AMT Datasouth PAL User Manual

AMT Datasouth Fastmark

TM

PAL

Print and Program

Language Reference Guide

P/N 108744 Rev. A1

Copyright 2003 by AMT Datasouth Corporation.

All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any

form or by any means without the written permission of the publisher.

P

UBLISHED BY

AMT Datasouth

4216 Stuart Andrew Boulevard

Charlotte, North Carolina 28217

Phone: 704.523-8500

Service 800.476.2450

Sales: 800.476.2120

Internet: www.amtdatasouth.com

Revised 4 December, 2003.

PAL is a trademark of AMT Datasouth Corporation.

All other brand and product names are trademarks or registered trademarks of their

respective companies.

Contents

1. Introduction.................................................................1

2. PAL Fundamentals......................................................3

2.1. The PAL Interpreter.........................................................................................3

2.2. Sending Data to PAL Printers..........................................................................3

2.3. PAL Objects.....................................................................................................3

2.4. Interpreter Operation.........................................................................................4

2.5. Operand Stack..................................................................................................4

2.6. Post-Fix Notation.............................................................................................5

2.7. systemdict, globaldict, userdict........................................................................6

2.8. Dictionary Stack...............................................................................................6

2.9. Virtual Memory................................................................................................7

2.10. Transformation Matrix...................................................................................8

3. Objects........................................................................11

3.1. Simple Objects...............................................................................................11

3.1.1. Integer Objects.......................................................................................................11

3.1.2. Fixed-Point Objects...............................................................................................11

3.1.3. Boolean Objects.....................................................................................................12

3.1.4. String Objects ........................................................................................................12

3.1.5. Name Objects.........................................................................................................13

3.1.6. Mark Objects .........................................................................................................15

3.1.7. Null Objects...........................................................................................................15

3.2. Composite Objects.........................................................................................15

3.2.1. Array Objects.........................................................................................................15

3.2.2. Dictionary Objects.................................................................................................17

3.2.3. Procedure Objects..................................................................................................17

vi PAL Print and Program Language Reference

3.3. Internal Objects..............................................................................................18

3.3.1. Intrinsic Operator Objects......................................................................................18

3.3.2. File Objects............................................................................................................19

3.3.3. Font Objects...........................................................................................................19

4. Operators ...................................................................21

4.1. Alphabetical Summary...................................................................................22

A. Bar Code Considerations ........................................199

Precision Bar Code Control.................................................................................199

Bar Code Parameter Defaults...............................................................................200

Determining the Width of Bar Code Bit Maps....................................................200

B. Document Revisions........

2000.06.12..............................................................Error! Bookmark not defined.

1994.08.26..............................................................Error! Bookmark not defined.

1993.10.01..............................................................Error! Bookmark not defined.

1993.04.09..............................................................Error! Bookmark not defined.

1993.04.03..............................................................Error! Bookmark not defined.

1993.03.19..............................................................Error! Bookmark not defined.

Error! Bookmark not defined.

1. Introduction

Welcome to the world of the PAL™ Print and Program Language. Since PAL™ is both a

powerful printing language and programming language, many print applications not previously

possible are now within reach.

Now you don’t have to get a different software-specific printer for every application in your

facility. AMT Datasouth PAL™ enabled printers such as the Fastmark™ line can translate, filter,

interpret and understand almost any data stream. You can now replace obsolete devices with costeffective, high-print-quality thermal printers -- with no expensive software changes.

Here is a brief overview:

!

Quick, high-resolution printing of labels, tags and more

!

Features PAL™ (no host/PC software reprogramming required!)

!

Works for all departments, regardless of what software they’re using

!

Can be run even when the system is down (label format is stored in printer)

!

Offers plug and play convenience

!

Barcodes can be added to existing print jobs without changing host/PC software

How does PAL™ enable you to print your current data stream—without reprogramming

your system?

As documented in this manual, PAL™ is no t only a powerful print ing language, it is also a fully

functional programming language. Utilizing this manual, powerful PAL™ programs may be

written and loaded in the printer to perform a variety of tasks such as interpreting legacy data

steams. Or we can prepare a PAL program for each of your applications and pre-load it into your

PAL™ enabled printer such as Fastmark™ at the factory. These programs enable the PAL™

enabled printer to print labels by filling in the variable fields using your current data stream. This

data stream could have been intended for a laser, dot matrix, ink jet or embossing printer. And, you

don’t have to worry about the software driver in the host, because the formatting is all done within

the printer.

PAL™ enabled printers such as Fastmark are packed with features and options such as:

!

Parallel and serial ports

!

Optional Ethernet, Twinax, Coaxial and USB communication

!

Extensive on-board complement of linear and 2-D symbology barcodes

!

Smooth scalable fonts

!

Expandable memory options

!

Flash memory drives for storing PAL™ programs and other data.

!

Optional external keyboard for stand-alone applications

!

SRAM and Flash memory cards

!

Optional real-time clock (RTC) with Flash memory

!

Optional Peel and Present with label taken sensor

!

Optional Cutters

!

Rugged cabinet c onstruction

All PAL™ enabled products include the latest in Windows™ drivers.

To learn more about how the PAL™ Print and Pro gram Language can be used to quickly

and cost effectively integrate PAL™ enabled printers such as Fastmark™ into your facility,

call AMT Datasouth at 800-215-9192.

2. PAL Fundamentals

2.1. The PAL Interpreter

Every PAL printer contains a copy of the PAL interpreter. The PAL interpreter is the software

inside the PAL printer which the printer's internal computer executes. Although the PAL

interpreter serves a different purpose, it is essentially an application program just like any word

processing or spreadsheet application program run on a general purpose computer.

2.2. Sending Data to PAL Printers

Word processing and speadsheet applications usually accept their data from a user sitting at a

keyboard. The PAL interpreter usually accepts its data from a host computer via the printer's

electrical interface with the host computer. Word processors and spreadsheets can also accept data

from other sources like files located on the user's disk drive. The PAL interpreter can also accept

data from other sources like memory cards plugged into the printer.

The data supplied to the PAL interpreter consists of a series of human readable characters. The

PAL interpreter does not require any special control characters which only computers can

understand.

2.3. PAL Objects

When a host computer sends data to a PAL printer, the PAL interpreter software inside the printer

receives the data and analyzes it. First, the interpreter groups the series of characters into

individual objects. Each object represents a single piece of data for the interpreter. Therefore, the

interpreter views the data it receives as a series of data objects.

The interpreter separates the series of characters into objects by looking for one or more spaces or

other special character. PAL recognizes the following characters as being the same as a space.

PAL refers to all of these characters as whitespace characters.

Character ASCII

Code

Space SP 040 20

Tab HT 011 09

Carriage Return CR 015 0D

New Line / Line Feed LF 012 0A

Null NUL 000 00

Form Feed FF 014 0C

Octal

Value

Hexadecimal

Value

4 PAL Language Reference

PAL requires the user to separate each object with at least one of the preceeding whitespace

characters, or one of the following special characters.

Character Description

( Left/Open Parenthesis 050 28

) Right/Close Parenthesis 051 29

< Left/Open Angle Bracket or Less Than 074 3C

> Right/Close Angle Bracket or Greater Than 076 3E

[ Left/Open Square Bracket 133 5B

] Right/Close Square Bracket 135 5D

{ Left/Open Brace 173 7B

} Right/Close Brace 175 7D

/ Forward Slash 057 2F

% Percent 045 25

The special characters listed above each have a special meaning for PAL. The user should only use

one or more of these characters to separate objects when the user also wishes PAL to perform the

action associated with the character.

2.4. Interpreter Operation

Normally the PAL interpreter performs a function in response to each object received. For data

objects, PAL usually just stores the object within the printer's memory. Executable objects instruct

PAL to perform some operation. The operation usually involves one or more of the data objects

previously received.

