Page 1

FUNDAMENTALS OF

MUSIC TECHNOLOGY

Volume One:

The ARP 2600

S•Y•N•T•H•E•S•I•Z•E•R

S E C O N D E D I T I O N

A Pedagogic Work in Elementary Synthesis

With Sampling and Example CD

by

S A M U E L E C O F F

Page 2

FUNDAMENTALS OF

MUSIC TECHNOLOGY

Volume One:

The ARP 2600

S•Y•N•T•H•E•S•I•Z•E•R

S E C O N D E D I T I O N

A Pedagogic Work in Elementary Synthesis

With Sampling and Example CD

by

S A M U E L E C O F F

Page 3

Secret Society Pr oductions

Fundamentals of Music Technology Volume One: The ARP 2600 Synthesizer

Copyright ©& 2000 by Samuel Wells Ecoff. All Rights Reserved.

P

Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of

this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means,

or stored in a data base or retrieval system, without the prior written permission

of the author . If you would like to use excerpts from this book as part of a web

page, call me; we’ll talk. :-) The author hereby grants permission to the reader

to make copies of Appendix T wo (patch sheets for the 2600 and ARP sequencer)

as needed, as long as they are used for personal purposes, and not for profit.

T ypeface: Times

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

CD LICENSING AGREEMENT

Permission is hereby granted to create samples from the audio CD included with this book. However, by

breaking the seal on the CD casing, the user agrees to the following terms: The sounds and samples on

this disc are licensed, not sold to you. You may use the sounds and samples found on this disc in a

commercial or non-commercial recording without paying any additional license fees. However, you must

strictly adhere to the following crediting guidelines on any music recording that uses material from the

enclosed CD:

In the written materials accompanying your music release, you must include the following courtesy

credits using this wording strictly:

ARP 2600 samples courtesy of Sam Ecoff of Secret Society Productions

Use of these sounds is limited to use musical context, and these sounds must not be left exposed where

they could be easily sampled by a third party. This license of free use is granted exclusively to the original

purchaser of this disc and book, and is non-transferrable.

Any redistribution of this material in any form or by any means is strictly prohibited.

®

1 1.70

2 2.03

3 1.73

4 3.79

6 1.67

8 2.82

10 1.32

13 1.33

15 1.50

17 1.38

19 1.22

21 1.12

23 2.11

25 1.31

27 1.23

29 1.32

31 1.22

33 1.19

35 1.10

36 1.10

37 1.04

38 1.06

39 1.08

40 1.01

41 1.3

42 1.1

ii

Page 4

This book is dedicated to all of the people that love

this wonderful instrument as much as I do; to the

people who know that the patch isn’t complete until

every available patch cord has been used.

iii

Page 5

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table of Contents...............................................................................................................................iv

Listing of Tracks on CD ....................................................................................................................vi

How the CD was Recorded ...............................................................................................................x

Prefaces..............................................................................................................................................xi

Thank You..........................................................................................................................................xiii

About the Format of this Book.......................................................................................................... xiv

UNIT ONE: INTRODUCTION AND OSCILLATORS

Section One: General Controls.......................................................................................................... 001

Experiments........................................................................................................................... 009

Review Questions ................................................................................................................. 010

Section T wo: VCO-1..........................................................................................................................011

Experiments........................................................................................................................... 016

Review Questions ................................................................................................................. 017

Section Three: VCO-2 ...................................................................................................................... 018

Experiments........................................................................................................................... 028

Review Questions.................................................................................................................. 029

Section Four: VCO-3.........................................................................................................................030

Experiments........................................................................................................................... 034

Review Questions.................................................................................................................. 035

UNIT TWO: MODIFYING THE SIGNAL

Section Five: Noise Generator ...........................................................................................................036

Experiments........................................................................................................................... 040

Review Questions.................................................................................................................. 041

Section Six: The VCF .......................................................................................................................042

Experiments........................................................................................................................... 052

Review Questions.................................................................................................................. 054

Section Seven: ADSR & AR Generators...........................................................................................055

Experiments........................................................................................................................... 060

Review Questions.................................................................................................................. 062

Section Eight: The VCA....................................................................................................................063

Experiments........................................................................................................................... 068

Review Questions.................................................................................................................. 069

iv

Page 6

TABLE OF CONTENTS

UNIT THREE: FINISHING TOUCHES

Section Nine: The Mixer Section and Reverberator..........................................................................070

Experiments........................................................................................................................... 073

Review Questions.................................................................................................................. 074

Section Ten: The Internal Clock, Electronic Switch, and S/H Circuits.............................................075

Experiments........................................................................................................................... 080

Review Questions.................................................................................................................. 081

Section Eleven: The Ring Modulator, Preamp and Envelope Follower ...........................................082

Experiments........................................................................................................................... 088

Review Questions.................................................................................................................. 090

UNIT FOUR: ADDITIONAL MODULES

Section T welve: The Voltage Processors........................................................................................... 091

Experiments........................................................................................................................... 095

Review Questions.................................................................................................................. 097

Section Thirteen: Keyboard Controls................................................................................................ 098

Experiments........................................................................................................................... 106

Review Questions.................................................................................................................. 108

Section Fourteen: Patch Analysis and Diagramming........................................................................ 109

Experiments........................................................................................................................... 118

Review Questions.................................................................................................................. 118

Section Fifteen: Further experiments with the ARP Sequencer.........................................................119

Experiments........................................................................................................................... 123

Review Questions.................................................................................................................. 124

Glossary..............................................................................................................................................125

Index.................................................................................................................................................. 136

Bibliography.......................................................................................................................................138

About the Author................................................................................................................................139

APPENDICES

Appendix One: Additional Resources for students of Electronic Music...........................................140

Appendix Two: ARP 2600 + ARP sequencer patch sheets................................................................143

v

Page 7

CD TRACK LISTING

Track Page Note(s) Description

SECTION 2

1 12 C1-C5 VCO-1 Saw Wave, VCO-1 Square Wave

2 12 C3 VCO-1 is tuned to VCO-2 (Saw Wave both)

3 15 LF VCO-1 in LF mode is gradually increased until it is audible. Saw

then square wave

SECTION 3

4 22 -- VCO-1 FM’d by a saw wave from VCO-2 in LF mode.

5 24, 28 -- Sidebands

6 25, 28 C1-C5 PWM patch where VCO-1 causes a pulse width sweep.

7 18, 28 C1-C5 Saw, Pulse, Sine, Triangle waves from VCO-2.

8 28 C3 Pulse width is manually swept.

9 28 -- FM patch, all parameters swept one by one.

10 28, 106 C1-C5 FM patch, VCO-2 produces interval leaps with square wave.

11 27, 28 C1-C5 Phat Tuning VCO-1 and 2 with saw waves, the square waves.

SECTION 4

12 31, 34 C1-C5 Double FM modulation. VCO-1 and VCO-2 modulate VCO-3

13 32, 34 -- Cross FM modulation patch. VCO-2 and VCO-3 modulate each

other in the audio range. Second time deeper modulation than

1st.

14 32, 34 -- Series modulation. VCO-1 --> VCO-2 --> VCO-3.

15 34 C3-C4 All three VCOs tuned in intervals. Major and minor chords on

each white key.

SECTION 5

16 37 C1-C5 Noise Generator FMs VCO-3. Saw Wave timbre. First with little

FM, second time with a lot of FM

17 39 C1-C5 Noise Generator PWMs VCO-2. First with small modulation

depth, second time with greater modulation depth.

18 40 -- Noise Generator’s raw output, noise frequency slider is then swept.

SECTION 6

19 45, 52 C1-C5 Filter sweeps close on a saw wave from VCO-2

20 46, 52 C1-C5 Resonant filter sweeps close on saw waves from VCO-1 and 2

21 47 C1-C3 The VCF is made to self-oscillate. Notice how tuning drifts.

22 48 C1-C5 All White keys played key tracking on filter disabled. VCO-1, 2,

and 3 in phat tuning.

vi

Page 8

CD TRACK LISTING

Track Page Note(s) Description

23 49 C1-C5 Highpass filter sweep (JP-8000) followed by resonant highpass

filter sweep (JP-8000)

24 49 --- This track has intentionally been left blank due to an error in

printing in the book.

25 52 C3 Filter’s Fc is modulated by VCO-2’s sine output in the audio

range. Sidebands result.

26 52 C2. C3, C4 Keyboard CV no longer controls VCO, but still controls Fc.

27 52 C1-C5 VCO-1 saw wave (LF) modulates Filter’s Fc while harmonics of

a saw wave from VCO-2 are accentuated by heavy resonance.

Set mod rate as low as possible.

SECTION 7

28 60 C1-C5 ADSR EG FMs VCO-1, 2 and 3 (mixed waves) Only attack stage

is used.

29 60 C1-C5 Same as track 28, but just decay.

30 60 C1-C5 Same as track 28, but just sustain. Sustain level is manually

changed during this experiment. (Release on gate increased)

31 60 C1-C5 Same as track 28, but just release + sustain. Mod depth increased.

32 60 --- Noise generator is put through filter, first w/o resonance, then

with. Percussion sounds are created.

33 60 C1-C5 All VCOs in phat tuning, various ADSR settings, with and with-

out resonance. VCF controlled by ADSR.

34 60 C1-C3 All VCOs in saw wave, then square, just decay set very short

yields a good bass sound. First without resonance, then with.

35 61 C1-C3 Same as 34, but with just sustain.

36 61 C1-C3 Same as 34, but with just release + a little sustain.

37 61 --- AR FMs all three VCOs while ADSR modulates filter Fc.

38 61 --- ADSR FMs all three VCOs while AR modulates filter Fc.

39 61 C1-C5 Pitch of all three VCOs bends up to proper pitch whenever a note

is played.

40 61 C1-C5 ADSR generator FMs all three VCOs in different amounts while

AR controls VCF gating.

41 61 C1-C5 ADSR generator PWMs VCO-2

SECTION 8

42 64, 68 C3 VCO-2’s saw is gated first by VCF, then by VCA.

43 65, 68 C1-C3 All VCO’s gated by VCA, controlled first with Exponential in-

put, then linear input

44 66, 68 C1-C5 VCO-2 in LF mode controls VCA gain to create tremolo. VCO-

1 and 3 produce square waves, gated by VCF

45 66 C3 VCO-2 in LF mode modulates VCA gain quickly and deeply

enough to produce sidebands.

vii

Page 9

CD TRACK LISTING

Track Page Note(s) Description

46 68 C1-C5 VCO-2 and 3 fed into VCF controlled by AR EG. VCF fed to

VCA controlled by ADSR generator. Then, same patch, but VCF

controlled by ADSR and VCA controlled by AR.

SECTION 9

47 73 C1-C5 VCO-1 is patched directly to the reverberator.

48 73 --- Noise generator, gated by VCF is sent to mixer. Mixer sends to

reverberator. Different amounts of reverb are demonstrated.

