are $2390

per pair. More exotic finishes (such as

ebony, dark cherry, mahogany, teak,

and zebra wood) are available at prices

up to $2865 per pair. At the other end

of the scale, a pair of CS1.6s in plain

black paint is $1990. Custom finishes

are also available. My test sample was

finished on three sides and the top in

amberwood, an aggressively grained

walnut ($2565 per pair); the front baffle and bottom were black.

The CS1.6 comes with four

threaded and pointed feet, which can be

used to steady the cabinet on a thick

carpet and to control the tilt of the front

baffle. An optional outrigger base is also

available ($200 per pair) for added stability on deep-pile carpets or in homes

with active small children or large dogs.

Connections are made via heavy-

duty multiway binding posts on the rear

panel. They are not on ¾-inch centers,

so they won't accept double banana

plugs, but single banana plugs work fine.

(By the way, you can easily convert a

dual banana plug into a pair of singles

with diagonal cutters.) There is only one

pair of connecting posts per speaker, because Thiel doesn't believe biamping or

biwiring are necessary (neither do I). But

the company also says that it does not use

separate woofer and tweeter connections

because the strap needed to bridge die

two together for use with just one amp

would be "sonically compromised;" that

just plays to existing audiophile myths.

Warranty is 10 years to the original

owners for any defects in material and

workmanship.

My basic measurements of die Thiel

CS1.6 were quasi-anechoic, taken at a

distance of 2 meters in a 7,600-cubicfoot room, combined with near-field

measurements for the low frequencies.

All measurements were taken with a

DRA Laboratories MLSSA acoustic analyzer with calibrated microphone and

an AudioControl SA-3050A third-oc-

tave real-time analyzer and sound-level

meter. I also supplemented the quasianechoic measurements with 2-meter

readings taken with the speaker standing on a carpeted floor to replicate normal use. In my opinion, measurements

of performance on a floor should always be used when designing and eval-

uating a tower speaker, because its proximity to the floor will affect its response

in any listening room. (Floors also affect the response of stand- or shelfmounted speakers, but the effects will

vary with the height at which the

speaker is mounted.)

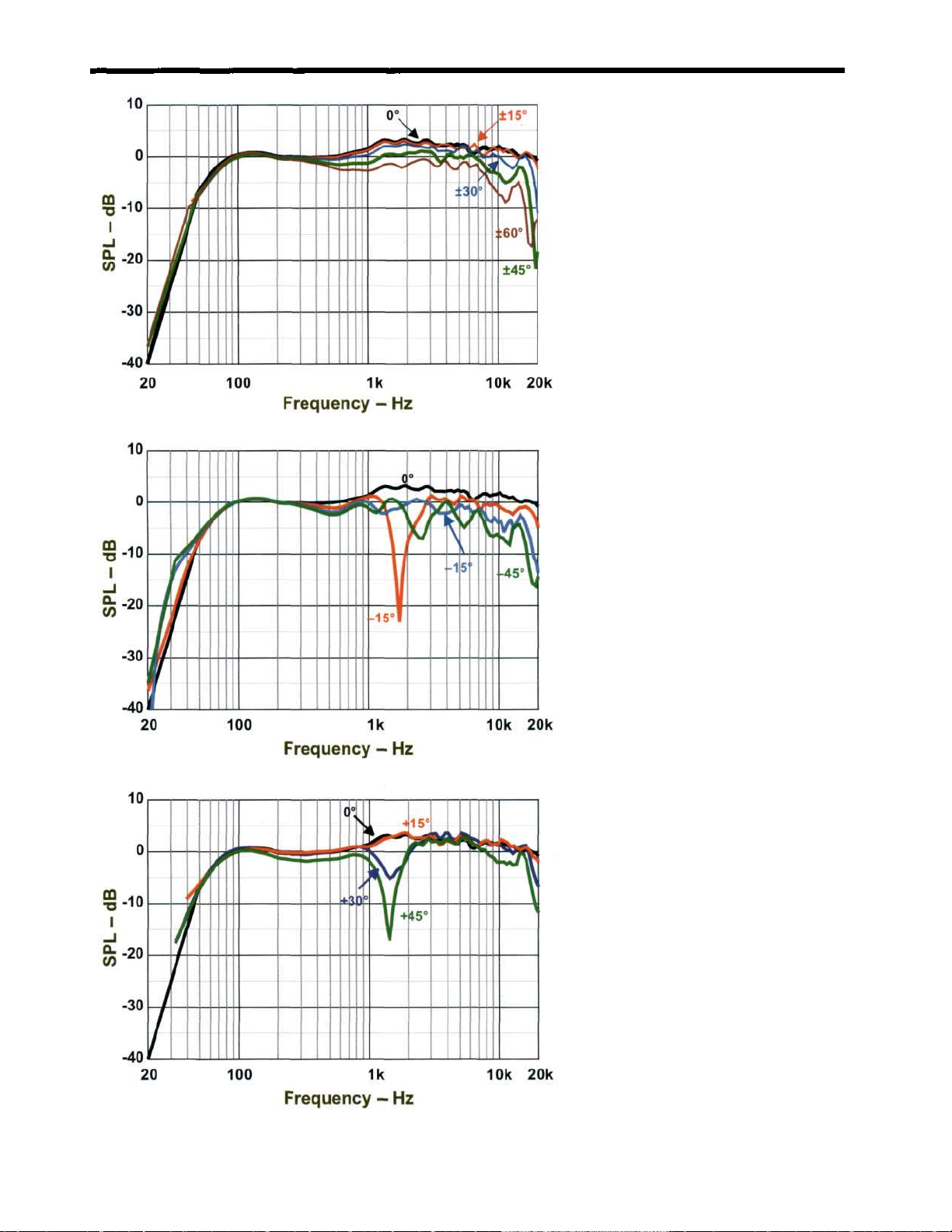

The characteristic on-axis response

of the CS1.6 is basically flat and

smooth, fitting inside a ±2 dB window

from its 45 Hz low limit to 8 kHz. At

higher frequencies, response slopes gently downward at approximately 3 dB

per octave. Off-axis response in the horizontal plane (Fig. 1) is very well controlled to ±30°, with only moderate

notching near the crossover at wider

angles. Vertically, response deteriorates

rapidly above axis (Fig. 2a); so it's absolutely necessary to aim the tweeter's

axis at the listener's ears by using the

speaker's spiked feet to angle its front

panel upward. Radiation below the axis

(Fig. 2b) is much smoother but, because the speaker is a floorstander, lis-

18 THE AUDIO CRITIC

pdf 19

Page 20

ISSUE NO. 29 • SUMMER/FALL 2003 19

Two-channel listening may be officially dead in this home-theater era, but

I listened to the CS1.6s as a stereo pair

so I could better hear what they were