Page 1

Retail price: U.S. $7.50, Can. $8.50

ISSUE NO. 28

Display until arrival

of Issue No. 29.

Floyd E.Toole,

arguably the world's leading

authority on loudspeakers,

explains what's right and

what's wrong with today's

speaker systems.

Also in this issue:

More loudspeaker reviews in depth, by Don Keele, David Rich,

and your ever faithful Editor.

Reviews of unusual amplifiers, SACD players, and assorted other

electronic components.

Plus our regular features, columns, letters to the

Editor, CD/SACD/DVD/DVD-A reviews, etc.

pdf 1

Page 2

contents

Audio Engineering:

Science in the Service of Art

By Floyd E. Toole

Speakers:

Two Big Ones, Two Little Ones,

and a Really Good Sub

By Peter Aczel, D. B. Keele Jr., and David A. Rich, Ph.D.

10"PoweredSubwoofer: Hsu Reseach VTF-2 15

Floor-Standing 4-Way Speaker with Powered Subwoofer:

Infinity "Intermezzo" 4.1t 16

Floor-Standing 4-Way Speaker: JBL Til0K 23

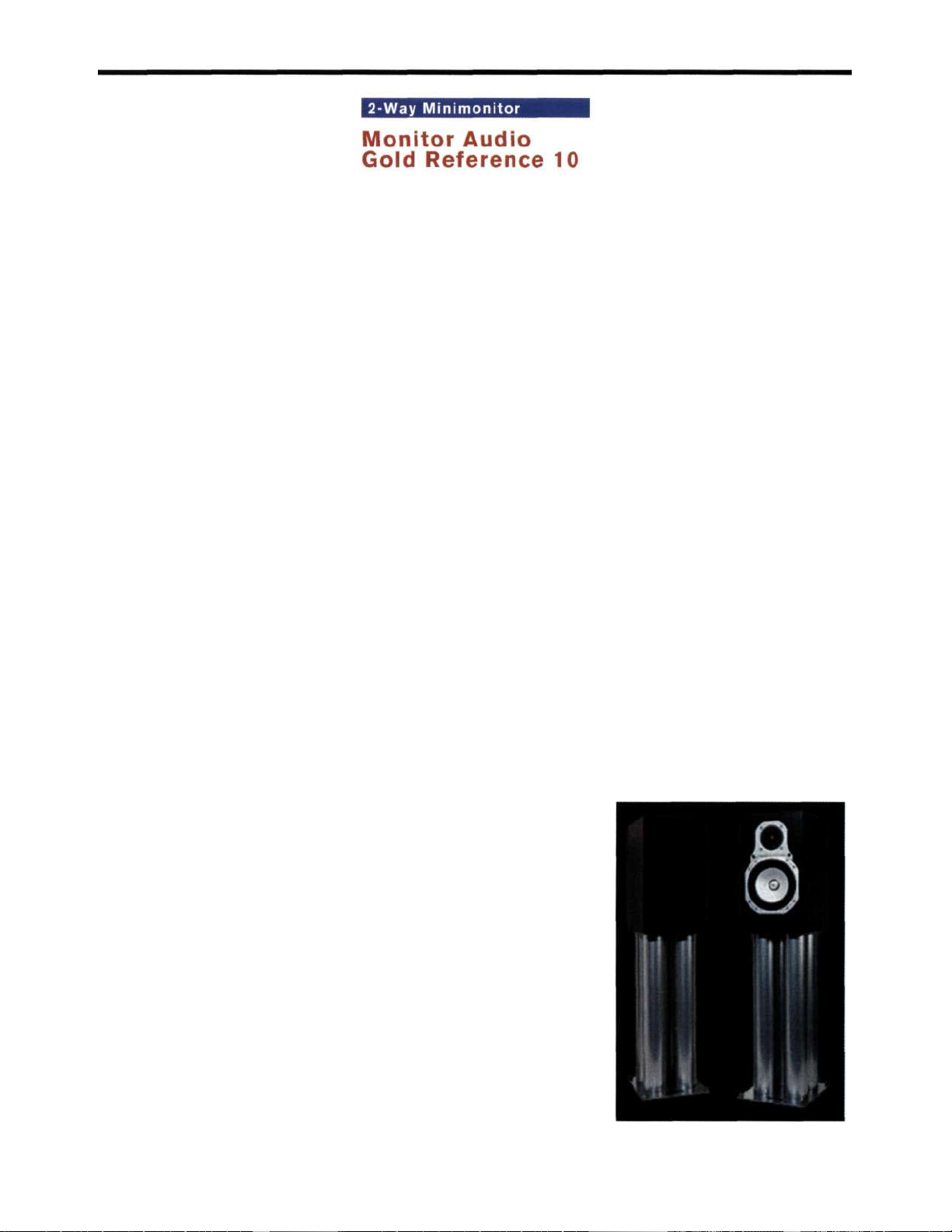

2-Way Minimonitor: Monitor Audio Gold Reference 10 24

Powered Minimonitor Speaker: NHTPro M-00 26

Electronics:

Seven Totally Unrelated Pieces of Electronic Gear

By Peter Aczel, Ivan Berger, Richard T. Modafferi, and David A. Rich, Ph.D.

Phono Preamp with AID Converter: B&K Phono 10D 31

Headphone Amplifier & Signal Processor: HeadRoom Total AirHead . . . ......32

2-Channel Power Amplifier: QSC Audio DCA 1222 33

1-Bit Amplifier & SACD Player: Sharp SM-SX1 & DX-SX1 35

5-Disc SACD Player: Sony SCD-C555ES 36

AM/FM/DAB Tuner: TAG McLaren Audio T32R 37

AV Electronics:

A Big TV, a Bigger TV, and Other Such

By Peter Aczel and Glenn O. Strauss

Bias Lighting for TV: Ideal-Lume 44

55"Rear-Projection TV: Mitsubishi WS-55907 45

Home Theater Projector:

Studio Experience's Boxlight Cinema 13HD 47

Broadband Internet Radio:

The Current State of Music on the Net

By David A. Rich, Ph.D.

Urban Audio Legends By Tom Nousaine 41

Capsule CD Reviews By Peter Aczel 51

Box 978: Letters to the Editor 3

ISSUE NO. 28 • SUMMER/FALL 2002 1

pdf 2

Page 3

From the

Back to Square One?

At the risk of being hopelessly unoriginal, I must reiterate

Murphy's Law. Edward A. Murphy, an American engineer,

observed sometime around 1958 that anything that can go

wrong will go wrong. In Issue No. 26 I announced, starryeyed, our alliance with the Canadian publisher called The

CM Group. In Issue No. 27 I hinted, maybe not at anything

having gone wrong, but certainly at some delays and slow

progress. Now, in Issue No. 28, I have to say that things have

gone wrong; indeed, the relationship is over. Not with a bang

but a whimper. The Canadians were nice guys; we never

fought; they just did nothing for the magazine. The partnership never really got off the ground; at this point we haven't

even talked to each other for a good many months. It's too

bad; I actually thought a huge turnaround was about to take

place. Murphy knew better.

So—you can see why this issue has been delayed. I basi-

cally did it all by myself, just as in the past, with long interruptions when the next move seemed uncertain. The

uncertainties were the reason why Ivan Berger, the former

Technical Editor of Audio magazine, did not take over as

guest editor of this issue as originally announced. He will,

however, take over the editing of No. 29, and I plan to retire

to a primarily supervisory position. I'll still contribute some

writing and I'll OK every word of the final product, but at

this point I'm too old and too much of a burnout to do the

whole thing alone. Under Ivan's capable hands our publishing

schedule should accelerate significantly, since I have been the

principal bottleneck. I'm not contemplating any new partnerships at this time, but if a really attractive offer should come

along, who knows?

Are we back to square one? I don't think so. The main

issue all along, as I see it now, was insufficient delegation of

editorial functions, not business partnerships to the rescue. I

held on too tightly, I did not let go, and I slowed things

down. I have finally decided to let go. Maybe we won't get

bigger that way but we'll come out more often.

2 THE AUDIO CRITIC

Printed in Canada

Editor and Publisher

Peter Aczel

Technical Editor David A. Rich

Contributing Editor Glenn O. Strauss

Contributing Editor Ivan Berger

Loudspeaker Reviewer D. B. Keele Jr.

Technical Consultant (RF) Richard T. Modafferi

Columnist Tom Nousaine

Art Director Michele Raes

Design and Prepress Tom Aczel

Layout Daniel MacBride

Business Manager Bodil Aczel

The Audio Critic® (ISSN 0146-4701) is published quarterly for $24 per year by Critic Publications, Inc., 1380

Masi Road, Quakertown, PA 18951-5221. Second-class

postage paid at Quakertown, PA. Postmaster: Send address changes to The Audio Critic, P.O. Box 978, Quakertown, PA 18951-0978.

Any conclusion, rating, recommendation, criticism, or

caveat published by The Audio Critic represents the

personal findings and judgments of the Editor and the

Staff, based only on the equipment available to their

scrutiny and on their knowledge of the subject, and is

therefore not offered to the reader as an infallible truth nor

as an irreversible opinion applying to all extant and forthcoming samples of a particular product. Address all editorial correspondence to The Editor, The Audio Critic,

P.O. Box 978, Quakertown, PA 18951-0978.

Contents of this issue copyright © 2002 by Critic Publications, Inc. All rights reserved under international and

Pan-American copyright conventions. Reproduction in

whole or in part is prohibited without the prior written permission of the Editor. Paraphrasing of product reviews for

advertising or commercial purposes is also prohibited

without prior written permission. The Audio Critic will

use all available means to prevent or prosecute any such

unauthorized use of its material or its name.

Subscription Information and Rates

You do not need a special form. Simply write your name

and address as legibly as possible on any piece of paper.

Preferably print or type. Enclose with payment. That's all.

We also accept VISA, MasterCard, and Discover, either

by mail, by telephone, or by fax.

We currently have only two subscription rates. If you live

in the U.S. or Canada, you pay $24 for four quarterly issues. If you live in any other country, you pay $38 for a

four-issue subscription by airmail. All payments from

abroad, including Canada, must be in U.S. funds, collectable in the U.S. without a service charge.

You may start your subscription with any issue, although

we feel that new subscribers should have a few back issues to gain a better understanding of what The Audio

Critic is all about. We still have Issues No. 11, 13, and 16

through 27 in stock. Issues earlier than No. 11 are now

out of print, as are No. 12, No. 14, and No. 15. Specify

which issues you want (at $24 per four). Please note that

we don't sell single issues by mail. You'll find those at

somewhat higher cost at selected newsdealers, bookstores, and audio stores.

Address all subscriptions to:

The Audio Critic, P.O. Box 978,

Quakertown, PA 18951-0978.

VISA/MasterCard/Discover: (215) 538-9555

Fax:(215)538-5432

pdf 3

Page 4

As a consequence of our erratic publishing schedule, we've been getting fewer

letters, but that was inevitable. More issues per year will surely bring more rele-

vant letters per issue. Please address all editorial correspondence to the Editor,

The Audio Critic, P.O. Box 978, Quakertown, PA 18951-0978.