Octal

Code

Hexadecimal

Code

The interpreter immediately performs the appropriate function for each object upon receipt of the

object. However, PAL does not consider an object fully received until it receives the separation

character which follows the object. Therefore, if the host computer sends the printer a command

without following the command with a space or other separation character, the printer will not

respond to the command until it receives the separation character. Until PAL receives the

separation character, PAL cannot know for sure whether or not it has received all the characters of

the object.

2.5. Operand Stack

As PAL receives data objects from the host, it pushes the objects onto an internal structure known

as the operand stack. PAL places each successive object on top of the previous object on this stack

of objects. As long as the interpreter continues to receive data objects, it will continue pushing the

objects onto this stack.

When PAL receives an object which indicates some action for the interpreter to perform, the action

will usually involve zero or more data objects know as operands or parameters. For example, a div

(divide) operation requires two operands — the divisor and the dividend. In order to perform the

operation, PAL pops the top two operands off the operand stack. It then divides one operand by

the other operand in order to calculate the quotient. PAL then pushes the quotient onto the operand

stack.

2.6. Post-Fix Notation

PAL receives data objects and operation objects in an order known as post-fix notation. This

means that the data upon which an operator will operate occurs before the operato r itself. This

differs from the algebraic notation which everyone learned in school.

In school, algebraic equations looked like the following.

( 1 + 2 ) × ( 4 + 5 )

In post-fix notation, this same equation has the following format.

1 2 + 4 5 + ×

Post-fix notation has the advantage that it does not require parethesis or other special symbols to

override operator precedence. The preceding algebraic equation required parenthesis it order to

give the addition operations precedence over the multipication operation. In post-fix notation, the

operators have no implied precedence. The left-most operation occurs first, and the right-most

operator occurs last. Therefore, both the computer and human need only perform the equation from

left to right as written.

In order to perform very complex equations, both algebraic and post-fix notation rely upon an operand stack. When humans perform complex algebraic calculations manually, they imitate an operand stack using a piece of scratch paper. When using an algebraic calculator, the calculator

contains an internal operand stack. The "(" and ")" keys on the calculator instruct the calculator to

perform push and pop operations. As the equations above show, an algebraic calculation would

require 12 key presses, not including the final "=" key, on a calculator.

PAL Fundamentals 5

Hewlett-Packard calculators have been based on reverse polish notation (or "RPN" for short) for

years. Reverse polish notation operates the same as post-fix notation. The post-fix notation equation shown above also shows seven of the nine key strokes necessary to perfor m the calculation

using a Hewlett-Packard RPN calculator. The equation does not show the necessary "enter" key

press following the 1 and 4.

Although not as familiar to us as algebra ic no tatio n, p o st-fix nota tion a ctually pr ovid es a fa ster and

more straight-forward approach to performing calculations.

PAL performs all of its operations using post-fix notation. As PAL encounters data objects, it

automatically pushes the objects onto the operand stack. When PAL encounters an object which

indicates an action to perform, PAL pops any necessary operands from the operand stack, performs

the action, and pushes any results onto the operand stack. In PAL, the preceding equation would

appear as the following sequence of PAL objects.

1 2 add 4 5 add mul

When PAL encounters the data object "1," it pushes the object onto the operand stack. PAL

performs the same action for the data object "2." PAL then encounters the operator "add." In

response, the interpreter pops the "2" and the "1" off the stack and adds them together. This produces the result data object "3," which PAL pushes onto the stack.

Next PAL encounters the data objects "4" and "5," which it pushes onto the stack. Then PAL

encounters the operator "

resulting "9". Finally, PAL encounters the "

add

," so PAL pops the "4" and "5," adds them together, and pushes the

mul

" operator. In response, PAL pops the "9" from the

6 PAL Language Reference

second "

"27," onto the operand stack.

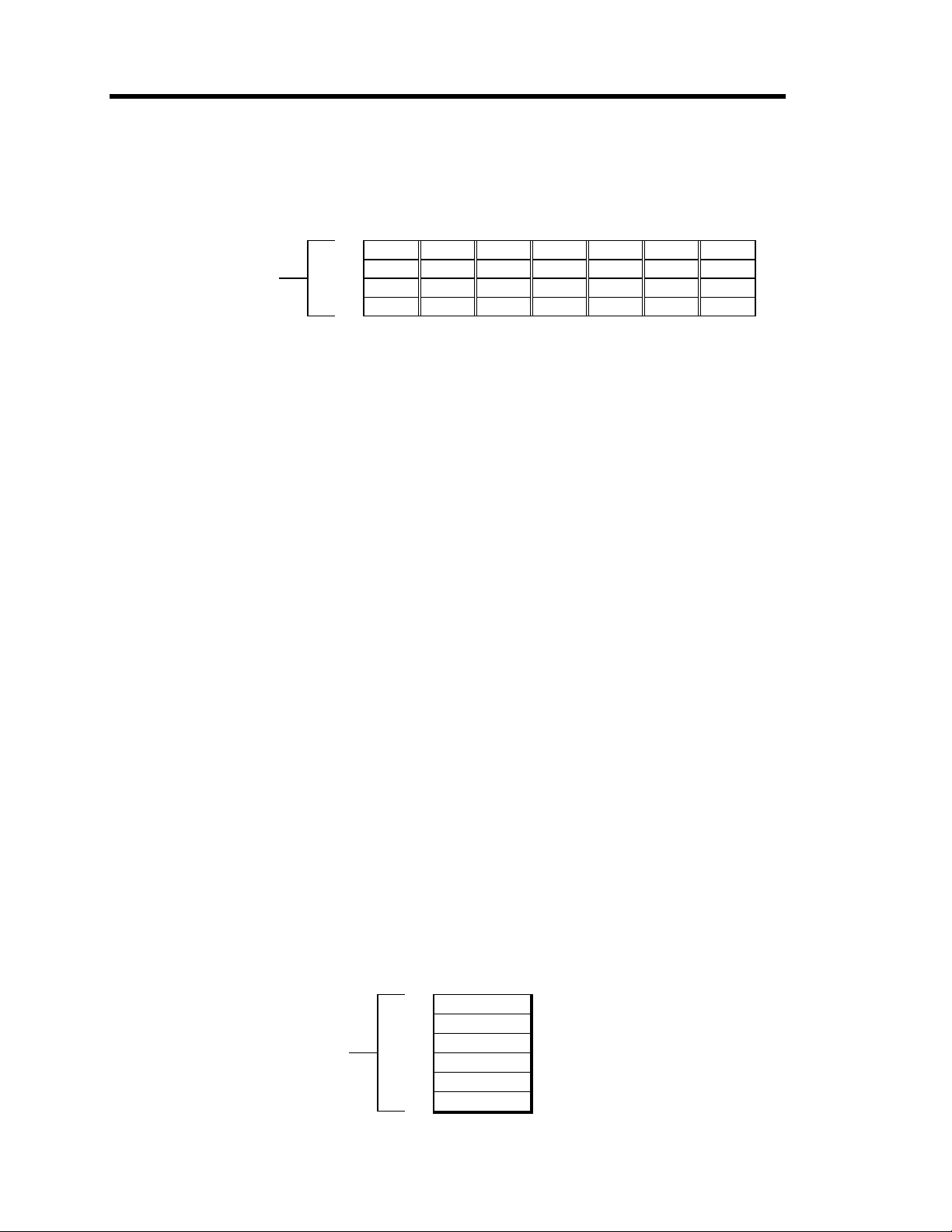

The following diagram shows the contents of the operand stack when PAL finishes processing

each object in the above sequence.

add

" and the "3" from the first add and multiplies them together. It then pushes the result,

1 2 add 4 5 add mul

Stack 5

2 449

11333329

2.7. systemdict, globaldict, userdict

PAL supports a data structure called a dictionary. Dictionaries contain an arbitrary collection of

objects organized into pairs. PAL treats the first object of each pair as the key object, and the

second object as the value object. This organization allows PAL to search a dictionary for a

particular key object, and recover the value object associated with the key.

