Page 1

Issue No. 22

Display until arrival of

Issue No. 23.

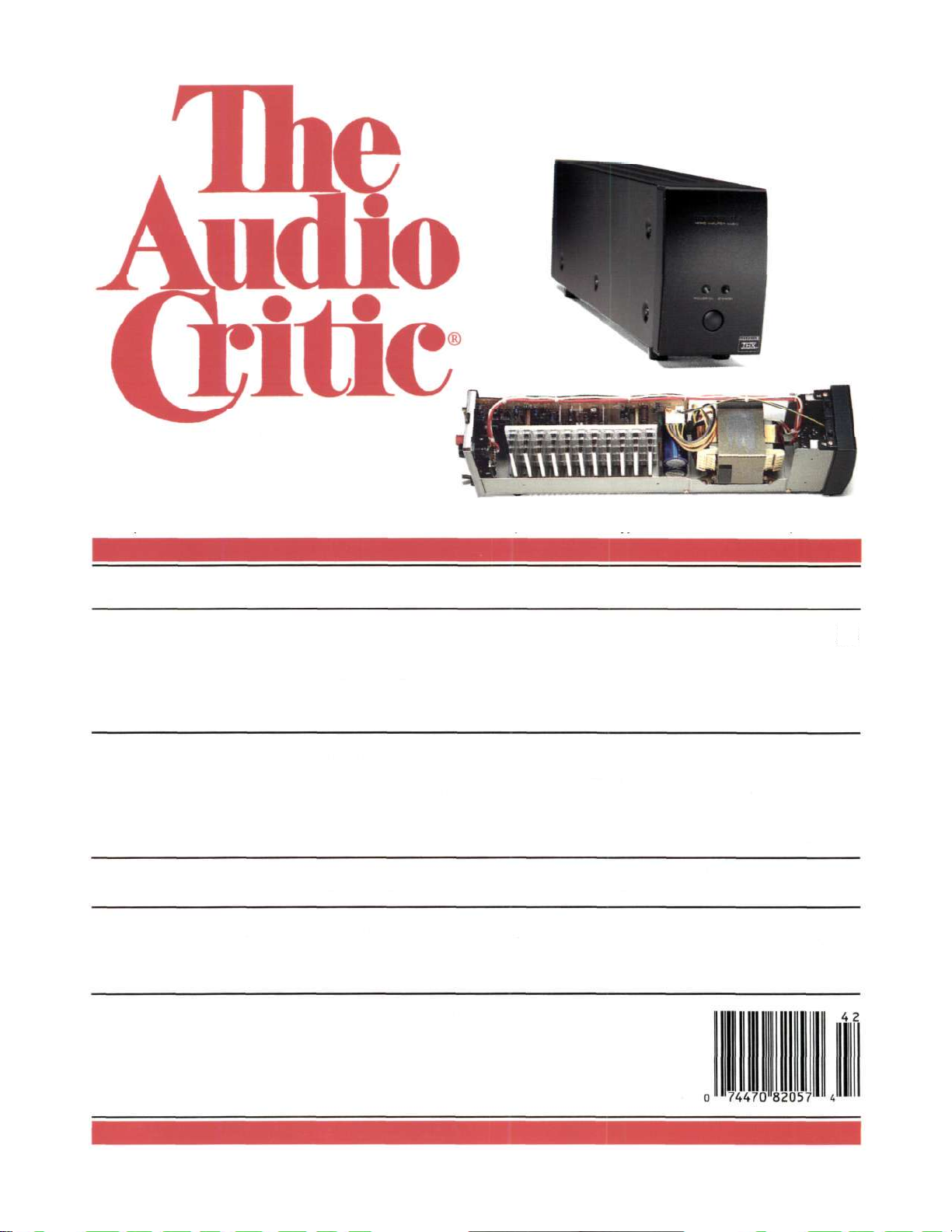

Is this the format of the future in power amplifiers?

(See the analog electronics reviews.)

Retail price: U.S. $7.50, Can. $8.50

In this issue:

A number of exceptionally competent (and in some

cases controversial) loudspeaker designs are

evaluated, with special emphasis on subwoofers.

In an editorial that will raise some eyebrows, and

even some blood pressures, your Editor analyzes

the hypocrisy of the high priests of the High End.

We continue our survey of amplifiers and preamps.

The question of when, if ever, absolute polarity is

audible is clarified in a letter from a top authority.

Plus other test reports, all our regular

columns, and the return of our popular

CD capsule reviews (oodles of them).

pdf 1

Page 2

Contents

Paradoxes and Ironies of the Audio World:

The Doctor Zaius Syndrome

By Peter Aczel, Editor and Publisher

Loudspeakers Are Getting Better and Better

By Peter Aczel, Editor and Publisher

12 ACI "Spirit"

13 Bag End ELF Systems S10E-C and S18E-C (continued from Issue No. 21)

14 What the Bag End ELF System Does and Doesn't (sidebar by Dr. David Rich)

15 Velodyne DF-661 (continued from Issue No. 21)

21 Velodyne Servo F-1500R

23 Win SM-8

43 Snell Acoustics Type A (last-minute mini preview)

Good Things Are Still Happening in

Analog Electronics

By Peter Aczel, Editor and Publisher

& David A. Rich, Ph.D., Contributing Technical Editor

25 Line-Level Preamplifier: Aragon 18k (Reviewed by Peter Aczel)

27 Line-Level Preamplifier: Bryston BP20 (Reviewed by Peter Aczel)

27 Mono Power Amplifier: Marantz MA500 (Reviewed by Peter Aczel)

28 Stereo Power Amplifier: PSE Studio IV (Reviewed by David Rich)

29 Line-Level Preamplifier: Rotel RHA-10 (Reviewed by Peter Aczel)

30 Stereo Power Amplifier: Rotel RHB-10 (Reviewed by Peter Aczel)

30 Passive Control Unit: Rotel RHC-10 (Reviewed by Peter Aczel)

31 Stereo Power Amplifier: Sunfire (Preview by Peter Aczel and David Rich)

Catching Up on the Digital Scene

By Peter Aczel, Editor and Publisher

& David A. Rich, Ph.D., Contributing Technical Editor

33 Compact Disc Player: Denon DCD-2700 (Reviewed by David Rich)

35 Outboard D/A Converter with Transport: Deltec Precision Audio PDM 2 and T1

(Reviewed by Peter Aczel)

36 Compact Disc Player: Enlightened Audio Designs CD-1000

(Reviewed by Peter Aczel)

41 Compact Disc Player: Marantz CD-63 and CD-63SE (Reviewed by David Rich)

Large-Screen TV for Home Theater:

Is a 40" Direct-View Tube Big Enough?

By Peter Aczel, Editor and Publisher

45 40" Direct-View Color TV: Mitsubishi CS-40601

Obstructionism By Tom Nousaine

Hip Boots Wading through the Mire of Misinformation in the Audio Press

Four commentaries by the Editor

Recorded Music Editor's Grab Bag of CDs, New or Fairly Recent

ISSUE NO. 22 • WINTER 1994-95 1

10

12

25

33

45

47

50

52

pdf 2

Page 3

From the Editor/Publisher:

This issue is dated Winter 1994-95. The

last issue, No. 21, was dated Spring 1994.

That was late spring; this issue goes to

press in early winter, so the gap is smaller

than the apparent nine months but bad

enough. What are we doing about it? Lots

of things—but we have learned, painfully,

not to make promises before the implementation is a reality. Three things are certain:

(1) something has to give; (2) we are here

to stay, regardless; (3) we are not changing our editorial stance. That still leaves a

number of viable scenarios to choose from.

Issue No. 22

Winter 1994-95

Editor and Publisher

Contributing Technical Editor

Contributing Editor at Large

Technical Consultant

Columnist

Cartoonist and Illustrator

Business Manager

Peter Aczel

David Rich

David Ranada

Steven Norsworthy

Tom Nousaine

Tom Aczel

Bodil Aczel

The Audio Critic® (ISSN 0146-4701) is published quarterly for $24

per year by Critic Publications, Inc., 1380 Masi Road, Quakertown, PA

18951-5221. Second-class postage paid at Quakertown, PA. Postmaster:

Send address changes to The Audio Critic, P.O. Box 978, Quakertown,

PA 18951-0978.

