Page 1

Issue No. 21

Display until arrival of

Issue No. 22.

Retail price: U.S. $7.50, Can. $8.50

Unconventional deployment of conventional drivers,

with superior results. (See the loudspeaker reviews.)

In this issue:

We present the definitive article for audiophiles on

the subject of digital jitter, written by one of the

world's top experts in response to the appalling

misinformation spread by the high-end audio press.

Your Editor reviews an unusually interesting and

varied assortment of loudspeaker systems.

We take a first look at the Sony MiniDisc system.

David Rich dissects analog and digital electronics

by Harman Kardon, Krell, Parasound, Sentec, et al.

Plus many other test reports, all our

regular columns, letters to the Editor,

and CD reviews by David Ranada.

pdf 1

Page 2

Contents

10

Clock Jitter, D/A Converters, and Sample-Rate Conversion

By Robert W. Adams, Analog Devices, Inc., Wilmington, MA

25

Loudspeaker Systems Using Forward-Firing Cones and

Domes: How Good Can They Get?

By Peter Aczel, Editor and Publisher

25 B&W Matrix 803 Series 2

26 NHT Model 3.3

28 Sequerra Model NFM-PRO

29 Velodyne DF-661 (quick preview)

30 Magneplanar MG-1.5/QR (dipole)

31 Bag End ELF Systems S10E-C and S18E-C (subwoofers)

33 MSB Acoustic Screens (acoustical accessory)

34

Analog Electronics: More Power Amplifiers,

Preamp/Control Units, and Mild Surprises

By David A. Rich, Ph.D., Contributing Technical Editor

34 Stereo Power Amplifier: Harman Kardon PA2400

36 Full-Function Preamplifier: Harman Kardon AP2500

38 Line-Level Remote Preamplifier: Krell KRC-2

41 Stereo Power Amplifier: Parasound HCA-2200II

44 Line-Level Preamplifier: Rotel RHA-10 (quick preview by the Editor)

44 Stereo Power Amplifier: Rotel RHB-10 (quick preview by the Editor)

45

Digital Electronics: More CD Players, D/A Processors,

Transports, and a First Look at the Sony MiniDisc System

By Peter Aczel, Editor and Publisher

& David A. Rich, Ph.D., Contributing Technical Editor

45 Outboard D/A Converter: EAD DSP-90000 Pro (Reviewed by Peter Aczel)

46 Compact Disc Player: Harman Kardon HD7725 (Reviewed by David Rich)

48 Outboard D/A Converter: Krell Studio (Reviewed by David Rich)

50 DAC/Line Amplifier: Monarchy Audio Model 33 (Reviewed by Peter Aczel)

53 CD/Videodisc Transport: Monarchy Audio DT-40A (Reviewed by Peter Aczel)

53 Outboard D/A Converter: Sentec DiAna (Reviewed by David Rich)

55 Compact Disc Player: Sony CDP-X707ES (Reviewed by Peter Aczel)

56 2nd-Generation MiniDisc Recorder: Sony MDS-501 (Reviewed by Peter Aczel)

57

High-Definition Thinking in Small, Furry Mammals

or The Weasel's Guide to Maximum Satisfaction

By Tom Nousaine

60

Hip Boots Wading through the Mire of Misinformation in the Audio Press

Six commentaries by the Editor

62

Recorded Music

A

Miscellany of CDs and Musical Videodiscs

By David Ranada (with a few additional capsule reviews by the Editor)

3 Box 978: Letters to the Editor

ISSUE NO. 21 • SPRING 1994 1

pdf 2

Page 3

Issue No. 21 Spring 1994

Editor and Publisher Peter Aczel

Contributing Technical Editor David Rich

Contributing Editor at Large David Ranada

Technical Consultant Steven Norsworthy

Columnist Tom Nousaine

Cartoonist and Illustrator Tom Aczel

Business Manager Bodil Aczel

The Audio Critic® (ISSN 0146-4701) is published quarterly for $24

per year by Critic Publications, Inc., 1380 Masi Road, Quakertown, PA

18951-5221. Second-class postage paid at Quakertown, PA. Postmaster:

Send address changes to The Audio Critic, P.O. Box 978, Quakertown,

PA 18951-0978.

The Audio Critic is an advisory service and technical review for

consumers of sophisticated audio equipment. Any conclusion, rating,

recommendation, criticism, or caveat published by The Audio Critic

represents the personal findings and judgments of the Editor and the

Staff, based only on the equipment available to their scrutiny and on

their knowledge of the subject, and is therefore not offered to the reader

as an infallible truth nor as an irreversible opinion applying to all extant

and forthcoming samples of a particular product. Address all editorial

correspondence to The Editor, The Audio Critic, P.O. Box 978,

Quakertown, PA 18951-0978.

Contents of this issue copyright © 1994 by Critic Publications, Inc. All rights

reserved under international and Pan-American copyright conventions. Reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited without the prior written permission of

the Publisher. Paraphrasing of product reviews for advertising or commercial

purposes is also prohibited without prior written permission. The Audio Critic

will use all available means to prevent or prosecute any such unauthorized use

of its material or its name.

Subscription Information and Rates

First of all, you don't absolutely need one of our printed subscription blanks. If you wish, simply write your name and address as legibly

as possible on any piece of paper. Preferably print or type. Enclose with

payment. That's all. Or, if you prefer, use VISA or MasterCard, either

by mail or by telephone.

Secondly, we have only two subscription rates. If you live in the

U.S., Canada, or Mexico, you pay $24 for four consecutive issues

(scheduled to be mailed at approximately quarterly intervals). If you

live in any other country, you pay $38 for a four-issue subscription by

airmail. All payments from abroad, including Canada, must be in U.S.

funds, collectable in the U.S. without a service charge.

You may start your subscription with any issue, although we feel

that new subscribers should have a few back issues to gain a better un-

derstanding of what The Audio Critic is all about. We still have Issues

No. 11, 13, 14, and 16 through 20 in stock. Issues earlier than No. 11

are now out of print, as are No. 12 and No. 15. Please specify which

issues you want (at $24 per four).

One more thing. We don't sell single issues by mail. You'll find

those at somewhat higher cost at selected newsdealers, bookstores, and

audio stores.

Address all subscriptions to The Audio Critic, P.O. Box 978,

Quakertown, PA 18951-0978. VISA/MasterCard: (215) 538-9555.

From the Editor/Publisher:

Issue No. 20 was optimistically dated Late

Summer 1993 but was mailed in the second

week of the fall. Unforeseen delays resulted

in one omitted quarter; hence the more

realistic Spring 1994 dating of this issue.

The staff expansion I so fondly previewed

is still in the incipient stage. With all the

reviews in this issue, it was suggested to

me that I split it down the middle to make it

into two issues (maybe I should have), or

label it a double issue in fulfillment of two

quarters of a subscription (I would never

do that). Yes, there will be a Summer 1994

issue, possibly even sooner than you think.

2 THE AUDIO CRITIC

pdf 3

Page 4

Box 978

Letters to the Editor

In the last issue your Ed. griped in this space about uninteresting letters seeking advice on purely

private purchasing plans (alliteration unintended). Now I want to gripe about reasonably interesting

but unpublishable letters that ramble on for seven or eight illegibly handwritten pages, propounding

the correspondent's opinions on eleven different audio subjects. What is the purpose of such a letter?

What am I supposed to do with it? Get a life, guys—or get a word processor. Letters printed here

may or may not be excerpted at the discretion of the Editor. Ellipsis (...) indicates omission. Address

all editorial correspondence to the Editor, The Audio Critic, P.O. Box 978, Quakertown, PA 18951.

The Audio Critic:

When making the suggestion that

Berlioz was worthy of joining "the 3 B's"

[Issue No. 17, p. 57], you likely never

knew that Liszt's disciple Peter Cornelius

coined the formula with Berlioz as the

third! Bülow signaled his revolt from

Wagner (who had earlier stolen his wife

Cosima, née Liszt) by purloining the

phrase to glorify Brahms.

Actually "the 3 B's" may be held

nonsense by Magyars, or other nonTeutons (such as I). So is your warning

that Berlioz's worst is probably worse

than Bach's, Beethoven's, or Brahms's

worst. Since Berlioz is the lone great

composer who was never granted full

"canonization" (which can account for

your electing him so shyly to "3 B" status,

and the rare event of Inbal's semicycle

recordings: he'll never be subjected to the

fashion), he still suffers from such preposterous slights, even from renowned

musicians (e.g., Celibidache and Nigel

Kennedy), which only an exceedingly bold

critic would make against the others.

Can you recall Tovey's remarks—of

which Haggin was so fond—that "neither

Shakespeare nor Schubert will ever be

understood by any critic or artist who re-

gards their weaknesses and inequalities

as proof that they are artists of less than

the highest rank," and that "the highest

qualities attained in important [my emphasis] parts of a great work are as indestructible by weaknesses elsewhere as if

the weaknesses were the accidents of

physical ruin." Tovey wrote that to exalt

Schubert against the shallow regard then

rampant but now all but extinct....

I don't overlook the fact that the music of Berlioz pleases you greatly. (A visitor to Wagner reported that he first said

that Romeo and Juliet's Love Scene, just

as wisely called the Adagio of Berlioz's

3rd Symphony, was "the most beautiful

music ever composed.") A superior critic

(and Nobel-winning novelist) of France,

Romain Rolland (also friend and correspondent of Freud!) enrolled Bach, Handel, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, and

Wagner as the finest of all composers and

claimed that after them he knew no other

who was superior, even equal, to Hector

Berlioz. Berlioz seemed incapable of the

vulgarity (or kitsch or bathos) which

afflicts German composers, and Brahms

especially (ever seen Cary Grant conduct

the Academic Festival Overture in Peo-

ple Will Talk?), and so became approved

and emulated in all Western music...

...While comparing one and another's worst and best, what is gained

from tallying pages, measuring the stacks

of bad and good? Yet you felt compelled

to indulge this pointless fancy at Berlioz's

expense....

Sincerely,

Owen M. Feldman

Elkins Park, PA

Ha! Fooled you all—didn't I?—by

beginning this column with a musicoriented letter rather than audio talk. My

main reason for doing so was actually to

contradict my preamble above with, shall

we say, the exception that proves the

rule. This letter came written in a small,

compressed hand on what appears to be

a legal-size yellow pad, then very badly

Xeroxed and the copy sent instead of the

original. I chewed my way through 3¼

legal-size pages of smeared, streaked,

gray mess and decided to publish about a

fourth of it because I found it interesting

and entertaining. I'm not taking back a

single word of my preambulary comments, but I guess I am a sucker for

knowledgeable music talk. It's certainly a

nice change from tweako audio talk. I'll

ISSUE NO. 21 • SPRING 1994 3

pdf 4

Page 5

even apologize for my churlishness anent

Berlioz's small lapses; on second thought

they're probably no worse than Bach's or

Beethoven's. Besides, a man who is even

slightly underwhelmed by Brahms can't

be all bad and should be humored.

-Ed.

The Audio Critic:

..."Accountability in audio journalism" and your no-nonsense, rational approach to product reviews are a refreshing change and a source of continuing

entertainment for me. David Rich is a superb find.

Regarding the MTM [mid/tweet/mid]

driver geometry, you are correct in that I

was not the first to use it (Issue No. 20,

page 42). To my knowledge the earliest

commercially successful use was by Koss

in a small 2-way system with 4" mid/bass

drivers. The choice of this geometry by

Koss, however, appeared to be largely

cosmetic. Meridian also made such a system about the time my paper appeared

["A Geometric Approach to Eliminating

Lobing Error in Multiway Loudspeakers,"

74th Convention of the AES, New York,

8-12 October 1983, Preprint 2000], but

again no mention of its superior polar response was made by them.