When the PAL interpreter initializes, it automatically creates three dictionaries to help it keep track

of the various objects a PAL programmer will store into the printer's memory. PAL gives these

dictionaries the names systemdict, globaldict, and userdict.

Initially, userdict and globaldict do not contain any objects. systemdict contains all the names

which PAL recognizes as operators, as well as other predefined names like

true, false

, and

mark

.

The operator names themselves do not actually instruct the PAL interpreter to perform an operation. Instead, PAL has a special internal object type known as an intrinsic operator object.

When the PAL interpreter encounters one of these intrinsic operator objects, the interpreter

performs the action indicated by the object.

systemdict contains all the operator names as key objects. It also contains all the intrinsic operator

objects as value objects associated with the appropriate name objects. Therefore, when PAL

receives an executable name object from the host computer, PAL searches

dictionary key entry which matches the name object.

When PAL locates the matching name, the interpreter then recovers the value object associated

with the name. For the operator names, PAL will find an intrinsic operator object associated with

the name. The PAL interpreter then performs the action indicated by the intrinsic operator object.

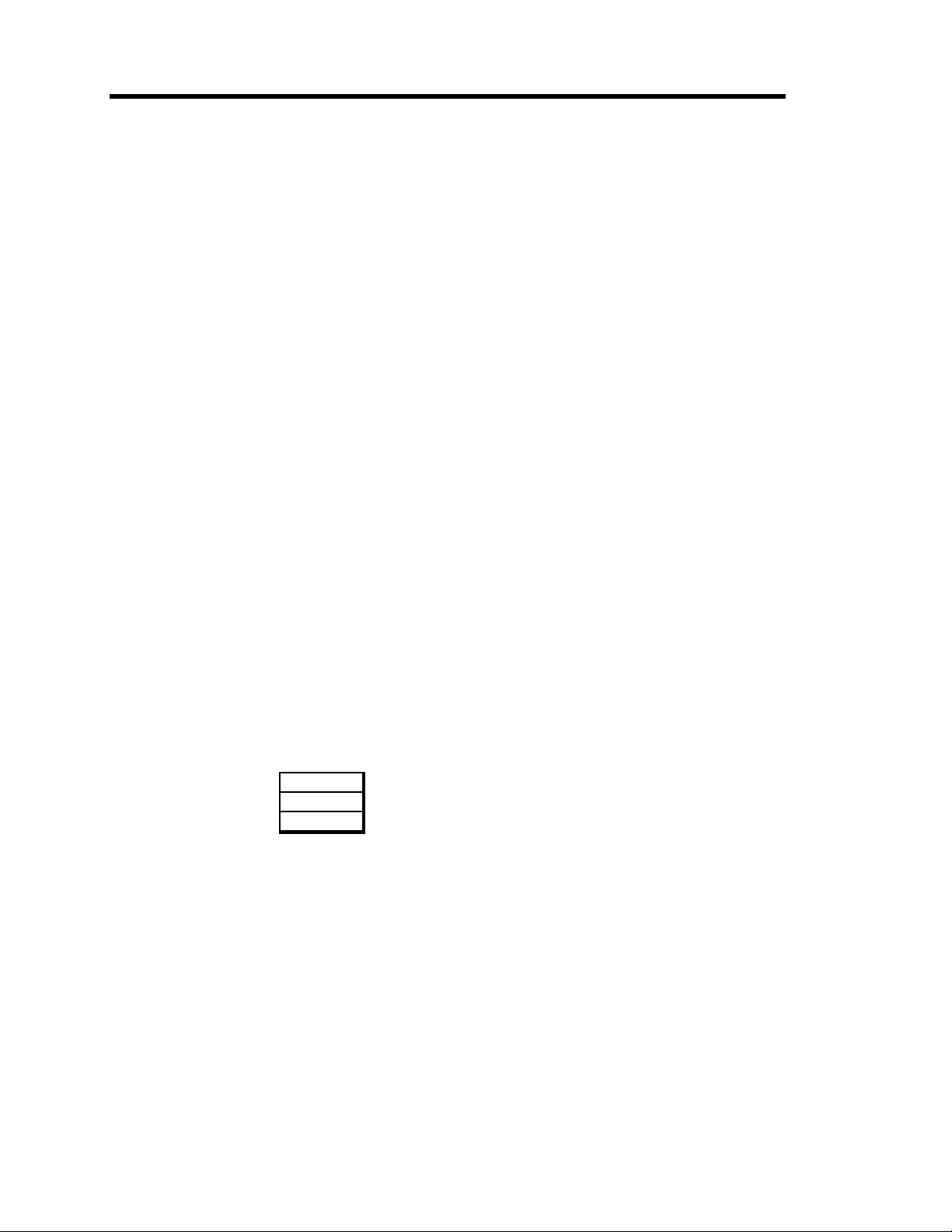

2.8. Dictionary Stack

During initialization, PAL pushes the three standard dictionaries, systemdict, globaldict, and

userdict onto an internal structure known as the dictionary stack. Therefore, immediately after

initialization, the dictionary stack contains the following.

Dictionary Stack

userdict

globaldict

systemdict

systemdict

to find a

PAL Fundamentals 7

When PAL encounters an executable name, PAL goes to the dictionary stack to find out what to

do. PAL starts by trying to locate the name in the top-most dictionary on the dictionary stack. If it

cannot find the name, it then tries the next dictionary down on the stack. PAL continues down the

stack until it locates the name. Once PAL locates the name, it stops searching.

Since PAL stops searching when it locates the name, any entries for a given name in a dictionary

on the top of the dictionary stack will supercede an entry in a dictionary on the bottom of the stack.

As the above diagram shows,

Therefore, any entry for a name in any other dictionary on the dictionary stack will have

precedence over the entry for that name in systemdict.

As a result, the programmer has the freedom to redefine any of the names which PAL has

predefined for performing the various PAL operations. However, redefining PAL operators only

serves to make a PAL order sequence difficult for another programmer to understand.

The dictionary stack also serves a more important purpose. It allows the PAL programmer to

define new names to which the PAL interpreter will automatically respond. The programmer can

add a new name with an associated value object to one of the dictionaries on the dictionary stack.

Later, when PAL encounters the name, it will search the dictionary stack and find the

programmer's entry.

If the programmer associates a procedure object with the name, PAL will automatically execute the

procedure. If the programmer associations an integer, string, or other data object with the name,

PAL will automatically push the data object onto the operand stack.

systemdict

resides on the very bottom on the dictionary stack.

The programmer may not alter the contents of systemdict. However, PAL automatically provides

the programmer with the two dictionaries

add and delete entries from these dictionaries. During initialization, PAL creates userdict and

globaldict as empty dictionaries.

PAL also provide operators which allow the programmer to push new dictionaries onto the

dictionary stack and later pop them off the stack. This allows the programmer to collect localized

definitions into separate dictionaries and then discard all the definitions by simply popping the

dictionaries from the dictionary stack.

Although PAL allows the p rogrammer to add and d elete entries within

PAL does not allow the programmer to remove the three standard d ictionaries themselves from the

dictionary stack.

2.9. Virtual Memory

The interpreter keeps all user data objects as well as the various interpreter data structures within

the virtual memory area. PAL refers to this memory area as virtual memory because the programmer does not have direct access to this memory.

PAL dynamically manages this space for the programmer. As the programmer sends objects to the

PAL interpreter, the interpreter automatically allocates space for the objects within the virtual

memory area. When the programmer no longer requires a particular object, PAL automatically

frees the object's memory for use by other objects.

userdict

, and

globaldict

. Th e progr ammer may f reely

userdict

and

globaldict

,

PAL will keep an object within virtual memory for as long as the programmer maintains a reference to the object. Once the programmer eliminates all references to the object, PAL automatically removes the object from memory .