The Audio Critic is an advisory service and technical review for

consumers of sophisticated audio equipment. Any conclusion, rating,

recommendation, criticism, or caveat published by The Audio Critic

represents the personal findings and judgments of the Editor and the

Staff, based only on the equipment available to their scrutiny and on

their knowledge of the subject, and is therefore not offered to the reader

as an infallible truth nor as an irreversible opinion applying to all extant

and forthcoming samples of a particular product. Address all editorial

correspondence to The Editor, The Audio Critic, P.O. Box 978,

Quakertown, PA 18951-0978.

Contents of this issue copyright © 1994 by Critic Publications, Inc. All rights

reserved under international and Pan-American copyright conventions. Reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited without the prior written permission of

the Publisher. Paraphrasing of product reviews for advertising or commercial

purposes is also prohibited without prior written permission. The Audio Critic

will use all available means to prevent or prosecute any such unauthorized use

of its material or its name.

Subscription Information and Rates

First of all, you don't absolutely need one of our printed subscription blanks. If you wish, simply write your name and address as legibly

as possible on any piece of paper. Preferably print or type. Enclose with

payment. That's all. Or, if you prefer, use VISA or MasterCard, either

by mail or by telephone.

Secondly, we have only two subscription rates. If you live in the

U.S., Canada, or Mexico, you pay $24 for four consecutive issues

(scheduled to be mailed at approximately quarterly intervals). If you

live in any other country, you pay $38 for a four-issue subscription by

airmail. All payments from abroad, including Canada, must be in U.S.

funds, collectable in the U.S. without a service charge.

You may start your subscription with any issue, although we feel

that new subscribers should have a few back issues to gain a better understanding of what The Audio Critic is all about. We still have Issues

No. 11, 13, 14, and 16 through 21 in stock. Issues earlier than No. 11

are now out of print, as are No. 12 and No. 15. Please specify which

issues you want (at $24 per four).

One more thing. We don't sell single issues by mail. You'll find

those at somewhat higher cost at selected newsdealers, bookstores, and

audio stores.

Address all subscriptions to The Audio Critic, P.O. Box 978,

Quakertown, PA 18951-0978. VISA/MasterCard: (215) 538-9555.

2 THE AUDIO CRITIC

pdf 3

Page 4

Box 978

Letters to the Editor

An archetypal letter we seem to get again and again lists in loving detail all the components in the

writer's system, down to interconnects and tiptoes. In nearly every case it's quite unclear what the

letter writer wants. Our official blessing? Recommended changes? Recognition as a blood brother?

Please, all you audio addicts, if you insist on talking about your equipment and want to get our

attention, make sure you explain how it all ties in with our editorial concerns. Letters printed here

may or may not be excerpted at the discretion of the Editor. Ellipsis (...) indicates omission. Address

all editorial correspondence to the Editor, The Audio Critic, P.O. Box 978, Quakertown, PA 18951.

The Audio Critic:

...I have read Issue No. 20 and

found it quite charming. Your elegant

chopping to pieces of the audio tweakies

was very nice indeed. I even enjoyed the

writings of the others, many of whom I

know quite well....

* * *

[Six weeks later:]

I have now read the several issues of

The Audio Critic which I recently received. They are very interesting, and I

want to congratulate you on getting some

very good people to write for you. I am a

bit surprised that you and some letter

writers refer to my modest work so frequently but appreciate the interest I have

generated. There are many issues that

need deep thought, and I am delighted to

have these discussions take place, since

the light envoked (with some heat) eventually seems to pry out the truth.

It is very annoying to have persons

at the extreme fringes of an issue use

one's writings to prove their point with

elements of these writings taken out of

context. Unfortunately, it happens only

too often. Shades of gray are too often

made black or white by fanatics.

I was pleased to see complete para-

graphs from my paper quoted in context

printed in Issue No. 21. Additionally,

your interpretation, printed on page 8, of

what my article said is quite accurate but

a bit more truncated than I would have

preferred. If you have the patience, I supply for you herewith my own summary of

my work on acoustic polarity.

For perspective, my paper on polari-

ty was presented at an AES convention in

1991 and was published in the Journal of

the Audio Engineering Society, Vol. 42,

No. 4, 1994 April. Needless to say, this is

a professional Journal for which all articles are extensively reviewed for quality

and accuracy. A version of this paper was

also printed in Audio magazine with minor modifications to satisfy a different

(and much larger) audience. Nevertheless, the essential contents of the several

versions of the paper are identical.

I strongly suggest that anyone interested in this matter read the original

paper and not someone else's interpretation of what it might say. Some of the listening tests are fairy easy to duplicate,

and the paper is written in very simple,

not highly technical, terms.

These comments cover both the

work I did in 1991 and my more recent

experiences (1993-1994), which are indicated by brackets [...].

There are four points made:

1. It is clearly possible to show the

audibility of acoustic polarity inversion

with steady-state tones (electronically

generated) or quasi-steady-state tones

(produced on physical instruments but

with steady monotone playing techniques). These are boring, nonmusical

tones. The audibility of acoustic polarity

inversion for these very special cases has

been documented by several authors. [I

have repeated this listening experience

many times with both headphones and

various loudspeakers, and the experience

is so definitive that there is no question

about its existence.]

2. When real musical performance

material is used in such tests, it is very,

very difficult (nearly impossible) to hear

the effects of polarity inversion. Our

large group tests showed only very slight

positive results with loudspeakers in a

highly idealized and simplified listening

environment. [These listening tests have

been repeated with headphones and a

great variety of loudspeakers, and it has

been confirmed that it is very, very

difficult to hear polarity inversion. Nei-

ISSUE NO. 22 • WINTER 1994-95 3

pdf 4

Page 5

ther I nor anyone I know, and trust, has

heard acoustic polarity inversion with stereo program material in a normal listening environment.]

3. Because it was so easy to hear

polarity inversion with simple steadystate tones and so difficult to hear with

real music, a large part of the paper is devoted to trying to determine the reasons

why this is the case. A major part of the

paper suggests, but does not firmly

define, these reasons. More work is required to define this very subtile psychoacoustic effect. [While I have continued

some work in this area, I have not found

a consistent, definitive cause/effect relationship. However, it is clear to me that

the audibility of acoustic polarity inversion is dependent on both the acuity of

the listener and the nature of the program

material, and not highly dependent on the

transducers involved.]

4. The issue of the audibility of

acoustic polarity inversion is not a matter

of black and white but of a series of

shades of gray, seemingly dependent

upon the simplicity or complexity of the

program material being auditioned, to

some small extent upon similar factors of

complexity of the listening environment,

and to some extent upon the sensitivity of

the listener. [While I would like to see

standardization of polarity in recording

and reproduction, it seems to be a minor

issue compared to others that affect

sound reproduction much more strongly.]

Several final issues need to be laid

to rest. One is the question of the use of

digital recordings and digital program

material to do listening experiments. The

essential results described above have

been duplicated with real instruments,

microphones, and headphones in real

time without the use of any recording devices. Some fanatics suggest that only

they can hear things because of their

equipment. This is total nonsense.

Some have suggested that the quality of the loudspeaker and/or measurement techniques used for the original

paper were somehow defective. (This has

been implied by some snide remarks by

C. Johnsen in The Audio Critic letters

column as well as in Audio magazine.)

Our experiments were set up with extreme care, using a large array of the

very best professional-level instrumentation equipment in my Electroacoustics

Laboratory. We are totally comfortable

that we know how to use this equipment,

have designed a suitable loudspeaker, and

4

have analyzed the results in an entirely

professional manner.

Finally, all of our findings have been

confirmed with headphones of various

sorts and a number of quite diversely de-

signed loudspeakers. The design of the

headphones or loudspeakers, within reason, is in my experience irrelevant to revealing the phenomenon.

I have over the years discussed these

issues with many AES members, including Richard Heyser and Stan Lipshitz. I

believe that we all would prefer that the

industry took care with polarity conventions. But, they have not for the most

part. Polarity is simply not a high-priority

issue for most professionals and certainly

not highly important for the enjoyment of

reproduced sound.

Nevertheless, I am actively carrying

out additional experiments and I hope to

pursue the matter with the goal of

finding sources/causes of audibility of

acoustic polarity inversion and to specify

it more clearly in a scientific, responsible

manner.