With Linkwitz's 1976 paper the

problem of polar-axis frequencydependent wander or lobing error became

widely appreciated. Linkwitz's solution

to the problem was to use inphase crossover networks. I was the first to demonstrate in the open literature that the MTM

geometry automatically eliminates lobing

error and to show the relationship between polar response and crossover order

for this geometry. I also designed several

commercially successful loudspeaker systems and system kits using this geometry.

Two of these systems were featured in

Speaker Builder magazine. The "Auditor

Point Source Aria Five," a Focal/JML

product which sold exlusively in Europe,

won the best loudspeaker of the year

award for 1991 from Hifi Vidéo (Paris,

March 1991). The MTM geometry is

now widely used and several manufacturers have attributed the concept to me in

their promotional literature. I believe it is

for these reasons that the MTM geometry

has become associated with my name.

Yours truly,

Joseph D'Appolito, Ph.D.

Andover, MA

Thank you for the compliments. Isn't

it remarkable that technologists with the

highest credentials, such as you, always

like us and that the scattered little enclaves of hostility out there are invariably

peopled by the technically untutored?

As for the MTM geometry, I myself

was the grunt of a design team (Bruce

Zayde, now with Hewlett-Packard, was

the whiz) that developed such a speaker

in 1984-85. It was called the Fourier 44

(because of the two 4½" mid/bass drivers) and shown at the 1985 Summer CES.

A few studio types and broadcasters are

still using it as a small monitor. We

didn't attach the D'Appolito appellation

to it, but conceptually the crossover was

along the Linkwitz/D'Appolito guidelines.

The speaker is currently extinct.

Audio designers have been known to

claim credit for work done by others, but

you are the first in my experience to disclaim, or heavily circumscribe, credit for

something the world has already fully

credited to you. That's what I call a class

act!

—Ed.

The Audio Critic:

Sorry, Charlie! This $24 is going to

Stereophilel I am sitting in the smallest

room of my house with your so-called

magazine in front of me. It will soon be

behind me. I'm sorry I ever wasted a cent

on your rag.

[—Unsigned]

The above anonymous and untrace-

able message was scribbled on a blank

copy of our pink form soliciting renewal

of an expired subscription and returned

to us in our business reply envelope at

our expense. I am publishing it as a clue

to the sociocultural/intellectual profile of

those who opt for Stereophile in preference to our publication. Such class! Such

wit! But such an awkward seat for letter

writing! (Needless to say, I washed my

hands after handling the form.)

—Ed.

The Audio Critic:

In Issue No. 20, Drew Daniels' letter

cited a transmission line's electrical

length as analogous to the phase shift in a

length of speaker cable. This is not true.

A speaker cable is in effect a lowpass

filter—your own curves in Issue No. 16

clearly show this. Depending on the LCR

of the cable, the driving impedance (amplifier), and the load impedance (speaker), the cutoff frequency could take place

within or, hopefully, above the audio

band.

The phase shift within the audio

band is determined by all of the above,

but generally will be capacitive (negative

degrees) at low frequencies, pass through

resistive (zero degrees), then become in-

ductive (positive degrees) at higher frequencies. In any case, even modest

lengths of any of the cables sold today

will exibit many degrees of phase shift at

the speaker terminals as a function of frequency. The only way to avoid power

loss, high-frequency rolloff, reduced

damping factor (drastic in some cases),

and phase shift (although I don't know

that this is important) is to use no speaker

cable. Your own suggestion to use mono

amps at the speakers' backs with short

jumpers is a most valid one.

Another subject: May I respectfully

decline to accept your request to contrib-

ute for the advancement of Bob Harley's

technical education? I find his "jittery"

stepping through technical issues very

amusing and entertaining. With more education he could become dangerous—

another Martin Colloms!

Don't give in to those who would

like you to compromise with the witch

doctors. Someone has to bring all the

hype to the forefront and it appears you

are the only one.

Sincerely,

Jefferson P. Lamb

Incline Village, NV

It seems to me that Drew Daniels

and you are talking about two different

things. He talks about phase shift as related to propagation speed in an unterminated wire, which is an abstraction; you

talk about a real-world hookup with an

amplifier output impedance plus wire

characteristics plus a complex load impedance presented by the speaker. Yes, of

course, with your givens your conclusions apply, but then the issue becomes

the sound of the amplifier/wire/speaker,

not just the sound of the wire due to its

length, which is the "moronic" subject

that incenses Drew.

Anent the SHEESH (Send Harley to

E.E. School in a Hurry) Fund, see the

"Hip Boots" column in this issue. Now,

what you don't seem to realize is that

Martin Colloms is actually two persons

existing in parallel universes. There is

the techie Martin Colloms, made of matter. There is the tweako cultist Martin

Colloms, made of antimatter. The two

4 THE AUDIO CRITIC

pdf 5

Page 6

cannot possibly get together because that

would cause a cataclysmic explosion annihilating Hi-Fi News & Record Review

and maybe even Stereophile. That's why

he is dangerous.

—Ed.

The Audio Critic:

"Dear" Peter,

Your continued hysterical, personal

attacks on me are entertaining as usual.

As is Ken Pohlmann's letter, which explains his affinity for you: he too is a petulant, name-calling infant. Why don't

you do this: survey the top LP and CD

masterers in the field—the folks who

have access to the master tapes and the

CD transfers. Ask them, as I have,

whether the CDs—especially those made

from an analogue tape—sound like the

original. And ask them whether they prefer the sound of a CD or a properly manufactured and played-back LP.

Ask Doug Sax, Bernie Grundman,

Greg Calbi, Bob Ludwig, Ted Jensen,

Stephen Marcussen, Steve Hoffman,

Howie Weinberg, Bill Inglot, etc. Ask

Grammy-award-winning engineer Roy

Halee (Paul Simon, etc.) about digital recording, or any of the dozens of veteran

recording engineers I've surveyed on the

subject. Some like digital, many don't.

I'd be happy to provide you with a list. [I

thought you just did.—Ed..]

Here's a good one: call veteran jazz

producer Michael Cuscuna of Mosaic

Records and ask him what happened

when, without alerting his customers, he

started releasing LPs generated from

"perfect" digitally remastered analog

source material. He'll tell you this: virtually all of them heard the deleterious effects of digitization and called to com-

plain.

Or better yet, reprint the following

so all five of your new readers [currently

a minimum of five new readers a day, Mi-

chael, but usually more—Ed.] can read

it:

Help Stop the Digital Epidemic!

It has become a mindlessly parroted truism in the world of commercial audio that digital recording is

the state of the art and the wave of

the future. At the same time, there

isn't a single audiophile-oriented

equipment reviewer, record producer or music critic who finds the

treble range of current digital recordings musically natural and enjoyable. The present technology of

50,000 samples per second with

16-bit encoding/decoding is sim-

ISSUE NO.21 • SPRING 1994

ply inadequate and mustn't be allowed to become the world standard. If you agree with us, start

writing letters to the record companies and commercial magazines

before it's too late.

Let's see, who wrote that? Could it

be...SATAN? NO. It's from The Audio

Critic, Spring through Fall 1980, and

judging by the tone I'd say you wrote it,

you opportunistic slug.

Cheers,

Michael Fremer

Senior Editor

The Absolute Sound

Sea Cliff, NY

If listing Senator Robert Dole as one

of the anti-Clinton Republicans constitutes a hysterical, personal attack on him,

then listing you as one of the antidigital

audio journalist—which was all I did (Is-

sue No. 20, p. 13)—constitutes a hysteri-

cal, personal attack on you. It seems to

me, however, that once again (see Issue

No. 14, pp. 9 and 51) you are the pot

calling the kettle black. Isn't calling Ken

Pohlmann "a petulant, name-calling in-

fant" an act of name-calling—both hys-

terical and personal? Weren't your re-

marks about him in the Winter 1993 issue

of The Absolute Sound, threatening to

vomit on him at a CES dinner, infantile,

personal, and name-calling? Let me do

some fact-calling: Ken Pohlmann has a

graduate degree in E.E.; you do not. Ken

Pohlmann is a professor at a major university; you are not. Ken Pohlmann is the

author of a basic textbook on digital

audio; you are not. Ken Pohlmann is a

Vice President of the Audio Engineering

Society; you are not. Shall I go on? Shall

I insult you with a spelled-out conclusion? I think that will be unnecessary.

As for your list of names—a couple

of them well-known, others less so—you

say "some like digital, many don't," so

what's your point? Which of them don't?

I can trump each digitophobic name you

bring up with three world-class names to

the contrary; it's a silly game. The point

is not who likes digital; the point is the

inherent accuracy, or lack thereof, of the

linear PCM technology and of A/D and

D/A conversion. That's an important sub-

ject that needs to be addressed repeatedly

and is the main reason I am answering

your trivial crank letter at such length.

No one claims, I least of all, that

everything that has ever appeared on CD

sounds great. There are plenty of opportunities to mess up between the first A/D

and last D/A stage in the recording and

playback chain; it used to happen often

but now it's much rarer. The basic question, and the only intelligent one, is this:

between a state-of-the-art DDD compact

disc and a state-of-the-art all-analog vinyl disc, each free from all the possible

technical goofs, which reproduces with

greater accuracy and fewer spuriae the

signal from the microphones? If anybody

thinks the answer is uncertain (as it is

not), let me add one other reasonable

constraint: 50 playbacks. Have I made

my point? If you eliminate the vinyl, the

picture changes; today's best analog and

digital master tapes can sound quite comparable overall, but the signal-processing

possibilities are much more limited with

analog, and as a storage format digital is

considerably more stable.

That brings me to my 1980 comments on "the digital epidemic." There

were no CDs in those days; the only

readily available examples of the new

digital audio technology were vinyl LPs

cut from digital master tapes. They

sounded pretty bad. I mistakenly attributed the bad sound to the digital process. I

was dead wrong, as later CD releases of

those same digital master tapes clearly

showed. It was the transfer to the LP medium that was bad because the engineers

who did the transfers initially refused to

deal with the differences in high-frequency

energy and dynamic range between analog and digital master tapes. I had no

idea how the digital tapes sounded in the

control room at the recording sessions. I

jumped to the wrong conclusion, and my

advisors at the time were no smarter.

Have you ever jumped to the wrong conclusion, Michael?

As for "opportunistic slug"—boy,

that's a muddleheaded, inept insult. What

opportunities does a snail without a shell

exploit unfairly? What undeserved advantages did I gain by repudiating and correcting my early perceptions of digital

audio? You, sir, are a very lightweight

polemist.

—Ed.

* * *

Epilogue: At the Winter CES in Las

Vegas early in January, Michael Fremer

deliberately staged a loud, public,

fishwifely confrontation with me for the

benefit of visitors to the Velodyne exhibit.

It was uncalled-for and embarrassing; I

later had to clear the air with David

Hall, Velodyne's boss, who is a softspoken gentleman unaccustomed to the

5

pdf 6

Page 7

streets-of-New-York type of vulgarity. I

tried to calm Michael by telling him that I

did not consider him to be an evil person

but just someone with absurd ideas, but

he kept loudly accusing me of "ad hominem attacks" (his editor, Harry Pearson,

also loves that phrase) and looking

around for group approval. I then made

the mistake of tossing off a small pedantic joke. I asked, "Who was the homo in

hominem?" Then I added, "You know,

hominem is the accusative of homo, re-

quired by the preposition ad." Michael

did not get the Latinist jest. His confused

reaction indicated that all he had heard

was the word homo, and I'm not even

sure he knew it means man. That will

teach me to make gratuitous scholarly

noises where the cultural tone is New

York candy store. Indeed, that will teach

me to have any kind of commerce with

the Fremeroid element in the audio world.