8 PAL Language Reference

The programmer still has references to a given object so long as the programmer still has some

means of acessing the object. For example, object A may contain the only reference anywhere in

memory to the object B. In turn, the object B may contain the only reference anywhere in memory

to the object C. And the operand stack may contain the only reference to object A.

So long as a reference remains anywhere in memory to the object A, PAL will keep all of these

objects in the virtual memory. However, if the programmer pops the reference to object A from the

operand stack without creating an alternate reference to the object, the programmer will have

eliminated all references to object A. As a result, PAL will eliminate object A from memory.

When PAL eliminates object A from memory, it also eliminates the only reference to object B.

Therefore, PAL also eliminates object B from memory. This results in the elimination of the only

reference to object C, so PAL eliminates it from memory as well.

The amount of virtual memory available to the programmer varies between PAL printer models. In

can also vary between two different printers with the same amount of internal memory. This

variance results from the amount of memory the PAL interpreter requires in order to manage the

various options on different printer models.

PAL provides the vmstatus operato r to allow the programmer to determine the amount of virtual

memory available on a given printer model. The operator also provides information relating to the

amount of virtual memory already allocated for PAL objects and other data.

2.10. Transformation Matrix

All printers provide some form of coordinate system. The coordinate system provides the basis for

the user to instruct the printer where to locate a particular character or other image on the page.

Many non-PAL printers base their coordinate system on the printer's dots-per-inch or dots-permillimeter resolution.

This works fine so long as the host computer programmer must only control that particular printer

model. However, if the programmer must also control other printers which use different

resolutions, then the same control sequences will not work in all cases, even if all printers use the

same basic control language.

PAL's device independent coordinate system allows the host programmer to use the same control

sequence for all PAL printers. This includes PAL printers with different resolutions as well as from

different printer manufacturers.

In addition to providing a device independent coordinate system, PAL allows the programmer to

define this coordinate system to meet the needs of the programmer. By default, PAL uses a

typesetters' unit of measure known as a point. No precise definition of a point exists, however

typesetters generally use values close to 1/72 of an inch. Most computer software, including PAL,

use exactly 1/72 of an inch as the definition of a point.

PAL realizes that a point may not suit every programmer's requirements. Therefore, PAL provides

operators which allow the programmer to alter the current coordinate system. The programmer can

freely scale, rotate, and relocate the origin of the user coordinate system.

In order to convert the user's coordinates to dots on a printed page, PAL maintains an internal

mathematical construct known as a transformation matrix. The transformation matrix contains six

values which PAL changes whenever the user alters the coordinate system. In mathematics, a

PAL Fundamentals 9

transformation matrix also includes three additional constant values. However, since the extra

values do not change, PAL does not need to keep the values as part of the matrix.

The following diagram shows the mathematical representation of a transformation matrix.

AB0

CD0

EF1

Special mathematical rule s exist for changing the values A through F in r esponse to scaling, rotating, and relocating the origin (translating) of a coordinate system. However, once PAL has

updated the six values to reflect any changes to the user's coordinate system, PAL simply uses

these values in the following formulas to convert the user's coordinates to actual dot positions on a

printed page.

X' = AX + CY + E

Y' = BX + DY + F

X and Y represent a coordinate in the user's coordinate system. X' and Y' represent the same coordinate on a printer page.

PAL uses the term current transformation matrix to indicate the transformation matrix currently in

use by PAL. PAL automatically initializes the current transformation matrix to the values

necessary to convert the PAL default coordinate system (points) to the physical page coordinate

system (dots).

The discussions within this manual of the various PAL operators which affect the current

transformation matrix describe the various ways in which the programmer may alter the matrix.

3. Objects

PAL allows programmers to store various different types of data into the printer's memory. PAL

uses the term object to refer to each different piece of data stored within the printer's memory.

Each object has a type. An object's type indicates how PAL will interact with that particular object.

The PAL language gr oups the various object t ypes into two cl assifications — simple and composite. In addition, PAL includes a classification of object types internally used by PAL. This

manual discusses each object type under its appropriate classification.

3.1. Simple Objects

Simple objects represent the basic types of data which the programmer can store within the printer.

This differs from composite objects which group together collections of simple objects as well as

other composite objects. The simple object classification includes the following types:

Integer

Fixed-Point

Boolean

String

Name

Mark

Null

3.1.1. Integer Objects

PAL allows integer objects to have numerical values between -999,999,999 and +999,999,999,

inclusive. Integer objects cannot have any fractional digits. In order words, an integer object cannot have the value 1.5.

When the programmer includes an integer value as part of a PAL sequence, the value can include

only the digits 0 thr ough 9 with an optio nal leading pl us (+) or minus (-) si gn. If the programmer

does not specify a plus or minus sign, PAL assume a positive value. Integer values may not include

a decimal point even if the programmer places only zeros to the right of the decimal point. The

value also may not include commas or other punctuation.

The following PAL sequence specifies three integer objects for the PAL interpreter.

-45 +36 999

3.1.2. Fixed-Point Objects

PAL allows fixed-point objects to have numerical values between -999,999,999.999,999,999 and

+999,999,999.999,999,999, inclusive. This means that fixed-point objects may have nine digits to

the left of the decimal point, and another nine digits to the right of the decimal point.

PAL differs from many other progr amming languages in its use of fixe d-point values. Most other

programmer languages use floating-point values. Floating-point values usually allow the

programmer to specify a small number of significant digits, but the digits may have almost any

relationship to the decimal point. For example, many programming languages allow around six

12 PAL Language Reference

significant digits for their floating-point values. However, these six digits can represent the value 1

trillion (1,000,000,000,000) or 1 trillionth (0.000,000,000,001).

Floating-point values work very well in scientific applications. For example, specifying the distance to a star or the size of an atom. However, they do not work very well in business applications. Business applications tend to require a smaller range of values, but many more significant

digits. Few companies have the need to calculate their worth in the billions. And those companies

which do can afford super computers to count their money for them.

However, many companies require calculations in the tens of millions or less, with every digit

being significant. Floating-point values generally cannot keep track of sufficient digits to satisfy

this requirement. Therefore, PAL relies upon large fixed-point numbers instead of more conventional floating-point values.

When the programmer includes a fixed-point value as part of a PAL sequence, the value must have

a particular format. The value may start with an optional plus (+) or minus (-) sign. If the

programmer does not include a plus or minus sign, PAL will assume a positive value. The value

must also have a digit, 0 through 9, both before and after a decimal point. When PAL sees the

decimal point, PAL knows to treat the value as a fixed-point value rather than an integer value.

The value may not include commas or other punctuation. If the programmer does not include a

digit both before and after the decimal point, PAL will treat the value as a name object rather than

a fixed-point object. For example, PAL treats "1." and ".1" as name objects. The programmer must

specify "1.0" or "0.1" in order for PAL to treat the objects as fixed-point numbers.

3.1.3. Boolean Objects

Boolean objects can only have the value true or false. PAL usually creates boolean objects in

response to performing some test. For example, if the programmer instructs PAL to test two

integers for equality, PAL will create a boolean object which indicates the result of the test. If PAL

finds the integers equal, PAL will create a boolean object with the value true. If PAL does not find

the integers equal, PAL will create a boolean object with the value false.

PAL also includes definitions for the names true and false. The name true corresponds with a

boolean object having the value true. The name

the value false.

3.1.4. String Objects

Strings consists of a variable length collection of bytes. In simple applications, each byte usually

represents a printable character. A string can contain from zero to 30,000 bytes.

Since each string object can have a variable number of bytes associated with it, PAL stores the

string object and the collection of bytes (the string value) in separate parts of memory. The string

object contains only a reference to the string value.

