Page 1

AN-581

0.1F

1F

V

S

R2

R1

C1

*STAR GROUND

C

OUT

V

OUT

R

LOAD

VS/2

V

S

/2

R

A

100k

R

B

100k

*

*

V

S

C

IN

V

IN

π ( )

BW1

=

1

2

π 1/2R

ACIN

BW2 =

1

2

π R1 C1

BW3 =

1

2

π R

LOAD COUT

FOR RA = R

B

FOR AC SIGNALS, V

OUT

= VIN (1 + (R2/R1))

WHERE X

C1

<<

R1

*

*

a

APPLICATION NOTE

One Technology Way • P.O. Box 9106 • Norwood, MA 02062-9106 • Tel: 781/329-4700 • Fax: 781/326-8703 • www.analog.com

Biasing and Decoupling Op Amps

in Single Supply Applications

by Charles Kitchin

SINGLE OR DUAL SUPPLY?

Battery-powered op amp applications such as those

found in automotive and marine equipment have only a

single available power source. Other applications, such

as computers, may operate from the ac power lines but

still have only a single polarity power source, such as

5 V or 12 V dc. Therefore, it is often a practical necessity

to power op amp circuits from a single polarity supply.

But single supply operation does have its drawbacks: it

requires additional passive components in each stage

and, if not properly executed, can lead to serious instability problems.

Since a one volt change on the supply line causes a

one-half volt change at the output of the divider, the

circuit’s PSR is only 6 dB. So, the normally high power

supply rejection provided by any modern op amp,

which greatly reduces any ac signals (and power supply hum) from feeding into the op amp via its supply

line, is now gone.

COMMON PROBLEMS WITH RESISTOR BIASING

Single supply applications have inherent problems that

are not usually found in dual supply op amp circuits. The

fundamental problem is that an op amp is a dual supply

device and so some type of biasing, using external components, must be used to center the op amp’s output

voltage at midsupply. This allows the maximum input

and output voltage swing for a given supply voltage.

In some low gain applications, where input signals are

very small, the op amp’s output can be lifted above

ground by only 2 V or 3 V. But in most cases, all clipping

needs to be avoided and so the output needs to be centered around midsupply.

