Page 1

Also in this issue:

Loudspeakers, including a $229 system that sounds like $15,000

(but don't buy it for your listening room).

Power amplifiers, D/A converters, AV electronics, a TV, and more.

Plus our regular features, columns, letters to the

Editor, CD and DVD reviews—and our new look!

Biggest

Lies in

Audio

The

ISSUE NO. 26

Display until arrival

of Issue No. 27.

Retail price: U.S. $7.50, Can. $8.50

pdf 1

Page 2

The 10 Biggest Lies in Audio

By Peter Aczel

Four Speaker Systems, Ranging from

the Most Ambitious to the Most Ingenious

By Peter Aczel

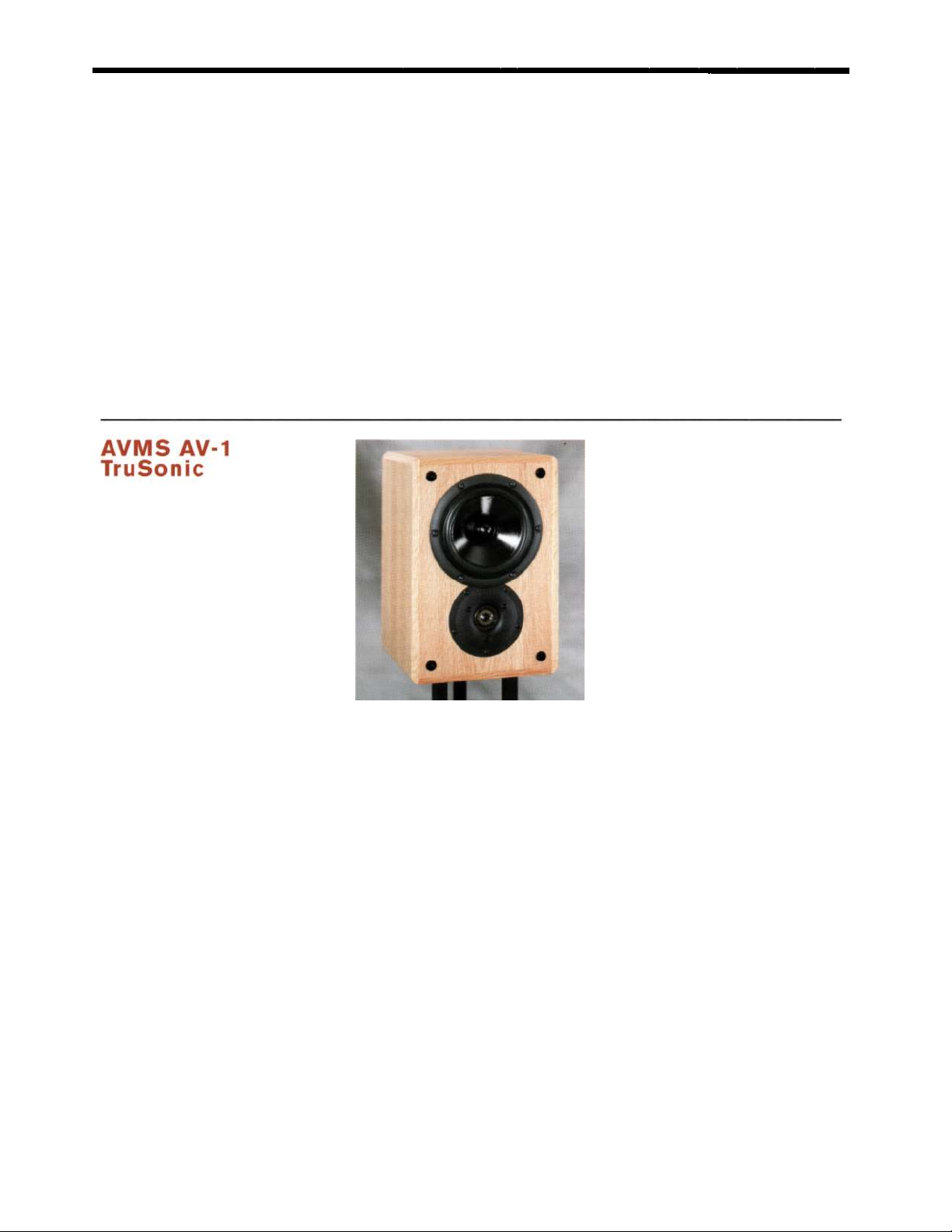

AVMS AV-1 TruSonic 10

EgglestonWorks "Isabel" 12

Monsoon MM-1000 13

Revel "Salon" 14

Power Amplifiers and Outboard D/A Converters

By Peter Aczel, David A. Rich, Ph.D., and Glenn O. Strauss

5-Channel Power Amplifier: Bryston 9B ST 19

Mono Power Amplifier: Bryston PowerPac 60 20

Outboard D/A Converters: Entech NC205.2/NC203.2 20

Outboard D/A Converter: MSB Technology "Link" 21

5-Channel Power Amplifier: Sherbourn 5/1500 23

Outboard D/A Converter: Van Alstine Omega IV DAC 27

Can a Car Radio Outperform a

High-End FM Tuner?

Blaupunkt Alaska RDM 168 22

Do You Need a Spectrum Analyzer?

By Glenn O. Strauss

AudioControl Industrial SA-3052 26

Direct Stream Digital and the "Super Audio CD"

By Peter Aczel

Sony SCD-1 33

High-Tech Gear for Your TV Room

(a.k.a. Home Theater)

By Peter Aczel and David A. Rich, Ph.D.

DVD Video Player: Denon DVD-5000 35

Personal TV System: ReplayTV 2020 36

DVD Video Player: Toshiba SD-5109 38

Rear Projection TV: Toshiba TW40X81 38

It Never Gets Better By Tom Nousaine 40

Capsule CD Reviews By Peter Aczel 41

DVD Reviews By Glenn O. Strauss 45

Box 978: Letters to the Editor 3

ISSUE NO. 26 • FALL 2000 1

contents

pdf 2

Page 3

From the

2 THE AUDIO CRITIC

Publisher

Greg Keilty

Editor

Peter Aczel

Technical Editor David A. Rich

Contributing Editor Glenn O. Strauss

Technical Consultant (RF) Richard T. Modafferi

Columnist Tom Nousaine

Art Director Michele Raes

Design and Prepress Tom Aczel

Business Manager Bodil Aczel

Advertising Manager David Webster

The Audio Critic® (ISSN 0146-4701) is published quarterly for $24 per year by Critic Publications, Inc., 1380

Masi Road, Quakertown, PA 18951-5221, in partnership

with The CM Group, 74 Elsfield Road, Toronto, Ontario

M8Y 3R8, Canada. Second-class postage paid at Quakertown, PA. Postmaster: Send address changes to The

Audio Critic, P.O. Box 978, Quakertown, PA 18951-0978.

Any conclusion, rating, recommendation, criticism, or

caveat published by The Audio Critic represents the

personal findings and judgments of the Editor and the

Staff, based only on the equipment available to their

scrutiny and on their knowledge of the subject, and is

therefore not offered to the reader as an infallible truth nor

as an irreversible opinion applying to all extant and forthcoming samples of a particular product. Address all editorial correspondence to The Editor, The Audio Critic, P.O.

Box 978, Quakertown, PA 18951-0978.

Contents of this issue copyright © 2000 by Critic Publications, Inc. All rights reserved under international and

Pan-American copyright conventions. Reproduction in

whole or in part is prohibited without the prior written permission of the Editor. Paraphrasing of product reviews for

advertising or commercial purposes is also prohibited

without prior written permission. The Audio Critic will

use all available means to prevent or prosecute any such

unauthorized use of its material or its name.

Subscription Information and Rates

You may use the postcard bound between pages 40 and

41 or, if you wish, simply write your name and address as

legibly as possible on any piece of paper. Preferably print

or type. Enclose with payment. That's all. We also accept

VISA, MasterCard, and Discover, either by mail, by telephone, or by fax.

We currently have only two subscription rates. If you live

in the U.S. or Canada, you pay $24 for four quarterly issues. If you live in any other country, you pay $38 for a

four-issue subscription by airmail. All payments from

abroad, including Canada, must be in U.S. funds, collectable in the U.S. without a service charge.