The Audio Critic:

It's been roughly two years or so

since my departure from "tweako/voodoo

salon" land, and I owe thanks to you and

your staff for the insight and knowledge

you share through The Audio Critic. It's

amazing what science and a little common sense can do for the soul. As the

song states, "I was once blind but now I

see!" My only regret is that some of the

information is a little technical for those

"laymen" who are not a part of the engineering kingdom. I would be grateful if

you could dilute some of the techno-lingo

from time to time.

Throughout the years, I've noticed

that many audio magazines rarely even

mention the name McIntosh. The company has been around since 1949 and has a

solid reputation for reliability and quality,

just like Krell, Bryston, etc., yet the

tweaks hardly touch it. Why? The design

(external appearance) may be a bit out of

date for some, but the internal components hardly seem archaic. According to

the principles presented in your publication, if the McIntosh amps operate within

their given parameters, then they should

sound no different than a Krell or Boul-

der. Thus, these amps should be highly

regarded and recommended, unless

there's something I've missed. How

about The Audio Critic, in a future issue,

taking the opportunity to test a McIntosh

amp. I would love to see how it compares

to some of the other big boys on the

block....

Please keep up the excellent work.

6

Your magazine lights the path for many

in a confused and disturbed audio world.

Sincerely,

Mark S. Williamson

Washington, D.C.

/ blush because your words of praise

make me appear to be something close to

a spiritual leader, a responsibility I re-

fuse to shoulder. (Lenny Bruce once said

that anyone who calls himself a religious

leader and owns more than one suit is a

hustler. I own two suits.)

McIntosh is indeed an interesting

company. You are quite right; they make,

and always made, beautifully engineered

equipment. During their long years under

the leadership of the late Gordon Gow,

they kept their dialogue with the high-end

audio press to a minimum, probably be-

cause they felt that with their thoroughly

established reputation and highly supportive dealer network they had nothing to

gain from a good review but something to

lose as a result of an irresponsible tweako

hatchet job. Hey, they were probably

right.

About two years ago the picture

changed somewhat. The firm is now

owned by the Japanese; the new management is not from the high-end audio

world and is gung ho on marketing, PR,

the whole big-business canon. They have

a new car-audio line, among other

things. So far, from where I'm sitting, I

can discern no compromise whatsoever

with traditional Mcintosh engineering or

product integrity, and the party line is

that there will be none. Amen. They are

definitely cozier with the audio press,

however; you will undoubtedly see more

reviews, and I think that will include reviews in this publication. Based on what I

already know, I expect their power ampli-

fiers, especially, to do very well in engi-

neering shootouts with some of the sacred

cows of the High End.

—Ed.

The Audio Critic:

I just read my first issue of The Audio

Critic (No. 20). I can only say that I have

been looking for this type of coverage of

the audio industry for several years and

have found it only in this one publication.

I first became involved in audio as a teenager in 1966, working in what was then a

"high-end" audio store in San Francisco.

I have remained interested and involved

ever since.

I have been an avid reader of all the

popular audio publications over the years

except for Stereophile and The Absolute

Sound (by the time I discovered these last

two, they had become too involved in beliefs in the superiority of older tube and

analog equipment for my taste). I have

had a subscription to Audio since the late

'60s. In recent years I have become highly disillusioned with the direction of most

publications and audio salons. So-called

"high-end" audio is becoming more and

more an exercise in frustration rather than

the source of pleasure it should be. We

are not told what sounds good but rather

what is wrong with the sound of just

about everything out there except maybe

one of those $150,000 all-out high-end

systems. There is far too much emphasis

on the cost of components and how cost

is related to "sound quality," even though

most high-enders will deny it.

At one time I was going to be an au-

dio engineer. I chose instead to become a

psychologist but have never left my

scientific orientation. As a result, I have

become what might be termed a psychology critic. I have remained true to only

empirically based studies of behavior and

have taken many courses in research design and statistics. There are some interesting parallels between psychology and

high-end audio, the most obvious being

the lack of empirical support for the assertions that are so commonly made. Psychology always has been and continues to

be filled with interesting but often worthless theories that become the basis for interesting but often worthless therapies.

As in high-end audio, the public can spend

hundreds of thousands of dollars on tech-

nologies (therapies) that are of dubious

value.

I had become so frustrated with the

audio scene over the last year or so that I

was hardly even reading anything anymore. In trying to purchase some audio

products during this same time, I was

convinced to buy some products by an

audio salesman, which turned out to be a

big mistake. Luckily the store that had

sold them to me was happy to give me

my money back when I returned them un-

happy. However, this was for accessories

like cables, not big-money items like

speakers, amplifiers, or preamps. I even

got into a big argument with a salesman

about the purchase of a Toslink cable for

copying CDs onto DAT. I was told that

several other products were far superior

and "what I really wanted was..." What I

really wanted was a Toslink cable! Dur-

THE AUDIO CRITIC

pdf 7

Page 8

ing the argument, I heard things like

"...but according to Robert Harley...." I

am not an engineer but I was skeptical of

Mr. Harley's qualifications based on

many statements he had made in Stereo-

phile. The salesman exhibited his own ignorance when it became clear that he did

not know what a gound loop was. I became so angry at the salesman's persistence and ignorance that I left the store

and returned later to buy my Toslink

cable from another salesman (this was the

only store in town that carried the cable).

Some of your readers have written

to suggest that you cease your "tweak

bashing" and "ignoramus hunting." I

have written to both The Absolute Sound

and Stereophile over the years to criticize

their views on various topics, but mostly

to point out their lack of understanding of

scientific methods (mostly Stereophile).

The Absolute Sound published two of my

letters but "disqualified" my point of

view in print by pointing out how inferior

my equipment was and claiming that I

would not be able to hear the things they

were talking about with such equipment.

Stereophile has never published or acknowledged any of my letters. Like The

Audio Critic, I have tried to write letters

to Stereophile that were "unanswerable,"

after my experience with The Absolute

Sound.

The Audio Critic appears to be the

only publication I am aware of that takes

a truly serious approach toward the eval-

uation of so-called high-end components.

Given the prices some of these components currently have, such a serious

approach is really needed. Just as importantly, given the pervasive misconceptions about high-end audio components

that exist today, the "tweak bashing" and

"ignoramus hunting" in The Audio Critic

probably does not go far enough. I'm not

suggesting that more attacks are needed,

but that more clarification is needed and

somehow outside of this one publication.

Audio should not be the "sport" that Anthony Cordesman so often refers to it as

(sport in that context seems to denote the

constant trading of usually expensive

equipment in the never-ending quest for

perfection, and the fun of debating the

theoretical issues) but rather a means to

enjoy music outside the concert hall with

as much realism as possible at an affordable price and without having to have a degree in electrical engineering. As an

aside, I can no longer wade through what

I call the "high-end babble" that so per-

ISSUE NO.21 • SPRING 1994

vades Mr. Cordesman's reviews in Audio.

Sincerely,

Chuck Butler

Kalamazoo, MI

Your comparison of psychology and

high-end audio is right on the money.

You haven't told us, however, how a layman in search of effective therapy can

distinguish, and navigate, between the so-

phisticated empiricists and doctrinaire

theoreticians in your profession—it's a

tough question, isn't it? In audio, the answer to the analogous question is implicit

in your complimentary remarks: every

man, woman, and child who owns more

than three CDs should have a subscription to The Audio Critic, right?

—Ed..

The Audio Critic:

Tom Nousaine, for whatever reason,

seems incapable of accurate reportage

about me or my views. Having given to

the readers of The Audio Critic a distorted picture of our not unpleasant encounter at the Stereophile High-End Show last

year, he then compounds his errors by

perverting some perfectly clear statements from Professors Greiner and Lipshitz on the audibility of absolute polarity. I beg to set the record straight on these

latter facts.

"[Lipshitz's] results were significant

only when trials using test tones were included in the analysis," Nousaine says.

On the contrary! Listen up:

[Here follows a series of referenced

quotations from the writings of Lipshitz,

Greiner, Richard Heyser, et al., with

pithy anti-Nousaine comments by the letter writer. The trouble is that the quotations are heavy-handedly selected, excerpted, and edited with massive ellipses,

omitting the qualifying words, phrases

and sentences, falsifying the context as

well as the chronology, and not contradicting Nousaine's highly specific statements at all. It would take an additional

page, or more, to include this obviously

manipulative "documentation" here, and

I refuse to do so.—Ed..]

...Such results [as quoted above]

are difficult for those in the Nousaine

camp to swallow, for commonly they

judge others by what their own ears can

hear, or cannot. Always a mistake. Yet

one may still enjoy beholding their verbal contortions as they chew the truth

about polarity served up by every legitimate researcher on record. Dead to rights,

we have them here: in denial, every one,

about a fabulous free fix. Will Tom throw

in the towel at last? How about all the audio critics he has helped lead astray? Stay

tuned! Find out whether "the muffling

distortion" (my term) will later be proclaimed over this same station.

Finally, regarding reader Donald

Scott's recent letter dissing the undersigned's "cranky" advocacy of polarity as

"the cow chip effect": the errors in his

experiment to disprove polarity are so

rife and obvious, I must invite the poor

soul to write for a free copy of my explanatory book The Wood Effect, and

that's no bull.

Clark Johnsen

The Listening Studio

Boston, MA

/ have made an exception here to my

"no further soapbox opportunities for

Clark Johnsen" policy as stated in Issue

No. 18 because your letter—in which

you're up to your usual tricks of creative

documentation—provides me with an op-

portune lead-in to unedited quotations

from Lipshitz and Greiner for the benefit

of our readers, showing them what these

researchers really meant.

The following is an uninterrupted

and unedited quotation from S. P. Lipshitz,

M. Pocock, and J. Vanderkooy, "On the

Audibility of Midrange Phase Distortion

in Audio Systems," J. Audio Eng. Soc. 30

(September 1982): 580-95 (your own favorite reference).

...On normal musical material

heard via loudspeakers in an average listening room, we have not

thus far detected the effect of midrange phase distortions of up to

two cascaded all-pass networks of

Q 2 2. We do not have evidence

to conclusively demonstrate whether phase distortions of this amount

can be heard in normal reverberant

loudspeaker listening to normal

musical or acoustic transients

(which are largely oscillatory in

nature), but it is clear that the effect, if audible, is extremely subtle.

More work needs to be done in

this area, so that transducer designers can make an intelligent decision on the significance (not the

existence) of phase effects.

Finally, we wish to caution

most strongly against quoting our

results out of context. All the effects described can reasonably be

classified as subtle. We are not, in

our present state of knowledge, advocating that phase linear transducers are a requirement for highquality sound reproduction. More

7

pdf 8

Page 9

research is necessary. We do not

wish the research outlined above

to suffer the same misunderstandings, distortions, and misapplications as have occurred in recent

years with transient intermodulation distortion. We feel that listening rooms will become more

anechoic as more sophisticated reproduction systems become available. Thus the increased audibility

of the phase effects which we have

found with headphones may in the

future apply also to loudspeaker

listening.

So much for what Lipshitz, unfiltered

through Johnsen, wants us to understand.

As for Greiner, here is an uninterrupted

and unedited quotation from R. A. Greiner and D. E. Melton, "A Quest for the Audibility of Polarity," Audio 77 (December

1993): 40-47.

While polarity inversion is not

easily heard with normal, complex

musical program material, as our

large-scale listening tests showed,

it is audible in many select and

simplified musical settings. Thus,

it would seem sensible to keep

track of polarity and to play the

signal back with the correct polarity to insure the most accurate possible reproduction of the original

acoustic waveform.

Authors' Addendum: The work

presented here was done in 1991.