That's it for the time being. I suppose

that heated debate will continue, just as it

does with the cable/interconnect issue.

Very sincerely,

R. A. Greiner

Professor

Fellow of the AES

Thank you for the kind words about

The Audio Critic. We not only get "some

very good people" to write articles for us

but also, as your example proves, some

very good people to write letters to the

Editor. Indeed, your letter dots the i's

and crosses the t's on the subject of polarity for all rational audiophiles. Let the

tweaks read it and weep.

—Ed.

The Audio Critic:

I love you curmudgeons. You're

even occasionally correct—but then, so

are John [Atkinson] and Harry [Pearson].

I have no doubts as to your superior

theoretical and technical qualifications; I

also have no doubt that much subjective

reviewing necessarily utilizes poor methodology; however, why do you have

problems accepting the idea that some au-

dible differences are either difficult to

measure using conventional parameters,

or are the result of phenomena not yet

fully understood?

Howard Cowan

Woodland Hills, CA

/ have no problem whatsoever with

the ideas you state as long as those "audible differences" are indeed audible.

What I have a problem with is the statement that "I can hear the difference"

when you are unable to prove to me un-

der controlled conditions that you can ac-

tually hear it. If there really is a provably

audible difference, the cause may or may

not be easy to determine—that's a totally

separate issue.

As for John and Harry, see "The

Doctor Zaius Syndrome " (page 10).

—Ed.

The Audio Critic:

I have some ideas about how I think

a modern music-reproducing system

ought to be be configured to minimize

hardware interactions with the music information. I think from what I've read in

this magazine, and from some components already placed on the market (Meridian comes to mind), that some very talented people are thinking along these

same lines, and I'm wondering why we

(meaning the industry and the hobbyists)

are not headed a bit more quickly in this

direction.

Before I explain, let me admit (as

you're wont to question this) that I have

no credentials other than a 30-some-year

interest in the hobby. I'm also a fairly recent convert from the music-to-justifyhardware group.

My concept of a system would have

it divided into two basic modules. One

I'll call the control module, the other the

speaker-system module—or actually modules, as there would be several of these.

The control module would look very

much like a home computer system or

possibly a TV set, and might actually be

integrated with one of these—or both.

The purely electronic functions, such as

preamp, tuner, processor, etc., would be

installed as industry-standard plug-in

boards, with all of their switching and

control functions accessed as icons on the

screen—very similar to Macintosh, or

IBM with Windows, menus. Access to

the sound system might actually be a

menu option on your computer terminal.

The actual hands-on control would be a

mouse or infrared remote.

The control module would provide

ports with a standard multipin socket, for

inputs from purely mechanical program

sources such as an LP turntable [buggy

whip on the space shuttle?—Ed], CD

transport, cassette transport, etc. The

THE AUDIO CRITIC

pdf 5

Page 6

module would operate entirely in the digital domain, which would eliminate the

need for expensive hardware to maintain

a clean signal, and the output, or outputs,

to the speaker systems would be via

fiber-optic cables. System upgrades

would be accomplished by replacing or

adding boards.

The speaker systems would each

contain a speaker, or speakers, a bandwidth-limited amp with equalization (if

necessary), an electronic crossover, and a

DAC circuit for the fiber-optic inputs.

These systems would be tailored for their

particular function, such as subwoofer

(similar to the Velodynes), main left and

right, and surround-type speakers. I visualize the surround speakers as designed

much like track lighting on the ceiling,

spherical enclosures that would be aimable and could contain their electronics in

small boxes which could flush-mount in

the wall or ceiling and be attached by

short cables to the spheres. A full system

would consist of two subwoofers limited

to 80 Hz, two mains for left and right (80

Hz and up), and four of the ceilingmounted speakers, center front and back,

and back left and right.

Now tell me, where am I wrong in

this concept? And, if it's basically accurate, why aren't we already there? Disregarding the tubes-and-LP crowd, I think

we're hung up in oldthink. I, for one, find

the stack of black chassis and their tangle

of wires an eyesore and probably unnecessary.

Hartley Anderson

Waco, TX

To quote that song from the bigband era, "I'll Buy That Dream." As you

point out, bits and pieces of the dream exist already: powered subwoofers are the

rule rather than the exception; powered

full-range speakers are still the exception

but no longer a great rarity; Marantz

showed a computer front end as early as

1991; I could go on. It hasn't all come to-

gether, though; the demand isn't there;

"separates" are still the audiophile

norm.

Your basic concept is very much in

line with my own thinking, but I'll go

even further: A/D conversion should take

place right out of the microphone preamp

and the signal kept in the digital domain

throughout the recording, editing, mastering, duplicating, broadcasting, domestic playback, etc., processes, right up to

the D/A conversion just before the ampli-

ISSUE NO. 22 • WINTER 1994-95

fication stage of each separately powered

speaker channel—and that includes digi-

tal filters for all crossovers. (Maybe you,

too, had that in mind but didn 't quite say

it.) The speaker deployment should probably follow the Lexicon model in its fullest form: front left, center, and rear, subwoofer(s), side left and right, rear left

and right. But these are details. You've

got the main idea right—and you will see

it happen. The question is, when? Some

observers feel that the audio consumer

will continue to resist the idea of the separation of amplifiers and speakers.

—Ed.

The Audio Critic:

...My question specifically has to do

with whether a pair of subwoofers is better than one subwoofer. This question is

generated by a recent article by John F.

Sehring, which appeared in Audio magazine (February 1994). In that article, Mr.

Sehring gives a number of reasons why

stereo subwoofing is superior. I wonder

whether The Audio Critic has an opinion

in this regard. I also realize that the answer might depend partly upon a number

of variables (placement, room size, room

acoustics, etc.), and therefore no universal answer or rules of thumb may obtain.

However, any opinion at all would be

helpful.

I also have another question regarding the use of built-in amplifiers in subwoofers. Some recent literature which I

received from VMPS suggested that

built-in amplifiers are a bad idea because

subwoofer vibrations will eventually simply rattle them apart, as it were. Does this

turn out to be the case? Do the electronics

in powered subwoofers self-destruct after

a relatively short life span?

Please keep up the good work; your

magazine is a delight.

Sincerely,

David R. Reich

Auburn, NY

/ have always been of the opinion

that a pair of stereo subwoofers is prefer-

able to a single mono (L + R matrixed)

subwoofer—see Issue No. 16, page 16—

but Tom Nousaine, who has studied the

subject in considerable depth, vigorously

disagrees. His findings are documented

in a forthcoming article in the January

1995 issue of Stereo Review. This looks

like one of the few legitimate controver-

sies in audio (unlike the nonsense about

blind tests, tubes, etc.), and I am quite

open to all arguments. But, as in other

debates about all but the most obvious

audio phenomena, a number of reliable

practitioners have to be able to repeat

the same tests and obtain the same results. Maybe Tom Nousaine needs to

broaden his statistical base before com-

ing to a sweeping conclusion; maybe not.

(For one thing, he is not into classical

music; as I once told him, it's a case of

"Pop Goes the Weasel.")

The VMPS caveat sounds like sour

grapes to me, since they make and sell

only passive subwoofers. Why don't builtin crossover networks, whose large components and large boards are much more

prone to vibration than amplifier parts,

fall apart untimely? Why don't radios in

jeeps fall apart? Needless to say, a cer-

tain amount of care and competence in

construction and placement must be assumed in all such instances. Audio hypochondria is, of course, a proven marketing platform.

—Ed.

The Audio Critic:

...I...noted that David Rich made

reference to the Marantz CD-63 in his

footnote on page 16 of Issue No. 21.

However, I was disappointed to see that

he (Editor?) refers to the unit as "Philipsdesigned." Ordinarily, such a reference

would be taken as a compliment. Indeed,

in the Journal of the Audio Engineering

Society, I noted some years ago in their

regular review of audio patents that the

reviewer referred to Philips in the following way: "In many ways, Philips is the

audio equivalent of Mercedes-Benz. If

there is an esoteric way of doing things,

this is how Philips will do them." As I

seem to have misplaced the particular issue, I cannot say that the above is an exact quote, but it surely is very, very close

to the original comment.