You may start your subscription with any issue, although

we feel that new subscribers should have a few back issues to gain a better understanding of what The Audio

Critic is all about. We still have Issues No. 11, 13, and 16

through 25 in stock. Issues earlier than No. 11 are now

out of print, as are No. 12, No. 14, and No. 15. Specify

which issues you want (at $24 per four). Please note that

we don't sell single issues by mail. You'll find those at

somewhat higher cost at selected newsdealers, bookstores, and audio stores.

Address all subscriptions to:

The Audio Critic, P.O. Box 978,

Quakertown, PA 18951-0978.

VISA/MasterCard/Discover: (215) 538-9555

Fax: (215) 538-5432

What Did I Tell You?

Issue after inevitably delayed issue, I have been talking

about our need to form a partnership with a publisher. Not just

any publisher but one that could help us publish regularly and

profitably without interfering with our editorial policy. Well, I

have found such a publisher, and you are holding the earliest

fruit of our partnership in your hand. Looks a lot more majorleague, doesn't it? More importantly, it will be followed by the

next issue, and the one after that, and all the others after that,

at quarterly intervals, as originally intended. We are even

talking about a bimonthly schedule in a year or two.

Our new partner is The CM Group, based in Toronto

(haven't I always professed Canadophilia?) and headed by Greg

Keilty, a widely recognized circulation expert. I have retained

complete editorial autonomy. This publication will remain a

consumer advocate and not one of the compliant handmaidens

of the audio industry. You will notice that in this issue we are,

to some extent, still playing catch-up because we had to clear

our pipeline of accumulated products that had been submitted

for review. That will no longer be the case in our next issue.

My only worry is that some of our readers have become accustomed to our former double issues for the price of one—

overstuffed out of guilt by your forever tardy Editor—and will

now want the same bargain every 90 days. Sorry, guys, that

may have been a bonanza for you, but it was a hell of a way to

run a magazine. Greg won't stand for it.

pdf 3

Page 4

to the Editor

Our fresh start with our new publisher, after the long interruption of our publishing schedule, leaves us with very few letters that are still of current relevance.

The two below, from two of the most distinguished names in audio, remain required reading. Write us letters like that and there will be more pages again in

this column. Address all editorial correspondence to the Editor, The Audio Critic,

P.O. Box 978, Quakertown, PA 18951-0978.

The Audio Critic:

Thank you kindly for sending the

most recent issue of The Audio Critic. I al-

ways enjoy reading your nice little magazine. It is a pleasure to see that you have

managed after all these years to continue

to speak the truth and keep your sense of

proportion and humor.

I noticed your quest for a solution to

"One Last Mystery." Though I trust there

are more mysteries to come, I have wondered about the same matter over the

years and thought I would make a few

comments about it.

I have many time said that there are so

many more fakes and frauds in the audio

area than in many others, each of which

should raise the same amount of passion.

I am not familiar with the automotive

field but I am very familiar with photography. There are two aspects to the relative

sanity in the area of photography as compared to audio. One of the issues has to do

with the ability of persons to make equipment and the other with the ability of persons to compare the performance of the

equipment.

On the first issue, I would suggest

that it is all but impossible for the photographic equipment field to be flooded

with equipment designed by incompetents, fakes, and frauds, as is the case for

audio equipment, because it is so difficult to do so. Anyone, qualified or not,

can purchase the components necessary

to make some sort of amplifier or preamplifier that will work, more or less.

Anyone can put this stuff together with

even minimal competence. There are

magazines that describe construction and

supply houses that provide the parts and

instructions to make loudspeakers and

electronics and so forth. There is in

electronics and audio a long tradition,

starting with the amateur radio groups,

to build stuff. As a result, stuff is indeed

built, and some go so far as to polish and

glitz up their stuff, market it with technical drivel, and take in the suckers.

This is not so in the field of photography. There are no cameras being built

by amateurs. There are no camera parts

supply houses. There are no lens grinding

kits and shutter parts vendors. There is no

tradition of building a camera from parts.

So, as we might expect, there are no purveyors of odd or silly cameras. Every photographer knows better than to be taken

in by an advertisement for some sort of

special super camera that would have

magical properties. They know that such

things are indeed silly.

As a result, photography is relatively

free of fakes and frauds who push equipment with special properties, compared to

the audio field. Photographers work at

taking pictures, just as audio professionals

work at making recordings.

There is another issue that I think is

just as important, possibly more important. Photographic results are much

more definitive and easier to compare

than are audio results. This effect is

caused by basic human perceptions that

are used to compare and evaluate the

final results of audio reproduction and

photographic presentation.

In the first case, the ear is the perceiver

and the mind the interpreter of the audio

result. In the latter the eye is the perceiver

and the mind the interpreter of the photographic result. There is a basic difference

between these two processes. In the first

case a time-sequential comparison is

made, and in the second the comparison

can be and usually is simultaneous. Be-

cause of the time-sequential comparison

in the case of audio presentations, judgment is less precise and more easily biased

by opinion. One has to jump back and

forth between comparisons in the audio

case, and this fuzzes up the ability to

judge. One cannot hear both presenta-

tions at the same time. It is true that A/B

or ABX comparisons have been quite successful in ferreting out differences and

pinning down differences. But there are

still those who choose to believe what they

want to, regardless of the truth. One can

only hope to show that these persons really can't tell the difference, if any, and

show them up for what they are, frauds.

In the case of photographic performance, the comparisons of photographic

results are done simultaneously. That is,

side by side but at the same time. When

simultaneous comparisons are made, the

differences, if any, are observed and can be

discussed by the viewers while doing the

examination. The language of comparison

then becomes very precise and the viewers

can interact quickly, in real time, to move

toward a resolution of differences of opinions. This sort of interaction cannot take

place in audio comparisons. Thus differences of opinion often remain unresolved.

I believe that for at least the two reasons stated above, and possibly others,

there is a significant difference between the

audio and photographic fields, which will

continue. Photography will remain relatively free of fakes and frauds, while audio

will continue to be replete with them.

Sincerely,

R. A. Greiner

Emeritus Professor of Electrical and

Computer Engineering

Madison, WI

(continued on page 34)

ISSUE NO. 26 • FALL 2000 3

pdf 4

Page 5

4 THE AUDIO CRITIC

The punch line of Lincoln's famous bon mot,

that you cannot fool all the people all of the

time, appears to be just barely applicable to

high-end audio. What follows here is an

attempt to make it stick.

I strongly suspect that people are

more gullible today than they were in

my younger years. Back then we didn't

put magnets in our shoes, the police

didn't use psychics to search for

missing persons, and no head of state

since Hitler had consulted astrologers.

Most of us believed in science without

any reservations. When the hi-fi era

dawned, engineers like Paul Klipsch,

Lincoln Walsh, Stew Hegeman, Dave

Hafler, Ed Villchur, and C. G.

McProud were our fountainhead of

audio information. The untutored

tweako/weirdo pundits who don't

know the integral of ex were still in the

benighted future.

Don't misunderstand me. In terms

of the existing spectrum of knowledge,

the audio scene today is clearly ahead of

the early years; at one end of the spectrum there are brilliant practitioners

who far outshine the founding fathers.

At the dark end of that spectrum, how-

ever, a new age of ignorance, superstition, and dishonesty holds sway. Why

and how that came about has been

amply covered in past issues of this

publication; here I shall focus on the

rogues' gallery of currently proffered

mendacities to snare the credulous.

Logically this is not the lie to start with

because cables are accessories, not primary audio components. But it is the

hugest, dirtiest, most cynical, most in-

telligence-insulting and, above all, most

fraudulently profitable lie in audio, and

therefore must go to the head of the list.

The lie is that high-priced speaker

cables and interconnects sound better

than the standard, run-of-the-mill (say,

Radio Shack) ones. It is a lie that has

been exposed, shamed, and refuted

over and over again by every genuine

authority under the sun, but the

tweako audio cultists hate authority

and the innocents can't distinguish it

from self-serving charlatanry.

