Page 1

HOW THE

AGA

COOKER

HOW THE AGA COOKER BECAME AN ICON

BECAME AN

ICON

The story of the talented individuals

who helped shape the future

of life in the British home

PLUS

perfect for 21st century living

why the modern AGA is

Page 2

TEN dEcadEs of hEriTagE

and still at the cutting edge today

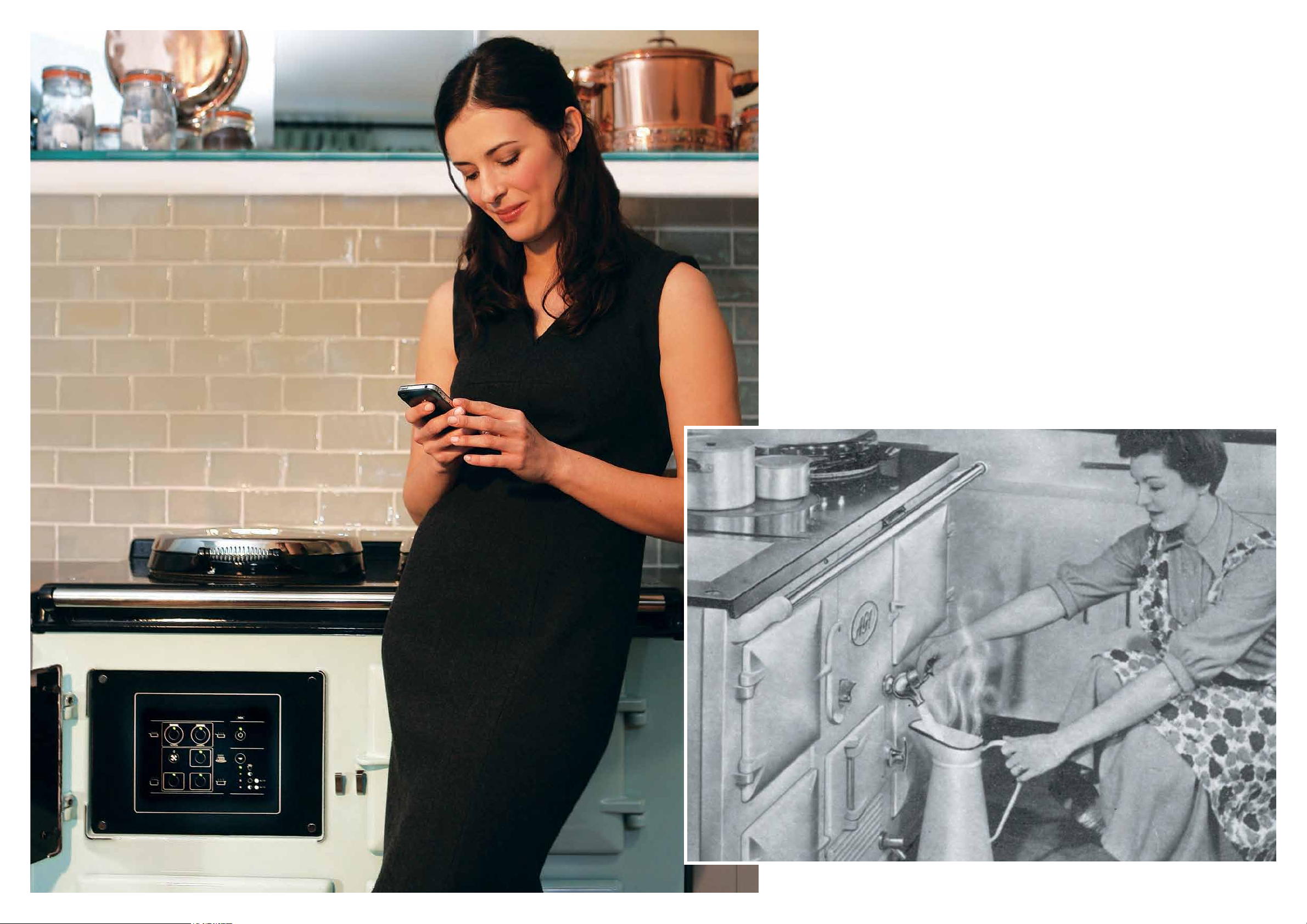

When the AGA cooker was introduced to the UK in 1929, seven

years after its invention, it was an instant success. It is now in its tenth

decade and it continues to innovate. The very latest technology has been

employed to continue the kitchen revolution. There is the ultra-modern

AGA Total Control. From the outside, the AGA Total Control looks

exactly like a classic AGA cooker. But beneath its cast-iron exterior lies a

state-of-the-art touchscreen control panel that enables owners to operate

the cooker in a way that suits them. The AGA iTotal Control takes this

a stage further, with oven programmability made possible by remote

control, even via the web or a smartphone. The AGA, then, is not resting

on its laurels. It remains steeped in heritage, but keen to continue to

innovate to ensure it is as relevant for the 21st century as it was in the

1930s when a team of brilliance made it a British icon.

How e AGA Became An Icon 3

Page 3

forEWord

he AGA cooker is a way of life. It commands

levels of adulation more oen associated

T

similar loyalties. One woman taking part in an AGA

demonstration went so far as to insist it was warmer,

more reliable and infinitely better looking than most

men and that, given the choice between her husband

and her AGA, she’d waste no time packing his bags!

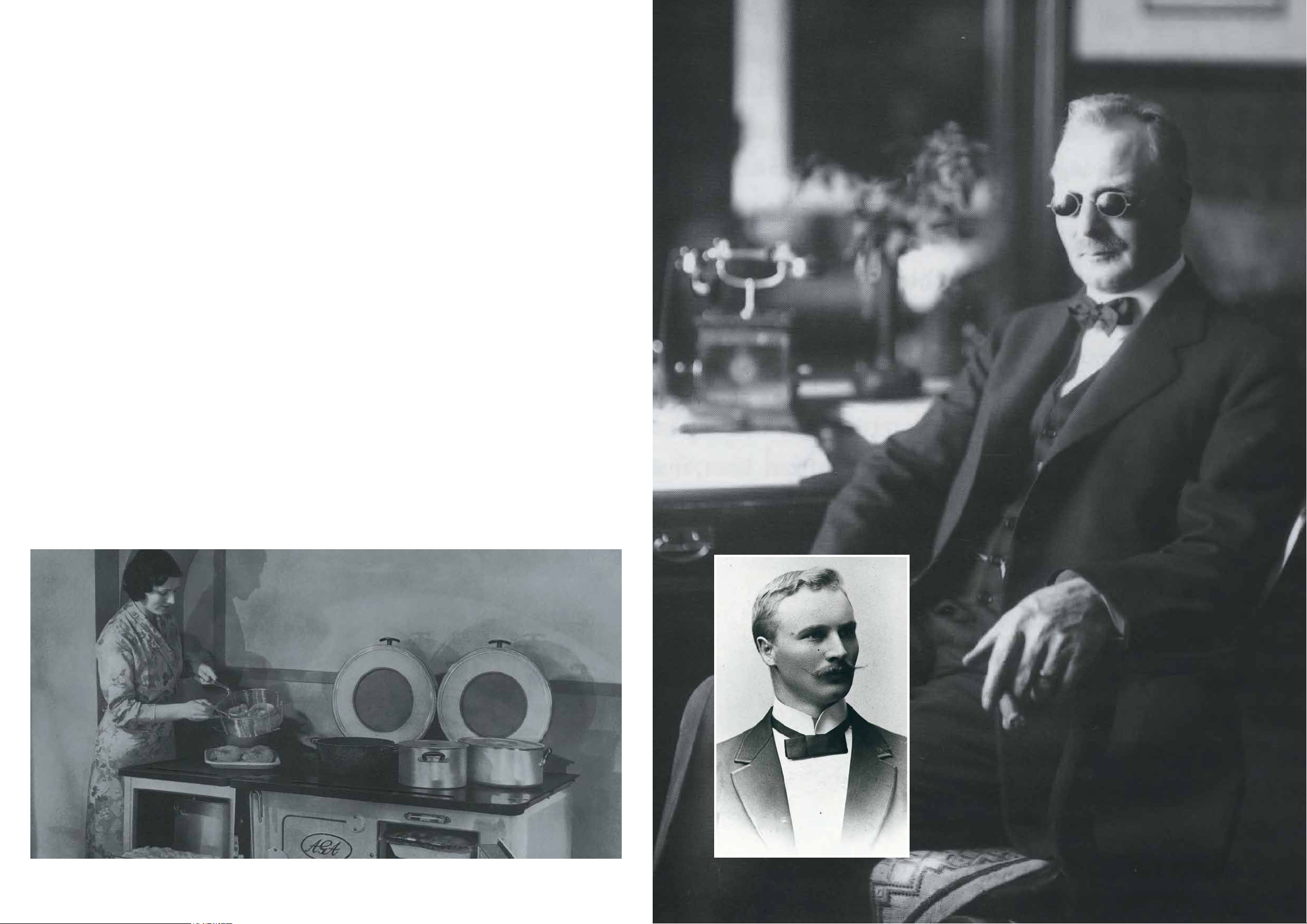

e inventor of the AGA cooker in 1922 was

Dr Gustaf Dalén, could have imagined the heady

heights of fame that his creation would go on to

reach. Dalén, an entrepreneur and a Nobel Prizewinning engineer and devoted husband. Intellectually

and commercially, he wanted to create an efficient

stove that would free his wife from domestic drudgery

and address the engineering question of how best to

get heat from its source into the food. Radiant heat

from the cast-iron walls of the AGA cooker’s ovens

provided the answer.