In the case of the Marantz CD-63,

the model is in fact wholly designed

within the Marantz organization. Specifically, our chief CD designer, Mr. Yoshiyuki Tanaka, is the gentleman responsible for the CD-63 and most of our other

CD players. He has a strong technical

background in digital audio as well as

analog circuit design, including power

supplies, and is very familiar with a wide

variety of available devices, CD mecha

nisms, and the like. I have in the past forwarded to him articles of interest, most of

which have come from the pages of your

magazine.

5

pdf 6

Page 7

I am always pleased to see mention

of our gear in your magazine, and at Marantz we are always quite proud of the

Marantz association within the giant Philips concern, but I would ask that in the

future products submitted for review such

as the CD-63 be referred to as Marantzdesigned, as this is the reality. Philips per

se had nothing to do with the CD-63 design; however, we happily acknowledge

the fact that the CD-63 employs a number

of Philips-originated components, such as

the CDM12 mechanism, TDA1301 servo,

SAA7345 decoder, etc., that are also

found in Philips-branded models, as well

as models from other firms, such as Au-

dio Research....

As always, I appreciate your interest

in Marantz gear.

Best regards,

David Birch-Jones

Marketing Manager

Marantz America, Inc.

Roselle, IL

You'11 find that the review of the Ma-

rantz CD-63/63SE in this issue, essentially an updated leftover from Issue No. 21,

has been annotated to reflect your input.

That purely Marantz, non-Philips engineering seems to come up with products

that offer very solid performance per dollar. As for the articles you send to Mr.

Tanaka, I can understand why they are

from this publication, not from the digital

cloud-cuckoo-land of...well, you know.

—Ed.

The Audio Critic:

Having just completed reading the

review of the Magneplanar MG-1.5/QR, I

believe some important issues are raised.

Audiophiles know well that assessing

loudspeaker performance is difficult because it is to a large extent subjective.

Every loudspeaker design is a compromise, and no particular transducer technology has exclusive rights to accuracy.

Given your statements at the outset of the

review, some would question your "detached objectivity" in this case. It is clear

that you hold planar magnetic loudspeaker technology in low regard and this appears to have predestined your conclusions.

One of the generic criticisms of

Magneplanar designs made in the review

is the lack of low bass capacity. Your

nearfield measurements of the MG-1.5/

QR indicate its response extends to approximately 40 Hz. The farfield response

6

in my listening room is significantly

flatter than you suggest (±4 dB), and

there is usable bass down to approximately 30 Hz. Static distortion in the bass is

low (did you even bother to measure it?).

The conclusion that the MG-1.5/QR has

"not enough bass" doesn't follow, particularly when compared to other loudspeakers available at the same price.

The other major criticism presented

involves driver ringing. This has been

noted by others in the past and appears

to be related to the physical nature of the

driver. It has been described in a variety

of uniformly driven nonrigid drivers,

which include ribbon and electrostatic

systems in addition to Magneplanar drivers. The audibility of the effect has not

been established, to my knowledge, as it

relates to a farfield listening position.

Transducers with significant energy storage typically emphasize and smear consonants in the spoken voice and have

poor square wave response, neither of

which is true of this speaker.

As for the "not enough focus, too

much coloration" that is reported in the

review, I can only comment that in my

experience the MG-1.5/QR is an extreme-

ly revealing transducer that allows a

wealth of musical detail to emerge. A

common characteristic of neutral transducers is that each recording played

sounds different. This is exactly how

transparent the MG-1.5/QR sounds. Perhaps the Editor heard what he thought he

measured rather than the reverse.

None of the many conventional

loudspeakers that I am aware of in its

price range produces as wide, deep or

stable an image as the MG-1.5/QR. These

aspects of performance are not even discussed in the review. The LEDR tracks

from the first Chesky test disc provide an

effective and quick method of evaluating

the spacial characteristics of loudspeakers

in conjunction with the surrounding environment. Few loudspeakers can generate

substantial "height" with the vertical signal on the disc or provide an apparent

soundstage wider than the stereo pair.

With the MG-1.5/QR, the signal extends

to the ceiling in the vertical test and beyond the width of the stereo pair in the

horizontal test.

The rather cursory nature of your

loudpeaker reviews has concerned me

since I first subcribed to your journal.

Perhaps it is time for the Editor to apply

the same rigorous standards to loudspeak-

er reviews as Dr. Rich does with the vari-

ous electronic components he discusses.

May I suggest that in the future more of

the test results and discussion of the listening conditions (especially speaker

placement) be provided. It would also be

useful to have the manufacturers respond

to issues raised in the reviews. These

changes would allow the reader to better

assess the relative merits of each design

and reach his own conclusions.

Yours truly,

Dr. Douglas M. Hughes

Rochester, MN

I'm not surprised that the Minnesota

audio mafia finds staunch supporters at

the Mayo Clinic (or am I misinterpreting

your prefix and your address?), but you

happen to be mistaken on most of the

points you bring up. Not all of them,

though.

You 're right when you say that loud-

speaker evaluation is highly subjective,

although I try to back up my subjective

opinions with objectively verifiable evi-

dence. Furthermore, my subjectivity has

been refined over the years through exposure to literally hundreds of speakers—/

have some very good reference points of

subjective comparison.

You're also right in observing that

my loudspeaker reviews are not quite as

rigorous as David Rich's reviews of electronic components, but there are good

reasons for that. A typical electronic signal path in audio (such as, say, the left

channel of a power amplifier) has one in-

put and one output. It's relatively simple

and straightforward to examine the I/O

relationship. A speaker, on the other

hand, has one input and n outputs. Which

of the latter do we examine? Where in

space is the valid, or "official," output of

a loudspeaker system? How many points

in space are sufficient to give us an accu-

rate picture of the total output? These are

nagging questions of measurement methodology, and then there are the endless

other questions such as the physical

difficulty of ABX comparisons of speakers

(see Issue No. 20, page 39) and the various biases introduced by the reviewer's

accustomed listening room, etc. Rigorous

standards? We're working on them. Don

Keele is perhaps the most rigorous loudspeaker reviewer of us all, but then I do a

few tests that he doesn't. Amplifier-like

certainty in speaker testing we don't

have—and will not have soon.

Now then, here are the points where

you are wrong. (1) I do not "hold planar

THE AUDIO CRITIC

pdf 7

Page 8

magnetic loudspeaker technology in low

regard," au contraire, my MG-1.5/QR re-

view begins with "Yes, I have a soft

spot," etc., and later I enthuse over the

upper bass and lower midrange of the

Tympani IVa. (2) The lower bass of the

MG-1.5/QR is defined by the fundamental

resonance of 44 Hz; it may be that your

particular room happens to offer some

reinforcement down to 30 Hz, but the de-

signer can't count on that in my particu-

lar room. (3) My frequency response

measurement was anechoic (via MLS)

and therefore closer to reality than any

in-room measurement. I don't know how

you arrived at your ±4 dB in-room figure,

but it's irrelevant; no speaker designer

deliberately makes the anechoic response

nice and jagged in the hope that the room

will homogenize it. (4) The (true) ribbon

tweeter of the Tympani IVa doesn't ring,

so your generalization is incorrect. (5)

The audible effects of ringing depend on

the frequency but they are very real; having been deeply involved in speaker design as well as testing, I can only say I

wish you were right. (6) The MG-1.5/QR

does have poor square-wave response;

furthermore, ringing doesn't necessarily

affect the square-wave response unless

located near the square-wave fundamental or its odd harmonics. (7) Revealingness is a relative quality—revealing compared to what other speaker? (8) I listen

before I measure. (9) I did comment on

the excellent height and width of the

soundstage. (10) Just as a single exam-

ple, the ACI (Audio Concepts, Inc.) G3

speaker, reviewed in Issue No. 19, beats

the MG-1.5/QR on bass and just about

everything else, at less than two thirds

the price.

As for manufacturers' comments, we

publish every word of them unedited—if

they write us. I don't believe in letting

them preview the reviews, however; it

makes for fruitless preemptive hassles.

Final thought: your Magneplanar

MG-1.5/QR is every bit as good, or bad,

after my review as it was before it. You

are quite certain that it's a great speaker,

so why is it important to you that it

should be blessed by The Audio Critic ?

—Ed.