49 73 --- The springs in the reverb tank are intentionally jostled.

50 72, 73 --- Noise generator, gated by the VCF is reverberated too heavily,

and a watery sound results.

SECTION 10

51 77, 80 C1-C5 Auto panning patch created with electronic switch

52 78 C1-C5 One LFO (VCO-1 saw wave) alternately modulates VCO-2 & 3.

53 78, 80 C2-B3 Switching patch: Pulsing sound is created by switching between

patch and silence.

54 78, 80 C1-C5 Switch alternates between two oscillators tuned differently , then

between oscillators and noise generator. With filter sweep.

55 78, 80 C1-C5 Switch switches between two LFOs modulating one VCO. One

LFO is in the audio range,

56 79, 80 --- S/H unit samples white noise and modulates VCO-1 and 2.

57 79, 80 C1-C5 VCO-2 & 3 sent to filter. VCF’s Fc is modulated by the S/H unit

which is sampling a slow-moving saw wave from VCO-1 in LF

mode.

58 79 --- S/H FMs VCO-1 & 2. Saw wave from VCO-3 is sampled to pro-

duce running chromatic and whole tone scales.

59 79, 80 --- Complex feedback patch in which output of VCF is fed back into

S/H unit which in turn modulates Fc and FMs VCOs

SECTION 11

60 85 C2 Person speaks into microphone connected to preamp and enve-

lope follower . Envelope follower is then used to FM VCOs, modu-

lates the VCF’s Fc, and finally the gain on the VCA.

61 86, 89 --- Ring Modulator is used to create highly metallic sounds

62 86, 89 C1-C5 Ring modulator is used to bring out high frequencies in this patch.

63 86 C1-C5 Square wave from VCO-1 in LF mode creates pulsing effect.

64 86, 89 --- Sound with lots of harmonics starts in AUDIO position, then

moves to DC position. Pitch of VCO-2 is swept upwards.

65 87, 89 --- VCO-1’s frequency remains constant while VCO-2’s frequency

is swept upwards. Both are connected to the ring modulator.

66 88 --- A drum loop from a CD is put into the preamp, then filtered and

distorted.

viii

Page 10

CD TRACK LISTING

Track Page Note(s) Description

67 88 C3 A sine wave from VCO-2 is amplified until it is clipped and turned

into a square wave.

68 88 C1 The output of a CD player is preamped, then fed to the envelope

follower before going to the FM inputs on the VCOs, the VCF,

and finally the VCA.

SECTION 12

69 92, 95 C scale VCO-1 reacts normally while the keyboard CV going to VCO-2

is inverted. Ascending C scale, then short melodic passage.

70 92, 95 C1-C5 Inverted envelope FM’s VCOs, modulates Fc, and finally modu-

lates VCA’s gain, each in turn.

71 92, 95 --- VCO-1’ s saw wave in the sub-audio range is inverted and used to

FM VCO-2.

72 94, 96 C1-C5 The keyboard CV is routed through the lag processor with a large

99, 106 lag time to produce portamento. Pitch slides from C1 to C5 and

back again.

73 96 C2 A lagged square wave from VCO-1 in LF mode FMs VCO-2.

SECTION 13

74 101 C1 + C scale Duophonic patch in which both voices share the VCF for gating.

75 101 C1 + C3 C3 is held while C1 is tapped. The lower voice switches from

one oscillator to two, illustrating how unmusical this can be.

76 106 C2 Vibrato is created using the keyboard’ s LFO. All parameters are

swept, including vibrato delay.

77 106 C3 Repeat switch causes constant retriggering.

78 107 C Scale Trigger switch on single. Scale is played legato up and down.

79 107 C scale Trigger switch on multiple. Scale is played legato up and down.

80 107 C Scale Trigger switch on multiple, portamento on, time minimum.

SECTION 14

81 112, 114 --- FM patch illustrated on page 112.

82 115, 11 --- FM patch illustrated on page 115.

83 117 --- A wild patch with lots of feedback, and modulation occurring in

the audio range. The S/H unit samples the VCA’s output.

SECTION 15

84 119 --- The frequency of VCO-1 is swept upwards first with the INI-

TIAL FREQUENCY control, then under control of the sequencer .

The voltage quantizer causes it to ascend in chromatic half steps.

85-93 Miscellaneous sequencer patches

ix

Page 11

HOW THE CD WAS RECORDED

The audio CD which accompanies this book was recorded by connecting the left and right outputs of

the ARP 2600’s mixer section to a Mackie LM-3204 mixer. The incoming sounds were compressed

slightly with a Behringer Composer compressor before being routed to a Digidesign 882 audio interface connected to a Pro Tools|24 system. The ARP 2600 was then recorded into Mark of the Unicorn’s

Digital Performer 2.61MT hard disk recording software running on a Macintosh G3. It was then edited

so that each example began and ended in exactly the right spots and was mastered with plugins from

TC Works and MOTU. Other than the aforementioned gentle compression, no effects were applied to

the incoming sounds from the 2600.

The 2600 was played part of the time from its own keyboard and part of the time from a Fatar SL-880

mother keyboard and Digital Performer through a Paia MIDI2CV8 converter. Many of the melodic

samples were progammed into Digital Performer to insure timing accuracy and consistency. While

purists may argue against the use of MIDI in controlling an ARP 2600, the author was left with no other

choice as a capacitor in the keyboard’s control panel went bad only a week before the final recording

session for the CD, and the repair unfortunately could not be completed in time for the final recording

session. (Special thanks to T im Smith of The Audio Clinic who restored the keyboard control panel to

working condition).

When melodic patches were recorded (i.e. pitched sounds) an effort was made to make them available

at many different pitches for reader who may wish to sample them. These pitches can then be used to

create a multisample which yields the highest amount of accuracy in sample playback.

The samples associated with Section 15, were created using the ARP sequencer rather than Digital

Performer running through the Paia converter . As a result, some drift is noticable in tuning and timing

stability .

x

Page 12

PREFACE

to the first edition

This book is the culmination of years of work and study into the pedagogy of music technology, and I

fear it is also just the beginning, as there will always be more to learn about this exciting new field. I

have little hope of these volumes catching on as standard works, as they are highly instrument-specific.

However, I feel that they have pedagogic merit, and where all else fails, they could even substitute for

an owner’s manual in a pinch.

This book is intentionally printed on every other page so that the student may have a convenient place

to take notes, write questions about readings, and record observations during experiments.

As with any field that is in its infancy and is still rapidly evolving, it seems that there is no good way to

go about writing about music technology. Either a text is so instrument-specific that it becomes outdated very quickly (within five years or so) or it is so general that it is of little merit to the beginning

student. I have elected to opt for the former path, as I have consistent access to the instruments in

question. While this is of the greatest value to me, it is of very little assistance to anyone else who might

be interested music technology in general.

Because I have always taught these lessons in very small groups or as private lessons, I have always

taught them using an outcome-based approach. I have given students a reasonable number of chances

to correct their mistakes and improve their knowledge, as well as improving their grade. I have required my students to pass each quiz at a minimum of the eightieth percentile.

So, I commend this book to the reader... Get what you can out of it. For students who are about to study

music technology privately and will be using these tomes as a course book, I can only say.... be pre-

pared in every way possible! Also be forewarned that questions that are missed on quizzes have a nasty

habit of showing up on the final examination.

Sam Ecoff

January Seven, 1999

Wales, Wisconsin

xi

Page 13

PREFACE

to the second edition

Over the course of two years of teaching music technology, I have stumbled (mostly blindly) upon

several observations as to which students are generally successful in their studies of electronic music

and which students generally fall by the wayside. It seems that it is the students who have a passion

music technology are the students that are most apt to succeed. This observation would seem really

rather obvious at first, but the more one contemplates it, the more ramifications it has.

First, students need to make a commitment to music technology if they are to study it. Although there

is a great deal to know about other musical instruments, piano for instance, relatively little has changed

in the design and playing technique of the piano in the last ten years. In the music technology industry ,

the last ten years have seen one revolution after another including the rise of the home MIDI studio,

digital audio recording for the average musician, and finally, the rise of the complete home project

studio which is actually able to compete in terms of quality with major production facilities. Because

technology is evolving at such a rapid pace, students must be even that much more dedicated to the task

of mastering as much information possible. In this wonderful day of instant information, gathering

information is no longer the great challenge to the student, but rather taking time and finding the energy

to master all of the information which is at the student’s fingertips.

The second observation I have made is that some students wish to learn about music technology in the

‘better-faster-cheaper’ mode, which accomplishes little. To these students, understanding the mechanics and theory of one oscillator frequency modulating another is a complete waste of their time, and

they would much rather just call up a preset on a modern synth which will in their minds do that work

and thinking for them. One must understand that there are always greater possibilities when one can

understand the theory of synthesis which stands behind the sounds, and when a musician is given full

access to all of the parameters of sound available instead of three knobs for ‘realtime control’ and a

bunch of ROM presets sporting today’s latest flavors.

Indeed, there is nothing wrong with using preprogrammed musical patterns and combining them with

other sounds to create a new kind of music, but there is a fine line between a musician and a technician.

While the technician assembles premade parts and works logically with machines to produces sound, a

musician will actually create new loops and adds the dionisian element of the creation of new sound.

As synthesists, computer operators, composers, arrangers, and music technologists, it is important to

keep both the hat of the technologist and the hat of the musician at the ready so that we may freely and

readily switch between the two. Perhaps that is the most important part of music technology: It is not

about being one-dimensional or about confining oneself to a single role. It is about exploring all of the

possibilities and about trying all of the parameters. When access to parameters is denied, either by

companies who produce equipment advertised to fill the role of pro gear or by people who shut out

different possibilities in music technology, it is the music that suffers.

xii

Page 14

THANK YOU

This book is and has been a collaborative effort, as many such large undertakings are. I would be truly

remiss if I missed this opportunity to thank the following people for their assistance in completing this

text. It is, I feel, important to note that many of them performed their services entirely gratis because of

their love of the subject.

I would like to thank Dr. Michael Cunningham who introduced me to the ARP 2600 Synthesizer during

my undergraduate degree at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire. He also deserves credit for coining the term “redundant patch.”

I also owe a great debt of thanks to my loving fiance, Kara for all of the hours she spent proofreading

and inputting corrections on a subject which she cares about only for my sake. She was also incredibly

helpful during the recording sessions for this book, ‘wo’-manning the digital audio workstation to

leave me free to concentrate on the creative aspect of creating patches.

I must also thank my internet friend Roger Lesinski whom I have never met, but has provided wonderful insights and new thoughts into the technical side of this book, and for his great proofreading skill.

This book would still be sitting gathering dust on a shelf as a twenty-one page outline if it were not for

the many students whom I used as guinea pigs while I was developing this book. I owe them a great

debt of thanks for their continued patience and also their assistance in proofreading. (It is sometimes

embarrassing to admit that 10-year old students found many errors that I and the rest of my proofreading team missed!)