(It is now September 1993.) Since

then, there has been some, but not

much, progress made in establish-

ing polarity standards in the recording industry. This work is continuing at the present time. There

has been some discussion in hi-fi

publications and much anecdotal

reporting, in various publications,

on the audibility of acoustical polarity inversion. There has been

nothing noteworthy in the professional literature, however, that clarifies the issue or "proves" that audibility of polarity inversion is a

major factor in listening enjoyment. While it is not clear why this

is the case, several factors might

be: The difficulty of doing the experiments in a controlled way, as

evidenced by this work; the fact

that the effect of polarity inversion

is small in most program material,

or the fact that the effect seems to

be small compared to the many

other variables in the recording/

reproduction processes (microphone use, room acoustics, electronic processing, and the like).

Nevertheless, it seems reasonable

that at some point another step toward achieving greater audio

fidelity will be maintaining polarity of the signals throughout the

record/reproduction chain.

To sum up, what Lipshitz and Grein-

8

er are really telling us is: yes, it's better

to pay attention to polarity than to ignore

it, but no, it isn't a big deal from a listening point of view. In other words, Clark,

the horse you are trying to ride to the

higher reaches of the audio world, while

a real horse and not a donkey, is a rather

slow and somewhat lame mount, unlikely

to get you there. Why don't you trade it in ?

Lastly, the perpetrator of the phony

"triple-blind" listening test (see Issue

No. 17, pp. 44 and 47) is in no position to

reprimand Donald Scott or anyone else

about experimental errors. Get your own

act together, Clark, and until you do,

please don't write us again. (Maybe you

should move to Warsaw, where you could

really experience Absolute Polarity.)

—Ed.

The Audio Critic:

.. .I have been pleased by the professionalism of your reviews, and I am renewing [my subscription] primarily because I am interested in seeing how your

publication evolves with the contributions of your new editors. I have more

than enough things to read in my professional life, and I am less interested in rigid publication schedules and first-class

mailings than I am in high-quality, analytic criticism. If you were to conduct a

reader survey, I would give the following answers:

I became aware of your publication

from an ad in Audio. I subscribed because

I had received a gift subscription to Ste-

reophile and I felt that I needed an anti-

dote to the logorrhea and what you refer

to as "tweakism." That subscription has

now lapsed, and I am continuing with

you, partly to understand better which

parts, circuits, and features are essential

to quality construction and which are not.

Most of my equiptment was purchased

between '77 and '82 and is still performing reliably. I am not "looking for something to buy."

I have followed with some interest

the pleas for "tolerance of opposing

views" and finding "a halfway ground" of

agreement. I am a Radiation Oncologist. I

would not recommend any course of therapy without first evaluating prospective

double-blind studies. This is how I generate my professional opinions, and I will

not give any weight to the opinions of

those who do not go through a similar

process. Subjectivism in medicine can be

deadly. It has no place in any of the physical sciences. Some understand this; some

do not. I do not tolerate unprofessional

opinions in my field and would never ask

you to do so in yours.

Vincent Capostagno, M.D.

Merced, CA

Readers of The Audio Critic are

rather sharply divided into the categories

of those who want to learn something

(such as you) and those who want to buy

something. We try to satisfy both mindsets; what we refuse to do (although

there is a demand for it) is to rattle off a

long laundry list of buy-this, don't-buythat recommendations without documenting the reasons.

I would like to expand on your

"some understand this, some do not" observation regarding scientific objectivity.

I have come to the tentative conclusion

that some have a natural gift for undestanding the basic essence of the scientific method, requiring perhaps only a

good junior-high-school course in General Science to assimilate the idea, and that

others are color-blind or tone-deaf, so to

speak, to the scientific mode of thinking,

although otherwise intelligent and re-

peatedly exposed to the best scientific

influences. That would explain the immense stubbomess and impenetrability of

some far-from-stupid members of the

audio community on the subject of "I can

hear it" vs. "I can prove I can hear it,"

when the distinction is obvious to enlightened twelve-year-olds.

—Ed.

* * *

/ also want to respond here collec-

tively to a whole bunch of correspon-

dence—long, well-written, laser-printed

letters as well as illegibly scribbled,

barely coherent ones, both long and

short—in which the common theme is

audible differences between various pieces of equipment and the common failure

is a disregard for the need to eliminate

observer bias and the placebo effect.

There is no point in publishing any of

these letters; we would just be going

around in circles, repeating over and

over again that without blind listening

tests at precisely matched levels all such

discussions are meaningless. How many

times do we have to reiterate that selfevident precept before it sinks in, without

any of these "yes, but" arguments? Or is

there anyone out there who actually believes that unmatched levels and peeking

at the nameplates will get you closer to

the truth? That I can't deal with. •

THE AUDIO CRITIC

pdf 9

Page 10

ISSUE NO. 21 • SPRING 1994 9

In Your Ear

pdf 10

Page 11

A Moderately Technical Tutorial for the Serious Audiophile

Clock Jitter,

D/A Converters, and

Sample-Rate Conversion

By Robert W. Adams

Analog Devices, Inc., Wilmington, MA

Forget everything you have read in the "alternative" audio journals

on the subject of digital jitter and start from scratch here with the

correct scientific foundation.

Foreword by the Tech. Ed.:

"The Jitter Game"

I have used the same title for this

foreword to an important article on

jitter as Stereophile's Robert Harley

uses for his articles on jitter, but with

a different meaning. Harley is playing a game of pretend engineering

when he attempts to analyze the jitter

of a CD player and correlate the resultant measurement to the sound

quality he perceives. Why does Harley spend so much time on jitter? Because he thinks that it strongly correlates with the sound quality of the

equipment. Since open-loop (i.e.,

nonblind) listening tests are subject

to externally originating listener

bias, it is easy to see how he can delude himself to arrive at such a conclusion. Stereophile is unfortunately

quite influential, and jitter has thus

become in the early '90s what TIM

(transient intermodulation distortion)

was in the late '70s and early '80s.

But Harley has a huge problem

because clock jitter cannot be measured directly at the output of a black

box. The effects of jitter can be assessed indirectly from black-box

measurements, but in a correctly designed CD playback system these

effects are commingled with, and

usually swamped by, noise and distortion products. Indeed, in exotic designs, the loony-tune analog stages

are so riddled with noise and distor-

tion that even large amounts of jitter

would have little effect on the measurements. To overcome this prob-

lem, Harley plays his little game. He

takes off the cover, gets inside the

unit, and attempts to measure the jitter on the internal clock line. Now,

two problems exist when he does

that: (I) since jitter is an internal parameter, its effect on the external

performance of the system is depen-

dent on other aspects of the system's

design, so it is not possible to com-

pare the measured results directly

between two models under test; and

(2) measuring clock jitter is a nontrivial task, subject to many errors

even when conducted by one skilled

in the art.

Note that Harley could continue

to play his game and make other

measurements while he has the cover

open, such as I/V settling time, power-supply rejection ratio, the amount

of closed-loop feedback, powersupply output impedance, etc. All

these parameters could affect the

sound quality, and under Harley's

rationale—that being unable to ob-

serve the effect of such parameters at

the output of the system does not

mean they do not affect the sound

quality—one could ask why he

doesn't make these additional measurements. My contention is that

Harley would indeed make these

measurements, and then delude him-

self into thinking they were remarkably revealing of sound quality, if

some manufacturer delivered to him

a test system for a given parameter

and showed him step by step how to

use it.

Jitter and its effect on the performance an electrical system is a

difficult subject, truly understood by

only a few experts involved in the design of systems sensitive to jitter. As

a result, much misinformation on jit-

ter has been circulated in the press,

originating from manufacturers' press

releases reproduced without any

competent review. In an attempt to

clear the air on the subject, we commissioned an article by a genuine ex-

pert in the field of digital audio, Rob-

ert W. Adams, of Analog Devices,

Inc. This article is based on a paper

Adams presented at the 95th Convention of the Audio Engineering Society

in New York last October. (The pre-

print number was 3712.) Bob Adams

is perhaps the youngest Fellow of the

AES (the highest honor awarded in

the field of audio engineering), and

his many pioneering achievements in

digital audio at AD, and before that

at dbx, are too numerous to be summarized here. His investigations in

the field of jitter reduction have resulted in a new method to attenuate

jitter, a practical asynchronous sample-rate converter chip, which is explained in his article. Before this

10 THE AUDIO CRITIC

pdf 11

Page 12

chip, asynchronous sample-rate con-

verters could be had only at very

high prices and in many cases did

not perform very well. Since the new

Analog Devices ASRC chip is all-

digital, it offers the potential for the

easier and cheaper implementation

of a jitter attenuator than a multiple

phase-locked-loop S/PDIF decoder.

As I said, this is not an easy subject, and the article below is not simple. The problem again is that we

are trying to explain how an internal

system parameter affects the total

system performance. If Harley had

not made jitter his hobbyhorse, we

might not have found it necessary to

run such a complex article. But given

the current trendiness of jitter in audio journalism, I think it is important

that the serious audiophile try to go

through the article in order to separate the facts from the fictions the

high-end charlatans are trying to legitimize. If nothing else, this article

will acquaint you with the complex

interrelationships involved in the digital design process. Note that while

Bob Adams has simplified as much as

was possible without leaving out the

essentials, anybody who attempts to

measure the performance of an

S/PDIF decoder, let alone design

one, had better have a much more

complete knowledge of the subject.

Indeed, it is not possible to read the

professional literature in this field

without a strong background in sig-

nal processing, modulation theory,

and random process.

Unfortunately, it is not clear

whether Robert Harley understood

Adams's AES paper from which the

present article is derived. In the Jan-

uary 1994 issue of Stereophile he

wrote that "the paper stated that a

converter's jitter sensitivity is a function of the clock frequency and oversampling rate. This conclusion con-

firms the validity of our technique of

expressing clock jitter as a proportion of the clock frequency." Read

Adams's simplified but thorough explanation below and judge for yourself whether that's what he is really

saying.

This article does not discuss the

S/PDIF encoding and decoding process itself; that discussion is planned

for a future issue.