The Audio Critic:

Most, if not all, of the articles appearing in The Audio Critic are informative, so I would like to suggest that some

knowledgeable individual write a short

article on what qualities make something

ISSUE NO. 22 • WINTER 1994-95

sound live. When one walks into a dining

room or bar and hears a piano, it is easy

to tell with the first chord if the music is

live or is being reproduced, and sometimes even the make of the piano. It is

one of the reasons I have stopped going

to most concerts, as they seem to feel

they must use speakers, and therefore I'm

forced to listen to a loudspeaker (not necessarily a good speaker) and not the instrument itself. If I go to a concert I want

to hear the actual horn or piano or whatever. If I want to hear speakers, I can stay

home, as I've better speakers than they

use and far better sound.

I happen to be a collector of jazz

from the 1920s to the 1950s and still buy

78 rpm records when I find something in

very good condition that I want. I collect

these old records because many of these

recordings have not found their way onto

LPs or CDs. The bonus is that the music

on these 78 rpm records has more of a

live sound than LPs and much more than

CDs. I think Doug Sax touched on this

once. I truly believe, and hope, that I'm

not being influenced by the scratch and

noise common to these old records.

My cassette deck, a Nakamichi

680ZX, has a plasma display in place of a

VU meter or LEDs as level indicators.

When I copy a CD or even a 33-rpm LP

record onto a cassette, it is easy to see the

lighted portion of the display move from

left to right on drum rim shots or struck

piano notes (anything percussive). By

that, I mean one can easily see the lighted

portion travel from say -40 to 0 dB. Although fast, it's easy to see it move up

the scale with an increased level. When I

copy a 78-rpm record onto a cassette, it's

different. The music going from -40 dB

to 0 dB will result in the entire display,

up to 0 dB, instantly being lit. It is so fast

that one cannot see any movement of the

lighted display; it just appears. This instant change in level also happens if I

record the grand piano in our great room.

All of this is not as noticeable on LED

displays and completely obscured on VU

meters, as both are slow in comparison

to respond. Maybe that is why there are

so few plasma displays.

This leads me to believe that the attack time of a sound seems to have a direct bearing on how live it appears, and a

live sound is what we are all striving for.

Even when played through a 5 or 8 kHz

lowpass filter, 78-rpm records have a live

sound. To focus my question, why

doesn't a CD sound as live as a 78-rpm

record? By eliminating the compressors

and limiters and minimizing the active

stages and feedback, surely we should be

able to archive CDs that sound as live as

the old 78-rpm records of sixty years ago.

The added benefit of having no noise

would be wonderful.

I have every issue of The Audio

Critic, having read all of them at least

twice. Keep up the good work, as there

is so much #*%!# being shoveled out

there....

Yours truly,

Thomas F. Burroughs

Prescott, AZ

Aren't you the Tom Burroughs who

was selling Klipschorns in New York City

circa 1951? (I was very, very young then,

of course, and so were you.) If so, here's

some advice from one geezer to another:

Finagle yourself an invitation to a

live recording session (of a reasonably

competent label, I should add). Listen to

the direct sound of the musicians. That's

live, right? Now step into the monitor

room. (I'm assuming something a little

better than a telephone booth, and decent

monitor speakers.) What you now hear is

the CD sound (via the same l's and 0's

as will appear on the CD). How "live " is

it? Do you now feel that 78-rpm shellac

would sound more nearly like the live

musicians? I seriously doubt that you

would feel that after such an exercise. I

think you have lapsed into some kind of

technostalgia (to coin a word).

Of course, a superb 78-rpm recording from 1947, pressed on vinyl (which

they started to use around then) may

sound more "live" than an indifferent LP

from 1951, which in turn may sound bet-

ter than a botched CD from 1984 (they

had a few of those). But the best 78s versus the best LPs versus the best CDs? Get

out!

I have no idea what's with your level indicator—it could be any number of

things, including overload—but it isn't

attack time you're measuring. The leading edge of a dynamic peak is determined

by the high frequencies, and the 78-rpm

shellac medium was certainly not superior in bandwidth to LP and CD. As for

compression, yes, it can upset the applecart, but good CDs aren't compressed.

And, by the way, feedback (correctly

applied feedback) is not the bad guy.

That's a 1970s notion, meanwhile laid to

rest by some of the best minds in the engineering world. Gotta keep up with the

7

pdf 8

Page 9

times, old-timer. (Oops, what if you're

not that Tom Burroughs? What a burn...)

—Ed.

The Audio Critic:

I am a recent subscriber and I am

unbelievably happy to have found The

Audio Critic. I assembled a good system

for the first time in the last year, so I assume that I am the kind of person that

other magazines whine about needing to

recruit to save the "High End." Please allow me to give you my perspective as an

inquisitive novice.

After reading enough analog drivel

every month, I actually started to wonder

if I had made a mistake by selling my LP

collection 4 years ago, so I went down to

my favorite hi-fi dealer and compared a

CD player with a much higher-priced

turntable/cartridge combo. The CD front

end was so vastly superior in detail, dynamics, noise, and overall quality that I

remembered instantly why I smiled the

first time I heard a good CD system. I

also thought it was pretty darn musical

too, whatever that may be.

I am constantly bombarded with ar-

ticles recommending unbelievably expen-

sive wires, interconnects and, most re-

cently, magic wooden disks. I can't hear

a difference in controlled blind tests and

neither can the people that recommend

them, but if you don't agree with them

you are some kind of uncultured ignoramus. Isn't it convenient that the differences are supposed to be unmeasurable

things such as dynamic bloom and liquid-

ity.

I guess some people like distortion

in their music and that's why they love

those outrageously expensive vacuumtube amps. I think that the real reason is

that a lot of people went over to Grandpa's house as a kid, and his stereo glowed

in the dark. Now that they have six-figure

incomes they'll be damned if theirs isn't

going to glow too! It's a good thing we

have those East Bloc 1930s economies to

supply us with 1930s-technology vacuum

tubes.

When I entered the High End I had

no inkling that it was a fantasy world inhabited by mystics, romantics, and charlatans. The High End is hurting and attracts almost no women (another frequent

lament) because it is dominated by reviewers, retailers, and manufacturers that

are either greedy or foolish and have lost

touch with reality. I don't think a lot of

them realize how bizarre it looks from

the outside.

8

The Audio Critic is like a breath of

fresh air. I'm glad that logic, reason, and

facts have a proponent in the audio

world. Keep up the good work!

Darren Leite

Scottsdale, AZ

Everything you say is right on the

money, but you don't ask the sixty-fourdollar question:

Is the truth bad for business?

My answer is that, in the high-end

audio world, the truth is probably bad for

business this week and next month but

very good for business over the next ten

years. B.S. has a limited shelf life; given

sufficient time, most consumers tend to

switch to the truth. The tweako/weirdo

high-end promoters, however, don't think

that far ahead.

Thank you for your kind words.

—Ed.

The Audio Critic:

I would like to know if you have an

explanation for the fact that, in my system, the Parasound HCA-2200II sounds

noticeably better through its balanced inputs. I have a Parasound P/LD-1500 driving it, with 24' lengths of Straight Wire

Flexconnect (unbalanced) or Canare StarQuad (blanced). The levels are matched

to within about 0.2 dB, and out of 10

trials, single-blind (I was unaware of the

choices, but the switcher was), the difference was immediately apparent each

time.

Yours truly,

Rob Bertrando

Reno, NV

As David Rich's review in Issue No.

21 clearly explained, the simplistic input

buffer circuit makes the balanced-input

distortion of the Parasound HCA-2200II

more than an order of magnitude worse

than through the unbalanced input. The

distortion is probably still below the

threshold of audibility. Parasound has

acknowledged that there was some kind

of minor foul-up in the production version of the balanced input circuit, and we

were supposed to get a letter from John

Curl that would clarify the matter. We

are still waiting.

"Sounds noticeably better" is of

course a purely subjective opinion and

unprovable. "The difference was immediately apparent" is, on the other hand, a

provable statement and probably true in

your case.

Here are the possibilities that I see:

(1) The balanced-input distortion was

just above the threshold of audibility in

your unit, and you liked it. (2) The level

matching wasn't good enough ("about"

0.2 dB could have been 0.3 dB, which is

often perceptible), and you liked the louder or the softer choice. (3) The tweako

Straight Wire interconnect, which I'm not

familiar with, may introduce a rolloff or

other marginally audible inaccuracy, and

you liked it.

One thing is certain: the I/O relationship is more linear when the unbalanced input of the HCA-2200II is used.

—Ed.