When the programmer instructs PAL to perform an operation which causes PAL to duplicate a

string object, PAL only duplicates the object part of the string. PAL does not duplicate the value

portion of the string. As a result, the duplication creates two objects which both refer to the same

collection of bytes. Special operators exist which allow the programmer to instruct PAL to also

duplicate the value portion of the string.

false

corresponds with a boolean object having

Objects 13

In many cases, the programmer will not wish PAL to duplicate the value portion. Duplicating only

the object portion of the string does not consume very much of the printer's memory. On the other

hand, duplicating the value portion of a large string will consume a large amount of the printer's

memory.

Octal

Value

(hello)

" specifies a string

Hexadecimal

Value

PAL accepts strings as text enclosed in parenthesis. For example, "

consisting of the characters "h," "e," "l," "l," and "o."

PAL also allows the programmer to include parenthesis as part of the string. Strings containing

balanced pairs of parenthesis do not require any special treatment. For example, PAL also accepts

"(ab(cd)ef)" as a perfectly valid string. In this case, the string contains eight characters —

"ab(cd)ef."

If the string contains unbalanced parenthesis, then the programmer should place the special backslash (\) character in front of each parenthesis. The programmer may also use a back-slash even

when the string contains ba lanced p arenthe sis. A computer pro gram which generat es the strings to

send to a PAL printer would normally just place a back-slash in front of every parenthesis.

Therefore, the programmer could also specify the preceeding string as "(ab\(cd\)ef."

In order to include the back-slash as part of a string, the programmer need only specify two backslashes. For example, specifying "(The back-slash character \(\\\) is a prefix!)" creates the

string "The back-slash character (\) is a prefix!"

The following table list all the special characters which the programmer can place into strings

using the back-slash character.

PAL

Code Description

\n New Line LF 012 0A

\r Carriage Return CR 015 0D

\t Tab HT 011 09

\b Backspace BS 010 08

\f Form-Feed FF 014 0C

\\ Back-Slash \ 134 5C

\( Left (Open) Parenthesis ( 050 28

\) Right (Close) Parenthesis ) 051 29

\

ddd

Character for Octal Code

ddd any ddd

ASCII

Symbol

3.1.5. Name Objects

Just like strings, names consist of a variable length collection of bytes. In simple applications, each

byte usually represents a printable character. A name can contain from one to 30,000 bytes.

Since each name can have a variable number of bytes associated with it, PAL stores a name object

in exactly the same manner as it stores string objects. In fact, PAL treats name objects and string

objects in an almost identical manner.

Each name objects has one of three different attributes — executable, literal, or immediate

evaluation. The programmer specifies which attribute the name object should have by placing

zero, one, or two forward slashes (/) immediately in front of the name.

If the programmer does not place any forward slash in front of the name, PAL treats the name as

executable. For example, PAL will treat the character sequence "MyName" as an executable

name. Provided PAL does not encounter the name while creating a procedure, PAL will try to find

14 PAL Language Reference

an object or an operation associated with the name. If PAL encounters the name while creating a

procedure, PAL does not execute the name at that time. PAL simply stores the name as part of the

procedure. PAL will execute the name later when the programmer instructs PAL to execute the

procedure.

If the programmer places a single forward slash in front of the name, PAL treats the name as

literal. For example, PAL will treat the character sequence "

means that PAL will simply create a name object in a manner similar to a string object.

If the programmer places two forward slashes in front of the name, PAL immediately evaluates the

name. For example, PAL will treat the character sequence "//MyName" as an immediately

evaluated name. When PAL evaluates, as opposed to executes, a name, PAL simply replaces the

name with the object associated with the name. PAL does not attempt to execute the object

associated with the name.

Except during a procedure definition, the difference between executable and immediately evaluated only matters for names associated with procedures or PAL intrinsic operators. In all other

case, executable and immediately evaluated names produce the same results.

During a procedure definition, PAL simply records executable names as part of the procedure. It

does not attempt to execute the name at that time. However, PAL still substitutes immediately

evaluated names with their associated objects even during procedure definitions.

/MyName

" as a literal name. This

Using an immediately evaluated name during a procedure definition can produce entirely different

results from using an executable name. For example, the programmer has associated the name

FirstProc with a procedure object. The programmer then defines a second procedure,

SecondProc

If the programmer specifies

will simply record the executable name FirstProc within SecondProc's definition. Later, when

the programmer instruct PAL to execute SecondProc, PAL will also execute the procedure

associated with the name

If the programmer changes the procedure associated with FirstProc between executions of

SecondProc

executes

time SecondProc was defined. In fact, PAL will not care whether the programmer has associated

any procedure with FirstProc before d efining SecondProc. PAL only cares about the procedure

associated with

If the programmer specifies FirstProc as an immediately evaluated name (//FirstProc) within the

definition of

associated with FirstProc. This means that PAL will place the procedure object associated with

FirstProc directly within the definition of SecondProc.

PAL will insert the procedure object and not the instructions contained within the procedure

object. This will have the same effect as having used the "{" and "}" operators to define the procedure directly within

SecondProc,

automatically try to execute the instructions contained within the procedure object.

, which includes a reference to

FirstProc

FirstProc

, PAL will always execute the procedure associated with

SecondProc

SecondProc

PAL will simply push the procedure object onto the o perand stack. PAL will not

. It will not matter which procedure was associated with

FirstProc

's at the time PAL encounters

, PAL will immediately substitute

SecondProc

when it encounters the executable name.

. When PAL encounters the procedure object while executing

FirstProc

as an executable name (no "/" in front of the name), PAL

.

FirstProc

FirstProc

when executing

//FirstProc

with the current object

at the time PAL

FirstProc

SecondProc

at the

.

Names can include almost any combination of characters, numbers, and special symbols. However,

names do not have special enclosing characters like the parenthesis required by strings. This means

that names cannot include the special characters which PAL uses for other purposes. Specifically,

names cannot include any of the following object separator characters.

( ) < > [ ] { } / %

Also, a name cannot satisfy the rules for an integer or fixed-point object. Otherwise, PAL will treat

the name as an integer or fixed-point object. Therefore, PAL accepts "1+" as a name, but "+1" as

an integer object. Likewise, PAL accepts ".1" and "1." as names, but "0.1" and "1.0" as fixedpoint objects.

3.1.6. Mark Objects

A mark object do es not have a value. It o nly has the type mark. Mark objects serve a special purpose under PAL. Several PAL operators manipulate all objects pushed onto the operand stack

above a mark object. PAL has predefined the name mark and has associated the name with a mark

object.

3.1.7. Null Objects

PAL uses null objects as place holders. For example, when the programmer instructs PAL to create

an array object, PAL fills the array object with null objects. The null objects act as place holders

until the programmer replaces them with other objects.

Objects 15

3.2. Composite Objects

In addition to simple objects, PAL supports three types of composite objects — arrays, dictionaries, and procedures.

Composite objects group together collections of other objects. A composite object may contain any

combination of simple objects as well as other composite objects. One composite object may

contain numerous othe r composite objects, which in turn co ntain numerous other composite ob jects, which in turn contain numerous other composite objects. PAL does not impose any limitation

on the complexity of combinations which the programmer can create.

3.2.1. Array Objects

Array objects simply contain a list o f other objects. Unlike most other programming languages,

array objects may contain any combination of object types. For example, an array might contain a

couple integer objects, four other array objects, six dictionary objects, three string objects, four

name objects, and six procedure objects.

PAL provides three operations for creating array objects. The first operator,

containing all null objects. This allows the programmer to create an array and place the data into it

at a future time. The PAL sequence "

The other two PAL operators, "[" and "]," work as a team to create an array containing a desired

collection of objects. The first operator of the pair, "[," starts the array definition. The "[" operator

does nothing more than place a mark object onto the operand stack. In fact, PAL does not care

whether the programmer uses the "[" operator or the predefined name

object onto the stack. However, using the "[" operator makes PAL sequences much easier for

humans to read.