—David Rich

ISSUE NO. 21 • SPRING 1994

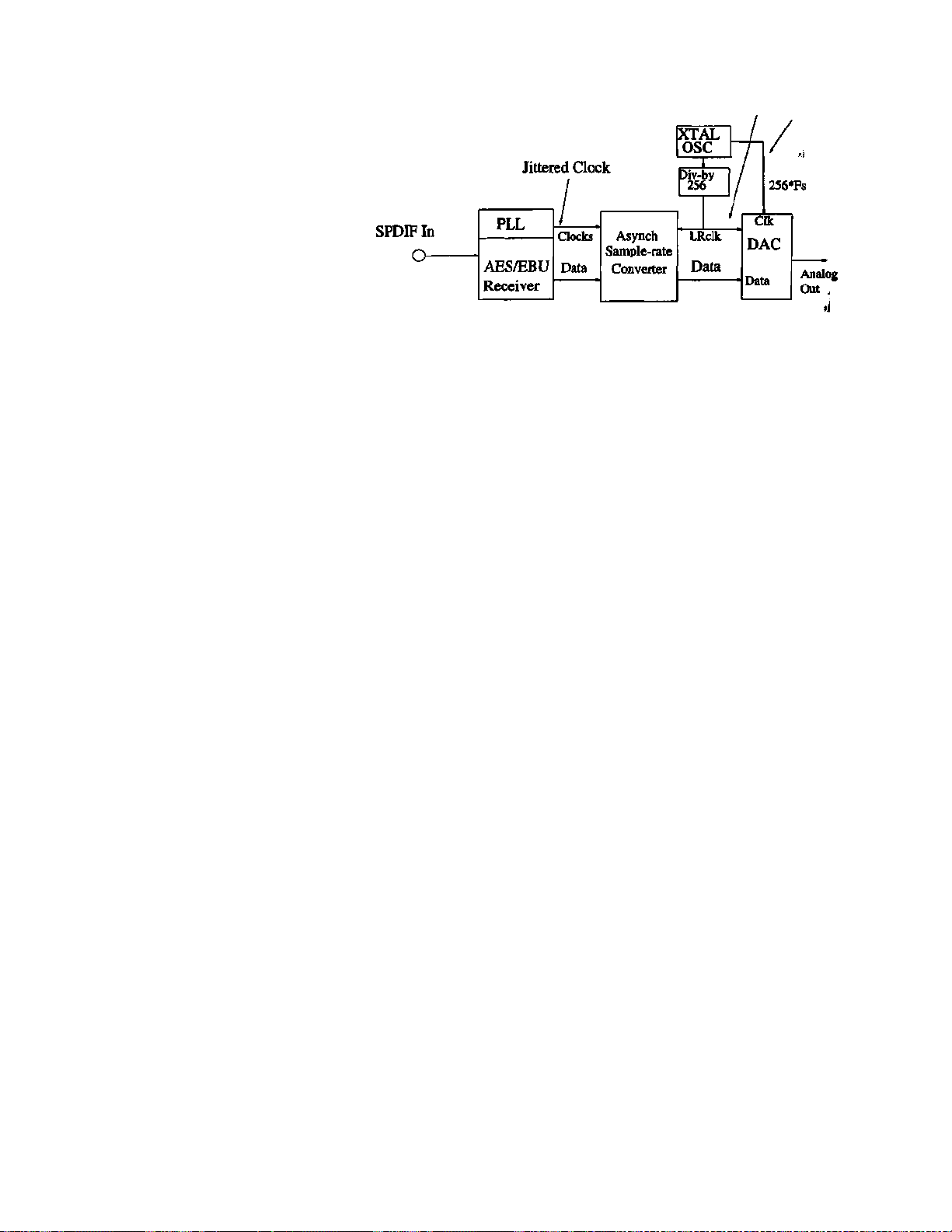

0 Introduction

Although clock jitter has received a great deal of recent attention

in the popular audio press, its effect

on signal fidelity is poorly understood by most journalists, and many

inaccurate statements have appeared

in print. The purpose of this article is

to introduce the fundamentals of

clock jitter and to demonstrate how

it actually affects final signal quality

for various types of D/A converters.

We also will cover an exciting

new development in sample-rate conversion and show how it will influence

the next generation of digital audio

equipment.

It has become popular practice to

measure clock jitter in commercial

outboard D/A converters using an

FM demodulator attached to the

clock pin. The output of the demodu-

lator is fed to a spectrum analyzer,

so discrete components present in the

jitter waveform may be analyzed.

Unfortunately, the amount of degra-

dation a particular jitter spectrum will

cause in the output signal depends on

the type of D/A converter used. To

interpret the results of such a mea-

surement, one has to take into ac-

count at least the following significant variables:

(a) Converter type—conventional

resistive ladder, sigma-delta, or

MASH.

(b) Clock frequency applied to

the converter.

(c) Output filter type—switched-

capacitor, active RC, or a combination.

(d) Any digital dividers between

the measured clock pin and the internal D/A clock rate.

(e) Interpolation ratio.

(f) The frequency and amplitude

of the input signal.

(g) Jitter introduced internally to

the D/A converter (not measurable

except by its effect on the signal itself).

These variables have more than

a minor effect on the jitter sensitivity.

With the worst combination, phase

jitter may have to be lower than 20

ps rms to obtain signals of 16-bit

quality, as opposed to more than 1

ns for the best case. Clearly, the relationship between clock jitter and the

analog output is complex enough that

one should understand the fundamen-

tals before making any judgments

based on jitter about the quality of a

particular piece of equipment.

Another complicating factor will

soon be introduced commercially: a

new chip from Analog Devices

called an "asynchronous sample-rate

converter," rapidly making its way

into outboard D/A processors. This

chip acts as a universal digital buffer

between an input at one sample rate

and an output at any other sample

rate. As a byproduct of the algorithm

employed in the chip, jitter on either

the input or output sample clocks is

largely eliminated. While most engineers understand how a conventional

analog PLL may be used to remove

clock jitter, it is not obvious how an

all-digital sample-rate converter can

accomplish the same task. Later in

this article we will discuss how use

of this chip affects jitter in D/A converters.

1 Review of Clock Jitter

Clock jitter may be defined as

the time displacement of a clock sig-

nal relative to an ideal clock signal

with no jitter. Note that all the information about jitter is contained in the

edges of the clock signal, and it is

common to specify jitter in the time

domain as either the p-p or rms deviation of any edge from its ideal position over many thousands of clock

cycles. Most digital systems will

change state only on one edge of the

clock signal (the rising or falling

edge), in which case the jitter is measured on the clock edge to which the

system responds.

In practical systems, the com-

mon types of clock jitter are:

(a) Random variations in the arrival of clock edges relative to their

ideal positions. For advanced readers, this type of jitter is referred to as

white phase jitter, as it may be produced by feeding a random-noise

(i.e., white-noise) signal into a phasecontrolled oscillator.

(b) Random variations of the

width of a clock pulse. This type of

jitter differs from (a) in that each

edge is referenced to the previous

edge rather than to a hypothetical

ideal clock signal. Again, for E.E.

types, this jitter is referred to as

white FM jitter, as it can be produced

by feeding a white-noise signal into a

11

pdf 12

Page 13

frequency-controlled clock generator.

(c) Correlated variations in the

clock edge events relative to an ideal

clock. By correlated we mean that

the instantaneous time displacement

measured on each clock edge is not

an independent event but is in some

way related to previous clock edge

times. For the technical reader: this

causes a jitter "spectrum" which is

nonwhite and may have spectral

peaks at particular frequencies. We

will refer to this type of jitter as correlated jitter. If the variation in clock

frequency is "slow" compared with

audio frequencies, we will call this

low-frequency correlated jitter; if

these variations are fast compared

with the audio spectrum, we will call

this high-frequency correlated jitter.

2 The Pitfalls of Time-Domain

Measurements

It is common to estimate clock

jitter by using an oscilloscope with a

very accurate time base. This practice is dangerous, as the results obtained depend on the type of jitter as

well as on the measurement technique. It also is often the case that the

oscilloscope used will have more jitter in its time base than is present in

the clock itself. Advanced instruments are available to make accurate

measurements of jitter but are not

used enough.