The Audio Critic:

I am writing to respond to Mark S.

Willliamson's letter, as well as the excellent article on clock jitter by Robert W.

Adams, in Issue No. 21. First, Mr. Williamson states, "My only regret is that

some of the information is a little techni-

cal for those 'laymen' who are not part of

the engineering kingdom. I would be

grateful if you could dilute some of the

techno-lingo from time to time."

Williamson has been complementary to The Audio Critic as am I; however, the idea of catering to a less technical

(or nontechnical) readership sends shivers up my spine. Dilute? To what end?

I'm not trying to attack this man. I just

don't want you to do what he says. I have

been reading audio publications for 25

years, with a craving for the detailed articles and technical subjects that appear in

every issue of The Audio Critic. There

are many audio publications that are already diluted for those who have no

stomach for details. If I want serious,

scientific, technical analysis of audio issues, there are only two choices: TAC at

$24 per year, or pay hundreds for a professional journal such as that of the Audio Engineering Society (AES). I worry

that there will be continuous pressure on

TAC to broaden its appeal by deleting the

important details and writing for the marketers. I must admit to you that I am a

practicing electronics engineer with a

B.S.E.E. under my belt, so it figures that

the technical details would be much to my

liking. I do not wish to demean Mr. Williamson's comments at all, and am

pleased that he has joined the thinking

among us. The physics of the universe is

a complicated thing, and we as mortals

must use difficult technical language to

describe it with any accuracy at all.

THE AUDIO CRITIC

pdf 9

Page 10

Robert W. Adams's article on clock

jitter was simply outstanding, providing a

great analysis of the specifics of clockjitter effects on digital-to-analog conver-

sion. This is a good example of what I am

talking about. Mr. Adams is in a position

(as few are) to write this article. We need

just these kinds of articles in order to

really understand what is going on, and

what is important. David Rich has written

several detailed articles that spoke to me

as a designer and engineer, sending me

scurrying for my semiconductor data

books and reviewing circuit theory. Excellent. I have been waiting many years

for this kind of reading from the audio

press. Reading TAC is actually challenging for me. I get through a Stereo Review

in about 15 minutes, but TAC takes

weeks to fully absorb.

Diluted summary: If you change

anything I'm going to get really mad.

Clark Oden

Project Engineer

Frontier Engineering, Inc.

Oklahoma City, OK

Just how technical should a responsible audiophile journal be? It's a

difficult question. If we oversimplify, we

become superficial—and there are already plenty of other superficial audio

magazines. If we speak mainly to the E.E.

sensibility, we lose the vast majority of

our readers. We must strike a delicate

balance. As I've stated before, The Audio

Critic is not "My First Book of Electricity. " If you don't know what impedance is,

or what a FET is, you'11 have to find out

elsewhere. On the other hand, we aren't

the "Journal of the AES, Junior," either.

We try to keep the math to an absolute

minimum (although David Rich always

wants to sneak in more and more). I want

the reader who doesn't understand, say,

20% of what we publish to understand

the remaining 80% perfectly. That way

the 100% understanding can be expected

to come eventually. Our basic conclusions must be crystal clear to everyone—

and I think they are.

One thing we can do is to break out

the highly technical stuff in sidebars, so it

doesn't slow down the nontechnical reader of the main article. Sometimes the article is written in such a way that it's very

difficult separate the rough from the

smooth, but as you know we try to do it

when we can.

Don't worry, we don't intend to "dilute " our technical accountability. And I

agree completely with your beautiful sentence about the physics of the universe.

—Ed

The Audio Critic:

.. .Keep up the tweak bashing!

Seriously, I have been working on

two processes relating to digital audio

recently—sample-rate conversion and

noise-shaped dithering. In an effort to

find out what is really bearable vs. what

is measurable, I became sucked into the

audiophile-tweak world—I was con-

vinced my sound system wasn't good

enough because I couldn't hear characteristics I could measure. After all, these

golden ears doing reviews can obviously

hear the differences—right?

I found your magazine in time to be

rescued from a fate worse than death—

financial and otherwise. Thanks.

Regards,

Bruce Hemingway

Hemingway Consulting

dB Technologies, Inc.

Seattle, WA

It's useful to know what to say first,

right off the bat, to those golden ears who

claim to hear the differences you can't.

You say, "No, you can't hear that. You're

just telling me you can but you'll never

be able to prove it." That immediately

steers the discussion in the right direction

without allowing it to go off on some

highfalutin, abstract, pseudoscientific, psychobabble tangent—which is what I find

worse than death.

—Ed.

The Audio Critic:

To the little person "in the smallest

room of [his] house" [Issue No. 21, page

4]. The Editor gave you credit for writing, but we know it was copying, don't

we? You forgot the quotation marks on

"/ am... and ...behind me." Then you

forgot to give the composer Max Reger

credit for the quote.

You could have signed your name.

We would have understood the X.

Ron Garber

La Porte, IN

What an erudite subscriber! What a

sucker of an Editor! What a scummy

anonymous letter writer!

I looked it up, and you're absolutely

right of course. Here is what Max Reger

wrote to the Munich critic Rudolph Louis

in response to the latter's review in the

Münchener Neueste Nachrichten, February

7,

1906:

Ich sitze in dem kleinsten Zimmer in

meinem Hause. Ich habe Ihre Kritik vor

mir. Im nächsten Augenblick wird sie

hinter mir sein.

Translation: "I am sitting in the

smallest room in my house. I have your

review before me. In a moment it will be

behind me."

One must understand that in Europe

in 1906 the use of newspaper for hygienic

purposes was quite common. As for the

quip, Max Reger (1) obviously made it up

himself and (2) signed his name.

—Ed.

Coming:

A review in depth of the $19,000 Snell Acoustics Type A loudspeaker system,

along with other interesting speakers.

Reviews of high-quality surround-sound processors and preamplifiers, from

Lexicon, Marantz, B&K Components, and others.

The long-promised survey of FM tuners and indoor antennas (really!).

Still more reviews of power amplifiers and preamplifiers (they keep coming).

Further evaluation of perceptual coding technologies and hardware.

Some big surprises (you'll never guess).

ISSUE NO. 22 • WINTER 1994-95

9

pdf 10

Page 11

Paradoxes and Ironies of the Audio World:

The Doctor Zaius Syndrome

By Peter Aczel

Editor and Publisher

When the truth is so terrible that admitting it would surely make

the whole system crumble, ape logic demands denial and coverup.

Have you ever seen that marvelous 1967 sciencefiction movie The Planet of the Apes? If you have, you

will recall that it depicts a planet of the future where

English-speaking anthropoid apes are the rulers and

humans are speechless beasts of burden, enslaved by the

apes and despised as a totally inferior species. The apes

have horses and guns but no real technology. Doctor

Zaius, the subtle and highly articulate orangutan who is

this society's "Minister of Science and Defender of the

Faith" (he is played by the great Maurice Evans), knows

something the other apes do not: that humans in a past

era possessed not only speech but superior technology,

flying machines, powerful weapons, and so forth, all of

which served only to bring about their eventual downfall

and reduce them to their present condition. Doctor Zaius

fervently believes that any knowledge of this truth about

humans would totally destabilize the society of apes and

result in the end of their world. The ape dogma he fanatically protects, even though he knows better, is a blatant

denial and coverup of the actual history of the vanished

human civilization and a paean to the eternal superiority

of the ape.

I won't give away the rest of the plot to those of

our readers who haven't seen the movie and may want to,

but doesn't Doctor Zaius resemble certain key figures in

the high-end audio community? He knows the truth but

it's bad for the establishment. The system would come

crashing down if the truth were revealed. To pick an obvious example, consider John Atkinson, the subtle and

highly articulate editor of Stereophile. Don't you think he

knows? Of course he knows. But if he admitted that

$3000-a-pair speaker cable is a shameless rip-off or that

a $7000 amplifier sounds no different from a $1400 one,

the edifice of high-end audio would begin to totter—or so

he thinks (and may quite possibly be right). Consequently, he spouts convoluted scriptural arguments and epistemological sophistries, just like Doctor Zaius, in order to

pervert the obvious, uncomplicated, devastating truth.