The Audio Critic:

I am very happy to see that Don

Keele is back reviewing speakers; his

reviews of the only audio components

that actually affect the sound were the

best part of Audio. And no, they're not

too detailed! In fact, I was disappointed that his review of the Monitor

Audio Silver 9i did not show a graph

of the response with the grille on. One

of my pet peeves is how few speakers

are designed for optimal performance

with the grilles in place. I hope you

will take this up as one of your causes;

at the very least, you should state how

your listening and measuring are done

in every review.

Sincerely yours,

Mark Srednicki

Professor of Physics

University of California

Santa Barbara, CA

Some audiophiles want the grilles on,

others want them off. It's the neat look

versus the "cool" look, and you can optimize the response only for one of them.

You 're obviously a neat one, but I know

some 'philes who throw away the grilles!

Anyway, take a look at Don Keele's review of the Infinity "Intermezzo " 4.1t in

this issue; he is doing it the way you want it.

—Ed

The Audio Critic:

I followed up your very interesting

review of the Infinity "Interlude" IL40

[in Issue No. 27] with a visit to the Infinity Web site, where I found a technical paper (albeit geared to the general

reader) by Floyd E. Toole, "Audio—

Science in the Service of Art." [He uses

a very similar title for the totally different

lead article in this issue.—Ed.] In it he

outlines many of the results of his academic research prior to joining

Harman International. It is very encouraging to see such a solid scientist

in charge of technical oversight in such

a powerful audio enterprise as Harman

International.

One point he raises from his research has a bearing on the audio press,

and I wonder what your thoughts are

regarding it. His research found that

testers with even modest hearing loss

were very inconsistent among themselves in their preferences for speakers,

whereas testers with good hearing were

very consistent. While those with

hearing loss agreed with the goodhearing testers about the "good"

speakers chosen by the latter, they

would also choose "poor" speakers (as

judged consistently by the goodhearing testers) as "good." There was

also no consistency among testers with

hearing loss as to which of the "poor"

speakers was good. Listeners with

hearing loss were looking for a "pros-

thetic" loudspeaker that somehow

compensated for their disability, each

one having a somewhat different disability and therefore liking a different

"poor" speaker that just happened to

compensate.

Possible conclusions: The comments regarding the sound of speakers

in a review article are strongly suspect

unless the reviewer publishes his/her

hearing acuity test results. Reviewers

with tested and proven hearing acuity

should be hired to do listening tests by

conscientious audio magazines. Could

this explain why some of the "Black

Hat" reviewers have been so enthusiastic about wacko speakers with obvious sound colorings? Maybe they

have a hearing loss (too many rock

concerts?), and this particular colored

speaker just happens to compensate for

their problem.

Maybe it's time for "golden-eared"

reviewers to evaluate speakers, but this

time "golden-eared" will mean something objective. According to Toole's

paper, 75% of the population has

"normal" hearing, which is all we are

talking about here.

I am so delighted with the new

format, the new contributors (Keele in

particular), and especially the new

higher frequency of publishing. How

about more space spent on speakers, as

the electronics basically do their jobs

these days?

A very happy subscriber,

Gene Banman

Los Altos, CA

Huh? What did you say? Please speak

up . . . Seriously, though—to answer

your comments in reverse order—we are

devoting more space to speakers than anything else, witness this issue. The higher

frequency of publishing has not material-

ized yet but it will. (You celebrated pre-

maturely.) Although I believe that

reviewers' endorsements of wacko

speakers are more often than not politi-

ISSUE NO. 28 • SUMMER/FALL 2002 3

to the Editor

pdf 4

Page 5

cally, rather than physiologically, moti-

vated, I am in favor of published hearing

acuity tests—I'll be the second reviewer

to publish mine if the first can be found

under the prevailing political circum-

stances. Meanwhile a good rule thumb is

that flat response over a large solid angle

makes a speaker sound good, regardless of

the reviewers hearing acuity, and that

subjective reviewing without measurements is of very limited credibility.

—Ed.

The Audio Critic:

. . . Congratulations on stabilizing

the publication. If advertising is what

it takes, so be it. But let me assure you

that glossy paper and Garamond are,

in themselves, no more major-league

than matte paper and tastefully used

Times Roman—you had nothing to

apologize for in your old layout. Also,

I should point out that it would look

better—at least I think it would look

better—if the new typefaces used for

heads and copy were either truly in the

same family or markedly different

from each other. The close but not

quite matching styles are as discordant

as two notes a half step apart. This is a

separate matter from the additional

Gothic you're using for subheads and

captions, which is OK if not especially

distinguished.

Thanks again for keeping the flame

of reason lit in an insane world.

Yours truly,

Richard Kimmel

Bensenville, IL

As far as stabilization is concerned,

your congratulations are premature, as

our rupture with our Canadian associates and our tardy publishing schedule

clearly indicate. Advertising we've had

since 1987, or haven't you noticed? As for

your comments on our new page design,

you may very well be right; I won't de-

bate you. You appear to be a case of "The

Princess and the Pea" in typography,

whereas I am merely a commoner (well,

maybe a baron). Basically, we just

wanted a slightly more contemporary

image; the old layout had started to look

a bit too '70-ish. Than you for your

recognition of our fundamental thrust.

—Ed.

The Audio Critic:

First, I must say that I enjoy your

magazine and look forward to seeing it

grow, as there is a serious need for a

scientific bias in the audio field.

However, my main reason for

writing is your editorial in Issue No.

27 "Has Tom Holman Gone Off the

Deep End?" I would suggest that

you're the one who has gone off the

deep end. 'Course, maybe you're afraid

of the dark? Other than sound quality,

I came away with nothing resembling

your annoyances.

You seem to have missed what

Tom's objective was, although I may

have had some insight that you were

not privy to. I attended a special afterhours session and was involved in a

small-group conversation (mainly listening) with Tom as we waited in line.

As I understand it, Tom's objective is

to try and nudge the industry into

some kind of standard configuration in

which DVD-A's can be recorded. As it

stands now, as far as I know, we have

this extremely versatile high-capacity

medium but we don't have any idea

what we will need systemwise to enjoy

it. His demo was to show what might

be possible.

I came away from the demo quite

pleased, as I felt it clearly showed the

capability of the directional cues, especially to the rear. The soundstage

seemed stable even over a large area.

We were invited to wander around the

room when they later turned on some

light. I was especially impressed with

the system's ability to handle the theater-in-the-round with the audience at

the center. I agree completely with

your comments on the quality of the

sound. It was not convincing, but that

did not seem to me to be that important, although it would have been just

that much more impressive if it had

had gorgeous sound quality. According

to the comments by Tom during the

demo, there was a significant effort

EQ-wise to straighten out significant

bass problems. But they obviously

weren't very good at voicing the

system. They were using the PMC pro

speakers, but with some proper EQing of the mid/highs they could have

sounded a lot better in my opinion.

John Koval

Santa Ana, CA

We don't seem to have attended the

same demonstration. You apparently attended a breezy, informal one with twoway conversations—am I wrong? I

attended a stiff, formal, one-way music

demo with my head inserted (in effect)

into an unremovable black hood, against

my will. I found that to be both intolerable and illegal. Also, I obviously don't

have your ability to separate good directional cues from bad sound quality. To

me it was just bad sound in an impossibly uncomfortable environment. No,

I'm not afraid of the dark but I don't

wish to be without the option to leave.

—Ed.

The Audio Critic:

The following excerpt comes from

2000 IEEE President Bruce Eisentein's

column in the August 1999 issue of

The Institute:

"... there are two ways in which

advances can impact companies or organizations: 'sustaining' technologies

and 'disruptive' technologies. Sustaining technologies, which can be radical or incremental in nature, are those

that improve the performance of established products or services. By contrast, disruptive technologies result in

worse performance of existing products, but have value to new (emphasis

on new) customers."

(continued on page 39)

4 THE AUDIO CRITIC

pdf 5

Page 6

By FLOYD E. TOOLE, Vice President, Acoustical Enqineerinq, Harman International Industries, Inc.

Science in the Service of Art

This article, in a somewhat different form, was presented by Floyd

Toole as his keynote speech at the opening of the Audio Engineering

Society's 111th Convention in New York City on November 30,

2001. Unlike most keynote speeches, which say absolutely nothing,

this one was mainly about the realities of loudspeaker performance, so

in the end it was not really a keynote speech.—Ed.

There is artistic audio engineering and there is technical

audio engineering.

The engineers who work with artists manipulate the

audio signals in many different ways in order to create a suitable information or entertainment document. This is a highly

subjective activity, but many of these people are also technically knowledgeable.

The engineers who design the hardware used in studios

and homes need technical data to do their designs and to

evaluate progress toward their performance targets. Although

technically focused, most of these people came to the industry with an appreciation of music, good sound, and the

artistry within it.

Music and movies are art. Audio is a science. "Science in

the service of art" is our business. The final evaluation, however, of any audio product, hardware or software, is a listening test—and that is part of the problem. How do we

determine what causes something to sound "good" or "bad"?

The audio industry is in a "circle of confusion." Loudspeakers are evaluated by using recordings . . . which are

made by using microphones, equalization, reverb, and effects . . . which are evaluated by using loudspeakers . . .

which are evaluated by using recordings . . . etc., etc.

Recordings are then used to evaluate audio products. This

is equivalent to doing a measurement with an uncalibrated

instrument! Of course, professional audio engineers use professional monitor loudspeakers . . . which are also evaluated

by using recordings . . . which are made by using micro-

phones, etc. . . . which are evaluated by using professional

monitor loudspeakers . . . which are once again evaluated

by using recordings . . . which are then auditioned through

consumer loudspeakers! Thus the circle of confusion continues. It is broken only when the professional monitor

loudspeakers and the consumer loudspeakers sound like

each other—when they have the same sonic signature, i.e.,

when they are similarly good. (Of course, sounding alike

ISSUE NO. 28 • SUMMER/FALL 2002 5

pdf 6

Page 7

also includes the interface with the room and the listener

within it.) Then, and only then, can we hope to preserve

the art. All else is playing games.

Let us use a visual analogy.

Red happens to be at the low end of the visible spectrum,

so this is comparable to having 3 dB too much bass. In this

case the artist would adjust the tints in his oils to compensate for the color of the illuminating light. Thus the appreciation of the art will be at odds with the creation of the art.

It is a purely technical problem: the color of the light has

caused good art to be distorted. A measurement would have

prevented this.

Without skin tone, grass, or sky we have no instinctive

way to guess that something might be wrong with the picture. The audio equivalent to this is the multitrack studio

creation. The only reality is what is heard through speakers

in a room.

This is why visual artists seek out studios with neutral,

usually north, light, and art galleries display their works

under the same kind of light. The viewer should see exactly

what the artist created. That's preservation of the art.