The simple truth is that resistance,

inductance, and capacitance (R, L, and

C) are the only cable parameters that

affect performance in the range below

radio frequencies. The signal has no

idea whether it is being transmitted

through cheap or expensive RLC. Yes,

you have to pay a little more than rock

bottom for decent plugs, shielding, insulation, etc., to avoid reliability problems, and you have to pay attention to

resistance in longer connections. In

basic electrical performance, however,

a nice pair of straightened-out wire

coat hangers with the ends scraped is

not a whit inferior to a $2000 gee-whiz

miracle cable. Nor is 16-gauge lamp

cord at 18¢ a foot. Ultrahigh-priced

cables are the biggest scam in consumer electronics, and the cowardly

surrender of nearly all audio publications to the pressures of the cable marketers is truly depressing to behold.

(For an in-depth examination of

fact and fiction in speaker cables and

audio interconnects, see Issues No. 16

and No. 17.)

pdf 5

Page 6

This lie is also, in a sense, about a pe-

ripheral matter, since vacuum tubes are

hardly mainstream in the age of silicon. It's an all-pervasive lie, however,

in the high-end audio market; just

count the tube-equipment ads as a percentage of total ad pages in the typical

high-end magazine. Unbelievable! And

so is, of course, the claim that vacuum

tubes are inherently superior to transistors in audio applications—don't

you believe it.

Tubes are great for high-powered

RF transmitters and microwave ovens

but not, at the turn of the century, for

amplifiers, preamps, or (good grief!)

digital components like CD and DVD

players. What's wrong with tubes?

Nothing, really. There's nothing wrong

with gold teeth, either, even for upper

incisors (that Mideastern grin); it's just

that modern dentistry offers more attractive options. Whatever vacuum

tubes can do in a piece of audio equipment, solid-state devices can do better,

at lower cost, with greater reliability.

Even the world's best-designed tube

amplifier will have higher distortion

than an equally well-designed transistor

amplifier and will almost certainly need

more servicing (tube replacements,

rebiasing, etc.) during its lifetime. (Idiotic designs such as 8-watt single-ended

triode amplifiers are of course exempt,

by default, from such comparisons since

they have no solid-state counterpart.)

As for the "tube sound," there are

two possibilities: (1) It's a figment of

the deluded audiophile's imagination,

or (2) it's a deliberate coloration introduced by the manufacturer to appeal

to corrupted tastes, in which case a

solid-state design could easily mimic

the sound if the designer were perverse

enough to want it that way.

Yes, there exist very special situations

where a sophisticated designer of hi-fi

electronics might consider using a tube

(e.g., the RF stage of an FM tuner), but

those rare and narrowly qualified exceptions cannot redeem the common,

garden-variety lies of the tube marketers, who want you to buy into an obsolete technology.

You have heard this one often, in one

form or another. To wit: Digital sound

is vastly inferior to analog. Digitized

audio is a like a crude newspaper photograph made up of dots. The

Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem is

all wet. The 44.1 kHz sampling rate of

the compact disc cannot resolve the

highest audio frequencies where there

are only two or three sampling points.

Digital sound, even in the best cases, is

hard and edgy. And so on and so

forth—all of it, without exception, ignorant drivel or deliberate misrepresentation. Once again, the lie has little

bearing on the mainstream, where the

digital technology has gained complete

acceptance; but in the byways and tributaries of the audio world, in unregenerate high-end audio salons and the

listening rooms of various tweako

mandarins, it remains the party line.

The most ludicrous manifestation of

the antidigital fallacy is the preference

for the obsolete LP over the CD. Not

the analog master tape over the digital

master tape, which remains a semirespectable controversy, but the clicks,

crackles and pops of the vinyl over the

digital data pits' background silence,

which is a perverse rejection of reality.

Here are the scientific facts any

second-year E.E. student can verify for

you: Digital audio is bulletproof in a

way analog audio never was and never

can be. The 0's and l's are inherently

incapable of being distorted in the

signal path, unlike an analog waveform. Even a sampling rate of 44.1

kHz, the lowest used in today's high-fi-

delity applications, more than adequately resolves all audio frequencies.

It will not cause any loss of information in the audio range—not an iota,

not a scintilla. The "how can two sampling points resolve 20 kHz?" argument is an untutored misinterpretation

of the Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem. (Doubters are advised to take an

elementary course in digital systems.)

The reason why certain analog

recordings sound better than certain

digital recordings is that the engineers

did a better job with microphone

placement, levels, balance, and equalization, or that the recording venue

was acoustically superior. Some early

digital recordings were indeed hard

and edgy, not because they were digital

but because the engineers were still

thinking analog, compensating for anticipated losses that did not exist.

Today's best digital recordings are the

best recordings ever made. To be fair, it

must be admitted that a state-of the-art

analog recording and a state-of-the-art

digital recording, at this stage of their

respective technologies, will probably

be of comparable quality. Even so, the

number of Tree-Worshiping Analog

Druids is rapidly dwindling in the professional recording world. The digital

way is simply the better way.

Regular readers of this publication

know how to refute the various lies invoked by the high-end cultists in opposition to double-blind listening tests

at matched levels (ABX testing), but a

brief overview is in order here.

The ABX methodology requires

device A and device B to be levelmatched within +0.1 dB, after which

you can listen to fully identified A and

fully identified B for as long as you

like. If you then think they sound different, you are asked to identify X,

ISSUE NO. 26 • FALL 2000

5

pdf 6

Page 7

6 THE AUDIO CRITIC

which may be either A or B (as deter-

mined by a double-blind randomization process). You are allowed to make

an A/X or B/X comparison at any

time, as many times as you like, to decide whether X=A or X=B. Since sheer

guessing will yield the correct answer

50% of the time, a minimum of 12

trials is needed for statistical validity

(16 is better, 20 better yet). There is no

better way to determine scientifically

whether you are just claiming to hear a

difference or can actually hear one.

The tweako cultists will tell you

that ABX tests are completely invalid.

Everybody knows that a Krell sounds

better than a Pioneer, so if they are indistinguishable from each other in an

ABX test, then the ABX method is all

wet—that's their logic. Everybody

knows that Joe is taller than Mike, so if

they both measure exactly 5 feet 11¼

inches, then there is something wrong

with the Stanley tape measure, right?

The standard tweako objections to

ABX tests are too much pressure (as in

"let's see how well you really hear"),

too little time (as in "get on with it, we

need to do 16 trials"), too many de-

vices inserted in the signal path (viz.,

relays, switches, attenuators, etc.), and

of course assorted psychobabble on the

subject of aural perception. None of

that amounts to anything more than a

red herring, of one flavor or another, to

divert attention from the basics of controlled testing. The truth is that you

can perform an ABX test all by yourself without any pressure from other

participants, that you can take as much

time as wish (how about 16 trials over

16 weeks?), and that you can verify the

transparency of the inserted control

devices with a straight-wire bypass.

The objections are totally bogus and

hypocritical.

Here's how you smoke out a lying,

weaseling, obfuscating anti-ABX hypocrite. Ask him if he believes in any

kind of A/B testing at all. He will

probably say yes. Then ask him what

This widely reiterated piece of B.S.

would have you believe that audio

electronics, and even cables, will

"sound better" after a burn-in period

of days or weeks or months (yes,

months). Pure garbage. Capacitors will

"form" in a matter of seconds after

power-on. Bias will stabilize in a

matter of minutes (and shouldn't be all

that critical in well-designed equipment, to begin with). There is absolutely no difference in performance

between a correctly designed amplifier's (or preamp's or CD player's) first-

Even fairly sophisticated audiophiles

fall for this hocus-pocus. What's more,

loudspeaker manufacturers participate

in the sham when they tell you that

those two pairs of terminals on the

back of the speaker are for biwiring as

well as biamping. Some of the most

highly respected names in loudspeakers

are guilty of this hypocritical genuflection to the tweako sacraments—

they are in effect surrendering to the

"realities" of the market.

The truth is that biamping makes

sense in certain cases, even with a passive

crossover, but biwiring is pure voodoo.

If you move one pair of speaker wires to

the same terminals where the other pair

is connected, absolutely nothing changes

electrically. The law of physics that says

so is called the superposition principle.

In terms of electronics, the superposition

theorem states that any number of voltages applied simultaneously to a linear

network will result in a current which is

the exact sum of the currents that would

result if the voltages were applied indi-

vidually. The audio salesman or 'phile

who can prove the contrary will be an

instant candidate for some truly major

scientific prizes and academic honors. At

hour and l000th-hour performance.

As for cables, yecch... We're dealing

with audiophile voodoo here rather

than science. (See also the Duo-Tech

review in Issue No. 19, page 36.)