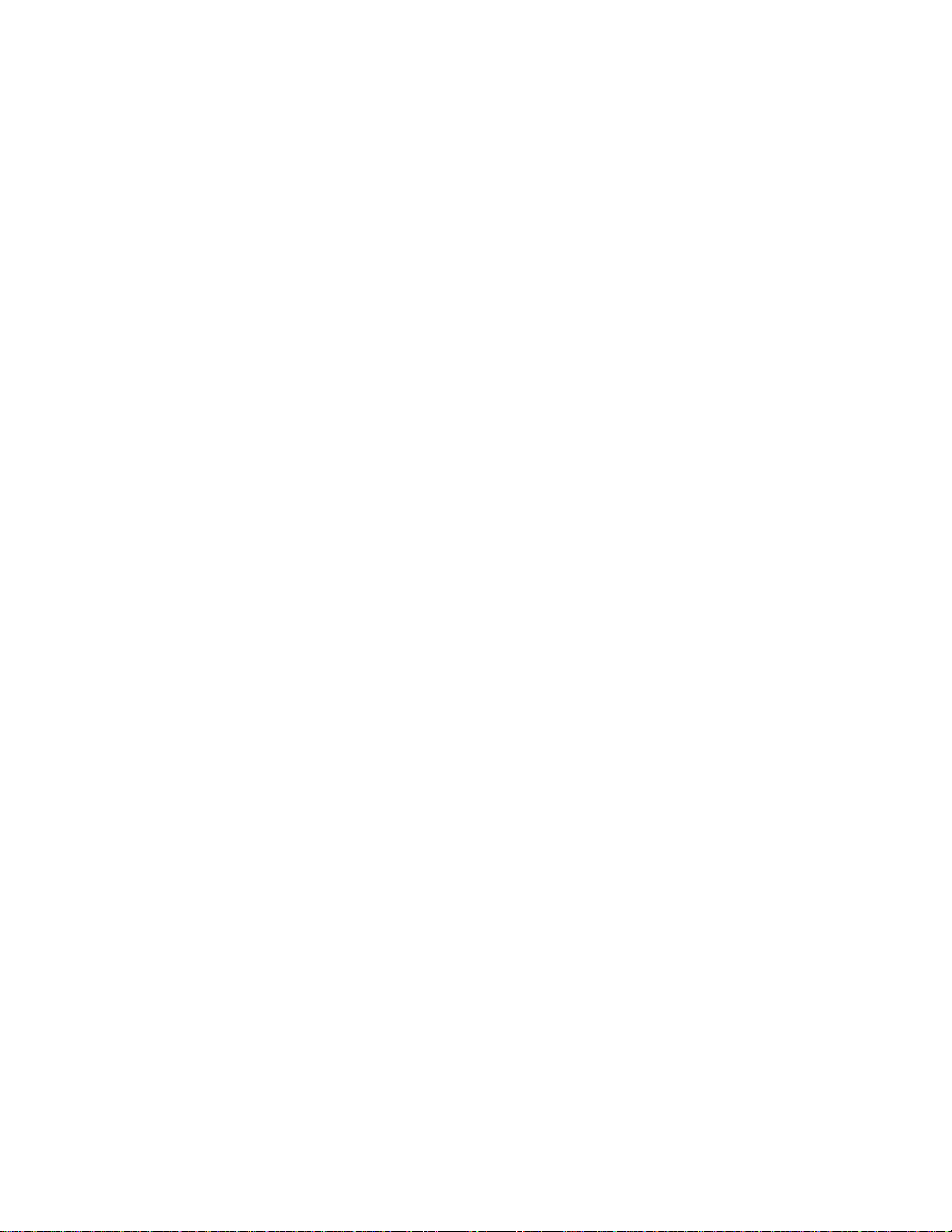

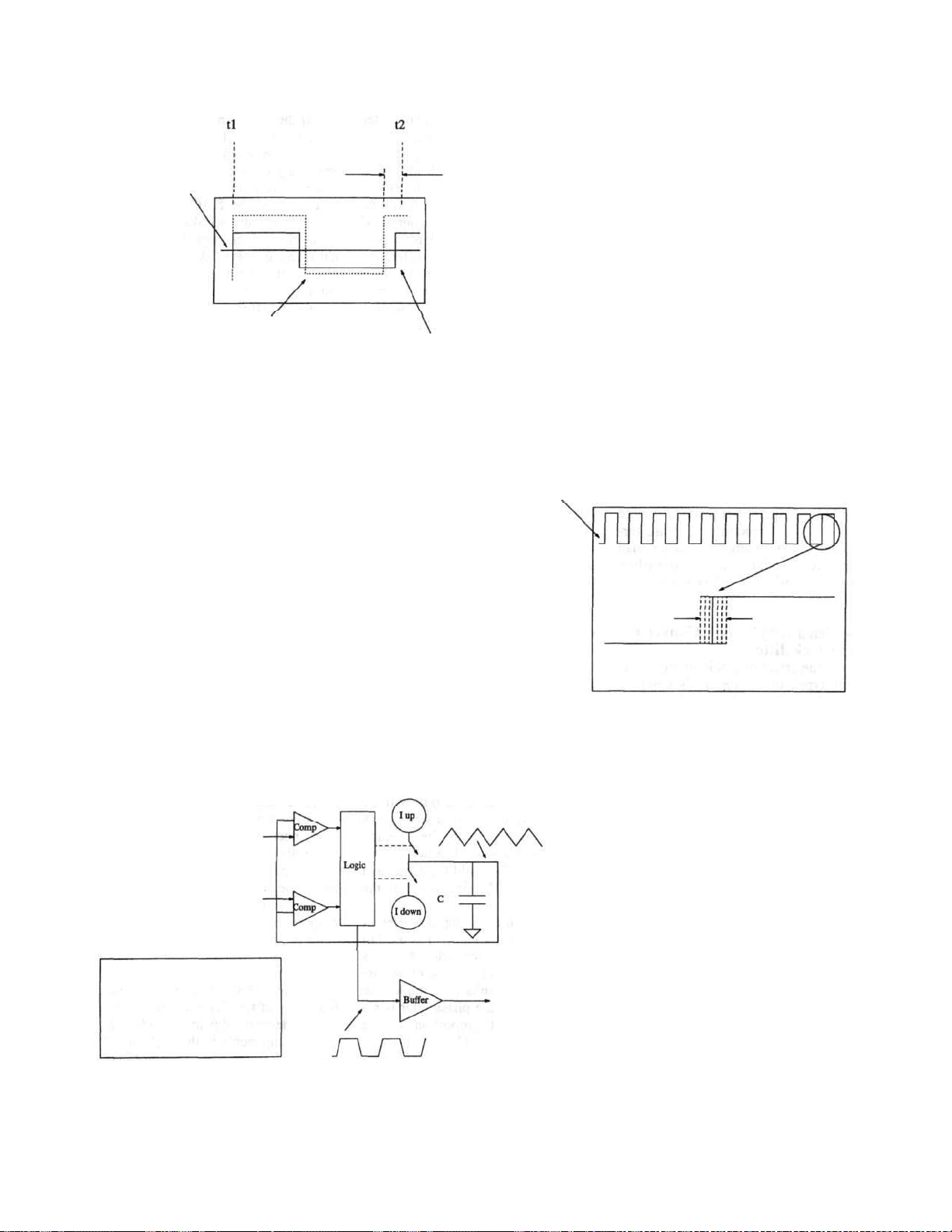

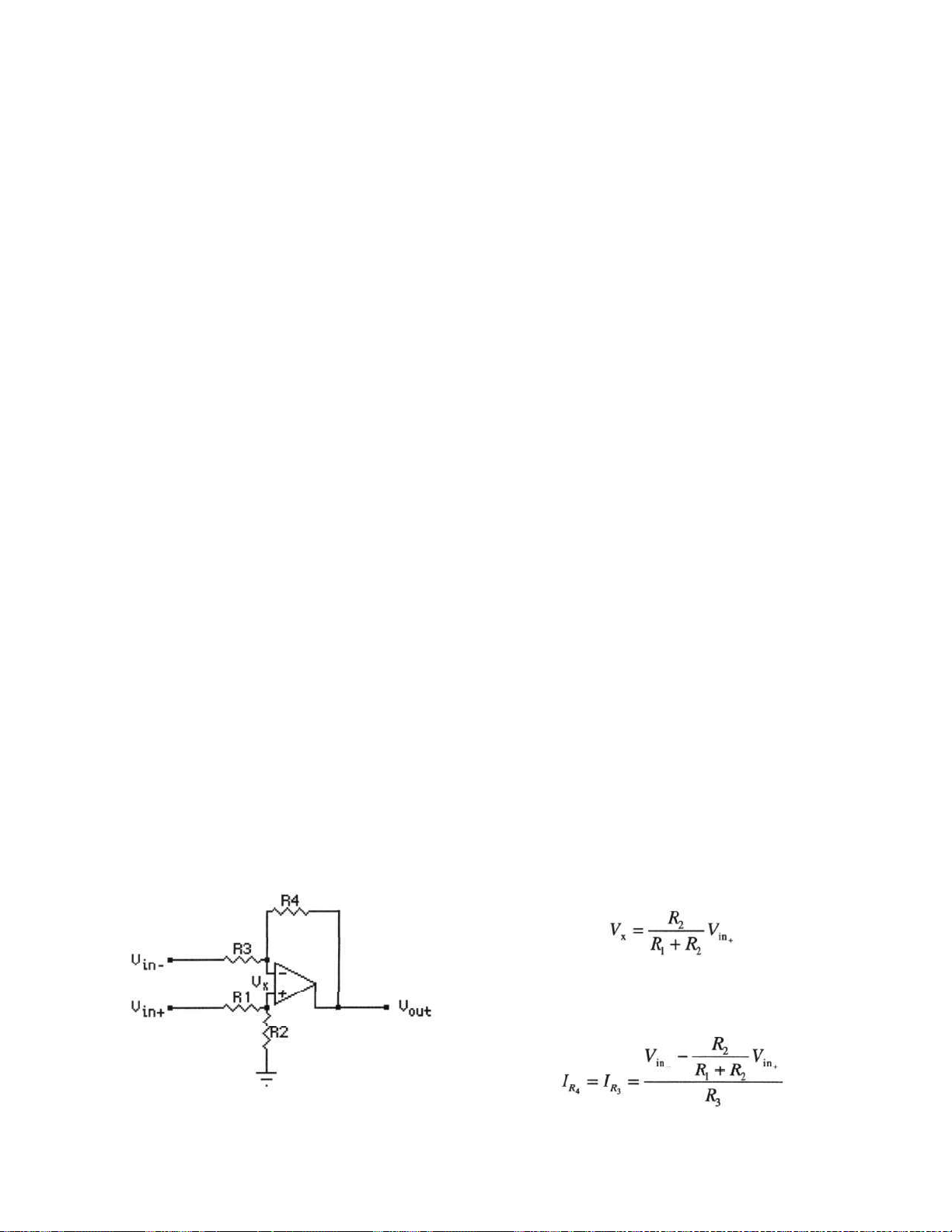

Figure 1 shows one measurement

technique where an oscilloscope is set

to trigger on a clock edge and the time

base is set so that only the next edge

is visible on the scope. The variations

in the arrival time of the later edge

can be used as a measure of p-p jitter.

More sophisticated oscilloscopes can

plot a histogram of zero-crossings,

allowing a more accurate estimate of

the rms jitter without resorting to

"eyeball" measurements.

Since we are triggering on one

edge and measuring the arrival time

of the next, we are assuming that the

first edge (the one we are triggering

on) is in its "ideal" time position.

This technique is fine if we are

measuring white phase jitter as

defined above, where the errors in the

clock edge positions do not accumu-

late over time relative to an ideal

clock signal. But suppose that the frequency of the clock signal is slowly

wandering by a small amount (low-

12

frequency correlated jitter). This

slow wandering of the frequency

causes large displacements of the

clock edges relative to a stable clock,

but the edge-to-edge measurement

technique will not reveal this effect,

as each measurement is made in reference to the last clock edge only.

Another common technique is to

trigger an oscilloscope on a clock

edge and, by using the delayed trigger feature, examine the edges that

occur at some later time (for example, 10 clock edges later). See Figure

2. If we assume that, again, we have

a clock signal with slowly varying

frequency, we can see that this measurement technique will start to reveal this low-frequency jitter component as long as the trigger delay is

long enough for the frequency of the

clock signal to have changed substantially between the moment when the

trigger event occurred and when the

delayed edge is examined some time

later. But one danger of this tech-

nique is that it is possible the jitter

frequency is correlated in such a way

that at particular trigger-delay values

the delayed edge of the clock has returned to its correct position. This

technique therefore has periodic occurrences of "blind spots" relative to

the modulating frequency of the

clock generator and is not to be trusted if the clock signal contains highly

correlated jitter components.

The predominant type of noise

mechanism present may be estimated

by examining a succession of delayed edges and observing how the

jitter behaves as a function of delay

time. White FM jitter as defined

above will display a square-root relationship between delay time and observed edge jitter, as each clock period is an independent jitter event, and

therefore many such events add in

rms fashion. Jitter which contains

low-frequency modulation of its frequency will show a linear relationship

between delay time and observed jitter. White phase jitter shows no increase in observed jitter with trigger

delay time, as the errors do not accumulate over time. Correlated jitter

shows a more complicated relationship between edge-to-delayed-edge

delay times and observed jitter.

The discussion above indicates

that time-domain jitter measurements

are dangerous, although useful infor-

mation may still be obtained if one is

careful. It is preferable nonetheless to

use a high-quality FM or PM detector in conjunction with a spectrum

analyzer, provided one knows how to

interpret the results [Robbins 1982].

3 Sources of Jitter in Practical

Clock Circuits

Consider the clock circuit of Figure 3, which is a typical RC oscillator, such as might be found in the

voltage-controlled oscillator used in

a PLL. The VCO works in the following fashion. Assume at the outset

that the capacitor is charged to V

ref

Low and the logic has turned on the

switch which connects the current

source Iup to the capacitor. The volt-

age on the capacitor now rises with a

slope proportional to Iup. When the

voltage on the capacitor reaches V

ref

Hi, the upper comparator changes

state and the current I

down

is now

connected to the capacitor, causing

the capacitor to begin charging down

at a rate proportional to the current.

When the voltage reaches V

ref

Low,

the lower comparator changes state,

and the whole operation repeats itself, forming an oscillator.

From the previous explanation,

we can see that the current I determines the frequency of oscillation of

the oscillator.

There are at least three possible

sources of jitter in this circuit. Here

we are analyzing only the one

caused by thermal noise. Practical effects such as correlated frequency

components on the power supply or

those picked up because of magnetic

coupling will of course be added.

The first source of error is noise

in the current that charges and discharges the timing capacitor C1.

Since this current directly controls

the frequency of the oscillator, noise

on this current source translates directly into white FM clock jitter.

The second source of error is

thermal noise at each comparator input, which causes the comparator to

switch at the wrong time. Since each

pulse is referenced to the end of the

last pulse, any variation in clock arrival time will be "remembered" by

all subsequent pulses, and therefore

this mechanism must again produce

white FM jitter. This can be verified

THE AUDIO CRITIC

pdf 13

Page 14

Jitter Sources:

1) Current source noise (makes FM jitter).

2) Comparator noise (makes FM jitter).

3) Buffer intercept noise (makes phase jitter).

Output

Figure 3: Jitter sources in a typical RC oscillator.

Vref HI

Vref LOW

Figure 2: Edge-to-delayed-edge jitter measurement.

Scope Display

Delayed sweep

p-p jitter

Scope triggers hers.

Scope Display

Jitter

Scope triggers here.

Ideal non-jittered

output

Jittered Output

Figure 1: Edge-to-edge jitter measurement.

ISSUE NO. 21 • SPRING 1994 13

pdf 14

Page 15

by imagining that the comparator

noise is dc (equivalent to an offset).

It is easily seen that this causes a

shift in frequency.

The third source of error results

from thermal noise on logic gates

that are fed with finite rise-time clock

signals. Such noise on the inputs of

these gates is translated into jitter

from the delta-t to delta-v conversion

that occurs due to the finite rise time

of the input signal. Since this mechanism has no "memory," it results in

white phase jitter.

There are several other types of

oscillators that offer improved jitter

performance. Crystal-controlled oscillators are best. Voltage-controlled

crystal oscillators are available, and

these are sometimes used to recover

the clock from the incoming serial

data stream (from the output of a CD

player, for example). While they

have low jitter, they suffer from a

limited frequency-adjustment range

(about 0.1% maximum). Varactortuned LC oscillators are better than

the RC oscillator described earlier,

but not nearly as good as a crystal oscillator.

4 Sensitivity of D/A Converters

to Clock Jitter

The effect of clock jitter on vari-

ous types of converters is complex

and depends on many factors. Converter topologies may vary in their

sensitivity to jitter by several orders

of magnitude, depending on the nature of the jitter.

For the purposes of analyzing jitter sensitivity, D/A converter fall into

three classes.

(a) Conventional, resistive ladder converters with or without interpolation filters.

(b) Sigma-delta converters with

continuous-time output filters.

(c) Sigma-delta converters with

switched-capacitor output filters.