In audio, this is a problem to which there is not a single, or

6 THE AUDIO CRITIC

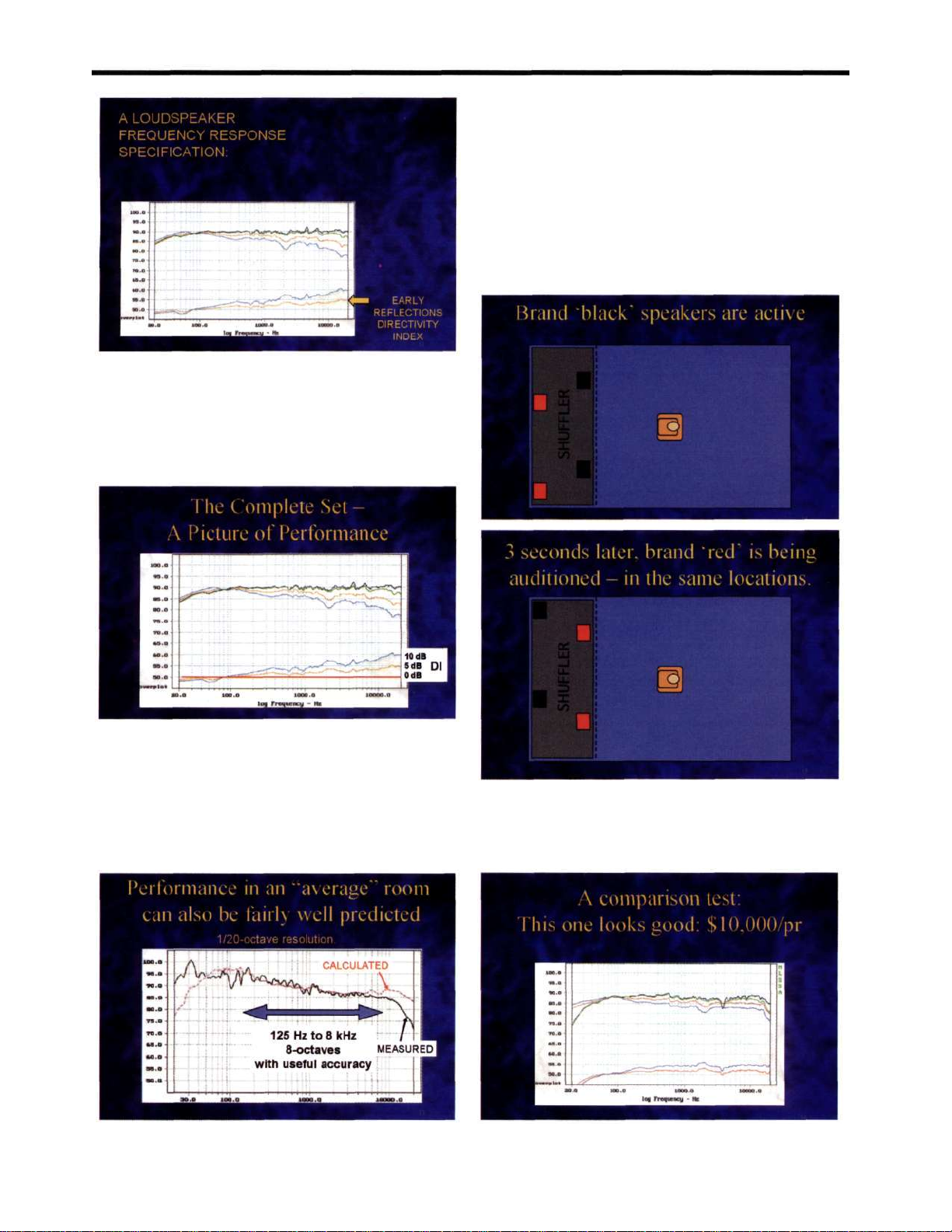

a simple, solution. Scientific design requires: (a) carefully con-

trolled listening tests, i.e., subjective measurements, combined

with (b) accurate and comprehensive technical measurements,

combined with (c) knowledge of the psychoacoustic relationships between perceptions and measurements. For example,

let's look at frequency response—the single most important

technical specification of audio components.

This is an example of the kind of tolerances applied to

loudspeakers—and here, to make things worse, it is a steadystate measurement in a room. This is not a single performance objective. It implies that all variations that fall within

the limits are audibly acceptable. Rubbish! Why do we

change the rules for loudspeakers? We shouldn't! The same

rules apply.

How did we get into this situation?

• Technically, loudspeakers are difficult to measure.

Many anechoic, high-resolution measurements and computer processing are needed. That's expensive and time-consuming. Few people in the world are able to do it.

• Subjectively, many factors can introduce bias and variability into opinions. Selecting and training listeners, and

controlling the "nuisance variables," are expensive and timeconsuming. Few people in the world bother to do it.

pdf 7

Page 8

• Practically, the room is the final audio component.

Rooms audibly modify many aspects of sound quality. All

rooms are different.

But—does it matter? Is there a problem with things as they

are? Let's check out the state of affairs at the "appreciation"

end of the chain. What are consumers listening to these days?

From the science that has been done, we conclude that

there are two domains of influence in what is heard in a

room. In-room measurements, acoustical manipulations, and

equalization can improve performance in the 20 Hz to 500

Hz region. But the only solution for the portion above 500

Hz is a loudspeaker that is properly designed. These measurements must first be done in an anechoic space. Then, and

only then, can we interpret the meaning of measurements

made in a room. We need to know what the loudspeaker

sent into the room before we can evaluate what the room has

done to it. An anechoic chamber is a space without echoes

or reflections. From a large number of measurements made

in this space, it is possible to calculate predictions of what

will be heard in real rooms.

ISSUE NO. 28 • SUMMER/FALL 2002 7

pdf 8

Page 9

From these anechoic data it is possible to be quite analytical about the individual components of the sound field

within a room. It is from data like these that we can learn

about the correlations between what we measure and what

we hear—the psychoacoustic rules.

A presentation like this gives us a capsule view of loudspeaker performance as it relates to listening in a room. Differences among the curves indicate conflicts in the timbral

signatures of direct, reflected, and reverberant sounds—

something that contradicts natural experience, and that listeners react negatively to.

When averaged over a reasonable listening area in a

room, the predictions are remarkably good. A little more

work would make the predictions even more precise.

Measurements make a nice story, but can people really

hear the differences? Let's test them.

A serious problem with listening tests is that the position

of the loudspeaker affects how it sounds. We at Harman International neutralize this with a computer-controlled, pneumatically operated shuffler.

The listener controls the exchanges while forming opinions. The listener sees only an acoustically transparent black

screen. The tests are double-blind.