Loudspeakers, however, may require a break-in period of a few hours,

perhaps even a day or two, before

reaching optimum performance. That's

because they are mechanical devices

with moving parts under stress that

need to settle in. (The same is true of

reciprocating engines and firearms.)

That doesn't mean a good loudspeaker

won't "sound good" right out of the

box, any more than a new car with 10

miles on it won't be good to drive.

special insights he gains by (1) not

matching levels and (2) peeking at

the nameplates. Watch him squirm

and fume.

Negative feedback, in an amplifier or

preamplifier, is baaaad. No feedback at

all is gooood. So goes this widely invoked untruth.

The fact is that negative feedback is

one of the most useful tools available to

the circuit designer. It reduces

distortion and increases stability. Only

in the Bronze Age of solid-state amplifier design, back in the late '60s and

early '70s, was feedback applied so

recklessly and indiscriminately by certain practitioners that the circuit could

get into various kinds of trouble. That

was the origin of the no-feedback

fetish. In the early '80s a number of

seminal papers by Edward Cherry

(Australia) and Robert Cordell (USA)

made it clear, beyond the shadow of a

doubt, that negative feedback is totally

benign as long as certain basic guidelines are strictly observed. Enough time

has elapsed since then for that truth to

sink in. Today's no-feedback dogmatists

are either dishonest or ignorant.

pdf 7

Page 8

the same time it is only fair to point out

that biwiring does no harm. It just

doesn't do anything. Like magnets in

your shoes.

Just about all that needs to be said on

this subject has been said by Bryston in

their owner's manuals:

"All Bryston amplifiers contain

high-quality, dedicated circuitry in the

power supplies to reject RF, line spikes

and other power-line problems. Bryston

power amplifiers do not require specialized power line conditioners. Plug the

amplifier directly into its own wall

socket."

What they don't say is that the same

is true, more or less, of all well-designed

amplifiers. They may not all be the Brystons' equal in regulation and PSRR, but

if they are any good they can be plugged

directly into a wall socket. If you can afford a fancy power conditioner you can

also afford a well-designed amplifier, in

which case you don't need the fancy

power conditioner. It will do absolutely

nothing for you. (Please note that we

aren't talking about surge-protected

power strips for computer equipment.

They cost a lot less than a Tice Audio

magic box, and computers with their peripherals are electrically more vulnerable

than decent audio equipment.)

The biggest and stupidest lie of

them all on the subject of "clean" power

is that you need a specially designed

high-priced line cord to obtain the best

possible sound. Any line cord rated to

handle domestic ac voltages and currents will perform like any other. Ultrahigh-end line cords are a fraud. Your

audio circuits don't know, and don't

care, what's on the ac side of the power

transformer. All they're interested in is

the dc voltages they need. Think about

it. Does your car care about the hose

you filled the tank with?

This goes back to the vinyl days, when

treating the LP surface with various

magic liquids and sprays sometimes

(but far from always) resulted in improved playback, especially when the

pressing process left some residue in the

grooves. Commercial logic then

brought forth, in the 1980s and '90s,

similarly magical products for the treatment of CDs. The trouble is that the

only thing a CD has in common with

an LP is that it has a surface you can

put gunk on. The CD surface, however, is very different. Its tiny indentations do not correspond to analog

waveforms but merely carry a numerical code made up of 0's and l's. Those

0's and l's cannot be made "better" (or

"worse," for that matter) the way the

undulations of an LP groove can sometimes be made more smoothly trackable. They are read as either 0's or l's,

and that's that. You might as well polish

a quarter to a high shine so the cashier

won't mistake it for a dime.

Just say no to CD treatments,

from green markers to spray-ons and

rub-ons. The idiophiles who claim to

hear the improvement can never,

never identify the treated CD blind.

(Needless to say, all of the above also

goes for DVDs.)

This is the catchall lie that should perhaps go to the head of the list as No.

1 but will also do nicely as a wrap-up.

The Golden Ears want you to believe

that their hearing is so keen, so ex-

quisite, that they can hear tiny nu-

ances of reproduced sound too elusive

for the rest of us. Absolutely not true.

Anyone without actual hearing im-

pairment can hear what they hear, but

only those with training and experience know what to make of it, how to

interpret it.

Thus, if a loudspeaker has a huge

dip at 3 kHz, it will not sound like

one with flat response to any ear,

golden or tin, but only the experi-

enced ear will quickly identify the

problem. It's like an automobile mechanic listening to engine sounds and

knowing almost instantly what's

wrong. His hearing is no keener than

yours; he just knows what to listen for.

You could do it too if you had dealt

with as many engines as he has.

Now here comes the really bad

part. The self-appointed Golden

Ears—tweako subjective reviewers,

high-end audio-salon salesmen, audioclub ringleaders, etc.—often use their

falsely assumed superior hearing to intimidate you. "Can't you hear that?"

they say when comparing two amplifiers. You are supposed to hear huge

differences between the two when in

reality there are none—the GE's can't

hear it either; they just say they do, relying on your acceptance of their GE

status. Bad scene.

The best defense against the Golden

Ear lie is of course the double-blind

ABX test (see No. 4 above). That sepa-

rates those who claim to hear something

from those who really do. It is amazing

how few, if any, GE's are left in the

room once the ABX results are tallied.

There are of course more Big Lies in

audio than these ten, but let's save a few

for another time. Besides, it's not really

the audio industry that should be

blamed but our crazy consumer culture

coupled with the widespread acceptance

of voodoo science. The audio industry,

specifically the high-end sector, is merely

responding to the prevailing climate. In

the end, every culture gets exactly what

it deserves.

ISSUE NO. 26 • FALL 2000

7

pdf 8

Page 9

Four Speaker Systems, Ranging

from the Most Ambitious to

the Most Ingenious

L

et me digress briefly before addressing my intended main

themes in the individual reviews.

I am always worried that new readers of

this publication might not be aware of

the dominant role of the loudspeaker in

any audio system. Upgrading your

speakers has the potential to change

your audio life, to take you into a new

world of sound; upgrading your electronics will not have anywhere near the

same effect—if any.

I dwelled on this subject at some

length in Issue No. 25 (see pp. 15-16);

here I only want to remind you that

your money is more wisely spent on

new speakers than on any other audio

component. That does not mean I endorse loudspeaker systems in the $20Kand-up category (which extends to

$100K and more). The vast majority of

those insanely high-priced speakers

aren't worth 25 cents on the dollar;

many of them are just plain rip-offs.

On the other hand, you shouldn't expect the $5000 kind of sound out of

$500-a-pair loudspeakers. Truly good

speakers are never cheap. That becomes

even more of an issue with multichannel home-theater systems. (Again,

see Issue No. 25, pp. 16-17.)

My highest recommendation to

those who are willing to spend serious

bucks on a speaker system remains the

Canadian Waveform Mach 17, now

$8495 the pair direct from the factory.

So far I have not found its equal in

transparency and lack of coloration.

Yes, you need a 6-channel power amplifier to use a pair of Mach 17's with

their dedicated 3-way electronic

crossover, and that raises the cost considerably, but then you have something you can live with for years

without the urge to upgrade. Of

course, something in the $1500 to

$2000 range will also get you excellent

speaker performance if you shop

wisely (as our regular readers presumably do); just don't expect the highest

degree of refinement.

While I am digressing I should also

mention that some time ago I auditioned a preproduction version of the

new Infinity "Interlude" IL40 floorstanding 3-way system at only $998

the pair and was amazed by the undeniably "high-end" sound. It was not on

my own turf and far from a complete

laboratory test, so this does not constitute a recommendation until they send

me review samples. Even so, you

should be aware of a whole new family

of Infinity and JBL speakers (both are

Harman International brands) representing the long-awaited fruition of

Floyd Toole's guidelines. (See Issue No.

24, p. 13.) The speakers range from

quite inexpensive to very-but-not-illogically expensive and show some

promise of taking the performanceper-dollar index to a new level, mainly

as a result of a proprietary diaphragm

technology (aluminum sandwiched between two layers of ceramic). Most of

the models are just beginning to show

up in the stores as I write this, so it's

still a waiting game.