24 array

" creates an array containing 24

mark

array

, creates an array

null

objects.

to place the mark

16 PAL Language Reference

Unlike most other p rogra mming languages, PAL do es not tr eat the "[" and "]" operators as special

language syntax symbols. PAL does not treat the operato rs and data i t encounters be tween the "["

and "]" operator any different than if it had not encountered the "[" operator. In fact, once PAL

places the mark object onto the stack in response to the "[" operator, PAL totally forgets that it

ever saw the "[" operator.

PAL creates the array object in response to encountering the "]" operator. PAL creates the array

from all the objects located on the operand stack above the top-most mark object. Normally, the

top-most mark object will result from the previous "[" operator.

Therefore, the programmer need only push all the objects for the array onto the operand stack

following the mark object pushed by the "[" operator. PAL does not care how the programmer

pushes the objects onto the stack. In the most simple case, the programmer may simply list all the

objects. PAL will push the objects onto the stack as part of PAL's normal duties. In a more

complex case, the programmer may execute any combination of procedures and PAL operators to

generate the data for the array.

For example, the following simple PAL sequence creates an array containing the integer object

123

, the string object "

[123 (hello) /MyName]

PAL treats this sequence in a very straight-forward manner. When PAL encounters the "["

operator, it pushes a mark object onto the operand stack. PAL then encounters the integer object

"123" and pushes it onto the stack. Next PAL encounters the string object "(hello)" and pushes it

onto the stack. After the string, PAL encounters the literal name object " /MyName" and pushes it

onto the stack.

hello

," and the literal name object "

MyName

."

Finally, PAL encounters the "]" operator. This instructs PAL to create an array object from all of

the objects on the stack above the top-most mark object. As a result, PAL creates an array

containing the integer, string, and name objects. PAL then removes the objects, as well as the mark

object, from the operand stack and places the array object onto the stack.

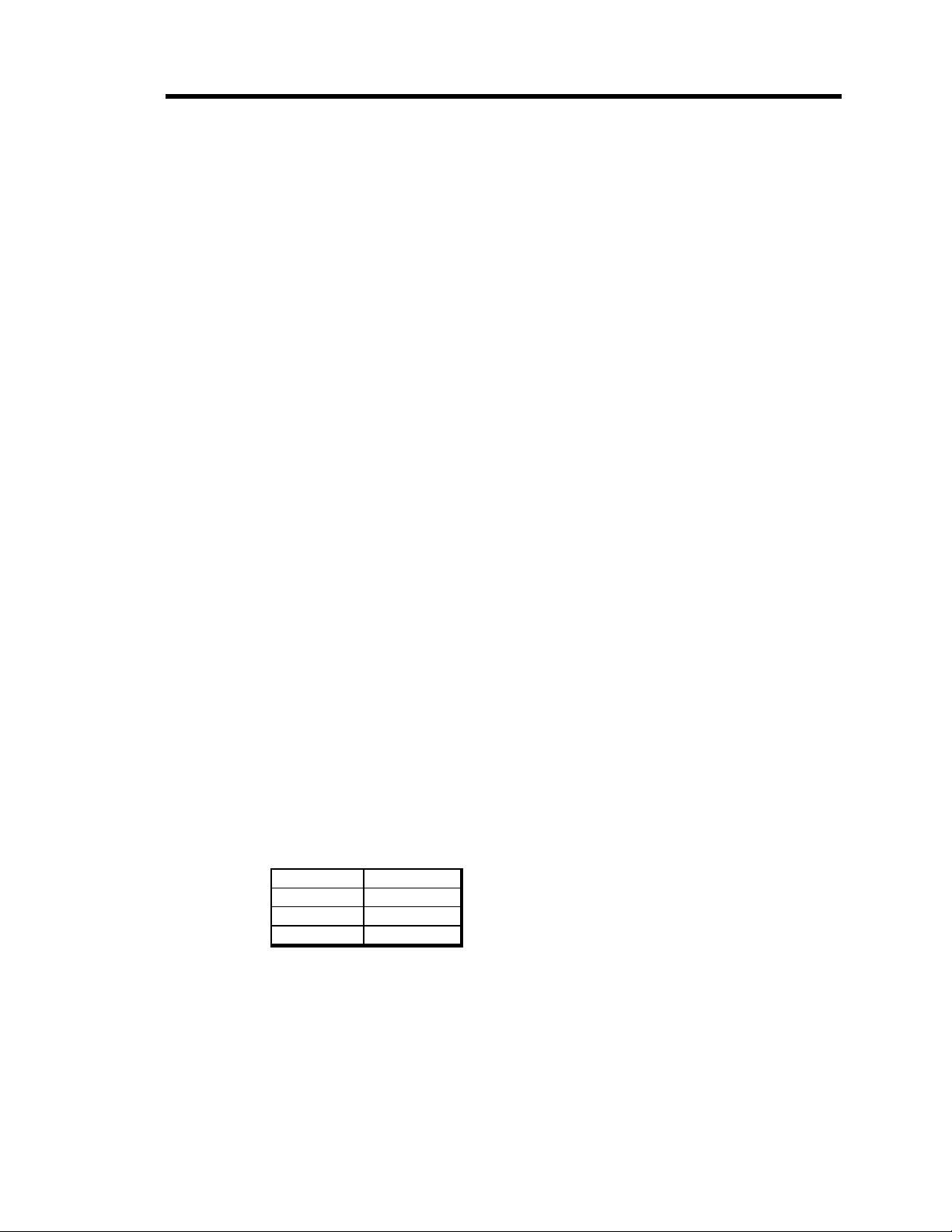

The following diagram shows the organization of the above array within the printer's memory.

Index Object

0

1

2

Like string and name objects, array objects actually consist of two parts — the object part and the

value part. The array object itself contains only a reference to the array data (value). Therefore,

when the programmer instructs PAL to duplicate an array object, PAL only creates a new reference

to the array data. PAL does not duplicate the data itself. This conserves memory and allows the

programmer to manipulate the array data in various ways.

The programmer may access the individual objects within the array by specifying the index of the

object. The first object in the array has an index of zero, the next object has an index of one, with

the indexes continuing through N-1, where N represents the number of objects in the array.

Therefore, an array has the following general appearance.

[obj0 obj1 obj2 obj3 ... objN-1]

123

(hello)

/MyName

3.2.2. Dictionary Objects

The programmer creates dictionary objects in the exact same manner as arrays. Except, dictionary

objects use the "<<" and ">>" operators. The "<<" operator serves the exact same purpose as the

"[" operator and mark predefined name. When PAL encounters the "<<" operator, PAL simply

pushes a mark object onto the stack.

Later, when PAL encounters the ">>" operator, PAL builds a dictionary object from all the objects

on the stack above the top-most mark object. Between the "<<" and ">>" operators, the

programmer may perform any combination of operations necessary to place the desired dictionary

data onto the stack.

PAL organizes the entries within a dictionary into pairs. PAL treats the first object of each pair as a

key, and the second object as the value associated with the key. Therefore, the programmer must

always specify an even number of objects when creating an array.

When pushing dictionary objects onto the operand stack when creating a dictionary, the programmer must first push the key object of each pair followed by the value object. Therefore, a

dictionary has the following general appearance.

<<key0 value0 key1 value1 key2 value2 key3 value3 ... keyN-1 valueN-1>>

Objects 17

Dictionaries allow the programmer to access a particular value object by specifying the key object

associated with the value. This provides a very powerful mechanism for organizing data.

Like array objects, PAL allows dictionary objects to contain any arbitrary combination of object

types. Although PAL all ows key obj ect s of any type, PAL c an searc h a di ctio nary fo r numeric and

name key objects more effeciently than any other type of object. Therefore, the programmer should

seriously consider using only numeric or name objects as key entries within a dictionary.