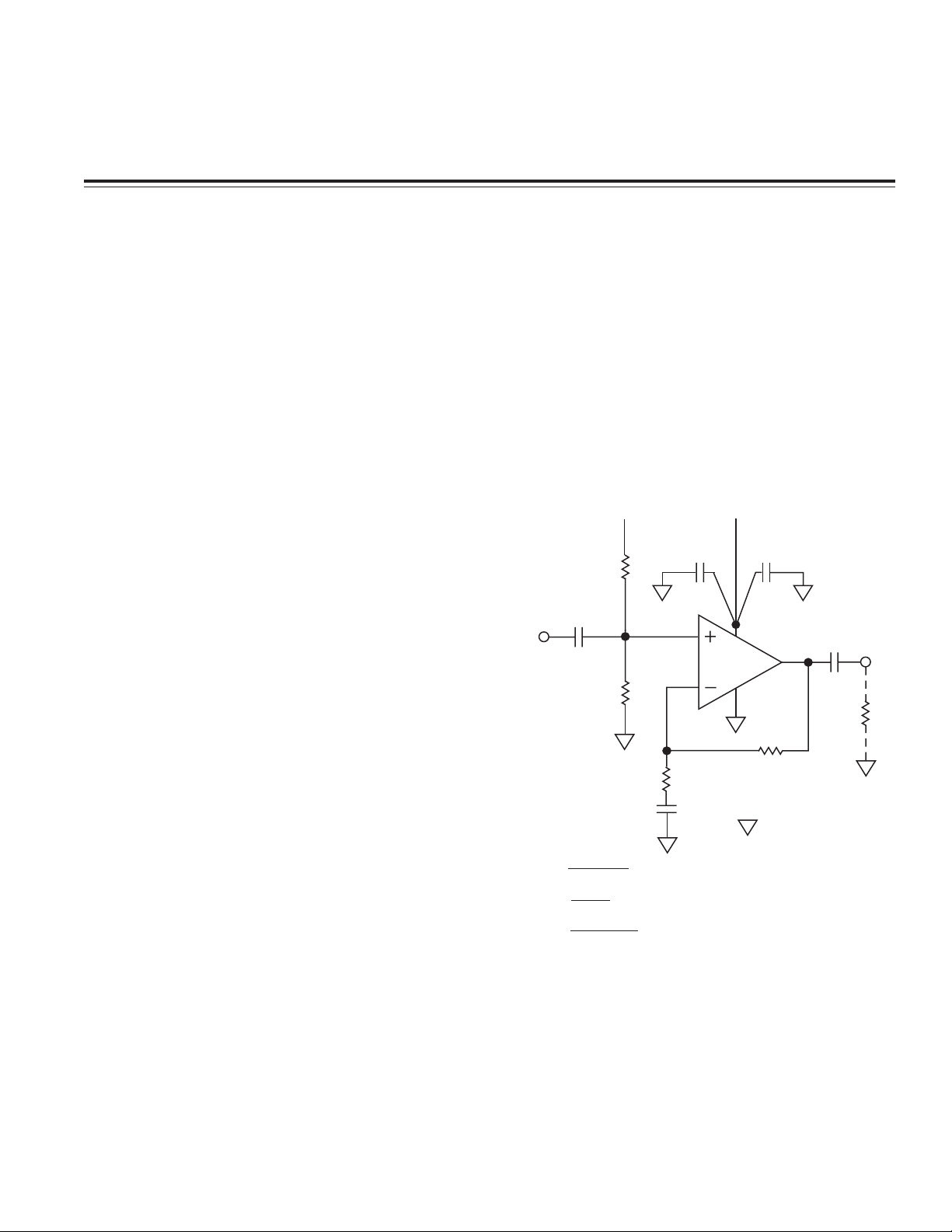

The circuit of Figure 1 shows a simple single supply

biasing method. This noninverting, ac-coupled, amplifier circuit uses a resistor divider with two biasing

resistors, R

ing equal to V

capacitively coupled to the noninverting input terminal.

and RB, to set the voltage on the noninvert-

A

S

/2. As shown, the input signal, VIN, is

This simple circuit has some serious limitations. One is

that the op amp’s power supply rejection is almost entirely

gone, as any change in supply voltage will directly

change the V

Power Supply Rejection (PSR) is a very important (and

frequently overlooked) op amp characteristic.

REV. 0

/2 biasing voltage set by the resistor divider.

S

Figure 1. A Potentially Unstable Single Supply Op

Amp Circuit

© Analog Devices, Inc., 2002

Page 2

AN-581

π

π

π

π

Even worse, instability often occurs in circuits where the

op amp must supply large output currents into a load.

Unless the power supply is well regulated (and well

bypassed), large signal voltages will appear on the supply line. With the op amp’s noninverting input

referenced directly off the supply line, these signals

will be fed directly back into the op amp often initiating

“motor boating” or other forms of instability.

While the use of extremely careful layout, multicapacitor

power supply bypassing, star grounds, and a printed circuit board “power plane,”

may

provide circuit stability,

it is far easier to reintroduce some reasonable amount of

power supply rejection into the design.