There is a perfect illustration of this process in the

August 1994 issue of Stereophile, where Zaius-Atkinson

once again bashes blind listening tests in an "As We See

It" editorial. Such tests are of course considered extreme-

10

ly threatening by a publication that reports night-and-day

differences in sound which absolutely nobody can hear

when the levels are matched and the brand names concealed. He brings up all kinds of intricate flaws and drawbacks that may very well exist in some blind tests but

turns his back on the large number of blind tests in which

all of his objections have been anticipated and eliminated

and which nevertheless yield a no-difference result every

time. He knows very well, for example, that no one has

ever, ever proved a consistently audible difference between two amplifiers having high input impedance, low

output impedance, and low distortion, when operated at

matched levels and not clipped—but like Doctor Zaius

he conceals that knowledge. He'd rather collect rare case

histories of screwed-up blind tests than deal with the vast

body of correctly managed blind tests that undermine the

Stereophile agenda. (Just for the record, I'll state for the

nth time that there are only two unbreakable rules in

blind testing: matched levels and no peeking at the nameplates. To eliminate "stress," take a week or a month for

each test, send everybody else out of the room, operate

the switch yourself at all times, switch only twice a

day—whatever. The results will still be the same.)

A hard-nosed insight by the Weasel.

Our columnist Tom Nousaine (a.k.a. the Weasel),

in a recent conversation with me, stated his belief that

any longtime audio reviewer who has tested hundreds of

different audio components over the years knows exactly

what the truth is about soundalikes because it is utterly

impossible to escape that truth after so much hands-on

experience. It asserts itself loud and clear, again and

again. Therefore, he argued, the audio journalists who invariably report important sonic differences are most likely a bunch of hypocrites, i.e., exhibit the Doctor Zaius

Syndrome. I was strongly inclined to agree with him, but

then I said, "Well, what about Bob Harley?" We agreed

that Harley could be an exception. He may very well be

sincere because he just doesn't get it, not even after all

these years. Larry Archibald, on the other hand, is smart

and tough and definitely knows the truth, we felt. He is

probably the biggest Doctor Zaius of them all, ready to

THE AUDIO CRITIC

pdf 11

Page 12

make a monkey of any insufficiently enlightened audiophile. At the risk of offending against the principle of de

mortuis nil nisi bonum, I'm willing to venture the opinion

that even the late Bert Whyte and Len Feldman, regardless of their other important contributions, did a Doctor

Zaius number on certain audio issues rather than face the

wrath of the tweaks and the accusation of heresy. As for

Harry Pearson and company, who knows? Are astrologers, shamans, and witch doctors sincere or hypocritical?

As long as they don't try to usurp scientific arguments,

what difference does it make? And if they do try, they're

pathetically ineffective anyway.

A serious credibility gap.

In the same issue of Stereophile as the John Atkinson blind-test-bashing editorial, Larry Archibald views

with alarm the low bit-rate coding scene in an open letter

to Pioneer. He wants them to hold off on the implementation of the Dolby AC-3 coding standard for LaserDisc

because it may not be the highest-quality solution sonically. In other words, he suddenly doffs his orangutan

suit and shows concern for something that may actually

be true, i.e., audible.

Well, you blew it, Larry baby. You went ape—or

cried wolf, to mix my animal metaphors—so many times

about low-credibility tweako matters that on the Pioneer

level of big-money decision making you are no longer

taken seriously even when you may have a perfectly legitimate, nontweako argument. That's quite obvious

from the two replies by Pioneer executives printed in the

September issue, both of which basically tell you to relax, tweak boy, take it easy, and let the real experts get

on with their work—at least that's the way I read them.

You may conceivably end up being right, and Pioneer

wrong, about Dolby AC-3, but you're clearly wasting

your breath. (See also Tom Nousaine's column in this issue for a somewhat different perspective.)

By the way...

As I recently noted with a poignant sense of recognition, Stereophile's visual leitmotiv for blind testing is

the familiar three apes with hands on eyes (get it?), ears,

and mouth. Now you know why. It isn't just an art director's passing fancy. Doctor Zaius can feel right at home.

Why do I even bother to tell you all this?

All of our readers who have been with us for more

than just one or two issues are aware of my enormous

frustration on the subject of scientific truth in audio. The

very idea of a Doctor Zaius Syndrome, even it's only a

parody, suggests the existence of antiscience in audio as

a tradition, not just a momentary aberration—and a tradition it is, going back to the early 1970s, at the very least.

In the late '40s and throughout the '50s and '60s, whatever the most highly qualified and experienced engineers

said about audio was the accepted truth. Then came post-

ISSUE NO. 22 • WINTER 1994-95

modern irrationalism, post-Watergate anomie, fortune

tellers in high places, pyramid power, Jesus-haired

record-store clerks as self-proclaimed audio experts, untutored high-end journals, pooh-poohing of engineering

societies, derision of degreed academics—the B.S. era of

audio (and I don't mean Bachelor of Science). Today, the

melancholy truth is that tweako cultism has become

mainstream audio, at least above a certain price range,

and engineering facts are regarded as disturbingly radical

or at least eccentric. The scientific audio community has

been marginalized.

I despair at this point of a journalistic solution.

Even if The Audio Critic increased its circulation by a

factor of 50 overnight—I'm being deliberately absurd—

it might still be too late for the message. The cultists

have been too deeply indoctrinated and too long. The

pimply-faced kid in the Bon Jovi T-shirt who tried to sell

you AudioQuest Sorbothane Feet (the bigger kind) in

your local audio salon is not going to change his belief

system. Not in this antirationalist age and culture.

I can think of only one effective remedy. Many

years ago, long before our younger readers became interested in audio, the Federal Trade Commission put an end

to fraudulent power-output claims in amplifiers. Today,

the power-output specification must take the form of

"200 watts rms into 8 ohms from 20 Hz to 20 kHz at less

than 0.25% total harmonic distortion." Before then, the

same amplifier could have claimed 800 watts because it

could produce that for 2 milliseconds at 1 kHz into 2

ohms with 10% distortion. What if the FTC suddenly became interested in audio cable advertising, for example?

That chattering sound you hear comes from the teeth of

cable vendors at the mere mention of the possibility. And

that low, rumbling sound you hear is Doctor Zaius growling, "That's heresy!"

Anyone out there whose nephew or brother-in-law

is a young, crusading, Ralph-Nader-like employee of the

FTC? Get him interested!

* * *

P.S. Long after the above was written, just before

press time, I received a PR release from one of Stereo-

phile's flacks, hyping the magazine's willingness to tell

the "absolute truth" about a product even at the risk of

losing the advertising support of the manufacturer. The

latest editorial by Larry Archibald-Zaius simultaneously

proclaims the same lofty principle. The Velodyne

brouhaha is used in both instances as proof: they panned

the DF-661 speaker; Velodyne canceled all its ads; see

how incorruptible they are. Hey, you can't buy off the

Defenders of the High End Faith with a few ads when

they face the deadly threat of a midpriced super speaker!

"I [don't] see any reason...why a magazine

couldn't have both principles and commercial success,"

the PR release quotes Archibald-Zaius. "I've never had

even a second thought on the subject."

The monkey doth protest too much, methinks. •

11

pdf 12

Page 13

Loudspeakers Are

Getting Better and Better

By Peter Aczel

Editor and Publisher

The proof is in the recent designs that nudge the state of the art,

particularly in bass reproduction, but also in minimizing distortion

over the full range.

I can't say it often enough: if you already own a

fairly decent home music system, nothing can significantly change the quality of your audio life except

new and better loudspeakers. They are so much more im-

portant than preamps, power amps, CD players, etc.

What happens in most audiophile households, however,

is that the main speakers are firmly embedded in the living-room décor, so that any major change is subject to

vigorous spousal objection, especially if larger speakers

are contemplated. The typical audiophile then satisfies

his lust for shiny new equipment by buying, say, a new

preamplifier and persuading himself that the sound is

now much better, when in effect it hasn't changed the

least bit. It's a syndrome that depresses the hell out of me.

(Incidentally, I was recently exposed to a pair of

rather large loudspeakers packaged in a novel way that

could conceivably overcome spousal objection, even

though at first glance the speakers actually appear to be

larger than they are. The system, not yet sold anywhere,

is called the Applied Acoustics Model 10A and is the

brainchild of Jim Suhre, a Raytheon rocket scientist (really!), and Vic Kalilec, an electronics engineer, both from

Tennessee. What they showed me was a monumental

floor-to-ceiling wall system, the most salient feature of

which is its gigantic, seamless, curved tambour door.