I would be remiss if I forgot to mention Ihor “E” Tanin of “E” Lectronix Rock ‘n Roll Hospital in New

Berlin Wisconsin. Not only did he restore my ARP 2600 at a fantastically low price, he also put up with

my phone calls three to four times per week for several months. I also owe a great debt to Timothy

Smith of The Audio Clinic/Weyer-Smith Labs in Billings, Montana. He did a wonderful job of repairing my broken 3620 keyboard, and his knowledge of the 2600 was truly amazing and invaluable.

Finally, I would like to thank my uncle, David Reed who ever so kindly supplied me with the paper I

needed to print the very first copy of this book when I was too poor to purchase paper myself, and to my

parents who have always supported my efforts, and who put up with years of bleeps and bloops coming

from their basement while I learned how NOT to program synthesizers. To all of these people I am

grateful!

xiii

Page 15

ABOUT THE FORMAT OF THIS BOOK

This book has many facets and serves many purposes to many people. While it is primarily geared

towards an academic setting where the basic concepts of subtractive synthesis may be introduced, it

can also be of value in other ways, which are best left to be discovered by the reader.

This book does not start from ground zero. It assumes that the reader has a small amount of knowledge

in the area of basic acoustics. It is important to understand how sound travels, the concept of harmonics, frequency and how it is measured, basic waveforms and their harmonic content. It is common

practice to begin a book such as this with a short chapter on acoustics, but since there are so many

excellent books which cover these topics on a very accessible level, these topics have been omitted

from this book. For persons interested in reading these books (it never hurts) a short list can be found in

Appendix One.

The book itself is grouped into five units. These units are then split into parts called sections. I felt that

this was a more appropriate term than chapter since modular synthesizers are sectional devices by

nature. Each section has several subheadings and illustrations. Following each section of text is a set of

experiments that should be performed on the instrument. There is no substitute for hands-on experience. Following the experiments are a set of review questions and a list of all of the important terms

which were introduced in that section. These will primarily be of interest to persons in an academic

setting, but can also serve as a memory refresher for the casual reader.

The rear of the book features a glossary of terms, including some background terms which are not

included in the text itself. An index is also present for easy reference of terms and concepts.

This book includes an audio CD which contains sounds played on an ARP 2600. This disc serves three

purposes. First, it allows people to check the results of their experiments to see if they have come up

with the correct sound. Secondly , it allows people who do not have access to a 2600 to hear the results

of each audio experiment and some examples in the text. It will also allow them to hear what this

marvelous instrument can do. Finally, it can be used as a source of analog synthesizer samples for a

sampler . (Please read the sample use agreement on page ii if you intend to use the CD for this purpose.

The license granted to you is fairly unrestrictive, but there are certain legal obligations which must be

met if the disc is to be used for this purpose.)

One final note about this book is that in many of the examples, the subject in the experiment is referred

to as ‘Bob’ or ‘Wendy .’ This is in honor of Dr. Robert Moog and Wendy Carlos. Dr. Moog invented the

first commercially available synthesizer and invented many of the modules described in this book.

Wendy Carlos is an excellent musician/composer/inventor whose wonderful recording “Switched-On

Bach,” performed on Bob Moog’s Series IIIp synthesizer, still holds the record as the best selling

classical album of all time.

xiv

Page 16

SECTION

1

GENERAL CONTROLS

INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

The ARP 2600 was designed and manufactured at a point in time when synthesizers had just emerged

as a musical instrument (the late 1960’s), and most people had no idea how to use and program them.

Because of this, the ARP company designed a synthesizer whose primary purpose was to teach people

about synthesizers. The ARP 2600 was manufactured from 1970 to 1980, which is a very long production run for a synthesizer by today’ s standards. Its designers did everything they could to make it easy

to understand. For instance, all of the controls are laid out so that when creating sounds, they start at the

left side of the synthesizer and move towards the right. This is the way most sounds are created, just

letting the electronic signals flow from left to right. The ARP 2600 is much like an assembly line in this

way. Each part adds to or changes the sound a little bit until a finished sound emerges at the end. The

2600’s designers also used white diagrams on the

instrument’s front panel to attempt to show users

where signals were flowing within the instrument.

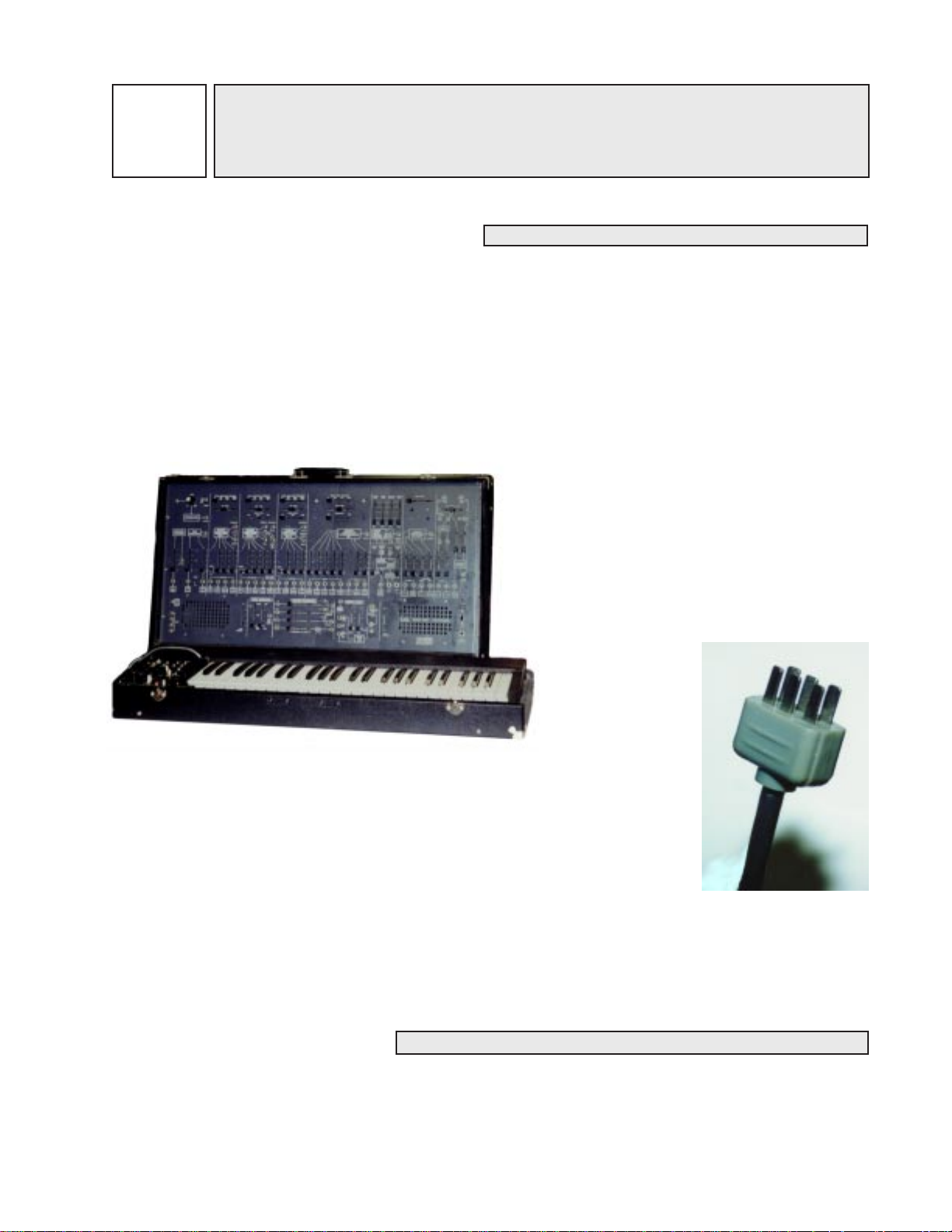

In Figure 1-1, one can see that the ARP 2600 is

actually two separate parts: A keyboard unit and a

cabinet unit. The keyboard must be connected to

the cabinet in order for the keyboard to function,

because the keyboard

draws power from

the cabinet. However, it is entirely

Figure 1-1 The ARP 2600

without the keyboard attached. It still functions perfectly well. In fact, many

of the experiments in this book do not require the keyboard.

possible to use the

ARP 2600’ s cabinet

The connection to the keyboard is established with a single cord. The cord is

permanently attached to the keyboard at one end, and has a multipin plug at

the other end. This design was changed several times by ARP, and it is entirely

possible to find keyboards made for the 2600 which do not follow this design.

(e.g. some earlier models have cables which can be unplugged from both ends.)

A model 3620 keyboard was used for purposes of this book. Notice in Figure 1-2 how many connectors

there are on the plug which connects the keyboard, and keep this information in mind. For now , it is just

necessary to know that the keyboard receives power from the cabinet through this cable.

Figure 1-2: The keyboard’s

multipin connecting cable

THE BALANCE OF POWER

The ARP 2600 gets power from a household electrical outlet via a three-prong cord which plugs into

the right side of the cabinet. The pins are aligned in such a way that the cord cannot be plugged in

upside down. However, the plug that connects with the AC outlet is not polarized and can be connected

in either direction.

001

Page 17

002 - SECTION ONE: GENERAL CONTROLS

The main power switch interrupts incoming electricity so that the ARP cabinet and its keyboard can be switched on and off. It is located at the lower

right hand corner of the cabinet, just above the headphone jack. (See Figure

1-3) Notice that when the synthesizer is switched on, the red light above the

switch goes on. This is the only visual indication that the power is on. There

is not a separate on/off switch for the keyboard; it is switched on when the

cabinet is switched on. When turning the synthesizer on, it is always a good

idea to make sure that the synthesizer has been zeroed (see below) and that

there are no additional cables connecting the 2600 to other devices in the

studio. This insures that no damage will be done to the synthesizer or other

studio devices, and that the synthesizer isn’t gong to make some sort of a

terrible squealing sound or something worse.

SPEAKING OF WHICH

One can see that the ARP 2600 has builtin speakers. Each speaker has its own volume control. This control is pictured in

Figure 1-4. The ARP also has a quarterinch jack into which one can plug a pair of

stereo headphones. The headphone jack is

located just below the main power switch

on the cabinet. (See Figure 1-3) Although it accepts stereo headphones,

the ARP 2600 is a monaural synthesizer. (I.e. the same signal is fed to

both the right and left earphones) The only exception will be explained

in Section 9.

Figure 1-3: The ARP 2600’s

headphone jack, power

switch, and indicator light

On some synthesizers, plugging headphones in will interrupt sound

Figure 1-4: A speaker volume

control

the ARP was designed before many of the professional standards were developed, and plugging in

headphones cuts off the speaker’s output entirely, even if the volume level is set as loud as possible.

going to the speakers. On most professional-level synthesizers, this

won’t happen, (most pro-level synthesizers don’t have speakers) but

ZEROING THE SYNTHESIZER

Sometimes when a student starts to use the synthesizer, someone else has been using it before them.