DECOUPLING THE BIASING NETWORK FROM THE SUPPLY

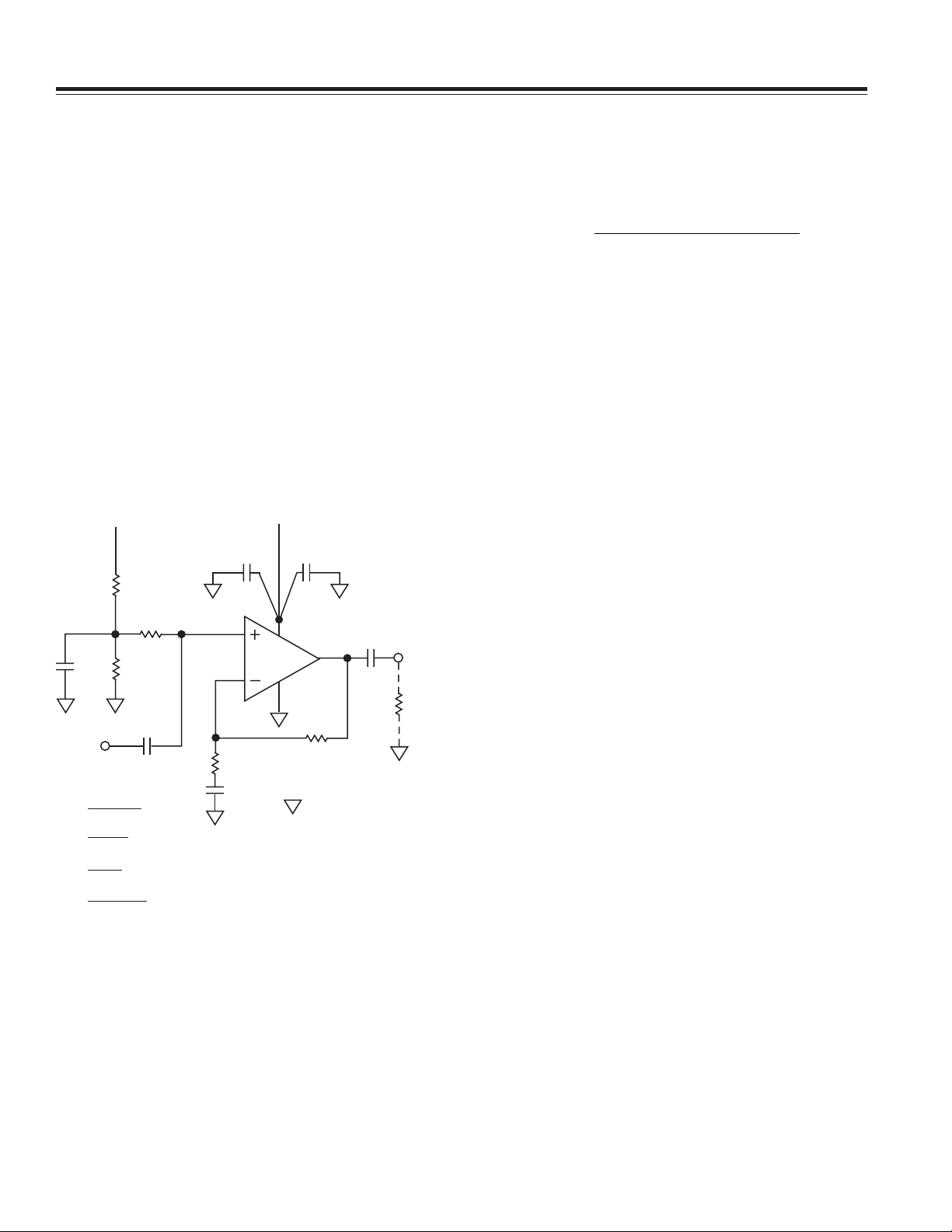

The solution is to modify the circuit, as shown in Figure 2.

The tap point on the voltage divider is now bypassed for

ac signals by capacitor C2, restoring some ac PSR.

Resistor R

provides a dc return path for the VS/2 reference

IN

voltage and also sets the circuit’s (ac) input impedance.

V

0.1F

/2

S

1F

R2

150k

*

*STAR GROUND

*

C

OUT

V

S

R

A

100k

R

IN

100k

+

*

BW1 =

BW2 =

BW3 =

BW4 =

FOR RA = RB AND BW1 = 1/10TH BW2,

BW3, AND BW4

FOR AC SIGNALS, V

WHERE X

TO MINIMIZE INPUT BIAS CURRENT ERRORS,

R2 SHOULD EQUAL R

Figure 2. A Decoupled Single Supply Op Amp Biasing

Circuit

C2

V

2

2

2

2

IN

(1/2RA) C2

1

RIN C

1

R1 C1

R

LOAD COUT

<<R1

C1

1

1

R

B

100k

IN

C

IN

= VIN (1 + (R2/R1))

OUT

(1/2 R

+

IN

*

V

S

VS/2

R1

C1

*

)

A

Many published applications circuits show a 100 kΩ/100 kΩ

voltage divider for R

and RB with a 0.1 µF or similar

A

capacitance value for C2. However, the –3 dB bandwidth

of this network is set by the parallel combination of R

A

and RB and Capacitor C2 and is equal to:

–

3

dB BW

(, )(. )

250000 0 1 10

π

1

–

6

Farads

×

30

Hz=

=

Motor boating or other forms of instability can still occur,

as the circuit has essentially no power supply rejection

for frequencies below 30 Hz. So any signals below 30 Hz

that are present on the supply line, can very easily find

their way back to the + input of the op amp.

A practical solution to this problem is to increase the

value of capacitor C2. It needs to be large enough to

effectively bypass the voltage divider at all frequencies

within the circuit’s passband. A good rule of thumb is to

set this pole at one-tenth the –3 dB input bandwidth, set

by R

IN/CIN

and R1/C1.

Note that the dc circuit gain is unity. Even so, the op

amp’s input bias currents need to be considered. The

R

voltage divider adds considerable resistance in

A/RB

series with the op amp’s positive input terminal, equal

to the parallel combination of the two resistors. Maintaining the op amp’s output close to midsupply requires

“balancing” this resistance by increasing the resistance

in the minus input terminal by an equal amount. Current

V

OUT

R

AD

LO

feedback op amps often have unequal input bias currents, which further complicates the design.

Therefore, designing a single supply op amp circuit

design that considers input bias current errors as well as

power supply rejection, gain, input and output circuit

bandwidth, etc., can become quite involved. However, the

design can be greatly simplified by using a “cookbook”

approach. For a common voltage feedback op amp

operating from a 15 V or 12 V single supply, a resistor

divider using two 100 kΩ resistors is a reasonable compromise between supply current consumption and input

bias current errors. For a 5 V supply, the resistors can be

reduced to a lower value such as 42 kΩ. Finally, some

applications need to operate from the new 3.3 V standard. For 3.3 V applications, it is essential that the op

amp be a “rail-to-rail” device and be biased very close to

midsupply; the biasing resistors can be further reduced

to a value of around 27 kΩ.

–2–

REV. 0

Page 3

AN-581

π (

π

Note that current feedback op amps are typically

designed for high frequency use and a low-pass filter is

formed by R2 and stray circuit capacitance, which can

severely reduce the circuit’s 3 dB bandwidth. Therefore,

current feedback op amps normally need to use a

fairly low resistance value for R2. An op amp such as

the AD811, which was designed for video speed applications, typically will have optimum performance using a

1kW resistor for R2. Therefore, these types of applications

need to use much smaller resistor values in the R

A/RB

voltage divider to minimize input bias current errors.