In general, new chemistry (i.e., materials science) appears to result in

more immediate improvements in

loudspeaker design than new physics

(i.e., exotic transducer principles). The

good old moving-coil driver with a

better diaphragm looks like the way to

go for a while longer. Having said that,

I still want to call your attention to a

very interesting transducer develop-

ment, the distributed-mode loudspeaker (DML) pioneered by NXT, a

U.K.-based outfit with serious techno-

logical and financial resources (i.e., not

a basement operation run by tweaks).

ISSUE NO. 26 • FALL 2000

9

pdf 9

Page 10

The DML is simply a flat panel, of

almost any desired size but very stiff,

with a complex bending behavior in

response to electroacoustic excitation.

It produces sound by breaking up into

a large number of seemingly random-

ized vibrational modes over its entire

surface. In other words, it is just the

opposite of the perfect piston, res-

onating in many segments and totally

lacking coherence. The amazing thing

is that it measures flat and sounds

quite accurate. It would appear that a

few resonances are bad but lots of

random resonances are good. That co

Audio Video Multimedia Solutions, 17

Saddleback Court, O'Fallon, MO 63366.

Voice and Fax: (636) 9788173. Email:

tonyscimemiAVMS@worldnet.att.net. AV1

TruSonic minimonitor/satellite, $900.00

the pair. Tested samples on loan from

manufacturer.

What we have here is the main

building block of a complete surround

system, used for the front left/right as

well as the rear left/right channels. The

centerchannel speaker (AVC Tru-

Sonic, $750.00) is not reviewed here

because it is essentially the same

speaker with dual woofers. (Besides, we

are planning a comprehensive center

channel survey in an upcoming issue.)

Nor is the powered subwoofer AVMS

sent me reviewed here because it is not

the final version that will be sold with

the system. The AV1 is of course the

unit on which the overall quality of the

5.1 (or 5.2) system depends.

For the money, and then some, this

is a very nicely built little speaker. My

review samples came in black oak ve-

neer and appear very professionally fin-

ished. All edges and corners are

rounded, albeit with a small radius.

The back and the bottom are also ve-

neered. The driver complement con-

sists of a 5½inch woofer and a 1inch

herence is under most circumstances a

nonissue has been explained to our

readers a number of times. The DML

is a genuinely different approach to

transducer design which would need

too many pages here to be explained

completely; furthermore, its current

implementations are all nonhifi and

thus not really grist for our mill. There

exists the promise, however, of future

hifi applications, and I find the

promise credible; an experimental car

stereo system with flush DML panels

in the upper dashboard sounded just

great to me in a recent demonstration,

dome tweeter. The woofer, with com-

posite paper cone (arguably still the

best material for large diaphragms),

phase plug, and polymer chassis, is

mounted above the tweeter. The en-

closure is vented to the rear. The silk

dome of the tweeter is slightly recessed

in a shallow hornlike cavity. The

crossover network is secondorder.

My quasianechoic (MLS) mea-

surements yielded very nice frequency

response curves over a large solid angle.

The small separation between the two

drivers and the fairly seamless crossover

made it quite uncritical whether the

calibrated microphone was aimed at

the woofer or the tweeter, or halfway

between the two—the results were al-

most identical. On the axis of the

speaker the tweeter response appeared

fully competitive with highend instal-

lations of conventional design. The

DML is definitely something to be

aware of as the art progresses.

As for the individual reviews that

follow, you know the old boxing adage

that a good big one will always beat a

good little one—but the true aficionado

judges each contender in the context of

the competition. We have a varied as-

sortment of good/big and good/little

here, but is there a weightdivision

champion in the bunch? I think there is

at least one, but you will have to decide

after having digested the facts.

to be slightly elevated in the top oc-

tave, especially since the two octaves

from 2 to 8 kHz are extremely flat:

±1.25 dB. The 8 to 16 kHz octave av-

erages 3 to 4 dB above that reference

level, with a welldamped peak at

13 kHz. Now here's the most inter-

esting part: at 45° off axis (horizon-

tally) the elevated top octave falls into

line, more or less, with the two octaves

below, so that the overall response is

actually flatter than on axis, with the

exception that the curve plummets

above 13 kHz. This behavior indicates

good power response into the room

and relative flexibility in the choice of

listening positions and leftright sepa-

ration. The phase response is wellbe-

haved at all measurement angles

The bass response does not go very

low, as the speaker is designed to work

in conjunction with a subwoofer. The

vented box is tuned to approximately

56 Hz; the maximum output from the

vent is at about 64 Hz. The summed

response of woofer and vent is essen-

tially flat down to an f3 (3 dB point)

of 60 Hz, exactly as given in the specs.

Below the f3 the response rolls off at

the rate of 18 dB per octave (QB3

alignment, most likely). Everything ap-

pears to be very simple and straight-

forward. The impedance of the system

varies from 6.2Ω. to 23Ω in magnitude

10

THE AUDIO CRITIC

pdf 10

Page 11

and between ±35° in phase, not a difficult load for the amplifier.

Tweeter distortion is negligible, as

it nearly always is, but the woofer is

unhappy with high-level inputs below

the f3, not surprisingly. For example, a

50 Hz tone at a 1-meter SPL of 90 dB

bristles with both even and odd har-

monics. The second harmonic (100

Hz) is at the -26 dB (5%) level, the

third and fourth at -31 dB (2.8%)

EgglestonWorks Loudspeaker Company,

435 South Front Street, Memphis, TN

38103. Voice: (901) 525-1100 or (877)

344-5378. Fax: (901) 525-1050. E-mail:

ewgroup@ix.netcom. com. Web:

www.eggworks.com. Isabel 2-way compact loudspeaker system, $2900.00 the

pair. Matching stand, $500.00 the pair.

Tested samples on loan from manufacturer.

As soon as I started unpacking the

Isabels I became aware that I wasn't in

Kansas anymore but in high-end

tweako country.

Inside the shipping carton, this

obelisk-shaped little speaker is spirally

wrapped like a mummy—yards and

yards and yards of clingy wrapping to

protect the high-gloss black finish. Unlike the usual protective bag or sock,

the mummy wrapping is destroyed in

the unpacking process. But that's not

all. I said "little speaker," but this 2way compact monitor weighs 55

pounds. Yes, with granite side panels, I

kid you not. And that's not all. The

boxy base the speaker needs to be

mounted on is the ultimate embodiment of the high-end audiophile creed

of redemption through suffering. The

prescribed mounting procedure requires eleven—count them!—steps.

The four bolts that are supposed to

fasten the speaker to the base must be

tightened with various washers from

inside the base cavity. To do that successfully one must be either a midget

each, and it doesn't stop there. At the

same SPL, however, any fundamental

above 125 Hz is quite clean, with a

THD in the neighborhood of-46 dB

(0.5%). I call that very acceptable in a

5½-inch woofer of nonexotic design.

The sound quality of the AV-1 exceeded my expectations. Subjectively, I

found the speaker to make a better

sonic impression when inserted into my

home theater system than any number

who can crawl all the way into the

hollow base or an orangutan with arms

twice the length of mine.

Get the picture? No you don't. You

are then supposed to fill the base with

sand or lead shot through a special fill

hole (no water or "any other liquid," we

are warned) and screw spikes into the

bottom. I could go on but I don't want

to create the impression that I developed a cultural antagonism to Bill

Eggleston's product before I even tested

it. No, I gave it every chance; it's just

that I come from another world and

my jaw tends to drop when I find myself in the high-end fantasists' Land of

Oz. I must hasten to add, for the

record, that I callously disregarded the

instructions and simply placed the

speaker without bolts on top of the unfilled and unspiked base, where it remained anchored by its own weight,

solid as a rock. I am sure the rhythmand-pace suffered hugely as a result, but

that was of no consequence to an ignorant and insensitive tin ear like me.

The basic engineering design of the

Isabel is, on the other hand, extremely

simple. (Let's face it, highly sophisticated electroacoustical engineering

seldom goes hand in hand with leadshot filling.) The granite-reinforced

MDF enclosure—hernia city, as I

said—is vented to the rear because the

front panel is barely large enough for

the 1-inch tweeter and 6-inch

midrange/bass driver. The tweeter is

Dynaudio's Esotar cloth-dome model;

of more expensive units that had resided

there before. Definition, balance, and

ease of dynamics appeared to improve.