8 THE AUDIO CRITIC

pdf 9

Page 10

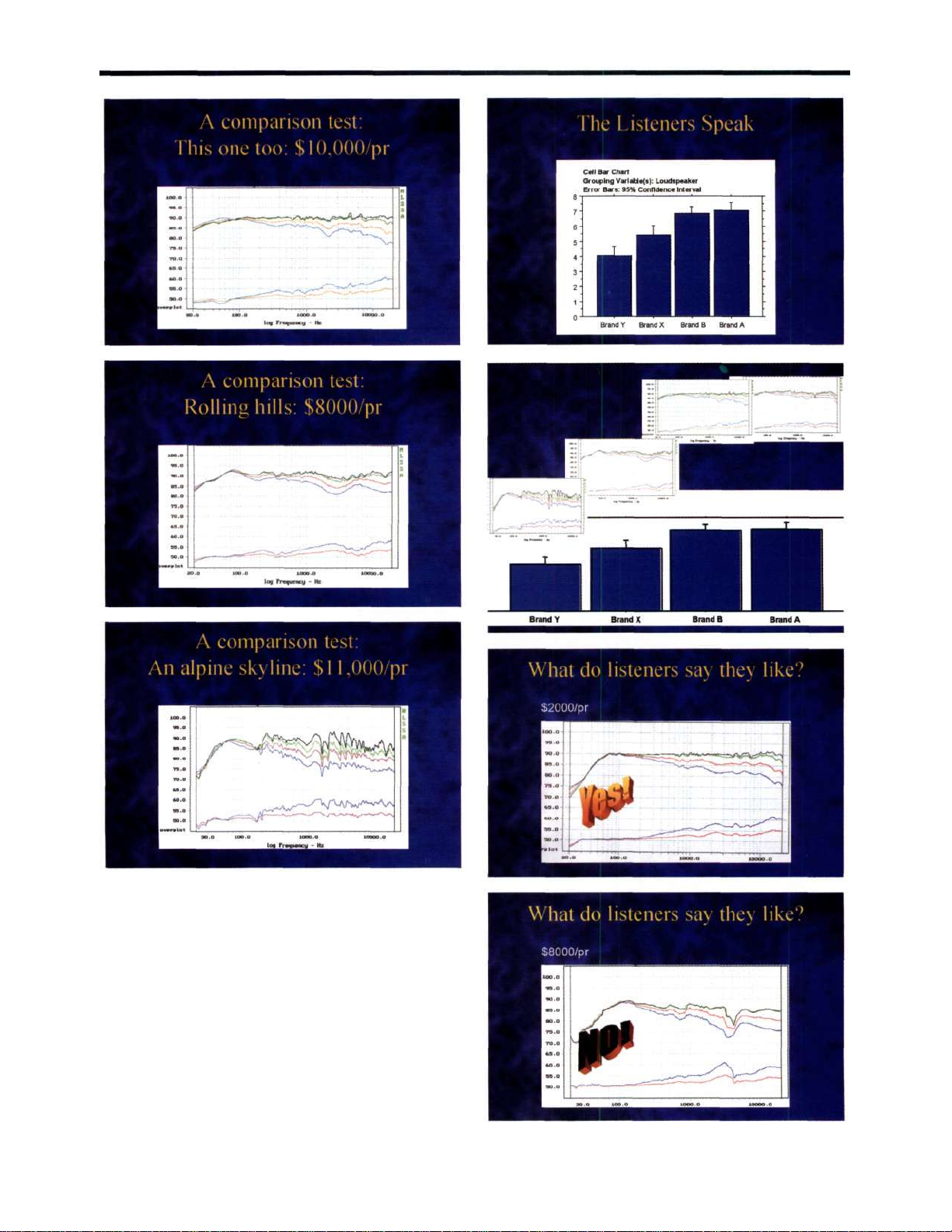

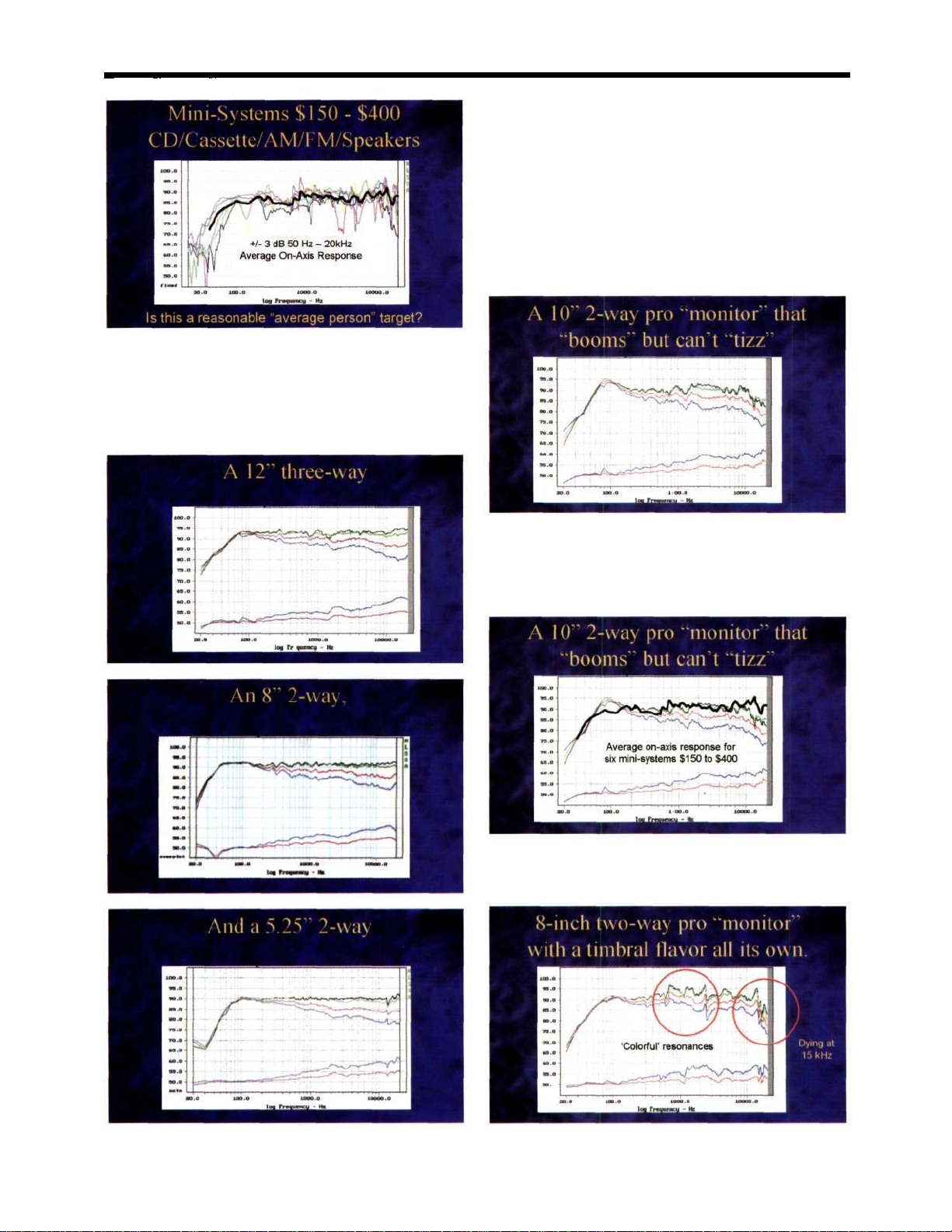

Without listening, it is evident that all of these loudspeakers were not designed to meet the same performance

objectives or, if they were, there were differences in the abilities of the engineers to achieve the objectives. The prices,

though, suggest "high-end" audiophile aspirations for all.

The juxtaposition of subjective and objective data is very

convincing. It seems that our technical data are revealing essentials of performance that correlate with the opinions of

listeners in a room.

We do tests of this kind at Harman International as a

matter of routine, in competitive analysis of proposed new

products. The results are monotonously similar.

ISSUE NO. 28 • SUMMER/FALL 2002 9

pdf 10

Page 11

10 THE AUDIO CRITIC

And then there are companies that seem not to care how

their products sound. This is from a very well-known and

well-advertised brand, which is also known in the professional audio community.

At this stage it is safe to say that we are well on our way

to having a reliable relationship between subjective and objective evaluations. It is not perfect. We don't know everything about these multidimensional domains. However,

there are amazingly few surprises when we compare the results of technical tests and the results of listening tests. The

final arbiter of quality, nevertheless, is always the subjective

evaluation.

The professional audio community is very sensitive to

how average consumers will react to their creations. Consequently, they will take their mixes home, listening to them

in the car on the way, and playing it through an 'ordinary'

stereo at home, to see how it survives less than ideal reproduction. So, what is 'ordinary'? For a glimpse into the true

entry-level product category, here are six mini-systems, containing everything needed, for remarkably low prices. The

first thing to note is that no two are exactly alike. In fact,

poor sound comes in an infinity forms. It is a moving target.

It is clear that good acoustical performance is available at

moderate prices—as well as some less good offerings.

Here is an entry-level product that still has basic integrity. It may not play as loud, or look as elegant, or have

the bass extension of more expensive products, but it is doing

an honest job at a challenging price.

pdf 11

Page 12

ISSUE NO. 28 • SUMMER/FALL 2002 11

Even the "average" cheap minisystem doesn't fail in these

ways.

In this age of 40 to 50 kHz bandwidth, here is a speaker

that is going south at 10 kHz! The bass bump at 100 Hz is

reminiscent of many small bookshelf speakers aimed at the

mass market. There is no low bass.

A current good product. Another. And another. These

good examples of the breed are competitive in sound quality

with the best loudspeakers from the world of consumer audiophiles. And such monitors are also useful references for

average consumer "entry-level" systems (when we compare

their responses to the averaged six-mini-system response

above).

However, "professional" or "monitor" in a product description guarantees nothing in terms of sound quality!

However, in the average of the six systems, we can see that

perhaps they were all aimed at smooth and flat but simply

failed, in different ways, to achieve it.

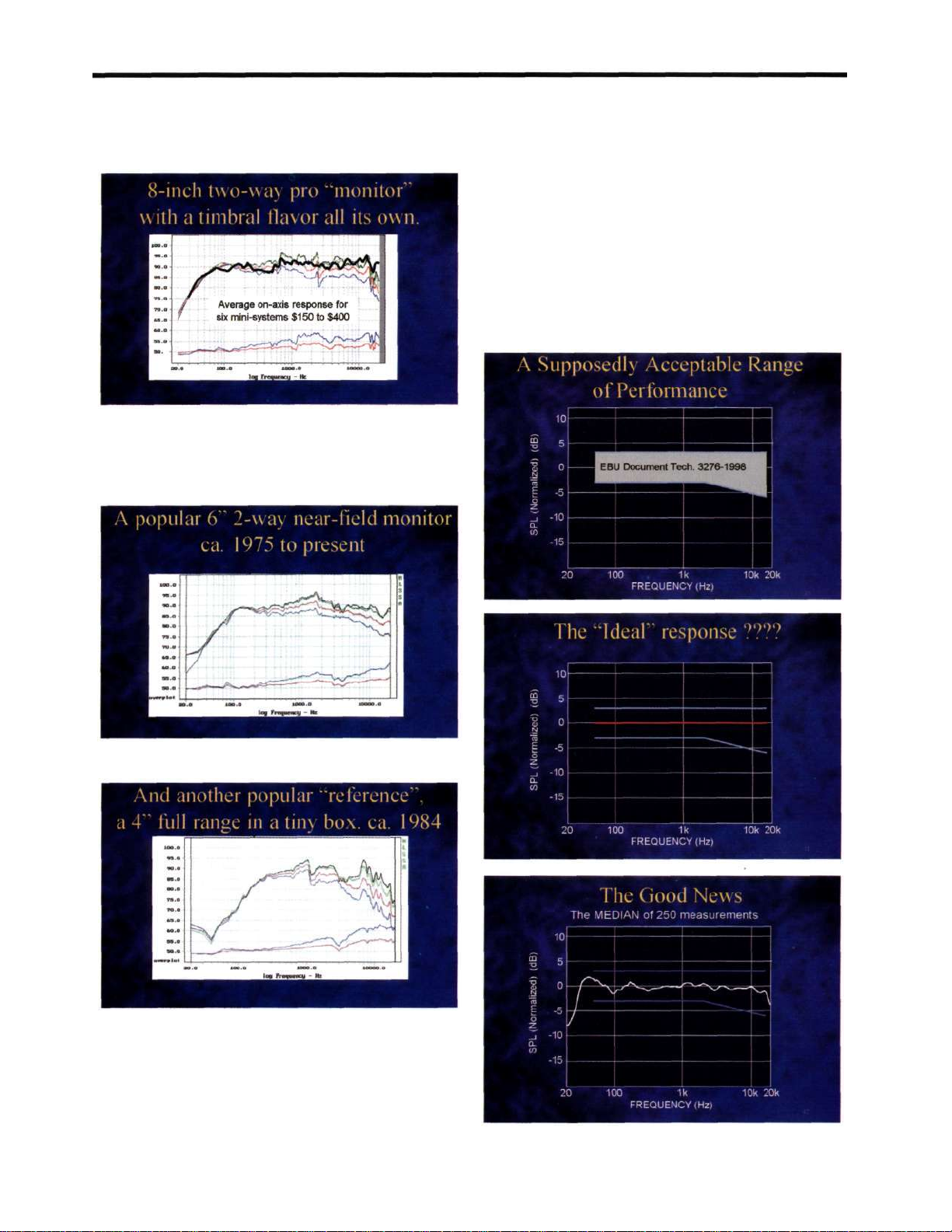

With this perspective on consumer loudspeakers, let us

look at the status of professional audio monitoring.

pdf 12

Page 13

Another well-known maker has editorialized on the

sounds in ways that no consumer product is likely to imitate

exactly.

Now, what happens when we add the room to the equation? A study of control-room monitoring conditions was

presented at the 19th AES Conference, June 2001, by

Mäkivirta and Anet under the title of "The Quality of Professional Surround Audio Reproduction—A Survey Study."

Thanks to the considerable efforts of these gentlemen, the

industry has been given a special perspective on what is happening in recording studios. The study was sponsored by one

of our respected competitors. It covered many loudspeakers

in many monitoring rooms. The speakers were all of the

same family, all 3-way, and they were measured at the engineer's listening position.

The average minisystem is arguably better.

Other loudspeakers came to be used because it was believed that they exemplified a common form of mediocrity

in the lives of the listening public.

Even Kleenex over the tweeters couldn't fix this.

Yup. This one must target the listening audience that

uses the clock radios in our hotel rooms.

Speakers like these are no longer relevant to the audio industry. Thanks to progress in the world of consumer audio,

the quality bar has been raised!

12 THE AUDIO CRITIC

pdf 13

Page 14

ISSUE NO. 28 • SUMMER/FALL 2002 13

Clearly, the real culprit here is the loudspeaker/room/

listener interface.

And even half of the population included variations that

were not subtle.

Even 90% included some very deviant sounds.

However, some were horribly wrong.

As a picture of our industry, this is frightening.

But what is going wrong? What are we measuring here?

There are lies, damned lies, and then there are statistics.

In this we see such an example. The "average" system is actually impressively good.

pdf 14

Page 15

14 THE AUDIO CRITIC

The key to successful equalization is in knowing what tools

to use to address specific problems.

We have most of the science. We need to teach it more

widely. And we need to be much more diligent about applying it.

Thank you!

These are pretty good, suggesting that little or no equal-

ization was done in this frequency range.

In Summary:

• Loudspeakers are not the biggest problem in the audio

industry.

• Numerous similarly excellent consumer and studio-

monitor loudspeakers are in the marketplace. Some are even

relatively inexpensive.

• In spite of an elevated average quality level, there are

still many truly inferior products out there. Caveat emptor!

• The loudspeaker/room/listener interface is a very se-

rious problem throughout the audio industry, in homes and

in music and film studios.