In order to take advantage of the more efficient name object searching, PAL automatically

converts string objects specified as keys to name objects. PAL does not convert string objects

specified as value entries within a dictionary. As a result, the following two dictionary definitions

result in exactly the same dictionary within the printer's memory.

<<123 (1stValue) /2ndKey /2ndData 45.76 /3rdData (4thKey) 95.11>>

<<123 (1stValue) /2ndKey /2ndData 45.76 /3rdData /4thKey 95.11>>

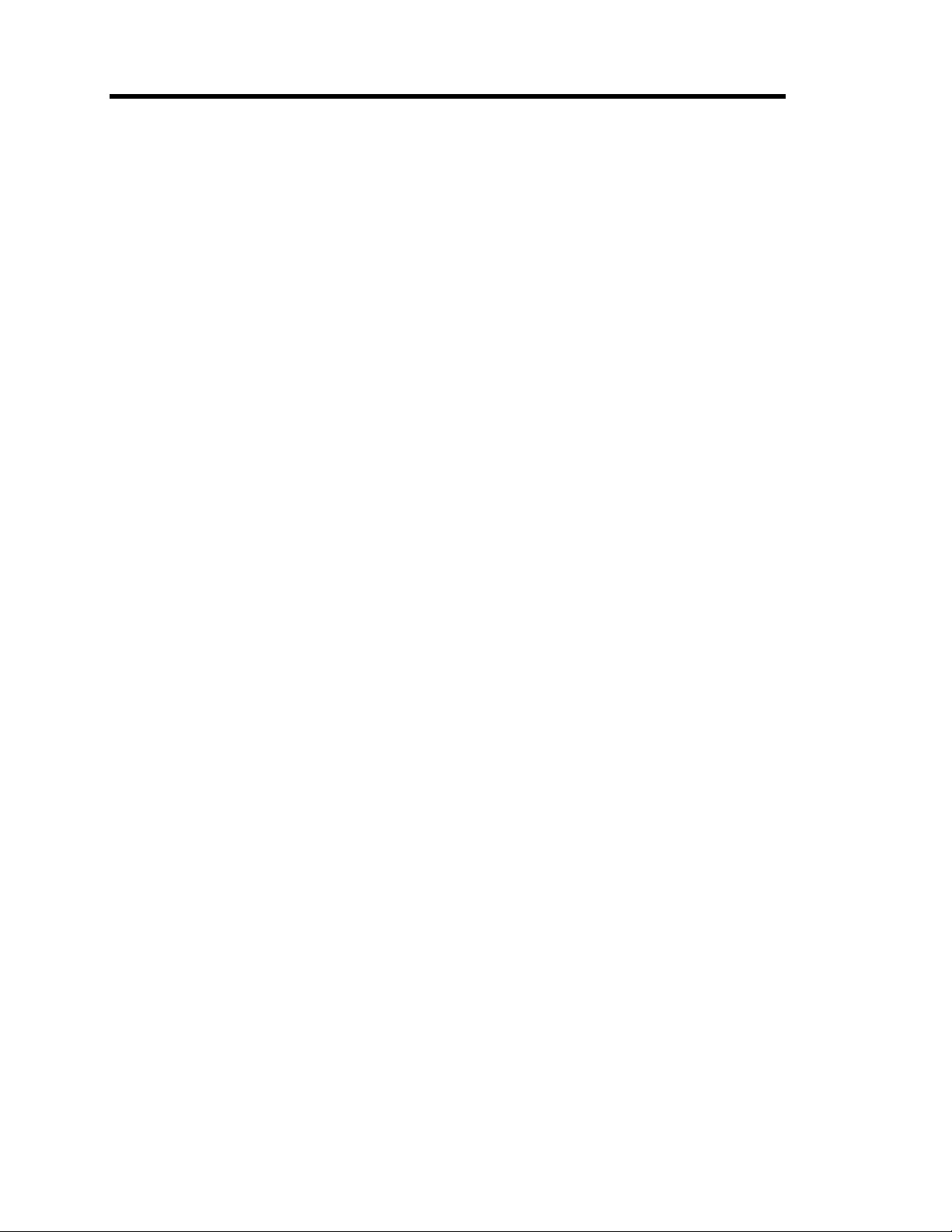

The following table shows the organization of this dictionary within the printer's memory.

Key Value

123 (1stValue)

/2ndKey /2ndData

45.76 /3rdData

/4thKey 95.11

3.2.3. Procedure Objects

Procedure objects contain a series of objects which the programmer can instruct PAL to execute at

a future time. PAL provides the "{" and "}" operators for defining procedures. These operators do

not work like the "[," "]," "<<," and ">>" operators. Instead, the "{" operator instructs PAL to

begin recording the following PAL operations and objects into a procedure object. The "}"

operator instructs PAL to stop recording.

18 PAL Language Reference

PAL also allows nested procedure definitions. This means that one procedure definition, enclosed

in the "{" and "}" operators, can contain another procedure, enclosed in its own set of "{" and "}"

operators.

While PAL records the operators and objects contained within the "{" and "}" operators, PAL does

not perform any of the operations for the operators it encounters. One exception to this rule exists.

PAL does continue to substitute immediately evaluated names with their associated objects.

Once PAL encounters the closing "}" operator and stops recording the procedure, PAL places the

procedure object on the top of the operand stack. PAL does not attempt to execute the procedure at

that time.

The programmer can treat a procedure object in many of the same ways as the programmer can

treat array or dictionary objects. This includes the ability to store procedure objects within other

composite objects. Except for allowing the programmer to execute the procedure when desired,

PAL treats procedures as any other data objects.

As an example of this flexibility, consider a case where the programmer wishes to print thermal

labels for various different parts within a company's inventory. Each part requires a label with

different information and a different overall layout.

The programmer could create, within the printer's memory, a dictionary containing all the part

numbers for each of the parts in the company's inventory. The programmer could then associated a

procedure with each of these part numbers within the dictionary.

When the programmer wishes to print a label for a particular part, the programmer need only tell

PAL which dictionary and part number to use and PAL will recall the procedure for printing that

label from the dictionary.

If the process requires additional information about the part, the dictionary could contain array

objects associated with each part number rather than procedures. These arrays could contain all the

information related to the part as well as the procedure for printing the part's label.

3.3. Internal Objects

Certain operations cause PAL to mix internal object types with the objects created by the programmer. The internal classification of object types includes the following.

Intrinsic Operator

File

Font

3.3.1. Intrinsic Operator Objects

Intrinsic operator objects actually instruct the PAL interpreter to perform one of the numerous

operations supported by PAL. The PAL interpreter contains a special dictionary, called

systemdict

When PAL encounters an executable name, PAL searches for the name in

locates the name, it recovers the object associated with the name in the dictionary. In most cases,

PAL will find an intrinsic operator object associated with the name. PAL then performs the action

indicated by the instrinsic operator.

, which associates name objects with intrinsic operator objects.

systemdict

. When PAL

Objects 19

Therefore,

eration. PAL allows the programmer to supercede the associations in this dictionary. As a result,

unlike other pr ogramming languages, P AL does not rea lly treat t he default names associat ed with

each operation as reserved words. However, changing the definition of PAL's standard names only

serves to make the programmer's PAL code harder to understand.

systemdict

3.3.2. File Objects

The PAL language supports the concept of a data file. However, the location and naming of data

files can vary from one PAL printer to the next. Typically, files may reside either in the printer’s

flash memory or in flash provided in the optional RTC card..

A file can also represent some input/output device available on the printer. As an example, the

programmer can create a PAL program which reads data from the same host interface supplying

commands to the PAL interpreter.

In order to keep track of the various information related to accessing of files, PAL creates a file

object when the programmer opens a file. PAL then places this file object on the operand stack.