Now, the AGA cooker once most associated with

rambling country piles and farmhouse kitchens

complete with orphan lambs and sodden spaniels is

with the latest boy band and generates

just at home in an über-hip metropolitan

environment. e modern version is setting out to be

a world class cooker, able to take on all cookery styles

whatever their origins.

For the world’s most famous cooker is now also the

globe’s coolest cooker. Its enduring good looks are

seducing yet another new audience. Today, it finds

itself dancing chic-to-chic with a more independently

minded, more metropolitan consumer and wherever

you are in the world you can have an AGA cooker

that works for you.

e AGA boasts a peerless pedigree and is today cast

in iron at the historic Coalbrookdale foundry in the

Shropshire hills that is a World Heritage Site and

was at the very birthplace of the Industrial Revolution

when, in 1709, Abraham Darby first smelted iron ore

with coke to make cooking pots.

Its design has been allowed to evolve with care to the

point where the cooker’s look has now achieved icon

status. e special place it occupies in the hearts and

minds of owners is unique and undeniable.

q

How e AGA Became An Icon

4

Inventor of the AGA cooker, Dr Gustaf Dalén,

a Nobel Prize-winning physicist

How e AGA Became An Icon 5

Page 4

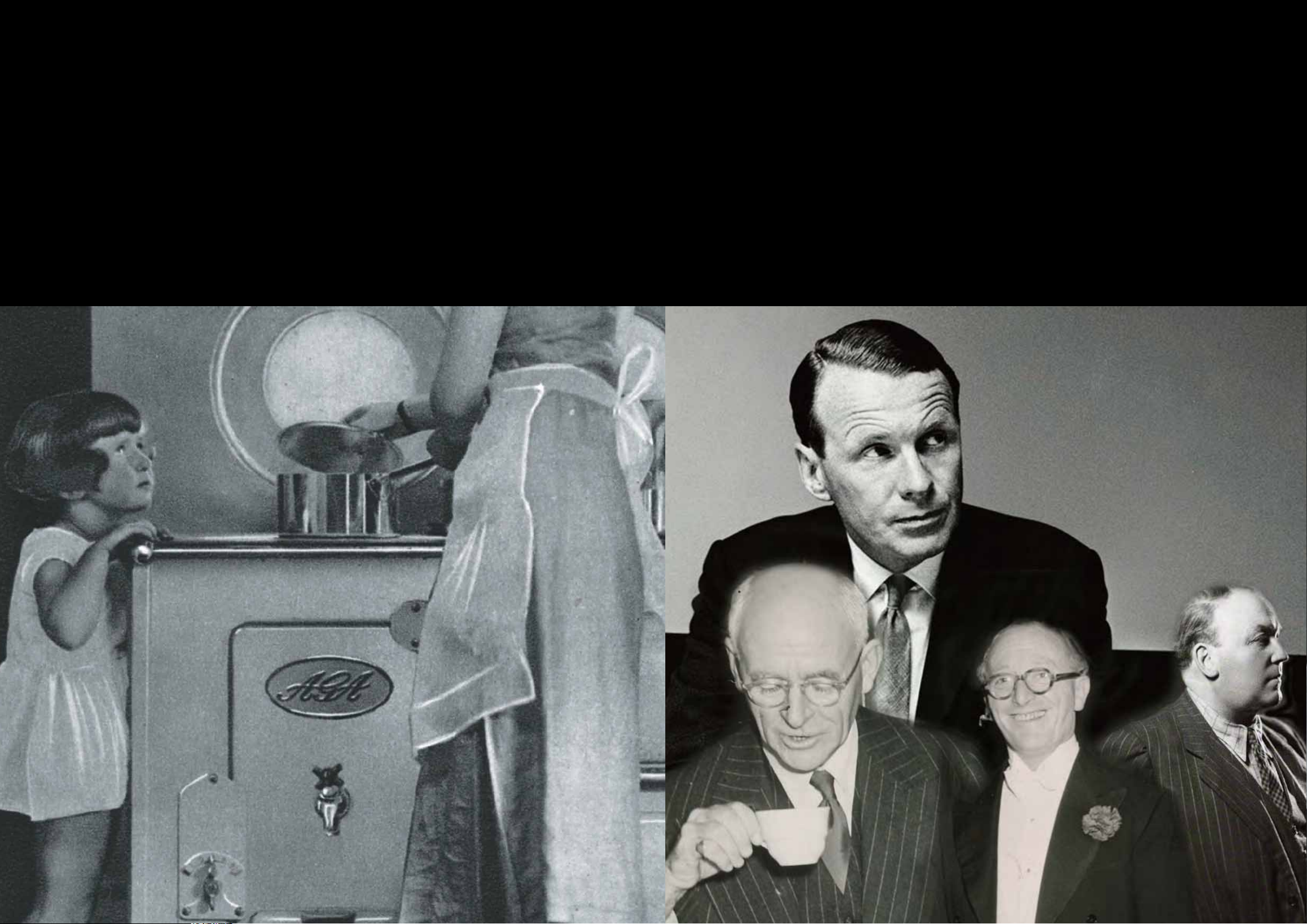

SALUTING the individuals whose

vision created one of the world’s

most respected brands…

Mention the word AGA to anyone and you’ll get

an immediate and emotional response. It is quite

simply the most famous cooker and one that is

loved by millions the world over.

While the AGA is well-known for its brilliant cooking

performance and iconic good looks, there is also a

remarkable story behind the emergence of the

AGA cooker as an icon.

Between 1933 and 1946 an extraordinary team of

people came together and had a lasting impact on

the way we cook and the way we live.

When we launched the AGA Total Control in 2011,

themes from the 1930s still resonated today. We

investigated further.

A role such as mine within AGA is many faceted,

with one distinct element being that of brand

custodian. It was with this in mind that we took on

a project to research and collate our archives with

a view to understanding the origins of the power

and unique appeal of the AGA cooker.

Over the course of our investigations it became

clear that one man, W.T. Wren, was responsible

for bringing together a team of such talent and

prescience that they quite simply changed the way

Britain lived.

These changes, which centered on the launch of

the New Standard AGA, were not short lived and

even now the impact that they had on the shape

of our homes and our lives remain.

That’s why we have created this publication to

provide an insight into a fascinating social history,

to celebrate the company’s rich and varied

heritage and, of course, to bring the archives to life.