• Accurate, high-resolution in-room measurements,

along with acoustical corrections and equalization, are necessary to deliver truly good sound to listeners' ears in homes

and in studios.

The "traditional" technique of in-room equalization

needs to be improved. Measurements must have high resolution; -octave resolution is not adequate, especially at low

frequencies. Passive acoustical equalization needs to be combined with "intelligent" electronic parametric equalization.

pdf 15

Page 16

By Peter Aczel, Editor

D. B. Keele Jr., Contributing Editor

David A. Rich, Ph.D., Technical Editor

Two Big Ones, Two Little Ones,

and a Really Good Sub.

A

fter three decades of serious

technical involvement with

loudspeakers, I have come to a

startlingly simple conclusion regarding

performance requirements. It isn't

enough to have the best possible drivers. It isn't enough to have the most

solid and least diffractive enclosure. It

isn't enough to have the best possible

crossover. It isn't enough to have correct spacing between the drivers. It isn't

enough to have the most carefully optimized bass tuning. You've got to have

them all—and that includes all other

requisites I haven't mentioned. Concentrating on one or two aspects of

loudspeaker design and neglecting the

others, as most manufacturers do, will

not result in outstanding performance.

That is true even when there is a revolutionary breakthrough in one design

area but scant attention paid to the rest.

Am I pointing out the obvious?

Then why does nearly every speaker designer fail to cover all bases and leave

holes in his design? How many truly

complete loudspeaker designs are there

today? How many that don't assume

about one design aspect or another that

"oh, that's nothing, it's not important"

or "oh, that's not practical in this design"?

My ideal, or at least something

close to it, in the quest for a complete

design is represented by the Waveform

Mach 17 speaker system (reviewed in

Issues No. 24 and 25), which unfortunately is no longer available as a consequence of owner/designer John Ötvös's

decision to close shop. It started out

with state-of-the-art OEM drivers

(probably surpassable today but not at

the time of design, in 1996) and had

the midrange and tweeter mounted in

an egg-shaped enclosure, which is the

theoretical optimum for minimizing

diffraction. There were no passive

crossover elements; the three-way

crossover was entirely electronic, with

trimming controls for all three channels. The manageably sized bass enclosure was tuned and equalized to be

essentially flat to 20 Hz. And so on—

this is a very superficial and incomplete

summary of the design merely to illustrate my point, namely that no aspect

of optimal design was neglected. The

recently announced "Helix" by Legacy

Audio is another design that holds out

some promise of being complete, in an

altogether different and perhaps more

up-to-date way. (Just guessing; nobody

has tested it yet.) Perhaps there are

others out there that I haven't even

heard of, but there couldn't be many.

Even Floyd Toole's top-of-the-line

speakers at Infinity and JBL, excellent

as they are, are limited to some extent

by inevitable tradeoffs of cost and complexity against performance (see Don

Keele's review of the Infinity Intermezzo 4.11 below).

—Peter Aczel

Hsu Research, Inc., 3160 East La Palma

Avenue, Unit D, Anaheim, CA 92806.

Voice: (714) 666-9260. Fax: (714) 666-

9261. E-mail: hsures@earthlink.net. Web:

www.hsuresearch.com. VTF-2 variabletuning-frequency 10-inch powered subwoofer, $499.00 each (factory-direct,

$45.00 shipping/handling). Tested sample

on loan from manufacturer.

Every once in a while a product

comes along that is completely polished

and perfected, with nothing left to be

improved at its price point. I feel that

the Hsu Research VTF-2 is such a

product. It wasn't always so with Dr.

Poh Ser Hsu's subwoofers; some of his

earlier products, although invariably

brilliant in design and superior in performance, were a bit on the crude side

in construction and packaging. Not so

ISSUE NO. 28 • SUMMER/FALL 2002 15

pdf 16

Page 17

in the case of the VTF-2—this is a beautifully finished and integtated subwoofer system, complete in every

respect, with electronics and controls,

impeccable in performance, and most

reasonably priced. My heart is filled

with admiration; I didn't really expect

such perfection.

The subwoofer system is a compact

and almost cubical box, 18½" deep by

16" wide by 16" high (with feet); the

heat sinks of the integrated 150-watt

amplifier stick out an additional 1½" in

the back; the edges are rounded; the

finish is black crackle paint, which suggests metal, although the box is made of

heavy fiberboard. It is a highly professional look, a far cry from the paperbarrel Hsu subwoofers of years ago. The

bass driver is a magnetically shielded

10" unit that fires downward into the

cavity formed by the feet, and there are

two huge flared ports on either side of

the box, one of them plugged up. The

foam plug can be removed, thereby

changing the tuning from 25 Hz to 32

Hz (manufacturer's specs) and substan-

tially increasing the output between 30

and 50 Hz. Home theater sound can

particularly benefit from the two-portsopen mode. There are two controls on

the amplifier panel in the back: volume

(naturally) and variable crossover frequency from 30 Hz to 90 Hz.

My nearfield measurements in the

one-port-open mode indicated classic

B4 tuning, both the woofer null and

the maximum vent output occurring at

24 Hz (that's close enough to the 25

Hz specified by the manufacturer). The

summed nearfield response of the

woofer and vent was within +1.5 dB

from 100 Hz all the way down to 22

Hz. In the two-ports-open mode, the

woofer null and maximum output

from the vents occurred at 34 Hz, and

the summed nearfield response of the

three apertures (difficult to obtain and

therefore approximate) was +1.5 dB

from 100 Hz to 40 Hz. In other words,

the tuning of the box and the resulting

output were pretty nearly optimal and

on spec. Beautiful design.

I measured the distortion of the

VTF-2 only in the one-port-open mode

because the summing junction of the

woofer and vent could be much more

accurately located in that mode than

with two ports open. The nearfield distortion of a 50 Hz tone at a 1 -meter SPL

of approximately 100 dB was 0.63%. At

40 Hz and approximately 95 dB it was

1.6%. The 30 Hz measurement was

made at a 2-meter SPL of approximately

100 dB because the output appeared to

be higher at 2 meters than at 1 meter.

The distortion was only 1.7%! These

are brilliant results. The subwoofer is

not only deep and flat in response but

also exceptionally clean.

How does it sound? Exactly as it

measures, as I have said many times before. A subwoofer is a relatively simple

device that presents no mysteries and

hides no subtleties. It has a frequency

response, a dynamic limit, and a distortion range—that's it. (Wave launch,

dispersion, power response, etc.—so

important in the evaluation of fullrange speakers—do not enter the picture at all.) Thus the Hsu Research

VTF-2 is the equal of any subwoofer,

even those costing three to four times as

much, down to well below 30 Hz. In

the 15 to 25 Hz range, a few 15" and

18" models may exceed it in output

and low distortion (at a tremendous increase in price), but those frequencies

seldom occur in music and almost

never in movies. On a per-dollar basis,

direct from the factory, the VTF-2 is

best subwoofer known to me.

—Peter Aczel

Infinity Systems, Inc., a Harman International Company, 250 Crossways Park

Drive, Woodbury, NY 11797. Voice: (800)

553-3332. Fax: (516) 682-3523. Web:

www.infinitysystems.com. Intermezzo 4.1t

floor-standing 4-way loudspeaker system

with built-in powered subwoofer. $3500.00

the pair. Tested samples on loan from manufacturer.

Editor's Note: I hasten to point out,

before the self-righteous element in the

audio community does, that Don Keele is

currently employed by Harman/Becker

Automotive Systems, which is owned by

the same parent company as Infinity Systems, namely Harman International.

Harman/Becker and Infinity are totally

independent of each other, without any

overlap; in fact, they are located 700 miles

apart—but they are connected via Sidney

Harman's pocket. He, or more precisely

his company, owns a significant percentage of the audio industry, so that any

one of the limited number of truly quali-

fied audio engineers (like Don Keele) has

more than a small chance of falling within

his purview. It can't be helped. As I

pointed out in one of the earliest issues of

The Audio Critic, in the late 70s, the al-

ternative is to use reviewers totally unconnected to the audio industry, such as

audiophile dentists. Other magazines do.

Unfortunately, said dentists don't know

the difference between MLS and ETF,

and that matters to me more than our

reviewers' affiliations. I can assure you, in

an event, that no one at the corporate of-

fices of Harman International even knew

about this review, let alone influenced it.

16 THE AUDIO CRITIC

Intermezzo: a short musical movement separating the major sections of

a lengthy composition or work; or in-

termediate: one that is in a middle po-

sition or state. Both terms aptly

pdf 17

Page 18

ISSUE NO. 28 • SUMMER/FALL 2002 17

Infinity "Intermezzo" 4.1t rear panel

the system is devoted to a rather sizable

closed-box enclosure housing the 12"

woofer, amplifier, system controls, and

connections. All driver diaphragms utilize Infinity's sandwiched composite

metal/ceramic diaphragm material,

which is said to be light weight, quite

rigid and inert, and allows all the drivers

to operate essentially as pure pistons

over their respective operating bandwidths.

I last reviewed a set of an Infinity

systems similar to the 4.1t for Audio

magazine back in 1996. These were

the Infinity Compositions P-FR systems, which are similar to the current

Prelude MTS line. It performed excellently in all regards except for a lowfrequency response that did not quite

keep up with its upper bass and

higher-frequency performance. My

measurements of the bass output of the

Intermezzo 4.1t, described later, reveal

that it quite significantly outperformed

the bass response of the P-FR systems.

Infinity has been doing their homework! The bass improvements started

with the higher-priced Prelude MTS

line, whose subwoofer is quite similar

to the 4.1t's. The Intermezzo line includes a separate powered subwoofer,

the 1.2s, which is equally powerful.

The Intermezzo 4.1t includes a

rich complement of controls and inputs on the rear panel of the subwoofer enclosure (see rear panel

graphic). The system is equally at

home in a complex home theater setup

or a simpler two-channel stereo situa-

tion. Inputs and controls have been

provided for many different operating

configurations, from standalone stereo

operation driven by an external power

amplifier with the system's sub deriving its signal from the speakers terminals, to a complicated home theater

setup driven by a Dolby Digital or

DTS processor with separate power

amplifiers or a multichannel amplifier.

The 4.1t's subwoofer power ampli-

fier utilizes a high-efficiency switch-

describe the subject of this issue's loud-

speaker review, the Infinity "Intermezzo" 4.1t, by appropriately tying

together function and music. The 4.1t

is simultaneously an intermediate

speaker in Infinity's home theater

lines, positioned between the higher-

priced Prelude MTS and the lower-

priced Interlude, Entra, and Modulus

lines; and at the same time, of course,

does an excellent job playing music.

The Intermezzo 4.1t is a tall and

relatively narrow floor-standing loudspeaker with built-in powered sub-

woofer, packaged in a total system that

combines first-class industrial design

and handsome good looks. The 4.1t

system couples a three-way direct-radiator system operating above 80 Hz to

a powerful subwoofer using a side-fired

very-high-excursion 12" metal-cone

woofer operating in a closed-box enclosure, powered by a built-in 850-

watt power amplifier.