This can make working on the synthesizer very frustrating, since one doesn’t know how the last person

was using it, and some switch or fader might be set in a way that would keep the synthesizer from

functioning the way it normally would. It is best to return all of the knobs, faders, and switches to their

original position, and to remove all patch cords (see page four) from the synthesizer to prevent this sort

of frustration. This is called zeroing the synthesizer. The synthesizer should be zeroed each time one

begins using it. When attempting a new sound, it is also wise to zero the synthesizer , as the instrument

might not behave the way one expects because of some earlier setting. Diagram 1-1 on page 3 illustrates the proper settings of each knob, switch, and slider when zeroed. Notice that all patch cords have

been removed.

Page 18

RANGE

X1000

X100

X10INGAIN0MAX

PREAMPLIFIER

OUT

ENVELOPE

FOLLOWER

OUT

PRE-

AMP

RING

MODULATOR

OUT

VCO

1

VCO

2

AUDIODCVCO

2

S/H

OUT

KBD

CV

ADSR

KBD

CV

OUT

MULTIPLE

LEFT

SPEAKER

INITIAL OSCILLATOR FREQUENCY

10 100 1KHz 10KHz

.03 .3 3.0 30

FINE TUNE

VOLTAGE

CONTROLLED

OSCILLATOR

VCO-1

AUDIO

L F

KBD ON

KBD OFF

FM CONTROL

OUTPUTS

SAWTOOTH

SQUARE

VOLTAGE

CONTROLLED

OSCILLATOR

VCO-2

AUDIO

KBD ON

KBD OFF

FM CONTROL

OUTPUTS

S/H

OUT

KBD

CV

ADSR

VCO

1

NOISE

GEN

PULSE WIDTH

MODULATION

INITIAL OSCILLATOR FREQUENCY

10 100 1KHz 10KHz

.03 .3 3.0 30

FINE TUNE

PULSE WIDTH

10% 50% 90%

TRIANGLE

SAWTOOTH

PULSE

PWM

INITIAL OSCILLATOR FREQUENCY

10 100 1KHz 10KHz

.03 .3 3.0 30

FINE TUNE

PULSE WIDTH

10% 50% 90%

VOLTAGE

CONTROLLED

OSCILLATOR

VCO-3

OUTPUTS

SAWTOOTH

AUDIO

L F

KBD ON

KBD OFF

FM CONTROL

KBD

CV

ADSR

NOISE

GEN

VCO

2

PULSE

NOISE GENERATOR

NOISE

GEN

OUTPUT

MAX

MIN

WHITE

PINK

LOW

FREQ

SINE

VOLTAGE

CONTROLLED

FILTER/RESONATOR

VCF

AUDIO

OUTPUT

KBD

CV

ADSR

VCO

1

NOISE

GEN

INITIAL FILTER FREQUENCY

10 100 1KHz 10KHz

FINE TUNE

RESONANCE

MIN MAX

CONTROL

RING

MOD

VCO

2

VCO

3

VCO

2

ATTACK

DECAY

SUSTAIN

RELEASE

ENVELOPE

TRANSIENT

GENERATOR

OUTPUT

ATTACK

TIME

DECAY

TIME

SUSTAIN

VOLTAGE

RELEASE

TIME

A

DSR

ATTACK

RELEASE

ENVELOPE

TRANSIENT

GENERATOR

OUTPUT

ATTACK

TIME

RELEASE

TIME

A

R

MANUAL

START

S/H

GATE

KEYBOARD

GATE/TRIG

TRIG

GATE

AUDIO

VCF

ADSR

AR

CONTROL

LINEAR

EXP’L

SAMPLE & HOLD

NOISE

GEN

VOLTAGE

CONTROLLED

AMPLIFIER

OUT

INITIAL GAIN

ABC

ELECTRONIC

SWITCH

S/H

OUT

EXT

CLOCK

IN

INT

CLOCK

OUT

LEVEL

RATE

INTERNAL

CLOCK

RIGHT

SPEAKER

ARP

MODEL 2600

AUDIO

VCF

MIXER

OUT

MIXER

PAN

LEFT

INPUT

REVERB-

ERATOR

LEFT

OUTPUT

RIGHT

INPUT

STEREO

PHONES

POWER

-10V

KBD CV+10V

ENV FOLL

123467LAG

5

INVERTER

INVERTER

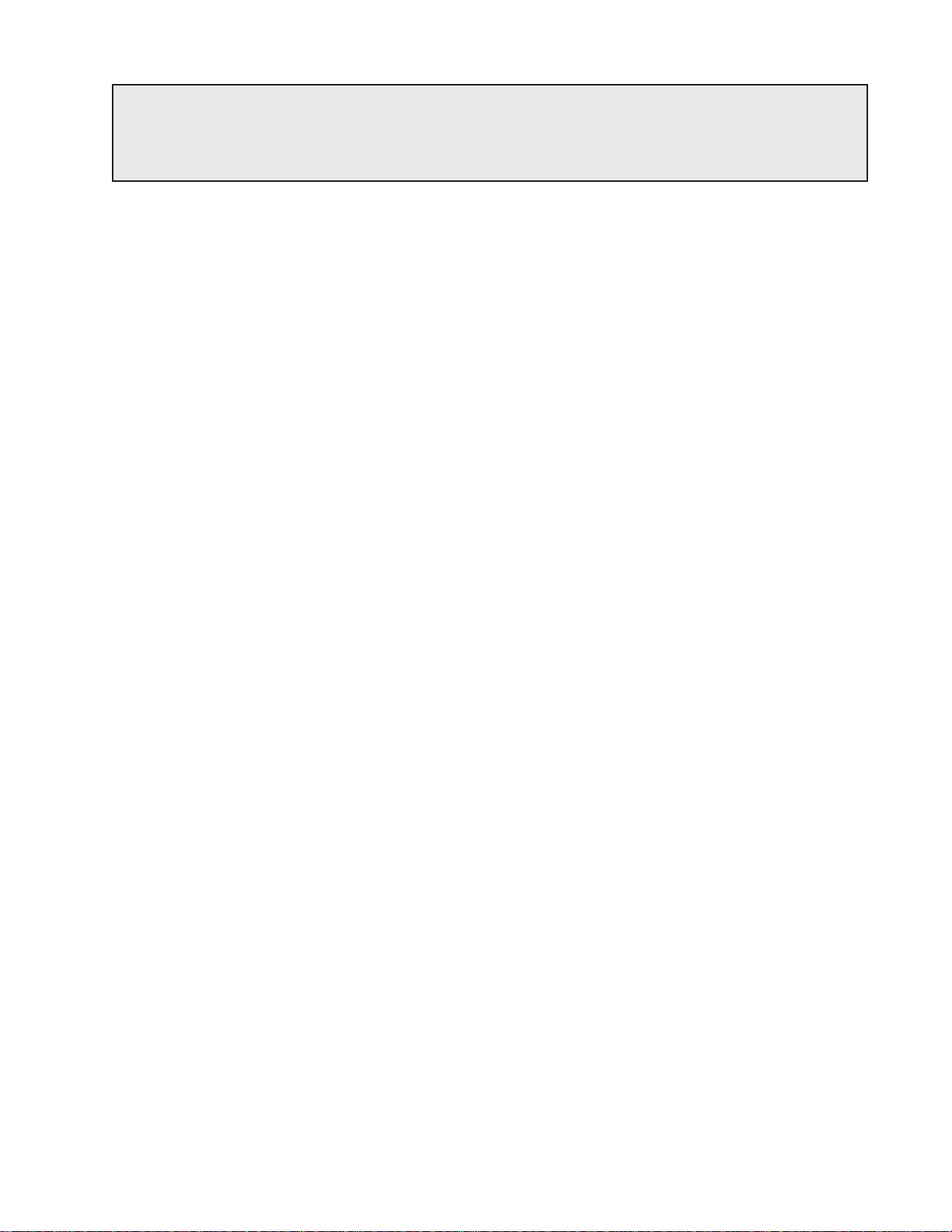

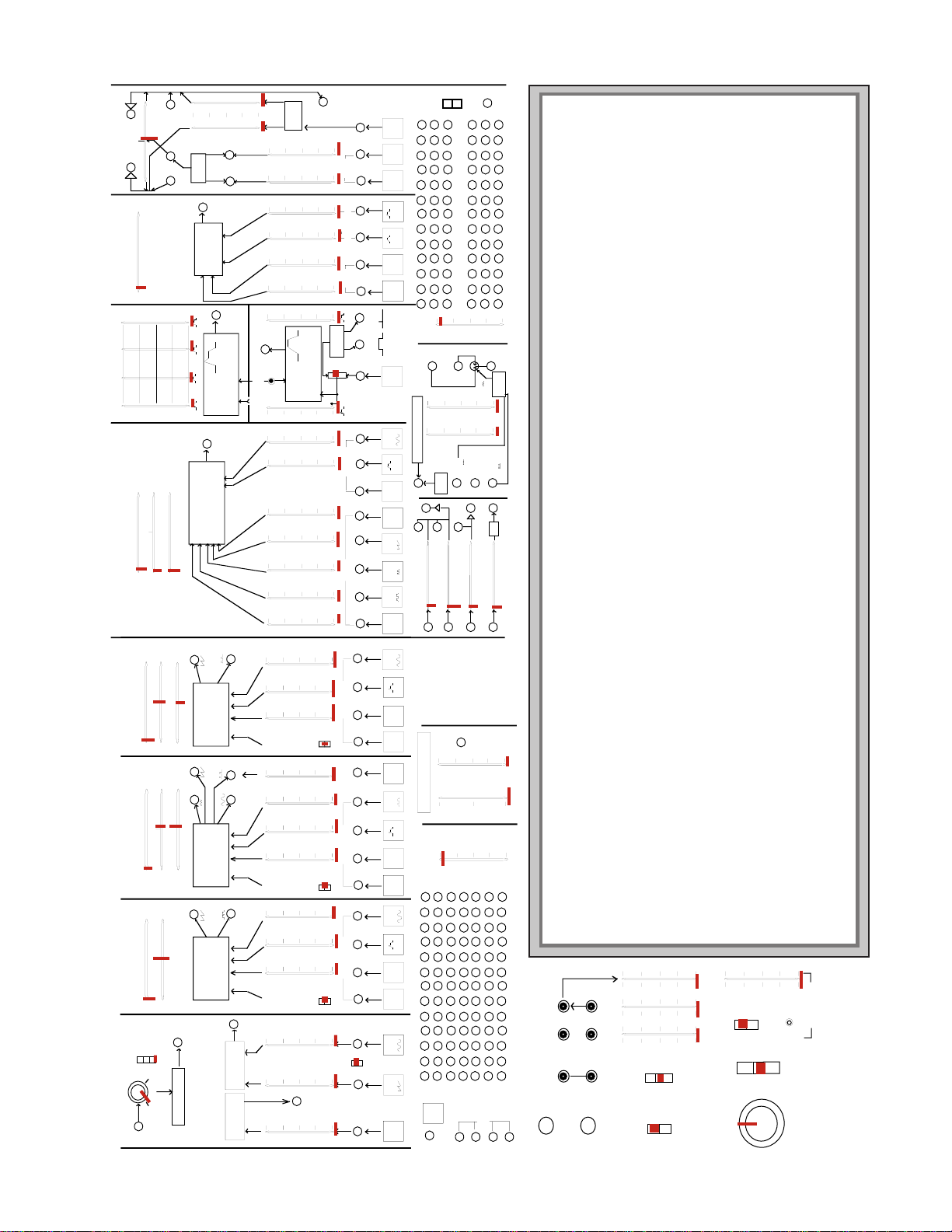

Diagram 1-1 indicates the proper setting of each knob, switch and slider when the ARP 2600 is zeroed. The upper

VIBRATO

DEPTH

VIBRATO

DELAY

LFO

SPEED

PITCH BEND

2 OCTAVES

UP

2 OCTAVES

DOWN

TRANSPOSE

ON

OFF

PORTAMENTO

SINGLE

MULTIPLE

TRIGGER

MODE

EXT.