William McGrath

CEO AGA Rangemaster Group

Page 5

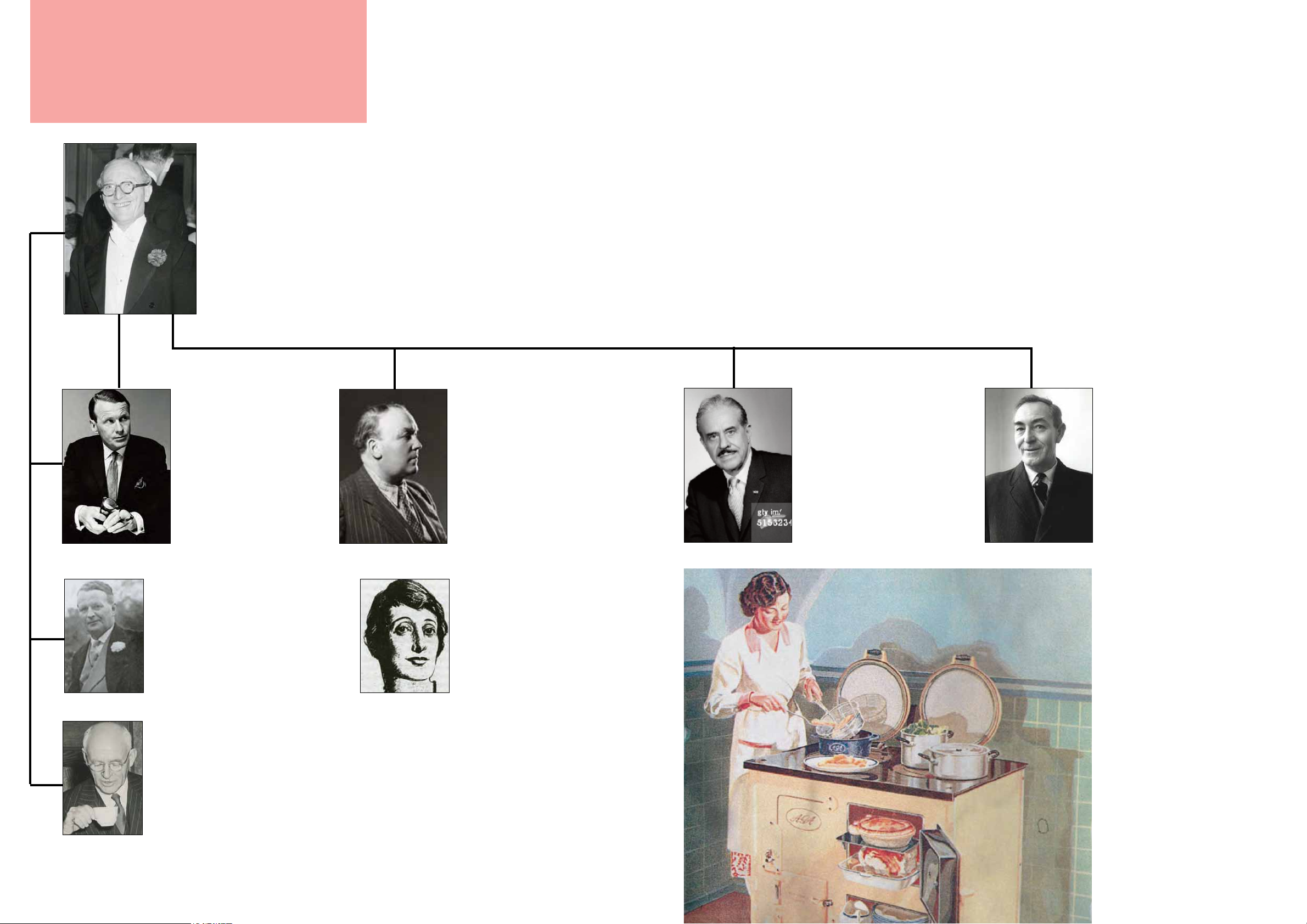

12 visionaries

The individuals who made it all happen

W. T. Wren

l Head of AGA Heat

and Allied Ironfounders

l Innovator

l Visionary

l Second World

War spy

David Ogilvy

l First AGA salesman

and marketing

consultant

l Advertising genius

l The inspiration for

TV’s Mad Men

l Second World War spy

Sometimes, when a group

of people gell, there is an

alchemy that ensures

something extraordinary will

happen. This was the case

when the team below came

together to ensure the AGA

Ambrose Heath

l Gastronome

l Food writer

l First celebrity cook

l Author of the early

AGA cookbooks

cooker was to become an icon. They showed the world the importance of

great design, perfectly cooked food, economy and ergonomics – all within

the kind of modern kitchen setting that had never been seen before. In

fact, from 1935 – in developing and launching the New Standard AGA

cooker – they shaped the future and changed the way people lived. It

was their influence that made the kitchen the most important room in the

house and made good food and cooking a new national interest…

Raymond Loewy

l US industrial design guru

l Head of Raymond Loewy

Associates

l Oversaw re-design of

the AGA cooker through

London offices

l Styled the Rayburn

Douglas Scott

l Industrial designer

l Re-designed the AGA

cooker

l Introduced the

Standard Model C AGA

cooker

l Designed the Rayburn

How e AGA Became An Icon

8

Francis Ogilvy

l Head of ad agency

Mather & Crowther

l Second World

War writer for

Prime Minister

Winston Churchill

Charles Ludovic Scott

l AGA Heat Ltd’s

Technical

Research Officer

l Responsible for the

technology behind

the new Standard

Model C AGA cooker

Dorothy Braddell

l Redefined how Britain

saw the kitchen

l Designed AGA kitchen

roomsets in 1930s

and 40s

Lawrence Wright

l Pioneering perspective artist

l Illustrated AGA Heat’s roomset designs

Mabel Collins

l 1935, head of AGA Heat Ltd’s

new Cookery Advisory Department

Carl Otto

l Industrial designer

l Designer of the Otto

stove

l Head of the London

office of Raymond

Loewy Associates

Edward Bawden

l Artist and illustrator

l Illustrated many

iconic AGA

brochures and

recipe sheets

How e AGA Became An Icon 9

Page 6

W T WREN

AGA Heat Ltd

managing director

Leader and innovator

Second World War

agent

Managing Director of

AGA Heat Ltd from early

1930s to 1950s, also

becoming Managing

Director and Chairman

of parent company Allied

Ironfounders. Through

the 1930s W.T. Wren

pushed the AGA cooker,

recognising its potential

impact. He said: “Owners

come to talk about and

regard their AGA as

though it were almost

a member of the

household – a fond

personality which has

won their affection.

Servants love it…so do I”

He felt so passionately

about the AGA that he

formed one of the

greatest cross-disciplinary

teams in UK industrial

history and expanded

across the country by

building a strong group

of registered distributers,

largely family concerns

and some with long and

important histories of

their own.

Every now and then someone captures the zeitgeist so perfectly they

become the centre of something truly extraordinary. W. T. Wren – or

‘Freckles’ as he was known – was one such man…

shaPiNg ThE fUTUrE

. T. WREN’s ability to see how the future

was shaping up and his skill in spotting

W

simply changed the way people lived and –perhaps

even more surprisingly – the eect can still be felt

today.

Wren was born at the turn of the century into a poor,

working class family, a fact he never forgot. He joined

the Chubb & Sons Lock and Safe Company as an

oce boy, but graduated to act as a representative in

India. From Chubb he went to Bell's Engineering

Supplies where, in 1929, he was put in charge of

selling the rst AGA cookers in Britain.

Such was his success that in 1932, when Bell’s became

AGA Heat Ltd, Wren was its MD, a role he still held

in the 1950s. By then, via a time as sales director, he

had become Managing Director and later Chairman

of the parent company, Allied Ironfounders Ltd.

He was a member of the Council of Industrial

Design (later to become the Design Council) and

his obituarist noted his unusual ability to see the

importance of design: “He was a man who

saw the value of high standards of industrial design

linked to expert salesmanship and social purpose at a

time when such attitudes were rarely held, let alone

applied to a large commercial undertaking.”

As well as realising the importance of great design,

Wren also understood the value of approaching marketing from an entirely new angle and this, combined

with his ability to bring together interesting people,

really were at the forefront of the success of the AGA

cooker, turning it from a simple domestic appliance

talent was so nely honed that he quite

1

into the icon it remains today.

In a strategy paper from 1933, Wren demonstrates

his innovative approach to marketing. He wrote…

“Words are sickeningly inept instruments of enthusiasm.

But perhaps, helped out by the photographs, I have given

you a fairly complete picture of this cray cooker.

“If you visit an AGA Showroom anywhere you will find

out a lot more and, more important still, you will get

what I cannot give you, the spirit of the AGA.”

Fieen years aer the introduction of the AGA to

Britain, Wren – who would be driven everywhere

in his Rolls-Royce with the licence plate AGA 1 –

was clearly aware he and his team had achieved

something special and signicant. He recognised that

the cooker had achieved a “unique place in the sun”

and had become a household name, an eponym

for all range cookers.

Wren returned from the war in 1945. In a report

written for the Executive Board, A Wider Base for

AGA, he described the progress the AGA cooker had

made during his time at the helm:

“It is now 15 years since the AGA was rst introduced

to this country...it has gained a unique place in the

sun and, in a certain eld, is a household word. No

other domestic appliance in the generation has

achieved so well a foothold. ose engaged in

launching it were...of the ‘traditional’ trade approach

for a product of this type; and probably just as well,

for had they followed the traditional line, it is

doubtful if AGA would have survived the course.

But it did survive and made so serious an

s

How e AGA Became An Icon 11

Page 7

W T WREN

impression on the trade that [others] have

followed AGA almost slavishly in marketing

methods.

“All this, to my mind, shows that there is

something new in the AGA way of marketing

a domestic appliance which is regarded as

both successful and necessary by our

competitors.”

In Wren’s obituary in Design, the journal of

the Council of Industrial Design, Richard

Carr wrote: “He [Wren] already believed in

the value of selling an appliance which used

1

only 3

/2 tons of coke a year instead of the 24

tons of coal consumed by the average kitchen

boiler.

“A meeting with Francis Ogilvy of Mather

and Crowther encouraged him to improve

the AGA still further by calling in Raymond

Loewy as the company’s design consultant

[see page 18]. is led to the development of

a complete range of well designed appliances,

including the Otto stove, named aer Carl

Otto who worked in Loewy’s oce, the

Rayburn and the AGAmatic domestic water

heater.

“e association with Mather and Crowther

also led to the adoption of outstandingly high

standards of writing, illustration and printing

for the company's literature, while Wren

followed his own clear policy on salesmanship, cutting down retail outlets and

appointing as agents only those builders'

merchants, ironmongers and even individuals

whom he could rely on to give expert service.