The upper three-way portion of

the design is passive and combines a

6½" cone midbass driver with a 3½"

midrange and a 1" dome tweeter, all of

which are mounted on the front of the

enclosure and crossed over at a rapid

24 dB/octave rate. The bottom half of

pdf 18

Page 19

mode tracking power supply powering

a class-AB amplifier. The power

supply's output voltage tracks the

audio signal in such a way as to minimize output device power dissipation.

Quoting the 4.1t's owners manual:

"The result is an extremely efficient

audio amplifier that does not compromise audio performance." The

tracking power supply is not unique

with Infinity, however; it first started

out primarily in the professional audio

field (Crown International and Carver

were among the first to offer the feature on their amplifiers) and then

trickled down to the home market.

The 4.1t includes a single parametric subwoofer equalizer in its bass

electronics, intended for smoothing

the subwoofer's response in its listening environment. As is well known,

the listening room heavily influences

what is heard from a loudspeaker in

the bass range below 100 Hz. The

equalizer, if set properly, can effectively

optimize the Intermezzo's subwoofer

response to complement most listening

environments. The parametric equalizer can provide a variable-width cut or

dip of arbitrary frequency and depth,

which, if matched to a room peak, can

considerably smooth out the system's

in-room response. As pointed out by

Infinity, this also improves the system's

transient response because the low-frequency speaker-to-room response is essentially minimum phase.

(Techno-geek comment: If a system is

minimum phase and its frequency response magnitude is equalized flat with

a minimum-phase equalizer, its phase

response will follow and also be equalized flat, and hence its transient response or time behavior will be

optimized.)

This theory is all well and good,

but how does the user know how to set

his equalizer for optimum results? On

the one hand he/she could hire an expensive acoustical engineer to come in

with his one-third-octave real-time

R.A.B.O.S. Sound Level Meter

spectrum analyzer, noise generator, and

calibrated microphone, and properly set

the equalizer after doing some measurements. Or, on the other hand—tuh

da!—the user could employ Infinity's

slim LED sound level meter (see Sound

Level Meter graphic) and the accompanying test CD with detailed instructions, which are supplied with the 4.1t

to accomplish the same task. Gee, Infinity thinks of everything! Infinity calls

their adjustment system R.A.B.O.S. or

Room Adaptive Bass Optimization

System (love that acronym!). It comes

with documentation and bass response

graphs that the user fills in, along with

a circular hinged clear-plastic protractor-like gizmo, called a "Width Selector" by Infinity, that allows the user

to rapidly determine the Q or resonance

width of the dominant peak in the

system's response (see Width Selector

graphic). Matching a speaker/room response peak by adjusting the parametric

filter's notch depth and frequency is relatively easy; however, this is not the case

with the Q adjustment. More on this

subject later, in the use and listening

section.

Width Selector Graphic

quency response of the subwoofer, and

(2) windowed in-room tests to mea-

sure mid-to-high-frequency response.

The test microphone was aimed

halfway between the midrange and

tweeter at a distance of one meter with

2.83 V rms applied. One-tenth octave

smoothing was used in all the following curves.

The on-axis response of the 4.1t,

with grille on and off, is shown in Fig.

1, along with the response of the subwoofer. Without grille, the response of

the upper frequency portion of the

curve (excluding the sub) is very flat

and fits a tight 3-dB window from 95

Hz to 20 kHz. The woofer exhibits a

bandpass response centered on about

50 Hz and is 6 dB down at about 25

and 90 Hz. In the figure, the woofer's

response has been level adjusted to

roughly match the level of the upper

frequency response. Averaged between

250 Hz and 4 kHz, the 4.1t's 2.83 V

rms/1 m sensitivity came out to 86.2

dB, essentially equaling Infinity's 87

dB rating. The grille caused moderate

response aberrations above 4 kHz,

with a reduction in level between 3

and 11 kHz, a slight peak at 12.5 kHz,

followed by a dip at 17 kHz. The grille

can be easily removed for serious listening if required. The right and left

systems were matched fairly closely, fit-

ting a ± 1.5 dB window above 150 Hz.

18 THE AUDIO CRITIC

The Intermezzo 4.1t's frequency

response was measured using two different test techniques: (1) nearfield

measurements to assess the low-fre-

pdf 19

Page 20

Fig. 1: One-meter, on-axis frequency response with 2.83 V rms applied.

The Intermezzo 4.1t's horizontal

and vertical off-axis frequency responses are shown in Figs. 2 through

4, respectively. The horizontal off-axis

curves with 15° increments in Fig. 2

are well-behaved but exhibit rolloff

above 12 kHz at angles of 30° and beyond. The system's vertical off-axis

curves out to ±15° in Figs. 3 (up) and

4 (down) are exceptionally well-behaved and exhibit hardly any response

aberrations through the upper

crossover region between 2 and 3 kHz.

Figs. 5 and 6 show the input impedance magnitude and phase of the

upper frequency portion of the 4.1t

(less subwoofer), with and without the

system's highpass filter engaged. Fig. 5

indicates an impedance minimum of

3.2 ohms at 120 Hz with the highpass

engaged, and a maximum of about 18

ohms is exhibited at 2.8 kHz with the

highpass off. With the highpass filter

engaged, the system's impedance rises

to above 20 ohms at 20 Hz. The minimum rises to 4.4 ohms with the highpass off. The system's impedance

phase in Fig. 6 appropriately follows

the magnitude response as any well-behaved minimum-phase impedance

should. With the highpass filter on,

the low-frequency phase drops to

nearly -90°, as it should for a capacitive system. The 4. 1t should be an easy

load for any competent power amplifier or receiver.

The continuous sine wave total

harmonic distortion (THD) of the Intermezzo 4.1t versus axial sound pressure level (SPL) in dB is shown in Fig.

7. The THD for each frequency in the

range of 20 to 80 Hz at each third octave is plotted separately in the figure.

The level was raised until the distortion became excessive or the system

could not play louder because of the

limits of its built-in amplifier. The dis-

tortion was measured in the nearfield

of the woofer and then extrapolated to

the levels generated at 1 m in a free

space. My experiences with many sub-

ISSUE NO. 28 • SUMMER/FALL 2002 19

Fig. 3: Vertical off-axis frequency responses above axis.

Fig. 2: Horizontal off-axis frequency responses.

pdf 20

Page 21

Fig. 5: Impedance magnitude.

Fig. 6: Impedance phase.

20 THE AUDIO CRITIC

Fig. 4: Vertical off-axis frequency responses below axis.

woofers using 12" to 15" diameter drivers indicate a ratio of about 28 dB be-

tween the nearfield sound pressure and

that measured in the farfield (usually 2

m ground-plane measurements, which

correspond to 1 m free-field measurements); i.e., the nearfield pressure is 28

dB louder than the farfield pressure.

Fig. 7 plots the THD values computed from the amplitude of the 2nd

to 5th harmonics as a function of the

fundamental's SPL. The figure indicates a robust bass output rising above

110 dB at distortion levels less than

10% between 40 and 80 Hz. At lower

frequencies, the distortion rises to

higher levels at correspondingly lower

fundamental SPL levels, although,

even at 25 Hz, levels above 100 dB can

be generated at distortion levels below

20%. All in all, the 4.1t's subwoofer

can reach some fairly impressive levels

in the bass range. Remember, however,

that at low frequencies in a typical listening room, subwoofers can play significantly louder due to room gain

than they can in a free-space environment without room boundaries.

Fig. 8 plots the 4.1t subwoofer's

maximum peak SPL as a function of

frequency for a transient short-term

signal, which was a shaped 6.5-cycle

tone burst. The graph represents the

loudest the sub can play for short periods of time in a narrow restricted frequency band in a free-space

environment. In-room levels will be

significantly higher. These levels are

significantly higher than the continuous sine wave levels shown previously

in Fig. 7 and represent the peak levels

that can be reached short term, using

typical program material. These data

indicate that below 40 Hz the 4.1t significantly outperformed its predecessor, the Compositions P-FR system,

as I noted in the introduction. The

bass output of the 4.1t places it solidly

in the upper third of all the systems I

have tested, including several standalone subs.

pdf 21

Page 22

Fig. 7: Woofer harmonic distortion (THD) vs. fundamental level, 20 Hz to 80 Hz.

bass level and equalization (EQ), using

their sound level meter (SLM) and

CD. My intentions were first to use

their supplied SLM and CD along

with their suggested procedure long

enough to gain familiarity with them

to report in this review, and then

switch over to my one-third-octave

real-time spectrum analyzer (an AudioControl Industrial SA-3050A) to

finish the EQ and level-setting process.

But—I was fooled! Infinity's

method worked so well I continued

using it to measure the room response

and set the built-in parametric equalizer. I only used the real-time analyzer

to set the overall bass-to-upper-range

balance. Part of the problem with

using the real-time analyzer and pink

noise (played off the Infinity CD or

the built-in noise generator) was the

variability of the band readings due to

the inherent randomness of the noise.

The R.A.B.O.S. system, in contrast,

uses sine wave warble tones, which inherently exhibit much less level variation. The warble tones, interestingly,

worked better with the real-time analyzer but of course energized only one

band at a time. The warble tones

sounded like something from a '50s

sci-fi movie, The War of the Worlds or

Forbidden Planet! The sci-fi ambience

was reinforced by the SLM, which

looked like a cross between a Star Trek

communicator and a Flash Gordon

blaster. Setting the width or Q of the

parametric equalizer was made much

simpler with Infinity's graphical

scheme, using the adjustable plastic

gizmo.

The measured bass response of

the 4.1t's in my basement listening

room exhibited a broad peak of

about 8 dB at 26 Hz as referenced to

the response between 60 and 100

Hz. When the peak was equalized

with the Intermezzo's built-in para-

metric equalizer, the bass response

was much flatter and better behaved.

The equalizer's controls, which vary

ISSUE NO. 28 • SUMMER/FALL 2002 21

Although each Infinity Intermezzo 4.1t is quite heavy at 93 lbs.,

they were relatively easy to unpack

and move around. Without spikes attached, they could be walked around

on my listening room's carpet

without much difficulty for positioning. Once set up, the 4.1t's presented a strikingly handsome

appearance with a thoroughly modern

look. With their curved and sculp-

Fig. 8: Woofer maximum peak SPL vs.

frequency.

tured metallic design and Infinity's attention to detail, they definitely did

not present the usual mundane picture of wooden rectangular boxes.

With grilles removed, the picture was

no less likable. The side-mounted

woofers had a heavy-duty, no-nonsense look that urged me to "let's turn

these babies on and see what they'll

do." The low end of the 4.1t's did not

let me down. It was like having a pair

of good subwoofers, one on both

sides of my room!

I evaluated the Intermezzos as twochannel stereo speakers and not as

home theater systems. Their performance was outstanding in almost every

area. They would perform very well in

either situation. They strongly competed with, and sometimes exceeded,

the performance of my reference

speakers, the B&W 801 Matrix Series

Ill's. I listened to them standing by

themselves as well as alongside the reference speakers in a rapid-switching

A/B comparison setup. The 4.1t's did

not require any line-level attenuation

to match the sensitivity of the reference systems. Their volume level was

essentially the same as of the B&W's

when reproducing the same broadband

program material.

I first went through Infinity's

R.A.B.O.S. procedure of setting the

pdf 22

Page 23

frequency, level, and width, are on

the front of each system, accessible

with a supplied screwdriver through

small holes.