VIBRATO

IN

LFO

LFO

LFO

DELAY

UPPER

VOICE

KYBD

AUTO

REPEAT

INTERVAL

LATCH

PORTAMENTO

FOOTSWITCH

diagram represents the 2600’s cabinet while the small lower diagram represents the controls on the keyboard.

ARP made several different versions of the 2600. These are easiest to tell apart by the markings on the cabinets.

The earliest models featured blue metal cabinets and a long wooden handle across the top. This model also lacks

fine tune controls on VCO-1 and the VCF. While these models were very stylish, they were not particularly road-

worthy . Later models featured a gray cabinet face in a wooden box covered in black Tolex (a vinyl-like substance

which is very durable). These models also had a small plastic handle on the top of the cabinet and on the key-

board. These models are the most common version of the 2600, and one can be seen in Figure 1-1. The last 2600’ s

ARP produced had a dark gray face with orange and white lettering, again in the Tolex case.

ARP also produced several different models of keyboards. The last ones produced have significantly more fea-

tures than the early models (more on this in Section 13). The keyboard controls shown in the diagram are those

from the model 3620 keyboard, which was the last model ARP produced.

1-1

DIAGRAM

003

Page 19

004 - SECTION ONE: GENERAL CONTROLS

PARAMETERS AND VALUES

Soon the synthesizer’s functions will be explained, but it is important to first understand the concept of

a parameter. A parameter is simply something that one can change. A value is one of the possible

settings of a parameter. For instance, if Bob looks at a light switch, he can see that the switch itself

represents the parameter. It is something whose value he can change. This parameter has two possible

values: On and Off. A fader , on the other hand, is said to have an infinite number to values, although its

range of values may be measurable.

PATCH CABLES

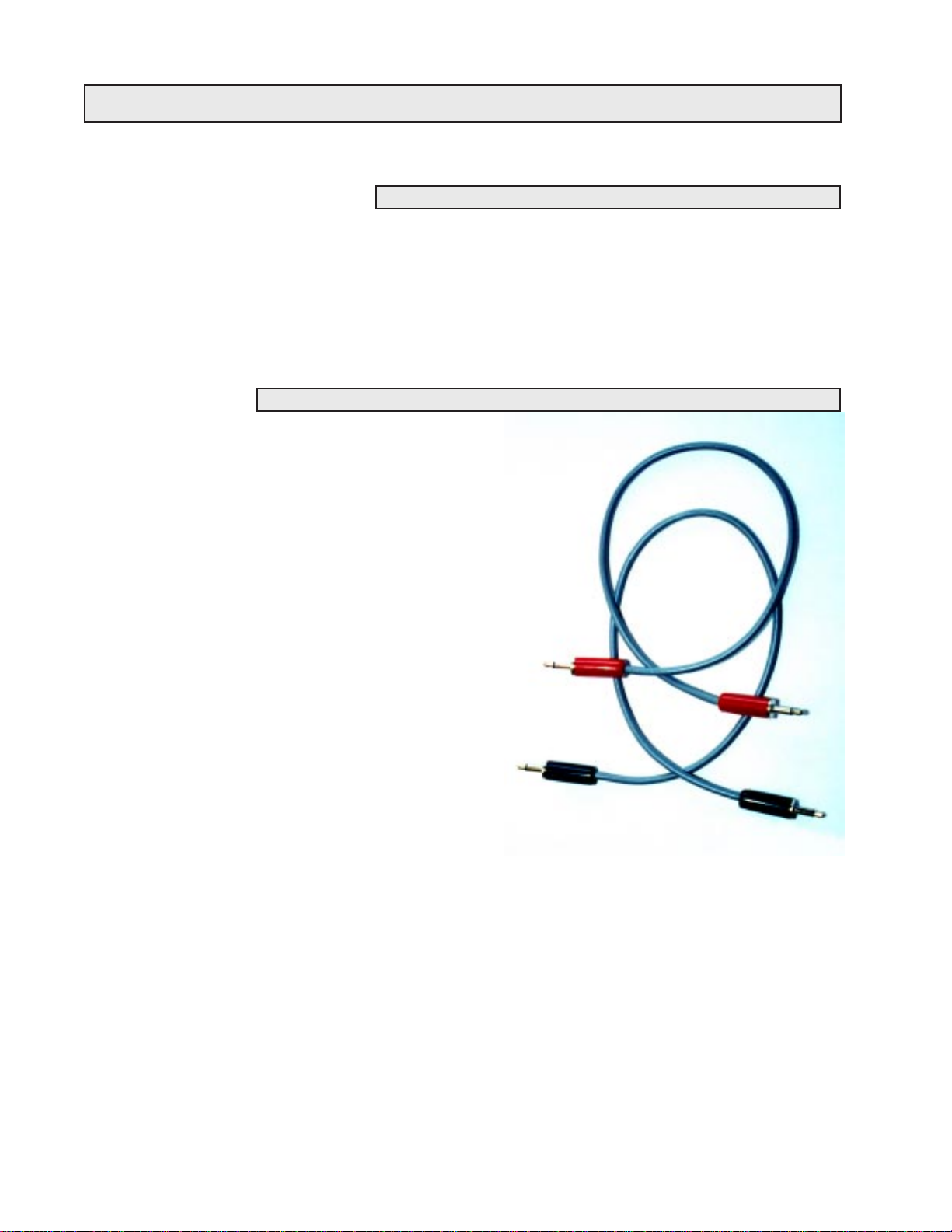

Thin cables called patch cords or patch cables (See Figure 1-5) are used to

connect different parts of the synthesizer together. They consist of two

plugs which have been soldered to either end of a length of wire. This

wire can be of any length. Some setups offer cables of just one length,

while other setups have many different lengths of cables. The cables

ARP included with the 2600 were all of the same length, but few of

them are still around today as the wire has usually deteriorated to the

point where the cables are unreliable. Many owners of 2600’s today

either purchase cables from companies which specialize in cables or

make their own from parts acquired from electronics stores and supply houses.

Figure 1-5: Two

homemade

patch cords

Patch cables are pretty durable, but one must take care of them if they

are expected to last a long time. First, don’t ever leave them lying around

on the floor as they can be stepped on or worse yet, rolled over with a

chair. Second, whenever a patch cord is removed from a

jack in the ARP’s cabinet, pull it out by the plug rather

than by the cord. It is entirely possible to rip the cord right off of the plug if it is

pulled hard enough, because the only thing holding the two together is a drop of solder.

Third, do not bend the cable itself at tight angles, as doing so can actually sever the wire inside the

casing. Finally, when finished with them, patch cords should be stored in a safe location, away from

extreme heat and off the floor where they could become damaged. A simple hook mounted on a wall or

the side of a table is a great place to store patch cables.

Many studios use two different colors of patch cables when patching the ARP 2600; red and black. The

cables are identical other than the color of the plug and/or wire casing, and don’t function any differently, but they are used for different purposes to make it easier to understand the way the synthesizer

works. For audio signals, black cables are used. Audio signals are signals that are the raw sound that

one eventually wants to hear. Red cables are used to carry control signals. Control signals are signals

which one doesn’t intend to hear and which will be used strictly to effect change on some other part of

the synthesizer. (The difference between audio and control signals will become clearer in time.) The

next section contains a great deal more information about control signals. For now , just remember that

black is used for audio signals, and red is used for control signals.

Page 20

SECTION ONE: GENERAL CONTROLS - 005

MODULAR SYNTHESIZERS AND CONNECTIVITY

A modular synthesizer is a synthesizer that is made up of several different discreet devices which can

easily be seen and can be connected to each other in any order the user pleases. These devices are called

modules. Almost all of these modules are housed in the synthesizer’s cabinet. On the ARP 2600, it is

possible to actually see the individual modules. They are separated on the front panel of the cabinet

with heavy white lines. With larger modular synthesizers, companies often allowed users to pick and

choose which modules they wanted to make up a particular synthesizer, and as such, the modules were

entirely separate devices which didn’t share a common front panel. On a truly modular synthesizer,

these different modules are not connected to each other , and the user must connect them together using

patch cords to create sounds. This last point is very important, so keep it in mind.

The patch cords are plugged into little holes on the modules called jacks. These jacks grip the ends of

an inserted patch cord and make an electrical connection. The ARP 2600 uses 1/8 inch phono jacks (see

Figure 1-6) and as such, patch cords must have 1/8 inch phono plugs. Although they all

look the same, it is very important to understand that not all jacks are the same. Some jacks

are inputs, and some jacks are outputs. A jack which allows signals to come in is called an

input, and a jack which puts out signals is called an output. An input must be connected to

an output. Likewise, an output must be connected to an input. Connecting an input to an

input or an output to an output won’t do anything at all. This is analogous to holding the

Figure 1-6:

two 1/8”

jacks

handset of a telephone upside down. Before patching two jacks together, it is very impor tant to make sure that one of them is an input, and one of them is an output. Otherwise, the

connection being made won’t do anything.

The ARP is really a good teacher in that it is very forgiving. If a silly connection is made, such as

connecting an input to an input, or connecting an output to an output, it will not hurt the ARP at all. Just

remember: signals can only come out of an output; they can not go in. Signals can only go into an input;

they do not come out.

MODULAR: THE PROS AND CONS

There are some great advantages to modular synthesizers. First and foremost, one could connect the

modules in any order. It is possible to come up with some pretty wild combinations which are not

possible when dealing with a non-modular synthesizer (called a fixed-architecture synthesizer). Addi-

tionally, students can see each individual module and experiment with them individually, instead of

having to use them in predetermined order.