“He also introduced such ideas as a circular

on AGAs in Latin, and then in Greek, for

distribution to schools, and an exhibition in

two air conditioned railway coaches which

toured Britain in the 1950s to display the

company products.”

Wren also became an animated commentator

on social issues and, in combination with

organising travelling exhibitions, he

commissioned lms during the 1950s to

make local authorities aware of the need to

modernise Victorian slums and war-damaged

properties.

But perhaps Wren’s lasting legacy stemmed

from a remarkable ability to see design,

marketing and engineering ability and to then

assemble the right team for the times. He

knew by the late 1930s that the original AGA

cooker – introduced to Britain in the late

1920s – needed to be re-designed and

updated.

For this, he called in renowned American

industrial designer Raymond Loewy, who was

to go on to design the interiors of Concorde

for Air France and Air Force One for the US

government.

Wren was aware that the AGA cooker’s

unique selling points needed a unique sales

force. For this job, he turned to David Ogilvy,

who was to go on to revolutionise advertising

as the so-called King of Madison Avenue and

later to be the inspiration for TV’s Mad Men.

He was aware the times were changing and,

as domestic service in Britain declined, he

asked designer and domestic planning

advocate Dorothy Braddell to come up with

a functional new look for British kitchens.

He commissioned a series of cookbooks from

the celebrity chef of the day, Ambrose Heath,

which were illustrated by Edward Bawden,

who was to go on to become an artist of

major repute.

Over the coming pages we look at the visionaries

who made up Wren’s team, talented individuals

who succeeded in embedding the AGA cooker in

the British psyche.

q

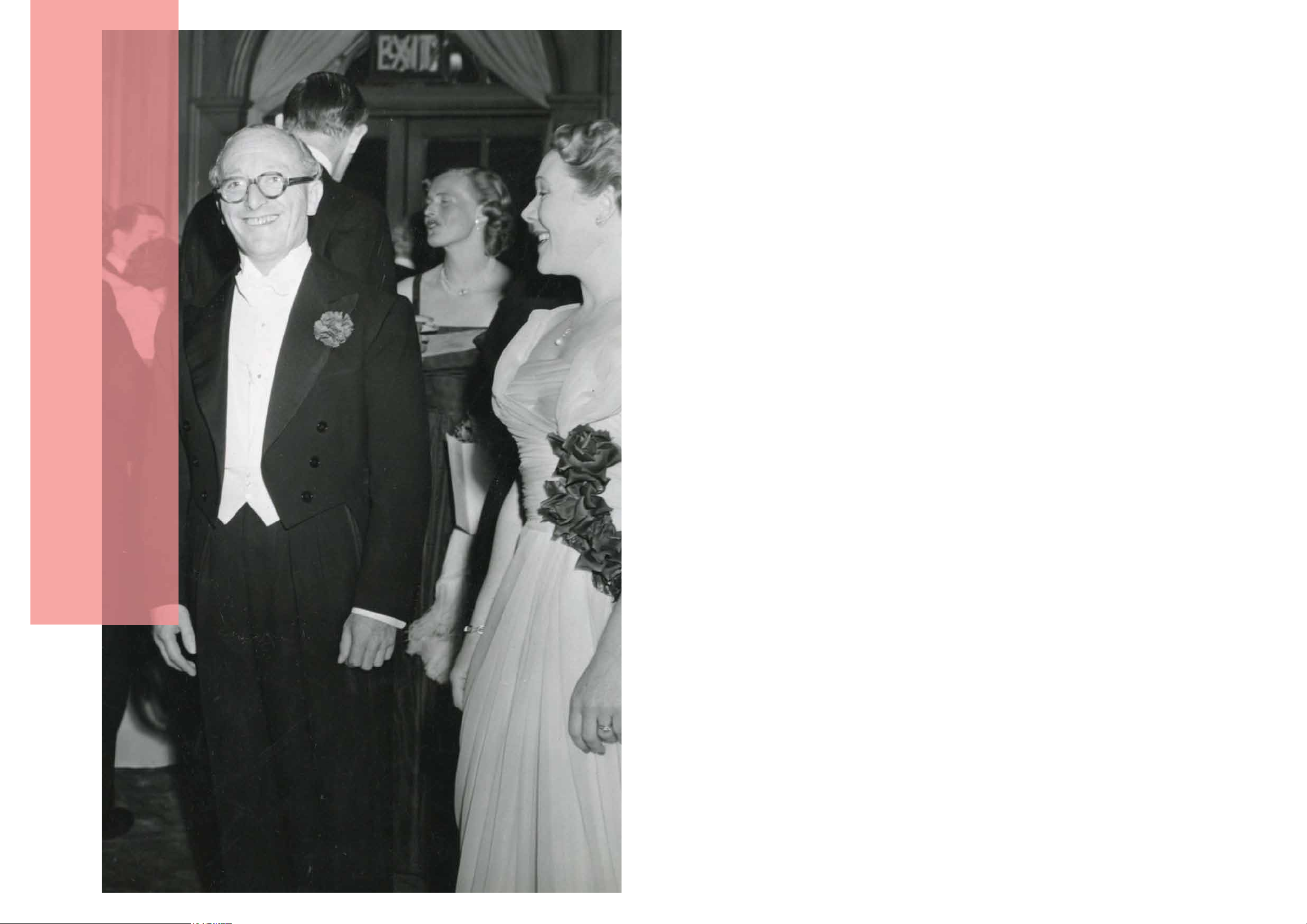

W. T. Wren frequently hosted lavish

dinners at the Dorchester for AGA

distributors (above). The famous

London hotel was also used for

company meetings, as illustrated

by the extract (left) of the minutes

from a board meeting in 1945,

when it was agreed the discussion

should be “adjourned for lunch and

the meeting continued at the

Dorchester Hotel”

At the same meeting, the board

reviewed how the AGA cooker

had been launched in the UK

and concluded (left) that it would

not have been the immediate

success it had been if those

behind the project had been

prejudiced by accepted selling

practices of the time

A silver inkwell fashioned in

the form of an AGA cooker and

presented to W. T. Wren

by his colleagues in 1937

12 How e AGA Became An Icon

How e AGA Became An Icon 13

Page 8

DAVID OGILVY

AGA Heat Ltd’s first

salesman

Advertising genius

Inspiration for TV’s

Mad Men

Second World War spy

David Mackenzie Ogilvy

was born on 23 June

1911 at West Horsley,

Surrey in England. Ogilvy

attended Fettes College,

in Edinburgh. In 1929, he

again won a scholarship,

this time in history to

Christ Church, Oxford.

He left Oxford for Paris in

1931, where he became

an apprentice chef in the

Majestic Hotel. After a

year, he returned to

Scotland and started

selling AGA cookers

door-to-door. His success

at this marked him out to

his employer, who asked

him to write an instruction

manual, The Theory and

Practice of Selling the

AGA Cooker. Thirty years

later, Fortune magazine

editors called it the finest

sales instruction manual

ever written and Ogilvy

went on to become a

giant of advertising.

GETTY

IMAGES

In 1935, AGA Heat Ltd managing director W.T. Wren appointed his

Scottish sales rep to update how the cooker was being sold and

marketed. Showing impressive prescience, he had given international

advertising legend David Ogilvy his first big break…

ThE TENaciTY of a BULLdog,

ThE MaNNErs of a sPaNiEL…

By 1935, marketing of the AGA cooker had become

big business and the summer launch of the New

Standard AGA – a twin-oven model in cream aimed

at smaller households without domestic staff – saw

AGA Heat Ltd embark on a nationwide publicity

campaign to raise awareness of the brand within a

much broader audience.

For that launch, he used Mather & Crowther as the

advertising agents and specifically the talented Ogilvy

brothers, David and Francis. e decision proved to

be game-changing.

For Wren had again shown incredible prescience.

David Ogilvy’s guide to selling the AGA cooker –

e eory and Practice of Selling the AGA Cooker –

became the company’s sales ‘bible’ and was lauded by

Fortune magazine as ‘the best sales manual ever writt e n’.

modernity. It wasn’t a fad, a passing fancy. It looked

solid, it was solid. It was the Rolls-Royce of the

kitchen and people realised that very quickly.”

Ogilvy was the first AGA cooker salesman in

Scotland and rapidly established himself as a

formidable salesman. He was introduced to W.T.

s

David Ogilvy devised AGA cooker advertising and provided an explosive critique of the marketing of the parent company,

Allied Ironfounders. Revisiting the report in 1962, he wrote: “It proves two things: a) At 25 I was brilliantly clever; and

b) I have learnt nothing new in the subsequent 27 years.”

2

Ogilvy himself proved to be an advertising genius

who went on to found one of the world’s biggest

advertising agencies, Ogilvy & Mather. By the end

of his career he was known as the King of Madison

Avenue and he was the inspiration for the hit

television series, Mad Men.

Ogilvy, who occupied an office in the AGA Heat

building, was driven by a passion for the AGA cooker.