On music, in my reference stereo

system, the AV-1 did not quite have the

airy transparency and exquisite detail of

the finest speakers but certainly held its

own against anything costing $450 per

side and then some. There is nothing really faulty or unnatural about its sound.

Definitely recommended.

the 6-incher is from Israel (Morel), featuring a big motor with double magnet

and 3-inch voice coil. Expensive drivers, that's for sure. The internal wiring

is supplied by Transparent Audio—

most probably high-end fantasy cable

of no special electrical advantage.

The dead giveaway of the high-end

tweako culture is the crossover. The

mid/bass driver is driven naked, directly connected to the amplifier. The

tweeter is driven through a single series

capacitor, in conjunction with a two-resistor L-pad. The theory is that the simplest possible network will yield the

best possible sound—the purest solution and all that jazz. Unfortunately, it

doesn't quite work that way. Conceptually, a perfectly controlled, smooth

midrange rolloff without a network

could be modeled as a lowpass filter

that sums to unity with a correctly calculated highpass filter for the tweeter.

That involves a lot of fancy math not in

evidence in the Isabel. The Morel driver

doesn't conveniently roll off at 6 dB per

octave as claimed by Eggleston—no

mass-controlled diaphragm does—and

thus cannot form a perfect first-order

crossover with the series capacitor on

the tweeter. (Not that a first-order

crossover is ideal in any event, but we

don't need an argument about religion

here.) Bottom line: the 6-inch driver

runs out of steam around 4 kHz and

the tweeter just sort of backs into the

dip there without a really good fit.

My quasi-anechoic (MLS) mea-

12

THE AUDIO CRITIC

pdf 11

Page 12

surements yielded basically good results in the top two octaves of the

audio spectrum and not so good further down. In other words, the Esotar

tweeter delivers but the Morel

mid/bass and the crossover show their

shortcomings. The response from 6 to

17 kHz is flat within ± 1 dB and holds

up very nicely even 45° off axis, both

horizontally and vertically. The resonant peak of the dome is around

16 kHz. The 6inch driver has a roller

coaster response varying at least ±3 dB

and in some cases, depending on how

the microphone is aimed, as much as

±4 dB. Not very impressive—and conducive to doubts about a 3inch voice

coil for a 6inch transducer. Bass response is naturally not very deep with

the vented box tuned to 100 Hz and

maximum output from the vent at

around 130 Hz. Eggleston claims —3

dB at 60 Hz; I don't know how they

figured that but I'll let it be. In any

Sonigistix Incorporated, 101 South Spring

Street, Suite 230, Little Rock, AR 72201.

Voice: (877) PC AUDIO (toll free). Web:

www.monsoonpower.com. MM1000 multi-

media speaker system, $229.00. Tested

samples on loan from manufacturer.

Some time ago I received a phone

call from David Clark, the designer of

this speaker system for computers. (His

company is DLC Design; Sonigistix is

one of his ancillary enterprises.) He told

me he would send me the $229 Monsoon MM1000 for testing and asked

me to judge its nearfield sound, when

properly deployed in a desktop computer setup, as if I were evaluating a

costnoobject homeaudio model from

my normal listening position.

The man has cojones, I said to myself. But wait! It turned out he was

basically right. I am not saying that

my Waveform Mach 17 reference

speakers have been equaled or bested.

I am saying that the sound of the

case, a subwoofer is indicated for full

range response.

Tweeter distortion is very low, as it

nearly always is; at a 1meter SPL of 90

dB, normalized to 7 kHz, it remains

between 0.05% and 0.18% over more

than two octaves. The mid/bass distortion at the same SPL, normalized to

500 Hz, is in the 0.16% to 0.56%

range down to about 110 Hz, rising

rapidly to 10% at 32 Hz. All in all,

these are very respectable figures. Impedance, above the tuned box range,

varies from 6.5Ω to 12Ω in magnitude

and from 24° to +18° in phase, a very

easy load for the amplifier.

Despite my essentially negative reaction to the basic gestalt of the Isabel, I

am not about to characterize its sound as

bad—far from it. If you are used to

mediocre speakers, the Isabel will sound

absolutely gorgeous to you. Its excellent

tweeter makes the allimportant upper

midrange and lower treble sound sweet,

Monsoon, as experienced with my ears

about 18 inches from

the satellites, is of the

highest fidelity and not

an obvious comedown

after listening to any

highend speaker in a

conventional setup.

More about that below.

The MM1000 system consists of

three pieces: two slim panels, each

only slightly larger than a businesssize

envelope, and a small cube, less than a

foot in each dimension. The panels are

planar magnetic transducers—mini

Magneplanars so to speak—and the

cube houses a 5¼-inch woofer plus all

the electronics and controls. The box

is tuned to 53 Hz (manufacturer's

spec). There's also a tiny hard-wired

remote volume/mute control. The

electronics include two 12.5-watt amplifiers for the panel speakers, a 25watt amplifier for the woofer, and a

smooth, musical, and nonfatiguing at all

levels. If, on the other hand, you are

used to the finest speakers, as I am and

my associates are, the Isabel won't quite

make the grade. There is something

lacking in transparency, definition of detail, and rendition of space when judged

against the best. For example, the

JosephAudio RM7si "Signature" (see

Issue No. 25) is superior in all those respects at a little more than half the price

(exactly half if you count the Isabel's

stands). It's a classic case of creative engineering versus high-end chic. The

money at Eggleston went into imageoriented attributes, at JosephAudio into

performance essentials.

I must admit, however, that when

the Isabels are sitting there on their

stands, gleaming in high-gloss black

from obelisk peak to floor, they do

have that "Hey, what's that cool setup

you have there?" quality—if that's

what you're looking for.

200 Hz third-order active crossover.

The controls on the woofer enclosure

adjust overall bass level, volume, and

on/off 6 dB bass boost at 55 Hz.

That's a lot of stuff for $229 at retail,

even if none of it qualifies as "audiophile" grade. Sonigistix's parts buyer

must be quite resourceful. (Incidentally, the Monsoon MM-1000 is included in some Micron Millennia

computer packages.)

My standard methods of loud-

speaker measurement are not relevant

to this type of system, which is intended to operate in a confined desktop

ISSUE NO. 26 • FALL 2000

13

pdf 12

Page 13

environment with hardly any distance

between the transducers and the listener. The 1-meter quasi-anechoic

(MLS) response of an individual MM-

1000 planar magnetic satellite shows a

steady decline of approximately 6 dB

per octave throughout its range, and

that's certainly not what the ear perceives at the intended listening distance

with a reflective desktop interposed.

David Clark is one of the grand masters

of car-sound engineering, and it appears that the same sort of perceptual

response massaging took place here as

is required for the special acoustics of

an automobile interior. The woofer, on

the other hand, is a straightforward

vented-box design with essentially flat

response down to an f3 (-3 dB point) of

52 Hz, according to my nearfield measurement of the summed driver and

vent. Maybe that's what the specs mean

by "tuned to 53 Hz" because the null in

the output of the driver—what I call

the "tuned to" frequency—is 47 Hz in

my sample. Small quibble—52, 53, 47,

whatever—it isn't 27 and it can't be. It's

just a very nice small woofer. Distortion

is quite low; at any frequency above f

3

Revel "Salon"

Revel Corporation, a Harman International

Company, 8500 Balboa Boulevard, Northridge, CA 91329. Voice: (818) 830-8777.

Fax: (818)892-4960.

E-mail: support@revelspeakers.com. Web:

www.revelspeakers.com. "Salon" floorstanding 4-way loudspeaker system,

$14,400.00 or $15,500.00 the pair,

depending on finish. Tested samples on

loan from manufacturer.

This is a tough one. Kevin Voecks,

Snell's former ace and now chief designer of Harman International's ultrahigh-end Revel division, had told me

before the Revel "Salon" made its debut

that it would be "the world's best

speaker." I always had, and still have,

the highest respect for Kevin's work but

I can't quite go that far in my ranking

and any SPL even momentarily tolerable at the normal listening position,

THD remains below 1.5%, in most

cases well below. The planar satellites

stay below 0.5% THD at any frequency within their range and any SPL

that the 12.5-watt amplifiers can sustain (at some point buzzing ensues, but

only on steady-state signals, not on

music). Tone bursts of any frequency

are reproduced without ringing. Thus,

the system can be declared to have

some pretty decent measurable performance characteristics, even if one disregards the price—but is that what makes

it sound good? I'm sure that's part of it,

but the careful tailoring of the satellite

panels' response to the specific listening

environment is probably the most important factor. I can't be certain.