There are, of course, disadvantages to modular synthesizers as well. First, to create a sound, one must

use several patch cords. Secondly , all of the knobs and sliders must be reset for each different sound, as

most modular synthesizers can’t recall a programmer’s sounds. Most modular synthesizers also allow

the performer to play only one note at a time. Because of this, they are said to be monophonic. Many

modular synthesizers are also becoming vintage instruments (older than 25 years) at this time and are

becoming more and more unreliable. Despite all of these limitations, there is a large potential for

making interesting sounds, and wonderful music.

Page 21

006 - SECTION ONE: GENERAL CONTROLS

ARE SYNTHESIZERS NORMAL?

When sounds are created on the ARP 2600, certain modules must be connected in a certain way , and the

appropriate knobs and sliders must be set just right to produce the desired sound. This collection of

settings of patch cables, sliders, and knobs is called a patch. The term ‘patch’ comes from the patch

cables used make these sounds. Modern synthesizers don’t use patch cables, but individual sounds are

still referred to as ‘patches’.

All of this patching can be a lot of work, and many times, it is desirable to use the modules in a

standard configuration (see Section 8 for more information). It would be very time consuming and

monotonous constantly creating the same patches again and again, so the designers of the ARP 2600

came up with a good solution: normals.

What is a normal? A normal is simply a connection which is made to one of the ARP’ s input jacks from

one of the ARP’s outputs even before a patch cord is plugged into it. Another way to say this: Some

outputs are internally wired to some inputs. All but eight of the ARP 2600’s inputs have something

normalled to them. One can tell if an input has something normalled to it because there is some writing

in a small white box that points to the input. The writing indicates what is normalled to that input.

Another way to think of a normal is as a connection that is premade with an invisible patch cord. It is

not possible for a user to change what is normalled to each input.

BUT WHAT IS NORMAL?

The normal represents the patch which is most commonly used. The ARP’ s

designers made the everyday connections into normals. They didn’t nor mal modules together that one would rarely connect. Thus, it is important

to take note of which modules are normalled together, as this will give a

student some clues as to how the synthesizer will ‘normally’ be patched.

However, there are times when it is undesirable to make that particular

patch or connection which is made by a normal. This is the time when the

input jack will be used, and the normal will be broken. Breaking a normal

means disconnecting that premade electrical connection in the synthesizer . T o break a normal, all one must do is plug a patch cord into an input

jack. When a patch cord is connected to an input jack, two things actually

happen: First, the normal is broken and what was formerly connected to

that input is now disconnected. Second, whatever is traveling down that

patch cord is now connected to the input.

A great example of a normal is the headphone jack. The headphone jack is actually an output, since it

puts out a signal for headphones, but it still represents a normal. Sound is normalled from the synthesizer’s

internal amplifier to the synthesizer’s speakers. When a pair of headphones is plugged into the headphone jack, that normal is broken, and no sound can emerge from the speakers. The ARP 2600 has

thirty-nine inputs that have something normalled to them.

Figure 1-7: Nobody’s

fool. Two dummy plugs

Page 22

SECTION ONE: GENERAL CONTROLS - 007

DUMMY PLUGS

While normals are very convenient, there are times when it is desirable to break a normal without

connecting anything to that particular jack. A synthesist might want to connect a module other than the

one which is preconnected by the normal. One possible solution to this problem is to just plug one end

of a patch cord into the jack, but the problem with this is that the other end of the cord can touch objects

in the studio and create electrical noise. The cable could also pick up electromagnetic interference and

add even more unwanted noise. A dummy plug is a much better solution to this problem.

A dummy plug (see Figure 1-7 on page six) is just a plug from a patch cord without the cord. Using a

dummy plug, a normal can be broken without all of the disadvantages of plugging in one end of a patch

cord. Throughout the experiments with the ARP that follow, the reader will make use of the dummy

plug.

MODULAR VS. SEMI-MODULAR

As mentioned before, on a truly modular synthesizer, none of the modules are actually connected. Of

course, normals actually make some connections between modules without using patch cords. So it

would seem that the ARP 2600 is not actually a modular synthesizer. This is true; the ARP 2600 is not

technically a modular synthesizer. It is still possible to use it as a modular synthesizer, though, and it

retains all of the advantages of a modular synthesizer without some of the inconveniences. Because of

these subtle differences, the ARP 2600 will be referred to as a semi-modular synthesizer. Basically,

‘semi-modular’ simply means that many of the modules have normalled connections.

CLONING IN THE SYNTHESIZER WORLD

(OR: MULTIPLES AND HOW TO USE THEM)

One of the first modules one will encounter on the ARP 2600 synthesizer

is the multiple. It is fairly easy to understand and use, and it really adds to

the flexibility of the synthesizer. The multiple, which is located in the

lower left hand corner of the cabinet, simply makes extra copies of any

signal. (See Figure 1-8) The multiple is made up of four jacks, which are

all wired together internally . If one connects an output to any one of those

jacks, three identical copies will come out the other jacks. This duplication occurs regardless of which jack one plugs into. Using the multiple, it

is possible to make up to three copies of a signal. This will really come in

handy later on.

Conversely , it is possible to plug three different signals into the multiple,

they will be summed, and will all be output at the remaining multiple

jack. While this is possible, it is not recommended. To properly mix sig-

Figure 1-8: The ARP

2600’s multiples

nals together, they must be passed through a device called a mixer , which

will be explored a bit more in Section 6.

Page 23

008 - SECTION ONE: GENERAL CONTROLS

CONTROL VOLTAGES AND VOLTAGE CONTROL

To make a sound, different synthesizer modules are connected together using patch cords. However,

the system that these modules use to control each other hasn’t been explained yet. Several different

systems have come and gone over time. The ARP 2600 uses one of the earliest, and most primitive. (It

is one of the easiest to understand, though!) The 2600 uses a system called voltage control to send

signals from one module to another.

In a voltage control system, modules send out a raw electrical voltage that represents a value. The

greater the voltage, the higher the value it represents. This voltage is called a contr ol voltage. The term

voltage control is used to describe a system where these control voltages are used. Synthesizers do not

use a lot of voltage to send these signals, so one is never in danger of getting an electrical shock from

the synthesizer, as long as the cabinet is not opened, which is fairly difficult to do, anyhow.

Another way to remember these two, similar sounding terms is to remember that ‘voltage control’ is

usually used as an adjective. It describes a synthesizer or a module of a synthesizer (e.g. the ARP 2600

is a voltage controlled synthesizer). Meanwhile, ‘control voltage’ is a noun. One might say that a

control voltage is being produced by a certain module.

VOLTAGE CONTROL, PARAMETERS & VALUES

Voltage control will be discussed in greater detail in the next section when it is possible to actually hear

its effects. For now, students should just try to understand the basic concept. Earlier on in this section

it was said that a parameter is something that can be changed, and the possible settings of that parameter are its possible values. On the ARP 2600, parameters are represented by control inputs. Values are

represented by control voltages. By connecting a control voltage to an input jack, that value is assigned

to whatever parameter the input jack represents. This will become clearer over time, especially when it

appears again in the next section.

KEYBOARD CONTROL VOLTAGE

One device that creates control voltages is the keyboard. It was mentioned earlier in this section that the

keyboard receives voltage from the cabinet through its connecting cable. However, the keyboard is

also returning several signals of its own, one of which is the keyboard control voltage. The higher the

key played, the greater the voltage the keyboard sends out. This voltage goes back to the cabinet and

comes out the Keyboard CV output jack on the front panel of the cabinet. This jack is located just above

the multiple and can be seen in Figure 1-8 on page7. This voltage is then used to control the pitch of the

oscillators, as will be explained in the next section.

Page 24

SECTION ONE: GENERAL CONTROLS - 009

EXPERIMENTS FOR SECTION ONE:

1. Demonstrate left to right signal flow on the ARP’s cabinet. Why is the synthesizer designed this

way?

2. Locate the keyboard and the cabinet of the ARP 2600.

3. Locate the cable which connects the keyboard and the cabinet.

4. Demonstrate the technique for ‘zeroing’ the synthesizer and demonstrate power-up procedure.

5. Locate main power switch, the light above it, and main power cord.

6. Locate an input, and notice the symbol below it indicating its normal.

7. Locate the speakers and their volume sliders.

8. Locate the headphone jack. Demonstrate what happens to the speakers when headphones are plugged

into the headphone jack. What is this phenomenon called?

9. Demonstrate correct use and care of patch cords. Notice the colors and different lengths.

10. Demonstrate a dummy plug.

11. Locate the multiple on the front panel of the ARP.

12. Locate the keyboard control voltage output on the front panel.

Page 25

010 - SECTION ONE: GENERAL CONTROLS

REVIEW QUESTIONS FOR SECTION ONE:

1. When was the ARP 2600 made? Is this a typical production time span for a synthesizer?

2. Why is the synthesizer designed to let signals flow from left to right? What was the primary goal of

designing the ARP 2600 synthesizer?

3. Name the two main parts of the ARP 2600. Is it possible to use one part without the other? What is

one purpose of the cable that connects the two parts?

4. What must be done before the synthesizer is turned on to avoid damage to other studio devices?

5. What happens to the speakers if you plug headphones into the synthesizer? How is this a little

unusual?

6. What does ‘zeroing the synthezier’ mean? Why is it important to zero the synthesizer before using it?

7. How should patch cords be treated to protect them? Which cable generally represents which signal?

8. List the advantages and disadvantages of modular synthesizers.

9. Describe how modules are patched together.

10. What is the difference between Voltage Control and Control Voltage?

11. How does voltage control relate to parameters and values?

12. Where does the main power cable connect to the cabinet?

13. Should inputs be connected to inputs or outputs?

TERMS TO KNOW:

Monophonic

Audio Signal

Control Signal

Control Voltage

Dummy Plug

Fixed-architecture Synthesizer

Input

Jack

Keyboard Control Voltage

Modular

Module

Multiple

Normal

Output

Parameter

Patch Cable

Patch

Semi-Modular

Value

Voltage Control

Zero

Page 26

SECTION

2

VCO-1

ALL ABOUT OSCILLATORS

Oscillators are the fundamental part of any synthesizer . They are the module that creates the raw sound

that will be shaped and molded by all the other parts of the synthesizer . Oscillators function by putting

out voltage in a pattern. The faster they put out the pattern, the higher the frequency they produce.

When this output voltage is amplified and connected to a speaker, a sound can sometimes be heard.

Some people think that oscillators only put out voltage when a key is being played on the keyboard.

This really isn’t true, though. Oscillators constantly oscillate at a specified rate, even if a key isn’t being

played. Another word for rate is frequency and it is measured in Hertz (Hz).