Later in his career, he said: “It was a special kind of

David Ogilvy pictured in 1938 on board a

ship bound for his new home in America

How e AGA Became An Icon 15

Page 9

DAVID OGILVY

Wren by his brother, Francis, and earned his spurs by

using his chef ’s uniform from his stint in a Paris

restaurant to persuade a London club to keep their

AGA cookers. It was with the 1935 launch of the

New Standard AGA that Ogilvy produced some

quite exceptional work in preparing the company

and its dealers for the launch and then providing the

required consumer literature.

In e eory and Practice of Selling the AGA Cooker

– setting out the argument on the attack and on the

defence when winning over a sales prospect – he

concluded that the successful salesman “needs the

tenacity of the bulldog and the manners of the

spaniel.

“If you have any charm,” he wrote, “ooze it”.

Francis Ogilvy (pictured left with his family, c 1950)

introduced his younger brother to W. T. Wren. Francis –

the leading player at advertising agency Mather &

Crowther and the force behind its regaining the AGA Heat

Ltd account in 1946 – was also a talented copywriter in

his own right and went on to become one of Prime

Minister Winston Churchill’s speechwriters during the

Second World War.

q

This ad creative – drawing on Édouard

Manet’s Dejeuner Sur L’Herbe – was

David Ogilvy’s first ever advertisement.

It demonstrates how the advertising

pioneer was not averse to esoteric and

challenging campaigns. Looking back

on it, however, he confessed it was

“some way short of his best”

BOARD MINUTES, June 1945

In these minutes (below) of a meeting of the board of

AGA Heat Ltd, a resolution is passed to “recapture the old

originality” of previous AGA advertising. Previous

advertisements had worked, the board agreed, because

the company had made liaison with their ad agency more

of a “personal affair”. The new campaigns would focus on

three main messages: the ease of using the AGA (lack of

servants); fuel economy (national lack of solid fuel); and

better cooking. With modern AGA advertising campaigns

focusing on the launch of new programmable models,

their improved fuel efficiency and the wonderful cooking

results that can be achieved, it would seem the AGA

legacy very much continues today

How e AGA Became An Icon

16

How e AGA Became An Icon 17

Page 10

THE WAR YEARS

a VErY sEcrET sErVicE

Called away from their work at the outbreak of the Second World War,

W. T. Wren, David Ogilvy and his elder brother Francis Ogilvy found

themselves volunteering for the murky world of counter-espionage…

W. T. Wren

e rst documentary evidence of W. T. Wren having

le AGA Heat Ltd to play his part in the Second

World War comes in an executive minute in which

it is agreed that his salary and bonus would –

reassuringly – be paid on the same basis as if he were

still carrying out his duties with the company.

Upon Wren’s return to the company in 1945 he is

referred to as Colonel Wren. Sources then mention

him being involved in dierent ways during the

war, most oen as an MI6 section V ocer

(counter-espionage) and eventually as Head of the

Security Branch in London of British Security

Coordination (BSC).

While Wren seems to have ended the War based in

London, he is recorded as having lived in Trinidad for

several years in the early 1940s as MI6 head of station

there. He travelled a lot, and is recorded as having

been in New York oen, as well as in Sweden (1939

and 1940), Canada (1942), and was in charge of

operations in Spain by 1943.

David Ogilvy

According to his biographer, Kenneth Roman,

David Ogilvy also worked for British Security

Coordination (BSC). In his book, e King of

Madison Avenue: David Ogily and the Making of

Modern Advertising, he writes that Ogilvy had been

moonlighting since 1939 as an adviser to the British

government on American public opinion. In 1942,

with the United States now embroiled in the Second

World War, he went to work full time in British

military intelligence, initially in New York. His new

boss in the spy business was Sir William Stephenson,

head of BSC and the central gure in covert

operations involving Britain and the United States in

the years leading up to the war. BSC was to represent

all British intelligence services in the Western

Hemisphere. A compelling personality, Stephenson

became a model for Ian Fleming’s famous secret

agent, James Bond 007.

Kenneth Roman writes: “A small man with piercing

blue eyes, the strong-willed Stephenson – Ogilvy

described him as “quiet, ruthless, and loyal”– took

on the dicult task of combining propaganda for

the British cause with intelligence work and

counterespionage and carving out a working

arrangement with American intelligence within

the limits of the Neutrality Act.

“Stephenson was not a professional spy, nor were

many of the people he recruited. His unlikely team

was largely comprised of enthusiastic amateurs

whose names and faces were not known to enemy

intelligence agencies. e team included actors Leslie

Howard, David Niven and Cary Grant, the movie

director Alexander Korda, author Roald Dahl (who

would later assist on a history of BSC) and Noel

Coward.”

“[David] Ogilvy was perhaps the most remarkable of

the younger men to join Stephenson’s BSC,” wrote

the man who recruited him, Harford Montgomery

Hyde in his insider’s book Room 3603.

He started his new job by attending a course for spies

and saboteurs at Camp X, ocially Special Training

School 103, a top secret British training school on the

north shore of Lake Ontario in Canada. ere, he

said, he was taught the tricks of the trade: how to

follow people without being observed, how to blow

up bridges and how to kill a man with his bare hands.

Instead of being parachuted behind enemy lines, as he

expected (or, more likely, feared), Ogilvy was placed

in charge of collecting economic information from

Latin America, to assist BSC agents in foiling

businessmen known to be working against the

Allies by supplying Hitler with strategic materials.

Ogilvy’s basic job, according to intelligence

expert Richard Spence, was to spin polling

information considered harmful

(or helpful) to British interests. BSC wanted results

that would steer opinion toward support of

Britain and the war – front-page stories that showed people were more

interested in defeating Hitler

than staying out

of war.

Spymaster Stephenson put

on record his high regard

for Ogilvy’s abilities –

“literary skill, very keen

analytical powers,

initiative and special

aptitude for handling

problems of extreme

delicacy,” adding that

“David not only made a good

intelligence ocer, but he was

a brilliant one”.

Francis Ogilvy

David Ogilvy was not alone. While he was at BSC,

his elder brother, Francis, was working in British

intelligence. He made a memorable impression on

one assignment in Scotland. Hyde talks about Francis

arriving “complete with black hat and striped trousers,

in a remote Scottish village, and, on asking the postmaster if he would accept two parcels of stores, was

promptly handed over to the police.”

Safely extricated from police custody, he went on to

serve in a less conspicuous but more inuential role.

When Churchill became Prime Minister in 1940,

he dened one of the requirements for his sta as the

ability to write well, listing among several candidates a

professor of English at Oxford and “that man who’s

writing the bombing reports”.

It was Francis Ogilvy’s reports that Churchill had

been reading. For most of the Second World War,

Squadron Leader F. F. Ogilvy lived in the Cabinet

War Rooms, where he was on watch every night.

Kenneth Roman adds: “As he described it, you’d get

to sleep at some unearthly hour, the Old Man would

come down, shake you and dictate – not verbatim as

one would to a secretary, but in broad general terms,

outlining what he wanted to say, leaving it to the

transcriber to do the actual writing, in Churchillian

style. I want a cable to Roosevelt, Churchill might

say. Copy to Stalin, copy to the Joint

Chiefs of Sta. en he would

outline his ideas. ‘And have it

ready for me at breakfast’. ”

Francis Ogilvy believed,

when he started the

job, that he had some

talent as a writer. He

later said: “I realised I

couldn’t. But by the

time he [Churchill]

nished shouting at

me and educating me,

by the end I thought

perhaps I could.”

By 1945 he was back with

W. T. Wren working on

launches of the AGA cooker and

Rayburn cooker and helping his brother

set up the New York branch of the advertising agency.

e brothers remained close, with David writing

to Francis almost weekly to discuss personal and

business issues, including a paper proposing

irty-Nine Rules for advertising copywriters.

Kenneth Roman writes: “With his paper, [David]

Ogilvy took credit for reorienting Francis’s agency

away from “poetry, typography and nonsense” and

“an opportunity to patronize ne writers, modern

writers and typographers.” q

18 How e AGA Became An Icon How e AGA Became An Icon 19

Page 11

RAYMOND LOEWY

In 1936, the acclaimed industrial designer Raymond Loewy was

Designer

Innovator

Head of Raymond

Loewy Associates

Raymond Loewy (1893–

1986) was an acclaimed

industrial designer and

reputed to have been the

first to be featured on the

cover of Time magazine

(1949). Born in France,

he spent most of his

professional career in the

United States. Among his

most notable designs

were the Shell and BP

logos, the Greyhound

bus, Coca-Cola vending

machines and the Air

Force One livery. His

career spanned seven

decades and included

important design work

in the UK overseeing

the launch of the New

Standard AGA cooker.

Between 1936 and 1941

this team launched and

updated the New

Standard AGA cooker,

leading to the production

of a formidable portfolio

of technical innovations.

modern AGA cooker.

He was also responsible

for the look of the

Rayburn cooker.