I'm on much firmer ground when I

tell you what I hear when I insert a wellrecorded music CD into my computer's

CD/DVD tray and set the volume to

the subjectively most convincing level.

Are there any obvious colorations? No.

Are all the instruments and voices natural and clear? Yes. Are the three-dimensional characteristics of the

of the Salon. Indeed, I am still inclined

to regard the aging Snell Acoustics Type

A as Kevin's masterpiece. Not that the

Salon is anything less than a very fine

loudspeaker system, exemplifying some

of today's most sophisticated design approaches. There are a few things about

it, however, that I like a lot less than I

expected to.

To begin with, the Salon is unnec-

essarily awkward physically. Each

speaker system in its shipping carton

weighs 240 pounds. I am pretty ingenious when it comes to moving huge

packages around without lifting them

(pushing on a dolly, sliding on a

carpet, tumbling the monsters end

over end, etc.), but this one gave me a

terrible time. The speaker incorporates

a separate main enclosure, a separate

recording space and the deployment of

the performers audible? Definitely. Are

the dynamics restricted? Not at all. If

the recorded sound is especially beautiful—shimmering strings, aerated

woodwinds, golden brasses—does that

special thrilling quality come through?

It does. Quite an amazing product.

Even so, don't misunderstand me.

The Monsoon MM-1000 is not the

$229 solution to the problem of finding

a reasonably priced reference-quality

speaker system for your listening room.

You will not like it if you insert it into

your regular stereo system and listen to

it from your favorite armchair. It is designed for a highly specialized application, just like a pair of headphones. In

that application, I believe it will satisfy

the most demanding users. What I admire about it especially is that it is such

an elegant piece of engineering, in the

true sense of the word. Engineering, to

me, means the straightest line to the

simplest correct solution. You think a

$156,000 Wilson Audio speaker system

is engineering? No, it's an undisciplined

exercise in excess, a Caligula's feast. The

Monsoon MM-1000 is engineering.

tweeter/midrange enclosure, and two

huge detachable side panels, so there is

really no reason other than economy

(or support of hernia surgeons) to ship

it all screwed together; it could be

neatly broken down into manageable

modules. It's a no-brainer. That the

dealer or the end user (you or I)

couldn't assemble the modules as

solidly as the factory is a tweako highend bugaboo—and not the only one I

discerned in the Salon. Another is wire

fastener/connector phobia (i.e., solder

fetishism), which I discovered when I

had to replace both tweeters, front and

rear, in my left channel. A momentarily interrupted ground connection

somewhere in my A/B lash-up had

blown both units, raising the question

of excessive fragility (but that's not my

14

THE AUDIO CRITIC

pdf 13

Page 14

ISSUE NO. 26 • FALL 2000 15

point here) and necessitating the installation of new tweeters hastily obtained from Revel. I was genuinely

disturbed to see that Revel tack-solders

the fat wires from the crossover network to the tiny terminals of the

tweeters without any mechanical con-

nection. I have seen some very high-

quality snap-on connectors (e.g., in

JBL speakers and others) that make life

a lot more pleasant should servicing be

required—and, no, they don't fail; they

don't introduce more than a hundredth

of an ohm; they just cost more than a

blob of solder.

There, I'm already grumpy and I

haven't even started to discuss the

sound or the measurements. Yes, I also

have some good things to say, but let's

begin at the beginning.

The Salon is designed with seven

drivers per side, five of them created

from scratch in Harman International's

facilities. The two exceptions are the

1.1-inch aluminum-dome front

tweeter and the 0.75-inch aluminumdome rear tweeter, which are imports

(the front unit a very expensive one

from Scan-Speak). The latest in-house

tweeters were apparently not yet available when the Salon was in the development stage. Not so the midrange

driver, a unique in-house design with a

4-inch (!) concave titanium dome—

very impressive. The midrange and the

front tweeter are housed in a separate

enclosure with thickly rounded edges

and corners to control diffraction. The

woofer complement consists of three

vertically deployed 8-inch drivers in

the main enclosure, which is loaded

with a huge flared port firing rearward.

On top of the woofers there is a 6½inch midbass driver, and the little rear

tweeter is mounted near the top of the

main enclosure's back. The three

woofers and the midbass all have concave diaphragms made of an apparently very high-tech polymer material.

The crossover network uses 24-dB-peroctave slopes (naturally), air-core in-

pdf 14

Page 15

ductors, and film capacitors; the

crossover frequencies are 125 Hz,

450 Hz, and 2.2 kHz. Two pairs of

binding posts in the rear provide the

usual choice of single wiring, biwiring,

and biamping; a level control for the

front tweeter provides —1, -0.5, 0,

+0.5, +1 settings; a level control for the

rear tweeter can be set to Off, 0, or -3;

a continuously variable LF compensa-

tion control has a range of—2 dB to +2

dB centering on 50 Hz.

The most controversial thing about

the Revel Salon right out of the shipping carton is its appearance. Are the

gigantic kidney-shaped side panels

functional or an over-the-top "contemporary design" conceit? They do add

mass and stiffness to the cabinet, but

the speaker can function without them

(grilleless, to be sure, as they anchor the

strangely bowed-out nondiffractive

grille-cloth assembly). Side panels of

several other colors (my samples came

in rosewood) can be substituted, as can

grille cloths (mine were dark gray), and

the enclosures themselves can be ordered in a number of finishes (mine

were high-gloss black). Thus the basic

gee-whiz contempo look comes in gradations from relatively conservative,

such as my samples, to a bold color

combination approximating the Polish

flag. First-time reactions to Revel's visual

statement range from bravo to yuck.

Mine was quite favorable, on the whole.

I think the industrial designer's

marching orders were to maintain a

family look in all Revel models,

regardless of size. That's not easy.

I decided to listen to the Revel

Salon before measuring it because I did

not want to be influenced by what I

presumed would be outstanding measurements. (Not that such a presumption is entirely without influence.) I

fired up the speakers with a good orchestral CD through 200 watts per

channel and was almost immediately

struck by the total absence of dynamic

compression. That may be the Salon's

strongest feature. Those special drivers

are doing the job. The bass is rock-solid

and goes low enough, and then some,

to obviate subwoofers. What about

transparency and lack of coloration?

That was a more difficult assessment,

requiring further investigation.

Since Floyd Toole sets the general

guidelines for all Harman Interna-

tional speaker designs (leaving the actual execution to the individual

designers) I followed his well-known

and by now axiomatic protocol for

A/B comparisons. To wit: the speaker

under test and the reference speaker

must be compared one on one, mono

versus mono, side by side, free-

standing, at matched levels. My reference speaker, as already stated above, is

the Waveform Mach 17. I used identical monoblock power amps with

volume controls to drive the speakers,

carefully matching the pink-noise SPLs

within a fraction of a dB with a soundlevel meter at my listening location. I

turned off the rear tweeter of the Salon

to make the listening setup as symmetrical as possible. Initially I had all level

controls of the Salon at 0.

Please note that this was not a blind

test. It would have required a repositioning carousel and a huge acoustically

transparent screen to make it blind.

Our laboratory is not quite on that

level of sophistication. Besides, very few

speakers sound so much alike that a

blind test is absolutely needed. (Take it

from a hard-core ABX advocate when

it comes to electronic signal paths.)

Above all, be aware that even such an

objectively configured listening test is

subjective in its conclusions; only measurements are provably objective.

So, what did I hear? With the

Salon's tweeter level set to 0, it had a disembodied-top type of coloration to my

ears, not even close in neutrality to the

Mach 17, which had been optimally

balanced through its electronic

crossover. The most listenable output of

the Salon appeared to be obtainable

with the tweeter level set to -1, but even

then the balance from the top down to

the lower registers wasn't quite as seamless and natural as that of the Waveform. The midrange of the latter also

appeared to be better rounded and

somehow more lifelike than the Revel's,

particularly on singers' voices, both

male and female. Mind you, the difference wasn't huge, but every time I

quickly switched from the Revel to the

Waveform the sound appeared to open

up, smoothen out, and acquire a more

credible perspective—subtly, not dramatically. A briefly participating female

listener felt that the Revel's sound was

slightly irritating (I couldn't quite agree)

and the Waveform's natural and nonfa-

tiguing (I agreed). Of course, all of the

above could be contradicted by a highly

qualified listener whose sonic tastes are

different from mine because the sound

of the Revel Salon is good enough to be

subject to pro/con argument on the

highest level. My own perception is that

the Salon is very good and the Mach 17

is the best—and the best is the enemy

of the good, as Voltaire said.