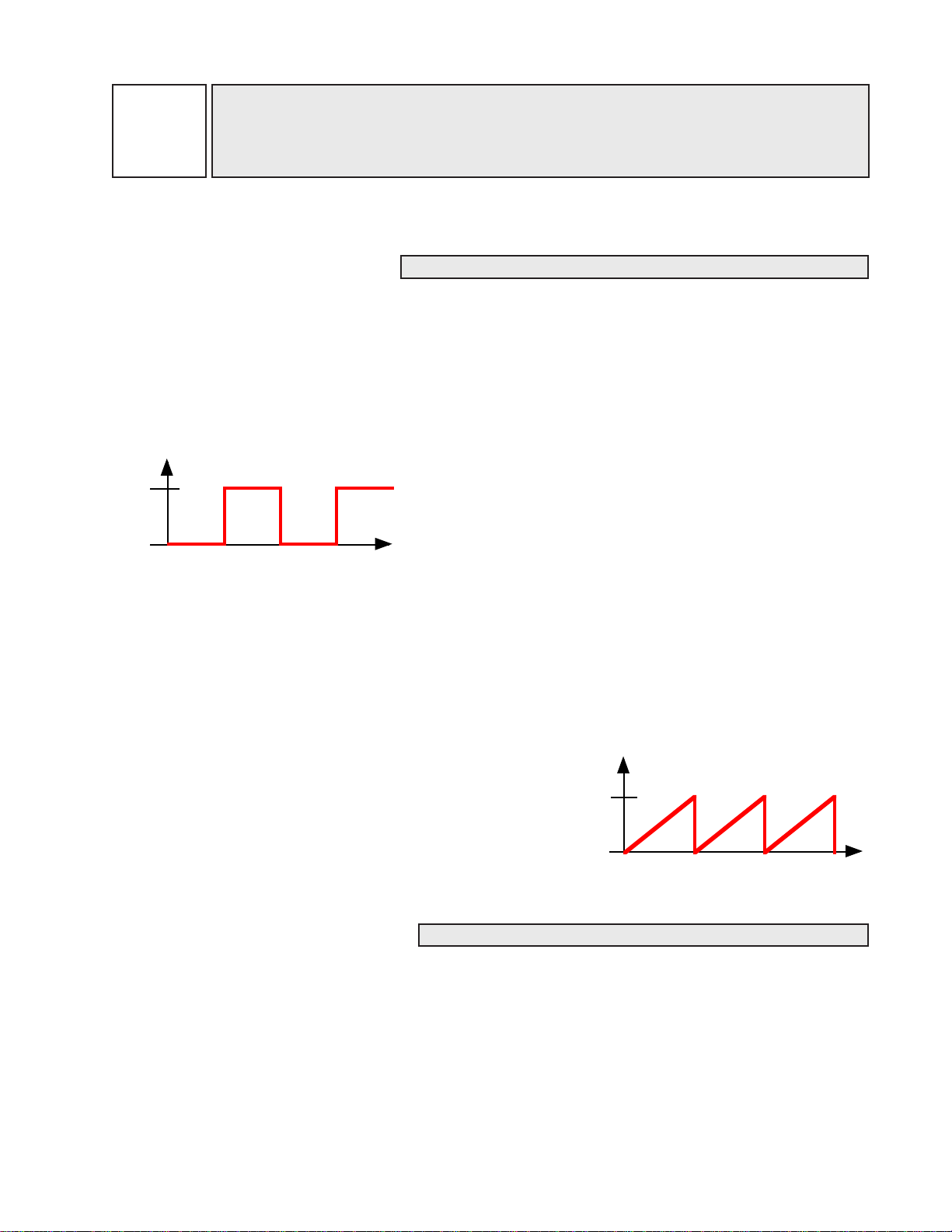

VCO stands for voltage controlled oscillator. This means that

+10

Volts

0

time

Figure 2-1: A square wave

this module is an oscillator and can produce audio signals and

control signals. It also means that at least one of its parameters

can be controlled via voltage control. This is another perfect

example of the term ‘voltage controlled’ being used as an adjective as mentioned in Section 1.

Most oscillators are capable of producing different tone colors. This is accomplished by putting out

voltage in a pattern called a waveform. For instance, to create a square wave (see Figure 2-1), the

oscillator will put out no voltage for a moment, then put out ten volts for a moment. To produce a saw

wave (see Figure 2-2), the oscillator must increase its voltage gradually to ten volts, then drop sharply

back to zero volts.

Repeating a waveform very quickly (often thousands of times

per second) produces an electronic signal which human ears

will perceive as a tone after it is amplified and is connected to

a speaker. Notice when the raw output of an oscillator is connected to a speaker that the sound is not particularly interesting

to listen to. Because the sound is static and unchanging, it is

rather monotonous or boring.

10

volts

0

time

Figure 2-2: A saw wave

THE OSCILLATOR’S TIMBRE

Oscillators have two different parameters, the first of which is timbre. T imbre comes from French, and

is pronounced tam-ber. Timbre means tone color or raw sound. When timbre changes, the shape of the

waveform changes. One can easily see by comparing Figures 2-1 and 2-2 above that a square wave

does not look anything like a saw wave. The two will sound different as well, just the way a piano

sounds different from a trumpet, even if each sounds the same note.

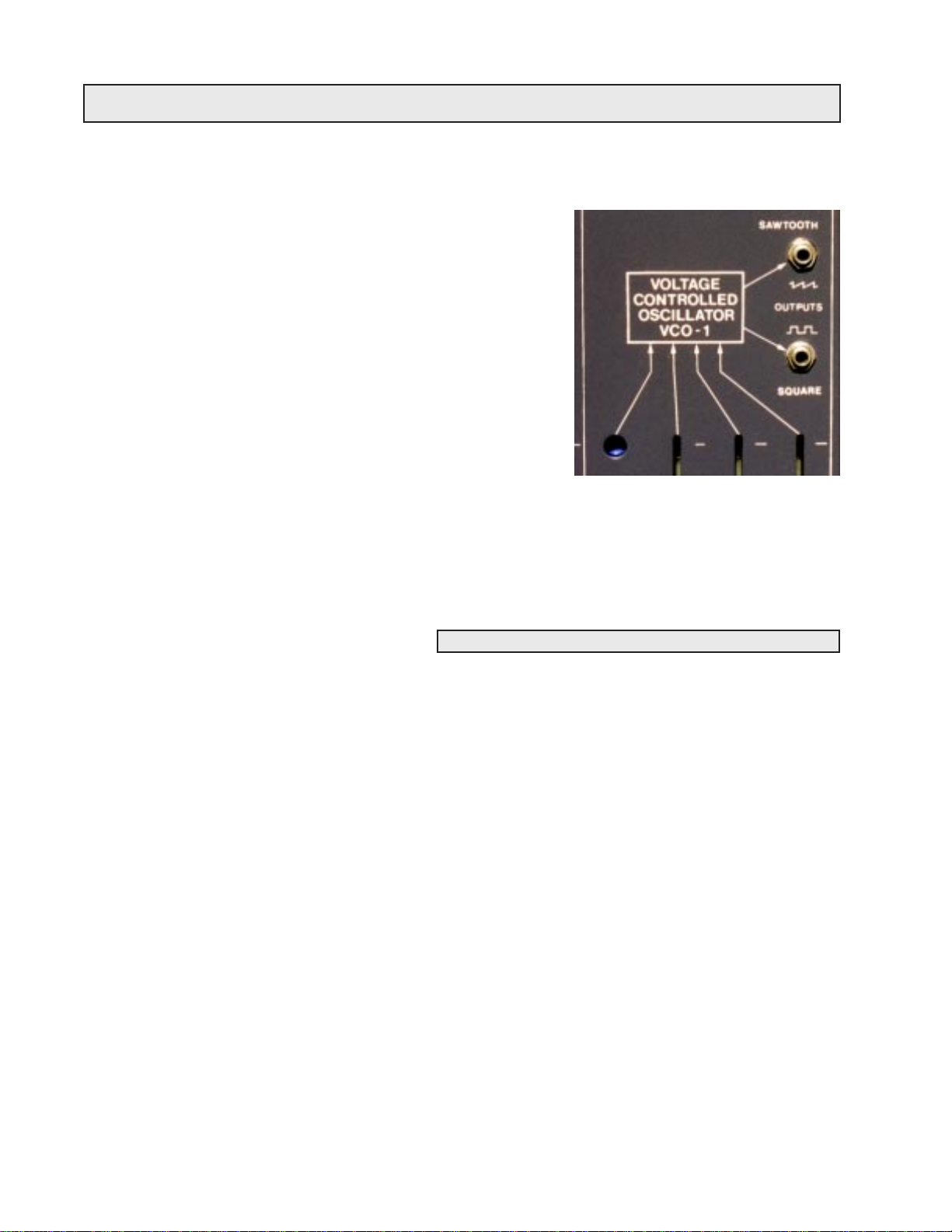

One selects a timbre by connecting a patch cord to one of the oscillator’s two outputs. In Figure 2-3,

VCO-1’s two outputs jacks can be seen. The top jack constantly puts out a saw wave and the bottom

jack puts out a square wave. It is very important to note that connecting a patch cord to one of the two

011

Page 27

012 - SECTION TWO: VCO-1

outputs is the only way the timbre can be changed. For instance,

if one wishes to hear a square wave, one must connect the square

output of VCO-1 to the speakers. The only way to change the

timbre that VCO-1 is creating is to manually connect the patch

cord to the saw output. It is important to also realize that both

outputs of an oscillator can be used at the same time so that both

timbres can be heard simultaneously.

Although everyone will perceive timbres slightly differently , it is

possible to make some generalizations about them which will

guide the student in his or her studies. The saw wave has lots of

harmonics, and as such has a sound that sounds buzzy . The square

wave, on the other hand, has only the odd harmonics, and as such,

it has a rather hollow sound. Take a moment now to listen to CD

track 01. Several tones are played by VCO-1. First, the notes are

played with a square wave produced by VCO-1. Then, the notes are played with a saw wave produced

by VCO-1. Remember to listen for the raw sound or timbre of the sound, and not how quickly or

slowly the sound begins or ends.

VCO-1’s saw and square outputs.

Figure 2-1:

THE OSCILLATOR’S FREQUENCY

The second parameter of oscillators is frequency . Frequency is often referred to as pitch by musicians.

While selecting a timbre is fairly simple, controlling frequency is a bit more involved. Frequency is

controlled in several different ways. First, VCO-1 has a coarse frequency setting. This fader can change

the oscillator’s frequency over a very large range. It is possible to make the oscillator oscillate so

quickly that it can’t be heard at all (a supersonic tone - 20 kHz or higher) or so slowly that a tone can’t

be perceived (a subsonic tone - 20 Hz or lower).