Instead of a bipolar device, the use of a modern FET

input op amp will greatly reduce any input bias current

errors unless the circuit is required to operate over a

very wide temperature range. In that case, balancing the

resistance in the op amp’s input terminals is still a wise

precaution.

Table I provides typical component values for the circuit

of Figure 2 for several different gains and 3 dB bandwidths.

Table I. Typical Component Values for the Circuit of Figure 2

Where R

= RB = 100 k⍀, RIN = 100 k⍀, and R2 = 150 k⍀

A

Input Output

BW BW C

*R1 C1* C2 C

IN

OUTRLOAD

Gain (Hz) (Hz) (F) (k⍀)(F) (F) (F) (k⍀)

10 10 10 0.3 16.5 1.5 3 0.2 100

20 10 10 0.3 7.87 3 3 0.2 100

10 50 50 0.1 16.5 0.3 0.6 0.05 100

101 20 20 0.2 1.5 6.8 2 0.1 100

*Capacitance values rounded off to next highest common value. Since

the CIN/RIN pole and C1/R1 poles are at the same frequency, and both

affect the input BW, each capacitor is ÷2 larger than it would otherwise

be for a single pole RC-coupled input. C2 is selected to provide a corner

frequency of 1/10th that of the input BW.

+V

S

0.1F

R

A

100k⍀

R

2

2

2π R

R1 C1

B

100k⍀

V

IN

1

1/2 RA) C2

1

1

LOAD COUT

OUT

C2

*

BW1 =

BW2 =

BW3 =

FOR RA = RB AND XC2<<X

FOR AC SIGNALS, V

WHERE XC1<<R1

TO MINIMIZE INPUT BIAS CURRENT ERRORS,

R2

SHOULD EQUAL 1/2 R

*

VS/2

VS/2

R1

C1

= VIN (R2/R1)

.