Now to the interesting part: how

did they sound? In a word, excellent!

Interestingly, their sound was extremely close to my reference system's

on almost everything I listened to. I

often had a hard time telling which

system was playing when set up side

by side. Sometimes I couldn't believe

my A/B switch and had to walk up

close to the systems to determine

which was playing! Bass was very ex-

tended and flat; midrange was smooth

and liquid; while the highs were quite

neutral and very revealing of whatever

I played. High-frequency response

was smooth and extended, but the

highs were slightly emphasized as

compared to the B&W's, although

they did not lend an air of brusque-

ness to vocal sibilance, unlike many

systems. Soundstaging and imaging

were excellent, with a very stable

center image on mono vocal material.

The systems really shined when

played loud on complex orchestral

material with percussion. Even so, I

did notice a bit of upper-bass/lowermid congestion when I played loud

pipe organ material, as compared to

the reference systems.

The one standout sonic feature of

the Intermezzos was their excellent

bass response. They could shake the

walls and everything attached when

played at high levels with material

having sub-40-Hz content. Yeah...I

know your are supposed to track

down and eliminate all the spurious

vibrations and rattles in your listening

room, but I use them to check for the

presence of honest-to-goodness highlevel bass energy in the room. Few

systems I listen to are capable of rattling the walls; the B&Ws and the Intermezzos can easily do this.

I found myself getting out all my

favorite CDs with high-level low-bass

content to audition over the 4.1t's.

This included Telarc's Beethoven

"Wellington's Victory" (Telarc CD-

80079) with the digitally recorded

canons, the bass drum on "Ein

Straussfest" (Telarc CD-80098), the

kick drum on Spies "By Way of the

World" (particularly tracks 6 and 7,

Telarc CD-83305), the low pedals on

the organ version of the Mussorgsky

"Pictures at an Exhibition" (Dorian

DOR-90117), and the jet planes and

miscellaneous sound effects on "The

Digital Domain: A Demonstration"

(Electra 9-60303-2). The excursion of

the woofers of the 4.1t was truly scary,

a full 1.2" peak-to-peak capability.

The system really came into its

own on loud rock music with heavy

kick drum and bass guitar. I promptly

turned the 4.1t's front-mounted basslevel control up to maximum to provide concert-level bass on this

material. The 4.1t took all I could

give it while reproducing a very stimulating bass whomp that I could feel

in the pit of my stomach. There's got

to be something humorous about an

early-sixtyish loudspeaker reviewer sitting around listening to the likes of

ZZ-Top, AC-DC, and Kiss at near

concert levels to evaluate speakers. It's

fun though! Who said you couldn't

have fun with your hi-fi?

On the pink-noise stand-up/sitdown test, the 4.1t's were nearly perfect, exhibiting hardly any midrange

tonal changes when I stood up—the

full equal of the B&W 801's in this

regard. I did uncover a bit of a

problem with the Infinity's upper

bass and lower midrange when I listened to my 6.5-cycle shaped tone

bursts (the same bursts I used to

measure maximum peak SPL for Fig.

8) in an A/B comparison with the

B&W's. At 40 Hz and below the Infinity Intermezzos were the equal of

the B&W systems. Between 50 to 80

Hz, the 4.1t's could play significantly louder and cleaner than the

B&W's. However, from 100 Hz to

200 Hz, the B&W's output easily

bested the Infinity's because of the

limitations of the rather smallish 6½"

cone bass/midrange used by the 4.1t.

The 4.1t's 6½" bass/midrange has

generous excursion capability but

with its smaller area could not keep

up with the air-moving capability of

the B&W's much larger 12" bass

driver.

The 4.1t's did a particularly good

job on well-recorded female vocals,

projecting a nearly perfect, very realistic center image with no trace of

harshness or irregularities. Although

the systems shined on large-scale complex program material played loud,

they were equally at home on intimate

material such as string quartets and

other classical chamber music.

'Nuff said. I was very impressed

with the Infinity Intermezzo 4.1t's.

They performed excellently on everything I listened to, and I was particularly impressed with their bass

capability. Their imaging and soundstaging was flawless, and they could

play loudly and cleanly on complex

program material that profits from

loud playback. I much liked their

adaptability to match their listening

environment, using the built-in parametric equalizer and the easy-to-use

setup procedure with the supplied

sound level-meter and CD. Their

thoroughly modern good looks and

top performance make them naturals

for any home theater or stereo listening setup.

To get more detailed information

on the Intermezzo 4.1t's and other

Infinity systems, I suggest checking

out their Web site (listed above) and

also requesting copies of their quite

interesting and informative white papers on their method of equalizing

room effects (R.A.B.O.S.) and the

story behind their ceramic metal matrix diaphragms (C.M.M.D.).

—Don Keele

22 THE AUDIO CRITIC

pdf 23

Page 24

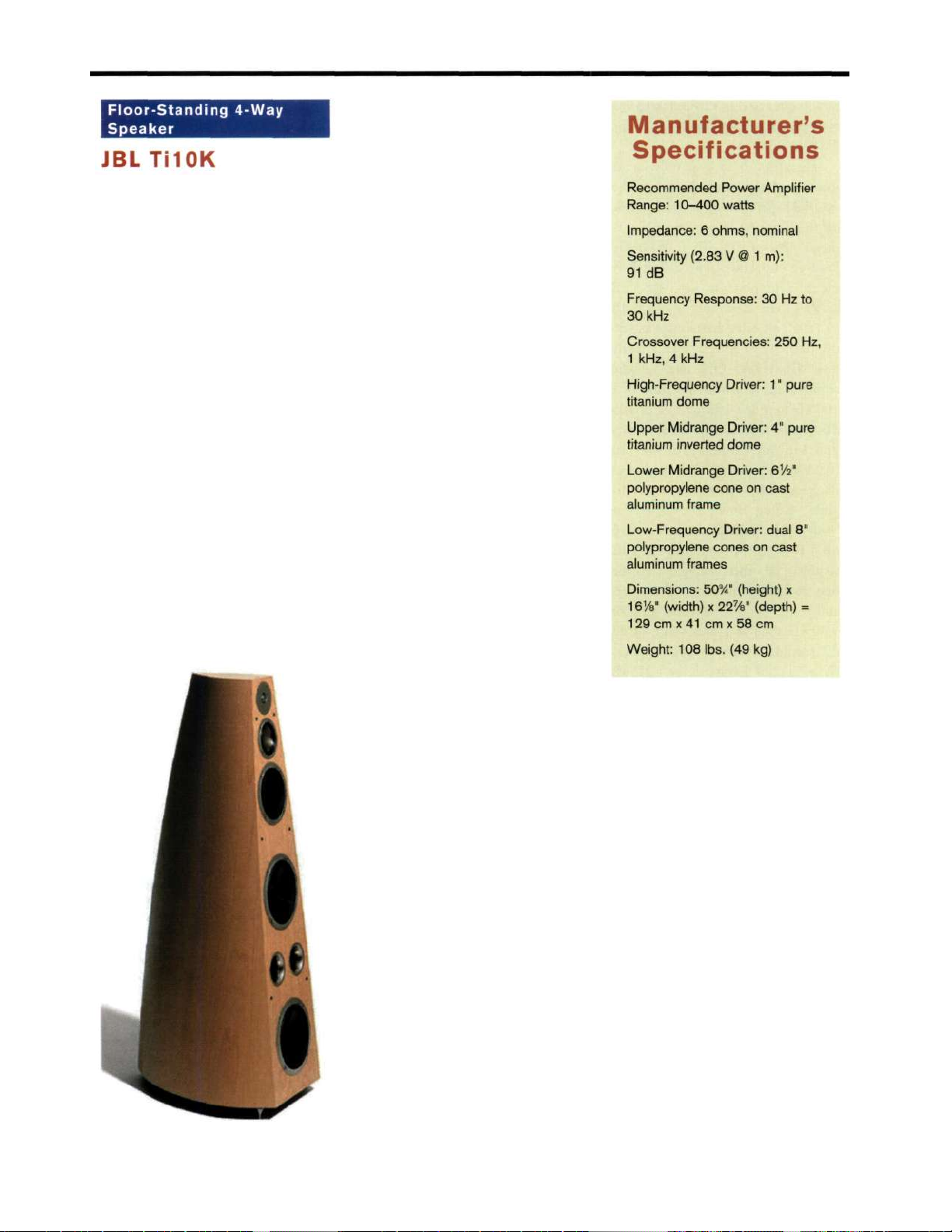

JBL Consumer Products, Inc., a Harman

International Company, 250 Crossways

Park Drive, Woodbury, NY 11797. Voice:

(516) 4963400 or (800) 6457292. Fax:

(516) 6823556. Web: www.jbl.com.

Ti10K floorstanding 4way loudspeaker

system, $7000.00 the pair. Tested sam-

ples on loan from manufacturer.

Striking in appearance, a near

miss in performance—that sums up

my take on the JBL Til0K. The five

forwardfacing drivers and two huge

bassreflex vents are certainly impressive. The Danish design of the cabinet is certainly handsome but not

very practical; all wire connections

have to be made to the bottom,

which is not particularly accessible;

the three rather than four rubber feet

make the cabinet very difficult to

slide on any surface—and let's not

The vented enclosure is tuned to

31 Hz, and the summed nearfield response of woofers and vents shows a

3 dB point at 35 Hz—not especially

impressive bass response for a huge

speaker. The woofers appear to be

crossed over lower than the manufacturer's specified frequency of 250 Hz;

the other crossover points seem to be

just about on spec. Perhaps to compensate for the phase reversal by the

apparently secondorder bass

crossover, the woofers are wired out

of phase with the other three drivers.

The impedance magnitude from 70

Hz on up is much closer to 4Ω than

the specified 6Ω, so that the specified

91 dB sensitivity is really for 2 watts

input, making the true (1 watt) efficiency 88 dB. The impedance phase

(again, above the wild gyrations at the

ISSUE NO. 28 • SUMMER/FALL 2002 23

even talk about the tweako spikes

that come in the little plastic bag.

Yes, when you're finished setting up

the Til0K's they look really nice, but

what a drag.

I played them before I measured

them because I didn't want to be influenced by the measurements one

way or the other. They sounded

bright and punchy in my room, detailed but much too aggressive. I

shudder to think what they would

have sounded like in a really live

room, my main listening room being

fairly dead. One fairly sophisticated

listener who auditioned them briefly

remarked that "it's a commercial

sound." There was more to it than

that, however, as the measurements

revealed.

The quasianechoic (MLS) frequency response on axis showed a

3.5 dB dip centering on 4 kHz and

rising response above 5 kHz, peaking

at 11 kHz (+2 to +3 dB, depending

on the where the microphone was

aimed). Moving 45° (not 30°!) off

axis horizontally, the response flattens out to ±1.5 dB up to 11 kHz

and is down only 5 dB at 17 kHz.

Furthermore, at 30° off axis vertically, the response has a very similar

profile above 6.5 kHz, although there

is a huge suckout at the approximate

uppermidtotweeter crossover point

of 3.3 kHz (which is expected).