Open the door and all your electronic equipment is in

there, including your large-screen TV. Close the door

and the whole shebang looks structural, not like audio

equipment. Jim Suhre claims that the curved tambour

acts as an ultrasophisticated dispersion device. I have my

reservations about that but can report that the sound had

exceptionally even spectral balance, from the lowest to

the highest frequencies. The speakers, when their floorto-ceiling grille is taken away, are revealed to be only

chest high; I'd say they have the overall impact of B&W

Matrix 803's or something along those lines. The drivers

and network appear to be of the highest quality. The

price was still up in the air when I looked; those who go

for this sort of thing will no doubt be able to afford it.)

12

ACI "Spirit"

Audio Concepts, Inc., 901 South 4th Street, La Crosse, WI

54601. "Spirit" floor-standing 2-way loudspeaker system,

$499.00 the pair (direct from ACI). Tested samples on loan

from manufacturer.

"In this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes," Ben Franklin wrote. That may

have been true in 1789, but today I would add: "and good

value from ACI." The combination of direct marketing,

conscientious design, and just plain common sense have

made Mike Dzurko's trademark synonymous with "more

speaker for your dollar." That's certainly true of a pair of

Spirits, which satisfy all the basic audiophile demands,

except for the deepest bass, at the totally unexpected

price of $499.

The speaker is a 32" high box with a footprint of

less than a square foot, housing an 8" woofer with polypropylene cone and a 1" aluminum-dome tweeter. The

woofer is aperiodically loaded with four small holes in

the back of the cabinet near the floor; the tweeter has a

plastic dispersion plug and is surrounded with felt. The

left and right speakers are mirror-imaged. The oak veneer

of my samples was of good quality.

The impedance curve of the Spirit shows the box to

be tuned to 50 Hz and the minimum impedance of the

system to be 6½ ohms (8 ohms nominal). Total impedance variation is between that minimum and 33 ohms in

magnitude and ±45° in phase. Any decent amplifier

should be able to drive such a load.

The quasi-anechoic (MLS) frequency response was

interesting in that both the woofer and tweeter were quite

flat, within ±2 dB or so, but the transition between them

in the 2 to 3.5 kHz range was not smooth, showing various irregularities of the order of 7 dB, depending on the

angle of measurement. Since all these irregularities were

basically minus (i.e., not peaks) and in the most sensitive

range of the ear, they may have acted as inadvertent zip-

THE AUDIO CRITIC

pdf 13

Page 14

piness suppressors. At this price, you can't expect the

crossover network to be too sophisticated; it appears to

be second-order, with out-of-phase wiring of the drivers.

The tweeter has a double resonance at 17 kHz and 24

kHz; otherwise it's quite smooth and remarkably clean in

response to tone bursts; there is no ringing at any frequency. The same is true of the woofer cone.

The nearfield response of the woofer shows the f

3

(-3 dB point) to be 50 Hz, with only a 12 dB per octave

rolloff below that frequency. That means useful response

down to 35 Hz or so. Can't ask for much more than that.

The sound of the Spirit is essentially neutral. That's

a simple statement but not a simple achievement. More

than a few extremely costly speakers don't sound neutral.

Transparency is good but not superb (what did you expect?). Dynamic range is very good. I didn't measure the

distortion because it's obvious from the drivers that it

can't be either very low or very high, and the process is

time-consuming; the sound, let me assure you, is quite

clean at high levels. All in all, this is a highly acceptable,

far from puny-sounding, musically pleasing little loudspeaker. I was demoing a very high-end speaker to a

friend, and then switched to the Spirits. The difference

was obvious but not very dramatic. Hey, for $499?

Bag End ELF Systems

S10E-C and S18E-C

(continued from Issue No. 21)

Modular Sound Systems, Inc., P.O. Box 488, Barrington, IL

60011. Voice: (708) 382-4550. Fax: (708) 382-4551. ELF-1

two-channel dual integrator electronics, $2460.00. S10E-C

black-carpet enclosure with single 10" woofer, $234.00 each.

S18E-C black-carpet enclosure with single 18" woofer, $658.00

each. Tested samples on loan from manufacturer.

I see this equipment in a slightly different perspective now that I have measured it and evaluated it at considerably greater length. I don't take back my original

statement that "I have never heard bass like this in my

listening room," but the reason for that was not the ELF

technology. It was the combination of the air-moving capability of two 18" drivers, flat response all the way

down into the 20-to-10-Hz octave, excellent damping,

and little or no dynamic compression—a combination I

hadn't previously experienced, as a total package, in my

listening setup.

I now believe that good conventional technology

could achieve the same results—even if it rarely does, for

various reasons. (See also David Rich's sidebar on the

subject and the Velodyne Servo F-1500R review below.)

Since an ELF-1 unit plus two S18E sub woofers plus two

high-powered amplifier channels could run into $5000 or

more, the question is whether or not the ELF approach

yields any substantive benefits in a domestic sound sys-

ISSUE NO. 22 • WINTER 1994-95

tern (as distinct from professional applications—see below) that are not obtainable by simpler means for less

money. My present feeling is that, from the stay-at-home

audiophile's point of view, the ELF system is "a solution

in search of a problem." That doesn't make it sound less

good than I said, but the I've-got-to-have-it factor is gone

because what makes it sound good isn't its uniqueness.

My measurements showed the S10E and S18E to

be almost identical in small-signal frequency response

when driven via the ELF-1 (with all switches down, the

most wide-open setting). The deviation from absolute

flatness is ±0.5 dB down to 20 Hz, dropping to -4 dB at

10 Hz. The Bag End literature shows curves for the S18E

that indicate -2 dB response at 10 Hz, which is more

consistent with an f3 (-3 dB frequency) of 8 Hz, the

claimed system cutoff. I see no reason to make a federal

case out of the discrepancy; the measured f3 of 12 Hz is

good enough for me. Of course, as the signal is increased, the air-moving and power-handling capability of

the S18E quickly passes that of the S10E; on the other

hand, multiple Sl0E's in a cluster could keep up with the

S18E in all respects.

The f3 also moves up, inevitably, as the level is increased; either the driver or the amplifier (remember, it's

boosted 12 dB per octave), or both, will reach a limit in

linear output capability. The ELF concealment circuit

deals with this very neatly (again, see sidebar); it is probably the cleverest and most original element of the total

system. You can crank the volume to any level you wish;

at some point when, say, the bass drum is thwacked, the

concealment threshold lights come on, but you hear no

distortion and are unaware of compression; it's smooth

as silk. You could argue, of course, that this is needed

only because the system has the inherent weakness of being based on tremendous electronic boost—one complicated mechanism to correct the side effects of another

complicated mechanism.

I measured the distortion of the Bag End subwoofers with the ELF concealment threshold set to leave the

circuit inactive at the levels tested (all switches down).

That way I was measuring the true electroacoustic accuracy of the equalized transducers. Needless to say, the

amplifier was at all times operating well below clipping.

On the whole, the distortion figures were not impressive. For example, at 30 Hz, as I gradually increased

the 1-meter SPL from 80 dB to 95 dB, the distortion of

the S18E as measured very close to the cone went from

2% up to 4%. At 40 Hz, the distortion over the same SPL

range varied between 1.1% and 1.7%. At 20 Hz, I measured 2.6% (80 dB) to 10% (95 dB). Compare that with

the Velodyne F-1500's distortion figures (see below) and

you'll begin to understand the design priorities of each.

The S10E has a very similar distortion profile down to 30

Hz but gets worse at 20 Hz, as you'd expect. Overall,

even the bargain-priced Hsu Research HRSW10 subwoofer (Issue No. 19, pp. 21-22) beats the Bag Ends on

13

pdf 14

Page 15

14 THE AUDIO CRITIC

What the Bag End ELF System Does and Doesn't

By David A. Rich, Ph.D.

Contributing Technical Editor

OK, here we are stuck in a sidebar

because of all the equations I want to use.

But do not worry; it really is not so complicated. The first thing we need is the

transfer function of a sealed-box-loaded

speaker:

The amplitude and phase of a loudspeaker's output are related to its input

signal through the system function that

governs its operation. For a sealed-box

system, this turns out to be a secondorder differential equation. The expression