4(a) Conventional, resistive ladder

D/A converters:

The effect of jitter on the output

of a D/A converter can be analyzed

by subtracting the output of a D/A

converter that uses a jittered clock

from the output a theoretically perfect converter that uses a nonjittered

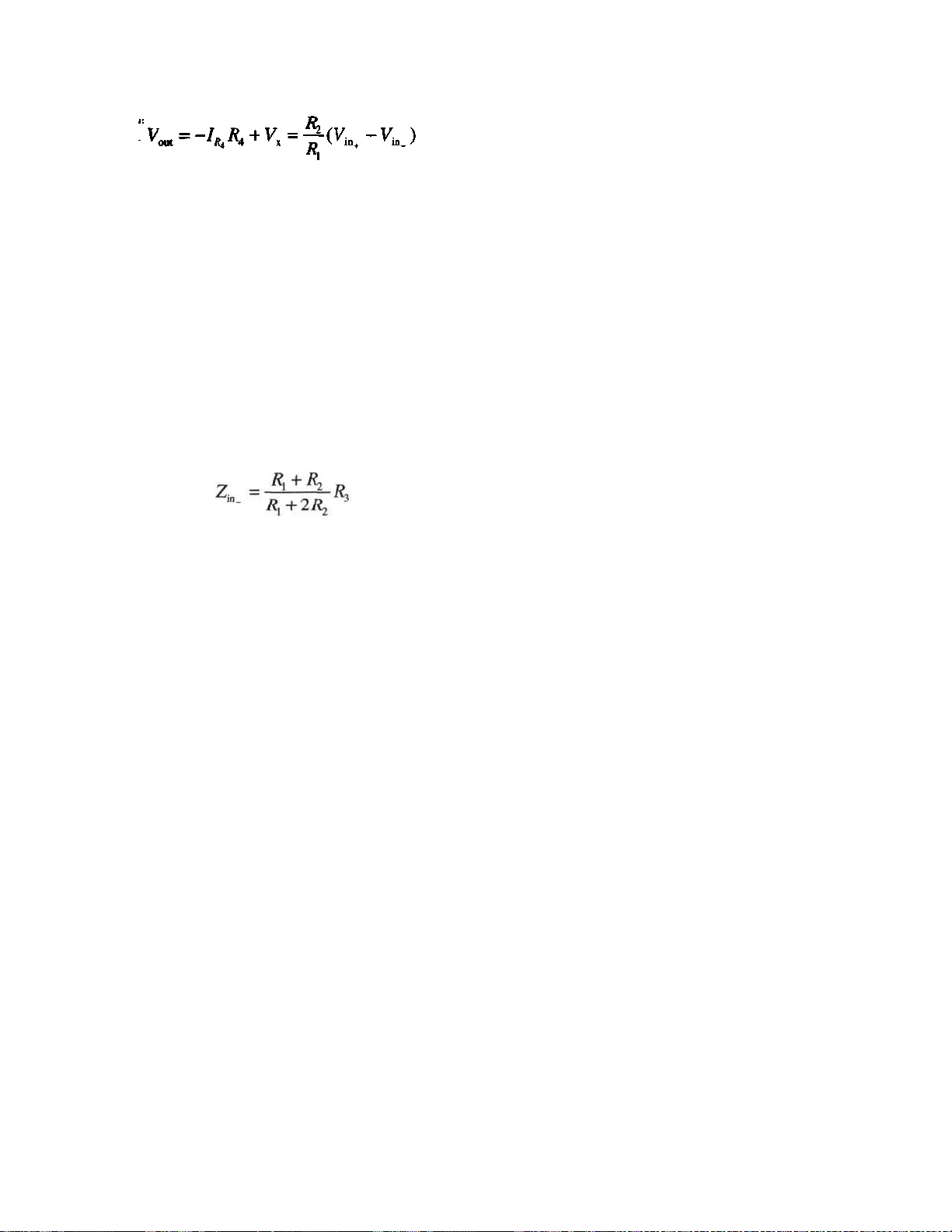

clock, and then looking at this difference in the time domain. Figure 4

14

shows this analysis technique for the

case of a conventional D/A converter

with two different input frequencies

and no interpolation filter.

Figure 4a shows a 1 kHz sine

wave sampled at 50 kHz. The difference between jittered and nonjittered

D/A outputs is seen to be a series of

narrow spikes whose width is proportional to the instantaneous difference

between the arrival time of the ideal

clock and that of the actual jittered

clock, and whose height is proportional to the change in signal amplitude from the previous to the current

sample. Here we show the case for

white phase jitter, which does not ac-

cumulate over time. Note the modulation of the error spikes by the signal slope, which causes the error to

become very small at the signal

peaks.

We are now in a position to analyze the added noise and how it relates to the signal. The spectrum will

be white, as there is no statistical relationship between one error pulse

and the next. The rms amplitude of

the noise spectrum is related to the

average slope of the DAC output signal, as large step sizes between adjacent samples cause large error pulses

in the error signal. This fact can be

seen clearly in Figure 4b, where a

higher-frequency signal (6 kHz) has

been applied to the D/A converter,

resulting in larger step sizes between

adjacent samples and hence larger er-

ror pulses.

We can summarize by saying

that for white phase modulation of

the clock, the D/A output will be

corrupted by white noise whose rms

amplitude varies with the average

slope of the signal. The worst-case

signal for audio would therefore be a

full-scale 20 kHz sine wave at the

D/A output.

The situation is slightly different

when an interpolation filter is used in

front of the D/A converter. Analysis

of that is beyond the scope of this article, but the results are simple: the

sensitivity to white phase jitter is reduced in direct proportion to the

oversampling ratio. This means that a

D/A converter using a 16x interpolation chip will be four times less sensitive to jitter than one using a 4x

oversampling filter (assuming that

the absolute jitter in ps is the same

for both clocks).

If the jitter is not white phase jitter but rather a relatively slow variation of the clock frequency (lowfrequency correlated jitter), then the

situation is quite different. Assume

that we feed the DAC with a sine

wave. Spectrally speaking, a slowly

wandering clock signal will cause

narrowband noise "skirts" to appear

around the frequency of the sine

wave signal. Oversampling no longer

has much effect on the output spectrum, as the errors introduced by the

clock modulation are all "inband"

(below 20 kHz).

Many types of jitter fall in be-

tween the pure white phase jitter and

slow frequency-variation type of jitter described above. In that case,

oversampling may improve the jitter

sensitivity to a certain degree, but not

as much as in the case of truly random white phase jitter. Jitter in

which the time base is sinusoidally

modulated will potentially produce

discrete frequency components spaced

around spectral sticks in the DAC

output signal.

For resistive ladder converters, it

is obvious that with no input signal

(or dc), jitter cannot have any effect

on the output. The output is not

changing, so it doesn't matter exactly

when it doesn't change! While this

observation may seem trivial, the

same statement cannot be made for

other types of converters, as we shall

see presently.

In summary, regarding resistive

ladder D/A converters, we can state

the following:

• For white phase clock jitter, the

jitter spectrum on the DAC output is

white and proportional to the average of the absolute value of the signal slope. Oversampling filters decrease the jitter sensitivity in direct

proportion to the oversampling ratio.

With no input to the DAC, jitter has

no effect and does not raise the noise

floor.

• For "slow" variations in the

frequency of the clock signal, narrow

noise sidebands appear around sinusoidal components in the D/A output

spectrum, again with an amplitude

proportional to the frequency and

amplitude of the sinusoid. Oversampling filters do not decrease the jitter

sensitivity in this case.

THE AUDIO CRITIC

pdf 15

Page 16

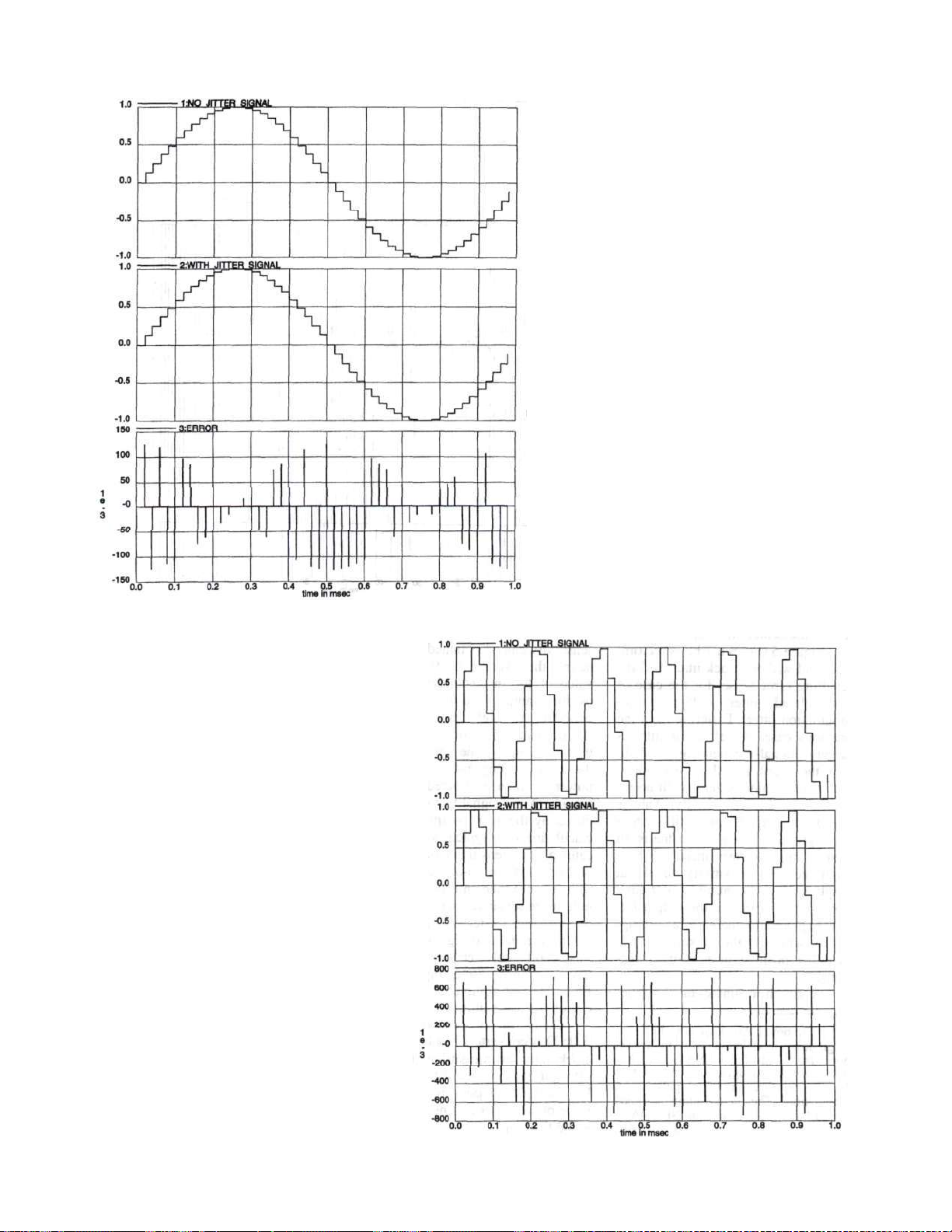

Figure 4

Figure 4a:

Time-domain jitter error

for a 1 kHz signal.

Figure 4b:

Time-domain jitter error

for a 6 kHz signal.