Now, what does this mean? It means

that in the effort to achieve exceptionally flat power response into the

room, the designers goosed the on

axis frequency response, raising it far

too much above 0 dB. It would have

been better to split the difference between the onaxis and offaxis response. The onaxis response is what

you hear first; the offaxis response

reaches you with a delay. In an exceptionally dead room—a virtual

anechoic chamber—the speakers

might actually sound just right, but

not in the real world.

pdf 24

Page 25

box frequencies) is ±26°, making it a

cinch for any amplifier to drive the

Til0K.

Distortion is an issue only in the

lower midrange and the bass. The

nearfield spectrum of a 400 Hz tone

off the lower midrange driver at a 1meter SPL of 100 dB (unbearably

loud at 400 Hz) shows a 2nd harmonic components at -46 dB

(0.5%), 3rd harmonic at -55 dB

(0.18%), all other harmonics at -66

dB (0.05%) or lower. That's really

low distortion. Off one of the

woofers, the nearfield spectrum of a

100 Hz tone at a 1-meter SPL of 105

dB (again unbearably loud) shows

2nd and 3rd harmonics at -53 dB

(0.22%) and -60 dB (0.1%), respectively; all other harmonics are negligible. Going down to 60 Hz at

"only" 100 dB, 2nd harmonic is -40

dB (1%), 3rd harmonic -51 dB

(0.28%), all others negligible. At the

best summing junction of woofers

and vents, the nearfield spectrum of

a 30 Hz tone at 1-meter SPL of 88

dB (couldn't push it much higher)

shows a 2nd harmonic at -23 dB

(7%) and a 3rd harmonic at -30 dB

(3.2%), indicating that the woofers

unload in the vicinity of the tuning

frequency. Higher up the bass distortion figures are very respectable.

How can I arrive at a balanced

evaluation of the Ti10K? Its striking

cosmetics and high-tech drivers certainly make an ambitious statement.

Its midrange is flat and undistorted—and that's important. But

what about its miscalculated highfrequency response and a bass that

isn't even close to that of the $499

Hsu Research VTF-2 subwoofer (see

above)? At $3500 per side? And inconvenient to connect and to move,

on top of everything else? I can't really give a ringing endorsement to a

speaker like that, regardless of its

positive qualities.

—Peter Aczel

Monitor Audio USA, P.O. Box 1355, Buffalo, NY 14205-1355. Voice: (905) 428-

2800. Fax: (905) 428-0004. E-mail:

goldinfo@monitoraudio.com. Web:

www.monitoraudio.com. Gold Reference

10 2-way minimonitor, $1495.00 the pair.

Gold Reference Center Channel, $995.00.

Tested samples on loan from manufacturer.

Those of you who have been following my adventures in minimonitor

testing will recall that the last top of

the heap was the JosephAudio RM7si

Signature. This superseded the Monitor Audio Studio 6 (see Issue No. 20)

on my list of top dogs. Now comes the

replacement for the Studio 6's at a

little more than half the price (but

without the fancy piano-black finish).

The Gold 10's are a complete redesign. The woofer has little dimples

punched all over it—sort of an ultrahigh-tech version of the RCA LC-1,

designed by Harry Olson as his ultimate statement in the '40s and used by

RCA well into the '70s as studio monitors. The dimples are said to reduce

cone resonance, which they actually

appear to do, as we'll see below. They

are also great in allowing you to visualize the cone displacement of the

woofer at low frequencies. The speaker

also has a fixed conical metal piece affixed to the end of the pole piece. The

tweeter is still a one-inch dome but of

different design than in the Studio 6's.

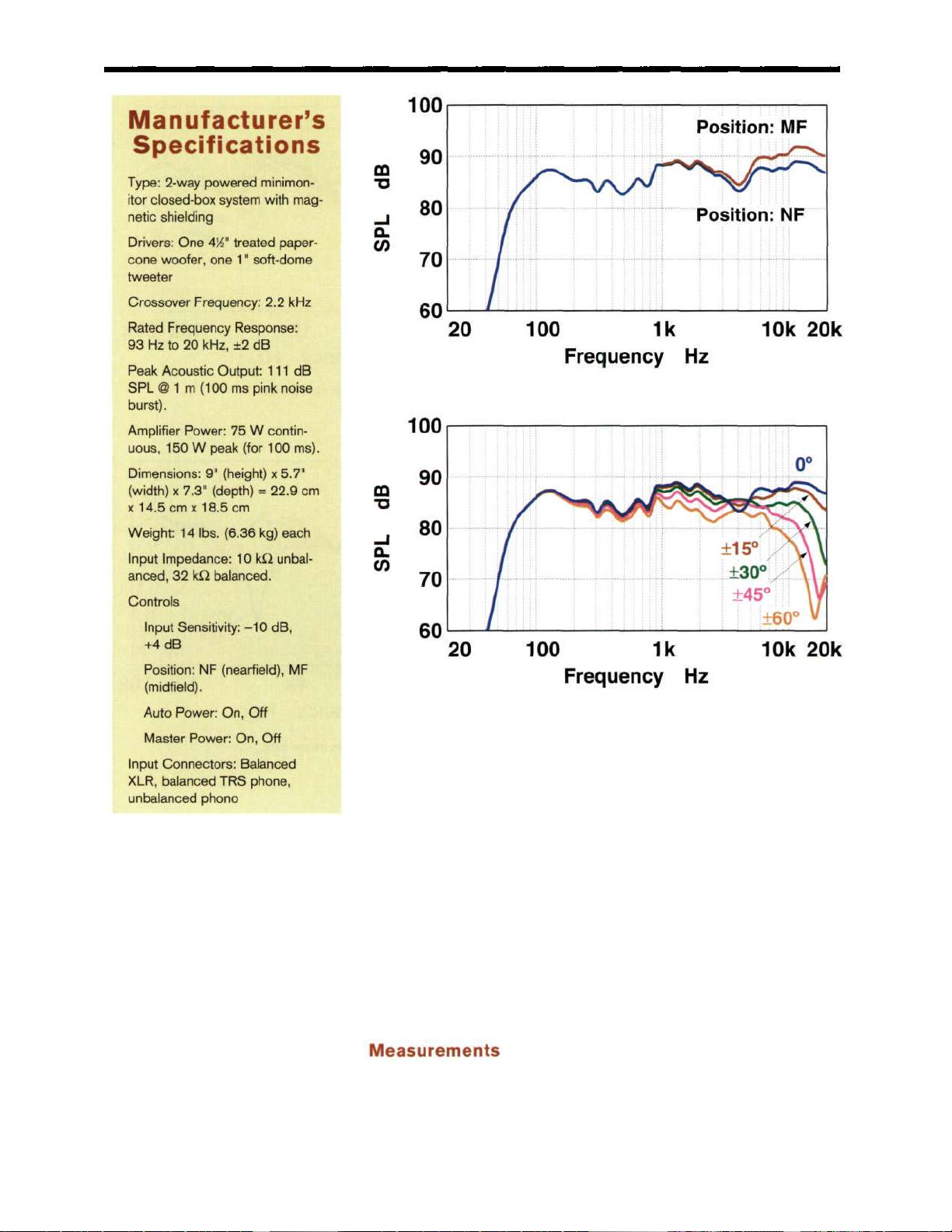

On the test bench the Studio 6 and

the Gold 10 look rather similar. Both

have a broad dip in their on-axis response between about 1.5 kHz and 5

kHz. The dip reaches a depth of 4.5

dB at 3.2 kHz in the case of the Gold

10; it is somewhat less pronounced in

the response of the Studio 6. The big

difference is a peak of about 2.5 dB at

5.3 kHz in the Studio 6's response,

whereas the Gold 10 is peak-free. The

JosephAudio RM7si Signature is far

flatter on axis than either—and dramatically flatter in its vertical off-axis

response as a result of the "Infinite

Slope" crossover. The Gold 10 develops a significant (20 dB) dip in the

2 kHz to 3 kHz range if you measure

it approximately 45° off axis vertically.

The effect is quite similar to that produced by the Monitor Audio Silver 9i

reviewed in Issue No. 27 but not

nearly as bad as with the old ACI Sapphire II of ten years ago, which had a

first-order crossover. Clearly the Gold

10's need to be well placed, so that the

tweeters are approximately at ear level,

to get good sound quality.

The horizontal off-axis response of

the Gold 10 shows good dispersion

characteristics, with the 10 kHz response almost unchanged and the 15

kHz response down 5 dB. Downstairs

in the bass the response is down 3 dB

at 43 Hz, but do not get too excited

because the 2.25% distortion point for

a 90 dB SPL at 1 meter was 80 Hz. At

70 Hz with the same SPL we were

looking at over 6% distortion and very

close to buzzing. These numbers indicate that the use of a subwoofer would

be desirable in large rooms—and not a

bad idea even in smaller rooms.

The above measurements were

taken in laboratory of The Audio

24 THE AUDIO CRITIC

pdf 25

Page 26

Critic, with the MLS (quasi-anechoic)

method at the higher frequencies and

the nearfield method in the bass. In

addition, I took some measurements

with the somewhat less precise ETF

software (see Issue No. 25) and my

own computer. The energy time

curves of the Studio 6 and the Gold 10

are also very similar, with a small

amount of energy coming at the microphone (1 meter) 1 msec after the

initial impulse. This energy is 20 dB

down. The JosephAudio RM7si Signature, by contrast, shows some thickening of the impulse curve, but no

discrete event can be observed.

Waterfall plots are more revealing.

The Studio 6 has a big resonance just

above 5 kHz, occurring exactly where

the frequency response peak is. The

Gold 10 also shows a small resonance

in this frequency region but it is down

about 18 dB in comparison with the

Studio 6. The Infinite Slope crossover

of the JosephAudio produces significantly more energy in the waterfall and

cumulative spectral energy plots. A resonance at 5 kHz, which appears to be

coming from the woofer, is also present. The high-order crossover of this

speaker keeps the overall energy contribution of the woofer resonance to a

much smaller value than is the case

with the Studio 6. A new version of

the RM7 (not tested yet) has a

crossover which is said to reduce the

energy storage at the crossover region.

So—what do they sound like? The

Studio 6 and the Gold 10 sound a lot

less alike than the measurements suggest. The Gold 10 appears to have a bit

more tweeter level and it does benefit

from a slight reduction of the treble

control, at least in stereo. At first the

Studio 6's sound more alive and detailed, but after extensive listening one

comes to understand this is a coloration, perhaps related to the woofer

resonance. The Gold 10's emerge as

cleaner and much more relaxed and

natural-sounding after extensive lis-

ISSUE NO. 28 • SUMMER/FALL 2002 25

tening to both speakers side by side.

Choosing between the Gold 10 and

the RM7si Signature is much harder.

The JosephAudio is much easier to

place and get good sound out of because of its much smoother response

across vertical axis changes. This may

also help in giving a flat power response

into the room. On the other hand, the

JosephAudio appears to have an upper

midrange emphasis or coloration.

Could this be the woofer resonance or

the energy storage effects in the

crossover? In any case, a properly

placed Gold 10 with the treble control

slightly reduced gave a remarkable

sense of the sound of real instruments.

This remained true even when things

got complex, which on some other

minimonitors could lead to harshness,