A

C1

+V

S

1F

R2

*

50k⍀

*STAR GROUND

*

C

OUT

V

OUT

R

LOAD

Figure 3. A Decoupled Single Supply Inverting

Amplifier Circuit

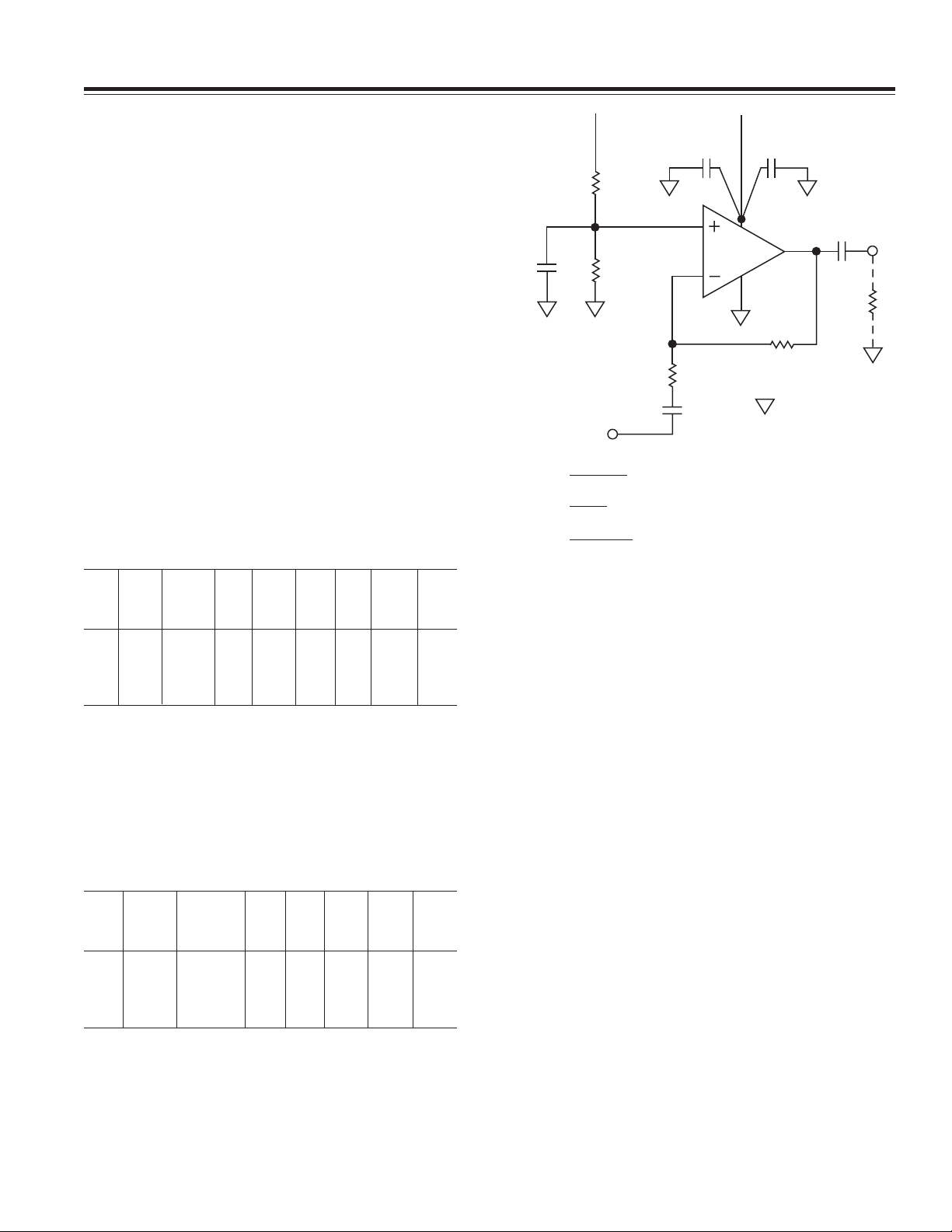

Figure 3 shows a circuit similar to Figure 2, but for an

inverting amplifier.

Table II provides typical component values for several

different gains and 3 dB bandwidths.

Table II. Typical Component Values for the Circuit of Figure 3

Where R2 = 50 k⍀ and R

= RB = 100 k⍀

A

Input Output

BW BW R1 C1* C2* C

OUTRLOAD

Gain (Hz) (Hz) (k⍀)(F) (F) (F) (k⍀)

10 10 10 2 8.2 0.5 0.2 100

20 10 10 1 20 0.5 0.2 100

10 50 50 2 2 0.1 0.05 100

100 20 20 1 8.2 0.3 0.1 100

*Capacitance values rounded off to next highest common value. Since

the C1/R1 pole and C2/RA/RB poles are at the same frequency, and both

affect the input BW, each capacitor is ÷2 larger than it would otherwise

be for a single pole RC-coupled input.