ISSUE NO. 21 • SPRING 1994 15

pdf 16

Page 17

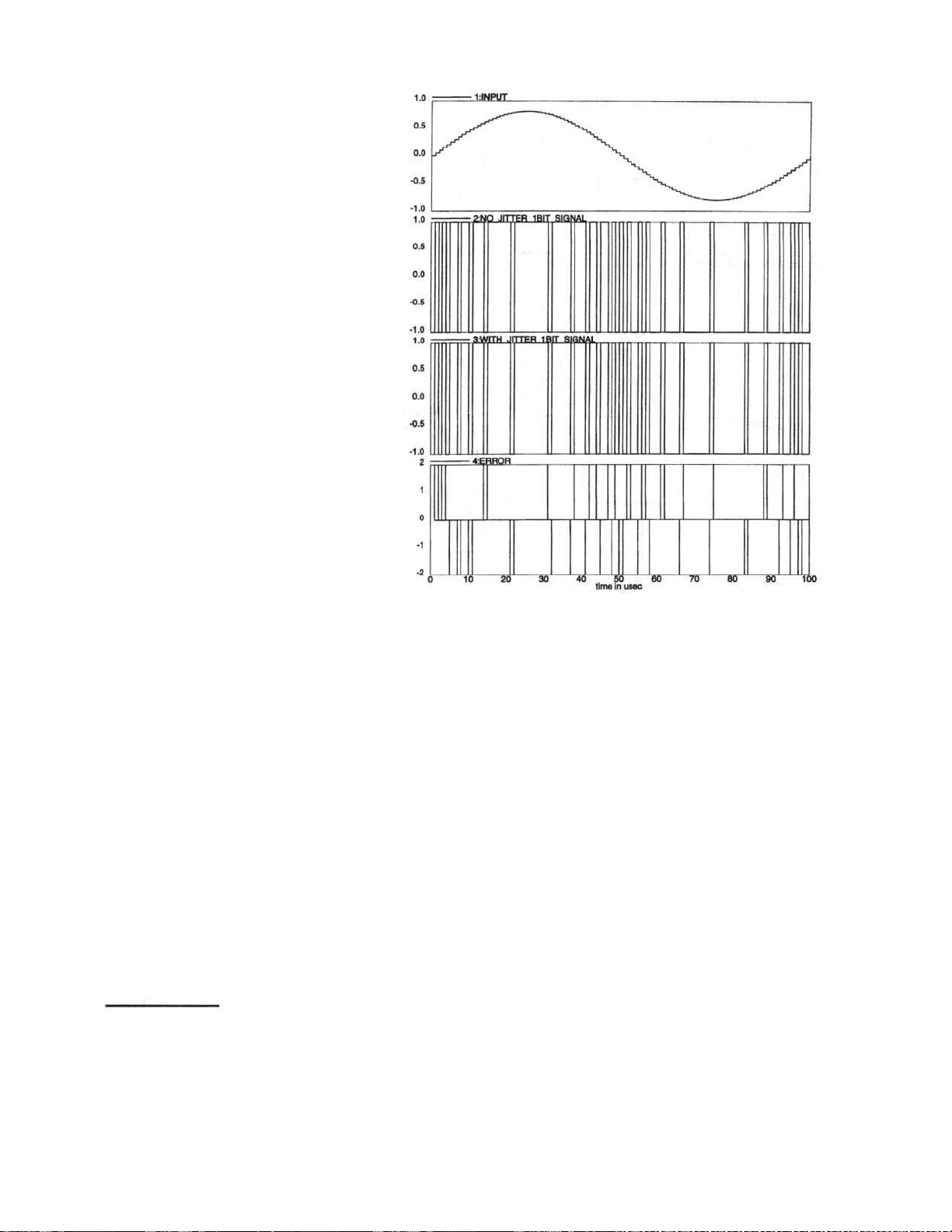

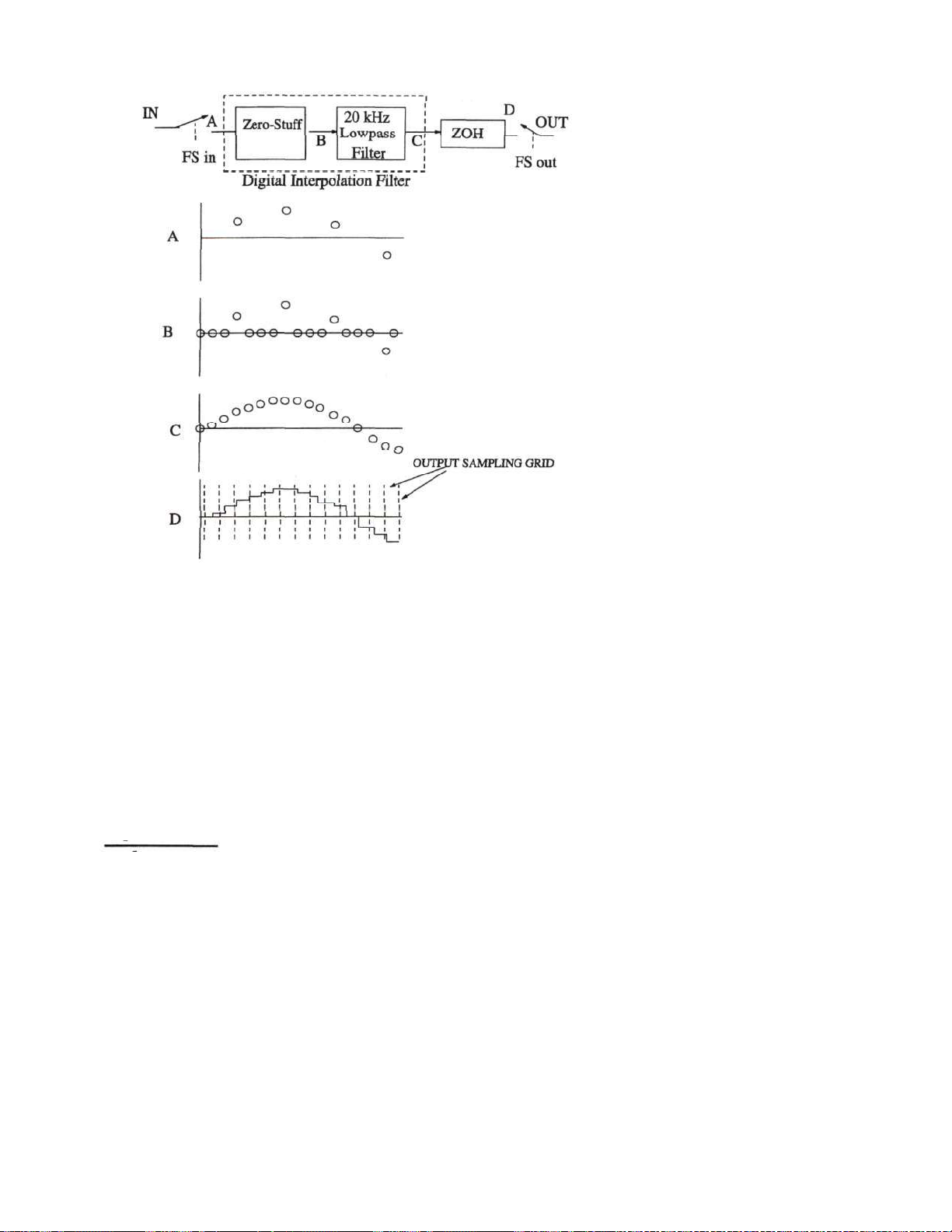

Figure 5: Time-domain jitter waveforms for 1-bit D/A converters.

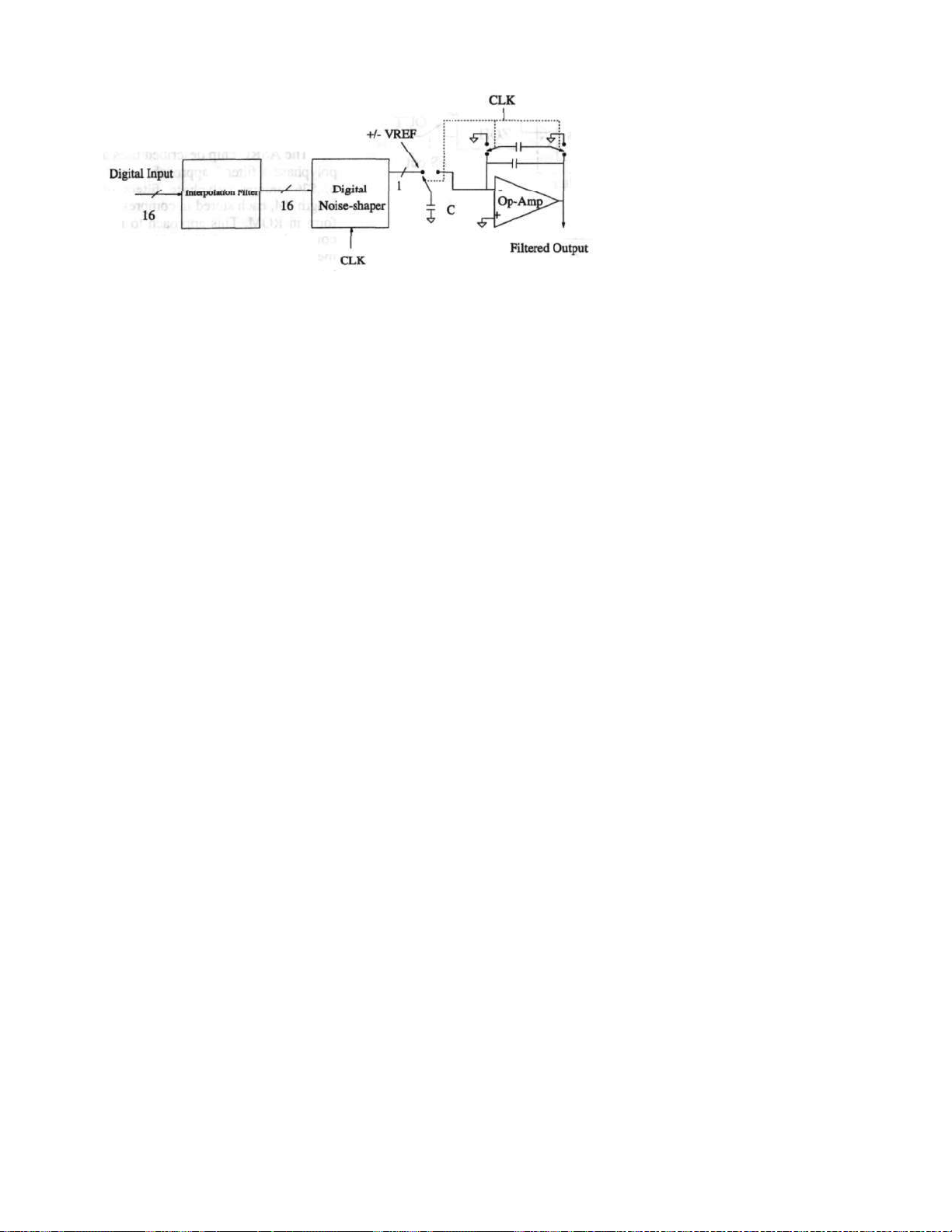

4(b) One-Bit Noise-Shaping D/A

Converters with No Switched-Cap

Output Filter

This type of converter has become very popular in recent years,

both because of its inherent linearity

and because it can be implemented in

an all-digital CMOS process.

One-bit noise-shaping converters

can be further divided into two classes. The first is a single-loop modulator with 1-bit quantization, and this

1-bit signal is fed directly to a 1-bit

output stage at the modulator clock

rate. The second class of converters,

so-called MASH converters, involve

multiple loops with feedforward

noise cancellation. They internally

produce a multiple-level digital signal, which is converted to a 1-bit signal through digital pulse-width modulation. To achieve the desired time

resolution for the digital pulse-width

modulator, a clock signal with a very

high frequency is typically used.

1

In the previous section, we saw

that the sensitivity to clock jitter was

proportional to the changes in the

DAC output from one sample to the

next. For 1-bit converters, this

"change" is always full-scale, regardless of the actual input signal!

Figure 5 shows a 1-bit waveform

with and without clock jitter, and the

resulting error pulse, for the case of