GETTY

IMAGES

recruited by W. T. Wren to re-design the AGA cooker. It was a

master stroke with the new model launched in 1941 and still in

production three decades later. Here, we profile the influential

American designer and the talented design team he assembled…

dEsigNs oN ThE fUTUrE

e concept of industrial design, recognised as

a separate discipline, was introduced to Britain

from the United States prior to the First World

War. During the 1930s it was encouraging

interest and criticism in almost equal measure.

But by the 1930s – with industrial design and

production eciency becoming mainstream

subjects – W.T. Wren saw there was further

progress to be made with the AGA cooker and

decided the future of the AGA cooker’s look

should be shaped by a man with an international

reputation.

Wren decided on Raymond Loewy, widely

acknowledged since as one of the leading

designers of the 20th century. e work on

the future design of the AGA cooker would

be carried out under the auspices of the newly

founded London oce of Raymond Loewy

Associates.

In the broader eld of industrial design,

Raymond Loewy Associates had contracts with

140 clients in America and 60 in Europe. Loewy

maintained design studios in New York, Chicago,

London and Paris and for years the name

Raymond Loewy Associates was synonymous

with outstanding product and package design,

with its portfolio spanning the design of aircra

interiors, luxury ocean liners, buses, department

stores, architecture and supermarkets.

An expression was coined to describe the scope

of work of the Loewy organisation: "... in design,

everything from lipsticks to locomotives."

e London oce of Raymond Loewy

Associates was unique in Britain as the only

purely professional industrial design oce in the

country. It opened in 1936 and the extraordinary

relationship with Mayfair-based AGA Heat Ltd

began with the appointment of Carl Otto and

Douglas Scott as stylists for the company [see

page 23]. Loewy continued to work with

AGA Heat and its parent company – Allied

Ironfounders – until at least the 1950s.

Wren briefed Loewy to produce a new version

of the original AGA cooker, one which would

endure and become a kitchen icon. at vision

was fully realised in 1941 with the advent of the

Standard Model C AGA Cooker, a model which

would go on to remain in production until 1972.

Among the principal design changes were:

• A restyled front plate

• e top and bottom oven doors were

recongured to be the same size

• e rectangular grill over the auxiliary air inlet

and ash-pit door was styled for the rst time to

echo the size and shape of the two oven doors

• e door hinges and handles were modied

• e heat gauge was placed centrally

• e overall design was made signicantly

more ecient.

Wren’s vision – and skill in seeing real talent –

had again paid dividends, with the creation of

a brand new AGA cooker with the design

and engineering values to endure for three

decades.

q

How e AGA Became An Icon 21

Page 12

Douglas Scott (1913–1990) – an industrial

designer and educator – was employed at

the London office of Raymond Loewy

DOUGLAS SCOTT

Scott was particularly proud of his 1938 redesign of the AGA cooker and his

development of the Rayburn. It was a design that was to endure for the next

40 years. Scott’s influence during this period led to the development of greater

standardisation of the AGA cooker, a theme which ran through all of Loewy’s

work and which was later echoed in Scott’s design of London’s iconic and

much-loved Routemaster bus, which was

engineered to be mass-produced in a

sustainable way. The eventual Standard

Model C AGA cooker, illustrated on the

cover of Homes & Gardens magazine in

1940 (right) went even further than before

in its simplification and definition of the

cooker’s design. The AGA was also

proving robust in operation. The Antarctic

expedition team of 1934 took an AGA

cooker with them – a model SBD. All

existing models – both domestic and

heavy duty – were withdrawn in 1941

and in their place a range of units were

introduced with standardised parts

which were, to a much greater extent,

fully interchangeable. Scott’s vision of

uniformity had been achieved.

Associates between 1936 and 1939, where

his work was overseen by American designer

Carl Otto. Together they worked on the AGA

Heat and Allied Ironfounders accounts.

Charles Ludovic Scott

was the Technical

CHARLES

LUDOVIC SCOTT

assigned to renowned industrial designers, it was

Scott’s role to ensure the engineering of the cooker

received similar close attention. During the 1930s

more than 20 patents were filed for technical and

design innovations related to the AGA cooker and other products,

mainly by Scott, under the changing company names of Bell’s Engineering,

Bell’s Heat Appliances, AGA Heat and Allied Ironfounders. Scott is often

featured in brochures of the time advocating research and development and

explaining why they make the AGA cooker a market leader. Board minutes

highlight this determined work to ensure quality and reliability.

research Officer for

AGA Heat Ltd from

1929 until the late

1950s. With the task

of styling the AGA

cooker having been

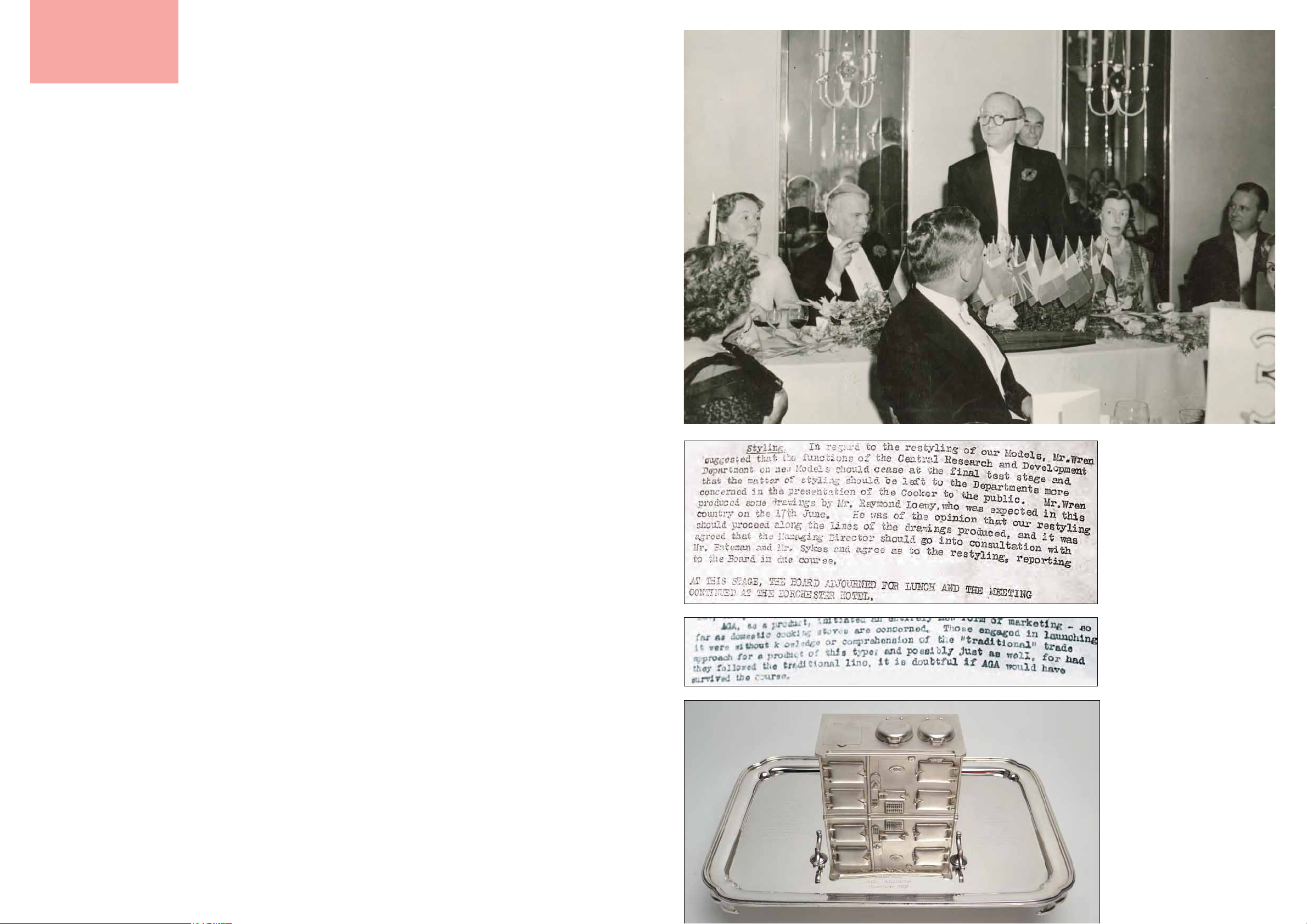

Vintage advertising campaigns for the

AGA cooker (left and opposite page)

illustrate how – now as then – the

emphasis has always been on the

AGA cooker’s economy, design,

engineering and reliability.

How e AGA Became An Icon 23

Page 13

DOROTHY BRADDELL

After the First World War, life in the British kitchen began to change.