REV. 0

–3–

Page 4

AN-581

π

π

π

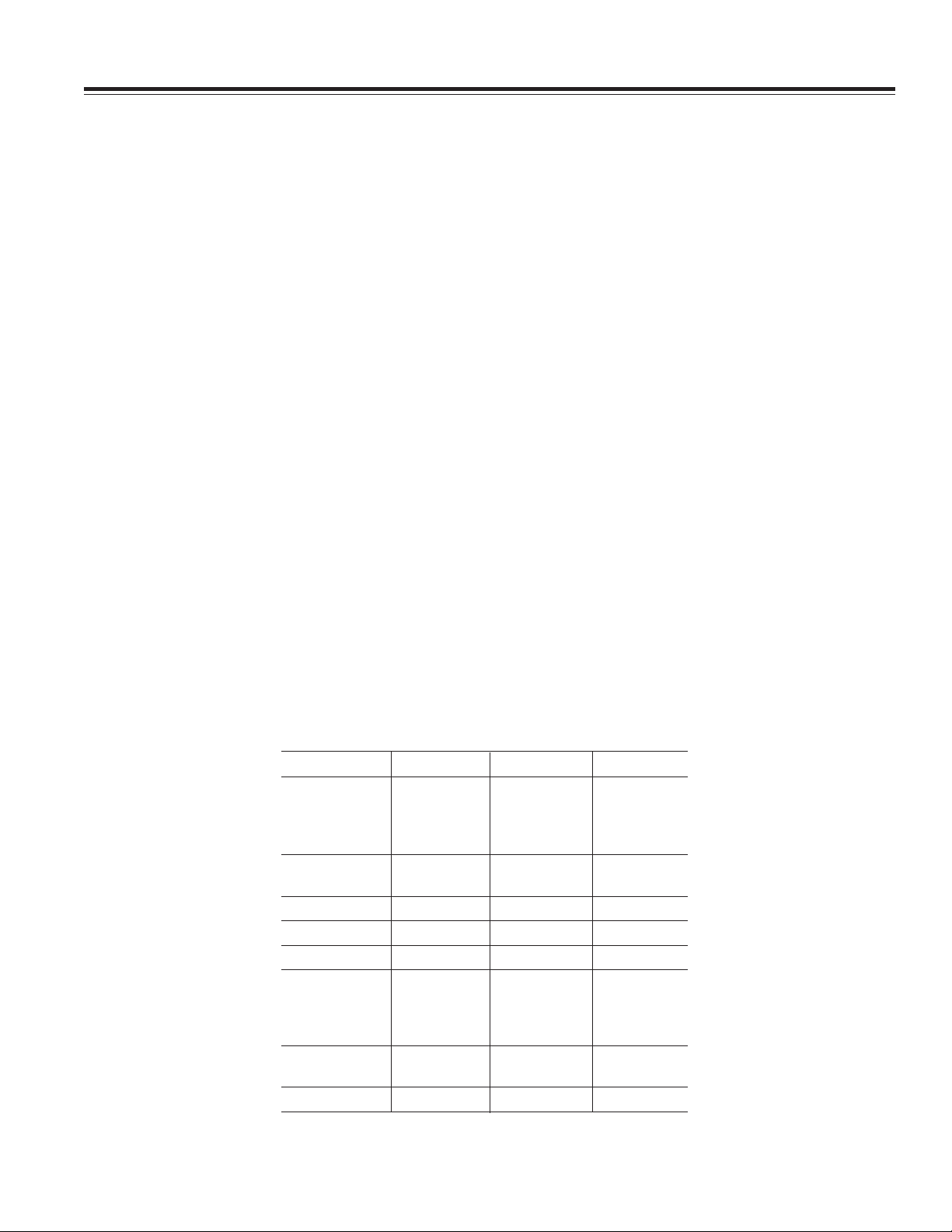

ZENER DIODE BIASING

Although the resistor divider biasing technique is low

cost, and always keeps the op amp’s output voltage at

V

/2, the op amp’s common-mode rejection is entirely

S

dependent upon the R

time constant formed by RA/R

C

and capacitor C2. Using a C2 value that provides at least

10 times the R

network (R1/C1 and R

time constant of the input RC coupling

C

) will help ensure a reasonable

IN/CIN

common-mode rejection ratio. With 100 kΩ resistors for

R

and RB, practical values of C2 can be kept fairly small

A

as long as the circuit bandwidth is not too low. However,

another way to provide the necessary V

/2 biasing for

S

single supply operation is to use a Zener diode regulator.

Just such a scheme is shown in Figure 4. Here, current

flows through resistor R

to the Zener. Capacitor C

Z

helps prevent any Zener-generated noise from feeding

into the op amp. Low noise circuits may need to use a

larger value for C

V

IN

I

Z

V

S

R

Z

than the 10 µF specified.

N

V

S

0.1F

C

IN

R

IN

100k

+

C

10F

*

V

Z

V

Z

N

*

1F

V

100k

*

C

OUT

V

Z

Z

R2

V

R

OUT

LOAD

A Zener should be chosen that has an operating voltage

close to V

/2. Resistor RZ needs to be selected to provide

S

a high enough Zener current to operate the Zener at its

stable rated voltage and to keep the Zener output noise

B

low. It is also important to minimize power consumption

(and heating) and to prolong the life of the Zener. As the

op amp’s input current is essentially zero, it’s a good

idea to choose a low power Zener. A 250 mW device is best

but the more common 500 mW types are also acceptable.

The ideal Zener current varies with each manufacturer

but practical I

levels between 5 mA (250 mW Zener) and

Z

5 µA (500 mW Zener) are usually a good compromise for

this application.

N

Within the operating limits of the Zener, the circuit of

Figure 4 basically restores the op amp’s power supply

rejection. But this does not come without a price: the op

amp’s output is now at the Zener voltage rather than at

V

/2. If the power supply voltage drops, nonsymmetrical

S

clipping can occur on large signals. Furthermore, the circuit now consumes more power. Finally, input bias

currents still need to be considered. Resistors R

and R2

IN

should be close to the same value to prevent input bias

currents from creating a large offset voltage error.

Figure 5 is an inverting amplifier circuit using the same

Zener biasing method.

R1

C1

*STAR GROUND

SELECT RZ TO PROVIDE THE DESIRED

ZENER OPERATING CURRENT, I

+V

– V

S

ZENER

=

R

Z

I

Z

1

BW1 =

2

RIN C

IN

1

BW2 =

2

R1 C1

2

1

R

LOAD COUT

OUT

BW3 =

FOR AC SIGNALS, V

WHERE XC1<<R1

TO MINIMIZE INPUT BIAS CURRENT ERRORS,

R2 SHOULD EQUAL RIN.

SEE TEXT.

.

Z

= VIN (1 + (R2/R1))

*

Figure 4. A Noninverting Single Supply Amplifier Using

Zener Diode Biasing

–4–

REV. 0

Page 5

π

π

π

V

S

0.1F

R

I

Z

V

S

R

Z

ZENER

IN

100k

10 F

C2

*

V

Z

V

Z

+

*

V

IN

R1

C1

*

1F

R2

100k

*

C

OUT

V

Z

R

*STAR GROUND

SELECT RZ TO PROVIDE THE DESIRED

ZENER OPERATING CURRENT, I

– V

+V

S

ZENER

=

R

Z

I

Z

2

2

2

R1 C1

RIN C2

R

1

1

1

LOAD COUT

OUT

IN

BW1 =

BW2 =

BW3 =

FOR AC SIGNALS, V

WHERE XC1<<R1

TO MINIMIZE INPUT BIAS CURRENT ERRORS,

R2 SHOULD EQUAL R

.

Z

= VIN (R2/R1)

.

SEE TEXT.