The programmer can then save this object in order to access the file at a later time. Whenever the

programmer wishes to access the file, the programmer places the file object back onto the stack

and sends PAL the operator associated with the desired file access.

The file object references data private to the PAL interpreter. The interpreter does not allow the

PAL programmer direct access to this information. However, PAL does provide operators which

allow the programmer to indirectly access some of the file object information.

establishes the association between a particular name and an intrinsic op-

3.3.3. Font Objects

Each PAL printer contains a set of predefined fonts for drawing characters. Each font has a

dictionary which defines all of the characteristics of that font.

Normally, a PAL programmer can view this dictionary as the font itself. The PAL operators which

work with fonts accept this dictionary as an indication of which font to manipulate.

A font dictionary has the exact same structure as any other PAL dictionary. Therefore, the

programmer may freely access the entries within any font dictionary. However, only the most experienced PAL programmers should even consider altering the contents of a font dictionary.

4. Operators

This section uses a consistent set of notation rules to summarize the operation of the numerous

operator s availa ble und er the P AL language. The o pera tor usa ge summary lines show the oper ator

written in a monospaced bold font. For easier reading, this manual also uses a sans-serif

upright font

The list of objects which the operator expects to find on the operand stack appear to the left of the

operator. The list of objects which the operator leaves on the operand stack appear to the right of

the operator.

The text refers to the objects which the operator expects to find on the stack as the operator's pa-

rameters. The text refers to the objects which the operator leaves on the stack as the operator's re-

sults.

The operator usage summary lines use tokens to represent the positions of each parameter or result

object. The text shows tokens in a sans-serif italic font.

The usage summary lines may enclose some parameters in square brackets — "[" and "]". Square

brackets enclose optional parameters which the programmer may omit when not required. Usage

summary lines may also use an abbreviated ellipse ("..") to indicate a range of parameters.

The name of every token shown includes a suffix which indicates the object type for the parameter

or result. The following table lists the suffixes and their associated object types.

for operators listed within the main text.

Suffix Object Type

Any

Array

Bool

Dict

File

Int

Mark

Name

Null

Num

Proc

Str

Text

Any

Array

Boolean

Dictionary

File

Integer

Mark

Name

Null

Fixed-Point or Integer

Procedure

String

Name or String

22 PAL Language Reference

4.1. Alphabetical Summary

Any

AnyNum

Any1Num Any2Num

Any1Bool Any2Bool

Any1Int Any2I|nt

ElementsInt

DataAny [CtrlDict] FormatName

AnyDict

AnyProc

AnyInt ShiftInt

AnyNum

NAny..1Any

LeadStr TrailStr

NAny..1Any NInt

1Array 2Array

1Dict 2Dict

1Str 2Str

NAny..1Any

Mark NAny..1Any

ValNum DummyStr

LiteralFile

LiteralName

KeyName DataAny

NameText FontDict

FileStr AccessStr

PairsInt

DividendNum DivisorNum

BBoxArray

ColumnNum LineNum

ColumnNum LineNum

ControlDict

AnyStr

Any

1Any 2Any

1Any 2Any

Any

FormDict

FileStr AccessStr

OpenFile

FontName

AnyNum

BgnNum IncNum EndNum AnyProc

Any1Num Any2Num

Any1Text Any2Text

AnyArray IndexInt

AnyDict KeyAny

AnyStr IndexInt

AnyArray IndexInt LengthInt

==

<<...>>

[...]

abs

add

and

and

array

_barcode

begin

bind

bitshift

ceiling

clear

cleartomark

closepath

concat

copy

copy

copy

copy

count

counttomark

currentdict

currentgray

currentpoint

cvs

cvx

cvx

def

definefont

_devicefile

dict

div

dspclear

dspmovecursor

dspmoveto

dspsetcursor

dspstring

dup

end

eq

erasepage

exch

exec

execexit

execform

executive

exit

file

fileposition

findfont

floor

for

ge

ge

get

get

get

getinterval

Dict

Array

AbsNum

SumNum

AndBool

AndInt

NullArray

BoundProc

ShiftedInt

CeilingNum

ConcatStr

NAny..1Any NAny . .1Any

2Array

2Dict

2Str

NAny..1Any NInt

Mark NAny..1Any NInt

CurDict

LevelFxp

XNum YNum

DecStr

ExecFile

ExecName

FontDict

OpenFile

EmptyDict

QuotientFxp

Any Any

Bool

2Any 1Any

OpenFile

PositionInt

FontDict

FloorNum

Bool

Bool

ElementAny

ValueAny

CharInt

SubArray

Operators 23

AnyStr IndexInt Lengt hInt

Any1Num Any2Num

Any1Text Any2Text

DividendInt DivisorInt

AnyBool TrueProc

AnyBool TrueProc FalseProc

WNum HNum PolBool TmArray SrcProc

Any1Bool Any2Bool

Any1Int Any2Int

NAny..0Any IndexInt

AnyDict KeyAny

Any1Num Any2Num

Any1Text Any2Text

AnyArray

AnyDict

AnyStr

XNum YNum

AnyProc

Any1Num Any2Num

Any1Text Any2Text

AnyStr SetStr

AnyFontDict TmArray

LimitsArray PagesInt

DividendInt DivisorInt

XNum YNum

Any1Num Any2Num

1Any 2Any

AnyNum

AnyBool

AnyNum

Any1Bool Any2Bool

Any1Int Any2Int

ScoreSrr

Any

AnyStr

AnyArray IndexInt ElementAny

AnyDict KeyAny V al ueAny

AnyStr IndexInt CharInt

TargetArray IndexInt Sourc eArray

TargetStr IndexInt Sourc eStr

AnyArray IndexInt SubArray

AnyStr IndexInt S ubStr

OpenFile AnyStr

CountInt AnyProc

XDeltaNum YDeltaNum

XDeltaNum YDeltaNum

AngleNum

AnyNum

AnyStr SetStr

XScaleNum YScaleNum

AnyFontDict Sc al eNum

AnyStr SearchStr

AnyStr SearchStr

OpenFile PositionInt

ScaledFontDict

LevelNum

CapInt

getinterval

globaldict

gt

gt

idiv

if

ifelse

imagemask

_imp

_imp

index

initgraphics

initmatrix

known

le

le

length

length

length

lineto

_localtime

loop

lt

lt

_ltrim

makefont

mark

_measurepage

mod

moveto

mul

ne

neg

newpath

not

not

null

or

or

_play

pop

print

put

put

put

put

put

putinterval

putinterval

quit

readstring

repeat

rlineto

rmoveto

rotate

round

_rtrim

scale

scalefont

search

search

setfileposition

setfont

setgray

setlinecap

SubStr

GlobalDict

Bool

Bool

QuotientInt

ImpBool

ImpInt

NAny..0Any IndexedAny

Bool

Bool

Bool

ElementsInt

PairsInt

CharsInt

TimeArray

Bool

Bool

TrimmedStr

TmFontDict

mark

SizeArray

RemainderInt

ProductNum

Bool

NegNum

NotBool

NotNum

Null

OrBool

OrInt

ReadStr

RoundedNum

TrimmedStr

ScaledFontDict

PostStr MatchStr PreStr

false

AnyStr

true

24 PAL Language Reference

WidthNum

TimeArray

ControlDict

ShowStr

PagesNum

CharsInt

AnyStr

Any1Num Any2Num

XTransNum YTransNum

AnyNum

AnyDict KeyAny

OpenFile AnyStr

Any1Bool Any2Bool

Any1Int Any2Int

setlinewidth

_setlocaltime

setpagedevice

show

showpage

_showpages

string

stringwidth

stroke

sub

translate

_trap_

truncate

undef

userdict

vmstatus

writestring

xor

xor

NullStr

XDeltaNum YDeltaNum

DifNum

TruncatedNum

userdict

BytesInt

XorBool

XorInt

Loading...

Loading...