LAWRENCE WRIGHT

MABEL COLLINS

Redefining the kitchen

.

dEsigN gENiUs

ThaT chaNgEd

ThE BriTish

KiTchEN

for EVEr

As domestic service declined, the kitchen was no longer the domain

of servants, but of the housewife herself. AGA Heat placed its trust in

the design ethos for the kitchen in the hands of three visionaries –

Dorothy Braddell, Lawrence Wright and Mabel Collins

he kitchen changed during the early 20th

century from a prosaic workspace to an area

T

Modernity “crept in through the back door, via

the kitchen”

created the utilitarian Frankfurt kitchen, while in

Britain the AGA kitchen was to be as modern but

more user-friendly.

Rationally planned and industrially produced, the

emphasis of the ‘New’ Kitchen was placed on the

economic use of labour and resources. As the

household centred on a more self-sucient kind

of family life, the footprint of the home changed in

response. e kitchen was the rst area impacted by

social change.

which embodied modernist principles.

3

German time-and-motion studies

kitchen, changing the look and layout of a space which

was now clearly to be enjoyed rather than merely

endured. e 1930s kitchen was smaller but lighter

than its Edwardian counterpart. It was now no longer

the domain of employees but of the housewife herself.”

Designing the modern kitchen

A pioneer of domestic design, Dorothy Braddell

[Dorothy ‘Darcy’ Adelaide Braddell née Busse, 18891981] can be seen as the mother of the modern

kitchen. She studied at the Regent Street Polytechnic

and the Byam Shaw School of Art and became a

designer and critic of interior design and domestic

planning. She oen worked under her husband’s

name as Mrs Darcy Braddell.

Until the 1930s the kitchen was most oen a space

separate from family living. e homes of the more

auent households in Victorian England had

kitchens run by cooks as part of a team of domestic

sta. Middle-class Edwardian homes were still built

with a presumption that there would be a maid in the

house whose tasks would include cooking.

Although domestic service declined in the inter-war

years, it still represented the largest occupation for

women until the mid-1930s, when service went into

an irreversible decline. A 2004 study for London’s

Science Museum summarised the impact this was to

bring to the kitchen.

“In the space of about 25 years, the kitchen was

transformed om a transient place for the preparation

of food to the new heart of the home. By the end of the

1950s it was a multi-functional living space, as well as

the powerhouse and nerve centre of family life.

“e availability of new materials and nishes, as well

as modern electric appliances came together in the tted

4

Her work was included in pre- and post-war

exhibitions of British industrial art; she was on

the advisory committee of the Council for Art and

Industry; and she wrote essays and material for trade

publications such as e Gas Journal. She was also a

member of the Council of Scientic Management in

the Home, which formed in 1931, and she became a

design expert for the Ideal Home Exhibitions.

Her innovative kitchen designs for AGA Heat

Ltd were constructed for display at exhibitions

throughout the 1930s and 1940s and she was

specially commissioned to design the AGA Cookery

Advisory Department’s kitchen at the company’s

showrooms at 20 North Audley Street, London W1,

a building which, until the 1990s, retained the name

‘AGA House’ in certain circles.

One of the early exhibitions was the British Industries

Fair of March 1936. Contemporary minutes describe

the event as a huge success… “e AGA Exhibit

proed a very great attraction and their new models

were enthusiastically received by Merchants generally.

s

How e AGA Became An Icon

How e AGA Became An Icon 2524

Page 14

DOROTHY BRADDELL

LAURENCE WRIGHT

MABEL COLLINS

eir sales exceeded expectations, and

Mr Wren [Managing Director of AGA

Heat Ltd] is very well satisfied.”

e success of Braddell’s kitchen displays

led to her being given a wider role. A

minute of the time read: “An arrangement

is being made with Mrs Braddell which

will make her services available to Allied

Ironfounders in connection with designing

of goods and of Exhibition Stands.”

In the 1930s, Braddell redesigned a

traditional farmhouse kitchen for AGA

Heat Ltd, both versions of which were

exhibited on behalf of the company and

tied into marketing initiatives advocating

the importance of a planned kitchen, and

how well the AGA cooker would fit into

such an environment.

5

Painting a picture of the future of modern kitchens

Dorothy Braddell’s kitchen designs were painted – rather than simply photographed – by Lawrence

Wright (1906-1983), an author, perspective artist and major commentator on the home. He painted

kitchen images for AGA Heat Ltd from 1936 and (as illustrated here) they show that changes to the

styling of the AGA cooker were being introduced in the second half of the 1930s. The freestanding AGA

cooker, along with the black glass reflective walls and yellow curtains and piping make this kitchen

design feel thoroughly modern, although it is in fact almost 80 years old. The strength of the AGA

cooker in this kitchen living context was that it provided a natural centrepiece that was both practical

and beautiful. An advertisement of the time stated: "Here's a cool and collected kitchen designed by

Mrs Darcy Braddell. The small sink beside the cooker is for cook's convenience. Plenty of cupboards,

too, a big window and nowhere for dust or dirt to collect."

Braddell was impartial in her designs,

creating kitchens which used solid fuel,

gas and electricity. Her philosophy was

functionalist, based on commonsense

and practicality rather than any particular

affiliation.

She was, however, vocal in her support for

the AGA cooker.

“Solid fuel cookers have recently taken

on a new lease of life – or rather there

has been a renaissance in their design

and conception, thanks largely to the

introduction of a cooker of foreign

inspiration.

“is has set an equally high standard in

cooking performance and economy of

upkeep which remains difficult to beat.”

q

26 How e AGA Became An Icon How e AGA Became An Icon 27

Page 15

DOROTHY BRADDELL

LAURENCE WRIGHT

MABEL COLLINS

SERVING UP A NEW APPROACH TO

CONTEMPORARY KITCHEN LIVING

Painted by Lawrence Wright, this kitchen

is based on plans by a successor

or colleague of Dorothy Braddell –

Millicent Frances Pleydell-Bouverie

On 9 May 1873, the reclusive Queen

Victoria made a rare public appearance.

She attended a cooking lecture held at

the exhibition grounds close to London’s

Albert Hall. The Queen and princesses

were ushered into the exhibition’s

School of Cookery to observe the

preparation of a savoury omelette by

a male chef and four kitchen maids.

It was one of the very first cookery

demonstrations and years later AGA

recognised its value to customers.

Today, thousands every year enjoy

cookery demonstrations at AGA shops

throughout the UK. Back in the 1930s

it was a new idea and it was Mabel

Collins – as head of the new AGA

With the housewife now doing the

cooking the onus was on providing

achievable recipes for practical

everyday living and for entertaining and

that tradition continues today through

the AGA demonstration kitchens in

London’s Marylebone High Street and

Brompton Road.

Through Mabel Collins, AGA Heat Ltd

provided practical cooking information

to its customers. AGA Heat Ltd viewed

the provision of information for the

housewife as a major new avenue for

sales and owners of AGA cookers

received monthly or quarterly recipes to

reflect the time of year, with some of

these pictured (right)…

q

Cookery Advisory Department – who

was charged with changing Britain’s

view on food and cooking.

The Cookery Advisory Department

was formally introduced in 1935 in AGA

Heat Ltd’s North Audley Street, London,

kitchen appliance showroom. A

contemporary brochure states: “This is

the test and demonstration kitchen at

London. The head of the department

(Mabel Collins) moved her desk from her

private office into the kitchen ‘because

it was less stuffy’.”

28 How e AGA Became An Icon

Today, thousands

learn more about

the AGA cooker

through instore

demonstrations.

It is a tradition

begun in the

1930s with the

launch of the

AGA Cookery

Advisory

Department

with renowned

food writer

Ambrose Heath

retained as its

Gastronomical

Adviser.

All from

V&A

museum

How e AGA Became An Icon 29

Page 16

AMBROSE HEATH

Ambrose Heath was the Mary Berry of his day – a renowned food

Gastronome

Food writer

Cookbook author

Ambrose Heath

(1891–1969) was born

Francis Geoffrey Miller.

Because his parents

thought journalism an

unrespectable career,

he became known

professionally as Ambrose

Heath. The decision not

to use his real name

was taken, he told an

interviewer in 1966,

because his father was

a gentleman. “My

parents were supremely

uninterested in food,”

he later said.

© National Portrait Gallery, London

writer trusted by millions of British cooks. A big fan of the AGA cooker,

in the 1930s he joined AGA Heat Ltd’s pioneering Cookery Advisory

Department as Gastronomical Advisor…

ThE faThEr of ModErN food WriTiNg

National

Portrait

Gallery

oday it is tricky to imagine a world without

wall-to-wall cookery shows and books by

T

on a weekly basis. However, it wasn’t always so and

without the input of a few notable names it might

never have happened…

Arguably the first ever celebrity chef, Ambrose Heath

quite simply changed the way Britain cooked. He

penned more than 100 cookery books, offering up

recipes for an extraordinary number of foodstuffs

from the prosaic potato to the rather more exotic

squirrel and turtle. In 1933 Heath turned his hand to

AGA cooking with the publication by Faber & Faber

of Good Food on the AGA.