When it is necessary to tune an oscillator to another source such as another oscillator, one needs better

overall control than the coarse tuning slider can provide. This is the job of the fine tuning slider. (The

earliest version of the ARP 2600 lacked the fine tune control on VCO-1.) See page three for more

information.) The fine tuning slider increases or decreases the pitch a small amount from wherever it

has been set by the coarse tuning slider . When attempting to tune an oscillator to match another source

such as another oscillator, one should get the frequency close to that of the other source using the

coarse slider, then tune it in perfectly using the fine tuning slider.

As the oscillator’s tuning gets close to the pitch of the other source, a series of ‘beats’ can be heard.

These beats are a sort of pulsing in the sound which occur when the waveforms of the two sources

alternately cancel and reinforce each other . This results in a small change in volume which is perceived

as beats. As the frequency of the two sources gets closer and closer together, the beats will gradually

slow until finally, they stop, indicating that the two sources are perfectly in tune. Take a moment now

to listen to CD track 02. T wo oscillators are being tuned together . Listen for the slowing of the beats as

they get closer to being in tune.

Page 28

SECTION TWO: VCO-1 - 013

MODULATION: THE KEY TO THE WORLD OF SYNTHESIZERS

The third way the oscillator’s frequency is controlled is by the amount of voltage that it receives. This

is why this oscillator is called a Voltage-Controlled Oscillator; its frequency can be controlled by an

external voltage. The more voltage the oscillator is fed, the higher the frequency or pitch it will produce.

Things to this point have been pretty straightforward, but now comes the tricky part. On synthesizers,

a technique called modulation is frequently used. Modulation allows one module to change the value of

a parameter of another module. The easiest way to understand modulation is by looking at an example.

If W endy is riding in a car and she is attempting to draw a straight line across a piece of paper , she could

represent a module on a synthesizer. The line Wendy is trying to draw on the paper is the parameter

which can be changed. When the driver drives over some big bumps in the road, Wendy’s straight line

is going to be changed with each bump she rides over. So, the road is changing the value of Wendy’s

line. Instead of a nice straight line, she might end up with one that goes all over the page. What is really

happening here is that the texture of the road is modulating Wendy’s drawing.

Whenever modulation occurs, there is a carrier and a modulator. The carrier is the module whose

parameter is being changed (Wendy’s drawing in the example above). The modulator is the module

that is doing the changing (the road in the example above).

Understanding modulation is the key to understanding modular synthesis. Although modular synthesis

is called “modular synthesis” because it involves different modules, it might just as well have been

called “modular synthesis” because the individual modules change, or modulate each other. Understanding modulation is the key to understanding the ARP 2600. Once the concept of modulation is

understood, everything else becomes much more clear, and more complex patches can be attempted.

FREQUENCY MODULATION

While it is not possible to modulate the timbre of VCO-1 from another source (remember: the only way

to switch timbres on VCO-1 is to manually plug the patch cord into a different output), it is possible to

modulate the frequency using a control voltage. (This process will be dealt with in depth in the next

section.) When the frequency of an oscillator is being modulated, this technique is called frequency

modulation. Frequency modulation is often abbreviated ‘FM’.

To modulate the frequency of VCO-1, a control voltage must be connected to one of the four jacks

below VCO-1. (See Figure 2-4 on page 14) These jacks are called frequency modulation inputs and

they are labeled “FM CONTROL” on the cabinet’s panel. When a control signal (like the control

voltage output of the keyboard) is connected to one of these inputs, the stage is set to modulate the

frequency of the oscillator. However, the ARP gives the user some options here. The observant student

will notice that there is something normalled to each FM input jack. These devices will all be discussed

in time. One of the most common examples of frequency modulation is a control voltage from the

keyboard modulating the frequency of an oscillator.

Page 29

014 - SECTION TWO: VCO-1

When plugging into the FM three jacks on the right of

VCO-1, the user can control the amount of control

voltage that will actually get to the oscillator. When

the slider or fader (the two terms are used interchangeably in this book) above a jack is all the way down, no

signal will be passed to the oscillator from that jack.

When the slider is all the way up, all of the incoming

control signal will be allowed to modulate the oscillator. When a fader is all the way down (or all the way

to the left) it is said to be closed. Conversely, when

the slider is set all the way up (or all the way to the

right) it is said to be open.

The left most FM CONTROL jack is normalled to the

keyboard’s control voltage. One can tell that the keyboard control voltage is normalled to this input since

the words “KBD CV” appear in the white box under the input. Since it is keyboard CV that is normalled here, it is usually desirable to have all of the keyboard control voltage modulating the frequency

of the oscillator. Thus, there is no fader above this input, and all of the incoming control signal will

always modulate the oscillator . If a fader was present above this jack, then all of the voltage would not

get to the VCO, and the keyboard would not produce chromatic half steps from one note to the next.

There is some use for this technique, and it will be explored later in this section. Frequency modulation

is the final way that Figure 2-5 below sums up all of the ways VCO-1’s frequency can be changed.

Figure 2-4: VCO-1’s FM jacks

THE KEYBOARD AND REDUNDANT PATCHES

VCO-1

VCO-1’s frequency

is determined by:

• Coarse Tune

• Fine Tune

• Control Voltage

connected to FM

inputs. (This in

cludes the key board CV normal)

Figure 2-5

The control voltage produced by the keyboard is normalled to each oscillator.

When the keyboard is played, it sends out a control voltage for each key, and

the oscillator will change its frequency depending upon how much voltage it

receives from the keyboard. This is a great example of voltage control discussed in Section 1. This is how the synthesizer is able to play different pitches

when different notes are played on the keyboard. The keyboard’s normal to the

oscillator can be broken by inserting a dummy plug into the Keyboard CV jack.

Sometimes people have trouble remembering that the keyboard’ s control voltage is normalled to the oscillators. It is possible to patch the keyboard’ s control

voltage output on the front panel to the keyboard control voltage FM input on

VCO-1, but this is not necessary , since the keyboard control voltage is already

normalled to each oscillator . Creating this patch would just be redoing what the

normal has already accomplished. If a patch is created which duplicates the

effect of a normal, it is called a redundant patch. Patching the keyboard CV

output to the keyboard CV jack on VCO-1 is a perfect example of a redundant

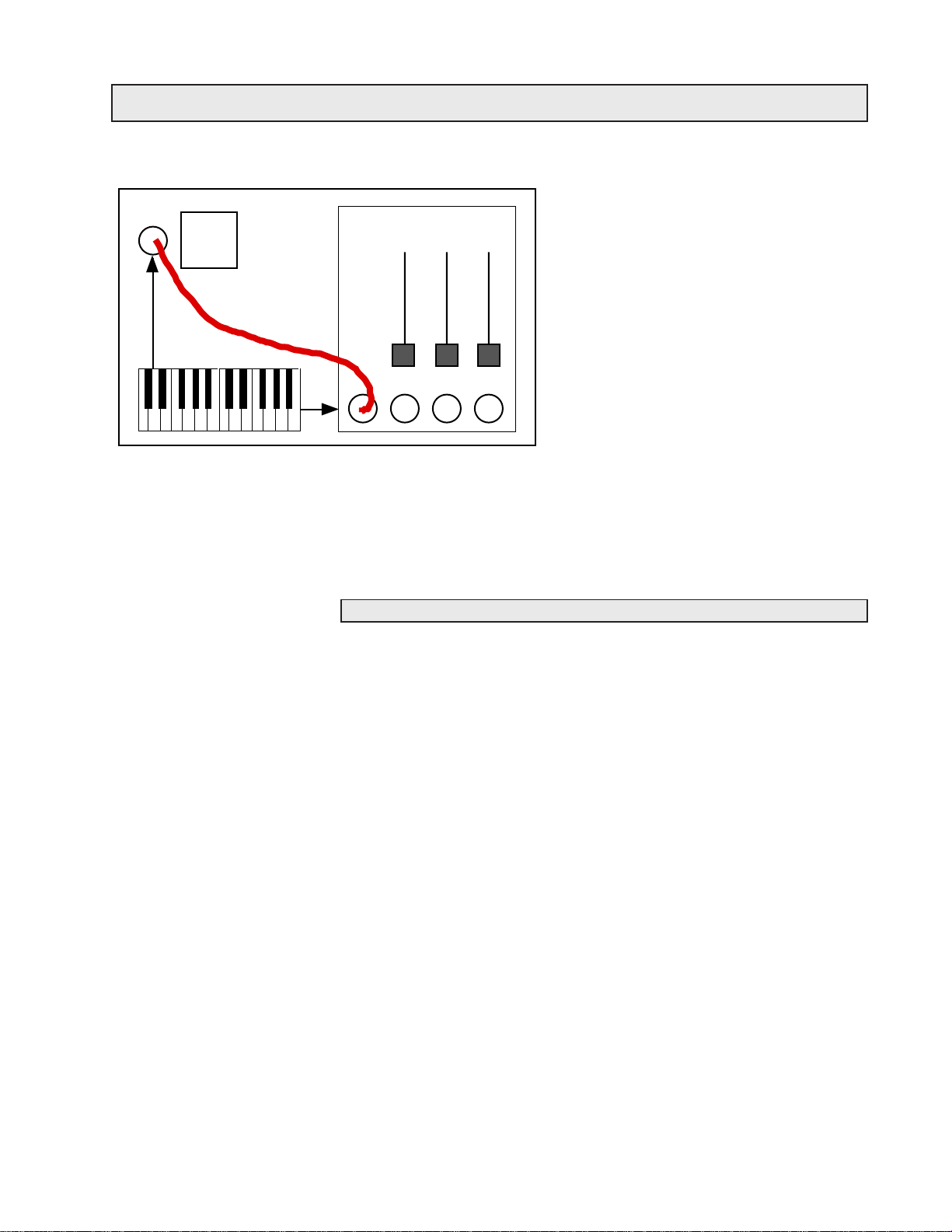

patch. This redundant patch is illustrated in Figure 2-6 on Page 15. (The heavy

red line represents a patch cord.)

Page 30

SECTION TWO: VCO-1 - 015

Redundant patches should be avoided for

KBD

CV

OUTPUT

Figure 2-6: A common redundant patch

sometimes go bad, and cables can pick up hum from other electrical devices and even radio waves.

Redundant patches make troubleshooting a patch much harder since they introduce so many variables.

Normals have a fairly low failure rate, and it is much better to make use of them rather than using patch

cords whenever possible.

VCO-1

FM CONTROL

several reasons. First, they use a patch cord

which could otherwise be used for some

other purpose. At first, it might seem as

though one would never actually use all of

the available patch cords in a studio at once,

but as additional synthesis techniques are discovered, experimenters will want to create

ever more complex patches which will require many patch cords. Secondly , whenever

more cables are used in an electronic music

setup, there is a greater chance for things to

go wrong. Jacks sometimes go bad, cables

LFO’S AND VCO’S

VCO-1 also leads a double life as a low frequency oscillator. By moving the Audio/LF switch (upper

left hand corner of Figure 2-4 on page 14) to the lowest position, VCO-1 will oscillate in the sub-audio