Figure 5. An Inverting Single Supply Amplifier Using

Zener Diode Biasing

V

OUT

LOAD

AN-581

Table III can be used with circuits 4 and 5 to provide

practical R

Zener diodes. Note that for the lowest possible circuit

noise, the optimum Zener current should be selected by

referring to the Zener product data sheet.

Table III. Recommended RZ Values and Motorola Zener

Diode Part Numbers for Use with Figures 4 and 5

Supply Zener Zener R

Voltage Voltage Zener Current Value

(V) (V) Type (IZ)()

+15 7.5 1N4100 500 µA 15 k

+15 7.5 1N4693 5 mA 1.5 k

+12 6.2 1N4627 500 µA 11.5 k

+12 6.2 1N4691 5 mA 1.15 k

+9 4.3 1N4623 500 µA 9.31 k

+9 4.3 1N4687 5 mA 931

+5 2.4 1N4617 500 µA 5.23 k

+5 2.7 1N4682 5 mA 464

Tables IV and V provide practical component values

for Figures 4 and 5 for several different circuit gains

and bandwidths.

Table IV. Typical Component Values for the Circuit of

Figure 4 Where R

from Table III

Gain (Hz) (Hz) (F) (k)(F) (F) (k)

10 10 10 0.3 11.0 2 0.2 100

20 10 10 0.3 5.23 4.7 0.2 100

10 50 50 0.1 11.0 0.47 0.05 100

101 20 20 0.2 1.0 15 0.1 100

*Capacitance values rounded off to next highest common value. Since

the CIN/RIN pole and C1/R1 poles are at the same frequency, and both

affect the input BW, each capacitor is √2 larger than it would otherwise

be for a single pole RC-coupled input.

resistor values for use with some common

Z

= R2 = 100 k and CN = 0.1 F. Select R

IN

Input Output

BW BW C

*R1 C1* C

IN

Z

Z

OUTRLOAD

Table V. Typical Component Values for the Circuit of

Figure 5 Where R

= R2 = 100 k. Select RZ from Table III

IN

Input Output

BW BW R1 C1* C2* C

OUTRLOAD

Gain (Hz) (Hz) (k)(F) (F) (F) (k)

10 10 10 10 2.7 0.2 0.2 100

20 10 10 5 4.7 0.2 0.2 100

10 50 50 10 0.5 0.05 0.05 100

100 20 20 1 12 0.1 0.1 100

*Capacitance values rounded off to next highest common value. Since

the C1/R1 pole and C2/RIN poles are at the same frequency, and both

affect the input BW, each capacitor is √2 larger than it would otherwise

be for a single pole RC-coupled input.

REV. 0

–5–

Page 6

AN-581

0.1F

1F

*

*

*STAR GROUND

VS/2

+V

S

–V

S

VS/2

*

*

R

A

220k

C2

0.1F

R

B

220k

+

110k

0.1

F

1F

*

0.1F

OP AMP BIASING USING A LINEAR VOLTAGE REGULATOR

For op amp circuits operating from the new 3.3 V standard,

a 1.65 V biasing voltage is needed. Zener diodes are

commonly available only down to 2.4 V. The easiest way

to provide this biasing voltage is to use a linear voltage

regulator, such as the ADM663A or ADM666A devices.

This is shown in Figure 6.

V

S

V

IN

SENSE

V

(2)

GND

OUT

V

SET

1.3V T O 16V

ADJUSTABLE

OUTPUT

V

IN

REF

C1

R

A

R

B

*

R1

ADM663A

ADM666A

Figure 6. An Op Amp Single Supply Biasing Circuit Using

A Linear Voltage Regulator

Although a Zener diode is usually the cheapest voltage

regulator available, a linear voltage regulator has lower

drift over temperature than a Zener and far less noise.

Resistors R

V

/2 voltage reference; consult AD663A datasheet.

S

and RB are selected to provide the desired

A

DC-COUPLED BATTERY-POWERED CIRCUITS

So far, only ac-coupled op amp circuits have been

discussed. Although with the use of suitably large input

and output coupling capacitors, an ac-coupled circuit can

operate at frequencies well below 1 Hz, some applications

require a true dc response.

Battery-powered applications permit the use of a “phantom ground” circuit as shown in Figure 7. This provides

dual supply voltages, both positive and negative with respect to ground, from a single battery. An op amp is

used to buffer the output of a V

low voltage battery such as 3.3 V is used, the op amp

should be a “rail-to-rail” device and able to operate

effectively from this supply voltage. The op amp also

needs to be able to supply an output current large

enough to power the load circuit. Capacitor C2 bypasses

the voltage divider output enough to prevent any resistor

noise from feeding into the op amp. This capacitor does

not need to provide power supply rejection because the

load current flows directly to ground and so any signal

currents flow equally from both sides of the battery.

Resistors R

V

S

and RB are selected to provide the desired

A

/2 voltage reference; consult AD663A datasheet.