Brands appointing ambassadors is not a new

phenomenon and AGA Heat Ltd was justifiably

proud of its work with Heath, who was in at the start

before Bell’s Heat had even been acquired by AGA

Heat. e foreword to Good Food on the AGA,

celebrity chefs topping the bestseller lists

attributed simply to Bell’s Heat Appliances Ltd, says:

“In writing this book for AGA, Mr Heath has

achieved far more than we ourselves visualised when

the book was planned, for not only has he written

on the best way of securing the greatest use and

satisfaction from the cooker, but he tells of many

dishes singularly fitted for the preparation on it;

dishes which are gathered from the cuisine of many

lands and which will help to brighten our table.”

Aer the publication of the book, Heath’s association

with the AGA cooker continued to grow. In 1935

he was appointed e AGA Cookery Advisory

Department’s Gastronomical Advisor. In a letter

of the time which went out to distributors, Mabel

Collins wrote: “Mr Heath will give free advice to

owners on their cookery problems”.

Heath enjoyed his schooldays at the progressive

Clion College, though he did say: “I didn’t like

the formality of ordinary education. I was interested

in special things.”

s

How e AGA Became An Icon 31

Page 17

AMBROSE HEATH

EDWARD BAWDEN

Painter

Perhaps this is why he enjoyed

such a varied and colourful career, which included

working for the Hudson Bay Company, the India

Office and co-founding the Wine and Food Society,

before a quarrel with the then secretary caused him to

resign. His journalism began with a series of ‘casual

pieces’ submitted to, amongst others, e Times, News

Chronicle and the Yorkshire Post, before becoming

cookery correspondent for the Morning Post.

Ambrose Heath didn’t just write on the subject

of AGA cookery; he was a passionate AGA cook

himself. A 1933 AGA brochure stated: “For many

months now Mr Ambrose Heath has done his own

cooking and tested his professional recipes on an

AGA Cooker, and his enthusiasm is unbounded for

the AGA cooker’s cooking efficiency.

“He explains the various improvements made possible

by AGA cooking and the difference in method due to

the principle of AGA Heat Storage. He emphasises

especially the enormously increased leisure which the

AGA affords the Cook.”

In a 1939 brochure Heath speaks for himself:

“… I can say without exaggeration we have had much

better food since it was installed than ever before, the

reason being, I suppose, that it is

much easier to cook on. e AGA

seems to make one want

to cook…”

roughout the war years,

Heath was one of the main

voices of the BBC’s e

Kitchen Front. A series of talks

organised by the Ministry of

Food, Heath’s role was to

encourage frugality and ease

the hardship of rationing

with recipes, household

hints, exhortations from

government officials and

comedy. e themes

re-appear in 1946 in an

early Rayburn brochure.

e Kitchen Front was a platform to encourage the

population to make the most of meagre resources

and to keep healthy and its success lay mainly in its

homely and avuncular cast. e programme went

out at 8:15am every day and lasted five minutes.

e timeslot – widely considered to be a golden one –

was chosen as it was ‘before the housewife sets out to

do her shopping’.

Usually presented by Ambrose Heath and the popular

broadcaster Freddie Grisewood (known affectionately

as ‘Ricepud’) and contributed to by many, including

Marguerite Patten and Lord Woolton, it attracted up

to 14 million listeners, significantly more than any

other daytime talk programme.

In the first week alone the BBC received 1,000 letters,

along with parcels of cake and other gis from housewives responding to its tips. He had established an

AGA cookery tradition still continued today by,

amongst many others, Mary Berry, Lucy Young,

Amy Willcock and Louise Walker.

Heath’s later years were spent, with his much younger

wife Violet May, in Holmbury St Mary in Surrey, with

an AGA cooker and a flower garden, but no

vegetable garden. He died on 31 May 1969. q

Ambrose Heath’s Good Food on the AGA

(left) featured beautiful illustrations by

Edward Bawden, well-known for his

work with Twinings, Shell-Mex and

Fortnum & Mason, as well as

renowned London Transport creatives

which included posters during the

1930s and tile motifs for London Underground.

One day a week Bawden worked for the Curwen

Press, so perhaps he was instrumental in the

decision to create menus and recipe cards

(below) from Good Food on the AGA, which

were printed by the same company. During the

Second World War, Bawden served as an official

war artist in France and the Middle East.

Designer

AGA cookbook

illustrator

Edward Bawden (1903–

1989) was a renowned

painter and designer.

His design tutor was the

artist Paul Nash, while

other contemporaries at

the Royal College of Art

included Barnett Freedman,

Henry Moore and Douglas

Percy Bliss, who was to be

his future biographer. Among

Bawden’s accolades were

his appointment as Royal

Designer for Industry (RSA)

in 1949 and his election as

a Royal Academician in

1956. He was awarded a

CBE in 1946.

32 How e AGA Became An Icon How e AGA Became An Icon 33

Page 18

MARKETING

THROUGH THE

YEARS

Marketing campaigns through its 10 decades

illustrate beautifully how – despite huge

changes in the British kitchen – the AGA

cooker has remained very much at

the heart of the home.

1970s

2004

1950s

2013

1990s

1980s

1980s

1930s

1930s

2011

34 How e AGA Became An Icon How e AGA Became An Icon 35

Page 19

THE MODERN RANGE

aNd ThE iNNoVaTioN

coNTiNUEs TodaY…

The main factor that ensures the AGA cooker remains

both iconic and popular in its tenth decade is that it has

moved with the times and adapted to modern living.

It is easy to implement change for the sake of it or to

incorporate technology where it is not needed. This has

not been the case with the AGA cooker – each change

has been considered and has made a real difference to

the lives of AGA owners.

From the introduction of new fuel types to an on/off

A 3-oven AGA cooker in Heather pictured in a stunning

contemporary Bath home featured on TV’s Grand Designs

AGA that can be controlled via a smartphone app, the

AGA cooker has evolved to work brilliantly with changes

in domestic routine, just as it did in the turbulent 1930s.

Most AGA cookers sold today run on electricity, which

allows new markets to open up and for cooks worldwide

to enjoy the AGA cooker. China is a perfect example.

Until very recently kitchens there were simply work-

spaces, but now they are becoming rooms to live in,

rather like ours in the UK. It is because of this that the

AGA cooker is set to become a huge hit in the East.

How e AGA Became An Icon

36

Recent launches have included

the fully programmable AGA iTotal

Control (left) and (main image) the

new 5-oven AGA Total Control, the

biggest ever manufactured and

pictured here in a conservatory

kitchen in Wandsworth, London

How e AGA Became An Icon 37

Page 20

THE MODERN RANGE

soUrcEs, rEfErENcEs &

acKNoWLEdgEMENTs

A 3-oven AGA Total Control in

the kitchen at Spring Cottage,

Cliveden, which in 1963 was at the

heart of the Profumo affair

In 2011, AGA Rangemaster entered into a Knowledge Transfer Partnership with

Birmingham City University to establish a digital gallery of selected archive

material charting the AGA ‘look'. It is anticipated that the digital archive will make

a valuable contribution to the new Birmingham City Library.

Charlotte Whitehead – appointed as KTP associate and archivist – undertook the

principal research for this publication under the supervision of Dawn Roads,

cookery writer and head of the AGA demonstrator team (and, as such, a

successor to Mabel Collins)..

Charlotte and Dawn co-authored this booklet with Laura James and Tim James,

author of ‘AGA: The Story of a Kitchen Classic’. The booklet was designed and

produced by Mabel Gray.

Most of the images used are from the archives of AGA Rangemaster Group plc.

The Board minutes of Allied Ironfounders and AGA Heat from the 1930s and

1940s provided the backcloth to the research project.

AGA Rangemaster would like to thank the National Portrait Gallery; the Design

Council Archive (University of Brighton); Transco plc; Getty Images and the

Victoria & Albert Museum for permission to use photography and illustrations.

1. Carr, R. (1971). Obituary, Walter omas Wren (1901-1971). Design, Journal of the

Council of Industrial Design, no. 272, August 1971.

2. Raphaelson, J. (1986). e unpublished David Ogily – a selection of writing om the les

of his partners. Pub: e Ogily Group, Inc.

3. Morris, M. (1988). ings to do with shopping centres, in Sheridan, S. (ed.) Gras. P. 202.

4. Sugg Ryan, D. (2006). e vacuum cleaner under the stairs: women, modernity and domestic technology in Britain between the wars. Design and Evolution: e Proceedings of the

Design History Society annual conference, 2006 (Design History Society & Technical University Del, Netherlands)

5. Braddell, D. (1935). Kitchen Planning and Equipment. Architectural Design and

Construction, ol. 5, p. 123-130.

6. Clendinning, A. (2004). Demons of Domesticity: Women and the English Gas Industry,

1889-1939. Pub: Ashgate

To bring an icon home, visit www.agaliving.com

or call 0845 712 5207 to organise an

AGA cookery demonstration

38 How e AGA Became An Icon

How e AGA Became An Icon

How e AGA Became An Icon 39

39

Page 21

Loading...

Loading...