Interestingly enough, the Snell

Type A sounds much more like the

Waveform Mach 17 in a similar A/B

comparison (see Issue No. 24), hence

ISSUE NO. 26 • FALL 2000

17

pdf 15

Page 16

my aforementioned partiality to the

Snell. I am fully aware that the

Harman International test facility built

under the direction of Floyd Toole is

more advanced than his older NRC facility in Canada and that the Revel

Salon is the result of an even more sophisticated design protocol than the

NRCderived Snell Type A, but a

better tool doesn't necessarily guarantee

a better result. I must also add, in all

fairness, that the Snell was not available for an A/B/C comparison.

When it came to the measurements I must confess I was seriously

intimidated by the engineering pedi-

gree of the speaker. Unlike Kevin

Voecks, I can't run accurate response

curves at 72 different points in a 4Π

space inside a gigantic anechoic

chamber—and that's just a small part

of their design and test procedures. It

is beyond the scope of this review to

discuss in detail everything that Revel

does; go to www.revelspeakers.com

for the ultimate in audiogeek intimidation. They do all sorts of averaging,

smoothing, powerresponse figuring,

psychoacoustic massaging, etc., as

against my pitifully few 1meter and

2meter quasianechoic (MLS) curves

and ridiculously simple nearfield measurements. All I can say in defense of

my clearly less sophisticated methods

is that they have served me well in the

past to identify strengths and weaknesses and to support my subjective

perceptions with valid objective data.

So, I've hemmed and hawed long

enough; now I'll have to say it: I was

unable to obtain as good measurements

on the Revel Salon as on the Waveform

Mach 17 (or the Snell Type A for that

matter). No matter which driver I

aimed the microphone at, from 1 meter

or 2 meters, the absolute best onaxis

response I could get was ±3.5 dB (i.e.,

all swings contained within a 7dB

strip). That was taken from 1 meter, on

the axis of the tweeter, with the tweeter

level set to 1. Furthermore, every one

of the many response curves I experimented with showed combfilter squig

gles all over the place, something I

never see in my routine measurements.

What's more, all the curves had a maximum dip in the 3.5 to 4 kHz band,

where there isn't even a crossover. I

could dismiss these anomalies as mea-

surement artifacts (as I am sure Revel

would) if—but only if—the speaker

had sounded more neutral to my ears

than the Waveform or the Snell. What

caused them is subject to speculation,

perhaps the spacing of the drivers,

perhaps the protruding upperfront

corners of the side panels, perhaps

something else altogether or a combination of such things. One response

curve that was quite impressive, on the

other hand, was the one taken 45° off

the tweeter axis at a 1meter distance,

with the tweeter level set to 0 (not —1,

alas). The tweeter response remained

within a 2.8 dB strip up to 9 kHz and

dropped only 5 dB at 14 kHz. That indicates very good power response as

well as the absence of the headon

anomalies. Mysterious.

Bass response shows the classic B4

alignment, flat down the boxtuning

frequency of 24 Hz (—3 dB point),

fourthorder slope below that. No

problem, no mysteries. The impedance

curve of the system is similarly

unproblematic, between 3.2 and 9.3

ohms in magnitude from 20 Hz to

20 kHz (6 ohms nominal) and ±33° in

phase over the same range. It's a load

you could drive with a cheap Pioneer

receiver if you are unafraid of the high

end audio Furies. Distortion is outstandingly low at all frequencies; I

think even David Hall of Velodyne

would approve (or at least not disapprove). For example, the nearfield

THD of the woofer at 50 Hz at a

1meter SPL of 97 dB is 0.5%, rising

with a steady slope to 2.5% at 30 Hz.

Further up, the midbass/midrange

THD hovers around 0.5% up to 1

kHz at a 1meter SPL of 90 dB. Above

that range, where the tweeter begins to

take over, the THD is negligible. Once

again, no problemo.

So—what kind of recommendation

can I make regarding the Revel Salon? If

somebody gives it to you for your

birthday or Christmas, keep it. There

aren't too many better speakers out

there. If you are using your own money,

you have some options I consider superior, as I have already explained. The

Revel people will of course disagree on

the grounds that their measurement

procedures are more comprehensive and

accurate than mine and their listening

protocol more objective. That may very

well be true but I have one advantage

over them: I don't care whose speaker

comes out on top, but they do.

Postscript: After I had written the

above, I heard a strange explanation of

the 3.5 to 4 kHz dip in the Revel

Salon's response. The explanation (excuse?) does not appear anywhere in the

Revel literature or on their Web site,

where all is flatness, sweetness, and

light. No, it's what the Revel designers

are saying in private discussions, at least

according to my admittedly not quite

firsthand informants. They (allegedly)

say the dip is necessary in mono to

compensate for subtle headgeometry

effects in stereo. In other words, the response needs to be a little bit "bad" in

mono so it will be totally "good" in

stereo. I have a couple of problems with

that, if it's indeed what they are saying.

What happened to Floyd Toole's famous mono listeningtest protocol?

Why didn't the slight imperfections I

heard in mono disappear totally in

stereo? Are frequencyresponse cancellations/reinforcements around my thick

head the whole story when I hear small

colorations? How come this whole subject hasn't come up in connection with

other NRC/Toolederived loudspeaker

designs? Hey, this may be the most sophisticated insight in the world of audio

today, but why not come out and tell us

all? We're all ears.

18 THE AUDIO CRITIC

pdf 16

Page 17

By Peter Aczel, Editor

David A. Rich, Ph.D., Technical Editor

Glenn O. Strauss, Contributing Editor

Power Amplifiers and

Outboard D/A Converters

The good prevails; the bad and the ugly are

falling behind. That's basically the current

state of audio electronics, both analog and

digital—but you still can't believe every claim.

R

egular readers of this publication are familiar with our po-

sition on the audio quality of

electronic signal paths—what is audible

and what is not in valid, controlled listening tests. Newcomers should read a

few back issues (check out No. 24 and

25 for openers). We can't keep going

over the same ground in every issue.

Here I just want to emphasize

once again that in engineering, as in

other fields, good thinking costs no

more than bad thinking. Good measurements are proof of good thinking;

that's why we emphasize them,

whether "you can hear the difference"

or not. Maybe you can't hear 0.05%

THD, but 0.005% is just as easy to

achieve with good thinking and a lot

more reassuring. Besides, if you cas-

cade four or five of those devices with

not-so-great measurements . . . who

knows? —Ed.

Bryston Ltd., P.O. Box 2170, 677 Neal

Drive, Peterborough, Ont., Canada K9J

7Y4. Voice: (705) 742-5325 or (800)

632-8217. Fax: (705) 742-0882. Web:

www.bryston.ca. 9B ST 5-channel power

amplifier, $3695.00. Tested sample on

loan from manufacturer.

In amplifier design, Chris Russell

and Stuart Taylor are a combination

like Joe Montana and Jerry Rice in the

NFL of the 1980s—as good as it gets.

The basic Bryston power-amp

topology (the one that made David

Rich call Chris "a ridiculously good engineer" in a long-ago issue of this

journal) has changed only slightly over

the years. The main improvements in

the present line have to do with physical layout and how the gain is shared

between the stages, the net result being

a lower noise floor. The ST suffix fol-

lowing the model number credits

Stuart Taylor for the improvements. I

have already reviewed the 3-channel

and 4-channel ST amps in the line (see

Issue No. 24); the 9B ST is their 5channel model and the flagship of the

line (at least until a higher-powered

version now in the pipeline is released).

This is truly a gorgeous piece of

equipment. No wonder Bryston likes to

exhibit it with the cover off at the various shows. The layout is of the utmost

architectural beauty because of its uncluttered simplicity. Five self-contained,

independent mono modules are arrayed

side by side, each fully operational by itself. Only the line cord and the on/off

switch are shared. Each module offers

unbalanced, balanced, or high-gain