V

S

0.1F1F

*

VS/2

/2

V

S

/2 voltage divider. If a

S

*

*

R2

*STAR GROUND

C

OUT

V

OUT

R

LOAD

Figure 7. Using an Op Amp to Provide a “Phantom

Ground” for Battery-Powered DC-Coupled Applications

NOISE ISSUES

Some op amp applications need a low noise amplifier

and low noise amplifier circuits require low resistance

values in the signal path. Johnson (resistor) noise

equals 4 nV times the square root of the resistance

value in kΩ. While the Johnson noise of a 1 kΩ resistor

is only 4 nV/√Hz, this increases to 18 nV/√Hz for a 20 kΩ

resistor and 40 nV/√Hz for a 100 kΩ resistor. Even though

the R

resistor divider is bypassed to ground with a

A/RB

capacitor (C2), these resistors set a limit on the minimum value that can be used for the op amp’s feedback

resistor and, the larger this is, the greater the Johnson

noise. So low noise applications need to use much

smaller op amp biasing resistor values than the 100 kΩ

specified here. However, lower value resistors in the

divider mean higher power supply current and reduced

battery life.

Fortunately, the Zener diode biasing method supplies

V

/2 without the need for large resistors. As long as the

S

Zener is bypassed to keep its noise out of the circuit,

both noise and supply current can be kept low. The use

of a linear voltage regulator is even better, as its noise

and output impedance are both very low.

–6–

REV. 0

Page 7

AN-581

CIRCUIT TURN-ON TIME ISSUES

One final issue that needs to be considered is circuit

turn-on time. The approximate turn-on time will equal

the R

time constant of the lowest BW filter being used.

C

The circuits shown here all call for the RA/RB, C2 voltage

divider network to have a 10 times longer time constant

than that of the input or output circuit. This is to simplify

the circuit design (since up to three different R

poles set

C

the input BW). This long time constant also helps keep

the biasing network from “turning on” before the op

amp’s input and output networks and, therefore, the op

amp’s output gradually climbs from zero volts to V

/2

S

without “railing” to the positive supply line. The value

supplied by this table is for a 3 dB corner frequency that

is 1/10th that of R1/C1 and R

LOAD/COUT

. For example: in

Figure 2, for a circuit BW of 10 Hz and a gain of 10, Table

I recommends a C2 value of 3 µF, which provides a 3 dB

bandwidth of 1 Hz.

Fifty thousand ohms (the parallel combination of R

R

) times 3 microFarads equals an RC time constant of 0.15

B

and

A

seconds. So the op amp’s output will take 0.15 seconds

(approximately) to settle to V

/2. The input and output R

S

networks will charge up ten times faster.

In some applications, where the circuit’s –3 dB low

frequency bandwidth is very low, the circuit turn-on

time may become excessively long. In that case, a

Zener biasing method may be a better choice.

INPUT “HEADROOM” CONSIDERATIONS

Some specialty op amps are designed for low voltage

operation. When these are operated from a low voltage,

single supply, such as 5 V or 3.3 V, input headroom limitations may be introduced. This can happen if the

amplifier’s input stage does not limit symmetrically.

For example: the AD8061 op amp is designed to have an

input common-mode voltage range that extends all the

way down to “ground” (or the negative supply line).

However, its inputs can only swing to within 1.8 V of the

positive supply voltage without introducing dc errors or

limiting device bandwidth. So, if this amplifier is operated from a single 5V supply and the amplifier’s positive

input is biased at V

/2 (2.5 V), the input voltage can

S

swing in the negative direction a full 2.5 V (down to zero

volts). But, in the positive direction, it can only swing 1 V

before clipping.

Note that this is not a problem if the amplifier is being

operated at a gain of 2.5 or higher, as the maximum output swing (± 2.5 V) will be reached before the input stage

limits. However, if the amplifier is being operated at a

C

lower gain, the positive input needs to be biased below

V

/2, to allow symmetrical input stage limiting. In the

S

case of the AD8061, biasing the positive input at 1.5 V

will allow a 3 V p-p input swing without clipping. Refer

to the individual product data sheet to determine the

optimum single supply biasing voltage.

Table VI. Rail-to-Rail Op Amps Recommended for New Designs

Type Single Dual Quad

High Speed AD8031 AD8032

AD8061 AD8062

AD8051 AD8052 AD8054

AD8063 AD823

High Output AD8591 AD8592 AD8594

AD8531 AD8532 AD8534

JFET Input AD820 AD822 AD824

Auto Zero AD8551 AD8552 AD8554

Digital Trim AD8601 AD8602 AD8604

Low Noise OP184 OP284 OP484

OP162 OP262 OP462

AD8605 AD8606 AD8608

AD8628

Low Power OP196 OP296 OP496

AD8541 AD8542 AD8544

Precision OP777 OP727 OP747

REV. 0

–7–

Page 8

E02493–0–10/02(0)

–8–

PRINTED IN U.S.A.

Loading...

Loading...